God the Merciful Creator (43:1–14)

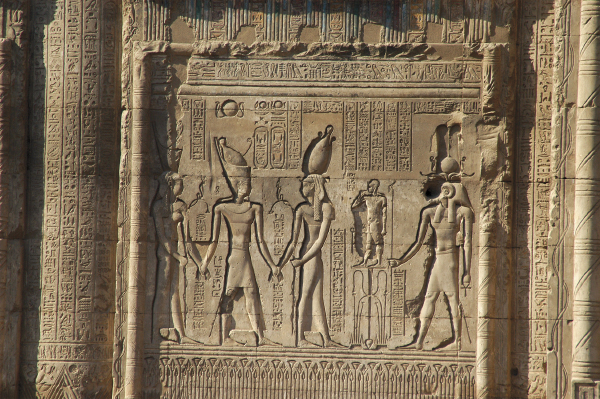

He who formed you (43:1). See comment on 42:5. The verb connotes working and forming like a potter does the clay (e.g., Gen. 2:7). A Twelfth Dynasty stele of a royal treasurer of Egypt says that “he is the Khnum of everybody, begetter who makes mankind,”1069 and the situation is so bad in the Admonitions of Ipuwer that “women are barren, none conceive, Khnum does not fashion because of the state of the land.”1070 In the Instructions of Amenemope, Khnum is called “The Potter”1071 since he forms everyone on his wheel.1072 He is depicted on a relief from Luxor fashioning Amenhotep III on a potter’s wheel.1073

Khnum forming human on potter’s wheel

Brian J. McMorrow

The Enuma Elish story speaks of “the black-headed people (i.e., humanity) whom his (Marduk’s) hands have created,”1074 a term used elsewhere of making figurines from metal or stone.1075 Isaiah’s concept moves beyond physical craftsmanship to an intimacy of relationship. Humanity is not simply formed and used, but made and cherished.

Fear not (43:1). See comment on 41:10.

I have summoned you by name (43:1). In Mesopotamia, from the early Dynastic to the Neo-Babylonian periods, kings received a divine call, legitimating them in office. For example, an inscription of Esarhaddon reads: “whom Assur, the father of the gods, called my name for the rule of the land of Assur and the governorship of the lands of Sumer and Akkad,”1076 and “Nabu-apla-iddina, king of Babylon, called by Marduk,” the god of Babylon.1077 Here the entire nation of Israel is personally commissioned by God, not just her ruler, for service of him.

Pass through the water (43:2). Baal, the Canaanite storm god, is pictured as walking on flowing water, symbolizing his power over it.1078 In the Baal Epic, he defeats the power of the water in the form of “Sea” and “River.”1079 Israel itself does not have such power and cannot on her own survive an encounter with overwhelming water. Survival can only come through the protection of her God. Water is controlled by him as its Creator.

Baal stele shows Baal walking across the waters.

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY, courtesy of the Louvre

I am the LORD (43:3, 11, 15). See comment on 41:13.

I love you (43:4). See comment on 41:8. Mesopotamian texts record several different objects of the love of the gods. The most common recipient of such divine favor is the king, with one, Narām-Sin, “beloved of the god Sin,” having this as part of his name.1080 Private individuals also have this as an element of their name.1081 The gods are also said to love places, such as the temple Eanna that Esarhaddon describes as “beloved of my lady Ishtar.”1082 Israel’s God, rather than loving an individual or place, loves an entire people, acting on that love on their behalf.

Bring in their witnesses (43:9). See sidebar on “Covenant Lawsuit” at 1:2.

Before me no god was formed, nor will there be one after me (43:10). God’s uniqueness (see 46:9) is expressed in terms of relative time of formation. Ancient Near Eastern theogonies (accounts of the origins of the gods) are usually structured around generations of gods in family relationships or formed by some other physical means (see 42:5).1083 Of Khnum, the Egyptian creator god (see 43:1), it is said that “he has fashioned gods and men; he has formed flocks and herds.”1084

The gods are represented by the natural phenomena with which they were associated.

Caryn Reeder, courtesy of the British Museum

Gods come into being not simply on an ontological level, an understanding of whether they exist or not, but on a functional one, since they are tied with natural phenomena and thus have tasks in the physical world. Function and form came to be simultaneously. Receiving a function and a name brought a new deity into being.1085 The latter is shown in the Enuma Elish story, which speaks of a time “when yet no gods were manifest, nor names pronounced, nor destinies decreed.”1086 Divine functions also related to spheres of influence, with some deities playing roles in heaven, others on earth, still others in the netherworld. The earthly sphere was also delineated by influence over distinct geographical areas, whether temples, towns, or nations.

Yahweh here starkly contrasts himself with other deities. He does not identify himself in cosmogonic terms of his own beginning or end, but places himself completely outside this temporal realm, unlike all other gods. This also contrasts his function (the unlimited in contrast to the limited) and his realm to theirs (all of creation in contrast to a limited geographical sphere). He is therefore unique, unaffected by their bickering for power and position.

When I act, who can reverse it? (43:13). The irreversibility of God’s acts is attributed to Marduk in Enuma Elish. He wished supreme authority over the gods: “Let me ordain destinies instead of you. Let nothing that I bring about be altered, nor what I say be revoked or changed.”1087 He is then told: “Your command is supreme! Henceforth your command cannot be changed.”1088 In the Gilgamesh Epic, the collective of the gods decided to destroy humanity, but their plans were thwarted by one of their own, Ea, who leaked the news.1089 Yahweh, as sole God wielding unique divine authority, has no one who can sway him from his decisions.

Babylonians, in the ships in which they took pride (43:14). Both Egypt (e.g., Deut. 28:68) and Mesopotamia used ships in warfare and in trade much more than did the Israelites.1090 A letter from Amarna uses this Hebrew word for “ships” (ʾnyh) when speaking of Labayu from Megiddo: “I will send him to the king by boat.”1091 Sennacherib brags of such activity that the wood used by the boat builders “made tall trees in the forests rare.”1092 He used them for transporting captives: “I carried off the people of Bit-Iakin with their gods, and the people of Elam . . . loaded them on boats, and brought them across to this side.1093 Here, however, rather than being the captors, Babylon will become fugitives from Cyrus and the Persians on their own vessels.