Chapter 3

Chapter 3

Chapter 3

Chapter 3

The years between the publication of The Violent Bear It Away (1960) and Mystery and Manners (1969) saw the deterioration of O’Connor’s health and her death in 1964. But her death did not slow her works’ rate of publication nor quiet the readers and reviewers who were working, however unknowingly and certainly not in concert, to construct a reputation that would finally earn O’Connor the first posthumously awarded National Book Award for fiction, an early place in the Library of America, and a collection of associations and assumptions about her fiction that accompanies O’Connor’s name to the present day.

After The Violent Bear It Away, O’Connor continued publishing short stories in quality fiction magazines (such as New World Writing and Sewanee Review) as well as in one with greater, national readership: the opening chapter of her third, unfinished novel, Why Do the Heathen Rage?, appeared in the July 1963 Esquire, which, at the time, had its own impressive reputation for publishing fiction. “Everything That Rises Must Converge” won the 1962 O. Henry Award; “Revelation” won it in 1964; her work was well received in France thanks to the efforts of Maurice Coindreau (who translated Wise Blood in 1959 and The Violent Bear It Away in 1965) and the Éditions Gallimard versions of her work; and O’Connor received honorary degrees from Smith College and from Saint Mary’s, the women’s college of Notre Dame. Her name on a book’s cover—as opposed to a lurid or intriguing illustration—was now given greater prominence than the title: in 1963 the New American Library released A Good Man Is Hard to Find and the two novels in a single volume entitled Three by Flannery O’Connor.

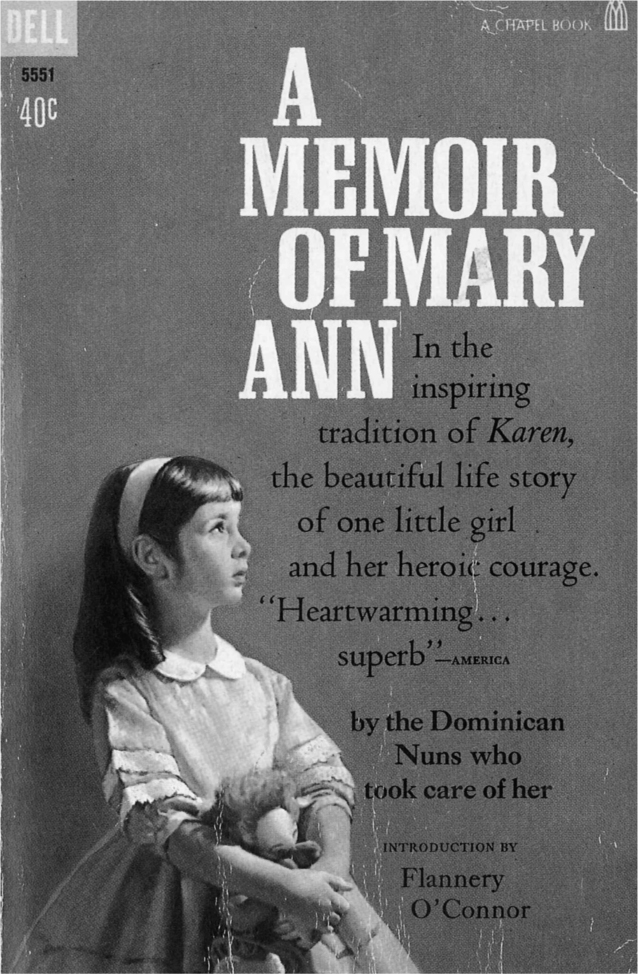

In 1961 O’Connor composed an introduction to A Memoir of Mary Ann, written by the Dominican nuns who staffed the Our Lady of Perpetual Help Free Cancer Home in Atlanta; although this introduction is read and discussed more by O’Connor’s ardent admirers than by her casual fans, its composition and reception offer a glimpse into her reputation at this time. The memoir’s titular figure arrived at the home when she was three and remained there until her death, at the age of twelve, from a cancerous tumor that dominated her face. The nuns who cared for Mary Ann found her an inspiring example of God’s grace and asked O’Connor to compose the memoir herself, but O’Connor demurred, instead agreeing to edit the work and write an introduction, which today reminds readers of her unflinching style (its opening sentence, for example, states, “Stories of pious children tend to be false”1) and favorite themes, such as the idea that all human life is like Mary Ann’s, filled with mystery and preparation for death. In terms of O’Connor’s reputation, the introduction suggests, even by virtue of O’Connor’s having been asked to write the memoir herself, how her literary stock had risen. Some of the memoir’s reviewers cited the introduction and described O’Connor as a “brilliant Southern novelist”2 and “a professional writer by stature and a Catholic.”3 O’Connor was also regarded as the perfect antidote to the potential mawkishness of the subject: writing in the Boston Pilot, Edward F. Callahan admitted that the subject matter “gives the reader the fear that the book will be an orgy of saccharine equal to the mid-Victorian tearjerkers,” putting one in the mind of Little Nell, but then stated, “In the editing of this memoir, Miss O’Connor has obviously used a broad, blue pencil with the end result being a book of a much greater power than its subject or its literary predecessors might suggest.”4 This reviewer’s emphasis on O’Connor’s lack of sentimentality cropped up in a review for the Savannah Morning News Magazine that described the Dominican nuns approaching O’Connor and asking her to write the book herself: “We can imagine Miss O’Connor’s dilemma,” the reviewer states, “for all who know her gothic style would know that this was not exactly her medium.”5 O’Connor’s thematic concerns and artistic performance were so well recognized that reviewers could imagine, with confidence, how she would respond to a text. Such is one effect of an established reputation and an effect found in much of the subsequent critical reaction to Everything That Rises Must Converge. O’Connor’s name on the cover of both the hardcover and paperback reprints (fig. 10) thus lent the nuns a literary air without which the initial release may have been ignored or, in the case of the paperback, dismissed as being as sentimental as its cover art.

On August 3, 1964, three years after the publication of A Memoir of Mary Ann, O’Connor died of kidney failure brought on by the lupus that she had battled for over ten years. The news of O’Connor’s death as reported by the AP wire and reprinted in hundreds of newspapers offered a bare-bones summary of her career: “MILLEDGEVILLE, GA (AP)—Flannery O’Connor, short-story writer and novelist who suffered from a chronic crippling illness, died Monday at the age of 39. In 1959, Miss O’Connor was one of 11 American writers to receive a Ford Foundation grant.”6 The upi obituary added, “Many of her characters, Southerners, were freak prophets, men of limited background who felt a supernatural call to preach.”7 (The characterization of figures such as Tarwater here suggests that the author of this obituary was a member of O’Connor’s ironic audience.) The New York Times obituary, “Flannery O’Connor Dead at 39; Novelist and Short-Story Writer; Used Religion and the South as Themes in Her Work; Won O. Henry Awards,” erased any tension between the ironic and genuine authorial audiences or between those who found her unreadable and those who found her prophetic: “In Miss O’Connor’s writing were qualities that attract and annoy many critics: she was steeped in Southern tradition, she had an individual view of her Christian faith and her fiction was often peopled by introspective children. But while other writers received critical scorn for turning these themes into clichés, Miss O’Connor’s two novels and few dozen stories were highly praised.”8 The author elaborated on the UPI writer’s impression of O’Connor’s characters, describing them as “Protestant Fundamentalists and fanatics.”9 Again, as with the case of Mason Tarwater, we see a reviewer tip his or her hand through the use of the word “fanatic.” And Time magazine, ever ironic toward O’Connor and her fiction, described her in its “Milestones” section as an “authoress of the Deep South, an impassioned Roman Catholic from the Georgia backwoods who . . . explored the South’s religious curiosities, finding among them . . . an appalling collection of lunatic prophets and murderous fanatics.”10 O’Connor and members of her genuine authorial audience would certainly object to this description of the prophets she had “found” while writing her fiction: even the terrifying hoodlums in “A Circle in the Fire” who, in their burning of the woods, prophesy to Mrs. Cope are not lunatics.

Figure 10. Cover of A Memoir of Mary Ann, 1961.

After her death, the student editors of Esprit, the University of Scranton’s literary magazine, devoted the entire Winter 1964 issue to O’Connor. This may not, at first, seem like a major tribute. However, this issue of Esprit is invaluable to anyone examining the history of O’Connor’s reputation because its faculty advisor, the Rev. John J. Quinn, S.J., solicited opinions about and reminiscences of O’Connor from dozens of critics, scholars, and authors, many of them established names. O’Connor had a friendly relationship with Quinn and Esprit: she had judged the magazine’s first short-story contest and published her essay “The Regional Writer” in its pages. Quinn maintained a correspondence with O’Connor and also visited her mother after O’Connor’s death, which he noted in the issue’s foreword, thanking “Mrs. Edward F. O’Connor and her charming family for the gracious hospitality extended Esprit on the occasion of its unforgettable week-end (Oct. 30– Nov. 2, 1964) visit to Andalusia.”11 One of the student editors, John F. Judge, described Quinn as “the drive and inspiration” for O’Connor’s presence in the university’s courses and revealed, “Although he knew it would be impossible for any northern university to be even considered, Quinn actually made an effort to establish the University of Scranton as the Flannery O’Connor Library.”12 The relationship between the magazine and O’Connor was thus a substantial one; that the University of Scranton is a Jesuit institution certainly did not prevent O’Connor’s ideas and art from receiving a fair hearing. The eighty-eight-page issue invaluably traces the history of O’Connor’s reputation.

The tribute begins with Quinn’s preface proclaiming the magazine’s mission to extol O’Connor’s artistic and personal virtues, “Lest the Prophet be without honor in her own terrestrial country.”13 This declaration is followed by “The Achievement of Flannery O’Connor,” in which University of Scranton professor John J. Clarke argues that O’Connor’s importance lay in her readjusting general notions of Catholic literature. Noting that “we have had too narrow a notion of what Catholic art might embrace,” Clarke states that O’Connor “has expanded our view, even if it should be the verdict of time that the sensational situations of her stories transgress artistic limits” and that, regardless of how one reacts to the content of her work, “In the persisting paucity in America of Catholics who are good fiction writers, her absence will be sorely felt.”14 The issue also contains three extended critical analyses of O’Connor’s work as well as a comparison of her work with Dostoevsky’s, line drawings inspired by scenes and characters from her fiction, six poetic responses to O’Connor (among them “A Celt Sleeps,” an excruciating imitation of Robert Burns), and two pieces of short fiction. The issue, for the most part, attempts to serve as an instruction manual for O’Connor’s work, with a number of professors offering declarative statements such as, “The theme of Flannery O’Connor’s fiction is free will,”15 or “The significance of Flannery O’Connor is to be found . . . in her insistence upon the primacy of ideas.”16 One aim of the issue was to help readers appreciate what the editors, with their fingers on the pulse of O’Connor’s reputation, had already discovered.

The heart of this issue of Esprit, however, is “Flannery O’Connor—A Tribute,” a collection of reminiscences and testimonials that Quinn solicited in the days following her death. Of the forty-nine pieces of commentary gathered here, nine were previously published in such periodicals as the New Yorker and the New York Times. All are arranged alphabetically, save one: a reminiscence of O’Connor made, via telephone, by Katherine Anne Porter, which appears last in the collection, interspersed with photographs of Andalusia. To emphasize the value of Porter’s words, the editors gave them their own title (“Gracious Greatness”) and noted, “Esprit expresses its special gratitude to Miss Porter for telephoning—from her sick bed in her Washington home—the following reminiscence of Miss O’Connor.”17 Other notable contributors of original commentary included Elizabeth Bishop, Kay Boyle, Cleanth Brooks, Caroline Gordon, Elizabeth Hardwick, John Hawkes, Granville Hicks, Frank Kermode, Robert Lowell, Andrew Lytle, Robie Macauley, Thomas Merton, Allen Tate, Robert Penn Warren, and Eudora Welty. Some of the authors gathered here suggest the importance of O’Connor’s work by their presence as well as their actual words, as in the case of Saul Bellow, whose contribution, in full, reads, “I was distressed to hear of Miss O’Connor’s death. I admire her books greatly and had the same feeling for the person who wrote them. I wish I were able to say more, but it isn’t possible just now.”18 J. F. Powers, another Catholic whose faith informed his fiction, supplied a similarly brief yet meaningful set of remarks: “Flannery O’Connor was an artist blessed (and cursed) with more than talent. In a dark and silly time, she had the great gift—the power and the burden—of striking fire and light. She was one of those rare ones, among writers, whose life’s work was not in vain.”19

An examination of “Flannery O’Connor—A Tribute” reveals the trends in O’Connor’s reputation later surfacing in reviews of Everything That Rises Must Converge. The first of these trends was the interest in treating O’Connor’s reputation as a subject as worthy of comment as her work itself and the desire to correct presumed prevailing notions of her place in American letters. Those who rose to this challenge of setting the record (as they saw it) straight were the professors. Charles Brady, of Canisius College, noted, “One of the biggest difficulties in assessing contemporary literary reputations is the tendency to praise an emerging writer for the wrong reasons”20 and that praising O’Connor as another McCullers or Capote was off the mark (and, in fact, far from actual praise). Robert Drake, of the University of Texas, similarly complained that labels such as “Southern Gothic novelist” or “a Roman Catholic Erskine Caldwell”21 were inadequate and inexact. James F. Farnham, at Western Reserve University, wrote, “Miss O’Connor is an artist, and Catholicism is one of her ‘circumstances,’”22 just like her southern address. Sr. Mariella Gable, of the College of St. Benedict, complained that O’Connor was “carelessly lumped with other outstanding Southern writers as another purveyor of the gratuitously grotesque.”23 Louis D. Rubin, then professor at Hollins College, insisted that O’Connor “did not write in the shadow of Faulkner, or of anyone else.”24 Nathan A. Scott Jr., of the University of Chicago, called “Southern Gothic” a “foolish rubric”25 to use when thinking about O’Connor. And Robert Penn Warren, then at Yale, noted, “She is sometimes spoken of as a member of the ‘Southern school’ (whatever that is), but she is clearly and authoritatively herself.”26

Other authors included in Esprit argued that O’Connor’s reputation initially suffered because her first readers were not ready for a voice as original as hers. For example, Elizabeth Hardwick stated that O’Connor was “indeed, a Catholic writer, also a Southern writer; but neither of these traditions prepares us for the oddity and beauty of her lonely fiction.”27 Caroline Gordon accurately summarized much of O’Connor’s early reception when she noted, “We do not naturally like anything which is unfamiliar. No wonder Miss O’Connor’s writings have baffled the reviewers—so much so that they have reached for any cliché they could lay hold of in order to have some way of apprehending this original and disturbing work.”28 The description “Southern Gothic Catholic female novelist” seemed to carry less weight than it did the previous decade and was now regarded as misleading.

One soon-to-be cliché that was just gaining ground in O’Connor’s reputation was that her illness was somehow responsible for her art—an idea that, in the wake of her death, proved irresistible to many readers and would gain traction a few months later in the reviews of Everything That Rises Must Converge. In what might be the most presumptuous of the appreciations gathered in Esprit, Brother Antonius (the poet and critic William Everson) noted, “Doubtless the facts of her personal life enabled her to confront the problem of violence in the search for understanding.” After acknowledging about these facts that “I do not know what they were,” Everson explained, “there was in her work an affinity to the humanity of her characters that could only have come from deep suffering.”29 As Caroline Gordon noted, many readers would reach for any cliché—here, the one of the Suffering Artist—to make sense of O’Connor’s work. Elizabeth Hardwick mentioned O’Connor’s “secluded life,”30 an untrue characterization that, we will see, gained ground in the coming years but does not illuminate O’Connor’s work; others mention what one author calls a “beautiful soul in an afflicted body,”31 which similarly illuminates very little of O’Connor’s actual character in anything but saccharine terms. Robie Macauley, then editor of the Kenyon Review and an acquaintance of O’Connor, stated, “Much of her life must have been a torment. She wrote hard and re-wrote even more painfully; her terrible affliction was with her for many years. It is no wonder that her great subject was the anti-Christ—the fierce and bestial side of the human mind. She treated it with a confused and emotional hatred.”32 That O’Connor experienced great physical pain is not debatable; that “much of her life must have been a torment” certainly is. Macauley’s desire to account for O’Connor’s art as the result of her “terrible affliction” rather than her imagination or intelligence is the kind of thinking that Caroline Gordon protested and which, a year later, would surface in reviews of Everything That Rises Must Converge.

Other contributors to “Flannery O’Connor—A Tribute” offered their opinions of O’Connor’s character as a means of accounting for the moral courage they assumed she required to tackle her chosen subjects. Cleanth Brooks’s comment, “I find it hard to separate the person from the artist” since “the character of both was an invincible integrity,”33 reflects the ways in which many other contributors praised O’Connor’s “enduring courage,”34 “toughness,”35 and “bravery.”36 Robert Lowell described O’Connor as “a brave one, who never relaxed or wrote anything that didn’t cost her everything.”37 Laurence Perrine, a professor at Southern Methodist University whose literature textbooks became standard-issue in thousands of English courses, related an anecdote in which he wrote to O’Connor, asking her why, in “Greenleaf,” she had named Mrs. May as she did. His description of O’Connor’s reply emphasizes the image of the playfully teasing O’Connor found throughout the pages of Esprit:

Miss O’Connor’s reply, dated June 6, 1964, was written from a hospital in Atlanta, Georgia, a bare two months before her death. She answered, in a kindly letter that must have given her trouble to write at all, “As for Mrs. May, I must have named her that because I knew some English teacher would write and ask me why. I think you folks sometimes strain the soup too thin.” I still feel a pleasant ache where my wrist was thus lightly slapped by so gallant a lady.38

The general effect of such testimonials is the continued fostering of O’Connor as a stoic figure and an intertwining of the artist’s personality and subject matter. In the hopes of illuminating O’Connor’s strength, Katherine Anne Porter engaged in a kind of physiognomic appreciation that would resurface in reviews of Everything That Rises Must Converge: in her description of O’Connor’s self-portrait, Porter states that “the whole pose fiercely intent gives an uncompromising glimpse of her character.”39 The assumption that underlies so much of “Flannery O’Connor—A Tribute” is that O’Connor faced the truth and the truth had made her tough.

There are, however, some voices included in the tribute that balance the overwhelming portrayal of O’Connor as similar in temperament to old Mason Tarwater. The novelist John Hawkes emphasized that O’Connor closed all her letters with “Cheers,” a word that, he argued, “represents the attitude she took towards life” and suggested the “economy, energy, pleasure and grace” she infused into her fiction. Mindful of O’Connor’s reputation as a firebrand, Hawkes noted, “So now it seems important to stress the sprightly warmth and wry, engaging, uninhibited humanity of a writer commonly described as one of America’s coldest and most shocking comic writers.”40 In a short offering, critic and professor Francis L. Kunkel similarly stressed the importance of O’Connor’s “often overlooked” humor, noting that she resembled Waugh and Powers but demonstrated “the ability to treat religious matters with humor.”41 Not all readers viewed the ability to explore deep spiritual matters and make a reader laugh as mutually exclusive. Mason Tarwater was humorless, but O’Connor was not.

This issue of Esprit is also important to O’Connor’s reputation because it reflects the growing connection between the peacock and O’Connor’s image. The peacock, as O’Connor knew, has had a long association in Catholic art with immortality based on the legend that, after death, the bird’s flesh does not decay. In “Living with a Peacock,” a lighthearted essay appearing in the September 1961 issue of Holiday magazine and later reprinted in Mystery and Manners as “The King of the Birds,” O’Connor described her interest in collecting peafowl. Esprit’s cover reinforced the association between O’Connor and the peacock (fig. 11), as does the issue’s final selection, a poem titled “The Peacock and the Phoenix,” which depicts a maudlin peacock lamenting, “Fair Authoress, only thirty-nine, / You died before your finest line.”42 The peacock is now as much a part of O’Connor’s reputation as butterflies are of Nabokov’s or the French poodle, Charlie, is of Steinbeck’s—perhaps even more so, since one can hardly find a modern work by or about O’Connor that does not, on its cover, depict her favorite fowl (figs. 12–13). Combining elements of her life on a farm, her religious themes, personal eccentricities, and outsider status, the peacock has proved the perfect icon for O’Connor’s readers, critics, and biographers, a form of reputation-shorthand that has only grown more ubiquitous over time—a phenomenon the editors of Esprit could not have predicted but which they certainly helped accelerate.

In April 1965, nine months after O’Connor’s death, Robert Giroux published Everything That Rises Must Converge, O’Connor’s second collection containing nine stories, all of which had been previously published individually except for “Judgment Day,” a reworking of her first story, “The Geranium.” Many of the original reviewers understandably wrote of O’Connor’s recent death, making their reviews sound like eulogies as much as critical assessments. In the New York Times, for example, Charles Poore noted that O’Connor “died at the height of her promise,”43 while a reviewer for the Cleveland Plain Dealer lamented the death of a writer “so young and with so much more to tell a world which needed to hear it.”44 A writer for the Arizona Republic reasoned that “since most of what she wrote was an improvement over what had gone before, there is no knowing how far she might have progressed had she been allowed more than 39 years on this earth.”45 Newsweek described her death as “a measureless loss,”46 and, in what may be the most flattering (or hyperbolic) comparison thus far in the story of O’Connor’s reputation, the novelist and editor R. V. Cassill stated, “Miss O’Connor did not die quite as young as Keats, but she will keep, in our minds, a place reminiscent of his.”47 In the twelve years since the publication of Wise Blood, reviewers felt comfortable in speaking of O’Connor’s work as a “permanent part of American literature”48 or agreeing with Alan Pryce-Jones’s assessment—now found as a blurb on the back covers of paperback editions of O’Connor’s work—that “There is very little in contemporary fiction which touches the level of Flannery O’Connor at her best.”49 Indeed, the assertion that “Flannery O’Connor’s is a voice that time will never still”50 is representative of her postmortem reputation. Earlier in her career, O’Connor’s reputation as a southern and, especially, a Catholic writer was gradually developed to the point where these terms gained critical currency; now, after her death, she was being eulogized as a southern and Catholic writer who escaped “either catalogue through her own genius.”51 The old watchwords that had seemed so perfect and so strong were beginning to show their seams.

Figure 11. Cover of Esprit, Winter 1964.

Figure 12. Cover of Gooch biography, 2009.

Figure 13. Cover of Rogers biography, 2012.

However, there was not a seismic shift in the way O’Connor was perceived by her critics: a number of issues found in the reviews of O’Connor’s previous works surfaced, even more strongly, in those of Everything That Rises Must Converge. The South as a setting for universal themes was again noted by many reviewers: the National Observer stated that O’Connor’s setting and characters “take on the dimensions of every time, every place, and every man,”52 while the Wall Street Journal called O’Connor “truly a writer for all seasons and times.”53 Even the New Yorker, which had panned A Good Man Is Hard to Find a decade earlier, begrudged in a mixed review that “her province is Christendom rather than the South.”54 Other reviewers argued much the same,55 but, in a moment that recalls the action of those writers for Esprit who began commenting on O’Connor’s reputation as much as her work, a reviewer for Georgetowner magazine remarked, “It is unfortunate that Flannery O’Connor has been tagged as a Southern writer and/or a Catholic writer, for what she has to say has universal significance.”56 She was still routinely compared to Faulkner, Welty, and McCullers, but also now to Dante, whom one reviewer named as O’Connor’s “classical mentor.”57 In Jubilee, fellow-Catholic and best-selling author Thomas Merton topped even this superlative when he compared her to Sophocles in a quotation that became the blurb featured on the book’s dust jacket.58 Her work was again recommended (as in Booklist) for “the discriminating reader,”59 and her gender was still worthy of notice: “Though feminine in spirit,” a reviewer in Atlanta remarked, “Miss O’Connor writes with a firm masculine hand. No story would identify her sex.”60 Finally, one can still find the theme of local-girl-makes-good: an article in the Milledgeville Union-Recorder spoke proudly of the fact that the collection was introduced by “Harvard professor”61 Robert Fitzgerald and then offered readers a series of laudatory selections from major newspapers and magazines, sometimes (as in the case of Time) judiciously selecting only those sentences that would read as unmitigated accolades.

While praise for the new collection was strong and widespread, the reviews also contain a common complaint that could only be leveled against a writer with an already-established reputation and known body of work: specifically, the charge that O’Connor’s talents were, however striking, essentially limited. Writing in The Nation, for example, Webster Schott stated, “Artistically her fiction is the most extraordinary thing to happen to the American short story since Ernest Hemingway,” but he also called O’Connor “myopic in her vision.”62 Schott’s assessment represents a judgment seen in this period that marked and sometimes marred O’Connor’s reputation: what many reviewers gave with one hand—the praise of her artistic performance—they took away with the other by complaining of her “limited” subject matter. The assumption underlying many critical complaints was that strictly proscribed thematic concerns somehow devalued an author’s career as a whole. However wrong such an assumption might be, it informed much critical discussion of Everything That Rises Must Converge and O’Connor’s subsequent reputation. Walter Sullivan stated that O’Connor’s “limitations were numerous and her range was narrow,”63 assuming that one mark of literary success was the tackling of a number of different themes; writing in Jubilee, Paul Levine described O’Connor’s achievement as “austerely limited.”64 Both of these reviewers, however, felt that what O’Connor did, she did very well, Sullivan acknowledging that “her ear for dialogue, her eye for human gestures were as good as anybody’s”65 and Levine similarly describing O’Connor’s “vision” as “deep rather than wide.”66

This simultaneous faulting of O’Connor’s lack of breadth while praising her depth is found in many of the collection’s original reviews. Writing in Commentary, Warren Coffey argued that O’Connor “would not go wider than her ground” but that “nobody could have gone deeper there.”67 Richard Poirier, in the New York Times Book Review, stated, “Miss O’Connor’s major limitation is that the direction of her stories tends to be nearly always the same,” yet lent his considerable support to O’Connor’s art with the bold statement that “Revelation,” the story which earned O’Connor the 1964 O. Henry Award, “belongs with the few masterpieces of the form in English.”68 This notion of O’Connor’s limits—what amounts to a new aspect of her reputation at this time—was durable enough to survive an Atlantic crossing: a long but unsigned review in the Times Literary Supplement cautioned against “sentimental exaggeration” when judging O’Connor and described her as a “provincial writer in the truest sense”—and while her provincialism need not be regarded as a fault, the reviewer regarded it as a “major handicap,” which “meant that she knew only half the world she lived in and wrote about.”69 Faulkner, this reviewer argued, possessed both the talent and thematic treasure to earn him the reputation he enjoyed: he “had a powerful enough imagination to supply a great deal of vicarious experience. Miss O’Connor, we must acknowledge, lacked this power: her imagination worked excellently within her experience but did not rise above its limitations.”70 A reviewer for the London Observer similarly stated that “within her limits, Miss O’Connor brings off some notable feats of impersonation.”71 Ironically, another author whose reputation was forever linked to the violence in one of his early works offered a complete counterstatement to this prevailing idea: writing in The Listener, the weekly publication of the BBC, Anthony Burgess noted of the stories, “The range is astonishing.”72

Some reviewers found O’Connor limited in her thematic concerns; others found her wanting in her artistic performance. Irving Howe detected in O’Connor’s work “a recurrent insincerity of tone” in the ways she portrayed characters that he assumed she despised, most notably Julian, the failed writer and smug intellectual in the collection’s title story: “Miss O’Connor slips from the poise of irony to the smallness of sarcasm, thereby betraying an unresolved hostility to whatever it is she takes Julian to represent.”73 Similarly, in the Southern Review, Louis D. Rubin argued that “Miss O’Connor loads the dice” and “makes her sinners so wretchedly obnoxious one can’t feel much compassion for their plight.”74 Such a complaint about O’Connor’s limiting the three-dimensionality of her characters is one that would later appear elsewhere, most notably in Harold Bloom’s introduction to his Twentieth Century Views, where he argues that O’Connor’s detestation of Rayber, the smug and secular school-teacher in The Violent Bear It Away, is so strong that she “cannot bother to make him even minimally persuasive.”75

However, at the time of O’Connor’s death, such reviews about the limitations of both her form and content were outnumbered by those proclaiming her to be “a remarkable artist”76 and “one of the most gifted artists of our time.”77 But while O’Connor’s admirers argued that the praise she earned was wholly justified, the undercurrent of critical thought regarding her limitations suggested that much of the praise needed to be qualified. Writing in Ave Maria, Thomas Hoobler noted that many reviewers were anxious to not speak ill of O’Connor because of the circumstance of her recent death:

The reviewers thus far seem reluctant to take on the book as a work of art to be critically reviewed. Miss O’Connor’s growing reputation . . . and possibly the fact of posthumous publication, has produced a kind of awe, even among normally skeptical reviewers. . . . Needless to say, this reviewing-by-assent is a high compliment to Miss O’Connor’s gift, but hardly, I think, an appropriate comment on her work.78

Hoobler’s words accurately capture the spirit of many of the reviewers of this period, who came to praise O’Connor as they buried her.

O’Connor’s reputation had developed to the point where it was examined by critics alongside the work upon which that reputation was presumably based, as if the critics began gazing upon themselves. A single review can be examined as representative of this greater phenomenon. In one of the first reviews of Everything That Rises Must Converge, Stanley Edgar Hyman, whose words carried as much weight in the New Leader as Poirier’s did in the New York Times Book Review, offered a long appreciation of O’Connor’s career and death, “the cruelest loss to our literature since the death of Nathanael West.”79 After a mostly positive assessment of the collection, Hyman expanded the scope of his review by identifying what he regarded as O’Connor’s chief themes, among them the presence of evil and the gulf between the human and divine. He also corrects what he viewed as the prevailing misconceptions about her work: “Few contemporary writers have been as much misunderstood, wrongly praised, and wrongly damned as Miss O’Connor.”80 Hyman argues that while readers spoke of her violence as excessive and that O’Connor “did come to rely on death too often to end her stories,”81 her problem was a reliance on melodrama more than on the violence with which her work was associated. Hyman similarly discriminates between the ways in which O’Connor’s work was labeled “grotesque” and what it actually was: “Grotesque her fiction is,” Hyman states, “but it is never gratuitous . . . it is perfectly functional and necessary.”82 Hyman ends his review by introducing an idea about O’Connor that would take root and flourish as one of the most striking blooms of her current reputation:

To judge Miss O’Connor by any criteria of realism in fiction, let alone naturalism, is to misunderstand her. . . . The writer she most deeply resembles in vantage point is West. He saw deeply and prophetically because he was an outsider as a Jew, and doubly an outsider as a Jew alienated from other Jews; she had a complete multiple alienation from the dominant assumptions of our culture as a Roman Catholic Southern woman.83

This is not the first time in print that O’Connor and West were linked: reviewers of Wise Blood saw stylistic affinities between these two writers’ work.84 Hyman was, however, the first to link O’Connor and West as outsiders, a part of O’Connor’s reputation that endures. For example, a 1991 appreciation of The Complete Stories in the Times Literary Supplement begins with the often-told tale of how the five-year-old O’Connor trained a chicken to walk backward, a feat captured on film by Pathé News and regarded as representative of O’Connor’s future focus on “freakish creatures” with “their sense of direction all askew.”85 In the opening pages of his biography, Brad Gooch employs this anecdote to suggest how it reflects ways in which O’Connor produced work “running counter to so much trendy literary culture.”86 Other biographers have employed the same anecdote for the same reason: in Paul Elie’s 2003 joint biography of O’Connor, Thomas Merton, Dorothy Day, and Walker Percy, Elie describes the chicken as “a freak, a grotesque” that resembled O’Connor’s characters and the author herself.87 Unsurprisingly, O’Connor also described herself as “an object of considerable curiosity, being a writer about ‘Southern degeneracy’ and a Catholic at oncet [sic] and the same time.”88

This notion that O’Connor’s reputation deserved attention and, at times, needed correcting appears in other reviews besides Hyman’s; the frequency with which this notion appears suggests a desire among many of O’Connor’s readers to “fix” her reputation, in the sense of “repair” but also “make permanent.” As we have seen in other chapters, sometimes a small, seemingly unimportant notice in an easily overlooked source illuminates greater issues as effectively as the pronouncements of critics in major periodicals: in this case, an unsigned review in the Emporia (Kans.) Gazette states, “Already a Flannery O’Connor legend is taking shape.”89 This legend was one that many critics addressed in their reactions to Everything That Rises Must Converge. Reviewers took O’Connor’s talent as a given, calling her “one of the truly skilled, original, and polished talents of our time”90 or claiming that the “superb craftsmanship” of her work is such that O’Connor “can match any American writer of the century.”91 A reviewer for the Nashville Banner stated, “Her reputation is one of the largest among Southern writers, and she is considered ‘must’ reading on many college campuses,”92 but other reviewers argued that O’Connor’s reputation needed clarification: writing in the New York Times, Charles Poore noted that O’Connor was “mindlessly categorized as a ‘Southern writer,’”93 just as an unsigned review in Newsday states, “A Southern writer, a Catholic writer, Miss O’Connor escapes either catalogue through her own genius.”94 Again, a reader sees how the watchwords “Southern” and “Catholic,” once used as if they were the Rosetta stone to decoding the secret of O’Connor’s strange art, were now, barely a decade later, proving inadequate to the task of accounting for the creation of characters such as Rufus Johnson. She was still predictably compared to Faulkner, but unpredictably not in terms of geography: “It was not too long ago that Flannery O’Connor’s production was thought by some to be satisfactorily categorized by the flip label of ‘Southern Gothic.’ . . . Early criticism of another Southern writer, William Faulkner, was frequently as uncordial, but in the case of both, time showed them to be something other than practitioners of Gothic horrifics.”95 Lawrence H. Schwartz’s 1988 Creating Faulkner’s Reputation: The Politics of Modern Literary Criticism has proven Farnham correct: while the story of Faulkner’s reputation contains more drama (such as the ways in which the publishing of popular fiction changed during the Second World War) and cultural reverberations (such as the ways in which an “elitist aesthetic” arose that demanded literature be “difficult”), Faulkner’s reputation, like O’Connor’s, first reinforced the notion that he was a writer with specific regional concerns and later fostered the sense that his art transcended time and space.

O’Connor had signed a contract for the collection with Robert Giroux in 1964, in between visits to the hospital. Realizing she was too ill to revise the stories, she decided that their previously published magazine and journal versions would have to suffice, although she did revise “Revelation” and “Parker’s Back” while in Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta, initially hiding the manuscripts under her pillow for fear of being told that such activity was forbidden and then working on them for two hours a day in her room.96 After she died, Giroux arranged for the quick publication of the collection, which featured Thomas Merton’s previously quoted comparison to Sophocles on its dust jacket. He also solicited the assistance of Robert Fitzgerald, O’Connor’s close friend, to introduce the collection; this introduction is a perfect example of an author attempting to shape the reputation of another.

O’Connor first met Fitzgerald and his wife, Sally, in 1949, when O’Connor was living in New York City and revising Wise Blood. Their friendship was immediate; that same year, O’Connor left New York to live at the Fitzgeralds’ farm in Connecticut, where she paid sixty-five dollars a month for rent, lived in furnished rooms above the garage, worked on Wise Blood each morning, and babysat the Fitzgeralds’ children each afternoon. Such an arrangement worked well for O’Connor, giving her a set time in which to write, but also forged a relationship that both the Fitzgeralds and O’Connor prized for the rest of their lives. In a 1954 letter to Sally, O’Connor informed her that she was dedicating A Good Man Is Hard to Find to her and Robert “because you all are my adopted kin and if I dedicated it to any of my blood kin they would think they had to go into hiding.”97 She and the Fitzgeralds, also Catholic, spent many nights discussing writers, their own families, and their works-in-progress. While her stay with them was short—within a year she had moved to Milledgeville because of her health—her relationship with them only grew stronger: she served as godmother (with Giroux as godfather) to their third child, met them in Italy during her trip to Lourdes, and named Robert as her literary executor.

Robert Fitzgerald was thus an O’Connor insider, and Giroux’s choosing him to introduce the collection permitted a steering of the reader’s understanding of O’Connor’s character by an approved intimate. Fitzgerald’s introduction is no blurb or general impression; it is, instead, a seventeen-page combination of biography, criticism, and reminiscence—the kind of introduction modern readers might expect but that, as Jean W. Cash notes, “gave readers the first significant biographical information about O’Connor.”98 The introduction sustained many aspects of O’Connor’s reputation at that time and gave reviewers guidance on how best to assess the work of a writer so strange and seemingly at odds with many aspects of literary modernity. An analysis of Fitzgerald’s activity here reveals an act of reputation-engineering motivated by insight, admiration, and friendship.

Fitzgerald establishes his bona fides early in his introduction by describing all the O’Connor-related places he has visited and the people with whom he has shared his memories of the writer. He had visited O’Connor’s grave with her mother and spent afternoons at the Cline house (where O’Connor’s mother, Regina, was raised) and Andalusia many times: he states, “I have been in the dining room looking at old photographs with Regina”99 and “I have also been in the front room of the other side of the house, Flannery’s bedroom, where she worked” (x). Such moments, combined with his description of how he and Sally first met O’Connor in 1949, are ones in which Fitzgerald down-plays his own career as a professor of English at Princeton and Harvard and fosters the ethos of a friend more than a critic. However, his desire to instruct and, at times, redirect the course of O’Connor’s reputation is evident from the number of assertions he makes about her art. He counters the complaint that O’Connor’s work lacks “natural and human beauty” by asking the reader to consider how, in “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” Bailey’s attempts to reassure his mother and his wife’s volunteering to follow him into the woods are “beautiful actions . . . though as brief as beautiful actions usually are” (xii). He also calls “The Life You Save May Be Your Own” a “triumph over Erskine Caldwell and a thing of great beauty” (xx), correcting any readers who may have still regarded O’Connor’s setting as confined to Tobacco Road and alluding to Keats in emphasizing the “beauty” of O’Connor’s work. The idea that O’Connor’s work contained any “human beauty” was one that ran counter to earlier notions of her as a writer whose characters are (as an earlier reviewer described them) “devoid of honor, loyalty, and for the most part, decency”100 or simply, as the chorus of reviewers often sang, “grotesque.”

Unlike dozens of critics before him, Fitzgerald compares O’Connor not to the usual figures but instead to T. S. Eliot, the first time in print that such a comparison was made (but not the last). Fitzgerald argues that both Eliot and O’Connor raise “anagogical meaning over literal action” and even remarks that Eliot “may have felt this himself, for though he rarely read fiction I am told that a few years before he died he read her stories and exclaimed in admiration of them” (xxx). (Time has proven Fitzgerald’s story correct: in 1979 Russell Kirk wrote of his recommending her work to Eliot, who read it and responded in a letter, “She has certainly an uncanny talent of a high order but my nerves are just not strong enough to take much of a disturbance.”101) The number of readers who understood Eliot’s work well enough to grasp Fitzgerald’s notion of the poet’s “analogical meaning” in relation to O’Connor’s is impossible to determine; still, one senses Fitzgerald’s desire to bolster O’Connor’s reputation through such a comparison. More accessible to the general reader is Fitzgerald’s argument about O’Connor’s “limits”—a topic seized upon by many of the collection’s reviewers that Fitzgerald may have anticipated by discussing it in his introduction. After pointing out the similarities between O’Connor’s previous work and the stories in this collection, Fitzgerald admits that “the critic will note these recurrent types and situations,” how “the setting remains the same” and how “large classes of contemporary experience . . . are never touched at all” (xxxii). But he also warns that those who find this a weakness are themselves limited in their understanding of O’Connor’s work:

In saying how the stories are limited and how they are not, the sensitive critic will have a care. For one thing, it is evident that the writer deliberately and indeed indifferently, almost defiantly, restricted her horizontal range; as pasture scene and a fortress of pine woods reappear like a signature in story after story. The same is true of her social range and range of idiom. But these restrictions, like the very humility of her style, are all deceptive. The true range of the stories is vertical and Dantesque in what is taken in, in scale of implication. (xxxii)

Many reviewers either ignored Fitzgerald’s advice here or simply did not read it, complaining of O’Connor’s repetitious plots, character types, and themes. Fitzgerald’s assertion that the supposed limits were actually a deliberate restriction, the better to focus on a “scale of implication” akin to Dante, is his attempt to fix O’Connor’s reputation in a manner that he, as her friend, fellow author, and admirer, could approve. His long-term success in this regard can be seen in Understanding Flannery O’Connor, a 1995 book that outlines O’Connor’s work and concerns for general readers in which the author points out the similarities among O’Connor’s stories but urges that “the significant focus” is “a vertical relationship, the individual with his or her Maker, rather than a horizontal involvement, individuals in community with each other.”102 Others may have faulted O’Connor for not creating more three-dimensional characters, but to Fitzgerald, this was not a deficiency.

Most of the original reviews of Everything That Rises Must Converge noted Fitzgerald’s introduction but simply mentioned it as a feature of the text. Even those who lauded it as “wise and intelligent,”103 “gentle and objective,”104 or “valuable and perceptive”105 did not say much else about it. A minority of critics mentioned the same elements of O’Connor’s life and art as Fitzgerald did, making them star pupils in his imaginary classroom. A few reviews offered more specific praise and, more importantly, a measure of Fitzgerald’s influence by echoing his themes and assertions. Writing in Best Sellers, John J. Quinn, the force behind the Winter 1964 issue of Esprit, stated that Fitzgerald’s “penetrating introduction to the artist as a person and as an artist qualifies him as the expert curator of the O’Connor Gallery,”106 while another noted Fitzgerald’s “valuable” introduction, stating, “he gives a gratifyingly clear portrait, and it is apparent that he understands fully what she was about in her writing.”107 Only one of the original reviewers found fault with Fitzgerald, arguing that the strength of O’Connor’s art was that while it was “Catholic, but not obtrusively or aggressively so,” Fitzgerald’s introduction was “obtrusively Catholic, unfortunate and misleading.”108 This assessment, however, was the exception to the general rule. The inclusion of an introduction, the choice of Robert Fitzgerald to compose it, and the timing of such an essay all converged to steer O’Connor’s reputation to an even more prominent place. In his biography, Paul Elie describes Fitzgerald’s introduction as “mannered and overwrought” yet acknowledges that it “served many readers that year as the first portrait of the artist” and secured her reputation more firmly: “No longer would Flannery O’Connor be mistaken for a gentleman or a rural primitive. She was a woman, and a literary saint.”109

Despite his friendship with O’Connor—or perhaps because of it—Fitzgerald was not above engaging in some revisionist reputation history. When describing the publication of Wise Blood, Fitzgerald states, “The reviewers, by and large, didn’t know what to make of it. I don’t think anyone even spotted the bond with Nathanael West. Isaac Rosenfeld in The New Republic objected that since the hero was plain crazy it was difficult to take his religious predicament seriously. But Rosenfeld and everyone else knew that a strong new writer was at large” (xviii). Indeed, not “everyone” knew that “a strong new writer was at large,” not even Rosenfeld himself, who dismissed O’Connor’s talents and complained that O’Connor’s novel suffered from a lack of clarity, confused religious ideas, and a style that he found “inconsistent” with the idea that “there is no escaping Christ.”110 That none of this is mentioned by Fitzgerald is hardly shocking and perhaps understandable: Joyce Carol Oates noted in 1965 that O’Connor’s early death had “perhaps obscured critical judgment.”111 Perhaps—but it is certain that O’Connor’s death obscured, for some, the memory of how she was first received, as may be seen in a review appearing in Newsweek: “With her first novel, Wise Blood, it was clear that a major writer had arrived; and this conviction was confirmed by the first collection of stories, A Good Man Is Hard to Find. With her second novel, The Violent Bear It Away, nearly all doubters were converted to passionate belief.”112 The very phrasing of the Newsweek reviewer echoes Fitzgerald’s style and content, as it does his tendency to speak in absolutes. O’Connor’s status as a “major writer” may have been clear to the reviewer, but not to all who first encountered her work, such as Katherine Scott, O’Connor’s first writing instructor at Georgia State College for Women, who reflected the sentiments of many original reviewers when she said of Wise Blood, “A character who dies in the last chapter could have done the world a great favor by dying in the first chapter instead.”113

How the cause of her death—her eventual succumbing to the systemic lupus erythematosus with which she was diagnosed in 1951—added its own aura to “the O’Connor legend” claims legitimate attention. Had she died in an automobile accident, her death might still have affected her reputation; that she died because of a slowly working disease about which relatively little was known allowed critics to link her illness with her art in ways they found fascinating but that O’Connor found repulsive. Writing to Maryat Lee in 1960, O’Connor fumed, “I don’t want further attention called to myself in this way. My lupus has no business in literary considerations.”114 The occasion was a review in Time of A Good Man Is Hard to Find that described her as a “bookish spinster” and one whose suffering could have seemed to prevent her from writing: “She suffers from lupus (a tubercular disease of the skin and mucous membranes) that forces her to spend part of her life on crutches. Despite such relative immobility, author O’Connor manages to visit remote and dreadful places of the human spirit.”115 The reviewer is incorrect in both his description of lupus and his assumption that O’Connor’s medical condition was somehow responsible for her subject or thematic concerns. The “relative immobility” of which the reviewer speaks was never experienced by O’Connor at this time. She did need a cane and, eventually, two crutches to walk, but she was far from a bedridden victim: from 1955 (the year A Good Man Is Hard to Find was published) to 1963 (the year before her death), O’Connor flew to New York City to appear on television, toured Europe for seventeen days with her mother, gave dozens of talks at universities as far as Notre Dame and the University of Chicago, and visited a number of states as far from Georgia as Texas, Louisiana, and Minnesota. Granted, she did much of this traveling with the assistance of her crutches, and sometimes found it trying, but she was no Emily Dickinson shut off from the world or, as V. S. Pritchett inaccurately described her in the New Statesman, “an invalid most of her life.”116 Still, O’Connor’s lupus and its imagined psychological effects became a large part of her reputation and proved irresistible to many reviewers seeking, once again, to explain away O’Connor and to account for the strangeness of her art. To many critics, her illness had become her muse, an explanation for her choice of themes and manner of exploring them. And despite the disdain that O’Connor would have shown for it, this part of her reputation still holds: in the mid-1990s, Chelsea House published a series of books for young readers, Great Achievers: Lives of the Physically Challenged. O’Connor had a volume devoted to her and joined the ranks of Louis Braille, Stephen Hawking, Itzhak Perlman, Roy Campanella, Julius Caesar, and Franklin D. Roosevelt, all subjects of other volumes.

One particularly mawkish reviewer of Everything That Rises Must Converge wrote that O’Connor’s “personal awareness of death” was so strong that her readers could “sense the shock of identification that Flannery O’Connor must have felt when one of her characters succumbed to his grisly fate. It is as if the author is telling the same story over and over in the hope that it will go away.”117 As he complained of O’Connor’s bitter portrayal of “weak humans,” Louis D. Rubin ascribed what he viewed as O’Connor’s artistic failings to her illness: “Any human being who had to endure what Flannery O’Connor did for the last years of her all-too-brief life . . . would certainly have tended to view the human condition with more than the customary amount of distrust.”118 A reviewer for the British Association for American Studies Bulletin attempted to account for the power of O’Connor’s stories on medical and psychoanalytic rather than artistic grounds:

It is a book conceived of by a dying woman who is not afraid of going to hell: she’s been in it too long and has begun to find it cozy and dull. Flannery O’Connor was imprisoned in a wracked body for most of her creative life. Hopelessly sick, bald, and deformed, she writes with a vengeance. . . . Her books are impartial, unsparing, and hilariously beyond despair. She is the only true ghost writer. Having lost all, she invited you to join her in the realm of the hopeless.119

Anyone who reads O’Connor with even a modicum of charity will recognize the falseness of these claims, for her fiction as a whole dramatizes the folly of what she viewed as a trendy, modern nihilism: consider Hulga in “Good Country People” as one of many examples of O’Connor’s attack on what she viewed as a hollow hopelessness. Without the hope of a place where he “counts,” Bevel (in “The River”) is simply a drowned boy; without the hope of Heaven, men turn into Misfits. The reviewer for the Times Literary Supplement also engaged in perpetuating the idea of lupus-as-muse, noting, “She is writing of death, of its meaning to life, from the depths of her experience of gradually dying.”120 This idea that O’Connor was motivated by her “experience of gradually dying” is one that O’Connor would have mocked, perhaps arguing that she had been engaged in this “experience,” like everyone else, since birth: as Old Mason Tarwater says to his great-nephew, “The world is made for the dead. Think of all the dead there are. . . . There’s a million times more dead than living and the dead are dead a million times longer than the living are alive.”121 Few American writers were as aware of our “gradually dying” than the creator of the Misfit; to suggest that O’Connor’s lupus, more than her imagination, was responsible for her fiction is another example of the continual desire to account for the sources of O’Connor’s uncanny art, a desire that affected her reputation with the publication of each new book.

If the testimonials collected in Esprit illuminate a general critical and national belief in the importance of O’Connor’s fiction and in her admirable character, the publication of Mystery and Manners in 1969 marked an even greater jump in O’Connor’s critical stock. This volume of occasional prose was assembled by Robert and Sally Fitzgerald, who collected and reshaped a number of O’Connor’s talks and lectures on the nature and practice of writing fiction; the collection also includes an essay that had originally appeared in Holiday magazine on raising peacocks as well as the previously mentioned introduction to A Memoir of Mary Ann. Published by Robert Giroux four years after Everything That Rises Must Converge and five years after O’Connor’s death, Mystery and Manners marked a continuation of the course O’Connor’s reputation was taking from local oddball to respectable literary oracle. The specialist in regional grotesques had become a critic to be discussed in the same hushed tones used when discussing Keats, Eliot, Sidney, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Pope, and Aristotle—all of whom reviewers used as comparatives when describing O’Connor’s insights into literature.122

However, at this point, the author to whom reviewers most frequently compared her was Henry James, whom O’Connor herself referenced throughout her speeches and letters. An unsigned review in the New Yorker complained of the essays’ repetitiousness yet ended by describing the book as “truer and sounder and wiser about the nature of fiction and the responsibilities of reader and writer than anything published since James’s The Art of the Novel.”123 Clearly, this was high praise. As James’s readers did when they read the Master’s collected prefaces, many of O’Connor’s readers viewed her pieces here as guides to her overall approach. Like James, O’Connor understood literature as a faithful record of life—“faithful” suggesting both O’Connor’s desire to re-create the physical world of the senses and a world that gave form to her own Catholic values and assumptions. And just as James’s prefaces illuminate more than the specific novels they precede, many reviewers found the pieces in Mystery and Manners to likewise illuminate more than their author’s own work: in the words of John J. Quinn, the collection should “rank with the precious few classical studies on the art of fiction ever to be published.”124 A critic for Publishers Weekly described Mystery and Manners as “practically a handbook” on the art of writing fiction,125 and other reviewers exhorted “anyone interested in the craft of writing”126 to read this “lucid and satisfying comment on the art of the short story and the nature of the storyteller’s gift.”127 Writing in the New York Times, D. Keith Mayo described his immediate reaction to the collection as one of “gratitude”: “It seemed to me, it still seems, that I had never read more sensible and significant reflections on the art of writing.”128 A writer for Kirkus Reviews described the book as “obligatory in understanding the quintessential aspects of the short story.”129 Many other reviewers echoed these sentiments. O’Connor’s opinions on art, like her themes, were now seen as transcendent, an aspect of her reputation that remains today.

But there was more to the reaction to Mystery and Manners than praise for O’Connor’s Jamesian insights into the art of fiction. Critics viewed the collection as a means to understanding what they still regarded as her strange and challenging fiction, a figure in the carpet that would make the freaks less freakish. As with Wise Blood, reviewers searched for a way to bring O’Connor’s strangeness to heel; unlike the case of O’Connor’s first work, they now had what they saw as a figurative key to O’Connor’s kingdom, an assumption reflected in the very language they used to praise it. For example, writing in the Charleston (W.V.) Gazette, W. M. Kirkland urged the collection on those who had been baffled by the likes of Hazel Motes or Mason Tarwater: “Readers who tried unsuccessfully to ‘get anything out of’ her novels and short stories, but who sensed that she was up to something, might well read these critical essays to see what Flannery O’Connor was really up to. She did, indeed, know what she was doing.”130 The assumption here, that authors have secrets or, in the words of another reviewer, “something like a system”131—and that Mystery and Manners could be used as a kind of literary enigma machine—appears in many of the book’s original reviews. The historian of popular culture M. Thomas Inge praised the collection for reasons identical to Kirkland’s: “Anyone who wishes to get at the heart of Miss O’Connor’s impressive achievements as a fiction writer can do no better than to read these pieces. With remarkable clarity, they define her stance and explicate her intent in a way that second-hand criticism cannot match.”132 Inge later speaks of the book’s “utilitarian value,” again emphasizing the view of Mystery and Manners as a means to clarify the mysteries mentioned in its title. Other reviewers offered the same notion: a writer for the Southern Review called the essays “invaluable in providing abstract formulations of attitudes and values that are dramatized in the fiction.”133 In 1931 Leon Edel argued that James’s prefaces were the equivalent of his “placing in the hands of the readers and critics the key to his work,” although “very few have ventured to place the key in the lock and open the door.”134 Mystery and Manners was similarly seen as an explication of O’Connor’s oeuvre or, as one reviewer described it, “a welcome gift, a tiny key to a door or two in a Southern mansion of wondrous beauty.”135

In her review of Mystery and Manners for the Village Voice, Jane Mushabac observed, “It is difficult to imagine now, when we have become such gluttons for horror in our fiction, that critics and the public were once irked by all the poverty and violence in Flannery O’Connor’s fiction.”136 The critical community’s understanding of O’Connor had been accelerated by her early death, her critical stock had risen, and her identity as a Catholic author was established. The response to Mystery and Manners also strengthened the connection between O’Connor and her favorite fowl, a connection also fostered by the collection’s cover design, which featured, of course, a peacock. In the Chicago Tribune, Charles Thomas Samuels drew the comparison: like the peacock, he argued, O’Connor was “partly deformed and partly splendid, symbol of the creator’s mingled ludicrousness and glitter.”137 Presumably because of its strangeness, the peacock was described by other reviewers as a “hellish and heavenly”138 creature and “a bird possibly only Flannery O’Connor could love.”139 A writer for the Times Literary Supplement stated that the peacock now seemed “a living allegory of her fiction,”140 while a critic for Catholic World went as far as one could presumably go in making a comparison: “As the peacock stands on a busy road and spreads his tail in disdain of an oncoming truck, so Miss O’Connor scoffs at contemporary philosophies of amorality, anti-mystical approaches to reality, or disbelief in the Devil’s existence.”141 The peacock had become a symbol of the author, an outward and visible sign of an inward and invisible talent, a talent that critics and reviewers now almost universally viewed as being present since 1952 and that even death could not stop from growing exponentially.