8

The Setting

The Parties

Oriel College’s Buttery Books, which record charges for food and drink, show that young John Bankes arrived in June 1643, a month before his matriculation on 10 July 1643, and continued in residence through 1644, including the summer. Entries for him cease in the fall term of 1644–5, covering, in all, six terms and a week. As a fellow of Oriel, Maurice Williams ran up buttery bills throughout the same period and left the college five weeks after John did, although he remained on its books into 1646. Perhaps John withdrew late in 1644 to be with his father, who by then was seriously ill. Williams may also have attended Sir John, who died on 28 December 1644.1 Our picture probably dates from the period when Bankes and Williams resided together at Oriel.

John Bankes’s Oxford offered much to inquisitive minds unaffected by stench and overcrowding. The town and university had to accommodate the royal court, cavaliers, hangers-on, a large garrison, and the means of making war. Magdalen College hosted workshops and an artillery park, Christ Church a cannon foundry, New College a powder magazine, and the Schools storehouses: uniforms in Music and Astronomy, grain in Logic, and (someone still had a sense of humor) Corn and Cheese in Law.2 Charles and his immediate entourage occupied Christ Church; Henrietta Maria and hers, the Warden’s accommodation at Merton; the queen thus replacing Nathaniel Brent, who, having served Laud slavishly, had judged it expedient to throw in his lot with parliament. At Oriel, located between the colleges occupied by the royal couple, the Executive Committee of the Privy Council, to which Sir John Bankes belonged, held its meetings. The king and queen held theirs too, through a special passage erected through the gardens of the intervening colleges. In June 1643, Charles invited, and in December ordered, parliament to assemble in Oxford. The loyalists who obeyed amounted to 83 lords and 175 commoners.3

In all, some 3,000 “strangers” served and protected the court, ran the military enterprises, established a mint to coin silver plate extracted from the colleges, and catered, victualed, and fortified the town, an increase in population of over 30 percent. Good accommodation became scarce, overcrowding inescapable; soldiers were quartered on citizens, ladies on colleges, aristocrats on grocers. Sir Richard and Lady Fanshaw can stand for them all. The family fled from its fine apartments to “a baker’s house on an obscure street…a very bad bed in a garret…one dish of meat, and that not the best ordered.” The Fanshaws had no money or spare clothes. They spent their time looking out of their window at “the sad spectacle of war, sometimes plague, sometimes sickness of other kinds.” Their daughter did better. Mistress Fanshaw obtained lodgings at Trinity College. Perhaps, like her friend who lived at Balliol, she employed a lutenist to alert admiring collegians to her comings and goings.4

The city’s filthy streets and rivers brimming with animal carcasses combined with close living to invite the scourges witnessed by Lady Fanshaw. In summer of 1643, an epidemic of typhus imported by soldiers hit Oxford. Rats multiplied in the grain stores, and citizens died by the score. The City ordered the bailiffs to remove the pigs from the streets. Physicians recommended eating garlic, which might have helped by discouraging intimacy. Was the outbreak the plague? No, no, said the royal doctor Edward Greaves, that is enemy propaganda: we are dealing with a malignant fever. Has God sent it directly to punish our sins? No, God works through secondary causes, which we can combat. Are the stars the cause? No. Look rather to dirty streets, bad beer, filthy dishware, and the unwholesome army. Besides cleanliness, good air, mild purges, spare diets, and soporifics, cordials, and other ancient remedies can alleviate symptoms. The greatest danger is to fall into melancholy. Therefore, Greaves advised: “Be Cheerful and Pleasant, as far as the disease will give leave, avoid all sad thoughts, and sudden passions of the mind, especially Anger, which addes fire to the [fever’s] Heat, inflames the Blood, and Spirits, and at length, sets the whole Fabrick in Combustion.”5

And yet, for those with good health, insensitive noses, and strong stomachs, Oxford during the first years of the Civil War, when the Royalists had reason to think they might prevail, was an exciting place, full of soldiers, gallants, men of action, ladies, spies, schemers, crooks, and prostitutes. Students had a broad real-life education under Oxford’s dreamy spires. They came in contact with cavaliers occupying rooms in their colleges and with soldiers with whom they worked on fortifications, thereby becoming, according to an eyewitness, “much debauched.”6

Oriel fared better than most of the colleges. In 1643, only nineteen strangers appear on its books, including a lady. The king’s demand in January that all colleges send their silver plate to the new mint weighed less heavily on Oriel, which surrendered £82, than on All Souls (£253) and Magdalen (£296). Further to the war effort, Oriel probably accommodated the editorial office of Mercurius aulicus, a weekly news and propaganda sheet, begun in January by Peter Heylyn, the author of Mikrokosmos and Laud’s collaborator in hounding Prynne.7 The hound and hare changed places with Laud’s fall and Prynne’s rise; found “delinquent by Parliament,” Heylyn retired to Oxford, where, in the capacity of a royal chaplain, he practiced as a spin doctor.8 He soon hived off his Mercurius to another of Laud’s protégés, John Birkenhead, and occupied himself rewriting history. He concluded that the archbishop’s “martyrdom” (which had yet to take place) was the forerunner and herald of all subsequent troubles. Troubles aplenty there were already, owing, according to the yet-to-be-martyred Laud, to Charles’s sacrifice of Strafford. “[Knowing] not how to be, or to be made, great,” the king acquiesced in the murder of his minister and released the forces that would destroy him.9

One who tried to make Charles great was Henrietta Maria. While abroad pawning jewels to purchase the stuff of war, she urged her husband to concede nothing to his enemies. Her return to England in February 1643 showed the iron of her constitution. She landed her supplies at a village in Yorkshire closely pursued by five ships commanded by rebels. They parked offshore and amused themselves at night by shelling her lodgings. She scrambled out of bed. The fusillade continued. “I was on foot some distance from the village and got shelter in a ditch. But before I could reach it the balls sang merrily over our heads and a sergeant was killed twenty paces from me.”10 The tough queen proceeded to York, where she stopped for the winter. In the spring, as she prepared to travel to Oxford with her 150 carriages of arms and ammunition, parliament impeached her for high treason. Her arrival in Charles’s new capital in July was perhaps the high point of the war for the Royalists. The king sallied out to meet her with a cavalcade of lords, officers, and servants. The royal reunion moved the sensitive soul of Mercurius aulicus: “Cursed will they be (and so find themselves by this time) who forced so tedious a separation of these sacred bodies, whose soules are so entirely linkt in divine affection.”11

The University Orator, William Strode, who in happier days had entertained her with The Floating Island, welcomed her back to Oxford with prose more purple than Mercurius’s.

Most Gratious and Glorious Queene…[your] Absence, so barbarously forc’d with danger, so bitterly perused with Calumnies, so patiently born, in leaving that Company out of pure love which you most Lov’d, in sequestering your selfe from the Armes of Your Royall Husband to furnish His Hands with Strength, to send him the sinewes of Mars for the Venus-like Brests which you carried hence, such an absence, after perills by Sea and Land, now turn’d to a powerfull Returne, calls us out of ourselves; our Spirits beyond our Eyes, our Hearts before our Tongues, to greet your most desired Presence; which, in beholding Your Picture, we longed for, and in beholding Your Person, we are ready to dye for …12

Strode’s extravagance ends a book of welcome-home poems to which young Bankes and his tutor contributed Latin verses. Bankes: “O Queen, we celebrate the indomitable ardor of your love!” We know that you once fearlessly exposed yourself to Charles, when he was confined to bed suffering from a disease that turned him an “unbecoming shade of scarlet.” You have performed heroically again, heedless of personal safety, in running the risks, dangers, perils, of wind and wave, land and sea, and armed enemies. “Fearing nothing, Maria triumphs.” Williams: “six glasses [of wine] to dry Charles, two-thirds to each of the children [Carolidi], nine to Henrietta!” With wine there must be verses. “We take pleasure in amiable [facili] Charles, while we sing of Maria.” From these hints, we guess that Bankes and Williams agreed with those who regarded the queen as determined and uncompromising, and the king as indecisive and uxorious.13 Their poems suggest the familiarity of neighbors, who could refer to the complexion of the king and order bumpers for the queen, rather than the distance of subject from sovereign. She knew both of them, Bankes as the son and heir of her husband’s top lawyer, Williams as one of her own physicians.

The campaigning season of 1643 left military matters much as they were at the end of 1642. During the summer of 1644, however, the Royalist position declined along with the number of students at the university. Rebel forces were closing in. Charles fled in June across the Cotswolds to Worcester. Henrietta Maria had withdrawn in April to Exeter, ill and pregnant, attended by Mayerne and Lister. According to the spin doctors at Mercurius aulicus, “Her Majestie made choice to enjoy the present peace and quiet of [the West], rather than Oxford, where she was in the middest of H.M.’s Armies, which afforded security but too much noyse and businesse.” She gave birth to a daughter in mid-June and left for France on 13 July, not to return before her son had succeeded his martyred father.14

The peculiar situation in Oxford bred some tolerance. The pamphlets of Sir John Spelman (son of the antiquary Henry Spelman), who would have been Secretary of State had camp fever not carried him off in 1643, hinted how tolerance might fit the fuzzy concept of mixed monarchy. A frontispiece designed by Sir John’s father, drawn by Marshall, and used for Thomas Fuller’s The Holy State (1642), represents the guiding idea. As in Strafford’s concept of government, the king is the keystone of an arch resting on the twin pillars of church (whose plinth is Holy Scripture) and state (whose plinth is Common Law). Inclining on the arch supported by the sacred writings, naked Truth tans under an emblem of the sun; her clothed opposite number, Justice, carries a sword and scales.15

Spelman explained that laws bind kings, but in a peculiar way, “in Honour, in Conscience between God and them.” The fuzzy state can survive and prosper only if the people, when suffering under ill-intentioned leaders, do not force confrontation. King Charles’s cause did not pit the royal prerogative against the subject’s liberty, “but libertie [against] Ochlocracie [mob rule], the established protestant Religion [against] scisme and heresie.” Most judges, divines, and lawyers, “the visible major part of those Seminaries of Learning the Universities, and the Inns of Court,” and educated people in general favor the king and the mixed constitution of the state.16 He was their sovereign, and yet he was not. He could make no laws without parliament. Although head of the true Protestant church, he could not refuse his protection to his loyal Catholic subjects. The great question was “whether learning, Law, the flower of the Nobility, the best and choyce of the commonality” could manage to muddle through.17 Charles might have led such a coalition had he practiced the advice he offered his successor: allow religious dissent in matters only probable; keep the middle way, listen to many, yield in small things; enforce civil justice and the laws of the kingdom; show no “aversion or dislike of parliaments;” and beware of covert innovators who mask their “thirst after novelties…with the name of reformations.” And, while granting what should be granted to an obedient and grateful people, preserve what should be preserved of the majesty and prerogative of a king.18 Not an easy program!

Within the Holy State illustrated by Spelman’s frontispiece Fuller described the sorts of citizens needed to maintain a moderate, balanced, forbearing Christian polity. Our protagonists are among them. The healthy state needs “the general artist,” that is, young John Bankes, who “moderately studieth [mathematics] to his great contentment,” but does not allow it to “jostle out other arts.” He entertains but does not believe in judicial astrology. He must know history, without which “a mans soul is purblind,” but cannot unless he first master chronology, without which “history is at best a heap of tales.” And he must be acquainted with the universe, through a smattering of cosmography. If the general artist were also a true gentleman, as was young Bankes, he would be as studious at the university “as if he intended Learning for his profession.”19 He would not copy the “pretender to learning,” who looks over books in Greek only when people are looking over his shoulder; nor the true scholar, awkward, unsophisticated, and melancholic, “his minde [being] somewhat too much taken up with his mind.”20

Another necessary citizen, the good judge, exemplified by Sir John Bankes, is patient, attentive, upright, merciful, and above bribery. Where justified, he decides fairly in suits against the sovereign. Kings may not at first like this independence, but they will come to “see with the eyes of their Judges, and at last will break those false spectacles which (in point of Law) shall be found to have deceived them.” Had Charles only listened to Bankes! But why should he? “He is a mortall God…He holds his Crown immediately from the God of Heaven.” The good king should be pious, loving, generous, just, and merciful, and also humble, like Charles, who disliked being praised. “His Royall virtues are too great to be told, are too great to be conceal’d.” Fuller’s description of the good physician fit Williams better than his sketch of the ideal sovereign did Charles. A good physician does not diagnose on the basis of one vial of urine, or experiment on his patients with new or exotic drugs, or hide from them their approaching deaths.21

Charles did not need Fuller’s exhortation to accept the obligation to protect all his loyal subjects, including Catholics. He had to shield them, among other reasons because he could not wage war without them. They had succored him when he was destitute at York and continued to supply him at Oxford. About a third of the gentry families in the county were Catholic. Their distant chief, Pope Urban, sympathized with their king’s cause, although, as he wrote with undiplomatic realism, all the treasure in Castel Sant’Angelo would not recover the crown Charles had lost by his concessions in Scotland. Still, if Charles indicated his intention to rejoin the old religion …22 Charles refused this stale impossible condition. But, while publicly declaring his faith in and support of “the true reformed Protestant Religion, as it stood in its beauty in the happy daies of Queen Elizabeth,” he allowed Catholics to attend mass openly in Oxford. There may have been many of them, for Laud had warned that Jesuits were at work in the university helped by the holy water at the Blue Boar, the Mitre Inn (reputed to be a recusant hangout), and other pubs in town owned by Catholics.23 This was very different from the situation Henrietta Maria had experienced during her previous stay in London.

Imagine how I feel to see power wrested from the King, Catholics persecuted, priests hanged, our servants fleeing for their lives for having tried to serve the King…It seems that God wants to afflict both of us…but my afflictions are greater, for the suffering of religion is above everything.24

The relatively tolerant Oxford of 1643 harbored representatives of many of the sects and religions that Andrew Ross lovingly disparaged in a catalogue he published in 1642. Heading the list, “the worst of all Creatures,” was the Atheist, followed immediately by the Papist, who “acknowledges no High Power but the Pope.” The half-Papist Arminian came next (leaving aside Jews), lusting after a hierarchical clergy, “Altars, Cushions, Wax-Candles…with many other superfluous Ceremonies.” Ross did not overlook Libertines, “so overcome with the flesh they cannot pray;” Communists, who enjoy wives and other things in common; Anabaptists, Waiverers, and Time-Servers, with no fixed church; Canonists, who want, and Lutherans, who do not want, bishops; Separatists, who rightly decry bishops but wrongly admit lay elders; Brownists or Quakers; and Puritans, “the most commendable,” who long to follow the Scottish kirk.25

Ross left for last Rattle-Heads and Round-Heads, equally misguided, who were already at loggerheads. The Rattlers are “haire-brain’d, spittle-witted coxcombes with no time for law or religion”—that is, Cavaliers, “[who] regard nothing but to make mischief, build castles in the Ayre, hatch Stratagems, invent Projects.” The Rounders, though desiring orderly performance of church services, “yet they are the chief Ring-Leaders to all tumultuous disorders, they call the Common Prayer Porridge, and they will allow no doctrine for good, nor any Minister a quiet audience, without he preach absolute damnation.” The catalogue ends with its pious compiler “Praying to God the Author of true peace ǀ That truth may flourish and dissension cease.”26

For six months or so after Bankes had joined his king at York, he worked for truth and against dissension. He remained persona grata to parliament, which asked that he be kept in his place as Chief Justice. After the failure of the last efforts toward peace, however, he subscribed liberally to Charles’s cause and, in the spring of 1643, addressing a Grand Jury in Salisbury, accused Essex and other parliamentary commanders of high treason. Parliament responded by ordering his impeachment and the forfeiture of his property. A parliamentary force besieged his castle. Lady Bankes commanded the defenses of the upper ward with a force consisting of her daughters, maidservants, and five soldiers. The siege lasted six weeks before the Roundheads withdrew with more than 100 casualties. Sir John was then able to rejoin his heroic mate and create their fourteenth child, who entered upon the miseries of this world in June 1644. The following July parliament repeated its order depriving the Bankeses of their property and charged Sir John with high treason for giving judgment the previous December against its generals. It was a devastating blow to so faithful a public servant, to a man of whom contemporaries said, as Tacitus did of Rome’s great general and architect Agrippa: “There was this very rare about him, his affability did not lessen his authority, nor his severity diminish his love.” He had done his best. But he failed, as did all other wise and well-meaning councilors, to bring the king to agree to a compromise long enough to effect it.27

The distress Bankes felt at his treatment by parliament and his inability to prevent or blunt the oncoming disaster might well have hastened his death. He was buried in Christ Church, where he could continue to witness Charles’s ineptitude. His epitaph reads, after a recital of his various offices, “Peritam integritatem fidem ǀ Egregie praestetit,” “he stood far above others in knowledge, integrity, and honesty.” For once an honest monument! After all his work and service, he died land poor. Besides Corfe Castle, he had property in London and elsewhere, but a recorded income at death of only £1,263.28 He left various benefactions, a portrait of himself in the robes of Chief Justice (see Figure 16), and an admonition to his son John. “My eldest sonne must be contented to follow his studyes until he attaine the age of 24 yeares and to spend his time at the universitie, Innes of court, or travail, and when he enters upon his estate he is to be helpful to his brothers and sisters.”29 John would choose travel.

He could not return home. Toward the end of 1645, regiments of Cromwell’s New Model Army tried their luck at Corfe. They put their artillery in the village church, stored their powder in organ pipes, made missiles from the lead roof, and fashioned shirts from surplices. Despite these pious preparations, Lady Mary’s troop held out again. On 7 February 1646, a passing detachment of Royalists relieved the siege. Nine days later, betrayed by one of the officers left there, an inglorious Colonel Pitman, the castle fell. Perhaps he would not have acted so if Lady Bankes had been there. She had left her castle, perhaps soon after Sir John’s death, in order to improve her position in compounding for her estates, which she did with the help of her co-trustee of young John’s inheritance, the Mr Green to whom Sir John had described his increasingly difficult relations with the king. Since Lady Mary was in or around London with her unmarried daughters from July 1645 until March 1646, she was spared the sight of her neighbors stealing her furniture and Corfe’s conquerors demolishing her home.30 Neither she nor her sons could recover its valuable paintings or tapestries, although its library, which included some of Noy’s books, survived for a time. By Act of Parliament, it went intact to Sir John Maynard, an eminent lawyer and parliamentarian who served on the committees that condemned Strafford and Laud. Maynard became a Royalist champion in good time and had the opportunity to restore the books to Bankes’s heirs, but few have made their way to the library at Kingston Lacy.31

The Audience

John Greaves

Astronomy in Oxford had a tinge of the exotic about it. The astronomer Bainbridge taught himself Arabic to be able to read his Muslim predecessors directly, lest he be “hoodwinked” by Arabists who knew no astronomy. He found it hard going, he told Ussher, “but the great hopes I have in that happy Arabia to find most precious Stones…do overcome all difficulties.”32 As part of his program to encourage the study of mathematics and Eastern languages at Oxford, Laud commissioned a former fellow of Merton, John Greaves, who would succeed Bainbridge as Savilian professor, to hunt up Arabic manuscripts for him in the Middle East. Greaves intended also to measure the latitudes of eastern cities. For this enterprise he had the support of another powerful bishop, Laud’s protégé William Juxon, risen to Bishop of London and Lord Treasurer of England. Juxon knew that such work as Greaves proposed was much desired “by the best astronomers, especially Ticho Brahe and Kepler…as tending to the advancement of that science.”33

In 1631, after graduation from Balliol (1621) and further improvement under the Savilian professors, Greaves became professor of mathematics at Gresham College, London, with the support of Bainbridge, Brent, and Abbot. He soon gained leave to study in Padua. He went on to Rome, where he ran into Harvey at the English College, and had serious talk with the Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher (on magnetism), Cardinal Bentivoglio (on foreign travel), the Barberinis’ librarian Lucas Holstein (editions of Copernicus), and Galileo’s disciple Gasparo Berti (the sights of Rome). Greaves’s easy travel in Italy suggests an easygoing religion, if not crypto-Catholicism.34 His commission from Laud to live and collect among Muslims further evidences his courage and tolerance.

Greaves’s most splendid acquisition on his trip to Arabia was a copy of Ptolemy’s Almagest stolen for him from the library in the Seraglio in Istanbul, “the fairest book [he wrote] that I have ever seen.” What other fair things did he see or hear there? Enough to add some particulars to a book about the seraglio composed by Ottaviano Bon, an intimate of Sarpi’s circle, who served as the Venetian agent in Istanbul between 1604 and 1608. Bon’s book describes the exotic life of the seraglio diplomatically, with an occasional titillating detail. Item: the “young, lusty, and lascivious wenches” of the harem had a taste for cucumbers, which were never served them whole, “to deprive them of the means of playing the wanton.”35 Greaves’s version of Bon and other results of his exotic travel made him an unusually alluring professor of mathematics.

As a travel writer Greaves tended more toward arithmetic than ethnology. He reports of his visit to Santa Croce in Florence that its holy relics include a nail of the true cross (weight, a shilling and sixpence), and two thorns from Christ’s crown (length, 2 inches). About St Peters and the Pantheon in Rome he records little more than their linear dimensions. But he was able to work out the length of an ancient Roman foot, which he reported in a book dedicated to Selden, and the exact size of the pyramids.36 In Venice he admired the glassworks—not for giving beautiful ware to the world, but for providing good lenses for Galileo. No more than two such lenses existed, the professor of mathematics in Siena told Greaves, after neither of them had managed to see more than one of Jupiter’s satellites through the telescope they had to hand.37 The instrument Greaves had brought with him sufficed, however, to measure the latitudes of Constantinople, Rhodes, and Alexandria to a new degree of accuracy. He published these data, with due criticism of his predecessors, via a letter to his friend Ussher.38

For much of his journey to the east, where he spent over a year between stays in Italy, Greaves had the company of the first incumbent of Laud’s chair of Arabic, Edward Pococke. After returning to his professorship at Gresham College in 1640, Greaves visited Pococke and other colleagues in Oxford from time to time, and so was on the spot when Bainbridge died. He “immediately” succeeded to the Savilian chair, “either because of the pure faith [he] reposed in the King or because of greater expertise in universal mathematics.”39 He was entirely at home, almost literally, for, besides the society of his cronies Harvey, Pococke, and Ussher, he had the company of his brothers Edward (the royal physician), who had studied at Padua, and Thomas (a Fellow of Corpus Christi), who had learned Arabic from Pococke and translated a portion of the Qur’an. There is good reason to think that Maurice Williams made part of the company of physicians, mathematicians, and orientalists around Greaves and his brothers, and that young John Bankes was one of Greaves’s students.40 Certainly Sir John Bankes knew the merit of the new professor. He was on the committee that elected Greaves.41

Like many sevententh-century mathematicians, including Galileo, Greaves had an interest in finding longitude at sea. He preferred a method using our moon rather than Galileo’s scheme of exploiting Jupiter’s.42 Unlike Galileo, he had experience in long voyages and allowed himself a sneer at idle “persons of quality” who looked down on navigators and other practical folk. Among such idle persons could be found fools who still opposed the Gregorian reform of the calendar because a pope had brought it forth. Greaves proposed to eliminate the calendrical discrepancy between Britain and Europe by making ten successive leap years ordinary ones. His advice did not prevail; Britain remained Julian until 1752. It would be wrong to say that Greaves’s applied chronology had no positive outcome, however, for it helped Ussher to discover when Adam lived.43

Doctors of Body and Soul

When William Cavendish was called to court in 1638 to instruct the future Charles II in horsemanship, perhaps with Hobbes’s “Considerations touching the facility or difficulty of the motions of a horse” in his saddlebag, the Cavendish’s mathematician, Robert Payne, arrived in Oxford, perhaps clasping his copy of Galileo’s Systema cosmicum. Payne’s official post was chaplain of Christ’s Church and soon also royal chaplain, thus becoming a colleague at-a-distance of Alexander Ross, the scourge of novelty-mongers.44 Payne found himself thoroughly at home with the sort of science flourishing at Oxford around 1640, which produced, among other curiosities, a disputation at Queen’s in 1638 on ocean tides and lunar life.45

Payne’s fellow chaplain Chilmead had just published his translation of Hues’s Tractatus and was turning his attention to music. In the manner of Williams, he developed his ideas in a critique, or “Examination,” of questions posed by Bacon. His most penetrating analysis answered the question, why the sound of a bell depends on how it is struck, via an extraordinary analogy to the Copernican system. A bell has the ability to vibrate in different ways simultaneously, “which [modes] are to be conceaved to stand with the [fundamental] Primigeniall Motion, as the Copernicans, in their Sphericall doctrine, conceave the Earth, to make 365 circles in the Diurnall Motion, while it is finishing One Annual Course about the Sun.” Chilmead left this magnificent simile in manuscript lest it and other bits of his “Examination” offend the growing band of Baconians in Oxford, “so over-ruling is the name of Ld Verulam.”46 The fans of Bacon, “our English Aristotle,” had raised their standard at the university in 1640, in an amusing frontispiece to the English edition of De augmentis (see Figure 60).47

Many learned Royalists took up or continued residence in Oxford while Charles held court there. Physicians abounded. There were Dr Thomas Clayton, the Regius Professor of Medicine, an enthusiastic Royalist who trained companies of scholars for military service; Mayerne, attendant on Henrietta Maria, pregnant again after the joyful reunion of the royal couple in the summer of 1643; Williams, attendant on young John Bankes; and the score or more of fresh MDs created in 1642–3 by royal order, some of them deserving, like Walter Charleton, but others with few qualification beyond being gentlemen. This batch process exceeded the normal output of Oxford MDs by a factor of ten, creating a light Royalist counterweight to the London College of Physicians, which had a preference for parliament.48 Sir John Bankes knew some of the doctors of Oxford as he had had to clear up legal questions about Clayton’s royal professorship.49

Several of Oxford’s many doctors collaborated with Harvey, who moved to Merton as Warden in 1645. He owed this preferment to Greaves, who had consulted him on the pressing problem of breathing in pyramids, and, as Merton’s Sub-Warden, had petitioned Charles to deprive the absentee rebel Brent of the wardenship. The wheel of fortune continued to spin, however, and Brent, returning in 1648 as President of the parliamentary committee appointed to review the university, turned out the brothers Greaves.50 The charges against John Greaves were alienating college property for the king’s use, being overly familiar with the queen’s confessors, and causing the ejection of Brent. Anticipating that he would be removed, Greaves resigned in favor of Seth Ward, a former student of Oughtred, an informed and reliable Copernican.51 Ward became a close colleague of Wilkins, Galileo’s first English popularizer, who, having married Cromwell’s sister, returned to Oxford in 1648 as Warden of Wadham. According to Ward, writing in 1654 but referring to a pre-existing condition, no one at Oxford able to understand astronomy was Ptolemaic, most being Copernicans “of the elliptical way.”52

Several doctors of divinity and their friends in and around Oxford would have been able to recognize the Galilean reference in Cleyn’s painting. They included King Charles’s chaplain and Prince Charles’s tutor, Bishop Brian Duppa, formerly Dean of Christ Church and Vice Chancellor under Laud, and Duppa’s friend Justinian Isham, a future fellow of the Royal Society. Isham joined Charles in Oxford just after Edgehill and befriended young John Bankes, perhaps through Williams, whose interests in Baconian philosophy he shared. Duppa’s disciple and Bankes’s protégé Jasper Mayne often visited Oxford from his benefice in nearby Cassington.53 Nor can we forget the disputatious Peter Heylyn, who returned to his Mikrokosmos after whitewashing Laud. Aristotle might have written the account of the world system in the early editions of Mikrokosmos. In the new version, retitled Cosmographie, Heylyn silently acknowledged modern astronomy by saying nothing about the earth’s place in the universe. “For though Truth be the best Mistress that a man can serve…yet it is well observed withall, that if a man follow her too close at the heels, she may chance to kick out his teeth.”54

Men of Great Tew

Among those who migrated to Oxford with the king was Lucius Cary, Viscount Falkland, of the near-by village of Great Tew. During the 1630s he had kept open house in the village for a circle of philosophers, divines, and poets, and had opposed key Crown policies. He had refused to pay ship money, which he blamed on evil councilors, and led the Long Parliament’s attack on the judges by whom “a most excellent Prince hath been most infinitely abused…telling him he might do what he pleased.” And he was one of the spears who headed the prosecution of Strafford in the Lords. Nonetheless Charles made him a Secretary of State. That was in January 1642. Falkland did not want the job but yielded to pressure from his intimate friend Edward Hyde, the future Lord Clarendon, who was acting as Charles’s mole in parliament. Falkland and Hyde were with the king at York in June. There they made common cause with Bankes to nudge the king toward compromise; but, although they had greater access than the Chief Justice, they had no better luck. Their moderate views, in religion as well as in politics, were not opportunistic: they had a reasoned position characteristic of the men of Great Tew.

Falkland had developed his tolerance, improbably, in Ireland, where his father had governed, unsuccessfully, as Lord Deputy in the 1620s. Cary (as he then was) graduated from Trinity College, Dublin, fluent in Latin and French and aware that Catholics and Protestants could live together if they tried. He experienced standard prejudice in his immediate family: his maternal grandfather disinherited his mother for becoming a Catholic (and for other reasons too), and his unsuccessful father almost disinherited him for marrying a penniless girl. After death removed the grandfather and old Lord Falkland, the well-to-do new Lord Falkland and his loving and learned and no longer penniless wife began to draw out their intellectual circle. But religion continued to split the family. Falkland had charge of two of his younger brothers, to bring up as Protestants. His incorrigible mother kidnapped them and sent them to France to be raised as Catholics. They became Benedictines, as did four of their sisters.55

“All men of eminent parts and faculties in Oxford” belonged to, or sympathized with, the teachings of Tew; or so Hyde in retrospect defined the reasonable people at the university. Falkland’s circle included the enlightened from many walks of life, some of whom we know: Galileo’s translator Robert Payne, Charles’s intimate Endymion Porter, and Cleyn’s patron George Sandys.56 Sandys’s “graver Muse [had] from her long Dreames awaken[ed]”—that is, by the late 1630s he had switched from translating the Metamorphoses of Ovid to paraphrasing the Psalms of David. (“The Lord my Shepheard, me his Sheep ǀ Will from consuming Famine keep.”) As psalmist, David inspires; as king, exemplifies. Sandys took David to be exemplary, because he submitted to the law; and it troubled him, as it did most others at Tew, to see Charles increasingly deviate from this standard.57

Tew’s political message appears more plainly in the lengthy poem Falkland contributed to Sandys’s Paraphrase. It begins praising the author’s earlier writings for “Teaching the frailty of Human things ǀ How soone great Kingdoms fall, much sooner Kings,” and ends criticizing those who would criticize Sandys for mixing eloquence and things divine. “[A]s the Church with Ornaments is Fraught ǀ Why may not That be too, which There is Taught?” But this line too was decoration: Falkland’s main point was tolerance, not ornament. Like Saint Paul, “Who Iudais’d with Iewes, was All to All,” the church must be open to different approaches to the same fundamental beliefs.58 Falkland made all this clearer and longer a year later in his Of the Infallibilitie of the Church of Rome (1637), which argues that, as no religion possesses the full truth, it is absurd and dangerous to quarrel over adiaphora.

Tew’s tolerance followed in the tradition that George Sandys’s elder brother Edwin had set out in the evenhanded survey of the state of Europe around 1600 with which this story began. The leading men of Tew thought that the Anglican Church was the most reasonable of the Christian communions around which partnership with non-Roman Catholics of France and Italy might be arranged. They disliked clericalism, distrusted Laud, and disdained Presbyterian forms. Hoping to reconcile political as well as religious factions, they remained Royalists though disheartened by the Personal Rule.59 As we know, Hyde and Falkland entered Charles’s service when the Long Parliament was intransigently expropriating his prerogative. They thus were bound in government with at least one Oxford man of “eminent parts and faculties” who shared their worldview: Sir John Bankes.

Great Tew occasionally indulged in fun and science. For fun it had its member John Earle’s bestseller Microcosmographie (1628+) with its weak caricatures of lawyers, doctors, divines, scholars, and antiquaries. Thus, of the young gentleman at the university, “[o]f all things hee endureth not to be mistaken for a Scholler.” Having succeeded in countering this mistake, the young man proceeds to the Inns of Court, “where he studies to forget, what he learned before.”60 Great Tew’s science was more sophisticated. It linked to Oxford through Payne at Christ Church and Gilbert Sheldon, the Warden of All Souls, who had shocked the university as a bachelor of divinity by denying that the pope was anti-Christ. A mind so large also had room for mathematics. So did Hyde’s. His library preserved the manuscripts of Harriot given him by his father-in-law, Sir Thomas Aylesbury, one-time acolyte of the Wizard Earl of Northumberland, and, at the time of our painting, Master of the Mint converting the silver plate of Oxford into coin of the tottering realm. Perhaps more pertinently, Hyde urged “observation and experience,” as exemplified by Bacon, as the way to advance natural knowledge.61 It is said that the men of Tew looked to the laws of mechanics for guidance in their analyses of politics and religion. And, if they also looked into the copy of Galileo’s Dialogue owned by George Morley, a member of their circle and, like his good friend Payne a canon of Christ Church, they would have seen its famous frontispiece in the original version by della Bella.62

Morley’s Galileo is now in Winchester cathedral, whose bishop he became during the Restoration. He succeeded Duppa, translated from Salisbury in 1660, a move that made him Prelate of the Knights of the Garter and the donor of another notable artifact. He gave the Knights’ mother church, St George’s Chapel in Windsor Castle, “the picture of Christ and the Twelve at Supper” recorded as a modern piece in the chapel’s inventory of 1672; a painting of the same subject now hangs in the Parish Church of St John the Baptist in Windsor. The parish advertises it as a national treasure, which it may be, and as a Cleyn, which may be doubted. The inventory also mentions a hanging given by Duppa with “the pictures of Christ and His disciples at Supper;” thus the national treasure may be a copy or model of a Mortlake tapestry, whence the ascription to Cleyn may have arisen.63 A welcome advertisement in any case!

To continue with the fates of Tew’s veterans under Charles II: Earle became Bishop of Salisbury; Sheldon, Archbishop of Canterbury; and Hyde, Lord Clarendon and Lord Chancellor. Falkland did not reach the Restoration. “Melancholy” brought on by the intolerance, rigidity, violence, and inhumanity of the Civil War, or, as Aubrey has it, by the death of his mistress, drove him to court death. During a battle in 1643 he sought a spot where enemy bullets filled the air and galloped straight toward it.64

Starry Messengers

The stars were never far from the battlefield during the first years of the Civil War. Our astrological docent, George Wharton, set up his shop in Oxford after fighting for the king at Edgehill. His learning as a chronologist recommended him to the university’s historians and mathematicians, while his mathematics and predictions made him welcome to the military. In Oxford he worked in the ordnance office under Sir John Heydon, a second-generation astrologer, son of the Elizabethan adept and defender of astrology, Sir Christopher Heydon. Elias Ashmole, another of Sir John’s amateur artillerymen, took up astrology under his influence and reissued an epitome of old Sir Christopher’s unanswerable defense of it previously blocked by “the error or rather malice of the clergy.” John Aubrey, who matriculated in May 1642, likewise fell in with Sir John and became an addict. The examples of Wharton and Heydon were reassuring. Apparently honest practitioners existed among the “divers Illiterate Professors (and Women are of the Number) who even make Astrologie the bawd and Pander to all manner of Iniquity, prostituting chaste Urania to be abus’d by every adulterate Interest.”65

Wharton’s prognostications were more uplifting than correct. For example, he advertised on the shaky basis of the positions of the moon and Mars when Charles marched his army south in May 1645 that the rebellious capital would soon fall. “Believe it (London) thy Miseries approach, they are…not to be diverted unless thou seasonably crave Pardon of God for being Nurse to this present Rebellion, and speedily submit to the Princes Mercy.” The cor Leonis was rising, the sun auspiciously surrounded by Jupiter and Venus and clear of menacing aspects from Saturn and Mars. So what? “These are undeniable Testimonies of the Honour and Safety of the Famous University and City of Oxford.”66 Alas, Wharton had overlooked the approaching conjunction of Saturn and Mars on 12 June 1646, from which some “barking mongrel” (astrologers addressed one another as if they were mathematicians or theologians) had predicted, correctly, that Oxford would soon surrender. Wharton: the barking mongrel had not taken into account the recurrence of that dire conjunction on 28 June 1648, “[which] will be assuredly fatal to London.”67

London’s astrologers knew better. A typical tract warned of “the great eclipse of the sun, or Charles his waine, over-clouded by the evill influences of the Moon [‘the destructive perswasions of his Queen’], malignancie of ill-aspected planets [his ‘Cabinett Counsell’], and the constellation of retrograde and irregular stars ['the Popish faction’].”68 But, although the prognostication was correct, it lacked the persuasive argot of an accomplished practitioner like William Lilly, the first authority in the realm, widely read, generally respected, and too often right. He was self-taught and initially restricted his practice to the usual questions about marriage, health, travel, and business. His first major work, England’s Prophetical Merline (1644), begins with an analysis of the opposition of Jupiter and Saturn on 15 February 1643, which he found, retrospectively, to have announced the troubles of the kingdom. The trouble was evident much earlier to informed people. Ptolemy knew that the effects of major comets could extend for a generation and more; as late as 1644 the comet of 1618, then the last seen in Europe, still afflicted England and most of the Continent. Considering also the badly aspected solar eclipse of 1639 and the bizarre grand conjunction of 1642–3, which “preposterously and irregularly” occurred in the wrong Triplicity, Lilly could only conclude that things would go badly for Charles.69

Several old prophecies also announced the doom of the Stuarts. Here is a clear one, which Lilly learned from a priest in the last years of King James: “Mars, Puer, Alecto, Virgo, Volpes, Leo, Nulus,” which, interpreted, signified Henry VIII (warrior), Edward VI (boy), Mary (fury), Elizabeth (virgin), James (fox), Charles (lion, for ruling without parliament), No One. A similar prophecy, recorded in 1588, ran “When Hempe is sponne, England’s done,” which ditty, unveiled, signifies that after Henry, Edward, Mary and Philip, and Elizabeth, a Scottish king would undo England.70 Right again. But, however persuasive such prophecies, they were only footnotes to messages from the stars.

Lilly deduced his judgments from “pa[s]t and present configurations of the heavenly bodyes, expectant effects of Comets and blazing Starres, influence and operation of greater and lesser Conjunctions of Superior Planets, famous Eclipses both Solar and Lunar, Annual congresses, [and] the remaining effects of prodigious Meteors.” To foretell the fate of rulers, however, he had to inquire into “the removal of the Aphelion of the Superior bodies out of one [trigon] signe into another, by which alone, high and deepe Knowledge is derived to the Sonnes of Art concerning the fate and period of Monarchies and Kingdomes.”71 As for that particular monarchy that reigned in the British Isles, a deeper sign than a passing conjunction declared its doom. As the great astrologer Girolamo Cardano had observed, England fell under the dominion of Mars. It was “a Rebellious and Unluckie Nation,” destined for civil strife.72 Knowing all this, Lilly forecast a parliamentary victory for the very day on which the royal army suffered a crushing defeat in the Battle of Naseby.73 And this in the teeth of Wharton’s prophecy of victory against London!

Professional disagreement and mutual vituperation did not prevent stargazers from gathering in an informal guild. They met annually in a Society of Astrologers for conviviality and mutual encouragement. At its conclave of 1649, it listened to a minister of the Church of England, Robert Gell, confirm that God governs the world through angels and stars. As interpreters of starry messages, astrologers ranked almost with angels; “almost” because sometimes astrologers miss or misinterpret the news. Gell gave a bizarre example. At the time of the nova of 1572, a hill in Herefordshire gamboled over 400 yards before coming to rest. (There was such a landslip at Marcley Hill in February 1571.) Now, when Israel crossed the Red Sea, “[t]he mountains skipped like rams, the hills like young sheep;” the astrologers ought to have coupled the bounding hill with the nova and announced a new age in religion.74 Gell’s clerical colleagues did not think much of his hermeneutics, denounced him for defending conjurors and advocating tolerance, but (such is the power of the stars) failed to turn him out of his rich London parish.75

Lilly and Wharton lived to save one another from peril. With impeccable professional courtesy, Lilly helped extract Wharton from imprisonment by parliament in 1650, which service Wharton, who received knighthood from Charles II, reciprocated in 1660–1. Lilly further demonstrated his professionalism by advising the first Charles confidentially while demonstrating his doom publicly. Lilly recommended days on which Charles should attempt his escapes from Hampton Court in 1647 and the Isle of Wight in 1648. Had Charles heeded Lilly the second time, he might have succeeded.76 Instead he followed his own star, which portended for him personally what, according to King James, Tycho’s nova signified for us all. “By this starre great Tycho did contend ǀ To show that the World was coming to an end.”77

The Portrait

Soon after John Bankes junior had matriculated at Oriel, parliamentary forces under their Captain General, the Earl of Essex, established a forward post in the village of Wheatley, almost within sight of Oxford. Cavalry skirmishing went on for days while the defenders knocked down houses to open a line of fire for their artillery stationed at Magdalen Bridge. Judging that his forces could not take or even blockade fortified Oxford, Essex retreated to a position from which he hoped to intercept the queen’s munitions convoy. Prince Rupert thought the situation ripe for an evening’s entertainment at rebel expense. He sallied forth across Magdalen Bridge at 4:00 p.m. on 17 June, savaged a few rebel outposts before dawn, and drew units of Essex’s army into battle around 9:00 in the morning. After a hard fight in which John Hampden, the veteran of the cold war against ship money, was fatally wounded, Rupert could declare victory and return to Oxford in time for a late lunch. Report of the wounding of his old enemy Hampden struck a chord in Charles’s concert of civility. He sent Hampden a minister and offered to add a doctor; but Hampden had need only of the minister.78

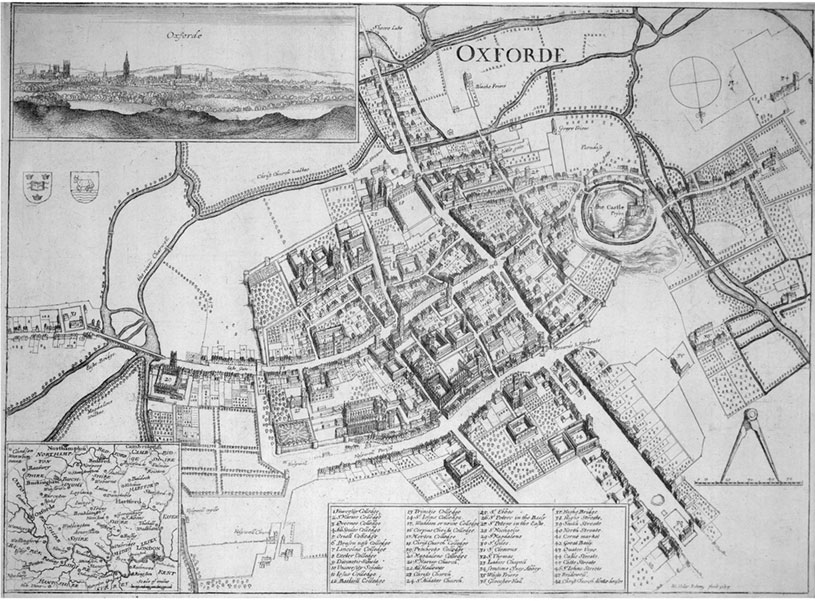

The high probability of dying from disease or wounds suffered in sallies caused cavaliers who wished to leave their likeness to posterity to have their portraits painted. Several accomplished artists set up in Oxford, drawn by business opportunity and the hope, perhaps, of filling the top slot vacated by Van Dyck’s death in 1641. One of these adventurers was Hollar, by then attached to the court as drawing master to the Prince of Wales. Although portraiture was not his line, he drew a few royals, including Henrietta Maria and Prince Rupert, and, what was of greater value, Oxford itself, as it appeared in 1643 (Figure 50). He soon dropped from the competition, however, to go to his patron Arundel, who had not returned from his conveyance of the Queen and Princess Mary to the Continent.79 The legacy of Van Dyck fell to Cleyn’s only known student besides his own children. This anomaly, William Dobson, had worked for an alert lady in Mortlake who noticed that he could draw. She recommended him to Cleyn, who taught him technique enough to enter the king’s household as instructor in painting to the princesses Mary and Anne, and, perhaps, to join in decorating Ham House. From his master, Dobson learned what one authority depreciates as a “ponderous,” another as a “somewhat pedestrian version of the international mannerist style,” which, tradition has it, was improved by some exercise in the studio of Van Dyck.80 Dobson then set up for himself in London, where he made his name as a portraitist with his arresting depiction of Endymion Porter (Figure 51). Late in 1642, while still in his early thirties, he went to Oxford.

Figure 50 Wenceslaus Hollar, Oxforde (c.1643).

Figure 51 William Dobson, Endymion Porter (c.1643).

The evidence of Cleyn’s influence on Dobson lies in symbolic figures and reliefs in some of Dobson’s portraits and especially in an early canvas, The Four Kings of France, a satirical rendition of Charles IX, Henris III and IV, and François II, in which two crowned dogs wearing collars reading “Cathol[ic]” and “Hugu[enot]” fight over the prostrate body of France, the whole contained within a border recalling Cleyn’s tapestries. This complicated conceit arose from the brain of Sir Charles Cotterell, the royal Master of Ceremonies, to illustrate a history of the French civil wars that King Charles, facing one himself, wanted translated. Dobson portrayed Cotterell along with himself and Lanier in a picture said to show the “resoluteness, weariness and stress of a beleaguered existence,” or, perhaps, music, painting, and literature coping with their wartime situations. The painter is the only one courageous or curious or impudent enough to direct his gaze at the viewer.81

Dobson’s first commissions at Oxford included Prince Rupert. Thereafter lesser aristocrats, mainly officers of the king, sought him out. He portrayed them, even the bravest, in appropriate melancholy, apprehensive, anxious, even anguished.82 He tried to place in his portraits symbols indicative of the client, appealing to a taste downplayed during Van Dyck’s dominance, but quite in keeping with Cleyn’s narratives; and, although the press of people demanding his attention caused him to cut corners, he escaped the censure that Norgate directed at Van Dyck for a similar fault. “Vandike…[in Italy] was neat, exact, and curious in all his drawings, but since his coming here, in all his later drawings was never judicious, never exact.” With his quick talent, vigorous poses, and Venetian colors, Dobson became the new star, “the English Tintoret,” in the expert opinion of his sovereign.83 Demand increased. To help meet it Dobson took an assistant and may have called on, or joined forces with, his former instructor Cleyn. He had a studio on the High Street near St Mary’s and, it seems, lodging in St John’s; as a painter patronized by the king, Dobson could find accommodation in crowded Oxford.84

Despite his reputation as a portraitist in Denmark, Cleyn’s work for great people in England had centered on painting their houses rather than their persons. However, an album of his drawings that has recently come to light shows that he continued to sketch portraits. It contains several well-drawn heads, including those of Henrietta Maria and the young woman who became the Hero of his tapestries.85 When he returned to formal portrait painting in Oxford, it was not for long; only two examples, both owned by the National Trust, are known. One is of Williams and Bankes, the other, once attributed to Dobson, is of Sir John Crump Dutton, who had a large estate at Sherborne some 20 miles west of Oxford.

Sir John was a crotchety rich lawyer who had not been keen on the king. He had opposed forced loans, refused ship money, and served in the Long Parliament. Nevertheless, he went, or, as he later asserted, was taken by force, to wartime Oxford, given an honorary degree, and made a colonel in the Royal Army. This commission cost him £5,200 when he later had to compound with parliament for his estates (worth £60,000); he remained nimble enough, however, to ingratiate himself with Cromwell and support the Commonwealth. His portrait, hanging in the lodge he built at Sherborne, is similar in palette to the Kingston-Lacy picture, but without the deep melancholy; it exhibits a confidant, quizzical sitter, knowing his place in the world and not discontent with it (Figure 52).86 Why did Dutton choose Cleyn? Perhaps at Sir John Bankes’s suggestion. The lawyers knew, or knew of, one another. Attorney General Bankes had assisted the House of Lords when it heard a petition against Dutton arising from a family quarrel.87

Figure 52 Francis Cleyn, John Dutton (c.1643).

Cleyn’s painting of young Bankes and Williams has a naturalness that might have recommended it even to Prynne and his fellow pious logicians who reckoned that portraiture belonged to the genre of cosmetics. To them the deceit practiced by women who painted their faces and dyed their hair differed negligibly from the counterfeiting of cavaliers on canvas. Portraiture misleads by the cunning use of light and shadow, foreshortening and perspective; it turns daubs into icons. To ascribe reality to such fakery is to make a meal of a still life. Yes, no doubt, replied such connoisseurs as Norgate and Wotton, cozening is indeed the point of painting: a good picture gives pleasure to the extent that it deceives, its truth being in proportion to its falsity (Norgate); indeed, it is an “Artificial Miracle,” which can work miracles itself by prompting viewers to recognize the truth in caricature (Wotton).88 The picture of Sarpi Wotton distributed might serve as an example; the serene face marred by an assassin’s attempt illustrated both the evils of popery and the fortitude needed to overcome them—a message, if not a medium, entirely acceptable to Prynne’s faction.

Another reason for the pious to distrust pictures was their connection with the stage. Masques, declared Jones, downgrading Jonson, are “nothing else but pictures with light and motion.”89 A tragedy with a strong plot, said Aristotle, is like a well-conceived painting, ut pictura poesis. With deceitful colors applied con amore, portraitists can “catch the lovely graces, witty smilings, & sullen glances which passe sodainly like lightning” across the faces of their sitters and can claim a place on Parnassus alongside epic poets. Like poets, painters must bring out the universal in the individual, which, if successful, must involve some distortion. Prynne was right, a portrait is a selective caricature, and therefore deceitful; but wrong in condemning the result as necessarily untruthful. Skillful portraitists reveal character economically, indeed, with the discipline of the most spare and retrograde Puritan. For good painters, again like poets (and also politicians), should not complicate their counterfeits with gimmicks; the multiplication of novelties in portraiture, as of neologisms in literature, shows not power to improve, but inability to master, an art.90

Cleyn’s portraits observe this sophisticated naturalism. Williams is convincing as a healthy sober man of middle age, perceptive, reliable, and sympathetically attentive to young John, whom he is trying to interest in the wider world represented by the carefully chosen items on the table. John is depicted more subtly. No doubt he is a perfect rendition of a listless adolescent, apparently indifferent to his studies and more interested in striking a fashionable melancholic pose with his splendid dark clothes and the awkward, if not impossible, posture of his left hand, a device Cleyn may have taken from Isaacsz or Van Dyck (see Figure 1).91 But the boy’s melancholy may also be of the genuine intellectual kind, as indicated by the approach of his right hand toward the table, his outsized head, and averted gaze. Is he suffering from the effort of thought? Is he sick, proud, miserable?

Williams may be recognized as a physician by his jewelry, if, as appears, his ring is of topaz, a gemstone reputed for its curative properties, and his ruff tie is of turquoise, known to promote healing. The objects on the table of cosmology are perhaps not entirely what they seem. The item that might be taken for a rolled-up nautical chart is a telescope with drawtubes. Surviving examples usually have a tooled leather covering or other decoration of the main body of the instrument; Cleyn’s version without decoration, perhaps a German or English model, improves the confusion of nautical chart and perspective glass.92 It does not resemble the conventional representation in his series on the Five Senses or the Seven Liberal Arts. The telescope in the liberal art “Astronomy” (see Figure 48) resembles the flute in “Music,” both being slender cylindrical wands; that in “Sight” (see Figure 41), aimed by a putto at grotesque work, is slightly more realistic; but, in contrast to the model in our picture, both belong to Cleyn’s world of make-believe. As we know, the telescope, alias perspective, prospective, or Galilean glass, had many meanings; and, although here its fundamental note might be a metaphor for travel or instrument of investigation, its overtones—clarity of vision, perception of truth, guide to life—would have been heard by educated viewers of Cleyn’s picture.

The telescope and its companions, the globe and books, do not have the sort of claim to reality as do the items carefully rendered in The Linder Gallery and many other contemporary depictions of studios and Kunstkammern.93 In contrast, the vagueness of the props in Cleyn’s double portrait enhances the real-life story of Williams and Bankes. The telescope can be mistaken for a rolled-up chart; the compass, though rendered delicately, may be for measuring or drawing; the books have no titles; and the globe has no features definite enough to fix a destination, although the portion of the globe facing the viewer suggests the North Atlantic as depicted in English maps of the 1630s.94 Sir John Bankes was familiar with this geography, from charters and grants he had drawn up when Attorney General, and so perhaps was Cleyn, from his association with the former Virginia Company’s former treasurer Sandys. If the landmass facing the viewer is North America, the brass pointer at the globe’s pole would indicate Europe as the likely destination of young Bankes’s travels.

A famous painting by Van Dyck of Lord and Lady Arundel sitting by a large globe (Figure 53) suggests another possibility. Arundel is pointing toward the island of Madagascar, whose colonization the Arundels were promoting. Endymion Porter had urged Charles to send an expedition to this tropical paradise under the direction of Prince Rupert (then, in 1637, only 17) to remove the French and Portuguese, and in 1639 the Arundels, as usual needing ready money and worried about possible enforcement of the recusancy laws against them, obtained royal approval to make the attempt. The earl contemplated going himself. So did Davenant: “I wish’d my Soule had brought my body here ǀ Not as a poet, but as a Pioneer.” In Davenant’s poem, the pioneers led by “the first true Monarch of the Golden Isle”—that is, Prince Rupert—destroy an unidentified enemy to open Madagascar to the English.95

Figure 53 Antony Van Dyck, Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel, and his Wife Lady Alethea Talbot. The couple are caught considering a trip to Madagascar (c.1649).

That was poetry. In prose nothing happened until 1643, when a disaffected former employee of the East India Company, a surgeon named Walter Hamond who had visited Madagascar in 1630, advertised that the island groaned with gold and gems and boasted a soil so fruitful and water so plentiful that the “sluggish and slothful” natives lived off them without planting or sowing. Among their other merits was ignorance of navigation, which had almost ruined England with drunkenness from Germany, fashion from France, insolence from Spain, Machiavellianism from Italy, and pox from America. Hamond’s short account ends with the allurement that its women went naked, which at first “made our eyes unchast.” After a week the gallants could gaze where they pleased without quickening their pulse, “as we behold ordinarily our Cattell,” and had discovered that “the dresse of women, allures more than their nakednesse.” Inspired into rare agreement, parliament and king both authorized an expedition, which sailed, with 145 people, early in 1643. The adventure proved a disaster, as anyone who had read Heylyn’s Mikrokosmos would have foretold. “The people are treacherous and inhospitable,” he had written, ignorant, without religion or a calendar, “onely laudable…[in] restraining themselves to one wife.”96 The British expedition came to grief owing to fever, hunger, malaria, and the natives’ “barbarous shriekings, which they term singing.”97 News of the disaster would have scuttled any plan Sir John might have had to enroll his son in Arundel’s project to colonize Madagascar.

The compass John Bankes holds so listlessly, as if reluctant to measure the distance to Madagascar or Newfoundland or somewhere else he did not want to go, seems to be a pair of single-handed dividers convertible into a drawing compass. Although the basic design goes back to the sixteenth century if not earlier, no exemplar has come to light.98 Presumably Bankes would use it in his studies, if he devoted his Saturnine energy to them. Mindful of Wotton’s observation, “[e]very Nature is not a fit stock to graft a Scholar on,” we should think that Williams wanted not to make a mathematician or an astronomer of young Bankes, but only to have him learn cosmography to the extent Peacham and Fuller recommended for a gentleman of average capacity.99 If, however, the imperturbable boy was a true melancholic intellectual, he had easy access to a complete education in the mathematical sciences. John Greaves lived at Merton across the street from Bankes’s rooms at Oriel.100 Since Greaves had every reason to serve Sir John Bankes, to whom, as an elector, he owed his chair, we might reasonably conjecture that he did instruct young Bankes, and that the telescope, globe, and the Galilean book in Cleyn’s painting came from the cabinet of the Savilian professors. It had everything needed: Savile’s library, globes and telescopes, and a copy of the Latin translation of the Dialogue, the Systema cosmicum, in the first edition of 1635.101

Several colleges also had copies of the Dialogue. Payne gave his to Christ’s Church in 1642. The Bodleian has copies associated with Savile and Selden. Those now at Queen’s and St John’s, acquired in the 1650s, might have belonged to members there in the 1640s. Balliol, Greaves’s college, has a copy of the Dialogo of 1632 bound together, most appropriately, with Sarpi’s posthumous Historia della Sacra Inquisitione.102 Another would have been present if anyone at Oxford bought the copy or copies offered for sale in London in 1639.103 A reprinting of the Systema in Leyden in 1641 brought more copies, five of which would now be on deposit if one had not been stolen from Christ’s Church in the 1990s. The publisher of the reprint of 1641 misstated its content and purpose in a blurb that deserves preservation as unusually nonsensical: by returning the sun to its rightful place, Galileo’s Systema defeated the ancients and suppressed quarrels among astronomers.104 The only unidentified item among the props is the heavy book holding the Dialogue open. A guess at its identity will be made in due course.

Having the props and the people, Sir John had only to procure a painter. He could not commission his own portraitist, Gilbert Jackson, who had died soon after finishing his lifeless image of the Chief Justice.105 Perhaps Sir John invited Cleyn, whose work at Mortlake he knew, to work in Oxford; perhaps he found him there, in Dobson’s studio. Cleyn was ready for the work and eager to give of his best. His income had plummeted with the idling of the tapestry works and he still had children to educate. Three wanted to become artists. They were to make modest reputations, the girl, Penelope, as a miniaturist and the boys, Francis and John, as draftsmen. Evelyn saw pen drawings the sons made after the famous Raphael cartoons copied by their father, “where, in fraternal emulation, they have done such work, as was never yet exceeded by mortal man, either of the former, or the present age.”106 Nothing securely attributable to either of the sons seems to have survived.

Cleyn drew young Bankes seated on the chair on which Dutton had sat, the same sort of chair that Rubens and Van Dyck had used for some of their portraits.107 The posture thus imposed challenged the painter’s ability to depict the character of a melancholy sitter in the manner prescribed by Italian authorities. According to Alberti, “a sad person stands with his forces and feelings as if dulled, holding himself feebly and tiredly on his pallid and poorly sustained members.” Lomazzo arrives at the same place (a melancholic should be rendered as pensive, sorrowful, and heavy) after reviewing eleven delineable passions of the mind and bodily expressions of humoral imbalances. But Lomazzo concedes that slavish adherence to these rules does not produce a great work of art; which “cannot be attained unto, by the mere practice of painting, but by the earnest studie of Philosophie.”108 Lomazzo was an authority worthy of attention, another Aristotle in the opinion of his English translator, for the depth and extent of his “most absolute body of the [rules of the] Arte.”109 Cleyn knew the rules. It was by combining them with an “earnest studie of Philosophie” that he was able to portray a heavy melancholic young man, “holding himself feebly and tiredly” in a chair.

Not only must a theorist be tinctured with philosophy to make an excellent picture, but its viewers, like the painter, must also be “filled with a great variety of learning.” This was the opinion of Arundel’s librarian Junius, who continues, “without this purifying of our wit, enriching of our memory, enabling of our judgment, inlaying of our conceit,” we will never be able to get beyond evaluation of coloring and draftsmanship. An amateur properly prepared can judge a painting as accurately as its creator.110 Wotton had considered the matter. “An excellent Piece of Painting,” he said, becomes “an Artificiall Miracle” when viewed “philosophically.”111 Viewing is hard work. “The Expressions are the Touchstone of the Painters Understanding…But there is much Sense requir’d in the Spectator to perceive, as in the Painter to perform them.”112 Would not a philosophical critic have thought Cleyn’s rendition of tutor and pupil, with its economical evocation of their mood and bond, superior to Jan Lievens’s sumptuous presentation of King Charles’s nephew, Charles Louis, and his tutor (Figure 54)? Submerged under his elaborate drapery and placed before the huge book he is supposed to be studying, Charles Louis looks appropriately despondent, and there is no rapport between him and his tutor, whom we may suppose the chief cause of his discomfort.113 Someone in Rembrandt’s studio handled the same subject more gently in a portrait, perhaps of Charles Louis’s brother Rupert: the tutor is not so overbearing, the book is smaller, and the boy regards it intelligently. In neither case is the book identifiable (Figure 55).114

Figure 54 Jan Lievens, Prince Charles Louis and his Tutor (1631).

Figure 55 Gerrit Dou?, Prince Rupert? and his Tutor (c.1630).

Viewers of Cleyn’s mysterious masterpiece did not need to know much about the sitters, or even recognize them, to philosophize about the painting. The power of a portrait is not in the identity of the sitter, who, if not uncommonly famous or infamous, is soon forgotten. The poet Abraham Cowley, who was in Oxford about the time Cleyn painted our picture, noticed the frenzied portrait painting of cavaliers and the fleeting interest in their identity. “The man who did this picture draw ǀ Will swear next day my face he never saw.”115 Put in a little puzzle like a reference to Galileo, however, and your portrait of an unknown boy might live for hundreds of years.