Emerging strategy, justification and capability

Key points

■ Not every idea is a project

■ Separating strategic initiatives (projects) and BAU (operations)

■ Conducting a SWOT analysis

■ The eight-stage change-management model

■ Numeric and non-numeric project justification models

■ Project justification with numeric and non-numeric models

■ Developing the business case

■ Separating projects, programs and portfolios

■ Organisational project management maturity

■ Individual project management competence

■ Project management organisational structures

■ The role and application of project governance

■ Culture and its organisational impact

In practice

Have you ever worked on a project (in any capacity) and wondered why the project got the green light to begin with? Or worse still, have you been on a project that should have been stopped, but for some inexplicable reason remained on life support long after its ‘use-by’ date? Or one that continued to change from one requirement to another with few, if any, checks and balances in place to ensure that the changes were in fact feasible in the first place?

We all know and relate easily to these types of projects and the countless other examples out there of projects that have been developed and executed with little justification, alignment or direction, let alone with control and accountability measures in place. The obvious question must be: Why does this happen? With industry literally awash (or perhaps even adrift) with notions such as organisational excellence, quality management, best practice, frontline management, mergers and acquisitions, workplace competency, organisational capability, risk management, human capital, knowledge management, corporate governance and the increase in regulatory compliance, how is it that some projects can still be found stumbling and bumbling around the landscape? And remember, the birth rate for projects is increasing exponentially every day, as more and more organisations rush to confer project status on each and every seed of an idea.

Reflect on your organisation and examine where the migration trail might be that takes each idea and critically assesses it against some justification criteria while it is still an idea or proposal. How does it become project worthy, who makes that decision and why? And once a project is confirmed, find out who will ensure it stays on track on any number of agreed performance criteria—for example, schedule, budget, scope.

Chapter overview

Anyone can have an idea, although an idea by itself doesn’t automatically qualify to become a project. This is why some organisations have ‘idea registers’ where staff can readily post their latest and greatest ideas. Then management investigates the ideas, culls some, postpones others and may even give a few surviving ideas ‘legs’ and invite the owners to put forward some further clarification and possible justification.

Ideas are linked to change, change is linked to strategy and strategy is linked to both project and operational work. Not quite a vicious circle, but clearly a ‘justification’ overlap exists, if not a competitive (and at times conflicted) dilemma as to where the priority should be. Or can project and operational work be delineated clearly and managed cooperatively within the project organisation, and between both the operational and project agendas? Then there are the issues of classifying projects and determining what the dividing criteria should be, as ‘one size’ doesn’t fit all.

At their heart, projects should support and demonstrate the strategic direction and dialogue of the organisation. Through a change-based process, ideas get justified and become projects, and then get planned and managed to deliver results—although not everyone climbs on board at quite the same pace (many people are, in fact, change averse). The progression through this process may also be influenced by existing levels of capability (both individual and organisational) and inherent governance protocols framing the project over time.

Isn’t change awesome? In fact, it is the only constant we have.

Escalating thought bubbles to projects

As you read in Chapter 1, why is it that someone’s thought bubble can quickly become another’s project? The idea, the suggestion or the initiative (whatever it is called) ‘magically’ gets clothed in project management speak, and another project lands on someone’s desk. So project management continues to grow on a number of levels: as a ‘body of knowledge’, as a discipline and as a scalable methodology. Much of this growth has been driven by academic research, industry application and feedback, published papers and conference presentations, together with a move towards global standards.

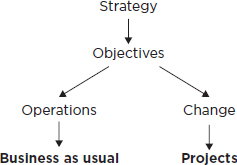

As highlighted in Figure 2.1, are these projects strategic imperatives driving through organisational change in some format or other? Or are they operational priorities, or business as usual (BAU) activities that will impact parts of the organisation? Is there an overlap between strategy and operations that assists in project planning and management, or are they disparate functions? And what of the justification criteria: are projects randomly created and scheduled, or is there some implicit process complete with a justification narrative driving their point of origin?

Figure 2.1 Deconstructing strategy

Within this research, development and growth, a new lexicon of project management-related terms begins to filter through, including: strategy, value management, investment, governance, integration, project management office (PMO), stakeholder management and project maturity. Be they a unique discovery, a value-added proposition or simply an attempt to overlay one body of knowledge with another, they each present an opportunity to more closely examine the natural linkages between the organisation, people and processes, and the projects undertaken. Equally, they highlight the direction and some of the additional challenges and benefits that need to be clearly assessed and communicated as the project footprint extends. Some serve as useful signposts to the organisation, providing the right justification and direction; some signal caution, assessment and review; while others encourage the development and demonstration of best practice and ongoing continuous improvement.

Consider for one moment exactly what is at risk here. A small leap of faith should convince you that the project’s success or failure is directly linked to the project organisation’s success or failure. The ‘lost’ investment dollars injected into the project failure alone could potentially cripple the organisation financially, not to mention possible lost market credibility. And the cost is not just tied to financial interests. Resources assigned to projects that are not viable represent a gross misuse of people, equipment and infrastructure that may already be stretched to the limit across a number of projects. Add to this morale problems, functional loyalties and communication bottlenecks, and suddenly poor project-selection techniques appear almost criminal (a little exaggerated, perhaps, but it does make the point).

Add to this the time wasted in meetings, inspection and reporting processes, the procurement rules that ended up being overkill, the project stakeholders that have lost their professional credibility and the loss of confidence throughout the project organisation. It isn’t a pretty sight. Think of the project-selection requirement as one of aligning the project’s results with the project organisation’s future—both must be intertwined. With finite time, budget, scope and resources, it may not be an option for an organisation to pursue every project that comes its way. Some will get the nod, some will get postponed, while others may get the chop. And each of these decisions can be documented, justified and actioned without the risk of any other potential damage to the project and/or the project’s organisation through poor project-selection techniques.

Then there is the question of priority. As crucial (and hopefully obvious) differences exist between urgent and important work, not all work can be scheduled at the same time. Multiple projects, operational work and competing resources make for a priority challenge regarding what gets done first. Perhaps a PMO holds the answer, or the maturity level of the project organisation itself. And don’t forget the primacy of operational managers and their own priorities.

Regardless of the organisation, they have one thing in common: survival (note, however, that there are degrees of survival, depending on how it is measured—for example, by profit result, market share, product diversity and so on). Every organisation in the private, public and not-for-profit sectors develops and communicates ‘survival’ strategies that may be framed around market positioning, revenue growth, competitive advantage, shareholder return, regulatory compliance, return on investment, global domination or whatever their particular focus is. And with survival comes change—from where the organisation currently is (known as the ‘current state’) to where it would like to be in the future (known as the ‘future state’). In short, projects are all about change, both in a physical deliverable sense of the word and in the expectations of the stakeholders that also change. In other words, project management is about facilitating change and moving organisations, people and processes from the current state to the future state.

The role of an inspiring strategy

Anything to do with management involves a dynamic and often constructed mix of both scientific principles (some mandated) and other more discretionary and personal input (known as the ‘art’ part). Strategic management is certainly no different. While this text refrains from becoming a book on strategic management (or operational or change management), in order to ensure that all projects are aligned strategically to the needs of the organisation, we need to begin our journey by defining strategy, strategic management and the overall framework it presents. Having done that, we can then move on to justify the change process needed to deconstruct strategy into projects.

It should come as no surprise that everyone has their own definition of strategy. PMBOK gets in on the game with its reference to a project being the delivery vehicle through which the organisation’s strategic plan is achieved. Perry, Gibson and Dudurovic (1992) define it as ‘a comprehensive and consistent pattern of decisions and actions…to gain a competitive advantage’. A variation on this is offered by Newman, Logan and Hegarty (1989), who acknowledge strategy as a vital management tool used by senior managers to shape the future course of their organisation. Irrespective of the subtle variations cited, it is clear that strategy should deal with or do the following (although feel free to add your own suggestions):

■ involve corporate management

■ identify and exploit differential strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats

■ be future, value and results oriented

■ be integrated organisation wide

■ provide coherence and momentum

■ be qualitative in design

■ have a ‘relative’ long-term focus

■ target action-oriented, measurable activities.

The notion of an inspiring strategy is fundamental to designing the future for any organisation, as it lays the pathway to the ultimate and desired end point (Cole, 2010). Integral to this is the prerequisite that the organisation creates and delivers sustainable value for its stakeholders. Irrespective of which terms are used—values, vision, mission—strategy sounds important. Now let’s turn to defining strategic management, and in doing so get closer to our goal, in this section, of aligning strategy and projects. In its most basic form, strategic management manages the organisation’s strategy through its formulation, implementation and, one would hope, evaluation stages.

Much like a project management life-cycle, strategic management evolves through a number of predefined stages, guiding and integrating the organisation as it operates within its continually changing environment (both internal and external). Pearce and Robinson (1994) also provide a useful, although conceptual, definition that identifies strategic management as ‘the set of decisions and actions that result in the formation and implementation of plans designed to achieve a company’s objectives’. Yet another (notably more comprehensive) definition is put forward by Stoner, Collins and Yetton (1985), who suggest that strategic management is ‘a process of selecting an organisation’s goals: determining the policies and strategic programs necessary to achieve specific objectives en route to the goals; and establishing the methods necessary to ensure that the policies and strategic programs are implemented’. In other words, strategic management is a formal and integrated process that identifies, communicates and measures change over time. For many, those changes will either add or subtract from the organisation’s triple bottom line: the economy, society and the environment.

One of the common tools when working with strategic analysis (and the ensuing decisions) is the popular strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) grid. Essentially comprising four quadrants, the SWOT analysis compels the organisation to move beyond mere navel gazing, favouring its sacred cows (pet projects) and a preoccupation with its own marketing collateral in focusing its analysis both internally (what can be controlled: strengths and weaknesses) and externally (what can’t be controlled: opportunities and threats).

The organisation can continue to practise and build on its strengths over time as they represent what the organisation does well. Any of the following could constitute strengths internal to an organisation:

■ proprietary expertise

■ product/service knowledge

■ workplace location

■ internal communications

■ innovative practices

■ excellent staff

■ effective marketing strategies

■ efficient production.

Weaknesses also remain internal to the organisation, as they are under its control. Examples include:

■ dated market research data

■ manual record-keeping processes

■ cash-flow problems

■ high rates of staff turnover

■ a limited product/service range

■ a remote location

■ inefficient operating practices

■ poor management.

Opportunities and threats are both external to and beyond the control of the organisation. With opportunities, the organisation can build on or take advantage of any of the following examples:

■ a loyal client base

■ increasing market demands

■ few competitors

■ economic prosperity

■ seasonality

■ market trends.

The challenge for the organisation is to minimise threats wherever possible, including:

■ increased competition

■ falling demand

■ economic downturn

■ rising interest rates

■ political policies.

The SWOT analysis can be used in any number of situations, including strategic analysis, portfolio alignment, project assessment and justification, competitor analysis and/or where any comparative assessment has to be made. A suggested format for the SWOT analysis is provided in Figure 2.2.

Critical reflection 2.1

Conducting a SWOT analysis is never a one-off activity, as the internal and external factors impacting any organisation remain dynamic and fluid at any given time.

■ Identify what the strengths and weaknesses are for your organisation.

■ Develop strategies to maximise the strengths, and to reduce (or remove) the weaknesses.

■ Similarly, identify what the opportunities and threats are for your organisation.

■ Develop strategies to maximise the opportunities and to reduce (or remove) the threats.

■ How does this SWOT approach assist in your ability to plan and manage your projects?

Revisiting operational reality

While little is certain in life, the work environment will inevitably continue to change. Regardless of the driving forces—climate change, economics, social pressures, politics, technological enhancements, consumer demand, global competition or increased regulation and compliance—new workplaces and new workforces are changing the traditional operational footprint within organisations.

While strategy identifies the road (direction) the organisation wants to take, the task of navigating that road becomes the operational reality. New terms—goal, objective, target and activities—enter common language as operational management becomes the successor to strategic planning. Considered by some as the ‘backwater of corporate activities’, managing functional or work-unit level operations on a daily, weekly or annual basis is essential to lift the productivity of the organisation—the true measure of how well operational areas perform. This performance is often measured against a number of planning, monitoring and reporting techniques, with the two most notable being budgets (numeric plans) and schedules (timeline plans).

Table 2.1 provides an example of possible criteria that could be useful in differentiating operational reality and strategic initiatives. While the suggestions are not meant to be exhaustive, they are reasonably comprehensive in providing you with a ‘line in the sand’ with which to make this crucial decision.

Another way to get your head around what operational work involves is to examine it from a management perspective. What is it that operational managers do that strategic managers don’t? Possible answers lie in the points below, suggesting where the focus of the operational manager and team should be. Adapted from Cole (2010), these are aspirational and educative in nature, and not exhaustive or prescriptive, so you certainly have discretion regarding how you apply them and in the amount of information and detail you capture:

■ Practise and reflect proactive management, not reactive management.

■ Encourage management by exception, reporting only on important deviations.

■ Involve an iterative process of moving, changing, revising and updating.

■ Set a projected course of action aimed at achieving future goals, vision, mission or strategy through providing clear objectives, with activities mapped against these so they can be realised effectively and efficiently.

■ Communicate what is to be done, why it is being done, who is to do it, where it is to be done, when it is to be done, how it is to be done, how it will be monitored and how it will be measured.

■ Evaluate against objectives that are SMART: specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and timeframed.

■ Crystallise your thinking: follow the verb–what–why formula (e.g. ‘to develop and implement a plan to increase alternate funding sources by 25 per cent to reduce reliance on government funding’).

■ Circulate precise, concise and flexible documents that can be understood easily, implemented and managed—not vague statements of intent.

■ Incorporate a range of potential resource requirements—equipment, facilities, funding, materials, people, space, time and training—in your planning and reporting.

■ Constantly ask four questions to assess the plan’s viability: What could go wrong? What would indicate it is about to happen? What could prevent it from happening? What should be done if it does happen?

■ Identify where monitoring is needed, what specific monitoring measures will be put in place, what is happening compared with what should be happening (variation) and what corrective action (if any) is required.

Table 2.1 Separating operational reality and strategic initiatives

| Operational reality (business as usual) | Strategic initiative (change) |

|---|---|

| Seen as a routine request | Finite budget determined and monitored |

| Few known or crucial constraints | Allocated priority status |

| Limited risk involved | Specialised resources required and sourced |

| Functional and localised impact only | Sequenced tasks involving change |

| Managed with standard operating procedures | Requires proactive managing and reporting |

| Degree of flexibility in the output | Multiple stakeholders involved |

| Variable effort acceptable over time | Defined stages of both process and work |

| Component of your ongoing performance | Multi-functional (organisation-wide) impact |

| Likely to attract frequent interruptions | Sense of communicated urgency |

| Little sense of urgency evident | Benefits (outcomes) may be measured |

| Prone to inertia, delays and postponement | Change approvals required |

| May be poorly defined and/or explained | Agreed and monitored start and finish time |

| Potential for delegation is high | Documented and detailed scope |

Clearly, overlaps can and will occur between what strategy and operations involve. However, despite strategy being set by boards, executives and/or senior management, and operations set by middle- and lower-level managers, there should still be a clear line of distinction between what is strategic and what is an everyday operational focus. A useful dividing line between strategy and operations is the tried and tested effectiveness versus efficiency measure, where one looks at whether the organisation is doing the right things (effectiveness) or is in fact doing things right (efficiency). Table 2.2 (adapted from Stoner, Collins and Yetton, 1985) examines this explicit difference in more detail to again reinforce that, while both are required, each serves a different purpose.

Critical reflection 2.2

Routine work, operational priorities and strategic initiatives (projects) pretty much make up everything you come across on a daily basis at work.

■ Review Table 2.2 and see whether you can offer any more criteria to help separate operational and strategic ‘stuff’ in your workplace, as my list is not exhaustive.

■ Why is this differentiation important?

■ Do you think everyone in your organisation ‘gets’ this distinction when projects are created and handed out to already busy (and perhaps overloaded) employees? You might like to review and/or amend your critical reflection from Chapter 1 too.

To project managers, projects always come first. They must come with an executive mandate when they are first conceived, assessed and planned, right through to when they are executed, completed and handed over. This presents a number of potential issues, problems or straight-out conflicts between different managers, functional work areas, and policies and procedures, as different work areas struggle with increasing project workloads in workplaces that continue to downsize their personnel to the extent where many staff are required to do the equivalent workload of two or three people (who are no longer with the organisation). This is further compounded by the reality that culture ‘will eat strategy for breakfast every day’. Remember that culture is the invisible hand that silently and sometimes innocently shapes workplace behaviour through a set of established and adopted patterns, including beliefs, customs and practices.

Table 2.2 Separating strategy from operations

| Differentiating criteria | Strategy | Operations |

|---|---|---|

| Organisation focus | Long-term survival, development | Operational excellence, compliance, performance reporting |

| Over-arching objective | Growth, diversification, dominance, return on investment | Operational targets, performance against plan |

| Investment measurement | Revenue, margin and profit growth | Historical returns, present profits, controlled costs |

| Leadership profile | Visionary, inspirational, supportive | Conservative, directive, controlling |

| Organisational environment | Entrepreneurial, flexible | Bureaucratic, stable |

| Information requirements | Qualitative, conceptual detail | Quantitative, technical detail |

| Risk profile | Risk seeking | Risk averse |

| Management style | Encouraging and supporting innovation | Maintaining the status quo |

| Ongoing constraints | Changes in the internal or external environments | Operating procedures, policies, skills, legacy systems |

| Demonstrable rewards | Effectiveness, future potential | Efficiency, stability |

| Problem-solving | Proactive, learns and applies lessons | Reactive, reliance on past experience |

| Capability management | Succession planning, flexible workforce, partnering, performance management | Position descriptions, exception reporting, functional task priority |

| Learning approach | Proactive, targeted competencies, objective driven | Reactive, generic competencies, deficiency driven |

And it isn’t only culture that can spoil the party. Standard operating procedures (SOPs), the bane of work life for some, often set the protocols for operational planning, implementation, reporting and compliance regimes. While delivering benefits in the form of an established and agreed framework, equally these well-intended protocols can impinge on the sense of urgency that projects bring, their deadline-driven schedules, the required change process and approvals, and the focus on tracking, reporting and controlling technical, time and budget variations, as distinct from simply reporting variations.

Maintaining the credibility of change

Change, with its pervasive and complex nature, is ever present at both the strategic and operational levels in all organisations. In fact, you could call it the crucial conduit translating the strategic dialogue of the organisation into the operational reality.

With powerful macro-economic forces at work (new products, productivity gains, emerging technologies, growth, profitability, survival), change can be intrusive, disruptive and traumatic. Caught up in the press of everyday operations, invisible assumptions and unconscious behaviour (played out as organisational behaviour), change requires both courage and hard decisions. As it challenges the operational mandate to keep the current system operating (as opposed to creating an all-new system), balancing both continuity and the credibility of change demands responses outside of the defensive routines, traditional and formal boundaries, SOPs, redundant practices and expectations of the organisation (Kotter, 1998).

With an emphasis on stimulating mental work and not replicating physical work, you need the vision before the plans and programs. Without a sensible vision, any change initiative can easily dissolve into a list of confusing and incompatible projects, taking the organisation in the wrong direction—or, in fact, nowhere at all (Duck, 1998; Kotter, 1998).

Modelling the process of managing change

As organisations continue to move through what could be called ‘organisational transitions’ in moving from something old to something new (structural change, employee empowerment, downsizing, right sizing, reform or reengineering), the opportunity and/or challenge remains to provide navigation beacons along the way to lead and sustain the change. While there are numerous models of change management, two are examined in detail here. The eight-stage Kotter (1998) model is presented below, followed by the Kübler-Ross (1969) five-stage ‘grief cycle’ (remember that for many people, change is personal and fraught with loss and grief).

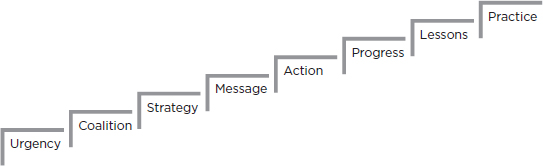

The eight-stage Kotter model can be summarised as:

1 establishing a sense of urgency:

■ taking on the challenge of fighting both complacency and lethargy

■ bombarding people with information about future opportunities and insisting that people talk to disgruntled clients and stakeholders

2 creating a guiding coalition:

■ directing change efforts through membership based on positional power, expertise, credibility and leadership (not cautious management)

■ recognising that change is fundamentally about feelings, trust and conviction (managing people is about managing feelings versus an intellectual commitment)

3 developing vision and strategy:

■ articulating vivid and coherent descriptions of audacious goals to combat complacent lethargy

■ thinking about what is strategically feasible and recognising patterns, and anticipating problems and opportunities before they occur

4 communicating the change vision:

■ without credible communication (words and deeds), and a lot of it, the hearts and minds of the employees are never captured (information vacuums will only create gossip)

■ creating metaphors, analogies and examples that enhance the two-way credibility of complicated messages quickly and effectively

5 empowering employees for broad-based action:

■ remembering that empowerment does not mean abandonment, and allowing employees to be creative and innovative by removing the operational obstacles

■ facilitating critical conversations discussing the undiscussable—what Duck (1998) refers to as ‘pity city’ (a bitch and brag session) or the popular Japanese practice of waigaya (Goss, Pascale and Athos, 1998)

6 generating short-term wins:

■ developing measures to plot progress towards victory and a new strategic language to describe it and build on what works, while discarding what doesn’t

■ directing effort towards results-driven improvement programs (a focus on achieving specific, measurable operational improvements) and not activity-driven improvement programs (feel good, adrenalin rush, delusional measurement)

7 consolidating gains:

■ project management and leadership from below in recognising enthusiasm, acceptance, commitment and celebration to keep the momentum going (and the ‘forces of tradition’ at bay)

■ allowing instructive lessons to be learned through exploring options, taking risks and making (critical) mistakes

8 anchoring new culture:

■ constantly watering the shallow roots (and the greenery) of change to ensure its ‘deep roots’ correspond to reality

■ resetting the new practices with new norms of behaviour and shared values, and working from the individual to the organisation.

Figure 2.3 reflects the progressive evolution of effective change management.

So the challenge remains in creating a compelling context for change while equally remembering that, in any attempt at change, the organisations can never legislate its employees’ feelings, even if it does rent their behaviour (Duck 1998). This concept is crucial in the next model. Based on the research of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (1969), first published in On Death and Dying, the five-stage ‘grief cycle’ model (based on terminal illness) adds another dimension to and level of understanding of the ‘staged’ journey, and of people’s emotional reactions, in response to change:

Figure 2.3 Change management process

1 denial—trying to avoid the inevitable: demonstrated by a conscious or unconscious (and natural) refusal to accept the facts, information and reality of the change context or situation

2 anger—frustrated outpouring of bottled up emotion: demonstrated by anger, rage, aggression or envy directed at themselves and/or others, especially those close to them

3 bargaining—seeking in vain to find a way out: demonstrated by attempting to bargain or seeking to negotiate a compromise in the guise of a short-term, unsustainable solution

4 depression—final realisation of the inevitable: demonstrated by acceptance of the certainty of change along with emotional detachment, sadness and fear in beginning to accept the reality

5 acceptance—finding the way forward: demonstrated by a deeply personal, singular and final belief in having to get on with the change.

Implications for the project organisation

Change, the by-product of strategic direction and the forebear of operational reality, continues to drive the project management landscape in many organisations. Regardless of the rationale, logic, business case or other applicable justification, change will continue to pressure organisations in the future as managers attempt to transform their organisations into competitive, flexible and sustainable organisations. Remember, by definition projects produce lasting change, which might not be welcomed by all. So while the project organisation, stakeholders and project manager may all believe that everyone is on board through their (explicit or implied) actions, such a blind belief could be premature. People’s response to change is not universal; it is purely and selfishly personal—and has to be encouraged and supported on a one-to-one basis. Nor will people’s response to change be intellectually driven, linear (in line with the models above), convenient or expeditious from the perspective of the project’s objectives.

Project (change) management should be about engaging both the heart and the mind, and not just about the great job it does in engaging the mind in concepts, schedules, reports and deliverables. Often it only links objectives and results in the scoping/proposal stage in assessing ‘what will benefit the company’, as opposed to trying to establish a sense of personal purpose that engages and transitions stakeholders (Lang-Cork: adapted from online resources).

Justifying the strategic decision

We know that strategy is geared around change and that projects are often the appropriate vehicles for delivering significant change. So let’s now align these two by getting the project into the right gear. Because strategy represents a future mindset, any resulting attempts to justify the project investment decision strategically must be equally forward looking.

Consider the following triggers as possible strategic justification criteria for any number of projects:

■ competitive activity

■ customer advantage

■ regulated compliance

■ operating necessity

■ enhanced capacity

■ product mix diversity

■ cost efficiencies

■ capital management

■ investment return

■ comparative benefit

■ political importance

■ organisational impact

■ interrelated projects

■ profitability growth.

Each of the above offers a genuine opportunity to drive the true strategic needs of the organisation, its environments and the intended result of the project. Regardless of whether the competitive activity example is in response to a competitor initiative, represents an aggressive, proactive move to increase market share or is an example of gaining increased efficiency, the project that delivers these results can always be fully justified, funded, prioritised, resourced and managed. This is achieved through the ownership, direction and support of the corporate strategic management team—many of whom often end up being project sponsors themselves.

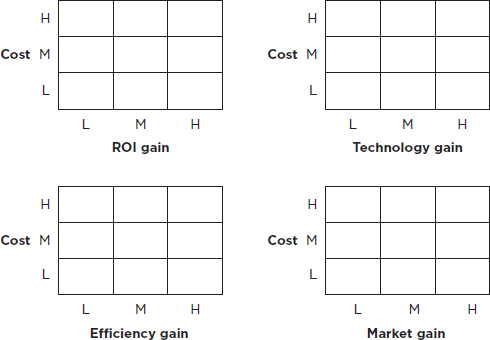

Figure 2.4 shows how easily different assessments can be made against the objective criteria of return on investment (ROI), technology, efficiency and/or market factors.

Clearly, these drivers and subsequent decisions will look potentially different for the private, public and not-for-profit sectors, as each responds both strategically and operationally to the environment in which it competes. This difference could be reflected in the communicated priority levels for their projects. Remember, not everything we do is critical or urgent, and it doesn’t need to be done immediately. Think about the routine administrative or discretionary tasks we have each day—timesheets, emails, updates, meetings, personal calls, surfing the web—and it is easy to see that few, if any, of these carry any high level priority. Perhaps some are important, although many could be done at any time under a low level priority setting.

Figure 2.4 Analysing project selection

So what is an appropriate priority scale to use for our projects? Is it:

■ a Likert scale with numbers from one to five

■ a descriptive scale of critical, important or routine

■ a list a pre-coded alphabet letters A, B, C?

If you have never considered establishing a priority scale for all those strategic initiatives and operational realities, you are confounding and compounding the chaos, reactive decision-making and management of these projects.

Meredith and Mantel (1995) identify six popular and simple non-numerical models that many project stakeholders still find appealing today, given the absence of mathematical modelling and analytics.

The sacred cow

As the name suggests, this selection tool enjoys the acknowledged ‘protection’ of a senior manager whose comments on and/or endorsements of an idea (perhaps a new product development project or a market penetration project) provide the necessary trigger to create the project. As Meredith and Mantel (1995) suggest, the project is sacred in the sense that it will be maintained until successfully concluded, or until the boss personally recognises the idea as a failure and terminates it. Clearly there is an element of self-interest, subjective decision-making and personal risk in this model; however, the obvious and public patronage of senior management should not be written off altogether.

The operating necessity

In a crisis, maintaining operational functionality becomes more important than the cost–benefit exercise. Redundant systems, a lack of support for technology and/or an impending natural disaster will all push a project to the top of the pile without too much formal evaluation. With such driving forces, there is room for distortion and rushed (and perhaps emotional) decision-making, with a lack of structured checks and balances.

The competitive necessity

Having gained market share, often at great cost and time spent, few organisations would be willing to sacrifice this in the light of a competitive threat. In these cases, a quick and decisive response is called for that again can bypass more independent evaluation processes. Furthermore, this response is entirely reactive, making it difficult for the project to be aligned with the strategic goals of the organisation. In effect, the project’s organisation may spend all its project investment on playing ‘competitive catch-up’.

Product line extension

In marketing terms, products and services progress along what is termed a ‘product life-cycle curve’ (an imaginary S-shaped curve portraying an idealised evolution of the product or service from market launch to market removal). As the products and services move along the curve, their appeal ultimately starts to diminish, giving marketing professionals the opportunity to try ‘product extensions’ or ‘product modifications’, which effectively reposition the product or service favourably with the consumer. In many cases, these decisions could be made intuitively without requiring too much analysis. Supermarket shelves, television and other media channels are full of product line extensions (sports, nutrition and health-related industries are perfect examples of this project-selection model).

Comparative benefit

One of the most appealing non-numeric models is the comparative benefit model. It is suited to those organisations tackling multiple projects, all of which offer differing degrees of benefits to the organisation. Selection is made by a team of managers who collectively decide to pursue those projects that offer the greatest value (even though this value cannot be defined accurately). Some weighing of the pros and cons of each project is mandated; however, the final choice can still be highly subjective.

Qualitative checklist

Despite some genuine criticism of this technique (limited ranking, comparison, prioritisation and non-financial criteria), checklists still offer an opportunity to scrutinise potential projects in assessing their viability (Wysocki, 2014). The checklist is easily created, as it is nothing more than a series of standalone questions posed against a number of criteria and asked for every project. The quality of the answer depends on the criteria, and common criteria include strategic alignment, benefits, risk, objectives, resources, timeline and funding.

Critical reflection 2.3

Any number of non-numeric selection models are available for use when assessing whether the proposed project will be accepted or rejected, with the weaknesses of the checklist approach already covered.

■ Review the other non-numeric models (and perhaps others you research) and note their weakness.

■ Which of the models does your organisation use and how does it justify this?

■ Can you suggest other models against which your projects could be assessed (and why)?

■ Construct your own checklist model, complete with suitable criteria and questions. Trial it with your next proposed project and evaluate its suitability.

A number of popular numeric selection models are also used, all of which reflect the profit capability of the project under evaluation. The four we will look at here are the payback period, the return on investment, the net present value and the project weighted evaluation matrix.

Payback period

One of the simpler models is the payback period. Under this model, the time taken to repay the original investment is the all-important criteria to consider. For instance, a potential investment in new plant will cost $100,000. Assuming that the annual cash flows from the project have been determined at $25,000 per year, it can be ‘calculated’ that it will take four years for the original investment to be returned. Clearly, this model requires information on anticipated cash flows that will last long enough to repay the investment. Any additional cash flows after this payback period are of no further use under this model.

Return on investment (ROI)

This is one of the most popular models. It evaluates the project’s profitability by first calculating the average annual profit of the project, then dividing that by the number of years for which the project investment is required. Expressed as a percentage, the return on investment model takes into account the entire cash-flow period of the project. For instance, consider the earlier example where the project investment was $100,000 repaid over four years. Assume now that the project returns cash flows for another two years at $20,000 per year. The average annual profit would be the total gain or profit of $140,000 less the original investment of $100,000, or $40,000. To calculate the return on investment, simply divide the $40,000 by the original investment to determine the 40 per cent return (rather healthy in this example).

Net present value (NPV)

This model is one of two discounted cash flow (DCF) models commonly used to evaluate projects (the other one being the internal rate of return). The NPV takes into account the future value of investment money from the second year onwards by discounting the project cash flows by the required rate of return (sometimes known as the ‘hurdle’ rate). Any positive NPV values would signal that the project is acceptable. The formula used to calculate the NPV is:

NPV = Discount factor × Cash flow

The discount factor is calculated from 1/(1 + i)n where i is the forecast interest rate and n the number of years from the project start date. A complete list of all discount factors can be obtained from an annuity table found in most statistical, finance and/or management texts.

Project weighted evaluation matrix

Representing a combination of qualitative and quantitative criteria, this model suggested by Wysocki (2014) uses weighted criteria, assigned scores and multiplied totals to effectively rank multiple projects for consideration. Projects returning the higher rated scores represent better options than the lesser scoring projects, and are more likely to be prioritised as likely project contenders.

Much like an evaluation matrix used by recruitment organisations and tender evaluations, the weighted matrix is easy to construct and does provide a reasonable level of objective comparison (all things being equal).

Burke (1999) proposes five criteria to be used when evaluating the project-selection models, be they numeric or non-numeric:

1 a degree of realism reflecting the manager’s current situation with regard to facilities, resources, risk and other relevant decision-making criteria of the organisation

2 the capability to deal with multiple time periods while simulating a number of variable internal and external situations facing the project

3 whether it can quickly and easily be put into place

4 an element of flexibility that allows for modification as the project organisation’s environment changes

5 ideally, a low-cost regime relative to the cost of the project and well within the potential benefits of the project.

These, and some additional suggestions, are summarised in Tables 2.3 and 2.4.

Projects come in all shapes and sizes—as they should. No two projects are alike in any dimension, be that time, cost, risk or quality. This obviously has direct implications, as the project will need to be scaled appropriately against some independent, objective and robust criteria.

With classification comes the ability to scale the methodology itself, as not every project requires the ‘full-blown’ set of project processes and templates. A relatively small project might only require some initial and brief documentation, followed by minutes of meetings and a final email confirming completion. Other large projects, however, might well need an initial brief followed by a thorough business case and requirements document before the project proposal gets signed off. The hard question, though, is: What should the classifications look like in terms of terminology and criteria?

Table 2.3 Advantages and disadvantages of non-numeric project-selection models

| Model | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Sacred cow |

■ Supported by senior management |

■ Probability of empire building ■ Project tied to a manager’s tenure ■ Lack of organisation-wide support |

| Operating necessity |

■ Driven by situational realities ■ Fast-tracked decision-making (can also be a disadvantage if rushed decision-making results in a poor outcome) |

■ Pressure to conform with operational pressures ■ Limited budget provision ■ Insufficient time to plan ■ Few alternative options canvassed ■ Limited functional impact |

| Competitive necessity |

■ Ability to match competitors |

■ The likelihood of playing catch-up ■ Little analysis of competitor actions |

| Product line extension |

■ Taking advantage of market conditions and opportunities ■ Gaining economies of scale from plant and personnel ■ Increased market penetration |

■ Often hard to defend rationally ■ No guarantees of market success ■ Possibility of eroding existing product market share and/or profit results |

| Comparative benefit |

■ Discussion and capture of all project benefits ■ Increased visibility for all projects under evaluation |

■ Lack of focus on projects warranting independent approval ■ Potential to overlook low-visibility projects |

| Qualitative checklist |

■ Opportunity to pose a number of relevant questions framed around key aspects of the project ■ Invites rich descriptive information |

■ Opinion-based only ■ Time consuming to verify and quantify responses |

Table 2.4 Advantages and disadvantages of numeric project-selection models

| Model | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Payback period |

■ Simple to use and understand ■ Highlights projects with the shortest payback period ■ Uses financial data already available ■ Does not require any sophisticated software ■ Reduces project risk by supporting projects with the fastest payback |

■ Assumes cash flow will last for the life of the project ■ Ignores the time value of money (future cash flows) ■ Focuses only on cash-flow projections ■ Fails to quantify risk exposure ■ Is not suited to long-term projects where changing inflation and interest rates could dramatically alter the results |

| Return on investment (ROI) |

■ Takes into account the total cash flow of the project ■ Easy to use ■ Acknowledges the project profit and the percentage return on investment ■ Aligns with existing investment management techniques |

■ The profit is averaged out over the project ■ The challenges of determining what percentage of return is acceptable by management |

| Net present value (NPV) |

■ Uses the time value of money with all future cash flows in today’s values ■ Can simulate different scenarios by changing the values used ■ Considers the whole project, year by year ■ Can be structured to allow for inflation |

■ Uses a fixed interest rate over the life of the project ■ Estimated future project cash flows may differ dramatically from actual results ■ Accuracy is driven by interest rate predications and forecast cash flows |

| Project weighted evaluation matrix |

■ Focuses on a finite number of key criteria ■ Agreed weighting scale ■ Answer scoring protocol |

■ May exclude other criteria equally, if not more important ■ Not everything can be summarised in a numeral ■ Weights and scores can be manipulated |

Table 2.5 provides some guidelines for and illustrative examples of how projects could be scaled and classified. There can be no right or wrong options, as each organisation and project will dictate different criteria and classification cutoffs. Nor are the criteria mutually exclusive of each other, which only serves to compound the classification guide all the more. Irrespective of these obstacles, a classification guide should be developed and communicated across the project organisation.

Table 2.5 Project classification guidelines

| Criteria | Classification | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1—Lean | 2—Lite | 3—Large | |

| Planning | No | Limited | Extensive |

| Scheduled time | No | > Month | > Month |

| Budget forecast | No | < $50,000 | > $50,000 |

| Risk exposure | Low | Moderate | High |

| Stakeholders involved | Few | Many | Multiple |

| Organisation impact | Slight | Low | High |

| Benefits measurement | No | Monitored | Evaluated |

| Formal evaluation | No | Yes | Yes |

| Contractual obligations | Rarely | Occasionally | Often |

| Quality standards | Few | Required | Required |

| Scope revisions | Minor | Moderate | Extensive |

| Project manager | Functional manager | Part/Full time | Full time |

| Methodology | Abridged | Complete | Complete |

| Communications strategy | No | Basic | Organisation-wide |

| Change controls | No | Explanation | Justification |

Critical reflection 2.4

Project classification remains a bit of a mystery to many, with any number of criteria available to assess the scale or magnitude of the project. After all, no two projects are the same and projects will need to be structured differently depending on how they are classified.

■ Review the classification guidelines in Table 2.5 and add additional criteria that you think are important for your projects.

■ Consider different classification headings too, as ‘lean’, ‘lite’ and ‘large’ might not quite work for your organisation; however, the examples I cite do provide an insight (on some level) into the scale or enormity of the project.

Based on what you have read, you might now have a project being initiated. What was once a thought bubble, a sacred cow or, worse still, a crazy idea devoid of any reality check that then became a strategic objective has (ideally) survived an extended process of rigorous assessment involving justification selection, classification and/or prioritisation stages. And while this assortment of information could be captured in any number of documents, the business case is where most organisations elect to populate this data.

The business case documents whether or not the ‘idea’ is viable in terms of the required investment (which doesn’t just have to be financial). The business case will define the business need, problem or opportunity in detail, analyse the different options, identify the costs, benefits and risks, and put forward a recommendation to proceed with or postpone the project. A number of potential options are evaluated against a set of criteria to help determine the viability of a particular option proceeding. And in the case of multiple project initiatives, the business case can be used to prioritise each one. Once approved, the business case will trigger the project proposal or charter.

In framing the business case process, perhaps a number of rather relevant questions need to be asked of the organisation first. The PRINCE2 methodology is particularly focused on the business case and I have included some of its preferences (and my own):

■ Has the business need been stated clearly?

■ Have the benefits been clearly identified? How will they be measured, and when?

■ Does the project align with the organisation’s strategy?

■ Is it clear what will define a successful outcome?

■ Have a number of options or alternative being assessed, and the preferred option identified?

■ What level of organisational impact will there be?

■ Can the project be funded adequately?

■ Are the risks faced by the project explicitly stated? What plans are in place to mitigate those risks?

So it would seem you have some degree of discretion as to what the business case reflects. Let’s try to narrow down the choices to reflect the following considerations, including:

■ executive summary

■ organisational background

■ vision, values and mission

■ business need (or opportunity)

■ strategic objectives

■ options appraisal

■ market conditions

■ performance capability

■ organisational impact

■ the risks involved

■ indicative timeline

■ financial investment

■ life-cycle costs

■ expected benefits

■ the level of project maturity

■ stakeholders involved and committed to the project (internal and external)

■ current operational and/or project commitments

■ interdependencies with current projects, programs and/or portfolios

■ the project management approach

■ the cost of doing nothing

■ recommendations

■ approval (signature block)

■ the next step.

Collectively, these (and other) headings will not only justify and initiate the project; they will provide a subsequent framework for the planning and management of the project once it starts. In other words, the business case will remain the static reference against which the project’s performance and benefits can be monitored and assessed. However, remember that you will need to adapt your business case to your organisation in getting the right fit and feel.

Critical reflection 2.5

The point has been made that not all project justifications have to be based on sound financial returns on investment.

■ What other (non-financial) information from an organisational perspective would warrant a project being worthy of initiation?

■ How would the subsequent benefits from such a project be measured clearly and accurately?

■ Should projects always include both numeric and non-numeric selection and/or justification criteria? Justify your answer.

As flagged above, the project endorsed by the business case may also impact one or more other projects, which are being planned, performed or finalised by the organisation.

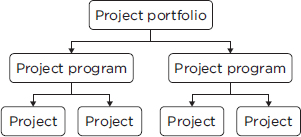

It may be that the project forms part of a program that simply means it is one of a few other projects that are managed separately but share a common goal. Road construction is a great example where a number of projects are being completed, with each project (with separate objectives, contracts, contractors and deliverables) comprising a different part of the overall construction program. In some cases, large projects could be broken up into more discrete and smaller sub-projects, creating a project program with multiple project resources required. They could be planned and managed separately while still delivering on the overall program objectives. A program manager (or some other non-project functional role) will be appointed to manage the whole program.

A project portfolio takes the concept to another level, where all the projects the organisation has on at any one time could be termed a portfolio, in which all are linked to the strategic plan or some other strategy. They may sit within a particular business unit and have a common objective, or be scattered across the entire organisation with different objectives. Given the potential scale of projects, a portfolio manager (or similar) will be appointed to manage the portfolio (Figure 2.5).

Kerzner (2001) suggests that another link also exists between the notions of strategy and projects, believing that the project management maturity model (PMMM) provides general guidance on how to perform strategic planning for project management. The model, built on five stages of escalating organisational-wide project management development, serves as the ‘foundation of excellence’ in baselining, nurturing and evaluating project maturity over time.

Project maturity is (and will always be) an evolving concept, and in principle it is a lot like any linear life-cycle approach, with one level of maturity triggering the next level. However, the maturity models differ in one key area: maturity levels can, and often do, overlap. This is certainly true in many siloed project organisations, where each department or section operates largely independently of the others, with different approaches and templates for managing their projects. And the degree of overlap will be a function of the alignment of projects, ownership issues, scaled methodologies, governance and myriad other variables—mostly invisible and uncoordinated in any systemised way. Let’s now explore exactly what project maturity actually means, and the different target levels and evidence pool that would demonstrate and validate project maturity.

Figure 2.5 Projects, programs and portfolios

The word ‘maturity’ may well mean different things to different people (as one would expect). Defined generically, perhaps it means wisdom, adulthood, experience, reliability or even development. If someone has ‘maturity’, perhaps they are in the prime of their life, ready to take on whatever life throws their way. Swinging the definition back to project management, the term ‘maturity’ is, more often than not, broadly defined as excellence (or degrees of excellence). And as you would appreciate, excellence, more often than not, develops at different times and to different degrees over time. The popular terminology for tracking these ‘degrees’ of excellence are: immaturity, maturity and excellence.

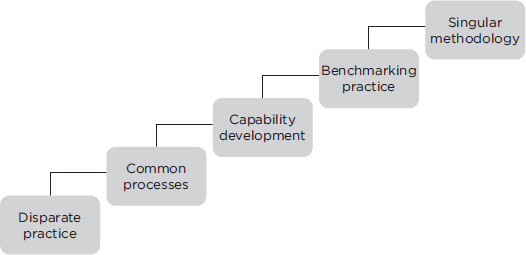

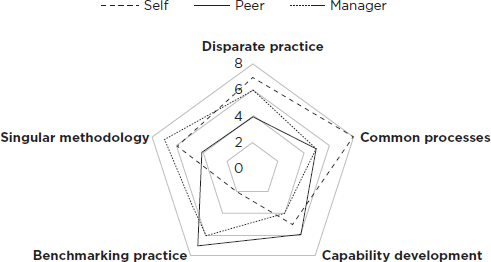

As reflected in Figure 2.6, each of the five maturity levels enable the project organisation to assess their project performance and level of maturity against a number of generally accepted criteria.

Each of these levels is examined in Table 2.6. It includes some of the terminology and signposts from Kerzner (2001), along with some additional examples to help you identify your current level of maturity.

Figure 2.6 The pathway to project management maturity

Table 2.6 Project management maturity levels

| Maturity | Alternative naming options | Common signposts (behaviour and practices) |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1 |

Siloed language Initial process Basic understanding Immaturity |

■ No established (or endorsed) standards ■ Work is performed in an ad hoc fashion ■ No agreed, repeatable process in place ■ Minimal documentation ■ Individual and informal practices ■ Performance is reactive ■ Siloed self-interest ■ Little training or education ■ Lack of executive support ■ Sporadic use of project management techniques ■ Recognition of the need for, and importance of, project management ■ A basic understanding of project management principles ■ Attempts to develop a common project management language |

| Level 2 |

Common processes Structured process Agreed standards Coordinated effort |

■ Basic documented process ■ Focus on large or highly visible projects ■ Standard scheduling developed ■ Senior management visibility increases ■ Organisational commitment grows ■ Training focus shifts to competency and capability development ■ Focus on managing time, cost, specification and resource constraints ■ Recognition of the application of project management principles ■ Definition of common project management processes ■ Expectation of repeatable project success ■ Identification of tangible benefits from project management principles and a unified approach |

| Level 3 |

Singular methodology Institutionalised process Organisational standards Managed methodology |

■ Fully documented processes ■ Adoption from most projects ■ Compliance monitored and reported ■ Organisational standards followed ■ Integration of all corporate methodologies into a single (project management) methodology ■ Organisation is totally committed to project managing its projects ■ An adaptive and cooperative culture ■ All layers of management visible ■ Capability development aligned with maturity |

| Level 4 |

Benchmarking standards Integrated processes Best practice Maturing expertise |

■ Recognition that process improvement is a competitive advantage ■ Adoption of continuous analysis and evaluation ■ Establishment of a project office (PO), project management office (PMO) or strategic management project office (SPMO) ■ Quantitative and qualitative benchmarking ■ Integrated and accountable decision-making ■ Organisational-wide impacts integrated into projects ■ Strategic planning is the focal point of project management |

| Level 5 |

Continuous improvement Optimised process Process improvement Ongoing excellence |

■ Evaluation of benchmarking activities ■ Ongoing refinement of singular project methodology ■ Critical assessment and dissemination of lessons learned ■ Knowledge-transfer and mentoring initiatives ■ Guidelines developed to feed improvements back into the process ■ Value-based performance metrics measured and managed |

Figure 2.7 Organisational project management maturity

Once you are comfortable with this notion of project management maturity, you might like organisational assessment of your level of maturity. Figure 2.7 illustrates how your results can be displayed using a 360-degree self-report assessment.

Critical reflection 2.6

Project management maturity doesn’t happen overnight, with many organisations failing to rise above the first few levels. And while there is no ‘rule’ that states you must reach Level 5, developing progressive project maturity will deliver tangible benefits to how you plan and manage your projects.

■ What level of project management maturity does your organisation have?

■ What impact (if any) does this have on your projects?

■ What steps are required to consolidate your current level of maturity?

■ What steps are required to improve your maturity to the next level?

Sitting within the boundaries of the project organisation’s maturity level is the personal level of competence held by its employees.

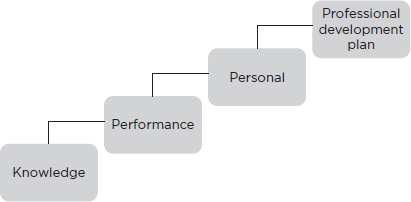

The project management competency development (PMCD) framework is endorsed by the Project Management Institute. By linking PMBOK knowledge areas with individual competence, the PMCD has rightly focused on the importance of developing and demonstrating competence across three interdependent areas:

1 knowledge: what is known about project management theory, practice, processes, tools and techniques for all project activities

2 performance: how this knowledge is applied throughout the project

3 personal: what behaviours, attitudes and personality characteristics are on display when these activities are performed.

While acknowledging that these generic competencies are most likely universal in most, if not all, projects, this framework does not reference particular technical, environmental, political, social, information technology competencies that might be required in some projects, as these forms of specific competencies depend on the industry and/or organisational context. Figure 2.8 depicts the relationship between the three competencies and their progressive relevance to developing a professional development plan.

Figure 2.8 Project management generic competencies

Within PMBOK (as with other methodologies), a finite number of knowledge areas or domains must be known in order to demonstrate competency. Under the PMBOK mantle, some of these knowledge areas could include:

■ project management body of knowledge

■ project life-cycle management

■ project management process groups

■ projects, programs and portfolios

■ project management office (PMO)

■ project management knowledge areas:

□ scope management

□ time management

□ cost management

□ quality management

□ risk management

□ communications management

□ human resource management (HRM)

□ stakeholder management

□ procurement management

□ integration management.

Critical reflection 2.7

Each project management methodology promotes its own ‘unique’ knowledge area. Choose from PRINCE2, Agile or Lean and record what knowledge areas a competent project manager (or some other project role) would ideally need to know about.

These competencies relate to how that knowledge is actually being applied throughout the project, as knowing the theory and doing the theory can be worlds apart.

Again referencing PMBOK, the five units of performance competence relate to their five process groups:

1 initiating a project

2 planning a project

3 executing a project

4 monitoring and controlling a project

5 closing a project.

Think about what performance is required for initiating a project and for facilitating the development of the business case. In the planning processes, what are you doing to confirm the project’s scope, budget, timeframe and resourcing decisions? How are you mitigating potential risk, designing quality in from the start, establishing the communications protocol and working through team roles and responsibilities (just for starters)? Moving to the execution process, what are you doing to ensure that the agreed scope is achieved, that the team is performing as it must and that the plan is being managed effectively?

Critical reflection 2.8

The examples above cover some of the performance competencies needed in the first three process groups under PMBOK.

■ What performance competencies would be displayed during the monitoring and controlling of a project, and in closing a project?

■ Revisit the initiating, planning and executing process groups above and see whether you can identify further examples.

Now let’s get up close and personal. You know and understand the knowledge, and you can apply it with varying degrees of success as you work on developing your individual capability over time and through each evolving project success or failure.

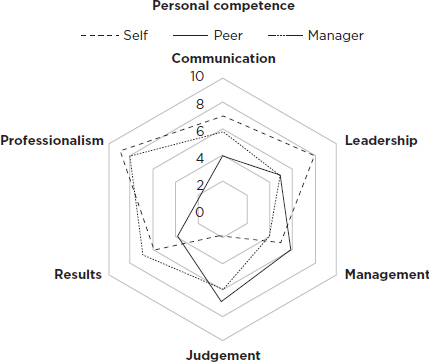

While realistically there are any number of personal competencies to draw from, PMBOK flags the following six:

1 communicating: matching intent with outcome with all stakeholders

2 leading: balancing direction and support

3 managing: administering compliance

4 judgement: using perception, discernment and cognition

5 results: being effective in realising activities and objectives

6 professionalism: demonstrating ethics, respect and honesty.

Table 2.7 provides examples of where your focus could lie in developing each of these areas. While the suggestions are generic examples only, read through them carefully but try to identify many more from a personal perspective as only you know where you need to improve.

Table 2.7 Project management personal competencies

| Communicating |

■ Actively listening ■ Being honest ■ Adjusting for your audience ■ Encouraging contributions ■ Providing appropriate feedback ■ Avoiding premature evaluations ■ Aiming for consensus ■ Keeping accurate records |

| Leading |

■ Developing a team identity and spirit ■ Maintaining appropriate relationships ■ Delegating responsibility while retaining accountability ■ Being prepared to lead and follow ■ Encouraging ideas ■ Rewarding innovation |

| Managing |

■ Documenting the project ■ Assigning project work ■ Working the plan ■ Managing performance ■ Resolving conflicts |

| Judgement |

■ Taking the big-picture view ■ Staying close to the project ■ Considering opinions, beliefs and values ■ Being sensitive to others ■ Valuing experience ■ Respecting insight |

| Results |

■ Maintaining momentum ■ Resolving problems ■ Monitoring performance ■ Motivating and rewarding ■ Being assertive |

| Professionalism |

■ Having a visible commitment ■ Operating with integrity ■ Supporting diversity ■ Acting ethically ■ Being transparent ■ Undertaking full disclosure |

In the resource supplement for this book, you will find a self-report template for a 360-degree assessment of your project management competencies. Figure 2.9 captures how your competency scale can be displayed.

Figure 2.9 A 360-degree competency assessment

Project organisational structures

A key ingredient (or necessary infrastructure) supporting the project’s success is the organisational structure housing the project, which formally identifies, communicates and manages all the relationships between all the stakeholders and the work they perform. Common sense would dictate that, if the structure is sufficient for the project and/or tasks imposed upon it, it will endure and ‘guide’ the project. However, should the organisational structure inhibit performance, pressure will build until the project outcome finally becomes compromised.

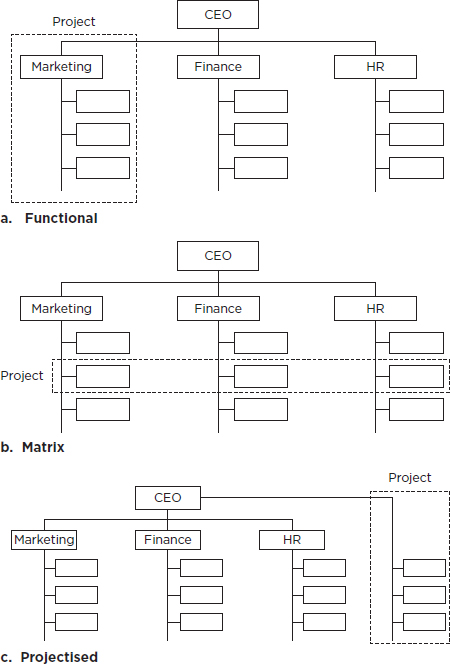

While there are a number of hybrid organisational structures from which to select, let’s focus on the three most popular structures adopted by the project fraternity.

1 Functional: A traditional structure aligned with the existing organisational department or functions (in effect, an overlay of the existing organisational chart). Under this structure, the project is subsumed within an existing and relevant department or function most aligned with and capable of directing and supporting the project. Few, if any, changes are required to fit the project into how the department does things. (Can you see the potential benefits and dangers of this structure?)

2 Matrix: A blended structure supporting both the existing functional authority, priorities, performance and accountabilities with the (at times) competing and conflicting authority, priorities, performance and accountabilities from the project. In other words, the project resources which are assigned and managed under this structure will often end up taking direction from two or more superiors—their functional manager and the project manager. (This contravenes a major tenet of good management—a subordinate should only ever report to one manager.)

3 Projectised: A separate and discrete structure that technically sits outside the existing organisational structure with dedicated full-time resources assigned to the project. Answering directly to senior management, this type of structure removes the need to compete with other departments for limited resources (people and/or equipment), or to get caught up in the day-to-day operational minutiae.

Figure 2.10 depicts three project organisational structures, while Table 2.8 summarises the major advantages and disadvantages of each structure. Feel free to add your own ideas to the list.

Choosing the right project organisational structure

Each one of these structures is an ideal structure, one that will work and can support and guide the project’s success. People run into trouble with these when they align the wrong structure with the wrong project (and it doesn’t work) and/or they simply do not understand the rationale behind each structure and the potential benefits or dangers lurking there. The structure must match the project.

The selection of an appropriate organisational structure to maintain the project should be determined by situational factors—that is, the variables underpinning the project. Generally, there are no step-by-step procedures, rule books or generic guidelines (other than intuition and history) to guide and influence the selections. Some clues could be located in the organisation’s culture and the variables for each project, with the aim of a ‘best fit’ structure given the current circumstances.

Figure 2.10 Three project organisational structures

The reality will often be that project sponsors, project steering groups, executive management and/or other project stakeholders will already have determined and prescribed many of the project constraints (time, budget, resources, specification), which in many cases negates any opportunity for the project manager and/or the project team to align with (or create) the optimal project organisational structure for their project. Some contributing factors might be:

Table 2.8 A comparison of project organisational structures

| Organisational structure | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Functional |

■ Already in place ■ Resident technical expertise ■ Normal career path ■ Defined responsibility and authority ■ Known reporting lines ■ Fast response times ■ Staff flexibility ■ Access to backup resources ■ Ease of reassignment |

■ Lack of coordinated effort ■ Client is not the focus of activity ■ Compartmentalises the project ■ Confused priorities ■ No clear project manager ■ Failure to pinpoint responsibility ■ Existing protocols drive the project |

| Matrix |

■ An appointed project manager ■ Tailored to the project’s needs ■ Shared personnel, facilities and equipment ■ Clear return path to reassign resources ■ Access to organisational-wide expertise ■ The project is the point of emphasis ■ Opportunities for training and development ■ Multi-skilling across functional environments |

■ Greater complexity to work within and to manage diverse input ■ Results in confusion, divided loyalties and unclear responsibilities ■ Staff commitment can be variable ■ Multi-layers of decision-making ■ Staff reporting to multiple managers ■ Cross-functional conflict ■ Missed promotional opportunities within normal function |

| Projectised |

■ Project manager has absolute authority ■ Clear chain of reporting ■ Resources dedicated full-time ■ Resident experts ■ Timely decisions ■ Holistic approach taken ■ Project team has separate identity ■ Strong motivation and commitment |

■ Duplication of facilities, equipment and effort ■ Costs in setting up ■ Replacement costs in taking staff ‘offline’ ■ Sheltered environment could cut corners ■ Uncertainty post-project ■ No opportunity for cross-fertilisation of ideas with other functions ■ Development of ‘us and them’ mentality |

■ blind adherence to traditional project management principles, processes and practices

■ a lack of clarity regarding how the project aligns across the existing business

■ working within known organisational reporting constraints

■ the degree of secrecy limiting the project’s whole-of-business exposure

■ limited inexperience and/or exposure to the known and hybrid project organisational structures

■ an over-reliance on known, proven and limited resources

■ projects that are not properly conceived, planned, executed and finalised.

All the organisational structures presented offer the project and the project parent organisation some value and the key to success. The obstacle is not aligning the right project with the right structure. However, blaming executive dictates, bureaucracy, paradigms or inexperience is not the answer. What is needed is open and frank communication, assertive project personnel and teams that fully appreciate, accept and demonstrate their full responsibilities imposed by the project scope in conjunction with their existing operational commitments.

Remember that project management is all about creating order out of chaos through change. It is about scheduling solutions for success, and it is about managing change. To achieve any of these, the organisational structure must be right. Projects are about bringing resources together to realise a shared outcome. They are about:

■ vision: where are we going?

■ team ownership: buy-in, what’s in it for me?

■ balanced skill sets: people ready to replace each other

■ appropriate team roles: the right person doing the right job

■ accepted and delegated responsibility and accountability.

Critical reflection 2.9

Given the different options you have in working under a particular project organisational structure, little thought is sometimes given to what the appropriate structure might actually be.

■ Should the organisational structure fit the project or the project organisation?

■ Is your current project being established under the appropriate organisational structure?

■ What are the obvious benefits of choosing the right structure and the equally obvious disadvantages of getting the structure wrong?

■ With the advent of virtual teams and new technology platforms, are there any other types of organisational structures that are appropriate to planning and managing projects?

While successful projects need thorough planning as one of their essential prerequisites, Gardiner (2005) recounts four fundamental pillars of governance that collectively work towards addressing direction and control in projects:

1 accountability: the capacity to call people to account for their actions

2 transparency: visible and open processes

3 predictability: uniform compliance and enforcement within laws and regulations

4 participation: stakeholder input and reality checking.

Cole (2010), in referring to the ways in which organisations are managed and controlled, argues that the focus of good governance is that boards and executives use due care and diligence by:

■ acting independently

■ appointing auditors

■ evaluating senior management

■ approving, scrutinising and monitoring strategies, performance and key decisions