Chapter 1

Chapter 1

Chapter 1

Chapter 1

In 1945 Flannery O’Connor, a twenty-year-old graduate of Georgia State College for Women, made a trip north to inquire about admission to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Brad Gooch recounts the initial meeting of O’Connor and Paul Engle, the workshop’s director:

When she finally spoke, her Georgia dialect sounded so thick to his Midwestern ear that he asked her to repeat her question. Embarrassed by an inability a second time to understand, Engle handed her a pad to write what she had said. So in schoolgirl script, she put down three short lines: “My name is Flannery O’Connor. I am not a journalist. Can I come to the Writers’ Workshop?”1

This was not the first or the last time that someone would have trouble understanding O’Connor; while Engle, after reading her stories, immediately recognized her talent, literary agents, publishers, screenwriters, editors, and, of course, reviewers from the first have responded to her work in a number of ways, often lauding her talent but sometimes puzzled by, or downright hostile to, her work. The reception of Wise Blood over the course of two different publishers’ releases of the novel, separated by the span of ten years, reflects the ways in which an initial befuddlement can be forgotten in the wake of a new critical understanding.

In Before Reading: Narrative Conventions and the Politics of Interpretation, Peter J. Rabinowitz charts the actual process of reading and then categorizes various rules that readers follow when making sense of a text. He knows that reading is a messy endeavor, a “complex holistic process in which various rules interact with one another in ways that we may never understand, even though we seem to have little difficulty putting them into practice intuitively.”2 Rabinowitz calls the first of these “rules of notice”: since a text offers an overwhelming amount of data, readers need to privilege certain details at the expense of others. The notion that every word of a text is as important as any other has been argued by many, especially in light of the New Critics, whose methods were mimicked for decades in classroom close-reading exercises. Rabinowitz, however, contends that “the way people actually read and write” is by creating what Gary Saul Morson calls “hierarchies of relevance that make some of [a text’s] details central and others peripheral.”3 Rules of notice “tell us where to concentrate our attention” and offer “the basic structure on which to build an interpretation,” since “interpretations start, at least, with the most notable details.”4 Rules of notice concerning titles, for example, suggest where a reader should focus his or her attention before reading—hence Rabinowitz’s own title, which perfectly illustrates the very phenomena he describes. Knowing the title of Macbeth, for example, adds weight to the words of the witches and soldiers in the opening scenes when they mention the title character’s name, just as Hemingway’s choice of The Sun Also Rises as a title instructs readers what to notice in terms of the universality of his thematic concerns. In short, rules of notice help readers begin to make meaning out of a mass of information.

A comparable phenomenon occurs when reviewers tackle a work by an unknown author. A broad survey of representative examples from the original reviews of Wise Blood, first published by Harcourt, Brace in 1952, suggests that O’Connor’s reputation was initially formed according to critical rules of notice governing what was worth observing about an unknown author, or one at least unknown outside the local scene. In this case, instead of rules of notice governing titles, openings, and closings, reviewers followed rules of notice involving age, gender, and geography. What O’Connor’s original reviewers found important—what they noticed about her and her first novel and what they urged their readers to notice in turn—reveals some of the assumptions about authorship shared by these reviewers and how the groundwork for O’Connor’s reputation was laid. Nobody today could write a review of a newly discovered manuscript by Joyce or Faulkner without drawing on, directly or indirectly, the complicated reputations of these two figures. Even readers only vaguely familiar with these writers and who have never read a word of their work may already know that they are identified with specific places, that they are prized by the academy, and that they wrote “difficult” novels. Such is one effect of rules of notice being applied to a writer’s career as well as his or her work—and how, once established, what is noticed begins to help create a reputation. All the watchwords and phrases that O’Connor’s critics would employ for the next fifty years are present in the original reviews of Wise Blood, although there is, as we shall see, an important part of O’Connor’s current reputation that is almost entirely absent.

The first rule of notice that many reviewers followed was treating O’Connor’s age as if it were a definitive quality. The New York Herald Tribune Book Review, for example, called O’Connor a “Young Writer with a Bizarre Tale to Tell,”5 and Newsweek called her “perhaps the most naturally gifted of the youngest generation of American novelists.”6 One of the earliest reviews ends, “Her book is dedicated to her mother,”7 suggesting O’Connor’s youth and her first foray into the world of publishing as the little girl striving to please her parent. Other reviewers linked O’Connor’s youth to her southern identity, treating her as a type rather than an individual. Noticing geography—and asking readers to notice it, too—would presumably allow a reader to better understand O’Connor and why she wrote about figures as odd as Hazel Motes. The opening sentence of John W. Simons’s review in Commonweal—“This is the first novel of a twenty-six year-old Georgia woman”8—implies that age and region are elements with meanings and associations too obvious to warrant explanation. The reviewer notices them for the reader, who then uses them to begin forming opinions of the subject’s work. The original reviews are filled with mentions of O’Connor’s southern roots, regardless of whether the review is one that lauds or dismisses the novel. For example, William Goyen’s assessment in the New York Times Book Review begins, “Written by a Southerner from Georgia, this first novel, whose language is Tennessee-Georgia dialect expertly wrought into a clipped, elliptic, and blunt style, introduces its author as a writer of power.”9 An unnamed critic writing in Newsweek praised O’Connor’s previous work as original but also revealed his position as a northerner who brought to Wise Blood certain assumptions about the South: “In 1946 she attracted the attention of advance-guard critics with a story in a little magazine, Accent. In fact, she originated a curious kind of extremely personal fiction, odd little stories about Southerners who were backward but intelligent, brutal but poetic, like hardboiled Emily Dickinsons.”10 That southerners could be as complex as the Belle of Amherst was, apparently, some kind of revelation. Such an innovation was striking enough to Martin Greenberg, who noted in American Mercury that while Wise Blood was “full of violence, primitivism, degeneracy, and decay” and “smack in the tradition of Southern fiction,” it overleapt the supposed limits of its genre:

I was astonished to discover as I read along in the story, it is also a philosophical novel, a very rare bird in this genre of writing. I don’t mean to imply by this that there are no Big Ideas in the works of Faulkner. There are, but only implicitly and as it were unwittingly, and the reader has to get them out of the story for himself; whereas the elements of Wise Blood’s story . . . are manipulated to yield an idea directly.11

A writer across the Atlantic offered a similar observation when the novel was first issued by the London publisher Neville Spearman in 1955: “Miss Flannery O’Connor is one of those writers from the American South whose gifts, intense, erratic, and strange, demand more than a customary effort of understanding from the English reader. . . . Miss O’Connor may become an important writer.”12 Again, the reviewer leads with what he finds worthy of notice: O’Connor as a southern author who, like others from the same place, makes particular demands on readers outside of that region.

One reason for so many mentions of O’Connor as a southerner—why this fact was often emphasized as another rule of notice—had to do not only with the novel’s setting of Eastrod, Tennessee, but with an assumption about southern art that had been trumpeted decades before O’Connor began her career. In 1917 H. L. Mencken’s famous (or notorious) essay, “The Sahara of the Bozart,” appeared in the New York Evening Mail; the title (with its phonetic spelling of “beaux arts”) reflects Mencken’s view of the land of cotton as a cultural wasteland: “Down there a poet is now rare as a philosopher or an oboe-player. The vast region south of the Potomac is as large as Europe. You could lose France, Germany and Italy in it, with the British Isles for good measure. And yet it is as sterile, artistically, intellectually, culturally, as the Sahara Desert. It would be difficult in all history to match so amazing a drying-up of civilization.”13 Mencken further states that James Branch Cabell was the only southern novelist “whose work shows any originality or vitality” and that, in his life as an editor, he has found betting on the appearance of the Great Southern Novel a losing proposition:

Part of my job in the world is the reading of manuscripts, chiefly by new authors. I go through hundreds every week. This business has taught me some curious things, and among them the fact that the literary passion is segregated geographically, and with it the literary talent. . . . The South is an almost complete blank. I don’t see one printable manuscript from down there a week. And in my more than three years of steady reading the Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Florida and Tennessee have not offered six taken together. (493)

Mencken’s reason for this dearth of talent—that “the civil war actually finished off nearly all the civilized folk in the South and thus left the country to the poor white trash, whose descendants now run it” (493)—might have been contested at the time, but his assumptions concerning the South were held by many readers and reviewers when Wise Blood was first published. Edward S. Shapiro has examined the ways in which the assumptions that undergirded Mencken’s essay later motivated the Fugitives and Southern Agrarians, noting, “The Agrarians were amazed and horrified by these bitter attacks on the South by Mencken and his imitators. Even more shocking was their acceptance by much of the country as an authentic picture of the South.”14 Decades of such acceptance, fostered in part by Frank Tannenbaum’s The Darker Phases of the South (1924), Walter White’s Rope and Faggot: A Biography of Judge Lynch (1929), and W. J. Cash’s The Mind of the South (1941), reinforced many readers’ impressions of the region. O’Connor’s home state was thus very much viewed as worthy of notice, a key part of her identity, and the cornerstone of her burgeoning reputation. But it was also a part of her newly forming reputation about which the author often complained. In a 1955 interview, O’Connor stated that Wise Blood was not “about the South” but about more universal truths: “A serious novelist is in pursuit of reality. And of course when you’re a Southerner and in pursuit of reality, the reality you come up with is going to have a Southern accent, but that’s just an accent; it’s not the essence of what you’re trying to do.”15 Still, O’Connor could be defensive of the South when she felt it was being trampled underfoot: in a 1963 letter describing the publication in the New Yorker of Eudora Welty’s “Where Is the Voice Coming From,” a fictional treatment of the murder of Medgar Evers, O’Connor fumed, “What I hate most is its being in the New Yorker and all the stupid Yankee liberals smacking their lips over typical life in the dear old dirty Southland.”16 O’Connor accepted the fact that her reputation would always be a function of her being a southerner. What she resented, and what surfaces in some of the early reviews, is how “southern” became a watchword connoting backward, regressive social policies and antimodern attitudes, an assumption that some contemporary readers still bring to O’Connor’s work.

Almost as if they had anticipated a response in the urban press that treated Wise Blood as a hard-hitting exposé rather than a work of the imagination, southern reviewers used their reviews as occasions to suggest that the South was in fact a place of culture and sophistication. One of O’Connor’s first notices in the press was local: the Milledgeville Union-Recorder blazoned O’Connor’s entry into the literary marketplace with the headline, “May 15 is Publication Date of Novel by Flannery O’Connor, Milledgeville.” Noting that Wise Blood had been acquired by Harcourt, Brace, “one of the country’s leading publishing houses,” the piece quotes Caroline Gordon’s praise of the novel and revealingly introduces Gordon as a “New York Critic”17 rather than the wife of Allen Tate. The implication here is that even a Yankee could not deny the talent of this southern artist; the review is more of a press release than a critical evaluation. Like later reviews, the piece mentions O’Connor’s age; unlike other reviews, however, the piece mentions O’Connor’s southern roots as part of her artistic pedigree and indicators of an implied future success. Similarly, the Atlanta Journal and Constitution used the upcoming publication of Wise Blood as an example of southern cultural superiority: its headline, “Miss O’Connor Adds Luster to Georgia,” suggests that O’Connor was worthy of praise for defeating the very assumptions articulated by writers like Mencken. The opening sentence, “Georgia’s vitality in the field of literature continues, a fact which is brought to our attention by an autograph party being given by the Georgia State College for Women for Miss Flannery O’Connor,”18 reveals the true subject of the article to be the worthiness of southern writers and their importance to the national literary scene. The article ends praising O’Connor’s individual talents and those of Georgians as a whole: “We congratulate her as another in the list of Georgians who by production of first-rate writing keep Georgia’s name before the nation in a favorable and commendable light.”19 Upon the novel’s release, the Atlanta Journal and Constitution again touted O’Connor as a local hero: “In a novel whose overtones are chilling and whose horror is undiluted, Georgia introduces an extraordinary talent.”20 But even this piece of puffery contains a moment where the writer indulges in the fostering of a southern stereotype, noting that “the very same goblins” that plague the characters “might ‘git’ you!”21 In general, the publication of Wise Blood was likened in the southern press as akin to the debutante’s entrance at a cotillion. The reviewers also implied that critics in the North were not the unquestionable arbiters of artistic quality.

If O’Connor’s age and address proved surprising to some reviewers, her gender proved more so. The Newsweek piece compounds clichés about the South with those concerning young, female novelists: “In her personal life,” it states, “Miss O’Connor is warm and pleasant, with a soft Southern drawl, but nobody will ever guess it from her stories.”22 Such an assumption about what one might “guess” about an author’s gender informs Martin Greenberg’s review in The American Mercury —the journal founded by Mencken in 1924—in which he offers what stands as the most left-handed compliment in O’Connor’s early reception: after declaring that “the author of Wise Blood clearly has great gifts,” he qualifies his praise by adding, “You would never guess from the vigor and boldness of the writing that Flannery O’Connor is a woman.”23 Such a backhanded compliment was also given by Evelyn Waugh, who, when asked for a blurb for the dust jacket, responded, “If this really is the unaided work of a young lady, it is a remarkable product.”24 Greenberg’s parting shot, that some of the novel’s strained humor might be “chalked up to the writer’s youthfulness,”25 allows his review to stand as a representative example of the initial positive response to Wise Blood: a noteworthy first novel, especially when one considers the age and gender of its source.

O’Connor herself had little concern with her identity as a female author: she once dismissed the entire topic by cracking, “I just never think, that is never think of qualities which are specifically feminine or masculine. I suppose I divide people into two classes: the Irksome and the Non-Irksome without regard for sex.”26 Her reviewers, however, thought otherwise—as did O’Connor’s mother, Regina, who asked her daughter to write an introduction to the novel so that Katie Semmes, the novelist’s eighty-four-year-old cousin and a social doyenne, would not be upset by the novel’s content. O’Connor soon complained to Sally and Robert Fitzgerald, “This piece has to be in the tone of the Sacred Heart Messenger”27 and never composed it. In his biography of O’Connor, Brad Gooch recounts the horrified Cousin Katie (as she was called) “penning notes of apology to all the priests who had received copies” and reacting, like O’Connor’s aunt Mary Cline, in a “horrified and theatrical” manner to Wise Blood’s frank portrayal of the whore, Mrs. Leora Watts, and Sabbath Lily Hawks, the fifteen-year-old whom Motes also beds during the course of his twisted pilgrimage. O’Connor’s college writing instructor was shocked by her student’s first work for its inclusion of such objectionable material, and other “ladies who lunch in Milledgeville” were horrified by what they read because it came from the pen of one who they thought should have known better. Even a contemporary admirer of Wise Blood, an editor for the Alumnae Journal of the Georgia State College for Women who knew O’Connor and had once commissioned her cartoons, noted, “What to do? Everybody liked the child. Everybody was glad that she’d gotten something published, but one did wish it had been something ladylike.”28

The original reviews are also notable for establishing one of the most widely used pieces of critical shorthand, the antithesis of “ladylike,” which would be used by both critics and O’Connor herself for the rest of her career. Anyone who studies O’Connor at any length cannot avoid encountering the word “grotesque,” frequently used as a noun to describe O’Connor’s characters and as an adjective to describe her style; the word has gained such currency that a Los Angeles Times article on what would have been her ninetieth birthday was headlined, “Happy birthday Flannery O’Connor, avatar of the Southern grotesque.” Derived from the Italian grottesca, the word originally described the fantastic and highly ornamental visual style of Nero’s Domus Aurea, discovered in the Renaissance. Literary critics employ the term more often than they define it. In his edition of Montaigne’s Essays (1603), John Florio translated the opening of “On Friendship” as follows:

Considering the proceeding of a Painters worke I have, a desire hath possessed mee to imitate him: He maketh choice of the most convenient place and middle of everie wall, there to place a picture, laboured with all his skill and sufficiencie; and all void places about it he filleth up with antike Boscage [ornament] or Crotesko [grotesque] works; which are fantasticall pictures, having no grace, but in the variety and strangenesse of them. And what are these my compositions in truth, other than antike workes, and monstrous bodies, patched and hudled up together of divers members, without any certaine or well ordered figure, having neither order, dependencie, or proportion, but casuall and framed by chance?

Two hundred years later, William Hazlitt lectured, “Our literature, in a word, is Gothic and grotesque; unequal and irregular; not cast in a previous mould, nor of one uniform texture, but of great weight in the whole, and of incomparable value in the best parts.”29 In American literature, the word’s most notable appearance is in the title of Poe’s 1840 story collection, Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque, which does not explicitly define the term, the author more interested in rhyming than defining. Almost sixty years later, Sherwood Anderson would title his introductory episode in Winesburg, Ohio “The Book of the Grotesque.” In all these examples, the word suggests variety, contradiction, asymmetry, and strangeness, and a tension between form and content: qualities that theorists of the grotesque have illuminated for centuries.30 These examples lack any of the negative connotations the term might carry in casual, contemporary conversation, but in some reviews of Wise Blood, critics used it as a means to express their disapproval of O’Connor’s style and subject.

The watchword “grotesque” makes its first appearances in conjunction with O’Connor in these reviews and has only gained momentum as a means by which critics explore her work: a 2015 search of the MLA International Bibliography reveals over eighty books, articles, and dissertations concerning O’Connor and the grotesque. It first appeared in a short, unsigned, and dismissive review in the pages of the Bulletin from Virginia’s Kirkus’s Book Shop Service in May 1952. After describing each of Wise Blood’s characters and recounting Hazel Motes’s fate, the reviewer states: “A grotesque—for the more zealous avant-gardists; for others, a deep anesthesia.”31 Here, the term is used disparagingly, suggesting that Wise Blood is not a novel but some other, lesser form appealing to only a small part of the reading public. However, this reviewer’s attitude toward the grotesque was not dominant among the initial reviewers, most of whom used the term, even when not defining it, to describe what they found difficult to characterize. For example, the Savannah Morning News described the “excruciating directness” and “graphic manner” of the novel before stating that the novel works by “sweeping the reader from one grotesque and baffling situation to another.”32 The New York Herald Tribune Book Review praised the novel as “a tale at once delicate and grotesque,”33 the critic here expressing surprise at O’Connor’s care in creating a novel featuring raw emotion and violence.

Other reviewers used the term to suggest the extremes to which O’Connor took her characters and readers: one noted that, in the course of the plot, “occasional comedy yields to the grotesque, and the grotesque to horror”34 while another noted, “Grotesques, to hold interest, must be extra convincing” and complained that O’Connor’s “outrageousness” is “mere sordidness.”35 R. W. B. Lewis wrote, “The characters seem to be grotesque variations on each other” while complaining about the novel’s “horridly surrealistic set of characters,”36 revealing his assumption that if a novel’s characters are grotesques, the putatively normal reader is unable to share in their struggles. Perhaps—but again, the watchword “grotesque” is used here as if it illuminated, rather than obfuscated, O’Connor’s artistic performance; the same can be said for “horridly surrealistic,” a phrase that does not accurately describe Wise Blood or any of O’Connor’s work. Calling O’Connor’s characters “grotesques” is a way of sounding specific while sidestepping the critical challenge of describing such figures as the dimwitted Enoch Emery or the penitent Hazel Motes. As we shall see with those who labeled Wise Blood a “satire,” many reviewers responded to the strangeness of O’Connor’s work by trying to quantify that strangeness and bring it to heel. Like Justice Potter Stewart when faced with the challenge of defining “obscenity,” critics did not define “grotesque” but spoke as if they knew it when they saw it.

Only Carl Hartman, writing in the Western Review, gave the grotesque its due. His review begins with a quick manifesto on the grotesque that is perhaps the single most useful approach to O’Connor’s use of grotesque characters and situations. His explication of what constitutes the grotesque and the artistic challenges it presents can be read as a corrective to his fellow reviewers, who used the term indiscriminately:

That which is merely distorted or merely horrible or merely funny is not grotesque; that which is grotesque must, to exist as such, remain always on a very fine line somewhere in between the divergent forces which comprise and orient its grotesqueness. The grotesque must be held in its artistic place, so to speak, through the tensions of its own almost diametrically opposed qualities—through, for example, the juxtaposition and combining of ugliness with beauty, reality with unreality, normalcy and abnormality, humor with the distinctly unfunny. And these conflicting elements, whatever they may be, must be synthesized in such a way that their final emphasis is that of a true and special amalgam, not a hodgepodge. A slight push too far in any single direction . . . will send the whole structure toppling.37

The Misfit and Hugla, Rayber and Old Tarwater, Rufus and O. E. Parker are all prefigured in these remarks. Hartman knew and articulated what others did not: that O’Connor was an artist who perfected the use of such striking combinations, of which the human and the divine make the ultimate example.

Finally, the original reviews of Wise Blood offer an array of allusions: by examining the writers to whom she was compared, a contemporary reader can better understand the original reviewers’ difficulty in characterizing a writer as singular as O’Connor. Again, many responded to her strangeness by attempting to limit it, often by comparing her to more widely known authors. Unsurprisingly, her work was frequently compared to that of Faulkner and Carson McCullers, and her characters were compared to those of Erskine Caldwell—the last comparison mere cultural shorthand and surely not any great compliment to O’Connor. Other comparisons were more attuned to the values and assumptions that informed O’Connor’s art: her debt to Dostoevsky, for example, was mentioned by several reviewers.38 Others perceptively noted the thematic similarities between the novel and “The Hound of Heaven,” Francis Thompson’s poem about a Christ-haunted renegade, as well as the characters’ similarities to those created by (predictably) Poe, (interestingly) O’Neill, and (improbably) Steinbeck.39

Wise Blood was also placed—in its very first and many subsequent reviews—“in the tradition of Kafka,”40 both as a means of praise and of attack: one of the most cutting remarks about the novel was that it reads “as if Kafka had been set to writing the continuity for Lil’ Abner.”41 Perhaps Caroline Gordon, whose instincts O’Connor trusted absolutely, fostered such a notion, since she described and praised the novel as “Kafkaesque” in her original dust-jacket blurb, surely to do her friend a favor and place the novel in the realm of the respectable. But does such a term truly reflect the novel? “Kafkaesque” suggests a world filled with great struggles and questions, but few results and fewer answers. The world of Wise Blood is just the opposite: there is a narrative center that ultimately gives meaning to Motes’s struggles and without which the novel is a series of escalating and empty horrors. The Haze who stumbles in darkness at the end of the novel, wrapped in barbed wire and knowing that he can no longer flee the Hound of Heaven, would never compare himself to Joseph K. or Gregor Samsa. As Motes tells his landlady, “There’s no other house no nor other city” to which he intends to flee.42 His actions are filled with a degree of meaning that even the blind can see.

The question remains what the original reviewers thought of the book’s themes and what they identified as Wise Blood’s important issues. The very first of O’Connor’s reviewers, writing in Library Journal, remarked that the novel “is about the South” and “southern religionists,”43 as if the complicated definition of the first topic was readily understood by all readers and the types mentioned as the second topic were obvious and recognizable at first glance. Another reviewer stated that Motes’s struggle becomes “the vehicle for some wry commentary on life”44—a statement only slightly less vague than the one previously quoted but of a piece with a number of reviews that spoke of the novel’s themes in only the most general terms. Other reviewers, dodging their duty of evaluating the work and justifying their opinions, simply retold the plot, scene for scene, including the shocking surprise of Motes’s self-blinding and death. A reader of Wise Blood’s original reviews will be struck by how often reviewers gave away these crucial moments in the novel, seemingly stymied by O’Connor’s form and content. Surely, Motes’s self-blinding is meant to shock the reader as much as it does his landlady—and the effect of such shock on the reader is part of what makes O’Connor’s art so disconcerting and powerful. To inform the reader of such an event makes an indirect admission that Wise Blood had proven too strange for some readers, who responded to the strangeness by exposing it and robbing it of its bite. As she later remarked, “To the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost-blind you draw large and startling figures.”45 Reviewers who gave away the twists of the plot were taming the fiction, making the “startling figures”—however grotesque—less large and less startling by depriving them of their shock, affecting O’Connor’s early reputation by portraying her as a writer who offered gruesome grotesques for their own sake rather than one who employed such characters with the goal of dramatizing complex spiritual issues.

Most surprising is that only a single original review of Wise Blood mentions O’Connor’s Catholicism or the Catholic themes of the novel—a rule of notice and defining aspect of her reputation that today seems impossible to forget or avoid. O’Connor is as identified as a Catholic novelist today as automatically as Philip Roth is labeled a Jewish one—so automatically, in fact, that one must be reminded that this was not always the case. Even more surprising, the single review that does mention her Catholicism does so in an incidental manner, as if the religion that informed every word she wrote and is perhaps the most frequent and prominent watchword of her present reputation was a bit of interesting, but not crucial, information: the Newsweek piece notes, “She is a Catholic in her religion, and at present is trying to read all the works of Henry James, but not making much headway with them, and writes every morning from 9 to 12, finding it hard work.”46 Soon after the novel’s publication, O’Connor wrote to Betty Boyd Love, “The thought is all Catholic, perhaps overbearingly so,”47 but almost none of the original reviewers thought the same. Of course, literature is not simply a subcategory of any creed, nor is Catholicism the only meaningful avenue into O’Connor’s work. But the fact that her Catholicism was simply not an issue to many original reviewers reminds us that what seems like an obvious part of her reputation was not always so. Perhaps the notion of an author’s being southern, female, and Catholic was too improbable a combination for O’Connor’s initial reviewers to consider.

As if not noticing O’Connor’s Catholic themes were not surprising enough, many of the original reviewers assumed that her approach to Motes’s struggle was satirical and sarcastic rather than sincere. Again, some reviewers’ responses to the issues O’Connor raised—issues as thorny as sin, redemption, and the reality of Christ—were based on the assumption that her aim was ironic; an examination of the original reviews reveals an effort to contain or neutralize O’Connor’s Catholic themes and assume that she was mocking Motes rather than presenting him as a person worthy of sympathy. Descriptions of Wise Blood as a novel treating “the difficult subject of religious mania”48 or one about which “we may assume, if we wish, that Christ has gained a wordless victory”49 both miss the mark, for Motes is not subject to any “mania” but the call of Christ who moves like “a wild ragged figure” from “tree to tree in the back of his mind.”50 Similarly, noting that we “may assume” Christ’s victory “if we wish” suggests that making such an assumption is purely a matter of opinion, when O’Connor’s text portrays Christ’s victory as absolute. Motes’s troubles are spiritual, not psychological, and if Christ has not gained a victory in him, the novel is an empty gallery of horrors. Such a response to her work, which suggests O’Connor is satirizing “religious mania” rather than dramatizing the encounter of the human with the divine, hints at what would come later in her career, when some readers of The Violent Bear It Away suggested that Tarwater’s eventual acceptance of his vocation to become a prophet was the result of his being “brainwashed” by his great-uncle. Granted, Isaac Rosenfeld (in the New Republic) did note that “the theme of Wise Blood is Christ the Pursuer, the Ineluctable,” but he also complained that O’Connor fails to fully explore this theme because “Motes is plain crazy, and Miss O’Connor has all along presented him this way.”51 His remarks here resemble those made in another review, where a critic calls Motes “completely insane”52 before his death—although every word of Wise Blood depicts Motes’s movement toward a kind of Catholic sanity, albeit with some shocking reversals and a horrifying cost. “Plain crazy” and “completely insane” are reminiscent of reviews that characterize Wise Blood as being “about the South” and filled with “grotesques” but barely illuminate O’Connor’s thematic concerns and artistic performance. Brad Gooch describes the reviewers’ dilemma by stating that the novel “was obviously satiric, but the object of the satire could be a question mark.”53 Even this misses some of the point, never explaining why he finds Wise Blood satiric nor suggesting any possible targets of O’Connor’s satire. Without identifiable targets, “satirical” becomes, like “grotesque,” more vague than illuminating.

The most complete initial treatment of O’Connor’s thematic concerns and artistic performance appeared not in one of the major outlets, but in Shenandoah, the literary magazine of Washington and Lee University founded in 1950, two years before the publication of Wise Blood. When its editor, Tom Carter, asked Andrew Lytle, O’Connor’s instructor at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, for a review, Lytle declined, acknowledging O’Connor’s talent but feeling that the theological basis for her themes was limiting her art.54 O’Connor had not written the book that Lytle wanted her to write, and his refusal to review Wise Blood reflects how some other reviewers and readers responded to the novel’s urgent and unapologetic religious themes: by dismissing or avoiding them.

Carter next asked Brainard Cheney, the Agrarian novelist, to review the novel. Cheney proved to be a reader O’Connor deserved; his review warrants attention because of how it articulated the style and issues that today strike readers as unquestionably and automatically hers but which many readers in 1952 failed to recognize. His six-page-long review, which seems even longer juxtaposed with Faulkner’s single-paragraph review of The Old Man and the Sea immediately preceding it, is both a recognition of O’Connor’s unique voice and praise for how she surpassed other southern writers who had explored ways in which the nation’s “Patent Electric Blanket”—its sense of security—had short-circuited in the South. Like other reviewers, Cheney compared O’Connor to Caldwell and Faulkner but argued that Caldwell was merely a “dull pornographer” and that Faulkner, “one of the great visionaries of our time,” could write about religion in As I Lay Dying but had still not “been granted the grace of vision.”55 Cheney noted that Caldwell and Faulkner described the hungers of the southern soul but missed the artistic mark by ascribing that hunger to social class (as in Tobacco Road) or naturalistic forces (as in As I Lay Dying):

Wise Blood is not about belly hunger, nor religious nostalgia, but about the persistent craving of the soul. It is not about a man whose religious allegiance is a name for shiftlessness and fatalism that make him degenerate in poverty and bestial before hunger, nor about a family of rustics who sink in naturalistic anonymity when the religious elevation of their burial rite is over. It is about man’s inescapable need of his fearful, if blind, search for salvation. Miss O’Connor has not been confused by the symptoms.56

Like other reviewers, Cheney revealed surprises in the plot but did so in the spirit of appreciation and analysis, noting, for example, that when Motes’s car is pushed down the hill by the policeman, the scene is “the first apparent clue to Haze’s reembodiment of the Christ-myth, this ironic temptation from the mountain-top.”57 Whether or not a reader finds Cheney’s analysis here convincing, he or she can appreciate Cheney’s taking the novel on its own terms and not assuming it to be a series of cruel jokes about its protagonist.

O’Connor wholly appreciated Cheney’s review, writing him that she had been “surprised again and again to learn what a tough character I must be to have produced a work so lacking in what one lady called ‘love.’ The love of God doesn’t count or else I didn’t make it recognizable.”58 O’Connor’s words here reflect the general idea that a reviewer, like Motes himself, can only see what his or her eyes can behold. She also thanked Cheney for considering the novel “so carefully and with so much understanding” and joked about her local reputation among her “connections,” who thought “it would be nicer if I wrote about nice people.”59 Cheney replied, “I am not surprised that your novel did not find popular acceptance” and clarified one source of his enthusiasm: “I’ll have to confess that I was set up for your story: an ex-Protestant, ex-agnostic, who had just found his way back (after 10 or 12 generations) to The Church.”60 Perhaps, in this case, it took one to know one: Cheney and his wife were baptized into the Roman Catholic Church a week before he wrote to O’Connor.

In 1962, prompted by the success of A Good Man Is Hard to Find (1955) and The Violent Bear It Away (1960), Farrar, Straus and Cudahy released a second edition of Wise Blood, again in hardcover and this time featuring a short introductory note by O’Connor. While she was pleased by the second edition, O’Connor was not thrilled at what she called the “repulsive”61 prospect of writing any kind of explanation: “The fewer claims made for a book,” she noted, “the better chance it has to stand on its own feet. ‘Explanations’ are repugnant to me and to send out a book with directions for its enjoyment is terrible.”62 However, O’Connor eventually justified her writing of the introduction on the grounds that doing so would “prevent some of the far-out interpretations,”63 perhaps those found in the original reviews suggesting that she was mocking the very themes to which she was committed. Her concern that an introduction would rob readers of the benefit of a “naïve” reading further reminds us that one of O’Connor’s artistic aims was to shock her readers by the very events (such as Motes’s murder of Solace Layfield, his self-blinding, and his wrapping himself in barbed wire) that so many of the novel’s original reviewers described.

O’Connor’s single-paragraph introductory note is a corrective to what she viewed as misreadings of the novel and a reflection of her by-then established reputation as a Catholic writer. Her description of Wise Blood as “a comic novel about a Christian malgré lui, and as such, very serious” responds to the critical assumption that her aim was satirical or that her goal was to simply report on the South.64 Her statement, “That belief in Christ is to some a matter of life and death has been a stumbling block for some readers who would prefer to think it a matter of no great consequence,” addresses those original reviewers who dismissed Motes as insane and who tried to force the square peg of Wise Blood into the round hole of modern secularist values. The final sentences of O’Connor’s note are an admonition to those reviewers and future readers who would use her work—or the work of any novelist—to explain away spiritual matters (such as one’s free will contesting with God’s) in an effort to make them less troubling: “Freedom cannot be conceived simply. It is a mystery and one which a novel, even a comic novel, can only be asked to deepen.” What she saw as the tendency of contemporary thinkers to reduce the mysteries she explored eventually became one of her artistic subjects, epitomized by Hulga in “Good Country People” and Rayber in The Violent Bear It Away, who is warned by his uncle, “Yours not to grind the Lord into your head and spit out a number!”65 To O’Connor, art could only “deepen” spiritual questions, not solve them.

However, reviews of the second edition of Wise Blood suggest that O’Connor’s worries about “far-out interpretations” were not entirely justified since fewer critics in 1962 attempted to grind O’Connor into their own heads and spit out a number for their readers than did their counterparts a decade earlier. The text of Wise Blood was exactly the same, but the critical community was not: A Good Man Is Hard to Find (1955) and The Violent Bear It Away (1960) had readjusted the critical focus so that the very issues puzzling Wise Blood’s initial reviewers now appeared clearer. O’Connor’s talent now also seemed obvious.

Before many reviewers even discussed the novels’ merits, they noted the unusual practice of releasing it in a second, hardback edition, a move that reflected Farrar, Straus and Cudahy’s investment in her as source of financial and cultural returns. For example, the Chicago Sun-Times noted, “Miss O’Connor’s novel, reissued now not in paperback but in hard covers and at a hard cover price, was not a best-seller when it appeared 10 years ago, but it was and is a good novel and should be kept in print.”66 Other reviewers noted that the “happily reissued”67 edition of Wise Blood was “a literary event,”68 that the reissue “confirmed the arrival on the American literary scene of a novelist of importance,”69 and that “Anyone who missed Wise Blood when first published 10 years ago should not fail to read it in this new edition.”70 Such a reissue was “an unusual event in the publishing world—and one of not little significance.”71 The critical community’s endorsement of the reissue reflected a new critical belief, articulated in the Oakland Tribune, that Wise Blood “unquestioningly repays a second reading.”72 “Unquestioningly” now, but not so ten years earlier.

One review of the second printing demonstrates a shift in critical attitudes toward O’Connor and how previous rules of notice governing what was worth mentioning about O’Connor had changed. Writing in Christian Century, Dean Peerman began his review, “An ardent Roman Catholic who is sometimes mistaken for a diabolist or a demoniac, young Georgia novelist Flannery O’Connor is a master of Gothic grotesquerie, but at bottom her stories are far too complex, far too concerned with fundamentals, ever to be mere typifications of that genre.”73 O’Connor’s age, region, and use of the grotesque are still offered as worthy of notice, but here they have become secondary to O’Connor’s “ardent” Catholicism. Noting that O’Connor was a Catholic reflected how her reviewers had learned, over the course of the intervening decade, to read Wise Blood in a different light. Time and the publication of two additional titles had illuminated Wise Blood in ways that the book by itself seemingly could not.

Several reviews from British periodicals, written four years after O’Connor’s death and after the reissue of Wise Blood in the United Kingdom, echo their American counterparts. The Times Literary Supplement called the reissue “an event warmly to be welcomed” and declared that O’Connor’s Catholicism, “never intrusive in the stories, for once is dominant.”74 What was originally only noticed once, in passing, had now become “dominant.” And while the Manchester Guardian Weekly noted that O’Connor’s reputation in the United Kingdom was “subterranean, a bit special, limited to those who can appreciate the peculiar flavor of religious violence that pervades her work,” the reviewer did note O’Connor’s “passion for ravaging a few souls.”75 The South also rose again here, although this time in qualified terms: “It is a work of strange beauty, totally original, set in a South as far removed from Tennessee Williams and his lachrymose cripples as it is possible to be. A tougher writer, O’Connor invested her human relics with a ferocious dignity.”76 Geography had become less a way to pigeonhole O’Connor than a way to help account for the “strange beauty” of her work, a beauty with which critics were still coming to terms.

Reviews are not, of course, the only means by which an author’s reputation is created and established. The visual artists responsible for illuminating the themes of an author’s work also affect one’s reputation, if, again, by “reputation” we mean the ways that an author’s artistic performance and thematic concerns are apprehended by various readers. People do judge books by their covers, and covers are a means by which a writer’s reputation is built over time, since the artwork on them can reflect contemporary understandings of a writer’s style and themes. In his examination of the dust jackets of William Styron’s The Confessions of Nat Turner, James L. W. West III argues convincingly that the design of the novel’s dust jacket and typeface influenced readers and critics—and while he admits that “It is impossible to get at such things empirically,”77 his essay as a whole serves as a convincing case for the effects of what Gérard Genette calls “paratexts” on readers and critics. Genette defines “paratexts” as the accessories that accompany a text, such as the author’s name, the work’s title, and introductory matter that precedes it. A book’s cover and artwork are also paratexts, ones that advise a reader on how to approach the text and that attempt to “ensure for the text a destiny consistent with the author’s purpose.”78

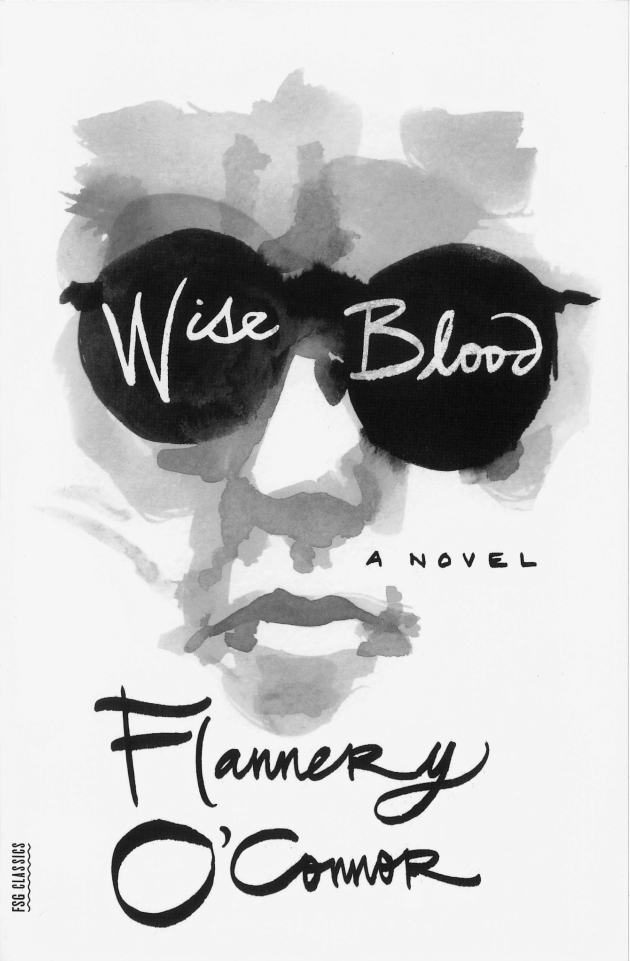

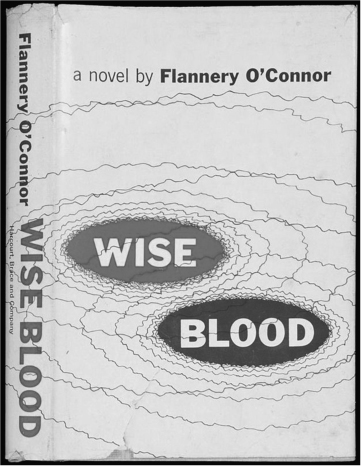

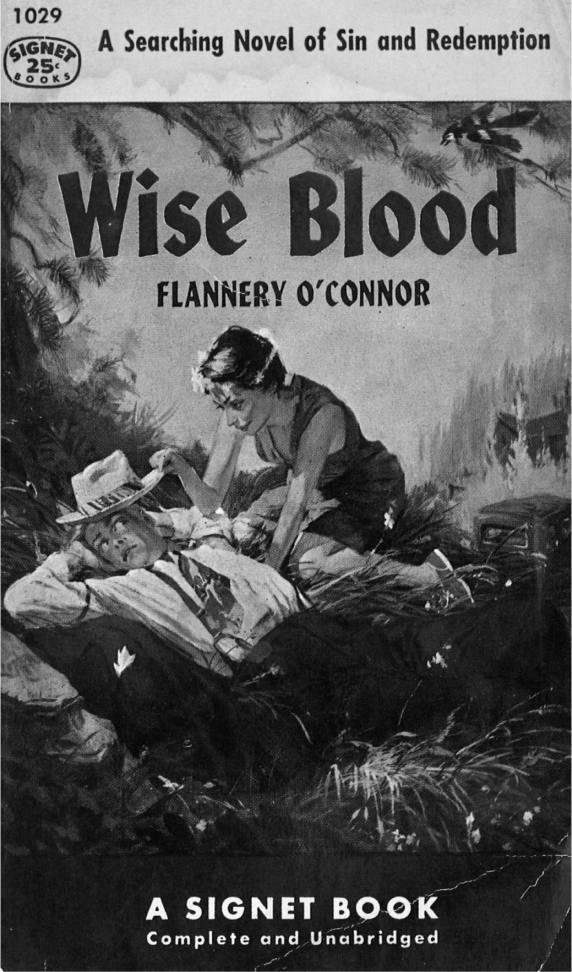

The history of Wise Blood’s various covers reveals a number of attempts to suggest O’Connor’s thematic concerns, some more consistent with these than others. The history of the covers parallels that of the novel’s critical reception: like the reviews, the covers range from vague to misleading to eventually representative of O’Connor’s thematic concerns. The early covers suggest that those charged with initially packaging the novel felt some of the same unease experienced by the original reviewers. The first edition of Wise Blood in 1952 features the title surrounded by warped concentric circles (fig. 1); all a reader might infer about the novel is that it is strange or, perhaps, concerns hypnosis. O’Connor regarded the design as “very pretty” but also noted, “The jacket is lousy with me blown up on the back of it, looking like a refugee from deep thought.”79 The British edition of Wise Blood, published by Neville Spearman in 1955, featured a cover designed by Guy Nicholls representing Hazel Motes wearing his enormous preacher’s hat, looking heavenward and seemingly praying for his car. The bright pink hues of the background offer no indication whatsoever of the novel’s violence or dark comedy: the cover would, according to O’Connor, “stop the blindest Englishman in the thickest fog.”80 Such visual misrepresentation continued when the paperback was issued by Signet in 1953: its cover featured an illustration of Motes attempting to nap in the forest while Sabbath—looking older than her fifteen years of age—removes what certainly does not resemble the preacher’s hat that reminds Motes of his struggle (fig. 2). The illustration looks more like a scene from a traveling salesman joke than one from O’Connor’s novel. The comments on the back also obfuscate the book’s content, as they describe Wise Blood as “A richly humorous story of strangers in a lazy Southern town who become enmeshed in a conflicting web of earthly and spiritual desires” and “a compassionate, ironic, and warmly human novel of frustrated hopes and loves.” Such description, better suited to a saccharine romance, misrepresented O’Connor’s novel because more accurate phrases would never have sold it. Ace Books used a similarly misleading cover in 1960 (fig. 3), which O’Connor despised, noting, “Sabbath is thereon turned into Marilyn Monroe in underclothes.”81 Such covers were blatant attempts to sell O’Connor’s work in a way that eliminated any hint of its theological content: the “sin” mentioned over each title is not implied to be blasphemy, but one more immediately recognizable and salacious. One can imagine how disappointed the readers who purchased Wise Blood on the strength of these covers must have been.

Figure 1. Cover of Wise Blood, first edition, 1952.

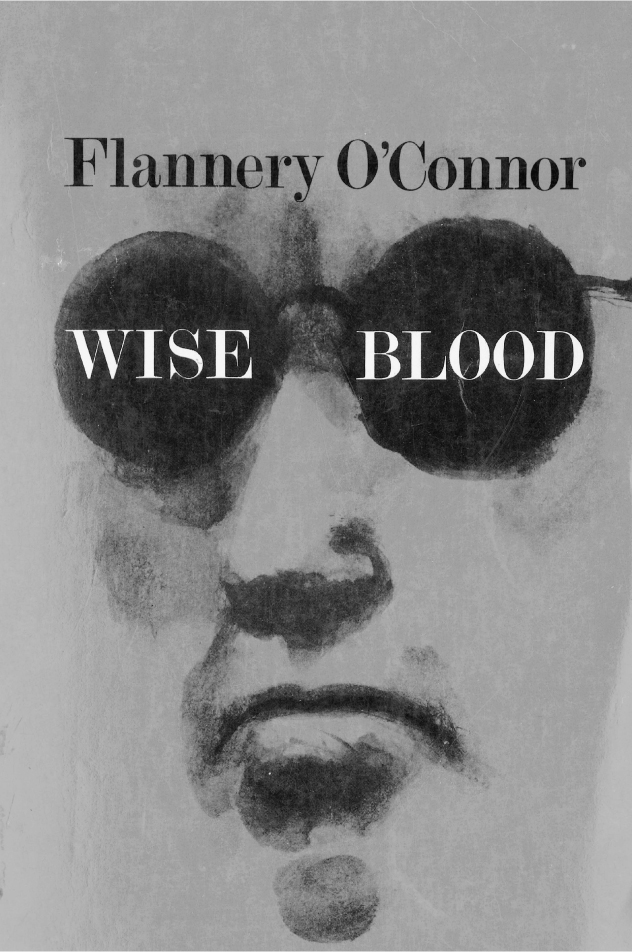

The 1962 reissue of the novel featured cover art by Milton Glaser (fig. 4) and better reflected the novel: anyone noticing this edition, with its shadowy portrait of either Asa Hawks or Motes himself, would have a much better idea of the novel’s grim content than could be discerned from earlier editions. Glaser later famously defined the logo as “the point of entry to the brand”; such a definition applies to his cover of Wise Blood, which serves as a point of entry to the novel’s theme of spiritual blindness. Two years later saw Signet’s publication of Three by Flannery O’Connor, a collection that included Wise Blood; its cover, featuring a cartoon of Motes in his Essex with Sabbath’s legs hanging over the side and a “CHURCH WITHOUT CHRIST” sign cleverly replacing the expected “JUST MARRIED” (fig. 5). That Motes never hangs such a sign on his rat-colored Essex is beside the point of the illustrator’s attempt to convey a sense of wackiness. A later Signet reprint (fig. 6) emphasized the rural setting of O’Connor’s works and implied, with a font reminiscent of saloon signs or roadside diners, a cheerfulness and “down-hominess” that her work totally lacks. The road on this cover seems not to be the one promising endless persecution that Tarwater knows he must walk in The Violent Bear It Away.

Figure 2. Cover of Wise Blood, Signet, 1953.

Figure 3. Cover of Wise Blood, Ace, 1960.

Figure 4. Cover of Wise Blood, Glaser illustration, 1962.

Figure 5. Cover of Three by Flannery O’Connor, Signet, 1964.

Figure 6. Cover of Three by Flannery O’Connor, Signet, 1983.

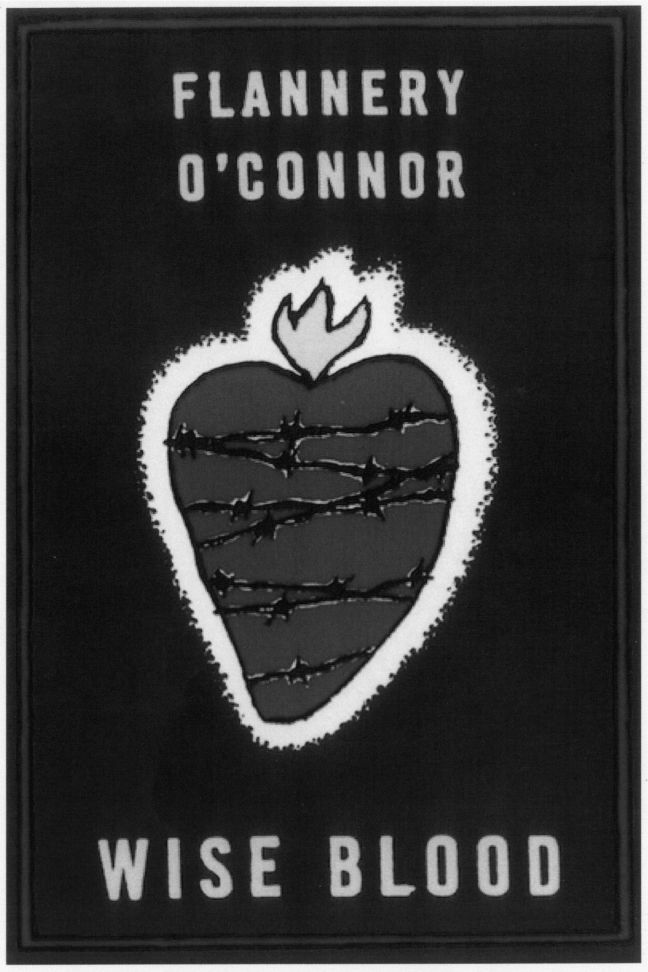

In 1990 Farrar, Straus and Giroux reissued paperback editions of several of O’Connor’s works and hired Canadian illustrator Roxanna Bikadoroff to illustrate their covers. Her illustration for Wise Blood stands as ideally representative of O’Connor’s thematic concerns and artistic performance and most indicative of O’Connor’s reputation as an author of shocking and spiritual fiction (fig. 7). When asked about her design, Bikadoroff explained how she arrived at her choice of image and why she felt it to be appropriate for the novel:

I wanted the covers to have simple, iconic images. Symbolic imagery is very much like an arrow or key that allows instant entry to the unconscious or collective unconscious; it is a different language than writing, but together they work on both sides of the brain at once and bring a union/understanding. O’Connor uses so much symbolism, too, it was only appropriate. So I chose symbols that were universal, powerful. They had to have a twist which made them particular to the stories, though, and convey the essence of the work or the main character. The heart with barbed wire is pretty obvious for Wise Blood. It echoes the crown of thorns and the sacred heart of Jesus, but also the barbed wire Motes wraps around his chest in his religious self-flagellation/penance.82

Bikadoroff’s cover, coupled with a blurb on the back by Brad Leithauser declaring, “No other major American writer of our century has constructed a fictional world so energetically and forthrightly charged by religious investigation,”83 demonstrates the degree to which the understanding of Wise Blood in particular and O’Connor in general had changed over time. Her spiritual concerns, now blazoned on the cover of her first novel, had become more worthy of notice than the violence of her plots. Further indication of this change appears in a transcript of one of the 2008 Open Yale courses on American literature. The professor, Amy Hungerford, begins by directing her students to look at Bikadoroff’s cover and then asking, “What does it look like to you?” When a student responds, “Is it the Sacred Heart?” Hungerford responds:

It’s the Sacred Heart, yes. It’s the Sacred Heart of Jesus. In Catholic iconography of a certain kind, the figure of Christ is shown usually parting His clothes and His flesh and showing you His Sacred Heart, which is usually crowned with flame and often encircled with thorns. So it’s an image of Christ the suffering godhead: the very human, fleshly person who will part His own flesh in order to connect with, in order to redeem, the believer. So right in the packaging of this novel that we have today—this cover has changed over time—nevertheless, even today, that very Catholic iconography is right on the front of the cover. And when you see Wise Blood, that title, right below the Sacred Heart, you can’t help but think of: well, this blood is somehow the blood of Christ. That’s the kind of blood we’re talking about. It’s already entered a sort of metaphorical register, religious register, in the way this book is packaged.84

Figure 7. Cover of Wise Blood, Bikadoroff illustration, 1990.

O’Connor’s reputation as a Catholic writer has taken root so firmly that it can be mentioned at the start of a lecture. The “register” Hungerford mentions is one that has been reshaped by criticism, publishers, and graphic designers since 1952.

The Farrar, Straus and Giroux paperback edition (2007) features a golden cross against a black background with the novel’s title written in stately capitals (fig. 8), Leithauser’s blurb at the bottom, and the FS&G logo on the side as an indicator of the book’s literary pedigree; the 2008 Faber & Faber cover features a cross-topped church. O’Connor’s reputation as a Catholic novelist is now taken for granted, but publishers, like reviewers, took their time before they allowed themselves to acknowledge—rather than hide or avoid—this fact. And, in a final example of how cover art can reflect different approaches to a work at different points in time, June Glasson’s illustration for the 2015 FSG Classics edition recalls Milton Glaser’s 1962 portrait of Motes and emphasizes the book’s religious themes less than the previous edition did (fig. 9).

In an angry letter to John Selby, her original editor at Rinehart who held an option on Wise Blood and who, according to O’Connor, wanted to “train it into a conventional novel,” O’Connor declared, “I think that the quality of the novel I write will derive precisely from the peculiarity or aloneness, if you will, of the experience I write from. . . . The finished book will be just as odd if not odder than the nine chapters you have now. The question is: is Rinehart interested in publishing this kind of novel?”85 O’Connor knew what it took many readers ten years (and two other works by O’Connor) to learn: “this kind of novel” could simply not be read as a conventional one in which issues are neatly resolved, where geography is artistic destiny, or where violence was more sensational than suggestive of a spiritual agon. But one must not accuse these reviewers of benighted judgment: like Motes, they needed to be jolted out of their figurative blindness, a jolt supplied by O’Connor herself with the publication of A Good Man Is Hard to Find in 1955 and The Violent Bear It Away in 1960.

Figure 8. Cover of Wise Blood, Bikadoroff illustration, 1990.