It is likely that the account I have given in

chapter 4 makes Persianate Sufism appear as a world in which ideology and social patterns combine effortlessly to enable Sufi masters and disciples to pursue each other as lovers and beloveds. This impression flows in part from the idealizing tone characteristic of hagiographic narratives that are my main sources. Persianate hagiography and miniature painting are cognate genres in this regard. Both present human figures and interactions in abstracted forms that convey established conventions. Understanding the conventions provides us access to the authors’ idealizations, which can, in turn, be regarded as symptoms of social ideologies. As I have argued in the introduction in the context of discussing embodiment as an analytical tool, conventional images regarding love or other matters cannot be taken as descriptions on face value. Instead, these images reflect patterns that we can interpret using phenomenological, sociological, and hermeneutical methods to arrive at judgments about the workings of society.

Stylized though they certainly are, hagiographic texts also provide substantial details that exceed the genre’s didactic and prescriptive intent. On this score, texts are different from paintings since, first, the fund of material available to us is much larger, and second, verbal narratives have a higher capacity for accommodating incidental or peripheral details in comparison with highly condensed images that have to fit on pages of manuscripts. In this chapter I aim to exploit materials that occur at the margins of hagiographic narratives and allow us to complicate the story beyond understanding the authors’ own investments. I see

chapter 5 as a necessary companion to

chapter 4; the two should be read in conjunction to see the overall picture I wish to convey in this book.

My rubric for discussion is the question of desire and its connection to the construction of gender in the milieu depicted in Persianate Sufi literature. Desire is a matter deeply interwoven through Sufi ideas from the earliest periods. In Sufi theoretical discourse, praiseworthy desire that has God or a master as its object is referenced under the term

irada. The centrality of such desire to Sufi social practice is evident from the fact that the standard term for a disciple is

murid, the one who desires, and the master is designated as

murad, the one who is desired.

1 As stories discussed in the previous chapter can attest,

irada as desire is the driving force behind love relationships between masters and disciples. However, along with providing the details of desire that leads to idealized love between masters and disciples, hagiographic narratives register the functioning of other types of desires in the context of human relationships that stand in tension with “proper” behavior. Represented as blameworthy, or at least of ambiguous value, such desires are nevertheless critical in defining normative or recommended behavior.

Desire is a multifaceted topic, and I should clarify that I am concerned here with it only in the narrow sense in which it finds representation in Persianate hagiographic literature. A treatment of desire as a general subject pertaining to these societies would require bringing in other materials as well as a consideration of methodological questions regarding gender, sexuality, and social history as a whole that are beyond my present scope. Such explorations are virtually nonexistent for the sociohistorical context I am discussing and would be welcome additions to the literature.

2I treat the operation of desire in Persianate Sufi discourse in four sections. I begin by considering an extended narrative poem composed in the fifteenth century that allegorizes desire and love through the entanglement of characters named Beauty and Heart. Comprehending the allegory’s intent and internal details provides us a framework for understanding Persianate Sufis’ view of the way sense perception of beauty in the form of the human body could lead to the production of desire and love among human subjects. In addition to being an anchor for the present chapter, this treatment of desire should help provide further depth to the stories I have discussed in

chapter 4.

In the second section of

chapter 5 I concentrate on Sufi representations of inappropriate desires, which play out differently when the parties involved are solely men or men and women. The available sources were all written by men and do not provide any information about women’s homosocial contexts. Situations involving reprehensible love between men arise largely when one party is perceived to be religiously corrupt and responsible for leading a Sufi on a path away from a master. In hagiographic narratives there are occasional hints at proscription of male homosexual desire, but love as an emotional attachment, whether proper or improper, comes across as being a far more significant concern than sexual contact. My observation in this regard matches what has been said on this topic in other recent evaluations of various types of materials produced in pre-modern Islamic contexts. In particular, it is significant to note that what we find in these sources is not affirmation or condemnation of “homosexuality” as a mode of behavior but judgments based on the relative positions occupied by the parties. Any proscription of male-to-male desire proceeds not from a condemnation of homosexual acts but from the way the acts may signify the presence of a socially improper relationship between the men in question.

3While sexuality among men is a matter of hints, indirect reference, and the question of power, it appears front and center in the representation of relationships between men and women. The ubiquity of the dyadic construction of desire and love in which the lover and the beloved have different characteristics has significant repercussions for women’s participation in the authority structures that governed life in Persianate Sufi communities. Almost all medieval Sufi thought takes men as its standard and, by implication, excludes women as significant Sufi actors. This exclusion pertains to the arena of love as much as it does to other spheres since males can occupy all the different positions available in the paradigm of love vis-à-vis other men. In addition, Persianate poetic paradigms that provide the overall framework for the articulation of Sufi love relationships largely presume both the lover and the beloved to be male.

When it comes to the question of representing male-female relationships in formalized literature, the critical concern that defines hagiographic authors’ limitations is the possibility, or lack thereof, of marriage between the two parties. A woman married to a man could be shown interacting with him since their interactions provoke no legal censure. Similarly, there is no problem showing women interacting with their fathers, brothers, sons, and married uncles since such men are categorically prohibited from marrying them. Beyond these two possibilities lies the status of being

na-mahram, which applies to men and women standing in such positions with each other that they could be married but are not.

4 Any interaction between such persons that involves desire has strict legal limits that work to exclude men and women from each others’ social spheres. Since hagiographic and other Sufi literature is largely about men, its representation of women not tethered to the identities of men portrays the women in a particularly disadvantageous light. In this situation the question of power between the two parties parses differently than between men alone since it is presumed within the gender difference rather than being negotiated in the context of the mutual relationship between lover and beloved. Hagiographic narratives provide evocative stories that criticize acts involving contact across the gender line committed by male disciples in the beginning stages of the path.

In the third section of the chapter I concentrate on women and men in relationships that allow unrestricted social contact between them. This includes representations of Sufis’ mothers, who are shown to compete with masters for the affection and allegiance of their sons who become Sufi disciples. In contrast with mothers, wives of celebrated masters sometimes appear as accomplished Sufi disciples and at other times as concupiscent and disrespectful persons who constitute trials for the masters and remind them of the low value of the material realm. The chapter’s last section treats the exceptional but important case of a woman who appears as an accomplished Sufi master able to guide another highly regarded male master. The contrast here concerns social intercourse, and the representation of this woman’s interactions with Sufi men is valuable for assessing the Sufi view of gender in the Persianate context.

The vast majority of Persianate hagiographic stories and representations concern men alone, with women making marginal appearances, usually in supporting roles. Nevertheless, my argument in this chapter is that gender is a critical place to look within this material to understand the social world reflected in the texts. One overarching reason for this is the pervasive tendency among Sufi authors to map the interior-exterior divide onto the presumed inherent difference between male and female. The following statement attributed to the Kubravi master

ʿAli Hamadani summarizes this tendency: “Only women are interested in the physical world because this is the place of colors and smells.”

5 Although this is a common enough sentiment in the literature, the details of hagiographic stories provide an abundance of evidence for great Sufi

men’s seduction by the colors and smells of the physical world. The actual narrative material available to us thus dissembles from the stated ideology, indicating a more complex view on both gender and the material world than what first meets the eye when we read Sufi texts. Here again we see the thorough entanglement of what are portrayed as interior and exterior aspects of existence rather than the enforcement of a clear dichotomy. Desire and gender, my two foci in this chapter, therefore act as wedges that allow us to pry open some hidden recesses of the social and textual worlds being examined in this book.

SIGHT AND SEDUCTION

Citing an unnamed earlier source, the hagiography of Shaykh Ahmad Bashiri provides the following description of how love affects the human body:

The heart is like a fire whose flames denote love. Arising conditions and premonitions (

ahval va ilham) are like the wind that makes the fire blaze. When the wind stokes the fire, if the flames reach the eyes, it cries; if they reach the mouth, it moans; if they reach the hand, it moves; and if they reach the foot, it dances. These conditions are called “finding” (

vajd), because although love is in the heart, it is not really known until it is exteriorized. When the wind flares the fire, the traveler finds the way he had lost.

6

To get a fuller sense of the complexities involved in Persianate Sufi notions regarding relationships between love, the senses, and aesthetic value hinted at in this pithy description, we can turn to the allegorical masnavi

Husn-o-dil (

Beauty and Heart) composed by Muhammad Yahya b. Sibak Fattahi (d. ca. 1448) in 1436. This work is a grand summation of the paradigm in question and underscores the centrality of desire and love in the Sufi religious quest. The narrative poem is around five thousand verses long and is so complicated and full of nuances that the author himself was compelled to write a prose explanation for it under the title

Dastur al-ʿushshaq (

The Confidant of Lovers). Between the two versions we get a useful window for understanding desire, love, and human sensory faculties.

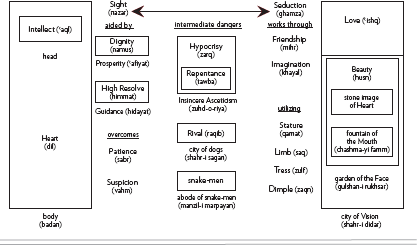

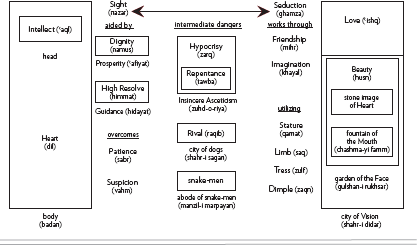

7I have laid out the details of the allegory in chart 2 in order to provide a sense for the multilayered nature of the narrative. However, it would be a considerable distraction to go into all the details in my main narrative of this chapter. The story—in brief and excluding the minor characters—goes like this: a king of Greece named Intellect has a son called Heart, whom he keeps imprisoned in the castle of Body. Heart’s companions tell him of the Elixir of Life, which bestows eternal life, and he becomes obsessed with obtaining it in order to live forever. His servant Sight volunteers to go look for the elixir and discovers, on the way, that it is to be found in a fountain called Mouth, which is within a garden called Face, which lies within the city of Vision. This city is the abode of a princess named Beauty, daughter of a king named Love. Sight undertakes the arduous journey to reach this garden, and when it arrives there after overcoming numerous opponents, it is greeted by Seduction, a protector of Beauty who turns out to be his own long-lost brother. Seduction takes Sight to Beauty, who welcomes it and tells of a stone statue in her treasury whose identity is a mystery to her. Upon seeing it, Sight informs her that this is a likeness of Heart. At this point in the story, Sight and Seduction have become united and have discovered a filial relationship, and Heart and Beauty turn out to have been seeking each other without knowing it themselves.

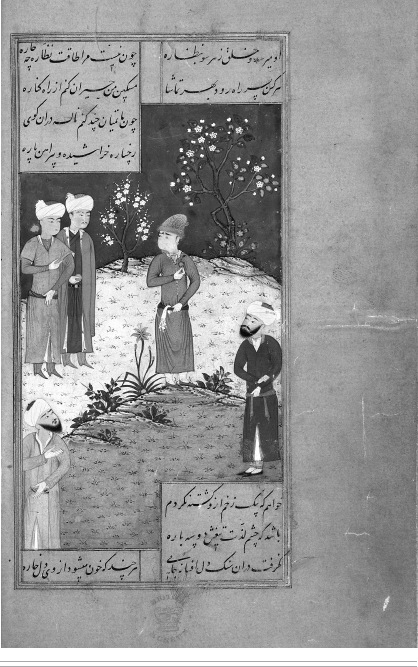

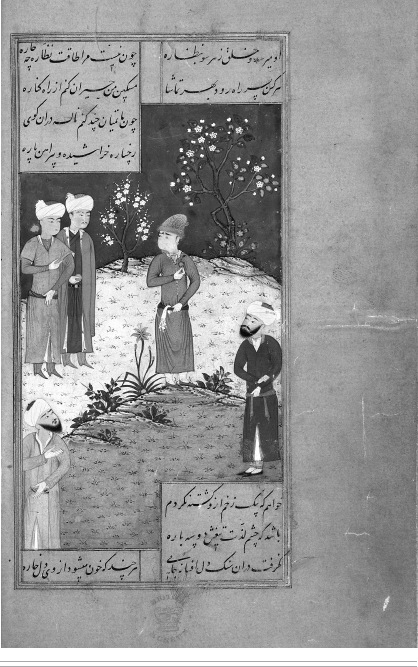

The discovery of the statue’s identity makes Beauty want to meet Heart and she sends Sight back to him with her message and a confidant named Imagination. When the two get back to Body, Imagination creates a likeness of Beauty, and Heart falls in love with her immediately. At the same time, one of Intellect’s soldiers named Doubt informs his master that Heart may escape Body because of his ardor for Beauty, leading Intellect to imprison Heart, Sight, and Imagination. Sight manages to escape using a ring given to it by Beauty that can make it invisible to humans and arrives back at the city of Vision after another difficult journey, which involves overcoming various opponents. Beauty is incensed by this state of affairs and calls upon her aides to overcome Intellect. Her helpers in this endeavor are her father Love and their combined forces, which include Friendship, Seduction, Stature, Limb, Tress, and Dimple. This she eventually accomplishes, following the scene depicted in a manuscript painting in which Heart and Sight capitulate to Friendship and a sword-wielding Seduction (

figure 5.2). In the process, however, Intellect is able to turn Heart against Beauty. The victorious Love then decides to imprison Heart in the castle of Separation for a while after his defeat by Love’s forces. This situation is corrected through the intervention of High Resolve, who convinces Love to bring Intellect back into the fold as the vizier of Body and to accept Heart as Beauty’s husband.

8

5.1 Chart 2: Schematic diagram showing the narrative of the allegory Husn-o-dil.

In the conclusion of the allegory, Heart comes to live in the garden of the Face and is permanently united with Beauty. He finally acquires the Elixir of Life from the well of Mouth, desire for which put the whole narrative into motion. Near the vegetation of the soft Down that surrounds Mouth, he meets Khizr, the prophet famous for eternal life based on a Quranic story. Khizr tells Heart that eternal life was his destiny because his status was always beyond being imprisoned in a body made of elements. Heart’s drinking the Elixir of Life is therefore a fulfillment of his fate. Beauty and Heart have many children, one of whom is the narrator of this tale.

The four main characters in this allegory—Heart, Beauty, Sight, and Seduction—are particularly relevant for my discussion since they pertain to the production of desire. Although separated in the beginning and joined at the end, Heart and Beauty are shown to have subterranean connections throughout, as evident in Heart’s desire for the Elixir of Life in the first place and the idea that Beauty has a likeness of him in her treasury. The union between Heart and Beauty comes about through Sight and Seduction, their aides who go forth from the abodes of their masters to do their bidding. Importantly, Sight and Seduction are long-lost brothers who overcome their alienation to work together toward the narrative’s overall fulfillment. Sight is an agent endowed with bravery, loyalty, and perseverance while Seduction deploys Beauty’s warriors Stature, Limb, Tress, and Dimple to accomplish its job.

5.2 Heart and Sight in front of Friendship, with Seduction holding a sword. From a copy of Muhammad Yahya Fattahi’s

Husn-o-dil. Copyright © British Library Board. MS. Or. 11349, fol. 45b.

The story’s allegorical message presents heart as an organ in search of beauty, where beauty carries the possibility of acknowledgment from the heart within itself. Heart’s desire for beauty can be quenched only through sight, a sense that issues outward from the body to search in the external world. In its turn, sight can get to beauty and carry its news back to the heart only by being seduced by external forms such as face, stature, limbs, tresses, and dimple. Beauty is an abstraction encompassed by these physical elements, which sight must apprehend before approaching it. In the final analysis, then, heart and beauty are meant for each other, but they can be joined together only through the intermediacy of sight and seduction—a sense extending outward and a force pulling inward—that operate in the material world.

The aesthetic theory summarized in this allegory pertains to both material and nonmaterial forms. Although heart and beauty occupy pride of place, they are clearly dependent on apprehensions in the material sphere to come into contact. Sight is an agent of the heart’s desire that finds certain material forms seductive and compelling. The beauty of external forms is a kind of natural force that arrests and seduces sight and the other senses and, through them, the heart. The interdependency of heart and beauty, on the one hand, and sight and seduction, on the other, should be reminiscent of the circle of love I described in the previous chapter. In this allegory, and in stories about great masters and disciples, heart’s conjunction with beauty is a wholly desirable end. However, the inherent connection between sight and seduction as elaborated in the allegory also provides the possibility of their improper functioning: sight can be seduced by deceptive objects, leading the heart to fall for improper beauty.

The gender dynamic between the four main characters is particularly significant since it hints at different roles for male and female. The prince Heart is entombed in a negatively valued body, which his foremost servant Sight overcomes through its escape to Beauty. The primary aide to the princess Beauty, on the other hand, is Seduction, who works in conjunction with body parts. Male and female bodies get mapped to lover and beloved with opposite connotations: one is to be escaped from, while the other is to be displayed. This gender dynamic does not map directly to Sufi hagiographic representations of men and women. There, beauty is equally likely to be found in men and women, and those who possess beauty adopt the characteristics associated with it in this allegory irrespective of their gender identity.

9In the overall theory, beauty is both the ultimate objective on heart’s true path and a disruptive force that can lead into error. Similarly, heart must rely on sight to get to true beauty, but it can get entranced by improper beauty as well. In considering this allegory as a guide for understanding Sufi hagiographic stories, it is important to keep in mind not just the beginning and the end of the narrative but also the various processes that unfold in the middle. Sufi narratives about the lives of masters and disciples provide ample examples for the many possibilities registered in the allegory regarding the creation, management, fulfillment, and denial of desire mediated through material senses and bodies. While the allegory works toward ideal ends, hagiographic stories convey desire’s ability to induce proper love as well as to lead astray.

BODIES DESIRING AND DESIRABLE

Echoing a theme central to

Beauty and Heart, the Naqshbandi master

ʿAla

ʾ ad-Din Abizi is reported to have told his disciples that God has endowed human beings with three preeminent organs: eyes for seeing, ears for hearing, and the heart for loving. These three organs operate without reference to volition: the eye sees whatever comes in front of it, the ear hears whatever sound enters it, and the heart falls in love when impulses from the external senses alert it to the presence of a beautiful being. Just as Sufis have to guard their eyes and ears from being in situations where they may be subject to reprehensible sights and sounds, they have to guard their hearts from beauty that can lead astray. The surest way to do this is to enter the orbit of a Sufi master so that one’s capacity for love becomes occupied in the religious pursuit.

10This formulation of the role of senses is helpful for seeing the way the connection between sensations and emotions works in the Persianate Sufi context. Although Abizi puts the heart on a par with eyes and ears, it is clearly a sensing organ of a different type and scale than the other two. For one, the heart is dependent on impulses from the external senses to recognize its object. Moreover, love is an emotion that can come to preoccupy one to the utmost, whereas sensations that take shape in the eye and ear are momentary and can be disrupted through blocking the organs or turning away from the scene. As described in the allegory, beauty and its capacity to invoke desire and love in the heart are more complex matters than sight and sound pure and simple. To see some of the complexities involved here, I will treat hagiographic stories concerned with the operation of desire between men and between men and women.

Men as Subjects and Objects of Desire

The connection between beauty and desire is evident in stories where great Sufi masters are shown to have heightened sensitivity to beauty irrespective of the object’s status. For example,

ʿAli Hamadani’s hagiographer states that the master himself related that when he was a young man traveling to find his vocation he lost consciousness when he saw a beautiful young man in the bazaar in Isfara

ʾin and became a spectacle for the crowd. A disciple of the master Muhammad Azkani who was present there went and told him the tale of someone who had swooned upon seeing beauty. The master asked that Hamadani be brought to him immediately, and this message was delivered to him when he regained consciousness. That night Muhammad appeared to Hamadani in a dream and told him to take on oath on Azkani’s hand, and, when Hamadani met the master the next day, Azkani told him that Muhammad had delivered him the same instructions. Hamadani and Azkani thus became joined by one Sufi understanding the other’s spiritual capacity through the report on his reaction to beauty. Here the beautiful man himself has no relevance to the story apart from being an object with a remarkable external appearance.

11Other stories involve young men who are affected by beauty but have to be helped away from improper associations through masters’ intervention. Abizi’s hagiographer provides proof for the master’s views on the heart as an organ I cited earlier by relating actual incidents, such as the case of a disciple who reported that he had become infatuated with a beautiful young man. One day when he appeared in front of the master after having spent time pining after this beloved, the master was angry and told him that he was going down his own path, which was negating his guidance. He then sat with the master and was, through his presence in his company, gradually relieved of his desire for the other man.

12 In a similar story, the master Shams ad-Din Ruji reported that once, when he had become a disciple of Sa

ʿd ad-Din Kashghari, he fell in love with a beautiful man such that he could neither give up the infatuation nor get rid of his shame and embarrassment in front of the master for the situation. Eventually, Kashghari arrived in front of him by himself and absolved him of the love by putting his hands on his chest and working on his interior.

13Kashghari is himself featured in a story reported by his son Khwaja Kalan. It is said that when Kashghari was seven years old he accompanied his father on a trading trip where the party also included a most beautiful boy of Kashghari’s own age with whom he became infatuated. One night when the lamps had been extinguished and the two boys were sleeping next to each other, Kashghari got the desire to take the other boy’s hand and rub his eyes on it. But he had barely extended his hand when one corner of the room opened up to reveal a formidable figure with a lamp who came toward him rapidly, crossed over, and then disappeared into a cavity that had opened up at the opposite corner. Kashghari said that he was terrified by this experience and took it to be a warning that dissipated his desire for the relationship.

14

Shah Qasim-i Anvar

In hagiographic materials relating to the fifteenth century, the most prominent case of relationships between Sufi men that are hinted at as being improper involve the master Shah Qasim-i Anvar, who is remarked upon as a man of high spiritual attainment but unable to properly control those attracted to him. The charges against his entourage are always left vague, and some of the criticism may reflect either inter-Sufi rivalries or Qasim’s purported sympathy for the apocalyptic Hurufi movement that had him expelled from Herat after a failed attempt on the life of the Timurid ruler Shahrukh (d. 1447) in 1427.

15 A hagiography of Khwaja

ʿUbaydullah Ahrar states that, even in his old age, this Naqshbandi master considered Qasim-i Anvar the most charismatic Sufi he had met in his life. He reported that whenever he had gone before him he felt “that the whole world circles around him to eventually descend into him and disappear [within him].”

16 Although he was clearly a remarkable man of his age, Qasim’s hagiographic profile is marred by the fact that a number of authors pointedly criticize some of his disciples.

ʿAbd ar-Rahman Jami writes that he had personally met some of Qasim’s followers and considered them outside the pale of Islam altogether. One follower, whom Jami considered a worthy Sufi, told him that Qasim himself told him not to stay with him because of some of his other followers. Jami’s explanation for the contrast between Qasim’s own undeniable excellence and the waywardness of some of his followers is that he was too generous a person to shun anyone who came to him because of his innate attractiveness. People inclined to worldly pleasures took unjust advantage of this by deriving meanings from his words that he did not intend.

17 In Ahrar’s words, as his hagiographer reports them, people explained Qasim’s situation in two ways. They believed that he was either aware of his disciples’ corruption, but suffered it as his fate, or these disciples were like the thorns put on top of walls around an orchard that keep thieves and animals away from the fruit. The prize protected by the thorns in this case was Qasim’s true spiritual station, which he wanted to keep hidden from strangers.

18The same source that reports this provides the most detailed description of the activities of Qasim-i Anvar’s followers. It reports that Ahrar said that once, when Qasim had come to Transoxiana, his followers got together and went around the bazaar to collect beardless young boys (

pisaran-i amrad) with whom they began to establish relations. Their explanation for this behavior was that they were observing the beauty of God in the beautiful forms of these boys. As this was going on, Qasim asked after his followers by saying, “where have those pigs of mine gone?” Ahrar indicated that this meant that, to Qasim, these men appeared as pigs when he saw with his spiritual sight (

nazar-i basirat).

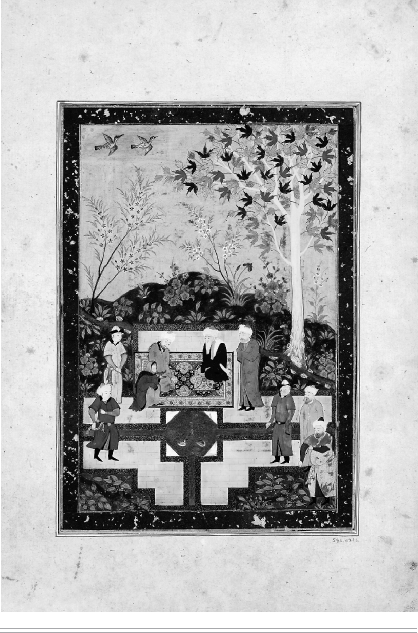

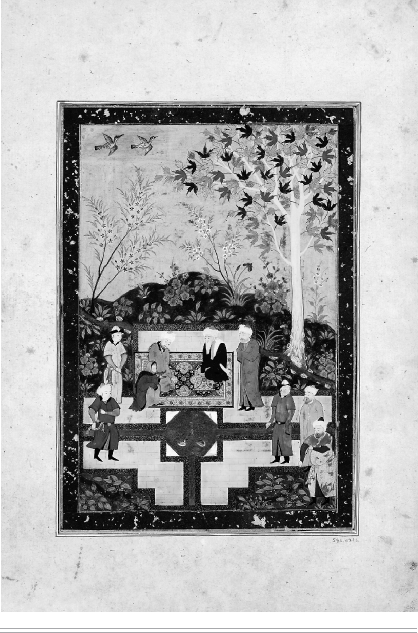

19 The practice of contemplating young boys as beautiful forms that represent divine beauty is usually known through the term

shahidbazi and has a controversial history in Sufi contexts. It is the chief defining feature of the work

Majalis al-ʿushshaq, which I have discussed earlier. While it is difficult to substantiate

shahidbazi as a widespread social practice, such “looking” is a common feature of Persian poetic rhetoric. The theme is reflected also in the painting that is a part of an anthology and is accompanied by the verse of

ʿAbd ar-Rahman Jami. (

figure 5.3).

In Ahrar’s view, to act amorously toward beings who were only outwardly beautiful was a grave error. As mentioned in the previous chapter, Ahrar’s own story of attachment to the master Yaʿqub Charkhi involved falling in love with a master described as having a beautiful form. This, however, was a case of a person with a high spiritual station being able to control how he appeared to others in order to attract and guide them. His and others’ criticism of Qasim-i Anvar’s followers stems from the fact that they took physical beauty by itself as a legitimate object of love without reference to its deeper meanings. For a man to fall in love with a man deemed outwardly beautiful was not a problem in itself; the difficulty occurred only when the subject and object of desire were not part of a larger framework tethered to Sufi ideology.

While reports about Qasim absolve him from being responsible for the unnamed corrupt behavior of some of his followers, it is clear that he was seen as somewhat of a failure as a Sufi master. His attractiveness is remarked upon by one and all, but his unwillingness or inability to control the disciples is seen as at least an unwitting weakness. The ultimate cause for this was his incapability to manage the desires of those connected to him. His personal charisma was such that people were attracted to him, but unlike the truly consummate masters, he could not adequately control and manipulate the relationships established on the basis of this attraction. This flaw in his personality was at least in part responsible for the fact that he did not initiate a long-lasting Sufi community despite acknowledgment that he surpassed his contemporaries in charisma. This lack of a dedicated community meant that he never became the subject of an extended hagiography dedicated solely to his miracles and achievements, and narratives regarding him have to be culled from works devoted to others.

5.3 Men contemplating a beautiful youth. Shirvan, 1468. Opaque watercolor. Copyright © The British Library Board. MS. Add. 16561 fol. 79b.

So far I have related stories in which handsome men are objects of someone’s desire. A story regarding Ahrar provides a glimpse of the other side in the form of the haughty attitude adopted by a man known for his beauty. When the master returned to Herat after becoming attached to the Naqshbandi chain through Ya

ʿqub Charkhi, he attended the house of an associate who was dedicated to the Khwajagan and greeted him with great respect. In fact, Ahrar’s new association was so apparent on him that everyone present paid him great respect save one young man famous for his looks. On this occasion the host told Ahrar that although everyone had already eaten, if he was hungry food could be prepared. Before Ahrar could reply, the handsome man, who was used to being treated with deference, interjected to say that time for food was over. Noticing this rudeness, Ahrar indicated that he would teach him a lesson and proceeded to request that food be prepared for him. Then he worked on the handsome man’s interior so that he fell in love with him and went out himself to make the fire for the food. His face became dirty from soot in the process, spoiling the beauty of which he had been so proud earlier. From that time onward, he forgot about his own beauty and became an absolute devotee of Ahrar. The story marked the triumph of the Sufi master’s beauty over the attractiveness confined to external forms.

20Stories of attraction and love between men in hagiographic narrative indicate censure only in cases when lovers fall in love with beautiful beloveds whose status or moral attributes do not conform to Sufi values. The authors register no problem with the fact of a deep and abiding love between men who find each other physically attractive as long as they are appropriately positioned with respect to each other and are aware of beauty as an attribute for those truly worthy of being objects of love. This pattern contrasts significantly with cases when one of the parties is a woman not in such a relationship with a man where that would allow them unrestricted access to each other.

Desiring Women

A most emphatic example condemning a Sufi man’s attraction for an unrelated woman is presented in the hagiography dedicated to

ʿUmar Murshidi. The master said that, during his youth in Kazarun, one day he went into the desert and on the way back heard a beautiful voice, which he greatly enjoyed. He felt tremendous desire to see the person to whom the voice belonged and could not get this idea out of his head even when he returned to his Sufi chamber and immersed himself in his religious pursuits. Then, when he was reading the Quran, he suddenly heard a voice commanding, “Look!” When he did this, he said, “I saw a woman, naked from head to foot, sitting and showing me her vagina, unhesitatingly and boldly, uncovering herself in a way that no wife would ever do in front of her husband.” The voice then said, “This is the woman whose voice you had heard and taken pleasure from. Your hearing her voice is the same as seeing her vagina.”

21This story implies the dangers of being led astray by sensory perception more strongly than anything present in narratives involving men alone. The Sufi’s apprehension of a pleasant voice and the possibility of seeing a beautiful being leads to something indecent in a way never indicated for a handsome man. The critical issue that makes the difference here is that men’s social relationships with women are subject to legal surveillance that does not apply to matters between men. What may seem like an extraordinary jump between Shaykh

ʿUmar’s hearing a woman’s voice to her appearing naked in front of him is a direct reflection of Islamic legal ideology in which social intercourse between men and women is regulated according to the possibility, or lack thereof, of a lawful sexual relationship between them. Since Shaykh

ʿUmar is neither married to the woman nor in a relationship that would make marriage impossible, his access to her has significant legal limitations. On this basis, the connection caused by her producing a sound and his hearing it laterally shifts the situation to the sexual domain immediately.

22A number of other, milder examples can be added to this story to make the point. A disciple of Amin ad-Din Balyani, another master from southern Iran, said that one day, when he was in the mosque, he heard a woman’s voice and was intrigued to see her. As he was walking over to take a peek, a stone fell on his foot and rendered him unconscious. Later, when he went to see the master, he told him to be glad that he had not actually seen the woman. In that case the punishment would have come to his eyes rather than his feet and could have blinded him.

23 Similarly, a man said that before he came to ask Baha

ʾ ad-Din Naqshband to become his disciple, he had spent time in an empty house with an unrelated girl with whom he talked and to whom he gave a kiss. When he expressed his intention of becoming a Sufi to the master, he replied that this did not seem to go along with his other recent behavior, which was illegal. The master’s knowledge of the matter was one of his charismatic miracles.

24 Once when Khwaja Ahrar was instructing disciples on the necessity of averting the gaze from a woman because it would cause lust, a man asked what about a case where there is no lust. Ahrar got angry and said, “Even I cannot have a lust-free gaze; where have you come from that you can do it?”

25To these stories one can add a case involving Shaykh Safi of Ardabil, in which the direction of the gaze is inverted from female to male. As I mentioned in

chapter 3, this master is known for spectacular dance when in the throes of ecstasy, during which he would leave the ground and sometimes hover over the whole assemblage. Once, when this occurred, the walls of the room picked themselves up from the ground and joined in as well, causing the sensation of an earthquake in the area. A woman, who was a sayyid and married to a nobleman, came out of her house to see what was going on. When people told her, she waded through the crowd to get to the mosque in order to see the shaykh for herself. However, as soon as her eyes alighted on him he sat down. Some people present there realized that this was because an unrelated woman had seen him, and they asked her to leave. She complied with the request and thought to herself, “If this audition were an effect of the carnal self (

nafsani), it would have intensified with the gaze of a

na-mahram. But, since it was an audition of the outpouring of divine secrets (

fayz-i asrar-i ilahi), it became illegal with contamination from such a gaze.” She then became a disciple of the master and gave away a part of a village to him.

26It should not come as a surprise that Sufi hagiographic representations pay close attention to legal strictures regarding male-female relationships. These texts are products of the religious literati who can be expected to adhere to established conventions in such matters. There is, however, no reason to take these legal strictures as literal descriptions of reality and presume that men and women interacted very narrowly in this context. Even hagiographic narratives do contain instances of unrelated men and women connected through gazes that do not merit censure. For example, once an old and decrepit woman came to see Khwaja Ahrar and sat down close to him. He asked her why she had come and she replied, “we have come to see your beauty.” To make a joke of this, he turned to an associate and said, in a soft voice so that she would not hear, “and what do we get to see?”

27 Although rare, women do make it to pictorial representations of Sufi gatherings, as in

figure 5.4, which shows one as part of the company assembled around a Sufi master. While homosociality can be presumed to have been a widespread norm, a larger range of interactions and attitudes become visible as we turn to other stories involving women.

In the allegory Husn-o-dil, the male and female main characters are separated and interact in stylized ways according to a particular gender ideology. Hagiographic representations differ from this in that both males and females can come to occupy the place of beauty and become seductive to the sight of a lover. Moreover, in the hagiographic sphere, seduction by beauty is ubiquitously subordinated to the legal framework in which male-female interactions are subject to far greater scrutiny than those between men alone. In the remainder of this chapter, we will attempt to see whether, and to what extent, representations of females show them in the position of the heart who seeks higher beauty in the form of the great Sufi masters and God, through its sight and other senses.

5.4 A Sufi gathering in a garden. Bukhara, 1520-1530. Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper mounted on an album page, 22.1 × 14.2 cm. Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase—Smithsonian Unrestricted Trust Funds, Smithsonian Collections Acquisition Program, and Dr. Arthur M. Sackler, S1986.216.

MOTHERS AND MASTERS

In the previous chapter I discussed stories regarding Shaykh Safi ad-Din Ardabili’s early years, in which his mother figures prominently. However, the mother disappears from the narrative once Shaykh Safi becomes a disciple of Shaykh Zahid, and I argued that the transition from mother to master represents a changing of the guard with respect to guidance and love provided by a caretaker. This pattern is evident in a number of different places in hagiographic literature and can be regarded as the distinctive view on mothers of Sufi men in this material.

The interchangeability of the mother and the master is traceable in instances where the master is shown fulfilling a distinctly maternal function. One example of this that employs striking bodily imagery comes from the early life of Baha

ʾ ad-Din Naqshband. His main hagiographer relates that after Naqshband had entered into a relationship with the Khwajagani master Sayyid Amir Kulal, he was once passing through a village that was home to a Sufi master named Shams ad-Din. This master was suitably impressed by his potential and attempted to persuade him to stay with him rather than continue the journey. Naqshband’s response, which convinced Shams not to pursue the matter further, was: “I am a child of others. Even if you were to put your breast of training (

tarbiʿat) in my mouth, I would not grasp the nipples.”

28 The same metaphor is used in another work dedicated to Naqshband as well, albeit from a different angle. Khwaja Muhammad Parsa reports, when Naqshband finished his training with Amir Kulal, that the master told him, “I have dried up my breasts so that the bird of your spirit may come out of the egg of your base humanness. But your bird has gone much farther than [merely] this.”

29A story that portrays the Sufi master in a maternal role and in competition with an actual mother of a disciple is given in hagiographies dedicated to Khwaja Ahrar. Ahrar himself related from the earlier master

ʿAla

ʾ ad-Din Ghijduvani that he went to join the circle of Amir Kalan Vashi at the age of sixteen. This master instructed him in the Khwajagani path and told him that he must hide his Sufi affiliation from everyone, including people very close to him. He did as he was told, but it became difficult to hide his activity when he began to grow progressively weaker as an effect of bodily mortifications. His mother noticed the change and asked him if he was sick, which he denied. She perceived the answer as recalcitrance and, as a challenge, threw open her shirt to reveal her chest and said that she would not forgive him the milk he had drunk from her breasts if he did not come clean. He then saw no way out except to tell her the truth, and she herself decided to join the Khwajagani path upon hearing of the master’s instructions. However, her decision caused

ʿAla

ʾ ad-Din consternation because she had not been authorized by the master. He raised the matter with Amir Vashi, who said that it was fine and that he gave her the permission. Then one day, when he and his mother were alone at home, she asked him to get a pot of warm water. She did ritual ablutions from the water in front of him, prayed two cycles, and began doing Sufi exercises and shortly passed away.

30ʿAlaʾ ad-Din Ghijduvani’s story matches that of Shaykh Safi in that the masters take control of the young men’s bodies at the beginning of the Sufi path. In both cases women are shown as competing with the masters for their sons’ affection and obedience, although they eventually acquiesce to the transfers. ʿAlaʾ ad-Din’s mother goes one step further by herself becoming a Sufi and being removed from the narrative completely through death. Both stories represent the future masters’ mothers as having approved the sons’ paths, even though this means losing their sons. There is no way to avoid this, however, since the young men’s maturation as Sufis depends on being in love with the master over the mother.

The hagiography of Zayn ad-Din Taybadi presents a story with an alternative end to the mother-master competition over a young disciple. The author of this work relates from Zayn ad-Din’s son Shams ad-Din that one day, a man unknown in the area appeared in Zayn ad-Din’s gathering. The master asked him to sit down, but he first kept standing, lost in thought for some time, and then yelled loudly, fell down, and fainted. The master felt great pity for him and took care of him personally while weeping himself. When the man was completely recovered, he sent him away with the promise of remaining in touch, saying that he should go back to his mother because she greatly desired to see him. As he was leaving, people asked him how he had met Zayn ad-Din since no one had ever seen him before. He told them that he was from the region of Fars and that he had been saved when Zayn ad-Din had appeared miraculously somewhere at a moment when he had been in grave danger. He had been looking for Zayn ad-Din since that time and had realized that he had found him at the moment when he had yelled and fainted earlier.

31This story represents the rare case of a mother retaining her power over a Sufi son. Positing this story next to the ones I have related earlier highlights the fact that the earlier mothers are shown to have been willing participants in the paths undertaken by their sons and voluntarily gave up their control. The juxtaposition also underscores the fact that, under hagiographic conventions, a successful bond between a great master and an outstanding disciple is a fated event. When it occurs, a disciple is being incorporated into a Sufi group’s selfarticulation, and, when it fails to happen, the disciple is excluded from charismatic functions. The connection is essential for the continuation of the Sufi intergenerational chain of authority, which must remain unbroken in order to perpetuate a valuable mode of religious practice. The movement between the two types of love represented by the mother and the master is thus a necessary precondition for the functioning of the Sufi mode of perpetuation of religious authority.

32WOMEN MARRIED TO SUFIS

The vast majority of Persianate Sufi masters whose lives form the subject of hagiographic narratives are described as married men after the early years of Sufi searching in their lives. Equated with the commencement of heterosexual relations, marriage is avoided until the time when men are thought to have overcome sexual urges likely to lead them astray from religious pursuits. Stories relating the great masters’ marital alliances provide a glimpse into the valuation of women as well as men. Such stories include cases where the women are shown to be worthy companions for the masters or situations in which they are seen as trials brought upon the masters to strengthen their religious resolve. Under both options, the masters are shown to have tied the knots to the spouses willingly, but women’s purported actions have different repercussions for understanding the construction of gender in this context.

Sufi Wives

In literature produced during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the most detailed example of a wife with the same values as her Sufi husband comes from a work concerned with the life of Fazlallah Astarabadi, the founder of the Hurufi movement. Written by one of his chief followers and successors, this work describes Fazlallah as a strict ascetic during the period he was just beginning to acquire fame as a master in Tabriz around 1370. His followers at this time included a vizier named Khwaja Bayazid Damghani, whose wife, also a devotee, was originally from the city of Astarabad and related to Fazlallah. This couple wished to arrange the marriage of their fourteen-year-old daughter to Fazlallah, and the mother approached him through one of his disciples. At first, she was told that the matter was difficult since the circumstances in which Fazlallah lived, incumbent on anyone who became attached to him, would be particularly arduous for a woman. She persisted by asking for the exact conditions and was told that the girl would be required to forsake all personal belongings upon leaving her parents’ house; renounce any food or dress that could not be paid for by the small means of a dervish; determine never to take a single step out of the Sufi hospice where Fazlallah lived after entering it; adopt a bed made of sackcloth, a felt pillow, and a cotton dress; respect the religious community’s practice of seclusion at night; and adopt the stringent collective prayers practiced daily by the community.

The prospective wife’s mother was glad to hear these conditions and asked the girl what she thought of them. She wholeheartedly agreed because of the spiritual return she and her parents would attain as a result of the harsh life she would lead. She first spent four months in the house of another dervish, as a kind of trial to make sure that she could withstand the difficulties, and then married Fazlallah. Her entry to the dervish community was marked by the symbolic step of putting on the distinctive green dress worn by all of Fazlallah’s dedicated followers. Besides the generally harsh living conditions, she also worked alongside other dervishes to sew caps that were sold to provide for the community’s food and other bare necessities. In connection with this marriage, Fazlallah was asked about the permissibility of sexual relations, and he said that they were not spiritually harmful as long as the intention was procreation and not pleasure.

33We do not have any further representations of the activities of Fazlallah Astarabadi’s wife in Hurufi literature. However, the same follower and hagiographer who provides the story about her represents one of his daughters named Kalimatallah Hiya al-

ʿUlya as his main heir after his execution in 1394.

34 Historical and hagiographic sources external to the Hurufis state that this daughter remained active later on and that she and her husband gathered a considerable following in Tabriz, which led to hostility from the local community of scholars. The Karakoyunlu ruler Jahan Shah (d. 1467) was able to resist pressure from her enemies for some period but eventually gave in and issued the fatal order that led to both her death and the massacre of more than five hundred followers in 1441–42.

35A story similar to that of Fazlallah Astarabadi’s marriage is related from the life of Shaykh Ahmad Bashiri, although here the woman makes numerous appearances in the narrative following her betrothal. The author relates that the master’s associates included a man of high status who would come and visit him often. On one occasion he found the meeting so moving that he exchanged turbans with the master and was later made to understand by a friend that that indicated the development of a family relationship. He then approached Shaykh Bashiri, offering the hand of his twelve-year-old daughter Bibi Fatima. The master was initially reluctant to agree to the match because he wanted to remain celibate, but he then had a dream in which “men of the unseen” brought a woman to him and married her to him. He took this to be a command and acquiesced to the proposal. The marriage tie had an important effect on the lives of his parents-in-law as well. They did not have a male child and asked the shaykh for an intervention. They were soon graced with the birth of twin boys.

36Both Bibi Fatima and her mother, Amr Khatun, are mentioned a number of times in this work, the latter designated as Shaykh Ahmad’s vicegerent among women. This work is exceptional in that it explicitly describes women as equal to men in their religious accomplishment.

37 The work iterates multiple times that women were a part of the master’s inner circle of devotees throughout the various phases of his career.

38 The author mentions the procedure used for women when describing initiation into the group: at the point where the master is supposed to take the disciple’s hand in his own, he offers his sleeve to the woman to hold in order not to cross the legal boundary that proscribes touching among

na-mahram s. Interestingly, the oath of discipleship he is reported to have administered includes the promise on the part of the disciple not to look at a

na-mahram, but this does not seem to have caused women to be excluded from Sufi guidance by the master.

39 In fact, the hagiographer makes the point that women and men dedicated to Shaykh Bashiri tended to lose their carnal desires completely: in one case, a woman who was married to a man for seven years had had so little real contact with him that she could not even recognize his face.

40

Women as Burden

Some stories relating to the wives of famous masters show the men in states of vulnerability and powerlessness. These are rare situations since the hagiographic paradigm as a whole involves disciples and heirs representing the great masters as phenomenally powerful beings. Moreover, the total authority invested in images of masters works to justify the claims of the successors who either sponsored or wrote the hagiographies, making an indication of vulnerability counterproductive for their purposes. The way the narratives rationalize the masters’ vulnerability provides an important view into the construction of gender as well as the social dynamics of Sufi communities and literary patterns in general.

The author of the

Rashahat tells of a master named Tunguz Shaykh in Turkestan who belonged to the family of Ahmad Yasavi. A visitor to his place saw that his wife paid no attention to matters like cooking, usually associated with women. On this occasion, as Tunguz Shaykh was bending down to a fire that was refusing to light, his wife came in and gave him a swift kick such that his head went into the fire and his face was covered with ash. Much to the surprise of the visitors, he continued with his work and ignored this insult. When asked about his forbearance, he replied, “The knowledge and states that have become apparent to us have been due to our patience in putting up with the oppression of the ignorant.”

41 In this instance the master’s wife wholly personified the worldly burdens the Sufi must endure in order to acquire religious merits.

Detailed stories of a wayward wife of a prominent master relate to the Naqshbandi Shaykh

ʿAla

ʾ ad-Din Abizi, who is otherwise portrayed as having been a tremendously powerful presence in front of his disciples. The hagiographer reports that he and his wife used to fight a lot, and once she hit him so hard that his forehead was bloodied. In his anger he grabbed her head and turned it so that it went halfway around, facing backward. Seeing this terrible condition, a child of theirs of five or six pleaded with the father, so that he restored the woman to normalcy. She was then grateful, feeling remorse, and gathered the area’s notables to declare publicly that she forgave her dower and any other rights owed her.

42This incident did not resolve all Shaykh Abizi’s difficulties with his wife. Later he again appeared in company with his collar torn and a bloody forehead, prompting someone to ask why he did not just divorce the woman, particularly since she had forgiven her dower and this would not even have monetary implications. He replied that she was a sayyida and that the fault had been his own because he had been rude to her. He then went and apologized to the woman. In his more extended explanation for his forbearance, he said that she was an affliction he knew and he was afraid that if he got rid of her something worse would alight on him. Going deeper than this, he also explained that putting up with this wife and taking care of children were necessary for him to stay in this world and obey God’s commands. Otherwise he would be absorbed completely in the interior reality and would not be able to perform obligations like prayers and fasting. The hagiographer states that this explanation was akin to other stories of great men: a master would ask a servant to beat him whenever he experienced a great mystical state in order to keep him in the world. The author then suggests that these instances were equivalent to the famous report according to which Muhammad would ask his wife

ʿA

ʾisha to intrude upon his thoughts by saying, “Talk to me, Humayra.”

43The representation of the relationship between Shaykh Abizi and his wife presents important clues for understanding gender in the context. First, the male-female difference here maps exactly to the interior-exterior dichotomy critical to Sufi thought, enforcing the notion that women are tied to lower, material forms while men have the capacity to delve into the highly valued interior. This is, then, a case of the interior-exterior difference being carried into the social sphere in a way that gives the dichotomy greater power and naturalizes the gender difference and hierarchy. Taken at face value, women appear, like children, devoted to their carnal desires even when they are sayyidas. On the other hand, men wish to ascend out of the material world toward a more noble existence. By this token, men who do not live up to their potential are like women, as exemplified in a story about a master who got very agitated when he saw a religious scholar of questionable merit approaching him and asked his disciples to lead him away. When someone suggested that this man was knowledgeable, the shaykh responded: “In my eyes he was a naked black woman with drooping breasts, showing all manner of ugliness.” While this master stated this out in the open, Ahrar opined that the most upright masters cover up such matters when they become visible to them because of their special sight rather than stating them in the open.

44 In this instance the interior-exterior division that forms the basis of abstract Sufi thought is a matter enacted in social and textual forms.

Beyond the arguments stated in the texts, stories about recalcitrant wives married to Sufi masters contain important information when we consider the frames within which they are set. The narrators are male Sufi adherents who write from the positions occupied by men who question the masters about their putting up with the women and not divorcing them. They are

murids, those who desire the master and cultivate deep love for him, thereby competing with masters’ wives and children for affection and emotional as well as material resources. One source asserts this explicitly, calling the disciple’s transformation into a new body after progressing on the Sufi path a birth that is the product of a kind of marriage between the desiring disciple and the desired master.

45 My suggestion throughout this book that hagiographic narratives be seen as textual performances provides us a way to make sense of the stories that make powerful masters appear vulnerable through negative valuation of women attached to them.

WOMEN AS ACCOMPLISHED SUFIS

The contrast between praiseworthy and troublesome wives in the stories discussed hinges on the question of whether the women in question are also Sufis. When they are, their interests with respect to the masters are aligned with those of other, mostly male, Sufis, leading to positive representation in hagiographic narratives. And, when they are not Sufis, their needs and demands disrupt the largely male-to-male world of Persianate Sufism. Given these strictures, we can expect that the most laudable female characters to be found in hagiographic narratives would be Sufi relatives of the masters, including wives, mothers, sisters, and daughters. As we have already seen, this is indeed the case, and women tend to become valuable particularly when they constitute crucial links between men who are deemed important.

46

Exchange of Women Among Men

When Shaykh Abizi fights with his wife in the stories previously discussed, one of his reasons for later self-censure is the acknowledgment that the woman is a sayyida and thereby deserving of special respect. This is particularly important since Abizi is not a sayyid himself and can allege kinship with the Prophet only as an affine through marriage. Although Abizi’s wife’s relationship with the Prophet is very remote (she lived eight centuries after his death), the general respect accorded sayyids means that she occupies an intermediate role between two important men. This is the position in which we find many other women as well in hagiographic narratives.

A few examples of this pattern are helpful to make this point. Proceeding chronologically among masters discussed in the book, Shaykh Safi ad-Din Ardabili is shown to have thought explicitly along these lines. Once he had become a confidant of Shaykh Zahid Gilani, the master one day asked: “How is it that there is a master who has such a disciple that the master’s station is because of his [disciple’s] honor?” Shaykh Safi first thought that he was talking about the two of them, but then the master added: “The master gives his daughter to him, who gives birth to a child whose honor ratifies the station and glory of the father and the grandfather.” Shaykh Safi then thought that the master was talking about another man who was his son-in-law, and he became especially attentive to him. However, at the age of seventy Shaykh Zahid eventually married another woman who gave birth to a son and a daughter. This daughter was Bibi Fatima, Shaykh Safi’s future wife, who became the mother of the man who eventually became both his and Shaykh Zahid’s heir.

47Continuing this pattern, it is reported that Baha

ʾ ad-Din Naqshband had four daughters, three of whom were married to disciples or their sons and became mothers to later members of the group.

48 Similarly,

ʿAbd al-Avval Nishapuri, one of Khwaja Ahrar’s main successors, was also his son-in-law.

49 Importantly, Nishapuri also wrote a hagiography of Ahrar, indicating an overlap between kinship structures and textual production of the saintly figure’s life. In hagiographic representations of exchanges of women, the relationship of love and desire is always between fathers-in-law and sons-in-law rather than either of the men and the woman through whom kinship is established. This characteristic reinforces the male-centeredness of the narratives in terms of both the regulation of an emotion as powerful as love and the ability to establish voluntary relationships.

Women as Exemplary Masters

Shaykh ʿUmar Murshidi’s hagiographer reports that the master said, when he traveled to Mecca to perform the hajj, that an old man told him an amazing story. He said:

One day as I was circumambulating, I saw a woman who was doing the same while skipping on one foot. I asked her about her condition. She said, “I have a suckling child still in the crib. I came from my own region in order to perform the hajj with the intention to return. As I started the circumambulation, I heard the child crying, so I started moving the crib back and forth with one foot. With the other foot, I continued to go around [the Ka

ʿba] and also performed the rites of running between two hills (

saʿi), in order that neither [obligation] would be forfeited.” She said that there was three months’ worth of distance between the two places.

50

The principle exemplified in this story—that space can contract for the religious elect—is a widespread motif in Sufi literature and is discussed in

chapter 7. The story provides an easy way to imagine the more restricted mobility allowed to women as compared to men in the societies in question. While God is shown to allow the woman to perform the great ritual because of her spiritual station, that that does not mean absolution from her maternal duties. The double burden on this woman as compared to men was in part responsible for women not becoming major players in the Sufi social world. In material I have surveyed for this book, there is one narrative that stands out for its exceptionality when it comes to discussing the possibility of women becoming full-fledged Sufi masters. There may well be other examples of female masters in sources not known to me at present, although a handful more would not negate the general point I am making. My example pertains to Kalan Khatun (literally, Elder Lady), daughter of Sayyid Amir Hamza, the son and chief successor to the Khwajagani master Sayyid Amir Kulal. What we know of this woman comes from a hagiography of the family written by her own son Amir Shihab ad-Din. This is a man who had legitimate free access to her, so that the case does not violate the rule of hagiographers not making unrelated high-status women subjects of discussion in the “public” hagiographic sphere.

Shihab ad-Din relates that when it came time for Amir Hamza’s death he asked two of his nephews, one by one, to be his successor. The older of the two declined because he was a complete recluse, while the younger preferred to serve people in other ways than being a Sufi guide. He then turned to his own children and overlooked two of his sons in favor of his daughter, saying that everyone seeking him should seek her and that, just as some people are proud of their sons, he was proud of his daughter. Shihab ad-Din states that, while his mother was the subject of numerous miracles that were well known to her close relatives, he did not consider it appropriate to relate these in the open.

51 While his ostensible reasoning for this reluctance is that this would divulge the secrets of a Sufi, this clearly pertained only to women since he describes the miracles of men in great detail throughout the rest of the text. Such an attitude automatically restricts women from becoming recognized as prominent friends of God since public affirmation of the ability to perform miracles is a crucial aspect of being accorded this status.

After registering his reluctance, Shihab ad-Din does tell one story regarding his mother’s spiritual powers. The particulars of this story are revealing in that they show the additional steps a woman needed to undertake so as to act as a full-fledged Sufi master in this context. He relates that some time after Kalan Khatun’s accession to her father’s mantle, the prominent Khwajagani master and author Khwaja Muhammad Parsa decided to go to Mecca for the hajj and came to Amir Kulal’s shrine to ask his permission. After visiting the grave, he said that he must also ask permission from Kalan Khatun since she was Amir Kulal’s heir and her father had said that whoever seeks him must seek her. He proceeded to her house for the visit, which occurred without the two ever coming face-to-face with each other. Upon his arrival, she sent some simple food to him to welcome him, and then he asked her servant to go and ask her permission for his journey. When she heard the request, she asked the servant to bring a plate, which she filled with plaited cotton and sent out to Parsa, who fell into a trance upon seeing it. When he regained consciousness, he told his companions that he had just learned something critical about himself and then he proceeded to Mecca. He performed the hajj normally, but when it came time to start the return journey, he asked the leader of the caravan to wait a couple of days. He then died in Mecca before leaving the holy city and was buried in the cotton that Kalan Khatun had given him at the time of his departure.

52The interaction between Kalan Khatun and Khwaja Parsa in this narrative contrasts interestingly with the majority of inter-Sufi relations that pertain only to men. In terms of her religious ability to lead disciples, Kalan Khatun appears as competent as her male counterparts: she is ratified strongly by her father, who was her own guide, and she can interpret Parsa’s future to be able to guide him. She also provides for Parsa’s future by giving him the cotton, knowing that he would pass away while traveling. Unlike the male masters, however, her interactions with Parsa are conducted through the intermediacy of another person (the servant) and an object (plaited cotton). Because as a na-mahram it is socially inappropriate for her to be face-to-face with Parsa, her ability to provide guidance requires an additional step. This requirement amounts to a restriction because it makes such a relationship cumbersome. Moreover, as discussed in the previous chapter, male masters’ greatest power lay in their ability to establish love relationships with disciples that began with physical contact and ended with the bodies of masters and disciples merging into each other. In contrast, a woman could not display herself in public to become an object of love, and her female body was too different, both physically and socially, to meld with the bodies of male disciples.

Kalan Khatun’s case presents important contrast with the way relationships between male Sufis are shown to have progressed in Persianate societies during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The great Sufis among men became enmeshed in intergenerational chains and extended communities: they very often inherited their authority from multiple masters, and their power as religious and sociopolitical leaders derived from their ability to convey their charisma to large numbers of disciples through relationships described in the language of love. The constrained versus open potential in the two cases was, ultimately, a function of societal attitudes toward bodies: restricted from becoming objects of love, persons embodied female remained marginal to the massive expansion of Persianate Sufi social networks during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. This meant that any Sufi chain of authority likely to proceed through a female link was greatly disadvantaged from the start. Such a chain could be extended beyond the female master either through other women, with whom the female master could interact freely, or through close male relatives, such as father, husband, or son, who could have unproblematic loving relationships with her. It is then no accident that the only female master I have mentioned here is described as a Sufi with a public role in a hagiography penned by her own son. In contrast, most male masters were subjects of works written by men who were not consanguines. This fact severely limited a woman’s capacity to lead a social network that included both men and women. It is, of course, possible that women had separate all-female Sufi networks that were led by women, as can be documented for modern Muslim societies. However, such networks remain obscure to us because all medieval Islamic sources at our disposal concern themselves exclusively with social arenas managed by men.

53I end this chapter by registering a twist regarding the story of interactions between Kalan Khatun and Khwaja Parsa that further illuminates the gendered nature of hagiographic narratives. Kalan Khatun is not mentioned in any work other than the

Maqamat-i Amir Kulal, but two later Naqshbandi sources provide a story in which Khwaja Parsa interacts quite similarly with another

male master. The author of the works state, on the basis of unspecified sources, that when Parsa decided to go on the hajj, he sent a messenger to Khwaja Da

ʾud, the maternal grandfather of Khwaja

ʿUbaydullah Ahrar, to perform an augury (

istikhara) regarding the auspiciousness of the journey. Khwaja Da

ʾud gave the messenger a fox’s fur for himself and a pickaxe for Parsa. The man found the gift of the fur quite odd since this was during a time of warm weather, but he kept it with him, thinking that there must be something to it. Later he was once stuck in extreme cold and the fur saved his life. Parsa took the pickaxe with him to Mecca, also without knowing the reason behind Da

ʾud having sent it to him. When he died in Mecca, that instrument was the only thing people could find to dig his grave.

54The two “dueling” stories regarding Parsa demonstrate the mutually constitutive nature of gender, lineage, and the process of hagiographic narration in multiple ways. The narrators belonged to rival branches of the Khwajagani lineage—issuing from Amir Kulal in the case of Shihab ad-Din and Bahaʾ ad-Din Naqshband in the case of Safi and Samarqandi—both of which regarded Parsa as an authoritative figure because of his literary fame. The ultimate aim of Safi and Samarqandi was to glorify Khwaja Ahrar, which made them especially attentive to Shaykh Daʾud, Ahrar’s maternal grandfather. Their major difference lies in that the two stories involve important women, albeit in different roles. Kalan Khatun speaks and acts in Shihab ad-Din’s version, while the unnamed woman who was Daʾud’s daughter and Ahrar’s mother is a critically important but silent presence in the story given by Safi and Samarqandi. Ahrar’s hagiographies, in which the woman is silent, have been regarded as authoritative accounts of Naqshbandi-Khwajagani Sufi chains since the sixteenth century. Conversely, the work in which a Sufi woman speaks and acts authoritatively survives in an obscure modern lithograph edition and a handful of manuscripts. The historical fates of the texts mirror the ambivalence regarding women we see present throughout the materials that survive to give us a picture of Persianate Sufism. Concentrating on the way women are portrayed allows us to see the constructed nature of roles ascribed to female as well as male bodies.