Love came and began flowing like blood, under my skin, in my veins;

pushing my self out of me, it filled me up with the friend.

Now the friend has so gripped all parts of my being,

all that is left to me of myself is my name, the rest is all him.

—POPULAR SUFI QUATRAIN

In Persianate societies during the centuries that concern me, being a Sufi implied that one had come under the spell of love. This is readily evident in the period’s linguistic usage where words meaning lover and beloved are used ubiquitously to designate Sufis in prose and poetry alike. The ultimate object for Sufis’ love was God, after whose beauty poets such as the famous Jalal ad-Din Rumi pined away while lamenting their own shortcomings revealed as a consequence of their passion. By this period the accumulated corpus of Sufi writings in Arabic and Persian contained extensive discussions on the necessity of loving God, who was himself characterized as a being who loved his creation.

1

While Sufi understandings of love for God have been the subject of a number of studies, much less attention has been paid to the fact that medieval Sufis also considered love to be the primary force underlying human beings’ intimate relationships with each other. Hagiographic narratives resound with the rhetoric of love as it pertains to human relationships, providing ample evidence that bonds based on love constituted the bedrock of Sufi communal life in these societies. My discussion in

chapter 4 addresses this lacuna in our understanding by treating the general patterns as well as the social effects of the Sufi discourse on love as witnessed in literature produced during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The material I cover here is complemented by discussions to come in

chapter 5 that complicate the idealized Sufi notion of love by paying attention to gender and the problem of seduction that may lead to non-Sufi ends.

The focus on love feeds into this book’s overall aim of using body-related themes to understand the functioning of Persianate Sufi communities in two ways. First, the question of love is front and center in the original sources, and highlighting stories that invoke the rhetoric of love conveys the overall social atmosphere that comes across when one reads hagiographic literature. Since love is intimately tied to corporeality in this context, uncovering the mechanics of love relationships provides a window into the imagination of the body. The second significance of love connects to the fact that human relationships described in terms of love produce obligations and expectations that are open to manipulation by those involved. The modulation of love relationships is intimately tied not only to affection but also to domination, submission, and control; concentrating on the way such relationships are represented in the sources provides a sense of the way power operated in a social milieu conditioned by Sufi ideas and practices.

The chapter is divided into sections that treat, successively, the bases, distinctive patterns, and social consequences of the medieval Sufi view of love. I begin by mapping out the general properties associated with love as a force and with lovers and beloveds as stock characters in Islamic discourses. This discussion centers on Persian poetic paradigms that acted as models for Sufi social relationships in the period. I argue that although medieval Sufi hagiographers relied heavily on the poetic rhetoric of love, their overall perspective on love saw it as something more than a fictional abstraction manipulated by poets to showcase their ingenuity. While poets’ ultimate aim was to highlight the nuances of characteristics associated with lovers and beloveds, Sufis used the poetic love tale to underscore forces that acted upon Sufis as they were striving to live up to their religious ideals. For Sufis the fiction of love as elaborated upon in Persian poetry acted as a kind of flexible script they utilized to articulate their mutual relationships.

2Hagiographies narrating the full life stories of major Sufis work through a cycle of love that I have divided into three phases. Persianate Sufis destined to achieve great spiritual and social status are most often shown to begin their paths in earnest when they fall in love with masters. Descriptions of these events rely heavily on the language of “love at first sight,” and, in a number of cases, the development of a relationship with a master goes hand in hand with coming of age and leaving the natal home. The middle periods of Sufis’ lives, when they are on the path but have not reached perfection, show them tormented by their passion for masters. Sufis in this phase of the love cycle actively seek to transcend their bodies and minds in order to unite with masters and, through them, God. Stories concerned with this phase show masters and disciples acting upon each others’ bodies in dramatic ways to exemplify uncontrollable passion and unexplained domination. The hagiographic love cycle ends when students become masters in their own right, attaining the aim of the most promising disciples. Fulfillment of this destiny is indicated in stories where the bodies of masters and disciples become indistinguishable from each other. This transmutation of bodies is the ultimate symbolic representation of the social mechanism through which groups of Sufis linked to each other through love might be understood as a single “social” body. Echoing themes discussed in

chapter 3, this social body was both spread across space in the form of a community devoted to a specific religious path (

tariqa) and continued beyond individual lifetimes through a Sufi intergenerational chain (

silsila). The end of the chapter presents a work that argues that corporeal attraction is a necessity for falling in love and progressing along the Sufi path.

Stories of love that I retell in this chapter underscore the intensity of personal bonds between Sufis that ultimately guaranteed the cohesiveness of Sufi communities in the Persianate context. The primacy of corporeal exchanges in these stories indicates that the authors who produced them perceived the body as the primary locus of a person’s self, which had to be deployed strategically before other bodies for the sake of spiritual as well as social goals. To excel in the Sufi milieu in this period, a person had to be able to become the subject as well as the object of love. That is, Sufis who climbed all the way up the ladder of spiritual hierarchy to be regarded as friends of God did so by forming relationships with other Sufis in which they sometimes acted as lovers and at other times as beloveds. This interchangeability of Sufi masters’ functions within the context of love constituted one of the primary means through which they acted as powerful social mediators in the Persianate context.

THE PARAMETERS OF LOVE

Love in medieval Islamic literatures is considered a force known through its causes and effects. It is provoked by beauty, the hallmark of the beloved, which has a radically transformative effect on the lover. In lyric poetry the discussion of love takes place through the poet’s play on a number of stock characters, metaphors, and scenarios with which the reader is presumed to be familiar. Chief among the characters are love personified as an active agent, the lover, and the beloved, each of them invoked through well-known properties. Poets usually write in the voice of lovers, who ruminate on their own state and its cause, the force of love unleashed by the beloved’s beauty. Poets’ ingenuity lies in their ability to manipulate the established vocabulary of love with the aim of saying something familiar in a new way or highlighting a nuance hidden away within hackneyed metaphors.

3 The essential framework of this poetic vocabulary of love can be summarized through a couple of representative examples from the Persianate context.

4In his narrative poem Sifat al-ʿashiqin (The Qualities of Lovers), Hilali Jaghataʾi (d. 1529) uses direct exhortation as well as aphoristic stories to highlight love’s status as the preeminent human emotion. After customary praises of God, Muhammad, and the art of poetry, he begins his discussion of love in earnest with the following eulogy:

The world is but a drop in the ocean of love,

heaven is but a plant in the desert of love.

There is no station higher than that of love,

its foundations are devoid of any flaw.

No vocation is better than the work of love,

no preoccupation greater than the madness of love.

One who is captive to love does not want release,

even when dying from sorrow, happiness is not what he seeks.

Worldly losses and gains are equally meaningless,

all that is there in the world is love, nothing else.

Although love would throw up everything in turmoil,

all liveliness in the world stems from its sorrow and pain.

No wilting ever comes to mar the spring of love,

passion’s wine never relinquishes its headiness.

Heart, throw yourself on the candle like a moth!

Become branded with its love mark, and burn!

Be the beggar of love, who nonetheless is the assembly’s king!

Go, be the sultan of your own times!

When love comes, do not be sad, sit happy;

feel yourself liberated from the world’s sorrows.

5

Given the significance of love as described here, to be in love is a highly desirable state. The fact that love brings turmoil and pain to one’s life is deemed inevitable, but those who fall in love are urged to take the long view of the situation since they have, by virtue of being smitten, entered the most worthwhile arena of human experience. What is most significant about love is that it stirs up human beings in a way more potent than any other force that can act upon their bodies and minds.

6As already mentioned, poets usually write in the lover’s voice and portray themselves as victims of the beloved’s beauty. Their descriptions of the state of being in love decry the fact that they have fallen in love involuntarily, though, if the love is true, nothing in the world is able to pry them off from the beloved. While most words and actions described in poetry belong to lovers, beloveds are shown as the powerful party in the affair because their sheer presence grips the lovers’ mental states at all times. The following ghazal by Shah Qasim-i Anvar captures the contrast between the lover and the beloved as seen in this paradigm:

Of your beauty and comeliness, what can be said?

A cypress tree, an idol, tuliplike cheeks—what can be said?

You have etched sorrows and happiness on my heart’s page.

For what reason you have done so, my heart and life, what can be said?

We count ourselves among the dogs of your alley.

If you refuse to deem us one of them, what can be said?

Your sorrows we carry in our heart, day and night.

If none of ours finds a place in your heart, what can be said?

What is to be done with me: a heart-giver, a madman, a profligate!

Of your being a beautiful, heart-ravishing trickster, what can be said?

Upon remembering you my heart blooms like a fresh rose.

Of the qualities of such a spring wind, what can be said?

Friend, see, his work is to melt the heart of poor Qasim.

As to what may be the purpose of all this, what can be said?

7

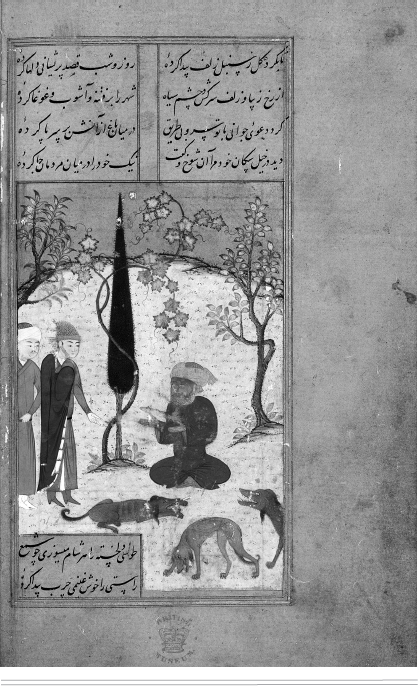

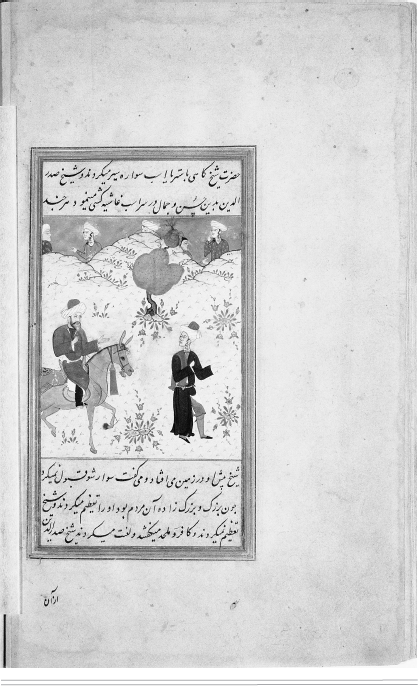

This ghazal contains common poetic themes, like the comparison between the beloved’s form and the cypress tree, the company of dogs, the beloved’s dismissive demeanor. These are also reflected directly in paintings, such as

figure 4.1, which accompanies an anthology of poetry produced in Shirvan in 1468. The refrain “what can be said” (

cheh tavan guft) in this poem is emblematic of the position of the poets/lovers, who feel unable to convey the full impact of the presence of the beloved upon themselves but are nevertheless compelled to speak of it endlessly. Beloveds are described in the form of entrancing pictures whose vision tethers lovers to them forever upon first sight. The greater a lover’s attraction to the beloved, the less he becomes bound by the mores of ordinary society. Although caught helplessly in this way, lovers are also marked by bewilderment as exemplified in the last verse of this poem: the initial attraction and the relationship’s eventual destiny are ultimately beyond rationality, so that there is no way for lovers to extract themselves from the situation by reasoning through it.

8The contrast of opposites between the lover and the beloved can be extended much further than what is given in this ghazal. Typically, lovers are active seekers while beloveds attempt to evade lovers’ attentions, lovers give voice to their longing in poetry while beloveds are usually silent, lovers’ bodies whither away due to self-neglect while beloveds are pictures of beauty and rude health, lovers are marked by frustration while beloveds are shown to be self-satisfied, and lovers are always in earnest while beloveds are playful and trivialize the attention directed at them. These differences between the two parties produce a constant tension that lies at the heart of the premodern Islamic rhetoric of love. The love relationship continues as long as this tension is unresolved; without it, love either dies or is consummated in a full union that leaves little to talk about. Classical Persian poets, masters of the rhetoric of love, play upon this tension to bring out the nuances of love relationships.

4.1 An ardent lover and a dismissive beloved from an anthology of poems by various authors. Shirvan, 1468. Opaque watercolor. Copyright © British Library Board. MS. Add. 16561 fol. 85b.

As in poetry, hagiographic narratives depict most connections between Sufis in the form of dyadic relationships between masters and disciples who have different roles and expectations assigned to them. In parallel with the discourse on etiquette discussed in

chapter 3, these relationships mimic the kind of differentiation between the lover and the beloved described in poetry, which the hagiographers cite very frequently to make the point. However, poetry in its own context is different from Sufis’ use of poetry: in hagiography the overarching framework for Sufis’ interrelationships derives from Sufi socioreligious imperatives rather than poetic conventions. In poetry read without reference to a particular poet’s intentions within his context, the beloved is eternally beautiful, the true lover always hopelessly infatuated. Sufis progressing through their lives in hagiography are shown to occupy the positions of both lovers and beloveds at various points depending on periods of life and specific situations.

The mutability of Sufis’ position in the discourse of love is most clearly visible in extended hagiographies that narrate the whole life spans of particular masters. As young disciples, gifted Sufis find themselves in the position of lovers whose Sufi journeys begin when they become infatuated with older masters. As they become more mature, however, they increasingly come to occupy the position of their masters’ and others’ beloveds because of their future function as subsequent links in intergenerational chains of Sufi authority. This transformation has corporeal markers, as evident in the following anecdote about Qasim-i Anvar:

They say that in the end of his days, Amir Sayyid Qasim lived a life of comfort and had become fat, ruddy, and fair. An elder [once] asked him: “what is the mark of a true lover?” The sayyid replied, “decrepitude and sallow skin.” The man said, “but you look much different than this!” He replied, “Brother, there was a time when I was a lover, but now I am a beloved.” Then he recited the following verse from the Masnavi:

While a beggar, I lived in that pit of a house.

Then I became a king, and every king has to have a palace.

9

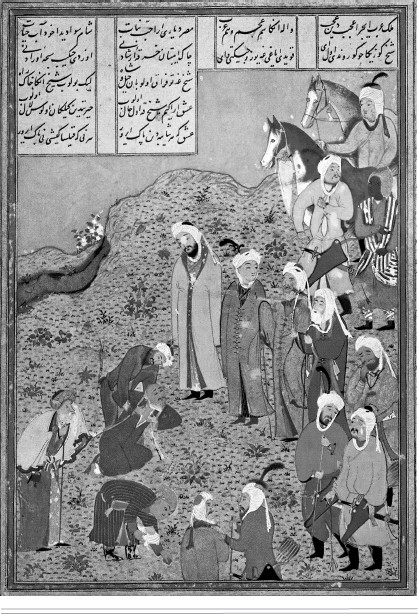

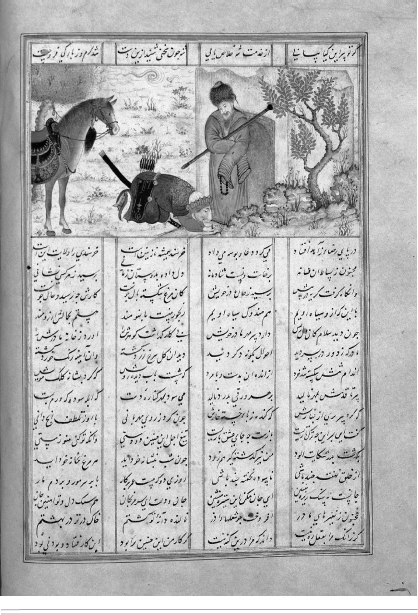

4.2 Shaykh ʿIraqi bidding farewell to a beloved friend. From a copy of Mir ʿAli Shir Navaʾi’s Hayrat al-abrar. 1495. 14 × 10 cm. Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. MS. Elliott 287, fol. 34a.

The contrast between bodies represented in this report is also depicted in miniature paintings of the period, such as the scene showing an older and disheveled Shaykh Fakhr ad-Din

ʿIraqi (d. 1289) consumed by grief upon taking leave of a young beloved companion who looks upon the scene with considerable equanimity.

10In hagiographic narratives great Sufi shaykhs come across as masters of love because they know when to be beloveds and when to be lovers. While a great poet manipulates the vocabulary of love to make new meanings out of familiar tropes, Sufi masters use the same rhetoric to modulate social relationships between human beings in which love acts as a catalyst for change and development. Sufi masters’ efficacy as spiritual guides derives from their ability to manipulate the tension induced by love for the sake of the larger purpose of leading the disciple on the Sufi path. Interhuman love in the Sufi context does not pigeonhole particular individuals into defined characters with consistent expectations. Instead, the discourse of love helps steer the course of close relationships that shift continually depending on situations and the passage of time. The full significance of this social use of the rhetoric of love will become clear through the hagiographic cycle of love traversed in the following pages.

FIRST MEETINGS

As in poetry, the starting points of Sufi love are first meetings between two individuals who become tied to each other in a hierarchical relationship. A number of hagiographic narratives depict these meetings in considerable detail, employing many tropes of love familiar from poetry. Unlike the usual situation in poetry, however, the identities of the lover and the beloved are reversible in these stories. On the surface of the texts, disciples are identified as lovers who fall in love with masters after being told of them or upon meeting them. In the larger contexts of the stories, however, masters are shown to transform themselves for the sake of becoming objects of love for worthy disciples. Since it is the masters’ desire that drives the narratives, the subtext of the stories marks them as lovers who utilize their powers to attract young beloveds. This cross-cutting dynamic is reminiscent of Sufi discussions of human beings’ love for God: while developing unconditional love for the divine is an imperative for Sufi novices, God is himself acknowledged as a lover of his creation.

Safi ad-Din Ardabili and Zahid Gilani

One of the most elaborate accounts of the first meeting between a Sufi master and a disciple occurs in the hagiography of Safi ad-Din Ardabili. Although a widely influential Sufi master in his own times, Safi ad-Din is best known in history as the progenitor of a line of genealogical successors who turned the Sufi lineage into the Safavid dynasty of Iran in the early sixteenth century.

11 He is the subject of one of the longest surviving medieval Persianate hagiographies dedicated to a single master,

Safvat as-safaʾ (

The Essence of Purity) by Tavakkul b. Isma

ʿil Ibn Bazzaz Ardabili (d. 1371). This work has a complicated history in that portions of it were modified on the orders of the Safavid king Shah Tahmasp (d. 1576) to make Shaykh Safi’s genealogy fit better with Safavid dynastic claims. Changes to the text are, however, not difficult to identify based on both variation in manuscripts and the blatant political intent of the later additions. Moreover, stories from Shaykh Safi’s early years that concern us here were of little interest in the political realm and can be presumed to go back to the narrative completed approximately in 1358.

12Ibn Bazzaz Ardabili relates that Shaykh Safi was born in a village near Ardabil, Azerbaijan, the fifth child in a family with seven children. His father passed away when he was six so that his mother was his main caretaker as a child.

13 He was naturally inclined to religious pursuits from the beginning and had a number of experiences as a child that made him aware of future events. When his special qualities became apparent to his mother, to benefit from his charisma, she began to break her fasts by drinking the used water left over from his ablutions before prayers. He was uncomfortable with this and tried to dissuade her, but she was able to persist for twelve years, sometimes acquiring the water stealthily when he thought that it had been poured on the ground.

14 As Safi ad-Din grew mature, he realized that he needed a Sufi master to guide his instincts, but his mother was unable to part with him, and he could not begin his search. He eventually persuaded her to let him go through a ruse. Two of his older brothers, traders, had gone toward Shiraz; the eldest died there while the second married a woman there and had settled down. He asked his mother’s permission to seek this brother, and she finally agreed because of her continuing sorrow over the death of her oldest child and her desire to see the second son, from whom not much had been heard for a while.

15Unknown to him at this stage, Safi ad-Din’s separation from his mother through this journey was the beginning of his attachment to his eventual mentor, Shaykh Ibrahim Zahid Gilani (d. 1301). While staying with his brother in Shiraz, Safi became well known to local Sufis who were impressed by his innate religious aptitude and told him that only one person, a certain Amir

ʿAbdallah, was capable of guiding him. When he went to this man and told him his condition, he said that Safi was already more advanced than him and that the only person in the world who could guide him was Shaykh Zahid Gilani. Upon further questioning, Amir

ʿAbdallah described the exact location and physical setup of Shaykh Zahid’s hospice in Gilan along with the following detailed physical profile: “He is a short man with a bright complexion, a black mark near his mouth, black eyes, flat brow with receding hairline, and a sparse but wide beard.”

16 Shaykh Safi returned from Shiraz to Azerbaijan some time after this encounter and spent four years thinking about and visualizing Shaykh Zahid. No one mentioned the shaykh to him during this period, but his great ardor was known to Zahid himself in Gilan who would tell his disciples that “a young man in Ardabil who wears felt is confounded with desire for us; if he were to come here, his affair would be taken care of in a single day.”

17Safi had given up normal life after his return from Shiraz and his four years of waiting to meet the guide were spent mostly in religious pursuits. The matter eventually came to a head through the intermediacy of a native of Safi’s village named Muhammad Ibrahiman who went to Gilan on a trip to buy rice. After his business transaction, he visited one of Shaykh Zahid’s two homes, which was nearby, and was so impressed by him and his followers that he took an oath of repentance on his hands and donned clothes marking his affiliation with this community. He then started on the road home but ran into trouble because of a snowstorm that left him and his entourage stranded near his village. A group from the village, which included Safi, set out to help him, and, when they met, the future master noticed immediately that Ibrahiman had changed his clothes and outer form. When questioned, he told Safi that he had become Zahid’s disciple and then described the shaykh’s outer form minutely in words that matched exactly what Amir ʿAbdallah had told Safi earlier in Shiraz. Upon hearing this, Safi was completely beside himself and immediately got on the road to Shaykh Zahid despite his companions’ warnings about the weather.

Ibn Bazzaz Ardabili writes that Shaykh Safi had a wet dream every night during the journey to Gilan, which caused significant hardship in the winter because he was then required to perform a full bath in the morning in order to pray. Every night after the event, Shaykh Zahid appeared to him wearing a green woolen coat and asked an accompanying servant to give Safi warm water to perform the bath. He used the water but was uncertain in the morning whether a “visionary” bath truly satisfied the legal requirement. To be safe, every morning he also took a real bath, although he had to use cold water because he was reticent to trouble people to warm it for him. But bathing in extreme cold with freezing water caused him to develop severe fatigue in all his outward senses. This led to a gradual diminishing of his hearing, sight, and sense of smell, so that “he trod on the path of love while trampling the world of sense objects under his feet.”

18 The minimizing of the senses represents Safi ad-Din’s gradual dying to the material world that becomes available to consciousness through sensory contacts.

Safi ad-Din eventually reached Shaykh Zahid’s place during the month of Ramadan when it was the shaykh’s habit to remain in seclusion, neither listening to disciples’ experiences nor interpreting their stations or providing guidance. Safi entered the hospice and went to one corner to pray. Shaykh Zahid, who had been aware of his travels through mystical intuition, then asked the hospice’s attendant to light a fire, even though the building was already warm. The heat of the fire slowly penetrated Safi’s body as he stood praying so that, eventually, sweat began to pour from his nose, ears, and the pupils of his eyes. The three senses associated with these organs were then fully restored, and Shaykh Zahid asked an attendant to bring Safi to him. He kissed Zahid’s hands and feet when he saw him, finding him exactly as the image he had carried in his mind for over four years. Shaykh Zahid then asked him why he had come, and he replied, “to repent,” referring to the first step on the Sufi path, undertaken when someone becomes attached to a master. He then asked him if he had parents, and when he replied that he had only a mother, Zahid told him, simply, “welcome.” Then, contrary to his custom during Ramadan, he called all his disciples to come together and told them that this was the man from Ardabil who had been seeking him for four years and that “there was only one veil left between him and God, and even that has now lifted.”

19 Zahid then gave Safi his own clothes to wear and installed him in a special place of seclusion where normally only he himself performed Sufi exercises. From that point on, Safi became a permanent fixture at Shaykh Zahid’s side, gaining from his guidance and, eventually, becoming his most prized disciple and successor.

Ibn Bazzaz’s rendering of the young Safi ad-Din Ardabili’s journey toward Shaykh Zahid is peppered with citations of Persian and Arabic verses that correlate the different phases of his progress to themes in the idealized love tale elaborated upon by poets. The story begins with Safi’s desire for an attachment, which leads to his hearing about the remarkable master who lives far away and is the sole person in the world deserving of his love and devotion. The first informant takes care to describe Zahid’s face and body in detail, and the image becomes imprinted on Safi’s mind to act as the unceasing reminder of the beloved for a long period. His desire spills over the boundaries of rationality when the second informant confirms the correspondence between the real person and his mental image, and he begins the actual journey to the master heedless of practical difficulties. The path to the beloved is arduous and painful, but here too the beloved appears in visions that provide relief and keep him on the path. The deprivations of the journey are designed to empty his body of its existing content: he loses lust, as in the image of recurring wet dreams, and his other senses are reduced to a minimum because of the cold.

This is all reversed when he reaches the master and, in effect, acquires a new body. His senses come back to life from the heat of the beloved’s home, and he acquires a new outward skin in the form of Shaykh Zahid’s own clothes, which he puts on. While there is much left to happen in the relationship between the two in subsequent years, a sense of what is to come can be had from Zahid’s statement that now there is no veil left between Safi and God. The implication here is that Safi fused with Zahid’s body, which already had unrestricted access to God because of his spiritual attainments. The union of the earthly lover and beloved, the Sufi disciple and master, thus presages the fulfillment of ultimate love that lies at the end of the Sufi path.

As we see it enacted in this narrative, Shaykh Safi’s extraordinary potential as a Sufi is fulfilled when he seeks and finds a master worthy of his desire. It is noteworthy that his attachment to Shaykh Zahid matures as he becomes increasingly distant from his mother, his initial caretaker in the hagiography. First, he hears of the master when he is away from the mother, after having concocted a ruse; second, his mother disappears from the narrative when he returns to Ardabil and remains obsessed with the master’s image for four years; third, at the moment of union with the master, the latter pointedly asks him about his parents. Shaykh Zahid’s saying “welcome” to him after hearing that his mother is alive marks a kind of change of guards in the text where the master takes on the mother’s caring and loving functions. The transition is in fact not just of caretakers but of modes of love altogether. Shaykh Safi’s connection to his mother is based on filial love, since he is a product of her body and has been nurtured by her. His affiliation with Shaykh Zahid, in contrast, is established through the kind of sensual love celebrated in poetry. The connection between Safi and Zahid is, in the long run, a link in the chain of Sufi spiritual authority that mimics an actual genealogy. Many of the functions of the two types of love are shared, but their material basis with respect to the body is different.

Khwaja Ahrar and Yaʿqub Charkhi

Khwaja Ahrar is a towering personality in the history of Sufism during the fifteenth century, and I have already discussed his early years in search of a master in the previous chapter while commenting on competition between major masters in Herat in the early decades of the fifteenth century. To pick up the story from there, after spending quite a bit of time in Herat, Ahrar came to the Naqshbandi path through his encounter with Naqshband’s student Yaʿqub Charkhi. The story of his first meeting with Charkhi depicts, once again, a lover coming to the doorstep of a beloved in a stylized narrative reflecting poetic paradigms.

The meeting is described quite similarly in three lengthy hagiographies dedicated to Khwaja Ahrar’s life.

20 The narratives from Ahrar relate that he initially came across Ya

ʿqub’s name in the village of Chihildukhtaran just outside Herat on his very first visit to the city. He saw a man sitting in the doorway of a Sufi hospice in the village and thought that he was doing the Khwajagani silent zikr. He asked him where he had learned this and was told, from Mawlana Ya

ʿqub in Halghatu who was a direct disciple of Naqshband. Ahrar was impressed by what this man said of Ya

ʿqub’s qualities but decided to proceed on his way to Herat where he spent four years in the company of various Sufi masters. After this delay he finally made his way toward Halghatu, to meet the shaykh as part of his quest for Sufi guidance in this early period of his life.

21 Just before reaching his destination, he developed a fever from the winter weather and had to spend twenty days in a village where some residents spoke ill of the shaykh. His enthusiasm for meeting the shaykh waned somewhat when he heard this, but he eventually decided to go ahead with the plan since he had already come all this way. The shaykh greeted him warmly the first day, but the next day he was angry and behaved harshly. Ahrar realized that he had become aware of the hesitation that had affected him just before his arrival and had been displeased by this. However, the next day Ya

ʿqub was again very kind and related the story of his own first meeting with Naqshband in which the master had accepted him as a disciple only after he had received an indication from the unseen world.

After recalling this crucial moment, which established his own place in the Naqshbandi chain, Ya

ʿqub extended his hand toward Ahrar and invited him to take an oath of affiliation. But, at that very moment, Ahrar saw a white mark on Ya

ʿqub’s forehead, which seemed to be a disease and produced in Ahrar a feeling of repulsion. Ya

ʿqub sensed Ahrar’s disinclination and quickly took away his hand, but he then transformed his appearance immediately, almost as if he were changing his clothes. He appeared in such a form that Ahrar felt drawn to him compulsively and, just when he was about to uncontrollably fling himself on the shaykh, Ya

ʿqub again extended his hand and said that Naqshband had grasped his hand and had said that whoever grasps it in the future grasps my hand. Ahrar then took the hand with all willingness and became a part of the Naqshbandi chain.

22It is striking that, in this story, Ahrar’s initial revulsion and eventual attraction to Yaʿqub occur on a corporeal basis. As with Shaykh Safi, Ahrar also discovers the prospect of discipleship with the master by hearing of him from someone, although, in this case, he is first drawn to the possibility by seeing someone do zikr instead of receiving an image to carry in his mind. Just prior to reaching the master, he suffers from an illness that partially incapacitates the body, a theme that is reflected in stories about Shaykh Safi as well. In the end Yaʿqub’s body in its actual physical presence is the ultimate mediator of Ahrar’s incorporation into the Sufi community. Yaʿqub’s competence as a master lies in his ability to sense Ahrar’s hesitation and then change his form to make himself compulsively attractive. His statement at the end of the story signifies the idea that his body is a channel for the presence of Naqshband so that by taking the hand Ahrar was coming into bodily contact with his eminent predecessor. The oath incorporating Ahrar into the Sufi chain is then undertaken based on unbroken bodily contact between masters and disciples spanning generations. Ahrar’s life’s work from this point onward was to propagate the path so that, like Yaʿqub before him, his body becomes a vehicle for the manifestation of the teachings and powers of the illustrious ancestors.

Ahrar’s first meeting with the master presents a complicated picture regarding who among the two is the seeking lover and who the sought after beloved. In the straightforward reading of the story, Ahrar is the one who makes the journey to the master’s hospice after nursing the possibility of the meeting in his mind for four years. But, in the end, it is the master who changes his form to make sure that he falls in love with him. The consummation of the story is thus driven by the master’s desire to attract Ahrar. Ahrar seems to have taken this aspect of the master’s role for granted in later life; a work devoted to him relates in his own words that, whenever he wanted to establish a relationship with another Sufi, he would put on the “dress of external form” (

kisvat-i vujud) of a beloved so that the other party was forced to fall in love with him.

23 Once this occurred, the disciple would become beholden to him in the way a lover is helplessly attached to a beloved, which allowed him to direct the disciple on the Sufi path. In Ahrar’s words, the disciple must fall in love with the master corporeally because “the master’s form (

surat) contains his reality (

haqiqat), which, in turn, includes the totality [of existence] (

jamʿiyyat). The path to God is preceded by the disciple becoming affected by the totality through his concentration on the master’s form.”

24The principle at work here is reflected in a work dedicated to Ahrar’s antecedent Baha

ʾ ad-Din Naqshband as well. One day he asked his disciples whether it was they who had found him or vice versa. When they responded that they had been the seekers, he suddenly disappeared from view and later reappeared to prove that their capacity to find him depended, in the first place, on his power to make himself available and apparent.

25 Similarly, Ni

ʿmatullah Vali is credited with the verse “To every friend that I see worthy of love / I show my beauty and seize his heart.”

26 In the underlying ideological bases of hagiographic narratives, the interchangeability of masters and disciples as lovers and beloveds was a crucial prerequisite for the production of Sufi chains of religious authority whose significance goes beyond the depictions of first meetings.

THE CONSEQUENCES OF FALLING IN LOVE

Hagiographies written in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries consist largely of vignettes in which great masters interact with disciples on a one-to-one basis. Since the narratives mostly show two individuals in action, it is easy to read the characteristics associated with poetic lovers and beloveds in almost all interactions among Sufis described in these texts. The power of the poetic love paradigm for the fashioning of social relationships and their literary representation is evident from the near total presence of this pattern throughout Persianate hagiography. In this section of the chapter, I concentrate on dramatic instances of corporeal interactions between Sufis who are already in master-disciple relationships. The general tenor of relationships considered here follows from what I have described already, although the kind of imagery employed in these instances provides greater texture to representations of the maintenance of love in Sufi dyads that aggregated to form powerful Sufi communities.

Love’s Grip on the Heart

Some of the most dramatic stories I have encountered that show masters’ control over disciples’ bodies following the establishment of their relationship of love are found in

ʿAli b. Mahmud Abivardi Kurani’s

Rawzat as-salikin (

The Garden of Travelers), written around 1505.

27 This work repeats some material from earlier sources, but most of the detailed stories are told in the words of Sufis whom the author met personally during the second half of the fifteenth century. The descriptions are particularly striking for their ability to convey the fact that being in love is simultaneously an exhilarating and an imprisoning emotion.

Although the

Rawzat as-salikin purports in the beginning to be a history of the Naqshbandi chain, the vast majority of its stories are concerned with the life of the author’s own master, the Naqshbandi shaykh

ʿAla

ʾ ad-Din Muhammad b. Muhammad b. Mu

ʾmin Abizi (d. 1487).

28 Kurani reports that when Abizi became a disciple of Sa

ʿd ad-Din Kashghari (d. 1456) in Herat after traveling to the city from his native Quhistan, the master’s first instruction to him was to discontinue all his studies to concentrate solely on duties assigned by him. Abizi stopped all his quests except his study of hadith, which he was pursuing at the time under another teacher who lived outside a gate to the city. When it came time for the lesson, he went on his way to the teacher but was faced with an extraordinary circumstance when he reached the gate. As soon as he put one foot outside the city wall, iron shackles appeared on his feet out of nowhere, impeding his speed and rattling as he took further steps. Then with each new step, parts of his attire began flying off his body. He first lost his turban, then his outer clothes and his undershirt, then even his shoes. Just when all that was left was his underwear, he decided to stop in order to save himself from the disgrace of being completely naked in public. He then turned back and each piece of his attire returned to his body at the exact same step at which it had been removed. Finally, the shackles disappeared as soon as he put his feet inside the city gate. Perceiving this experience to have been related to his new religious affiliation, he decided to go and see the master. When he went to the mosque where Kashghari usually stayed, he found the master sitting alone in meditation. As he entered, the master raised his head to gaze at him briefly and then dropped it again to concentrate on his meditation. Abizi understood this momentary acknowledgment to be a warning that made clear the meaning of his earlier experience: he was to obey the master completely after having begun his relationship with him or he would face severe consequences.

29While in this story Abizi found himself in the position of being a lover imprisoned by the beloved’s desires, most tales in this hagiography portray the later years of his life when he was himself a master and a beloved. In one evocative account the author reports from a “lover” (muhibb) that one day as he sat at home he was suddenly overcome with the desire to see Abizi and immediately got on the road. On the way he felt as if he were simultaneously being pulled by a rope around his neck and prodded by a stick at his back to get to the master as soon as possible. Walking very quickly, and even running at certain points, he arrived at his destination to see the master sitting in the middle of a room. Confused and surprised, he sat down in front of him and, imitating him, put his head down on his chest. He then thought that it would be better to raise his head and perform a few rounds of zikr before sitting like this. But, however much he tried, he could not lift his head and became frightened that perhaps it had become stuck in this position.

Immersed in his panic, he then saw that the shaykh’s chest opened up and a wrist and fist appeared from it that had strings attached to it. The fist began traveling toward him while he could observe that folds of the strings attached to it were sitting within the shaykh’s chest. At this moment, he reminded himself that this was not a vision; rather, he was observing what was happening with his normal eyesight. The fist appeared in front of his own chest, which had also opened up in the meantime, and went inside to expand into a palm that grabbed his heart. He then felt a tremendous pain in his chest and when he looked down, he saw that the fist was squeezing his heart tightly so that parts of it were protruding from between the fingers in the way dough squelches out of the hand in the process of kneading. The fist then returned to the shaykh’s heart, leaving him bewildered and impressed with the powers of this master. He looked toward the shaykh and saw him staring at him with great intensity and heard him recite the following quatrain:

When the command of my gaze falls in your direction,

do not think that I have chosen myself for this job.

In my face is to be seen God’s beauty,

I reckon God’s perfection in the copy that is my being.

30

As reflected in these verses, Abizi’s divinely ascribed beauty and perfection compel the disciple to be present in front of him. The organ reaching out from his chest that captures the disciple’s heart represents the beloved’s power over the lover in a most literal and graphic manner.

31The master’s total control over disciples is reflected in stories from the life of Baha

ʾ ad-Din Naqshband as well. At one point he told one of his disciples that he had such power that, if he wanted, a slight movement of his sleeve could compel all the people of Bukhara to leave their preoccupations and follow him. Just as he said this, he pulled his hand inside his sleeve and the disciple noticed the movement. He immediately lost consciousness and, upon returning to his senses, felt that love for the master had completely overpowered his heart forever.

32The stories I have highlighted so far show the painful or restrictive side of love as it pertains to the position of the Sufi disciple as a lover. Even here it is possible to see that disciples put up with the pain of love for the ultimate pleasure of the master’s company and, through them, proximity to God. Their situation is seen as being preordained for the human condition as stated in the following verse reported in a work dedicated to ʿAli Hamadani:

Celestial beings have love, but not pain;

in creation, the human is the only being joined to pain.

33

In hagiographic narratives, disciples are caught in the web of love and pain, but their persistence in continuing with the existing scheme of things is essentially voluntary and stems from both the actual pleasure of the company of the charismatic masters and the ultimate religious award. Kurani reports that Abizi related from one of his own masters that a true lover is like a person standing on a high mountain, who dives when called to do so by the beloved even when he knows that the valley below is like a forest of sharp nails pointed upward. It is only when a lover shows this much devotion and selflessness that the beloved catches him before he reaches the ground and saves him.

34 The same message is reflected in Naqshband’s advice to his disciple Shaykh Amir Husayn: as long as his desire was that he was with him as the beloved, he would find him in his company as a protector no matter where he went.

35

Masters as Lovers and Beloveds

Stories from the saintly lives of the great masters that I have related in this section underscore the restrictions impinging on a disciple who becomes the lover to a master and is bound by the master’s desires. But, as I remarked earlier, the subtexts of hagiographic narratives indicate that Sufi masters deliberately made themselves “beautiful” in order to attract disciples who would fall in love with them. By this token, the masters ultimately occupy the positions of lovers in search of young Sufis who would become attached to them and, in time, continue their chain of initiation.

ʿAli Hamadani’s views as they are reported in the

Khulasat al-manaqib give this aspect of the master’s self-understanding concrete form. He is supposed to have said that Sufis who reach the stage of being the pole (

qutb) of the Sufi hierarchy embedded in the world are simultaneously lovers and beloveds. If they appear to be beloveds, they are so externally, while their interior aspects have the properties of lovers; and if they show themselves to be lovers outwardly then they are beloveds on the inside.

36 The form they take in the exterior world (

zahir) is significant in that it corresponds to how they relate to other human beings. Those who are outwardly beloveds attract others and become responsible for teaching the path. They are given total power over their followers and will not face any questions on the day of judgment even if they kill a thousand persons every day. In contrast, those who are outwardly lovers are interested solely in their own salvation; they must observe all rules of conduct and will have to answer for any infractions they might commit in the accounting of good and bad deeds after death.

37

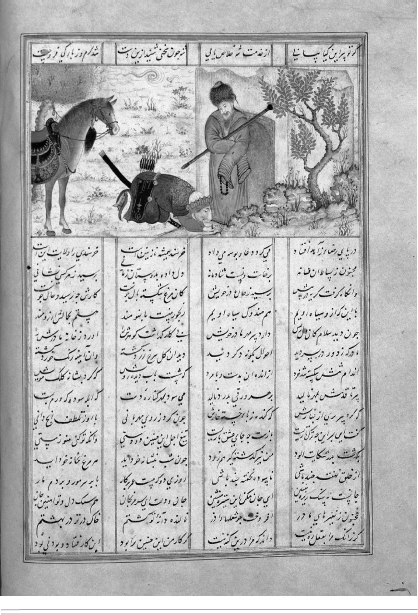

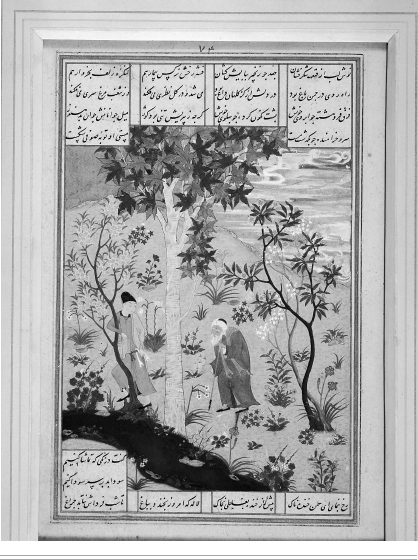

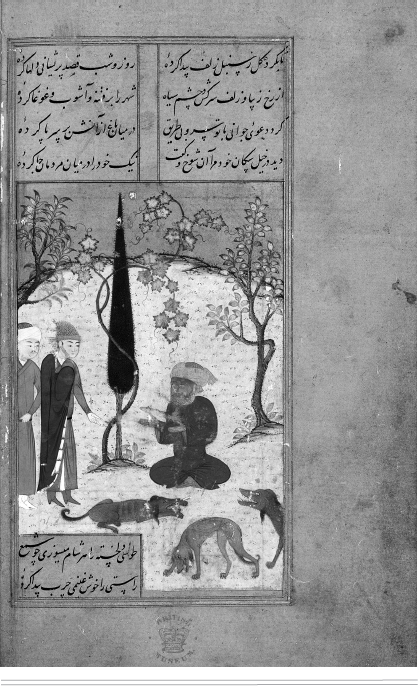

Although Hamadani’s distinction here mentions two types of Sufis, being a lover or beloved on the outside could also be seen to refer to phases in the life of a given Sufi. At the beginning of the path, the Sufi is a lover of a master on the outside, although in the interior it is the master who has chosen him as the beloved. Later, for those who climb the spiritual hierarchy and become teachers in their own right, the situation reverses. They then become beloveds on the outside while being the lovers of their disciples on the inside. The interchangeability of roles is reflected in miniature paintings’ depictions of Sufis from the period as well, where we find examples of compositions showing masters as beloveds and disciples as lovers and vice versa (

figs. 4.3 and

4.4). The first image, dated circa 1470, shows a king bowing in front of a dervish after realizing that he represented a higher station despite living in the wild and being unsure of his subsistence on a daily basis.

38 Conversely, the second image, dated to 1485, shows a young man being pursued by an old Sufi in a scene of dazzling natural beauty.

39 Poetic rhetoric, hagiographic stories, and representations in paintings combine to present extensive evidence for the salience of this pattern in the Persianate environment.

Whether acting as beloveds or as lovers, the great Sufi masters come across in hagiographic narratives as controllers of the power of love. Their efficacy as religious adepts lies in the ability to change their form to keep alive the tension of love in order to drive disciples along the Sufi path. When a disciple is flagging, they appear as awesome beloveds who compel the disciple as lover to become more steadfast. And when the disciple is wrongly infatuated, they distance themselves as a kind of lesson until the correct balance is reached. During both processes they act as beloveds outwardly while inwardly seeking the disciple’s allegiance and betterment as lovers.

40 The Sufi master’s persona as it pertains to the discourse of love contrasts interestingly with the poetic paradigm of love. There the beloved is corporeally powerful because her or his beauty entrances and enslaves the lover. However, the power of words in poetry belongs to lovers. In the Sufi context, as I have shown, the mutability of lovers and beloveds places both power in the hands and tongues of the masters within narrative representations. However, it should be recalled that it was the disciples, and not the masters who are shown speaking, who produced these texts. Mutability of roles is, therefore, an inherent part of this whole discourse. The masters’ excellence in this role is measured by what the disciples attribute to them in terms of their dexterity in managing the power of love for the sake of Sufi religious and social goals.

41

4.3 A king bowing to an ascetic in a scene of nature. From a copy of

Khamsa of Nizami. Iran, ca. 1470. Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper. Text and illustration: 25.1 × 16.4 cm. Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase—Smithsonian Unrestricted Trust Funds, Smithsonian Collections Acquisition Program, and Dr. Arthur M. Sackler, S1986.61 fol. 101b.

4.4 An old Sufi man pursuing a young man. From a copy of the

Matlaʿ al-anvar of Amir Khusraw Dihlavi, 1485. 20 × 15 cm. Copyright © Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin. MS. 163, fol. 38a.

LOVE’S END: MELDED BODIES

As I have mentioned previously, the two ultimate aims of the Sufi path from the earliest systematic expositions of Sufism as a prescriptive system were annihilation in God (fanaʾ fillah) followed by subsistence in divine reality (baqaʾ billah). The Sufi’s road to God represented a lover’s progress toward the beloved, and the achievement of the ultimate states meant the elimination of all distinctions so that the lover, the beloved, and love itself all became one. As I have shown in this chapter, Sufi love pertained not just to the relationship between the human and the divine but also to the interconnections between Sufis themselves. In this vein the ultimate step for the consummation of the relationship between Sufis in the positions of lovers and beloveds was their subsumption into each other.

A number of hagiographic narratives I have cited in this chapter present the fulfillment of the relationship of love between masters and disciples through stories in which their bodies become mutually indistinguishable. Ibn Bazzaz Ardabili reports that as Safi ad-Din Ardabili became closer to his master Zahid Gilani, following their initial meeting, his body began to acquire the properties of the master. Their eventual merging into each other is reflected in the verse:

Between the same veins, brain, and skin,

one friend became colored with the same qualities as the other.

42

To prove this point, he relates a story in which Safi ad-Din experienced the same thing as his master even when they were a long distance apart. He states that Zahid suffered from ailments of the eyes by the end of his life, and one day in Gilan his eyes began to burn painfully when he put in some medicine. At this very moment Safi ad-Din left the companions he was sitting with and, much to their surprise, jumped into a pool of water for no apparent reason. They recorded the time of this event and realized later that this had occurred exactly when Zahid had felt his eyes burning from medicine. The burning sensation that originated in the experience of one body was thus felt in the other because of their identity.

43The interchangeability of Sufis’ bodies is eventually predicated on the idea that individuals who either have natural religious aptitude or have reached high stations can act as mirrors for others. From the early years of Shaykh Safi’s life, Ardabili reports that one day, as he sat in a mosque, a man appeared and told him that he should put his affairs in order because he was scheduled to die in exactly three days. Safi believed him and came to sit in the same place after three days with a heavy heart, awaiting his end. Then another man appeared and told him that the man who had initially told him about his impending death had himself just died at the appointed moment. The explanation for this lay in the idea, derived from a hadith report, that a true believer is like a mirror for another believer. The man who had informed Safi of his death had in fact seen his own death in a vision, but the bodies had been interchanged because Safi’s body could act as a mirror for that of others.

44A similar phenomenon is described in Ja

ʿfar Badakhshi’s memoir of

ʿAli Hamadani, who reports that once when the master had just left Badakhshan for Khuttalan, one of his disciples went into his room and saw him sitting there. But when he was about to ask why, and when he had canceled the trip, the image of his body disappeared. He then figured out that the image of Hamadani’s body had become so firmly lodged in his vision that he was liable to see it even when the master was gone. Badakhshi states that the ultimate example of this kind of vision of the master was when he himself would first see Hamadani’s face upon looking into a mirror, the image then changing to his own face after a few moments.

45The ultimate effect of this kind of identity between the bodies of masters and disciples was to ratify the transmission of Sufi authority through an unbroken intergenerational chain. In effect, showing that the body of the disciple was interchangeable with that of the master was the most emphatic means of legitimating succession. Works on Ni

ʿmatullah Vali report that, in his youth, he was greatly puzzled why the famous Uvays al-Qarani, who became devoted to Muhammad despite never having met him, proceeded to break all his own teeth upon hearing that Muhammad had lost some teeth in a battle. Uvays then appeared in a dream to him and said that breaking the teeth was the equivalent of digging a treasure, since by acting thus upon his own body he had created a connection to the body of the Prophet.

46 Similarly, a disciple reported that sometimes when he looked at Khwaja Ahrar he would see the face of Muhammad that he had earlier seen in a dream.

47In addition to the interchangeability of bodies, a number of sources reflect this imperative of the Sufi social milieu in reports that, toward the end of their lives, masters would start referring to their chosen successors with the name of their own earlier masters. In a case where the Sufi genealogy parallels actual descent, the Khwajagani master Sayyid Amir Kulal is said to have referred to his son and successor Amir Hamza as “father” (

pidar).

48 Such a presumption of continuation over generations was especially potent in cases where the masters were, like Amir Kulal and Hamza, sayyids claiming descent from Muhammad and

ʿAli. This is reflected also in the prominence of genealogy in hagiographies devoted to Shah Ni

ʿmatullah Vali and

ʿAli Hamadani, two other shaykhs with sayyid ancestry.

49Reflecting a situation where masters and disciples were not related, a number of links in the Kubravi chain are shown exhibiting this phenomenon in different hagiographic narratives. Badakhshi provides stories in which the master

ʿAla

ʾ ad-Dawla Simnani (d. 1336) treated his student Akhi

ʿAli Dusti as his master.

50 ʿAli Hamadani inherited his Kubravi affiliation from Dusti and Mahmud Mazdaqani (d. 1365), another disciple of Simnani. Badakhshi’s own claims with respect to Hamadani are couched in the incident of his looking into a mirror, and the pattern continued in later Kubravi links. Muhammad Nurbakhsh claimed that his master Ishaq Khuttalani (d. 1424) would often confuse him with his own master, Sayyid

ʿAli Hamadani. The very same claim is made in a hagiography deriving from the lineage of Sayyid

ʿAbdallah Barzishabadi (d. 1468), who was a rival to Nurbakhsh for the claim of being Khuttalani’s successor.

51 And Nurbakhsh’s praise for his own son and successor Qasim Fayzbakhsh includes the comment that there was no difference between the two of them save the fact that he was older than the son.

52The melding together of Sufis’ bodies as represented in these reports worked to substantiate and solidify Sufi communities both synchronically and diachronically. When invoked for a master-disciple dyad, the process ratified the significance of the idea of the Sufi path (tariqa) shared by all who were part of the living Sufi community surrounding a master. And when appealed to for the connection across multiple generations, the process sanctioned the chain (silsila) that lay at the base of the Sufi construction of religious authority. As I have emphasized before, the path and the chain together constituted the two crucial factors in the formation of powerful and widespread Sufi communities in the Persianate world.

LOVE AND EMBODIMENT

The stories I have discussed in this chapter can help us understand the salience of the rhetoric of love in hagiographic narratives. Persianate Sufis in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries articulated their strongest bonds with each other using the language of love, and this love was produced, sustained, and consummated corporeally. In Sufism’s doctrinal logic, the ultimate purpose of these relationships was to lead disciples to God, though Persianate hagiographic narratives convey a clear sense that for most, if not all, this ultimate goal could be achieved only through the intermediary of love directed at a human guide. As I have shown in previous chapters, pursuing the Sufi path required Sufis to negotiate the physical world whose availability was contingent on the bodily senses. The emphasis on love, which connected human hearts to each other through the intermediacy of bodies, represented a continuation of this significance of the body beyond personal experience to the social sphere.

To end this chapter, I introduce a work that stridently exemplifies the patterns relating to love I have discussed in the preceding pages. The necessity of human love as a prelude to divine love is advocated most emphatically in Kamal ad-Din Gazurgahi’s compendium of brief biographies entitled

Majalis al-ʿushshaq (

The Assemblies of Lovers) completed in the first decade of the sixteenth century.

53 This work presents heavily reworked versions of the biographies of Sufis and others whom the author describes as extraordinary lovers. The cast of characters consists of Sufis from the past as well as the author’s own times, prophets, lovers of poetic legends (such as Majnun and Farhad), and famous poets, rulers, and viziers. Although most of the information presented in the work is not seen in other sources, it is distinguished by the author’s single-mindedness in infusing history with the spirit of human love mediated by corporeal contact. Its significance lies not in being a source of information but in containing the most categorical presentation of a cultural topos prominent during the time it was composed.

All of Gazurgahi’s biographies work according to the formula that a protagonist is identified for having a special capacity for love, which leads him to become infatuated with another person as a prelude to realizing his love for God. The most cogent explanation of this theme occurs in his entry on the great Sufi author Ibn al-

ʿArabi whose significance for Persianate Sufism I have discussed in earlier chapters. Unlike other Sufi authors, Gazurgahi’s interest in Ibn al-

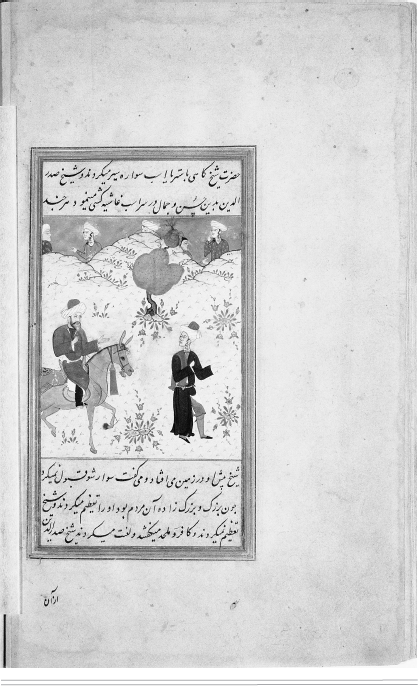

ʿArabi is not based on appreciating his writings and ideas. His entry on the master portrays him as a lover of his young and beautiful disciple Sadr ad-Din Qunavi (d. 1273–74). His obsession with the young man is depicted in numerous illustrated manuscripts of the

Majalis al-ʿushshaq that were produced during the sixteenth century (

figure 4.5).

54 The narrative surrounding the image states that one day, when Ibn al-

ʿArabi was astride an animal, he ran into Qunavi, and the latter showed obedience to him. Ibn al-

ʿArabi in turn got off the steed and fell on the ground in front of the young man, begging him to ride the animal. Qunavi refused, which led other people to praise Qunavi and condemn Ibn al-

ʿArabi, calling him an unbeliever and a heretic. This embarrassed Qunavi, but Ibn al-

ʿArabi told him, “Do not be ashamed; instead, expend effort so that you cut your relationship to created beings and become attached to the Truth.”

4.5 Ibn al-

ʿArabi encountering Sadr ad-Din Qunavi. From a copy of Gazurgahi’s

Majalis al-ʿushshaq. Bibliothèque nationale de France. MS. Suppl. Persan 1559, fol. 103b.

Gazurgahi writes that Qunavi’s shame over this incident led him to ensconce himself in his home for a few days, which caused Ibn al-ʿArabi to grow beside himself from desire. A companion then tried to distract him by suggesting that he visit the beautiful sights of Damascus. When Ibn al-ʿArabi indicated that nothing in the world was beautiful when the beloved was not around, the companion suggested that he should seek God directly rather than through an earthly intermediary. Ibn al-ʿArabi’s purported reply to this criticism is worth citing in detail since it captures the main point of the general attitude I see reflected in much of Persianate hagiographic literature:

The beauty of traces connected to metaphorical love is the shadow and extremity of essential beauty that is linked to true love. As in the proverb “metaphor is the bridge to reality,” one is the means for acquiring the other and the road toward reaching it. The fact is, that a given person has limited innate ability for the love that is occasioned by the beauty of the Essence in itself … and much of it remains hidden behind dark veils. If a shadow from the light of that beauty makes itself apparent when it takes shape in the tapestry of clay that is the heart-ravishing, well-proportioned beloved, then:

Gentle manners, being well-spoken, and nimbleness

are wound-dressers on every heart’s mark of sorrow.

[From them, the heart] acquires the pure hem of a new blown rose,

which is boldly free of all contamination.

[Once this has occurred], the bird of the lover’s heart promises itself to the beloved and spreads feathers and wings in the desire for requiting love. It becomes captive to the beloved’s food and prey to his snare, and it renounces all purposes and indeed knows no purpose other than him:

From the mosque and the hospice (khanqah) he moves to the tavern,

he drinks wine and arrives drunk at the beloved’s door.

Whatever is not love for the beloved despairs him,

he comes shopping for it with a thousand lives.

Love’s fire and desire’s flames become lit within him and result in the burning away of the curtains of secrecy. [Love and desire] lift the veil of ignorance from his spiritual sight and clear the mist of multiplicity from the mirror of truth [within him]. Then his sight sharpens and his heart comes to discern the truth. Everything he passes, he recognizes and everything he lays his eyes on, he sees. Every moment he turns his face to the attester within him (mashhud-i khud) and says:

You were hidden in the breast, and I was oblivious.

You were apparent to sight, and I was oblivious.

My whole life I was seeking a sign of you from the world,

you yourself were the entire world, and I was oblivious.

When [the lover] reaches this place, he knows that metaphorical love had been the equivalent of a smell from the tavern of true love, and the love of traces had been like a shadow from the sun of the Essence. However, if he had not smelled that smell he never would have reached that tavern and if he had not found that shadow he would never have had a share from that sun.

55

As reflected in Gazurgahi’s work as well as the rest of the material I have presented in this chapter, Persianate Sufis were in search of beloveds who could help them progress further on the Sufi path. For Sufis beginning their religious conditioning, beloveds were those acknowledged as the great living masters of the day, whose bodies acted as sites of beauty that invited love and desire, forming the ineluctable intermediaries between the human and the divine. But, hidden from ordinary perception, the great masters were also lovers in search of beloved disciples whom they wanted to compel into falling in love with themselves. The pursuit of disciples was as much of an imperative for the masters as the desire for a master was for novices, and everyone’s fulfillment was predicated on being caught somewhere in the net of love. Love encompassed the circle of youth and old age, of life and death, which is why it thoroughly permeated the world of customary interactions depicted in most stories recorded by Sufi hagiographers.