On November 3, 2014, the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in upper Manhattan held “A Celebration of Flannery O’Connor,” an evening of speakers and performances to commemorate O’Connor’s induction into the American Poets Corner, a quiet and dignified niche located off the center aisle. O’Connor had, yet again, “arrived.” This unconventional author whose work many readers had once tried to pigeonhole as “southern gothic” was being installed in one of the most august and formal halls of fame, her name literally written in stone and joining the likes of Twain, James, and Faulkner. But the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine is also a very cosmopolitan place: on the night of the celebration, beautiful and enormous steel birds created by the Chinese artist Xu Bing hung from the ceiling, and guests were greeted by the sound of classical guitar as they walked to the altar. New Yorkers—the hippest of the hip—were gathering to reconfirm Giroux’s assertion that O’Connor was more American than southern, the scope of her work more universal than local.

As I mounted the steps, I found myself walking next to another person entering the cathedral. I asked her if she were attending the O’Connor celebration. “No,” she said. “I just wanted to go in and have a moment.” She asked me why I was there and I told her about O’Connor’s induction into the American Poets Corner. Her response—“Flannery O’Connor, the author?”—confirmed the writer’s name as a household word. Before the event began, I mingled with some of the guests and organizers, one of whom introduced me to Wally Lamb, who told me that he, like so many others, had been introduced to O’Connor by “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” and, like so many of us, became a lifelong admirer. “That was the one that did it for me,” he said. I spoke to the poet Alfred Corn, who, as a student at Emory, corresponded with O’Connor about weighty issues two years before she died. He told me, “She was honest with me because she didn’t know me or have to put on that ‘southern thing,’” an interesting observation; O’Connor was always conscious of her reputation and, at times, played to it. Marilyn Nelson, the cathedral’s poet in residence that year, told me that there was, naturally, some debate over who would be installed for 2014, but that the subsequent debate over the quotation carved into the stone under O’Connor’s name was much more spirited and protracted, a description later confirmed for me by another of the electors. With a smile, Nelson said, “But we prevailed” in their choice of inscription.

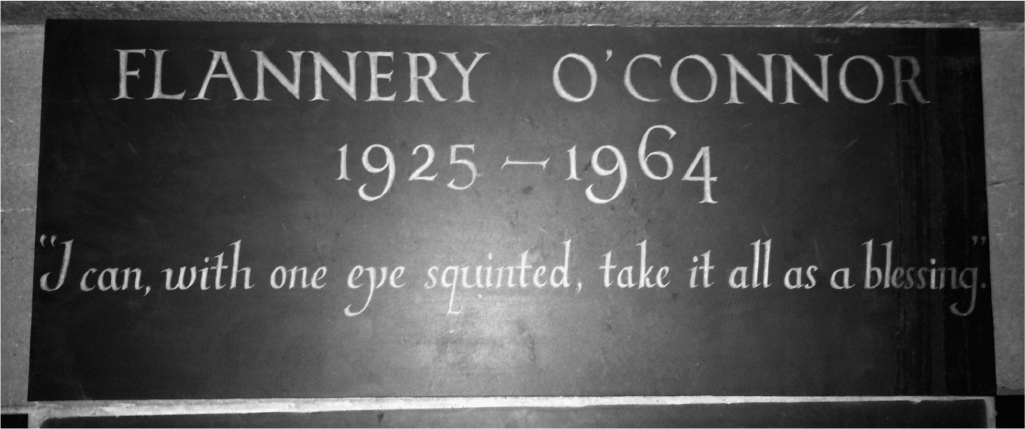

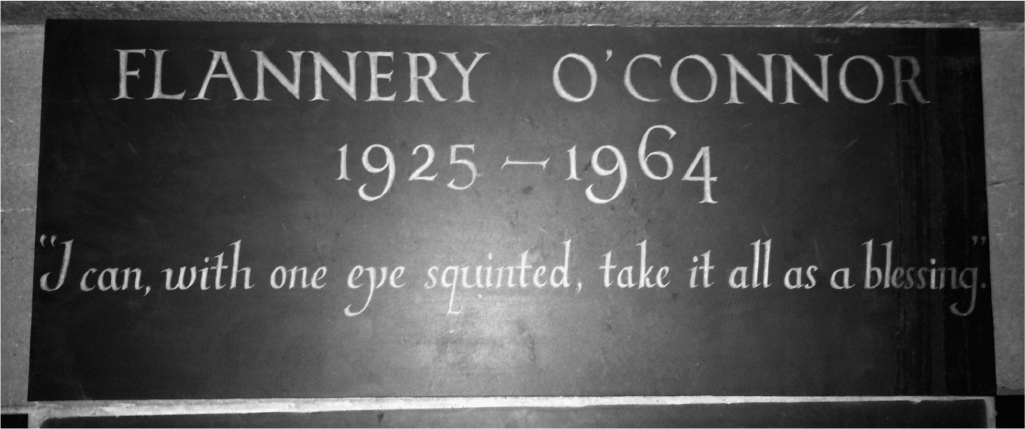

The inscription, carved underneath O’Connor’s name and dates, reads: “I can, with one eye squinted, take it all as a blessing” (fig. 16).1 The statement comes from a 1953 letter to Elizabeth and Robert Lowell in which O’Connor describes her lupus. At first, one might assume that the disease has defined the author and become inexorably linked to her reputation. This much is true, for the quotation reflects, in a perfectly ironic tone, O’Connor’s attitude expressed elsewhere that “Sickness before death is a very appropriate thing and I think those who don’t have it miss one of God’s mercies.”2 To leave out O’Connor’s bravery would be to give only part of the picture. But the quotation reflects O’Connor’s larger attitude toward life in general and how, in the words of her most famous creation, “Jesus thown everything off balance.”3 What may not seem to be a heavenly gift can be seen as such if one looks at it the right way—and one such way is through the lens of O’Connor’s fiction.

By the time the event began, about 150 people were seated at the front of the cathedral, including Louise Florencourt, O’Connor’s first cousin. One of the featured speakers, Reverend George Piggford, C.S.C., emphasized O’Connor’s devotion to the Eucharist and to the work of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. According to Piggford, the Jesuit author’s reputation mirrored O’Connor’s: his work was met by some with “anxiety and confusion,” so much so that, in 1962, Rome issued a warning about “doctrinal ambiguities in his work.” The Vatican never took such a stance toward O’Connor; indeed, O’Connor complained early in her career of her “silent reception by Catholics.”4 Piggford clearly implied, however, that both visionaries initially upset their readers’ assumptions about the foundations of their faith.

Alfred Corn spoke of his correspondence with O’Connor and prefaced his remarks with one of O’Connor’s statements about her own celebrity, which she called “a comic distinction shared with Roy Rogers’s horse and Miss Watermelon of 1955.”5 While recounting his first meeting O’Connor when she lectured at Emory, Corn addressed the ever-present issue of O’Connor’s depictions of the South: “The truth is that reality is often grotesque nor is reality any single region’s monopoly. If O’Connor deals with characters whose speech, dress, manner, and stated aims are bizarre, and whose actions are typically outrageous and violent, it is all in the interest of truth on the deepest level as she perceived it.” Corn’s remarks here recall what O’Connor told the interviewer for Galley Proof: “A serious novelist is in pursuit of reality. And of course when you’re a Southerner and in pursuit of reality, the reality you come up with is going to have a Southern accent, but that’s just an accent; it’s not the essence of what you’re trying to do.”6 The literary world seemed to have caught up to what O’Connor had been urging about her work all along.

Figure 16. O’Connor’s stone in Poets Corner.

Next came a performance of Everything That Rises Must Converge by the Compagnia de Colombari, Karin Coonrod’s company that first performed their adaptation in 2001. The audience enjoyed watching Julian’s slow burn at his mother’s antiquated assumptions about race. Next, Professor James O. Tate, who grew up in Milledgeville, noted the justice of O’Connor’s name being placed among others whom she so admired, such as Hawthorne and James. Tate’s talk was the most literary of the evening, linking O’Connor to Wyndham Lewis and explaining why O’Connor did not identify Martin Heidegger as the author of the “gibberish” Hulga reads in “Good Country People.” The celebration concluded with an address by Marilyn Nelson, who first spoke of Regina and stated that “the world owes her a debt of thanks” for the role she played in her daughter’s life. Nelson, an African American, described a time when she visited Milledgeville to give a reading at Georgia College and State University and stayed at the former governor’s mansion, a place where she did not feel alone: “I lay awake a long time with the distinct sense that former residents of the mansion were groaning, if not rolling in their graves because of my presence there.” She also spoke of Alice Walker’s admiration for O’Connor and the pilgrimage Walker made to Andalusia. So much had changed in the life of the South, but the truths that O’Connor sought to convey in her work had remained constant. Nelson spoke of O’Connor as one who, with a “gimlet eye,” saw that, as she stated in a 1958 letter, “Human nature is so faulty that it can resist any amount of grace and most of the time it does.”7 The audience chuckled at this quotation, which so perfectly reflects the way that human nature is portrayed in O’Connor’s art, as they did with Nelson’s subsequent quotations about O’Connor’s only diversion during her hospital stays as “disliking the nurses.”8 But Nelson returned to the importance of O’Connor the artist: “She could not stop herself from seeing us as we are, as we truly are,” Nelson urged, “yet she could not stop herself from believing that beyond our miserable, warped, shallow, and otherwise limited understanding is a vast and endless divine love.” Nelson concluded by reading the end of The Violent Bear it Away aloud; the description of Tarwater moving to the city, where the “children of God lay sleeping,” silenced everyone there—including the woman I saw as I entered, who had joined the assembly and was, like everyone else, “having a moment” with O’Connor.

Readers continue to have such moments. In 2013 A Prayer Journal, a collection that O’Connor wrote while at the University of Iowa, was published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Like other volumes of O’Connor’s work, the Prayer Journal is introduced by an O’Connor insider: in this case, William A. Sessions, one of her friends and correspondents who discovered the collection while working on her authorized biography. Unlike his predecessors, Sessions has little to prove; because of the work of people like Robert Fitzgerald and Robert Giroux, he does not need to assert O’Connor’s importance or the value of the text. His introduction is a short, graceful description of the prayers and how they reveal that O’Connor’s time in Iowa, a place of “new influences, including intellectual joys,” brought “questions and skepticism.”9 Reviewers found this skepticism a surprising corrective to O’Connor’s reputation as an oracle whose writing and thinking were, in the words of Ralph C. Wood, “straightforward as a gunshot.”10 For example, Lindsay Gellman, writing in the Wall Street Journal, stated that readers “might be caught off-guard at the vulnerability, and at times, despair, that also radiates from these pages.”11 Maryann Ryan, in Slate, stated, “Instead of the cocksure writer we’ve long known—whose confidence is almost a physical force in her mature fiction and essays on religion and art—here we glimpse an unfinished personality, struggling to maintain belief in her talent.”12 Hilton Als, who had previously written about O’Connor in White Girls, remarked that the journal was “unintentionally revealing” of a writer whose image to many readers contrasted the one in these pages.13 Patrick Samway, in the Flannery O’Connor Review, praised the volume as an “unpretentious cri de coeur,”14 while a reviewer for the Michigan Daily used less refined but equally perceptive language in describing it as “a jewelry box for her artistic anxieties.”15

But if reviewers were surprised by O’Connor’s youthful insecurities and learning that this literary giant and (as the Atlantic called her) “turbocharged Catholic”16 was sometimes beset by common doubts, they were affirmed in their collective estimation of her talent and the notion that talent such as hers would be obvious from a young age. In his introduction, Sessions states that the prayers reveal “a craftswoman of the first order” (viii), and critics concurred, often finding in the Journal premonitions of the career to come, as Joyce did in the opening pages of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Writing in the Georgia Review, Sarah Gordon observed, “The frequent conjunction of ideas concerning pain and grace certainly forecasts O’Connor’s fictional subject matter.”17 Patrick Reardon, in the Chicago Tribune, stated that the Journal reveals the young O’Connor to be “truly a writer,”18 while Carlene Bauer, author of Frances and Bernard, described the voice of O’Connor’s prayers as “utterly her own” and stated that “No one else could have written them.”19 And in a wonderful example of the-last-shall-be-first and the-first-shall-be-last, the New Yorker, which had so often dismissed O’Connor’s work when first published, offered an enthusiastic review that declared O’Connor’s preeminence:

O’Connor found the same way through cliché to invention in her spirituality and in her writing. How else could the tired old stories of tenant farmers, street prophets, ne’er-do-well teen-agers, agrarian widows, travelling bible salesmen, and murderous misfits become such celebrated works of fiction? Every believer finds a way to speak to God, but O’Connor also found a way to speak to everyone else.20

Readers who use Goodreads concur: slightly more than two years after its publication, the Prayer Journal has a 4.08 out of 5 rating, based on the opinions of over 1,200 reviewers.21

To conclude this history of O’Connor’s reputation and reception by critics, editors, creative artists, academics, and common readers, we can turn to a moment in one of O’Connor’s own works. An early scene in The Violent Bear It Away depicts Mason Tarwater’s discovery that his nephew, Rayber, had invited him to live in his house under false pretenses: “He had lived for three months in the nephew’s house on what he had thought at the time was Charity but what he said he had found out was not Charity or anything like it.”22 Rayber, Mason learns, was actually using his uncle as the unknowing subject of a psychological case study into what O’Connor’s critics might term “religious fanaticism.” After Rayber hands his uncle a copy of the magazine in which he published his study, Mason sits at his nephew’s kitchen table and reads the article until he understands its true subject:

When the old man looked up, the schoolteacher smiled. It was a very slight smile, the slightest that would do for any occasion. The old man knew from the smile who it was he had been reading about.

For the length of a minute, he could not move. He felt that he was tied hand and foot inside the schoolteacher’s head, a space as bare and neat as the cell in the asylum, and was shrinking, drying up to fit it. His eyeballs swerved from side to side as if he were pinned in a straight jacket again. Jonah, Ezekiel, Daniel, he was at that moment all of them—the swallowed, the lowered, the enclosed. (75–76)

After previous attempts to literally confine Mason in an asylum proved unsuccessful, Rayber has now attempted to place his uncle in another kind of cell. It is a subject against which the old man rails for the rest of his days. “Where he wanted me,” he later tells Tarwater, “was inside that schoolteacher magazine. He thought that once he got me in there, I’d be as good as inside his head and be done for and that would be that, that would be the end of it” (20). Mason’s insight is perfect: Rayber, the expert on testing at the school where he works, derides the existence of anything he cannot quantify and has dedicated his life, like Hazel Motes, to resisting the urgings of his own wise blood. He can only deride what he is not strong enough to deny. Even the “horrifying love” (113) he feels for his own son must be contained—hence his cold-blooded attempt to drown Bishop.

Many of those involved in the formation of O’Connor’s reputation share with Rayber a method of confining what strikes them as strange and powerful—in their case, O’Connor’s fiction—to a neat space in which she and her work could be brought to heel. “Southern Gothic,” “Grotesque,” “Difficult,” “Woman Author,” “Catholic Novelist,” and even “Racist” are some of the cells into which readers have attempted to commit O’Connor. As she remarked, “Even if there are no genuine schools in American letters today, there is always some critic who has just invented one and is ready to put you into it.”23 The desire to categorically confine in order to conquer or dismiss, to do to O’Connor what Rayber tried to do to Mason, has been a feature of her reception by all kinds of readers.

Attempts to master the strangeness of O’Connor’s art with confining labels appear throughout the history of her reception, regardless of whether readers admired or detested her work. Such attempts frustrated O’Connor as she sought a wider audience. An examination of how she regarded the phrase “Catholic author” when used to describe her reveals O’Connor’s unease with the reductive power of reputation shorthand. In a 1960 letter to Betty Hester, she stated, “I am very much aware of how hard you have to try to escape labels” and described a reporter who interviewed her for Time magazine:

He wanted me to characterize myself so he would have something to write down. Are you a Southern writer? What kind of Catholic are you? etc. I asked him what kind of Catholics there were. Liberal or conservative, says he. All I did for an hour was stammer and stutter and all night I was awake answering his questions with the necessary qualifications and reservations.24

A year later, she wrote to John Hawkes that “one of the great disadvantages of being known as a Catholic writer is that no one thinks you can lift the pen without trying to show somebody redeemed.”25 The inability of many readers to avoid labels continued to vex her: in a 1962 letter to Cecil Dawkins, she stated, “I must be seen as a writer and not just a Catholic writer, and I wish somebody would do it.”26 And in a 1969 profile for the New York Review of Books, Richard Gilman recounted a conversation he had with O’Connor about this very topic: “If she disliked being known as a Southern writer, it wasn’t because she thought there was any loss or injury in being one—quite the contrary—but for the same reason she didn’t want to be called a Catholic writer: it was reductive, misleading.”27 A later remark from one of her letters concerning The Violent Bear It Away—“I suppose my novel too will be called another Southern Gothic. I have an idiot in it”28—suggests that such confining labels had retained their power to irk O’Connor throughout her career.

But such labels were not and are not always reductive. One of the reasons why people still read O’Connor today has to do with the very labels she resisted: the New Yorker’s statement in its review of the Prayer Journal, “It would hardly be an exaggeration to say that she is the most important Catholic author in American letters,”29 is hardly dismissive or limiting. The same is true for labels used to describe her work: “grotesque” can refer to an artistic method without the word’s pejorative sense, and “dark” can be used to illuminate O’Connor’s unique vision: in an article about Poets Corner, a New Yorker reporter stated, “ ‘Dark’ is a word often used to describe O’Connor’s fiction. But darkness can have many hues; in twentieth-century literature, it often means emptiness, the horror at nothingness that can’t be filled. In O’Connor, the looming darkness isn’t a void that threatens to swallow you; it’s the shadow of a piano that’s about to fall on your head.”30 Even terms like “parochial” and “provincial” can be terms of praise: in a perceptive appreciation of O’Connor that ran in the New Republic in 1975, the novelist Ellen Douglas argued that the “novelist’s point of view” and “attitude toward one’s work grounded in a narrow personal conviction” is a bulwark against what Marshall McLuhan called the “global village,” where “every scrap of the human stew is flavored with the same seasoning and pounded to a uniform pastelike consistency.”31 O’Connor’s parochialism is to be celebrated as informing her fiction and her provincialism as what allows her to know her chosen settings, her literal province, so well that it passes for real.

Douglas also knew that many readers regard southern writers as purveyors of provincial clichés: “ladies who write novels about hoopskirted heroines dallying in the moonlight with gallant gentlemen; and gentlemen who write novels about good country people with their coon dogs and corn pones.”32 Her allusion to O’Connor’s story about Hulga and Hulga’s own misunderstanding of that term reminds us just how misleading a description like “southern writer” can be and how O’Connor’s reputation is a small part of the larger story of how the South has been regarded by others since before the nation’s founding. For example, critics’ use of the adjective “southern” often invites their readers to play a game of word association, in which “southern” connotes “anti-modern,” “racist,” and other undesirable qualities. This game, of course, has a separate and complicated history of its own, detailed in scholarly work such as James C. Cobb’s Away Down South and David Goldfield’s Still Fighting the Civil War, neither of which explores O’Connor’s work but which illuminate the ways in which her reception was partly a function of how, since the American Revolution, “the dominant vision of the American character emphasized northern sensibilities and perceptions”33 and how, since Reconstruction, “the South became America’s nightmare.”34 The history of O’Connor’s reception by urban reviewers proves the truth of these arguments. In Dreaming of Dixie, Karen L. Cox concurs with the sociologist John Shelton Reed’s contention that those working in cities such as New York and Los Angeles have fostered an image of the South like the one detailed by Cobb and Goldfield; she argues that “films set in the South or ones that featured southern characters were most certainly expressions of the nation’s perception of the region and were in line with other forms of popular culture in their construction of various images of the South.”35 While she never mentions Huston’s Wise Blood, his film can be read as an extension of the story she begins with The Birth of a Nation and ends with Song of the South.

At the ceremony for O’Connor’s induction into the American Poets Corner, the Reverend Canon Julia Whitworth began with remarks about O’Connor’s appreciation of both the humorous and the holy. After noting that she herself was “also a southerner,” Canon Whitworth stated, “I appreciate in Flannery O’Connor her sense of deep location that helps us to understand something universal about home, about being, about being human, about being a stranger and being familiar all at the same time.” This sense of “deep location” has prompted many readers to assume that O’Connor’s work is fundamentally “about the South,” especially when examined by northern readers who followed the intellectual path laid by their predecessors, a path taken by many of the readers examined throughout this book. But such readers miss the point that original sin is an equal-opportunity employer. In his 1765 Preface to Shakespeare, Samuel Johnson argues that the Bard’s “adherence to general nature has exposed him to the censure of criticks, who form their judgments upon narrower principles,” “narrower” here referring to a verisimilitude that, to Johnson, is wholly irrelevant:

Dennis is offended, that Menenius, a senator of Rome, should play the buffoon; and Voltaire perhaps thinks decency violated when the Danish usurper is represented as a drunkard. But Shakespeare always makes nature predominate over accident; and if he preserves the essential character, is not very careful of distinctions superinduced and adventitious. His story requires Romans or kings, but he thinks only on men. He knew that Rome, like every other city, had men of all dispositions; and wanting a buffoon, he went into the senate-house for that which the senate-house would certainly have afforded him. He was inclined to show an usurper and a murderer not only odious but despicable, he therefore added drunkenness to his other qualities, knowing that kings love wine like other men, and that wine exerts its natural power upon kings. These are the petty cavils of petty minds; a poet overlooks the casual distinction of country and condition, as a painter, satisfied with the figure, neglects the drapery.36

Two hundred years later, in The Southern Mystique, Howard Zinn argued that even the “real South” itself—whatever that may be—is less actual than imagined: “Those very qualities long attributed to the South as special possessions are, in truth, American qualities,” and “the South crystallizes the defects of the nation.”37 Johnson’s defense of Shakespeare, Zinn’s reimagining of the South, and Whitworth’s argument that O’Connor’s southern landscape is the setting for “something universal about home, about being human” stand as welcome and necessary correctives to those who have regarded the truths of O’Connor’s work as particular rather than universal. For it is ultimately the universality of her themes and her insight into human nature that make her work worth the effort of reading and her reputation as a preeminent American author so well deserved.