15

The Legal Framework of Planning

BOTH THE RURAL ENVIRONMENTAL PLANNER and the citizens involved in planning in their community must have a working knowledge of the legal framework of planning. This is best obtained by a course of study on this subject, access to which may not be easy for many rural people. This chapter offers an introduction to such material. Its purpose is to inform rural residents of legal concepts and terms most likely to be encountered in planning their own community.

Lawyers and others involved in matters of law use special terms that have specific meanings and a long history of use and reference. The layman may have heard some of these terms but may not be quite sure what they mean. This chapter introduces and explains some basic legal concepts and related legal terms, then covers broader material such as state enabling legislation, the legal basis for planning and zoning, dedication, exactions, and the authority of planning commissions.

LEGAL CONCEPTS

An understanding of the following concepts can help rural citizens and their elected and appointed officials to make more effective use of lawyers and paralegal services when appropriate:

- Five types of law

- The legal concept of property

- The bundle of rights concept

- Partial rights in landed property

- Easements

- State enabling legislation: general and specific

- Methods of public control over private land

- Euclidean zoning

- Compulsory dedication of land

- Authority of planning commissions

FIVE TYPES OF LAW

The principal types of law are constitutional law, statutory law, common law, judicial law, and administrative law. Although each type enumerates a wide range of rights, including civil and human rights, this chapter will address only property rights and related property law. All property rights are ultimately vested in the sovereign authority of the state, which has a monopoly of force and so can enforce all rights and obligations within its borders. The sovereign state may delegate many of its rights to political subdivisions or to individuals. The delegation of authority may be expressed in constitutions, statutes, judicial decisions, or administrative decisions.

Constitutional law is embodied in the basic charter of the government. The charter enumerates the powers and responsibilities of the various branches of government and the rights of citizens, which the government is obliged to respect and protect. The federal constitution outlines the powers and duties of the various departments of the federal government, while state constitutions declare the powers of states and of their subdivisions.

Statutory laws are those established by the enactment of statutes, that is, by the legislature of the sovereign government. Both the federal and state legislatures enact laws by the authority granted them in their respective constitutions.

Common law comprises the body of legal principles and rules that derive their authority generally from precedents, that is, from usage and customs established over a long period of time or from the judgments and decrees of courts recognizing, confirming, and enforcing such usage. The term common law describes law that is not created by an act of legislature. In the United States, common law refers particularly to the ancient law of England. Common law usually covers areas of activity not covered by statutes or by constitutional law, but it may also cover other areas. Common law, for example, refers to judicial law established by the courts (sometimes including equity courts) in common law states. Common law states are those states that recognize common law in their constitutions. Additionally, statutory or judicial references to the old English common law may often be intended to include associated legislation. It should be stressed that common law is based on English tradition, as interpreted by courts in many sovereign states of the United States, not on the traditions of law, usage, and customs of other cultures within state jurisdictions.

Judicial law refers to law established by judicial decision. Constitutions, statutes, and common practice establish rules or actions of a general nature. Conflicts arise when there is disagreement or confusion concerning just how these laws should be applied in specific instances. The judge, in applying a law to a specific case, is interpreting the meaning of that law and hence “making law.” Judicial law is practiced most often in subject matters governed by little or no legislation.

Administrative law, important in the field of property rights, refers to decisions of government administrators that have the force of law (unless they are overthrown by the courts). Any administrator of a government agency charged with responsibility for resources, such as water or land of which the government is proprietor, is called upon to make day-to-day and long-range decisions concerning the allocation and use of that resource within the relevant statutes. For situations not anticipated by basic statutes, or for subjects authorized by such statutes, administrative decisions constitute a significant body of law. An example of administrative law would be a water resource department classifying water quality by administrative procedure.

THE LEGAL CONCEPT OF PROPERTY

Property, considered like family and religion one of the basic institutions of human society, has been a subject of study from time immemorial. It constitutes an aggregation of performances and forbearances that organize large sectors of human activity. Throughout history, wars have been fought in attempts to alter the conditions of landownership or property.

The legal concept of property consists of an aggregate of certain rights that are guaranteed and protected by the government. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, property is “the unrestricted and exclusive right to a thing; the right to dispose of a thing in every legal way, to possess it, to use it, and to exclude everyone else from interfering with it.”

There are three attributes of property. Property must have an object and an owner, and it must be protected by a sovereign state. The object is any resource that by its nature permits ownership and control. The owner is an individual, a corporation, a group of people, or any unit of government. The sovereign state embodying the will of all participants, has through its monopoly on the use of force (police power) the ability to guarantee the rights of ownership. The rights of the sovereign state may be divided and delegated among political subdivisions. For instance, the right to acquire property or easements by eminent domain may be delegated to the state highway department or to municipalities for the purpose of creating public access to property or to public waters. Responsibility for protecting private property rights may be exercised at the local as well as the state level.

There are a number of different types of property: common, public, qualified, and real property. Common property sometimes refers to land owned by a municipality. A municipal park is common property. Property owned jointly by a husband and wife under the community property laws of some states is also common property.

Public property or publici juris refers to those things owned by the public, that is, all the people in the state or community. For example, the public road system is public property.

Qualified property applies to chattels, that is, moveable possessions as distinguished from real estate. Chattels by nature are not permanent but can exist at some times and not at others. An example would be wild animals that a person has caught and kept. The animals belong to that person only so long as he or she retains possession of them. Qualified property is used to indicate the claims in any ownership which a person has when others also have claims to that property. For example, the owner of mortgaged land is a qualified owner.

Real property refers to land and generally whatever is erected, growing upon, or otherwise permanently fixed to that land. Because of its importance in all planning, including rural planning, real property is the subject of the remainder of this chapter. Rights in real property may be applied to the surface of the land, its subsurface, or the air (space) above it.

The state may own property in the same way as an individual does, but there are other rights reserved to the sovereign state (unless it delegates them) that do not apply to private owners. They are the rights of eminent domain and of escheat. Eminent domain is the right or power of the state to reassert, either temporarily or permanently, its control over any portion of the land of the state to meet a public exigency and for the public good. Escheat signifies a reversion of property to the state when there is no individual competent to inherit it. The concept of escheat, like many legal concepts, goes far back in history. The state is deemed to occupy the place and hold the right of the feudal lord.

There are both direct and indirect rights in land. Direct rights are those that apply specifically to a parcel of land, such as a lease right, that is, a limited right to use, and a mortgage or equity right, which means the complete right to use or dispose of a property by the owner. Indirect rights refer to those rights of the government that may be used to control the use of land. Some of the government’s indirect rights (or powers) are the power to tax, the power to spend for the common good and to regulate private activity for that purpose, the power to control interstate commerce, and the police power, that is, the right to do whatever is necessary to provide for the defense of the nation, the state, or other jurisdiction.

The owner of property is the person who has, or the agency of government that has, the right of disposition. A person may have only a small fraction of equity and may have leased the right of use, but if that person maintains the right of disposition, he or she is the owner of the property.

THE BUNDLE OF RIGHTS CONCEPT

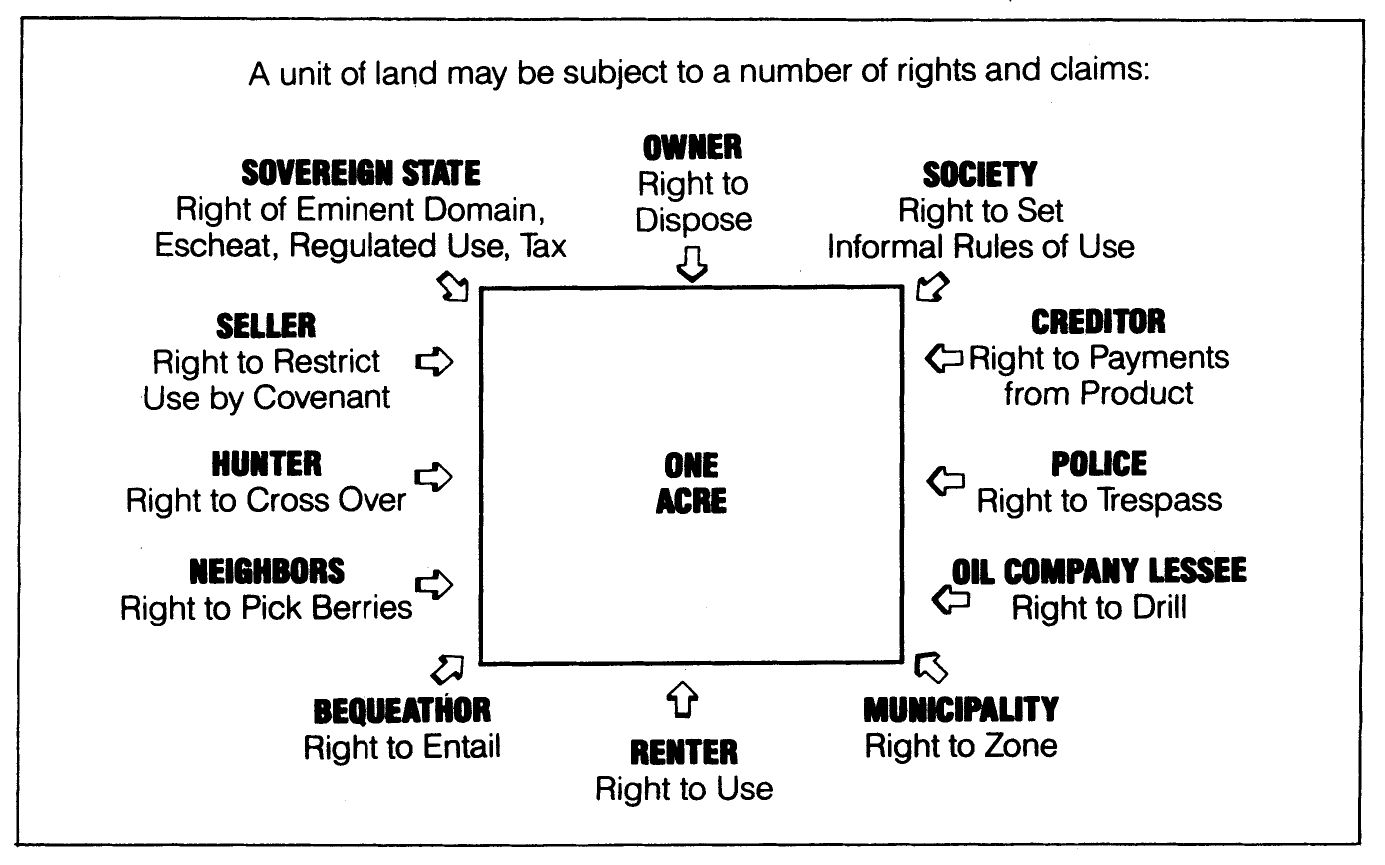

To explain the legal concept of property, rights in land are often likened to fasces, the symbol of authority of Caesar’s army (see fig. 15.1). The fasces is a bundle of sticks with an ax in the center. Each stick represents a land right while the ax represents the supreme authority of the state. The bundle of sticks may be divided into three smaller bundles: the right to use, the right to lease, and the right to dispose of. These three rights may be further subdivided. The right to use includes the rights to cultivate, to improve, to harvest growth, to not use, and in some cases, to use up or to destroy. The right to lease includes the right to lease to anyone the owner chooses under any of a great number of possible arrangements. The right to dispose of includes the right to sell all or part of the property or the interests therein, to bequeath it, to mortgage it, and to establish a trust.

PARTIAL RIGHTS IN LANDED PROPERTY

Fee simple ownership represents the largest number of rights concentrated in the hands of an individual. Fee simple means the possession of all rights save those reserved to the state. There are a number of partial rights in land that have various applications and are important for understanding landed property.

Deed conditions are special provisions in land title deeds that place limits or conditions on the use of land by the owner. Deed conditions must be consistent with social policy. For example, conditions that discriminate against ethnic groups cannot be placed on a subdivision. When certain rights are reserved, these conditions are called deed reservations. Examples are deeds to building lots that require a certain size and type and setback for any dwelling to be erected. Deed conditions are usually accompanied by reverter clauses that provide for the forfeiture of property whenever restrictive conditions are broken.

FIGURE 15.1. The Bundle of Rights Concept of Property I

A life estate is the possession and enjoyment of property during the lifetime of a person. At the end of that lifetime the property reverts to someone designated as the receiver of the estate. A life estate can be created by a trust document in a contractual arrangement.

A lease is a relationship created by contract that gives a tenant the right to possess and use property held or owned by a landlord or leasor. The tenant has a leasehold estate. The landlord retains a reversion interest. A mortgage, on the other hand, represents an encumberance on landed property by a borrower to a lender as security for the payment of a debt.

Land or purchase contract arrangements are used in some areas as a means for buyers with little capital to acquire rights to property. The buyer of a land contract gradually builds up equity in the property to the point where he or she converts the contract into a mortgage or, if all payments are made, assumes complete ownership. As long as the buyer continues to operate under a land contract, the title of property remains with the holder of the contract.

FIGURE 15.2. The Bundle of Rights Concept of Property II

A lien is the right of certain classes of creditors to sell a debtor’s property to satisfy some debt or charge.

EASEMENTS

Easements are very important to land-use planning. An easement is an agreement, usually permanent, that transfers one or more of a landowner’s property rights to another party. The concept of easement is based on the legal concept that property ownership consists of a bundle of rights. The right to cross another’s land, for example, has often been transferred through easements for access roads, irrigation ditches, or power lines. Easements can also be used as a means of protecting fish and game habitats and scenic areas and of creating public recreational facilities.

Both state and federal agencies have used easements to improve fish and game habitats and to acquire public hunting and fishing rights. For example, waterfowl hunting rights may be acquired along with the right to preserve wetland habitats for migration and to protect waterfowl areas from draining or filling. Public fishing rights are often acquired through stream bank easement along with the right to improve fish habitat using stream channel and stream bank devices.

Highway scenic easements are perhaps the best known and most successful use of the easement in land use planning. These easements often include prohibitions against timber cutting, billboards, and dumping, as well as restrictions on adjacent commercial establishments and residences. Highway scenic easements usually apply to areas covering the field of view from the highway.

A review of successful easement programs identifies six conditions that must be met for a program to be successful. First, an effective public relations campaign should be undertaken to make the program understandable and meaningful to landowners (and also to the courts). Second, there should be a provision for equitable compensation. As a rule of thumb, the value of the easement should equal the prior value of property minus the value resulting from the burden of easement. Third, landowners should understand exactly which rights are being transferred and which are being retained (many easement violations result from misunderstanding). Fourth, the terms of easements must be enforced. Fifth, notice must be provided of easement restrictions so that any new owner is aware of the assumed obligations. Sixth, easements should be permanent because renegotiation can be costly and because temporary easements sometimes negate the advantage of lower property taxes.

A number of benefits may accrue when these criteria are met: easement is often cheaper than fee simple purchase; the landowner performs maintenance unless otherwise stipulated; the land stays on the tax rolls; the landowner pays lower taxes; easements, being permanent, are not subject to amendment or variance; the landowner may get free title review; the landowner may get flank protection from neighbors who sell out; and conservation easements can cause land values to increase.

STATE ENABLING LEGISLATION

Careful study of state statutes relating to the powers, rights, and limits of local jurisdictions and citizens will pay substantial dividends in improving the ability of concerned citizens and rural planners to guide the community planning process. The examples and methods given in the following sections are common to and applicable in most jurisdictions of the United States.

The authority of town and county governments to act is granted by the state government. This authority, called enabling legislation, may be of two kinds, general and specific. In the establishment of municipal jurisdictions town officials are given general authority to do whatever in their judgment is in the interest of public health and general welfare. This blanket authority, which actually covers a wide range of activities in the public interest, including planning and zoning, is widely known as the police power.

Specific enabling legislation consists of state laws that grant subordinate jurisdictions special authority to perform specified functions. Specific enabling legislation is desirable because it removes the doubts that often arise when actions are taken on the basis of general enabling authority. For example, the conduct of planning and zoning is greatly facilitated by specific legislation authorizing the various steps in the planning and zoning process.

In 1928 the U.S. Department of Commerce published a standard city planning enabling act as a guide to planning. This act was quickly and widely copied by a great many states. Today most states retain some form of enabling legislation copied from that original Department of Commerce act. Sections 6 and 7, taken from that act and quoted below, demonstrate the extensive authority given to planning commissions:

United States Department of Commerce:

A Standard City Planning Enabling Act (1928)

Sec. 6. General Powers and Duties. It shall be the function and duty of the commission to make and adopt a master plan for the physical development of the municipality, including any areas outside of its boundaries which, in the commission’s judgment, bear relation to the planning of such municipality. Such plan, with the accompanying maps, plats, charts, and descriptive matter, shall show the commission’s recommendations for the development of said territory, including among other things, the general location, character, and extent of streets, viaducts, subways, bridges, waterways, water fronts, boulevards, parkways, playgrounds, squares, parks, aviation fields, and other public ways, grounds and open spaces, the general location of public buildings and other public property, and the general location and extent of public utilities and terminals, whether publicly or privately owned or operated, for water, light, sanitation, transportation, communication, power, and other purposes; also the removal, relocation, widening, narrowing, vacating, abandonment, change of use or extension of any of the foregoing ways, grounds, open spaces, buildings, property, utilities, or terminals; as well as a zoning plan for the control of the height, area, bulk, location, and use of buildings and premises. As the work of making the whole master plan progresses, the commission may, from time to time, adopt and publish a part or parts thereof, any such part to cover one or more major sections or divisions of the municipality, or one or more of the aforesaid or other functional matters to be included in the plan. The commission may, from time to time, amend, extend, or add to the plan.

Sec. 7. Purposes in View. In the preparation of such plan, the commission shall make careful and comprehensive surveys and studies of present conditions and future growth of the municipality and with due regard to its relation to neighboring territory. The plan shall be made with the general purpose of guiding and accomplishing a coordinated, adjusted, and harmonious development of the municipality and its environs which will, in accordance with present and future needs, best promote health, safety, morals, order, convenience, prosperity, and general welfare, as well as efficiency and economy in the process of development; including among other things, adequate provision for traffic, the promotion of safety from fire and other dangers, adequate provision for light and air, the promotion of the healthful and convenient distribution of population, the promotion of good civic design and arrangement, wise and efficient expenditure of public funds, and the adequate provision of public utilities and other public requirements.

PUBLIC CONTROLS OVER PRIVATE LAND

A common misconception is that the only method available for public control of private land is by purchase in fee simple or by zoning. It also is popularly held that purchase is too expensive and that zoning is of doubtful efficacy. In fact, there are many methods of public control over private property. The following list of techniques is a good basis for discussion of the appropriate method for each land-use recommendation. Some techniques are more applicable than others in specific situations. For example, designation may be the best method for protecting natural areas, conservation zones are effective for protecting wetlands, compulsory dedication can be applied to school sites, tax stabilization agreements may be used to keep land in agriculture, and federal licensing authority provides fishing and canoeing access to streams. Here are the various methods of exercising public control over private land:

Exercise of police power

1.Zoning (Euclidean, historic, and conservation)

2.Compulsory dedication

3.Subdivision regulations

4.Building codes

5.Health regulations

6.Antinuisance ordinances

7.Adopted master plan

8.Critical control policy

9.Growth control policy

10.Sewer and construction moratorium

Taxation

11.Preferential taxation

12.Tax stabilization agreements

13.Forest or other special resource tax law

Regulation

14.Development permit system

15.Land sales regulation legislation

Acquisition of rights

16.Purchase in fee

17.Purchase and lease-back

18.Lease

19.Gift

20.Condemnation (exercise of eminent domain)

21.Easements

Other

22.Nonpublic land trust agreements in which the public is a third-party beneficiary

23.Common law

24.Subsidies

25.Designation

26.Emergency powers

27.Site plan review

28.Federal or state licensing authority

EUCLIDEAN ZONING

The most common type of zoning in the United States is Euclidean zoning. It takes its name from the Supreme Court case Euclid, Ohio v. the Ambler Realty Company. This precedent-setting decision supporting the legality of zoning as practiced throughout the country was handed down in 1926. The Euclid v. Ambler case established zoning as a proper exercise of the police power, provided that state enabling authority exists, that zoning is not arbitrary or unreasonable, and that it supports public health, safety, morals, and welfare. By the end of 1928 zoning enabling laws had been enacted by forty-seven states. The finding and opinion in the Euclid case are presented later in this chapter.

COMPULSORY DEDICATION OF LAND

One of the most important planning tools is the requirement for compulsory dedication of land through the development process. Because of lack of familiarity this tool is little used in rural areas.

Throughout the history of the United States it has been considered the developer’s responsibility to furnish the land needed for streets and for public areas such as the town common, squares, parks, and public building sites. This was true in early colonial towns built in both the English and the Spanish traditions and later, in towns developed by railroad-backed land speculators. The practice was not merely a matter of custom. It was required first by royal charters, and then by charters granted by early state legislatures. In addition to statutory requirements, courts imposed a common law requirement that an owner dividing a parcel of land make adequate provision for access from existing streets to any interior lots. Whenever a developer is called upon to dedicate land, the facilities provided in this manner become a part of a package that the lot purchaser receives. Their cost is normally reflected in the price of the lot. Without minimum support facilities paid for at least in part by others, including streets, schools, and fire protection, there would be very little market for lots at all. Many developers find that providing extras such as parks and school sites results in a larger return on their investment.

Two Supreme Court decisions of 1987, known as the Nollan and First English cases, emphasize the need for care in defining the timing of and the requirements for land dedication of easements serving community goals. These cases, discussed later in this chapter, more fully define conditions limiting exactions and just compensation for takings.

THE AUTHORITY OF PLANNING COMMISSIONS

The legal authority of small-town planning commissions and rural residents, without the assistance of community planners and without legal counsel, is often challenged, bluffed, or threatened. For example, if a parcel of land would be affected by a proposed zone change that the owner regards as undesirable, the owner, or a person representing the owner, may tell the planning commission that it does not have the authority to take such action or may threaten to sue it. Though the charge may be unfounded, it can still be effective if the planning commission is unclear about its prerogatives.

Statutes in most states list the specific actions planning commissions are authorized to take. The key to good planning is just and equitable application of these statutes. For example, in Vermont the actions available to planning commissions are specifically authorized by statute. Planning commissions there, as in most states, are able to:

- Promote public health

- Promote public safety

- Promote public morals

- Promote prosperity

- Promote comfort

- Promote convenience

- Promote efficiency

- Promote economy

- Promote general welfare

- Eliminate present land development problems

- Provide space for forests

- Provide space for agriculture

- Provide space for residences

- Provide space for recreation

- Provide space for commerce

- Provide space for industry

- Provide space for public facilities

- Provide space for semipublic facilities

- Protect forests

- Protect soils

- Protect birds (that is, other natural resources)

- Preserve open space

- Provide a sound economic base

- Protect historic features

- Enhance the Vermont scenery

- Distribute population

- Provide jobs

- Guard against overcrowding

- Prevent traffic congestion

- Prevent loss of peace

- Prevent loss of quiet

- Prevent loss of privacy

- Reduce noise

- Reduce air pollution

- Reduce water pollution

- Provide for transportation

- Facilitate provision of water

- Provide for sewerage treatment

- Facilitate provision of schools

- Facilitate provision of parks

- Regulate growth

- Encourage the most desirable use of land

- Minimize the adverse impact of one land use on another

Vermont statutes authorize planning commissions to take any “reasonable” action to protect the public interest, if they have public support, that is, if public support outweighs public opposition. Reasonable is a commonly used legal term meaning what the majority of people would call reasonable if the question were raised in a court of law, and if people qualified as respected members of the community were asked to give their opinion. Public interest is that which benefits public health, safety, and welfare in the judgment of an elected council or their representatives.

Public support is not a legal requirement but rather a social or political condition. For example, it might be reasonable and in the public interest for the planning commission to propose the fluoridation of water. However, if a large, vocal group of townspeople opposes fluoridation it might be unwise politically for the planning commission to require it. Not only would it be unsuccessful, it would also erode if not destroy the credibility and usefulness of the planning commission. In fact, town officials are more likely to be guided or restrained by political or social considerations and pressures than by legal requirements.

While planning commissions in most jurisdictions are authorized to work for and promote specific public actions, unless authority has been specifically delegated by the elected board, their actions are only recommendations to that board or to the council. Elected administrators may either approve or disapprove them.

The Supreme Court of the United States is the final arbiter in interpreting the meaning and application of laws in this country. Because of their importance to the application of laws related particularly to planning and zoning in rural areas, three cases argued before the Supreme Court, one in 1926 and two in 1987, are discussed here.

CASE: EUCLID V. AMBLER REALTY COMPANY

This case, argued before the Supreme Court in 1926, concerned a zoning ordinance in Euclid, Ohio. Now called Euclidean zoning, it described traditional zoning categories utilized by many local governments. The entire area of Euclid, Ohio, was divided by the zoning ordinance into six classes of use districts. The six use districts were classified with respect to the type of buildings that could be erected within their limits and to possible construction densities. The ordinance also included a seventh class of use that was prohibited altogether.1

The ordinance was challenged by the Ambler Realty Company on the grounds that it violated section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution. The realty company charged that the ordinance deprived it of liberty and property without due process of law, denied it equal protection under the law, and offended against certain provisions of the constitution of the state of Ohio. Ambler Realty claimed that the ordinance attempted to restrict and control the lawful uses of its land, which amounted to a confiscatory taking by destroying a great part of its value. As such, it violated the constitutional proscription against uncompensated takings.

The U.S. Supreme Court resolved the case by raising and addressing two questions. One was the general use of police power in zoning, the other the specific question involved in the case at hand. The court found that decisions by state courts were numerous and conflicting, but those that supported the use of police power in zoning greatly outnumbered those that denied it altogether. It also discovered a tendency to increasingly broaden the approved use for which police power restrictions may be imposed. The court agreed that there is an important and fine dividing line between the use of police power in the public interest and confiscating the land without adequate justification or compensation.

The opinion stated that before a zoning ordinance could be declared unconstitutional, its provisions had to be shown to be clearly arbitrary and unreasonable and to have no substantial relation to public health, safety, morals, or general welfare. The court held that the ordinance’s general scope and dominant conditions constituted a valid exercise of authority.

CASE: NOLLAN V. CALIFORNIA COASTAL COMMISSION

The Nollan decision of 1987 involved the issue of whether a property exaction, in this case a compulsory land dedication in the form of an access-easement requirement imposed by the California Coastal Commission, violated the Fifth Amendment’s taking clause.2 The Nollans, property owners, applied for a coastal development permit to replace their bungalow with a larger single-family house. The Coastal Commission, by an enabling statute, recommended that the permit be granted subject to an exaction that the Nollans allow the public an easement to the beach.3 The public purpose served by the exaction was to protect the public’s “visual and psychological access to the beach.”4 The Nollans objected, claiming that the exaction violated the Fifth Amendment’s prohibition against taking private property for public use without just compensation.

The Supreme Court held that the Coastal Commission’s exaction requirement did indeed violate the Fifth Amendment. In doing so, the court enunciated a new constitutional test for exactions: an exaction had to “substantially advance a legitimate public purpose” if the permit condition served the same public purpose that justified the denial of the permit.5 This requirement (as described by the dissent) involved a two-step analysis.6 First, would the condition imposed violate the Fifth Amendment? Second, if so, would requiring it in the form of an exaction alter the outcome? Under this analysis, the court found that if the commission had required the Nollans to convey the beach easement, it would constitute a taking.7 Next, the court stated that the public purpose underlying the exaction requirement failed to further the end advanced as the justification for the prohibition.8

The ramifications of this finding require a more careful look at exactions for planning actions in all jurisdictions, including rural communities and counties. Exactions had been described, prior to the Nollan case, as the new “hero” and the “hottest issue” in land-use planning.9 Nearly 88 percent of the nation’s municipalities employ some form of exaction.10 There are four basic types: compulsory land dedication, compulsory physical improvement, cash payment in lieu of land dedication, and impact fees. Each type of exaction is used as a police power tool to require developers to contribute to infrastructure as a condition of plat or permit approval.11

CASE: FIRST ENGLISH EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN CHURCH OF GLENDALE V. THE COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES

Further definition of the appropriate powers and limits of exactions was provided by the Supreme Court in this 1987 case.12 It addressed the concern of temporary taking and defined the remedy for regulatory taking, in this case as compensation. The First Evangelical Lutheran Church of Glendale, California, purchased 21 acres in the Los Angeles National Forest, 12 acres of which were flat land along the banks of Mill Creek.13 This property, known as Lutherglen, was used by the church as a retreat center for handicapped children. In 1978, after a fire deforested 3,600 acres upstream, serious flooding destroyed the buildings at Lutherglen. In 1979 Los Angeles adopted an ordinance forbidding reconstruction of the buildings within an interim flood protection area along Mill Creek. Lutherglen was located within this protected area.

The church instituted a suit alleging that the ordinance violated the Fifth Amendment’s taking clause. The Supreme Court addressed not the issue of whether a taking occurred but only the question of what remedy was available to a plaintiff alleging a regulatory taking. The court found that the remedy for a temporary regulatory taking of property is compensation, not merely invalidation or recision of the regulation or ordinance.14 Moreover, the court indicated that compensation may extend to a “much earlier” date, when interference with the use of property started.15

CONCLUSION

The conduct of REP requires a general knowledge of planning law. It is more reasonable and efficient for a citizen or rural planner to gain at least a functional understanding of planning law than to expect a lawyer to learn about planning rural communities. A rural citizen’s or planner’s need to understand planning law is similar to an individual’s need to understand medicine. Everyone need not be a doctor, but the more first aid and health science a person knows, the more that person can help in a crisis and the better equipped that person is to call on a specialist at the appropriate time.

The law is intended to be a common tool and guide enacted by and for laypersons, not an arcane system accessible only through the intercession of specialists. Experts are called in when there are questions of law that laypersons cannot answer. If a rural environmental planner, an interested citizen, or a planning commissioner is familiar with state enabling statutes and with significant federal legislation and key court cases, the local planning process will proceed more smoothly. The planner or citizen with a working knowledge of planning law will know how to distinguish a legal question from a planning question.

State statutes are bound into volumes, carefully indexed, and regularly updated and summarized; they are available in public libraries, state universities, and many community colleges. In small communities or remote areas without a public library, information on specific statutes or laws pertaining to a general area of concern can be requested through local agencies such as the town council or county commission.16