9

The Image

The society in which the Bankes family lived and worked was constantly exposed to old star lore and new astronomy through almanacs, plays, literature, handbooks, and political and religious discourse. The better instructed must have known enough to recognize the allusion to Galileo in Cleyn’s painting. What did it mean to them? Galileo’s way of exploring answers to difficult questions, by way of dialogue among quasi-fictitious characters, suggests a route to an answer. We shall have a dialogue. As in Galileo’s, the characters will take positions they would have assumed in life: Dr Williams (MW) resembles the omniscient Salviati and John Bankes (JB) the sharp-witted, commonsensical Sagredo. Francis Cleyn (FC), like Simplicio, is a gentle, composite figure, but of master artists, not of slavish philosophers. There is a fourth interlocutor, offstage but never far away, whose ideas direct most of the conversation: Galileo himself in his Dialogue, Sir John Bankes in ours. Also, as in a Galilean dialogue, we must have digressions.

The conversation takes place in Gray’s Inn, in the rooms of John’s brother Ralph, who is studying law. Cleyn’s painting has probably hung there since its completion a decade earlier. The Bankes family had chambers even after Sir John’s death; he had enrolled his eldest sons in Gray’s Inn during their childhood to encourage them to study law after terms at Oxford or Cambridge.1 At the time of our dialogue, John is a confident, wealthy young man, transformed by travel from the feckless youth we knew. He had gone to France in 1645, improved his knowledge of French in Paris, and soon set off for Italy. On his way he fell in with a Dutch jurist who stretched his mind with the grotesque claim that the university of Leyden, with its Scaliger, Grotius, and infamous Arminius, was more distinguished than the much older Oxford of Bainbridge and Greaves.2

Threading his way between the two Italys of the guidebooks, between “the Nurse of Policy, Learning, Musique, Architecture, and Limning” and the gymnasium of vice, epicurizing, whoring, poisoning, sodomizing, and atheism, further broadened him. If he acted on his guidebook’s report that a traveler is “accounted little lesse than a foole, who is not melancholy once a day,” he might have passed for an intellectual.3 In any case, he took on enough of the continental to practice the bad habit, censured by the guidebooks, of acting the foreigner on his return. Or so we infer from a note that “Giovanni Bankes” addressed to his acquaintance from Oxford days, Justinian Isham, “tra i boschi ameni a campo Elisée di Richemont.”4

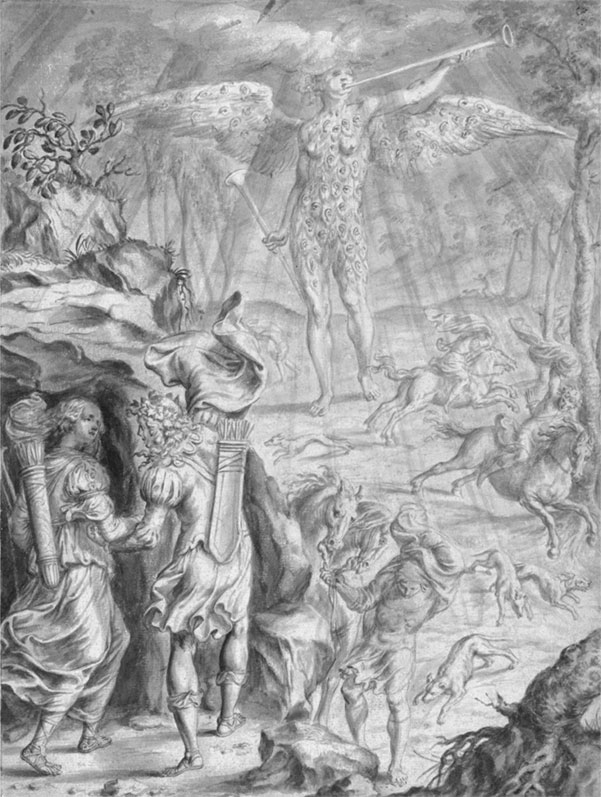

Cleyn had substituted graphic for tapestry design as his main work after completing our painting. He moved to London, to the parish of Covent Garden, where he remains, buried in Inigo Jones’s oddly oriented church. He stayed busy making hundreds of drawings for coffee-table books for Ogilby, the limping dancing master who translated Aesop and Virgil into limp verse. A few of the drawings from which the engravers worked survive. An exemplary one shows poor doomed infatuated Dido leading Aeneas to their cave to escape the downpour that interrupts their hunt, while in the background the monster Rumor, covered in mouths and ears, her head in the clouds, wings open, stands ready to spread the lovers’ doings far and wide (Figure 56).

Figure 56 Francis Cleyn, Dido, Aeneas, and Rumor (c.1654).

The Mortlake works had scraped by with a few commissions for old sets until Cromwell took an interest in tapestries and Cleyn could return to making cartoons. The themes appointed, the Story of Abraham and the Triumphs of Caesar, suited the Protector’s mix of religion and militarism.5 By a rare agreement between king and parliament, Cleyn kept tools and designs from Mortlake in his London studio, where they joined paintings by Titian, Tintoretto, and Van Dyck. There were excellent copies of other masterworks, including the Raphael cartoons, all done by Cleyn’s two sons.6 To his great sorrow and the world’s loss, both died young, leaving, as his last artistic offspring, his daughter Penelope, who gained some reputation as a miniaturist.7 Cleyn gave some of his select collection, regrettably identified only as “draughts and pieces of paintings of sundry excellent masters,” to John Tradescant for preservation, along with gifts from King Charles, the Duke of Buckingham, Laud, Wotton, Digby, and the Countess of Arundel, in his famous Ark.8

The third of our interlocutors, Maurice Williams, had risen in the medical world since leaving Oxford. In 1651, he became an “elect,” or senior member, of the College of Physicians. He had made his peace with parliament, which sent him and two other physicians to Ireland in 1652 on urgent unspecified business. He had property there to dispose of, evidently not extensive, for which he compounded with parliament for £20. If he paid this ransom at the same rate as the Bankeses, the property would have been worth £400 to £500. So far the historical record extends.

At John Bankes’s request, Williams arrived at Gray’s Inn before Cleyn for a consultation about some medical advice John had received when taking the waters at Bath.9 Their exchanges showed something of the doctor’s erudition, discernment, and humor. The advice in question had to do with the difficult question, still with us, of what and how much to drink in England. Could one domesticate the behavior described in the adage Bankes had recorded in his travel diary, perhaps enviously, Qui bue si garde sobre se rend italien, “if you can drink and stay sober you make yourself an Italian”? His doctor in Bath, Tobias Venner, had reassured him: do not drink water unless your stomach is preternaturally hot and dry. Drink beer or, better, wine, as it strengthens natural heat, helps digestion, combats flatulence, and “taketh away the sadnesse, and other hurts of melancholy.” Of course, Dr Venner advised, no one should drink immoderately except kings and great officers of state. Children under 14, youths under 25, and men under 35 should be abstemious, temperate, and careful, respectively; but over 35 you can drink wine as you please, for “it mightily strengtheneth all the powers and faculties of the body,” especially in people in the later period of old age—that is, over 60.10 A wise physician! There remained the question whether wine should be consumed hot, cold, or tepid.

JB. As you know, Sir Maurice, I suffer from a melancholy stomach and learned from Venner that cold was bad for it. He says that the omniscient Lord Chancellor Bacon recommended that we should warm our stomachs with a hot drink before dining even in midsummer. Bacon proved the danger of excessive cold very dramatically if it is true that he died at Lord Arundel’s house after trying to stuff a chicken with snow.11

MW. Bacon did not die from stuffing snow into a chicken but from swallowing medicines he prescribed for himself.12 Incidentally, the custom of drinking wine before the meal is at least as old as Tiberius. As for cold drinks, unnaturally cooled by snow or ice, they are a damaging luxury. But I’ve seen Florentines put ice in wine and the Sienese keep wine jars in cold water, on the advice of no less a man than Girolamo Mercurio, who doctored Galileo.13 Mixing wine with cold water, however, can produce excellent results. When the Nymphs washed Bacchus they used cold water. Symbolic, no doubt. Plutarch advises watering wine by harmonic proportions: 3 parts water to 2 of wine (a fifth, musically speaking) for the merriest; the octave (2:1) for the staid; and the product of the two (3:1) for the abstemious. Here is another curiosity from Plutarch for you. After the ancients forbade women to drink wine they invented kissing to discover infractions.14

JB. Venner says that a ratio of 2 or even 3 parts of water to 1 of wine is suitable for southerners, but 1 to 1 is the recipe for England, and 0 to 1 for men of your age. He says nothing about kissing but urges frequent cleaning of the teeth and avoidance of radishes, which might be intended as a preparation for it.15

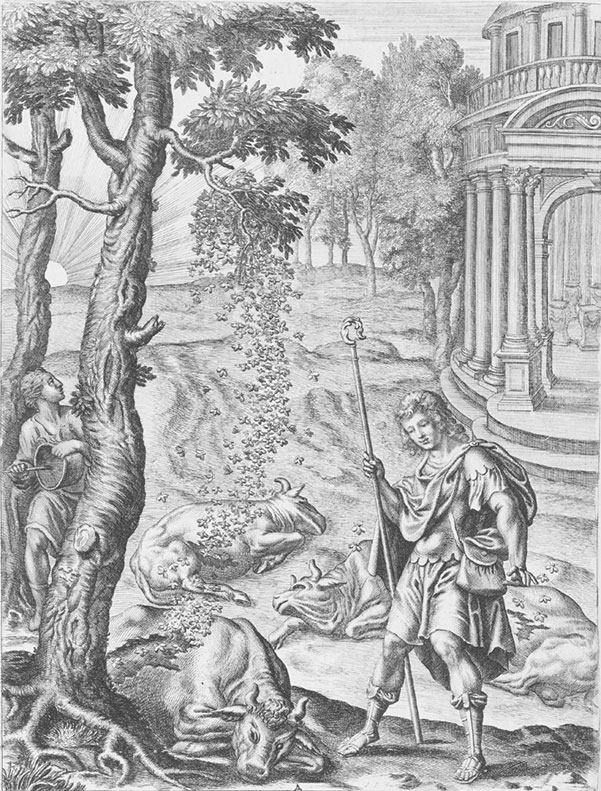

MW. Excellent advice, all of it, but enough of it. Let’s prepare for our talk by looking over Cleyn’s illustrations for Sandys’s Ovid. They are very clever, attractive in themselves and a great temptation to play at sortes virgilianae. We need only open the book at random. Well, well, here is an augury, Cleyn’s depiction of bugonia, that queer old practice of growing bees from the carcasses of slaughtered cattle (Figure 57). Bees! No doubt we shall have sweet conversation as we buzz about our portrait. There is Aristaeus, who invented or perfected the practice; Cleyn has him appear a little perplexed by his success.16 It reminds me of the conclave that elected Urban VIII when I was in Italy. Barberini and his bees emerged from it over the bodies of several cardinals who died of heat or old age during their long burial in the Vatican. Ah, here is Mr Cleyn.

Figure 57 Francis Cleyn, Bugonia, from Virgil’s Georgics, book IV, in John Olgilby, Virgil (1654).

FC. I apologize, gentlemen, for my tardiness. The fields are wet and though I picked my way carefully I got moist in the nth degree, as old John Dee might have said. He made algibberish out of everything.17 It is a beautiful place, Gray’s Inn, but a little isolated. Yes, thank you, a cup of sherris-sack, just the thing for a cold stomach.

JB. Well, here is the painting. What do you think of it?

FC. It needs cleaning. The London smoke ruins everything even in these outskirts. But I’m glad to see that the Galileo emblem still stands out clearly.

JB. That comes to the heart of the question quickly enough. How did you think to put it there?

Gaps

FC. It wasn’t my idea. Dr Greaves brought it to me. He said that I should take care to put it in the painting, but not paint in it, which I suppose was a mathematician’s joke. I knew the book. I had looked at a copy here in London quite carefully, to study the design of its frontispiece, an art in which I can claim a professional interest. It is one of the most brilliant frontispieces I know, maybe the most brilliant. Just the spacing of the figures is stupendous! It is so singular, it is instantly recognizable—only by people who know the book, of course. The brilliance is, I say, in the spacing: the figures evidently are engaged in friendly conversation, but one of them just as clearly opposes the other two and is somehow the strongest. And that is shown just by the spacing and the attitudes. Brilliant! And to think that della Bella was only 20 when he conceived it.

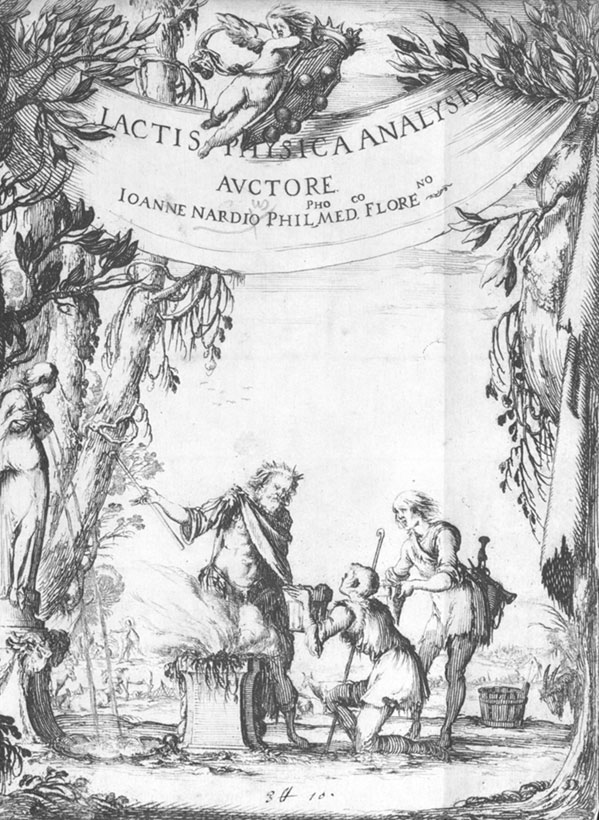

MW. It is a very clever design. He did something similar for a book in my field by the chief physician to the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Giovanni Nardi. Della Bella needed tact as well as talent to do both jobs at the same time. Nardi rated his fellow courtier Galileo an arrogant thieving novelty hunter for pinching the idea of the telescope from della Porta and the idiocy of a moving earth from Pythagoras. Della Bella’s frontispiece to Nardi’s book, which is about milk, plays with three figures separated two to one as in the Dialogue (Figure 58): two sick rustics offer Aesculapius what seems to be wine and burnt offerings to effect a cure; he points to a statue of a woman from whose breasts milk is pouring into a pool. Milk not wine is nature’s food.18

Figure 58 Stefano della Bella, frontispiece to Giovanni Nardi, Lacta physica analysis (1634).

FC. Both drawings use the convention of a stage or portal where allegorical figures advertise the nature of the entertainment or instruction discoverable within.19 For the Dialogue, della Bella turned the stage into a strand on which his three figures talk under a curtain carrying the title and raised to reveal a harbor (see Figure 3).

MW. And on the strand, for the cognoscenti, are strewn some arrows and cannon balls from Galileo’s experiments.

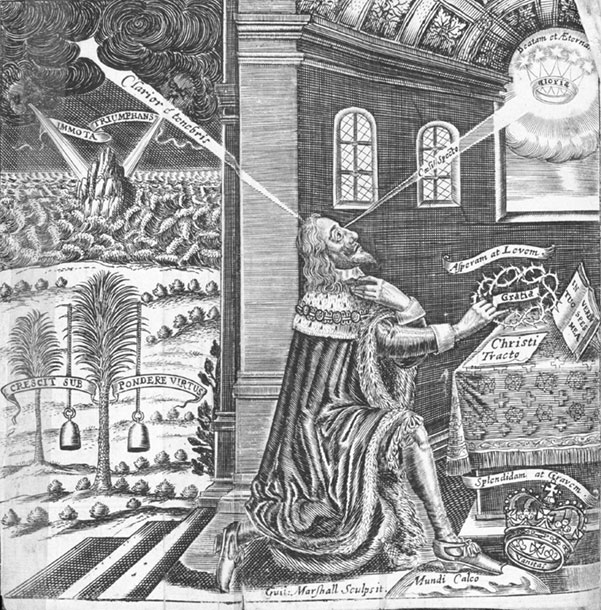

FC. I should correct myself: the figures do not talk. Their stance conveys their meaning. Compare Marshall’s frontispiece to Wilkins’ book, where each person says something about his position (see Figure 25); in my opinion, a picture should tell its own story without reliance on written clues. In Marshall’s frontispiece to our late king’s ghostly testament, Eikon basilike (1649) (Figure 59), the suffering sovereign talks to himself. “Caeli specto beatam et aeternam,” “Mundi calco splendidam et gravem,” “Christi tracto asperam et levem.” Even a rock speaks (“immota triumphans”) and also a tree (“crescit sub pondere virtus”)!20 And the frontispiece he did for Mr Quarles’s Fons lachrymarum! Five people talking! I remember a badly drawn King Charles bending over a woman and saying something like, “look at the face, behold mine.”21 Really!

Figure 59 William Marshall, frontispiece to Eikon basilike (1649).

JB. But perhaps you carried your principle too far, Mr Cleyn, in omitting the author and title of Galileo’s book from the impression of it in our painting.

FC. But does that not make the question why that particular book, once identified, is there, all the more worthy of investigation? Only people who had seen it before and knew the circumstances of your family, Mr Bankes, could interpret it.

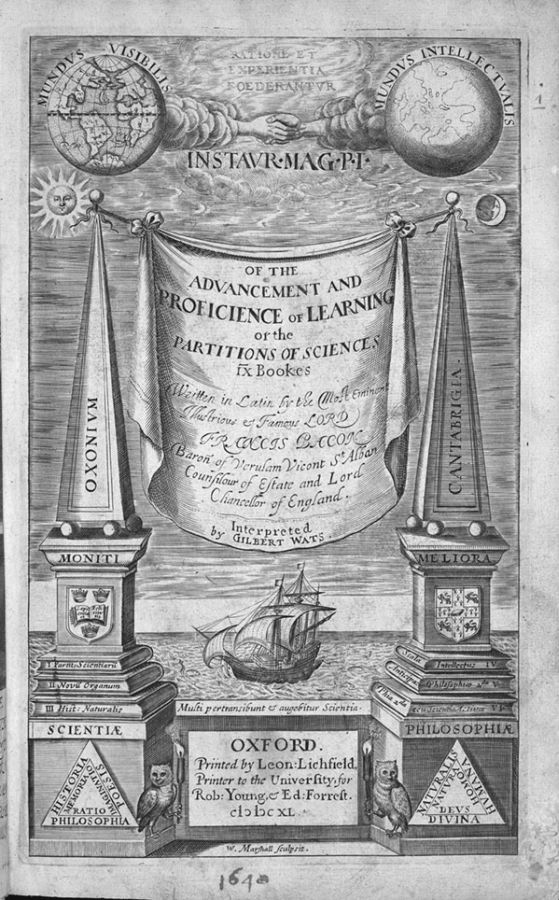

MW. We shall go there in just a minute Mr Cleyn. First I want to say a good word for Marshall’s art. He can be quite witty. I’ll give you two examples. One is his adaptation of the title page of a favorite book of mine, Bacon’s Novum organum, to suit a recent edition of the Advancement of Learning. The original presents the Pillars of Hercules as the gateway to discovery, or the proscenium to the theater of the new world, under a slogan taken from the prophet Daniel, Multi pertransibunt et augebitur scientia, “many will pass through and knowledge will be increased.”22 In Marshall’s version, the pillars consist of columns of books surmounted by obelisks, one reading “Oxonium,” the other, “Cantabridgia” (Figure 60). Oxford’s obelisk stands on Bacon’s most important works and a pedestal marked “Science” advertising tough subjects such as history, philosophy, and poetry, all acquired by reason; Cambridge’s obelisk stands on Bacon’s slighter works and its pedestal, marked Philosophy, advertises its humanizing, natural, and divine divisions, acquired with the help of God. A terrestrial globe (the visible world) and the sun shine over practical Oxford, an empty sphere (the intellectual world) and a moon dominate lunatic Cambridge; and two owls holding torches illuminate the name of the printer and his employer, the University of Oxford.23

Figure 60 William Marshall, frontispiece to Francis Bacon, Advancement of Science (1640).

FC. I admit, there is something clever in that.

MW. The second piece I have in mind is the befuddling frontispiece to George Wither’s Collection of Emblems. Although he had no idea what most of them meant, that did not stop him, or anyone else, “Who many times, before this Taske is ended ǀ Must pick out Moralls, where none was intended.”24 Let us keep this salutary warning in mind!

JB. I suppose that Galileo must have had a hand in della Bella’s drawing for the Dialogue.

FC. He had some training at the famous art school in Florence, the Accademia del Disegno. And you can see in the extraordinary drawings of the surface of the moon in Sidereus nuncius that he knew about foreshortening and other tricks of the trade.

MW. Also, it is hard to credit that the young della Bella knew enough about Galileo’s work to put in the arrows and weights on the ground or the reference to the ships and the wharf.

FC. No doubt, Sir Maurice, but I feel confident that the soul of the drawing came from della Bella. As an artist he was well acquainted with what I call the three-body problem: how to represent a triplet of people of unequal rank on the same canvas, say two saints and the Virgin or two laymen and a saint. There are very pertinent examples in Venetian painting that Galileo might have seen during the many years he spent in Padua. They are by a very famous trio of artists (there is not much space between them!) who sometimes worked together, Giorgione, Titian, and Sebastiano del Piombo.25

MW. What were the trio’s solutions to the three-body problem?

FC. From Titian I have in mind a painting you probably know. Van Dyck made a copy of it in Venice and later it hung in the king’s gallery. It celebrates a victory over the Turks by a Venetian fleet led by a bishop, Jacopo Pesaro, who was put in charge by Pope Alexander VI. The picture shows the pope presenting the kneeling bishop to St Peter seated on a throne. Between the saint and the prelates is an eloquent space expressing the difference in merit between them. Titian uses this space to depict a part of the fleet on its way to engage the Turks.

MW. The gap of merit is well observed, Mr Cleyn. Now that you have me thinking in gaps, am I not right in recalling that you put two of them in your tapestry The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, between Christ and Peter and between Peter and the other apostles (see Figure 39)?

FC. Well observed, Sir Maurice! The gap of merit in the painting by Sebastiano I am thinking of is a window through which the viewer sees a distant landscape. St Catherine and St John the Baptist make a group on one side of the window, the Virgin holding the child a single figure on the other. The third picture, by Giorgione and Sebastiano, offers an interesting variation. It depicts three philosophers. Since they enjoy the same level of being, no gaps occur between them; instead, the artists have individuated them by props and attitudes. One, a youth holding a T-square and drawing compasses, sits with his back to the other two, a tall man in oriental garb and an old man holding a paper covered with strange figures. What it all signifies no one knows for sure; for me it is enough to know it has no gaps of merit.

MW. There are dozens of interpretations each more fanciful than the next: the Magi; Aristotle, Averroes, and Virgil; Archimedes, Ptolemy, and Pythagoras; Aristotle, Averroes, and Regiomontanus; Moses, Averroes, and a Christian; Plato, Aristotle, and Alexander the Great.26

JB. Too bad that chronology rules out Galileo’s trio Aristotle, Ptolemy, and Copernicus. If I understand you correctly, Mr Cleyn, the separation between Aristotle and Ptolemy, taken together, and Copernicus taken alone in della Bella’s description is to be read as a gap of merit.

FC. That’s it, and that is not all. Della Bella drew Copernicus as an old man resembling Galileo: the gap thus separates ordinary mortals from the sublime mathematician–philosopher of the Grand Duke of Tuscany. The editors of the Latin edition missed this subtlety and had the frontispiece redrawn, using the standard representation of Copernicus as a clean-shaven young man. The redrawing of the frontispiece by van der Heyden, which is based on Copernicus’s self-portrait, thus destroys what was almost certainly the original intent, to show Galileo with a gap of merit.

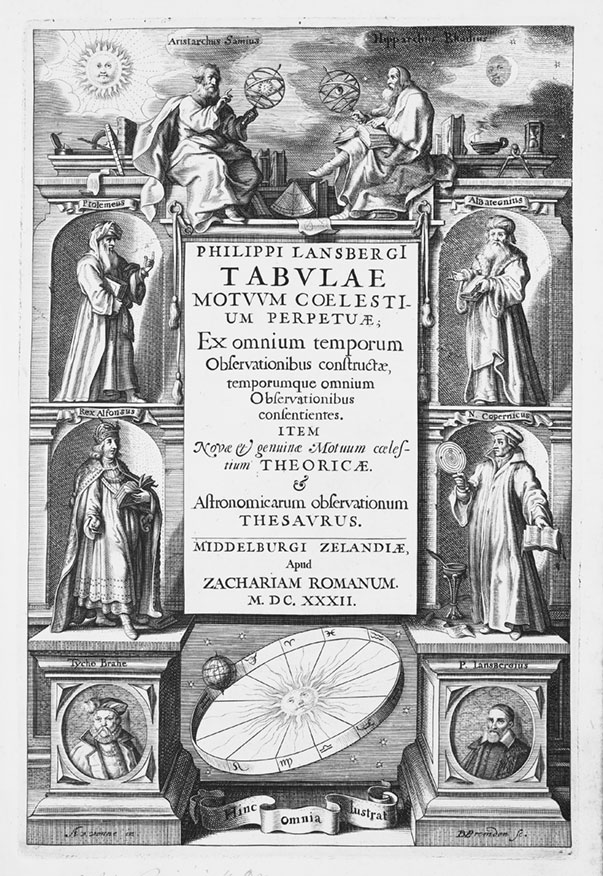

JB. What you say, Mr Cleyn, fits well with the habit of astronomers of depicting themselves on their frontispieces as the latest adept of their science. So, if I remember correctly, Philipp Lansbergen places himself in his Tables of Celestial Motions after Aristarchus, Hipparchus, Ptolemy, Albetagnius, and Tycho. To make clear that Lansbergen stands for Copernicus, he put in a sun-centered zodiac between his effigy and Tycho’s around which the earth revolves as if it were a roulette ball (Figure 61).27

Figure 61 Frontispiece to Philipp Lansbergen, Tabulae motuum coelestium (1632).

FC. Since I’ve gone this far, I’ll confide another of my reasons for considering della Bella’s rendition a play on threesomes. When I was in Denmark I worked on a program of the seven ages of man developed by Tycho’s disciple Longomontanus. From him I learned that no respectable astronomer believed in the old earth-centered system anymore, but that many accepted Tycho’s system rather than Copernicus’. Where is Tycho in Galileo’s Dialogue? Certainly not in the frontispiece, where he would have made up an awkward quartet both symbolically and graphically. The frontispiece puts a gap of merit between the ancients and Copernicus by omitting the major modern challenger to the world system Galileo championed.

JB. I recall that in Kepler’s allegory of the history of astronomy, contained in his wonderful frontispiece to the tables he calculated using Tycho’s data, there are no gaps of merit, just equal spaces, between the representations of the major contributors to astronomical knowledge including Tycho (see Figure 23). Of course, and rightly, Kepler put himself in the series [seated, in the left-hand panel of the base of the gazebo]. Galileo did indeed load the dice in omitting Tycho from the inventors of world systems. But to return to our main question, which is not a gap in merit but in knowledge, who asked Greaves to bring Galileo’s book for inclusion in our painting?

MW. Greaves cannot tell us since he died last year here in London. The parliamentary visitors to Oxford headed by that hothead Nathaniel Brent had ejected him from his professorship. That was not fair, but Brent was strong against monarchy. I think his sympathy with the Republic of Venice and his intimate familiarity with Sarpi’s Trent, which, as you may know, he translated into English, colored his mind. I was called in when Greaves took ill. He was incurably melancholic over his forced separation from Oxford. His appointment as Savilian Professor was the fulfillment of his dreams. He was just 50. But I can answer your question, John. I asked Greaves for the book after a conversation with your father, who wanted a symbol personal to you and, by an appropriate reference to the troubles of the time, also to him.

JB. So the question becomes why he decided to refer to Galileo. No doubt he had several reasons. He seldom did anything if he could think of only one reason in its favor. He was a great lawyer.

MW. One reason is obvious. Since you and I were then studying astronomy and reading the Sidereus nuncius, a reference to Galileo in a picture painted on your leaving the university would have commemorated your studies and interests. That would have been an ordinary gesture.

JB. And it would also have commemorated Galileo, who died the year before I went up. Father would have had that in mind too. He admired Galileo for several reasons. He knew a lot about mechanical devices from his upbringing in Cumberland and from evaluating proposals for monopolies when he was Attorney General. He could appreciate Galileo’s work in transforming the Dutch spyglass into a practical instrument for military and commercial purposes. And for searching the heavens. Father took an interest in astronomy, not least because it supplied nice images for his legal arguments; he invented a complicated one when defending ship money that may have helped him win his case. He understood that Galileo had discovered something new about the size and complexity of the world and respected him for his courage in proclaiming it.

MW. What then did Sir John make of Pope Urban’s condemnation of Galileo?

JB. It gave him a problem. As a law-and-order judge, Father did not criticize Urban for disciplining Galileo in so far as he had violated an edict or injunction properly drawn up and served: but as a fair-minded man, he could not excuse Urban for exacting an unusual penalty, keeping Galileo under house arrest for so many years and then harrowing him beyond the grave.

FC. Do popes claim jurisdiction in the afterlife? No wonder our recusants are so intractable!

JB. No, I meant that Urban refused to allow the Florentines to give Galileo a suitable monument, or even a decent burial, because he had been “vehemently suspected of heresy.” He deserves a monument as great as Michelangelo’s, or perhaps he should share it if it is true that he inherited Michelangelo’s soul.

MW. Urban had exercised a similar after-death authority over Sarpi. The Venetian Senate wanted to raise a monument to him. Urban told their ambassador that it would be inappropriate to honor a man excommunicated by a pope. The senate did not think the matter important enough to go to battle with Rome and acquiesced, no doubt expecting to put up a proper statue one day. Anyway, Galileo and Sarpi created their own monuments. Sarpi’s Trent, which Sir Henry Wotton rated the best book on the subject ever written in Italian, ranks with Galileo’s Dialogue, which has a fair claim to being the greatest literary product of the Italian Renaissance.28

JB. I know Sarpi’s book, not as Italian literature but as English propaganda. Father bought a copy of the 1640 edition of Brent’s translation. I cannot say that I have read it, but he did, all the way through. He liked to read the wittiest attacks on the papal establishment aloud, so I absorbed some of it. Curious that Urban reunited Galileo and Sarpi in that great gap in afterlife, Limbo!

[Not until 1892 did the Venetian government think it expedient to raise a monument to Sarpi against continuing objections from Rome. Like the monument to Bruno, erected in the Campo de’ Fiori in Rome in 1889, Sarpi’s bigger-than-life statue stands at the scene of his suffering, the foot of the bridge where the assassination attempt on him occurred. Appropriate anti-church speeches accompanied its unveiling. Galileo got his monument 155 years earlier—a proof that physics is less dangerous than history—opposite Michelangelo’s in Santa Croce. He came minus a few body parts removed by souvenir seekers. Sarpi’s remains wandered further than Galileo’s, in and out of monastery, church, library, and private home, and may probably be as widely distributed as fragments of the true cross.29]

JB. I should add about my father’s interest in Galileo’s case that he very much approved of John Milton’s use of it in his pamphlet on the censorship of the press, which has some pompous Greek title, Areopagitica I think…

FC. What does it mean?

MW. It refers to an oration by an ancient Greek urging a return to government by aristocracy rather than by democracy, which he thought had failed. The title suggests the argument favored by all sides in our political debates: the way to mend is to return to the past. Thus Milton’s title, which suggests renovation, goes against his evocation of Galileo, the champion of innovation.

JB. Milton’s essay was one of the last things my father was able to read. Although he sharply prosecuted people whose writings he considered seditious, he did not like the practice of censorship before publication, especially of matters having little or nothing to do with the royal prerogative. I remember his reading to me in Oxford Milton’s powerful image of “the famous Galileo, grown old a prisoner of the Inquisition, for thinking in astronomy otherwise than the Franciscan and Dominican licensors thought.”30 My father must have taken Galileo as a symbol of legitimate questioning suppressed by improperly exercised authority.

Ambiguities

MW. Can it be that simple, John? If your father judged that Galileo’s behavior was seditious, then, as you said a minute ago, he would have thought punishment in order; Urban’s fault, if any, was its severity. Galileo may have suffered more than strict justice required, but that does not make him “a symbol of legitimate questioning.”

JB. Galileo was an ambiguous figure for my father. As you say, he disapproved of Galileo’s disobedience to the order issued to him by his legitimate prince, Paul V, and the prince’s agent, Cardinal Bellarmine, to keep silent about world pictures. Father distinguished Galileo’s behavior from Sarpi’s. He admired Sarpi without reservation; in doing his best to undermine the Roman establishment, he was following the order of his prince, the doge.

MW. But Sir John opposed the Crown in parliament and tried to change the king’s mind when Chief Justice. This was not quite doing his duty as you say he saw it.

JB. Well, yes. The answer is tied up with the larger question of his ambivalence over Galileo. Like many open-minded men of his generation, he was content to leave politics and religion fuzzy. He recognized that the claims of royal prerogatives, parliamentary privileges, and the liberties of the people were fundamentally incompatible. When everyone forbore, the peace for which King James and King Charles were lauded stumbled on. The same sort of unstable equilibrium existed between the Arminian church and the Calvinists. Unfortunately, Laud had too weak a mind to be able to keep things fuzzy.

MW. That is why when confrontation loomed each side insisted that it was merely trying to return to an earlier state of exemplary balance. That imaginary state, ill defined, obscured by time, was a perfect subject for fuzzy thinking.

JB. A good illustration of the importance of forbearance is the religious behavior of the Stuart queens. Anna did not parade her Catholicism and King James did not make an issue of it. Henrietta Maria constantly flaunted hers and so helped to destroy her husband. During his pursuit of the Spanish match, James may have thought that his son would have no more trouble with a Catholic wife than he had.

FC. Shall we add foreign policy and astrology to the list of items saved by fuzzy logic? Maybe King Charles’s foreign policy was not transparent enough to be fuzzy. The situation is clearer in astrology. I can believe that the sun and moon influence the growth of lettuce but not that the planets determine what I put in my salad. It is hard to know where to draw the line.

JB. I am tempted to suggest an analogy between della Bella’s frontispiece, with its suggestive blurred figures, and the hardline version of van der Heyden. Della Bella’s version aligned with my father’s political philosophy, which was to avoid hard confrontations. He knew that the Roman establishment had made a big mistake in meeting Galileo’s challenge with its own hard line. The pope had a choice: he did not have to regard Galileo’s conduct as a sort of sedition. Certainly, the Roman establishment erred in invoking Scripture against him. Father agreed with Sarpi that the popes had the bad habit of ascribing their misuse of authority to the dictates of God.

MW. Let me try to summarize what you have said, John, about your father’s attitude toward Galileo. As a lawyer and a judge worried about a nascent rebellion, he saw Galileo’s case as one of sedition; as an Englishman of the muddle-through school, he tried to dissuade people who insisted on challenging the fuzzy logic that underlay stable government in church and state; but, as an educated, just, and honest man, he thought that Galileo acted correctly, even bravely, in revealing what he had found that was useful to humankind and innocuous to true religion. That is the ambiguity, and the value, of Galileo’s image to thoughtful people.

JB. I would add that my father did not find muddling attractive. In points of law and treasury receipts he could be painfully exact. He did not like the dissimulation muddling entailed, even though his hero Sarpi and Sir Maurice’s hero Bacon recommended the practice. Father would have liked to argue in constitutional questions like his friends Selden and Cotton; but he saw that he might be more effective after the removal of Buckingham by blunting rather than sharpening opposition. Also, despite its remoteness and draftiness, he preferred Corfe Castle to the Tower.

MW. Politics is the art of the possible. Despite his occasional fulminations, King James understood this and avoided confrontation with humans by hunting animals. King Charles, Archbishop Laud, and my lamented patron the Earl of Strafford did not understand this; hence they left this world without their heads, while the English Solomon died intact in bed, perhaps, as it was rumored, with a helping hand from his dear Buckingham.

FC. It seems to me that Sir John Bankes might have exploited Galileo’s image more effectively and without the least fuzziness as confirmation of Sarpi’s exposure of the power grabs of the Roman church. What a convenient club to beat popes with! I wonder that our divines have not made greater use of it.

JB. Galileo was condemned in 1633, just when King Charles’s personal rule was stabilizing and his Catholic problem easing. I suppose that he did not want his prelates to undercut his policy toward Rome by pointing the lesson of Galileo’s continuing detention. And very probably the king regarded the disciplinary acts of the pope within his domains as legitimate if mistaken.

FC. Yes, King Charles and Pope Urban were then on friendly terms. I do not like to claim too much for my profession, but art more than politics was the reason of their mutual amiability.

JB. To say nothing of the influence of the queen and the papal agent Conn, who, to top the list of unlikely coincidences, was a friend and supporter of Galileo. My father had several conversations with Conn. He was a very witty and pleasant man and quite open about the ways of the court of Rome. So too was Bentivoglio, with whom Professor Greaves spent some time touring Rome. Their accounts almost make you feel sorry for people caught between their respect and friendship for Galileo and their obligation to their church and pope.

MW. However, ministers opposed to King Charles’s flirtation with the pope and to Laud’s vision of the church would have had no scruples against brandishing what we may call the Club of Galileo against Romanism. But here again we confront an unexpected limit. Blockheads like Ross, who would apply Scripture to quash all innovation, would rather destroy Galileo than exploit him.

JB. The implication, Sir Maurice, that people in the Protestant center are more likely to wield the Club of Galileo than those on the extremes is borne out in a book Bishop Duppa mentioned to me—I got to know him through Isham at Oxford. It is a verbose rambling around Proverbs 20:27: “The spirit of man is the candle of the Lord, searching all the inward parts of the Belly.” The author was a Platonist, so he ignored the bit about the belly and interpreted the candle as human reason. He then castigated Rome for blowing out the candles. “[I]f a Galilaeus should but present the world with a handful of new demonstrations, though never so warily, and submissively, if he shall frame, and contrive a glasse for the discovery of more lights; all the reward he must expect from Rome, is, to rot in an Inquisition, for such unlicensed inventions, for such virtuous undertakings.”31 To tie things off, I should say that Bishop Duppa liked to use the telescope as a metaphor for reliable investigation.32

MW. I accept Galileo as a symbol of legitimate inquiry suppressed by improper exercise of authority. But, while I acknowledge the depth and importance of Galileo’s contributions to knowledge, I blame him for setting back the cause of science with his insistence that he was right and all who disagreed with him wrong. The arrogance that infuses his writings runs exactly counter to the more tentative and sounder approach Bacon advocated. Galileo’s bullishness made it impossible for Catholic astronomers to debate freely about world systems.

JB. Sir Maurice, do you really question that the sun stands still in the center, and the planets, including the earth, circle around it?

MW. Yes, I do question it, although I think Copernicus’ system in Kepler’s version is far better than Ptolemy’s or Tycho’s. Maybe the world is not the sort of thing that has a center, either because it is infinite or because it has many centers equivalent to our sun. The arguments about world systems with which Galileo entertained us miss the great question. His Dialogue is one of the greatest books to come from Italy, but it is as much Ariosto as Copernicus.

JB. I see that in your deep way, Sir Maurice, you approach the position of suspended belief occupied by such odd bedfellows as skeptics and voluntarists.

MW. With a big difference: I consider the rational investigation of the natural world to be an obligation of human beings. Skeptics and voluntarists shirk this duty as, I regret, almost everyone else does. And this is very odd. It takes far less intellectual effort to master the intricacies of modern astronomy than to explain away the discrepancies in the Bible.

JB. Even astrologers, or some of them, do not care to decide whether the earth moves or the sun. I read in the reprint of Christopher Heydon’s defense of astrology that, since only the aspects count, it is not necessary to bother about the real layout of the planets. And I recall reading in Carpenter’s Geography that Sir Henry Saville once indicated his indifference to the question of world systems with the strange analogy that it was all the same to him whether, in sitting down to dinner, he went to his table or his table came to him. Nonetheless, his cook had roasted his dinner by rotating the meat over the fire, not by running with the fire around the meat.

MW. That is almost as peculiar an analogy as Viscount Conway’s argument that to move the gross earth among the light stars is as reasonable as requiring old fat people at a feast to dance while the young and vigorous sit still.33 He had not given the question his full attention. Most people, even educated ones, do not care whether the earth spins or not; they would take an interest only if it spun fast enough to throw them off. If they penetrated far enough into the Dialogue, they would perhaps be reassured by Galileo’s faulty proof that this could never happen.

FC. May I suggest, Sir Maurice, that people who manage to change things believe more strongly than they can demonstrate? They are the ones who make a difference, the Raphaels, Michelangelos, Sarpis, Galileos. People who withhold their assent, however correct their arguments, do not get their ideas into other people’s heads. Debilitating skepticism is as much a hazard of learning as debilitating omniscience. Both positions are frozen for fear of error.

JB. The omniscient Selden did not miss your point, Mr Cleyn. He argues in one of his books, there are so many, I don’t know which, that error honestly admitted can be a mighty source of advance. Galileo might be as great a source of fruitful error as of demonstrated truth. Already the Jesuits are bettering his measurements, and Gassendi and Descartes are trying to improve and extend his physics to apply to a Copernican world.

MW. By choosing the Dialogue as his text, Sir John separated himself from people who cry wolf at every suggestion of change and think that innovating is a prime qualification for a place in Hell. And yet, although we cannot admire those divines who rejected the Gregorian calendar on the ground that every alteration is for the worse, we cannot overlook that even improvements in the material conditions of our lives may have adverse unintended consequences.

JB. My father promoted devices and practices that he deemed likely to “improve man’s estate,” as Bacon put it, like the prolific inventions of the Moravian van Berg. He certainly understood the hazards. He championed the drainage of the fens, knowing that it threatened the ruin of the fen-dwellers, and he received some blame for it. We must have innovations and we must guard against them. Galileo is an inspiration and a warning.

FC. It is the human condition. Galileo can symbolize legitimate questioning necessary for science, as Mr Bankes observed, or, as Pope Urban thought, disobedient meddling subversive of religion; or, as we seem to agree, perpetual struggle between innovation and conservation.

JB. I remember that the first Copernican book you had me read, Sir Maurice, Wilkins’s New Planet, has at its first proposition something like, “That the seeming Novelty and Singularity of this opinion, can be no sufficient reason to prove it erroneous.”34

MW. If we are to believe what John Barclay wrote in his Mirrour of European minds, the English have the peculiarity of holding on to any law or custom, no matter how ridiculous, provided it is ancient, and yet in cosmology are willing to follow the strangest modern opinions, for which, of course, he takes the idea of a moving earth as exemplary.35

FC. Who was Barclay?

MW. A very popular French–Scottish writer trained by the Jesuits and pensioned by King James. According to his informed cosmopolitan opinion, it is almost impossible to make Englishmen accept anything new; and, in the rare cases that they do, they pick the craziest.

Multivalence

FC. What you say reminds me of what King Charles said when he came to see your portrait.

JB. A royal review? You never told us that.

FC. Well, I thought that he just came by to see whether I might be competent enough to paint his portrait. He considered many options after Van Dyck died. He was familiar with practical mathematics and emblems and even with my inventions on the borders of tapestries and recognized the Galilean frontispiece.36 Perhaps he was a closet Galilean. If I heard him correctly, he muttered, “Galileo could stand for me.” What do you suppose he meant?

JB. I would have thought that the king would identify himself with the rightful ruler (the pope) and Galileo with the upstart Parliament. Galileo was guilty of something like sedition for having defended the Copernican theory after it was judged contrary to Scripture, and King Charles, not to mention Star Chamber and my father, punished even trivial acts or statements they deemed challenges to the royal prerogative. Remember the case of the royal fool?

MW. Yes, and furthermore the late king and the late pope had many things in common through being sovereigns by divine right. That implied conflict, since the pope’s sovereignty extended in principle over all Christian kings. Still, there is a natural camaraderie among absolute rulers appointed by God when they are not at war with one another. It would seem unnatural for the king to see a reference to himself in the frontispiece to a book considered anathema by the pope.

JB. How then do you explain the royal remark that Mr Cleyn says he heard?

MW. Urban was then ruling absolutely in Rome and King Charles was fighting for the right to rule in any manner against a parliament led by people he condemned as traitors. They usurped his authority just as, in our Protestant teachings, the popes had usurped and corrupted the true Catholic Church. Parliament had become the pope and he, the king, a Galileo, trying desperately to persuade the usurpers to accept the naked truth he saw so clearly. In his days of power, Charles might well have seen parliament’s challenge to his right to rule as a parallel to Galileo’s challenge to scriptural authority over physics. With his subsequent change in fortune, Charles could see his and Galileo’s struggles as similar: Galileo trying to set the sun in the center, where it in fact belongs, and Charles striving to return to the center, where he thought he belonged.

JB. Bravo, Sir Maurice! It makes sense. During the heyday of personal rule, when the king enjoyed good relations with his court, managed religious dissent at home, and remained at peace abroad, he could identify with his fellow connoisseur and brother in divine right, the pope. When, however, his ill-advised war against the Scots forced him to face the reality that God unaccountably had given him the right to rule as he wished without the income to do so, he had a choice between conceding to the Scots or surrendering to parliament. He mismanaged things so badly as to be obliged to do both. When he muttered to Mr Cleyn about Galileo, he regarded himself as an embattled witness to the truth and perhaps foresaw his martyrdom.

FC. Yes, that must be the point, I remember that he said something like, “man cannot be blamable to God or man who seriously endeavors to see the best reason of things and faithfully follows what he takes for reason.”37

MW. Or, as Mr Quarles put it, the king’s opponents endeavored “To banish wisdom, that at last they may ǀ Make all the world, as ignorant as they.”38 That fits the Galileo case rather well. There is something else the king might have seen in the reference to Galileo: an unintended accusation against himself for his part in a process resembling the Inquisition’s proceeding against Galileo. I have in mind the mock trial of Lord Strafford, which ended in judicial murder. By signing the extra-legal bill of attainder, the king allowed the execution of a faithful servant. Similarly, Urban, by agreeing to or overlooking irregular procedures of the Inquisition, sentenced his old friend Galileo to perpetual house arrest. I suspect that history will judge the king and the pope harshly for these acts.

JB. I think we must add another reason. Probably the main cause for the destruction of the Stuart monarchy was religious strife, particularly between Puritans and Catholics. As we all know, the king would not enforce the laws against recusants against the wishes of his queen and his Catholic peers and advisers, and perhaps also because he did not want to; he disliked the Puritans, as he made clear by allowing the barbaric mutilation of those pious crackpots, Bastwick, Burton, and Prynne. There is good reason to think that, if left to himself, he would have countenanced Catholics who acknowledged his supremacy in everything but spiritual matters. In two words, he had nothing against Catholics who opposed the temporal claims of the popes and were willing to say so by subscribing to the Oath of Allegiance.

MW. And, of course, the very best examples of anti-Roman Catholics were the group around Paolo Sarpi. It makes sense to see Galileo as a distinguished representative of good Catholics, tolerable Catholics, able to make contributions to culture of the first order and acceptable within a Protestant state as fellow Christians once they foreswore allegiance to the pope. Would that have been your father’s view, John?

JB. Indeed. He saw that accommodation along these lines would be possible if only the pope would allow English Catholics to take the Oath of Allegiance or if parliament would decide not to require it. But Urban again drew a hard line and remained as inflexible as Paul V had been. So, although my father thought that Catholicism is a valid Christian religion, as, I think, King Charles and Archbishop Laud did, he regarded Roman Catholicism as a dangerous foreign power.

MW. Which returns us to our main question. Galileo’s Dialogue was condemned because the Roman Inquisition, following the advice of Roman theologians and philosophers, decided that it conflicted with passages in the Bible interpreted in their literal sense. Galileo had argued that the Bible has no authority over the matters of interest to him, which, he claimed, were to be decided solely by sensory experience and reasoned inference. Here you have a formal contradiction of authorities over questions that had not only not been resolved by the inspired writers of Scripture but had not even occurred to them; whereas anyone could look into them, and perhaps answer them, by the methods advocated by Galileo. These were the methods I put young John here to study in the book by Wilkins…

FC. I know it, that book with the bumbling buffoonery of a title page …

MW …at just the time that the brilliant Dr Harvey, the intrepid author of the unsettling theory of the circulation of the blood, was investigating the development of chick eggs. All sorts of other freethinking took place in wartime Oxford, some of which perhaps offended clear reason and good taste, but free and unmolested by irrelevant objections from slavish divines. Galileo is the pre-eminent example of the loss humankind would suffer from the suppression of unauthorized opinions. And I am sure that Oxford freethinkers, or anyway those whose freedom had not made them ignorant, would have recognized this symbolic meaning of the Dialogue in our picture.

FC. I do not doubt that Galileo can stand as a symbol for any of these things, or for all of them, and also for himself, as a man most worthy of praise. But, with all respect, I must say that you may be missing the big picture by focusing on Galileo’s troubles. If we look on Galileo as the heir to the genius of Michelangelo, the Dialogue is a sublime product of the bravura, self-confidence, and profound culture of Renaissance Italy. Galileo knew art and poetry and could invent more cleverly than the devil. Already Sidereus nuncius showed him to be a new Columbus if not a new Michelangelo, and even better than Columbus, in the proportion that heaven excels earth, and peaceful exploration armed conquest.39 Sir Henry Wotton regarded Sidereus nuncius as the single most notable invention ever made anywhere, and, for its bravura, pure Florentine. Or so I remember his telling me.40 And the Dialogue is even richer in invention and arditezza. The book could stand for all good literature in all respectable subjects.

MW. Galileo not only gave the measure of human capacity by his example, but also, by his method, showed how greater heights might be attained. For this he makes a better emblem than my Lord Bacon, who preached the possibility of progress but did not recognize that Galileo was in its van.

Abstractions

MW. The problem for Bacon was that Galileo dealt in mathematical abstractions from physical phenomena. For Bacon, a successful physics had to be fuzzy: the mathematician’s compulsion to order everything by number fatally collides with all the “Idols” as Bacon called the obstacles that block our way to reliable knowledge.41

JB. If I remember correctly, the obstacles derive from general human traits, like lusting after simplicity (Idol of the Tribe); from individual idiosyncracies, like requiring exactness in all things (Idol of the Cave); for love of grand theories (Idol of the Theater); and for want of apt words (Idol of the Market Place). Did I get that right, Sir Maurice?

MW. Yes, indeed. And, to break the hold of those Idols, he recommended fitting philosophers with lead boots, to prevent speculative flights. Galileo plumped for the opposite extreme: true philosophers are like eagles, and every effort should be made to abet their flight. There were not many. Galileo could think of only one eagle beside himself: Kepler. Most other philosophers flock together like starlings and foul the ground beneath them.

JB. And yet Galileo insisted when criticizing Aristotelian physics that the only reliable natural knowledge comes from “sensory experience and necessary deduction,” not from mathematical abstractions. How, good doctor, are we to heal the fracture between these views?

MW. You must begin with the assumption that nature is inherently mathematical, or, as Galileo put it, that the book of nature is written in geometrical language. I suppose he meant that the goal of physics is a mathematical description of observed phenomena, as in planetary astronomy. This was a very bold program, indeed, his boldest. There was (and still is!) no convincing reason to think that a mathematical physics is possible or even desirable, no matter what Descartes says.

FC. Why should a mathematical physics have been a bold idea if a mathematical astronomy had existed since the Greeks, and maybe earlier?

MW. A good question, Mr Cleyn! It is because the astronomer is at liberty to invent geometrical constructions, like circles moving perpetually on circles, or around empty points, that have no real existence: all that is required is that the fictitious geometrical motions describe the choreography of the planets closely enough that you know where to look for them. It is clear that such a mathematical astronomy is possible, since we have one, or rather several, Tycho’s and Copernicus’ being the best. Experience shows their utility. We use our knowledge of the motions of the stars for navigation and, if you believe in astrology by aspect alone, to forecast using a false system, as Sir Christopher Heydon allowed, and as Mr Lilly does, sometimes successfully.

FC. So why can we not be confident that a mathematical physics is possible and practical?

MW. For two reasons. Experience does not suggest that motions that occur beneath the moon are regular enough to be describable mathematically: you need only to consider the weather to be persuaded of the impossibility of any such description. It does not seem likely that we will ever prognosticate it reliably. Do you think that mathematicians will be able to predict the occurrence of volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, thunder and lightning, as they now do eclipses?

JB. I remember reading in Aristotle’s Physics that its subject is not events that take place by strict rule, but those that happen “for the most part.” That implies that a mathematical physics is impossible. And Aristotle may well be right: Galileo’s arguments to the contrary cover a very limited domain and in fact do not agree perfectly with his own experiments.

MW. The second reason to doubt the possibility is that we are not free to invent every fiction we find convenient to account for the behavior of objects around us. We have ideas about matter, cause, time, space, and so on that mathematical fictions should not violate. One of the most important consequences of the sun-centered system is to force people who believe in it to develop a physics that allows the earth—“the heavy sluggish earth,” as anti-Copernicans put it—to move around the sun. A theory adequate to the job would join the earth and the heavens, and physics and astronomy, in new ways. The only such theory that existed before our time is astrology.

JB. Does that mean that there is less fiction in physics than in astronomy? And, consequently, that, in trying to mathematize physics, Galileo labored under greater constraints than Ptolemy?

MW. Exactly. Galileo tried to escape the problem by avoiding forces and causes whenever he could. He wanted to reduce the amount of physics required by letting geometry do most of the work. That is the modern spirit, according to Galileo’s great admirer Hobbes, who says somewhere that “most of what distinguishes today’s world from primitive times is owing to geometry.” On this reckoning, Galileo’s theory of the tides is postmodern. He has the oceans respond to the two Copernican motions of the earth, the daily spin and the annual circuit, without any physical connection between the earth and the moon. I doubt that that is the way to success. What does Virgil say? Felix qui potuit rerum cognoscere causas, which might be rendered for present purposes “whoever would succeed in physics should ascertain the causes of things.”42

JB. Galileo’s famous account of the ballistic trajectory, the path described by a cannon ball, suffers from, or profits by, the same trick. He again obtains his answer by combining motions—the constant straight-line velocity of the ball along its original direction of flight and its accelerated fall to the ground—without discussing causes. That allows him to omit the cause that makes the real path very different from the perfect parabola he calculated. This is the resistance of the air to objects moving rapidly through it.

FC. To get persuasive results, Galileo had to abstract the object of study, say the flight of a cannon ball, from the confusing details that obscure it. Just so the portrait painter must ignore the humdrum and ordinary circumstances of his sitters to bring out their characters.

JB. The artist and the mathematician have to solve a similar problem. They both deal in caricature, and a good caricature can reveal much more than an image full of detail that is hard to grasp.

FC. Perhaps Van Dyck’s projections of King Charles as a mighty man among his people and as a wise governor and faithful husband parallel Galileo’s cannon balls that fly without hindrance. Both representations contain some truth, but not all of it. I would place Van Dyck’s portrait of Bentivoglio (see Figure 9), perhaps his best, certainly one of his most famous, in the same class: we see the heart and soul of the man, and his gentleness, but not the bodily strength that enabled him to sustain long marches during the wars in the Low Countries.

JB. We see what we are looking for and disregard the rest of the world. Your double portrait, Mr Cleyn, is a compelling depiction of a listless melancholy young man and a sympathetic doctor.

FC. You were a compelling model, Mr Bankes. You were very melancholy, in both the Galenic and the Aristotelian senses. Your appearance confirmed the medical diagnosis and your interest in astronomy, represented by Galileo’s book, was in line with the pastimes of the children of Saturn. I painted you as I saw you and as Sir Maurice seemed to see you. You were sick and suffering, as was the monarchy; despite the sage advice of Greaves’s brother the doctor, melancholy stalked Oxford. We were horrified to think that neither you nor the monarchy had long to live. But while there’s life there’s hope. The globe and chart-like telescope in the picture referred to this hope; doctors of melancholy prescribed travel as a preeminent cure.

JB. Your portrayal satisfies all of Sir Henry Wotton’s tests of a good rendition—“the Story…rightly represented, the Figures in true action, the Persons suited to their severall qualities, the affections proper and strong.”43 And your rendition of the frontispiece is a perfect example of expressive caricature, for with a few strokes you recover its essence and leave the knowledgeable viewer the task of supplying the details. That is just where Galileo’s parabolic trajectory left artillerymen.

MW. As long as we are flying high on the wings of analogy, I submit that the masques that delighted our sovereigns and their courtiers have something of the same nature. Certainly they were caricatures! They are stocked with ideal types that everyone recognized as Platonic and hoped might prompt great persons to emulation. Just as the abstractions of mathematical physics may allow some control of nature, the abstractions of character in a masque may modify behavior of individuals. It may be a great discovery that masques and mathematics have something in common, but I will not press it.

JB. Sir Henry’s little book on architecture teaches that too great accuracy in rendering a scene or person can be as bad as poor drawing. He says that there are some “Artificers so prodigiously exquisite” they are just too good. In trying for truth they privilege naturalness over gracefulness.44 Exactness can diminish that "free disposition…which doth animate Beautie where it is, and supplie it where it is not.”45 Galileo says the same thing in the Saggiatore.

FC. I agree with him entirely. The artist cannot simultaneously render a scene or a person with complete accuracy, with every wart and speck of dust, and also portray true essences or characters. They are what you may call “complementary values.” You cannot express both perfectly at the same time and by maximizing one of them, you will ruin the other. You must smudge a bit to come close to evoking the desired emotional response. Again we meet the double blunt edge of fuzziness. Clarity is the enemy of truth; emotional response can be dangerous…I wonder what Sir Henry would have thought of my picture.

MW. You will turn us into necromancers, Mr Cleyn! But perhaps we can work out an answer from common knowledge about the man and a few details I learned from Lord Strafford.46 Sir Henry would have given high marks to the handling of complementary values. You, John, are shown melancholic, but whether from illness of the body, as suggested by your pasty face, or of the soul, as suggested by your mathematical studies, or, most likely, both, or whether from being adolescent, is left to the viewer to resolve. I am depicted as a worried man; but whether as a tutor and doctor for both forms of your ailment, or as a distressed witness to the collapse of government and the judicial murder of Strafford, or as both, may be debated. The compass, globe, telescope, and book are each rendered with the degree of exactness appropriate to its function: thus the compass is presented in the greatest detail, to suggest costly mathematical instruments and a knowledge of their use; the globe only generically, to suggest travel in general; the telescope, with sufficient features to suggest an up-to-date model; and the book—that Sir Henry would have liked particularly—evoked with only the brushstrokes needed to identify it.

FC. Very brilliant Sir Maurice. But perhaps the painting is so impressionistic because I never finished it. There was a great rush, as you remember. It was a difficult time. And then, how do you know when a painting is finished? Leonardo worked on some of his for a lifetime, while Rubens and Van Dyck knocked theirs off like suits of clothes. But you did not finish with Sir Henry’s evaluation of the painting. What would he have made of the reference to Galileo?

MW. He would have understood it as he and his friend Donne did Sidereus nuncius, as a threat and a promise, an ambiguous comet, a herald of a great upheaval.

JB. It appears from some stray remarks in the Elements that Sir Henry did not live in Galileo’s world. He takes as a theorem that heavy bodies fall to the center of the universe and praises Aristotle, from whom he learned it, as “our greatest Master among the sonnes of nature.” Sir Henry worked a curious reference to Tycho into his epitome of architecture. It should amuse you, Mr Cleyn. Sir Henry allowed a limited use of grotesques but had no time for grottoes. If you have one on your grounds, he advised, convert it into an underground observatory, “whereof mention is made among the curious provisions of Tycho Braghe the Danish Ptolemie.” Sir Henry took Tycho, not Copernicus or Galileo, as the prince of modern astronomy.47 To finish with Sir Henry, I suppose, given his attachment to Sarpi and the Venetians, he also would have understood the reference to Galileo as an indictment of the Roman Catholic Church, which showed its true colors by insisting that the world system must conform with a few obscure or metaphorical passages in a text written two millennia before the invention of the telescope.

FC. My good sitters, I have learned much that surprises me, and used as I am to thinking in symbols, I cannot absorb any more today. Also, it is getting dark, and I must be going. The law might be observed in Gray’s Inn, but not invariably between it and Covent Garden.

MW. And we—I think that I can speak for Mr Bankes too—have learned many things from you. But before we part, please bring our conversation to a conclusion by telling us what you had in mind when designing the painting.

FC. My designs usually tell a story. So, Mr Bankes, when Sir Maurice asked me to put Galileo’s book in the painting, I thought how it might be done so as to indicate the esoteric nature of the studies you were then pursuing so avidly. That meant avoiding anything so trivial as presenting the book spine forward with its title and author clearly inscribed on it; and anyway I wanted it open, as a closed book suggests a closed mind or finished subject. A good example of what I wanted to avoid is Zubarán’s stupendous portrait of Diego Deza, Archbishop of Seville and Grand Inquisitor of Spain. Deza, looking very severe and elegant, sits at a table on which rest four closed volumes of theology (Figure 62). A marvelous depiction of a refined bigot! The uninformed viewer would have no idea that Deza had been the main champion of Columbus at the court of Ferdinand and Isabella. I wanted to tell a more complete story of my sitters.

Figure 62 Francisco de Zubarán, Fray Diego Deza (1630).

MW. And so you exhibited Galileo’s Systema as an open book to signify an ongoing inquiry, and omitted its title so as to suggest the esoteric nature of the subject, since only people who had had the book in their hands would have been able to recognize it in your sketchy figures.

FC. Also, I thought that della Bella’s design, of which you know I am a great admirer, would stick in the mind of anyone who saw it. I posed you, Sir Maurice, with your right hand on the globe, which, together with your empathetic gaze, suggests Mr Bankes’s opportunity to explore the great world beyond Oxford; which Mr Bankes does not seem to want to do, as he gestures listlessly toward the globe and looks over the telescope toward the open book. I apologize for botching your left hand, Mr Bankes, I would have fixed it if I had had time to revise.

JB. No apology needed, Mr Cleyn. It is true that I was more strongly drawn to astronomy and cosmology than probably was fitting for the heir of a great landed lawyer. I remember that telescope, which Professor Greaves showed me how to use. I suppose you put it under the globe, Mr Cleyn, to emphasize its application to travel. I took one with me when I went to Europe and found it very useful for seeing towns and travelers at a distance and paintings high up in churches.

FC. You give me too much credit, Mr Bankes. I put the telescope there to draw attention to it and the book, which incorporates and interprets the great discoveries Galileo made with it.

MW. Still, I suspect, we have not got to the essence of the painting. For example, what is the other book? I cannot believe that it is there just as a paperweight. You do not waste opportunities like that, Mr Cleyn.

FC. Sir John handed me the book and asked me to put its title on the spine. Its omission was one of the casualties of haste. But I did scratch the title on it so that I would not forget it when I came to fix up Mr Bankes’s hand and other details. I think that you can just make out a few letters despite the need for cleaning.

JB. Yes, I see an “H” and an “i” followed a little further on by what looks like a “t”. Is it “History”?

FC. Yes. I took it as a clever opposition to the Galileo: the closed book of history holding open a dramatic portrayal of present discovery. Which also points to future improvement through reasoned dialogue among people of good will. The past is the necessary foundation of the advance of humankind, but not a dictator of direction or scope.

JB. That is very likely, Mr Cleyn. But, as Sir John usually had more reasons than one for his actions and had too strong a sense of symmetry to pair a particular volume indicative of the future with an unidentified general history, the closed book must have been something special. I am morally certain that it is the Corfe Castle copy of Sarpi’s Trent. It certainly has the right girth! Nothing could have been more appropriate. Or more eloquent of my father’s last judgment on the affairs of church and state he had seen and suffered.

MW. He suffered from trying to do his duty to both prerogative and privilege, from struggling to reconcile his deep loyalties to the king and the Common Law. The conflict could easily bring on a fatal attack of melancholy.

JB. Galileo’s book might represent Sir John’s last thoughts about this enduring problem. He came to see that Galileo’s brave defiance of an unjust order of legitimate authority was a responsible, not a seditious act, and that peaceful dissent is compatible with stable government.

MW. That seems a plausible explanation of the hieroglyph as far as Sir John was concerned with it. But he did not make the painting. What was on your mind, Mr Cleyn, when you joined us with your subtle evocation of Galileo?

FC. Sir Maurice, for me Galileo represents the highest attainments possible for unaided human reason energized by curiosity and ambition; and you two melancholy gentlemen (please forgive me!) the perfect embodiment of doubt and lethargy. Will Mr Bankes continue stupefied by traditional teachings or wake up, seize the instruments, and add a few more pages to the open book of knowledge? Or will he shun the light and sink into that disabling melancholy that Mr Burton described so powerfully?

JB. Am I right in thinking that you placed us so as to indicate a gap of merit between real melancholics and a virtual Galileo?

FC. Yes, Mr Bankes, but I placed within the gap the means by which you and posterity could not only close it but advance far beyond the level of Galileo. These are the instruments of exploration and discovery, which I represented by those now essential to navigation. For, as Sir Francis Bacon assures us through his wonderful image of the ship passing through the Pillars of Hercules with its invocation of the prophet Daniel, “many will pass through, and knowledge will be increased.”

JB. I suspect that there is much more that you might tell us about the picture. You are famous for telling several stories at once.

FC. Well, there is a little something more about the way I portrayed Galileo’s Dialogue. Is the symbol or motto of your university not an open book?

MW. It is indeed, Mr Cleyn, and what is written on it is Dominus illuminatio mea. Your artistry is uncannily subtle if you intended to suggest the profound association I now perceive between the Oxford slogan and Galileo’s book.

FC. I am not very clever, Sir Maurice. Tell me what I have done.

MW. Dominus illuminatio mea are the first words of Psalm 27. The first of its six verses express optimism, confidence in the future, full faith in God’s protection: “Though an host should camp against me, my heart shall not fear: though war should rise against me, in this I will be confident.” The next six verses are pessimistic. The psalmist no longer takes God’s protection for granted: “Hide not they face far from me…Deliver me not over unto the will of mine enemies.” The psalmist does not choose between these attitudes, but advises: “Wait on the Lord: be of good courage, and he shall strengthen thine heart; wait, I say, on the Lord.”

JB. Wait not upon the Lord, but depend upon yourself, is not the message of the psalm, but the only reasonable reply that experience suggests to it. Despite all the recent persuasive evidence to the contrary, let us read our portrait as Mr Cleyn suggests. In a passage that scandalized bigots and naysayers, Galileo boldly proclaimed that we can understand some propositions as well as God Almighty and can apply their truths to improving our circumstances. To be sure, God knows many more propositions than we do, and, in our fallen state and current confusion, the few we can grasp with absolute certainty are mathematical. “But with regard to those few [propositions] which the human intellect does understand, I [Galileo] believe that its knowledge equals the Divine in objective certainty, for here it succeeds in understanding necessity, beyond which there can be no greater sureness.”48

Our interlocutors did not have much reason for optimism. Cromwell and his Commonwealth were in the ascendant. Any journeyman stargazer could predict from the conjunction of seven planets in Pisces scheduled for September 1656 that much worse was in store. Just such an assembly had happened the year before the Universal Deluge. The astrologer John Gadbury, who was not always wrong, could therefore most confidently predict that “the Politician will plague us with subtle and treacherous devices; the men in power with hard Taxes; the Countryman with want of Grain, the Soldier with wars and strifes.”49

John Bankes died of one of the maladies on offer in that dire year. Another two years and Cleyn and Williams too were gone. They missed the revival of fortune that came with the dispersal of the planets and the return, in 1660, of the Stuarts. Their picture did better. During the Restoration, Ralph Bankes reacquired many of the family’s assets, including knighthood, by which Charles II acknowledged the sacrifices of Chief Justice Bankes. Sir Ralph was able to commission a splendid villa at Kingston Lacy by Roger Pratt, who designed in the style of Inigo Jones, and a portrait of himself by Peter Lely, who depicted him as an aesthetic version of his melancholic brother John (Figure 63). Among the lavish furnishings of Kingston Lacy were many fine paintings appropriate for display above the main mantelpiece. Ralph chose the double portrait of his brother and Maurice Williams for this honor.

Figure 63 Peter Lely, Ralph Bankes (c.1660).

In the inventory that specifies the portrait’s location, the painter’s name is given as “Decline.” It was an ominous slip. As Galileo remarked when naming Jupiter’s moons the Medici stars, man-made monuments all perish in the end and glory has a short shelf life. “For such is the condition of the human mind that…all memories easily escape from it.”50 Remodeling and forgetfulness have removed Cleyn’s picture from its original conspicuous place. As it fell in fortune it rose in obscurity. It now occupies a remote spot in a dark corridor at the top of the house, where it can still be seen if staff are available to open the upper stories to visitors.