WE HAVE SEEN HOW EARLY EXPERIENCES can lead to secure or insecure functioning. If childhood needs are mostly met, our brains develop strong wiring to prevent false alarms from taking over. But to the extent that our basic needs are frustrated early on, our wiring will not be as well developed. As adults, our higher brains may be more easily taken over when our alarms react. We are more apt to believe the scary stories our brains make up. And we will be plagued by triggers and reactivity in our relationships.

In this book, we refer to any interaction that triggers reactive feelings as a reactive incident. Some are obvious, like when one person erupts in anger. Others are not as obvious at first glance, like when you feel disappointed about something but do not tell your partner. Many reactive incidents get brushed under the carpet, only to resurface later in some out-of-proportion way.

Any of the control patterns listed in chapter 7 can cause partners to feel disconnected or out of synch and start a reactive incident. But reactivity can also get stirred accidentally by seemingly innocuous behaviors. As with Donna and Eric, a shift in vocal tone may trigger someone’s alarm. Even something as seemingly innocuous as looking at one’s cell phone too often can do it. Often an initial triggering stimulus is not clearly recognized and a reactive incident starts before anyone notices. By then, typically, both partners are cotriggering each other.

Here are a few important things to remember about reactive incidents:

![]() If you get triggered, this triggers your partner. A couple’s two alarm systems are so highly interactive that they almost always automatically set each other off. For instance, as you get upset, changes in your facial expression and tone of voice start to sound dangerous to your partner’s alarm.

If you get triggered, this triggers your partner. A couple’s two alarm systems are so highly interactive that they almost always automatically set each other off. For instance, as you get upset, changes in your facial expression and tone of voice start to sound dangerous to your partner’s alarm.

![]() When you are triggered, you are under the influence of the strong biological chemicals and the body states of your fight-flight-freeze survival response.

When you are triggered, you are under the influence of the strong biological chemicals and the body states of your fight-flight-freeze survival response.

![]() When you are triggered, you automatically fall into one of your reactive behaviors. Rather than communicating about core (vulnerable) feelings or needs, you will tend to escalate your upset or shut down in some way.

When you are triggered, you automatically fall into one of your reactive behaviors. Rather than communicating about core (vulnerable) feelings or needs, you will tend to escalate your upset or shut down in some way.

This chapter describes the softer, core emotions and needs underneath your reactive behavior and communication. It explains what is really going on when you get triggered and what you actually need to feel safe and secure with your partner.

In a step-by-step process, you will analyze a past reactive incident. With the help of a new vocabulary, you will be able to understand and then speak about what is authentically going on in your heart. This will open new neural pathways, strengthen your brain’s wiring, and enable you to stay present and conscious when you get triggered.

Elements of a Reactive Incident

You can look at any reactive incident in terms of what you or someone else did, what you were thinking after it happened, and what you were feeling. A reactive incident usually starts with a triggering stimulus, which can be any verbal or nonverbal cue. Sometimes the triggering stimulus will be words that resemble the criticism of a parent or a parent’s lecturing voice tone or upset facial expression.

This triggering stimulus gives rise to thoughts or reactive stories — the words that play in your head, such as, “Nothing is ever enough for her,” or “He doesn’t care about my feelings.” After any upsetting event, your storytelling brain will try to make sense of it, filtering it through the lens of past disappointments and fears.

Being triggered also leads to some form of reactive behavior, such as blowing up, shutting down, complaining, offering advice, or any of the control patterns listed in chapter 7. You tend to react with habitual coping strategies that help you avoid your real feelings. Remember, not all reactive behaviors are obvious. When you shut down and clam up, this, too, is a reactive behavior.

Accompanying reactive stories and behaviors are reactive feelings. The most noticeable reactive feelings are anger, resentment, contempt, disappointment, anxiety, overwhelm, confusion, fear, and going numb. These emotional states will be accompanied by body sensations.

Other types of feelings may be harder to notice. Underneath reactive feelings lies a deeper layer of softer, more vulnerable feelings. These are often overlooked. Later in the chapter we’ll discuss these less-visible core feelings. For now, let’s examine the reactive feelings that get triggered, since these are what foster frustrating or unproductive communication.

As an example, we’ll dissect how Donna and Eric thought, acted, and felt on their ill-fated date night (described in chapter 5). Initially, Donna was triggered when Eric kept looking at his cell phone for messages from colleagues. Initial triggering stimuli can be subtle, even subliminal. In this case, Eric breaking eye contact and checking his cell phone triggered Donna’s reaction.

Each time Eric pulled out his cell phone, Donna felt twinges of frustration. She felt a knot growing in her belly. But what really took over her attention were the reactive stories in her head. These escalated her reactive feelings and led to reactive behaviors, such as her complaint, “At least the waiter listens to me!”

Here is a summary of the typical reactive stories, feelings, and behaviors that arise when someone like Donna gets triggered and starts communicating with a sword:

Reactive Stories: “I’m alone.” “I’m shut out.” “He doesn’t care.” “My feelings don’t matter.” “I come last.” “I’m not sure I matter.” “I can’t seem to reach him.”

Reactive Feelings: irritated, frustrated, annoyed, angry, resentful, infuriated, enraged, anxious

Reactive Behaviors: pursue, prod, provoke, pressure, question, complain, criticize, yell, blow up

In reaction to Donna’s complaining, Eric was gripped by a familiar sense of hopelessness. His chest felt heavy, and the reactive story came up in his head that his efforts were never good enough for Donna. He tried to ignore Donna’s anger and talk about other things, but this did not work. Donna’s reactive stories persisted, and she became even more agitated and upset. By the end of the evening, their cotriggering behavior, which neither was able to stop, developed into a full-blown fight.

The following summary of reactive stories, feelings, and behaviors are typical of a partner like Eric who, when triggered, starts communicating with a shield:

Reactive Stories: “I can never get it right.” “It all seems hopeless.” “I’m a failure as a mate.” “I must be flawed.” “I need to keep things calm.” “I’m trying to solve the problem.”

Reactive Feelings: hopeless, stuck, blank, empty, numb, not feeling, confused, paralyzed, ashamed

Reactive Behaviors: withdraw, ignore, hide out, avoid, distance, space out, shut down, stay logical

As we’ve seen, Donna and Eric’s reactive behaviors cotrigger each other. We refer to this circular pattern as a reactive cycle. The more Donna pursues and criticizes, the more Eric ignores and withdraws, and vice versa. In relationships, our reactive stories and feelings can trap us in this type of vicious cycle.

The Reactive Cycle

It is important to see how a reactive cycle is circular.

You get triggered by something your partner says or does, and you automatically react in some way. The reactive behavior you engage in will then trigger your partner. Thus triggered, your partner will start acting out his or her own reactive behavior — which only further triggers you!

In this way, we end up simultaneously cotriggering each other, but we rarely see the full picture. All we usually see is what our partner did to upset us. We think, if he or she would only stop doing that thing, then everything would be okay again. But each person is responsible for keeping a reactive cycle going.

The initial triggering stimulus behavior that starts reactivity may be different than the pair of reactive behaviors that create a full-blown reactive cycle. For instance, on their date night, Eric’s glancing at his cell phone was a triggering stimulus for Donna. Her reactive behavior was to complain, which triggered Eric to ignore. That pair of reactive behaviors — complaining and ignoring — created their cycle. If either partner interrupts the cycle by not engaging in a reactive behavior, cotriggering will not occur. If Eric had called for a pause instead of ignoring, a reactive cycle would have been prevented.

Often it’s hard to say where a reactive cycle even starts. By the time you’re aware of your own distress, it is already in motion. When this happens over and over, a couple will tend to get stuck in one familiar reactive cycle. This whole process is quite unconscious. To get free of your reactive cycle, you first need to identify it and see the full picture.

To understand how your particular reactive cycle operates, it’s best to look at each puzzle piece in turn. Let’s start with the typical reactive stories. Then we will look at reactive behaviors, and finally, we will examine reactive feelings and body sensations.

If you are in a relationship, invite your partner to read this material with you. Doing this together will give you the ability to spot your cycle when it begins, so you can step outside of it and stop being at the mercy of your reactions.

If you are currently single, use this information to help understand any reactive cycles that may have existed in previous significant relationships. This will help you see how cycles work so you can prevent them in your future relationships.

Reactive Stories

Reactive stories are what your storytelling brain feeds you to explain why you are upset. As discussed in chapter 5, the meaning-making part of your brain makes up a reasonable-sounding story to explain why your partner is doing something, what it means, or why you should be upset about it. As we’ve seen, these are often worst-case scenarios that result in self-triggering.

In chapter 5, we presented a list of reactive stories and asked you to check off any that come up in your head when you get upset. (See “Stories That Keep Us Triggered,” page 72, appendix B, or the online workbook’s “Reactive Stories” section, available at www.fiveminuterelationshiprepair.com.) Go over this list again and circle the three stories your mind comes up with most often. As we will see, our reactive stories misrepresent what is actually happening with our partner. In fact, believing our story keeps us from sharing our deeper needs and feelings. As we realize this, the power of our self-triggering stories starts to fade, and we are able to experience our real feelings.

Reactive Behaviors

The next puzzle piece — reactive behaviors — are what we say or do when we are triggered. Once a reactive cycle has started, these are the things we do that elevate each other’s levels of activation and keep the cycle going — as we’ve seen with Donna and Eric.

As you look over the list of reactive behaviors below, they may seem similar to the control patterns in chapter 7. Reactive behaviors are control patterns, but of a specific nature. The reactive behavior of one partner pairs up with the reactive behavior of the other to create a reactive cycle. They form a circular pattern of cotriggering. The more Donna complains, the more Eric ignores. The more he ignores, the more she complains, and their cycle keeps escalating. These reactive behaviors are the ingredients that keep their reactive cycle in play.

A control pattern may come up anytime, without provocation, as an automatic, habitual way your unconscious mind tries to help you feel more in control. Certainly, your use of a control pattern can trigger your partner. Eric’s automatic tendency to jump in and give advice instead of just listening could trigger Donna. Donna’s reaction — her complaints — could then trigger Eric’s reactive behavior of ignoring. And this, in turn, could trigger her even more. That is their cycle.

In the following list, put a check next to any reactive behaviors you have used when in distress in your relationship. (Or do this exercise in the online workbook’s “Reactive Behaviors” section, at www.fiveminuterelationshiprepair.com.)

![]()

Try to fix the problem with logic, solve it rationally

Try to fix the problem with logic, solve it rationally

![]()

Agree insincerely, placate

Agree insincerely, placate

![]()

Rationalize, intellectualize to avoid emotions

Rationalize, intellectualize to avoid emotions

![]()

Make a joke or cute remark, laugh it off

Make a joke or cute remark, laugh it off

![]()

Ignore, pretend it doesn’t matter or you didn’t hear

Ignore, pretend it doesn’t matter or you didn’t hear

![]()

Avoid, distance yourself

Avoid, distance yourself

![]()

Leave, walk out, move away

Leave, walk out, move away

![]()

Withdraw, hide out

Withdraw, hide out

![]()

Act confused, freeze up, space out, shut down

Act confused, freeze up, space out, shut down

![]()

Correct other person, argue the point, debate

Correct other person, argue the point, debate

![]()

Defend yourself

Defend yourself

![]()

Ridicule, get sarcastic

Ridicule, get sarcastic

![]()

Make insulting noises or faces, roll your eyes

Make insulting noises or faces, roll your eyes

![]()

Talk over the other, interrupt

Talk over the other, interrupt

![]()

Repeat yourself

Repeat yourself

![]()

Get sullen or sulk

Get sullen or sulk

![]()

Mutter to yourself

Mutter to yourself

![]()

Compare partner to someone “better”

Compare partner to someone “better”

![]()

Label, judge, name-call

Label, judge, name-call

![]()

Complain

Complain

![]()

Lecture, teach, preach

Lecture, teach, preach

![]()

Pursue, push, pressure, prod, provoke

Pursue, push, pressure, prod, provoke

![]()

Talk loudly in an anxious tone

Talk loudly in an anxious tone

![]()

Interrogate, question, ask for explanations

Interrogate, question, ask for explanations

![]()

Try to prove you are right

Try to prove you are right

![]()

Attack or blame

Attack or blame

![]()

Yell, blow up

Yell, blow up

![]()

Guilt trip

Guilt trip

Now go over this list and circle your three most common behaviors — those that best portray how you usually operate when there is distress. If you aren’t sure, think of how you have reacted when the three reactive stories you circled in the previous section seemed true to you.

Finally, underline the three behaviors in the list that represent what your partner does that triggers you the most. Make note of any connections you see between your three reactive stories and your partner’s three most triggering behaviors. In this way, you can start to identify your particular reactive cycles.

Spotting a Reactive Cycle

Now write down your own three most-common reactive behaviors, which you circled, and your partner’s three reactive behaviors, which you underlined. See if these behaviors can be paired. Does one of your partner’s behaviors often trigger one of your common reactions? Fill in the following incomplete sentence for any that pair up in this way, either writing them on a separate sheet of paper, in your journal, or using a printout of this exercise from the online workbook’s “Spotting a Reactive Cycle” section (available at www.fiveminuterelationshiprepair.com).

When my partner ______________________________ [insert your partner’s reactive behavior],

then I tend to _________________________________ [insert your own reactive behavior].

As an example, Donna wrote: “When my partner ignores, then I tend to complain.” Interlinked reactive behaviors can also pair up in a variety of ways, so write down any variations. Don’t worry about doing it perfectly. In fact, if you find other words that fit better than what is offered here, add these additional reactive cycle sentences. In Donna’s case, she added: “When my partner avoids, then I tend to criticize,” and “When my partner withdraws, then I tend to yell.”

A reactive cycle starts with either person. Your partner may do something that you react to, or your behavior might trigger an automatic reaction in your partner. For instance, let’s say your reactive cycle sentence was the same as Donna’s: “When my partner avoids, then I tend to criticize.” However, it may be equally true that when you criticize, your partner tends to avoid. A pair of interlinked behaviors feed each other and create the same cycle, no matter how it starts. In other words, cycles are cocreated by both partners. Each triggers the other.

As we saw in chapter 6, Donna and Eric have opposing reactive communication styles, with Donna preferring the sword and Eric the shield. Each partner might exhibit different reactive behaviors in different situations, but they almost always trigger the same dynamic, in which Donna is the preoccupied pursuer, while Eric avoids and withdraws.

Your Typical Reactive Cycle

Now let’s complete the description of your reactive cycles. Look at all the reactive cycle sentences you’ve written down and reverse them. For instance, Donna reversed her sentence, “When my partner ignores, then I tend to complain,” so that it became, “When I complain, then my partner tends to ignore.”

Reactive cycles are equally true no matter which reactive behavior happens first. Seeing this helps us see our own responsibility for creating and maintaining each cycle. Do this reversal with each pair of reactive behaviors you identified. If it makes more sense, combine behaviors to create a more comprehensive picture of a reactive cycle. For instance, “The more my partner prods and criticizes, then the more I withdraw and shut down. Conversely, the more I withdraw and shut down, then the more my partner prods and criticizes.”

Congratulations! You are on your way to identifying your most common reactive cycle! Fill in the following sentences, either writing them on a separate sheet of paper or using a printout from the online workbook’s “Your Typical Reactive Cycle” section (available at www.fiveminuterelationshiprepair.com).

The more my partner __________________________ [insert your partner’s reactive behavior],

then the more I ______________________________ [insert your own reactive behavior].

Conversely, the more I ________________________ [insert your same reactive behavior],

then the more my partner _____________________ [insert your partner’s same reactive behavior].

Reactive Feelings

The next piece of the puzzle is the reactive feelings that get triggered in a reactive cycle. When we experience escalating distress, we fall into one of the three Fs — fight, flight, or freeze. The reactive feelings we experience in a cycle correspond to one of these Fs.

As described in chapter 1, being in the state of fight corresponds to feeling angry, the state of flight corresponds to feeling anxious, and the state of freeze corresponds to feeling numb. These three internal states actually include a range or group of reactive feelings, which can vary in intensity.

In chapter 1, we asked you to put a check next to any reactive feelings you frequently experience when there is distress in your relationship. Review this list now (see “Which ‘F’ Overtakes Your Higher Brain?” page 24, or appendix B). Then, on a separate sheet of paper (or using the online workbook’s “Reactive Feelings” section), write down what you do when you experience each reactive feeling — that is, how you reactively behave when you feel this way. Make sure to place within this list the reactive behaviors you circled for yourself under “Reactive Behaviors” above.

Congratulations again! You now see more of what happens when you are triggered. You are well on your way to becoming free of these automatic reactions!

Body Sensations Are Early Warning Signals

As you feel triggered, you experience certain body sensations that correspond to your reactive feelings. As we have seen, the nervous system controls various organs in the body, and these organs function differently when your survival alarm gets activated versus when you are calm. When you are triggered into states of fight or flight, your body pumps more adrenaline, your heart speeds up, and your digestion shuts down.

By paying attention, you can detect these shifts within your body. You might, for example, feel a pressure in your chest, a knot in your stomach, or a pounding in your solar plexus. You may notice your muscles getting tight. These are the body sensations that tend to accompany reactive states like feeling frustrated or anxious.

Most people don’t pay much attention to sensations in their bodies when they are upset. Their focus is on their reactive feelings and stories. But it is very useful to become more aware of your body sensations. They are early warning signals that your survival alarm is ringing and a reactive cycle has started. Increasing your alertness for telltale bodily sensations will increase your ability to stop a cycle sooner. It is easier to recover from a reactive incident when you can halt the cycle before falling too far into the Hole.

As we’ve seen, both Donna and Eric experience physical reactions when they get triggered. But they tend to ignore these and become fixated on their reactive stories. Stories are part of our secondary reaction to getting triggered. Body sensations are a primary event in the nervous system. They occur even before our minds have a chance to fabricate worst-case scenarios.

To learn to identify your body sensations, try this exercise. Pick the most common reactive feeling you experience. Recall in detail a time when you experienced it: what your partner said or did and how you reacted. Imagine the event as if it were happening again now.

As you replay this scene in your imagination, notice the sensations that come up in your body. Now describe the sensations — for example, as a knot in your stomach, feeling heat or coldness, a tightness somewhere, a constriction or pounding in your chest or belly, a lump in your throat, a weight on your shoulders, a heavy feeling, a fluttering sensation, a pain in your heart, a shakiness or tension, and so on.

Core Feelings and Core Fears

When we are triggered, two kinds of feelings arise. On the surface we have reactive feelings, but under these are our core feelings and core fears. Since core feelings get masked by reactive feelings, we’re rarely aware of the tender emotions at the root of our reactions. Certainly, if we’re unaware, our partner won’t be aware of these either.

On a reactive level, Donna felt angry when Eric checked his cell phone on their date night. But what core feelings and fears were hidden underneath her anger? She actually felt hurt and afraid. She felt hurt when she imagined she did not matter to Eric. Her fear-of-abandonment button got pushed when she thought she was all alone and that he was not really interested in being with her. Core fears are also known as our fear buttons.

Why couldn’t Donna directly express her core fears? She was programmed in childhood to believe that signaling distress simply and directly was not an option. Being that vulnerable never seemed to work for her. In infancy, her parents did not coregulate her very consistently when she cried. When she was a child, they often ignored, laughed at, or belittled her when she tried to express her hurts or fears.

Angry protest, a typical reactive behavior in preoccupied children and adults, became little Donna’s way of expressing her distress. Now, as an adult, her core fears and vulnerable tears get masked by her anger — remaining hidden from Eric and probably from herself. Hearing her complain and criticize, it is impossible for Eric to see that Donna is really feeling hurt, afraid, and alone.

When we do not have valid information about a partner’s core feelings, we tend to make up stories to explain the behavior we see. Our stories arise out of our own unconscious fears. So when Donna complains, Eric’s reactive story becomes that he can never do enough or be enough to make her happy.

Eric rarely considers expressing his own core feelings and needs. Usually, he withdraws before even noticing these core parts of himself. This withdrawal reaction hides his softer, more vulnerable, core feelings — both from himself and from Donna. In this way, Donna’s story that Eric doesn’t care is reinforced by his withdrawal and seeming lack of attention to her complaints.

If Donna had more valid data about Eric’s core feelings, she might be able to see beyond her worst-case story about him. In his core, Eric feels a deep sadness during these reactive cycles. His core fear is that Donna will reject him. He fears being seen as inadequate in her eyes. But he can’t let Donna know this. Such vulnerability is out of the question. As is typical for someone raised in an avoidant home, his nervous system was programmed long ago to believe nobody would respond to his distress. So his pattern is to go numb and hide his feelings. He does this so automatically that he doesn’t even realize when he is upset, since being conscious of distress would just leave him feeling more helpless and inadequate.

Donna has no idea that he has all these feelings. She has the impression that he doesn’t feel much, that nothing affects him. He always looks so cool, calm, and collected. But Eric’s avoidant behavior does not mean he doesn’t have tender feelings and doesn’t care about Donna. In truth, the more important someone is to him, the more likely Eric will react this way! If Donna really knew what was going on beneath his shut-down exterior, she would realize how much he really cares about her, and she would probably want to soothe his sadness and reassure his fears.

Most of us have difficulty expressing our core fears and tears — the soft, vulnerable parts of ourselves. Like most couples, Eric and Donna often keep each other in the dark about the tender emotions they really feel beneath their surface reactions. Neither of them would ever suspect the other person was actually fearing rejection or abandonment. Thus neither partner knows that each of them has the power to interrupt their cycle and reassure their partner’s fears.

In order to interrupt your reactive cycle, it is vital to understand what is at the core of your reactivity. The following lists show the typical reactive feelings that get triggered — and the core feelings and core fears that are usually hidden beneath this reactivity.

Reactive Feelings: annoyed, irritated, frustrated, angry, resentful, infuriated, nervous, worried, insecure, anxious, fearful, panicked, hopeless, confused, ashamed, stuck, numb, paralyzed

Core Feelings: sad, hurt, pained, grief-stricken, lonely

Core Fears: I’m afraid of being . . . abandoned, rejected, left, all alone, unneeded, insignificant, invisible, ignored, unimportant, flawed, blamed, not good enough, inadequate, a failure, unlovable, controlled, trapped, overwhelmed, suffocated, out of control, helpless, weak.

Reactive feelings are the typical emotional states that first come up when you are triggered. These hide the deeper core feelings at the root of a reaction, which generally boil down to feeling afraid. It is useful to separate core fears into their own list, as they are at the root of why our alarms are ringing and why we are reacting with survival states of fight, flight, or freeze. You might consider these three lists as a kind of emotional “parfait” — with core fears at the bottom, core feelings in the middle, and reactive feelings at the surface. Normally, we only see or express the top layer, the reactive feelings.

Generally, a core fear lives at the root of any reaction. Yet, while reacting, it can be difficult to identify what that fear is. The reactive story can offer a clue. For instance, the story “I can never get it right” often points to a core fear of being rejected, inadequate, not good enough, or a failure.

Be curious about the core fears at the root of your reactivity. Everyone has fear buttons, so welcome these new insights rather than trying to cover up your weaknesses. Review the reactive stories you identified earlier in this chapter, then look over the list above and identify the core feelings and core fears that might be stirring beneath your stories.

Core Needs

The most important pieces of the puzzle are the relational core needs of each partner — like the needs to feel respected, safe, and valued. As mentioned in chapter 1, core needs operate like air, food, and water in a primary partnership. In the attachment literature, these are referred to as attachment needs. It is important to feel okay about having such needs and expressing them in your relationship. Otherwise it will be very hard to feel safe with your intimate partner.

Partners need to feel that these core needs are being met. Otherwise, survival alarms will start ringing. Here again is the list of needs from chapter 1:

I need to feel . . . connected to you, accepted by you, valued by you, appreciated by you, respected by you, needed by you, that you care about me, that I matter to you, that we are a team, that I can count on you, that I can reach out for you, that you’ll comfort me if I’m in distress, that you’ll be there if I need you.

Intimate partners need to feel valued, needed, connected, accepted, that they matter, and that they can count on each other. These are core needs for all partners in relationship. When these needs are frustrated, couples fall prey to frequent reactivity and cotriggering.

By recognizing what is really driving a reactive cycle, partners can learn how to reassure each other that they truly are safe — that they are cared for, that they are important, that they are good enough, that they are loved. This is why it is vital to see what is at the root (or core) of your own reactive cycle and to understand how all the pieces of the puzzle fit together.

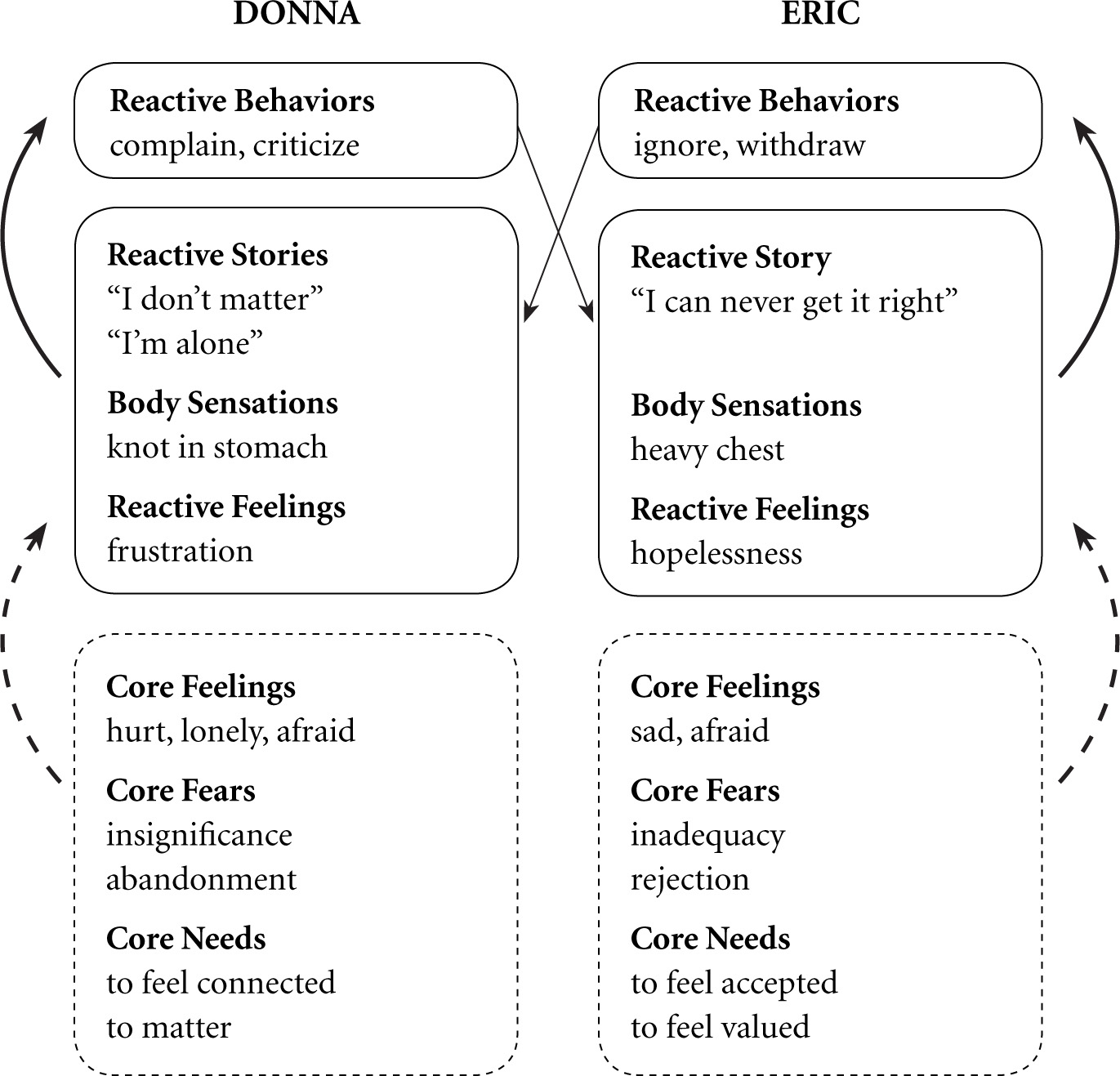

Donna and Eric: Putting the Puzzle Together

Here is a chart that shows how all the puzzle pieces come together for Eric and Donna. This helps us visualize Donna and Eric’s reactive cycle. It shows the core feelings hidden under their reactivity. It reveals what they actually need at those times they get triggered. Seeing all the parts of this puzzle can help them understand the real cause of their upsets and give them a map for spotting, repairing, and ultimately healing their reactive cycle.

A reactive cycle is driven by the needs and feelings in each partner’s core. But because core feelings, core fears, and core needs are often hidden beneath reactive feelings, the cycle persists. Donna’s reactive anger hides both her tender, core feelings of hurt and loneliness and her core fears of being unimportant and unloved. Eric cannot see this hidden part of her, so he never realizes that underneath her angry complaints, she really needs to feel important to him and more connected with him.

Eric reads her anger as evidence for his story that he can never get it right. When he withdraws or shuts down, Donna cannot see his core sadness or his core fear of not being good enough. She never gets to see his need to feel accepted and valued by her.

All they have to go on are the stories their minds create. Believing these stories, they get more triggered. Not understanding each other’s core fears and feelings, they might spend years believing their stories and playing out the same cycle.

When we develop the courage to reveal our softer feelings and needs, we give our partner a way to reassure us and help us heal our fears. Identifying the pieces of your reactive cycle is a vital step in this mutual healing process.

Identify Your Reactive Cycle

Now it’s time to figure out the pieces of your own reactive cycle. To get the most value out of the following exercise, we highly recommend that you download and print the free online workbook (available at www.fiveminuterelationshiprepair.com).

As you do the exercise, you will be asked to pick words from the various lists that appear throughout this book; for easy reference, these lists are gathered together in appendix B, and they are also available in the online workbook. Familiarize yourself with these lists, which you will hopefully refer to again and again. Many people report that these lists expand their vocabulary and help them communicate more intimately with their partner. Review the pair of interlinked reactive behaviors you identified above in the “Your Typical Reactive Cycle” section (see page 121). Use these as a starting point to understand the cycle that plays out between you and your partner (or former partner). Here are those sentence prompts again:

The more my partner ____________________________ [insert your partner’s reactive behavior],

then the more I ________________________________ [insert your own reactive behavior].

Conversely, the more I ___________________________ [insert your same reactive behavior],

then the more my partner ________________________ [insert your partner’s same reactive behavior].

Now recall a specific reactive incident where this cycle of reactive behaviors played out, or you can simply recall any specific incident where you got triggered, even if it doesn’t fit the cycle you identified. Choose a moderately upsetting incident rather than a really intense one. This will make it easier for you to step back and see your pattern.

If your partner is reading this book with you, pick the incident together.

The best way to do this exercise is by downloading the online workbook’s “Triggering Incident Analysis” section. Print out this section twice if you are doing the exercise with your partner. If you don’t have access to the workbook, then do this on separate sheets of paper. If you are single, choose an incident from a previous significant relationship or one from your dating life.

To reiterate an important point, a reactive incident gets started by some triggering stimulus, that is, by something one person says or does — for instance, when Eric looked at his cell phone too often on his date night with Donna. Once triggered, Donna engaged in a reactive behavior (by complaining and criticizing). Her behavior then triggered Eric into engaging in his own form of reactive behavior (by ignoring and withdrawing).

In the following exercise, the initial triggering stimulus behavior may be different from each of your reactive behaviors that cotriggered a full reactive cycle.

1. Triggering Stimulus: In one sentence, describe the specific words or actions your partner said or did that triggered your reaction. Be as objective as you can, describing what would be seen on a video recording of the incident as you started to get activated.

2. Your Reactive Behavior: How did you react? This might be the reactive behavior that you just named on the previous page. However, if you are using a triggering incident that doesn’t fit your cycle, choose the most appropriate item from the list of “Reactive Behaviors” in appendix B or the online workbook.

3. Your Partner’s Reactive Behavior: How did your partner react to your reactive behavior (or continue to act)? This might be your partner’s reactive behavior that you just named above. Otherwise, select the most appropriate item from the list of “Reactive Behaviors” in appendix B or the online workbook.

4. Reactive Story: What story came up in your mind to explain the meaning of what happened? Pick the closest story that matches from the list of “Reactive Stories” in appendix B and the online workbook.

5. Body Sensations: As you recall what you heard and saw, sense how your body felt when you first got triggered. Notice the sensations in detail. What did you feel in your jaw, in your belly, in your heart, in your limbs, in your throat? See “Body Sensations” in appendix B or the online workbook.

6. Reactive Feelings: What reactive feeling came up in you? Pick the closest feeling that matches from the “Reactive Feelings” list in appendix B or the online workbook.

7. Core Feelings: What were your softer core feelings underneath your more hard-edged reactive feelings? Feel deeply into your heart area, and pick one or two core feelings from the “Core Feelings” list in appendix B or the online workbook.

8. Core Fears: Use your intuition about what might have been at the root of your trigger. Pick one or two core fears that may have been activated. Remember, your reactive story will hold clues to what your core fears are. Pick one or two core fears from the “Core Fears” list in appendix B or the online workbook.

9. Core Needs: What core attachment needs got stirred? Pick one or two core needs you feared were not being met from the “Core Needs” list in appendix B or the online workbook.

Next, using the information you identified, make a chart of your reactive cycle similar to the one for Donna and Eric in “Donna and Eric: Putting the Puzzle Together” (see page 128). We recommend downloading the blank chart that’s available in the online workbook’s “Identify Your Reactive Cycle” section (available at www.fiveminuterelationshiprepair.com). Or draw a blank chart on a sheet of paper. Let the chart fill the page, so you have plenty of space to write inside each box; label the boxes as they appear in the Donna and Eric example and include the arrows.

Next, write your name above the left column and your partner’s name above the right column.

Now, fill in all the boxes with the puzzle pieces you identified for yourself. In the appropriate boxes, enter your own specific reactive behaviors, reactive stories, body sensations, reactive feelings, core feelings, core fears, and core needs.

Finally, fill in your partner’s side of the chart. If your partner is doing this exercise with you, have your partner fill in his or her answers in the right column. If not, then guess what went on inside of your partner, doing your best to complete all the puzzle pieces accurately.

Once you have filled in the chart of your reactive cycle, sit with it and consider how it works. Note the arrows between your reactive behaviors and your partner’s reactive stories and vice versa. Follow the arrows and trace how when your partner acts a certain way, it triggers corresponding reactive stories, body sensations, and reactive feelings in you. Note how you then react with your reactive behaviors, and how this triggers the reactive stories, reactive feelings, and reactive behaviors in your partner.

By tracing this progression and becoming conscious of it, we begin to see how all the pieces of our typical reactive cycle fit together. Most of all, we see how the core elements that drive our cycle — core feelings, core fears, and core needs — are hidden under the reactive parts.

Discovering Your Hidden Core

Exploring the hidden aspects of your cycle with your partner can help you let go of your stories and get back to a loving place with one another. You will discover core feelings, core fears, and core needs that you may never have articulated to yourself or to each other.

If you are working together, take some time to discuss your cycle. Look together at how this cycle has played out in a variety of incidents, both large and small.

Be gentle and caring toward each other around your core feelings, fears, and needs. This is profoundly transformative material, and we can feel quite vulnerable sharing these things. Be sure to treat the information like a sacred trust, and never use this information against each other. For instance, if you discuss it with anyone else, do so in a way that honors the trust your partner has put in you.

Once you come to know each other’s core feelings, fears, and needs, you will realize that your partner does value and care about you. People do not get into reactive cycles with just anybody! The degree of your partner’s reactivity is usually directly related to how important you are to him or her.

Remember that in an intimate partnership, feeling that one’s core needs are being met is really important if you want to feel safe and minimize reactive incidents. While your early childhood experiences may have primed you to fall into a particular mode of reactive, insecure functioning, learning to speak about your core feelings and needs will help you transform reactive cycles into opportunities for healing.

As you learn to communicate from a more vulnerable place, your emotional intelligence will grow. You will see how your stories have been inaccurate. You will become less reactive. Your nervous systems will develop stronger wiring. And you will learn — perhaps for the very first time — that it’s possible to create a safe, secure bond with your partner.

Couples therapist Sue Johnson has made vital contributions toward our understanding how reactive cycles operate. If you need further help to identify your cycle, see her book Hold Me Tight.