SLEEP DISORDERS – STEP BY STEP

Since writing my first book on insomnia many years ago, there have been considerable developments in our understanding of sleep – and that inevitably means that we’ve learned a lot about insomnia, too. Over the following pages I shall introduce you to all the major sleep disorders, several different insomnias among them, tell you what characterizes them and give you tips on how to overcome them. A simple “Insomnia Matrix” helps you to unravel your symptoms to work out which disorders might apply to you.

Throughout the chapter it’s important to bear in mind that many sleep disorders can become or are from the outset serious conditions and you may need to seek individualized professional advice. If you’re at all worried, see your medical practitioner and, if necessary, ask for a referral to a sleep specialist. Almost all sleep disorders are perfectly treatable as long as you have the right level of support.

The second International Classification of Sleep Disorders list- ed 81 conditions that affect the quality of our sleep. Although this number is high, in effect the conditions fall into only eight categories:

1. Insomnias

2. Hypersomnias, including narcolepsy

3. Parasomnias

4. Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders

5. Sleep-related Breathing Disorders

6. Sleep-related Movement Disorders

7. Isolated Symptoms, Apparently Normal Variants and Unresolved Issues (basically the sleep-disorder loose ends)

8. Sleep Disorders Associated with Conditions Classifiable Elsewhere: psychiatric, neurological and medical. The advice to both tackle the other condition and add sleep hygiene or CBT-I.

The third classification has refined the second with fewer categories, a reflection perhaps that the number of treatments did not cover all the categories.

It would take a volume of books to cover all the sleep disorders in all the categories in full, so over the following pages I’ve selected the insomnias and sleep disorders for special treatment. I explain what each is, what causes each, and provide ideas on how to improve your sleep if you think one of them is affecting you. I’ve also presented some of the more unusual disorders – to illustrate just how diverse and how extraordinary your sleep is or can be.

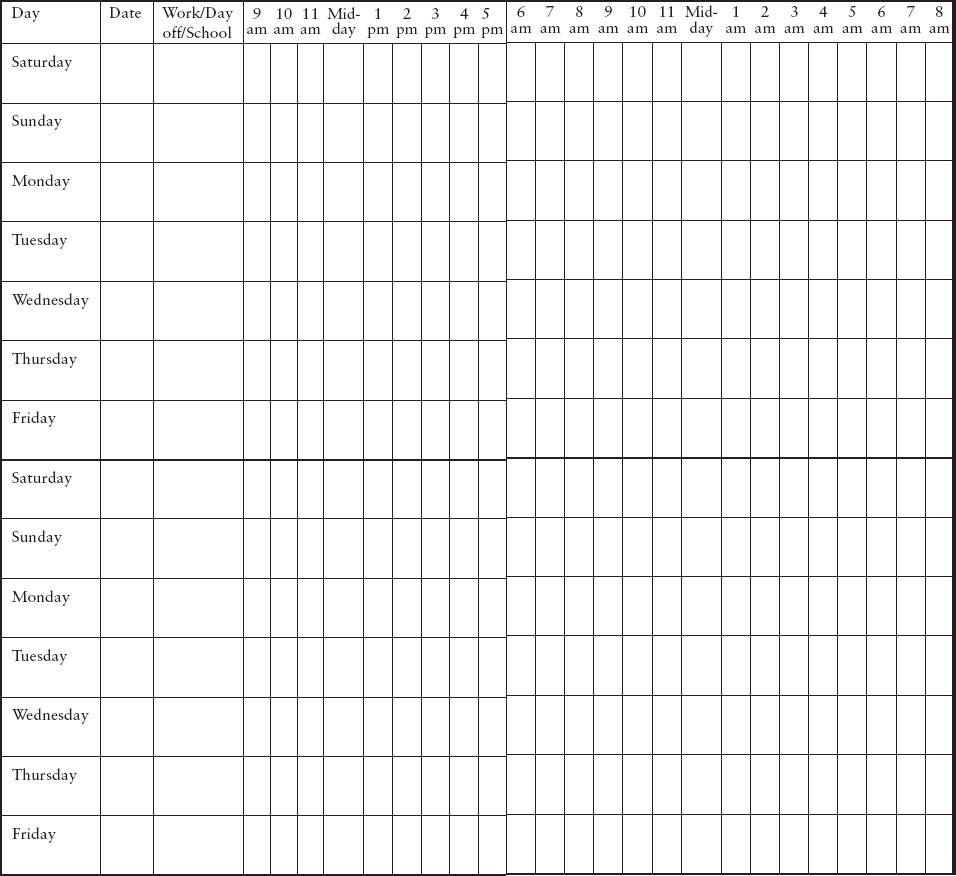

At several points in this chapter, I’ve suggested that you keep a sleep diary for two weeks in order to better understand your sleep problems and symptoms. There are some disorders for which it is especially useful to have a record of your sleep, but a sleep diary can help whatever you think the problem is. Use the template on pages 158–159 as a starting point, and add any columns you think you might need. For example, you might want to add a column in which to note whether or not you remember dreaming that night; or whether or not you experienced a recurring sleep disorder.

Sleep diary template: You can copy out the template by hand or reproduce it from here if you like. Keep the diary for two weeks in order to get a full picture of your sleeping and waking habits.

Filling in the grid

• Put a U in the box at the time at which you get out of bed.

• Put an S in the box that represents any time when you feel sleepy during the day (but did not actually nap).

• Put a heart in the box to show time you spend exercising.

• Put a dot in the box to indicate when you have any caffeine.

• Put a circle in the box when you have an alcoholic drink.

• Put a + in the box when you take any medication.

• Shade in any hours in which you take a daytime nap.

• Put a tick in the box when you go to bed.

• Put an R in the box for time you’re reading in bed.

• Put an F in the box at the time you estimate you fell asleep, and a W for the time you wake up. Use a solid line to indicate the hours of tranquil sleep and a wobbly line for broken sleep.

Insomnia is an umbrella term for several different conditions. These conditions are different from sleeplessness in that they develop over time. Insomnia might have developed as a secondary condition (that is, triggered by something else), or it might be “comorbid” – that is, it may occur at the same time as another condition, but not because of it. Often, though, insomnia has no obvious cause at all.

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine identified 11 types of insomnia in the previous classification but has now reduced the number to three: chronic, acute and other! In this book, I’ve covered the main ones from the previous classification over the following pages. Broadly, however, insomnia is pigeon-holed by the length of time it’s been going on (whether it’s acute or chronic) and by its sub-type (whether it occurs “early”, “mid” or “late” into the night).

In recent years, researchers have tried to identify how each type of insomnia develops, building up several layers of explanation. The explanations all begin with the simple idea that most insomnia is caused by hyperarousal, a state in which a person’s brain is simply too excited to sleep. In order for us to fall asleep, the brain has to go into a state of “de-arousal” or “sub-arousal”. If the normal processes that make that happen don’t work (in particular, if the brain can’t switch off from the “fight or flight” response), a state of hyperarousal can occur. We can be certain that hyperarousal is a problem for sleep health because medicines that reduce arousal – known as tranquillizers – and help to switch off the brain also help people to get to sleep.

Hyperarousal has several different psychological models, but fundamentally if you have insomnia, you’ll fulfil the following conditions:

• You find it hard to fall asleep or to stay asleep.

• You can find no obvious cause why you can’t sleep.

• You have impaired ability to function in your waking hours.

All the sections in this chapter deal with a specific type of insomnia, or a sleep disorder. In order that you can establish which of these sleep thieves might apply to you, I’ve created an Insomnia Matrix that asks broad questions about your sleep and wakefulness so that you can go on to read the advice most relevant to your situation.

The matrix on pages 162–163 is designed to help you decide whether or not you have an insomnia or another type of sleep disorder. In many cases your symptoms could result from several different disorders, some of which may occur as a result of or in addition to a general insomnia. Take time to look at the matrix and establish which disorders could be affecting you, then read the relevant pages for more information and tips on how to improve your sleeping life.

The matrix assumes that you have already established good levels of sleep hygiene (see Chapter 3), but that even optimizing every aspect of your sleep hygiene hasn’t resulted in any improvement in your sleep. Remember that insomnia is the result of chronic sleeplessness without known cause. If you know why you aren’t sleeping soundly, you have a sleep disorder (not insomnia) or other condition that’s affecting your sleep. Dealing with that will therefore inevitably help you to sleep more soundly. And, finally, there are many reasons other than a sleep disorder that may lead to tiredness – refer back to the boxes on pages 6–7 to make sure that none of those apply, too.

Using the matrix

Look at the column on the far left and find the statements that apply to you (some you’ll know are true only because your bed partner has told you so), then look across the matrix to see which sleep disorders or insomnias each statement may signify (denoted by a star). Make a note of the possibilities and then read those sections on the following pages for more information and advice. Bear in mind that it’s possible you have more than one disorder.

According to the definition set by the second InternationalClassification of Sleep Disorders, you have adjustment (or acute) insomnia when you aren’t able to sleep when you want to, but drop column know (or are fairly certain you know) why it is that sleep won’t come – that is, you know what’s stressing you out. For me, this is rather more like sleeplessness because, by definition, true insomnia has no known cause.

Causes

Studies indicate that adjustment insomnia affects between 15 and 20 per cent of adults every year. I think almost everyone is susceptible, although some are more susceptible than others. If you’ve had periods of anxiety or depression in the past, are prone to living by your emotions (good and bad) and find it especially hard to deal with stress, or unwind or relax, you may be more likely to suffer from this.

Moving to a new home and finding it hard to get used to, a personal loss, diagnosis of a medical condition, relationship problems, troublesome work colleagues or superiors, ongoing arguments with authority, as well as intense happiness, love or infatuation can all cause adjustment insomnia. You may find that your nighttime insomnia has a daytime counterpart in ruminative thoughts or worries, or an inability to focus on anything other than your anxiety or indeed elation.

Treatments

On the whole, adjustment insomnia disappears, and normal sleeping patterns resume, once you’ve dealt with the stressor, or have adapted to your new situation. In insomnia terms, you’re very lucky, because you know what the root cause of your problem is.

Importantly, try not to resort to artificial methods to improve your sleep. Alcohol, recreational drugs, so-called sleep medicines and even natural remedies for sleep do not tackle the root cause of adjustment insomnia. If it’s simply a matter of time to get used to living in a new house, functioning in a new environment and so on, speed up the process by making your new environment a more comfortable place to be. In a new home, hold a housewarming party, redecorate to your taste and so on. In a new job, arrange a social gathering with your new colleagues so that you more quickly feel part of the team. If personal matters, such as a relationship problem, personal loss or bereavement, are causing your anxiety, seek specialist advice or counselling so that by dealing with your emotions you tackle your insomnia.

IDENTIFYING STRESS-RELATED SLEEPLESSNESS

Disturbed sleep often arises from stress. You can check whether or not this is true for you by answering the questions below. The more “yes” answers you give, the more possible it is that stress is the primary cause of your sleeplessness. Take steps to reduce stress before establishing whether or not you also have a sleep disorder.

1. Have you experienced significant unintended weight gain or weight loss recently?

2. Are you putting weight on, particularly around your tummy?

3. Has your libido decreased, or are you too tired for sex? 4. Do you feel tense, especially in your neck, back and jaw? 5. Do you experience tension headaches? 6. Do you find that you’re more sensitive, irritable or easily frustrated than you used to be?

7. Do you have a general feeling of being overwhelmed by everything you’re dealing with right now?

8. Do you feel always overtired or exhausted? 9. Do you find it more difficult to make decisions and/or concentrate?

10. Do you forget things more often than you used to?

11. Do you find that you’re ill more often than usual?

12. Do you often feel anxious about things you can’t control?

13. Do you find yourself eating to cope with annoyances, or craving sweet or salty food?

14. Do you find yourself drinking alcohol to relax or smoking to deal with stress, or are you becoming dependent on illegal drugs or prescribed medication?

A word of warning: don’t let adjustment insomnia rattle on in the hope that it will cure itself. Although it is by definition a temporary condition, adjustment insomnia can herald the beginning of something more persistent. If your stressor causes your body to react with the “fight or flight” response – that is, an adrenaline surge that results in increased heart-rate, breathing, sweating and so on – and you don’t find effective ways to overcome that stress, normalize your adrenaline levels and establish a sense of equilibrium again, you may become preoccupied with your inability to sleep. In turn, sleep may become something that you feel you have to work at, rather than something that comes naturally when you feel sleepy. The result can be psychophysiological insomnia, the most common form of persistent insomnia, which I explain next. (Also, don’t forget good sleep hygiene!)

Also known as learned or conditioned insomnia, primary insomnia, chronic insomnia or the rather esoteric-sounding “functionally autonomous insomnia”, psychophysiologicalinsomnia is characterized by a racing mind that results from a combination of hyperarousal (when the body can’t wind down from the stress response) and learned associations that prevent sleep occurring. Most often sufferers become overly concerned with falling asleep, which results in them remaining awake instead. Sufferers are unable to identify any particular stress or anxiety that might prevent them from sleeping, other than the need for sleep itself. It’s thought that up to two per cent of people in the UK and ten per cent of people in the USA suffer from psychophysiological insomnia, and for reasons we don’t fully understand it affects women more often than it affects men.

Compared with normal sleepers, psychophysiological insomniacs pay attention to their sleep, and by extension their sleeplessness and the effects of sleep loss. Good sleepers have minimal “intent to sleep” – in other words, they’re more able to let go of wakefulness. A psychophysiological insomniac expends effort to find sleep; sleep is no longer the natural, automatic result of sleepiness but something that the sleeper has to work at.

Studies show that there are certain questions and anxieties that recur among insomniacs of this kind, including:

• Anxiety over the importance of sleep in order to function normally during the day. You might say such things as “If I don’t sleep, I won’t be able to do all the work I have to do tomorrow” or “I’m tired and irritable because I can’t sleep”.

• Breaking down old associations, such as the bed being a place conducive to a good night’s sleep, and replacing them with negative ones. You might say such things as “I can’t get into a comfortable position”, “I toss and turn because I’m so worked up that I’m in bed and not sleeping” and “I lie in bed trying harder and harder to fall asleep”. Similar shifts in association might happen with a bedtime routine – once a precursor to sleep, the actions instead herald sleeplessness.

For many, although by no means all, psychophysiological insomnia begins as adjustment insomnia (see pp.161–166), when a stressful event may trigger a short period of insomnia that then leads to overanxiety about sleep and so to psycho-physiological insomnia. For others, the worry about sleep develops slowly – even over months and years. Gradually sleep deteriorates until the goal of getting a “good night’s sleep” becomes paramount and, by a cruel irony, unachievable.

Effects

Psychophysiological insomniacs suffer from fatigue, poor concentration and low mood, and general malaise. They find not only that nighttime sleep eludes them but that daytime napping is impossible, too. In sleep centres, studies indicate that psychophysiological insomniacs have fewer hours of deep and dreaming sleep, reduced sleep efficiency and generally reduced numbers of hours asleep.

In the long term, the persistent lack of sleep and ongoing feelings of helplessness may all lead to clinical depression.

Treatments

Patients often tell me that they begin to sleep better from the moment they’ve made an appointment to see me. Others find that they get a good night’s sleep when they spend a night in a sleep centre. These consequences tell me two things. First, that overcoming psychophysiological insomnia is partly a question of taking control of sleep, believing that sleep will come because something has changed (making an appointment, passing sleep concerns on to someone else to deal with), and, second, in part the insomnia is related to associations my patients make with their beds (in the sleep centre beds, they fall asleep).

The key then is to start unravelling the negative associations you have with your bed and bedroom, as well as those you may have with your sleep routine and even with sleep itself. Doing so takes time, but the following can help to ease the process.

• Redecorate your bedroom or move around the furniture in it. Declutter the space (nothing on top of wardrobes or stuffed under beds) and treat yourself to some new bedding. This “new” space is one in which you’ll sleep well. At an extreme, you could treat yourself to a new mattress (see pp.54–8) or bed so that you break the negative associations you hold with the one you already have. However, note that psychophysiological insomnia is primarily about reconditioning your mind – this should be your first objective, and it needn’t be expensive.

• Change your bedtime routine. Although there are certain things that you have to do (locking the door, brushing your teeth and so on), try some alternative triggers as well. For example, if you’re used to drinking a warm cup of milk before bed, switch to a cup of herbal (uncaffeinated) tea instead. Valerian root has been shown to have some soporific qualities (see box, p.227). If you’ve been practising progressive muscle relaxation before you get into bed (see box, p.71), try autogenic training instead (see pp.80–81).

• Spend 20 to 30 minutes outdoors doing light to moderate exercise every day, not less than four hours before you go to bed. This helps to raise your mood, making you feel more positive about sleep. It’ll also release muscle tension so that discomfort doesn’t exacerbate your inability to get to sleep.

• Consider cognitive behaviour therapy for insomnia – in which a therapist teaches you coping strategies for your existing thought processes, as well as strategies for re-convincing yourself that sleep is in fact a positive, accessible state, rather than the elusive one it has become. As a first step, you can try the Stimulus Control method (see box on page 171).

Whereas psychophysiological insomnia is a learned insomnia (that is, it occurs because of your own anxieties about sleep), the following insomnias may be acquired as a result of genetics (traits you’ve inherited from your ancestors) or as a result of a life event that has caused trauma.

Idiopathic insomnia

Also known as “childhood onset insomnia”, idiopathic insomnia is one of the rarest forms of insomnia of all, affecting less than one per cent of the general population. It usually appears from birth, with babies finding it hard to settle at night and yet appearing drowsy and unfocused during the day. Its root cause continues to baffle sleep scientists, and although research into twins has suggested that the condition may be inherited, we’re still far from knowing for sure.

Investigations at sleep centres tentatively reveal that idiopathic insomniacs have trouble falling and staying asleep. Their sleep patterns show irregularities similar to those found in psychophysiological insomnia – fewer periods of deep sleep, disturbed sleep, frequent unexplained awakenings and so on – but they tend to be more severe. Brain imaging studies show that areas that are usually less active during sleep are more active, while those that should be more active during wakefulness quieten down. The result is that at night the idiopathic insomniac can’t sleep, while during the day he or she finds it hard to concentrate, and may suffer other cognitive problems. Because the condition tends to be present from very early on in a sufferer’s life, most sufferers find ways to live with it – adapting their lifestyles so that they achieve enough sleep in each 24 hours to function properly.

This is a good thing, as sleep experts can’t agree on the best way to treat the condition. Some find that cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia might work but because the insomnia is not the result of stress, or negative associations, or even poor sleep hygiene, there doesn’t seem to be a clear answer on what to do. Nonetheless, training the body to prepare for sleep, through establishing a clear and rigid sleep routine, is essential to minimizing the effects and ensuring that a night’s sleep is as good as it can be.

REMAKING ASSOCIATIONS

The following steps use “Stimulus Control” in which three simple instructions are designed to re-associate the bed and bedroom with sleep, and to help re-entrain your biological clock to the correct cycles of sleep and wakefulness. The method is very simple, and it works – so even though it might seem inflexible, stick with it and eventually you will see some results.

1. Go to bed only when you feel sleepy – not simply fatigued, but properly sleepy.

2. If after 20 minutes in bed you’re unable to sleep, get out of bed, go to another room, sit quietly doing nothing (no reading and certainly no television), and return to bed only when you feel that you’re about to fall asleep.

3. Use the bed and bedroom only for sleep.

You’ll almost certainly know how it feels to be unsure how long you’ve been awake during the night – although for sound sleepers any misperception is usually by only a few minutes. If you have paradoxical insomnia you’ll feel you’ve slept for very few hours when in fact you’ve slept for many. The problem might occur when two short periods of wakefulness are perceived as a single, long block. The disorder tends to begin during early adulthood and occurs in both men and women.

Paradoxical insomnia is a “sleep state misperception”. This form of insomnia became apparent only when sleep researchers started recording insomniacs. A small percentage were found to sleep for seven to eight hours a night despite reporting that they had slept for only one to two hours. However, their sleep was not refreshing.

Doctors once thought that sleeping pills were the only way to overcome this kind of insomnia. In fact, recent research shows that reducing the amount of time you spend in bed to just longer than the amount of time you perceive you’re asleep is the answer. You have to use your judgement to decide how long you think you sleep for, but if you think you sleep for only four hours a night, you would reduce your sleep time so that you spend five hours in bed. Lowering overall sleep time in this way in effect artificially manipulates your sleeping patterns. You’re awake for longer, so more tired when bedtime comes round. Then, when you do go to bed, your brain quickly finds deep sleep. Periods of deep sleep and dreaming sleep lengthen (to make up the sleep debt of the forced shorter night), so that when you wake in the morning, you feel generally more refreshed than when you spent more time in bed but believed you were sleeping less. Your actual sleep is deeper with fewer awakenings, so there are fewer moments between sleep cycles in which you believe yourself to be awake. Once you’ve restored your faith in the refreshing powers of your sleep, you can resume more normal sleeping–waking hours.

Fatal familial insomnia

Exactly as its name suggests, fatal familial insomnia (FFI) is an inherited condition (related to a particular gene) that can lead to death. It was the first “sleep disorder” that was found to be associated with a single gene mutation. The gene in question is the prion protein gene (PRNP), which is the same gene that can lead to CJD – Creuzfeldt Jakob Disease, the human equivalent of BSE (mad cow disease). Carriers of the abnormal PRNP gene are at risk of FFI, but developing the condition is not a certainty.

Studies show that the first sign of this extreme case of insomnia is dramatic weight loss, then a gradual worsening of sleep quality until eventually sleep won’t come at all. Damage to the thalamus, the brain’s main sensory highway and the area that partly moves into neutral and disengages us from the real world when we fall asleep, means that the sufferer gradually experiences difficulty in falling asleep and then maintaining sleep, ultimately leaving them in a perpetual state of wakefulness. In its later stages, the disorder causes sufferers to apparently enact dreams (although proper sleep won’t come) or become locked in a state of living stupor. Basic brain control systems fail, leading to problems with temperature regulation, sweating and salivation. Eventually, the vital organs start to break down, including the heart and lungs, which leads to death.

There are two forms of the insomnia and both are fatal, taking anything from six months to two years to run their course. In a single case study, one patient was able to undergo anaesthesia, electro-convulsive therapy and light therapy, and remained functional and able to write a book before he died, two years after first showing signs of the disease. Agomelatine, an antidepressant, which has a similar structure to melatonin, may normalize sleep for a time.

Another, similar form of this insomnia is called sporadic fatal insomnia and occurs when the prion protein gene mutates without any inheritance coming into play. In other words, scientists have found incidents in which people have died of fatal insomnia but have shown no inherited predisposition. In these cases the insomnia is caused by infection or arises simply for unknown reasons.

I want to stress that all kinds of fatal insomnia are extremely rare.

A form of hypersomnia (excessive sleepiness; see box, p.176), narcolepsy is characterized by sudden sleep onset. It occurs relatively rarely, affecting anywhere between 25 and 50 people per 100,000 depending upon which country you’re living in. Incidence is very low among Israeli Jews, for example, but higher among the Japanese. The reasons for this are not clear.

Sufferers may or may not feel warning signs that sleep is about to overcome them, but anyway warning makes little difference – falling asleep is impossible to prevent. There are two main types of narcolepsy: with cataplexy (sudden muscle weakness; see box, p.177) and without. Other symptoms may include terrifying hypnagogic hallucinations (see p.203), sleep paralysis (see p.205), automatic behaviour (when you do something and know you must have done it, but have no recollection of doing it) and disrupted nighttime sleep.

Most people first notice symptoms of the condition between the ages of 15 and 25 years old, although a second, smaller peak in cases occurs in people between the ages of 35 and 45, and near menopause in women. The first symptoms are excessive daytime sleepiness and irresistible sleep attacks, both of which might be exacerbated by high room temperatures and boredom.

Causes

Narcolepsy can occur in those with a genetic predisposition to the condition, but your genes don’t necessarily mean that you’ll definitely become narcoleptic – in fact the condition shows in only two and five per cent of those with a family history. Rather we think that in most cases viral assault causes an auto immune response that in itself destroys wakefulness-promoting neurons in the brain’s hypothalamus, which makes it much harder to stay awake. The virus breaks down the cells that manufacture hypocretin or orexin (the same thing with two different names), a form of small protein that allows your neurons to communicate with one another to regulate your sleep–wake cycle. Once these cells are destroyed, you become deficient in hypocretin and so susceptible to the sudden, uncontrollable need to sleep.

Narcolepsy is not only genetic, nor is it only an auto immune condition. We know, for example, that a small group of narcoleptics retain normal levels of hyopcretin and we’re still trying to get to the bottom of how their condition comes about.

Diagnosis

If you think you may have narcolepsy, read about the Epworth Sleepiness Scale on page 11. If you try the test and score higher than fifteen, it’s very likely that you’re experiencing excessive amounts of daytime sleepiness, to the levels we might expect in a narcoleptic.

In order for a doctor to make a diagnosis, he or she will look at your history of daytime sleepiness and may ask you to undergo daytime nap testing at a sleep centre. Taking on average fewer than eight minutes to fall asleep for a nap (indicating low “sleep latency”) and having two or more naps that begin with dreaming sleep confirms your diagnosis. The immediate entry into dreaming sleep helps to explain narcolepsy’s characteristic hypnagogic hallucinations. You may also need to give a spinal fluid sample from which doctors can measure your hypocretin levels: low levels indicate a high probability of narcolepsy.

Treatments

At the present time, most treatments for narcolepsy are pharma cological. A sleep specialist may prescribe stimulants to overcome daytime sleepiness, and other drugs to manage symptoms of cataplexy, if relevant. In some countries doctors prescribe amphetamines (as narcoleptics will need to take these for life, addiction concerns don’t apply).

OTHER HYPERSOMNIAS

Narcolepsy is just one kind of hypersomnia, but there are several others. They are:

• Idiopathic hypersomnia: This is excessive daytime sleepiness without an obvious cause. It is characterized by naps that don’t relieve sleepiness, increased “fogginess” when waking from sleep, and increased sleep time to up to 18 hours a day (or any combination of these factors). It usually develops slowly during adolescence, but affects only around fifty people in every million.

• Recurrent hypersomnia: This hypersomnia is characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness that may last for several weeks, and then go away. Over the course of a year, a sufferer may have several episodes, but at other times function perfectly normally.

• Kleine-Levin syndrome: This extremely rare syndrome causes 18-hour or more sleep episodes for long periods of time. These then resolve themselves and sleeping returns to normal, only to perhaps recur at a later date.

• Menstrual-related hypersomnia: This hypersomnia occurs in women, coinciding only with the time of the menstrual period.

• Behaviourally induced insufficient sleep syndrome: This is not a biologically related condition, but instead occurs when a person doesn’t allow themselves enough time for sleep. People who regularly work double shifts might fall into this category.

Although it’s almost inevitable that you’ll need conventional medical intervention to cope with the condition, it may be possible to help manage it at home. Try to make sure you stick to a firm routine of getting up and going to bed. Avoid caffeine (despite its stimulant effects, it gives you a short-term high and then a debilitating crash) and eating big meals and drinking alcohol, which will make you feel sleepy. Keep your room temperature on the cool side (wear an extra sweater if you feel chilly), and if you sense boredom creeping in, get up and take a short walk, or switch to doing something else for a while. Light exercise and fresh air will help to keep sleepiness at bay.

CATAPLEXY

Occuring in around two-thirds of narcoleptics, cataplexy is defined as muscle weakness that is triggered by laughter, joking, fear, embarrassment or anger. The emotional triggers are remarkably specific – anxiety, for example, is not a trigger, nor is sadness. When an attack occurs, you may feel anything from an inability to smile or move the muscles in your face to overwhelming weakness in the knees that causes you to fall to the floor, remaining awake and alert the whole time. Attacks usually last for a few minutes – sometimes more – and are often misdiagnosed as epilepsy.

Take regular naps if you can throughout the day, each lasting no more than 30 minutes. Talk to your employer and ask for flexible working or other ways in which you can optimize your working life while accommodating the inevitable limitations of your condition. Good employers will be sympathetic to your needs if you explain – do bear in mind, though, that there’s little published information about narcolepsy and you may need to explain a lot. You’ll need to tell your country’s driving agency about your condition, too. Support groups, such as Narcolepsy UK and Narcolepsy Network in the USA, will offer advice on how best to approach your boss and the authorities.

A parasomnia is quite simply an unwanted or unexpected behaviour that occurs during sleep. Almost all parasomnias tend to occur during deep or dreaming sleep. Parasomnias happen because sleep is not a single, unified state. During sleep some parts of the brain – particularly the rational parts – can be asleep, while those that control movement and the senses associated with movement can remain active. It’s similar to the experience of realizing you’ve driven a great distance on a quiet stretch of highway without any conscious recollection of what’s been happening on the road around you.

Almost all sleep disorders that are not classed as clinical insomnia, a sleep-related breathing disorder or circadian rhythm disorder, nightmares or narcolepsy can be said to be deep-sleep parasomnias. This class of sleep disorder includes:

• Confusional arousals

• Night terrors

• Sleepwalking

• REM behaviour disorder

• Bruxism (teeth-grinding)

They also include the more unusual sleep disorders, such as exploding head syndrome, sexsomnia and sleep-related groaning.

Although parasomnias may be frightening (in the case of terrors or sleep paralysis, in particular), they’re not inherently bad for your health. Bruxism may require you to see a dentist, but otherwise the problems are more to do with disturbed sleeping patterns – both of the parasomniac and of those sharing a sleeping space with him or her – and the resulting problems that such disruption might cause for alertness, focus and good mood the following day. It’s thought that around ten per cent of Americans are affected by parasomnias. Most of them are children, who are more susceptible because of the amount of processing, learning and rewiring going on in the young brain. The deep-sleep parasomnias themselves have no or relatively sparse mental content. Awakening someone from a parasomnia event will be difficult and slow.

Most parasomnias occur following a period of sleep deprivation – overtired children and adults will immediately dive into deep sleep, for longer than normal periods of time, in order to make up the sleep debt. Other triggers are stress and fever, and, in the case of adults, having drunk alcohol too close to bedtime. Many psychoactive medicines (medicines that cross the blood-brain barrier and act upon the central nervous system), most notably sleeping pills, can provoke parasomniac episodes, particularly episodes of sleepwalking.

Confusional arousals

These occur when you wake up or are woken from sleep feeling disoriented and anxious, often sitting up and possibly talking, shouting, crying or thrashing about, but making no sense. Within a few moments, although it may take as long as half an hour, the arousal passes and you lie back down again as if nothing has happened. In the morning, you don’t tend to remember the episode, although you might remember a brief moment of waking if you’re reminded of it.

Confusional arousals are especially common in childhood. They’re mainly hereditary – children of a parent who had these arousals frequently as a child are up to 40 per cent more susceptible. This rises to 60 per cent if both parents were sufferers. When confusional arousals occur in adults, they’re often associated with violent behaviour.

Gentle, soothing reassurances should help settle the sleeper back down without incident, and there’s certainly no benefit that we yet know of for waking him or her up.

Night terrors

Also occurring most often during childhood, and also mainly inherited, night terrors are sudden, terrified arousals from deep sleep that you then don’t remember in the morning. They usually occur during the first three to four hours of sleep and are distinct from nightmares, which occur during lighter, dreaming sleep and which the dreamer usually recalls on waking.

My wife says that I groan as I sleep. Am I just snoring or am I having a nightmare?

Snoring is a distinct sound, and if your wife is saying that you’re groaning, it’s possible that you have a rare parasomnia called sleep-related groaning, or catathrenia. Sounds range from groans to moans, hums, cracks, squeaks and even roars. The disorder mostly occurs in men, usually beginning in childhood or adolescence.

One way to be more sure of your diagnosis is to work out when the sounds begin and how long they go on for. Sleep-related groaning usually starts at about two hours into sleep (as we enter the first period of dreaming sleep), and each sound may last anything from a few seconds to a minute, as the sleeper is breathing out. Sounds tend to cluster, and each cluster may last up to an hour.

As for whether or not you’re having a nightmare, only you can really say – but sufferers of sleep-related groaning rarely have anguished expressions on their faces as they make their sounds, so I think it’s unlikely. Tell your wife that if she nudges you in the ribs to force you to change your sleeping position, you’re likely to stop.

Watching someone go through a night terror can in itself be a frightening experience. The sleeper may thrash, kick, scream and lash out, demonstrating a sense of panic that seems utterly real. He or she probably won’t know who you are if you begin talking to them.

Make sure the sleeper is safe, but don’t try to wake them. Stay close until the episode has passed (it may take anything from a few minutes to half an hour) and, only once you’re sure it’s over, gently rouse them from their sleep if you can. It’s thought that waking the sleeper at this point may help to prevent them going straight back into deep sleep with the possibility of another night terror episode. If the terror occurs at the same time every night, you could try waking the sleeper shortly before this time comes round. In doing so, you hope to break the cycle and this way prevent the night terror happening at all.

Sleepwalking

Although we call it sleepwalking, somnambulation is actually far more than just walking. Any complex, automated or instinctive behaviour that occurs when you’re fully asleep – from sitting up in bed, to walking into another room, to picking up the remote control and staring at the TV (with or without turning it on), and even driving a car (it has been known!) – falls under the umbrella term sleepwalking.

Sleepwalkers have no memory of their behaviour and are usually so deeply asleep during each episode that they’re hard to rouse, and may even become aggressive or argumentative if you try. Nonetheless, if the sleepwalker is in any danger (if, for example, he or she goes out to get into a car), it’s essential to prevent them from pursuing their mission.

Although sleepwalking occurs mostly during childhood (and children will usually grow out of it), it’s also one of the more common parasomnias for adults. The good news is that the only dangers it brings are the health and safety issues of what you might do while you’re moving and asleep. There are no links that we know of between sleepwalking and other, more sinister mental or psychological disorders.

If you want to encourage a sleepwalker back to bed, I’ve found that putting a rough, hessian-type doormat at the exit to a bedroom can help. The sensation of the mat beneath bare feet triggers the realization that this is the way out of the bedroom and hopefully results in an about-turn. If you yourself are a sleepwalker, try standing on the mat before you go to bed and saying to yourself, “If I feel this beneath my feet, I must return to bed!” Anecdotally, some people have found that a big sign on the bedroom door that reads “Go back to bed!” is enough to make the sleepwalker do exactly that. Behavioural approaches, such as both these, are better, in my opinion, than resorting to medication, although short, two-week courses of antidepressants have been shown to reduce sleepwalking episodes among students.

SEXSOMNIA

In recent years, I’ve been called as an expert witness in a number of sexsomnia cases. This rare parasomnia results in a person engaging in sexual activity during sleep that he or she doesn’t then remember. Sexsomnia occurs mostly during deep sleep, although it may also occur during light stages. Both men and women suffer, and even couples can together discover that they’ve been having intercourse in their sleep without realizing it. Sleep masturbation, sleep fondling, intercourse are all types of sexsomnia.

Owing to the delicate nature of the disorder, it’s essential that anyone who thinks they might suffer from sexsomnia takes steps to ensure they don’t endanger anyone else. Although sadly it’s virtually impossible to know you have the condition until you advance on another person, if you suffer from other parasomnias or have obstructive sleep apnoea, and are overtired or have drunk too much alcohol, you’re more likely to have a sexsomnia episode, too. Usual treatments for parasomniacs (see below), as well as clonazepam, a benzodiazepine medication (see pp.213–214), may help.

REM behaviour disorder

In normal periods of REM, dreams occur only in the sleeper’s imagination. We can do wonderful things in the world of dreams, but we act out none of those things in reality because the communication channels between our brain and our muscles have closed down for the night. For a person suffering from REM behaviour disorder (RBD) this natural and necessary breakdown in communication doesn’t occur, meaning that sufferers can act out their dreams. In many cases RBD sufferers become violent.

One possible explanation for RBD is that dreaming sleep switches on too early, before the previous sleep stage is fully over and while the brain is still in the process of creating the temporary state of paralysis that characterizes R sleep. Or, it might switch on too late, while the brain is beginning to start up communication with our muscles again. Either of these scenarios would certainly explain how RBD comes about, but we’re still a long way from being certain that one or other (or both) is what’s going on.

It’s thought that about half a per cent of the general population suffer from RBD. Initially, scientists believed that it affected mainly older men (around 90 per cent of cases occurring in men over the age of 50), but more recent research has shown that it may also occur in younger women. We don’t yet know why, except that RBD is also more common among people who take antidepressant medication – which tends to be women more often than men. Autoimmune disease such as multiple sclerosis or the combination of an autoimmune and inflammatory disease (such as arthritis), as well as narcolepsy and Parkinson’s disease, all seem to have links with RBD – but we’re still trying to resolve how these links work and what they mean. The good news is that as a disorder in itself, RBD is relatively easy to treat.

If you think you may suffer from RBD, you’ll need to see your doctor and visit a sleep clinic for a firm diagnosis. Only in clinic conditions can we determine that you’re suffering from lack of muscle paralysis during periods of R and therefore be certain that you have RBD rather than another parasomnia. Once diagnosed, your doctor will probably offer you psychoactive medication, such as clonazepam, which has muscle relaxant, anticonvulsive and sedative properties. This medication works in 90 per cent of cases to eradicate RBD altogether.

For your safety and for the safety of the people you live with, it’s essential that you seek help for this condition. In the meantime, remove all sharp objects in the vicinity of your bed, and don’t sleep in a loft bed or near a window. Until you’ve overcome the parasomnia, you must make yourself and those around you safe.

Bruxism

First described in 1907, bruxism is characterized by jaw clenching, and by teeth grinding that may or may not be noisy. It occurs mainly during light sleep and rarely during deep and dreaming sleep. Sufferers may experience an average of 170 episodes a night and in the morning may wake up with a headache and a tense, sore jaw, aching face muscles and even ear ache. Some of these symptoms can become chronic – lasting well beyond the waking hours and worsening over time. Of course, that’s not to mention the effects of wear on the teeth and jaw, and the fact that eating breakfast can become somewhat uncomfortable, or even painful. In the long term, bruxism can disrupt the sleep of both the sufferer and anyone with whom he or she shares a room. Three out of four sufferers report that they feel sleepy during the daytime.

Bruxism has interesting physiological effects on the body. At around four to eight minutes prior to an episode, your heart starts to beat more forcibly (as if you were preparing to fight or flee from danger), and then a few seconds before you start to grind your teeth, your brainwaves reach alpha-wave frequency – as if you’ve risen to wakefulness. However, this burst of alpha activity is too short to be scored as true wakefulness – it’s over within seconds, followed by another rise in heart rate and then the grinding and gnashing.

ABDOMINAL BREATHING FOR BRUXISM

Overcoming the habit of clenching your teeth is a good first step to reducing your likelihood of a bruxism attack. In this exercise, the in- and outbreath and the rise and fall of your abdomen are linked with letting go tension in your jaw. Practise it every day before you go to bed. You’ll need a paperback book.

1. Lie comfortably on your back on the floor on a large towel or a yoga mat if you have one. Place the book on your chest, then gently rest your hands, palms down by your sides on the floor.

2. Close your eyes and become conscious of how you’re holding your jaw – is it tight? Are your teeth clenched? Is your tongue rigid or loose inside your mouth? Try to release any tension in your mouth and jaw – you may notice a tingling sensation in your cheeks and temples as you let go.

3. Now turn your attention to your breath. Breathe in through your nose as far as you can. As you breathe in, become conscious of the book rising on your chest, then as the breath reaches your abdomen push upward, letting your abdomen rise slightly higher than the book on your chest. This fully expands your diaphragm. Hold for one second.

4. Breathe out through your mouth and notice how your abdomen and then the book lower. As you exhale, allow your lower jaw to fall open, consciously releasing any tension there.

5. Continue breathing in and out like this for ten minutes. Take care not to overbreathe (if you become dizzy, stop and breathe normally for a bit). After five to ten breaths you should feel the tension release from your whole face, as well as from your jaw.

The condition is surprisingly common with an estimated 80 to 85 per cent of the population clenching or grinding their teeth at some point in their lives. Studies show that bruxism is often triggered during periods of stress and anxiety, but there are other risk factors for the disorder. If you already have another sleep disorder, including snoring, obstructive sleep apnoea or another parasomnia, you’re thought to be at greater risk of developing bruxism, too. Smokers and heavy drinkers are also at risk, as well as those taking certain medications, including haloperidol, lithium, chlorpromazine and methylphenidate. Those who have epilepsy, Huntingdon’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and Tourette’s syndrome are also at risk.

Without a cure for bruxism, we need instead to look at ways to manage the disorder. There’s modest evidence that behavioural approaches can help. These include understanding the causes and the factors that exacerbate the condition and taking steps to reverse the habit of clenching and grinding the teeth. For example, some people find controlled abdominal breathing can help (see box, opposite on page 185). Improved sleep hygiene and any therapy that helps to relieve stress are also positive ways to help overcome bruxism.

In conventional treatment, a dentist can fit a mouthguard, a mandi bular advancement device (see p.200) or a bite splint to protect your teeth. In time we may also be able to prescribe devices that send an electrical vibration into the mouth to prevent grinding; solutions, however, are currently only at trial stage. Stress-relief medications and medications to regulate serotonin levels may also help.

General prevention and treatment for parasomnias

No matter what parasomnia you may suffer from, you’ll be unaware of what you’re doing and usually have no (or perhaps only patchy) memory of what has happened. If it’s your child who’s suffering, given that the episodes rarely cause any long-term stress or health issues, I recommend that you do nothing about them at all. By the time your child has reached young adulthood, it’s very likely that he or she won’t experience parasomniac episodes any more.

In adults the situation is more complex. While there appears to be no underlying health issue for most parasomniac activity, parasomniacs are potentially a danger to themselves and other household members. At the very least, they’ll disturb the sleep of those around them.

It may be possible to reduce the number of episodes in both adults and children by having good sleep hygiene. Take special care to:

• Create a well-defined and calming bedtime routine, so that bedtime is a happy, quiet and reassuring experience. (This goes for adults as well as children.)

• Make sure you spend some time relaxing and unwinding before you go to bed (stress might cause an episode).

• Avoid situations that might result in over-tiredness or sleep deprivation. This means having a sleep–wake schedule that you stick to every day of the week.

CIRCADIAN RHYTHM SLEEP DISORDERS

As we’ve already seen, the time at which each of us falls asleep is dictated by two main things. First, how tired we are, which comes as a result of our activity levels during the day, how long we’ve been awake previously and the efficiency of the previous night’s sleep and, second, the ticking of the biological clock.

Your biological clock runs slightly more slowly than real-time hours during the day, and speeds up slightly at dawn. The overall result is that the body is generally in sync with the 24-hour calendar day. If, however, the clock runs too quickly or too slowly, your body steps out of real time, and your sleep may not begin or end when it “should” – that is, the time that society or your lifestyle requires you to be asleep. It’s important to note that, once asleep, those with only a circadian rhythm sleep disorder and no other sleep disorder will experience normal sleeping patterns. In other words, it’s the sleeping and waking times that become a problem, rather than the sleep quality itself.

Circadian rhythm sleep disorders are also known as biological clock disorders and subcategorized as the following types:

• Phase delay, or delayed sleep phase type: the clock runs slowly and out of kilter, on a repeating pattern (a “fixed delay”), creating an extreme “owl” (see box, p.18).

• Phase advance, or advanced sleep phase type: the clock runs quickly and out of kilter, creating an extreme “lark”.

• Irregular sleep–wake type: the clock runs erratically, causing tiredness at inappropriate times, although in all the sufferer gets the “right” amount of sleep in 24 hours.

• Free-running (non-entrained) type: the clock always runs slowly (continuously delaying), so that the sufferer has no regular falling asleep time, nor wake-up time, as the biological clock delays the onset of sleepiness by a little more every day. It can take a couple of weeks for a sufferer to come back to a “normal” sleep time, and for the cycle of delay to start again.

• Jet-lag type: the clock runs at a different time to the local time zone (see pp.126–130).

• Shift-work type: the clock runs at a different time to the sleep–wake schedule as dictated by shift rotas (see pp.119–22).

Causes

Delayed, advanced, irregular and free-running disorders in adults can occur as a result of injury, stroke, disease or even genetic abnormalities that manifest only with age. Problems with receptor cells in the retina, the optic nerve, melatonin secretion, any of the pathways that transmit light information to the biological clock, as well as problems with the biological clock itself, are all possible causes.

In adolescents, the onset of phase delay is to do with growing up – a by-product of puberty (it may last for several years after puberty itself is over). The biological clock slows down, delaying the secretion of melatonin to trigger sleep. See pages 92–97 for more information specifically related to the sleep of adolescents.

Treatments

Unless it’s obvious which type of circadian rhythm sleep disorder you have (as it would be for jet lag or shift work), the best way to diagnose your problem is to keep a sleep diary for two to four weeks. Carefully recording your sleeping, waking and napping (if relevant) times, as well as the levels of daytime tiredness you feel, will help you to see whether or not you’re running slower or faster than the 24-hour clock. Once you have a better idea how your body clock is working, you can set about trying to reset your sleep–wake rhythm.

Making changes to a physiological problem with the biological clock, whatever its cause, is not straightforward, but the key is the use of light. This is because the biggest cue for the biological clock is changing light. Other cues, such as exercise and mealtimes, may help, but are less fundamental to how the internal clock keeps time.

An old-fashioned approach to resolving phase delay was to force the sleeper to push forward their sleep onset time by two to three hours a night until they arrived again at the “right” time for going to sleep – usually between 10pm and midnight. For example, if you don’t usually feel sleepy until around 2am, you’d spend several nights moving that sleep onset time on by two to three hours (so, 2am one night, then 4am the following night and so on, each time sleeping for the “right” number of hours), until you reached, say, a sleep time of 10pm. At this point you’d have reset your clock so that you fell asleep at the appropriate time. The problem with this approach on its own is that phase delay keeps going, and the desire to fall asleep late just starts all over again.

If, though, you can combine the approach with the use of bright light, you may be able to keep the new schedule relatively under control. So, choosing a period when you can dedicate several days to the sleep-onset process, reset your clock so that you fall asleep at an appropriate time. Then in the morning get good exposure to bright light (ideally sunlight) to help your body to embed the new schedule. As with coping with jet lag (see pp.126–130), getting up and out for a morning run or a brisk walk is a good start. You could also buy a light box– many light boxes are available that have been specifically designed to overcome this type of sleep disorder.

The system works the opposite way round for phase advance. Bring forward your bedtime by two to three hours every night until you have worked back to the appropriate time for going to sleep. To avoid slipping out of kilter again, expose yourself to bright light in the evening. This can be as simple as taking an early evening walk (or mid-afternoon in winter) or run (not fewer than four hours before bedtime), or flooding your home with light, even if it’s artificial. Again, a specially dedicated light box is ideal.

Free-running and irregular sleep–wake types simply have to adapt the principles for phase advance and delay so that they, too, begin to follow a clear bedtime and waking time. Do all you can to avoid napping, so that you’re tired at “normal” bedtime, and use light exposure to help.

In all cases, it can take several months for the biological clock to find its new, improved rhythm, so it’s essential that you’re prepared to stick rigidly for a long time to the schedule changes you put in place. Avoid using alcohol as a means to help you to fall asleep (see pp.74–76), and it may help to go caffeine-free (and avoid any other stimulants for that matter), certainly while you’re trying to reset your clock. Also bear in mind that some medications include stimulants and you may not realize that these are disrupting your ability to fall asleep. Talk to your doctor if this may be the case for you.

Finally, your doctor may advise that you take a melatonin supplement. There’s great debate about how this works and how effective it is, although on paper the signs are certainly good: the supplement resets the biological clock and may promote sleep at the appropriate time. I recommend giving this a go under professional supervision if the more natural, schedule-related efforts don’t work.

SLEEP-RELATED BREATHING DISORDERS

Although you might think that you breathe more deeply and peacefully while you sleep, generally the opposite is true. When you’re in non-dreaming sleep, your breathing does become more regular, but it’s also more shallow. An exciting dream may upset this pattern, causing sharper, more raspy and irregular breaths.

All this is perfectly normal, and shouldn’t disrupt your sleep or be any cause for concern. However, if, during sleep, your breathing is laboured or noisy (snoring), or if it’s very shallow (hypopnoea), or if you have short periods in which your breathing stops altogether (apnoea), and in any of these situations you wake up feeling unrefreshed, you may have a sleep-related breathing disorder.

Snoring

Many couples I meet resort to sleeping in different rooms when one of them is a regular snorer. Unfortunately, snoring is often as disturbing for the listener as it is for the sufferer, but that’s not the only reason to do something about it. The grunting sound can indicate several underlying conditions that it’s important you check out.

Snoring is the result of a vibration of the tissues of your airways as you sleep. This vibration occurs because you have some sort of respiratory obstruction – which might be anything from the build-up of fatty tissue around your throat to the result of sleeping on your back, which causes your tongue to drop backward and partially block your airways. Phlegm or mucus can also cause obstruction, which is why you might tend to snore if you have a cold.

Temporary (acute) snoring, with a distinct cause, such as tonsillitis or cold, is not necessarily a problem and will pass once the illness abates or has been treated. If you snore because of your sleeping position, usually an elbow in the ribs from your partner will soon put that to rights. However, if snoring is chronic – that is, it’s prolonged and sustained – you need to do something about it. Up to 40 per cent of chronic snorers have significantly disturbed sleep that negatively affects their mood, ability to focus and libido. Statistics also show that snorers have a ten-fold increase in the risk of a stroke. Furthermore, specialists in respiration believe that snoring may mask a more serious condition, such as obstructive sleep apnoea.

Obstructive sleep apnoea

When a total blockage of the airways causes your breathing to stop for ten seconds or more, you have obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA). OSA is probably the most prevalent sleep disorder of the 20th century – but it has been known for hundreds of years. Today, we estimate that around four in every hundred middle-aged men and two in every hundred middle-aged women suffer from OSA.

All manner of problems can cause the blockage, including anatomical factors such as collapse of your throat or pharynx owing to excessive fat around your neck, enlarged tonsils or adenoids, the base of your tongue being larger than normal, or having poorly aligned jaws. Smoking causes inflammation, swelling and narrowing of the airways in the throat, and various medical disorders can make the problem worse, including nasal congestion, hypothyroidism, acromegaly (too much growth hormone), vocal cord paralysis, Marfan’s syndrome (an inherited disorder of the connective tissue), Down’s syndrome and neuromuscular disorders.

What happens during OSA

During sleep, sometimes more than once every minute, the blockage obstructs your airways causing cessation in breathing. As soon as your body detects that it’s being starved of oxygen, you’re brought instantly into a lighter stage of sleep, or sometimes a very brief period of wakefulness, in order to restore normal breathing – if only temporarily. That little awakening is called an “arousal” – it’s not enough to wake you fully, but it’s enough to disturb your sleep. Clinicians grade OSA according to the number of times a night you experience an arousal:

• Five to 14 interruptions per hour: mild OSA.

• 15 to 30 interruptions per hour: moderate OSA.

• More than 30 interruptions per hour: severe OSA.

The unit of measurement for these breathing impairments is the “apnoea–hypoponea index”, and systems for measuring where you fall on the index vary from country to country. The gold standard for measurement is to use a polysomnography – a system available at sleep centres that records your brainwaves, eye movements and muscle tone during sleep. In addition, technicians can measure nasal air-flow, snoring, and blood-oxygen levels. If you have suspected severe OSA, you may be given a sensor kit to use at home, which measures nasal airflow and blood-oxygen levels, or chest straps to measure your breathing rate.

In some people OSA interruptions are so frequent that sufferers experience no deep sleep at all. The result is further fatigue, leading to reduced daytime performance, a general inability to concentrate, and excessive daytime sleepiness (given the term OSA Syndrome). In these cases activities such as driving are extremely dangerous. There are also physiological effects of OSA. Regular, intermittent breaks in oxygen to the brain can have lasting effects on the brain’s make-up, leading to a stroke. Breathing impairment is associated with major changes in blood pressure, and the entire scenario may ultimately lead to long-term damage in your heart, brain, and blood vessels.

The good news is that, once diagnosed, OSA is perfectly treatable. (Be aware that if you’re diagnosed with OSA, you’ll need to let your insurance company know, as well as your driving licence issuer.)

Other types of sleep apnoea

OSA is not the only form of sleep apnoea. The following are less common, but worth mentioning and certainly worth investigating if you think one of them is affecting you.

Central sleep apnoea occurs when the brain fails to send appropriate signals to the breathing muscles to maintain respiration during sleep. It’s often associated with a central nervous system disease that involves a blockage or infection in the lower parts of the brain.It can also occur in neuromuscular diseases that involve the respiratory muscles – I’ve seen it most in patients with multiple sclerosis.

OSA: SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

• Daytime fatigue and/or sleepiness

• Loud snoring

• Morning headaches

• A dry mouth on waking

• Irritability

• Changes in personality

• Depression

• Difficulty in concentrating

• Frequent visits to the loo at night

• Excessive perspiration during sleep

• Heartburn

• Reduced libido

Mixed sleep apnoea results from a mix of both central sleep apnoea and OSA. Usually the central sleep apnoea (which is not caused by any obstruction) is quickly followed by an airway obstruction. This is more common than central sleep apnoea, but less common than OSA.

Upper airway resistance syndrome (UARS) is a term that was coined by US sleep researcher and physician Christian Guilleminault in 1993. UARS is characterized by repetitive arousals from sleep that probably result from increasing respiratory effort during narrowing of the upper airway. While this may result in snoring, the condition is distinct from OSA and hypopnoea in that it doesn’t affect the levels of oxygen present in the blood. Because there’s no actual break in breathing, oxygen levels are maintained. Nevertheless, UARS patients suffer the same levels of effective sleep disruption as other apnoea patients. There is, though, much controversy among experts as to whether UARS is a specific syndrome or part of a spectrum of obstructive disorders affecting the upper airway.

OSA: WHO’S MOST AT RISK?

Evidence suggests that OSA is worse if you are elderly, male or overweight. As we age, throat muscle slowly turns to fat, which may begin to obstruct the airways. The reasons why in general men have a higher risk of OSA than women is not entirely clear. Post-menopausal women (who have proportionately lower levels of the female hormone oestrogen than women who are pre-menopause) are at a higher risk of OSA than younger women.

Weight has a significant influence on susceptibility to OSA. If you’ve already developed mild forms of the condition, be aware that only a one-per cent increase in body weight leads to a three-per cent increase in the risk that you’ll develop moderate or severe OSA. With a ten-per cent increase in body weight, the risk is six-fold. If you’re obese or have a collar size of greater than 40cm (16in), you’re particularly susceptible to OSA.

Treatments for sleep-related breathing disorders

If you suffer from any form of sleep-related breathing disorder, you should avoid alcohol and sleeping pills. These drugs dull your brain’s arousal mechanism, making it harder for you to have the little awakenings that are essential for your intake of oxygen. Alcohol also relaxes the muscles that may be obstructing your airways, sometimes making even mild conditions, such as snoring, considerably worse.

Optimize your sleep hygiene so that you have every chance of a good night’s sleep, despite your sleep disorder. Studies show that there are fewer incidences of OSA when sufferers are well rested.

If you’re overweight it’s essential that you lose weight, as this will almost certainly improve your chances of overcoming all kinds of sleep-related breathing disorder. Try some throat exercises, too, to tighten up the muscles in the back of your throat, helping to prevent collapse. See the box on page 198 for some exercises to try.

Thereafter, there are several medical devices (listed below) that your clinician may suggest for you, or you may require surgery.

Nasal airstrips

If you’re a snorer because you have restricted airflow through your nasal passages, you might find that nasal airstrips (available in most pharmacies) provide a simple and non-invasive solution to your problem. You attach the strips over the bridge of your nose, which has the effect of opening your nostrils and airways so that you can breathe through your nose more easily. Nasal dilators and saline sprays can also help by having the same effects.

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP)

A CPAP is a nose and mouth mask that is connected to an air blower. A common form of treatment for all breathing disorders, from snoring to OSA, it forces air into your lungs raising the air pressure (usually automatically) in your mouth, nose and throat just enough to prevent your airways from collapsing.Although initial CPAP devices (brought out in the early 1980s) were big and heavy, modern systems are often small enough even to be taken on aircraft. You may also hear it called an nCPAP (nasal CPAP, which covers just the nose) or a BiPAP (BiLevel Positive Airway Pressure), which adjusts the air pressure both for inspiration and for expiration.

The pitfalls of CPAP include:

• Nasal congestion and a sore or dry mouth

STRENGTHENING YOUR MOUTH AND THROAT

A study in the USA in 2009 revealed that a group of snorers and OSA sufferers asked to do 30 minutes of throat exercises every day for three months reduced their symptoms by almost 40 per cent. Practise the following once a day (you don’t have to do them all in the same session) and see if your symptoms improve over time.

1. Using your toothbrush, scrub away at the centre and sides of your tongue for three minutes a day. This action triggers the gagging reflex, which has the effect of tensing and releasing your throat muscles and tongue to help strengthen them.

2. Suck in your cheeks as hard as you can. Hold and release, then repeat. Do this for three minutes.

3. Put your index finger against the inside of one cheek and suck in the other cheek hard. Practise for three minutes on each side.

4. Lick the roof of your mouth with the tip of your tongue from front to back (as far as you can go). Do this for three minutes.

5. Open your mouth wide and let out a series of short “ah” sounds, followed by one continuous “ahhh”. Repeat for three minutes.

6. Place a deflated balloon to your lips, then breathe in through your nose and out through your mouth, aiming to inflate the balloon as much as possible with your out-breath. Repeat for three to five times, taking care not to overbreathe.

7. Chew your food on one side of your mouth and then the other. When you swallow, keep your teeth together and jaw closed.

• Chest muscle discomfort, but this goes away eventually

• Eye irritation

• Irritation and sores over the bridge of the nose

• Nosebleeds

• Upper respiratory infections

• A feeling of being closed in (claustrophobia)

However, the benefits far outweigh the pitfalls. Regular use of CPAP lowers raised blood pressure; improves concentration, alertness, productivity, mood and libido; restores normal sleeping patterns; and reduces anxiety. Your partner may get a better night’s sleep, too.

Once your sleep physician has prescribed a CPAP, he or she will select the particular device that most suits your condition; a suitably qualified technician or nurse will choose your mask. I often think the most important aspect of successful therapy is the mask fitting and education session. With the right mask, correctly fitted, you’re likely to have a comfortable night that means you wake in the morning feeling bright and alert.

Oral appliances

The term “oral appliance” (also used in dentistry) is given to any device placed in your mouth to modify the position of your jaw, tongue and other structures in the upper airways to reduce snoring and/or sleep apnoea. In the USA, the American Food and Drug Administration has endorsed more than 34 appliances for use in the treatment of OSA.

There are two oral appliances that are most commonly prescribed. It’s essential that if you’re to have one or other of them, the appliance is moulded, aligned and fitted properly for your mouth. This usually means that a specialist will take a silicone mould that gives accurate measurements of your bite and jaw alignment.

Tongue-retaining devices are useful for patients who have very large tongues, no teeth, poor dental health, suffer from chronic joint pain, or find their sleep apnoea is worse when they’re lying on their backs. They aren’t suitable for people who are more than 50 per cent above their ideal body weight, grind their teeth at night, or have chronically stuffy noses. The tongue retaining device is essentially a mouthguard with a polyvinyl “bubble” sticking out between the upper and lower teeth mould. You hold the device in place by slotting your teeth into the upper and lower mouthguard sections and then you place your tongue into the bubble. As you push in your tongue, a natural vacuum secures it in a forward position so that it can no longer fall back and cause a blockage.

Mandibular advancement devices combine a mouthguard and a dental brace, and attach to your teeth to position your jaw forward slightly as you sleep. The aim is to modify the anatomy of your upper airway, in order to enlarge it, or stabilize or reduce its collapsibility. In this way a mandibular advancement device may reduce snoring and relieve mild sleep apnoea. Some people find that their jaw aches after the first few nights of wearing the device, but usually any discomfort passes as you get more used to it.

Surgery

Snoring and milder forms of OSA may be caused by anatomical deformities that have been present since you were born or are the result of injury to your throat. For some this means that the most effective treatment is surgery. The procedure is most likely to be uvulopalatopharyngoplasty – something of a mouthful in itself! It’s a laser surgery that removes excess tissue at the back of the throat and in this way clears the airways. It can take a few weeks or more to get over the sore throat that results from the surgery, but the procedure is effective for up to 75 per cent of snoring cases. (More extensive surgery may remove the tonsils, adenoids, or tissue flaps, too.) If you aren’t keen on the idea, you may opt for a CPAP (see pp.197–199) instead.

A newer form of surgery is called the Pillar Procedure, which can be performed under local anaesthetic in only 20 minutes. Patients have three small staple-like implants put into the soft palate at the top of the back of the mouth. These implants reduce the vibrations that cause snoring and may help to reduce the level of collapse in the airways to relieve cases of mild OSA. If the procedure doesn’t work (not everyone’s anatomy is suited to it), surgeons can remove the implants.

In the mid-20th century, the Swedish neurologist Karl Ekbom clinically identified a condition that had been described in literature for centuries. He called it Ekbom’s Syndrome – the sensation of creepy crawlies scuttling over and inside the legs. The condition affects around ten per cent of the general population. Some people say the sensations are painful, jittery and tingly. Almost all say that walking around is the only way to relieve them. In sleep clinics we call this restless leg syndrome (RLS), the most common movement-related sleep disorder.

The sensations usually begin late in the evening or at any time until around midnight or just after. They aren’t felt just on the skin, but deep within the thigh and calf muscle, and around 50 per cent of sufferers feel them in their arms and through other areas of their body, too. Relief comes through movement and may last for up to 30 minutes before the sensations start again, eventually dissipating over a number of hours, often just as the early hours of the morning creep in.

Causes

We still don’t really know why RLS should occur when it does. It may be that we move around less toward the end of the day, so the leg muscles suddenly feel that they need to expend some energy. Some evidence suggests that RLS is caused by melatonin secretion (as darkness falls) itself.

I get RLS before I go to bed at night, but during the night I’m told that I also jiggle my ankles. Are the two related?

Very possibly. The majority of people who have RLS also have a condition known as periodic limb movements during sleep (PLMS), or nocturnal myoclonus. Usually the limb movements begin with an extension of the muscles of the big toe, which then becomes a flexing of the ankle. Some people even begin flexing their knee and hip. The movements of PLMS are usually not enough for you to become conscious of them, but they are enough to disturb your sleep and probably make you feel quite sleepy the following day. This is why it’s important to take steps to deal with the RLS, and so resolve the PLMS and restore better sleep.

The syndrome is partly inherited, with immediate relatives of sufferers being between three and five times more likely to develop it. However, it can also occur by itself, or appear in people who have kidney problems, peripheral nerve damage, coeliac disease or Crohn’s disease. Pregnant women often complain of it, although we think that it’s pregnancy that may reveal the condition or that RLS reflects poorer absorption of iron from the gut. In children, there appears to be a link with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

Finally, we also know that there’s a link between RLS and low levels of iron in the bloodstream. These levels don’t have to be abnormally low (you don’t have to be so deficient in iron as to be anaemic), just low, which means anything below 45 µ/L of iron in your blood. (Ask your doctor for a blood test to assess your levels of ferritin – the iron transporter.) Iron is also essential for the metabolism of dopamine, a neurotransmitter, low levels of which may also be indicated in RLS.

If you suffer from RLS, avoid alcohol and caffeine and generally make sure that you have good sleep hygiene (see Chapter 3). In particular, being overtired can exacerbate the symptoms. If your levels of iron are low, take a daily iron supplement, along with a dose of vitamin C to help iron absorption. However, note that it may take several months of supplementation for RLS symptoms to abate, because it takes this long for the brain to reorganize its iron stores.

If your symptoms persist and are frequent (which means that they occur every day), your doctor may prescribe you with medications such as dopaminergic agents, benzodiazepines opiods to help ease the symptoms.

ISOLATED SYMPTOMS, NORMAL VARIANTS AND UNRESOLVED ISSUES

This rather unwieldy name for a category of sleep disorders actually quite neatly sums up the miscellany that falls under it. Sleeptalking is one of the most common sleep disorders in this category, and affects most of us at some time or another, but isolated symptoms et al also includes other common issues such as sleep starts (the jerky movements we sometimes get as we fall asleep) and the rather more scary problem of sleep paralysis.

Sleep starts, terrifying hypnagogic hallucinations and false awakenings

Also known as hypnic or hypnagogic jerks, sleep starts are sudden spasms of the legs, arms, face or neck that occur as you fall asleep. Most people experience them at least once in a lifetime – often more. The spasms can be associated with a brief but vivid dream or with the illusion of suddenly falling. Other sensory flashes can occur, as well as complex hallucinations. None of these experiences is harmful and they are not an indication of anything sinister.