PILLS, POTIONS AND THERAPIES

By this point in the book, you know quite a lot about how sleep works, and how to improve your sleep hygiene to give you the best possible chance of having a good night’s sleep. You also know about a lot of sleep disorders. The final step is to bring together some of the therapies and medications available to you to support your efforts to take control of your sleep.

In this chapter I begin with some information about conventional medicines, including a table to introduce you to medications that you can buy over the counter and those your doctor may prescribe. Then you’ll find advice on alternative therapies and natural medicines that have been shown to be beneficial to sleep. I’ll explain what a sleep centre is and what happens if you visit one, and conclude with a whistlestop tour of some of the gadgets and gizmos that you can use at home to find out more about your sleep and how to improve it.

Conventional medicines are pharmaceutical drugs both prescribed by a medical doctor, appropriately qualified nurse or (in some countries) a pharmacist and “over-the-counter” (OTC) drugs. The latter are usually sold following a consultation with a pharmacist and bought directly off the shelf in a store. The laws covering the supply of medicines vary from country to country. Some of these differences may arise from cultural attitudes to taking medications to aid sleep.

A short history of sleeping pills

The proper term for sleeping pills is “hypnotics”, derived from Hypnos, the Greek god of sleep, who is often depicted holding a poppy (the seeds of which give us opium, which in turn gives us morphine, a sedative). Since ancient times the search for natural or chemical sleep aids has, as you would expect, come a long way. In 1832, the German chemist Justus von Liebig synthesized the sedative chloral hydrate. Still in use today, chloral hyrdrate gained notoriety as a component of “Mickey Finn” – a dangerous combination of this sedative and alcohol.

In the mid-1800s the Prussian chemist Adolf von Baeyer synthesized compounds called barbiturates. These weren’t used as hypnotics until the early 1900s, but then became the most common sleep aids right up until the 1970s. Barbiturates work, but they’re extremely dangerous – overdoses can be (and have frequently been) fatal.

With this danger in mind, in the 1970s attention instead turned to benzodiazepines. Initially discovered in the 1950s, benzodiazepines came to the fore when it became clear that it was almost impossible to take a fatal overdose of them. However, the human body can develop a tolerance to these medications, meaning that their efficacy reduces the longer we take them. As we then need to take a higher dosage to achieve the same effects, addiction becomes a very real danger, followed by withdrawal symptoms when the hypnotics are stopped. In the 1990s, chemists synthesized the non-benzodiazepine “Z” drugs: zolpidem, zopiclone and zaleplon. Although these do have some risk of dependency, it is much lower than it is with benzodiazepines. Today, benzodiazepines and Z drugs remain the most widely prescribed drugs for insomnia.

Importantly, though, any drug taken to tackle a sleep disorder relieves the symptoms, but not the cause. While you may not know why you’re suffering from insomnia, in order to find a long-term solution it’s essential to live a lifestyle conducive to good sleep. Conventional medicine may help in the short term, as a coping strategy that enables you to put other things right, but it doesn’t provide a safe, long-term solution. And, there’s no “one size fits all” option – understanding the nature of your insomnia is important for getting your medication right, as well as for resolving your sleep problems altogether.

How do these drugs work?

In the body, GABA, a major neurochemical, attaches itself to certain nerve-cell receptors and affects how messages flow within those cells, inhibiting cell activity. Benzodiazepines and Z drugs – as well as barbiturates, chloral hydrate and perhaps certain herbs – mimic GABA to have relaxing, anti-anxiety, anti-convulsive and amnesic effects. They also promote sleep. Older benzodiazepines that attach to the GABA receptors are described as “non-specific”: they not only induce sleep, but also have, to some extent, all those other properties. Compounds that promote only sleep are “specific”. Z drugs have similar effects to specific benzodiazepines, but are a separate class of drug.

What are the effects, side-effects and dangers?

All benzodiazepines and Z drugs can promote sleep. Some Z drugs increase deep sleep (see p.215) and like the benzodiazepines improve the time it takes to fall asleep and the ability to fall back to sleep quickly if you wake in the night. Recent trials in the USA show that zolpidem, zaleplon and eszopi-clone maintain their efficacy in the long term, making them less addictive.

When you stop taking any hypnotic, even after only a short time, you’ll suffer a return to wakefulness, known as “rebound wakefulness” – your insomnia may appear worse, albeit only temporarily. Things are worse for long-term (chronic) users. Between 10 and 30 per cent of long-term benzodiazepine users are physically dependent on the drug, and at least 50 per cent will suffer from withdrawal syndrome when they cease medicating. The syndrome consists of anxiety, depression, nausea and perceptual changes, as well as rebound wakefulness. As a result, clinicians can prescribe these drugs only for severe insomnia and at the lowest dose possible for not more than four weeks.

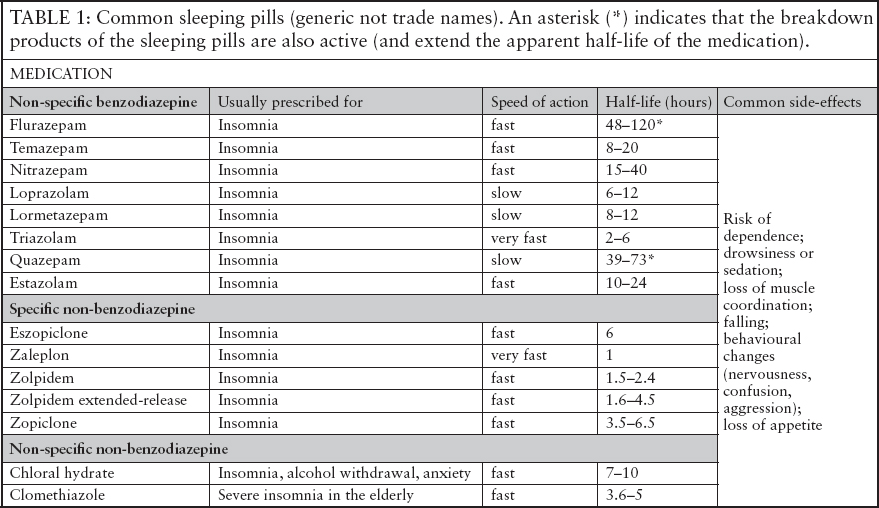

Table 1 on the previous page lists the most commonly prescribed hypnotics available in the UK or USA (some are available in only one country). Generally, sleeping pills are distinguished mainly by how quickly they can act and how long they stay in the brain and body. The time to reach maximum concentration in the blood is a good guide as to how quickly they act. The “half-life” is a measure of how long it takes the body to break down the drug – the shorter the time, the faster it’s removed; the longer the half-life, the longer-lasting the effects.

If you have problems falling asleep, your doctor is likely to prescribe you a drug with a shorter half-life. If your issue is waking up in the night, your doctor may prescribe you a drug with a longer half-life. In the table “fast” means that the hypnotic is active within an hour.

Over-the-counter sleep medications and more

We think that up to 40 per cent of people with insomnia self-medicate with non-prescription hypnotics bought in pharmacies. Although many of these medications contain compounds known to improve sleep, the fact that they’re available without prescription tells you all you need to know about actually how effective they are for inducing sleep.

Clinical trials for them usually involve small numbers of participants, which means that results aren’t as robust as they could be.

Table 2 on pages 220–21 lists many of the over-the-counter medications that may aid sleep but that are not intended as hypnotics: most of them are to treat other medical disorders, but have soporific effects. Antihistamines, developed to treat allergies such as hay fever, have sedating effects that has added to their usage. Melatonin is a special case: I’ve given specific information about it on page 17. However, it’s included in the table as it’s now used in a formulation with the UK trademark “Circadin” for those over 55 and suffering from insomnia (seep.221).

Sleep centres are special clinics where experts can diagnose and treat sleep disorders. They are, in many countries, connected to hospital respiratory departments. This is because sleep apnoea (see pp.192–4) has such strong links with other medical conditions. These centres concentrate on measuring the airflow through your nose, breathing effort and blood-oxygen levels. However, throughout the world, there are also now clinics specifically intended for dealing with the full spectrum of sleep disorders. A sleep centre might be suitable for you if:

• You have a persistent and ongoing problem with your sleep (such as an inability to sleep, broken sleep, snoring or other breathing-related disorders, or excessive daytime sleepiness).

• You’ve followed my methods for optimizing your sleep hygiene and yet see little improvement in your sleep quality.

• You don’t want to begin relying on sleeping pills without first getting expert advice on the nature of your sleep problems.

What happens at a sleep centre?

A sleep centre will almost certainly send you a sleep diary (see pp.156–159) to fill in every night for (usually) two weeks before your appointment, as well as a questionnaire. What happens next depends on specialist analysis of your diary and your questionnaire answers.

• If your issues might be to do with your biological clock, you may be given an actigraph to wear. This monitors your levels of activity and rest over the course of 24 hours.

• If you have suspected sleep apnoea or other physiological causes for your sleep issues, you may be given an oximeter (a clip that attaches usually to your finger) to measure oxygen and haemoglobin levels in your blood, a nose clip to chart your air-flow and a chest band to assess your breathing.

• If your sleep disorder needs further investigation, you may be given a full polysomnography examination. This is the main diagnostic tool at all sleep centres and will require you to stay overnight at the centre (see below).

Monitoring your sleep at a sleep centre

At a sleep centre you’ll be given a room and connected up to wiring that will measure your sleep. Many people worry that they won’t actually be able to sleep in these clinical conditions. However, with so much excessive sleepiness already clocked up, and the security of knowing that you’re in the process of finding out what’s going on so that you can finally take control of your sleep, you’ll probably have one of the best nights you’ve had in a long time. Certainly, in most cases, sleep at a sleep centre is no worse than it is at home.

Overnight monitoring involves three sets of basic wiring. First, you’ll need to have multiple electrodes (each smaller than a penny) glued to your face and scalp. These measure your brainwaves, eye movements and chin-muscle tone (during dreaming sleep the chin muscles become active). They provide all the information a sleep expert needs to map your journey through sleep’s main stages.

Technicians attach the electrodes to your scalp using a special glue. You won’t need to have any hair shaved and in my experience you’ll be combing glue out of your hair for a while after the sleep study!

Second, the centre needs to measure your breathing and oxygen levels. This may involve sensors on your nose (airflow) and fingers (blood-oxygen levels), and in chest straps (to record your breathing movements, including how deeply you breathe and how often).

Finally, as limb movements can disturb your sleep, further electrodes will be attached to your legs. You may have electrodes placed on any other part of your body that might be causing a problem, too.

All the wires connect up to a junction box somewhere near the head of your bed, in such a way that you’re able to turn over during the night. There may also be some camera equipment set up in the room, which will take video recordings of you as you sleep.

Diagnosis and treatment

Armed with such specific information about how you sleep, experts can usually work out fairly quickly why your sleep is not restful. They can then recommend an individualized treatment, using techniques best suited to your situation. These might include medical treatments, such as an operation to remove your adenoids or tonsils or excess tissue in your throat if you’re suffering from a breathing disorder, as well as treatments such as clinical hypnotherapy, which can help with overcoming certain insomnias and parasomnias; or cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (see box, p.222), which can help to change the way you think about your sleep.

COGNITIVE BEHAVIOURAL THERAPY FOR INSOMNIA (CBT-I)

Throughout the world sleep experts use CBT-I as a main treatment for insomnia. The objective is to modify the negative behaviours that lead to insomnia and to learn how to reduce the number of intrusive thoughts you have that inhibit your ability to sleep, as well as the anxiety you associate with sleeping.

As a first step, a therapist will ask you to keep a diary of your sleep and then your thoughts – whether they’re related to sleep, or any of the other things going on in your life – and your sleep. Once you’ve identified problematic thought patterns that might be interfering with your sleep, you can challenge them by replacing them with accurate beliefs (for example, changing a thought such as “I can’t cope if I don’t get a good night’s sleep” to “I’ll have a tired day if I don’t get a good night’s sleep, but I’ll sleep better the following night to make up for it”) and more realistic attitudes. Your statements may need to be related to a specific aspect of your sleep hygiene. For example, if you’re making negative associations with your bed, you’ll need to change your attitude so that you positively associate the bed with sleep. A therapist will help to show you how.

In general, positive statements about sleep help to give you reasons to start believing again in your ability to sleep. Simple statements such as “sleep is easy” or “I can sleep” can have a powerful effect when repeated over and over, every day, rewiring your brain to believe in sleep as something that comes naturally.

Some therapists use other psychotherapy techniques, such as distraction training and dedicated “worry time”, but whatever the methodology, the basic principle is the same – to turn all negative associations with sleep into sleep-inducing positive ones.

Covering all non-conventional medicine, complementary medicine includes natural treatments such as herbalism or natural supplements, non-Western medical systems such as Traditional Chinese Medicine and Ayurvedic medicine, as well as those that have been more recently developed, such as modern-day energy treatments.

As a scientist, I do not discount the power of the mind and of nature placebos do work (for some reason?!). However, in many cases there’s been little scientific rigour in the testing of whether or not complementary therapies have any worth in the sphere of sleep medicine. In order to recommend a treatment, I do need to know that it’s been scrutinized in a scientific way.

Amazingly, rigorous testing hasn’t extended to the scientific assessment of massage, osteopathy and homeopathy. This doesn’t mean that these therapies don’t work to promote sleep, just that there’s no available evidence that they do. There have been, though, sufficient studies to evaluate acupuncture and acupressure; the herbs kava (Piper methysticum) and valerian root (Valeriana officinalis) individually and in combination and a combination of valerian root and hops (Humulus lupulus); supplementation of tryptophan (an amino acid); and the mind–body practices of tai chi and yoga. Aromatherapy particularly lavender remains promising.

What were the outcomes?

The practices of acupressure, yoga and tai chi have shown positive support for dealing with insomnia, with acupressure coming out best. This involves a practitioner applying finger pressure to classic acupuncture points related to sleep (see box, above). Treatments generally last between six and eight weeks.

ACUPRESSURE FOR SLEEP

As part of your wind-down routine, try the following acupressure exercise to stimulate the sleep-sensitive acupressure points.

1. Use your thumb to press gently but firmly on the point between your eyebrows at the top of your nose, where there’s a slight indentation. Hold for 20 seconds, then release briefly, and repeat the pressure twice more.

2. Sit upright on the end of your bed and put your right foot across your left knee, supporting it underneath with your left hand. Keep your left foot flat on the floor. Find the slight indent on the top of your right foot between your big toe and your second toe. Use your right thumb to press firmly down on this point, until you feel a slight discomfort. Hold for 20 seconds, then release briefly, and repeat the pressure twice more.

3. Still supporting your right foot, find the point just below the nail on the upper side of your second toe. Using the thumb and forefinger of your right hand, gently squeeze the toe, applying pressure to this point. Hold for 20 seconds, release briefly, and repeat the pressure twicemore.

The mind–body therapies of yoga and tai chi had beneficial effects over a period of weeks. My favourite is yoga, as the discipline has three components that I think are fundamental to improving the quality of sleep. First, yoga involves various breathing techniques (see box, p.71, for one of them), which help to reduce heart rate and lower anxiety. Second, it encourages strength and flexibility, which are essential for releasing tension in the muscles and in this way helping to prevent aches and pains that might disturb sleep. And third, yoga encourages mindfulness – being fully present in the moment and so distracting the mind from any thoughts about not being able to sleep.

Finally, the results with tryptophan were inconclusive, although anecdotal evidence suggests that taking supplements of this amino acid may be of help. Herbal remedies need a little more explanation.

Herbal remedies

Of the herbs that have been rigorously tested, none have come close to standing up to scrutiny as a sleep treatment. Historically, though, many herbs have been put forward as treatments to help combat sleeplessness. I’ve listed these below, but note that jury is still out for their sleep-promoting qualities. Valerian (Valeriana officinalis, and see box, p.227, for a valerian bedtime drink) and Hops (Humulus lupulus) use is well-establised.

• Garden camomile (Anthemus nobile) and German camomile (Matricaria chamomilla) for anxiety and insomnia.

• Jamaican dogwood (Piscidia erythrina) for pain-related sleeplessness.

• Lady’s slipper (Cypripedium pubescens) for sleeplessness associated with anxiety.

• Lavender (Lavendula officinalis) possibly for sleeplessness in the elderly and for its potential antidepressant effects.

• Passion flower (Passiflora incarnata) for anxiety and insomnia.

• Peppermint (Mentha x piperita) for sleeplessness when you have a cold.

• Wild lettuce (Lactuca virosa) for insomnia (and reputedly used for this since ancient times).

• St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) for its potential to improve depression-related insomnia.

GADGETS, GIZMOS AND THE WORLD WIDE WEB

For most of the life of sleep medicine, gadgets and gizmos have been the province of research laboratories and sleep centres (see pp.192–8). Now, versions of these technologies are available for us to download or to buy and use in the home.

Devices are broadly those that track your sleep (trackers), help you get to sleep (mollifiers) and wake you up (grizzlies). Internet websites can provide a personalized sleep service to help you to monitor your sleep and find advice that’s unique to your own sleep situation.

Trackers

These range from those that are essentially simple diaries, recording the time you go to sleep and wake up, and asking for information about the quality of your sleep; to highly sophisticated devices such as the late Zeo (see box, p.228). Many trackers are available as straightforward smartphone apps, and many are free to download. Inevitably, some are more useful than others, but generally I recommend those that disconnect your phone from the network and shut down your connection to your Wi-Fi during the night. In this way you can make sure that you won’t be disturbed by late-night communications, but you can still use all the features of the app.

COOL VALERIAN ROOT INFUSION

Use the following “recipe” to make a valerian root infusion. However, please check with a qualified herbalist that the herb is not contraindicated for you first. Have one cup of the infusion as part of your pre-sleep routine every night for up to six weeks. Break for two weeks, then resume for up to another six weeks if necessary.

Crush 1 tsp of valerian root in a pestle and mortar and soak it in one cup of cool, filtered water for up to 24hours. Strain the infusion and drink cold.

Somewhere between these simple apps and the EEG lie trackers that measure your movement during sleep and match that to the phases of sleep. An accelerometer built into the app means that, once downloaded, the app allows your smartphone to monitor how much you’re moving about during the night and also works out when, once you’ve had your sleep quota, you’re in the lightest phase of sleep so that you can wake feeling most refreshed. If you don’t have a smartphone, you can find similar devices that you wear on your wrist.

All these devices have the advantage of allowing you to track your sleep more easily than you could by simply relying upon your memory of what happened overnight. In addition, as many of them link to websites that provide fully blown sleep diary functions, you can very quickly build up an accurate picture of your sleep quality and under what circumstances you sleep best.

Mollifiers

Your bedroom should be a place kept as technology-free as possible. However, mollifiers aim to improve your sleep hygiene, so they’re an exception to the rule. For example, if noise is keeping you awake, you can buy devices that play white noise, or neutral or pleasant sounds. Some come with earphones that go inside your ears, but I think those with a headband are more comfortable. In addition, those that detect when you’ve fallen asleep and then turn off automatically help to prevent continuous sound from disturbing your slumber. See pp.58–60 for more information on noise-reducing gadgets.

THE ZEO

Of all the devices on the market, the Zeo™ was the most remarkable and my favourite. It both recorded and analysed sleep via two small units: a headband with three silverized pads and a clip-on sensor, and a bedside unit that tracked data via a Wi-Fi link from the headband.

To use the Zeo all you had to do was put on the headband when you turned out the lights to sleep. The bedside unit displayed whether or not the connection was OK. In the morning, the headband and sensor were placed back on thedbedside unit, which automatically ended the recording and charges the sensor for the following night. How and what stages of sleep were displayed on the unit in the morning. All the information could be uploaded to the Zeo cloud and personalised information as to how to manage your sleep was sent back. It was good device but unfortunately the company went bankrupt.

Nightlights and dawnlights (that simulate dawn to wake you up naturally) also fall under the category of mollifiers (see pp.55–56).

If you don’t wake up naturally – as you reach the end of a sleep cycle after a full, refreshing night – you’re probably using an alarm (or have young children). Grizzlies are, essentially, alarm clocks. They vary in their gentleness and it’s up to you to decide whether you prefer a gentle rousing into the day or to wake up with a great clang. Personally, I like the idea of the alarm mat. You place it at the head of your bed and have to get your feet out and stand on it to turn it off – this means there’s no danger of simply ignoring the alarm or switching it to snooze without moving more than an arm.

If you and your partner need to wake up at different times, you could try a novel device that consists of two little rings – one for each of you – and a single dock through which you can programme each ring individually to vibrate at a certain time. When you go to bed, you each put your ring on the end of one of your forefingers. Your ring vibrates silently at the time you want to wake up, in theory waking you, but not your partner – or vice versa, depending upon who needs to get up first. The vibration stops when you put the ring back on the dock. Of course, whoever gets up first is still going to need to creep out of bed and get ready very quietly!

Finally, for some fun and to get your morning exercise in, you could try the alarm clock that comes as part of a dumbbell. You have to do the “repetitions” to stop the alarm from ringing!

Links and references for all these gadgets are given on page 234.

The World Wide Web

Since the time I wrote my first sleep help website 20 years ago, and since the Sleep Assessment and Advisory Service (of which I’m a director) began providing online as well as phone advice, there’s been a huge expansion in the numbers of sites providing information on insomnia, its causes and its cures.

I often have to work late at my computer and I know this is affecting my sleep. Are there any gadgets that can help?

If working late at a screen is completely unavoidable, you could try downloading a program such as “Flux” that automatically adjusts the brightness of your screen to mimic the ambient light in your office or study. Computer screens are generally programmed to assume you’re working in daylight. At night this can dazzle your eyes, making it hard to switch off when you go to bed. While dimming the screen using the brightness keys can help, online programs can adjust the screen so that it doesn’t simply get greyed out (and in the process becomes actually quite hard to focus on), but instead mimics the light you have around you. So, if you tell the program you’re working in an office with halogen light, it works out that it needs to adjust your screen from daylight to halogen light as darkness falls. The idea is that you aren’t bombarded with lux from your screen late into the night, which means that your eyes feel less achey and dazzled when it’s time to go to bed.

It has also been found that most smartphones and tables emit the “blue light” that most affects the retina and biological clock causing a major reset to the wrong time during the night. This has now been fixed by Apple and the other manufacturers are following suit.

A search I just recently made for “insomnia help” gave more than 58,700,000 websites to look at!

The growth of sleep medicine as a serious science in both the USA and Europe has led to lots of websites providing high-quality information, albeit all along the same lines. Now, simply through your computer, you can have a consultation or therapeutic session using video-communication software, such as Skype or Google Hangouts. Furthermore, there are lots of self-assessment programs and automated programs that deliver cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia. The Mood Gym is one of the earliest and best-established of these, but there’s also now Living Life to the Full, devised by Dr Chris Williams of Glasgow University. You can find the links for both these in the Resources section of the book on page 234. In addition, there are plenty of websites that deliver advice on how to beat depression and overcome anxiety, and even one specifically intended to overcome insomnia (again, see p.234 for links).

You’ll find overlap on most sites (depression and mood sites cover insomnia, too). Most cover topics such as emotional intelligence, managing stress, relaxation techniques, coping with difficult events, improving self-esteem and relationships, problem-solving, time management, positive thinking and, of course, sleep management.

The opportunity for taking control of your life – and your sleep – has never been greater or more accessible. All the websites listed on my resources page, and a wealth of others, can help you learn about what in your life could be affecting your sleep, and many offer sound advice on how to make effective changes that could change your sleep – and your wakefulness – for good.