FOR MY SINS, I HAVE A REPUTATION AS AN ECONOMIC FORECASTER. AND so this chapter looks at the future of inequality and of poverty over the next 25 years.

The most important feature that we are likely to see over this period is an enormous pace of change. We are at the cusp of 12 major technological changes that will revolutionise economies and turn many upside down.1 I focus here on three of these changes because I’ve studied them in detail, though there is nothing in the others that suggests that they will have essentially different impacts economically.

Autonomous vehicles are about to transform transport. At this stage it looks as if the outcome will be something like the Uber model without the driver. This will remove large parts of the two main costs from car/taxi usage – the cost of car ownership and the cost of the driver. So the cost of personal transport could collapse, quite apart from the likelihood of cheaper renewable energy.

One imagines that autonomous vehicle technology will take off more quickly for freight and vans than for taxis, but eventually the changes must be dramatic. These will be especially important from 2030 onwards.2

The second change is robotics. This is transforming production. The combination of robotics and 3D printing means that factories can be decentralised and nearer to the customer. Adidas have already started the trend, opening new factories in Germany and the US 20 years after pulling out of both locations. Beefeater Gin is one of the world’s bestselling gin brands. Only five people work on the production line in the heart of London that produces more than 25 million litres of gin a year and serves the entire worldwide market. This will ravage manufacturing jobs, especially in emerging economies.

The third is blockchain technology. This means that linked computers automatically maintain records and cross-check everything, rejecting any data which is flawed. Once participants can be assured that no suspect transaction has taken place, commerce can take place in real time and you no longer need armies of professionals in the middle following up and checking before anything can proceed.3

Management consultants McKinsey have said that one company in five is using a business model that will fail in the next five years. The speeding up of corporate lifespans has already been happening for some time: ‘The average lifespan of a company listed in the S&P 500 index of leading US companies has decreased by more than 50 years in the last century, from 67 years in the 1920s to just 15 years today, according to Professor Richard Foster from Yale University.’4 And from the UK fewer than 10% of the companies in the original FTSE100 list from 1984 remain in the list today (although some are parts of other companies in the present list). As the brilliant economic commentator Anthony Hilton says: ‘Think about it: 90 per cent of our biggest companies have gone within a generation.’5

Moreover the IT changes that I have pointed out are probably just the tip of an iceberg. And as my previous book, The Flat White Economy, showed, many of the existing technologies currently in use are far from maturity. One would have to be both arrogant and stupid to think that one can foresee the future in detail given this.

But it would be equally stupid not to think about what might happen and at least speculate about likely future changes. The key thing is to have the humility to accept that one might easily be wrong and to keep looking out for signs that one has made a misjudgement.

The latest data shows that in most countries the peak in inequality has temporarily passed, other than the continued growth in income of the very rich. Even the number of dollar billionaires plateaued in 2016. The ‘perfect storm’ of inequality being caused by technology, globalisation and exploitation looks to have blown itself out a bit as bankers’ pay falls and the stock market starts to rein in CEOs’ pay. This phenomenon could well continue for the better part of a decade or more.

Looking at countries from 2008 to 2018 on Cebr’s World Economic League Table, China is forecast to have a doubling in GDP; India’s GDP is forecast to grow by roughly the same amount.

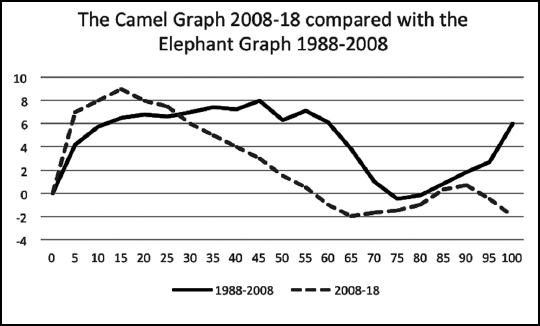

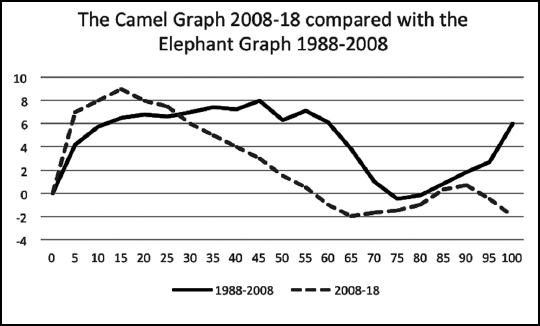

Figure 13. The camel graph 2008-18 compared with the elephant graph 1988-2008

Note: this graph shows the annual increase in income for each 5% group of the world income distribution starting from the lowest point.

Data source: Milanovic, op. cit., for 1988-2008 scaled into line with real income growth for the relevant period; Cebr World Economic League Table 2008-18; details of the calculation in the text.

Because the income data for 2008-18 does not exist, I have constructed an impressionistic series based on three assumptions. I have used the country GDP forecasts and estimates to produce a first round estimate, using GDP as a proxy. The GDP growth has been adjusted to take account of the differential growth of incomes from GDP for the ten main economies and this ratio has been proxied for the other economies. For these ten main economies I have then made assessments of the distributional changes using the data available. Again I’ve assumed that countries in similar income categories have had similar changes. It is all very rough and ready and I would not call this particular exercise scientific, but it suggests what appears to be happening now; which is much the same as Milanovic calculated for 1988-2008 but the shape of the graph is more like a camel (technically a dromedary since it only has one hump) than an elephant. I have scaled the data to allow for the different periods involved to try to make the shapes more comparable with each other. This is a fairly messy and impressionistic exercise and I would be happy to defer to someone with the time to concentrate on replicating the work with greater accuracy!

The real difference between the two periods is that whereas inequality increased within countries until 2008 even when it was falling between countries, in the post-2008 period inequality has generally been falling within countries as well as between countries. This is because of the impact of the financial crisis on the pay of top executives and bankers, although pay of senior entrepreneurs in emerging markets has burgeoned.

The peak of the income growth is lower down the distribution as lower middle income economies like China have slowed down while poor countries like Bangladesh have accelerated. The trough of the income growth slips down as the worst-off people in Western economies (who are still the main people who suffer from globalisation) slide down the income distribution scale). And the richest two groups (although probably not the super-rich) fell back because of the collapse in bankers’ pay over this period.

This produces an elephant graph that looks much more like a camel or a dromedary.

However, at some point it seems likely that this fall in inequality is likely to come to an end. This is because technology is just about to become the driving force in causing inequality. With my background as IBM Chief Economist (in the UK) I’ve been worrying about this for about 30 years, and one of my Gresham lectures explicitly focussed on the problem.6 More recently the sadly deceased Sir Anthony Atkinson’s last book, Inequality: What Can be Done?, makes the point that (quoting research driven by David Autor and his colleagues7): ‘by allowing technological change to affect differentially not only different tasks but also the capacity of workers of different skills to undertake these tasks and the productivity of capital in these tasks, they argue that there has been a displacement of medium skill workers by machines in the conduct of routine or codifiable tasks.’8 But that part of the increase in inequality that is driven by technology is likely to continue to grow – probably much faster than hitherto – unless the nature of technological progress changes.

So far we have seen just the tip of the impact of technology on inequality. The so-called fourth industrial revolution is likely to have effects completely different from the past three. The first three industrial revolutions were characterised by three factors:

(1) Although labour was replaced by machines, since labour was used to build the machines the net direct impact on demand for labour was partly cancelled out. Now in the fourth industrial revolution, machines will largely be built by other machines.

(2) Past changes happened incrementally. Now that the cost of robots has dropped below the tipping point of around $15K, change is happening on an almost vertical curve. Even in China it is now economic to replace human labour with robots, much more so in countries with higher wages. The result is that this change is likely to be much more violent and disruptive than previous changes.

(3) The marginal product of labour in previous industrial revolutions was well above subsistence level or the benefit level or the minimum wage if it even existed. So even if it was pressed down temporarily (e.g. the impact of the first industrial revolution in the UK), it didn’t make work uneconomic.

Now, as a result of the past downward pressure in many countries, the marginal product is already quite close to the floor for wages. If the increased short-term pressure from technology pushes the marginal product to a level close to or below the minimum wage or the effective minimum wage set by the level at which benefits are paid, it is likely that, rather than simply leading to greater inequality as did past technological changes, the latest changes will lead to actual loss of jobs.

Although in the very long term jobs will probably reappear provided labour markets are flexible, because of hysteresis (the tendency for skills and abilities to atrophy when people are out of work for a sustained period) it could take a long time for this to happen.

And of course in many countries labour markets are not flexible, with minimum wages or benefit levels set too high, and this could mean that people escape from the labour market completely. If they do so, there is some evidence that it is very hard to bring them back in. ‘A recent national analysis by the Oregon Office of Economic Analysis found that the long-term unemployed are around twice as likely to drop out of the labour force as to find a job’.9

Because of this it is likely that unless welfare and minimum wage regulations are reformed, technology could lead to a substantial redistribution of income to the already well-off groups.

It is of course worth noting that not all the jobs disappearing as a result of technology are low skilled. Many relatively highly paid jobs in finance and professional services (perhaps even economists!) are also at risk.

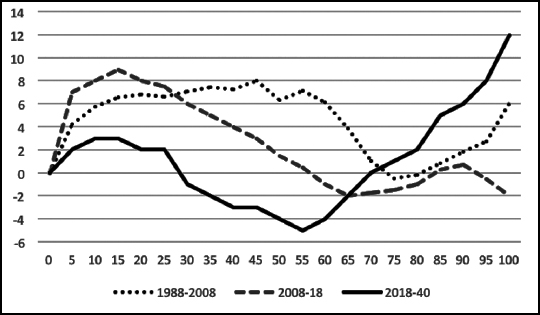

The graph shown in Figure 14 for 2018-40 gives an impression of what might happen – some of the laggards in globalisation (in countries in Africa and parts of Asia especially) still catching up and helping the incomes of the poor to do better than average, the bulk of people who currently have relatively low-skill jobs in Asia, Europe and the US finding that their real incomes go down, while the richest 25% do even better as they reap the benefits of technology.

The elephant, having transformed into a feeding camel, transforms again into a striking cobra.

But of course we really do not know exactly how technology will drive inequality. And it is not certain (the purpose of making many forecasts is to prevent them coming true – if you predict that something unpleasant will happen it makes sense to try to take steps to avert the predicted result even if it means that your forecast will be disproved).

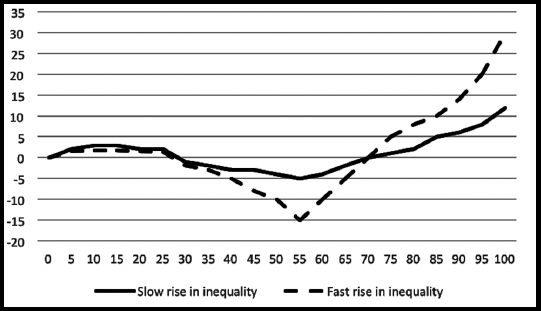

Figure 15 shows different possible cobra graphs for the changes in income for different income groups over the period to 2040. One supposes that technology has an impact on equality on about the same scale as the industrial revolution; the other that the impact is roughly twice as strong.

The policy implications of the different trends are considerable. If the underlying trend is that suggested by the more moderate change (which seems more likely but is by no means certain), it ought to be possible to contain some of the most damaging impacts of rising inequality by the policies set out in this section. But if the underlying trend is more dramatic, as suggested in the cobra graph with the faster growth in inequality, then there is likely to be a requirement for a much more radical approach. I discuss this in the final chapter of the book.

The huge reduction in extreme poverty from the 1980s and the concomitant improvement in so many other indicators such as infant mortality, deaths from malnutrition and life expectancy came largely as a result of economic development.

It is important to note that aid and charity did little to assist the reduction in poverty over this period, though both had a substantial role in causing some of the worst aspects of ill health to diminish. As pointed out before, this book’s title, ‘The Inequality Paradox’, comes from the fact that the period of most rapid growth in inequality in the wealthy economies coincided with the period of most rapid decline in poverty in poor countries. Rises in inequality and in poverty don’t go together.

The reason that aid and charity played a lesser role in reducing extreme poverty in the recent past is that in the 1980s most of the extreme poverty that existed at the time largely reflected lack of economic development. Even now there is some continuing poverty from this source and it is likely that the development of countries in Africa and Asia in the coming years will reduce this poverty to low levels. But lack of development is not the main source of extreme poverty today.

Figure 14. The cobra graph 2018-40 compared with the elephant graph 1988-2008 and the camel graph 2008-18

Note: this graph shows the annual increase in income for each 5% group of the world income distribution starting from the lowest point. Data source: Cebr World Economic League Table, details of the calculation in the text.

Figure 15. Different potential cobra graphs for 2018-40

Note: this graph shows the annual increase in income for each 5% group of the world income distribution starting from the lowest point. Data source: Cebr World Economic League Table, details of the calculation in the text.

Every year my consultancy Cebr produces a World Economic League Table showing how GDP throughout the world is changing and is predicted to change. The 2018 edition produced in conjunction with the construction consultancy Global Construction Perspectives (GCP Global) shows which are the poorest countries in the world.10

Bangladesh is one of the poorest of larger economies and it is expected to be particularly fast growing in the coming years. The 2018 World Economic League Table predicts the GDP growth rate to average 7.0% from 2017-32. During that period it is predicted to rise from the world’s 43rd largest economy to the 31st largest.

What the analysis shows is that there is a correlation between a current level of poverty and a forecast of rapid growth.

Of the absolute poverty that still exists, about half is in a range of 22 poor countries.11 The good news is that most of them are now forecast in the World Economic League Table to be either already growing fast or about to start to do so.

Those countries where growth is forecast to remain low largely are predicted to be affected by problems of governmental failure or by conflict. Clearly the problems of poverty resulting from these countries is a function of a more complicated problem than simply lack of the appropriate economic structure. It would be unrealistic to expect poverty to end until the political problems are fixed.

There is a separate problem of poverty for excluded groups (in some cases self-excluded). Alleviating poverty for these groups is likely to require direct intervention to deal with the root causes of the problems. One interesting example which is attracting particular attention is the Icelandic approach to reducing drug taking amongst teenagers.12

In Chapter 4 we saw how social cohesion is suffering in ‘middle America’ where white working-class men in particular are starting to feel excluded, leading to increasing suicide, opioid addiction and falling life expectancy. The issue of inequality needs to be understood as not purely a financial problem.

This type of poverty, of excluded groups in the Western world, has been on an increasing trend. Demographic pressures could intensify this. So unless social policy and welfare policy can reverse the trend it is likely that this problem will increase.

The impact of technology on market structure and inequality

Earlier in the book I described how one of the world’s richest men, Carlos Slim, made his money from his position as the owner of the mobile phone network in Mexico.

One of the increasing problems caused by technology is its tendency – unless public policy is designed to prevent it – to monopolise its sectors. Examples such as Intel, Microsoft, Apple, Google and Amazon abound.

I first developed the underlying economics when I worked for IBM (not that the company was particularly pleased with my analysis since it was frightened that this could be used against the company in antitrust cases – I riposted by pointing out that the era of IBM being a major antitrust target was now history and that the latest IBM profits results in the late 1980s hardly pointed to monopolistic profits).

The analysis shows that one of the most crucial economic factors in the success of the digital economy is huge economies of scale – what I call ‘supereconomies of scale’. The concept of economies of scale developed at the beginning of the industrial era. The concept is mentioned in Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, where he points to economies of scale resulting from the division of labour. The concept has typically been associated with the intensive use of machinery, whereby long production runs of a commodity reduce the unit cost of producing that commodity.

But in the information era, where the product is not a physical one, the achievable economies of scale are much greater. The underlying economics of information were described in Nobel Prize-winner George Stigler’s seminal article in 1961.13 Typically an item of information is expensive to research and develop but can be replicated through dissemination at virtually zero cost. To give one example from my book The Flat White Economy, it is widely believed that the 1990s version of Microsoft Windows (3.0) cost about $550 million to develop. But to create an extra licence cost only a small administration, packaging and copying fee of a dollar or two at most.

At the time an operating system like Windows typically sold for about $70. So had Bill Gates only sold a million licences, he would have been sitting on a big loss – of nearly $500 million. But he didn’t, of course: he sold about 10 million licences in the two years before Windows 3.1 was released and ended up with a substantial profit that changed the future of his company. By the time of Windows 7 and Windows 8 the typical first two years’ sales of a Windows version were about 200 million licences.

So it is important that for the digital economy, sales on a huge scale are necessary to amortise research costs – even sales of as much as a million, which would be a signal of success for many products – would be unprofitable. This means that companies tend to delay the investment until they are certain of two factors working in their favour: firstly, that sales will be on a sufficient scale to enable them to make a profit; and secondly, that there will not be so much competition that they will be forced into a price war. This takes time (although sometimes the desire to keep ahead of competition will encourage companies to bring forward innovations). In my experience, supereconomies of scale have tended to mean that large changes tend to be delayed while incremental improvements tend to be accelerated to keep ahead of competition and generate product differentiation.

The other economic factor that affected the timing with which the digital economy bore fruit is its sensitivity to network effects. Network effects are a phenomenon common to communications systems. Essentially, the value of a network to an individual participant in that network increases with the number of participants in it. So a single telephone is of no use on its own – it gains some value only when there is a second phone (one often wonders who bought the first phone!) – and the value increases with the number of other phone users with whom one can be connected.

And as the value of each phone increases, the more phones tend to become available to contact on the network, until there are so many other connections that the value of an additional connection is negligible. Network effects were first developed as a concept by the President of Bell Telephones in making his case for a monopoly in 1908, but the ideas were developed and refined in the 1980s and 1990s. Robert Metcalfe, one of the co-inventors of the Ethernet, was the progenitor of Metcalfe’s Law – that the value of a communications network varied with the square of the number of connections in the network. This idea was vigorously promoted by the economic guru George Gilder during the 1990s.14

The Nobel prize-winning economist Sir John Hicks (one of the all-time economics greats) warned in 1939 that increasing returns would lead to ‘the wreckage of the greater part of economic theory’.15 In fact it is not quite as bad as all that and modern mathematical techniques can now rescue much of economics from this fate.

Where there are network effects, investment typically doesn’t take place until there is a critical mass of potential users. Network effects tend to cause investment to be held back in a similar fashion to supereconomies of scale, although in the case of the latter, the tendency to delay investment is moderated by the possibility of gaining first-mover advantage. It was the combination of supereconomies of scale and network effects that meant that the economic exploitation of the digital technologies took place on a different, tardier timetable than that which had been predicted by those who understood only the technological issues.

But there is a problem with pricing under both network effects and supereconomies of scale. The problem comes from the established economic theorem that with competition the tendency is for prices to be reduced to the marginal cost of production. Now this works fine if the marginal cost is above the average cost of production, since producers can still make a profit. But with both network effects and supereconomies of scale the marginal cost is well below the average cost. So production would be at a loss in conditions of competition. That is why it is difficult to achieve competition in such industries.

One of the consequences in the real world is the persistence of monopoly in technology industries, including the examples cited above. There tends to be a battle between innovation which makes the monopolies obsolete and the market power of the incumbent which tends to reinforce monopoly.

Since many of the world’s richest people have fortunes based on monopolies, it is important to prevent monopolistic excesses which reinforce inequality, and to police anti-monopoly policy carefully.

Monopolies boost inequality in a number of ways. First, wealth and income are concentrated among a small group who can gain extreme wealth from their monopolistic control of key elements of technology. Second, there is a tendency for the potential beneficiaries from this in areas where the rule of law is weak to abuse their wealth to secure political favours to support the continuation and protection of their monopolies. Third, the monopolistic power enables them to ramp up prices in such a way to affect adversely the costs of living of the poorest groups and hence their standards of living. The analysis in Chapter 15 shows that the poorest groups spend proportionately most on mobile phones (a full 7% of the income of the poorest decile in the US – more than a third as much as they spend on food!) and this is one of the areas most subject to monopolistic pressure in emerging economies.

I am assuming and proposing that going forward, there will have to be very much more emphasis on anti-monopoly policies to prevent exploitation than there has been in the past. If not then it is likely that there will be an even greater growth in inequality as a result of technology than might otherwise be predicted.

Besides technology, the other factor that is likely to come to the fore in pushing levels of inequality in the future is homogamy, the tendency for people to marry people of similar background. This reinforces the continuation of privilege through the generations as was explained in Chapter 10.

In the Western world, the proportions at university (which probably are the most important causes of homogamy) have probably matured and will only rise marginally if at all. But the effects of generations of meritocracy on entrenching both poorer cohorts across the generations and also the richer cohorts could build up over time.

Meanwhile in emerging economies it is far more likely that there will be continued growth in homogamy producing even more ‘superbabies’. The stories of the ‘tiger mothers’ from East Asia are well documented examples.16

Conclusion

Looking forward, the most likely conclusion is that the forces driving inequality will change. Overpaid bankers and globalisation will diminish in importance while technological inequality and ‘superbabies’ will take their place.

With technology’s inherent tendency towards monopoly, it is clear that anti-monopoly policy will become increasingly important as we try to prevent the technology giants from unduly exploiting us. And we will have to try even harder to concentrate educational resources on those with the least privileged background.