Then sought the gods their assembly-seats,

The holy ones, and council held,

Whether the gods should tribute give,

Or to all alike should worship belong.

There may come a time in your journey when you feel the best way forward is starting your own spiritual community. This chapter provides some initial tools for building your own community. When it comes to community organizing you should always be open to adopting methods, ideas or practices proven to be effective by the experiences of others. One source that is especially helpful for this subject is Starhawk’s The Empowerment Manual: A Guide for Collaborative Groups. There are many more written by community organizers, activists, and others that might guide your community in its development.

The backbone of communal practice in Radical Norse Paganism is local groups known as fellowships. These in-person groups meet regularly, conduct their own rituals (public or private), hold study sessions, have social nights, and do whatever else the members like to do in the belief that it is part of their spiritual practice. Fellowships, at their best, are a blend of spiritual group and chosen family. They offer support, instruction, solace, and a place for Norse Pagans to practice their spirituality among like-minded people.

Sometimes groups of neighboring fellowships band together in alliances known as Things (pronounced tings), the name for the popular assemblies of the ancient Norse peoples. Things provide member-fellowships with more resources, support, and information than any individual fellowship could muster on their own. Things are not that common, but as more fellowships develop, the question of regional organization becomes more pressing, making them the best existing answer. This type of organization is inspired by the East Coast Thing event, which takes place yearly in the northeastern United States.

Fellowships and things are not the only kinds of community out there for Norse Pagans. In many places there are pan-Pagan groups where members come from different practices, traditions, and forms of Pagan spirituality. Some of these are regional alliances of many different Pagan groups. There are also online groups which in many ways work a lot like most other internet groups, with a Norse Pagan or generally Pagan focus. There are many Norse Pagans who are perfectly comfortable with these different arrangements. Several fellowships have been born from people who met through these groups, making them a viable option for many Norse Pagans looking to build community.

Forging Ties That Bind

The first thing your community should always do is set and maintain realistic goals. Always keep focused on what your community wants to do, must do, and can do. Nothing hurts a community more than trying to do too much, too fast, without enough people or resources to do it all. At the absolute minimum, your community should be holding as many regular rituals and social get-togethers for its members as it feels are necessary, communicating effectively, educating all current and potential members, and resolving conflicts equitably. Only worry about taking on more after these core functions are working smoothly and you have enough people to handle additional projects or services.

Your community should also include a very strong inclusivity and hospitality statement. These statements make it clear your group is genuinely inclusive in practice. Here is an example of an inclusivity statement which you are free to use in whole or in part for writing your own:

We are an inclusive community. We believe practicing this form of Norse Paganism is open to all individuals who feel it is valid, fulfilling, and speaks to them regardless of race, national origin, gender, sexuality, gender identity, physical or mental ability. We believe discrimination for any of those reasons is antithetical to the practice of Norse Paganism. We do not associate with, support, or agree with any groups or individuals who deny the right of others to practice Norse Paganism freely based on any of these grounds. Any individuals, groups, or organizations who believe those forms of discrimination are fundamental to practicing Norse Paganism are not welcome at any of our events, rites, or gatherings so long as they hold such beliefs.

Structure

The first real question, once you have your core group of people together, is how you are going to organize your fellowship. The obvious answer many groups tend to fall into is people take charge, lead by example, and delegate as needed. This sort of top-down, charismatic approach has a lot of drawbacks, namely that it puts most of the burden of organizing and community-building on the people at the top. Such groups also turn off many new members when they realize they’ll have little actual input. It also burns out the people in charge very quickly, greatly limiting the group’s effectiveness.

A better approach is what Starhawk calls collaborative organizing, which is different from a top-down or charismatic model because the group is organized as a circle of equals. Decisions are made collectively by all members. Another term for this approach is participatory democracy, a method of governance where community members take a direct role in setting policy, choosing who will implement it, and have the power to directly hold those endowed with such responsibility accountable. This model has been proven effective at every level, from small study groups and community organizations to cities like Porto Alegre, Brazil which has over a million inhabitants.177

As modern as this solution may sound, it has historical and spiritual foundations for Norse Pagans. The most famous example was the Icelandic Althing, where the people came together in a great assembly to make laws and settle disputes without kings. The sagas of the Heimskringla include several examples of similar assemblies in Norway and Sweden that had the power to make or break ruling kings. There’s one example from Sweden where a thing threatened to depose and kill a king because he tried to force the people to keep fighting an unpopular, unnecessary war. Even the gods, according to the Voluspo, created Midgard by deciding all things in council, and when Ragnarok comes they will gather to debate the best course of action one last time.178

All these ideas are soil for growing a healthy community. Starhawk recommends making this happen by bringing everyone involved together to discuss their priorities and preferred methods. Prospective community members should draw up a set of governing agreements laying out how often formal meetings happen, how many members need to be present for decisions made at a meeting to be legitimate, how decisions are made, channels of communication, dispute resolution, delegating responsibility, and the manner in which new people are brought in to the group. Governing rules should be broad, only subject to change through unanimous consensus or a supermajority of all members, and cover the core functions of the group. They should be written down, accessible to all members, and available to the public on request or posted in a visible place such as a website or social media page.179

When it comes to the question of making decisions, a highly effective model is a blend of majority vote and consensus. In this approach, decisions for most matters are resolved by a pre-determined majority, usually two thirds or three quarters of all members, while all members retain a special kind of vote known as a block. A block is where any member, or for larger organizations a group of members, declare they cannot support the current proposal as it stands and will leave the group if it passes without addressing their concerns. If there is a block, the proposal cannot be implemented as written until the concern is resolved or, if it cannot be resolved through genuine good faith efforts, the blockers leave the group. This method ensures that serious objections are addressed while guaranteeing decisions are made in a timely fashion, combining the best of majority vote and consensus decision-making systems.

The final structural question is what standards people need to meet to join your community. Even the most well-intentioned and informed person still needs time to learn how a community works, its norms and expectations. This is why education is critical for all healthy communities. Prospective members should be mentored by an existing member in how the community works, regularly attend community events for a set period such as between six months and a year, and participate regularly in study groups. Only after prospective members have done all of this is when community members should discuss and vote on if they should become a member in good standing, giving them a vote on community affairs, and be delegated responsibilities.

Running Meetings

Having agreed on processes is only the first step for organizing community. It is also important to learn the skills of facilitating meetings and discussions so that things run smoothly. The first part of this process is ensuring meeting dates, times, and locations are posted to agreed-on communication channels well in advance of the meeting, preferably a week at the minimum for a non-emergency meeting, and all meetings start on time.

The first item on any meeting’s agenda is nominating a lawspeaker to facilitate the meeting, a note-taker, a time-keeper, and someone to keep track of who is speaking next, who is also known as a stack-taker. All these positions should be approved by consensus. The lawspeaker then either reads off the meeting’s agenda, if it was already agreed on at a previous meeting or worked out through approved communication channels, or facilitates the necessary discussions for setting one. They should include time for any items people add to the agenda.

The job of the lawspeaker as facilitator is ensuring all voices are heard and given a fair hearing. Lawspeakers abstain from voting and offering their opinions on whatever is being discussed, sacrificing their voice in service of ensuring all voices are heard. What they can do to achieve this is ask clarifying questions when needed, summarize existing proposals including any amendments offered by members, supervise votes, administer oaths, and keep everything moving smoothly according to agreed on processes. Facilitation is a big responsibility and is necessary for effective meetings.

The stack-taker tracks who is up next to speak and gives priority to those who speak the least often. People should indicate their desire to speak by quietly raising their hands. A time-keeper watches the clock. If the group has agreed that each person should only have a set amount of time to speak when it is their turn (two minutes is a common choice), they keep track of each speaker’s time. The note-taker’s job is to keep simple notes of the agenda, who ran the meeting, what was discussed, and what decisions were made and ensures the final meeting notes are distributed to all members. If you want more information, Seeds for Change has an excellent guide on running meetings.180

Delegation

There are always specific jobs that need to be carried out on behalf of the community. The best way to handle this is delegation. When a community decides a specific job or set of tasks need to happen they choose people, either an individual or if necessary a team known as a working group, who are delegated the necessary authority for carrying out the day-to-day work and making necessary on-the-spot decisions. One example of delegation is choosing a team to manage an upcoming ritual.

Transparency and accountability are essential for delegation to work. Anyone that is delegated power by their community, whether an individual or group, must make regular reports on what they’ve done and the outcomes of their actions to their community. The community always has the power to limit or change what delegates can do through direct vote. If the community feels the people in positions of responsibility have abused the community’s trust they may remove that power through a vote of no-confidence. Communities must always have the power to collectively revoke delegated power for any reason they feel is justified at any time.

Anyone seeking to hold such a delegated position must remember the core of these duties is to serve, not rule. The power you are endowed with is not yours. It has been lent to you and decisions you make while holding it impact the whole community. Starhawk says, “An empowering leader rarely uses Command mode. Most of the time, she leads by example and persuasion.” She further says delegates should always work to empower others, pass on their skills, and prepare successors both to grow the community’s knowledge and take care of their own needs while also recognizing, “All of this is, of course, the ideal. We can strive for it, but most of us will fall short in one way or another. An empowering leader makes mistakes.”181

Communication

Having a consistent, reliable channel for internal communications is essential for maintaining a healthy community. There are several different ways this can be done, ranging from something as simple as a phone tree and text message groups to online forums, chat servers like IRC or Discord, email lists, and social media groups. Regardless of the medium your community uses, it is essential that it is clear what channel is used for announcing events, meetings, and distributing notes, and that the method used is consistent, reliable, and secure.

When setting up your communications network, it is important for your community to establish clear ground rules, clearly state expectations, and explicitly state what is appropriate to post. This is important because having clear expectations for how people should treat each other on internal communication channels encourages productive conversation and helps people feel welcome. Communication channels that do not have rules on what is relevant or appropriate behavior tend to end up jammed with just about everything imaginable, making them useless for actual organizing. You will need to delegate people either individually or as a working group to enforce these expectations.

Privacy and security are especially important for these channels. Spirituality is a very sensitive, personal subject for many people, so having a secure, private space encourages people to open up and participate. It also helps discussion stay on topic by keeping out disruptive and actively malicious people. Private, secure channels for official internal communications also give people the space to freely discuss community matters in a productive fashion. Many effective organizations have handled day-to-day problems by effectively cultivating a readily available communications network that is accessible to all members.

Along with the mechanics of setting up communications, it is important people feel free to speak up. The flipside is being open to what they want from community. Act with empathy toward all in your community as best as possible, genuinely listen to others, and engage with what they say. Collaborative groups thrive when everyone is given space to speak, be heard, and discuss in good faith.

Conflict Resolution

All groups and communities will inevitably experience conflict of some kind or another. After all, communities are made up of people who each have their own thoughts, goals, feelings, perspectives, and biases. What is presented in this section is mostly an introduction to some ideas and techniques. For a more complete understanding, it is highly recommended you read The Empowerment Manual, which goes into much greater depth on conflict resolution. Starhawk’s work is the main guide for this section.

Starhawk argues there are two ways a community could view conflict. The first is where everything is an all-or-nothing, “right must prevail” sort of model ending in absolute victory—and lots of burned-out people. The second is where tensions and conflicts draw attention to existing problems, providing a community with the opportunity to learn, improve itself, and emerge stronger from the experience. As tempting as it may be to always fight and be right, the more sustainable path—especially in building a spiritual practice—is one of growth from tension rather than smothering or silencing it.182

Bruce Tuckman, an influential psychologist, has done much work on group dynamics, noting that there are four stages of group development: forming, storming, norming, and performing, All are useful in understanding different sorts of conflicts and why they pop up. According to Tuckman, conflict of a sort is pretty much inevitable during the first three stages. During the forming stage, people are sorting out goals, systems, and getting to trust each other, leading to clashes based on different perspectives. The storming stage, unsurprisingly, is where it can get most intense as differing views and solutions clash. Norming, when the overall direction sorted out in the previous stages is being refined, is about smoothing things out, though some conflicts can still emerge.183

Growing through and from conflict depends on developing effective means for resolving it as equitably and amicably as possible. The key, according to Starhawk, is remembering that “… conflicts are often Good vs Good, and framing them in that way can help us resolve them creatively.” This, she argues, is because, “We are acculterated to view conflict as Good vs. Evil.” Another factor may be miscommunication, leading to misunderstandings and confusion.184

The best way to resolve such conflicts is offering mediation. There are many books (including Starhawk’s) with excellent information on the details and skills needed to be an effective mediator. What matters is that all parties feel they are being heard, the mediator is genuinely fair-minded, seen as such by all involved, and shouldn’t be involved in the conflict or have a strong opinion either way beyond a desire to resolve the problem amicably. Mediation also has existing precedent from the ancient Norse peoples. For them the goal for resolving any dispute is to reach the most equitable arrangement possible and only call for punishment if one person had clearly done injury to another.

Any agreements that come from mediation should be mutual for all people involved and the mediator should follow up with them after the fact. If the problem is one that involves the broader community, such as one involving the actions of a person with delegated responsibility, any settlement should be voted on by the community. Offers or requests for weregild should also be considered during mediation and terms of any weregild should be clearly agreed on before the end of a mediation session if it is requested.

There are, however, some cases where one side of an argument is genuinely in the wrong. These are shown by the person or people involved consistently acting in ways causing people to feel devalued, disrespected, or unsafe. The best thing to do is remove them from the community. Such situations put the safety and hospitality of the community at risk. In these cases, it may be best to limit the harmful person’s responsibilities, suspend them from group activities, or even remove them from the community entirely. This is both the best practical solution in such cases and is directly derived from the Norse practice of exiling repeat, dangerous, or otherwise totally irredeemable people, effectively exiling from the community and the protection of its laws.

If an exile ever tries to return, they must demonstrate that they have genuinely changed their behavior. Any decision to make them members in good standing should take much longer than normal to give them time to prove they’ve turned over a new leaf. Such a decision must be discussed with the community, with extra weight given to the voices of the people most affected by the exile’s actions. In cases where the autonomy of the people harmed and ensuring genuine hospitality is always more important than the exile’s desire to associate with a specific community. Requiring weregild from an exile as a precondition for returning to the fold is entirely appropriate and encouraged.

In cases where people are serial sexual harassers or assaulters, active bigots, physically violent, or consistently act in bad faith the best—and often only—solution is permanent exile. Just as there are times when no amount of weregild can make up for harm done, there are actions that cannot be forgiven and risks that should never be taken. The safety of your community is always more important than one person’s desire for redemption or acceptance.

Education

Education is essential for building any functional, sustainable community. It consists of two equally important components. The first is teaching people spiritual practices, the lore and the ideas behind modern Paganism. The second is instructing people in the norms, practices, expectations, and decision-making processes of their community. Regardless of what you are teaching, the basics of effective instruction remain the same. Anyone who wants to teach others should first study educational theory and work with skilled teachers before doing so themselves.

Conventionally speaking there are three main styles of learning known as auditory, visual and kinesthetic. Auditory learners absorb information best through listening to what others say, lecture, tone of voice, discussion, and talking things through. Visual students learn best from observing the material and work best with diagrams, charts, videos, and hand-outs. Kinesthetic learners understand material by direct interaction with the subject, preferring hands-on exercises, physical activities and demonstrations to reading or lecture. Most students tend to favor one of these methods all tend to use a combination of all these methods. Teachers should use a variety of instructional techniques to engage all students as fully as possible and adapt to what works best for the subject being taught.185

These frameworks are just the beginning. All effective teachers must also learn and practice several necessary behaviors. Teachers must show patience and compassion for difficulties faced by students in understanding material. New concepts are not easy to understand, and those steeped in the practice can easily forget struggles of the past in understanding things you now take for granted. Even so, don’t be afraid to push students a bit with clearly communicated expectations and goals. This may sound contradictory, but both elements must be kept in balance, shifting between one and the other as needed.186

When teaching, use as much ordinary, everyday language as you can; avoid jargon and technical terms when describing concepts or ideas. When used poorly and often, jargon tends to intimidate students—it reinforces their ignorance instead of inspiring their desire to learn. Excessive use of jargon locks people out of conversations, creates resentment, and fosters elitism. If you must use a specific technical term, make sure you clearly define it, use it as little as possible, and ensure everyone understands what it means. This doesn’t mean you should water down the content. What is key is realizing people will better understand what you are teaching if you present the material in terms and frameworks that are easy to follow.187 When planning study sessions, always use the most credible, proven, and qualified sources possible. Using credible sources helps build the students’ trust in the teachers, spreads solid information, and builds everyone’s understanding by giving them the tools to continue their own study. It also helps show students how to evaluate the credibility, knowledge, and usefulness of sources and think critically. Teachers should continually improve their own knowledge so they can better serve current and future students.188

These practices are effective in the immediate study space, but education does not start and stop there. Your goal, as a teacher, is empowering your students to learn and grow on their own. As a teacher, you should provide materials for students to conduct self-directed learning outside of study sessions. Doing so provides learners with the means for continuing the process on their own, inspires them to pursue independent study, and enriches their practice.189

Required Subjects

There are three topics every group should cover: spiritual education, community education, and inclusivity education. Each has its own quirks, challenges, and importance. The teaching techniques discussed earlier are all effective tools for educating people in each of these subjects.

Essential for building any Pagan group, spiritual education covers teaching the lore of Norse Pagan practice, providing the tools for developing personal practice, training in the sacred roles, conducting group ritual, and training in the mystic arts of Norse Paganism (like sei∂r and runelore) for any who are interested. Spiritual education depends on providing opportunities for direct, practical experience and working models for building individual students’ understanding. Everything from hands-on workshops to free-flowing discussion are highly effective for this topic.

Community education goes hand-in-hand with spiritual education: where spiritual work focuses on developing a deeper understanding of Norse Pagan practice, community education helps people understand how their new community works. The goal is teaching people how to be fully autonomous, active members of community. Fully educated community members better know how to contribute, develop proposals and implement them, and enhance the experience for all participants. Community education includes everything from teaching expected norms to having newer members sit in on community decision-making and dispute resolution processes.

Inclusivity education is for helping people understand how to treat each other, particularly people from groups who suffer from discrimination and marginalization in society, with dignity and respect. Inclusivity education is best done explicitly and implicitly. Explicit inclusivity education is where you teach people how to build a genuinely inclusive community, understand concepts like privilege, and truly respect all other people in the community. Implicit inclusivity education is weaving respectful conduct into all other aspects of your community, showing people how to be inclusive by positive example.

Inclusivity education requires great patience and understanding. Always remember people sometimes make mistakes while acting in good faith. When asked for further reading or research, always recommend specific works instead of telling them vaguely to seek out information for themselves. Always remember that it is never the responsibility of a person from a marginalized group to handle another person’s education, especially since people from those groups have often experienced serious trauma, including physical assault or fundamental violations of their autonomy. It is, however, always the responsibility of the community to ensure everyone receives effective inclusivity education.

Study Groups and Apprenticeships

There are two formats you should use for educating members of your community. These are study groups and apprenticeships. Study groups are good for providing necessary information to groups of people on spirituality, community, and inclusivity. Apprenticeships are best used by those who hold sacred roles or support roles to train others in necessary skills, teach the mystic arts, and provide in-depth instruction on topics previously covered in study groups.

Organizing a study group is easier than it seems but it does take work to run a successful one. The first step is working out potential study group members’ availability, use that to arrange a regular time, place, and day based on what works best for everyone, and agree on a regular system for communicating information related to the study group. Next, determine the major elements, themes and topics that need to be covered in the study group. Assign a session to each of these elements and provide all study group participants with the complete schedule. Prepare a consistent agenda for each session outlining it, what preparations participants need to do prior to each session, and send it to all participants at least a few days before the session will take place. Always organize the segments of your sessions based on the ten-minute rule.190

During study sessions it is important you do your best to get everyone involved. A good way to make this easier is starting your first session with an icebreaking activity like a round of introductions or a name game. This helps get people comfortable with each other. If there are people who speak less frequently, try calling on them or asking for their opinions before asking for input from people who speak more frequently. If they are consistently not speaking up in study sessions, set aside time outside of sessions to find out why and work out solutions to help them feel more welcome. The same is true of people who speak so often it becomes disruptive or is discouraging other people from participating. The University of British Columbia has an excellent guide on organizing study groups at https://science.ubc.ca/students/blog/study-groups.

The dynamics of apprenticeships are very different. Unlike study groups, apprenticeships are a one-on-one relationship between teacher and apprentice. These relationships encourage more personalized, specific instruction and feedback for both parties. Instruction sessions should always be one-on-one meetings between teacher and apprentice even if the teacher has taken on multiple apprentices. The goal of an apprenticeship is raising the apprentice’s skill to a level where they can do the work of the role they’re training for on their own, expand their understanding of the skills they’ve studied, and, if they are so inclined, train their own apprentices when they are ready to.

Before initiating an apprenticeship, the apprentice and teacher should have a serious discussion of what both are expecting, if the teacher has the skills for meeting the apprentice’s desires, if the apprentice has enough of a grasp of the subject to do more advanced work, and if both feel they are a good fit for each other. Once this has been worked out, both parties should write up a formal contract. This contract must be sealed with an oath sworn by both parties and witnessed by at least two other members in good standing of their community. This contract should outline expectations, obligations, an opt-out clause for both parties, define acceptable conduct, including prohibiting the teacher and apprentice from entering a romantic or sexual relationship with each other during the period of instruction, and any other concerns that need to be spelled out. Both parties and the witnesses must receive a copy of the written contract.

An apprenticeship is a long-term, ongoing relationship. On average, apprenticeships for skilled trades take at least a year with some lasting as long as six. Apprenticeship in Norse Paganism should be treated similarly by teachers; a year-long process is the norm. Quick results are not the point—the goal of apprenticeship is to train people to a level where they can apply their skills effectively and independently of their teacher. Teachers should exercise patience with their apprentices based on the understanding that such training takes time and hands-on experience.191

Outreach

Once your group has finished working out the decision-making structure, have clear communication systems, transparent conflict resolution, and effective education, reaching out to the general public is the next logical step. Outreach is a lot of work but is well worth the effort when done right. The challenge is clearly communicating what your group is about and handling many different factors beyond your community’s control. It is important to learn from your mistakes and the experiences of others when developing your outreach methods.

Outreach begins with being present. It means making an effort regarding the work of the hospitality team at public events to attending pan-Pagan networking events, festivals, and Interfaith events. It means genuinely listening to people, engaging with them, and showing compassion where appropriate. It also means being the best person and representation of Radical Norse Paganism that you can be. What you do, rightly or wrongly, in such situations reflects on your community, including anywhere on the internet. Always remember this when engaging in outreach and if you hold a known position of responsibility.

A very common outreach activity by Pagans is holding a pub moot. This is where your group hosts a public social night at a popular pub, café, club, or other similar and easily accessible venue. If your pub moot is happening at a popular location, make sure to book space in advance. Pub moots are a great way to encourage people to come out, meet others, and relax. The best pub moots are usually unstructured, starting off with a round of introductions and some sort of icebreaker conversation before letting things develop organically.

The next step for outreach is creating your own publicly available media. This used to be a difficult, expensive process, with everything from flyers and zines to posters and building up word of mouth as the tools of the trade. The internet and social media have made this quite easy in terms of cost and materials, and tools like social media and websites make it much easier to reach the public. In the present day the best places to start are on social media with Twitter, Facebook fan pages, Instagram, and independent networks like Mastodon.

Most of the content posted from your social media outlets should be official announcements, links to useful information including blogs produced by your group or its members, any relevant videos or photos, and promotional materials like memes. Make sure you post regularly, ideally at least once a day, so followers will have always have new material. Crosspost the same materials across multiple platforms, like posting pictures of your fellowship doing an outdoor ritual to the Facebook fan page, Twitter, and Instagram, as such cross-posting helps build visibility and promote consistency in messaging.

If your community has the expertise and resources to run one, a website is the next logical step forward for your outreach strategy. Whether they are free blogs hosted on sites like Wordpress or independently owned by your community, official websites provide the public with a readily available source of information and a consistent place for posting all material. If your community has a website and a blog, always post any new updates to your social media outlets. Your site should also have your community’s governing agreements and contact information. Websites are not totally necessary, but they can be a major boost for your community’s outreach and media presence if you have the means to support one.

One problem your community’s media outlets will likely face are trolls. These trolls aren’t the ones discussed in chapter two, though they’re very similar in some ways. For those who are unfamiliar, trolls are people on the internet who either enjoy riling other people up or actively driving people away from a specific page or site. They do this by harassing their targeted social media and site by posting offensive material, making false claims, insults, and worse in the comments sections or on the site directly. Trolls aren’t really interested in genuine debates or discussion; earnest engagement with them is pointless.

The best thing to do with trolls—whether they’re out to cause trouble for their own amusement or because they are actively hostile—is ban them and delete their posts. Moderation of this kind can be time consuming, but it is always better to smash the trolls than waste time or energy debating them. To paraphrase a popular internet meme, trying to argue with trolls is like playing chess with a pigeon: no matter how good you are, they’re just going crap on the board and strut around like they won anyway.

Essential to your media strategy is the art of messaging. There are many books, blogs, and podcasts on the topic that describe what works best. The foundation of it is understanding the power of story. Storytelling and narrative are without a doubt the oldest form of human communication. Everything we talk about, no matter how it reaches us, is put in the form of a story, whether chatting about what happened at the shop down the street or discussing advanced quantum mechanics. Messaging is thus the art of telling the best, most concise, consistent, and persuasive story.192

In all cases, the foundation of messaging must be the truth. Honesty and authenticity have greater power than spin, deception or lying either actively or by omission. Another key part of narrative is actively affirming your vision. Talk up the positives of your ideas and activities while avoiding negatives as much as possible to help keep people focused on what you are talking about instead of what you are opposed to. “We don’t” statements implicitly encourage people to think about the bad thing; instead you should say something like, “Here is what we do and support; it is different from the bad thing you are talking about, and here is why what we do is important to us while also being different from/opposed to the bad thing.” Always keep messaging simple, consistent with your values, and to the point, whether it’s a blog describing practices, an event announcement, or a public statement.

All media strategy and uses must be a community decision. This should include delegating the responsibility of managing your community’s publicly visible media outlets to a specific individual or working group. These delegates are responsible for executing the specifics of media strategy, reporting on the results to the broader community, and providing suggestions for consideration. Your messaging framework, guidelines for content, and the exact words of any official statements should always be determined by the community and not the media delegates. Their job, like all delegates, is to carry out the will of the community and not to make such decisions for them.

Dealing with the press—including television, radio, and newspapers as well as independent news and community blogs—is different from handling your own media. The most important thing to remember is that all press, no matter who writes for them or what their audience is, has bias in some way or another. Most are passively biased toward getting as many hits, views, and papers sold as possible, so it’s common for articles to play up spectacle, outrage, and controversy at the expense of truth. Others are actively biased, promoting a specific view or perspective to the point that they will obscure or leave out critical facts to make it happen.

The best way to deal with media bias is to have your community decide what your key message is before a possible interaction with the press, whether they show up to an event you are participating in or ask for an interview or comment on a recent event. The key message should be simple and delivered with a single, consistent point. Make sure everyone knows and agrees on the message for the press. Anyone interacting with the press should take every opportunity possible to reinforce the point. That way, no matter how much a press outlet may distort what is said, that point will get through one way or the other.

Once you have decided on your message, decide who is the most effective in delivering it. From there, the designated representatives should be the only people actively interacting with the press to both prevent confusion and keep the message consistent. Press representatives need to stay focused on the message, avoid going off on tangents, and be calm throughout any press interaction. Anyone who is not a designated press representative should deliver the same, collectively approved points. If you are not a press representative and are asked for further comment or clarification, you should direct the press to ask the designated press representatives for more information.

Group Ritual

Communal practice builds on the foundation laid by personal practice. The same tools used for developing effective personal practice are the core of effective group practice. That said, there are key differences, dynamics, and elements that are unique to group ritual that come from getting groups of people to work together in a cooperative fashion. Reaching ecstatic states and facilitating meaningful spiritual experiences in a group environment involves different challenges than solitary practice faces. Even so, the methods used in your personal practice, like meditation, creating sacred space, and using dance or music, are relatively easy to adapt to communal practice. When in doubt, above all else, keep things as simple as possible. Effective group ritual should be engaging and transformative for all participants.

The Ritual Team

Every group ritual needs a team to run it. The ritual team is made up of all the people with specific ritual functions and tasks. This includes specific and sacred roles as well as necessary support positions. Regardless of what position you have in the ritual team, everyone needs to put in work before, during, and after. No one is too important to avoid getting their hands dirty, whether it means washing dishes, unloading a truck, or setting up equipment. Being in the ritual team means doing what you must to create a meaningful spiritual experience for all participants, which means taking part in all elements of making sure this happens whether they are glamorous or mundane.

Sacred Roles

In this form of Norse Paganism are three specific roles necessary for group rituals: Goðar, V lur, and Skald. All are equal partners, fulfilling specialized duties that support each other and the ritual participants. If you want to take on any of these roles, you should seek training in the work and tasks associated with a role. There is nothing wrong with seeking guidance from teachers outside of this practice, or even Norse Paganism, so long as their ethics are in line with yours. Anyone in service to others should always aspire to be the best they possibly can be, doing whatever they can to improve their skills.

lur, and Skald. All are equal partners, fulfilling specialized duties that support each other and the ritual participants. If you want to take on any of these roles, you should seek training in the work and tasks associated with a role. There is nothing wrong with seeking guidance from teachers outside of this practice, or even Norse Paganism, so long as their ethics are in line with yours. Anyone in service to others should always aspire to be the best they possibly can be, doing whatever they can to improve their skills.

All sacred roles are positions of service to community before anything else. Taking up a sacred role includes the responsibility of acting as a facilitator for creating the best experience possible for all ritual participants and practitioners. Anyone who abuses their positions by engaging in gate-keeping, refusing to share critical knowledge, placing themselves between participants and the Powers, or using their sacred roles to exert power over others is unfit to hold their position. Anyone performing a sacred role is a guide for other practitioners, not a ruler or the sole interpreter of the will of the Powers.

Goðar

Goðar (pronounced GO-thar) are responsible for running rituals. Male Goðar are referred to as Goði (pronounced GO-thee), female Goðar are gyðja (pronounced GI-thee-ya) and they are referred to as Goðar when discussing more than one or referring to a person who does not identify as masculine or feminine. They guide the flow of a group ritual, facilitate group offerings in blot, and do all work necessary to organize and carry out rituals. There might be multiple people in an active community who take on this role. Some communities rotate performing the role between trained and willing members.

Goðar are like priests and priestesses in other Pagan practices. Along with running rituals goðar provide counseling, support, and care for any ritual participants in need. They also keep an eye on the overall situation to ensure people are safe, engaged, and having their needs met. In Radical Norse Paganism, group rituals, the goðar invoke and thank the gods.

Historically, the role comes from Iceland. Before the island converted to Christianity, it was divided into several groups who elected a goðar to hold sacrifices and enforce the law. These individuals were the chosen representatives of the people who oversaw communal events and were responsible for hosting them.193

V lur

lur

V lur (pronounced VO-lur) specialize in the mystical aspects of ritual. A male v

lur (pronounced VO-lur) specialize in the mystical aspects of ritual. A male v lur is referred to as a vitki (pronounced VEET-kee), a female V

lur is referred to as a vitki (pronounced VEET-kee), a female V lur is referred to as a v

lur is referred to as a v lva (pronounced VOL-va), and the word v

lva (pronounced VOL-va), and the word v lur is used to refer to more than one or to a person who does not identify as masculine or feminine. People in this role study the mystic arts of modern Norse practice; they use those arts to develop their understanding of the Powers and reach ecstatic states both individually and in groups.

lur is used to refer to more than one or to a person who does not identify as masculine or feminine. People in this role study the mystic arts of modern Norse practice; they use those arts to develop their understanding of the Powers and reach ecstatic states both individually and in groups.

Outside of ritual, v lur study the arts of seiðr and runelore, commune with the Powers, and explore deeper mysteries. They share this knowledge with their community and show others how to achieve such insights, making sure such practices are passed on. In Radical Norse Paganism group rituals, the v

lur study the arts of seiðr and runelore, commune with the Powers, and explore deeper mysteries. They share this knowledge with their community and show others how to achieve such insights, making sure such practices are passed on. In Radical Norse Paganism group rituals, the v lur invoke and thank the spirits.

lur invoke and thank the spirits.

In the ancient world, v lur lived in a respected yet outside status. As the bridges between worlds, they stood at the crossroads of reality. They were respected and sometimes a little feared for their abilities, but always valued. They were often assisted by v

lur lived in a respected yet outside status. As the bridges between worlds, they stood at the crossroads of reality. They were respected and sometimes a little feared for their abilities, but always valued. They were often assisted by v lur in training. These assistants helped regulate ecstatic states, watched for potentially hostile influences or energetic shifts and guided v

lur in training. These assistants helped regulate ecstatic states, watched for potentially hostile influences or energetic shifts and guided v lur back from deep seiðr work. One of the most well-known tools of a v

lur back from deep seiðr work. One of the most well-known tools of a v lur was their staff; many v

lur was their staff; many v lur used it as a tool for anchoring themselves during deep trance states and directing their energies.194

lur used it as a tool for anchoring themselves during deep trance states and directing their energies.194

Skald

Skalds are the keepers of lore, story, and song for ritual and their community. All skalds are referred to as a skald, when discussing them individually, or skalds when discussing more than one. During rituals they tell tales, share knowledge, and inspire participants with stories meant for the moment and ceremony. The skald’s job is to use tales of the gods, the ancestors, history, more current events, or even of their own making to teach, offer insights, and inspire action.

Outside of ritual skalds are artists, performers, and scholars. What makes a skald distinct from other performers is their tales, songs, and performances are rooted in a deep understanding of the lore and its significance in the modern world. In Radical Norse Paganism group rituals, the skalds invoke and thank the dead.

In the ancient world, skalds held a critical role: as the tellers of stories and singers of songs, they were the primary means for passing on information between and within communities. People with good fame were hailed and celebrated by the skalds, while doers of ill-deeds were condemned. This role of giving praise and shame was central to the skald and their duty to community. The best skalds carry the wisdom of history and deliver it in engaging ways so all may learn from the experiences of others.195

Supporting Roles

Supporting roles are just as critical to group ritual as the sacred roles. Support roles handle the logistical challenges in planning and executing a group ritual. What supporting roles are necessary depends on the specific ritual and what is involved. These could include kitchen volunteers who make sure food prep happens and dishes are cleaned, equipment specialists like audio-visual technicians, and, in some cases, people to handle physical security. For larger rituals, support roles are organized into designated teams based on the specific function each support role covers. Supporting roles are just as vital for making communal ritual possible as the sacred roles, and people fulfilling these duties must always be honored for their work.

One thing every group ritual must have is hospitality. Whether it is handled by an individual or a team of volunteers, the person in charge of hospitality is responsible for making sure all participants feel welcome, know what is going to happen, and offer instructions for how they can directly participate. Anyone engaging in hospitality support should make sure every person entering the ritual space is greeted and all questions or concerns are answered before the ritual begins. Hospitality people are also responsible for dealing with—and if necessary, removing—participants who are too disruptive or are making others present feel unwelcome or unsafe.

Types of Group Ritual

The best way to categorize group rituals is by the ritual’s size and purpose, mostly because there are different factors to consider based on how many people are involved. Purpose is also critical, as it helps shape what needs to happen in the ritual as well as its size. Based on size, rituals can be defined as private, public, and mass rituals. Purpose is much broader and covers everything from devotional rituals to holiday rituals, weddings, funerals, coming-of-age rituals, and naming ceremonies for children.

A private ritual is usually smaller in scale, as such rituals are invite-only. Sometimes they can be much larger, but this is uncommon. Planning private rituals can be easier and more specific than other rituals because the number of attendees is determined in advance. Likewise, the dedicated ritual team can be smaller, and it is easier to give specific tasks to participants.

Public rituals are open and advertised to the public. As such, they usually take place in public places, and the group organizing it is understood to be representing the practice to the public. Public rituals require larger ritual teams, as they must handle all the necessary preparations such as welcoming in new people, handling any media who may be present, and, in some cases, outside groups. Usually, ritual teams for public rituals have more than one person handling each of the sacred roles, with other volunteers handling other functions.

Though they share several of the same challenges and needs as public rituals, mass rituals are a category of their own. A good rule of thumb for determining whether your event is a mass ritual is if you are expecting at least thirty participants (not including the ritual team) to attend. The challenges of handling so many people require different planning from smaller public rituals. Ritual teams need to be much larger, have people assigned to handling more functional duties outside of the three sacred roles, and ritual activities need to be planned based on mass participation and finding ways to involve much larger groups than usual.

Guided Trance

One skill that is necessary for group ecstatic practice is guiding others through a trance state. The basics in chapter four provide a solid foundation for reaching a simple ecstatic state. Guided trance builds on this earlier foundation. In guided trance, the v lur takes on the role of guide for the rest of the group. They should also be supported by an assistant, known as a warder, who focuses on seeing how people are doing or reacting to the trance. Warding is often assigned to apprentice v

lur takes on the role of guide for the rest of the group. They should also be supported by an assistant, known as a warder, who focuses on seeing how people are doing or reacting to the trance. Warding is often assigned to apprentice v lur and anyone else undergoing such training, but can also be done by anyone with sufficient experience in trance and ecstatic work. Larger group trances often have several warders.

lur and anyone else undergoing such training, but can also be done by anyone with sufficient experience in trance and ecstatic work. Larger group trances often have several warders.

The trance guide, along with any warders, must remain out of a trance state while feeling the vibe in the room and how people are responding to ecstatic triggers. Effective guides operate with one foot in each world, leading from a place of understanding what the trance participants are experiencing. Doing so takes discipline and practice; if you are interested in working as a trance guide, you should study the deeper trance methods of seiðr before practicing this halfway state. Accordingly, warding is usually assigned to v lur in training as it helps introduce them to this state.

lur in training as it helps introduce them to this state.

The next skill for guided trance is clear descriptions. Trance is a state where the mind is open to many different possibilities, which makes participants somewhat suggestible and open to many pathways. Vague descriptions may confuse people, lead to inconsistent experiences, or invite unexpected results. Using simpler meditations when you are first starting out, such as the exercises in this book, is a good way to practice these skills. Once you are comfortable with these meditations, try writing out your own in advance, practicing them on your own and testing them with a small, experienced team before using them in group ritual.

When it is time to end the trance journey, it is important to guide people back slowly. Do the steps of the journey in reverse, taking more time to draw people back out than you did to plunge them in. You and your warder should be keeping an eye on people’s reactions, particularly if they are showing any physical or emotional responses to the experience. When everyone is out of trance, check in with the group and ask about their experience.

If anyone had strong responses, they should be spoken to one-on-one, either with the warder taking them aside or making time after you have finished helping the group decompress. Helping people decompress is very important to having a healthy, sustainable trance experience.

Organizing Group and Community Rituals

When planning a ritual, you should include as many participation opportunities as possible. Providing engaging activities for ritual participants helps bring people together and makes ritual more fulfilling and empowering for all involved. If there is anything the whole group can be part of—such as an invocation or setting the space—then go for active participation and inclusion over leaving them out as a passive audience.

In some cases (usually well-organized communities), it is possible to have access to or possess a sacred space known as a hall. A hall is an indoor space used by groups for communal rituals. They can be permanently dedicated spaces owned by community members, a room in a private home, or rented rooms used for a specific ritual. A hall may contain multiple shrines along with space for many people to participate in sacred practice.

Always remember the ten-minute rule for setting the length of ritual segments, whether the segment is a skald telling a story, a v lur team doing trance work, or generally introducing the ritual and telling people what to expect: this rule is based on substantial research that has shown most people are able to keep focus on any one thing or topic for about ten minutes unless they are re-engaged in some way. A famous example of this rule in use is with TED Talks, where each talk, supported visuals, and other presentation aids must be no more than eighteen minutes long. While it is possible to stretch the amount of time you can keep people’s attention (especially if you engage them in several different ways beyond talking), it is best for less participatory sections of a group ritual to be no longer than ten minutes each.196

lur team doing trance work, or generally introducing the ritual and telling people what to expect: this rule is based on substantial research that has shown most people are able to keep focus on any one thing or topic for about ten minutes unless they are re-engaged in some way. A famous example of this rule in use is with TED Talks, where each talk, supported visuals, and other presentation aids must be no more than eighteen minutes long. While it is possible to stretch the amount of time you can keep people’s attention (especially if you engage them in several different ways beyond talking), it is best for less participatory sections of a group ritual to be no longer than ten minutes each.196

It is also a good idea to break up these sections as much as possible. For example, if you are going to have a skald tell a tale from the lore, you should probably put a group chant before the story and follow it up with a round of people giving offerings to the Powers. Scheduling more than two different passive spectator segments back-to-back is a great way for people to tune out and make ritual incredibly boring.

Rituals are also community-building events and opportunities for socializing. You should set aside some space for people to hang out before things get started, which also gives time for latecomers to arrive, as well as to chat afterwards. This also gives space for people to process what happened in the ritual, especially if it was more intense.

Make sure to schedule time before and after the ritual for any setup and packing that needs to happen. There should be volunteers whose job is to make sure this happens, however, it is always a good idea to ask participants to help. Ritual setup should be completed before the participants arrive. The only real exception is if you have food that should be served hot. Such dishes can be kept warm so they will be ready when it’s time to eat.

As with solitary practice, sacred space is set by invoking the powers of fire and ice to call on the primordial forces that created reality as we know it. Symbolically re-creating this moment clears the way for the work of the sacred to begin. The easiest and most reliable method for doing this in a group environment is to use collective chanting. Divide the participants into two roughly equal-sized groups. Have one group chant Kenaz, the fire rune, while having the other group chant Isa, the ice rune, at the same time. You can do this as a single, prolonged tone or through steady repetition of the runes’ names. You could also have each group perform a simple, pre-written chant that invokes the powers of the fire and ice runes, incorporates music like drumming, or includes simple dance moves. Regardless of the method used, what matters most is making sure everyone present is participating in the process and that the powers of fire and ice are invoked at the same time.

Creating Engaging Rituals

Just as solitary ritual builds relationship and understanding of the Powers, group ritual does the same for all participants. It is critical that all participants in group rituals are as engaged, involved, and active as possible, lest your ritual become nothing more than a performance that excludes everyone who is not at the center of the action. There are several ways to bring people in; your methods will depend on the goals of the ritual, your group’s skills, and the participants.

The easiest activities are music and chanting. Whether performed using instruments, the human voice, or played from a recording, music has been used in spiritual practice by societies across time and space. The widespread use of music in spiritual acts across many different cultures shows how effective it is in creating ecstatic states. In the case of the pre-Christian Norse peoples, there are records of skalds singing spell-songs and using poetry forms like ljodhattar for invocations. You can incorporate music using everything from acoustic instruments accompanied by chants, to recordings of bands blasting the right music from amps and speakers.

Regardless of the specifics, there are a few key points to remember when using music or chanting as a ritual tool. Any musical elements should be intended to get people involved in what is happening. The best way to do this is to keep chants and songs as simple, easy to teach, and repeatable as possible. A member of the ritual team, usually the skald, should teach the chants to be used to all participants before any ritual chanting begins. They should then lead all participants in the chant.

There are also specific ways of conducting chants that are effective for bringing people in. Call and response and singing in rounds are two popular, effective tools for creating highly participatory group chants. One effective approach, widely used in Reclaiming Witchcraft, is a group tone or humming together to bring everyone in sync.

If you are using musical instruments, always include parts that are simple and easy for people to join in, such as parts that keep the rhythm, i.e., drums, simple percussion instruments, or even clapping and stomping. This doesn’t mean you can’t include more complex elements, such as an elegant guitar melody or harmonies played on flutes, but things of that nature should rest on a foundation of simple, easy-to-teach parts performed by all participants. If you use participatory music like chanting, then a member of the ritual team (usually a skald) should teach participants the group part and lead it. This person should not be the same person responsible for leading the chant.

Dance is another method for getting people involved. The dances you use should be chosen based on what is easiest for people to learn and join, whatever the ritual team is most familiar with, and whatever achieves the desired result—it can be anything from folk dances to a mosh pit. As with music and chant, the most important thing here is that the dance is easy to teach, learn, and gets as many people involved as possible. Members of the ritual team should show all the participants how the dance is done beforehand and also lead the dance. If you are incorporating music and dance in the same ritual, the best way to handle it is having a pre-determined group of people handle the music so more participants can focus on dancing or have people who are less comfortable dancing play supporting music parts. It is best to use larger group dances, as they bring people together better than separating a large group into smaller chunks.

A more performance-based method you could use is skaldic recitation. A skaldic recitation is when a skald tells a story, recites poetry, or engages in a poetry battle (known as a flyting) with another skald. On the surface this seems simple, but there is a lot more to an effective recitation than simply speaking verse or rattling off a story. Delivering information to participants in a ritual is actually the bare minimum of what a skaldic recitation should be. An effective recitation pulls all the participants in, engages them on as many levels as possible, and inspires a strong reaction from the listeners.

There are some reliable techniques for making a recitation engaging for the participants. The most important is for the skald to decide, in cooperation with the ritual team, is what is the desired reaction from the participants. Any skald engaging in any sort of recitation needs to earn the participants’ attention. To go in assuming you already have it will usually leave people bored and tuned out. If there is a competitive aspect, such as a poetry battle or a storytelling competition, the outcome should be determined by the participants instead of members of the ritual team. Good ways for learning effective techniques for skaldic recitation are going to poetry slams, live storytelling, studying improvisation, and watching effective public speakers. Above all else, skaldic recitation is a performance; anyone reciting must remember they have to earn every second of the participants’ attention, energy, and focus.

Another effective tool is ritual drama. The most important element of ritual drama is determining what the ride is for the participants. Along with the obvious elements of plot, characters, and conflict, every story has some sort of journey invoked in those watching it unfold. This can be intellectual, emotional, moral, a combination of some, or all of the above. Professional theatre director and Reclaiming Witch Patricia says that what’s important is:

[t]he distinction between theatre and ritual is intention and audience/celebrant participation. Although theatre and ritual drama are both are ideally acts of transformation, ritual drama sets a high bar. Every act of theatre needs to earn its keep by always keeping the audience’s experience in mind, the audience’s ride. This is more true of ritual drama where the best intentions of performers, well-chosen archetypes and plots must ask how the next section moves the participants, called audience or spectators in straight theatre. Failure to do this may result in a well-intentioned history pageant reminiscent of Sunday school nativities.

Unlike other forms of engagement, ritual drama requires a lot of advance preparation. Stories need to be scripted in language that is engaging and easy to understand. Actors need to be recruited and rehearse until the story is second nature for them. The heart of any ritual drama is starting with the core intention of the drama and building outward from there.

Ritual drama can be very powerful when done effectively, but it also risks leaving most of the participants out of the action, reducing them to passive spectators. Thankfully, there are specific forms of drama that offer ideas for how to keep participants engaged in the action instead of sitting on the sidelines. Street theatre is one place to look for ideas with special mention going to forms that break the fourth wall and invite spectators to participate. The works of William Shakespeare also provide examples of direct audience engagement, especially when performed by experienced Shakespearian companies. The works and theories of playwright Berthold Brecht also provide a handy guide for creating engaging drama.

Patricia recommends studying the Greek dramas and Christian mystery plays from the Middle Ages as templates because “they have a clear objective or teaching and use popular theatre tropes such as the everyman, the chorus, masks and symbolic props/costume, antagonist vs. protagonist, that are easily recognizable in any culture.” Regardless of what you use for inspiration, make the time to see a few performances in person or consult someone with theatrical experience before writing and staging a ritual drama.

ritual

Sample Group RITUAL Outline

Setup

As much time as needed, generally 15 to 30 minutes

This is the time when the ritual team arrives, conducts any work for physically preparing the space to be used for public ritual, sets up any altars or shrines, and lays out space for any food and drink. If there’s any food preparation that needs to take place on site, this is the time to do it.

Doors Open

Doors open is the time you have told people to arrive by before the ritual begins. You should give yourself enough time while planning to make sure all setup will be finished by doors open.

Meet and Mingle

30 minutes at most

This is time for people to show up, lay out any food in the designated area if the event is a potluck, socialize, find space to sit or lay out their things if the ritual is taking place outdoors, and for any latecomers to arrive. This period should be no more than thirty minutes, especially if your group does regular public rituals. If this period goes on for too long, people get bored and you implicitly communicate that it’s alright to be consistently late to events. This can cause frustration for other participants, especially if they are operating on tight schedules, have limited energy, or have other time-related concerns. Keeping things punctual is a good practice, and the opening meet and mingle portion tends to be one of the most likely places for time to run over.

Meet and mingle should not be used as time for completing unfinished setup, as this makes the ritual team look unprepared. It is totally alright to cut this portion short if people seem ready to get started and all expected participants have arrived.

If you are expecting new people to be arriving at the ritual, please make sure there are members of the ritual team or your group who are there to greet them, help them feel welcome, answer any questions, and explain how things work. Please be friendly, hospitable, listen to them, and address any concerns they may have. Nothing turns new people off more or guarantees they’ll never come back than failing to engage with them or helping them feel like they belong. Be kind, and where reasonable, give them the benefit of the doubt.

Introduce Your Group, Statement of Principles,

Ritual Intent, and Sequence of Events

5 minutes at most

The goðar introduces the group to everyone, whether you are an ad hoc ritual team, a regularly meeting fellowship, or whatever else the case may be. Read your group’s principles of unity and hospitality statement. More information on how to write these and what they should include is covered in the chapter on community organizing. Explain the sequence of events for the ritual, how people are expected to participate in each section, and what is involved.

Set Space

5 to 10 minutes

The goðar takes the lead, beginning by invoking the powers of fire and ice, followed by members of the ritual team inviting the Powers to participate. Always make sure to ask permission of the local spirits to use the space for ritual and invite the local dead before invoking any other Powers. You can make this portion participatory by including a simple chant recited by the whole group, some drumming or background music and possibly some kind of simple movement all people can participate in. If there are other things your group does to set space, such as lighting incense, walking the space, or anything similar, now is the time to do it.

Shift Consciousness

10 to 15 minutes

The purpose of this section is to get the participants more engaged, active, and into an altered state of consciousness. It is usually best to begin with a guided group meditation led by the v lur, which can be based on the World Tree Within meditation. After this is finished, the skald should lead the group in more energetic drumming, dancing, or chanting to help ramp up their energy. The chants used should be ones that are most appropriate for the ritual’s purpose. It is usually best to begin with steady, even chant and beat before moving to faster, more energetic ones. The skald should play this by ear, read the participants’ mood, and get everyone to a point where they are energized but not tired.

lur, which can be based on the World Tree Within meditation. After this is finished, the skald should lead the group in more energetic drumming, dancing, or chanting to help ramp up their energy. The chants used should be ones that are most appropriate for the ritual’s purpose. It is usually best to begin with steady, even chant and beat before moving to faster, more energetic ones. The skald should play this by ear, read the participants’ mood, and get everyone to a point where they are energized but not tired.

Ritual Activity

10 to 20 minutes

This is the section where the focal action of the ritual takes place. If there is a specific activity associated with the purpose of the ritual, such as a game, a symbolic action, seiðr, ritual drama or a skaldic recitation, this is the time to do it. Make this activity as engaging as possible. For ritual dramas and skaldic recitation, please follow the guidelines provided earlier in this chapter on how to perform these activities in an engaging fashion. Whatever the activity, the goðar will be responsible for facilitating as necessary in addition to whatever other functions are handled by the other members of the ritual team.

Blot

10 minutes

The goðar leads the blot (outlined in chapter four). If you are conducting a large group ritual where passing around a plate of shared offerings or drinking horns would be time-consuming or logistically challenging, the ritual team should set out portions of the food or drink and distribute them to all practitioners before the goðar performs the blot invocation.

Take the Omen

5 to 10 minutes 197

The v lur asks the Powers for guidance and performs divination for the group. Depending on the group and those involved, this could be a rune-casting, as discussed in Chapter six, where the results are read to the entire group. It could also be utiseta or spae seiðr, as discussed in chapter seven, if the v

lur asks the Powers for guidance and performs divination for the group. Depending on the group and those involved, this could be a rune-casting, as discussed in Chapter six, where the results are read to the entire group. It could also be utiseta or spae seiðr, as discussed in chapter seven, if the v lur is trained in either of these arts and feels comfortable doing so.

lur is trained in either of these arts and feels comfortable doing so.

Thank the Powers and Participants

5 minutes

The ritual team thanks the Powers for their presence, those working in supporting roles for their labor and the participants for coming to the ritual.

Decompress

10 to 20 minutes

This is time for everyone to socialize post-ritual, enjoy the food and drink provided, and come back from the altered state brought on by ritual activity. This is also time where the ritual team should address any questions from participants who need help processing anything that happened during the ritual. This time goes on for as long as needed or until it is time to leave if you are in a time-sensitive space, such as a rented room or a private home where the hosts have given a specific, necessary end time.

Clean-up

The ritual team, along with any additional volunteers, cleans everything up. Please always leave whatever space you used better off than you found it. No matter where you are holding a ritual, always leave no trace.

Confronting Fascism

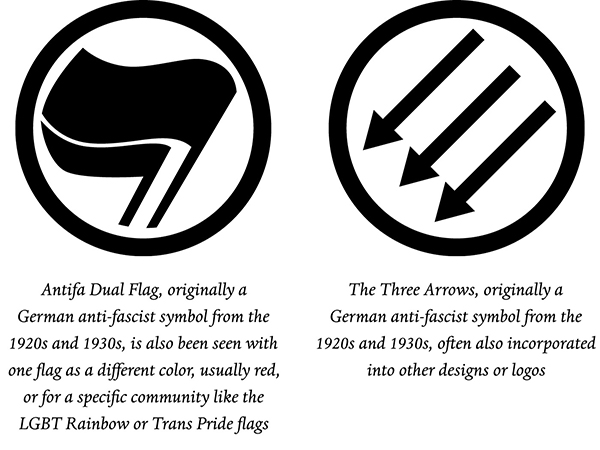

One type of work all Norse Pagan communities need to participate in is confronting fascism and driving it out from our communities, whether those are our spiritual communities or the places we live or work. Confronting fascists is necessary for building truly safe, inclusive communities and attracting more inclusively-minded people. On a grand scale, the problem of fascism can only truly be defeated by removing the conditions in society that enable and encourage its growth. The work of pushing it out of your local community, confronting fascist actions, and building alliances with anti-fascists are all steps needed to accomplish this goal.

There are many compelling reasons to confront and remove fascism, but the most important are moral and practical. Morally speaking, everything fascists, fascism, and their neo-Volkisch allies stand for is completely at odds with Radical Norse Paganism and the sources other Norse Pagan traditions use for inspiration. Standing between fascists and their intended victims in whatever way you can is the right thing to do. Practically speaking, fascists present a clear and present danger to anyone who does not submit to them. Anyone they call undesirable or degenerate are not even treated as people, and they face threats, physical and psychological harm, or even deadly violence. And to be clear, even those who have lashed themselves to the fascist yoke are not safe from their own brutality. Letting fascist groups operate unchallenged puts people in danger. This cannot be tolerated and must be confronted on every level possible.

Securing Community

The foundation of securing community is knowing how fascists operate. A lot of the basics in identifying them are in the earlier sections on the neo-Volkisch and understanding fascism in chapter eight. Those guidelines are useful for anyone seeking safe, genuinely inclusive community, but keeping fascists out of existing communities requires an additional set of skills. These skills are based on knowing the general patterns fascist groups tend to follow: passive fascists, active fascists, and entryists.

Passives are either people who repeat neo-Volkisch and fascist ideas from a place of ignorance and misinformation, or sympathize with fascist ideas but are not actively organizing, promoting, or advancing them. It is important to point out that people of this persuasion are not exactly the same as those who may have conservative political opinions. Passive fascists, unlike people with conservative or other right-wing political beliefs, promote covert and overt fascist material online and in person. Some are members of fascist groups but may be in denial of the group’s true nature, clinging to claims of shared heritage as a defense. Inclusivity statements are useful for attracting the misinformed who are seeking genuine community and deterring passives who are more entrenched in fascist ideas.