SLEEP, AGEING AND GENDER

Why do we say that if we’ve had a good night’s sleep we’ve “slept like a baby”? What is it about women that makes them more prone to complain about the quality of their sleep? And why is it that men are more often accused of snoring? Although we all sleep, the nature of our sleep changes over the course of our lives and shows different, traceable characteristics according to our gender. In this chapter I’ll answer not only the questions above, but also look at the sleep of teens and adolescents and of the older generation. I’ll reveal what it is about menstruation, pregnancy and menopause that can affect a woman’s sleep, as well as how a man’s sleep is affected by his levels of testosterone. And I’ll offer guidance on how to work with your age and gender traits to help you to achieve the best-quality sleep possible.

SLEEPING BABIES, RESTED CHILDREN

During the early months after birth, a baby’s rate of learning is faster than at any other time in his or her life. This means that babies need a lot of time to process new information: they need a lot of sleep.

Baby sleep is “polyphasic” – that is, babies don’t have a single, long period of sleep as adults do. Rather, their sleep is broken up into several distinct periods over the course of 24 hours. Once they reach two to three months of age, most babies will take their longest sleep during the night (still waking for feeds, but going straight back to sleep again). However, it’s also normal for babies to take up to a year to get the hang of sleeping through the night. By their first birthdays, though, most babies are sleeping between 9 and 14 hours at night, with one long nap of between one and three hours immediately after lunch. (It’s important to emphasize that there are no rights or wrongs in the early stages and what works for one tiny baby may not work for another.)

A baby’s sleep cycle is not 90 minutes, but 45 to 60 minutes, gradually extending to the full 90 minutes by the time the child is about four years old. Also, unlike an adult’s, a newborn’s sleep is made up of only two sleep phases – non-REM and REM. Each sleep cycle is divided roughly evenly between the two phases at first. Then, periods of REM gradually reduce and non-REM gradually increase, until all the sleep phases kick in along with the 90-minute sleep cycle at around four.

Establishing good sleep health

In the first few weeks and months of a baby’s life, there’s no question that a baby’s sleeping pattern can seem erratic, even untraceable. My advice is that once your baby reaches six to eight weeks of age you try introducing some early principles of “nighttime” behaviour.

• Implement an evening pre-sleep routine – for example, give your baby a warm bath and then dry and dress him or her in a dimly lit room before settling down to the bedtime feed. Aim for the routine to be well established (even if it’s not yet fully effective) by 12 weeks.

• Avoid stimulating activities in the last hour or so before bedtime and make an effort to talk more quietly. You could even spend some time softly singing your favourite lullabies. Your baby will soon come to associate them with sleep time.

• Try not to allow your baby to fall asleep while feeding – put the baby on his or her back into the cot or crib while drowsy but still awake. (This is important for establishing a pattern of self-soothing. If the baby is used to dropping off to sleep in bed, rather than in your arms, he or she will be able to soothe him- or herself back to sleep following a momentary period of wakefulness during the night – instead of crying out for you.)

• Remember that tiny babies do not cry to be manipulative – they cry because they need something (food, love, a nappy change or, indeed, sleep itself). If your baby wakes during the night, keep the lights off (or very low) and avoid talking. Soothe with gentle caresses and put the baby back to bed.

As your baby grows into a toddler and then a pre-schooler, you can add layers to your bedtime routine – a story, for example, for the toddler and tooth-brushing for the pre-schooler, or saying good night to a special teddy. As long as the routine is the same every night, your child will soon make the association that this pattern of behaviour is the preamble for going to sleep.

Childhood sleep problems

It’s perfectly normal for children to experience some degree of sleep problem during the first years of their lives – for example, approximately 30 per cent of families will have a problem with a baby crying during the night. Common childhood sleep problems include difficulty going to sleep and frequent nighttime waking. Problems were formally categorized in the third International Classification of Sleep Disorders as Behavioural Insomnia of Childhood (see box, pp.88–90).

SLEEP CLINIC

Should I let my new baby sleep in my bedroom and, if so, should she be in my bed?

Overwhelming evidence suggests that having your baby in your room until he or she is six months old reduces the incidence of SIDS (“cot death”) by up to 50 per cent. No one knows for sure why this is so, but it might simply be that we are more attuned to our baby’s breathing rhythm (and so notice if there is a pause in it) and murmurings if he or she is nearby. As a result, I strongly advise keeping your baby in your room with you for the first six months.

Keeping your baby in your own bed is called “co-sleeping”. There’s a great deal of controversy over whether or not this is suitable and safe for the baby. The pros are that it’s much easier if you’re breastfeeding to have your baby in bed with you, and some believe that babies who co-sleep grow up feeling more independent and secure. For the cons: if you’re a particularly deep sleeper, you or your partner smoke (or you smoked during pregnancy), you’re taking any medication or you’ve drunk any alcohol before bedtime, there may be an increased risk of rolling on top of the baby, putting her at risk. My advice is that you consider all the evidence for both sides and make a decision that best suits you and your family. If you’re still unsure what’s best, you could invest in a cot that has a drop-down side, enabling you to put the baby up against your bed accessibly, but still in her own safe space.

Interestingly, most of these sleep problems in infants and pre-school children do not have a physical origin, but are behaviourally based: they result from poor sleep habits or training.

Prolonged poor sleep quality, or disrupted sleep–wake schedules, can impair a child’s short- and long-term memory, attention span, academic performance and ability to undertake complex tasks. Recent studies show that children with reduced sleep duration are more likely to be overweight or obese and have problems regulating their insulin and glucose levels (the precursor to metabolic syndrome, which can in turn lead to type II diabetes). Children who sleep for fewer than ten hours a night may have an increased risk of injury than longer sleepers – probably because a child’s balance, agility and coordination suffer when he or she is tired. Finally, a child who has not had enough sleep will be more aggressive, irritable and emotionally fragile. Over time, too little sleep may even result in clinical behavioural problems (such as hyperactivity disorder). None of this is all that surprising, of course, because these responses to lack of sleep are on a par with those we would expect for adults who clock up too few hours of slumber.

CLASSIFICATION OF CHILDHOOD SLEEP DISORDERS

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine published its second International Classification of Sleep Disorders in 2005. The categories of childhood sleep disorder are given below, with some suggestions for how to overcome them. They are considered disorders only when they persist for a prolonged period of time and significantly disrupt the sleep of both your child and you.

Sleep Onset Association Disorder This refers to when a child has learned to fall asleep only when certain conditions are present and only with your intervention – for example, if your baby falls asleep only if you’re rocking or feeding him. During the night when your son or daughter experiences a “normal” awakening at the end of a sleep cycle, he or she isn’t able to self-soothe back to sleep.

Solution: Encourage self-soothing. Put your baby to bed when he or she is drowsy but not fully asleep. For both babies and older children, use the “camping-out” method (see box, p.91–2).

Limit-setting Sleep Disorder This disorder occurs more frequently in pre-school age or older children and is characterized by your child refusing to go to bed, even when you repeatedly call for bedtime. It’s estimated that between 10 and 15 per cent of toddlers and pre-school children resist bedtime in this way.

Solution: It’s never too late to establish a bedtime routine and to adhere to a strict bedtime. Schedule some wind-down and settling time to help him or her prepare for going to sleep. If routine isn’t the problem, you need to be firm.

Every time he or she gets out of bed, take your child back lovingly but without talking. Eventually, children learn that it’s very boring to resist. Occasionally, restless leg syndrome (see pp.201–13), asthma or certain medications can cause this disorder, so if you’re concerned, see your doctor.

Adjustment Sleep Disorder This disorder (which occurs in adults, too, as adjustment insomnia; see pp.161–166) is often the result of stress or illness. It may appear when families move house, for example, and the child finds it hard to adjust to new surroundings.

Solution: Go back to basics – follow a clear pre-sleep routine and ensure that your child is going to bed tired or drowsy, but awake. If necessary, use the “camping out” method to restore feelings of security and with them a “normal” sleeping pattern.

Environmental Sleep Disorder Too much light or noise, being too warm or too cold, having a TV in the room and so on can all disturb a child’s sleep, leading to this chronic sleep problem.

Solution: Read pages 42–5 on how to promote the best sleeping environment – the information is as relevant to your child as it is to you. Improve as many of these environmental factors as you can.

Inadequate Sleep Hygiene Good sleep hygiene promotes sleep by reducing environmental stimulation and increasing relaxation – without these triggers your child may find it difficult to go to sleep, both at bedtime and when he or she wakes up naturally during the night. New and unexpected events; anxiety; excessive noise, cold or heat; vigorous exercise; hunger or large meals; pain and so on – all such factors contribute to poor sleep hygiene in children.

Solution: Establish a pre-sleep routine. Plan bedtime activities carefully – choose those that have a calming influence. Story-telling may be a tranquil activity, but unfamiliar stories or books that make noises may be too stimulating. Try to keep bath time softly lit, with gentle play rather than vigorous splashing. Save a special toy for cuddling at bedtime, or offer a comfort blanket that stays in the cot or bed so that its associations are only with sleep. And, just like adults, children need a comfortable bed within a secure, quiet environment at a cool temperature – layers of cellular blankets are better than duvets for babies and very young children.

Sleep training – getting it right

Training a baby or young child to sleep through the night can be a stressful experience for parents. Apart from wanting the best for the baby, parents need their sleep, too. In the very first weeks, allow the baby to sleep as and when he or she needs – and you should nap at those times, too. Once you reach the 8- to 12-week mark, though, you can start to teach your baby the difference between night and day, and he or she may begin to respond accordingly.

CAMPING OUT

The following steps set out a version of the “camping out” method for encouraging a young child to sleep through the night.

1. Set up your baby’s room so that you have a comfortable chair next to the cot. Place your baby in the cot while drowsy but still awake. Sit in the chair and gently stroke or pat the baby until he or she falls asleep. Avoid talking and eye contact, but do utter soothing “shhhh” sounds. If the baby wriggles out of his or her sleeping position, put him or her back gently, without talking.

2. Once your baby is asleep, creep out of the room. If he or she wakes during the night, repeat the patting and stroking without at any point lifting the baby out of the cot.

3. Once your baby has become used to falling asleep within a few minutes with you patting, stroking and saying “shhhh”, repeat the process, this time without any physical contact – sit next to the cot and say “shhhh”. This way the baby gets used to your reassuring physical presence and the soothing sounds, but without any actual touching. If the baby wakes in the night, sit beside the cot and soothe with a “shhhh”. Increase the intervals between the first cry and the moment at which you go to soothe.

4. Once the baby is used to falling asleep this way, move the chair farther from the cot. Repeat step 3 from this increased distance. On each consecutive night, move the chair closer toward the door, until you can soothe from outside the room. During night wakings, soothe from your new position and again increase the intervals between the first cry and your response.

5. Be patient. It may take three or four weeks to get to the point at which your baby or young child goes to sleep without any reassurance from you and is able to sleep through the night (most babies will still have the odd blip).

It goes against our most basic human instincts to leave a baby to cry, although the “crying it out” method is one approach to teaching a baby to self-soothe. It utilizes a psychological method that is clinically known as “extinction” – if the baby gets no attention as a result of a certain behaviour, eventually he or she gives up and stops repeating the behaviour (in this case crying). The approach may seem harsh (certainly, there are strong arguments against using it), and it takes enormous will power on the part of the parents to persevere to the point of success. Many parents find controlled crying a more palatable way to overcome nighttime waking, or “camping out”, which can be a lengthy process, but altogether less stressful and yet equally effective. See the box, opposite on page 91.

In the world of sleep medicine, adolescence lasts from around 12 years old until the ages from 22 to 25. I doubt if many 25-year-olds would consider themselves “adolescent”, but in sleep terms it takes this long for sleeping patterns to mature.

By the time children reach school age, and until they begin to enter puberty at around 12 years old, they need around ten hours sleep in every 24 hours to optimize their physical and mental functioning. At puberty, this need falls slightly, to just over nine hours sleep a night.

The problem is that at the same time the pubescent body clock begins to operate on a go-slow. During adolescence the body’s circadian rhythms enter “phase delay”. Melatonin secretion occurs much later than is “sensible” for someone who needs to clock up nine hours of sleep, but who also needs to get up early to go to school (or to work) five or six mornings out of seven. If you’re a parent to a teenager, it may come as a relief to know that your apparently rebellious son or daughter is not staying up late as an act of defiance. Even if he or she went to bed at 9pm, they would probably still be awake at 11. Nor are teenagers simply lazy: having to be coerced out of bed on days when they have to go to school and sleeping in late at the weekends are merely the body’s way to try to make up the sleep deficit when it can.

One recent study revealed that 85 per cent of 14- to 16-year-olds make up their sleep debt at the weekend. Although this seems a sensible approach to making sure adolescents get enough sleep over the course of a week, failing to keep to regular sleeping and waking times affects overall sleep hygiene and exacerbates the underlying problem with the teenage body clock. It’s much more important to try to keep to a regular sleep–wake cycle, both during the week and at weekends. Scientists have seen some success with light–dark therapy helping to reset the teenage biological clock. Have a look at the box overleaf to see if its advice could help you.

Nonetheless, lack of sleep is a problem for so-called tweens. In a study by the National Sleep Foundation of the USA in 2006, 70 per cent of adolescents who said they felt unhappy or even depressed also reported that they weren’t getting enough sleep. Whether the lack of sleep leads to a lowered mood or vice versa is the subject of much debate, but it’s commonly accepted that tackling the sleep deficit by attempting to get nine hours sleep a night is the best way for adolescents to begin to lift their mood. Interestingly, boys tend to become more sleep-deprived than girls.

RESETTING THE CLOCK

In order to overcome the problems associated with phase delay, so that you are, or your teenager is, better able to go to bed at a reasonable time and not feel tired in the morning, try the following light-therapy exercise, which brings bedtime and the morning alarm forward in 15-minute increments. The following assumes the need to get up at 7am, and therefore go to bed at 10pm – your own timings will vary with age and circumstance. You’ll need an alarm – ideally, a dawn simulation alarm clock (see Resources, p.234).

1. For the first morning, try to choose a day on which it’s OK to get up at 8am – so perhaps a weekend rather than a school or work day. On the previous night, set the dawn alarm for 8am. Assuming that it’s dark outside and you aren’t bothered by the noise or streetlight, leave your curtains open. (If that’s not possible, or if dawn would be earlier than 6am, ask a willing accomplice to open your curtains at 6am.) Go to bed at 11.30pm. Although this is too late in the long term, it’s counterproductive to associate bed with wakefulness, so it’s better to go to bed when there’s a high probability that you’ll go to sleep.

2. In the morning, get up as soon as either the dawn wakes you or the alarm goes off. Once you’ve begun to wake naturally before the alarm, bring your bedtime and your alarm time forward by 15 minutes – with bedtime at 11.15pm and the alarm set for 7.45am. Repeat the process until you’ve brought bedtime forward to 10pm and the alarm to 7am. By this point, you should have entrained your body to feel sleepy at ten, and wake naturally by seven. It may take time, but with perseverance (and an understanding teacher or boss), you’ll get there if your genes let you.

Of course, delayed melatonin secretion is not the only reason that teenagers and young adults don’t get enough sleep. The adolescent lifestyle often makes the problem worse. After-school or after-work activities (from football to parties) may be responsible for late nights, especially during the school years when there’s homework time to consider, too. Similarly, in-room TV and games consoles make the bedroom a place of activity rather than a place conducive to rest. If a member of your family is finding it hard to sleep, make sure that the TV and games consoles are out of bounds for at least two hours before bedtime. Try to keep activity schedules within sensible levels – after-school or after-work clubs once or twice a week, as well as a single night out with friends on a Friday or Saturday, should be the most any adolescent should attempt during a single week if he or she wants to be able to get enough sleep, too.

The issues for lack of sleep

You might ask whether or not it really matters if a teenager or young adult has a sleep deficit. The answer is yes, it really does. Apart from the increased risk of depression, and the need to establish good sleeping habits by the onset of adulthood, adolescents who don’t get enough sleep are also more likely to lack concentration, be more irritable or moody, be increasingly clumsy and hurt themselves, and fall asleep during classes or at work. Alarmingly, under-25s cause more than half the road traffic accidents that occur in the USA as a direct result of the driver’s sleepiness.

The solutions

If you’re a parent, encourage your son or daughter into a weektime activity schedule that isn’t crammed full with evening commitments. Encourage good sleep hygiene, including making sure that they have a bedtime routine and that they go to bed and get up at roughly the same time every day – even at the weekends.

SYNAPTIC PRUNING AND SLEEP

In 2004 the US Department of Health funded an investigation into how children’s brainwaves change between the ages of 9 and 14, including while they sleep. It found that age (rather than any hormone release or “sexual maturation”) triggers the onset of something called synaptic pruning – a process in which the brain’s numerous synapses (the bridges that pass information from one neuron to another) are reorganized and pared down to adult levels. The result is a brain with fewer connections, but with a faster, more efficient and more powerful processor. This natural occurrence is thought to begin at around age 11, and coincides with a decline in delta-wave (deep) sleep. By the time children reach 14 years old, their deep sleep hours have reduced by around 25 per cent. Although the same overall decline in deep sleep occurs in both boys and girls, girls tend to begin the process of brain maturation (and so loss of deep sleep) earlier than boys.

Research shows that youngsters sleep less if they have a TV, computer or other gadget in their bedroom. If possible, keep all this gear out of the bedroom, but if you can’t, then divide the room up so that the bed is clearly reserved for sleep only. Loft beds are great for this: the space underneath the bed becomes a “room” in itself, suitable for activity, while climbing the ladder to bed provides a physical barrier that demarcates the difference between waking space and sleeping space.

Teens with cell phones will often not be parted with them. Insist on the use of an app that acts as an alarm clock, but also can be set to automatically cut the link with the telephone network and WiFi. Alternatively, turn off the phone and use an app that monitors whether or not it is turned back on again.

If you’re at the upper end of the “adolescent” age range, the same applies – but, assuming you have no on-hand parent to keep you in check, you simply need to be firm with yourself.

Trying to categorize the changing quality of sleep over the course of life is as difficult as categorizing sleep itself. How we interpret the quality of our sleep has so much to do with what we expect from it that we first have to consider what the “norms” are for our stage in life. For example, a 20-year-old who wakes early in the morning might say that he or she has had a bad night’s sleep or is not getting enough sleep. When that same 20-year-old reaches the age of 70, early waking might seem normal and acceptable – the problem instead might be falling asleep or frequent wakings during the night.

As it is, age seems to affect only a few sleep variables, and the generalization that older people sleep for fewer hours because they need less sleep is simply untrue. In the general population older people may sleep less because of the various health burdens associated with advancing years (including pain that keeps them awake, problems with mobility that make turning difficult, having to go to the loo more often during the night and so on), but in extremely healthy people over the age of, say, 60 there’s actually little to distinguish an older person’s sleep from that of someone who is younger.

There are a few generalizations we can make, though, about sleep over the course of our lifetimes:

• Deep sleep is deepest in children.

• The biological clock tends to speed up a little as we age, which means that the elderly tend to feel sleepier and fall asleep earlier than the rest of the population – but that also means that they wake up earlier.

• The biological clock may have a less regular or weaker rhythm in older age – but we need further research to confirm this.

• Older people are less tolerant of jet lag or shift work… but they are more tolerant of lack of sleep and sleep disruption.

• Although healthy older people retain the same levels of dreaming sleep as younger people, they remember fewer of their dreams, particularly their napping dreams.

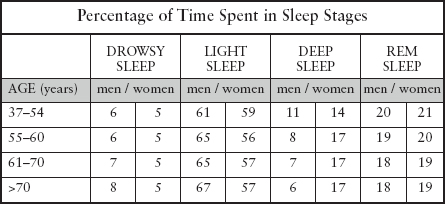

The table opposite shows how sleep changes between the ages of 37 and over 70 years old in both men and women, by looking at each sleep stage as a percentage of the overall time asleep. This is known as your sleep “architecture”. The table shows that the biggest difference over time occurs in men’s sleep, with deep sleep reducing by almost half during the course of those 35 or more years.

Apart from the gender-specific sleep changes that both men and women go through as they age (see pp.97–101), there are similar issues for both sexes in their advancing years. In general, from around 35 to 40 years old (mid-life) to somewhere in the 80s, men and women see a decrease of around 30 minutes total sleep time for each decade that passes. This means that by the time we reach 90 years old, assuming we were getting eight hours in our younger years, we’re sleeping for only around six hours a night.

In older age, we experience increased awakenings and arousals, and maintaining any particular sleep stage becomes more difficult. Although the reasons why this should happen are not entirely clear, we do know that the biggest sleep thief is illness (both psychiatric and physical). Research indicates that conditions such as arthritis, diabetes, stroke and osteoporosis don’t contribute significantly to symptoms of insomnia, but obesity, bodily pain, depression, heart disease, lung disease and bladder problems do.

• Obesity contributes to waking up a lot during the night and waking in the morning feeling unrefreshed.

• Bodily pain, depression and heart disease inhibit our ability to fall asleep, and cause us to wake frequently during the night, wake too early and wake feeling unrefreshed.

• Lung disease may lead to feelings of tiredness in the morning.

• Memory problems are associated with difficulty in falling asleep and frequent wakings during the night.

• Nocturia (going to the loo several times during the night) and increased blood pressure and bladder urgency cause frequent nighttime wakings.

On the other hand, difficulty sleeping may itself cause some of these age-related ailments, and others. For example:

• Snoring may lead to obesity and pain.

• Cessation in breathing (sleep apnoea) may cause obesity, lung disease and depression.

• Restless legs may lead to pain, depression and stroke.

• Daytime sleepiness may result in obesity, pain, depression, lung disease and memory problems.

The effects of poor-quality sleep

Getting fewer hours sleep can become a serious problem among the older generation. The reduction in sleep time leads to impaired mood and fewer hours spent in physical activity. In turn, older people may spend less time socializing with others (exacerbating psychiatric problems) and will find that their airways can weaken through lack of exercise, which only makes worse any sleep-related breathing disorders (see pp.191–201).

Getting help

Many older people don’t report their sleep problems to their doctor, considering it a normal sign of ageing. I’ve also found that older people are more likely to self-medicate, using over-the-counter sleep aids, or an alcoholic nightcap. It probably goes without saying that I recommend neither of these. (In particular, bear in mind that if you take sleeping pills and suffer from nocturia, you’re at an increased chance of falling when you get up in the night to go to the loo.)

Instead, it’s important to work with your body, age and stage of life to optimize your sleeping hours. Keep to a regular schedule – get up at the same time each day, try to spend at least 30 minutes in physical activity (walking and doing the cleaning or gardening all count), and go out and get as much natural light as you can. Late afternoon and early evening are good times to be outdoors. The natural light then helps to keep your circadian rhythms in tune with real time, potentially easing symptoms of phase advance (the need to go to sleep early). Of course, avoid caffeine, alcohol and other stimulant drinks before bedtime. If you need to nap in the afternoon, take your nap as soon as you can after lunch and restrict it to 20 to 30 minutes in duration.

Try not to fall asleep in front of the TV during the evening and use the relaxation exercises in this book to help to prepare your body for sleep each night. Also, bear in mind that medications you may be taking for other ailments may affect your sleep. Sometimes a change of dosage or a shift in the time you take your medication can improve your sleep at night. However, never make any changes without discussing them first with your medical practitioner.

My elderly mother claims that she needs her “nana nap” every day, but then complains that she can’t sleep at night. Is the nap the problem?

Elderly people do seem to nap more, but why this should be the case is not clear. Of the minimal amount of research that we’ve conducted, severe sleep-related breathing disorders (see pp.191–201) appear to have the biggest impact on feelings of daytime sleepiness and therefore the need to nap. Whether or not the naps are good or bad remains the subject of much debate. On the good side, it seems they may help cardiovascular health, and improve daytime function, and may even improve nighttime sleep. In fact, evidence suggests that poor nighttime sleep in the elderly is more likely down to breathing disorders than to any daytime napping.

Be aware, though, that while it’s good for her to catch up on her sleep, napping may increase her chances of falling (owing to grogginess as she comes round) and of ischaemic heart disease, and it may indicate cognitive decline. Keep an eye on her – but certainly don’t prevent her from napping if she feels she needs it.

Finally, don’t simply assume that because you’re getting older, you have to accept feeling unrefreshed every day. Talk to your doctor if lack of nighttime sleep is affecting how you feel and what you can do. Ensure that you receive the help and support you need to get some good-quality sleep at any and every age.

SLEEPING BEAUTY, SLEEPING LION

Anyone who has ever shared a bed with a member of the opposite sex will undoubtedly know that the sleep of men and women don’t always coexist seamlessly. There are certain periods in a woman’s or a man’s life that particularly affect sleep. Menstruation, pregnancy and menopause can have a dramatic effect on a woman’s sleeping patterns; while the sleep of men is particularly affected by ageing.

The differences between the sleeping patterns of men and of women begin at infancy and are intrinsic to every cell in the male and female body. Male and female genes have different impact on breathing control, the way the biological clock responds to stress, the function of the hypothalamus (the region of the brain that links the nervous system to the endocrine system, which governs the body’s release of hormones) and even how cells grow and die.

Using an actigraph – a device that monitors gross motor movement and attaches to the wrist like a watch – to measure how much a subject moves around during sleep reveals that infant boys are likely to be poorer sleepers than infant girls. It also shows that, with age, girls seem to take longer to get to sleep, but once they’ve nodded off are more likely to sleep longer than boys. By adolescence, girls’ sleep is longer and more efficient than boys’. An EEG shows that, at birth, the oscillations of boys’ slow-wave (deep) sleep are particularly slow, but that by adulthood arguably women have “better” slow-wave sleep than men.

Women and sleep

In general, women get around 20 minutes more sleep than men in every 24-hour period. No one is certain why this would be, but some scientists at Loughborough University in the UK have hypothesized that in order to perform multiple, complex tasks simultaneously, women use more of their brains than men do, so they have increased need for consolidation time – and that means a greater need for sleep.

Objectively, girls and women sleep better and longer than men – subjectively, however, women are more likely to complain of insomnia. A study by the University of North Carolina has shown that women are more likely to rack up a sleep debt than men are. This finding is compounded by a study in Canada in which 35 per cent of women said they have trouble sleeping, compared with only 25 per cent of men. Women tend to be lighter sleepers, disturbed more easily during the night than men. For example, a woman is more likely to rouse at the mere whisper of her name or the gentle snuffles of her baby. A fidgety partner is more likely to bring her round from sleep completely. To make matters worse, a study at the University of Surrey, UK, has shown that once roused, women find it harder to get back to sleep.

Sleep and the menstrual cycle

Why is it that women are more likely to sleep badly? As with so much about sleep, we don’t yet have concrete answers. However, it’s likely that women worry more than men. They are also more emotional, finding it harder to switch off. But there could be physiological reasons, too. During the menstrual cycle, at the point at which the egg has been released from the ovarian follicle and the remnants of the follicle have released the hormone progesterone, a woman’s temperature might rise by up to 0.4°C (32.7°F). This slight increase can make a woman feel too hot in bed, making it harder to get to sleep or to stay asleep.

The menstrual cycle also disrupts a woman’s rhythms for releasing melatonin, thyroid-stimulating hormone and cortisol. Frustratingly, research is not clear as to the impact of these disruptions on major sleep characteristics (the amount of deep sleep, dreaming sleep and so on a woman has), but we do know that there are subtle effects at work. For example, at certain stages of the menstrual cycle, a woman has a greater abundance of sleep spindles in the upper frequencies, although we don’t actually know yet what this means for women in practical terms. On the whole, though, while women without other menstrual difficulties may complain of lighter sleep around the time of menstruation, the impact on sleep of the differing hormonal milieu appears to be minimal. If you suffer from premenstrual syndrome (PMS) or polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), however, you may have a different story to tell (see box, pages 106–107).

Of course, it’s not just the menstrual cycle that uniquely affects female sleep. Pregnancy and menopause are times when sleep patterns go through changes that are exceptional to any other time in a woman’s life.

Sleep and pregnancy

I’ve often heard mothers say that lack of sleep during pregnancy is the body’s way to prepare a woman for the first few sleep-deprived months of new parenthood. I don’t know if that’s true, but from a weak bladder to sleeping with a bump, there are many aspects of pregnancy that conspire to make restorative sleep much longed for.

Studies indicate that women who are having their first babies suffer greater sleep deprivation than those in their second or subsequent pregnancies. This suggests that apart from the physical reasons why a pregnant woman might have less good-quality sleep (which affects all women in pregnancy, regardless of how many babies they’ve had), there are psychological factors at work, too – such as anxiety about the baby or birth. In general, research suggests that pregnant women have less deep sleep, and less dreaming and more drowsy sleep than non-pregnant women. There’s some evidence to suggest that lack of sleep during pregnancy may lead to pre-term delivery or may increase your chances of suffering post-natal depression. For these reasons, and for your own ability to cope with the demands of pregnancy, it’s important to do everything you can to optimize your chances of sleeping well while you’re carrying a baby.

Pregnancy is divided into three “trimesters”. The first occurs from conception to three months, the second from four to six months and the third from seven months until birth. In a study of 300 pregnant women, the rate of nighttime awakenings increased by 63 per cent in the first trimester, 80 per cent in the second and 84 per cent in the third, suggesting that insomnia develops with the developing baby.

Sleep during the first trimester

From the moment of her baby’s conception, a woman’s body goes through innumerable hormonal changes aimed at ensuring she carries her baby to term. Some of these hormones increase the blood-flow through the body by up to a third, while increases in progesterone (up to 5,000 times pre-pregnancy levels) relax the smooth muscles of the bladder. This means that on the one hand more blood is being flushed through the kidneys, creating more waste (urine), and on the other, the bladder itself is “weaker”. Finally, a growing uterus within the pelvis in the first three months of pregnancy begins to put pressure on the bladder, which in turn increases how often the bladder feels full. The result is that both during the day and during the night, a woman in early pregnancy needs far more trips to the loo. At night, this can significantly disrupt a good night’s sleep.

The best way to try to minimize nighttime trips to the loo is to ensure that you get the majority of your fluids before 7pm in the evening. Avoid tea, coffee and alcohol in the evening altogether – you should in any case drink these to a minimum while you’re pregnant. All these drinks are diuretic, which means that they pass through your system quickly and increase the need to urinate.

Sleep during the second trimester

Between four and six months of pregnancy, hormone levels settle down and the uterus moves out of the pelvis to make space for the growing baby, temporarily relieving pressure on the bladder. This is probably the time in your pregnancy when you’re least likely to need the loo in the night. However, other things conspire to disrupt sleep.

PMS, PCOS AND SLEEP

Almost a quarter of all women suffer from premenstrual syndrome (PMS) – including period pain and mood disorders – and/or polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). These women are generally two to three times more likely to experience excessive sleepiness in the daytime and insomnia at night during their menstrual cycle.

If you have PMS

At night, you may find that you move around more, and are likely to wake up more frequently and suffer disturbing dreams. During the daytime, you may have increased fatigue and sleepiness and reduced concentration. Your parasympathetic nervous system, which regulates your bodily functions during sleep may stop working properly, reducing the restorative power of sleep. During sleep your pain threshold lowers, so if you suffer from dysmenorrhoea (period pain) at night, your cramps will feel particularly uncomfortable, waking you or keeping you awake.

Your best strategy is to manage the effects of PMS – and there are many wonderful books dedicated to this subject, which is too involved to do justice to here. In the case of period pain, though, I do recommend taking a painkiller such as ibuprofen or paracetamol (if they are not contraindicated) before you go to bed, as well as a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory, at least until you’ve managed your symptoms in other ways.

Polycystic ovary syndrome is caused by hormonal imbalance. It occurs when follicles on the surface of the ovaries fail to develop and wither away properly, causing cysts. It can contribute to chronic period pain and exacerbate all the symptoms of PMS. Independently, though, it’s been linked with increased sleep-related breathing disorders, such as sleep apnoea (see pp.191–201). Many women with PCOS are given the contraceptive pill to help regulate the hormone levels throughout their cycle and so reduce the condition’s effects, including its effects on sleep. However, bear in mind that this in itself can affect your sleep (see box, below). Women with PCOS are also prone to weight gain. If you develop a breathing disorder, bear in mind that losing weight (if appropriate) may help to ease the symptoms.

SLEEP CLINIC

Since I’ve begun taking the contraceptive pill I feel far less refreshed after sleeping. Is there a link?

Studies show that oral contraceptives reduce the amount of deep sleep women get and increase the amount of light sleep. They also increase body temperature throughout the menstrual cycle (and even for a while after you stop taking the Pill). Some research suggests that the oral contraceptive influences or inhibits the body’s melatonin secretion – but so far the results are inconclusive. In short, it is indeed likely that now you’re taking the Pill you’re experiencing some sleep problems. As an initial step, try keeping your bedroom a little cooler to see if you can counter the effects of your raised temperature. If you feel that your sleep is becoming significantly compromised, see your doctor and perhaps even consider alternative methods of contraception.

You may experience leg cramps, a blocked nose, and strange and vivid dreams. Note that a blocked nose (which may cause you to snore) can be a sign of increased blood pressure, so make sure you mention it to your doctor or midwife. Some studies claim that your sleeping position can affect the health of your baby. Avoid sleeping on your back after 16 weeks of pregnancy, as the weight of the baby can put pressure on your blood vessels, and sleep on your left side to increase the blood-flow through the baby. However, if you wake up and find yourself on your back or on your right side, don’t fret – simply turn over. If you’re worried that you’ll turn in your sleep, putting a pillow behind your back as you lie on your left can help you stay in position. Keep your knees pulled up toward your bump. If your hips begin to ache (which may be caused by the loosening of the ligaments around your pelvis), sleep with a pillow between your knees.

Stick to your sleep hygiene routine, including going to bed and getting up at the usual times. Give yourself the luxury of an afternoon nap if you need to – but keep it short (not more than 20 to 30 minutes) and make it early in the afternoon.

Sleep during the third trimester

More than half of all pregnant women claim that their sleep is worst of all during the third trimester of pregnancy.

I’m just past my first trimester and since I got pregnant I’ve been having extremely vivid dreams. Is this normal?

Yes, it’s completely normal! Your body is going through an intense period of change. You’re also acutely aware that your life is about turn on its head – or at least that’s what people tell you. Your dreams are an outlet for your anxieties. The journey to parenthood is one of the most exhilarating but also daunting you’re ever likely to face, so it’s to be expected that you try to unravel your feelings about it during your sleep. You’ll probably keep having vivid dreams right up until the point you have the baby – although their content might change. In the early days of pregnancy, many women dream about giving birth to baby animals, or have dreams that represent anxieties about their changing shape. In a Swiss study, 17 per cent of women in their second trimester reported an increase in erotic dreams. Some experts think that this is the woman’s way to reassure herself that she’s still attractive. Toward the end of the third trimester, dreams may focus on anxieties about childbirth or meeting the baby for the first time.

Keep a dream diary. Not only will this offer you an outlet for expressing your dreams and your emotions during your waking hours, it’s also a wonderful record to show to your baby when he or she is older. (You might want to leave out the erotica, though!)

As the baby grows bigger, your uterus expands further so that it again fills the space in your pelvis and puts pressure on your bladder. Unfortunately, therefore, the frequent nighttime trips to the loo may make a reappearance. Lean forward as you pee, which will help you to empty your bladder fully.

Your bump is also going to make it increasingly difficult for you to find a comfortable sleeping position. Stick to sleeping on your left side, with a pillow between your knees if it helps and one under your bump to help support it. If lying down is just completely uncomfortable, you may find it easier to sleep propped up in bed instead.

It’s common to experience heartburn at this time, too, as there’s little space in your stomach for food, while the high levels of progesterone relax the muscles of the oesophagus, making it easier for food to come back up. Avoid rich or spicy foods at the end of the day, which may anyway cause heartburn, and try to eat little and often rather than opting for one main meal in the evening. Again, sleeping propped up can help alleviate the heartburn.

More than a quarter of pregnant women in their third trimester may suffer restless leg syndrome (RLS) – the feeling that creepy crawlies are climbing your legs so that you feel a constant need to move your legs to relieve the sensation. This is particularly marked in women in their first pregnancy. Read my advice for overcoming this disorder on pages 201–3, but bear in mind that the condition is associated with low iron. Increasing your intake of folate-rich foods can help – lentils, beans, pulses and spinach are all good sources. Vitamin-C-rich foods will enable your body to absorb the folate more efficiently. Check with your doctor or midwife, but iron and folate supplements can help, too.

Finally, many women say that their baby seems to “wake up”, dancing around in the uterus, the moment they try to sleep. There’s debate as to whether or not it’s true that babies in the womb work on a nocturnal cycle, or whether it’s simply that when the mother is still, the baby’s movements are more noticeable. Even so, there’s very little you can do about this except to try to change your thinking patterns so that rather than becoming a source of irritation and sleeplessness, your baby’s movements feel reassuring to you that all is well.

Above all, remember that lack of sleep might feel dreadful for you but it doesn’t harm your baby in any way. Do your best to rest as much as you can during the day (although remember the note about napping, on page 101). You may find that relaxation techniques or classes (such as antenatal pilates or yoga) help to give you a pervading sense of calm, making sleep more likely. You can also try a bedtime relaxation, to put you in the mood for sleep, such as the Humming Bee Breath meditation on page 81.

Menopause and sleep

In the West, menopause typically occurs any time between the ages of 40 and 58 years old (on average at around 51 years old). The timing depends upon a variety of factors, including your ethnicity, how old you were when you had children, whether you breastfed and your weight. The signs of approaching menopause – at first irregular periods, then later, intermittent periods, hot flushes, loss of libido and mood swings among them – may be evident several years before a woman ceases to menstruate altogether. This lead time is called the “peri- menopause”.

There are very few objective studies on the effects of menopause, but those that have been conducted offer some insight into how the menopause, and its side effects, may inhibit good-quality sleep. One study noted that during the first half of the night, women with hot flushes had significantly more arousals and awakenings than a control group and those without hot flushes. Women who were convinced that their hot flushes were causing a problem with their sleep on average reported around five hot flushes per night, and five sleep disturbances. Interestingly, the awakenings occurred immediately before each hot flush. In trying to find a solution to the problem, the researchers found that a lower ambient temperature of 18°C (64.5°F), compared with 20°C and 23°C (68°F and 73.4°F), reduced the number of hot flushes in susceptible women by 25 per cent. I think 18°C is about the right room temperature (if such a generalization can be made) for sleep anyway (see pp.5–152), so you may need to go cooler than this to see an improvement in your symptoms.

Furthermore, oestrogen is believed to have an impact on the biological clock, making it harder to fall asleep or causing you to wake too early in the morning. However, we need much more research in this area to be able to make conclusive statements about the link between the two. Oestrogen is also thought to affect the size of your thermoneutral zone – the temperature zone in which sleep is comfortable and undisturbed. As women stop producing oestrogen with the onset of the menopause, so their tolerance of temperature diminishes. This means that your optimal sleeping temperature before you began entering the menopause may now seem stiflingly hot, exacerbating your susceptibility to hot flushes and night sweats. As there’s little you can do to increase your oestrogen levels again, try to eliminate or overcome any of the other things that reduce your tolerance to temperature. These include smoking, physical inactivity and being overweight.

Men and sleep

Men present something of an anomaly to sleep science. On the one hand, they’re less likely to report tiredness and disturbed sleep than women are; but on the other they show far more sleep abnormalities when their sleep is recorded at a sleep centre. Why would this be? Perhaps it’s simply that women are far more willing to share their problems (we know that in other areas of medicine women are more likely to tell you when they are, for example, depressed or anxious). Or is it something else?

Men more often suffer from obstructive sleep apnoea than women – which is probably why men are more often accused of snoring. Sleep apnoea is likely to cause increased daytime sleepiness, but also shortens the time it takes a sufferer to fall asleep. Even though the sleep disorder is pathological (the result of a physical defect), sufferers are likely to report that they “sleep like a log”, feeling that falling asleep comes easily to them and without making the association that daytime sleepiness might in fact be because their nighttime sleep is interrupted by momentary lapses in breathing.

In men it’s particularly noticeable that poor sleep causes problems with glucose control, which in turn is associated with the development of increased blood pressure – and therefore heart attack and stroke. The precise reasons why this happens are not clear, but the signs are that sleep disruption and restriction have direct effects on the body’s inflammatory mechanism – which conspires to cause thickening of the arteries and vascular disease. The physical effects are then compounded by the fact that feeling sleepy during the day inevitably means doing less exercise; while low glucose levels mean that men are more likely to seek out a sugar hit to give them a boost of energy. A diet high in refined sugar is linked with obesity, itself a cause of heart disease – and sleep apnoea. And so the cycle goes on.

Although it’s important that men who are overweight and suffer from sleep apnoea take steps to lose weight (see p.191–201), unfortunately this will not necessarily spell the end for their sleep-related breathing disorder. We think that this is because either long-term inflammation or damage to the neuromuscular control mechanisms of the neck prevents a return to normal breathing.

The most important thing you can do if you think you’re overly sleepy during the day – even if you think you sleep well at night – is to go through all the steps relating to good sleep hygiene (see Chapter 3) to ensure the quality of your sleep is as good as it can be. Go to bed relatively early, perhaps 30 minutes to an hour before you think you need to. If you wake feeling refreshed, and you don’t feel abnormally tired over the course of the day, you’re doing OK.

Finally, a word about testosterone levels when men get too few hours sleep. Testosterone is commonly thought of as the “male” hormone, playing a key role in the development of the gender-specific traits of a man – the growth of the testes and prostate, as well as physical strength and bone density. Women also have some testosterone, but at much lower levels. A study at the University of Chicago in 2011 revealed that lack of sleep dramatically reduces male levels of testosterone – which can further increase a man’s susceptibility to sleep-related breathing disorders and to obesity, not to mention its effects on erectile dysfunction and hypogonadism (when the gonads stop producing hormones properly).