TO THE DELTA

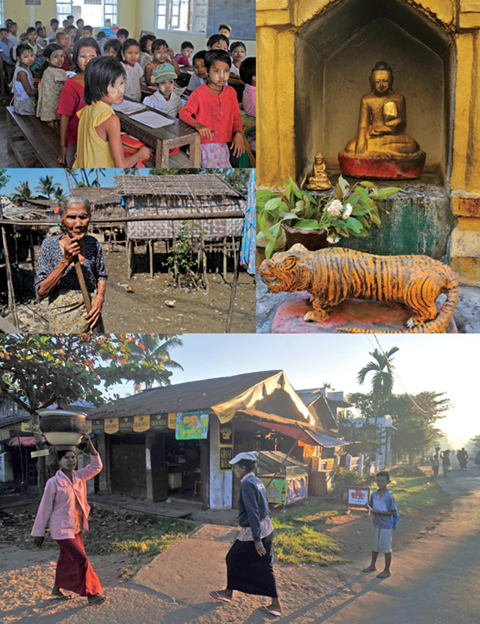

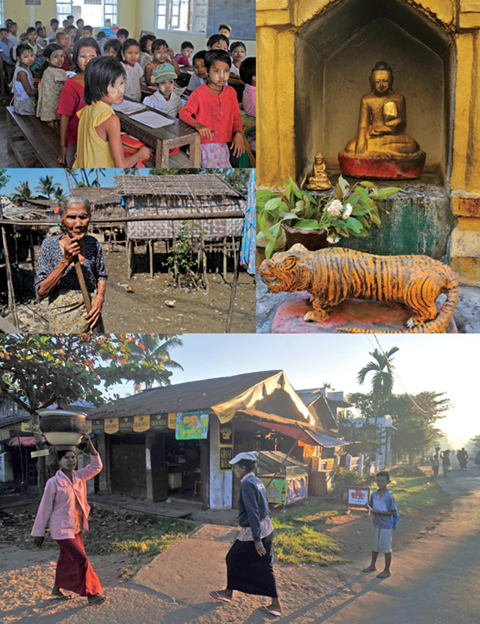

Images from the Irrawaddy Delta. CLOCKWISE FROM BOTTOM: Early morning in Bogole. An older woman whose face shows the wear and strain of life. A classroom of children in a newly built school near Bogole, less than two years after Cyclone Nargis. A tiger shrine, with Buddha statue behind, at a temple in Pathein.

IN MAY 2008, Cyclone Nargis devastated parts of the Irrawaddy Delta with wind and rain and flooding, killing over 100,000 people. Twenty months later in Rangoon, I met an English woman who’d gone to Burma right after the cyclone. Despite the government’s resistance to offers of outside help, she had taken a truckload of relief supplies down to the delta. She was interested in getting back there, to a town called Bogole, to see how rebuilding efforts were going, and I was happy to keep her company.

We applied for travel permits in a sleepy office that looked like a scene in a movie set in the colonial 1930s. The next day at the dock downtown, we had our permits carefully checked, and walked onto a crowded ferry to cross the Yangon River. The other shore was a different world: poorer, slower, and quieter than the busy city across the way.

We found a share-taxi headed to Bogole, an old suspension-challenged station wagon. Soon we understood why the suspension was shot. The road—sometimes paved and pitted, sometimes just dirt—wound past tall palm trees, small huts on stilts, and rice fields still sickly from their inundation in salt water during the cyclone.

The other passenger in the taxi was a young Burmese working for an NGO in Bogole. We bombarded him with questions. He told us that a disproportionate number of women had been killed in the cyclone, and that many families were fragmented. It was hard to imagine how whole communities could find their feet again, with so much social, emotional, and material loss. He told us that most of the ducks and pigs had died in the storm, and that nearly all the water buffalo—the essential beast of burden for farmers in the delta—had been swept away. Later, at his office in Bogole, we saw a job posting advertising a “buffalo procurement” position.

On the plus side, donations by people in the rest of Burma and by foreigners meant that Bogole was doing pretty well. In town, we saw new schools, the classes full of lively children, and mothers with plump, healthy-looking babies. Building supplies were stored in sheds along the riverside.

But when we went out in a boat to poke around in the waterways out of town, the basic level at which people were living was dismaying. Only half an hour from the relative prosperity and full markets of Bogole, families were still “housed” in makeshift lean-tos and shelters, essentially roofs with no walls. They were doing what they could to improve their situation: men were working on mangrove restoration projects (the mangroves stabilize the shoreline and protect the land) and there were vegetables growing by every shelter. Children played on the riverbanks.

street-side rice crepes, myitkyina style

MAKES ABOUT 12 CREPES; SERVES 4

These beautiful crepes (called yei mont in central Burma and mok ghieh-ba in Kachin State) are made at markets all over Burma. They are close first cousins of dosa, the crepe-like flatbread of southern India, but like other dishes in Burma that probably originated in the Indian subcontinent, they have taken on a distinctive identity.

The batter is made of rice flour and unlike dosa batter, it is not fermented, instead whisked up just before it’s needed. The crepes are cooked on one side only, in a very lightly oiled skillet. They are sprinkled with a little oil as they cook and then topped with an eclectic, attractive mixture of textures and flavors: finely chopped tomato (the vendors use scissors to cut off thin wedges), minced scallions, coriander, a scattering of cooked chickpeas or cowpeas, minced green chile, and often strips of fresh coconut. The crepe is folded over the toppings and served as a half-moon, sometimes accompanied by a dipping sauce, such as red chile chutney.

Cooking these takes practice, as any crepes do, so you may have to discard the first one or two. You will need a well-seasoned cast-iron or other heavy skillet 7 or 8 inches in diameter (it’s more difficult to heat a larger pan evenly). It’s useful to have a pastry or other brush for dabbing a little oil on the breads as they cook.

BATTER

¾ cup rice flour

½ teaspoon salt

¼ teaspoon baking soda

1½ cups lukewarm water

Scant 1 teaspoon minced ginger (optional)

About ½ cup peanut oil

TOPPINGS (ALL OR SOME, AS YOU PLEASE)

¾ cup thin tomato wedges, preferably Roma (plum) or another fleshy tomato

1 cup coarsely chopped coriander

½ cup minced scallions

¼ cup minced seeded green cayenne chiles (optional)

½ cup fresh coconut strips (optional; see Glossary)

Combine the rice flour, salt, and baking soda in a bowl and whisk in ½ cup lukewarm water until you have a perfectly smooth thick batter. Add the remaining 1 cup water and stir or whisk to incorporate it. (You may think there is a typo in the recipe because the batter is so thin. Don’t worry!) Stir in the ginger, if using.

Place a well-seasoned 7- or 8-inch skillet over medium heat. When it is hot, add about 1 tablespoon oil and use a heatproof spatula to spread it over the pan, then wipe away the excess with a paper towel. Quickly stir the batter, then scoop up about 2 tablespoons of it and pour it onto the center of the skillet. Tilt the pan so the batter flows over it. It will move quickly across the pan’s surface, making a lacy pattern; if there are any large gaps, dab on a little extra batter to fill them. Let the crepe cook for about 30 seconds, then brush the center very lightly, barely touching it, with a little oil, or dribble on a few drops of oil. Use your spatula to see if the crepe is starting to crisp at the edges; once it is, drip a few drops of oil under the edges in a couple of spots.

Make this first crepe plain, so that you can get comfortable handling it: fold it in half, flip it over for 15 seconds, and transfer it to a plate.

Repeat with the remaining batter and oil, stirring the batter each time before you start, but with subsequent crepes, sprinkle toppings on one half of the crepe once it has started crisping at the edges: a scant tablespoon each of peas and chopped tomato, a teaspoon each of coriander and scallions, and a pinch of minced green chile as well as a little coconut, if you want. Fold the crepe over the toppings, flip it over for 15 seconds, and use a spatula to transfer it to a serving plate or individual plate; serve hot or warm with a chutney or sauce.

Street-side crepes in Mandalay.

rice-batter crepes

[KHAO SOY KHEM NOI]MAKES ABOUT 7 CREPES; SERVES 4

The inventiveness of people who work day to day with basic ingredients is almost limitless. These steamed savory crepes are made in Kengtung, north of the Golden Triangle; I’ve never seen them anywhere else. The alternate title above is in Tai Koen, the majority language in Kengtung; and the Shan name is khao soy biu bang moh. They’re kind of a cross between noodles and crepes.

Each morning in the local market, kids and adults sit on low benches as the crepe maker keeps two pans going, steaming the crepes by floating the pans in big pots of water. Once the first layer of batter is cooked, she asks whoever is next what he or she wants as flavoring and topping. The choices include soy sauce, fish sauce, pea tendrils, lettuce greens, and chopped roasted peanuts. She drizzles on the flavorings, and often a little sugar, adds another layer of batter, and then sprinkles on greens and herbs. The pan goes back into the pot to steam for another couple of minutes, then she carefully rolls up the crepe and hands it to the waiting hungry customer on a small plate.

These are a great option for people who are gluten-intolerant.

BATTER

1 cup rice flour

¼ cup tapioca flour

¼ cup cornstarch

2 cups lukewarm water

¼ teaspoon salt

OPTIONAL FLAVORINGS AND TOPPINGS

Soy sauce

Rice vinegar or black rice vinegar

Fish sauce

Sugar

1 cup coriander leaves, coarsely chopped

1 to 2 cups torn or coarsely chopped lettuce leaves, fine pea tendrils, or other tender greens

Whisk together the batter until very smooth. Pass it through a sieve if you are having trouble getting rid of lumps.

Put the flavorings and toppings of your choice by your stovetop.

Lightly oil an 8- or 9-inch shallow cake pan. Make sure it floats. Pour 2 inches of water into a wide shallow pot and bring to a boil. Pour the batter into the oiled pan (if it is 9 inches in diameter, you’ll need about 3 tablespoons; use 2½ tablespoons for an 8-inch pan). Tilt the pan to spread the batter all over, then use tongs to place the

pan in the boiling water. Cover the pot and steam until the crepe is cooked through, 2 to 3 minutes. It should be translucent and lifting away from the pan a little.

At a small morning market in the old Tai Koen capital Kengtung, in eastern Shan State, steamed savory crepes are made to order.

Lift the pan out with tongs, splash on a teaspoon or more of soy sauce, vinegar, fish sauce, and/or garlic or shallot oil; a dab of chile oil; a sprinkle of sugar; and a couple of tablespoons of peanuts. Pour on a scant 3 tablespoons batter and swirl to spread it (it will become stained as it mixes with the darker condiments, which is fine), then top with the coriander and other greens too if you wish. Put back into the pot with tongs, cover, and steam until the greens have wilted and the top layer of batter is cooked through and translucent, about 3 minutes.

Lift the pan out with tongs and set on a work surface. The crepe is like a large noodle sheet: use a round-tipped spatula to help lift an edge of the crepe, then roll it up, loosely lift it out of the pan, and place on a plate. Repeat with the remaining batter and flavorings/toppings.

Serve plain or with a dipping sauce.

tender flatbreads

[NAN-PIAR]MAKES 24 THIN 8-INCH-DIAMETER FLATBREADS

Known as nan-piar, these fine tender flatbreads are closely related to Indian naan and are made in markets in many parts of Burma. Usually they’re baked in a tandoor oven (for which a baking stone in a regular oven is a good substitute). The breads are slightly sweet and leavened with both yeast and a little baking soda.

Make the dough about 2 hours before you want to bake the breads. Or make it the night before, and shape and bake the breads in the morning. The breads bake in a couple of minutes. Serve for breakfast or as a snack anytime, spread with almond butter or topped with slices of firm cheese (and see

Sweet Flatbread Breakfast, below). This is a large recipe that yields about 2½ pounds of dough. You can bake half the dough one day and then save the rest for the next day.

1¾ cups lukewarm water

½ teaspoon yeast

5 to 5½ cups all-purpose flour, preferably unbleached

2 tablespoons sugar

1 egg

2 teaspoons salt

½ teaspoon baking soda

Put the water in a large bowl, sprinkle on the yeast, and stir. Add 2 cups of the flour and stir to make a smooth batter. If you have the time, let rest for 20 minutes.

To make the dough by hand: Sprinkle on the sugar, add the egg, and stir in thoroughly. Add 2 cups of the flour, the salt, and the baking soda and stir to incorporate. Add another ½ cup of the flour and stir. Once you can pull the dough together into a ball, turn out onto a dry, generously floured surface. Knead, incorporating more flour only as necessary, until smooth, soft, and elastic.

To make the dough using a food processor: Combine the batter, sugar, and egg in the processor and process briefly to blend. Add 2 cups of the flour, the salt, and the baking soda; process to blend. Then add another cup of the flour and process until a ball of dough forms. Process for another 10 to 15 seconds. Turn out onto a lightly floured surface and knead for a minute, incorporating more flour only as necessary. The dough should be smooth, soft, and elastic.

Set the dough aside in a tightly covered bowl, and let rest for 1½ to 2 hours; you can also let it rest overnight in a cool place if you wish.

Twenty minutes before you wish to bake, place a rack in the center of your oven, lay a baking stone, pizza stone, or a surface of unglazed quarry tiles on it (see

Glossary), and preheat the oven to 500°F.

Meanwhile, dust your work surface with flour, turn out the dough, and cut it in half. Set half aside covered in plastic wrap (if you won’t be using it until the next day, refrigerate until 1 hour before you wish to bake). Cut the remaining dough in half, and then in half again. Cut each quarter into 3 equal pieces—you will have 12 pieces altogether. Roll each piece firmly between your lightly floured palms to make a smooth ball, then flatten each to a 2-inch disk on the floured surface. Set aside, loosely covered with plastic wrap, for about 15 minutes.

Working with one disk at a time on the lightly floured surface, press first one side and then the other into the flour, then roll out to a round 7 to 8 inches in diameter, working with short firm strokes of the rolling pin and rolling from the center outward; rotate the bread a quarter turn or so after each stroke of the pin. (This technique helps prevent the dough from sticking to your work surface as you roll it out.) Set aside and repeat with another disk. Stretch each bread a little more with your hands, so it’s as thin as possible.

Transfer one bread onto a baker’s peel lightly dusted with flour or the floured back of a baking sheet and use the peel or sheet to transfer the bread onto the hot baking stone or quarry tiles. Repeat with the other bread. Bake for 2 to 3 minutes, or until they are touched with color on the bottom and have little bubbles on top but are still soft and pale, then remove and wrap in a cotton cloth to stay warm and soft. Repeat with the remaining dough.

Serve as a snack or to accompany any meal: the breads are thin and seductive, so allow 3 per person.

rangoon tea-shop banana flatbreads

At my favorite tea shop in Rangoon, the breads are pale yellow and sweet. The baker’s secret ingredient is ripe banana. To try this, substitute 1½ cups water mixed with ½ cup pureed very ripe banana for the water in the recipe, then proceed as above.

sweet flatbread breakfast

Spread nan-piar with lightly mashed tender cooked chickpeas or cowpeas (see Peas for Many Occasions), sprinkle on a little sugar if you wish, and roll up. Cut into 2-inch pieces and eat with pleasure, to accompany tea or coffee. This combo of bread and cooked peas, with or without sugar, is known as nan-piar bei-leh.