In 2010, the Middle East was in turmoil. The Tunisian Revolution successfully overthrew President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali, triggering the start of the Arab Spring. The power of the Internet, particularly social media, garnered global attention.1 On the other side of the world, critics of the Chinese regime, inspired by the Arab Spring, called for their own Jasmine Revolution, with the hope of disrupting the regime through online and offline mobilization.2 But these calls had little visible or lasting impact. One demonstration on Wangfujing Street in central Beijing, which had been widely advertised online by democratic activists, turned out to be a micro–street spectacle: Literally a handful of protesters showed up, surrounded by thousands of onlookers and hundreds of policemen and foreign journalists.3 Before the protesters were finally taken away, they received little support or even sympathy from the bystanders.

As the political scientist Lisa Anderson has perceptively pointed out, the importance of the Arab Spring lies neither in how protesters were inspired by globalized norms of civic engagement nor how they used new technology, but in “how and why these ambitions and techniques resonated in their various local contexts.”4 Compared with regimes that were toppled in the Arab Spring, China has a stronger authoritarian state, which can more effectively control its population, and a robust economy providing more job opportunities.5 Moreover, the Chinese Party-state has a proven record of adapting to challenges.6 However, state capacity and adaptability can hardly explain the minuscule scale of mobilization in China considering the pervasiveness of social unrest7 and Internet-enabled mobilization.8 In particular, unlike offline mobilization, which tends to center on narrowly defined concrete demands,9 online activism in China often targets the authoritarian regime in general and poses demands for more freedom and democracy. In effect, Internet users are popularly known as “netizens” in China precisely because the term carries a sense of entitlement and citizenship that is generally absent in authoritarian regimes.

The contrast between the countries involved in the Arab Spring and a more resilient authoritarian regime like China suggests an intriguing relationship among technological development, social empowerment, and authoritarianism. Why has the Internet helped scuttle authoritarian rule in some cases, but failed to do so in others? More specifically, why has online activism not translated into an offline movement in China akin to the Arab Spring? What explains the paradoxical coexistence of an empowering Internet and resilient authoritarianism in China? By investigating the struggles over online expression—both as a cat-and-mouse censorship game and from the perspective of discourse competition—this book makes a counterintuitive twofold claim: (1) The Chinese Party-state can almost indefinitely coexist with the expansion of the emancipating Internet; but (2) the key explanation for this coexistence does not lie in the state’s capacity to control and adapt, as many have argued, but more in the pluralization of online expression, which empowers not only regime critics, but also pro-regime voices, particularly those representing pro-state nationalism.

The book questions the assumed relationship between state adaptation and authoritarian resilience. Though regimes such as China are highly adaptive to challenges—as witnessed in the highly sophisticated censorship system and various innovative propaganda tactics the state has employed—it is naïve to assume the effectiveness of state adaptation or to assume adaptability is the sole reason for its resilience. As the research in this book shows, the Chinese Party-state has encountered tremendous difficulty in translating its formidable despotic and infrastructural power into effective control over the Internet. The book also interrogates the liberalizing and democratizing power of the Internet from a new angle. Sheri Berman finds that a vigorous civil society may, under certain circumstances, scuttle democracy.10 Likewise, pluralized online expression may ironically help sustain authoritarian rule by activating and empowering regime defenders. In China, through neutralizing regime-challenging discourses and denigrating regime critics, spontaneous pro-regime groups have rendered online expression less threatening to the Party-state.

Instead of seeing the state and the Internet as single monolithic entities, the book highlights the fragmentation of both. It reveals the complex internal dynamics of Internet control by differentiating the roles of the central state, local authorities, and intermediary actors. It also captures the pluralist nature of online expression by exploring the interactions among the state, its critics, and various netizen groups. In doing so, my argument maintains that the Chinese Party-state is not as strong as it appears but also that the Internet’s threat to the regime may have been overestimated. Such findings suggest that neither the regime’s resilience nor the Internet’s power can be assumed but must be carefully analyzed, assessed, and contextualized.

WHEN THE EMPOWERING INTERNET MEETS THE AUTHORITARIAN REGIME

With its inherent “control-frustrating characteristics,”11 the Internet has become the locus of debates over political liberalization and democratization in authoritarian regimes. Arguably, it provides “new tools of connectivity, information diffusion, and attention,”12 which help citizens better connect, express ideas, organize, and mobilize.13 For instance, in the Arab Spring, social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube played a critical role in shaping political debates, mobilizing protests on the ground, and promulgating democratic ideas.14 According to the political scientists Philip Howard and Muzammil Hussain, digital media diffusion rates and the capacity of state censorship are crucial to explain success or failure in achieving regime change.15

Though highly censored, China’s Internet has created a relatively free discursive space, which some see as an emerging public sphere.16 Chinese netizens have not only managed to circumvent and challenge state censorship in creative and artful ways, but also transformed the Internet into a platform for online activism.17 The freer flow of information in cyberspace—as compared to traditional media—has also promoted civil society by enhancing both internal communications and the interconnectedness of civil organizations,18 and it has facilitated citizen activism by enabling both domestic and overseas Chinese to mobilize against the regime.19

There is no question that the Internet has challenged the Party-state. But the state has also adapted itself to control the Internet’s disruptive effects. According to Lawrence Lessig, Internet control may operate via four mechanisms: the law, technical architecture (code), social norms, and the market.20 In China, all four are subject to heavy influence from or direct control of the state. To tame the Internet, the Party-state has undergone a process of policy learning and capacity building and has constructed a complicated and subtle censorship regime over time to control both the network infrastructure and online content.21 Today, the censorship system allows the state to filter taboo words, block or shut down websites, suppress dissent groups and active netizens, and deter deviant expression.22 For instance, the state has not only established a nationwide “Great Firewall” to filter and track online information,23 but it has also attempted to have all personal computer (PC) manufacturers preinstall Green Dam software, meant to filter out pornography and other undesired information from the users’ end.24

To what extent, then, has the Internet empowered citizens or challenged authoritarian rule in China? To answer the question properly, it is crucial to depart from a perspective that focuses mainly on the dyad of state control versus social resistance in cyberspace.25 Though the perspective is helpful, it does not account for the diverse activities that occur in Chinese cyberspace and exposes only a limited slice of the politics and role of the Internet in political communication.26 In particular, it tends “to see politics only in the higher echelons of power or as its outright subversion,”27 thus preventing effective examination and evaluation of the less confrontational, more creative aspects of online struggles. In effect, the state has gone beyond simple censorship and shifted toward a more subtle management of popular opinion28 by employing innovative propaganda tactics such as deploying paid Internet commentators, a.k.a. the “fifty-cent army” (wumao dang, 五毛党), to fake pro-regime voices29 and embracing popular cyber culture to make state propaganda appealing.30 Similarly, social actors have not only fought with the repressive state in artful and creative ways,31 but have also engaged in practices of online activism that hardly fit neatly into the liberalization-control framework.32

This book introduces two specific analytical concerns not fully addressed in the current literature. First, it shows that the impact of the Internet on Chinese politics is much more mixed and complicated than a dyadic model in which either the society or the state dominates. Indeed, it may have contributed more to liberalization than democratization in that it is enabling greater political involvement of Chinese citizens but failing to move China toward a democratic transition;33 it can function as a safety valve or a vehicle for political activism, depending on whether netizens plunge in ahead of mainstream media.34 Moreover, this research brings attention to understudied critical actors in Chinese cyberpolitics, including intermediary actors such as forum administrators who directly mediate censorship enforcement35 and regime defenders such as the “voluntary fifty-cent army” (zidai ganliang de wumao, 自带干粮的五毛; literally “the fifty-cent army that brings its own rations”).

Second, the book highlights the necessity to disaggregate both the state and cyberspace to better understand cyberpolitics in China. Though scholars have long recognized the internal fragmentation of the Chinese Party-state and its implications for both policy making and implementation,36 few have explored the horizontal and vertical cleavages within China’s Internet governance structure. Evidently, multiple state agencies are involved in content control and discourse competition. Their diverse interests and motivations have together shaped the landscape of online politics in China. Likewise, it is improper to assume a monolithic Chinese cyberspace that is inherently liberalizing and democratizing. While many observers have hailed this new technology for emancipating the society from authoritarian rule, others have emphasized its detrimental, disintegrating effects and suggest that online expression may lead to the polarization or even Balkanization of the public.37 The research in this book supports such a “fragmentation thesis” through an investigation of the dynamic process of online discourse production, circulation, and interpretation in China.

PUBLIC EXPRESSION ON CHINESE INTERNET FORUMS

As the sociologist Guobin Yang has insightfully pointed out, “The Chinese Internet should not be viewed in isolation from its social, political, and cultural contents and contexts.”38 Interestingly enough, though the struggle over online expression constitutes the core of many studies of cyberpolitics in China, few authors have traced the process of information production, spread, acquisition, and containment in the context of an online environment such as that of Internet forums. This book, through exploring how the state, its critics, and netizens struggle over political expression on Internet forums, addresses precisely this issue.

As platforms for public expression, Internet forums were first introduced to China in the form of the bulletin board system (BBS) by research and educational institutions in the mid-1990s. While early BBS sites provided only telnet access, web platforms were developed later and became mainstream. Besides discussion boards where thematic conversations take place, most forums today also provide within-site mailing and messaging systems, chat rooms, blogging services, and even games to facilitate interaction among users.

Most Internet forums are accessible to both registered and unregistered users. But to engage in discussion, that is, to post or reply to threads, one often must register an account. Though initially a valid email account is sufficient for registration, increasingly more forums are asking for additional identification information such as phone numbers and student or even official identity numbers, partially driven by the state’s real-name registration policy push. In some cases, registration is by invitation only. Many forums do not restrict the number of accounts one can register. Even forums that attempt to impose such a limit often fail to do so without actually enforcing real-name registration. Postings are often in textual format, though multimedia postings (i.e., pictures, videos, and audio material) are increasingly common, thanks to improved hardware, bandwidth, and software platforms.

Besides state surveillance, forum management expends significant effort to monitor online expression. Internet content service providers such as forums, blogs, and microblogs have installed keyword-filtering software to prevent postings with taboo words from being published. Manual scrutiny is also important, even for forums with pre-filtering measures, as many netizens are creative enough to circumvent the automatic filtering. Board managers and editors—either selected from users or appointed by forums—are responsible for stamping out noncompliance by deleting posts, suspending or permanently eradicating user accounts, or even banning Internet Protocol (IP) addresses. To guide discussion, forum management can also promote certain posts by highlighting them, recommending them for the front page, or placing them at the top of the board. On large public forums, special content monitoring personnel are often installed in addition to or in place of board managers to ensure more effective surveillance. Apart from private forums set up and run by individuals, most medium-size and large forums are affiliated with larger entities such as academic institutions or companies and managed by them. In some cases, these institutions reserve the power to directly intervene in forum management when they deem necessary.

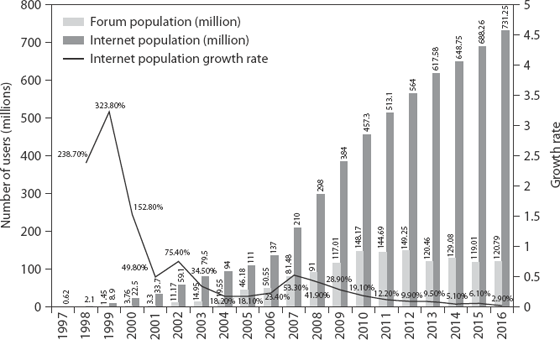

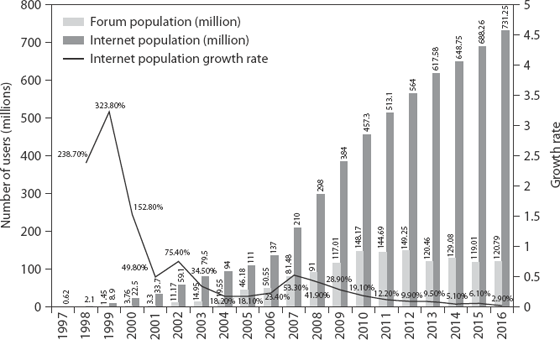

Internet forums offer a first-rate window onto Internet politics in China. First, they remain popular and together attract around 120 million users despite the rapid expansion of newer social media platforms such as microblog services (e.g., Weibo) and instant messengers such as WeChat (figure 1.1 and table 1.1). As of January 2017, one of the largest forums, Tianya.cn, claims almost 120 million registered users with over one million of them simultaneously online during active periods through the day. Even some campus-based forums, which usually have highly restricted user bases, boast simultaneous user populations of more than one thousand.39 Admittedly, applications such as the Twitter-like Weibo and the instant messenger WeChat have surpassed forums in terms of popularity and influence in recent years. But studying forums still allows certain advantages, namely, a better “historical sensibility.”40 In fact, the evolution of Internet forums probably captures the history of Chinese Internet politics more completely than other applications.

FIGURE 1.1 China’s Internet and online forum population (1997–2016)

Notes: Data from CNNIC Statistical Reports on the Internet Development in China. All figures are year-end data of the particular year. The 2007 forum population was not reported.

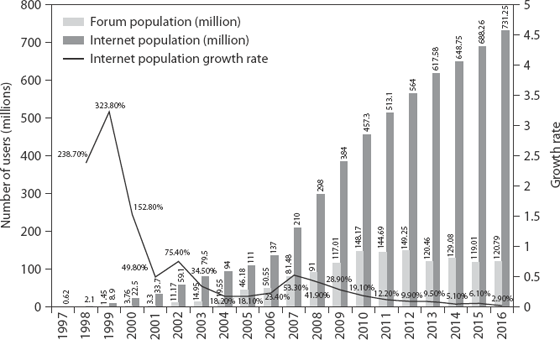

TABLE 1.1 Selected Most Frequently Used Online Services (2009–2016)

Abbreviations: BBS, bulletin board system; SNS, social network service.

Note: The blog penetration rate dropped dramatically because the China Internet Network Information Center changed the category in 2014, excluding personal spaces from blogging services.

Source: China Internet Network Information Center Statistical Reports on Internet Development in China; see www.cnnic.net.cn.

Second, compared with user-centered social media platforms such as social network services, blogs, and instant messengers (e.g., QQ and WeChat) where the host often has discretion over the topic and audience, online forums are topic centered and essentially more “public.” Discussions on forums usually feature common-interest topics and are conducted in a many-to-many communication manner. Such “publicness” makes Internet forums important platforms for political expression and online activism. Though political content may comprise “only an extremely tiny portion of China’s cyber-cacophony,”41 this is not true on popular online forums. In fact, thematic discussion boards devoted to social and political affairs are often among the most popular ones.42

Finally, the types of user interaction on popular online services often strongly resemble a forum. In fact, many popular platforms also incorporate the forum function. For instance, on China’s social network sites, such as kaixin001.com and renren.com, BBS participation occurs at extremely high rates: More than 80 percent of social media content is in the form of a BBS.43 In addition, blogs and microblogs become hot spots for online traffic when their hosts gear the discussion toward public affairs. Chinese online news portals have also introduced interactive features so that readers can respond to news reports by clicking expressive icons or adding comments, just like they do on forums.

Though this research has chosen to focus on Internet forums, it is important to note that digital platforms for public expression and social participation in China have evolved over the past two decades. In particular, social media services such as Weibo and WeChat have become the new frontiers of citizen activism and Internet governance. For this reason, the analysis in the book incorporates observations from platforms such as blogs and Weibo whenever relevant.

TWO STRUGGLES OF ONLINE EXPRESSION

Exploring state–society interaction in Chinese cyberspace reveals two different struggles: the struggle over censorship and the struggle over discourse competition. If online expression is a virtual territory, the struggle over censorship centers on the definition of its boundaries, whereas discourse competition emphasizes the landscape within those boundaries (table 1.2). Close examination of both struggles provides an opportunity not only to map the power relations between state and societal actors more accurately, but also to evaluate the political impact of online expression in a more nuanced and balanced way.

TABLE 1.2 Two Perspectives on Online Expression

| |

Censorship and Counter-Censorship |

Discourse Competition |

| Main actors |

State, intermediary actors, and various netizens groups |

State agents, regime critics, and various netizens groups |

| Battlefield |

Boundary spanning: what can and cannot be expressed |

Within boundaries: how to express ideas |

| Framing |

Three-actor confrontation (state–intermediary actors–users) |

Discourse competition (e.g., struggle for freedom against repressive regime versus defense of nation against sabotage) |

| Power exercised |

State: coercive and technological Forum managers/netizens: technological and expressive |

Expressive and identity |

The Cat-and-Mouse Censorship Game

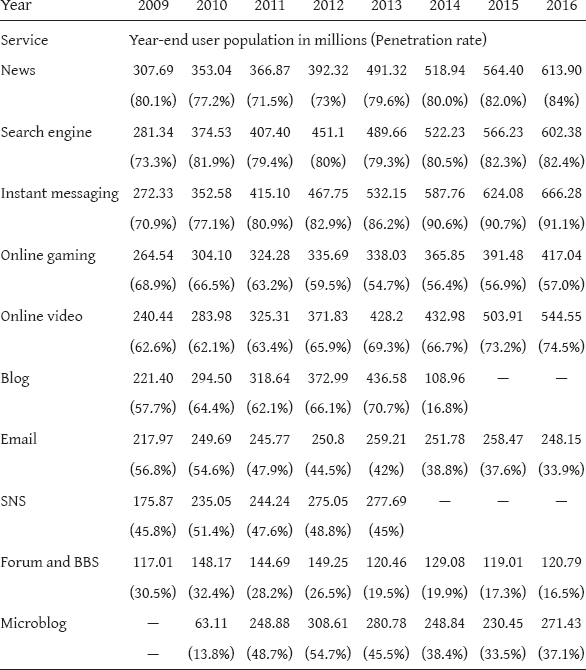

Censorship is a boundary-spanning struggle44 over the limits of what can and cannot be discussed online. Though the struggle over censorship seems to be a story of state censorship versus netizen resistance, this book suggests a multi-actor perspective that highlights the fragmentation of the authoritarian state, the role of intermediary actors, and the diversity among netizens. This three-actor cat-and-mouse censorship game is vividly illustrated in figure 1.2, with netizens surrounded by various state agencies that attempt to control expression and the intermediary actors being trapped in between.

FIGURE 1.2 Anti-extermination campaign online

Notes: The figure has been widely spread online and the original source cannot be identified. This version is adapted (by adding English translation) from: “Tianchao Wangmin de Xiongqi, Fan Weijiao Xingshitu” (Uprising of Chinese Netizens: The Map of Anti-Extermination Campaign), http://itbbs.pconline.com.cn/diy/10854454.html, retrieved August 20, 2012.

The Chinese state has demonstrated formidable despotic and infrastructural power both before and in the digital age. To harmonize the Internet, the Party-state, like many other authoritarian states,45 has undergone a process of policy learning and capacity building through technical, institutional, and administrative means. However, external challenges and internal fragmentation within the regime limit the state’s ability to control the flow of online information. In particular, the volume and creativity of online expression have forced the state to rely on rigid techniques such as keyword filtering and, more importantly, the delegation of censorship to intermediary actors such as Internet service providers. Yet, intermediary actors are neither loyal accomplices of the state nor wholehearted allies of netizens. Instead, they take a position of “discontented compliance,” complying with state censorship mostly in order to survive, while also occasionally tolerating or encouraging boundary-spanning expression. For netizens, online expression is not merely a realm of digital contention. State censorship, discourse competition, and the pursuit of fun have together driven the fusion of politics and popular expression tactics, contributing to the rise of “pop activism” in which entertainment serves both as a means of spreading political messages and as an end in itself.

The struggle over censorship suggests that state control over online expression is at best quasi-successful. Though successful in keeping politically indifferent netizens away from taboo zones,46 the state censorship system is regularly circumvented and challenged by savvy netizens using creative counterstrategies. As a result, undesired content has never been eliminated from the web, and censorship alters only the processes of its production, circulation, and consumption. Moreover, censorship is often counterproductive because it undermines regime legitimacy, politicizes otherwise neutral forum managers and netizens, and nurtures the development of rights consciousness, including calls for more than freedom of expression.47 On one hand, netizens’ experiences of being censored are hard lessons through which they learn about the regime’s repressive nature; on the other hand, the state’s efforts to disguise taboo topics also signal the regime’s fears, fuel netizens’ curiosity, and drive netizens to seek information on sensitive topics from unapproved, informal sources.

Neither, however, should we overestimate the power of netizen activism. Echoing the argument of “slacktivism,” online expression in China mostly remains a low-risk, low-cost form of political engagement, frequently more generative of private amusement than of collective action.48 This, of course, can be partially attributed to selective state censorship.49 But state control is not a sufficient explanation, considering netizens’ creative and artful contention. In this sense, one needs to go beyond the cat-and-mouse struggle over censorship, which captures only a small part of online politics, and examine what is actually going on within state-imposed boundaries.

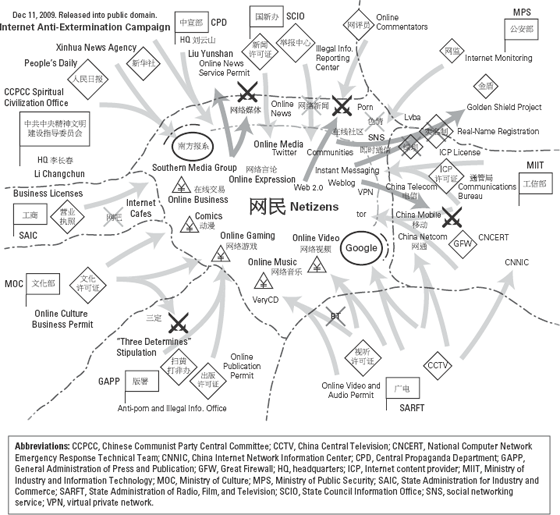

As the sociologist and communications scholar Manuel Castells puts it, “Violence and the threat of violence always combine with the construction of meaning in the production and reproduction of power relationships in all domains of social life.”50 If the struggle over censorship embodies violence and the threat of violence, discourse competition is one in which state and nonstate actors attempt to engineer popular opinion and construct beliefs, values, and identities online. Figure 1.3 shows the discourse competition scenario in which netizen groups championing different ideologies—liberalism versus patriotism—are fighting fiercely against each other, with onlookers watching what is going on.

FIGURE 1.3 Largest riot ever in history

Both the regime and its critics have taken advantage of the Internet to spread their preferred discourses. Among other more innovative propaganda strategies, political “astroturfing”—deploying the fifty-cent army to covertly manufacture seemingly spontaneous pro-regime content—represents an adaptation of the state to decentralized, fluid, and anonymous online expression. This would seem to be a smart move considering that overt state propaganda is increasingly ineffective. But deeper investigation shows that the persistence of old-fashioned propaganda work has rendered this seemingly shrewd strategy fruitless through the exposure of the existence of the fifty-cent army.

The state is not alone in the game. Many social actors have employed, anonymously, public relations (PR) strategies to advance their agenda online. In effect, tactics such as astroturfing and rumor spreading are natural weapons for regime critics and dissident groups who are constantly suppressed. However, though they might be effective in defaming the regime, such tactics can backfire by leading many netizens to imagine a group of national enemies conducting sabotage and espionage missions in Chinese cyberspace. As a result, rather than viewing the struggle over online expression as a story of social actors allying against the authoritarian state, many netizens develop an alternative framing in which regime challengers are depicted as betrayers or trouble makers. Thus, the struggle over online expression is framed as a counter-espionage story of Chinese patriots defending the nation against betrayers and their foreign sponsors. This framing not only demobilizes many netizens, but also contributes to the rise of a pro-regime discourse.

In fact, some netizens have developed a group identity as the voluntary fifty-cent army and have constructed online communities that sustain a regime-defending discourse.51 This identity is both passively imposed and actively constructed. It is passively imposed in that the netizens involved are labeled the fifty-cent army by other netizens furious at pro-regime expression owing to the state’s censorship and opinion-manipulation efforts. But as victims of labeling wars, they have glorified the disgraceful “fifty-cent army” label by depicting themselves as more patriotic and rational than most netizens—they believe they are defending the nation against online sabotage and emphasize facts and logic in debates. Through repeated interactions among themselves and with regime critics, members of the voluntary fifty-cent army reinforce their identity and sustain a robust pro-regime discourse.

The discourse competition reveals a divided Chinese cyberspace. Coherent and relatively independent communities either sustain a certain dominant discourse or become battlefields of multiple discourses as netizens with distinct political orientations coexist or compete. Interactions among both like-minded and rival netizens socialize Internet users in ways that reinforce their beliefs, which in turn consolidate their group identity.

In discourse competition, state and nonstate actors compete to manipulate popular opinion to their advantage. Unlike the censorship game in which coercive power plays a significant role, players in discourse competition mobilize through identity and expressive strategies. Aware of opinion engineering efforts by both the state and regime challengers, netizens engaging in public discussions are extremely anxious about each other’s true identity. This explains why both the state and regime challengers tend to engage in the game anonymously so as to avoid having their strategy backfire, while labeling becomes an effective way of defaming others.

It is worth noting that defamation and attack are the dominant modes of discourse competition on Chinese forums.52 Among the state and its supporters, efforts to construct and defend a positive image of the regime often prove fruitless, whereas denouncing regime critics as trouble makers and saboteurs is more effective. Among regime challengers who have been defamed and censored by the state, spreading negative news about the regime also works more effectively than posing as a viable alternative to the Party-state, particularly considering that ideological and financial links to Western powers are considered liabilities by nationalistic Chinese netizens.

ONLINE POLITICS, DIGITAL EMPOWERMENT, AND AUTHORITARIAN RESILIENCE

The struggle over online expression reveals that neither the state nor the Internet is monolithic and that the dynamics of state adaptation and popular activism go far beyond a state–society confrontation. Thus, examining interactions among multiple state and social actors in censorship and discourse competition not only provides a more balanced view of Internet politics in China, but also contributes to theoretical enterprises such as state–society relations, authoritarian resilience, and democratization theories.

A Fragmented State and Fragmented Cyberspace

According to Manuel Castells, “the relevance of a given technology, and its acceptance by people at large, do not result from the technology itself, but from appropriation of the technology by individuals and collectives to fit their needs and their culture.”53 An analysis of the struggles over censorship and discourse competition reveals fine-tuned and complex state–society relations in China, in which the state and social actors have both demonstrated great adaptability to new sociopolitical terrain. In the struggle over censorship, though the state enjoys the advantage of coercive power over intermediary actors and netizens, the latter group have evaded state censorship through technological know-how and creativity. In discourse competition, the actors involved, including the state and its critics, resort to grassroots PR strategies to engineer popular opinion. This mode of interaction has created an atmosphere of subterfuge and uncertainty in which participants’ beliefs, values, and identities are constantly contested. Such an atmosphere conditions netizens’ perceptions of various discourses, as well as their reactions and choices of strategies for online expression.

Both the struggle over censorship and the discourse competition demonstrate the need to disaggregate both the state and the Internet. The understudied role of local and departmental state agencies is particularly worth noting because their interests and motives have also incentivized control initiatives. For instance, while the central state is primarily concerned with the regime’s overall stability and legitimacy, local authorities take actions to maintain their own public image, demonstrate their competence to upper levels, or avoid political risks.54 As a result, they tend to boast about their propaganda achievements while endeavoring to stifle disclosure of local problems. Such actions do severe harm to the regime’s legitimacy because they not only disable the safety-valve function of online expression, but also intensify netizens’ enmity toward the regime.55 After all, suppressing tangible grievances is often more effective in provoking the wrath of Chinese citizens than abstract causes. Moreover, local cover-ups indicate the central government’s failure, or even worse, its lack of desire, to discipline local agents, which may erode trust in the central government and the regime.56

Likewise, recognizing the fragmentation of cyberspace is crucial to understanding Internet politics in China. Chinese netizens have approached the Internet with diverse and mixed purposes. For instance, chapter 4, on pop activism, discusses that online activism is more than a form of digital contention. It can be driven by both netizens’ contentious motivations and their pursuit of both fun and recognition. Moreover, as a strategy to promulgate information, pop activism is equally useful for both regime critics and regime supporters. In this regard, understanding online activism merely as a strike against state censorship or the regime has the danger of downplaying the richness of cyberpolitics and overestimating the Internet’s potential for civic activism and political change.

In addition, even politically motivated netizens demonstrate distinctive beliefs, values, and ideological inclinations. Given the pervasiveness of opinion-manipulation efforts by the state and its critics, Chinese netizens often are extremely anxious about each other’s identity and intention, which in turn facilitates the formation of coherent, relatively isolated online communities. Through repeated amicable interactions among community members and confrontations with rivals, netizens’ propositions and group identities are reinforced while the discourses they champion are produced and reproduced. Such a tendency in online expression only fortifies the fragmentation of Chinese cyberspace, preventing these “public sphericules” from evolving into the public sphere, as Johan Lagerkvist predicted.57

China’s Democratization Prospectus: Revisiting Authoritarian Resilience

What is the impact of online expression on authoritarian rule? Critics have warned against evaluating the impact of online politics merely in terms of whether online activism will lead to regime change.58 Yet focusing exclusively on online politics as a “gradual revolution” likewise risks reducing online activism to a “weapon of the weak”59 and shies away from the legitimate questions of whether and how online activism will contribute to possible regime change. Analyzing both the struggle over censorship and the discourse competition offers a testing ground for assessing authoritarian resilience.

Findings presented in this book suggest that it is necessary to rethink the basis for resilient authoritarianism. Struggles over online expression reveal the agility of the Chinese state in adapting and refining its capacity to deal with new challenges. Yet the regime’s adaptability cannot fully explain its “resilience” because the state’s censorship and opinion-manipulation efforts have often proved fruitless and counterproductive.60 Rather, the apparent resilience of Chinese authoritarianism in the face of the Internet’s liberalizing and democratizing impact is primarily a result of the fragmentation of cyberspace, the pluralization of online expression, and ultimately the lack of consensus on a viable alternative to the current system.

Chinese cyberspace is fragmented in a number of ways, particularly in that netizens have formed a wide range of groups, the majority along apolitically motivated lines.61 Failing to recognize this point leads to an overestimation of the Internet’s impact. In particular, netizen groups are organized around framings not limited to a binary struggle pitting freedom of expression against state repression. Despite the ineffectiveness of the state’s own efforts at popular-opinion manipulation, many are mobilized around an alternative frame depicting regime critics as saboteurs of national interests and call on netizens to defend the regime against the nation’s enemies.

Moreover, online discourse competition has helped discredit any alternative to the Party-state. In particular, the findings presented in chapters 6 and 7 suggest that nationalism is at odds with China’s nascent democratic movement, not because nationalistic citizens are disinclined toward democracy or swayed by state ideology, but because they are highly distrustful of democratic activists. An analysis of nationalistic discourses shows that regime critics are often depicted as voluntary or involuntary foreign agents who lack the capacity or will to represent and defend China’s interests. Take the 1989 student leaders as examples: Chai Ling was blamed online for risking other students’ lives for her personal ambitions,62 and Wang Dan has been accused of betraying China’s national interests by receiving funds from the United States and Taiwan’s pro-independent Democratic Progressive Party.63 Such distrust weakens regime-challenging voices online, forcing many regime challengers to deny their political ambitions in order to retain public sympathy.64

Evidently, to assess authoritarian resilience, one ought not examine only state capacity and adaptability, but also pay close attention to the strategies employed by regime challengers. This perspective helps explain why online expression is not as threatening to authoritarian rule as many have expected. Though freer online expression has empowered regime critics and eroded state legitimacy despite state control, such impact is partially neutralized by the pluralization of online discourses. Among others, pro-regime netizen groups such as the voluntary fifty-cent army have actively denigrated regime challengers and sustained a pro-regime discourse.

A Democratizing Internet or a Democratic Illusion?

The new source of authoritarian resilience that the book brings to light—namely, the weak base of support for challengers—has further implications for China’s potential for regime change and democratization. Though political scientists cannot study events that have not yet occurred, it is possible to examine whether and how online expression may contribute to democratic transition, since the process does not take place overnight. Indeed, regime transition does not start at the moment when the authoritarian regime collapses and/or a new regime arises. Long before the shift, society undergoes gradual, preliminary processes in which the regime’s authority is delegitimized and the values and ideas of an alternative regime are diffused. Since the Internet is a particularly vulnerable area of China’s authoritarian rule, it is an ideal place to observe this process. According to the China expert Johan Lagerkvist, online negotiations between conflicting Party-state, youth/subaltern, and transnational business norms will foster normative change and the erosion of state norms, moving the nation toward inclusive democracy.65 This book supports Lagerkvists’s argument for the erosion of state norms by emphasizing how online expression has helped delegitimize the regime, and how the state’s censorship and opinion-manipulation efforts have been largely fruitless and counterproductive. However, the optimistic expectation of a transformation toward inclusive democracy is not supported because the erosion of Party-state norms does not necessarily imply the emergence of liberal and democratic norms.

If understood as a process in which democratic rules and procedures are applied to previously undemocratic political institutions,66 democratization implies two phases: the collapse of the old regime and the establishment of a democratic one. Though online expression may be contributing to delegitimizing the current regime, it has done little to cultivate a pro-democracy discourse that spreads democratic values and ideas or even to mobilize netizens to struggle for a democratic regime. This echoes the political scientist and commentator Yongnian Zheng’s earlier observation that the Internet in China has contributed more to political liberalization than democratization.67 The ubiquity of defamation in discourse competition vividly demonstrates that both the authoritarian regime and its potential alternatives have been discredited, leading to the erosion of political authority in general. As Samuel Huntington pointed out, “The most important political distinction among countries concerns not their form of government but their degree of government.”68 Failing to indoctrinate netizens with democratic values and ideas or to convince them to support a democratic political order, the “liberalizing” effects of online expression may result in little more than the erosion of the authoritarian regime. For instance, after a series of brutal attacks on schoolchildren across China in early 2010,69 one picture started to circulate online with the slogan “Every injustice has its perpetrator, and every debt has its debtor. If you go out the door and turn left, you will find the government” (yuan you tou, zhai you zhu, chumen zuozhuan shi zhengfu, 冤有头债有主, 出门左转是政府). Clearly, netizens spreading the slogan had little respect for political authority, but saw the regime as the source of all social ills.

In fact, the Chinese Internet shows signs of excessive liberalization rather than democratization: The decay of authority is apparent in online expression of all types. Interpreting this purely as a sign of authoritarian pullback is misleading because it overlooks the erosion of social capital, which many social scientists consider crucial for a democracy to function.70 The Party-state’s authority is of course challenged in online expression, but so is trust in regime challengers and other social actors such intellectuals, journalists, lawyers, and even some nongovernmental organizations.71 In this regard, a closer examination of such detrimental effects, currently unaddressed in the field, improves on the democratization literature by arguing that certain governance problems that plague new democracies may be the legacy of the liberalization process, rather than legacies of the authoritarian regime per se.72

DATA

The book draws on data collected through online and offline research that includes interviews, offline participant observation, online ethnography, and sources such as media reports, official documents, and scholarly studies.

First, I conducted more than sixty online and offline interviews with forum managers, forum users, scholars, and media professionals between 2008 and 2011. The majority of interviewees were recruited through a snowball approach. As a veteran user of Internet forums, my personal connections proved crucial during the initial phases of data collection. In particular, such connections helped recruit several key interviewees who not only provided their inside stories, but offered connections to other sources. Most interviews with forum managers and veteran users were semi-structured, focusing on their experiences with and perceptions of online expression, state control, and forum governance. Some interviewees, particularly those from state media outlets, were reluctant to talk about their jobs in detail. But even their reluctance revealed a great deal about the sensitive relationship between the state and the online public.

During my fieldwork in China, I also participated in two state-sponsored conferences of university Internet forum managers in 2009 and 2010. At these meetings, I not only met with forum managers from across the country, but also observed how they exchanged ideas with each other and interacted with state and market forces, represented by sponsoring state agencies and companies, respectively.

Second, this book relies on data collected through in-depth online ethnographic work, which involved the long-term observation of selected websites with restricted engagement to avoid any problems of reactivity. The approach resembles what Guobin Yang advocates as online “guerrilla ethnography,” which emphasizes limited involvement, fluid movement in networks, and exploration of links,73 but underlines the value of long-term immersion in specific online communities. Based on a vision of the Internet featuring openness, fluidity, and connections, Yang argues that long-term ethnographic work on a few sites fails to capture the Internet’s real strengths and leads to tunnel vision. However, the very fluidity of online expression requires an approach that allows for the timely compilation of discussion threads (which can be removed at any time because of moderation or censorship) and accumulation of the fluid metis (i.e., practical experience and know-how)74 to read between the lines and accurately interpret the meanings and meta-meanings behind the texts. After all, the Janus-faced Internet features not only openness, fluidity, and connections, but also fragmentation, closure, and border restrictions. A concentrated focus on a few platforms helps bring into focus such underappreciated mechanisms that shape discourse competition, group identity, and community building.

The primary sites included in this research are Bdwm (bdwm.net), Ccthere (ccthere.com), Kdnet (kdnet.net), Mitbbs (mitbbs.com), NewSmth (www.newsmth.net), Qiangguo Luntan (bbs1.people.com.cn), and Tianya (tianya.cn). These forums are relatively large ones that attract more netizens and cover broader issue areas and thus are more influential and representative than smaller ones.75 To increase representativeness, this book covers both domestic (Bdwm, Kdnet, NewSmth, Qiangguo Luntan, and Tianya) and overseas Chinese forums (Ccthere and Mitbbs). These forums can also be categorized into campus (Bdwm), commercial (Kdnet and Tianya), individual (Ccthere), and state-sponsored (Qiangguo Luntan) ones. Mitbbs and NewSmth, though commercialized, bear characteristics of campus forums because they both originated at universities and attract large numbers of students.76 The research in this book is not restricted to these forums, however. Instead, they serve as focal points from which my study gradually expanded to other online territories. For instance, I first encountered the voluntary fifty-cent army on NewSmth and then followed their steps to other military forums such as Cjdby (lt.cjdby.net), Fyjs (fyjs.cn), and Sbanzu (sbanzu.com; the forum was closed permanently in 2016).

Additional sites for my online ethnography include platforms where forum managers exchange ideas and information on forum governance such as forum administrators’ forums,77 discussion boards,78 and instant messenger QQ groups.79 Both during and after the fieldwork period, I anonymously observed a few such platforms regularly. Ongoing conversations on such platforms provide a unique opportunity to learn about managers of various types of forums, as well as their concerns, practices, and strategies.

In-depth online ethnographic work also provides another important source of data aside from direct observations of netizen and managerial activities. Some forums, particularly campus BBSs, maintain historical data in their archival sections. Such data include forum and board histories, archives of online events and discussion threads, and texts of forum and board regulations. Online archives not only constitute an important and systematic source of how forum and board managers have governed their sites, but also provide an important source of information to check and confirm data collected through interviews and online observation.

Finally, sources such as media reports, official documents, and scholarly studies have also been crucial to my research. For instance, my analysis of online commentators, or the fifty-cent army, draws primarily on leaked official documents and media reports. Given the sensitivity of online opinion engineering, it might be surprising to find that official reports on the topic are sometimes made available. Yet, the state sometimes does not try to conceal information about the fifty-cent army because the online commentator system is regarded as part of its routine propaganda work. Indeed, local governments and propaganda branches often regard their success in this area as an achievement to boast about to higher levels. This explains why a local media report on the training of online commentators in Shanxi Province not only reported on the event, but also provided links to reports by other more influential news portals (e.g., 163.com and qq.com) and mouthpiece outlets (e.g., people.com.cn).80

There are potential ethical concerns with this research, especially in terms of the method of data collection for the online ethnography, as it involved observing human subjects without their explicit consent. Such concerns are legitimate, and it is essential to respond to these concerns here. First, the project’s study design went through the internal review board review process at the University of California, Berkeley, before it was implemented. Second, my online ethnographic work was done almost exclusively on platforms with free anonymous access, meaning that all user activities are essentially in the public domain. Only a few platforms included in this study require a membership to view their posts. But even these sites are public in nature as they impose no registration restrictions and allow anyone with a valid email address to sign up for an account. In short, all the information I obtained in my online ethnography is publicly accessible and thus does not constitute a violation of netizens’ privacy or a risk to them personally. To my knowledge, this is the standard, or at least an accepted, practice in the field. But to further protect the netizens, this book anonymizes them whenever possible. Third, my research has also used leaked documents from state agencies to analyze state intent and behavior online. This is not considered to present an ethnical problem either. Leading scholars such as Gary King and his colleagues at Harvard University have used similar sources in their research.

A PREVIEW OF WHAT FOLLOWS

Aside from this introductory chapter and the concluding chapter, the empirical chapters of the book fall into two major parts. The first part focuses on the cat-and-mouse censorship game, which highlights not only state–society confrontation, but also the intermediary actors at the crux of control implementation. Chapter 2 takes a state-centric perspective and analyzes how the Chinese Party-state has gradually adapted to the digital era by establishing the “world’s most sophisticated”81 censorship system. By discussing the institutional, organizational, technical, and administrative tools employed by the state, the chapter highlights the multi-agency, multi-level, and multi-means features of state censorship. The chapter also reveals how external challenges and internal fragmentation have contributed to the system’s rigidity and arbitrariness, which provide maneuvering room for both intermediary actors and netizens, but also occasionally incurs harsher censorship.

Chapter 3 discusses how intermediary actors such as forum managers have balanced state control from above and netizens’ challenges from below through “discontented compliance.” Though pervasively dissatisfied with censorship, most forum managers nonetheless help preserve state-imposed limitations on online expression, largely because they cannot afford open disagreement. Yet they also engage in everyday forms of low-profile resistance and occasionally turn a blind eye to or even encourage boundary-spanning expressions. The chapter also explores how the affiliation, scale, and primary purposes of Internet forums affect their choice of strategy and thus their position along the discontent–compliance spectrum.

Chapter 4 focuses on netizen activism and explores not only how netizens evade and challenge censorship in innovative ways, but also how they have gone beyond activism against censorship. It argues that Chinese netizens are far from apolitical and have actively engaged in anti-censorship resistance, but many also participate in online activism for entertainment and may target dissident groups, political activities, and foreign actors. In other words, netizen activism has gone beyond “digital contention.” Thus, an analysis of netizen activism must accommodate a much broader spectrum of actors and strategies in order to accurately assess the impact of online expression.

Chapters 5, 6, and 7 examine discourse competition and popular-opinion engineering. Chapter 5 explores the state’s adaptation beyond censorship. It focuses on the Internet commentator system and details the recruitment, training, functions, and remuneration of the fifty-cent army. The analysis in this chapter shows that Internet commentators are often not properly trained or incentivized and are motivated more to demonstrate their competence to upper levels than to persuade netizens. As a result, the seemingly smart move often causes more trouble than it resolves, as it frequently backfires and chips away at the legitimacy of the Party-state.

Chapter 6 explores how regime challengers take advantage of the Internet to spread regime-challenging voices and how their efforts ironically feed into the state propaganda of a “handful of subversive forces.” Echoing state propaganda, nationalistic netizens have developed a pro-regime discourse that defines dissidents, political activists, and foreign forces as national enemies, with the authoritarian state represented as a “necessary evil” to defend national interests. In this way, the struggle over online expression is completely reinterpreted: It is no longer a struggle by concerned citizens against the repressive state for freedom and democracy; it is a national defense war in which patriotic netizens side with the regime to defend China against online saboteurs.

Chapter 7 furthers the argument of a fragmented cyberspace by studying a particular netizen group who call themselves the voluntary fifty-cent army. By examining their repeated interactions with both opposing netizens and fellow community members, the chapter explains how the group has constructed a group identity and sustained a regime-defending discourse. This chapter takes the understanding of online expression in China beyond the empowered-society-versus-repressive-state framework to one that embraces conflicts among social actors themselves. It also shows how freer online expression may unexpectedly work to the advantage of the authoritarian regime.

The concluding chapter discusses the implications of my research findings. It emphasizes that the struggle over online expression is a process shaped by the internal interests and ideological fragmentation of the state, the diverse capacities and agency of intermediary actors, and the heterogeneous identity, values, and beliefs of netizen groups. In particular, it highlights the mismatch between the Party-state’s capacity and the challenges presented by the digital age, which explains why the state has had tremendous difficulty translating its power into effective online control. But since regime critics have yet to win netizens’ hearts and minds, any expectation of imminent democratization is likely built upon a miscalculation of the Internet’s threat to authoritarian rule.