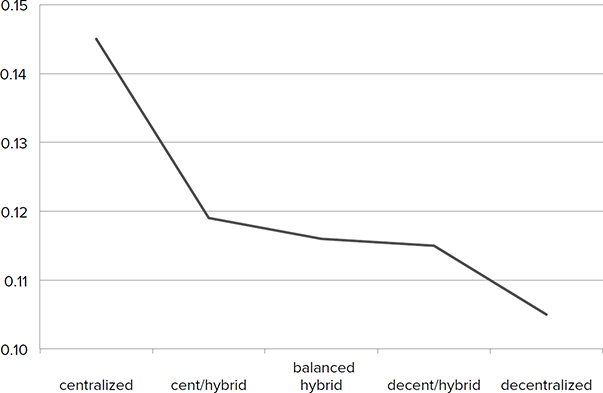

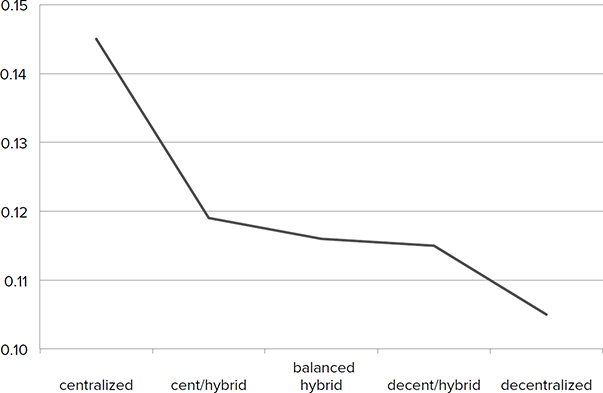

FIGURE 7-1. Centralized companies have 38 percent higher RQ than decentralized companies

Another major trend in R&D over the past few decades has been tighter coupling with marketing—making R&D more commercially relevant. This has led to a shift in the locus of R&D from central corporate laboratories to operating divisions’ laboratories, and from centralized decision-making to decentralized decision-making. Of all the prescriptions discussed so far, the need for more relevance is the one most widely viewed to be valid. In an informal survey of professionals attending RQ workshops, 80 percent of consultants and 90 percent of investment analysts and managers believe that having R&D decisions made by divisions (which are closer to the commercial markets) leads to higher RQ.

This movement toward decentralized R&D began during what Eliezer Geisler calls the “Renewal Period” of industrial science and technology (1984–1993).1 Two trends in this period had considerable impact on companies’ R&D. First, President Ronald Reagan sharply increased the Department of Defense (DoD) budget—much of which comprises industrial R&D. Second, U.S. company dominance in a number of industries, such as steel and automobiles, was threatened by foreign competition. The former provided increased funding for R&D; the latter provided the motivation to innovate.

The first trend, increased defense funding, tended to reinforce centralized R&D. This is because DoD projects are often aimed at pushing the technology frontier to compete in the arms race, which typically involves basic and applied research. However, the second trend, threat from foreign competition, pushed companies in the opposite direction. The principal company response to the foreign threat was to implement total quality management (TQM) programs. The role of R&D in these programs was to generate process improvements to reduce unit cost. This form of R&D is inherently product-specific—redesigning the product to make it more manufacturable, or redesigning the manufacturing process itself. Thus Geisler attributes the shift toward highly relevant, short-term, and product-oriented R&D directly to the mobilization of R&D to support TQM reengineering programs.

This shift toward product-specific R&D reached maturity in the subsequent period and continues today. Accompanying the shift has been a radical decrease in basic research, from roughly 10 percent of companies’ R&D prior to 1984 to approximately 3 percent in the 2000s, as well as movement from central laboratories to divisional laboratories. As central labs began to dissolve, divisions gained more control over the funding of R&D. They largely preferred relevant research with short-term results and low risk.

A concrete example of this phenomenon comes from the experience of Hughes Research Laboratories (HRL) during this period.2 HRL was formed in 1954 as the third division of Hughes Aircraft Company (Radar and Guided Missiles being the other two divisions). We saw Hughes earlier in the ion beam technology story (Chapter 2) and the laser story (Chapter 5). The province for HRL was applied research—coming up with new components and technology that would further the business interests of Hughes. The approach to fulfilling this goal was to hire scientists and engineers with expertise in the technologies related to Hughes’ product lines and to give them free rein. Though there was no grand strategy for the lab, it grew from a population of 200 from the time it moved into its quarters in Malibu, California (1960), to a population of nearly 560 at its peak in 1987.

The forces affecting Hughes during the “Renewal Period” were different from those just discussed, in large part because defense companies typically don’t face threats from foreign competition. The more relevant forces to Hughes were anti–defense industry sentiment that arose in response to Reagan’s increased defense spending, the end of the cold war, and the 1985 sale of the company to General Motors. Interestingly, despite the difference in stimuli, the Hughes response mimicked that of other industrial companies during the period.

One such response in 1988 was the direction from then-president Malcolm Currie for HRL to give the sectors (divisions) “more wheels.” Up until that time very little (less than 5 percent) of HRL’s internal funding came directly from sectors. This occurred when work at the lab was necessary to support sector contracts or internal R&D projects.

In general, it was felt there was little need for sector funds. First, the sectors each had their own R&D efforts to support their forecasted programs, and second, the time horizons of HRL and the sectors differed. HRL was interested in technologies that weren’t expected to have benefit for 5 to 10 years, while the sectors were primarily interested in technologies for known programs. However, when the sectors began downsizing in response to the various environmental elements, they began to challenge corporate to make HRL more relevant: “If I have to cut R&D costs and undergo downsizing, I would like HRL to be more relevant to my needs and more near-term directed.”3

One factor facilitating a transformation of HRL toward “giving the sectors more wheels” was a $10 million shortfall in the construction costs for a second HRL building. Dr. Art Chester, the HRL director, exploited the shortfall to develop a proposal recommending (1) that corporate cover the shortfall, but (2) that each sector be given say over $1 million of the research budget that had already been approved for HRL. If implemented, the proposal would increase sector-directed work from 5 percent to 20 percent of HRL funding. While that was already quadrupling sector funding, the new company president, C. Michael Armstrong, whom GM hired from IBM, established an even higher goal of 50 percent sector funding.

The issue of greater sector funding was hotly debated both at HRL and the sectors. One HRL lab manager felt having directed money that could not be countermanded was important. It provided a clear statement of customer (sector) objectives. However, she also felt it was important that HRL continue to have discretionary funds to shape the direction of future technology. Thus in her view the issue was more one of balance than the appropriateness of sector funding.

Others at HRL, however, felt that the idea of allowing sectors to direct HRL work was inappropriate. One principal scientist felt that HRL should be advising sectors on what was important rather than the other way around—that to be a world-class lab, HRL needed to be looking further ahead than sectors: “Sectors can do their own short-term work better and more cheaply than we can.”

Even at sectors, there were those who felt that the move toward greater sector funding of HRL might jeopardize its contributions. Jim Bailey, a technology manager at one of the sectors, felt that HRL provided two valuable services: it kept tabs on broader technology, and it advanced new technologies. He felt HRL should be doing basic research broadly applicable to Hughes’s businesses. To illustrate his concern, he referred to one lab manager at HRL who had not gotten enough of his tasks funded by sectors. The lab manager was given undirected money for those tasks for one year but was told it was not going to happen every year—“If there is no sector interest, maybe HRL shouldn’t be doing these tasks.” Bailey commented that “maybe HRL should be doing those tasks. Maybe they should be doing exactly those things no one at the sectors knows are needed.”

We can’t tell the outcome of Hughes’s decentralization on RQ because General Motors later affected even greater decentralization by selling Hughes off in pieces: the military businesses for $9.5 billion to Raytheon in 1997, the satellite business for $3.75 billion to Boeing in 2000, and the DirecTV business for $26 billion to EchoStar in 2001.

However, we can see the impact of other companies decentralizing their R&D. Procter and Gamble (P&G) began decentralizing R&D as part of Durk Jager’s (CEO from January 1999 to June 2000) “Organization 2005” initiative. The goals for the initiative were to grow global revenues from $38 billion to $70 billion, while also raising profitability. The decentralization of R&D was intended to accelerate innovation—in particular, time to market.

Jager felt decentralization of R&D was necessary to make the big company “feel small” (provide greater managerial control, break bureaucratic inertia, and break ties to current technology), as well as to more closely fit the needs of divisions and markets. Note that while projects themselves would be decentralized, “back office” functions would remain centralized to achieve economies of scale. While Jager was the main force behind decentralization of R&D, A. J. Lafley, who replaced Jager after his resignation in June 2000, maintained a commitment to it.

The result was a dramatic shift in P&G from 90 percent centralized control of R&D resources in the 1990s to 90 percent decentralized control of R&D in 2008. Prior to the decentralization, P&G was known for creating entirely new product categories: first synthetic detergent (Dreft in 1933), first fluoride toothpaste (Crest in 1955), and, more recently, Febreze odor fresheners (1998), Swiffer (1999), and Crest Whitestrips (2001). (While Crest Whitestrips were introduced after decentralization, all their development took place prior to that time.)

In the words of R&D chief Bruce Brown, making business-unit heads responsible for developing new items inadvertently slowed innovation by more closely tying research spending to immediate profit concerns.4 Relatedly, it led to smaller, more incremental innovation. While the number of innovations doubled, the revenue per innovation decreased 50 percent.5 P&G has failed to introduce a single blockbuster since the decentralization. This is likely because the big blockbusters in the past came from generating new technologies, or leveraging technologies across the business units. Crest Whitestrips, for example, combined bleaching technology from the laundry business, film technology from the food wrap business, and glue technology from the paper business. Once these businesses were decentralized, there was no convenient mechanism for linking technologies in this fashion.

A large part of the decline in P&G’s innovation could be because R&D intensity declined 44 percent following decentralization (from 4.3 percent of sales in 2000 to 2.4 percent of sales in 2011). While a number of other events occurred during that period (such as the Gillette acquisition and the economic downturn), some of this spending decline is likely a direct consequence of decentralization. When business units control their own R&D budgets and are compensated for short-term results, they typically cut R&D to pursue investments with shorter-term payoff. The consequence of cutting R&D at P&G was that the company seemed to have cut meat as well as fat. Its RQ fell from 103 in 1999 to 90 in 2007 (while not obvious because RQ is rescaled to match the IQ scale, this represents over a 50 percent decrease in R&D productivity).

The encouraging news is that P&G’s RQ has since returned to 100. Much of this return can be attributed to efforts to recentralize some of the R&D activity and to better manage the tension between centralization and decentralization. In 2004 P&G initiated efforts to create a new growth factory based on principles from disruptive innovation. The charter of the factory was to generate new growth initiatives of three types: create new product categories (such as Tide Dry Cleaner franchises), bolster existing product lines (such as Crest 3D White), and deliver major new benefits in existing product categories (such as the Gillette Guard, a low-cost, single blade razor created for the Indian market). In addition, P&G revamped its strategy development and review process to integrate company, business, and innovation strategies.6

The theory underpinning centralization versus decentralization of R&D comes from the broader theory of company centralization or decentralization. The tension between the two forms receives considerable attention in the academic literature. The most provocative treatment is Jackson Nickerson and Todd Zenger’s theory that companies vacillate between the two forms to obtain the benefits of both because there is no organization design with the appropriate balance between them.7

The advantages of decentralization resemble those of small companies that we discussed in Chapter 2: improved information processing and better ability to attract and drive performance from high-quality employees. In contrast, the advantages of centralization resemble those of large companies, such as scale economies. However, what’s unique about the centralization/decentralization debate in the R&D context is that centralization provides opportunities to conduct research that spans the organization, is longer term, and is broader in scope. In contrast, decentralization leads to parochial innovation that tends to have a shorter-term perspective.

We’ve seen the forces pushing companies in the direction of decentralized R&D, we’ve heard views on both sides of the debate, and we’ve seen two examples of decentralization leading to lower innovativeness. But what does the broader record tell us? This is a difficult question to answer because there is no readily available data on company decentralization. So we’re going to tackle this question using two approaches to measuring decentralization.

The first approach uses data from a survey of R&D executives that the Industrial Research Institute (IRI) conducted in 1994, and whose results were published in 1995. The degree of R&D centralization in the survey was measured on a five-point scale: 1 = decentralized; 2 = decentralized hybrid; 3 = balanced hybrid; 4 = centralized hybrid; 5 = centralized.

Nick Argyres and Brian Silverman, who were the first scholars to examine the impact of centralization on company innovation, used these IRI data in their analysis. In order to link “decentralization” to company performance, they needed to match the IRI data to publicly available financial data as well as patent data. This reduced the total number of companies they could evaluate in half. Once they had done this matching, they compared a company’s level of centralization to its patent citations. They found that centralized R&D produces innovations that have a larger and broader impact on subsequent technological evolution. Thus their results seem consistent with the experience at P&G.8

Nick and Brian were fundamentally interested in the impact of centralization on the importance of company innovation (how influential the research was in driving follow-on research). I was interested in the related, but separate, question of centralization’s impact on the productivity of innovation (RQ). Accordingly, they were generous in sharing their data with me. The results of my analysis comparing the IRI centralization measure to RQ are presented in Figure 7-1. They are consistent with Nick and Brian’s result as well as the outcomes following decentralization at HRL and P&G. They indicate that companies with centralized R&D have 38 percent higher RQ than companies with decentralized R&D.

FIGURE 7-1. Centralized companies have 38 percent higher RQ than decentralized companies

This first approach to evaluating the impact of centralization on RQ uses a reliable measure of centralization, but it is based on a very small set of companies. So to complement those results, I also examined an additional centralization measure that allows us to look at a broader set of companies. This second measure comes from work by Ashish Arora, Sharon Belenzon, and Luis Rios, all from Duke University.9 The Duke measure computes the level of R&D centralization as the percentage of a company’s patents assigned to the company’s name (as opposed to being assigned to one of the company’s affiliates). A “decentralized company” is one whose value for this measure is in the bottom fifth of the sample of 1,014 companies; a “centralized company” is one whose value is in the top fifth. While the measure is very clever, an important caution is that typically an operating division has the same name as headquarters unless it has been acquired. Thus this measure may be capturing the impact of acquisitions on RQ, rather than the impact of decentralization on RQ.

With this caveat in mind, the results are similar to the prior results for the smaller sample with the better centralization measure. In both cases, the average RQ for centralized companies is substantially higher than that for decentralized companies. In fact, the difference is more dramatic using the patent definition. Centralized companies have 64 percent higher RQ than decentralized companies when using the patent-based measure; centralized companies have only 38 percent higher RQ when we use the survey measure of centralization. This difference in results likely stems from the fact that subsidiaries are typically managed autonomously, thus losing all the benefits of scale and knowledge sharing from the broader company.

The logic underlying the push for decentralization and greater relevance of R&D is that R&D directed by divisions will be more responsive to what the market wants. Accordingly, it is more likely to yield a financial payoff. This is certainly true (as is the fact that the payoff is more quantifiable and less risky—features favored by financial managers). However, the vulnerability in that logic is captured in the Steve Jobs quote, “A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.”10 Thus the first problem with relevance is that its key assumption (that the market offers the best information regarding what R&D to engage in) may be wrong. Indeed, we saw in the last chapter that ideas that come from customers have the lowest value—they yield the lowest level of new company sales. Once we know that customer ideas yield the lowest level of new sales, it is not surprising that decentralizing R&D to be more responsive to customers will also lead to lower RQ.

The more pernicious problem with decentralization, however, is that when R&D is directed by operating units, the company fails to produce the early stage technology that opens up new opportunity. This occurs because operating division managers tend to be evaluated on their divisions’ profitability, rather than the company’s market value (which is the basis for most CEO compensation). The distinction between current profits and market value is important because market value takes into account future profits, so in principle it captures the long-run returns to R&D. In contrast, current profits penalize R&D, because accounting rules require R&D to be expensed. This means all R&D is subtracted from operating income in the year it is expended, while the payoffs of R&D don’t occur until future periods. Thus the further out the fruits of R&D, the less likely operating divisions are to conduct it.

A final problem with decentralizing R&D is that operating divisions have little or no incentive to conduct R&D that benefits multiple divisions, since there typically aren’t mechanisms to share the costs of that R&D in a decentralized system. Relatedly, even if divisions do conduct research that can be utilized by other divisions, without a centralized R&D organization there isn’t (1) a mechanism for knowing which (if any) other divisions can utilize the knowledge, nor (2) a mechanism for diffusing the knowledge even if it’s known that another division can utilize it.

The combined effect of having a nearer-term orientation as well as a more parochial orientation is that decentralized companies conduct less basic research. One implication of conducting less basic research is that companies are less likely to generate inventions that open up new opportunities. An additional implication of conducting less basic research is that it increases the likelihood of a firm outsourcing R&D. We know from the last chapter that conducting R&D internally versus outsourcing has a dramatic impact on RQ.

This shift away from basic research can happen even if there is a central lab, provided the funding for that lab is controlled by divisions. Ultimately the pressure for relevance from the divisions may yield a central lab that is incapable of generating innovations, even when divisions know what the market wants.

A concrete example of this comes from a Fortune 1000 manufacturer of precision mechanical components. In the past, the company had a large R&D budget controlled by a centralized lab that “figured out the right things to do with it”—a charter very similar to Hughes Research Laboratories. Over the past 20 years there has been a 180-degree shift in the orientation of the company’s budget such that the operating divisions drive R&D. At one point after the shift, the central lab proposed developing technology to improve a key dimension of performance across the company’s product lines. The operating divisions determined the technology wasn’t a priority, so development was cancelled. Unfortunately, a few years later, competitors introduced the technology in their products and it killed demand for the company’s own products, forcing it to lower prices. At that point, the operating divisions came back to the lab wanting the technology right away. However, because it had never been funded, it still required two to three years of development. Since the divisions couldn’t afford the lag, the company was forced to outsource the technology.

A number of economic forces in the 1980s and 1990s led to widespread decentralization of R&D. The logic of decentralized R&D is that it makes companies more responsive to the market. The view that this is beneficial is widely held—in an informal survey, approximately 80 percent of consultants and 90 percent of investment professionals believed decentralized R&D is associated with higher RQ. In fact, the opposite is true: companies with centralized R&D have 40 percent to 64 percent higher RQ than companies with decentralized R&D. This occurs because companies with centralized R&D tend to (a) do more basic research, so are more likely to create new technical possibilities, (b) create technology that benefits multiple divisions, and (c) derive more of their technology from internal R&D rather than through outsourcing.