4.

Available

Helping People Achieve the Value They Seek in the Moment

For a brand experience to break through the noise, a customer needs to see it or hear it or feel it—and ideally all three. In other words, it needs to be available, which is the first of the five elements composing the context framework. Making your brand experience available means consciously choosing and orchestrating how you deliver it, so that your customers gain the value they seek in the moment. That is the ultimate definition of meeting customers in their context.

And make no mistake: how people encounter a brand in the infinite media era greatly affects their attitude toward it. Do you force it on people, or do they find it on their own? How you deliver the experience will determine how much the consumer trusts the brand and how likely he or she will act on that trust and engage with you. Get the context right, and your audience is much more likely to take an interest in your brand.

Traditional marketing uses a forced approach to make brand experiences available to the largest number of people possible, and the more captive the audience, the better. Think about the last time you sat in a movie theater while a commercial played on the big screen before the feature began. Maybe you found it entertaining, or maybe it was overly loud and annoying. But it’s unlikely you remember today much about it, and even more unlikely that it motivated you to engage with that brand. Context marketing couldn’t be more the opposite: its ultimate goal is to help people accomplish their task at hand. Rather than reach masses, context marketing aims to make a single, human-to-human connection at the most opportune moment.

This brings us to an important point: when it comes to the ways marketers make their brands available, there’s a range of efficacy in their methods, a continuum between least effective (traditional marketing) and most effective (context marketing). That is, even if you as a marketer are unable to make an immediate leap to the most effective path to availability, there are ways to work with where you are, specifically in the middle of the continuum.

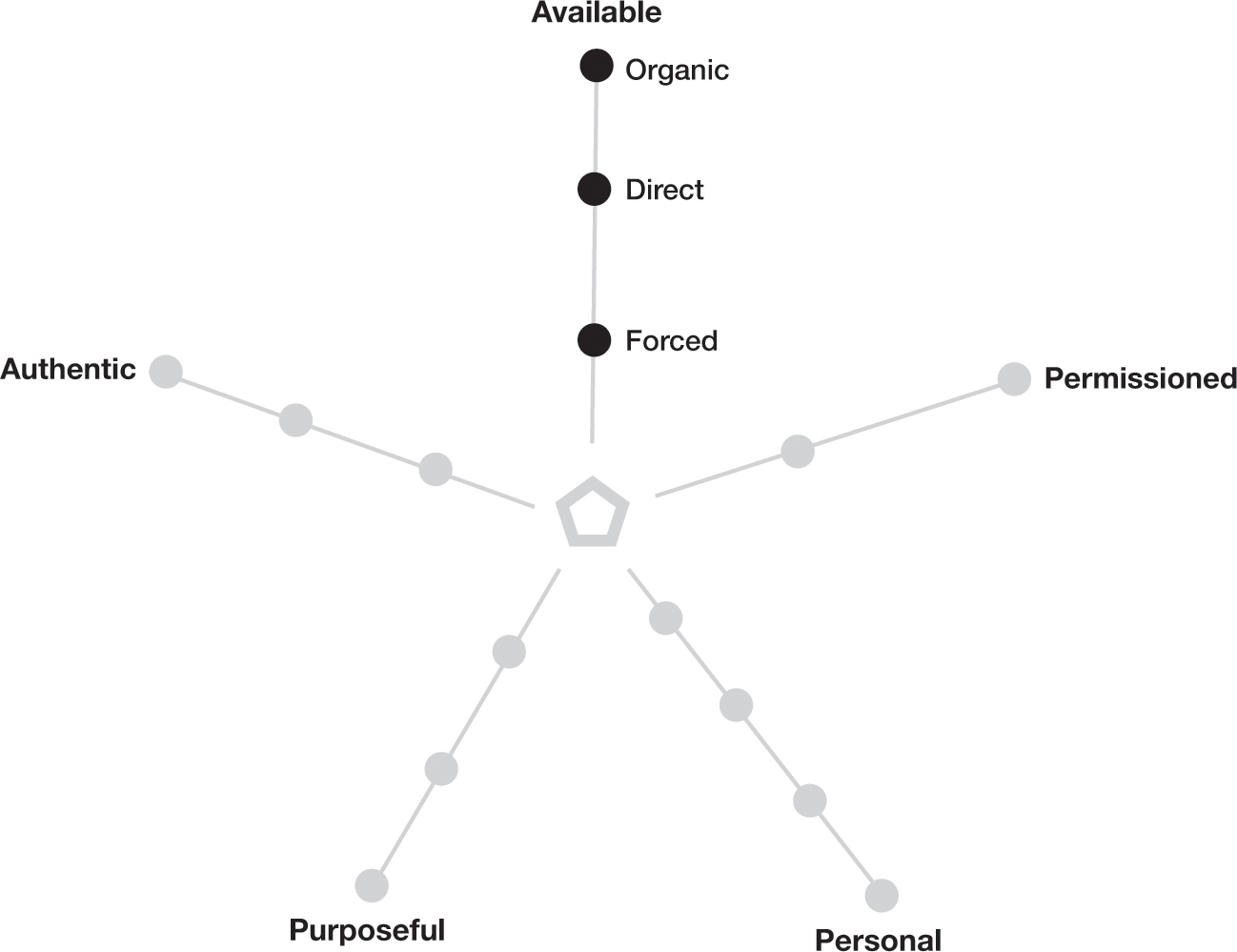

The context framework (available)

I identify three points along that continuum, three methods of making your brand experience available (see figure 4-1). At the lowest end are forced experiences: magazine ads, billboards, pop-up ads, or the commercial you sat through in the movie theater. Next on the continuum are direct experiences, which can range from email to social media engagements. Finally, there’s the apex of effectiveness in the infinite era—organic experiences, which are found by individuals in their own time.

Understanding the distinctions among these methods of availability, their power to break through in particular moments, and how to use them to create better experiences across the customer life cycle is the first step to becoming a contextual marketer.

The Forced Experience: Demanding Attention

Forced experiences are the least contextual, because they are one-way. They are designed to work on consumers, trying to distract their attention and compel them to buy. When people are forced to sit through your brand experience—your commercial, your click-through ad—you’ve demanded their attention but you likely didn’t really get it. Rather, you purposely delayed what your audience members really wanted to see: the movie, not your ads.

The problem with a forced experience is that it gives little thought to context, which is all that the viewer really cares about. Yes, you might have considered the context of your content: whether the main event that follows your brand experience, such as highlights from a recent sporting event, will likely attract an audience similar to yours. But you still haven’t given thought to the context of what an individual viewer is looking for in that moment. Nearly all of the creative effort is placed on the message you will broadcast, not the experience you are creating for the viewer. That perspective, in a nutshell, is the difference between traditional and contextual marketing.

For years, forced availability was powerful, and it catapulted many brands into superstardom: Pillsbury, Energizer batteries, Kellogg’s cereals, and many others.1 Even ten years ago, people still expected to sit through forced ads, but now that we are well into the infinite media era, consumers have gotten used to having control. They don’t easily tolerate being forced to watch or click anything. In fact, research recounted in an Atlantic article found that people are more likely to survive an airplane crash than to click on a banner ad!2 Most often, forced ads get skipped (when possible), ignored, or blocked by software. That isn’t to say that a fifteen-minute short video, for example, can’t be part of a contextual customer journey. But it would have to be thoughtfully connected to the individual’s experience in that moment, and it shouldn’t be forced on him or her.

The Direct Experience: Delivering a Message

Direct brand experiences, such as email, messaging applications, and social media engagement, offer more context than forced messages because they are conversational channels that allow brands to work directly with people rather than making them watch or listen. These are experiences that happen directly between a brand and an individual, delivered to one of several types of inboxes, including the feeds and messaging applications used on social media platforms.

The increasing use of privacy controls by consumers means that direct experiences almost always require marketers to gain permission to deliver directly to someone’s inbox of choice. The permissions hurdle makes direct experiences more contextual, but it also requires an extra layer of creativity. Chapter 5 explains ways to gain permission, but right now we’re going to get clear on the most contextual kinds of direct experiences, so you’ll know what to do with permission once you get it.

Direct marketing used to be simply forced messages to individuals that were delivered at set intervals by either email or the postal service. Rather than seeking permission, marketing departments usually just purchased from third parties addresses that were approximately their audience. These mediocre lists were the backbone of direct marketing efforts for years.

The infinite media era has changed all of that. Direct marketing today runs continually—not at set intervals—and it is permissioned and creates value for recipients in the moment they encounter it. There’s no single goal or call to action. Rather, direct brand experiences are created at various points along the buying path and work together to move people along the customer journey. By providing the next piece of information or knowledge the consumer needs, when needed, brands guide, inspire, and motivate individuals. Ultimately, the most contextual direct experiences become human to human, which we’ll learn about in the chapter 6 discussion of the framework element “Personal.”

Although not as ideally fashioned for the infinite era as are organic experiences (as we’ll learn in this chapter), direct marketing experiences can be tweaked and broadened to move them up the continuum to greater levels of contextual consumer engagement.

Expand Your Idea of Direct to Make Your Brand More Available

Direct marketing has moved past simple emails and posts to include all of today’s methods of engagement provided by social media, such as likes, comments, shares, mentions, and direct messages. Each of those methods gives marketers a new way to make themselves available to their audiences, both proactively and reactively. Let’s look at some specific strategies that marketers have used successfully.

Engage with User-Generated Content

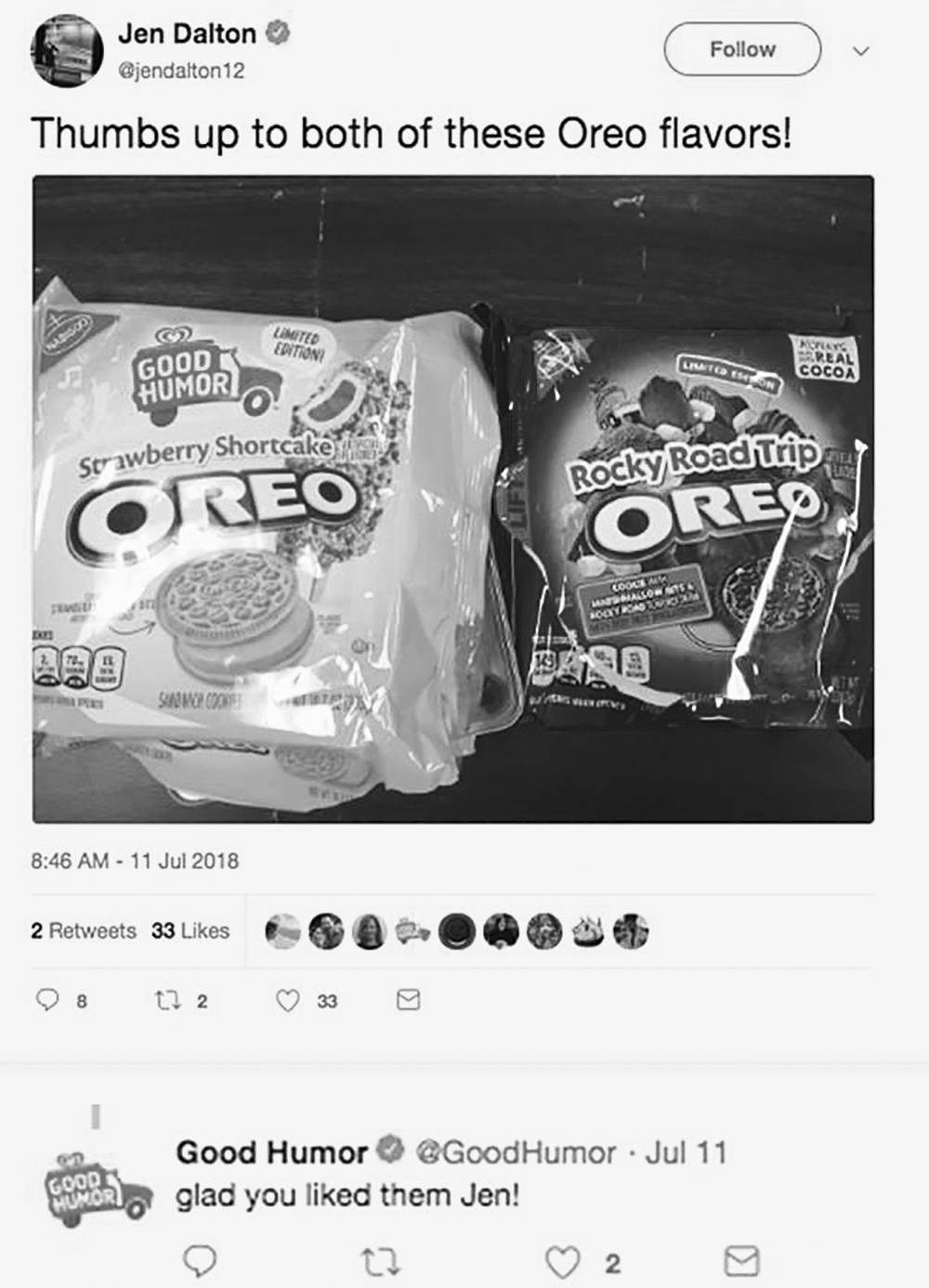

Traditional direct marketing is proactive: the brand typically reaches out first. This idea is still valid, but it’s important to add reactive brand experiences too. Direct marketing is very powerful in these moments because the consumer has already created the context for marketing to engage by posting a brand image, for example, on social media. Marketers can then reactively create a brand experience by commenting on the post or sharing a published post on the brand’s own channel. Many marketers still find it hard to believe that consumers want brands to engage with their social media posts, but most people will acknowledge a brand’s reaction, even if the brand wasn’t tagged purposely. Take the example from Good Humor in figure 4-2:

Jen Dalton did not mention Oreo’s cobrand Good Humor in her tweet, but Good Humor likely had an automation “listening” for keywords associated with the launch of its new venture with Oreo. When the automation “heard” what it was listening for and brought it to the attention of Good Humor’s marketing department, it engaged in two ways: it first liked the post and second wrote a comment to the author of the post, Jen. While some brands might refrain from engaging unless expressly mentioned, Good Humor bet on its friendly voice being well received, and it was. Jen liked Good Humor’s comment. (I’ll go deeper into listening and other automations in chapter 9.)

Source: Good Humor Instagram feed.

If this seems like a negligible interaction, it’s not. These engagements are personal acknowledgments that users of social media are seeking. You are fulfilling a customer’s (or future customer’s) immediate desire in the context of the moment. In social media language, a “like” is an affirmation saying “I hear you,” “I’m with you.” When a user likes a comment, it is shorthand for “Thank you” or “I agree.” Brief exchanges on social media channels can also include the use of emojis that convey messages instantly, such as “I love it,” “That makes me mad,” or “That’s hilarious”—all of which are phatic ways of acknowledging the author of the post and perhaps prompting an exchange with each other. Such small, direct engagements allow brands to stay front and center in the lives of their audience in new ways and in context.

Parlay the Power of “the Mention”

Mentions are another great direct method for making your brand available contextually on social media. The mention allows anyone to directly associate a person with a brand experience either immediately at the time it is posted or later on. The LinkedIn post from Vince in figure 4-3 illustrates how this works:

In creating this brand experience for his employer, SBI, Vince mentions Jill and Sarah directly, which is why their names are in bold. When Vince hits the “Post” button, Jill and Sarah are notified directly of their mention, while Jill’s and Sarah’s followers might see it in their main LinkedIn feed, driving them to view Vince’s post. The more interaction Vince’s post gets, the better the chances of it appearing in the feeds of Jill’s and Sarah’s connections. This means it was very helpful to Vince for Jill to mention Jamie in the comments section, after the story was published. Jamie’s response to Jill’s mention of him provides the needed interactivity to boost the post’s stature and make it more widely available.

Again, this interaction might appear inconsequential to those not familiar with how social media works. And again, it’s not. Here’s how to view it: Jill and Sarah participated in the event, so Vince hardly needs to make them aware of it. He is mentioning them to reach the hundreds, if not thousands, of connections in Jill’s and Sarah’s networks. It’s no accident that the content was shared by Vince and not by his company (SBI). The human-to-human conversation makes this brand experience available to a larger audience in a much more personal way (coming in chapter 6) than a post from the company announcing that they “had a great time at their event!” Vince’s post also exemplifies a new type of direct marketing where employees, advocates, or other brand extenders are able to make content available directly and permissioned in ways that are more difficult for a brand to create on its own.

Source: Vince Koehler LindedIn post.

While Vince had his reasons, Jill had a slightly different reason for using the mention. She may be doing some contextual marketing for herself as a presenter, and Jamie may be someone she knows is interested in the topic. Or perhaps Jamie works for a company where Jill would like to make inroads. We’ll never know, but Vince undoubtedly benefited from Jill’s action, and Jill likely did too.

Drive Interaction within Private Messaging

Likes, shares, comments, and mentions all happen in the public space. All of these social media platforms also have a private form of communication through direct messages. Messaging applications became the most used aspect of social media back in 2015, and now every channel has some form of it: Facebook Messenger, LinkedIn Messaging, WeChat, Twitter Direct Message, and Instagram Direct, to name a few. The good news for contextual marketing is that people aren’t only messaging friends and family; they’re also engaging with brands more and more through messaging, as the evidence shows.

Facebook IQ conducted a study on the use of mobile messaging with 12,500 people across the world. It found several promising trends among the people surveyed:

- Sixty-three percent said that their messaging with businesses has increased over the past two years.

- Fifty-six percent would rather message than call a business for customer service.

- Sixty-one percent like personalized messages from businesses.

- More than 50 percent are more likely to shop with a business they can message directly.3

Where email has a lot of competition, messaging applications are fairly void of brand interactions, even though people are open to engaging with brands there. This makes them a greenfield with a lot of room to experiment with creating contextual brand experiences there. Here are a few examples to show why they are so powerful.

Jay Baer, who runs the marketing agency Convince and Convert, told me his company recently tested using Facebook Messenger. The company found that messages sent via the social messaging channel were opened ten times more than the emails it sent, and those individuals who opened the social messages were five times more likely to click, share, or engage with the content than their email counterparts receiving the same content. Similarly, HubSpot, a marketing technology provider, offered people interested in its content the option to access it in two ways: either fill out the form or skip the form and get the content via Facebook Messenger. People who chose the Messenger option were 242 percent more likely than those who chose email to open the message (33% open rate for email compared with an 80% open rate for Messenger) and 609 percent more likely to engage (2.1% click rate in email compared with a 13% click rate in Messenger) with the content.4

And here’s a bonus takeaway: people really hate to fill out forms. Give them another option, and they’ll take it.

Absolut Vodka was way ahead of the curve on this one. It combined the power of targeted digital advertising with its ability to engage individuals through Facebook Messenger. First, Absolut posted a highly targeted ad on Facebook offering a free drink to people who engaged. The ad was connected to Messenger, guiding users into an experience where they could converse with a chatbot and claim their free drink. The net result was a 4.7 times lift in sales for the brand compared with Absolut’s other efforts (see figure 4-4).

The power of making direct experiences available in a multitude of ways that land correctly with your audience is what drives contextual “direct marketing.” That said, traditional forms such as email and direct mail should not be ignored. They are still very powerful, but as consumers begin to move from just one inbox (email) to many (social + email), brands will soon be migrating more and more to targeted engagements in direct messaging channels.

Use Automations to Make Direct Methods Available Anytime

While direct methods are not the pinnacle of the context framework (we’ll get to that with “Organic”), they do have a serious advantage in that they can be automated. Recall the Good Humor example in this chapter—the company had an automation “listening” for keywords, which is just one kind of marketing automation. There are many automated moments that can be tailored to execute brand experiences at a specific moment, to a specific person, triggered by almost anything.

In the simplest terms, automation allows marketers to shift from starting every conversation with an identified segment in the same way to having bespoke conversations with each individual from the get-go, at scale. Brands that are using this kind of automation with email communication were found by ANNUITAS to produce 451 percent more qualified opportunities over traditional direct email tactics.5 That is, the highly personal, one-to-one emails used to automatically nurture each person from his or her initial interest up to the point of being ready to purchase is four times more effective at generating business than any other email method.

This corroborates our Salesforce 2018 State of Marketing research, which found high-performing marketing organizations to be 9.7 times more likely to use automations than underperformers are.6

All direct methods, including email, direct mail, and direct social interactions, gain in their ability to reach greater context when they are executed automatically. Automations allow sets of conditions to be defined, such as in the case of Good Humor: when someone mentions the words Oreo and flavor, the automation takes a predefined action. It alerts the marketing team to the post, so someone can engage with it. These “listening” automations create a rich range of conversations that brands can now join—and they can even distribute the notifications to the proper teams (sales topics can be sent directly to sales, support questions to the support queue, and so on).

While automations are powerful, they do require a new investment in technology and a new set of tactics, which I’ll cover in detail in part three.

The Organic Experience: Interaction and Lots of It

Consumers are much easier to engage when it is their idea to interact with a brand in the first place. That is why organic experiences represent the pinnacle of the available element in our context framework. Brands create an experience that connects with people exactly when they want that experience. That moment might occur almost anywhere, when someone is searching on Google, shopping on Amazon, or perusing Facebook. Or perhaps they’re browsing in a store or sitting at home on a laptop or using a tablet at an airport. At the very moment an individual searches for information related to our brand, it is our job as context marketers to be found and to interact. That’s what it means to craft an organic experience.

Some brands have built their entire business by focusing on organic brand experiences. The startup wristwatch brand Daniel Wellington focused exclusively on Instagram, relying on the organic nature of the platform to reach its audience contextually and motivate those people to learn more. The strategy worked. In its first four years of operation, the company sold more than one million watches.7 Focusing on organic search engine rankings—also known as inbound marketing—is also a powerful way to build brands and drive business. Arbor, a senior living community operator with more than thirty communities, reports that 64 percent of all new residents arrive after finding Arbor organically through searches.8

I’m using the word organic, but perhaps it should be in quotation marks. Because when your brand experience is made available organically, it nevertheless has been served to individuals in your audience algorithmically. Chasing algorithms is hardly new, but they—like the media channels that employ them—have a new master. They no longer look predominantly for keywords or meta-tags; they are searching for and acting on engagement by individuals, and we marketers need to expand our idea of how, where, and when we optimize for organic experiences.

Traditionally we marketers have employed the long-standing practice of search engine optimization (SEO) to improve our brand’s ranking in search results, and many of us still rely on it. This practice of building web experiences to meet the criteria that search engines seek has led us to busily fret over keywords, meta-tags, page load times, and dozens of other factors. The ranking algorithm used by major search engines still demands that we keep to the general rules of SEO, but that is not sufficient to get our brand experiences to show up on page one of search results. We now must also focus on interaction with our audience.

This same focus on interaction applies to social news feeds as well. When news feeds started out, they were chronological accounts of our networks; now they are contextual accounts. To see what I mean, take a look at your news feed on Facebook, and note the date and time the posts were created. You’ll notice a wide range: some were created moments before, some years before. They are showing up in your feed based not on chronology but on contextual engagement. And the most important form of engagement is an interaction—a comment, conversation, share, or like. When a person or brand is able to drive interaction with an experience, it becomes more likely to be shown to others (as we saw with “the mention”), spreading the experience farther and farther. So what determines a post’s reach is not its publication but rather people’s participation with it. In fact, interaction drives the organic availability of brand experiences and content in all settings. Retailers such as Amazon and Apple’s App Store operate the same way. They look for engagement with items to help them filter through thousands of products, which enables these retailers to make the best recommendations possible to their users.

To be clear, interaction is just one of many factors driving algorithms (some of which are brands’ highly guarded secrets), but it is the major one, coupled with SEO, that allows marketers some ability to make their brand experiences available to the people expressly looking for them.

An outstanding example of participation now being more powerful than publication occurred the day after the 2016 US presidential election. That day, if you searched for “election results” on your browser, the number one search result was not CNN or any of the major news outlets; it was the website 70news.wordpress.com. That’s right, a website hosted on a free domain hacked the biggest news story of the decade, because, based on the engagement it was able to create with its election story, the search algorithms determined 70news would provide the best experience for its users.

How did 70news.wordpress.com do it? It used a set of tactics to drive engagement that included salacious headlines and memes designed to emotionally connect with its right-wing audience. These memes and headlines, shared across social media, email, and other third-party news sites, homed in on exactly what they knew their audience wanted to see and share.

We all share stories, posts, and memes that validate the image we hold of ourselves. 70news’s audience was primarily far-right-leaning people, so when they were presented with a story or meme that validated their position, they readily interacted with it, often without ever reading the underlying story. (By the way, this isn’t just a right-wing thing; a Columbia University study found that 60 percent of articles shared on social media are not read by the person sharing the article.9) Each of these shares, likes, or comments on the 70news story became another engagement, signaling to the algorithm that it likely would be engaging to others, driving up its organic reach.

But here’s the key to why 70news climbed to the top: CNN.com’s official election results page included 82 backlinks (other sites referencing your content as the source of their story) and 40,000 social shares. But the news story on 70news had 1,500 backlinks and more than 400,000 social shares. So even though CNN had been online decades longer and had a much larger total presence and a larger social following, it lost out in search results to a small player, strictly because in the infinite era algorithms favor participation over publication.

This phenomenon was made possible by the fact that people on social media trust what they find more than they should (though that is now changing). It’s also likely that some of this engagement was driven by a new and nefarious tactic: bot armies. These armies of artificially intelligent bots can be programmed to respond as a provocative troll in the comments section of various platforms to spur conversation and controversy. And, of course, people find controversy engaging—and engagement makes content more available organically.

By no means am I suggesting that you create fake news or engage in black hat tactics such as bot armies. I offer this example to show that getting your audience to interact with your content is paramount to being organically available. Simply publishing and promoting content is not enough. To be available in any of these search results or news feeds, brands need to add targeted engagement with social media and other sites to their daily to-do lists. We marketers need to expand our vision and consider the many questions and conversations that potentially take place over the life cycle of every customer. Most of the questions you can answer and the conversations you can join best occur on sites other than our own, because they offer greater context to our audiences.

For example, marketers at Acquia, an open source software company, noticed a question posted to Quora (a social question-and-answer portal) that they knew their prospective buyers were asking along their journey. Rather than answer the question “as a brand,” it leveraged advocates to answer it for them by posting a link to the Quora question in its community portal. More than twenty of its brand advocates added comments to the Quora post directly, each from their personal account, adding their own personal story. These advocates willingly spent their time answering the question and advocating for Acquia (that’s the power of advocacy, the final step in the new customer journey that we’ll explore more in part three). Most important, because of the engagement those advocates drove to the Quora post, it is now the number one result for that particular question and is continually being served up to each new person who asks it. In creating this cycle, Acquia leveraged the value it had already created for its customers to reach more people and guide them toward its brand in a highly contextual way.

This strategy of leveraging other channels to ensure that your brand surfaces organically also applies to traditional public relations efforts, such as narrative control. Where traditional PR is about publishing a story in the media to control the narrative of the moment, PR should also be looking to control narrative along the customer journey by answering the questions marketing has identified and working to land story lines specifically for SEO. Marketing, in fact, should work closely with PR teams because a brand’s site does not have the same power as a publication.

For example, it would be hard for a brand’s website to rank in a Google search for the term “best looks for fall,” but it wouldn’t be hard for your PR team to pitch a story to a powerfully ranked publication to get your brand name listed in an article about it. Once the story is live, context marketers can motivate their audience to interact with the article, driving the story higher on the page of search results. When your brand is available on that page in the moment someone is looking for it, you have made your brand experience organic in the most powerful context possible.

Looking at the three major ways described in this chapter to make your brand experiences available, one theme carries through: the importance of interaction. Whether engaging audiences by email, through social media, or via a search engine, all channels are tuned to a new master that makes interaction more powerful than publication alone. In other words, yes, you need good content, but that is only the tip of the iceberg. The real work is interaction with individual members of your audience.

Now, let’s look at the next element of context: creating brand experiences that are permissioned.