14

Sustainable Development: Ganados del Valle Enterprises

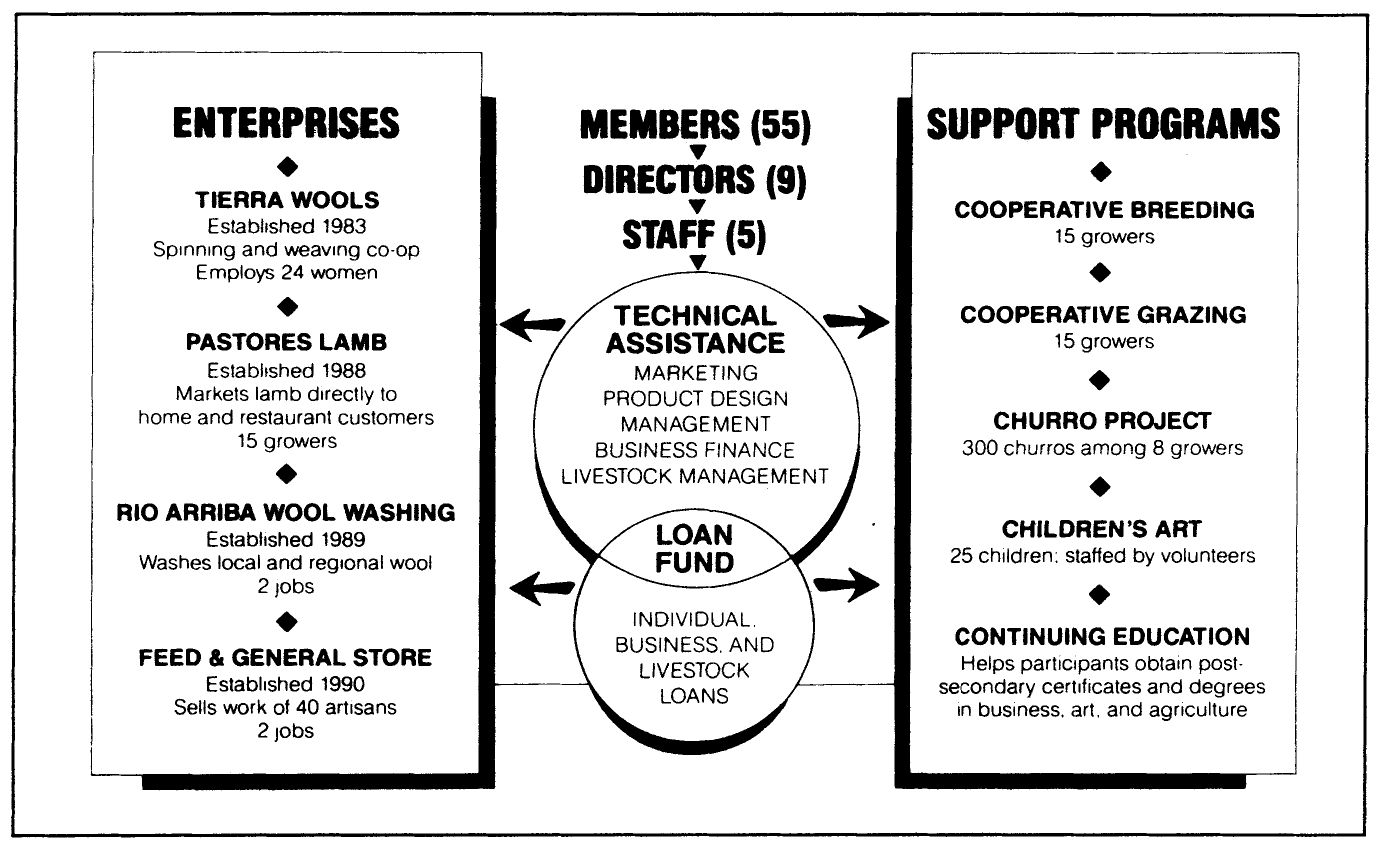

THE MOUNTAIN VILLAGE of Los Ojos, New Mexico, is home to Ganados del Valle (Livestock Growers of the Valley), an economic development organization chartered in 1983 to revitalize the agricultural economy in northern Rio Arriba, one of the poorest counties in the United States. By 1991 the organization had created thirty-five new jobs, formed four businesses, organized agricultural support programs in co-op breeding, grazing, and financing, and established itself as a model for culturally beneficial and environmentally sound rural economic development. Specific Ganados enterprises included Tierra Wools (1983), a handspinning and weaving cooperative; Pastores Lamb (1988), a sheep growers’ association marketing specialty and farm-flock lamb; the Rio Arriba Wool-Washing Plant (1989), a custom wool washing service for local and regionally grown wool; and the Los Ojos Feed and General Store (1990), a family business incubator marketing locally produced and handcrafted items (see fig. 14.1 for other project examples).

Located in north-central New Mexico, Río Arriba County is part of a six-county region that includes Taos, Mora, San Miguel, Santa Fe, and Sandoval. Two mountain ranges dominate the region: the San Juan Mountains, which frame the central and western portions of Río Arriba County, and the Sangre de Cristos, which separate Taos County from the high plateaus to the east. Characterized by high mountain peaks with alpine meadows and semiarid mesas, the region has a wide range of elevations, temperatures, rainfall, and plant and animal life. The six counties total 20,311 square miles.1 In 1988 their combined population was estimated at 237,200.2 Río Arriba County by itself covers 5,856 square miles and had a population in 1988 of 32,600. By comparison, the area of Connecticut and Rhode Island combined is 5,927 square miles with a population of 4,226,000.

In the higher elevations small agricultural settlements are located primarily in irrigated valleys. Hispanic and Native Americans comprise a majority of the population. Some Native American communities have indigenous roots going back as far as A.D. 800 Spanish and Mexican settlers arrived in the early 1600s, favoring fertile areas along the Río Grande and narrow valleys and canyons in the mountains. An agropastoral economy based on horses, cattle, and the Churro sheep brought by Spanish-Mexican settlers made possible the settlement of isolated places by providing transportation, food, and fiber to these remote villages. The Churro is a long-wooled sheep which nearly became extinct. Its rich, colored fleece is prized by Hispanic and Navajo weavers. The settlers introduced sheep husbandry, wool processing, and weaving techniques to the Pueblo Indians, who subsequently conveyed these skills to the more remote Navajo and Hopi Indians. For over two hundred years Spanish-Mexican settlers of Mediterranean, Moorish, and Mexican-Indian background traversed the region, intermarrying with the indigenous people and creating a unique cultural ecology.3

In 1848, when the United States took over New Mexico and other southwestern territories under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Anglo property law, contrary to the provisions of the treaty, was superimposed on the traditional pattern of cooperative land tenure. Such tenure had been required of the community land grants (mercedes) issued by Spain and later Mexico. Ultimately, the American concept of separately deeded property was enforced by court order and barbed-wire fencing. Spanish and Mexican law had designated large areas of land grant acreage to be held in common for pasture, timber, hunting, and other community uses. Settlers typically pooled their flocks and herds, having them graze high mountain meadows in the summer and lower river valleys in the winter. This system of sustainable grazing was disrupted as Anglo-Americans claimed and fenced off the common lands. Anglo-Americans also introduced commercial livestock production and export marketing, which forced traditional growers to discontinue the sheep husbandry methods that had evolved over two centuries in the fragile, semiarid, high mountain climate. With the loss of communal grazing lands, villagers were limited to small family plots on valley floors that became seriously overgrazed.

FIGURE 14.1. Ganados del Valle: Organizational Structure

In the early 1930s severe winter storms coupled with a steep drop in wool prices wiped out most large-scale operations. When the huge flocks disappeared indigenous communities were left with an eroded landscape and a collapsed economy. As elsewhere in the country, these traditional communities had become linked to and dependent on a cash system. Ownership of livestock was often a liability instead of an asset as the high-elevation climate and loss of communal grazing lands required that feed be purchased six months out of the year. Many residents either left their villages or commuted long distances to jobs in more populated areas, a process that accelerated after World War II. Remaining ancestral land and water resources were underutilized or sold as villagers with little cash struggled for economic survival. Small-scale and subsistence-level sheep growing continued, however. Sheep, a cultural symbol as well as a food and fiber resource, buffered some families from abject poverty.

EVOLUTION OF A SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY

The isolation of the region and its cultural ecology kept it from enjoying postwar economic growth and the federal interventions of the 1960s and 1970s that spurred development in other depressed rural areas of the United States. State and federal planners encouraged tourism in northern New Mexico, which had an abundance of scenic, recreational, and cultural resources. However, in some villages where resort tourism competed for land and scarce water resources, residents who retained strong cultural ties to the land resisted and began searching for alternatives.

The Tierra Amarilla Land Grant in the upper portion of the Rio Chama basin covers an area close to 1,000 square miles, ranging from fifteen miles over the Colorado border to the north to the Río Nutrias south of the village of Tierra Amarilla. The population of the Land Grant in 1980 was roughly nearly 3,000.

In 1980 the village of Chama applied for a section 111 planning grant from the FmHA. The Village Council retained the Design Planning and Assistance Center at the University of New Mexico to facilitate the planning process. A team of students and faculty from the center and citizen volunteers from the villages of the Chama Valley was formed. University personnel recommended that the REP approach, involving extensive community input, be used to develop a plan. Through surveys, community meetings, and mass mailings over a six-month period, comments and opinions were gathered and draft goals disseminated. Final goals were adopted and subsequently printed and distributed throughout the community in 1981. Among the goals expressed in the adopted plan were developing a community economy based on the use of local, natural, and cultural resources without ruining the environment or harming the people; increasing job and income opportunities for women and young people in the Chama/Tierra Amarilla Valley and evaluating the practicality of a locally based wool processing and weaving industry.4

At the conclusion of the planning process in 1981 the village of Chama, the project sponsor, was severely underfinanced and its officials could not envision a role for the village in implementing the plan. Regional and state economic development agencies did not take on the task of implementing the recommendations of the plan because the goals did not fit the state government’s economic development strategy for the region, which favored tourism and the recruitment of light industry and high-tech firms. The state economic development agency, for example, supported the efforts of a private development corporation to create a downhill ski resort bordering on the headwaters of the Brazos River, which irrigates the southwestern portion of the valley. Many long-time residents concluded that this development would not be environmentally sound or culturally appropriate; if built, it would create primarily low-wage seasonal jobs. Moreover, it would not enhance the self-reliance and economic sustainability of the region as a whole.

Accordingly, a small group from the villages in the southern end of the valley decided to take steps more appropriate to their cultural ecology and the goal of economic sustainability. Their main concern was that a ski resort would raise land values and divert scarce water resources from agriculture to recreation. They reasoned that over time an increase in land value and water cost without a concomitant increase in income from the land would result in the transfer of ownership of land and water sources from local families to developers. There was also widespread concern that upstream development in the higher elevations would reduce access to irrigation water and increase water pollution, problems experienced by villages downstream from the Taos ski valley in neighboring Taos County.

While valley residents had previously succeeded in halting large-scale resort projects, they concluded that this was not enough; action had to be taken for appropriate and sustainable economic development. They defined this as development that would employ the cultural skills and resources of the region, expand business and professional opportunities for local people, provide year-round jobs, and respect the physical constraints of the environment. They began to work on the most urgent needs of local sheep growers: reducing the loss of sheep and lambs to predators, finding better markets for lamb, and obtaining higher prices for wool. If they were able to help solve these problems, and if people were willing to work cooperatively, an organization would be formed.

Through research they learned that livestock guard dogs to control predators were being tested throughout the country by the New England Farm Center in Amherst, Massachusetts. Further research identified a sheep growers’ cooperative in the Pacific Northwest that marketed lambs from a four-state network through a national telephone auction. By the end of 1982 the villagers had accomplished two concrete objectives. First, the New England guard dog project placed two dogs with a 300-head flock and trained the owner to handle them. The first summer the dogs were used the flock’s losses were cut from 45 percent to 12 percent. Second, the manager of the sheep growers’ cooperative was invited to come and explain the telephone auction system. After inventorying area flocks the manager recommended that Chama Valley growers participate in his cooperator’s next telephone auction. That year, participating growers received 7.5 cents more per pound for their lambs than was paid by local markets.

By March 1983 community residents expressed enough interest to form an organization. Eight people established Ganados del Valle as a private, not-for-profit economic development corporation. They chose not-for-profit status because it would enable them to attract funding and investment capital from philanthropic sources. In the early years funds for technical assistance, training, marketing, and loans were raised in small amounts from progressive foundations, churches, and concerned individuals.

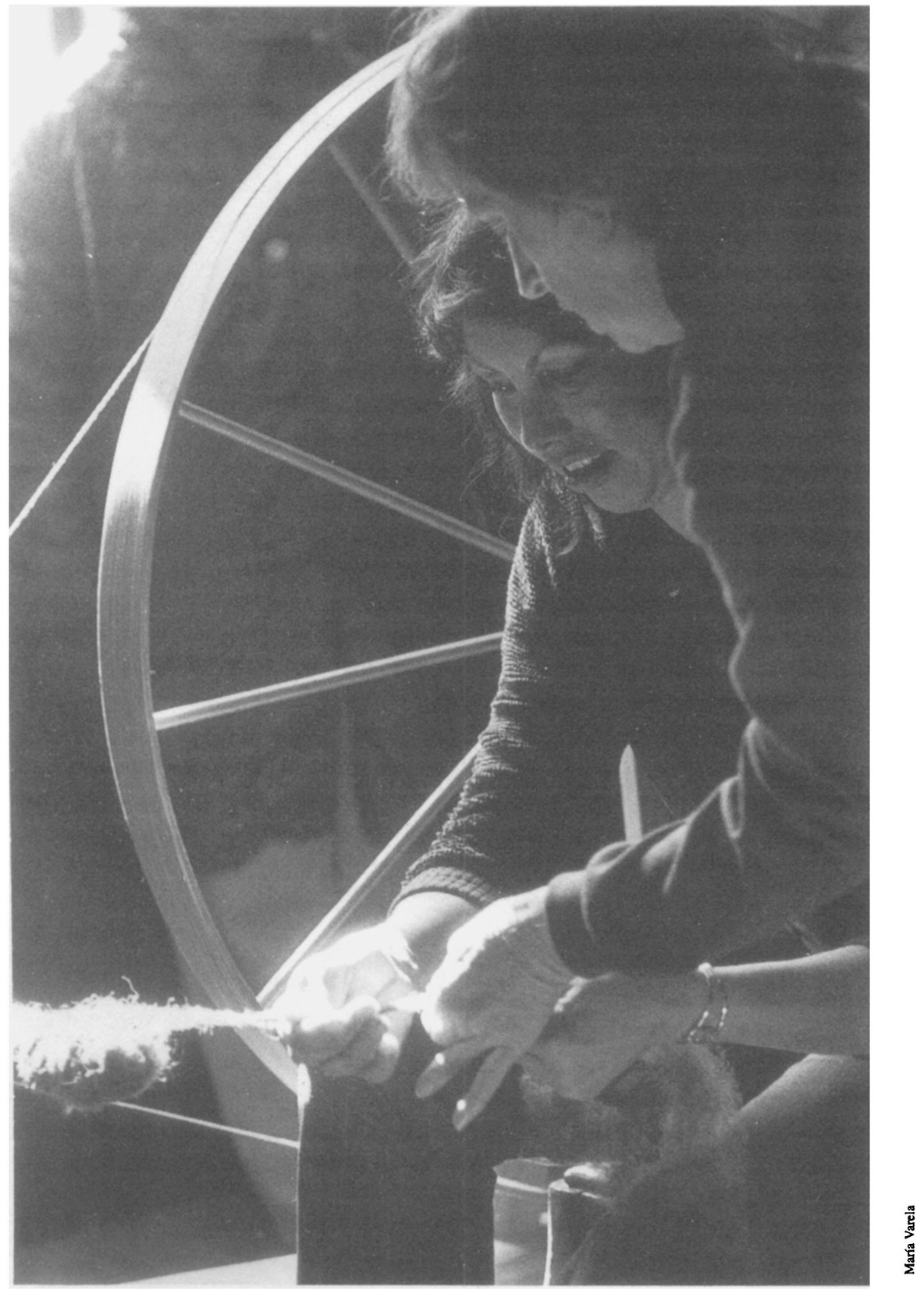

The original board members set goals for the rest of the year and selected committees to work on each goal. The wool committee immediately began to look into alternative ways of utilizing local wool. A professional weaver and handspinner from Taos, Rachael Brown, was brought in to evaluate the quality of locally grown wool and to meet with residents to discuss handspinning and weaving. Brown determined that wool from the breed common to the area, Western Whiteface, would yield a lustrous handspun yarn that could be dyed striking colors and wholesaled on a test basis to yarn shops in the region. She also proposed that local weavers use the spinning wheel in place of the malacate, or hand spindle, used by traditional weavers in New Mexico. The spinning wheel had never been used in these remote villages, so Brown and the Ganados board of directors organized a demonstration in May 1983 at the old church in Los Ojos, an event that attracted people from all over the Chama Valley. Men and women, young and old, tried their hand at spinning. During the demonstration Brown noticed a room where six or seven looms had been set up around a woodburning stove. Inquiring further, she discovered that there was a handful of people whose hobby was the nearly extinct Rio Grande style of weaving. Their workmanship showed a great deal of promise, even though they used discount synthetic yarns in standard commercial colors. She suggested that as soon as the handspun yarn enterprise was under way, some of the weavers should be trained to produce a limited selection of products for wholesale; they might even pick up a little retail business from seasonal tourism. Retailing, Brown believed, would create financial reserves to support the handspinning business through lean periods.

In 1983 Brown was hired to come to Los Ojos once a week and hold classes covering professional production techniques, quality control, pricing, marketing, wholesaling, and retailing. A year later, at the completion of training, all weavers were skilled at selecting their own colors and patterns and each had contributed to a collaborative design. Business skills were also taught so that weavers would be able to read balance sheets, forecast cash flows, and plan annual production and marketing goals.

The number of residents, more women than men, interested in working on the weaving project grew. Soon the group was looking for a larger facility. An opportunity arose in summer 1983 to purchase an old adobe mercantile store that was going out of business. It was the only store left in the historic village of Los Ojos. Nervous board members took a deep breath and authorized the raising of funds for a downpayment on the 100-year-old 7,000-square-foot adobe building. The acquisition of this property was the turning point for the fledgling organization. Now it had a physical location and was credited with saving an historic property.

FIGURE 14.2. Noted spinner and weaver Rachel Brown teaches Tierra Amarilla resident Maxine Garcia to use the spinning wheel during a 1983 demonstration and workshop.

TIERRA WOOLS

The weavers and spinners who had been working with Brown chose the name Tierra Wools for this, the first business formed by Ganados del Valle. Tierra Wools opened for business in July 1983 as an unincorporated subsidiary controlled by the weavers. The new business was incubated under the corporate umbrella of Ganados del Valle during the start-up phase to secure grants and obtain technical assistance and further training. A loan from a revolving loan fund already established by Ganados del Valle financed start-up costs. Sales paid wages as well as production costs. Tierra Wools had its own checkbook and made its own business decisions, the Ganados board of directors merely seeing to certain legal technicalities.

By 1985 it was clear that the driving force behind Tierra Wools was weaving. It took two more years of steadily increasing sales with more efficient production and more effective promotion before some of the elements of its success were identified. The weavers came to realize that by revitalizing the centuries old Rio Grande weaving tradition and by using the wool from the valley, including the nearly extinct Churro sheep, they were addressing two overlapping market niches. One niche was cultural tourism, which attracts visitors looking for noncommercialized settings where they can share cultural experiences. The other niche is the growing national and international demand for natural fibers and high-quality handmade items. The quality handwoven work was offered for sale in an ordinary village setting where visitors could meet the artisans and observe wool being dyed, spun, and woven. By 1990 yearly sales for Tierra Wools were over $200,000, with twenty-four people working either part- or full-time.

GANADOS DEL VALLE REVOLVING LOAN FUND

The Ganados del Valle loan fund and support programs played a major role in bringing members skills and economic capacity along so that they could take advantage of emerging marketing opportunities. By 1989 the revolving loan fund had built community investment capacity to over $100,000 in cash. Two hundred sheep, moreover, had been acquired as part of the partido, or livestock shares program. Under this program ten to fifteen sheep were “invested” with a grower for six years. Each year the grower was required to return one lamb to the organization. These lambs in turn were reinvested with another grower or sold to fund a scholarship program. By the end of the sixth year the original borrower was required to return to the organization the same number of sheep originally invested, completing a full cycle of the shares program.

The revolving loan fund had been established in 1983 with a $5,000 grant and augmented the following year with additional grants totaling $25,000. In 1988 the organization received an $80,000 infusion of funds to assist with the purchase and start-up costs of a feed and general store. Over the years the loan fund has provided small cash loans to growers and weavers for equipment, for upgrading flocks, and to start new enterprises. These loans are made at a flat interest rate, usually a few points lower than local bank rates, and they are backed by full collateral. The loan repayment schedule fits the cash flow of the borrower, and the fund has the flexibility to set interest-only payments until a business is able to handle repayment of the principal. All interest earned is returned to augment the loan fund.

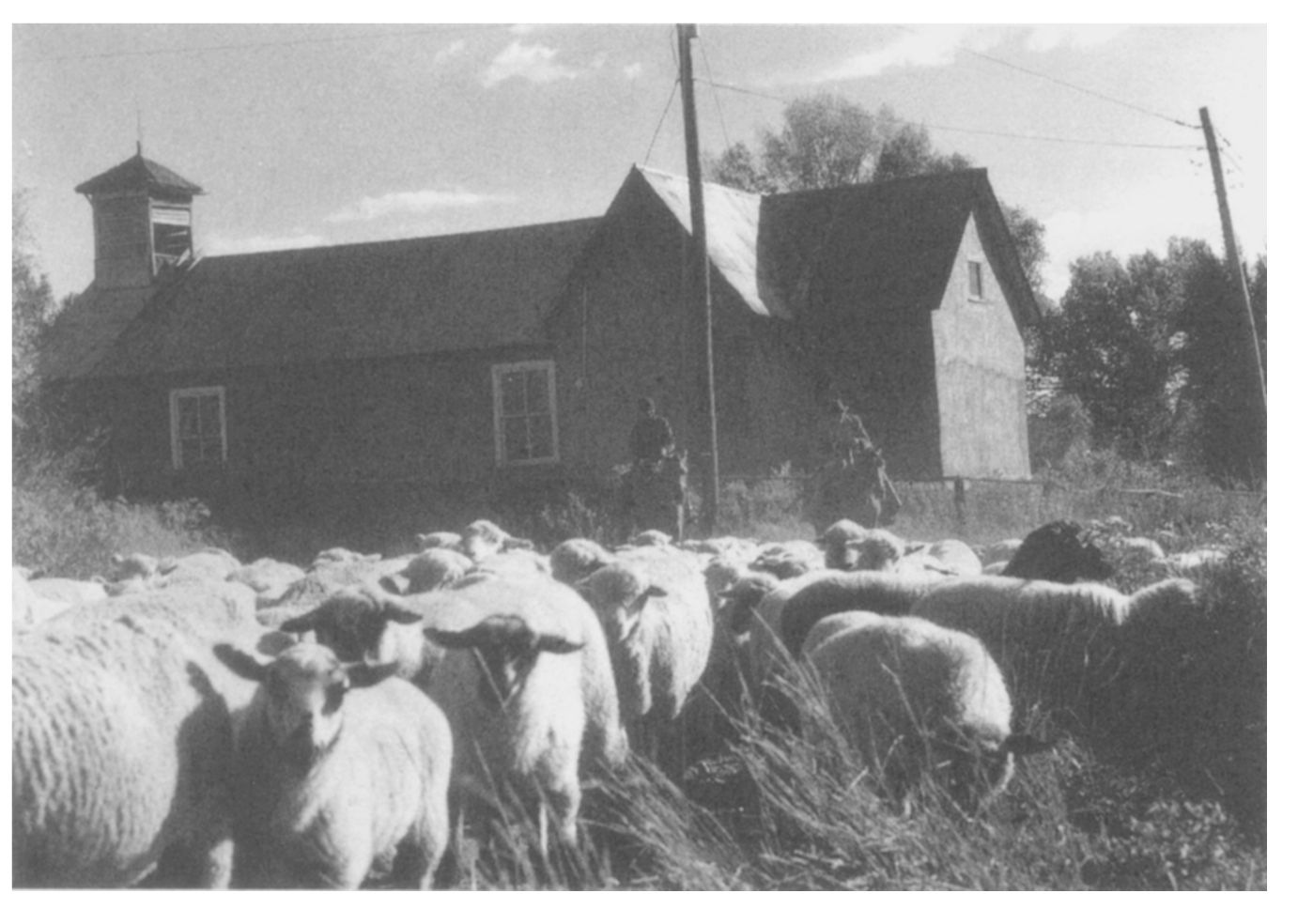

FIGURE 14.3. Ganados farm manager Antonio Manzanares and sheep herder Martin Romero bring a cooperative band of sheep back from summer grazing in the W. H. Humphries wildlife area.

RIO ARRIBA WOOL WASHING PLANT

The availability of appropriate technology is as important for business start-ups as accessible capital. As the demand for wool grew with the expansion of Tierra Wools, so did the need for a more efficient method of washing it. When Tierra Wools was buying 500 pounds of wool a year from local growers and spinning it, the wool was washed in home washing machines. However, as production increased the co-op was buying over 2,000 pounds of wool a year. Not even several home washing machines were cost-effective. Large-scale commercial scourers, on the other hand, could not meet the needs of handcrafters who required wool washed in separate color lots.

Commercial scouring would also drain dollars from the community. Ganados del Valle thus began looking for a technology that would be more labor-than capital-intensive and that would be environmentally sound. Board members discussed the problem with Dr. Lyle McNeal, professor of animal sciences at Utah State University and director of the Navajo Churro sheep project. Professor McNeal had served as a consultant in animal husbandry to the Churro sheep-breeding project since the formative years of Ganados del Valle. He had also developed a prototype, intermediate-level wool washer for Churro wool at Utah State University. While the university washer was labor intensive and could handle 200 pounds of wool a day, it was not energy-efficient. Dr. McNeal allowed Ganados del Valle to use the prototype design and retrofit it in the interests of energy efficiency and commercial viability.

After reviewing technical resources for assistance in designing the retrofit, the organization assembled a design team of weavers, growers, a local machinist, and Dr. McNeal. They reasoned that a collaborative design was needed for a plant that could be maintained and perhaps later expanded with local expertise. In 1990, Río Arriba Wool Washing Services opened for business by training a plant operator who washed 1,000 pounds of local wool. In 1991 the plant hired an assistant for the operator and washed over 2,000 pounds. By 1992 a full marketing plan will be developed to attract Rocky Mountain and west coast consumers. The plant is one of the few intermediate-scale services in a four-state region for washing wool to handcrafters’ specifications.

PASTORES LAMB

By 1988 Ganados del Valle support programs had begun to show results in larger and better lamb herds. Because sheep growers realize two-thirds of their income from lamb sales, better markets needed to be found for lamb. Taking note of the growing consumer demand for naturally grown, locally produced foods and regional specialty foods, Ganados del Valle hired a marketing specialist and test-marketed Churro lamb to Santa Fe restaurants and individual customers. At the same time, it applied to the USDA for certification approval of Churro lamb. The USDA granted it in 1989, meaning that customers who saw the certified Churro stamp on meat cuts knew the lamb was authentic. Growers chose the name Pastores (Shepherds) Lamb to market it, and in fall 1989 the cooperative offered fifty specialty lambs (Churro and Karakul) and one hundred and fifty farm-flock lambs (Columbia-Rambouillet Cross) to New Mexico restaurants and individuals. In 1990 Pastores Lamb received certification as an organic lamb grower and preceded to market 350 lambs, both Churro and Columbia Cross, to New Mexico customers. In both years, growers realized from 20 to 50 percent more income from marketing through Pastores Lamb.

PASTORES FEED AND GENERAL STORE

Ganados del Valle, meanwhile, purchased a second historic building in 1988, renovated it, and in 1990 opened Pastores Feed and General Store. This enterprise has two main goals: slowing the outflow of dollars from the local economy, and incubating family-based economic activity. By marketing livestock feeds, veterinary supplies, handmade gifts and foods, money circulates one more time through the local economy. Family-based enterprises, initially too small to warrant separate retail space, are encouraged to test-market homemade tortillas, baked goods, fresh eggs, jams, jellies, quilts, woodcarvings, and other folk and fine art work. Eventually, services such as horseshoeing, shearing, fencing, and saddle repair will be advertised through the general store. The mix of merchandise was designed for both local residents and visitors. The Ganados revolving loan fund provides seed money for the General Store, as well as small loans to artisans for the purchase of equipment and materials. It also provides technical assistance for product development, pricing, and packaging.

AGRICULTURAL SUPPORT PROGRAMS

Strengthening Hispanic ownership of land and water resources undergirds the sustainable economic development strategy of Ganados. Agricultural support programs help small growers overcome disadvantages of small economies of scale. For example, through the cooperative breeding program, members own expensive breeding rams in common. Growers pool their flocks during breeding season and select rams according to color and other characteristics. Members receive technical assistance from the Ganados marketing specialist in wool characteristics, genetic selection, flock health and nutrition. The cooperative grazing program allows members to pool their flocks under one shepherd and bring their sheep to high mountain pastures. Growers pay grazing leases of their respective flocks and share in the costs of the shepherd. By 1990 the Ganados del Valle membership had grown to fifty-five families. Nearly all members were directly involved in the projects, businesses, or marketing activities of the organization.

ELEMENTS FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF GANADOS DEL VALLE

While the Ganados del Valle experiment has not been without problems, in its seven years of operation it has benefited the local economy and work force. By focusing on human development, expanding local control of the use of resources, establishing a loan fund to increase internal investment capacity, and identifying appropriate technical and structural solutions, the Ganados model demonstrates how human and cultural resources can be utilized to build a sustainable economy.

EMPHASIZING HUMAN DEVELOPMENT

The basic components of development as set out by the organizing members of Ganados del Valle were the natural and agricultural resources of the area, and the local repository of cultural information and skills. The Ganados leadership designed training and support programs to integrate ancestral skills in sheep husbandry and wool crafting with modern techniques in business management and marketing.

Particular attention was paid to the selection of the technical assistance team. The organization sought consultants who were successful entrepreneurs in similar or related fields, understood the market the organization was addressing, would respect and build on cultural skills in collaborative teaching, and possessed the expertise or willingness to find technical solutions fitting the scale of operations and the resources available. In the first five years the successes of Ganados del Valle were due largely to its ability to locate consultants in weaving and animal husbandry who met these criteria. Funds were raised from philanthropic foundations to retain consultants on an annual basis. As members of Ganados del Valle gained skills, reliance on the technical team gradually decreased and was ultimately eliminated.

The Tierra Wools training program for weavers serves as a good example of the emphasis on human development. Rather than seeking a weaver with only artistic training, Ganados retained an expert skilled both in the art of weaving and in the practice of retailing. Tierra Wools was established from the outset as a business for the purpose of creating new jobs. It also sought to conserve cultural skills related to raising sheep and processing wool and to provide a source of off-season income to sheep growers and their families.

After a period of time, it became evident that Tierra Wools would itself have to train additional weavers to expand output and fill vacancies due to turnover. The Ganados del Valle planner, in collaboration with the Tierra Wools weaving consultant, developed a five-unit curriculum to train weavers. The program, taught by advanced weavers, covered basic wool crafting and entrepreneurial skills. By the fourth year advanced weavers were able to take on apprentices and have them produce marketable products within two months. Advanced weavers found that their skills deepened as a result of teaching, and many became articulate about their art. This improved their sales abilities.

Eighteen weavers of varying age and educational background have been through the curriculum. Because of its success, Ganados del Valle is negotiating with institutions of higher education to accredit a work-based program where Tierra Wools members will receive college credit for their own weaving course. Additional coursework would be offered in Los Ojos, enabling weavers and other community residents to apply these credits toward an associate of arts degree in business or fine arts.

LOCAL CONTROL OF RESOURCES

Prior to 1980 local sheep growers had no choice but to market their lambs outside the region. Each year lambs were sold “on the hoof,” without bringing in the added value of separately marketed meat and wool. By establishing a local market for wool, as well as locally processing and crafting it, Ganados del Valle increased local decision-making about the use of this agricultural resource and brought increased income to the area. By 1989 the capacity to process lamb meat in the community and sell it directly to individuals and restaurants was being developed.

Local control of the use of resources also ensures that the area remains a cultural attraction. Ganados del Valle founders believe that the area’s historic villages set in a mosaic of irrigated fields and pastures surrounded by high mountains and alpine meadows are an economic as well as a cultural resource. Throughout its history, Ganados del Valle has advocated that empowering a community to develop a sustainable economy must include local control over land and water uses. In 1986 members helped the county government to strengthen subdivision regulations aimed at conserving agricultural lands and water resources. They also wrote the section of the regulations which required subdividers to put in community water and sewage systems at a smaller density level than state law required. Residents countywide supported the requirement that environmental performance of subdivisions not threaten the valley’s scenic resources and traditional agriculture.

Another effort to expand local control of the use of resources came in summer 1989 when Ganados del Valle sheep growers were confronted with a shortage of available grazing land. They engaged in direct action to feed their cooperative band of sheep and to demonstrate that livestock grazing can serve as a management tool to improve wildlife habitats. Because Ganados del Valle primarily serves small-scale landowners in the valley, the organization must secure long-term leases for summer grazing. Sheep growers cannot expand their flocks beyond subsistence level unless they are assured that larger flocks will be taken off home pastures and grazed on larger parcels with good summer forage. Long-term grazing leases assist flock owners in planning their expansions and projecting their sales and profits. Most traditional communal grazing lands of the Tierra Amarilla land grant are in the hands of the New Mexico Game and Fish Commission and private ranchers. Private ranchers have their own grazing needs or lease to cattle growers who can pay higher fees. Leasing grazing land from private owners has become doubly difficult, as larger ranches are now divided into smaller parcels or developed for recreation. Each summer since 1982 the Ganados del Valle flock manager has searched for private owners willing to lease for the longest term possible. Multi-year leases have not been available, leaving growers to the uncertainty of seasonal leasing.

The state of New Mexico controls over forty-four thousand acres of game-lands, managed primarily for hunting, in the northern mountain forests and meadows. Since 1982 Ganados del Valle had been involved in negotiations for use of this land in a grazing research project. The cooperative band of sheep would be utilized as a management tool to improve forage for game and to clear shrubs and weeds without the use of chemical defoliants. Ganados del Valle sought to apply wildlife forage-improving programs that had been used successfully with sheep and cattle in intensive, time-controlled grazing rotation in the Pacific Northwest as well as in South America and Africa.5

In 1989 Ganados del Valle received notice that its flock would have to leave the temporary grazing lands leased from the Jicarilla Apache before the end of the summer. The organization once again contacted the New Mexico Game and Fish with a request for emergency grazing and consideration of its standing proposal to demonstrate grazing as a management tool for wildlife habitat. Game and Fish declined. Growers had to choose between selling their flocks or taking direct action to bring attention to their plight. In August of 1989 members moved their sheep to the W H. Humphries Wildlife area. This prompted the Governor of New Mexico to locate temporary acreage on a nearby state park for lease to the sheep growers for three more weeks, allowing their flocks to be moved out of the wildlife area. The Governor then organized a task force which included Ganados, environmental organizations, and related governmental agencies to design a research project to study the effects of controlled grazing on wildlife areas. When the task force failed, Ganados initiated mediation sessions with environmental groups, hoping to build alliances around the idea that wildlife conservation depends on rural communities building sustainable economies.6

INCREASING INTERNAL INVESTMENT

Ganados del Valle established its own revolving loan fund, initially with philanthropic contributions, to supply the seed capital for enterprises it planned to set up or assist. Initially, access to the revolving loan fund was limited to business activities associated with raising sheep and wool processing. This allowed the organization to augment the potential for payback at the same time it was developing markets for lamb and wool. The partido, or livestock shares program, also served as a mechanism to build internal investment. The placement of sheep with new growers increased area agricultural activity and enabled cooperators to participate in the breeding, production, and marketing activities of Ganados del Valle. The requirement to return the number of sheep equal to the total number originally lent ensured that this unique investment program would eventually become self-reliant.

By 1989 Ganados del Valle’s revolving loan fund had grown from grants and returned interest to over $135,000. The number of sheep in the livestock shares program had grown from 150 to over 300. The program, however, got off to a slow start because of fluctuating markets for lamb and the lack of long-term summer grazing. The Pastores Lamb venture holds out promise of establishing a dependable regional market for specialty lamb, thus assisting in the growth of agricultural activity in the Valley.

CHANGING ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL STRUCTURES TO INCREASE OPPORTUNITY AND REDUCE DEPENDENCY

The organizers of Ganados del Valle believed that the commercial sheep industry had become excessively dependent on an export market that favored large-scale growers. Moreover, by 1980 the national sheep industry was in decline, bringing into question the wisdom of a development strategy based on growing and marketing lamb and wool. In the Chama Valley, however, sheep offered a unique opportunity for adding on value: lamb and wool were two diverse products to sell to local, regional, and national markets. Another reason for choosing this resource was that it was economically feasible for a greater number of families. Relatively little capital was needed to begin a flock, particularly if a family had access to a shares program. Work to increase the value of the wool, moreover, had been practiced for many generations in northern New Mexico villages.

Ganados del Valle introduced structural changes that responded to the specific problems of underdevelopment. First a broader market for lamb was found through a cooperative sheep producers’ tele-auction in the Pacific Northwest. Second, lamb and wool markets were redirected and diversified by producers and processers using cooperatives and other economic organizations. Third, the reorganization of production technologies and the transfer of skills encouraged spinoff and the growth of related enterprises. Finally, changes were brought about in the roles and perceptions of residents regarding what they can do for themselves, what women can do in business, the economic value of small family farms, and traditional cultural activities.

When Ganados del Valle had first been organized, business development experts advised against retailing wool products in the isolated Chama Valley. Ganados del Valle agreed. Both turned out to be wrong. Neither the leadership of Ganados del Valle nor the business experts considered the increasing visitor traffic through the valley. Nor did they understand what visitors were interested in seeing or buying. Ganados del Valle members and the Tierra Wool weavers came to find that visitors appreciated the area precisely because of its undeveloped state and the fact that a unique culture resided in the old adobe villages near the headwaters of the Rio Chama.

The beautiful earth-toned Churro yarn and the retail products into which it was woven filled a market need that built the Tierra Wools enterprise and created thirty-five new jobs in Los Ojos. As demand for other Tierra Wools products grew, opportunities for new businesses opened up. The wool-washing plant, the feed store and the general store have created six additional new jobs and increased the incomes of over thirty-five families. The old one-way street economy, which had been draining resources, dollars, and talent from the community, has begun moving toward sustainable self-reliance by establishing interdependent ties with the regional economy.

CONCLUSION

There are many strategies for the economic development of rural areas. Each one brings both advantages and disadvantages. The applicability and results of each approach vary according to a community’s unique situation, the characteristics of its resource base, its cultural values, its leadership, and other factors. Successful planning for an economy that is both sustainable and adaptable requires a clear understanding of the basic elements of self-reliance, as demonstrated in the Ganados del Valle case study. However, each community adopting a REP strategy must decide for itself which elements fit local conditions and opportunities for sustainable development.