Chapter 3

Systems Librarianship 103: Web Applications You May Need to Master

Engaging with library users on the web is no longer restricted to simply putting a static HTML file on a server and calling it a successful website.

—Kyle Jones and Polly-Alida Farrington1

With more than half of Americans accessing the internet wirelessly,2 a library’s web presence has become more important than ever. This responsibility may ultimately fall into the hands of the systems librarian.

Web Design

Libraries have been creating institutional websites since the launch of the graphical internet, extending their traditional roles as disseminators and organizers of information. While such sites generally started as static collections of information about the library’s hours and services, many libraries now take advantage of newer web technologies and techniques to create dynamically generated sites that house digital collections, provide off-site access to electronic subscription resources, and so on.

Due to the changing nature of library sites, web librarians have experienced a corresponding change in duties and expectations. Whereas many librarians began creating and maintaining their library’s web presence on an ad hoc basis, with just a minimal knowledge of HTML or of entry-level editors such as Adobe Dreamweaver, the rising expectations of internet users and the ability to facilitate a library’s mission through interactive technologies have raised the bar in many institutions.

Many library web designers now face multiple challenges, such as the need to provide sites that meet users’ growing expectations while still remaining accessible to users with disabilities, the onus for creating a selection policy for links, the need to make tough decisions as to which parts of the enterprise will be emphasized on the library’s front page, the responsibility to make the site usable on mobile devices, and the necessity of supporting more advanced technologies including database-driven sites, personalization, distance learning portals, and streaming webcasts.

Much of this can now be done with powerful (and open source) content management systems (CMSs), reducing the need for additional programming skills. Webmasters in some institutions, however, will still need to acquire skills ranging from programming and database design to graphics creation and video creation. Depending on the tools your library uses to manage the website, you may also need to familiarize yourself with languages beyond basic HTML, such as PHP, JavaScript, AJAX, Perl, XHTML, Ruby, and CSS. Tangential, although not specifically technical, issues for library webmasters include online copyright and privacy issues, linking development, and public internet usage policies.

Any aspiring web librarian should subscribe to the Web4Lib mailing list (www.web4lib.org), the Code4Lib community (www.code4lib.org) and journal (journal.code4lib.org), and the Journal of Web Librarianship (www.lib.jmu.edu/org/jwl). Also examine A List Apart (www.alistapart.com) for design tips and W3Schools (www.w3schools.com) or Lynda.com (www.lynda.com) for tutorials on almost any language you might need.

You may also be involved in creating an intranet for library staff in order to facilitate access to internal and external staff resources. This intranet, which can be hosted on your internal network server and made accessible only to staff machines, is a useful way to post and share staff documents such as personnel codes and library policies, training materials, answers to commonly asked reference questions, and schedules and calendars. This is a great time to take advantage of a CMS to give your staff the freedom to create and add their own content to the intranet without having to consult with you before making additions or changes.

Content Management Systems

A CMS is a tool that can be used to manage an entire website or collection of websites. Jones and Farrington sum up CMSs in their guide to using WordPress in libraries:

Structurally, a CMS is a type of software that allows for the online publishing and management of content, where content is defined by the author. The content is flexible and extensible, and it may exist or be created in a variety of sources but can be somehow interacted with by the CMS.3

CMSs can be huge time savers for systems librarians who are swamped with other responsibilities and tend to let the library’s website fall by the wayside. Since “always on” wireless internet access (via smartphones, tablet computers, and laptops) has become so prevalent, our websites need to provide all of the information our patrons are looking for in a modern, easy-to-navigate package. CMSs can do just that with little effort on your part.

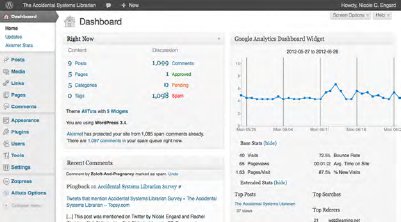

While you have your choice of many proprietary CMSs, libraries have flocked to open source offerings instead. The three major open source CMSs in libraries are Drupal (www.drupal.org), Joomla (www.joomla.org), and WordPress (www.wordpress.org; see Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 WordPress CMS dashboard

Of these tools, WordPress and Drupal have their own library-specific communities4 that you can turn to for advice and support. All three are widely used and well-documented online. Any one of these tools can be installed on a web server at the library or hosted off site, and each can be used to set up your library website so that staff members have the power to create and edit content without having to consult with a web professional.

Blogs

Libraries are also embracing the power of blogs to deliver updates to patrons. In Blogging and RSS: A Librarian’s Guide, Michael Sauers points out that “Today, librarians use blogs to share their experiences with their peers, while libraries as institutions use blogs to get information out to patrons. In some cases blogs are the core of a library’s website.”5

Most CMSs (including those just mentioned) provide the option of including a blog on the library website, either right out of the box or by using a plug-in. If your library already has a website and is just looking to link to or import content from a blog, you can take advantage of free hosted options such as WordPress.com (www.wordpress.com) or Blogger (www.blogger.com). Another option is to install a tool such as WordPress on your own web servers and use it to host a blog on your own domain.

While a full discussion of blogs is beyond the scope of this book, it’s important to be aware that blogs are used in libraries for more than just sharing opinions and original thoughts. A blog, for instance, can be an easy way to share information about events, book club news, and new acquisitions at the library. Always remember to see what other libraries are doing with these tools and learn from their successes. David Lee King offers some great insights to successful blogging language styles in Chapter 2 of his book Face2Face: Using Facebook, Twitter, and Other Social Media Tools to Create Great Customer Connections.6

Wikis

Wikis are among the other popular tools that systems librarians need to learn about. A wiki is another web-based application that you can install on your library’s web servers (or host outside of the library) to allow your colleagues to work together to create content. Many libraries use a wiki as the base for their entire intranet (as I did in the first library I worked in), giving staff members complete power to add pages and edit content on their own. This also promotes sharing and collaboration without too much effort from the systems librarian. Two popular and freely available wiki products are licensed under the GPL: MediaWiki (www.mediawiki.org) and DokuWiki (www.dokuwiki.org). You can also look into hosted options such as PBworks (www.pbworks.com) or Wetpaint Central (www.wetpaintcentral.com). The Library Success wiki (www.libsuccess.org), for example, uses MediaWiki to allow librarians to share their success stories (see Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2 The Library Success wiki

Mashups

Finally, when creating content for your library websites and intranets, remember that there are many free sources of data that you can use to enhance your content—and your website as a whole. Mashups are simply web applications that pull data from more than one source and bring them together as one tool.7 Libraries can use mashups to enhance their own data or to bring completely new information in to their websites. For more on mashups, see Library Mashups: Exploring New Ways to Deliver Library Data by Nicole C. Engard (Information Today, Inc., 2009) and mashups.web2learning.net.

Web 2.0

While the label “Web 2.0” has been beaten to death, there is no easier way to lump together the multitude of social web applications that you may need to understand in your role as systems librarian. If you’re managing your library’s web presence, then you’ll need to be aware of the many ways you can push library data out to the web. Social tools such as Facebook (www.facebook.com), Pinterest (www.pinterest.com), Google+ (plus.google.com), and Twitter (www.twitter.com) let libraries promote their services wherever their patrons are.

As a systems librarian, you may need to make sure that your library is present on popular social networking or Web 2.0 sites, write policies for participating in such sites, and manage the content posted by patrons or the general public on library-branded pages.

Programming

While programming skills are a luxury in many smaller institutions, some programming knowledge will be useful in larger environments (or in those requiring homegrown solutions). Whether you are writing original scripts to extend the functionality of your ILS or adding personalization features to your webpage, programming skills can be useful to many institutions. More systems librarian job ads are now specifying some sort of programming or scripting expertise, particularly knowledge of web technologies and related languages such as PHP and Ruby-on-Rails. Look to the programming titles provided by O’Reilly publishers for assistance in learning new languages quickly. Evaluate the market and the type of library you wish to work in before making a significant investment in shoring up your programming skills, but you should realize that there are situations in which such skills will come in handy.

Cloud Computing

Another technology that systems librarians need to be aware of is cloud computing. John Horrigan defines cloud computing as “an emerging architecture by which data and applications reside in cyberspace, allowing users to access them through any web-connected device.”8

The proliferation of wireless devices creates the need to store our information in one place and access it from everywhere. This is where cloud computing comes into play. For libraries, this means that more of our patrons will be coming to our libraries to access their files on web-based servers. It also means that more of our patrons will expect to store the data they find at the library in the cloud.

Finally, libraries are seeing more and more services offered as software-as-a-service, which is just a fancy way of saying “we’re hosting your software and data in the cloud.” It is for these reasons that today’s systems librarian needs to at least be aware of the term cloud computing and know what this means for any products the library has under consideration.

Virtual Reference

Virtual reference services can range from supporting emailed reference questions to implementing a live environment involving chat or instant messaging and the ability to “push” websites and other resources to remote users. The latter requires your attention to details ranging from selecting and setting up software and webpages, to training reference staff to interact in the online environment, to managing logs gathered from such live interactions.

Endnotes

1. Kyle Jones and Polly-Alida Farrington, Using WordPress as a Library Content Management System, Vol. 47, Library Technology Reports 3 (Chicago: ALA TechSource, 2011.), 5.

2. Aaron Smith, Mobile Access 2010 (Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project, 2010), July 7, 2010, accessed May 22, 2012, www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Mobile-Access-2010.aspx.

3. Jones and Farrington, Using WordPress as a Library Content Management System, 5.

4. For Drupal, there is Drupalib (drupalib.interoperating.info) and the Drupal4Lib mailing list (drupalib.interoperating.info/node/88). For WordPress, visit WP4Lib (www.wp4lib.bluwiki.com) and be sure to join the WordPress and Librarians Facebook group (www.facebook.com/groups/214139591937761).

5. Michael Sauers, Blogging and RSS: A Librarian’s Guide, 2nd ed. (Medford, NJ: Information Today, Inc., 2010), xi.

6. David Lee King, Face2Face: Using Facebook, Twitter, and Other Social Media Tools to Create Great Customer Connections (Medford, NJ: Information Today, Inc., 2012), davidleeking.com/face2face.

7. Nicole C. Engard, Library Mashups: Exploring New Ways to Deliver Library Data (Medford, NJ: Information Today, Inc., 2009).

8. John Horrigan, Use of Cloud Computing Applications and Services (Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project, 2008), September 12, 2008, accessed May 22, 2012, www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2008/Use-of-Cloud-Computing-Applications-and-Services.aspx.