Chapter 5

Chapter 5

Chapter 5

Chapter 5

In 1968 Robert Giroux wrote Robert Fitzgerald about a request he had received from the actor Tony Randall, who sought to mount a film production of “The Artificial Nigger.” Randall was not yet branded as Felix Unger, but his reputation as history teacher Harvey Weskit in Mr. Peepers had taken root, causing Giroux to comment, “I think it would be a miracle for anyone to make a good movie of ‘The Artificial Nigger,’ let alone Tony Randall.”1 The project never materialized, but Giroux’s response reflects a number of issues regarding the ways in which the adaptation of an author’s works can affect his or her reputation. First, Giroux’s calling such an adaptation a “miracle” emphasizes his and others’ belief that certain texts are simply untranslatable into other media, a belief that may strike one of O’Connor’s readers as reasonable: the story climaxes in pages of interior action, where Mr. Head feels the “action of mercy” working on him as he stands as still as the statue upon which he gazes. As Joy Gould Boyum notes in Double Exposure: Fiction into Film, “If one were to accept traditional notions of what is possible for the screen, the work of Flannery O’Connor might seem utterly, unequivocally unfilmable.”2 Second, Giroux’s dismissive “let alone Tony Randall” comes from the assumption that decisions involving any production will be evaluated according to how well the viewer thinks the adaptation has captured the spirit of the original. Of course, there have been many artists whose adaptations have outshone their sources, Hitchcock being the most notable example. But adaptation, like everything else in the film industry, is a bet against very difficult odds.

Randall was one of many who sought permission to adapt O’Connor’s work. Amateurs and professionals alike frequently asked O’Connor’s agent, Elizabeth McKee, for her legal blessings. She was asked to grant film rights to “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” “The Life You Save May Be Your Own,” and A Memoir of Mary Ann, Hungarian television rights for “The Comforts of Home,” and theatrical rights to “Good Country People.” To all these requests and many others, McKee referred the writers to Regina (who had final say) but often wrote about them to Giroux, who reassured her in counseling Regina to refuse permission.3 Those in O’Connor’s inner circle assumed that her work should remain wholly literary and not become sullied by contact with any amateur screenwriters or more powerful players, such as Robert E. Jiras, a producer who sought to secure the rights to “The River” and sell them to the highest bidder.4

However, Giroux, McKee, and Regina did relent, and did so enthusiastically, when a figure from O’Connor’s past sought to bring his vision of Wise Blood and “O’Connor country” to the big screen. In the early 1970s, Michael Fitzgerald—the oldest son of Robert and Sally—attempted to make a name for himself as a Hollywood producer. Like so many others, however, he eventually found his imagined career an example of the triumph of hope over experience. “It was the usual story in Hollywood,” he explained regarding his many false starts and lack of progress.5 Eventually, he decided that if he were going to expend effort and money making a film, he would make one that he found interesting from start to finish. Fitzgerald wanted to produce a film that would, in his words, give his audience “a jolt” and eventually decided on the source material that could produce such an effect: “Now what do I pick? If I can actually get it made, it’ll be so different from anything else that people will be compelled to pay attention to it. And so different from anything else that I will be able to attract talented people to help in the making of it. And suddenly, Flannery sprang back into my memory.”6 O’Connor had babysat Michael Fitzgerald and his brother, Benedict, when she stayed at his parents’ Connecticut home and finished Wise Blood. But the aspiring producer claimed this neat family tie was secondary in importance to the force of O’Connor’s reputation as someone whose work was “so different from anything else” and who could supply the necessary “jolt” to both an audience and Fitzgerald’s career. Her reputation had, according to Fitzgerald, prompted him to embark upon his adaptation of Wise Blood, an adaptation endorsed by Giroux, McKee, and Regina.

Next on the list of insiders, Fitzgerald determined to midwife O’Connor’s work between author and public. But the insider was not alone: others joined him, such as his brother, Benedict, who co-wrote the screenplay, and Sally, who dressed both the actors and the sets. (Benedict would continue to write screen adaptations for television and co-wrote the screenplay for The Passion of the Christ.) As with the publication of and introductions to Everything That Rises Must Converge and The Complete Stories, a member of O’Connor’s inner circle attempted to bring her work before a larger audience and shape the ways in which her work would be received. Eight years after The Complete Stories and fifteen years after her death, elements of her reputation would resurface and be reinforced as critics responded to a “third edition” of Wise Blood, this time with John Huston complicating its reception by virtue of his own artistry and attitude toward O’Connor’s concerns.

The continuing reputations of Huston and O’Connor might seem to suggest an insurmountable incompatibility and a doomed partnership. By the time Wise Blood went into production in 1979, Huston was well known for a body of work (and personal life) that suggested a dismissal of all that O’Connor, quite literally, held sacred. While filming The Bible: In the Beginning in 1966, Huston remarked:

Every day I’m being asked if I am a believer and I answer I have nothing in common with Cecil B. DeMille. Actually, I find it foolishly impudent to speculate on the existence of any kind of God. We know the world was created and that it continually creates itself. I don’t think about those things, I’m only interested in what’s under my nose. Also, I believe that whatever man erects, builds and creates has a religious meaning. A painter, when he paints, is religious. The only religion I can believe in is creativity. I’m interested in the Bible as a universal myth, as a prop for numerous legends. It’s a collective creation of humanity, destined to solve, provisionally and in the form of fables, a number of mysteries too disquieting to contemplate for a nonscientific era.7

However, two aspects of Huston’s reputation as a director made him a desirable choice for the brothers Fitzgerald. The first was his long record of skillfully adapting novels into film. Since his first feature—The Maltese Falcon in 1941—Huston had consistently demonstrated profound respect for his source material. In a review of Wise Blood, Vincent Canby noted, “Movies do many things, but they don’t honor the written word,”8 a rule to which Huston’s work often proved the exception. Almost all his films were adaptations of previously published fiction or previously produced plays, and he showed a remarkable ability to translate different genres, such as pulp fiction (The Maltese Falcon, The Asphalt Jungle), adventure yarns (The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, The African Queen), and moody character studies (The Night of the Iguana, Reflections in a Golden Eye) into successful films. Huston also never shied away from more highbrow literary sources, such as The Red Badge of Courage and The Man Who Would Be King; as David Thomson noted, Huston showed a “Selznick-like urge to cover the respectable literary waterfront.”9 And while Moby-Dick and The Bible may be his less-impressive adaptations, he had a reputation as a director who never sought to modify or “improve” his source material. As he said of The Maltese Falcon in particular and adaptation in general, “You simply take two copies of the book, paste the pages, and cross out what you don’t like.”10

Huston’s reputation also made him desirable to the Fitzgeralds for his straightforward shooting style, which one critic aptly described as “unassuming naturalism.”11 Despite his monumental ego and skill at self-promotion, Huston never made himself the unseen star of his films or engaged in the kind of self-reflexive camerawork that reminds viewers that they are in the director’s hands. As Benedict Fitzgerald noted, such a style was crucial to an adaptation of Wise Blood because it reflected O’Connor’s own directness of vision: “We were lucky to have thought of John Huston. There were others that we were considering but they would have been so taken by the allegorical nature of the storytelling—by either what they would have considered the grotesque or by the allegory itself—that it would not have been a story told the way good stories are told: very straightforward. John had never done anything but. He just liked to tell the story the way it was.”12 Huston’s invisible—as opposed to heavy—hand was noted by some of the film’s original reviewers, as when John Simon noted that Huston had not “indulged himself in directorial liberties”13 or when Joy Gould Boyum noted that Huston’s camera “never underscores, never labors and never exploits.”14 If the Fitzgeralds were going to entrust Wise Blood to a director, they would only trust one who would “honor the word” by not attempting to change the manner in which O’Connor presented her chosen issues. Whether he believed in Christ was not as important as whether he believed in O’Connor.

Huston shot Wise Blood in Macon, Georgia, and—like everyone else involved in the production—worked for minimum salary.15 With its budget of less than two million dollars (as opposed to eight million for his previous film, The Man Who Would Be King) and use of locals in many supporting roles, Wise Blood, like the novel upon which it was based, prompted questions about its marketability and wide appeal. The film premiered at Cannes and was then shown at the New York Film Festival where it received enthusiastic reviews. However, no major distributor offered to market it or manage its broad theatrical release: Archer Winsten (in the New York Post) described the film as “an artistic triumph that commercial distributors were slow to grab when it first surfaced at the Film Festival. They wouldn’t even grab when heavy crix said ‘ooh-la-la’ with laurel wreaths.”16 Writing in the Village Voice, Andrew Sarris called Wise Blood “precisely the kind of property that would have made the late Louis B. Mayer turn over in his grave”17 and elsewhere predicted, “It’s doubtful that this film will find a mass audience.”18 Huston himself acknowledged, “It was hardly the sort of thing to attract investors.”19 Eventually, New Line Cinema—then a fledgling distributor of art-house films—bought the distribution rights, prompting a reporter for Premiere to note that even a “front page rave in Le Monde” could not woo the Hollywood power brokers; the reporter also quoted Michael Fitzgerald as being “baffled by the response of the majors,” saying, “I don’t quite understand why . . . but they’re terrified of it.”20 Fitzgerald later noted that distributors regarded it as “the least commercial movie ever made.”21

However, anyone familiar with O’Connor’s reputation—as Fitzgerald, despite his presumed perplexity, surely was—could identify the source of that terror: O’Connor’s work was financially risky because it was morally so. Taking O’Connor seriously entailed examining, or at least entertaining, her assumptions about the gulf between God and man, a gulf into which theatergoers and Hollywood studios were never eager to peer. Writing in Time, Frank Rich noted, “It is not surprising that independent producers, rather than a Hollywood studio, took the considerable risk of financing the project.”22 Variety described the film as “downbeat” and one “needing hard sell due to its ambivalent treatment of the kinky religious scene, though it does give some insight into the extension of these loner fanatics into sects.”23 The critic, of course, assumes that Huston was making an exposé about cults, rather than telling the story of a man whose spiritual intuition—his wise blood—leads him to a truth beyond the walls of any church. In a laudatory review, David Ansen described the film as “determinedly uningratiating”24 to its viewers, a characteristic that, of course, would not prompt distributors to come calling. Similarly, Box Office advised its industry readers that the “excellent performances” and the “low-level documentary style photography make this one of the best pictures in Huston’s long career—but unfortunately not the most commercial.”25 Rex Reed, however, regarded the film’s lack of commercial appeal as a badge of artistic honor, stating, “Wise Blood makes no bid for box-office sweepstakes. It looks like it was made by people with no idea of what commercial gimmicks are,” calling this “unusually welcome” lack of gimmickry “a strength.”26

All these remarks about O’Connor’s lack of marketability call to mind Rinehart editor John Selby’s feud with O’Connor over the first nine chapters of Wise Blood, when he sought (in O’Connor’s words) to “train it into a conventional novel.”27 As O’Connor wrote of the book to Elizabeth McKee in the summer of 1948, “I cannot really believe they will want the finished thing.”28 O’Connor anticipated the novel’s lack of commercial appeal but wanted it to be published by a sympathetic, although not necessarily empathetic, house: “I want mainly to be where they take the book as I write it.”29 The same principle applied to the Fitzgeralds and Huston, who never sought to train the source material into a conventional film. Doing so would have betrayed what drew them to O’Connor and also traduced Huston’s method of not placing too many of his fingerprints on his source material.

The press kit provided to the first audiences at the New York Film Festival reflects O’Connor’s reputation in 1979 as well as the means by which Fitzgerald and his co-producer (his wife, Kathy) attempted to present an accessible version of O’Connor’s work to a moviegoing public. After beginning with the puffery one would predict in a press kit (“This chilling adaptation of Flannery O’Connor’s brilliant first novel returns director John Huston to the hardheaded style of Fat City”30), the Fitzgeralds and their publicity team offered six quotations by O’Connor on a separate page headed, “Author Flannery O’Connor on Wise Blood and Life.” The first of these, taken from a letter concerning The Violent Bear It Away, seems intended to disarm the skeptics who had pigeonholed O’Connor as a “religious fanatic”: “I suppose a book like mine attracts all the lunatics.”31 Another reflects the producers’ desire to highlight O’Connor’s humor, however dark: “In my own experience, everything funny I have written is more terrible than it is funny, or only funny because it is terrible, or only terrible because it is funny.”32 The most important quotation, however, is from a letter to John Hawkes indicating how the producers wanted their viewers to regard Motes’s struggle and eventual self-mutilation. It contains what they viewed as the central issue of the film, one that the film’s leading man had debated with Huston and that the critics would soon debate with one another: “The religion of the South is a do-it-yourself religion, something which I as a Catholic find painful and touching and grimly comic. It’s full of unconscious pride that lands them in all sorts of ridiculous religious predicaments. They have nothing to correct their practical heresies and so they work them out dramatically.”33 O’Connor dramatizes Motes’s wise blood as only he can imagine: by “working it out dramatically” and blinding himself. As Michael Fitzgerald stated with some degree of superiority, “If Haze were an educated person, he might have joined a monastery. But he’s a hillbilly and he goes all the way as he can. . . . When he finds the truth in the last way he expects to find it, he goes all the way with what he could do.”34

The last of the press kit’s quotations was taken from the same letter to Hawkes and was included by the producers to imply that Motes’s struggle was not born of madness or fanaticism, but a desire to accept as truth what the world seemed to mock: “My gravest concern is always the conflict between an attraction for the Holy and the disbelief in it we breathe with the air of the times.”35 Such conflict was acknowledged by those critics who viewed Motes in a sympathetic light but was wholly disregarded by others, who viewed Motes as a fool or fanatic for acting on the promptings of his “attraction for the holy”—his wise blood. The remainder of the press kit offered a biography of Huston in which Wise Blood was described as “steeped in rural mysticism” and the result of O’Connor’s “vivid and baroquely imaginative world.” The absence of the adjective “grotesque” is surely no accident; “baroquely imaginative” substitutes for “grotesque” and sheds, with its tone of admiration, a light of critical favor on what was once viewed as O’Connor’s works’ defining characteristic. The Fitzgeralds knew that if Motes repulsed the viewers or was viewed as a caricature from the Bible Belt, Wise Blood would be much less effective and a betrayal of O’Connor’s intentions. It would be a film grounded in mockery instead of the uneasy empathy that O’Connor sought to evoke.

Many critics responded to the film in ways that the Fitzgeralds and Huston had hoped. Of all the original reviewers, Vincent Canby, writing in the New York Times, offered the most enthusiastic praise, calling Wise Blood “one of John Huston’s most original, most stunning movies” that proved the aging director to be “in his top form.”36 In a 2008 interview, Michael Fitzgerald noted, “The reviews from all over the world were extraordinary. I don’t think people had quite seen anything like this. And most people were not familiar with Flannery O’Connor and so the film got a staggering amount of attention at Cannes and was bought all over the world.”37 Fitzgerald’s claims here are reinforced by Huston’s having received a standing ovation after the film’s screening at Cannes,38 although Huston’s age and résumé surely boosted the reception; the film was frequently praised for its decidedly un-Hollywood subject matter and the age of its director as much as any specific elements. For example, Frank Rich called it “the most eccentric American movie in years,”39 and Jack Kroll, in Newsweek, described it as “Huston’s 34th film and one of his best,” adding, “to do such work at 73 is the mark of some kind of a heroic figure.”40 Tim Pulleine in Sight and Sound called it “the work of an old master but scarcely of an old man,”41 and David Ansen ended his Newsweek review by describing Wise Blood as “further confirmation that Huston is still in his prime.”42 Rob Edelman in Films in Review labeled it “an eerie, melancholy little film about eerie, melancholy little people,”43 using “little” as large praise in an era that had seen the birth of the blockbuster with Jaws (1975), Star Wars (1977), Superman (1978), and Rocky II (1979). Critical resistance to what seemed a new commercialism—and confirmation of what Fitzgerald called the distributors’ “terror” at optioning a film such as this—were found in reviews such as Edelman’s, in which he praised Huston as “concerned not with pointlessly splashing millions of dollars across the screen but with exposing his audience to ideas, emotions, human beings and human frailties,”44 or in the headline of a review that read, “ ‘Wise Blood’ is a low-budget miracle.”45 The work’s lack of mass appeal bestowed other kinds of clout upon it.

Like many of the novel’s original readers, some critics found themselves unable to identify just what they had seen or to articulate O’Connor’s thematic concerns. Even the sympathetic Roger Angell, in his generally laudatory review for the New Yorker, sounded like Polonius as he admitted to being “startled” by his “attachment to a work that may be a broad-scaled holy-picaresque farce, or a Southern-regional historical urban-pastoral, or perhaps a plain metaphysical tragedy.”46 Angell’s description recalls the tongue-tied reviewers of the novel, who argued that O’Connor’s “farce gets in the way of her satire and will not support the full implications of her allegory”47 or others who simply called the novel “an obscure piece of writing”48 and “not a book for casual reading.”49 Some of the film’s reviewers were simply inaccurate, resorting to prepackaged phrases and assumptions about the South to help them articulate what had eluded them, as when Archer Winsten, in the New York Post, stated, “It’s not easy to think that it can be an enjoyable entertainment, unless you dote on religious fanaticism, fools, and religious mania,”50 recalling the critics who off handedly (and incorrectly) described the novel as a “satire” of “evangelical preachers with banjo quartets, uniforms, concert soloists, and cheap sensationalism.”51

The film’s reviews reveal the watchword “grotesque” as still current and used to account for (and sometimes belittle) what baffled or disturbed those asked to take Huston’s film and O’Connor’s characters seriously. Stanley Kauffmann, for example, dismissed the film as too much akin to Huston’s Night of the Iguana and Reflections in a Golden Eye: “Now it’s Southern grotesque time again, and again Huston has fumbled.”52 “Grotesque” was, to Kauffmann, a way to easily contain and dismiss O’Connor’s art. Philip French, in the London Observer, added the runner-up of equally generic labels when he described the film as “a grotesque collection of Southern gothic characters involved in the ‘religion business.’”53 However, by now, almost thirty years after the novel’s publication, the watchword was not always pejorative. For example, in The Nation, Robert Hatch observed, “The film, like the book, is wildly grotesque” but also called it a “triumph,” arguing, “The humor is often grotesque, but we are startled at how often we laugh at this comedy of fanaticism and despair.”54 (Hatch also compared Huston’s film to The Tin Drum, another adaptation of a work that startled many readers and gave them the kind of “jolt” of which Michael Fitzgerald spoke.) In a glowing review for the Wall Street Journal, Joy Gould Boyum described Motes as a “grotesquely comical contradiction” and praised Huston for re-creating “the grotesque imagery and internal logic of O’Connor’s phantasmagoric parable.”55 David Ansen used the term as wholly complimentary, stating, “Wise Blood, a virulently comic, grotesquely unforgettable adaptation of Flannery O’Connor’s celebrated novel of customized redneck religion and redemption, is as strange and original a movie as Huston has ever made.”56 “Grotesque” had evolved along with critics’ understanding of O’Connor’s art.

Ansen’s phrase “redneck religion” raises the issue of how critics responded to O’Connor’s southern roots. Despite Giroux’s success in making her an “American” author, many critics still viewed O’Connor as something of a regionalist reporter and Huston as a man with a hidden camera, offering dispatches from the Sahara of the Bozart. Writing in New York magazine, David Denby resorted to hyperbole while stating that the film was set in “the familiar, Jesus-haunted South, where a ranting prophet, saint, or con man stands on every corner”57—a tired formula as laden with assumptions about the South as any to be found in the history of O’Connor’s reception. John Simon echoed these assumptions when he, in the same matter-of-fact tone found in many such remarks, stated that the film portrayed “the phenomena that once almost blanketed the South and still lives in many a not-so-isolated pocket.”58 Often critics were so devoted to their assumptions about the South that they told the film what it meant, rather than vice versa. For example, Archer Winsten in the New York Post declared that Huston’s “amalgam of extreme religiosity, sex, unquestioning belief” presents “a curiously vibrant portrait, one that any student of the South can recognize.”59 But Winsten’s desire to mock the hicks interfered with his judgment, for surely Hazel Motes is far from an example of “unquestioning belief.” Frank Rich praised Huston for making what he assumed was an exposé: “The film’s settings,” he wrote, “are glutted with eclectic religious artifacts and the documentary details of the backwater South.”60

Critics spoke of “the South” (as opposed to the actual South) casually and un-questioningly; indeed, several important critics wrote as if the film’s production design, complemented by Huston’s straightforward shooting style, made Wise Blood more documentary than drama. For example, New West praised Huston for taking his viewers “into a world we’ve rarely seen on film—the seedy South of obsessed religious evangelists and their pathetic prey,”61 while a blurb regarding the 1986 video release of the film described it as “centered on the gripping power of Bible Belt fundamentalism.”62 Again, preconceptions trumped critical judgment: Motes is far from a “religious evangelist,” and the power that grips Motes exhibits the forms, but not the content, of what one would label “fundamentalism.” As for “pathetic prey,” Motes’s and Hawks’s troubles arise from their very lack of anyone to gull: no one will heed them. The London Observer spoke as if Huston had reported on-location from what it called “Billy Graham country” where “religion and guilt pump in the blood”63; Robert Asahina in the New Leader described Motes’s quest as the natural result of his mailing address, stating that the film depicted “the pathetic attempts” of Motes to “find some comfort in the empty universe of the small-town South.”64 Variety described the characters as “evangelistic off-shoots” and “overzealous religious preachers from the deep South” (the South mentioned is almost always “deep”) who “run the gamut from the dedicated to the false to the almost maniacally obsessed,”65 an idea reinforced by Howard Kissel’s remark that the characters are “all, in the great Southern tradition, obsessed.”66

Perhaps the clearest example of a critic’s assumptions about the South affecting his or her evaluation of the film was found in the New York Daily News, where Kathleen Carroll praised Huston for creating a South more like the one she imagined than the one described by O’Connor: “Huston has more than done his part by capturing just right the sleazy Southern atmosphere and recreating the novel’s Bible Belt setting. . . . Wise Blood presents a scathing vision of the South as a land of lost souls and religious addicts who are quick to latch on to anyone who even looks like a preacher.”67 However, according to O’Connor and her church, the land of lost souls extends far beyond the Mason-Dixon line, and the characters of Wise Blood are not so gullible: part of Motes’s frustration is that no one is quick to “latch on” to him besides his sole disciple, the idiot Enoch Emery. Wise Blood, both on paper and celluloid, is much less a scathing vision of a place than of a spiritual condition. But such larger thematic (and even dramatic) concerns were not as important to some critics as seeing exactly what they wanted to see in the film, as if the screen were a means of reflecting back their assumptions about the South and those who lived there. The critical attitudes here call to mind O’Connor’s remark, “Anything that comes out of the South is going to be called grotesque by the northern reader, unless it is grotesque, in which case it is going to be called realistic.”68 In the context of the reception of Huston’s film, her words ring prophetic, as critics frequently praised Huston’s “realism.” That Huston shot the film on location and filled minor roles with local, Macon players surely added to the “realism” for which he was praised, but the general tenor of the remarks about his vision of Taulkingham suggests that critics were eager to praise as “realism” anything that stroked their preconceptions.

Much of the specific praise Huston enjoyed had to do with the degree to which he had successfully appropriated O’Connor’s thematic concerns and artistic performance and how, in the words of one reviewer, “the essence of the book blazes from the film.”69 One delightful irony of the language lay in critics’ use of religiously charged language when discussing Huston’s artistry in bringing the story of a would-be atheist to the screen. Some spoke of Huston as having created “a remarkably faithful”70 adaptation of the novel, of the “reverent care”71 of Huston and his “reverent adaptation,”72 of the novel having been “translated with fidelity”73 by Benedict Fitzgerald, and of Huston’s having been “remarkably faithful”74 to O’Connor’s characters. Kathleen Carroll epitomized this trend of resorting to the language of God to articulate the work of man: “John Huston’s film interpretation of Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood must be considered something of a miracle.”75

But what does it mean to call an adaptation “faithful”—and what was so “miraculous” about Huston’s film in terms of how he appropriated O’Connor’s art for a moviegoing audience? What led many critics to concur with Rob Baker in the Soho News, who called the film so “wonderfully true to the spirit and vision of the writer” that “it should serve as a model for similar literary adaptations in the future”?76 And, ultimately, how did Huston’s film play upon O’Connor’s reputation at the time as well as suggest new directions it might take as a wider audience encountered Hazel Motes?

Part of the critical enthusiasm resulted from the generally low expectations that accompanied any attempt to adapt imaginative and original literature (as opposed to genre fiction) into film. In her essay included in the Criterion DVD edition of the film, former PEN American president Francine Prose articulates this general assumption about the broken bridges between the library and the movie-house:

Novelists learn not to expect too much when their books are made into movies. Obviously, great fiction has been turned into great cinema, but the dents and scrapes that so many classics have sustained on the rocky road from the page to the screen have convinced most writers that the odds of being purely thrilled by the movies made from their books are only slightly better than the odds of winning big in Las Vegas.77

Such an assumption helps explain the general enthusiasm for Huston’s film, an assumption reflected in the title of Vincent Canby’s second review: “Many Try, But Wise Blood Succeeds.”78 Specifically, however, the critical praise often had to do with matters relating to Huston’s own artistic habit of respecting his source material. In a 1984 interview, he called Wise Blood “a wonderful and fascinating book”; when complimented on the striking combination of styles and moods in the film, he replied, “That all comes from Flannery O’Connor. Many writers that we know are sometimes funny, sometimes awful, sometimes strange, but she could be all three at the same time.”79 Wise Blood worked on film because, despite their widely divergent views on spiritual matters, Huston and O’Connor both had—artistically—wise blood, and neither was afraid of presenting strange or unlikable characters in extremis, a technique that Huston would repeat in his next film, Under the Volcano. Huston honored the word of Wise Blood by never attempting to train it into a conventional film, unlike John Selby who had wanted to train it into a conventional novel. He could accept O’Connor’s work without needing to contain it—although his original ideas about Motes’s fate underwent a significant shift. Critics called Wise Blood “hardly your typical American movie,”80 “resembling no other movie that I can recall,”81 and “not neat by usual movie standards.”82 O’Connor’s unconventionality seemed perfectly suited to Huston’s own, and this element of her reputation was reflected in a Film Comment review by James McCourt, who called Huston’s Wise Blood “something like a re-creation of the real Flannery O’Connor’s famous unnatural two-headed chicken, with one real head and one made out of wax and stuck on with crazy glue.”83 The actual backward-walking chicken resurfaced as a mythical two-headed one and a means to account for both O’Connor’s and Huston’s unconventionality.

A few critics, however, argued that Huston was not O’Connoresque enough, as when David Sterrit in the Christian Science Monitor pointed to the folksy banjo music as an example of how Huston tried to deal in black comedy “but never [got] past light blue.”84 Others faulted what they saw as Huston’s short shrift to the character of Enoch Emery, whom Geoffrey Newell-Smith called “little more than a poor simpleton,”85 while Robert Asahina argued that the compression of Enoch Emery’s scenes in the film “unbalances the narrative.”86 Similarly, in Sight and Sound, Tim Pulleine argued that “the briefer treatment afforded [Emery] in the movie paradoxically lends his connection to the story a literary overtone.”87 But these complaints were exceptions to the general praise of Huston’s fidelity.

What might strike a reader as surprising in a discussion of how well Huston adapted O’Connor’s novel was that not every critic viewed fidelity to the written word as an occasion for praise. While critics such as Michael Tarantino in Film Quarterly called Wise Blood a success because Huston’s treatment of the novel met the “unique”88 demands of the cinema, Stanley Kauffmann expressed his amazement at the Fitzgeralds and Huston’s thinking that “honoring the word” would result in a successful adaptation: “They thought that (near) fidelity to the story and the dialogue would in itself recreate the book. It doesn’t, of course. What we get are the data of the book: a chamber of horrors and a mass of unexplained behavior.”89 Roger Angell praised Huston for capturing O’Connor’s idiom but faulted him for failing to overcome other challenges of adaptation: “I wish the Fitzgeralds had sometimes seen fit to invent more dialogue or some business of their own that would give the members of their extremely capable cast a chance to play together in a more useful, interpretive dramatic form, instead of pursuing their lonely lines of scam or vision in such perfect, cuckoo isolation.”90 But both Kauffmann and Angell seemed to be asking for what the film could not—perhaps should not—give: built-in Cliff’s Notes to make the characters’ actions more understandable or flesh out their weirdness into more recognizable characteristics. More recently, Jeffrey Meyers, in his 2011 biography, faulted Huston for even trying to bring Wise Blood to the screen: “He did a fair amount of work on the script and, ever faithful to the author, preferred to use her dialogue whenever possible and squeeze every word out of the text. But the final script was too unrelentingly faithful. . . . It succeeded in translating the bizarre and disturbing events of the novel into film, but its episodes of black comedy failed to lighten the bleak tone or mitigate the hero’s absurd tragedy.”91

This notion that a director can be too faithful to his source material—too devoted an acolyte—is one that still informs ways we think about issues of film adaptation. As Alan Yuhas recently stated in a Guardian piece about Baz Lurhmann’s 2013 adaptation of The Great Gatsby, “Countless BBC and PBS adaptations of Jane Austen and Charles Dickens have fallen into the trap of fidelity; they’re well acted, well produced and constantly remind you that you should be reading the original instead. These are literal translations, made leaden by detail—costumes, accents and affectations—full of footnotes for the scholars and superfans.”92 The director may thus seem damned if he does and damned if he doesn’t: including all of Enoch Emery’s scenes and actions would satisfy those who found his presence in the film too insubstantial, but doing so would have caused other critics to complain that the scenes detracted from the centrality of Motes’s struggles. The critical divide over the film is seen in representative examples: Harold Clurman thought that Huston’s film “corresponds to the nature of the writer’s work”93 while Andrew Sarris used the issue of Huston’s fidelity to O’Connor to offer what seems, at best, a tempered compliment: “Huston has been remarkably faithful to characters of such emotional, physical, and social grotesqueness that they would have made the old Hollywood moguls choke on their chicken soup and homilies. . . . [But] I am not sure that Flannery O’Connor’s vivid gargoyles belong on a movie screen.”94

Beside the debate over whether Huston’s fidelity was a triumph or liability lay the previously examined one about how different audiences responded to O’Connor’s work in general. Joy Gould Boyum argues that the director is less of an author than—crucially, for our purposes—a reader: “The simple fact is that an adaptation always includes not only a reference to the literary work on which it’s based, but also a reading of it—and a reading which will strike us as persuasive and apt or seem to us reductive, even false. And here, I think, we’ve come to the only meaningful way to speak of a film’s ‘fidelity’: in relation to the quality of its implicit interpretation of its source.”95 Huston’s “implicit interpretation” of O’Connor’s novel recalls the previous discussion of her two authorial audiences: the “genuine” readers who accepted the mysteries found in her work and the resistant “ironic” ones whom she imagined refuting the spiritual foundations of her fiction. How Huston read O’Connor and how critics responded to his reading of Wise Blood reflect the state of O’Connor’s reputation at this time as well as the ways in which these two audiences (who had debated the meaning of The Violent Bear It Away) were still at odds.

The scene in Huston’s film that marks the continuing and representative split between O’Connor’s genuine and ironic audiences is the climactic event of Motes’s blinding himself with quicklime. The genuine reading of such an event holds that Motes, like Oedipus, punishes himself for his figurative blindness by blinding himself literally and serves a penance for denying the existence of sin (with the prostitute Leora Watts and near-nymphet Sabbath Lily Hawks) by the mortification of his flesh. But the need for such atonement is beyond the grasp of his pragmatic landlady:

“Mr. Motes,” she said that day, when he was in her kitchen eating his dinner, “what do you walk on rocks for?”

“To pay,” he said in a harsh voice.

“Pay for what?”

“It don’t make any difference for what,” he said. “I’m paying.”

“But what have you got to show that you’re paying for?” she persisted.

“Mind your business,” he said rudely. “You can’t see.”96

Their conversation about Motes’s other form of penance (wrapping barbed wire around his torso) reveals the same opposing attitudes toward the need for redemption:

“What do you do it for?”

“I’m not clean,” he said.

She stood staring at him, unmindful of the broken dishes at her feet. “I know it,” she said after a minute, “you got blood on that night shirt and on the bed. You ought to get you a washwoman . . .”

“That’s not the kind of clean,” he said.

“There’s only one kind of clean, Mr. Motes,” she muttered.97

These exchanges push the reader toward a genuine reading of Motes’s penitential blindness, a reading that O’Connor spoke of in a letter to John Hawkes about how an understanding of the southern “do-it-yourself religion”98 helped explain why a man like Motes would engage in such shocking behavior:

There are some of us who have to pay for our faith every step of the way and who have to work out dramatically what it would be like without it and if being without it would be ultimately possible or not. I can’t allow any of my characters, in a novel anyway, to stop in some halfway position. This doubtless comes from a Catholic education and a Catholic sense of history—everything works toward it or away from it, everything is ultimately saved or lost. Haze is saved by virtue of having wise blood; it’s too wise for him to ultimately deny Christ. Wise blood has to be these people’s means of grace—they have no sacraments.99

O’Connor’s art in general reflects this position: characters such as Tarwater, Mrs. Turpin, and the grandmother in “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” experience the action of grace by nonsacramental means and ones equally as unsentimental and shocking as those experienced by Motes. Without sacraments or the Catholic Church, only their own wise blood can move them, however slowly or painfully in their “do-it-yourself” manner, toward salvation.

As members of the genuine authorial audience, many of Huston’s critics did read Motes’s blindness as an example of his attempt to achieve grace through his own do-it-himself means: Joy Gould Boyum noted in her review that “Haze succumbs to his Christian belief, paying penance for his heresy by committing frightening acts of self-martyrdom,”100 while David Denby told his readers that Motes “closely works his way to a pitiable but authentic martyrdom.”101 Other critics showed evidence of having consulted O’Connor’s works in order to inform their own understanding of the film. Jack Kroll, for example, echoed O’Connor’s ideas and phrasing when he stated, “Huston catches the craziness and violence that result when people who lust after grace and redemption have to create their own slapstick sacraments.”102 And David Ansen described Motes as a “Christian malgré lui,”103 the same term used by O’Connor in her note to the 1962 edition of the novel. More directly, Ansen called Motes’s self-blinding the “bloody and bizarre atonement” of “a tortured man stumbling ass-backward into salvation.”104 While O’Connor never used such a phrase, one cannot help thinking that she would have agreed.

However, other critics regarded Motes’s blindness and suffering ironically, recalling the same split between genuine and ironic audiences for The Violent Bear It Away, where some readers assumed, in a genuine authorial spirit, that Tarwater’s vocation was as plain as the marks on the page, while others, from an ironic stance, read the novel as an examination of a young man’s “brainwashing” by a “religious fanatic.” One such ironic reader, Tim Pulleine, in his enthusiastic review for Sight and Sound, described Motes as a man who endeavors to “keep alive his godlessness through (anti-) religious acts of purification,”105 as if Motes had blinded himself to illustrate the meaningless of existence and prove that he was willing to suffer for the sake of his Church Without Christ. (The novel and novelist both imply that he blinds himself for exactly the opposite reason—for decrying the truth of what he had so earnestly mocked, for playing St. Paul before his conversion on the road to Damascus.) In another enthusiastic and ironic British review, Geoffrey Nowell-Smith described Motes’s story as a “seemingly purposeless tragedy,”106 implying that Motes has learned nothing and has not experienced the grace which is so central to O’Connor’s art. As was the case with The Violent Bear It Away, however, an ironic reviewer could respond to O’Connor’s work in a way wholly antithetical to the spirit in which she intended and yet still find it worthy of praise, as many ironic-minded critics did. The same ironic reading appears in the London Observer, where Philip French states, “Eventually, in pursuit of total rejection, Motes blinds himself, practices mortification of the flesh with barbed wire, and attains a kind of sainthood.”107

Motes may attain a kind of sainthood, but not in pursuit of total rejection; his actions are motivated by his total acceptance of what he has spent so much time denying. As with works such as “The River” and The Violent Bear It Away, some critics could only approach the fate of the protagonist ironically, jeering at O’Connor’s issues and sometimes revealing their inability to imagine that she could take them as seriously and as literally as she did. Late in her Wall Street Journal review, Joy Gould Boyum offers what reads like a concession to her ironic colleagues: “In reproducing the book so closely, the film has also reproduced its ambiguities. We cannot be sure just what O’Connor through Huston is telling us here. Is she demonstrating the tenaciousness of belief? Or instead mocking its excesses? How are we to take Haze’s martyrdom—as religious distortion, or as embodying the possibility of redemption? As in the book, it’s nearly impossible to say.”108 Boyum is sharp about many aspects of O’Connor’s work and film adaptation in general, but here, she dances around the meaning of Motes’s self-blinding and mortification, describing them as “a grotesque mockery of the excesses of religious faith or as Haze’s way to salvation.”109 But it is not “impossible to say” what Motes’s blindness means or if his blindness suggests he is slouching toward salvation. If one regards Motes’s suffering as an occasion for mockery or self-congratulation for never having fallen prey to such “excesses,” one seems to have missed the meaning of the title, that Motes’s wise blood triumphs over his foolish mind. And while one could argue here that the title itself is ironic, doing so is akin to arguing that Tarwater’s vision at the end of The Violent Bear It Away is a psychotic hallucination. It is an interpretation that flatters, rather than challenges, the reader for siding with Rayber rather than with Mason, with Motes’s landlady rather than with her tenant. In a 2004 interview, Brad Dourif (who played Motes) stated, “He was insane,”110 just as some of the novel’s first reviewers, such as Isaac Rosenfeld, proposed: “Motes is just plain crazy.”111 But assuming Motes’s actions to be the result of insanity rather than grace—and thus approaching Wise Blood as an ironic reader—is akin to regarding Wise Blood as a work of satire; it is a way to reduce and contain the “terror” that Michael Fitzgerald noted distributors felt when they were asked to release the film. Roger Angell described Motes’s blindness as proof that “Jesus has caught him at last,”112 but to allow for such a reading, one must entertain the possibility that there is a Jesus from which Motes is running in the first place.

Such an allowance may seem obvious to O’Connor or her genuine authorial readers, but it was not so to others, who regarded the film’s climactic moment as an ironic, heavy-handed lesson. In a 2013 interview, Daniel Shor, who played Enoch Emery, articulated such an attitude toward the climax: “I see those characters as people who are seeking belonging. They are clinging onto an obvious illusion. Wise Blood was really Flannery O’Connor taking a piss out on evangelicalism of all kinds. Not [on] the people themselves but on the preachers. People need something to believe in, and they’ll believe in whatever the hell they’re told to believe in.”113 Shor is a brilliant actor but a less brilliant literary critic, and his remarks stand as yet another example of the impulse to turn O’Connor into a satirist: if Motes is clinging to an “obvious illusion” at the end for the sake of his own comfort, the viewer is therefore meant to take his potential redemption as a joke and the film as a whole as an elaborate snuff film. The characters themselves certainly do not “believe in whatever the hell they’re told to believe in”: Motes denies Christ, Hawks is motivated solely by self-interest, and neither of these rival preachers is able to win any converts other than the idiot Enoch Emery, who seeks companionship more than salvation. Shor assumes a secular agenda and satire where neither exists and speaks of Wise Blood as if it were akin to Elmer Gantry, a work that does attack “evangelicism of all kinds” and the people believing in “whatever the hell they’re told to believe in.” Like some of the critics who first reviewed O’Connor’s fiction, Shor and some film reviewers favored ironic readings of the film that offered some sense of superiority over O’Connor’s subject matter.

Huston himself began the project as an ironic reader but then found himself changing sides. In a 2004 interview, Brad Dourif said that Huston wanted to adapt the novel because it complemented the director’s own opinions: “He saw it as a nihilistic rebellion. He didn’t get that it was really an affirmation of Catholicism, of Christianity. Flannery O’Connor was Catholic as the day is long. . . . John was a devout atheist.”114 Dourif later remarked that Huston “felt it was about how ridiculous Christianity was”115 and also described a discussion between him and Huston that reflected the director’s being firmly encamped in the ironic audience:

He thought that, in the end, Hazel Motes had some kind of existential revelation. He was a devout atheist. I mean, he didn’t like religion. And I remember we were in rehearsal and I finally asked the question. I said, “Well, what do you think happens? Because it seems to me that the script is very clearly saying that Hazel Motes finds God and that’s what happened, and he dedicates his life to it.” And he said, “No, no, no, no, no.”116

Benedict Fitzgerald stated that Huston “thought it was a comedy” and that he, his brother, and his mother never attempted to “set right” Huston’s “misunderstandings” about the “religious heart” of the story,117 so pleased were they to have Huston at the helm and so confident that his style of directly presenting the narrative would allow O’Connor’s issues to surface. The screenwriter, however, also told the story of Huston’s experiencing a form of enlightenment, lesser than the one experienced by Motes, but important nonetheless: “I remember on the last day he put his hands over my shoulders and leaned in and said, ‘Ben, I think I’ve been had.’ And I didn’t know what he was talking about, but something rang true. . . . And by the end, he realized, ‘I’ve told another story than the one I thought I was telling. I’ve told Flannery O’Connor’s story.’”118 Huston’s begrudging shift from the ironic to the genuine audience, from denying what informs Motes’s suffering to acknowledging its presence, is witnessed even more dramatically in Dourif’s anecdote about a conversation among the producers and actors: “We’re all sitting around the table and Huston kind of looks up at everybody and he looks around and says, ‘Jesus wins.’”119

Huston was, in some sense, of O’Connor’s party without knowing it, an idea reinforced in Lawrence Grobel’s biography The Hustons, where he recounts the making of the film and comments, “Wise Blood was so strange, so offbeat, so insular, that John had his own hard time figuring out what it was about.”120 Wise Blood may have first been regarded by Huston and is undoubtedly still regarded by some critics as satirical or a mockery of the very values and truths that O’Connor sought to dramatize. Eventually, however, the director moved closer to the author, who argued in a letter, “What people don’t realize is how much religion costs. They think faith is a big electric blanket, when of course it is the cross.”121 Motes’s religious awakening does not result in platitudes about loving thy neighbor but in debasement and an acknowledgment of his own pride—a fate similar to the one experienced by Mr. Head in “The Artificial Nigger.” In his 2013 book Hard Sayings: The Rhetoric of Christian Orthodoxy in Late Modern Fiction, Thomas F. Haddox convincingly argues that Mr. Head’s pride is difficult for readers to regard as sinful because we “do not live in a culture in which pride prompts universal fear and loathing.”122 Perhaps this helps explain why some viewers had trouble with the end of Huston’s film: Motes admits his own pride as the source of his misery, but others may be slow to do the same.

William Walsh, writing in the Flannery O’Connor Bulletin, said that Huston’s epiphany of “Jesus wins” was simply the director “capitulating to the obvious,”123 but Huston, like Motes on a smaller scale, took a circuitous route to his insight. Jeffrey Meyers sneers at the film with remarks such as, “The whole Fitzgerald family genuflected at the altar of Saint Flannery . . . and the movie is a testament to their devotion.”124 But if Huston’s Wise Blood is a testament to anything, it is to ways in which O’Connor’s reputation had grown more complex since 1952 and was still being challenged by readers who regarded her work in very different ways. Much had changed: critics were, on the whole, more amenable to her issues and the ways that she explored them. But the ironic audience and those who could not get past the actors’ accents were still affecting how her work was received.

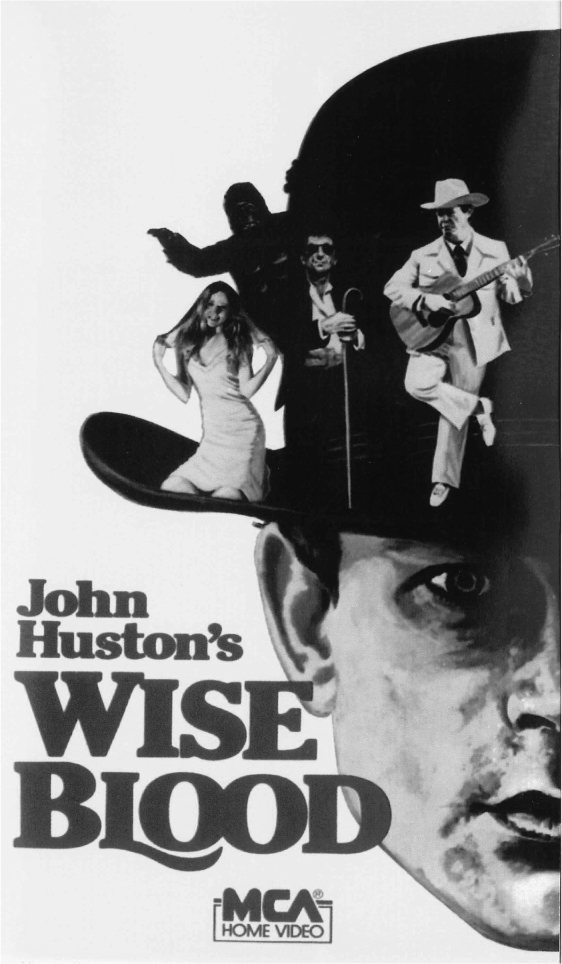

Elsewhere in this study, we have seen ways that publishers and their graphic designers attempted to package O’Connor’s books for public consumption. Those working in the New Line publicity department faced a similar challenge: how to market Wise Blood to an audience they correctly assumed would regard it as strange and not worth the price of a ticket. Their strategy was to sell Wise Blood as a comedy, something less like a work by Flannery O’Connor and more like one by Mark Twain. The film’s poster featured the phrase “An American Masterpiece!” prominently in its top corner, never hinting that the “America” in question here is the South. Indeed, nothing in the poster, except perhaps the small image of Ned Beatty as the guitar-strumming Hoover Shoates, suggests that the film takes place in a fictional Tennessee town. While one blurb calls the film “A brilliant black comedy,” the image of the four supporting characters (including Enoch Emery in his gorilla suit) standing on the brim of Motes’s hat, combined with blurbs calling the film “An uproarious tale” and “wildly comic,” suggest that Wise Blood is wacky instead of disturbing, a straightforward comedy rather than one that elicits nervous laughs from a growing sense of unease. The phrase “Based on the novel by Flannery O’Connor” in small type underneath the title reflects New Line’s desire to promote the film to a literary audience as well as to a cinematic one. What happened with the covers of Wise Blood also happened with the artwork for its cinematic adaptation: a look at the artwork for the original home video release, which used the same graphic as the theatrical poster (fig. 14), and that of the 2009 DVD (fig. 15) reveals the similar shift in advertising O’Connor’s themes.

The film’s trailer reflected a desire to recast O’Connor as more humorist than moralist. Beginning with Motes saying, “I ain’t no preacher” to a cabdriver, the trailer begins with an announcer advising uninitiated viewers about how to regard the issues of the film:

In a world of sin and seduction, there’s a lot of ways of getting saved. Some do it with style. Some have other plans. What Hazel Motes wants is a good car and a fast woman. What he gets is the last thing he wanted. Wise Blood. The New York Times calls it “an uproarious tale, one of John Huston’s most stunning movies.” Wise Blood. Some got it, some sell it, and some give it away. A new film by John Huston. Wise Blood. From the acclaimed novel by Flannery O’Connor.125

This voiceover description of the film is intercut with shots and bits of dialogue edited to suggest that Wise Blood is more of a lighthearted romp filled with country bumpkins than a disturbing reimagining of the story of St. Paul. The viewer sees Motes nearly hit in the face with the hood of his car, Enoch Emery shaking hands with Gonga the gorilla, the obese Leora Watts cracking, “Mama don’t mind if you ain’t a preacher—as long as you got four dollars,” and the film’s one obvious laugh line and certainly the one that led some critics to assume that O’Connor was a satirist:

MOTES: I started my own church. The Church of Truth Without Christ.

LANDLADY: Protestant? Or something foreign?

MOTES: Oh, no, ma’am. It’s Protestant.126

Figure 14. Wise Blood, film ad.

Figure 15. Wise Blood, DVD cover.

All these clips are accompanied by jaunty, high-spirited, southern music. The trailer’s total effect is greatly different from that of the film, and the viewer who has seen both might be reminded of Robert Ryang’s 2006 “trailer” for Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining that recut scenes from the film and added a new voice-over to make it appear like a family-friendly comedy.127 In short, the viewer of the trailer for Wise Blood is invited to laugh at the characters and feel superior to them, an antithetical effect to O’Connor’s practice of shouting to the hard of hearing and drawing large and startling figures. Nothing in the trailer or poster even hints that the film contains a murder, a mock Virgin Mary, or a man who blinds and mutilates himself. These parts of the film had to be downplayed if viewers were to fill theaters; only then would the distributors’ “terror” be lessened. The desire to package Huston’s adaptation of O’Connor’s novel into more palatable and audience-friendly fare was noted by Vincent Canby, who later commented on his initial review by confessing that his enthusiasm colored the way he described it: “It wasn’t until I saw the film a second time the other day that I realized that by calling it ‘comic,’ ‘uproarious’ and ‘rollicking,’ among other things, I had probably misled movie audiences for whom those words are more often associated with Mel Brooks than with a tale about the furious soul-searchings of a young redneck Southerner named Hazel Motes.”128

Of course, such a description was easier for Canby to give than for New Line Cinema. A spiritual dark comedy was not going to sell tickets. One of the reviewers of the novel remarked, “The author calls this ‘a comic novel.’ It’s funny like a case of cancer.”129 New Line Cinema had to sell that case in a package that audiences could easily identify: the misadventures of buffoonish hillbillies, a package with a history that began long before the dawn of Hollywood. A major film that had previously capitalized on the image of southerners as regressive and subhuman—John Boorman’s Deliverance (1972)—had proven, by its commercial and critical success, that such images were taken as fact by broad swaths of moviegoers. “Indisputably the most influential film of the modern era in shaping national perceptions of southern mountaineers,”130 Boorman’s film, while taking place in the wilderness and stylistically far from a dark comedy, could not have been far from viewers’ minds as they watched Wise Blood.

The reception of Huston’s Wise Blood, like that of the novel and O’Connor’s other work, has proven to enact the previously examined duel between self-congratulating readers who assumed that any work examining religion in the South must be ironic and those whose sympathy for O’Connor’s issues—or at least the ability to entertain them—allowed for more genuine readings. The duel continues today. When the film was remastered as part of the Criterion DVD Collection in 2009, a reviewer for the Los Angeles Times accurately described Motes as “a fanatic nonbeliever”—a wholly genuine reading—but also raised the possibility of looking at Motes from an ironic vantage point: “But is he a holy fool or just a pathetically deluded one? The religious inclinations of the viewer will determine whether his eventual fate reads as salvation or as tragedy.”131 The “religious inclinations” of the viewer, however, are not as important as the viewer’s ability to entertain the idea that O’Connor saw great meaning in Motes’s suffering—as she surely did.

Despite the distributor’s efforts and the enthusiasm of several important reviewers, Wise Blood was not as big a box-office success as some of Huston’s other films.132 Perhaps O’Connor’s characters proved too strange, too possessed, or too “southern” for mass consumption. In his autobiography, Huston acknowledged the film’s financial failure but did so in a way that recalls the articles and reviews that fretted over O’Connor’s lack of commercial appeal while recasting this lack of appeal as a mark of artistic integrity: “Nothing would make me happier,” he wrote, “than to see this picture gain popular acceptance and turn a profit. It would prove something, I’m not sure what . . . but something.”133 What it would perhaps prove was that O’Connor was ready to be accepted by the great movie-watching public when translated by a master into a medium that commonly avoided taking spiritual issues as seriously and as earnestly as she did.

While Wise Blood was certainly the most widely reviewed adaptation of O’Connor’s work—and the one that best reflected the complexities of her reputation at the time of its premiere—it was not the only attempt to translate her fiction into another artistic medium. Other adaptations, both before and after Huston’s film, reveal similar impulses to bring O’Connor to different audiences and ways in which she was regarded at the time. In 1963 Cecil Dawkins, then a writer of short stories, wrote O’Connor to pitch the idea of using her work as the basis for a play. The two had been regular correspondents since 1957, when Dawkins first wrote to ask her opinions on literature. Regarding the play, O’Connor replied, “I think it’s a fine idea if you want to try it,”134 and expressed more concern over her remuneration than her reputation: “I would not be too squeamish about anything you did to this because I have no interest in the theater for its own sake and all I would care about would be what money, if any, could be got out of it. It’s nice to have something you can be completely crass about.”135 However, despite her suggestion that she would keep her hands off Dawkins’s work, O’Connor did note one aspect of her own reputation that she hoped Dawkins would keep in mind:

Did you ever consider Wise Blood as a possibility for dramatizing? If the times were different, I would suggest that, but I think it would just be taken for the supergrotesque sub–Carson McCullers sort of thing that I couldn’t stand the sound or sight of. . . . The only thing I would positively object to would be to somebody turning one of my colored idiots into a hero. Don’t let any fool director work that on you. I wouldn’t trust any of that bunch farther than I could hurl them. I guess I wouldn’t want a Yankee doing this, money or no money.136

O’Connor knew how she was regarded and feared that a “Yankee” might attempt to refashion her work so it reflected a more northern sensibility, and while a reader today may cringe at her wish for none of her “colored idiots” to be recast as heroes, the larger point remains: O’Connor had read enough reviews of The Violent Bear It Away three years earlier to know that many readers who did not share her assumptions were eager to tell her work what it meant, instead of vice versa. But she trusted Dawkins and gave her carte blanche.

Dawkins eventually drafted what would become The Displaced Person, a play based on several of O’Connor’s stories, and hoped to gain her approval, but O’Connor’s death in 1964 led Dawkins to shelve the project. In 1965, however, the artistic director of the American Place Theatre asked Dawkins if she were interested in producing the play. The American Place seemed well suited for Dawkins’s work: its first production, Robert Lowell’s The Old Glory (1964), brilliantly adapted works by Melville and Hawthorne, and the theater was forging its own reputation as a space for (according to its publicity department) “American writers of stature”137—a reputation it still has today. The theater did its part in drumming up interest among its 4,500 members, informing them that the play’s director, Edward Parone, had recently helmed LeRoi Jones’s Dutchman and was therefore up to the task of creating a memorable production of a controversial work. Dawkins also wrote a three-column piece that ran in the New York World Journal Tribune four days before the play’s opening date of December 29, 1966, in which she presented her opinions of O’Connor and addressed the author’s current reputation. Dawkins recast O’Connor’s south-ernness—what O’Connor feared would lead directors into creating a “supergrotesque sub–Carson McCullers sort of thing”—as something akin to the net of nationalism over which, in Joyce’s novel, the young Stephen Dedalus seeks to fly: “Flannery O’Connor,” she wrote, “better than any other Southern writer, escaped regionalism. And she did so by escaping the attitude of the region toward itself. Every region has such an attitude. In the South, it is a certain romanticism toward things Southern. An eye such as Flannery O’Connor’s is the eye of a naturalist. Like Audubon, she knew her birds.”138 As Robert Giroux would seek to make O’Connor more American than southern in his 1971 introduction to The Complete Stories, Dawkins here and throughout her essay asked readers to forget what they thought they knew about O’Connor as a southern author and instead to appreciate the “clear-sightedness” that allowed her to measure “things-as-they-are against ultimate values.”139 Dawkins also claimed that the “sophistication” of New York audiences presented the “danger” that works of art became occasion for “an intellectual opinion mill,” and that in the big city “performers play to severed heads, to eyes and noses in some direct contact with the brain requiring no nervous system, no spinal column, no body, no blood, no heart.”140 She hoped that The Displaced Person would invite intellectual New Yorkers to admire the force of O’Connor’s unsentimental work and appreciate how she wrestled with the problem of evil.

They did not. Reviewers were unanimous in their complaints about the play’s disjointedness, which, they argued, preserved O’Connor’s figures and settings but not the emotional weight that Dawkins thought she was urging her New York audiences to accept—the same complaint voiced by Stanley Kauffmann against Huston for offering only the “data” of Wise Blood. In The Village Voice, Michael Smith stated, “Many of the individual characters are solid and interesting, but the incidents are oddly vague, incomplete, disconnected.”141 In Newsweek, Richard Gilman wrote, “The stage is full of fragments” of O’Connor’s “unique sensibility, an amalgam of dark humor and unavoidable violence, but there is no dramatic shape or growth to the enterprise.”142 And George Oppenheimer in Newsday complained that the actors seemed to be walking “into a series of separate playlets, held together but not firmly enough by a central character.”143 Oppenheimer also called the play “too faithful to Miss O’Connor,”144 which recalled similar critical complaints about Huston’s Wise Blood. Dawkins’s being an O’Connor insider could not guarantee the success of her adaptation. Even the enthusiastic Robert Giroux wrote to Robert Fitzgerald that both he and Elizabeth Hardwick saw and enjoyed the play, but that “most of the audience thought it was another version of Tobacco Road.”145 Perhaps Dawkins’s play was caviar to the general, but (as was the case with Huston’s film) the general affected how the work was received.

In 2001 Karin Coonrod, who had founded in New York two theatrical companies devoted to reimagining the classics and staging works taken from non-dramatic authors, mounted a production titled Everything That Rises Must Converge with the New York Theatre Workshop. The play staged three stories: “A View of the Woods,” “Greenleaf,” and “Everything That Rises Must Converge,” with eight actors playing all the roles. Unlike The Displaced Person, however, this adaptation featured every word of each story: actors played not only the characters but the omniscient narrators as well. Coonrod’s being granted permission to use the works on the condition that she not alter a single word and ensure every sentence from each story being heard aloud forced her to adapt and present the stories in their entirety,146 a challenge for an adapter but one that surely allowed Coonrod to “honor the word” with her creative staging. Her director’s note to the viewer reinforces O’Connor’s reputation for combining horror and humor: “Flannery O’Connor’s apocalyptic comedies are peopled with characters whose reality resided in their obstinate wills. They drive themselves at every step deeper and deeper into their own desires, obsessions, disillusionments.”147 Coonrod also mentioned O’Connor’s narrative voice, noting its tendency to “mock and celebrate and question the characters, attending their every action with a kind of raucous glee.”148 Such a description stands in contrast to many responses by O’Connor’s first readers, who often sought to pigeonhole her at either extreme of mocking or extolling her characters; Coonrod’s description suggests a more complex understanding of O’Connor’s method of presenting her characters objectively in many different, often contradictory, lights. Finally, Coonrod’s description illuminates reasons behind her choice of stories, since all three feature characters who initially are detestable yet become objects of surprising sympathy. In short, Coonrod understood “how O’Connor works” and sought to replicate on stage the experience of reading O’Connor.

Everything That Rises Must Converge fared much better with critics than The Displaced Person. It also fared better with audiences, selling out its month-long run.149 Noting that the production was less “adaptation” than creative staging, Bruce Weber in the New York Times called the play a “carefully balanced literary mutation” and—unlike Dawkins’s play—“something deftly sewn” together from O’Connor’s stories.150 David Cote, theater editor for Time Out New York, similarly noted that Coonrod avoided the “literary-adaptation trap” by simply “not adapting.” Cote used the phrase “dark, unsettling magic” to describe how the staging of the title story “makes us actually pity this horrible creature,” Julian’s mother, who “finds the new South has no place for her genteel condescension,”151 again attesting to Coonrod’s effective approach of jarring the viewer into unexpected sympathy—a technique that O’Connor used throughout her career. In the Village Voice, Jessica Winter described the production as an open book whose “pages brim with colorful illustrations.” But she also could not resist a tired series of jabs, describing the setting as the “freak-tent medievalist South” and the deaths of the protagonists “swift, near-Falwellian acts of divine justice,”152 a phrase that both trivializes and misreads the significance of each story’s ending. Coonrod’s adaptation was revived in 2014–15, when it played at a number of high-profile universities (Emory, Georgetown, Loyola, Yale) and the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. Her efforts suggest that the best way to translate O’Connor for an audience might be to let the author speak for herself—or, in the case of other adapters, sing for herself: a musical of Wise Blood premiered in 2011 at the Off Broadway Theater at Yale University, and an opera version was staged at Minneapolis’s Soap Factory gallery in 2015. Bryan Beaumont Hayes, a Benedictine monk and former student of Aaron Copland, composed Parker’s Back: An Opera in Two Acts, but it remains unproduced.

O’Connor herself thought very little—in both senses of the phrase—of her works being adapted as a means to reach a wider audience or to examine her chosen themes in different media. Her first and only television appearance was in 1955, when she appeared as a guest on Galley Proof, an NBC series designed to appeal to a middlebrow audience and hosted by Harvey Briet, assistant editor of the New York Times Book Review. The show combined interviews of authors with dramatizations of their work; its motto, voiced by Briet in the opening minutes, was “Television is a friend, and not an enemy” to books.153 O’Connor’s appearance coincided with the publication of A Good Man Is Hard to Find, and Briet used the occasion to ask O’Connor about her status as a southern author:

BRIET: Do you think . . . that a Northerner, for example, reading [Wise Blood] would have as much appreciation of the people in your book, your stories, as a Southerner?

O’CONNOR: Yes, I think perhaps more, because he at least wouldn’t be distracted by the Southern thinking that this was a novel about the South, or a story about the South, which it is not.

BRIET: You don’t feel that it is?

O’CONNOR: No.154

Briet changed tactics immediately after O’Connor’s “No,” saying, “I don’t either,” but his line of questioning clearly played upon O’Connor’s status as a geographical outsider, and O’Connor resisted his attempts to pigeonhole her. Later that year, Briet reported, “She doesn’t think of herself as a Southern writer,”155 offering this tidbit as if it were news—which, to Briet and many of his readers, it was. Significantly, her Catholicism was never mentioned, which seems odd in a discussion of Wise Blood and which shows that O’Connor’s faith was not yet the automatic part of her reputation that modern readers take for granted.

After a few minutes, Briet segued to a dramatization of “The Life You Save May Be Your Own” and, by way of an innocuous question, inadvertently gave O’Connor the opportunity to state one of her core beliefs about her art:

BRIET: It isn’t over. What we’re seeing now is only part of the story. Flannery, would you like to tell our audience what happens in that story?

O’CONNOR: No, I certainly would not. I don’t think you can paraphrase a story like that. I think there’s only one way to tell it and that’s the way it is told in the story.156

O’Connor found adaptation a losing proposition from the start. All the energy devoted to “fidelity” was never enough; in fact, it was the wrong kind of energy. Even paraphrasing a story or “telling what happens”—itself a kind of adaptation—was futile. As O’Connor remarked elsewhere, “When you can state the theme of a story, when you can separate it from the story itself, then you can be sure the story is not a very good one.”157 The same holds true for a film or other adaptation—but such a line of reasoning was not to be used on Briet, who, as Galley Proof continued, spoke more than the ostensible subject of his interview.

O’Connor deprecated her experience on Galley Proof in letters to her friends, stating, “I am sure the only people who look at TV at 1:30 p.m. are children who are not financially able to buy A Good Man Is Hard to Find”158 and, “I keep having a mental picture of my glacial glare being sent out over the nation onto millions of children who are waiting impatiently for The Batman to come on.”159 She summarized the experience as “mildly ghastly.”160 Two years later, however, O’Connor sold the rights to “The Life You Save May Be Your Own” to Revue Productions for use as an episode of Schlitz Playhouse, one of many television dramas that offered adaptations of literary works to its audience. Her motives here were purely financial: in her letters, she said, “It certainly is a painless way to make money”161 and spoke with enthusiasm of the appliance that selling her story allowed her to buy for herself and her mother: “While they make hash out of my story, she and me will make ice in the new refrigerator.”162 When O’Connor heard that Gene Kelly would be making his television debut as Mr. Shiftlet, she wrote the Fitzgeralds, “The punishment always fits the crime. They must be making a musical out of it.”163 Upon learning (from a New York gossip column) that Kelly would be starring in what the columnist called a “backwoods love story,” she wrote Betty Hester, “It will probably be appropriate to smoke a corncob pipe while watching this.”164 O’Connor knew all too well how her story would be repackaged and sold as a small-screen version of Tobacco Road.

The episode aired on CBS on March 1, 1957, and also starred Agnes Moorehead as the elder Lucynell Crater and Janice Rule as her deaf daughter. O’Connor’s reputation in Milledgeville skyrocketed: she wrote Betty Hester, “The local city fathers think I am a credit now to the community. One old lady said, ‘That was a play that really made me think!’ I didn’t ask her what.”165 Similarly, she wrote Denver Lindley of the “enthusiastic congratulations from the local citizens,” who “feel that I have arrived at last.”166 O’Connor detested the adaptation and knew that the ladies of Milledgeville enjoyed it because the ending had been changed to one more formulaic: in the Schlitz Playhouse version, Mr. Shiftlet does not abandon his new bride in a roadside diner, but instead drives off with her into the sunset. O’Connor felt that anyone who enjoyed the television play had not read the story and stated, “The best I can say for it is that conceivably it could have been worse. Just conceivably.”167 Kelly described the show as “kind of a hillbilly thing in which I play a guy who befriends a deaf-mute girl in the hills of Kentucky”; when O’Connor shared this description with her friends Brainard and Frances Cheney, she underlined “befriends” to signal her outrage at the adaptation.168 A short review in the New York Times called the episode “an odd little drama” and described it in language that, in hindsight, suits many of O’Connor’s works: “The peculiarity of the film, ‘The Life You Save,’ stemmed from the extremes it reached during the half hour. For considerable periods it was ludicrous, almost like a caricature. At other moments, it was touching.”169 In “Writing Short Stories,” O’Connor tells of “The Life You Save May Be Your Own” and says this about the Schlitz Playhouse:

Not long ago that story was adapted for a television play, and the adapter, knowing his business, had the tramp have a change of heart and go back and pick up the idiot daughter and the two of them ride away, grinning madly. My aunt believes that the story is complete at last, but I have other sentiments about it—which are not suitable for public utterance. When you write a story, there will always be people who refuse to read the story you have written.170

O’Connor’s final sentence here could very well describe so much of the reception of her work from her first publication to Huston’s adaptation of Wise Blood: some reviewers refused to read how seriously she addressed grace, sin, and redemption, just as Huston had refused—at first—to read Wise Blood as something other than a satire.