CHAPTER 8: 1906–1912

Nationalization and Self-sufficiency

This postcard is probably the best known of the official postcards commemorating the 5,000 Mile Ceremony in 1906, replete with a distinct Art Nouveau influence and picturing Nagoya Castle in the town where the ceremonies were held. Nagoya was chosen in part out of tradition as the 1,000 Mile ceremony had been held there in 1889. Once again, the locomotive depiction is fanciful and bears a more faithful resemblance to the Johnson-Deely compound 4-4-0s of the United Kingdom’s Midland Railway (relatively new locomotive marvels at the time) than to any Japanese locomotive: probably another instance of a locomotive image being appropriated from a press article of the day.

Shortly after the end of the Russo-Japanese War, the inveterate traveler Charles Lorrimer traveled to Miyajima, a scenic tourist destination, via the IJGR Tokaidō line and the San’yo Railway, laying over for a night in Kyōto, and left an impression on what first-class travel was like aboard the best express trains of the time. He departed Shimbashi on the 6:00 am express to Kōbe, at a time when riots were feared to be brewing in Tōkyō due to the introduction of new tram fares of 4 sen. Cavalry was patrolling the streets, which he negotiated without incident or mishap: Lorrimer didn’t record whether he paused to breakfast at the Shimbashi branch of Tsubo-ya restaurant of Hiyoshi-cho, which was operating dining rooms on the second floor of the station by the turn of the century that served “European meals at all hours” and “French confectionery,” but he did observe that:

“Once at the station, the modern triumphs over the antique with a perceptible jar. ‘Red caps,’ as the porters are always called, clustered about us, seized our bags, turned each carefully upside down and then started serenely for the platform. At the ticket office window we saw several new notices posted up. These concerned the war taxes.... We ourselves paid a transit tax as well as an express train tax.

Unluckily, all this expenditure did not secure us much comfort. Other more enterprising passengers—early birds—had arrived before us. Their bags, carpet, leather, rattan, and their bundles, cloth, paper, silk, occupied at least half the seats. Some of the travelers had their blankets and rugs neatly spread out already, their air cushions blown full, their elastic-sided boots kicked off and placed on the floor in front of them, and themselves stretched full length on the seats enjoying a newspaper. We entered the car, coughed, and stumbled over the inevitable spittoon to attract attention. Not the slightest result. Nobody moved. Those exquisite Japanese manners, famous in two hemispheres, simply ‘were not.’ They never are—we have since been told—in trains, which, being modern Western inventions, were not provided for in the old rules of politeness. The best-bred Japanese in the land can therefore indulge in the absolute selfishness of squatter rights to his heart’s content.

We succeeded after some difficulty in squeezing ourselves between two yielding carpet bags just as the train started. Soon pretty scenery helped us to forget the discomforts of rocking and rolling incidental to the absurdly narrow gauge railways of Japan. Three feet six inches is not wide enough to give steadiness to any line, but at present the Japanese cannot afford to relay miles of track for a little matter of comfort. Indeed, since the [Russo-Japanese] war, economy is the motto for every department of public works, and so even the old-fashioned carriages whose seats run sideways and have their backs and arms at exactly the wrong angles cannot be replaced for some years.

[‘Shidzuoka’]... is a very important place, and the railway company acknowledges this fact by stopping the express there for one full round minute—just long enough to allow passengers to walk unjolted into the dining car.

We took advantage of this opportunity, installed ourselves at a table with the cleanest cloth in sight, and waited. At first we waited patiently. No attendant appeared. Then we waited impatiently, with the same result. As the car was small, but one ‘boy’ (a nom de guerre applied irrespective of the incumbent’s age) attended to all guests, and he happened at this particular time to be engaged in painfully working up the account of a Japanese gentleman and his daughter. In vain we beckoned, gesticulated, called; in vain we fumed and fretted, for we had all unknowingly run up against a simple law of Japanese society. Where servants in public places are concerned, the foreign guests wait for the Japanese...

All annoyances, however came to an end, and we finally saw our hated rival leave the car and ourselves treated to the menu. It was short and quaint, leaving us a most limited choice. There was a table d’hote lunch (called tiffin, of course, according to Far East custom) for 40 cents; a set meal composed of three dishes chosen by the clemency of the cook, and then, besides, there were separate things—a beefsteak at 10 cents, for instance, cold chicken at 7 cents, sandwiches positively given away at 6 cents. Apples at one cent formed the dessert. We found the beefsteak plain and eatable when washed down with the Japanese beer, which is so excellent and cheap, and the cold chicken neither more nor less tasteless than its colleagues all over Japan.

Our scanty meal over, we returned to our car and the pleasant surprise of seeing our full-length neighbors astir. There was much folding of rugs and flattening of air cushions going on in preparation for Nagoya, a big and important city, with a beautiful old feudal castle whose golden dolphins decorated the roof we saw quite plainly from our window. From Nagoya, the train hurried on past Gifu...

At 7:30 p. m. the lights of Kioto began to float past the windows like dainty fireflies singly or else in merry companies, and five minutes later we were in a big station bustling with directions and notices, ‘Station Master,’ ‘Keep to the left,’ ‘Passengers must cross the line by the bridge only.’ It would have been so easy just to slip across the track—but that would be an unconventional proceeding calculated to strike terror into the heart of Japanese officialdom, so we toiled laboriously up steps, across the overhead gangway and down steps again with a law-abiding crowd who would never have thought of rebelling against even the authority of a porter.1 The next morning we were in the train again and journeying for two hours past Ōsaka... to Kōbe...

The Sanjo [sic] Railway, is a line vastly different from the Tokaidō. It has an excellent roadbed and wide cars, which help to mitigate the discomforts and annoyances of the absurd narrow-gauge system unfortunately fastened on Japan.

At noon, we had our second experience in a Japanese dining car. The menu was identical with that on the Tokaidō train, but things looked far cleaner and more inviting. Unfortunately, there was no Kirin beer to be had, and we were offered Yebisu, a brand of a more bitter flavor, instead.... At the very hottest hour of the afternoon, our train drew up at Miyajima station. The station at Miyajima was as primitive as treaders of unbeaten tracks could wish... a hotel boy dressed in a cap, and undershirt, short trousers and bicycle stockings took our bags. He had just sufficient English at his command to say ‘cross sea in sampan’ as he led the way down a tiny village street lined with inns to the shore. A little steam ferry puffed away from a doll’s pier just as the train arrived without waiting for passengers. In true Japanese fashion, her agents had fixed the time-table irrespective of the express, and most of our fellow travelers sat themselves on the beach in a broiling sun to await the steamer’s return.”

How the rest of us traveled: a Tokaidō line train with Hamamatsu destination boards below the window at far left. This 1902 stereoview is titled “Ten Minutes for Refreshments;” a typical scene in Meiji Japan each time such a train would stop at a station of any size. From left, the first hawker is selling small food items, the second is bending to pick up a pot from his inventory of tea pots, the third is selling bottled beverages to a standing passenger, who stands in front of a hand truck carrying what appears to be foot warmers for rent or exchange, tended by the staffer at far right. This scene represents what was by far and away the most prevalent form of obtaining meals while traveling by rail in Meiji times. Dining cars were not introduced until 1900 and, even by the end of the Meiji reign, were only available on select express trains of the day.

Aside from the quaint and remarkable difference between Japanese express trains of 1905 compared to today’s polished Shinkansen expresses, Lorrimer’s comments show how deeply attached the Japanese populace had become to its rail transport. For a country that feared, in 1872, that the populace would be antithetical to railways, it is quite telling that a mere 30 years later, the public had become so dependent upon their city trolley cars that they would threaten to riot over a three sen (about a cent and a half) increase in the Tōkyō trolley fare. By this time, railway fares were two sen per mile for first class on IJGR lines. First class passengers were allowed one hundred kin (60 kilos, or just over 130 pounds) of baggage free. Excess baggage was charged at a rate of one sen per kin for journeys of less than 25 miles, 1½ sen for trips between 25 and 50 miles, and two sen for trips between 50 and 100 miles.2 Baggage could be checked through to almost any station, and the railway company would conveniently deliver it to any city address or carry it by cart for a considerable distance into the surrounding countryside. On the well-travelled Shimbashi– Yokohama trip, the cost of a first class ticket had dropped by 20% from its 1872 level to a fare of 90 sen, while second class had dropped by 30% of the 1872 rate to a fare of 53 sen, and third class had dropped by more than half to a fare of a mere 18 sen. For the record, the fare for a pet dog on a journey of less than 25 miles was two sen, about the value of one US cent in 1904.

A pencil drawing by Kashima Shosuke of a Sleeping Car for the IJGR built in the UK by Oldbury Railway Carriage and Wagon Co., as running circa 1903. Although the IJGR had long been self-sufficient when it came to wagons and carriages, it ordered sleeping cars to identical specifications from the UK and USA for the Night Tokaidō Express it inaugurated between Tōkyō and Kōbe around the turn of the century. Kashima describes the livery as being chocolate brown, lined in gold, “kept polished like a piano” with varnished cabinet oak interior. The American cars varied in that there were two, not three windows per compartment. Kashima lists the consist of that express in 1903 as being one baggage van, two 2nd class day coaches, one 1st and 2nd composite carriage, one 1st class sleeping car, one dining car and one 2nd class and mail combine, each being 50 feet long and 8’ 10” wide. There was no third class accommodation on this initial IJGR train de luxe.

In the aftermath of the Russo-Japanese War, the military emerged as a driving force in Japan, and given its influence on the Railway Council, its views on railway development were increasingly heeded. Preeminent among the railway matters which interested the Ministry of War was nationalization, which was thought would make management and coordination of the railway system much easier in times of war. This added weight to a movement that had been afoot for some time. The Nippon Tetsudō had not been completed to Aomori for two months before Inoue Masaru presented his ‘Proposal for Railway Administration’ to the Government. Among other things, it was a proposal to nationalize the country’s private railways. In November, 1891, the Matsukata cabinet put a motion before the second Diet to nationalize the railway system. The stated purpose was to speed development of the railway system by putting into government hands the construction of those lines where the organizing companies were having trouble raising funds. The motion failed in part over fears that it was merely a sop to the investors and because the legislative session ended. The issue was brought up a second time the next year as part of the 1892 Railway Law agenda, but the Matsukata cabinet again did not succeed in passing it. The next proposal was made by the opposition Liberal Party in 1899, which carried by a vote of 145 to 127 and the issue was thereupon referred to a committee, chaired by Viscount Yoshikawa, which failed to render its (favorable) report before the end of that particular session, and the measure again died. The fourth attempt was made in 1900 under the Yamagata cabinet, which failed in face of opposition by a coalition of the Liberal, Imperialist, and Progressive parties. By this point, the public started to take an active interest in the matter.

With the end of the war, the military, and its political supporters, were not satisfied with the potential for operational integration that a railway system consisting of various private railways seemed to be capable of sustaining. The military successes of the recent war, coupled with the public dissatisfaction with what was perceived to be a less than warranted treaty result and the political situation in China (it was apparent to all in 1906 that the Ch’ing dynasty was on the verge of collapse, as indeed it did as a result of the revolution that came only 5 years later in 1911) all combined to tempt Japan to ready itself for even greater acts on the Asian continent. Militarism was becoming ingrained in Japanese foreign policy. If that were to be the course of Japanese foreign policy, a nationalized railway system was seen to be preferable to the one in place. New arguments for nationalization were again brought before the Diet, and the debate renewed. It was asserted that nationalization would permit freight and passenger rates alike to be cut, but of course, rate cutting regulation short of nationalization could have accomplished the same thing. Proponents seized upon the operational and organizational economies that would result in a single integrated system, which in hindsight seemed to have overlooked the countervailing inefficiencies of government bureaucracies vis-à-vis private enterprise. Nationalization was seen as a means of preventing railway ownership from falling into foreign hands via stock purchases or mortgaging of assets, but this as well could have been prohibited with laws restricting stock sales or encumbrances to foreign individuals or entities, short of as drastic a measure as nationalization and, like the rate reduction argument, was not thoroughly convincing. However, this time the military added considerable weight to the debate and in the aftermath of the Russo-Japanese War, its political capital was second to none in the realm. The military vociferously asserted its dissatisfaction with the coordinating abilities of the various private railways in the past war, but conveniently ignored the fact that many of the delays and inconveniences were not attributable to internecine squabbles between various private railways, but were more likely the natural consequence of a railway system that was still overwhelmingly single-tracked and strained to its limits. (Of course, the problems created for the railway industry by shipping sorely needed domestic locomotives to the theatre of operations exacerbated the shortage of domestic motive power at a time when the system was being worked à outrance, only making matters worse and contributed to the false sense of systemic failure.) An ambitious program of double-tracking all primary routes might have been just as effective a solution. The various arguments pro and con were posited, but in the end, after more than a decade of debate, the vote for nationalization carried in the Diet on March 31, 1906. Watarai Toshiharu, the former assistant councilor to the Imperial Board of Railways, speaking in 1915, before the period when such criticism became difficult to make, bluntly stated in his doctoral thesis on the subject of the recent Japanese nationalization, “There is no doubt that nationalization was carried through mainly on the strength of the military argument” and labeled the arguments that had been marshaled in support of it “not very convincing.” The first seeds of the growing militarism were germinating, and as a result, the railway system was being affected, but it was certainly fair to argue that due to the government’s policy of building lines that private ventures did not want to undertake (as extensions of private railways, as isolated independent lines, or as connecting lines between private railways) the IJGR was a fragmented system, and nationalization resulted in a considerable benefit to the IJGR in the systemization and economization resulting from integration of the fragments into a unified network.

A first class sleeping compartment on one of the IJGR’s compartment sleeping cars is shown here made up for night on the right side, and day travel on the left. A folding table is between the seats, and a ventilator above the left-most window. The ceiling is finished in embossed Lincrusta, a forerunner of linoleum. First class compartments featured state-of-the-art cooling by means of an electric oscillating fan. This type of carriage would have been part of the first IJGR trains offering sleeping car services. It is probably a compartment of one of the British-built examples shown on page 225.

This view of an express train on the Tōkaidō Line was taken in the 1905–1906 period and shows how one of the better express trains of the day would have appeared. It is piloted by one of the Brooks 5160 Class 4-4-0s, and when one considers the small driver diameter of these machines, it is no wonder that a good turn of speed on trains such as these was considered to be 35 miles per hour. This rake of 7 coaches is fairly typical of heavy express train lengths at that time.

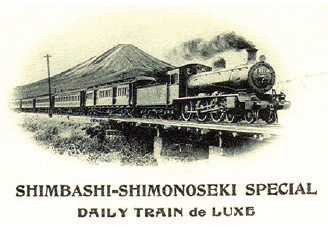

By 1911, new cars and locomotives had been introduced on the Shimbashi-Shimonoseki Special Express. This view shows the up section steaming by Fuji on the Tōkaidō Line, en route to Tōkyō. This train would later be renamed The Fuji. The locomotive is one of the North British 4-6-0 8700 class with Walschaert’s valve-gear, bearing running number 8711, one of the last British-built locomotives imported for the IJGR in 1911, the year before the IJGR adopted the policy of using only Japanese-built locomotives. It was purchased to serve as a model for study by the IJGR in formulating their standardized line of locomotive designs. Similar locomotives from the same builder were used on the meter-gauge Royal Thai Railways.

Taken in 1905 this photo shows the interior of one of the first IJGR dining cars introduced on the joint express operated by the IJGR and the San’yo briefly before nationalization; the Shimbashi–Shimonoseki Special Express.

Compare the interior of this dining car of the late Meiji stock with the earlier version shown above and observe the results of the efforts that had been made to increase the loading gauge in Japan and to widen and heighten the interior space of rolling stock that was undertaken when Baron Gōtō Shimpei assumed leadership of the IJGR in 1908. In the space of a few short years, a much more spacious effect was attained through these efforts and the introduction of a higher clerestory roof to the dining car shown.

The version of the Shimbashi– Shimonoseki Special Express as running in the very last years of the Meiji reign is seen in these two diagrams, showing the floor plan of the consist and, from left to right, order of carriages in the seven-car train. From the diagrams’ staff seat count, one assumes that the IJGR crew was 10 in number, an Engine Driver, Fireman, Chef de Train, two Guards, and a “Boy” for each carriage except the Mail/Luggage Van and Dining Car. Add to this the postal workers and the waiters and cooks who would have been employed by the concessionaire of the dining service, and the number approaches a total of around 20 staff members. The diagram proudly notes that complimentary stationery is available at the desks found in the observation parlor. Letters written en route would have been given to one of the “Train-Boys” for purchase of stamps, delivery to the mail van, and posting at the next stop. The view of the train steaming along beside Mt. Fuji piloted by the North British 8700 Class 4-6-0 locomotive (shown on page 226) is taken from the letterhead of that stationery.

While the government carried the day, it did not do so without notable opposition. The measure only carried at the end of the legislative session, after opposition members had walked out. Cabinet member Katō Takaaki, the foreign minister, was so strongly opposed to nationalization as an invasion of private property rights that he resigned in protest. Typically, such resignations had in the past been couched in terms of ill-health, to spare the Emperor the embarrassing appearance of having disunity within his cabinet. Katō however felt so strongly about the matter that he was the first minister in the modern political history of Japan to state the true reason for his resignation, which is said to have raised the Imperial eyebrow.

With passage of the bill, a formula was determined for paying the shareholders for the value of their shares. In the end a scheme was adopted that guaranteed a price equal to the average rate of net profit to the companies absorbed during the first six working half-years from the second half of 1902 to the first half of 1905 multiplied by the aggregate construction costs up to the date of purchase, and multiplying that amount by 20 times to arrive at the final price. Materials and stock in hand were to be reimbursed at prevailing market prices. Further provision was made for non-leased rolling stock being covered by a series of state bonds. Shareholders were also paid for their outstanding shares by state bonds issued in exchange. The total price for nationalization was reported at about ¥500,000,000. The total purchase price was relatively high, and burdened the national system for some time, while making a very favorable settlement that notably benefited the former daimyo, samurai, and court nobles who, as a class, had been heavy investors in private railways.

The comfortable interior of the Shimbashi–Shimonoseki Express observation car (looking toward the locomotive end of the train) consisted of this lounge with cushioned rattan armchairs, writing desks to the fore of the compartment, and was stocked with album-sized books, which one imagines encouraged rail travel and tourism. Presumably this photo was taken shortly after cleaning, as the floor has yet to dry from a vigorous swabbing.

Initially, the nationalization law (Tetsudō Kokuyuka-ho) called for the nationalization of some 35 private railways. The bill was introduced in the lower house of the Diet, while the upper house amended the bill reducing the number to 17, and the lower house agreed to the amendment, bringing the number down to 17 lines, among which were what was known as the “Big Five” (the Nippon, San’yo, Kansai, Kyūshū, and Hokkaidō Tanko) and twelve of the remaining largest, most important lines. For the record, on the date of transfer, October 1, 1907, the other twelve railways absorbed were: the Bōsō, Gan’etsu, Hankaku, Hokkaidō, Hokuetsu, Kōbu, Kyōto, Nanao, Nishinari, Sangu, Sōbu, and Tokushima Railways. What was left after nationalization of these lines were basically commuter lines or short lines of local character, and that was to be the flavor of future private railway development for many years to come.

As the old century came to a close and the new century opened, tables were being turned, and increasingly Japanese personnel were serving abroad, in yatoi-like capacity, on the Asian mainland. This occurred first when Taiwan was transferred to Japanese possession in the aftermath of the Sino-Japanese War. As mentioned earlier, the next logical extension occurred in Korea. As a result of the Russo-Japanese War, that influence spread to Manchuria. In 1907, for example, the British trade monthly Railway Gazette was reporting that “the first railway in China built with Chinese capital,” the line between “Chaochowfu and Swatow” (Chaozhou and Shantou), was constructed using crossties supplied from Japan. Additionally, all the line’s passenger coaches were built in Japan by Japanese rolling stock builders. And, reminiscent of the first decades of railway development in Japan, the enginemen, conductors and the train dispatcher were Japanese. Japan was quickly taking its first steps at becoming an exporter of railway technology.

The Shimbashi–Shimonoseki Special Express interior views shown here consist of the observation car special state room, replete with palowinia crest lacquered panels and plush upholstery spangled with gold embroidered mon on the seats, followed by the standard sleeping car, the dining car, and the vestibule corridor, then something of a novelty of which to be proud in a country that had long followed the British example of non-corridor compartment carriages. In its day, the stateroom represented the ne plus ultra of overland traveling comfort, affordable by only the wealthiest of passengers.

By 1909, the nationalized lines were settling into a working system to enough of an extent that a comprehensive numbering scheme to organize all the duplicated running numbers of the locomotives absorbed was adopted. In the same year, the Government Railways Account Law was passed, which separated railway accounts from the government budget, insuring that the railways would not be used as a cash-cow to make good budgetary shortfalls or to fund government spending sprees. This proved to be a sound decision and the policy of financing future railway expansion out of profits was immediately adopted. Eventually it became clear that, windfalls to the upper class notwithstanding, the government had still struck a good deal in buying up the railways, and the trend continued for some years. One economics commentator in 1934 noted,

With the addition of this Observation/Lounge Car to the rear of the train, the Shimbashi–Shimonoseki Express showed influence from American luxury express trains. This view shows the end veranda of the car, which was introduced in the final years of Meiji’s reign, to good effect. Note that even on the finest example of rolling stock in the realm (barring Imperial carriages), the IJGR frugally opted for a plain three-link loose chain coupling rather than a screw coupler.

“One of the main principles of their [the Government Railway’s] business policy is to prevent the railways from getting into debt. Up to now [1934] these endeavours have been entirely successful. All new constructions as well as purchases of new equipment are exclusively made out of profits, whilst at the same time a substantial amount is carried forward each year to the next year’s account. The Japanese railways are sparing no effort to ensure up-to-date equipment and construction work capable of lasting many years. This is proved, among other ways, by the fact that bridges and tunnels are made from granite which is a very expensive material and specially used on American railways. It is for this reason, too, that the coaches are fitted with pneumatic brakes and that all-steel passenger cars are constructed.

The Japanese railways employ the greatest care in the maintenance of their rolling stock, as appears from the fact that the number of new cars and locomotives put in commission each year represents a very considerable percentage of the existing equipment. This is, of course, only possible with a railway administration so highly profitable as that of Japan.”

In addition to nationalization, another scheme which had been debated, shelved, re-debated, and re-shelved with seeming clockwork regularity in Japan was again brought down from the shelf and dusted off. The military would have preferred to have re-gauged the entire Japanese railway system to 1435mm gauge, and the word of the day was that the entire rail system was “inadequate to meet the requirements of the present time.” It is difficult to imagine today how important railways were in a time when they were the sole efficient means of mass land transport, doubly so in Japan with its inadequate roads. With nationalization came yet another bureaucratic restructuring, and a new Railway Agency, also called the Board of Imperial Railways, was created in 1908. Since Inoue had departed in 1893, there had been a constant change in the officials who held the nation’s top railway post, none of whom left as much of a personal legacy as Inoue had managed to do. Inoue’s immediate successor Matsumoto served until May 13th 1897, when Suzuki Daisuke assumed the post, serving only a mere seven months, until December 18th. Thereupon, Matsumoto resumed the helm, serving until he was succeeded by Hirai Seijiro on March 20, 1903. Hirai served only eleven days before the post went to Furuichi Kohi. Furuichi himself only served 8½ months from March 31st to December 28th 1903, at which point Hirai Seijiro returned to the top post, to serve until December 5, 1908. On that date, the new head, Baron Gōtō Shimpei, assumed his post. Gōtō was the most energetic and dynamic figure to preside over the Railway Agency since Inoue’s departure, and in many ways was the only one of comparable stature to him during the entire Meiji reign. None of the intervening heads managed to leave the mark that either Inoue or Gōtō managed to make.

The view towards the rear of the observation car of the Shimbashi–Shimonoseki Express around the first years of the Taishō era.

Borrowing from Western precedents, in 1906 the Ōsaka Jiji Shimpo newspaper sponsored the traveling exhibition train shown stopped at an unknown location in this commemorative postcard. Traveling expositions such as this helped acclimate the populace in more remote locales (who still traveled very little) with the advances and modernization being made in the leading centers of the realm. Note the special multi-colored livery of the carriages.

In frock coat and top hat after having reported to the Emperor on his return from an official visit to Russia, Gōtō Shimpei, who was always impeccably dressed, poses for the photographer. Baron Gōtō originally studied medicine in Germany and return to Japan to practice. He was destined for greater things however, and eventually he served as the colonial head of the Railway Administration of Taiwan. By 1906 he was named the first President of the South Manchuria Railway (one of the gains of the Russo-Japanese War), and was brought home and appointed Director-General of the Railway Agency in 1908. It was under his tenure that Tōkyō Station was completed and dedicated.

Among one of his first acts, Gōtō obliged conversion proponents by directing the laying of a third rail experimentally along a stretch of track to test how easily such conversion to “Standard” 1435mm gauge could be accomplished and assigning IJGR engineers to conduct a gauge conversion feasibility study. The report was favorable enough to result in the Diet appropriating ¥269,644,190 for gauge conversion for the 800 route miles from Tōkyō to Shimonoseki during the tenure of Prime Minister Katsura Taro in November 1910, which was almost immediately reversed on grounds of cost when the Seiyukai party of Saionji Kinmochi returned to power in 1911. In the end, all that was accomplished was the modification of existing tunnels and trackside structures so as to permit a larger loading gauge, and enlarging the rolling stock to the new larger standard, as an expedient. The conversion issue itself again was shelved, only to be brought down again in the early days of the Showa reign, when congestion along the Tōkaidō line had reached such a point that preliminary studies for building an entirely new trunk line of standard-gauged railway between Tōkyō and Kyōto–Ōsaka were undertaken. The Second World War interceded to postpone the gauge conversion matter once more, but after the war, in the 1950s, it was again revisited and the 1930s study for the “new trunk line,” (Shinkansen in Japanese) was again brought down, and used as the preliminary point of departure for the development of a supplemental Tōkyō– Kyōto–Ōsaka route. Out of this grew the famous Shinkansen “bullet train” system (built to 1435mm gauge) that today is the envy of the world.

This view shows Manseibashi Station, the start of the Chūō Line. In front of the station is the statue memorializing Cmdr. Hirose Takeo, a hero of the Russo-Japanese War killed during the siege of Port Arthur. The station was situated at the end of a spur from a junction near Shinjuku on the Akabane line and served as a terminal for Kōbu Tetsudō and IJGR trains. It was designed by Tatsuno Kingo, the architect of Tōkyō Station, and shared much with that station in terms of aesthetics. The station was greatly damaged during the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923 and was not rebuilt. The Museum of Transportation was, until quite recently, for many years situated on a portion of the tracks where Manseibashi (from the nearby-named Thousand Year Bridge in Tōkyō’s Kanda district) once stood.

Yotsuya was another station along the Chūō line between Manseibashi and the Akabane Line. In this pre-electrification view (dating it to before 1904), a down Kōbu train consisting of 4-wheel compartment carriages and probably an A8 tank locomotive is making a start from the station on its way to Shinjuku. The photographer is probably situated near a roadway bridge that crossed over the line at about this point. The ballast piles along the station sidings would lead one to suspect that the view dates to shortly after opening, when ballasting was still being completed.

Farther along the Chūō Line, a IJGR Hode 6110 class EMU makes its way in the height of cherry blossom season along the former outer castle moat. Note the electric disk signal, colloquially known as a “Banjo Signal” in America and as an Enban-type in Japan, an innovation of the Kōbu Tetsudō and among the first electric signaling installed in Japan, borrowing from American signaling practice.

One of the Hanshin Electric Railway’s cars is shown here at the simply-but-solidly-built Ikutagawa bridge on its way between Ōsaka and Kōbe. The name Hanshin is another portmanteaux word derived from taking the second character “saka” from Ōsaka and “be” from Kōbe, and pronouncing them using their Chinese pronunciation to achieve the word “Hanshin.” Identical linguistic practices were sometimes used in naming US railroad lines; to wit the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Delmarva division. As the Hanshin was privately built, and was engineered well after the disadvantages of the Japanese standard gauge of 1067mm were becoming appreciated, it was built to the more conventional gauge of 1435mm.

An IJGR train travels along the Chūō line at Ushigome-Mitsuke, along the outer moat of the former Edō castle, bearing a post-1909 number plate with a train of late-Meiji stock. The image dates from the transition time around the close of the Meiji and beginning of the Taishō eras.

Improvements continued in the wake of nationalization. This period saw the first proposals for steam railcars; two prototype designs—company drawings 12644 and 14866—were produced in 1906 and 1908 by the UK’s Metro-Amalgamated (as the renowned firm of Metro-Cammell was then known, itself a successor of the Oldbury Railway Carriage and Wagon Company that had built the first carriages for the Shimbashi line in 1872). One was a rather British-style steam railcar of the period, the other was an open “toast-rack” configuration with weather-curtains. Neither were ever built or imported—domestic models were soon to be introduced. The year 1908 saw the introduction of the first refrigerator cars to Japan, built for transporting fish in quantity from the fishing banks off Korea. Initially only ten were built, but they quickly came to be used for all types of perishables, and within roughly twenty years’ time there were 1,250 in service.

The Chūō line right of way followed the Ocha-no-mizu Canal (Tea Water Canal, from the purity of its water) part of the way from its Manseibashi station starting point to the junction with the Akabane line near Shinjuku. The Kōbu Tetsudō and IJGR both operated trains to Manseibashi. From Shinjuku, the Kōbu line ran to Hachioji, over which the IJGR had running rights, beyond which the Chūō line proper headed west. This view of the Suidobashi taken from the Surugadai neighborhood shows an IJGR up train heading for Manseibashi. The EMU appears to be a Hode 6110 class, introduced in 1911, dating the view to the closing years of Meiji reign or early years of Taishō. The factory complex to the right is a government arsenal, now the location of the Kōrakuen garden.

Of course one of the consequences of nationalization was that the investors in the private railways suddenly found themselves divested of their shares, in place of which they had the proceeds of the conversion. Many of these of course, were the next generation of the Samurai families who had used their stipend settlement monies to invest in railways in the 1880s. Much of this money was again reinvested by these families into a new technology that was still a “start up” at that time: electric generation and with it, electric-powered interurban railways. An outgrowth of the municipal trolley system, the interurban railway was in great currency in the US as a clean and rapid alternative to steam-hauled railways. After the first electric trolleys were introduced to Kyōto in 1895, trolleys came to be adopted in many Japanese cities, including of course Tōkyō (1903), Ōsaka (1903), and Yokohama (1904). In 1904 also, the first suburban railway section was electrified on the Kōbu Tetsudō, which ran in the Tōkyō area. One year later, the Hanshin Denki Tetsudō inaugurated the first electric interurban service between Kōbe and Ōsaka.

The benefits of electrification of railways were immediately apparent to all, and electric lines, at a time when similar lines were in great currency in America, began to sprout in major metropolitan areas. Japan was not blessed with superabundant coal reserves, relative to the position of the United Kingdom or United States, for example. Most coal located in the Kyūshū and Hokkaidō beds was good for generating steam, but soft and very smoky, as has been seen. Being an extremely mountainous country, Japan had the good luck of being ideally situated for application of hydro-electric engineering to build facilities to harness the generational potentials of its many mountain rivers as they descended along their courses. By as early as 1913, it was being noted in the engineering journals that a not inconsiderable reduction in Japan’s coal consumption among railways had been affected. Some of the coal that hydro-electric generation saved began to be put to use in foreign trade: by 1912, for instance, Japanese coal was being exported and sold cheaper than competing US and Australian varieties to the Chilean State Railways.

The IJGR was as quick to capitalize on the new form of motive power as finances permitted after the war. The most mountainous sections of line were the prime candidates for electrification. The Usui Pass segment of the Shin’etsu Line was one of the first segments to be electrified in 1911. Neat appearing Abt system electric locomotives, designated the “10000 Class,” from AEG of Germany were imported for the duty, were initially assigned to passenger trains, and soon rendered obsolete the Esslingen, Beyer-Peacock, and domestic-built tank locomotives that had previously been used. Their introduction did not come any too soon for the long suffering crews who worked the summit segment; the conditions on the line were close to unbearable, even by the lax safety standards of the day. Charles Pownall, the Englishman who served for many years as the Chief Engineer of the IJGR and who quite naturally would have been expected to have taken a “management” view of operations, described the conditions on the Usui segment prior to electrification:

“The present 34-ton engines of the Usui line are worked with a strong forced draught in order to obtain as much steam as possible, and this causes an excessive amount of smoke—a great annoyance in the numerous tunnels, up which the smoke rises. The engine is always below the train [to prevent break-aways]. As the speed is so slow the train cannot run away from the smoke, which follows and overtakes it when the wind is blowing up the valley.”

There were only two tunnels built for municipal trolley lines in Meiji Japan. One was in Wakayama, and the other is the one shown here in Yokohama. The scene shows the arrival of Yokohama Municipal trolley 32 on a brisk, sunny fall day as a small crowd waits to board. Above the tunnel is seen the fabled Yokohama Bluff, historically a part of town where the more fortunate residents built their homes.

The Minō-Arima Denki Tetsudō opened to Takarazuka (famed for its hot springs) on March 10, 1910, and this view shows what looks to be the first train of the morning ready to depart that station, as the points are set for it to crossover onto the up line. The railway was built to link the growing Kōbe-Ōsaka metropolitan area with the resort town of Minō and eventually became part of the Hankyū system, the president of which would be seeking ways to increase the revenues of this branch in the 1920s and hit upon the idea of creating an all-female theatrical troupe in the town in order to augment ridership. Thus was created the Takarazuka Review, still widely popular in Japan with female audiences.

Yamada is now one of the stations on the Kintetsu in Ise, near the venerated Ise Shrine. This view shows what was probably a Miyagawa Denki Tetsudō tram making its way over a very elaborately constructed wooden Shioai Bridge in the environs.

By the end of the Meiji period, railways had become matter of fact for many walks of life; and electric ‘interurban’ lines, many of which were destined to become Japan’s network of commuter lines, had penetrated the fabric of daily life to the point that even those of more modest means sometimes traveled by rail as part of their routine activities, as evidenced by this classic “Pre-schoolers’ class trip” view. Judging by the Gibson Girl hairstyle of one of the teachers, the scene would date from the mid to late Edwardian era. Note the teenage boy with his hand behind his back, who apparently serves as the station’s ticketing clerk and is supervising boarding. The boy at the far left seem to be acutely suspicious of the photographer. The location and railway are unknown, although the gauge appears to be 1435mm, judging from the car width.

Kōzu station on the Tokaidō mainline is shown in this turn-of-the-century view. Kōzu is situated on the shores of Sagami Bay and was the point where the Tokaidō line turned inland (in the Meiji era) to skirt the various peaks in the vicinity of Mount Hakone. With completion of the Tanna tunnel in 1934, Kōzu became the junction at which the Tokaidō line’s Tanna cut-off diverged from what was re-designated the “Gotemba Line,” as the existing portion of the Tokaidō line became known. A trolley-powered train of the Odawara Denki Tetsudō is seen in the station forecourt ready to depart, perhaps as a connecting service timed to the arrival of the next Tokaidō line train.

Commenting on the problem, Francis Trevithick noted that the Japanese coal, while giving excellent steaming quality, was very smoky. As a result:

“The ventilation of the tunnels was a very serious question, there being twenty-six tunnels, 2.76 miles, in a distance of a little over 4 miles. The atmospheric conditions in these tunnels were very trying to those on the engine, the immediate cause being the intense heat of the air, caused by the great volume of steam from the four cylinders working together, and almost without expansion, and added to other products of combustion discharged from the chimney. The feeling on the uncovered parts of the body was not far short of acute pain, and to this was added the necessity of breathing the heated atmosphere. The conditions varied with wind and weather; the same tunnel would be passed through on the same day, one time without discomfort, the next with great discomfort. The train on entering the tunnel acted as a plunger or piston, driving the air before it: the exhaust steam was discharged against the tunnel roof, and enveloped the engine in smoke; the vacuum caused by the train entering the tunnel was filled with the air following the train into the tunnel, this volume of moving air being increased as the train proceeded and being also aided by the incline of 1 in 15, and by the condensation of the steam from the engine. Eventually, this volume of air drove the smoke beyond the engine and the carriages. A canvas curtain was now pulled across the mouth [of the tunnel] directly [after] the train had entered. The vacuum was then filled with air from the front of the train, thereby keeping the smoke behind the engine. This arrangement had acted in a more satisfactory manner than any other appliance which had been tried. The speed with six carriages (50 tons) was about 5 miles per hour.”

Most conventional locomotives had only two cylinders, so an increased volume of steam was emitted by the special Abt system four cylinder locomotives (two of which powered the cog drive) used on the Usui Line. The new electric locomotives must have come as a very sweet relief to the crews who worked the trains over the Usui line, and management was probably also pleased that the 2 or 3 staffers who would have been required to station themselves around the clock on stand-by status at each of the tunnel mouths for “canvas curtain duty” could be re-assigned to other tasks. Unfortunately for freight train crews, the steam locomotives continued to be used for some time, as there weren’t enough electric locomotives to handle all traffic.

The Odawara Basha Tetsudō opened in 1888 from Kōzu first to Odawara, and eventually ran to the hot springs resort of Yumoto, roughly halfway up the ascent of Mount Hakone, along the route to the popular resort town of Miyanoshita. By 1896 it had converted from horse operation to electric traction and changed its name to Odawara Denki. A short tram-and-trailer train is shown here crossing the bridge over the Sakawa River after electrification. The scene is archetypal of Meiji-era tramways, the rights-of-way of which were permitted to be built to the sides of public roads and bridges under the 1910 Light Railway Law.

The Enoshima Denki Tetsudō completed its first segment in 1902 on the way from the town of Fujisawa on the Tokaidō Line to the scenic islet of Enoshima. By 1910 it had reached beyond Enoshima to Kamakura, running along the celebrated Shichirigahama (Seven Ri Beach named for being approximately seven ri, about seventeen miles, long), to its Kamakura terminus. Four schoolboys walk along a local road as an Enoshima interurban runs by in this view of that famed beach with Enoshima Island and Mt. Fuji in the background. The Enoden maintained its independent existence and is still a popular line today.

Due to its proximity to Tōkyō, the Odawara Denki became very popular with Japanese and foreign visitors alike. This post-conversion view shows a tram-and-trailer train approaching the terminus in Yumoto, undoubtedly loaded with more than a few refugees from the ever-increasing urbanization of the Metropolis seeking fresh mountain air and a soak in the celebrated onsen. In 1901, the trip from Kōzu to Yumoto took about one hour by these tramcar trains. This part of the line would eventually become part of the Hakone Tozan Tetsudō.

This view of the civil engineering that went into building of the Hakone Tozan Tetsudō illustrates why the potential offered by the new technology of electric traction was of particular utility in Japan. Electric cars such as this were powered with an electric motor on each axle, while on a conventional steam-powered train only the driving wheels of the locomotive proper were powered. The grade indicator in this photograph of one of several switchbacks seems to indicate a grade of 12.5 in 1 (8%). No steam locomotive could have climbed such a steep grade, unless it was cogged, as was the case of the slow-moving Abt rack locomotives used on the Usui Pass line, which averaged roughly 5 miles per hour. The electric cars of the Hakone regularly took this grade in stride and at speeds well in excess of the speeds that could have been obtained on a rack railway. By the close of Meiji, electrification had begun to establish itself as one of the most promising agents of modernization for Japanese railways.

It goes without saying that, in those days of less management concern about rank and file well-being, for such a matter to have drawn the attention of top management such as Pownall and Trevithick, it must have been grave indeed. Nevertheless, the IJGR was taking positive steps to ameliorate the lives of its workers. In 1911, the first mutual aid society was established, providing disability allowances, employee discounts for daily necessities of life, and loans to members at attractive rates.

As 1909 turned to 1910, the last segment of major inter-city mainline railway was completed; linking Kagoshima, the southern-most major city of Japan in Kyūshū with the railhead at Hitoyoshi. It was the last link in a 1,750-mile-long main-line system that linked Kagoshima, at the extreme south of Japan, with Nayoro, which was the northern-most point to which rails had been pushed in Hokkaidō. To have made a trip between those two points would have taken a mere five days and nights of travel.

The future for Japan’s railway system is evidenced in this photograph near the junction point where the Tokaidō line diverged from the old Shimbashi–Yokohama line that continued on to Sakuragicho station. Four trolleys and one train are shown, all electric-powered. At the time this photo was taken, it would have been difficult to have replicated a similar scene anywhere in Asia, with the possible exception of India, where the first electric locomotives had been introduced in 1907.

Japan was eager to increase goodwill among the Korean people in the period between the end of the Russo-Japanese War and annexation in 1910. Accordingly, in 1907 the Japanese Crown Prince Yoshihito, the future Taishō Emperor, made a goodwill tour. His train is seen here, piloted by an American-built tank locomotive, which would probably suggest the location of Pusan Harbor, where the Crown Prince would have begun his journey over the Japanese-built Seoul–Pusan Railway. The railway issued this postcard to commemorate his visit.

Railways figured prominently in the diplomacy of the times. In 1907, as Japan was embarked on the assimilation campaign that preceded its annexation of Korea in 1910, it was decided that the Crown Prince, Yoshihito (later to reign as the Taishō Emperor, the father of WW II’s Emperor Hirohito) would make a goodwill tour of Korea. He traveled in a special Imperial train turned out by the Japanese-built and controlled Seoul–Pusan railway on the occasion of his visit, arriving in Seoul on October 16th of that year.

No less than three of the articles of the Treaty of Portsmouth which ended Russo-Japanese War dealt with the subject of the railways in Manchuria. Russia and Japan were required by that treaty to “conclude a separate convention for the regulation of their connecting railway services in Manchuria.” At that time, the quickest way from Europe to the Far East was via the Trans-Siberian Railway’s express trains (slow though they were) and this line of railway, with those through Manchuria, were expected to develop into a major traffic route. It was said that travel times from Europe were reduced by as much as 75% from some of the more remote points with the route’s inauguration. Even more centrally-located points experienced a notable reduction: prior to completion of the Trans-Siberian, traveling from Paris to Vladivostok required 45 days by ocean voyage (via Marseilles and Suez) on average. After its completion such a trip took only 17 days by rail. Thus by 1910, when the Trans-Siberian and the Seoul–Pusan railway both were fully-operational and the gap between closed by Korean lines joining with the South Manchurian Railway (the former Chinese Eastern Railway Liaodong Branch renamed: a fruit of victory that was transferred into Japanese hands by the Portsmouth Treaty), the day was fast approaching when it would be possible to travel directly from Tōkyō to London on a single ticket by train with only two ferry transfers (the Tsushima Straits service the IJGR had inherited from the San’yo and the English Channel). In April of that year the first formal agreement for a coordinated through-service was made with the Chinese Eastern Railway and the Trans-Siberian beyond that. By March of the next year, through service was inaugurated to the Russian capital, and by May of 1912, there was a coordinated through-service virtually circling the globe, commencing in London, via boat train and steamer to the US and Canada with corresponding express trains, linked to steamship departures bound for Yokohama, where there were waiting trains to link them to the new Korea–Trans-Siberia–Moscow route, from which one could return to London with relative ease. For a brief two-year period the dream of a world-encircling coordinated through-service was a reality—until the outbreak of World War I and the subsequent Russian Revolution interceded to ensure that this vision never developed to its full potential.

When railways reached the town of Kagoshima, they extended the entire length of the Japanese archipelago with the exception of the extreme north, very sparsely-inhabited areas of Hokkaidō. This view shows the Kagoshima freight station and locomotive shed area, just prior to the passenger facilities. Various freight facilities are seen built over sidings, with the large building in the center foreground appears to be a shop or shed facility, as a turntable and water tower can barely be seen to the left of it. The rows of building in the nearer foreground with white-tiled roof edging may be rows of railway workers’ housing provided as an employment benefit.

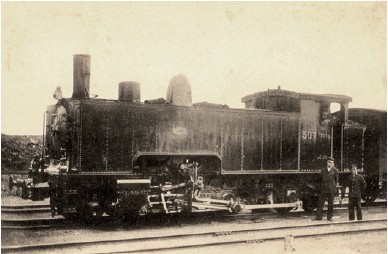

One of the 3950 Class Beyer-Peacock 0-6-2T Abt geared locomotives (sporting running number 507) that were the largest and most powerful locomotives purchased expressly for service on the Usui line and imported from 1898–1908. As the first geared electric locomotives for this line were barely able to cope with the burgeoning demands of passenger services, these stout and sturdy locomotives soldiered on with mundane freight services for some time to come.

In 1910, Inoue Masaru, by then an ailing man of 68 years, was nonetheless eager to promote the potential of this route. Baron Gōtō was actively interested, and gave him the task of studying European railways as a part of the international coordination endeavors then being undertaken, and although ill, Inoue jumped at the chance and took the Korean–South Manchurian–Chinese– Eastern–Trans-Siberian rail route to London; a two-week journey and half the time it would have taken by ocean liner. In the end, the trip was too much for Inoue, and he died in London, although not before having the opportunity for a fitting reunion with such old friends who were still alive from his days as Wild Drinker. In accordance with his instructions, his ashes were returned to Japan, to be interred in Tokaiji Temple in Shinagawa alongside the pioneer Shimbashi line, where his spirit could make sure all was well along the line. On his death, when matters of his estate became public, it was seen that he left only his government pension and a modest home as the bulk of his estate and the falseness of the rumors that had been circulated at the time he had put forth his “Proposal for Railway Administration” and had been pilloried for the alleged act of secretly amassing great wealth just before his retiring from the Railway Agency was proven.

* * * * * * * * *

Also by 1910, when the desire to construct more railways was close to its peak, the cost of developing a railway to main line standards was likewise becoming more costly. As the framework of a national railway system was well underway, with most of the major trunk lines built and the few still needed under construction, most of the new lines projected were short local lines with modest traffic potential. In order to stimulate such lines, the government passed a Light Railway Law, which brought many keiben tetsudō “light railways” into being. Within three years, the effect was notable. By 1913 the number of keiben tetsudō had greatly increased, thanks to the simplified organizational procedures authorized by the new law and other governmental encouragements. As of that year, there were 38 keiben tetsudō with 574 route miles in operation, an additional 44 with a route mileage of 800 miles under construction, and some 126 companies with a combined mileage of 1,953 miles which had received a preliminary charter, but which had not commenced construction. The law would be augmented in 1924 with the addition of a Tramway Law. In all, by the close of the Meiji period, there were approximately 208 such keiben tetsudō contemplated to add some 3,328 route miles to the Japanese railway system. Many of the keiben tetsudō were short, local affairs that acted as branch line extensions from the “main-line” grade shitetsu or IJGR, meandering along old cart tracts or the banks of local streams to bring rail transportation to small towns, remote locations, and otherwise un-served villages and hamlets of the hinterlands. They were often times on the shakiest of financial grounds, operating as it were “on a shoe-string” with second-hand, obsolete equipment purchased used from their more established “main-line” brethren if they happened to be of a matching gauge. Thus they often retained a quaint, nostalgic flavor, often all the more charming due to the hodgepodge of dated and mismatched equipment with which they were furnished.

The immediate effects of nationalization were more evolutionary than revolutionary to the typical traveler. An Englishman, Thomas Henry Sanders, left an impression of traveling over the newly nationalized lines at the very end of the Meiji era in 1912 which varied little in detail from that which Lorrimer had given almost ten years before. The dreaded habit of spreading one’s self out over several seats was still notably prevalent, only by this time, there usually existed a car “boy” on most first class cars who could be pressed into service to dispossess the offending, overly-territorial occupants. Unlike many Westerners of the day, Sanders was not averse to traveling occasionally in third class accommodation, where he sometimes encountered less fortunate Japanese who were taking their first railway journey, distinguished by the manner in which they “sit straight upright and look about them, in the train and through the windows, in a mysterious, awe-struck manner, which they never lose from the time they get in till they get out again.”

The Japanese railway network in 1910, at the close of the Meiji era. Government lines are shown in red and private lines in black. After nationalization, the only private railways consisted of feeder lines augmenting the government system. Railways had been built the length of the archipelago with the exception of the extreme north of Hokkaidō. Least serviced by any semblance of a railway network is the island of Shikoku.

Amenomiya Keijiro (his surname is sometimes also transliterated as Amemiya) was a self-made entrepreneur who had built and lost a fortune selling silkworm eggs to the Italian silk industry, made another fortune in flour milling, and in the 1880s turned his attention to railways. He was an influential and instrumental shareholder in the Kōbu Tetsudō, the Kawagoe Tetsudō, and the company that would build the Tōkyō streetcar system. He also was actively involved in mining, iron works, and steel mill ventures. He established the Amemiya Works, which specialized in the manufacture of narrow-gauge locomotives and rolling stock for the small tramways and light railways that started to appear after the turn of the century. Today he is most fondly remembered for having encouraged country people to build light railways through rural areas to spur modernization and in 1908 he became president of the Dai Nippon Kidō (Greater Japan Tramways), a holding company operating eight such light railways in disparate parts of Japan. Englishmen will recognize in him remarkable similarities to their own Col. Holman Fred Stephens, of whom he is the closest, albeit more successful, Japanese equivalent.

The car boys were well and truly needed on some of these cars. Sanders notes that the average Japanese traveler was a prodigious eater, consuming an amazing quantity of food en route:

“As for the eating, it is perfectly amazing to see what the Japanese can do in this direction. One notices it more in the second-class carriages, where the travellers are well enough off to be able to afford the various luxuries which are sold at all railway stations of any size. A bento, or luncheon box, containing rice, fish, eggs prepared in various ways, bits of vegetable and seaweed perhaps, costs fifteen sen, or three-pence; a pot of tea, with a small cup to drink out of, but without milk and sugar, costs six sen, or a penny farthing, and the tea-pot and cup are all your own! If you already have a pot you can get it re-filled with tea for one farthing. In season, apples and oranges and other fruits are sold. These are the chief things purchased by the Japanese in their travels. At two or three of the biggest stations one may purchase little boxes of sandwiches in foreign style, put up in the neatest possible way, and the box packed solid with them—no deceit! The cost of these is sevenpence per box and it is a very good bargain... At the stations where these various things are sold the vendors walk up and down the platforms, calling out their goods in minor sing-song tones which are rather musical to hear... very strange but very pleasant.

At the various stations large quantities of provender are brought in by the travellers on the trains, and consumed with astonishing rapidity, all the rubbish being thrown on the floor or sometimes out the window. On all the through trains there is a ‘boy’ to every coach, whose main business in life seems to be to go along each coach about every half hour with a broom, to sweep up all the orange-peel, waste paper, luncheon boxes, cigarette ends and other debris which have been thrown on the floor. The coaches are of the long, open type, with seats all down the sides, similar to, but not so comfortable as those on the London Underground Railways... Two long rows of picturesque men and gaily-clad women and children, many of them munching and scrunching... scattering refuse in every direction... It is a fact that by the time the ‘boy’ gets to the end of the car with his broom, it is already time for him to begin again at the other end... In connection with the throwing away the refuse,...one thing that happens quite frequently... is always amusing. The majority of the Japanese have no glass windows in their houses, and, being so unaccustomed to it, they can’t see glass when they look at it. The fun begins when they start throwing things through the window when the window is shut. The expression of utter bewilderment on the faces when the things strike against the glass and come back into the carriage is a joy to behold.

The Japanese know how to make themselves comfortable in a railway train... In the summer-time they usually take off the two outer Japanese garments, leaving only a kimono on; while if they come to the train in foreign attire they will take it off in full view of the public, and put on a kimono... They handle their luggage with the most tender solicitude. If a Japanese [man] gets into a train, and finds only one seat available, it is more likely than not that he will put his bag on the seat and stand up himself.”

Fukushima’s little Shintatsu Tetsudō, opened in April 1908, had only been in existence for some 3½ months before it was merged into the grandly styled Dai-Nippon Kidō (“Greater Japan Tramways”), an umbrella company created in August, 1908 that operated eight unconnected light railways in divergent areas in Japan at is peak. This view shows the line in operation as the Dai-Nippon Fukushima Division. The line ran northward from Fukushima (built along the side of the local road) to a junction in the tiny hamlet of Nagaoka (not to be confused with Nagaoka city in Niigata), at which one branch struck out westerly, again using a local road for a part of its right-of-way, to a terminal at Iizaka hot springs. By 1911 the line had reached Date station (on the former Nippon Tetsudō’s mainline), which is shown here looking northward in the direction of Sendai. Rowland Emmett could not have imagined a more whimsical locomotive, No. 4, (proudly built by the Dai-Nippon Kidō’s Amemiya Iron Works Division) dwarfed as it is by the two tiny, mismatched coaches (Nos. 10 and 3) that follow it. Note the single engine driver/fireman seated in a cab barely large enough to accommodate him, the lack of a uniform coupling height between the passenger cars, and link-and-pin couplers consisting of simple iron bars that look as if they are nothing more than rope. The only brake systems found on the train are the two brakemen riding on the end vestibule of each carriage, ready to crank down the handbrakes at the whistle signal from the driver. Little wonder their “broad gauge” confrères are looking on in bemusement from Date station below as the return train from Iizaka to Nagaoka crosses the bridge.

The local train in this view has just arrived in town: a push-pull service with a diminutive tank locomotive, which almost invariably was an 0-4-0T. A red seal in the original image contains the kanji Yanagawa, the location most likely is Yanagawa, Kyūshū, in which case the line would be the Saga Basha Tetsudō (opened in 1904) at some point after it had purchased steam motive power and changed its name to Saga Kidō in 1911.

In the wake of the Light Railway Law of 1910, the Nishio Tetsudō was chartered to connect the town of Nishio to the closest station on the IJGR Tokaidō line, Okazaki, which is on the approach to Nagoya from the north. It began operations in 1911 on this initial stretch, just over eight miles in length, with four steam locomotives, a dozen passenger cars, 20 boxcars and 29 gondolas, having chosen a gauge of 762mm. This view of the company’s center of operations at Nishio station accordingly shows all types of rolling stock then on the line. The station staff waits as a mixed train of one box car and two passenger cars edges to a stop at the terminus. To an American, the narrow-bodied clerestory passenger cars bring to mind some very similar New England two-foot gauge stock. Note that the company has provided a fairly extensive yard and the roadbed is reasonably well ballasted for a light railway that served a small provincial town, evidencing both the expectation of growth and the commitment to good engineering practice from the start. The expectation was not unfounded. By the time the Nishio Tetsudō was merged with the Aichi Denki Tetsudō in 1925, it had increased its system to just over 16 route miles and added two additional steam locomotives.

This photo shows an industrial railway, not one authorized under either the Light Railways or Tramway laws. Nevertheless, it did carry passengers, as did many of the larger industrial railways off the day. The diminutive train, headed by a German locomotive, is running on the industrial giant Sumitomo’s Besshi Copper Mine railway opened in 1893 in the mountains of Ehime prefecture on the island of Shikoku, near the town of Niihama. The Besshi mine was one of the largest in Japan in its heyday. The railway was built initially to transport smelted copper, then after the smelter was relocated, raw ores from the mine to the coast, and is a prime example of one of the more extensive industrial railways existing during the Meiji era. Around the turn of the century, the company permitted tourists to use the trains to visit the mine.

The 762mm Uonuma Tetsudō opened in 1911 and was in many ways one of the classic and most photogenic of the light railways that sprang up after adoption of the Light Railway Law. This image shows Ojiya station—the line’s terminus for its entire existence—very early in its career, as the platform nearest the viewer has yet to be completed. The Uonuma linked Ojiya with the IJGR’s Hokuriku line a bit over 8 miles away. When the IJGR’s Jōetsu line opened to Ojiya late in 1920, the little railway suddenly found itself without purpose, and it was bought up in 1922.

More than one foreign traveler remarked upon the generally dirty condition of Japanese passenger cars of the day, due in large part to the sentiment of the time that any place where the shoes were not required to be removed was a place not worthy of keeping clean. One American traveler in 1904 noted that the railways had combated the problem of broken window glazing in third class carriages (where the uninitiated were more likely to travel) due to items thrown against windows inadvertently thought to be opened and the ensuing expense and injuries, by dabbing a large spot of paint on all the third class carriage windows.

Sanders also had occasion to take the Shimbashi–Shimonoseki Special Express at the very end of the Meiji reign, and he left an interesting record of travel on the best service the IJGR offered at that time:

“... This new train has been greeted with a tremendous outburst of trumpet-blowing and notes of admiration, and the guide-book seeks to impress you with the glory of the achievement by describing how the ‘country-people gather at wayside stations and look with amazement at the train de luxe passing by at the fearful rate of thirty-five miles an hour!’ The seats are numbered and you can reserve them—very convenient in a country where your fellow passengers are in the habit of piling up portmanteaux on your seat; and the advertisements say that ‘the train is beautifully and comfortably appointed, and the table elegantly served. An observation-car is attached to the end of the train, from which the beauties of the scenery may be admired to the best advantage.’ For all these blessings you pay the sum of ten shillings extra first-class, and six shillings second-class if you travel over three hundred miles; for any less distance it is six shillings and four shillings respectively. There is no third-class de luxe...

When first I beheld it, I couldn’t see anything de luxe about it at all: it goes on the German plan of being very severe outside.3 But on stepping in, I at once saw all those ‘velvet curtains, and other beautiful appointments,’ exactly as reported in the advertisements... There are in Japan a great variety of ornamental woods, and these have been used to good advantage in the interior of the train de luxe. The designs worked by paneling and inlaying with different coloured woods are very handsome.

The only other feature of the train de luxe which attracted my notice was a uniformed individual labeled on his arm-band, chef de train. The chief function of this person appears to be to inspire a sense of security in the passengers of a train which sometimes goes at ‘the awful speed of thirty-five miles an hour,’ for it is impossible to imagine a man of such portentous dignity ever getting wrecked. Another use for him, however appeared during the journey. One merry passenger produced a gramophone and set it going, to the delight of all the others, who crowded round and grinned pleasantly. But the chef de train heard it, and, unable to endure such frivolity on his train de luxe, sternly ordered the machine to be put away.

I took a sleeping berth—bang went another five shillings! It had brown velvet curtains and other luxuries, including a rack big enough to put your hat and collar in, but which was the only place provided for all your clothes. Being a very hot night I had the window down, to the astonishment of the natives, who are frightened to death of fresh air. There was a window screen, supposed to keep out the coal dust, but it didn’t do so. I woke up early in the morning and found my bed thickly covered with fine ashes, which had penetrated to every corner. The supply of coal is certainly luxurious... The sleeping berths in first-class cars are very comfortable, though a little small. Tall people have to do a considerable amount of maneuvering before they can accommodate their length to the space available... I was awakened by an energetic prodding in my ribs and on looking down beheld the train-boy vigourously flourishing his watch at me, and pointing to the time in an excited manner. I looked, and it was a quarter to nine. The boy then motioned me to come down out of it, pointing all around the car to call my attention to the fact that all the other beds were already made up into their day-time style.”

The Great Flood of August 1910 brought exceptionally high water to the Tōkyō metropolitan area and was well-documented. In this view a railway worker wades along to check that all is well just prior to the departure of one of the first trains of evacuees from the Mikawashima station in the aftermath of those floods. This photograph shows the double-roof arrangement of Japanese carriages splendidly, while also illustrating both that brakemen sometimes rode in the carriage to man handbrakes, un-separated from passengers by the luxury of any brakeman’s compartment and that passengers generally could be trusted not to tamper with the hand-brake and interfere with train running when carriages were un-manned. Mikawashima was the second station after Ueno on the former Nippon Tetsudō Jōban line that had then recently been brought under the aegis of the IJGR by nationalization.

Sanders was less enthusiastic about the sleeping accommodations on other trains:

“On main-line trains the second-class berths are very similar; but on some of the lesser trains they have an arrangement which I have never seen anywhere else. Part of the seat is pulled up to support your back, and part is let down so as not to support your legs; and there you are, half sitting and half lying in a sort of very uncomfortable deck chair, with your legs under the seat of the man in front of you. Where they got the proportions of this contrivance from I cannot imagine: no single part of it is adapted to any human body that I ever saw. The back is exactly the correct height to make it impossible to find a resting place for your head; the accommodation for your legs is so cramped that you are continually hitting your shins against the next seat, and, worse than all, the seat is not wide enough to hold you securely, so that if by any miracle you do lose consciousness sufficiently to doze off for a few moments, you will probably slide off, and wake up to find yourself huddled up under the seat in front, in dark, narrow, dirty confinement. You spend the whole night in pulling yourself up from this predicament. The charge for this luxury is one shilling; and, at the same rate, it is worth about ten shillings to keep out of it.”

Slightly beyond Mikawashima on the Nippon Tetsudō Jōban Line were four bridges that carried the railway over the Sumida, Ayase, Naka, and Edo Rivers. In this pre-nationalization view, a British 4-4-0 lumbers slowly along with a Nippon Tetsudō freight train over the Sumida that was one of the sources of the flooding shown in the prior photograph. The bridge itself is a good example of the British-inspired wrought iron designs of mid-Meiji.

Senju station (now Kita-Senju), on the former Nippon Tetsudō Jōban line, is shown in this 1910 view as the floodwaters recede. Senju was also the first terminus of the Tōbu Tetsudō, where its mainline would eventually cross the Jōban line on its approach to Tōkyō. Note that the earliest end-platform style carriages, first imported for the Shimbashi line in 1872—a design very quickly abandoned—are still in use on this IJGR train. By the time of the flood this design was almost 40 years old.

Further downriver, Kinshicho station on the recently nationalized Sōbu line is shown while still inundated up to platform level. The mainline of the former Sōbu Tetsudō is to the right, passing under the passengers’ overbridge, while the boat from which this photograph was taken is floating over the station sidings, evidenced by the idle strings of freight cars standing at the left. The platform’s small kiosk or waiting room can be seen in the middle of the view. Kinshicho originally was named Honjo when it opened in 1894 and was the first Tōkyō terminus of the Sōbu.

The narrow strip of land between the Sumida and Naka rivers was among the worse affected areas of the 1910 flooding. Kameido station on the former Sōbu line laid just to the east of Kinshicho and is shown in this photograph. Daily business is returning to normal as a former Bōsō Tetsudō Krauss 0-4-0T tank locomotive, now carrying running number 14, is set to depart with a mixed train. Only the bare-chested yardsman is concerned enough to pose for posterity; the literally higher-placed station staffer in full uniform is too busy for such pleasantries and turns his back on the scene.

Perhaps Sanders had, in these seats, unknowingly encountered the design inspiration for future economy-class airline reclining seats. Another American traveller recorded the fare from Yokohama to Pusan, Korea on the Shimbashi–Shimonoseki Special Express as costing US $14.25 (including ferry passage to Korea) with a sleeping car surcharge of $1.25.

Along the Sea of Japan coast, work on the San’in mainline was progressing, and in 1911 the notable Amarube Viaduct was completed. The viaduct was built of 943 tons of steel trestles, roughly two thirds of which were from the US and one third of which was domestic, thanks to new steel mills such as Yawata and Wanishi that were starting to come on line. At 310 meters long and 40 meters above the floor of the valley below, on completion it attained iconic stature in its day, becoming the most celebrated railway viaduct in the realm. It was Meiji Japan’s Kinuza or Garabit.

The IJGR’s Amarube Viaduct, on what is now the San’in Line, was completed in 1911. The postmark of Taishō 6 (1917) dates the view to the first six years of the viaduct’s existence. The scene today is little changed from the view shown here, but for the addition of a few modern buildings in the village below.