Chapter 5

Organization of Knowledge

Proper planning and prioritization is critical to meeting the technological demands of library users successfully.

—Karen Knox1

Many noncatalogers look back on their required cataloging courses with a mingled sense of relief and disbelief. The organization of human knowledge, however, remains one of the foundations of librarianship, and, whether we retain a personal fondness for the intricacies of the MARC record, most librarians still love order. Cultivate the ability to organize the IT knowledge of your own department or organization, which will always stand you in good stead. The very process of working in the computer field will make you realize the importance of being able to find the correct piece of information quickly, whether you are looking for vendor contact information, system configurations, license numbers and registration keys, documentation, or any of the multitude of other details involved in managing technology in libraries.

Each institution will have its own mix of hardware, software, and other computer technology, as well as varying levels of complexity in keeping accurate track of technological resources. It is not necessary to catalog your technology holdings in full MARC format, but some type of organizational system is necessary whether you keep your records entered in a variety of databases or written down and filed in manila folders. This chapter contains suggestions on recordkeeping and statistics collection that you’ll need to do in all libraries; you can modify these requirements or methods of organization to fit your own institution’s needs. Find discussions on inventorying computer systems, tracking software licenses, maintaining support information, keeping good statistics on electronic usage, and creating useful documentation for others.

Inventorying

Maintaining an accurate tally of your computing assets is critical for a number of reasons. First, when you are creating a technology or strategic plan for your institution, you will need to be able to paint a complete picture of your library’s current computing environment. (For more on technology plans, see Chapter 10.) If you have not made a habit of keeping accurate records that describe how computer equipment and software are being deployed throughout your institution as these products and services are added, then you will need to conduct an inventory from scratch when it’s time to compose your planning documents. Maintaining an ongoing inventory (that can be modified whenever you purchase or modify computer hardware or software) will simplify the planning process and allow you to see an outline of your technology holdings at a glance.

You also may be required to keep an inventory of computer equipment as part of your library’s annual audit. An auditor will need to be told, and perhaps be shown, the locations of all major computer equipment you purchase during a given year to ensure that these purchases are actually being made for and used by your library. In a larger institution where it is not as easy to spot a newer item after the fact, it’s important to keep accurate records of where you have installed or replaced hardware in your library during any given year and to match up your inventory with purchase orders and invoices.

Each piece of equipment and each computer system in your institution can be labeled with an inventory number or a bar code, which can also be kept with invoices, documentation, and maintenance histories for easier match up. Any method that allows you to locate equipment quickly and to match it up with its information and invoices will suffice. There are other advantages for those who are willing to maintain inventory records. For example, an ongoing inventory will also help you keep track of the library’s computing environment and to know where and when you need to update, upgrade, or replace hardware and software. If you keep maintenance records as part of your inventory, you will be able to recognize at a glance which machines have been behaving poorly. You can identify how many printers you have and their particular make and model, which will help determine how many specific toner cartridges you may need to keep in stock. You can easily see when each machine was purchased, which helps you keep to a set replacement cycle and to tell at a glance if a machine is under warranty or a support contract. Although these points may seem minor, each piece of documentation is helpful to keep your library technology running smoothly and will save you time in the long run.

Licensing

You or your department’s staff will likely be responsible for tracking the software licenses your institution purchases. It is a good practice to ensure that your library complies with licensing requirements for any software deployed in your library, which requires accurate recordkeeping as to the number of installations, licenses, versions, and locations of particular products. If you are using newer Microsoft products in your institution through open license agreements, you will also need to create a Microsoft Passport account (also referred to as a Windows Live ID) and keep track of that user name and password, as well as the license and grant numbers for each piece of software your library uses.

Whatever you may think of Passport’s privacy and security implications, it remains a necessary evil for open license customers and many other institutions using current Microsoft software. To minimize your exposure and to ensure others have access to Passport records after you leave your institution, you may want to create a general library email account on your own mail server and use it solely for such registrations. It’s better to not use a free email service for this purpose, since you aren’t likely to receive any important messages regarding your registration if you fail to check and clean out your mailbox daily.

Grant and/or license numbers may also be necessary when you need to contact technical support about certain software. For example, if your antivirus software fails, machines are infected, or your server is somehow failing to download and install regular updates, then you can contact tech support immediately, but this often requires you to be able to locate and provide this information.

Ensuring licensing compliance will also prevent your institution from running into legal problems in the future. Software associations and companies are not generally swayed by either claims of poverty or of ignorance, and it is your responsibility as a systems librarian to be sure that your library is in compliance. This is one reason (other than the obvious support and ethical issues) to be wary of letting users install and use their own software; they may not think to put the good of the institution above their own convenience. You may wish to conduct a regular audit of installed software; you should create a policy stating that only systems staff may install software. At the very least, make sure to require staff to clear software installations with the systems department, or with you, if there is no formal IT department, before adding any programs to their machines. It is important to get the backing of your administration on this issue; describing the consequences in terms of possible fines for licensing violations and potential damage to users’ systems from illegal and unapproved software will help you make your point. (For more on ethical issues and systems librarianship, see Chapter 12.)

You may also be required to register software in order to activate it. While this process might seem to be an annoyance, especially if you need to register multiple installations, registering all software in your name with the general email address you’re using for such registrations will ensure you are on a vendor’s mailing list for upgrades and related offers (as well as for unrelated offers and junk mail, but that is another issue). Registration also allows vendors to inform you of patches and security issues with your software and of trials of new versions; some vendors will even offer free online seminars or other perks for registered users. For instance, Citrix Online (www.citrixonline.com), which produces GoToMeeting and GoToWebinar (among other products), emails registered users about opportunities such as online seminars and classes on how to hold effective meetings. If you fail to register your products, you may miss out on useful training opportunities. (See more on independent study in Chapter 9.)

Lastly, keep careful track of all registration keys for your purchased software. This is especially important if you have downloaded and registered software online. If the computer on which you have installed the registered version crashes or if you migrate to newer hardware, you will need the key to reinstall and unlock the software. Often, especially if you have purchased shareware from smaller independent vendors, you cannot count on their records to be accurate if you need to contact them and request that they reissue such a key. Smaller vendors might even go out of business before you need them again, so keep your keys and registration numbers in a safe place.

Support Information

Accurate recordkeeping is also crucial for you to support your library’s technology adequately. Beyond keeping track of where computer hardware and software are installed throughout your institution, it is useful to have system information handy for each machine, especially when you need to do an emergency reinstallation of hardware drivers or operating system. You will also need to know your systems’ hardware specifications when upgrading to a newer OS, such as when you move from Windows 7 to Windows 8. This will allow you to research whether a system will be capable of running a new OS smoothly before you begin the actual installation process and to locate and install device drivers that will work in your new operating environment.

At a minimum, keep track of items for each machine such as:

• Installed RAM

• Operating system version

• Network card model and manufacturer

• Wireless card model and manufacturer

• Video card model and manufacturer

• Clock speed

• Purchase date and system manufacturer

• Sound card model and manufacturer

This information is most easily recorded when you first buy the machine, but much of it can be retrieved from the system information found in the device manager. Also record IP addresses for each workstation; if these are set as static, as well as those for your network printers, it will allow easier setup when installing that printer on a newly purchased system.

You can keep your system information in an inventory database such as the one from Spiceworks (www.spiceworks.com/free-pcnetwork-inventory-software), or, if you are in a smaller institution, simply write it down (or keep it in a simple spreadsheet) and file it in a binder. If you are creating your own database or spreadsheet, use your inventory number or bar code as your primary key (or unique identifier) or file system information in order by number for easy retrieval. It will also be useful to keep a current detailed list of any maintenance and troubleshooting that has been done on these machines; this will help you identify “problem children,” see what has already been done, and keep track of how your time (and, if applicable, that of your staff) has been spent. (See the sidebar Sample System Information Sheet for a Microsoft Environment.)

Sample System Information Sheet for a Microsoft Environment

| Number: | Date Purchased: | Manufacturer: |

| RAM: | Processor Speed: | Location: |

| Windows Version: Windows OEM Number: | ||

| Hard Drive Model/Size: Network Card: | ||

| Sound Card: | ||

| Wireless Card: | ||

| Video Driver: | ||

| Printer(s): | ||

| Maintenance Record (include date, problem, and resolution): | ||

If you have the storage space, keep each computer system’s driver software and manuals together in its original box and label each with its inventory number. This way, if you need to work on the system, you will have everything you need close at hand. In your box, you may also wish to keep boot disks, warranty information, and any other useful material for that system.

Beyond keeping support information handy for each machine, you will also want to collocate your vendor contact information so that it is easily retrievable when you need to contact tech support. Make sure you have current phone numbers, website addresses, and email support addresses for all of your major software and hardware vendors. Keep track of when and why you have called each vendor and print out or file any webpages or emailed fixes and documentation they send you for future reference.

Statistics

Circulation statistics have long been a traditional measure of libraries’ usage. In an internet era, however, statistics on the usage of electronic resources and library public access computer equipment are equally as important as, if not more important than, traditional counts. A patron accessing an online database, visiting your website, emailing a reference question, or spending an hour typing a document on an in-house computer is using library resources, just as the patron who comes in to check out a book or ask a question at the reference desk is. In many libraries, electronic resources have replaced traditional print-based references; online full-text journal databases predominate rather than shelves of periodical indexes, for example. Yet, libraries often lack an accurate picture of how these nontraditional resources are being used.

Given the costs of online database subscriptions and other computer-based resources, having statistics on their use (and on any increase in their use) will help justify their recurring expense. These statistics will also help you plan for the future, since you can see which resources are being used most and how usage patterns change over time. If an expensive resource sees little use, you can either choose to publicize its availability and to offer training on its usage or to cancel your subscription and replace it with a database that will be more useful to your patrons. If you are continually maxing out your allowed simultaneous connections to a resource, you may want to invest in additional licenses. Statistics on electronic usage will also help you make decisions on which print resources to maintain; if users prefer electronic editions, for example, do you wish to maintain both versions?

Keeping track of statistics generated by your integrated library system (ILS) will be another useful way of seeing how people are using the library in nontraditional ways. What if in-person interlibrary loan (ILL) requests at the reference desk are down? Are they being replaced by patron-generated requests through the OPAC? Take advantage of any statistics you can generate or retrieve and use them to plan your future path. Run regular reports against your ILS database to get a picture of how these patterns change over time.

Most database vendors will supply monthly usage reports for their products. Unfortunately, note that these reports are not standardized across vendors and resources, so it can be difficult to use these vendor-supplied numbers to make strict comparisons between databases. Typical measurements include:

• Number of queries or searches

• Number of logins: This may be broken down into in-house and remote logins. If your database vendor is unable to distinguish remote logins made through your proxy server from in-house connections, you may need to compile your own statistics.

• Number of times users were denied access: If your license allows a limited number of simultaneous connections, this will give you an idea of whether you need to increase your allowed level.

• Number of items retrieved: For example, these might be individual full-text articles or abstracts viewed.

• Number of citations displayed

• Number of items retrieved, separated by title

• Number of items emailed

• Number of items printed

• Number of logins by time of day, day of week: This can be useful for seeing if your library is fulfilling the promise of 24/7 access and the use patrons are making of remote resources during nonlibrary hours.

• Amount of time used monthly

If your vendor does not seem to provide statistics in a timely fashion, you may be able to create your own rough measures by logging the traffic that passes through your proxy server. While this method will not provide an accurate picture of finer measurements, such as total numbers of searches and what types of articles are being accessed, it at least can let you know the number of times a database has been accessed from inside and outside your institution. Before resorting to this as your only measurement, however, check with the vendor; some supply statistics only upon request.

When deciding how to compile statistics on electronic resource usage, you may find the Useful Links compiled by the Statistics and Evaluation section of International Federation of Library Associations (www.ifla.org/en/statistics-and-evaluation/usefullinks) helpful. It consists of a bibliography on maintaining statistics in libraries and links to helpful sites in several countries.

You also may wish to monitor statistics on the number of fulltext journals the library provides access to through such electronic databases. Again, these numbers should be available upon request or regularly provided by the database vendor; they will help you demonstrate how the addition of electronic resources extends the library’s physical collection. You should also be able to access (or maintain) lists of journal titles that are included in the databases so that patrons can see whether and where a particular source they are trying to access is available. If you have purchased separate subscriptions to individual online journals, keep track of how these are being used as well.

Keeping similar statistics on the usage patterns of your website will help you make the argument for additional funding when it comes time to devote more resources to your online presence. These statistics will also let you target your efforts to enhance the areas that site visitors find most useful, or publicizing and reorganizing areas that receive little traffic. Patterns will be easier to track if you have first structured your website in a logical manner, as most major statistical packages such as Analytics from Webtrends (www.webtrends.com) track usage by directory (among other methods). These analytics products form the information from your web server’s logs into useful reports. These packages also generally provide useful information on the browser and operating system versions your visitors are using, which will help you make decisions about what browser versions to support when designing your library’s site. These reports are sometimes customizable, so you may need to work with your own reports or with your outside host to ensure that you are seeing the results that will be most useful for your purposes.

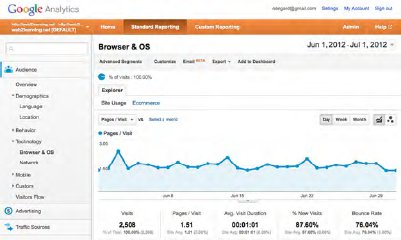

If you have your site hosted at an external web hosting company, note that most providers run a site analysis package on their servers and will be able to provide you with a URL where you can access regular (generally monthly) reports. If you are hosting your site on your own server, you will need to invest in such a package. Install a free log analyzer such as AWStats (www.awstats.sourceforge.net) or choose a hosted solution such as Google Analytics (www.google.com/analytics; see Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1 Sample Google Analytics for this book’s companion website

See if the majority of your website traffic originates in-house or if you tend to serve large numbers of remote users. As patterns change and more visitors come from the outside, you might need to increase the number of resources you provide to off-site users. If you do not seem to be serving remote users, you may have a publicity problem and will need to work on getting your site in search engines and directories, as well as increasing awareness among your patron base of the resources accessible from outside your physical institution. Provide these numbers to your administration and your publicity and reference departments to help them make decisions on how best to publicize electronic resources.

If you have an internal site search function, keep track of what visitors are searching for. Tracking can give you ideas of commonly used areas you may wish to beef up or items you might wish to add to your site. It can also give you an indication of whether your users are confusing your site search with general internet search engines and whether you might need to more clearly describe your search box or link. Note that some free search services (such as Atomz.com, for sites less than 10,000 pages) will keep search records and generate limited reports for you, but they usually require you to visit their site to generate a new index every time you make a change to your own webpages. Most content management systems have a built-in search engine already, and you simply need to choose the right plug-in to extract the data from it. Find a number of options for site search tools for your website and/or intranet at Search Tools for Web Sites and Enterprise (www.searchtools.com).When tracking your website usage, you may also wish to compile statistics on what type of connection (dialup, broadband, or mobile) your patrons are using to access your site remotely. For these types of “soft” statistics, you will likely need to survey your user population; consider posting such a survey on your website using a tool such as LimeSurvey (www.limesurvey.org). Other uses for surveys include finding out whether users are actually retrieving what they need from your electronic databases, whether they are able to identify which database will be useful by referring to your online descriptions before starting their search, and whether they find the online help screens to be user-friendly.

Keeping track of patron use of remote resources also extends to tracking how they are using your ILS. Are patrons using the personalization features of your web-based OPAC to check their accounts, place holds, renew items, and pay fines? (If not, what can you do to publicize the availability of these services?) What percentage of your OPAC access stems from outside your institution? You may also be responsible for using built-in ILS capabilities to create and run reports for other departments on more traditional library usage measures, such as number of items circulated, number of patrons registered, and so on.

Public and academic libraries will wish to track how public access computers are being used within the library. If you use signup sheets for internet access, for example, or if your time-management software compiles usage statistics, keep track of how many patrons use your internet terminals on a monthly and yearly basis. (You might also wish to keep track of how many people are turned away or how often users must wait for a machine when all terminals are in use, which can help you see if additional stations might be needed.) If you teach public classes on basic productivity applications, internet use, and/or OPAC functionality, keep track of how many people attend each. These numbers provide a rough measure to help you see whether you need to add more terminals or classes. Note how often patrons need computer help and the common questions that arise. This can let you see whether you need to create documentation answering frequently asked questions (FAQs) or whether you need to increase staffing levels on certain days in computer labs or public service areas.

You may want (or be required) to keep other statistics, depending on the population your library serves. If you have a number of distance education students making use of library resources, for example, you will probably want to track their use of automated ILL services and of any online email or chat-based reference services that your institution offers, as well as tracking how many technical support questions IT staff handles from distance education students. (Here, see whether there are common questions that may be better answered by composing an FAQ and making it available on the library’s website or by providing a technical orientation at the beginning of distance learners’ course of study.)

Documentation

Although you may not initially view the process of creating documentation for your library’s computer systems and services in terms of the organization of knowledge, your efforts at documenting will actually go a long way toward the effective organization and management of technology in your institution. Documentation in this sense includes organizing, collocating, and disseminating the knowledge that will help you and others succeed in your library’s technological environment.

Creating useful documentation for general users requires an awareness of the mindset of those who might be using a particular piece of hardware or software for the first time. Construct your documentation in a clear, logical manner and be sure to provide step-by-step instructions for common tasks. Be liberal with screenshots so that users can follow along in pictures and words to see if they are in the right place in your sequence of instructions. Most modern operating systems have some sort of built-in screen-capture capability, allowing you to select just a section of your screen for capture. There are also a number of low-cost screencapture programs that allow “capture with cursor” and the capture of sections of the screen; see for example Snagit (www.techsmith.com). Basic word-processing software is sufficient to create printed documentation in most library environments. If you’re looking to create more professional-looking handouts or guides, you can look into an open source desktop publishing application such as Scribus (www.scribus.net).

Documentation will be useful for both library staff and library users, although it may take different formats and levels of complexity for your different audiences. For library users, consider creating “cheat sheets” on accomplishing specific, common tasks, such as attaching a resume to email or looking up a title in your online catalog. You can supplement printed cheat sheets with more extensive online directions or direct users to resources (such as your catalog vendor’s online help screens) and titles your library owns on using specific pieces of software.

For library staff, you can consider posting relevant documentation on your institution’s intranet (this is where a wiki comes in handy) so that it is accessible to any staff member from any point inside the library. In a system or consortium where members use much of the same software, try collaborating with your peers in other institutions and sharing the documentation you create. There is no sense in reinventing the wheel if someone else has already produced a usable or easily modifiable document. In his survey response, Ata ur Rehman, head of the library at the National Centre for Physics Islamabad, noted: “Do not re-invent the wheel for any library need. … First try to find already available tools or techniques.” So before starting fresh, be sure to ask your colleagues on your online networks and mailing lists to share documentation they have written.

You may also wish to create a pool of documentation that you (and your systems staff) can draw upon. Document any support issues and their resolution so that if the situation arises again, it can be dealt with quickly. If you find you have a lot of these issues to document, you can try using a help desk ticketing system such as Request Tracker (www.bestpractical.com/rt) to track problems and keep a knowledgebase. Documenting server and network configurations will benefit you at a later date when you might not remember how you set up particular system. This will also benefit any systems person who steps into your position if and when you decide to move on. Think of the information that would have made your job easier and provide it for yourself, your staff, and your successor.

Overall, any organizational efforts you undertake are designed to make life simpler for you and your fellow staff members. As in the rest of systems work, your goal is to keep technology running smoothly and serving the good of the institution. Taking the time to keep track of how this is done will make everyone’s job easier. Taken together, all of your documentation, statistics, maintenance, and inventory information provide a concrete pool of evidence for you to point to in describing the importance of your department’s function to your institution. This information paints a picture of what you have done and of the technological environment that needs supporting.

Endnote

1. Karen C. Knox, Implementing Technology Solutions in Libraries: Techniques, Tools, and Tips From the Trenches (Medford, NJ: Information Today, Inc., 2011). Visit the book’s website at www.karencknox.com/ITSiL.php.