The title of

chapter 7 refers to a Sufi dictum that uses a highly corporeal metaphor to advocate disciples’ total voluntary submission to Sufi masters. According to manuals for proper conduct, the oath of discipleship requires aspiring Sufis to submit themselves to unconditional manipulation by the master, becoming like inert corpses in morticians’ hands.

1 Many stories I have related here testify to the significance of this metaphor’s underlying message as an aspect of Sufi rhetoric in Persianate societies. In the present chapter I concentrate on hagiographic representations of direct enactment of masters’ control over the bodies of others.

I aim to utilize the image of corpses in morticians’ hands in two ways. First, it refers to stories that show masters manipulating and repairing disciples’ bodies in protective as well as coercive contexts. As hagiographic stories indicate implicitly and explicitly, disciples’ voluntary submission is one side of a bargain in which they acquire protection from powerful beings. However, as this occurs, the limbs and sensory functions of disciples’ bodies are shown to become subject to masters’ wills. Representations that convey masters’ powers in this arena make them appear as “hypercorporeal.” They are able to appear in multiple places at the same time to protect their dependents, and they are shown to intervene upon disciples’ phenomenological experience by assuming control over their senses. Episodes that exemplify these processes provide symbolic ballast to the notion that masters’ bodies extend far beyond the confines of their own skins, becoming identical with social bodies formed from their circles of influence.

My second use of the corpse and mortician metaphor relates to the authorship of hagiographic narratives. While masters are certainly the manipulating morticians and disciples the corpses within the internal thrusts of stories, the positions invert when we recall that hagiographic narratives are the products of disciples’ hands and represent portraits of the masters as seen from the vantage point of their successors. Masters’ powerful performances highlighted in these texts do not represent their own claims about themselves. Instead, they are witness reports from those who are protected or coerced by the masters. Given that virtually all hagiographic texts at our disposal were compiled after the deaths of the masters they glorify, the stories they contain can be read as disciples’ morticianlike manipulations of masters’ bodies. In the context of trying to understand the ideological underpinnings of this literature, hagiographic compilations contain details of masters’ lives selected with an eye toward being serviceable to their successors.

In the discussion that follows I underscore the second meaning of the corpses metaphor by concentrating on narratives concerned with the deaths of great masters. Depictions of the dissolution of masters’ powerful bodies constitute optimal locations to see the socioreligious logic of hagiographic narratives. These deaths are portrayed as cataclysmic events and as moments when authority transfers from masters to their successors. Both these themes go toward clarifying the underlying ideological interests of those who wrote or sponsored hagiographic texts.

A consideration of masters’ deaths leads also to the way their bodies are memorialized after their disappearance from the physical world. I see this occurring in three places: in the bodies of their descendants and disciples, through the efficacy of shrines constructed over their gravesites, and through the compilation of hagiographic narratives that promulgate stories about their corporeal performances. Masters remained available to those invested in their charismatic presence through their descendents and close disciples who had formed love relationships with them during their lifetimes. These groups represented corporeal continuity since the descendants were physical products of the masters’ bodies, and, as I have shown in

chapter 4, disciples often promoted their spiritual inheritance with the claim that their bodies had become indistinguishable from those of their erstwhile teachers by the time the masters died.

In addition to human heirs, the charisma of great masters became physicalized through the construction of shrines at their gravesites, which were places for pilgrimage as well as elite sponsorship. Royal and other patronage of Sufi shrines and their associated communities is a major feature of the architectural history of Central Asia and Iran during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Visiting the graves of the religiously eminent and elite sponsorship for the construction of elaborate structures over them influenced religious ideology as well as social and economic patterns in this historical context.

In my view, stories depicting great Sufi masters’ corporeal exploits were the most critical element in promulgating the memory of their powerful presence after their deaths. Such stories allowed disciples and descendants to memorialize masters’ earthly lives as well as present their own claims for authority, which often went hand in hand with the establishment of shrines. Hagiographic compilations that contain these stories can be regarded as orchestrated sedimentations of memories of great masters’ presence in the flesh during their lifetimes. To become known as God’s powerful friends, Sufi masters needed such stories to be told about them during their lifetimes. After their deaths, the aggregation of stories into spiritual biographies exhibiting varying levels of coherence enabled their descendants and successors to continue to benefit from their reputations. Over larger spans of time, stories concerned with many masters were grouped together according to categories such as genealogy, lineages, or geographical location. Stories about Sufi masters’ extraordinary powers were a critical element in the process through which these men became focal points for the establishment of communities and networks in Persianate societies during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. By highlighting these themes in this chapter, I aim to bring together the arguments regarding hagiographic literature I have put forth in the course of this book.

2THE LIVING AND DEAD BODIES OF SUFI DISCIPLES

The fact that discipleship to a Sufi master demanded total corporeal subservience is a common theme in Persianate Sufi literature. The author of the Khwajagani work

Maslak al-ʿarifin contextualizes such submission with respect to its benefits by stating that when disciples acquiesce to the desires of a master completely, all the organs of their bodies start performing zikr. This indicates a total reorientation of sensory functions since it means that the eye stops seeing individuals classified as

na-mahram, the ear stops registering that which is not beneficial to the person, and the whole body becomes involuntarily obedient to the shari

ʿa so that the fear of God becomes totally dominant in the person.

3 The oath of discipleship acts like protective armor around the body, allowing disciples to maintain their religious obligations in adverse situations as well as be protected from outside harms. While disciples are required to show obedience, the same imperative obliges masters to spread themselves through time and space in order to be able to provide protection to multitudes of dependents.

Manipulation and Control

In the hagiographic context, masters’ control over disciples’ bodies is shown to operate in a number of different dimensions. Relatively straightforward cases involve incidents in which disciples are asked to alter themselves based on their affiliation with a master. For example, Amir Kulal is said to have forbidden a new disciple, who had earlier been a Qalandar, from the practice of shaving his beard with the explanation that it now belonged to the master rather than the man himself.

4 In addition to requests or commands, masters are also shown to have the ability to affect others without verbal articulation. A report in the

Safvat as-safa states that, in the beginning of his career, Safi ad-Din Ardabili’s gaze held such intense power that it could imprison people, disenabling them from exercising control over their own bodies without knowing what had caused this condition to come upon them.

5Masters’ control over bodily functions extended to religious experiences, so that disciples were not free to pursue their own agendas without the master’s advice and agreement. This was justified by the idea that disciples required, for the sake of their own safety, appropriate and adequate preparation before being allowed to experience intense states. The seriousness of this issue is reflected in the story of a disciple of Shaykh Ahmad Bashiri who died right after experiencing an ecstatic state. The master’s explanation was that, for the state to be beneficial rather than fatal, the effort he had expended should have been combined with the master’s permission and guidance.

6These stories about masters asserting their rights over disciples’ actions represent an amalgamation of protection and coercive control. Taken on face value, masters’ authority is a protective mechanism that is being implemented for the benefit of those who are being restrained. But the deadly consequences of cases where disciples fail to submit mark these stories as threats that allow Sufi authoritative figures to assert their domination over their subordinates. The double function of these narratives can be seen repeated in the context of stories that reflect inter-Sufi and other rivalries articulated through the question of proper religious practice. In these instances masters are able to regulate their disciples’ sensory functions in such a way as to have the acts of their own bodies become proxies for the social body under their control.

As discussed in

chapter 2, the master Baha

ʾ ad-Din Naqshband was a stringent advocate of silent zikr that interdicted the use of the tongue or other parts of the body. His primary hagiographer shows him in conflict with those who would use music and dance in their gatherings. He states that when Naqshband was visiting the home of a disciple in the vicinity of a palace one evening, the prince who lived there had invited a party of singers (

qavvalan) who were performing loudly accompanied by dance and ecstatic cries from the audience. Naqshband told his disciples that the wanton behavior was unlawful and the sounds should not enter one’s hearing. He indicated that the solution was to stuff the ears with cotton. As soon as he put cotton in his own ears, the whole company assembled before him stopped hearing the sounds. Later some neighbors inquired of Naqshband’s disciples as to how their group had managed to pass the night in the house, given their opposition to music. When they told the neighbors what had happened, they were so impressed by Naqshband’s powers that they decided to join the ranks of his devotees.

7The hagiography of Shaykh Ahmad Bashiri mentions a case that also involves hearing, but from the opposite direction. This master is shown to have experienced opposition from other Sufis, belonging to a Yasavi lineage, who represented the area’s established Sufi authority. On one occasion his opponents decided to track the master down and cause him physical harm, thinking that they would be able to find his community by hearing their vocal zikr. As it turned out, however, they were miraculously disabled from hearing the sound of the zikr and could not intrude upon the community as it performed its religious exercises.

8While these stories reflect masters’ control over the faculty of hearing, an incident regarding Khwaja Ahrar registers the idea that a person can speak only that which a powerful master is willing to hear. This story pertains to the conflict between Zayn ad-Din Khwafi and his disciple Ahmad Samarqandi, which is discussed in

chapter 3. Ahrar’s hagiographers relate that this master had been sympathetic toward Samarqandi in the context of the fight because of both ideological empathy and the fact that he enjoyed Samarqandi’s eloquence from the pulpit at the Friday mosque in Herat. However, one day, as Samarqandi was giving the sermon, he began to aggrandize himself by talking about his abilities to be persuasive. Khwaja Ahrar found this distasteful since, in his view, the truth was that his ability to articulate things well stemmed from the fact that eminent Sufis were willing to hear the sermons. To prove this point, Ahrar put his head inside the neckline of his garment so that he would not see the man, placed fingers on his ears, and held his breath. Samarqandi was then suddenly dumbstruck, unable to utter a single word no matter how hard he tried. He realized the source of this restriction but was unable to lift it and had to walk away from the pulpit ashamed. No one aside from Samarqandi knew what had come to pass, and Ahrar was able to teach him a lesson by manipulating his hearing rather than his tongue.

9The issue of control brought Sufi masters and disciples into mutually affective relationships. The idea that what was seen and learned in such situations was a subjective experience, limited to the two people involved, is illustrated in a story given by one of Khwaja Ahrar’s hagiographers. He tells of a man who felt slighted by his master because he would ask other disciples to be his confidants but not him. After many complaints, the master eventually told him to come meet him at night in order to participate in a special mission. When he got to the master, he saw him with his hands and feet covered in blood, carrying a sack. He told him that he had just killed such and such a disciple and that now they had to go and bury the body in a secluded place. The man obliged, but, the very next day, he went to the victim’s father and told him the whole story. The father went to the king, and, when they investigated, the body turned out to be that of lamb. The man who had supposedly been killed came forth as well. The master then cut off his relationship with the beseeching disciple because of his inability to submit to the master and keep their mutual relationship confidential.

10In these stories masters are shown to cause their disciples to submit in many different ways: by verbal comment, by the nonverbal exercise of power as in the direction of a gaze, by the displacement or stoppage of sensory functions, by control exerted through a refusal to be the recipient of effort emanated from the bodies of disciples, and by deceiving their senses and mind in order to enforce the larger point of the submission due them. Between these various modes, hagiographers represent great Sufis as absolute masters controlling the bodies of others through the extension of their own corporeal powers.

Mending Bodies

In addition to cases of control over the sensory functions of others’ bodies, Sufi masters are shown to have the ability to heal and mend the bodies of those dependent on them. This is in fact another form of control, extending the masters’ reach from affecting sensory faculties alone to the actual physical shape and working of limbs and other body parts. The most straightforward cases of these include instances such as when Amin ad-Din Balyani was approached by a man whose fingers were paralyzed, and he restored them.

11 Similarly, a lame man came to Ahmad Bashiri saying that he was tired of his disability, and the master restored his leg.

12 In a more extended form, healing properties could be a significant feature of a master’s overall profile. For example,

ʿUmar Murshidi’s hagiographer reports:

When people got headaches, his Eminence—may his Secret be sanctified—would write an amulet (

taʿviz) and tell them to cover it in wax and keep it with them. That was extremely effective. He wrote the same amulet for eye injuries, as has come in the Sahih Bukhari and Muslim. He said that in the case of a pregnant woman close to delivery, when she was ready to begin the birthing process, this amulet was to be dropped in water while covered in wax. Then she was given the water to drink and the amulet was tied to her left thigh. Under this condition, she would give birth without any difficulty.

13

In all these cases, masters act to provide relief from bodily hardships to those who are their committed religious dependents.

Instances of healing also include situations where masters’ powers are presented as acting on the social body through the intermediacy of an individual body. In this regard, Amir Kulal’s hagiographer tells a poignant story that encapsulates miracles’ symbolic capacity to bridge the gap between a person and the community. He states that while Amir Kulal was a disciple of Khwaja Muhammad Sammasi, some people in the village of Sammas had a fight in which a man lost a tooth. The injured party’s group initially thought to take the matter to a judge in order to seek compensation for the injury, but then decided to seek Sammasi’s council. Sammasi asked to see the tooth and handed it over to the young Amir Kulal with the words “My son, do something so that these people get over their conflict.” Amir Kulal took the tooth, placed it in the correct place in the man’s mouth, and prayed to God and sought aid from the spirits of deceased masters. The tooth became attached exactly as it was before the fight, which astonished the injured man and compelled him to forgive those who had assaulted him. The miraculous restoration of the tooth led to the healing of the rift within the community.

14

Protection, Multilocation, and Hypercorporeality

Masters’ ability to protect their disciples in far away places without leaving their own abodes is a pervasive theme throughout hagiographic literature. Great figures such as Safi ad-Din Ardabili, Baha

ʾ ad-Din Naqshband,

ʿAli Hamadani, and Shah Ni

ʿmatullah Vali are all shown to have preserved their disciples’ bodily integrity in crises such as animal attacks, being lost while traveling, and being caught in storms while at sea.

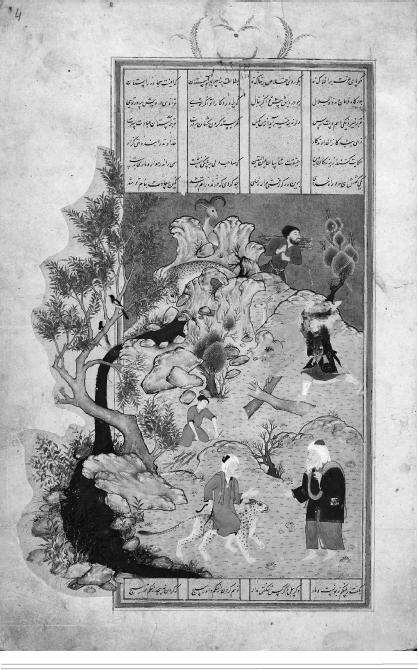

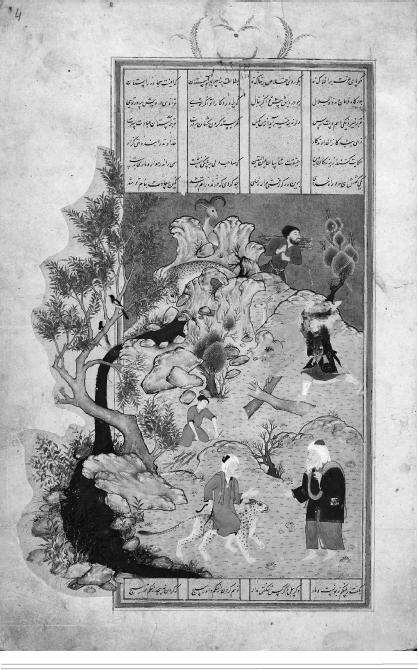

15 This can be seen pictorially in the painting in

figure 7.1 illustrating the story of a Sufi riding a tiger while using a snake as a whip, from a copy of the

Bustan by the great moralist Muslih ad-Din Sa

ʿdi. In the text surrounding the painting, the man riding the tiger advises the one questioning him about his powers to become like the submissive tiger and snake in front of authority that deserves to be obeyed.

16The Mongol and Timurid periods were marked by widespread wars and political instability throughout the Persianate region, and masters are sometimes shown extending protection during sieges and conquests of cities, which involved significant loss of life. In fact, it can be argued that political instability and the associated lack of personal security helped to elevate Sufi masters’ political roles during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. This can be seen directly in the case of a man such as Khwaja Ahrar, who controlled substantial economic resources and acted as a political arbitrator and sometime kingmaker in Central Asia because of his vast influence. The record of his letters to rulers, viziers, and other governmental officials show him working in the capacity of his community’s protector and a guarantor of justice in general. In these letters he is at times solicitous and at others censorious of official behavior, treating his addressees as equals rather than with the tone of an ordinary subservient subject in front of royal authority. His protective role over ordinary people he represented is marked by the fact that they are referred to as servitors (

mulaziman), reflecting an overlap between their religious allegiance as disciples and their status as political and economic clients in need of his sponsorship when required to deal with ruling authorities.

17

7.1 A man riding a tiger using a snake as a whip. From a copy of Sa

ʿdi’s

Bustan. 1525, Herat, Iran. Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper. Text and illustration: 20.6 × 13.7 cm. Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase—Smithsonian Unrestricted Trust Funds, Smithsonian Collections Acquisition Program, and Dr. Arthur M. Sackler, S1986.36.

Like other great masters, in hagiographic narratives devoted to him, Khwaja Ahrar is also shown to be a miraculous protector. In his case, then, the ordinary protection of a powerful political figure is intertwined with the extraordinary security that could be provided by a miracle-working friend of God. Although we do not possess much documentary or archival evidence similar to Ahrar for all the great masters, it can be presumed that the pattern we see in his case applied to them as well, according to the levels of influence they enjoyed among the political elites of the environs in which they operated.

18When it came to providing protection, the theme of Sufi masters’ miraculous ability to multilocate stands out as being emblematic of the situation of Persianate Sufism. While the idea that masters can move and transform their bodies to be present in multiple locations at the same time has roots in early Sufi literature, the possibility was particularly useful in a context where Sufi communities were expanding rapidly and individual masters were considered responsible for the well-being of multitudes of disciples and others. Episodes that depict masters deploying this power most often lead to the cementing of Sufi intergenerational bonds.

In most cases of the use of this theme, male masters are depicted as able to transport themselves long distances instantaneously and be present in multiple locations synchronically in order to carry out their protective duties. Amin ad-Din Balyani’s hagiographer tells the story of a dervish whom the master told explicitly that when a man starts calling people to God his disciples are never absent from him; wherever they go, he aids and protects them. The dervish was somewhat skeptical about this assertion until he decided to go to the Hijaz. One night in Basra, on the way, he went to sleep after a meal, neglecting to use a toothpick or clean his hands and mouth. Close to morning, he saw a dream in which Balyani appeared to him and gave him a toothpick along with the injunction to make up for his lack of proper care of the body prior to falling asleep. He then awoke to find the toothpick with him and realized that “in all situations, the shaykh is never absent from us; being far or near, or present or absent [from view], are all the same to him.”

19The narratives I am utilizing provide varying accounts of the place of masters’ bodies while interacting with those far removed from their own locations. For example, a story about

ʿUmar Murshidi shows him become absent from his location while on such a mission. Once when a group from Kazarun was visiting him, he retracted his head into his shirt below the neckline and kept it there. The men, who were not Sufis, began arguing with each other, some saying that they should leave because he had fallen asleep while others maintaining that it would be rude to depart without taking formal leave. They then probed his robe and turban to realize that these were empty. A little while later, his head appeared from his neckline once again, now with water dripping out from his sleeves. When pressed, he explained that when he retracted his head, Muhammad appeared to him and told him to go to Baghdad to aid four orphan children who had some sheep that were about to drown in the river. He then proceeded to save the sheep and returned them to their owners before returning to his original location.

20Most stories concerned with masters’ long-range abilities portray them with the capacity to be visible in multiple locations at the same time. A story concerned with Naqshband presents this directly when a group of dervishes split up to go various places after being in his company. As it happens, each of the subgroups sees him when they arrive at their destinations and thinks that he must have traveled there from a different route. When they meet up again they become very confused about where to go in order to find him, since people seem to have seen him in many different places. Then a servant arrives asking that they come back to where they had first met with the master. He tells them he had been in the same room with the master the whole time after they’d left, adding yet more mystery to the matter. When they all return to Naqshband and ask him about what they had experienced, he smiles and says, “It is related that one evening during Ramadan, his Eminence [the Khwajagani master]

ʿAzizan [Ramitani] was asked to be at thirteen different places and he honored each request.”

21While in this case disciples known to each other witness Naqshband’s abilities, another prominent theme relating to multilocation is the idea that masters have disciples present in various localities completely unbeknownst to one another. In Naqshband’s case a man reported that when traveling through Simnan he heard of a man known to be a devotee of the master. He made the effort to meet him and asked him how he had acquired his affiliation. The man replied that he had first seen a dream in which Muhammad had pointed to a man of great spiritual form and had told him Naqshband’s name along with the advice to follow him. He had noted this man’s appearance in detail and had written it down in the back of a book along with the date of the incident. Then, many years later, one day, as he was sitting in a shop, a spiritual-looking man appeared, and he was able to recognize him based on the description he had written down. He then asked Naqshband to grace his home by going there. He agreed and walked to it without being told the way and, when there, he proceeded to pick out the book that contained the written description and asked the man about it. Thoroughly convinced of this master’s extraordinary knowledge, the man asked to become his disciple, and the wish was granted.

22The extraterritorial influence represented in this story is a particularly prominent theme in the hagiography of Amir Kulal. During this master’s lifetime, one day a good-looking young man came and sat down at his gathering without a greeting or any other word passing through his lips. After a while, Amir Kulal raised his head and said, simply, “This is the end.” The stranger replied, “There was one hollow left and now that is also hidden.” He then remained in the company for some time, and, when he finally went out to leave, people gathered around him and asked about his rudeness, not asking for leave before his departure. He replied that he had come from Anatolia (Rum) and that Amir Kulal had been building a mosque there and had asked to be informed when it was complete. The disciples showed surprise at this, saying that the master had not been to Anatolia in recent times. He replied that everyone in the vicinity where he lived was a disciple of Amir Kulal and prayed behind him every Friday. He also explained that his greetings and other conversation with the master had been from the heart rather than the tongue. The fact that the locals had not been privy to the possibility of such communication marked them as deficient in knowledge.

23Moving to a different corner of the world, a group from Turkestan once came to Bukhara and began talking about Amir Kulal. The locals asked them how they had heard about the master, given that he’d never traveled there. They said that the master was extremely famous in their parts and that they were all his disciples, had been initiated by him, and would call upon him whenever they encountered any difficulties in life. After his powers had saved them many times, they finally asked who he was, and he replied with his name, leading to further affirmation of their relationship. They then praised Amir Kulal in ways the locals had never considered until this time.

24In a third instance of this sort, the hagiographer relates that after Amir Kulal died a group of Sufis from Mecca and Medina arrived in Bukhara and headed to Sukhari, the master’s abode, asking for him. When people told them he had died, they said they would go and see his children. There they were asked how they had known Amir Kulal since he had never traveled to the Hijaz and they had never before been to Sukhari. They said that they were disciples of Amir Kulal, as was everyone else in Mecca and Medina, and had followed behind him circumambulating the Ka

ʿba for thirty-two years. This year he had not come to lead them, which had compelled them to seek him. They then visited his grave, mourned his passing, and eventually took leave of his descendants. In parting, they expressed the regret that no one in Amir Kulal’s vicinity quite understood his greatness.

25These stories about Amir Kulal have two particular lessons built into them that reflect the deployment of the multilocation theme. By invoking the idea of masses of followers in Anatolia, Turkestan, and the Hijaz, the stories overcome the master’s handicap, that he spent his whole life near the city of Bukhara in Central Asia. This must have been an important concern for those who sponsored the hagiography since, by the time the text was produced, the pace of institutionalization among Sufi communities in Central Asia had increased considerably. Particularly in comparison with competing groups such as the followers of Bahaʾ ad-Din Naqshband, it was in the interest of Amir Kulal’s successors to show him as having a following that extended far beyond the confines of his abode during his life. Simultaneously with this projection into the field of inter-Sufi competition, all the visitors are made to chide those who had spent their lives in the vicinity of Sukhari for not adequately appreciating Amir Kulal’s powers and spiritual worth. These stories can then be read as injunctions to the audience to evince greater confidence in the patronage on offer from Amir Kulal’s descendants.

It is important to note that, in these stories, masters are shown to present themselves physically rather than merely extending their protection by manipulating the environment to affect disciples or avert danger for someone. This power to multilocate is an especially advantageous hagiographic device when arguing for the breadth of influence of particular masters while constructing their hagiographic personas. Acknowledging masters’ powers to project themselves through space and time in this way allows them to override limitations placed on ordinary bodies.

Life and Death

Accomplished Sufis’ ability to kill and resurrect human beings represents the most dramatic enactment of the theme of corpses in morticians’ hands in hagiographic sources. This is a fairly common subject in the literature, and the power is attributed quite unproblematically to the famous masters. Narratives that show masters exercising this ability are invariably concerned with a larger point having to do with ideological or social matters. As I argued at the end of the last chapter, hagiographic representations of masters’ abilities to perform miracles never depict them overturning material causality in the abstract. They are shown to exert such powers either while asserting themselves against rivals, or in the context of specific relationships with other individuals whom they are obligated to protect or chastise. This pattern is equally true for miracles of bringing the dead back to life and the provision of food.

ʿAli Hamadani is shown to have traveled widely throughout the regions that are today classified as Middle East and Central and South Asia, and is regarded, to this day, as the force behind the Islamization of Kashmir. His hagiographer Haydar Badakhshi tells a story that includes the theme of bringing the dead back to life in conjunction with conversion to Islam, although the venue for this is described as a Christian habitation near the “Land of the Franks” rather than India. When passing by this village he is shown to inquire from the inhabitants as to why they had not converted to Islam. They reply that they considered their religion superior because their “prophet,” meaning Jesus, could make the dead come back to life and that if they ever came across someone able to do this in their own times they would convert to the religion of that person. As Hamadani hears this, an unseen voice (

hatif) tells him that he might have this power if he wished. He proceeds to the graveyard and is able to rouse dead bodies, which leads the village to convert to Islam.

26

While this story affirms Hamadani’s role as a proselytizer, a different narrative in the same source deploys the theme of quickening a dead body in the arena of interpersonal relationships between a master and a community. One day, as

ʿAli Hamadani was sitting inside a mosque, the dead body of member of the local nobility was brought into the courtyard for funeral prayer. Someone in the party went in to see Hamadani and asked him to lead the prayer for the sake of the man’s afterlife. The shaykh replied that there was no reason for this because the man was still alive. The man remonstrated that he had died the night before, and, by the time Hamadani went outside to check, the funeral prayers had been performed and people had taken the body away to the grave. Upon reaching the graveyard, Hamadani had the people reopen the grave and then told the dead man to rise, which he did immediately, walking away. When people asked the man the meaning of it all, he told them that the members of his family were disciples of Hamadani, but he had spent his whole life committing sins. The angel of death had then appeared and taken away his life before he could repent his bad deeds. Hamadani brought him back to life since no disciple of his could be fated for eternal punishment. To fulfill this destiny, the man lived for twelve more years and spent every moment in acts of worship.

27 This story illustrates the notion that Sufi masters’ reputations and the acts of their disciples were thoroughly interdependent matters.

The full cycle from life to death and then back to life is represented as being under the control of a great master in some instances. Khwaja Parsa reports that Baha

ʾ ad-Din Naqshband told him that while he was still a novice on the path, he once went into the desert with another dervish where they discussed many things. At one point, the conversation came to the quality of servitude (

ʿubudiyyat) and abandoning one’s self (

fida) that can characterize a Sufi. The dervish asked about what the limit of such dedication could be, and Naqshband replied that if a dervish is told to die, he dies instantly. After he said this, he was overcome by a feeling and looked at the dervish, commanding him, “Die!” Instantly the man fell down, and his spirit left his body. From morning to midday, the dead body lay there in the sun while Naqshband himself went off to find shade because it was a very hot day. When he went to see the body, it had begun to change color because of the heat. Then another feeling came over him, and he commanded the body, “Come alive!” After he said this three times, the man’s limbs began to move and he raised himself, fully alive. Naqshband then went to Amir Kulal, his master, and told him this story. When Amir Kulal inquired as to why he had eventually told the body to come back to life, he replied that he had been compelled by an intuition (

ilham).

28Among prominent shaykhs, Naqshband comes across as being particularly adept at giving and taking life. In the story I have just recounted, his command establishes the credentials of the second man by showing that he could implement servitude to the point of death. In other stories Naqshband is depicted as punishing disciples by commanding them to die. He once asked a disciple a question, but the man failed to respond. Becoming angry, Naqshband then shot him a look that made the disciple fall down and die. Other disciples present at the moment felt pity for the man and interceded on his behalf. Naqshband then made him come back to life by putting his feet on the dead man’s chest. He repented from his rudeness, and the master asked him to jump into a pool of water. When he did so, he said he saw his whole field of vision saturated with light.

29Naqshband once made a dead man come alive by simply telling the body, “Come to life, Muhammad.” Exerting greater effort on another occasion, he put his feet on the chest of a dead man to bring him back and later said that he had had to travel to the fourth heaven to catch up with the man’s spirit and bring it back down to earth to unite with the body.

30 Extending the theme of giving life in a different direction, Naqshband is, like other masters, credited with being able to grant people’s request for children. Once someone came to him who had had ten children die from various causes. Naqshband offered prayers that led to the birth of a daughter who, however, became very sick. The master then asked the parents to provide a sheep as a kind of substitute for the child’s life, after which she recovered and lived a long life.

31 Similarly, a woman once asked her husband to give Naqshband some coins to distribute as alms without indicating a direct wish. Upon receiving these, Naqshband smiled and told the man they exuded the smell of a child and he would soon have one. The hagiographer reports that a child was indeed born and was actually present in company when this story was related to him for the sake of including in the hagiographic text.

32Between the stories I have related so far in this chapter, Sufi masters are shown to be able to affect all the different functions a human body is presumed to possess while being present in the world. They can control disciples’ sensory perceptions, heal or regenerate limbs and organs, guarantee the integrity and dignity of their bodies under adverse circumstances, willfully take away and endow life to bodies, and extend their presence in the world by granting children. Seen from the side of masters, these processes imply the capacious abilities of their own bodies to intervene on others’ experience of being in the world. But when seen from the side of disciples, these themes imply the tying up of their individual bodies to that of a master able to extend himself simultaneously in multiple arenas. Since disciples are the ones who composed hagiographic literature, highlighting this theme shows the texts as annals of their own corporeal submission at the hands of the masters. In the remainder of this chapter, I explain why Sufis in the Persianate context found it useful, and even necessary, to portray themselves as hapless corpses in the hands of masters.

MASTERS AS CORPSES

The hagiography of Shaykh Ahmad Bashiri tells a story involving death positioned at the beginning of the master’s Sufi career. The author states that the master himself said that once, during warm weather, he acquired an unrecognizable disease that made his body start to smell extremely bad. The odor was so horrendous that even his relatives gave up coming near him, and he found himself sitting in the wilds under the sun, not possessing enough strength to move to shade. All who walked by would cover their noses with their sleeves, and no one would give him any water or food. He then sensed that he had no one left near him, whether in the exterior or the interior world, and he passed out, losing any sense of the difference between night and day. But he eventually recovered from this illness and realized that it had caused him to become completely free of the created world. The experience meant that everything had washed away from his heart save God.

33This and other similar stories told of Sufi masters convey their acquiescence to Muhammad’s command to “die before you die.” The prophetic injunction is aimed at advocating a separation from the cares of the world and can be interpreted metaphorically, as is usually the case, or enacted physically, as seen in Shaykh Bashiri’s example. Inasmuch as great masters are supposed to have reached ultimate Sufi goals, stories such as these imply that they are to be seen as beings who have undergone deaths and rebirths within their lifetimes. The working of this process is, in part, what makes their bodies special: their extraordinary powers, exhibited through miracles, derive from the fact that they are seen as being dead in ways that ordinary bodies are alive and living in ways that other bodies are dead.

34 If such is presumed to be the case, hagiographic narratives that describe moments when masters leave the physical world for good hold special interest as points of analytical concentration for understanding the metaphysical and social functions of saintly bodies.

As studies of death and bereavement have highlighted, the passing away of a human being is a thoroughly social event that implicates multiple bodies. Save for situations of mass death, the presence of a dead body has a profound effect on those who surround it.

35 At the moment of his permanent death, the Naqshbandi master

ʿAla

ʾ ad-Din Abizi is said to have briefly regained consciousness and heard the weeping of women. When told that they were doing so because of his condition, he is said to have told them to rejoice instead since, for someone like him, death represents final union with God and is a moment of accession to the greatest happiness.

36 A man named Shams ad-Din Bukhari is described as having prepared himself for his death by wearing his best clothes and digging his own grave before telling his companions, “The time for my departure has arrived; when I go into seclusion, stay close until I say ‘O He’ three times; after that, start the work of washing the body and putting on the shroud.”

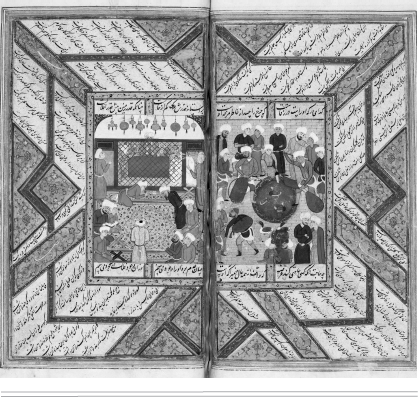

37The different processes that are put into motion upon death are presented in a painting with very fine details that dramatizes a story in Farid ad-Din

ʿAttar’s classic

Conference of the Birds (

figure 7.2).

38 Here a Sufi master counsels a man lamenting at the funeral of his father to the effect that death is inconsequential in the larger scheme of things and that it is more significant to concentrate on what one does while one is alive. The painting contextualizes the dead body, hidden inside the coffin, by surrounding it with living ones of various ages and comportments. Whether in this image or in the stories I have cited earlier, the narration of death conjoins the state and perspective of the dying person with the actions and attitudes of those who are to live with the fact of the death. Although the narratives provide a contrast between the two sides, the texts and the painting convey varying investments held by the dying person’s successors.

I will discuss hagiographic representations of death by concentrating on narratives regarding Safi ad-Din of Ardabil and Khwaja Ahrar. These two cases are exemplary, but for different reasons. The work Safvat as-safaʾ, concerned with Ardabili, contains the most extended account of a master’s death, encompassing themes that are found piecemeal in other narratives. And Khwaja Ahrar’s death is represented in three different sources with slight but highly meaningful variations. Juxtaposing these narratives highlights the fact that, in representations of death as in other cases, awareness of the eyes and pens that mediate the event for later observers makes a significant difference for analyzing hagiographic material.

7.2 A son being consoled at his father’s funeral. From a copy of

ʿAttar’s

Mantiq at-tayr. Bihzad, circa 1487–88. 19.7 × 14.6 cm. Image copyright © Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Fletcher Fund, 1963 (63.210.49).

Final Illness, Death, and Cataclysmic Repercussions

The author of the

Safvat as-safaʾ narrates Shaykh Safi’s last illness and death by relating accounts by a number of different prominent disciples. His chief witness is the master’s son, Shaykh Sadr ad-Din, who not only succeeded his father as the head of the religious community but was also the specific sponsor of the hagiographic compilation in question. Shaykh Safi is said to have endured a protracted final illness of bladder constriction, which the hagiographer links to his youthful habit of holding urine for weeks at a time so as not to exit a state of ritual purity. His master, Shaykh Zahid, is said to have told him to desist from this practice, because it would likely cause great pain in his old age, but he is shown to have continued it.

39The significant duration of Shaykh Safi’s illness allows the hagiographer to depict him interacting with a number of people, providing details of the transition occasioned by his demise. The author relates, from Sadr ad-Din, that when his father had been ill for a year and two months, he thought to himself that perhaps he was not close to his death since it was reputed that the passing away of great masters threw the world into imbalance because of the vacuum left behind them. When he inquired of his father, he replied, “My son, after me you will see things that no eyes have seen before and hear that which no ear has heard before.” This was proven after his death with a number of calamities: a famine came to grip the world and people were driven to eat cats, dogs, and dead bodies; political upheaval led most of the population of Azerbaijan to be exiled and villages and cities to be destroyed; a plague devastated the population for many years such that many thousands of dwellings stood empty for want of owners.

40In the personal sphere, Sadr ad-Din is shown to say that he was absolutely distraught over his father’s death, thinking that all his relatives and friends would turn against him and he would lead a miserable life without any supporters. As a result of these thoughts, he contemplated eating poison to destroy himself, but the father divined his troubles from his face and told him that if loneliness and trials did come, they would be a kind of patrimony for him since his father and (maternal) grandfather had not led an easy life. He also pointed to his own illness as a case in point, saying that whenever physicians were able to lessen his pains God sent more terrible ones since this kind of affliction was the mark of his status as an ardent lover of the divine.

41For the last two days of his life, Shaykh Safi had nothing but Quranic phrases on his tongue. The death itself occurred after the morning prayers on Muharram 12, 735 (September 12, 1334 CE). As the body lay on his bed, his wife Bibi Fatima, who was the daughter of his own master, asked to see him for the last time and gave the men her father’s waistcoat and two turban sashes she had woven to be put on the body before it was buried. Eighteen days after the master’s death she herself passed away as well. As the body was prepared for burial, it exhibited miraculous powers like lifting the arms by itself, and one person carrying the coffin to the grave realized that it was being held up by itself in air without burdening anyone. He was buried in the room where he used to dance during musical auditions since this is where his body had gone into ecstasies while he had been alive. Even before Shaykh Safi’s death, people reported having seen thousands of spiritual beings (

ruhaniyyun) sitting outside this room waiting for its eventual sanctification with the body’s interment.

42Hagiographic narratives regarding Shaykh Safi present his son Shaykh Sadr ad-Din as the sole preeminent successor to the great master’s mantle. Among episodes I have cited, Sadr ad-Din’s desire to destroy his own body while seeing the gradual demise of that of his father makes the two appear fundamentally connected to each other. Shaykh’s Safi’s statement that bodily pain of the type he was undergoing at the time was a kind of inheritance for both of them emphasizes this identity even further. The close connection between the narration of death and succession can be seen even more clearly in a case such as that of Khwaja Ahrar where we have testimonies from the perspective of many different disciples.

Successors at Deathbeds

Ahrar’s son-in-law, disciple, and hagiographer

ʿAbd al-Avval Nishapuri relates that the master, a few months before his ninetieth birthday, was stricken with acute diarrhea, which caused severe weakness and forced him to be bedridden while in Samarqand, away from home. During three months of illness, he made special efforts not to miss any prayers despite his fragile condition. On the last day, as Nishapuri sat next to him, he opened his eyes and asked who was there. When someone else who was present said Nishapuri’s name, he extended his right hand and grabbed him. Nishapuri says that, in hindsight, that was his parting handshake. He died toward the end of Rabi

ʿ al-Avval 895 (February 1490).

43In the second narrative regarding Ahrar’s death, Mawlana Shaykh reports that, on the last day, the master wished to issue a testament. When this occurred Nishapuri was sitting on one side of the room, Ahrar’s son Khwaja Kalan was on the other side, and the narrator himself was behind the head side of the bed so that Ahrar could not see him. He raised his head and asked who was there. People responded that it was the Khwajagan and nobles (

amiran). He then asked who else was there. They then said Mawlana Shaykh’s name, and Ahrar insisted that he come in front of him rather than sitting behind. He then proceeded to give very detailed financial instructions regarding the construction and maintenance of a

madrasa that had been in planning stages at the time. The author writes: “From the beginning of the testament to the end, this wretch was his addressee. It occurred to me that the Khwajagan and nobles may not like it that all this was said to me. Becoming aware of this [thought in my mind] from his great nobility, he [Ahrar] screwed up his face and said, ‘Now they are with us as well; whatever comes to someone’s mind he should say it.’ No one knew why he said this, but the reason was that the thought had arisen in the mind of this wretch.”

44 As in Nishapuri’s case, this account is constructed carefully to show the closeness between the master and the narrator. First, he places himself at the location and shows that Ahrar was able to discern his presence, even though he could not see him physically. Then the testament is addressed to him. Finally, the special connection between the two is shown through Ahrar’s ability to divine his thoughts to the exclusion of others who were present.

The third account of Ahrar’s death available to us comes from

Rashahat-i ʿayn al-hayat, whose author, Fakhr ad-Din Safi, does not represent himself as having been present by the master’s side when he passed away. The first part of his report is virtually identical with the account of Nishapuri previously discussed, except that he attributes the words to a disciple named Mawlana Abu Sa

ʿid Awbahi, who is described as having been his companion throughout the illness and the last moments. Safi makes no mention of the presence of Nishapuri or Mawlana Shaykh at the scene. He then goes on to say that, right at the moment when Ahrar died, the city of Samarqand witnessed a severe earthquake, and those who were aware of Ahrar’s illness knew immediately that this was an indication of his death. Those present where he lay said that just before his spirit left the body they saw an extremely bright light come out of the space between his eyebrows and completely overshadow all the candles burning in the house. The rulers of the area rushed to the scene to aid in preparing the body for the funeral, and Ahrar’s descendants constructed a lofty shrine over the grave after the burial.

45The most interesting information to be gained from comparing these accounts of Ahrar’s death has to do with the bodies of the authors rather than the dying man. Nishapuri was an intimate companion of the master, and his account emphasizes the latter seeking corporeal contact with him before life escapes his body. This is not a mere incidental detail, because Safi’s report is identical, save that it makes no mention of Nishapuri’s presence or the handshake with Ahrar. Moreover, Nishapuri’s account conveys the impression that he alone was present at the critical moment, whereas Mawlana Shaykh shows the presence of a large group that includes Ahrar’s son and the author himself. Clearly, then, Nishapuri’s version is carefully constructed to emphasize his own position relative to the dying master as well as the survivors. His portrayal of the matter constitutes an argument aimed at legitimizing his own claims as a successor.

Mawlana Shaykh was not as close a companion to Ahrar as Nishapuri, but he is also compelled to insert himself in the scene. As the author of a text on the master, his presence at the time of his death is an important factor for legitimizing his narrative. Moreover, of all hagiographic works concerned with Ahrar, his work provides the greatest amount of details on the master’s economic engagements. This emphasis gets reflected in the death narrative as well, since Ahrar is shown giving very precise instructions regarding a major public project. His modulation of the death narrative is therefore closely tied to the general tenor of his work.

46 Similarly, Safi’s account also matches the overall purposes of his work. The

Rashahat’s extensive description of Ahrar’s life is keyed to portraying him as an extraordinary man of the age and contextualizing his life within the Naqshbandi lineage. Safi eschews espousing the cause of any particular successor, showing, instead, Ahrar’s significance as a cosmic figure and one whom society’s elite felt compelled to honor.

Themes found in narratives concerned with the deaths of Shaykh Safi and Ahrar appear piecemeal throughout Persianate hagiographic literature.

47 The two most prominent features of these accounts are the idea that masters’ deaths cause imbalance in the world and that those designated to succeed to the master are present at moments of death to show transfers of authority. Both these aspects of death narratives contain ramifications for the authors and sponsors of these texts. The issue of imbalance begs the rise of someone who can correct it so that the hierarchy of God’s friends readjusts and remains the mechanism through which God maintains the world. There can be no better substitute for the dead master than someone who can claim to be his direct successor. For the succession to be fully valid, however, it has to be ratified through close connection to the master, which is best shown by placing the two bodies in question in close proximity as one ceases to live and the other takes its place.

Narratives about great masters’ deaths are optimal places to see disciples handling masters’ dying or dead bodies, metaphorically as well as physically. As I suggested earlier, the idea that disciples are the real morticians applies to the whole hagiographic genre, including the stories where masters are shown as great and powerful beings. However, the permanent death of a master’s body marks a significant transitional moment within hagiographic narratives’ internal logic. To see this, we will consider, quite briefly, the functioning of Sufi shrines in the Persianate context.

Embodiment and Enshrinement

The foundation of the city today known as Mazar-i Sharif in northern Afghanistan is an intriguing episode in the religious history of Persianate societies during the fifteenth century. The city’s name means “the noble shrine,” referring to the purported grave of Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law ʿAli, which became “manifest” at this site first in the twelfth century CE and then again toward the end of the fifteenth century. This is somewhat enigmatic since ʿAli died in Iraq and his shrine in Najaf has been a well-known place of pilgrimage from early Islamic times.

Historical improbability notwithstanding, the surprising appearance of a second grave in 1135 CE is said to have led to the construction of a shrine, which had fallen away from the public eye by the fifteenth century. The grave’s rediscovery in 1480–81 precipitated the construction of a new shrine under the patronage of the Timurid king Husayn Bayqara. This fifteenth-century shrine is commemorated in the city’s name and has been central to the settlement that has continued on to the modern city. The shrine has already received significant academic attention, and, for the present purposes, I will focus on representations found in a short treatise on the rediscovery written by

ʿAbd al-Ghafur Lari.

48 A disciple of

ʿAbd ar-Rahman Jami, Lari also wrote a hagiographic text on his master that was meant to continue Jami’s own extensive dictionary of Sufis.

49 Lari’s contextualization of

ʿAli’s shrine in a Sufi idiom provides a useful example to understand the formation and functioning of such monuments in the Persianate world during the fifteenth century. I have chosen to highlight narratives about this shrine in particular because of the way they illustrate the

discontinuity between bodies and shrines.

Lari begins his work with extensive praises of

ʿAli and then goes on to state that, in the reign of Husayn Bayqara, the grave was discovered through the mediation of Shaykh Shams ad-Din Muhammad, a descendant of the great Sufi master Bayazid Bistami. This man had found a book in a library in India that contained the story of the original discovery of the grave. According to this, in 1135 CE, four hundred people saw dreams in which Muhammad told them that

ʿAli’s grave was located in the village of Khayran, in the Balkh region. The dreams compelled the local ruler to consult scholars, of whom all except one gave the opinion that the dreams must be true because Muhammad is reported to have said that Satan does not have the power to impersonate him in dreams. The one naysayer protested that

ʿAli had died in Najaf, very far from the region, and it was impossible that the body could have been brought there for burial. However, the next night this jurist saw himself beaten and berated by sayyids under

ʿAli’s own supervision in a dream, causing him to change his point of view. The ruler of the times then ordered an engraved epitaph prepared for the site and had a building constructed over the grave. This grave and epitaph reappeared in 1480–81 when Shaykh Shams ad-Din was able to convince the governor of the region, who was a brother of Husayn Bayqara, that the site should be reexcavated. The shrine’s location was rationalized through the idea that, although

ʿAli had died in Najaf, the body had been moved to the location in Khayran around the middle of the eighth century in order to protect it from possible desecration by enemies of

ʿAli and his descendants, the Umayyads.

50Once the news of the manifestation of the shrine spread, it became a major center of pilgrimage for people, coming from near and far, who poured offerings into the hands of the shrine’s caretakers. Lari’s florid verses in praise of the shrine state:

Noble tomb, to you belongs the sanctity of all sanctuaries.

Your location is the qibla of Arabs, the Kaʿba of non-Arabs.

Compared to its brilliance, the sun and the moon are mere candles.

Heaven’s back stoops as it bends down to kiss its lights.

In its spirit-nurturing dust are inscribed cures,

its spirit-scattering floor the place to smash all sorrows.

Creation takes refuge at its threshold.

Time swears by the dust of its court.

From the manifestation of this garden, abode of the angel of Paradise,

dust of the earth of Balkh has become the Garden of Iram.

What to say of a human being who comes to this noble place,

a speechless stone would lose its fault of being dumb.

For anyone who has passed through this sacred shrine,

the sky is a feeble lamp, equivalent to twilight.

51

This description emphasizes the shrine’s status as a place of cosmic significance, deserving to be treated as the focal point of rituals. It also bears a close connection to corporeal well-being because of its healing qualities. And, in the manner of the description of other mausoleums in the Islamic context, the shrine is portrayed as a piece of heaven on earth because of the special character of the person buried in it. Immediately after providing the poetic tribute, Lari writes that, once the shrine’s miraculous powers had been confirmed through the appearance of a continuous stream of extraordinary events, the king Husayn Bayqara himself went to the shrine and circumambulated it, treating it with the greatest deference. The king’s decision to do so is memorialized in a verse by Lari that inverts the normal order of things by presenting those who are living as dead and the abode of the dead body as the fount of life:

Jesus has become apparent, why should I be dead?

I am a blooming tulip, why should I appear wilting?

52

In later years, Bayqara’s government relied heavy on revenues generated by the shrine and also promoted it as a pilgrimage site preferable to Mecca for the region’s inhabitants.

53As presented in Lari’s work and corroborated by other sources, the phenomenal efficacy of ʿAli’s shrine at Khwaja Khayran derived from the confluence of three elements: the promulgation of a story regarding the site that was justified through textual referents, the attribution of healing characteristics to its physical constituents, and investment in its reputation on the part of religious and political elites that made the shrine a source of legitimacy as well as revenue. Notably, what was needed for the shrine to be established was not a freshly dead body but narratives about a body whose prestige mattered to those who sponsored the shrine and were its patrons. In physical terms, the earth and buildings surrounding the grave seem to have held powers similar to those ascribed to the bodies of great masters during their lifetimes. The deployment of these powers now depended on those who held religious and temporal authority over the shrine’s physical space. There is, therefore, a close connection between stories regarding shrines and the interests of caretakers, which parallels the case of the contents of hagiographic texts and the interests of their sponsors.

A great number of shrines were erected over the graves of dead Sufis during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries in the Persianate area, including most of the great Sufi masters I have discussed in this book.

54 At least in part, the efficacy of the sites where these were constructed derived from the notion that sanctity had seeped into their physical elements through the masters’ presence. One source likens this to the practice of some masters even during their lifetimes: before assigning a room to a disciple, they would go and pray in it themselves to make the space favorable for the disciple’s endeavors.

55It should be noted that there is no absolute one to one correspondence between the reputation of a master and the scale of a shrine built for him immediately after his death. If and when shrines would be constructed and become focal points for visitation and patronage depended ultimately on the confluence of masters’ reputations and the interests of those willing and able to sponsor them. Overall, then, what matters is that shrine construction and visitation were significant cultural preoccupations in this historical context as a whole. As in the case of the great masters’ personalities, the reputation of a shrine depended, in the last instances, on the production of narratives about the site that could well add to the posthumous reputation of masters but were also independent venues for socioreligious elaboration. The shrine of ʿAli at Khwaja Khayran exemplifies this since its rejuvenation as a pilgrimage site did not require the presence of a dead body. What mattered was the production of a compelling narrative, backed up by the interests of those in power. The shrines can then be seen as new physical manifestations—new “embodied” forms—that were first justified through narratives about their material connection to saintly persons’ bodies but then took on lives of their own in new symbolic and ritual contexts.

HAGIOGRAPHIC NARRATION AND SOCIOPOLITICAL INTERESTS

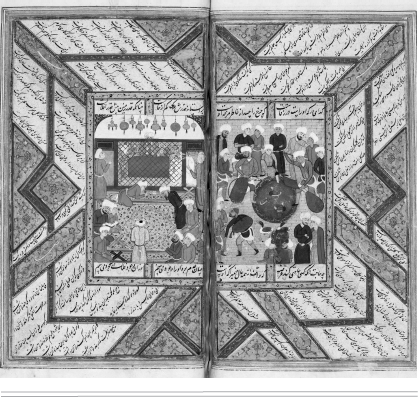

Figure 7.3 contains a painting from a mid sixteenth-century copy of the

Divan of the famous poet Ahli Shirazi (d. 1535–36) that depicts the types of corporeal behaviors one could expect to see around great Sufi shrines. Two couplets surround the painted panel that contains the grave:

(top)

On the threshold of his value, the realm of Mulk is less than dirt.

Its measure is the value of earth in comparison with the heavens.

(bottom)

The world is nonbeing, I see him as being.

In front of that being, I see the sky in prostration.

In the image, the grave hides a body that is deemed more precious than the multitude of living bodies that surround it. The grave is separated from the main chamber by a grill, over which hang various vessels. Behind the grill, two men and two women touch the grave and hold their hands in praying postures. In the main chamber, eleven male figures are shown praying, prostrating, reading, and sitting respectfully. The words of the verses invert the value placed on life versus death by tying the matter to apparent versus hidden truths, the dichotomy central to Sufi ideology. The inscription and the scene together present a community in which the living are tied intimately to the dead through devotion directed at the shrine.

56Scenes such as these correlate to hagiographical stories in which the great Sufi masters are shown continuing to act upon the world after their deaths. In some such narratives, masters expect visitation to their graves from disciples in the way this should have happened during their lifetimes. Once when

ʿAla

ʾ ad-Din Abizi agreed to undertake an errand while on the way to visit the grave of Sa

ʿd ad-Din Kashghari, the dead master complained to a later visitor that Abizi had not come exhibiting complete devotion.

57 From a different angle, when Mawlana Qazi visited a shrine without permission from Khwaja Ahrar, his living master, he felt he was about to die because of being guilty of incomplete faithfulness.

58 In both cases, the stories emphasize obedience due to the masters, dead or alive, whom one has chosen as one’s guide.

We can observe the underlying social functions of such stories by considering an episode from the extensive section (running to ninety printed pages) devoted to Shaykh Safi ad-Din Ardabili’s posthumous actions reported in his hagiography. The general tenor of the material given here can be seen from the following story: a disciple of Shaykh Safi reported that a man in the vicinity of Ardabil had started an unjust dispute with Shaykh Sadr ad-Din, Shaykh Safi’s son and successor. At the time, another man saw a dream in which Shaykh Safi asked him to tell the disputing man to desist from his actions or he would be made to resemble an obedient buffalo with his eyes popping out of their sockets and all his relatives abandoning him. However, the man paid no heed to this warning and continued with his fight. Soon thereafter, all the organs of his body began swelling up so that he began to resemble the form of a buffalo. This caused such tremendous pain that he was incapable of even using a knife to end his own life despite having the desire to do so. All his relatives abandoned him, and, eventually, the swelling and pain reached such dimensions that his eyes fell out of their sockets, causing his death.

59

7.3 Prayers inside a shrine. From a copy of the

Divan of Ahli Shirazi. Circa 1550, Shiraz, Iran. David Collection, Copenhagen. No. Isl. 161.

This story illustrates what I have argued about the interrelationships between dead masters and their successors and hagiographers. The exemplary punishment meted out by Shaykh Safi is meant to benefit his successor, the man who commissioned the hagiography that is our source. Inside the story, Shaykh Safi is able to transform a living body at will, although he is himself no longer present in an embodied form. But seen from a sociopolitical perspective, the story advances the interests of the successor. We can surmise, therefore, that the hagiographer sponsored by the successor is utilizing the memory of Shaykh Safi to affirm the authority of his successor, who is his own benefactor.

Throughout this chapter, I have attempted to elicit the power relations observable in Persianate hagiographic literature by considering narratives from within as well as without the frames of their internal logic. From the inside perspective, masters’ miraculous power to give, preserve, and withdraw life while defying space and time is a significant feature of this literature. This is precisely the quality of the literature that is responsible for its dismissal by historians as a repository of information that could be valuable for representing the past. However, as I have shown through my interpretations of narratives about the deaths and afterlives of the great masters, hagiographic representations contain significant information when we see them as expressions of authors’ particular interests. Stories like the one in which Shaykh Safi causes the destruction of the body of a recalcitrant person show the exercise of power between multiple generations of men. By treating the theme of corpses in morticians’ hands as a discourse concerned with power relations, we can appreciate these materials as important sources for understanding the development of ideas as well as communities in a social context where Sufism was a deeply influential paradigm.