5.

Permissioned

Coordinating with Individuals to Give Them What They’ve Asked for, on Their Terms

Take a look at your inbox: there’s almost nothing, not even in a promotions tab, that was directly delivered to you without some sort of permission granted by you (wittingly or not). The second element of the context framework, permission is a power all consumers now have that gives them control over who has access to them directly. It is a mechanism—which ranges from checking a box to providing personal data—by which an individual actively chooses to receive communication from a brand or its representative.

People use permission to further customize what they see on their screens each day, and to cut through the tremendous noise of the infinite era. Breaking through and driving interactions that will make your brand available in the two most efficient ways (direct or organic), as described in the last chapter, requires permission. It’s the foundation for reaching higher levels of context, and consumers grant it in one of two forms.

Permission Is Either Implicit or Explicit

Permission is not new; it is something marketers have focused on since Seth Godin’s breakout book in 1999, Permission Marketing. In his best seller, Godin focuses on the notion of permission via email. While email remains important, in the infinite media era there’s a wide range of permissions we marketers must seek.

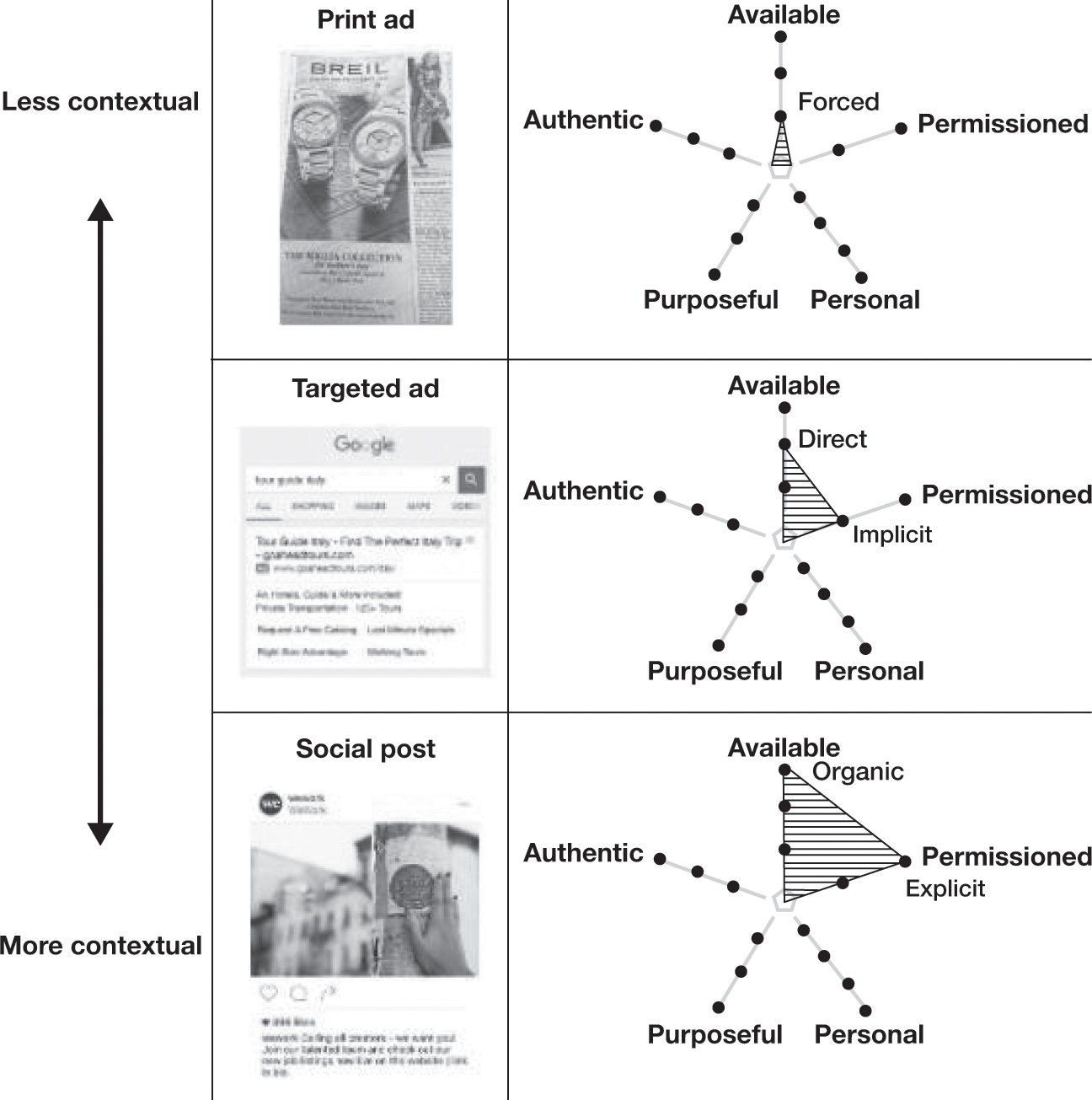

Like the other four elements in the framework, permission levels lie along a continuum. Implicit permission sits closest to the center as least contextual (see figure 5-1), and explicit permission lies at the outer edge—the highest level of context, expressly granted by an individual and most desired by marketers. When you lack permission to communicate with users of a media channel, your brand experiences are tantamount to forced ads, which as we learned in chapter 4 have very little context, if any.

The context framework (permissioned)

People grant implicit permission when they engage with your brand before you’ve reached out to them. For example, a person who visits your site is implicitly allowing you to access his or her personal data to create a more personal experience, although the person is not actively giving you permission to reach out to him or her on another channel. Consumers are aware you are tracking them, and an Accenture study found 83 percent of retail consumers are happy to passively share personal data that allows brands to create a better experience for them.1

Traditionally, brands are implicitly able to access one of three kinds of data: first-, second-, or third-party data. First-party data is any data the brand owns, which could be created in a host of ways. It could be browsing history created by the individual while on the website, information the individual shared in a form, or past purchasing history. Second-party data is someone else’s first-party data that the brand buys to augment its own data, allowing the brand to create richer experiences. Finally, there is third-party data, typically purchased from a large data provider or data exchange. These exchanges combine a mass amount of data from many sources to show a more complete picture of each consumer. The data isn’t able to identify a person by name, but it could tell you that the person on your website right now is forty-five, from Texas, and an avid golfer looking to buy an SUV in the next sixty days. All three data types are passively created and do not require the individual to take action for the data to be generated. Many consumers don’t mind allowing brands to collect and use this data because it is leveraged to create a better experience in that moment. That’s the major difference between implicit and explicit permission. Implicit permission grants a brand the ability to use personal data in the moment, but it does not parlay to direct outreach; for that you need explicit permission, which allows continuous communication and a greater range of context to be created across channels. Explicit permission can be granted in different ways too. Individuals could give you their email addresses when filling out a form and checking a box that it is OK to communicate with them via the channel. On social media, “liking” your brand or giving it a “follow” does the same.

Explicit permission also provides brands with reliable reach. When an individual gives a brand or its representative explicit permission to communicate, you’ve upped the context of your relationship considerably, and your chances of getting your brand experience through are almost guaranteed. Direct messages on channels such as email and Facebook Messenger are reliable, although they might be placed in a separate folder. Such messages are definitely more reliable for getting your experience delivered than posting on social media, which has only a 1 percent reach. But there’s one other big key that context marketers should focus on when it comes to using explicit permission: direct engagement via social channels. The power of social media isn’t free publication; it’s personal connection. Each person has the ability to directly engage with anyone else, and as brands we must learn to embrace this. Mass publication was where we came from—personal connection is the way forward.

Brand experiences on social media are seen by only a very small portion of your followers because of the sheer number of media circulating in the infinite era. (This is likely the reason there are no more “Like Us on Facebook” signs littering the landscape.) Gaining a following is still important, but more important is that your marketing department gain explicit permission to engage with individuals, providing your brand with reliable reach. This is the new frontier of marketing, and it’s how brands are able to reach higher levels of context in the lives of their customers and soon-to-be customers.

Such individual interactions might sound way too granular or intrusive, but they are 100 percent reliable and provide deep value to the consumer. Consumers do want engagement on social channels, but not from random brands. So although your brand doesn’t have to get permission to engage with an individual on social media, it would be out of context (and likely unwelcome) to do so if you don’t have that individual’s permission. Once you have permission, it is acceptable to engage. And of course your direct interactions on social media go beyond just that individual, giving your brand exposure to the person’s followers and connections. These kinds of direct engagements also become key signals to the AI driving the cycle of context forward.

Without permission of some kind, whether it’s explicit or implicit, the brand experience is forced, just like a magazine ad is forced. The consumer is not asking for the “moment”; you have forced the entire thing on him or her. But if we as brands are able to meet consumers in their moments, they will be willing to passively share information with us and grant us implicit permission to leverage personal data to create a better experience for them in that moment. Figure 5-2 illustrates how personal data is used to create a more contextual organic experience.

Personal data increases context

Driving engagement after you’ve received permission will still depend on how well you use the other four elements of the context framework to make that experience contextual to the moment. But getting consumers’ explicit permission is what opens those doors.

Brands Must Work to Gain Explicit Permission

As I already noted, things are very different today than in 1999 when Seth Godin first proposed the idea of gaining permission. But while the processes we use today have changed, the same basic idea applies: a brand offers an experience that’s so great that people actively want to follow it, or else the brand must ask for permission. As you progress with context marketing and your brand experiences reach a larger audience, you will naturally gain new followers, but don’t rely on organic growth alone. You’ll need to learn how to grow your audience, and the only way to do that is to ask.

But given the infinite changes in the media environment, how should we go about asking for permission today? Let’s look at two keys to gaining explicit permission in our modern time: the “follow first” and the value exchange.

Follow First

When you’re trying to gain permission, here’s a winning formula: find the followers you wish were already following your brand, and follow them. It sounds simple, but many brands still resist this very basic approach because they overestimate their organic reach and underestimate the ego of humans.

Brands still believe they will gain followers organically, based simply on the content they produce. And that may well be true, but only if your brand already has millions of followers and drives massive engagement. That’s not the reality for many brands on social media, and certainly not where they start out. If you are starting out today, the best way is to first identify your core audience. There are many tools to help you filter through the data available on social media to find people who are a natural fit. For example, you may track a hashtag and filter all users of that tag to a specific geography.

If you are a boutique hotel, for example, you might search for #beststay to find people to follow who posted about their hotel stay while on vacation or doing business (even if they didn’t post about your hotel—yet). And remember, your audience is more than just potential customers; it should include the influencers in your business, your partners, and other individuals and brands active in your space. That’s your audience, and sometimes they are easily found with a search. But often you’ll have to do a bit more digging to find them.

Beyond using simple keywords to search, you could find brands or individuals with a large audience and work your way through their followers, or else rely on tools and AI to suggest people for you. However you find them, the next step is the same: simply request to follow them. Each channel calls this action something different; LinkedIn calls it “connecting,” while Instagram calls it “following.” People love it when others want to follow them. Remember, they are on social media for a reason; following a person constitutes validation that what he or she is doing is loved, wanted, and relevant. Once someone has accepted your request, you are immediately available for private messages and direct communications and able to engage with the person’s content in a contextual way.

Before you begin following people, you should plan ahead and think through the action. For example, if your brand is new to people, you should expect them to look at your social profile as a part of their evaluation. They are unlikely to give you permission if they notice your social feed is a giant ad campaign. You’re going to have to prepare your accounts to fit the value you’re trying to deliver. Make sure your bio, posts, and engagement are all up to par and able to show the value of people following you back.

Offer a Value Exchange

Nearly every retail-clothing site offers visitors a percentage discount off their first online order in exchange for the visitor’s personal email address. That’s a value exchange, and it grants permission for the brand to deliver experiences and interact with that customer directly. Even though subsequent emails from that retailer have a good chance of going to the customer’s spam folder (or its cousin, Gmail’s promotions tab), collecting email addresses is still important. It provides a gateway to gaining more information and greater context—eventually.

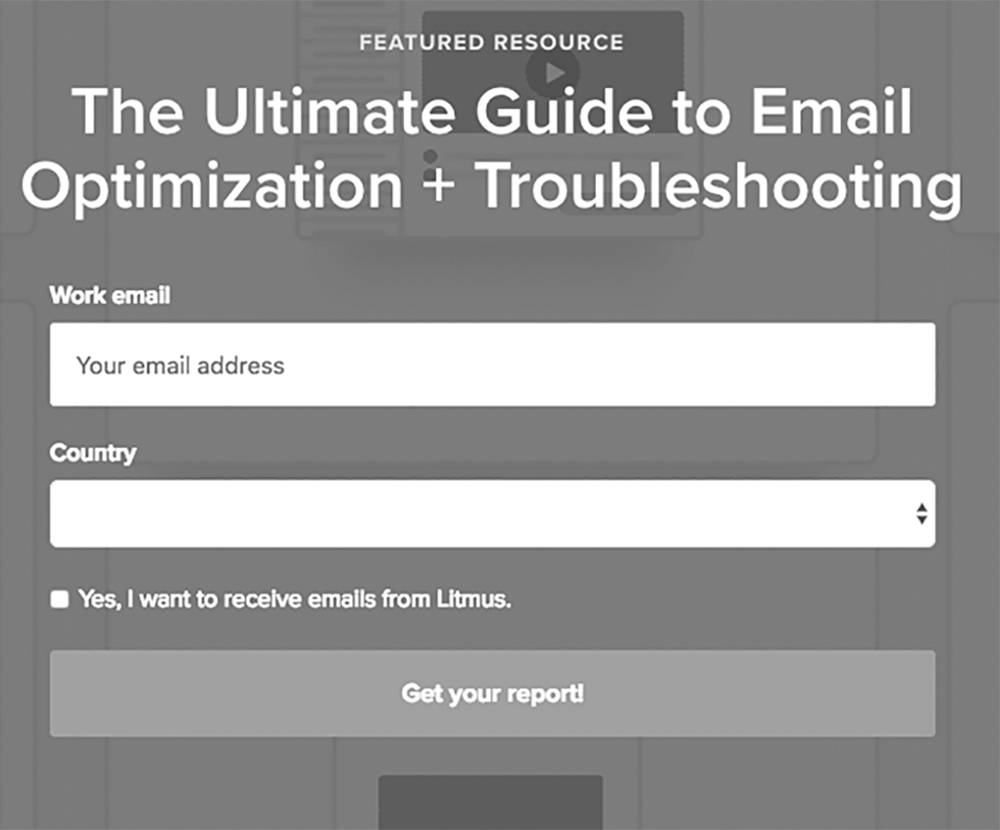

For example, many professional services or B2B companies develop content marketing so that they have something of value to exchange for a prospect’s email address and other information. People have come to expect such offers when researching services that cater to certain industries, such as business consulting, cybersecurity, financial services, and so on. In figure 5-3, the email marketing tool Litmus asks prospects to check the box “Yes, I want to receive emails from Litmus” to gain explicit permission to contact them beyond the delivery of its “Ultimate Guide.”

Source: Litmus website.

If a prospect doesn’t check the box, Litmus does not have explicit permission to send emails beyond delivering the “Ultimate Guide” report. Does that mean it technically can’t email the person? No, it means Litmus does not have explicit permission. One could argue it has implicit permission, but because Litmus asked the prospect for explicit permission, using that email address to send other material risks irritating or even angering the prospect. Such an action by a brand communicates a lack of integrity.

The value exchange also works on social media channels. On LinkedIn, for example, HubSpot created a central meeting place for like-minded marketing professionals by assembling a “Group” of LinkedIn members focused on inbound marketing. In exchange for membership, HubSpot provides thought-leadership content that educates the group on how to be better marketers, and the company curates conversations on marketing topics that help members achieve their business goals. Each of these pieces of content and every conversation also directly helps HubSpot, since it is teaching its audience new ways of marketing that also leverage its tool, thus creating demand without ever creating ads.

The Inbound Marketing Group has grown rapidly because of the value that HubSpot offers in exchange for membership. Early on, HubSpot organized and moderated events associated with the group, but soon the roles reversed, and the group itself began to create the majority of the content and conversation. In 2015, HubSpot’s Inbound Marketing Group proved key to the brand’s achieving the world record for the largest webinar ever held (a new category created by HubSpot’s record)—with 31,100 registrants.2 But it all began with HubSpot seeking permission through a value exchange offered to highly engaged LinkedIn members in a contextual way.

When creating a value exchange on a social media platform, be sure you match your content to the expectations of people using the platform. It makes sense for HubSpot to offer thought leadership to attract members to its Inbound Marketing Group on LinkedIn, because people often search LinkedIn for people and content related to their profession. But how would that content play on a platform such as Facebook? Not well. But that doesn’t mean B2B brands should skip the more purely social platforms. Brands should embrace the many channels their customers are on, but make sure they shift how they use them to match the value the consumers are seeking on each channel.

Kronos, an enterprise brand, uses Facebook to break through to new audiences with its #timewellspent cartoon series. Instead of focusing on its service offering, Kronos offers the Facebook audience something congruent with their reason for spending time on the platform: to escape, laugh, and share funny content with their friends and followers. On average, each of these comics drives upward of 300 likes, shares, and comments, which builds Kronos’s following. In fact, Kronos’s Facebook followers have proven to like only the comics: there’s a stark drop in engagement with the corporate blog posts Kronos published on Facebook. For example, three recent Kronos comics combined generated more than 1,057 likes, comments, and shares, while Kronos’s three recent corporate blogs drove only a total of 16 likes, no shares, and no comments. That makes its comics more than sixty times more likely to break through. This doesn’t mean that Kronos can’t find a way to reach followers with its service and industry-oriented content; it just means it needs to do so using the right channel. And the company will more likely break through in other channels by having already gained recognition and following on Facebook. The long and short of it is that you shouldn’t try to do everything in one channel. Connect with your audience with content that suits each channel, and stick with it.

Once permission has been granted—either implicitly by someone visiting your website or explicitly by someone filling out a form, conversing with a chatbot, or following your brand—your company can gain access to the individual’s personal data, which will become the fuel powering your contextual efforts going forward.

Explicit Permission Grants Access to Better Data

As I’ve noted, consumers grant implicit permission with relative ease. In the United States, the moment someone visits your website or other owned media channels, you have implicit permission to track that individual’s personal behavior across your website, and most consumers are happy to let this happen. This might change, however, should the United States decide to follow the European Union model, in which companies are not allowed to track the personal data of individuals without explicit permission. Hence, the pop-up on Britain’s Financial Times site (see figure 5-4).

But as the continuum illustrates, having implicit permission is only the beginning; explicit permission can improve the data you’re able to access. While implicit permission gives you information about consumer behavior, remember that data isn’t perfect. Just because a consumer looks at a product doesn’t mean she or he wants to buy it. To gather the best data, therefore, brands need to ask consumers for data directly, gaining explicit permission to use it. The better the data, the greater the potential context we can reach and the richer the personal brand experiences we can offer—topics we’ll explore in the next chapter. We might get such data from a survey or form, or an email preference center in which they state what content they want. Personal data will be smaller in volume than the behavioral data we collect, but it provides two major benefits to brand: it’s regulation-proof, and it provides clear guidelines for context.

Source: https://www.ft.com/.

To access explicitly permissioned data, you must do four things. First, ask for it, via a form, a chatbot, or even from a live conversation with a representative of your brand. Second, explain how you plan to use the data. Salesforce research found 86 percent of consumers trust a brand more with their data if the brand reps explain how the data will be used. The Financial Times did a good job of this, stating clearly how the company is going to use your data. Third, be transparent about how you are using personal data. At any point if an individual were to ask, “Why am I seeing this?” the brand should be able to provide the data driving that decision. Fourth, allow consumers to see what data you have on them and allow them to turn it on, or off, and even amend it if they like. The same Salesforce research found that 92 percent of customers trust brands with their data when the brand gives them control over it.3

When brands take these four steps to gain explicit permission, they not only foster trust among their customers but also create a reliable flow of personal data that is regulation-proof. But beyond that, such permission provides powerful guard rails for context. For example, asking people if you can email them is seeking “permission,” but going a step further to ask “What types of emails would you like?” is better. The answer will guide your email programs, helping you increase the context of your direct communications by sending only the type of content consumers prefer. Do they only want to receive coupons, your newsletter, or both? Let them tell you.

Such personal data will also help you keep customers moving through their journey. Asking how satisfied customers are (for example, emailing out a customer satisfaction survey) provides you with detailed explicit data about how to continue forward. If they aren’t happy, you need to pull back, evaluate what you’re doing, and fix whatever the problem is. If they are happy, maybe you automate a program inviting them to become an advocate. The explicitly permissioned data you’ve gained is what drives such programs, and you can gain that permission only if you ask.

Permission is a key element of context. All of your future efforts will hinge on the personal data your brand can access once it has permission. Without permission, you will be unable to reach higher context in the experiences you offer customers. Brands following the four steps I outlined in this chapter will always be able to access personal data and use it to grow trust and improve the context of any moment.

Next we’ll look at how we use that data to make moments and experiences more personal—the next element in the context framework.