Assyria Besieges Jerusalem (36:1–22)

Field commander (36:2). This is one of the three high military officials whom Sennacherib sent against Hezekiah (2 Kings 8:17). He bears an Akkadian title rab šāqê (lit., “chief cup-bearer”),864 which is transliterated into Hebrew here (cf. KJV, “Rab-shakeh”). The position was a vital one, serving right beside the king and at times controlling access to him. This proximity led to trust between the king and the official, which may be why he is the official spokesman here. The Assyrian Eponym list records several officials with this title.865

Eliakim son of Hilkiah the palace administrator (36:3). Eliakim is literally “over the house” (22:15), the royal steward. Equivalent to an Egyptian vizier, he is in charge of daily palace operations. Several Hebrew seal inscriptions from the eighth and seventh centuries have the name “Eliakim,”866 though not all refer to this son of Hilkiah. Ones that are likely to do so are found on jar handles from the period of Hezekiah. The royal larder would have been under his purview as steward, so wine and oil for royal consumption could well bear his official stamp. Several seals and other inscriptions also belong to people designated as “over the house.”867

Shebna (36:3). See comment on 22:15.

Joah . . . the recorder (36:3). Literally, a “recorder” (mazkîr) is “one who reminds,” a secretary, who occupied an important place in palace administration.868 The term is used on a Moabite seal from the mid-first millennium, “Belonging to Paltay, son of Maʾosh, the recorder.”869 In the Assyrian Eponym Canon, an identification of successive years by the name and office of important officials, 741 B.C. is associated with Bel-Harran-Belu-Utsur, “palace herald,” the equivalent of this term.870

The great king, the king of Assyria (36:4). “Great king” is a common title of Assyrian royalty, used even by Sennacherib in his own inscriptions.871 “King of Assyria” or “of Assyria and Babylonia” is also well attested.872

On what are you basing this confidence? (36:4). Israel is to put her trust in Yahweh, her God (8:16), but the Assyrians mock them for trusting on what they view as a powerless god. Tiglath-pileser I writes: “At the beginning of my kingship, 20,000 Mushkean men and five of their kings . . . trusted in their own strength. . . . With trust in Ashur, my lord, I really inflicted a defeat on them.”873

The Assyrian view of history was that events on earth reflected those in heaven. For example, Marduk’s gaining supremacy over the other deities in the Enuma Elish epic874 is reflected by Babylonian ascendancy over its neighbors. The Egyptians’ powerlessness to aid Israel derives from weakness of their gods, and Yahweh himself has lost power if Judah’s own king can remove his shrines. The Assyrian mockers fail to realize that these shrines are removed instead because of the powerful Yahweh (2 Kings 18:4). Orthodox Yahwism understands this theology, being convinced that Yahweh alone is in control of both heaven and earth.

You are depending on Egypt, that splintered reed of a staff (36:6). A rod or staff needed strength in order to provide weight-bearing support. A reed, which is pliable, cannot supply needed support, and even less if it is broken (see 42:3). Sargon made this same claim concerning the king of Ashdod who sought to lead the kings of Palestine, Judah, Edom, and Moab away from following Assyria. “To Piru, king of Egypt, a ruler unable to save them, they brought their greeting gifts [see 1:23], they repeatedly pestered him (to be their) ally.”875

High places and altars Hezekiah removed (36:7). See 30:22. Destruction of a temple or deportation of a divine statue removed the deity’s influence. It meant that this god was so ineffective that he could not even look after his own interests. Sennacherib, describing the capture of Babylon, states: “My men took the gods who dwelt there and smashed them.”876 The Assyrian military leader claims that a king who neglects or opposes a god will suffer that god’s displeasure, even as far as losing his position.

The Hittite Proclamation of Anitta of Kushshar claims: “Previously Uha, king of Zalpuwa, had carried off our goddess [Halmashuit]. . . . [Regarding the city Hattusha], their goddess Halmashuit gave it over [to me], and I took it at night by storm.”877 Cyrus made the same claim: Neglecting worship led the gods to turn Babylon over to him.878

Aramaic . . . Hebrew (36:11). See comment on 33:19. The Israelites distinguish here between two languages used in their area. Aramaic was the lingua franca of the Near East at this time (see 19:18), but most native Israelites did not understand it—a situation that changed during the exile, when it became the home language of many exiled Israelites. The other language was Hebrew (lit., “Judean”), a southern dialect that the people understood,879 which Shebna was trying to prevent from being spoken.

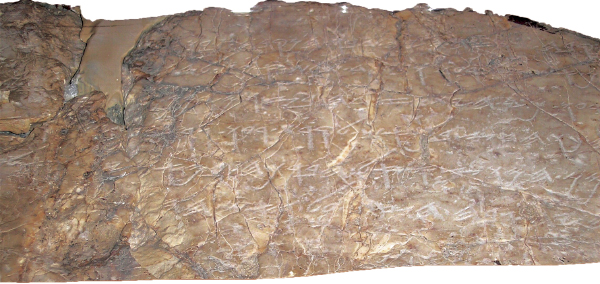

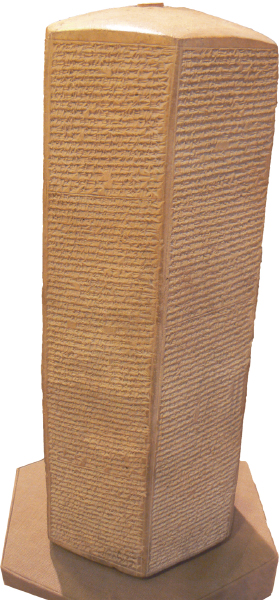

Osorkon I hieroglyphic inscription with accompanying NW Semitic/Byblos

Rama/Wikimedia Commons, courtesy of the Louvre

Simultaneous use of two languages for different purposes was not uncommon. Sumerian and Akkadian were used simultaneously in Mesopotamia. The Amarna tablets show Akkadian texts with Canaanite glosses,880 and there is a hieroglyphic inscription with an accompanying version in Northwest Semitic.881

Filth . . . urine (36:12). Filth (lit., “feces, excrement”) is naturally repulsive and is the last thing a starving people would eat (2 Kings 6:25). This shows the desperate and helpless state of the besieged Israelites. The helplessness and degradation of the Canaanite god Ilu is shown when he arrives at his palace completely drunk and carried by others: “HBY . . . soils him in his feces and his urine.”882

Drink water from his own cistern (36:16). Cisterns, artificial water reservoirs cut into bedrock, were important for a people without a steady and certain water supply. Public cisterns were supplemented by private ones for those of sufficient means to dig one. This propaganda promises this advantage to everyone.883