2

Museums

As soon as the notorious video was released, the blogosphere flooded with calls to action to protect antiquities from the locals—rehashing old imperial tropes about barbarism and civilization. Some argued that teams should be sent into Iraq, like the “Monuments Men” sent to World War II Europe, to rescue the cultural property that remained. “Now that Islamist madmen are on the loose across great swathes of the Middle East,” Hudson Institute fellow Ann Marlowe wrote in the Daily Beast, “we have reason to value the cultural imperialism of years past. It was rationalized, then, as saving treasures from barbarians. Whatever the truth of the matter in those days, there is no doubt now that the barbarians are back with a vengeance.”1 In a lighter vein, cartoonist Patrick Chappatte depicted two jihadists leaving the Mosul Museum—one saying, “My first time in a museum. This was awesome!” (figure 4).

4. Patrick Chappatte, “Mosul Museum Devastated.” February 28, 2015.

The day the video appeared, the director general of UNESCO, Irina Bokova, condemned the event as “a deliberate attack against Iraq’s millennial history and culture.”2 She called the destruction “a war crime” and insisted that “there is absolutely no political or religious justification for the destruction of humanity’s cultural heritage.”3 Other cultural institutions followed with statements in short order: “Speaking with great sadness on behalf of the Metropolitan, a museum whose collection proudly protects and displays the arts of ancient and Islamic Mesopotamia,” Metropolitan Museum of Art director Thomas P. Campbell wrote in a press release, “we strongly condemn this act of catastrophic destruction to one of the most important museums in the Middle East.” The “mindless attack on great art, on history, and on human understanding,” he asserted, was “a tragic assault not only on the Mosul Museum, but on our universal commitment to use art to unite people and promote human understanding.”4 The Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago called the destruction “deliberate vandalism” that constituted “a moral and cultural outrage.”5 The European Association of Archaeologists condemned the “cultural arrogance facing the world’s cultural heritage.”6 Cairo’s al-Azhar, Sunni Islam’s most prestigious university, issued a similar statement. “The destruction of cultural heritage is forbidden in Islam and rejected in total,” declared Grand Imam Ahmed el-Tayeb. “By claiming they are idols, Daesh [another name for ISIS] is committing a major crime against the whole world.”7

Notice the conflicting language. Where ISIS spoke of the need to cleanse the world of idols, their critics refer to a moral and legal imperative to protect cultural heritage. Though each side points to the same material objects, what they see is different. What is at stake in the difference between idols and heritage?

We have seen how Ibrahim’s campaign to rid the world of idols expressed a longing to free human life from a dependence on images. Only once human-made images are eradicated, Ibrahim surmised, can mankind genuinely serve God, whose rule requires a regime without images. But the purity of Ibrahim’s imagined regime is also the mark of its impossibility. Because politics is untenable without images, the repudiation of images as idols is tantamount to the rejection of politics itself. Those who see idols long for a world beyond politics.

What about heritage? As the inheritance of a people, heritage would seem to be a fundamentally political category. Abbé Grégoire (1750–1831), the French revolutionary who coined the term “vandalism” in an effort to dampen the iconoclastic fury that had overtaken France during the Revolution, made the protection of cultural heritage the foundation of his political project. National sovereignty, the Abbé thought, is protected not only by the tips of bayonets but also by the preservation of patrimony. He promoted this view by inverting the prophetic parodies of idolatry in the Bible.

For example, Jeremiah inveighed, “Every human is too stupid to know, every smith is shamed by the idol, for the molten image is a lie, and there is no spirit in them” (10:14). By contrast, in the Abbé’s Second Report on Vandalism (August 1794), he declared before the National Convention, “The ignorant see only a piece of crafted stone; let us show them that this piece of marble breathes, that this canvas is alive, and that this book is an arsenal with which to defend their rights.”8 In other words, iconoclasm, not idolatry, is the quintessential crime of ignorance. The 1793 law forbidding vandalism required that all objects of artistic, historical, or educational value be “taken to the nearest museum.” Not by chance, most of those museums were repurposed local churches—or, in the case of the Louvre, a royal palace. The new storehouses of heritage were meant to replace the twin pillars of the old regime: the church and the monarchy. Museums, and the heritage they housed, would serve an emphatically political purpose.

And yet, when the European Association of Archaeologists lambasted the Islamic State for cultural arrogance, it stressed that antiquities “in no way can be considered a component of ideologically active conflicts.” The ancient Mesopotamian objects housed in the Mosul Museum, in their view, are not images that help one political entity define itself against others but manifestations of civilization in its struggle against barbarism. That these objects belong to a region commonly called the “cradle of civilization” serves to underscore this point.

Though Abbé Grégoire was motivated by a concern for the French nation, his “vandalism” rhetoric prompted a framing of heritage preservation as an issue that transcends politics. Derived from the Vandals—one of the Germanic tribes that sacked and looted the Roman empire—the term connotes barbarian hoards threatening civilized life. Just as civilization supposedly stands above political divisions, barbarism is something that threatens from below. The conflict between civilization and barbarism is fundamentally different from a war between political enemies. Protecting heritage springs from a principle supposedly purer than politics: universal humanity.

The Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset relates a relevant story about Victor Hugo:

For the celebration of Victor Hugo’s jubilee a grand reception was organized at the Élysée Palace to which representatives of every nation came to pay their homage. The great poet took his place in the reception hall in a solemn statuesque pose, elbow resting on the marble of a chimney. One after another the nations’ delegates came forward from the crowd and presented their homage to the Master. An usher announced them in stentorian voice: “The gentleman representing England,” he proclaimed, and Victor Hugo, his eyes in ecstasy, his voice shot through with dramatic tremolos, replied: “England! Ah, Shakespeare!” The usher went on: “The gentleman representing Spain”; Victor Hugo, in the same vein: “Spain! Ah, Cervantes!” “The gentleman representing Germany”; “Germany! Ah, Goethe!” But a short man stepped forward, clumsy, chubby, of rustic bearing, and the usher announced with flair: “The gentleman representing Mesopotamia.” Then Victor Hugo, who until that moment had remained impassible and sure of himself, appeared troubled. His suddenly anxious pupils cast a broad look around that seemed to embrace the universe, searching in vain for something out there. But it soon became clear to the spectators that he had found it and that he once again mastered the situation. And with the same pathetic accent, the same conviction, he answered the pudgy representative with these words: “Mesopotamia! Ah, Humanity!”9

Hugo’s reaction is emblematic of a broader tendency, since at least the mid-nineteenth century, to associate Mesopotamia with the idea of universal humanity. As the supposed birthplace of civilization, Mesopotamia has come to symbolize what all human beings share. Because the civilization of ancient Mesopotamia stands at the dawn of human history, the unity of civilization is thought to predate—and so take precedence over—political divisions. This is the myth of the Tower of Babel transposed into a modern liberal key. “In the idea of world history,” writes Hannah Arendt, “the multiplicity of men is melted into one human individual, which is then also called humanity.”10 Mesopotamia is the quintessential symbol of that humanity and the concomitant longing to live beyond politics. Transcending politics in the name of civilization resembles Ibrahim’s aversion for political images more than one might think.

And yet one must wear special blinders for Mesopotamian images to appear as apolitical as the European Association of Archaeologists wants them to be. Consider an image that circulated on social media right after the sacking of the Mosul Museum (figure 5). It shows an arrow-pierced lion from Ashurbanipal’s palace in Nineveh captioned with the phrases “Stop the genocide of Assyria’s civilization” and “I stand with Assyria.” Most people who shared or “liked” the image on Facebook probably thought they were performing a political act in support of enlightened cosmopolitanism. Few would have recognized “Stand with Assyria” as a hashtag for the modern Assyrian nationalist movement, whose militia has battled not only ISIS but also Kurdish peshmerga forces and other groups. Does advocating the preservation of Assyrian antiquities mean one is taking sides in an obscure conflict in the Middle East, or endorsing nationalism over Enlightenment cosmopolitanism? Claiming that the images constituting heritage are apolitical is a facile way to sidestep such questions and avoid facing the implications of one’s own commitments. It is no less naïve to think these images are free of politics than it was for Ibrahim to think politics could exist without images.

5. “Stop the Genocide of Assyria’s Civilization.” Meme circulated online, March 2015.

The suffering Assyrian lion offers but one example of the complicated ways ancient Near Eastern objects have been entangled in modern politics since their rediscovery in the mid-nineteenth century. In her response to the ISIS video, UNESCO’s Irina Bokova referred to the objects being destroyed sometimes as Iraq’s cultural heritage and sometimes as humanity’s. Her statements echo an ambivalence that has accompanied ancient Near Eastern objects for as long as they have found homes in modern museums. Understanding the origins of that ambivalence can shed light on the meaning and fate of Mesopotamian images in our own day.

Museums are far from neutral spaces providing unmediated access to the objects in their collections. The objects are accompanied by narratives that give them meaning—narratives that encourage audiences to subscribe to particular visions of the world. The dream of unmediated access is as deceptive in a museum as it is illusory in political life. Replacing the language of idolatry with the language of heritage brings us no closer to unmediated truth than did Ibrahim’s acts of iconoclasm. Is it so clear-cut that museums are bastions of civilization, protecting our common heritage from destruction at the hands of barbarians? Is the value of antiquities self-evident, as if the narratives museums spin around objects were written unambiguously on their surface? Instead of blindly accepting the view that antiquities constitute a universal heritage whose destruction is barbaric, we ought to attune ourselves to how museums have cultivated this attitude and seek out what it keeps hidden from view.

●

Near Eastern antiquities have enthralled viewers from the day archaeologists began to rediscover them. As they have passed through the world’s museums, they have become laden with many meanings.

The modern story begins in 1842, when the French consul in Mosul, Paul-Émile Botta (1802–1870), set out to discover the ancient city of Nineveh. The last Assyrian capital had long been known to Westerners from the Bible and Greco-Roman historians. Medieval Christians often conflated its legendary founder, Ninus, with the biblical Nimrod. Fascination with the Assyrian empire had intensified in the 1820s—as attested by Lord Byron’s 1821 reading-drama The Tragedy of Sardanapalus (as Ashurbanipal was known from classical sources) and Eugène Delacroix’s The Death of Sardanapalus, first displayed at the Salon of 1827–1828 (figure 6). In Delacroix’s painting, the Assyrian king lounges nonchalantly as his empire burns; it is a scathing indictment of absolutist despotism, not least that of France’s restored king Charles X. Botta moved in the same Parisian circles as Delacroix before being appointed consul under Charles X’s successor, the “bourgeois king” Louis-Philippe. Originally trained as a naturalist, he undertook the search for Nineveh in the spirit of scientific advancement that defined his liberal age. “As usual, [the French government] has nobly encouraged these researches so important to history and so useful for a knowledge of ancient art among the bygone nations of Mesopotamia,” Botta wrote to Jules Mohl, his backer at the Société asiatique. “May such liberal intentions not be frustrated by ignorance and barbarism.”11

6. Engraving by Emile Thomas (French, 1841–1907) after Eugène Delacroix’s The Death of Sardanapalus (1827, Louvre). Le Monde Illustré, May 16, 1874. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Botta began his search on the large tell on the east bank of the Tigris River directly across from Mosul, by the village of Kuyunjik. Before long he moved his men sixteen kilometers northwest to a more promising mound near the village of Khorsabad. Within three days, his foreman, Naaman Ibn Naush, announced that the team had discovered decorated stone slabs and cuneiform inscriptions. The Ottoman sultan in Istanbul authorized a full excavation. Together with Eugène Flandin—an artist dispatched to assist in recording the finds—and a team of local workmen, Botta brought Sargon II’s palace of Dur-Sharrukin to light for the first time in over two thousand years.

Cuneiform script had not yet been deciphered, so Botta couldn’t know precisely what he had unearthed; he vaguely informed his supporters in Paris that he had “discover[ed] sculptures which may be assumed to belong to the time when Nineveh was still flourishing.”12 The first shipment of Assyrian reliefs arrived at the Louvre in January 1847. Botta remained in Mosul and continued excavating at Khorsabad until he was transferred to a lower position in Jerusalem in reprisal for his royalist stance during the 1848 revolution. (The French consulate in Jerusalem is today located on a street bearing his name.) The novelist Gustave Flaubert, who visited Botta in Jerusalem, described him as “a ruined man, a man of ruins, in the city of ruins.”13 Botta died, forgotten, in 1870.

Austen Henry Layard (1817–1894), one of the great archaeologists of the Victorian age, first met Botta when he stopped in Mosul on his way to Istanbul in June 1842—nine months before the Frenchman began excavating at Khorsabad. The twenty-five-year-old British adventurer in Bakhtiyari tribal attire had arrived from Baghdad after two years traveling throughout Persia. Layard had been in Mosul once before, in 1840, and glimpsed the ruins known locally as Nimrud, named after Ibrahim’s legendary antagonist. “As the sun went down,” he recounted in his Autobiography,

I saw for the first time the great conical mound of Nimrud rising against the clear evening sky. It was on the opposite side of the river and not very distant, and the impression that it made upon me was one never to be forgotten. After my visit to Kuyunjik and Nebbi Yunus, opposite Mosul, and the distant view of Nimrud, my thought ran constantly upon the possibility of thoroughly exploring with the spade those great ruins.14

Layard traveled to Kuyunjik with Botta, where the two men discussed their aspirations to uncover the remains of ancient Assyria. Three days later, Layard was on his way to Istanbul—where he would establish himself in the service of the British ambassador to the Ottoman empire, Sir Stratford Canning. When Botta’s finds at Khorsabad became public, Layard convinced Canning to support an expedition of his own to Nimrud. In the guise of “a traveler, fond of antiquities, of picturesque scenery, and of the manners peculiar to Asia,” Layard returned to Mosul in October 1845 and began digging at Nimrud.15

The first relief sculptures emerged the following month. Soon thereafter, Canning acquired a firman from the Ottoman grand vizier permitting Layard to continue his research and to send “antique stones on which there are figures and inscriptions” back to England.16 The first twelve cases set sail from Basra in the fall of 1846, were put on view by the Asiatic Society of Bombay that December, and finally arrived at the British Museum in June 1847. “They have created great interest,” the museum’s secretary of the trustees wrote to Layard, “and all who have examined them appear to be much gratified.”17 Layard would achieve celebrity and, eventually, a seat in parliament. His book Nineveh and Its Remains—part archaeological report, part adventure story—was a national bestseller.

The advancement of science (for Botta) and the thrill of discovery (for Layard) were inseparable from nineteenth-century imperial politics. Both men were commissioned by their governments to advance, respectively, French and British interests in the Ottoman empire. Their backers in Paris and London saw the expeditions as opportunities to enhance national prestige. Jules Mohl, president of the Société asiatique, expressed the official French attitude with his promise that “everything admitting of removal will be sent to France, and there form an Assyrian museum, unique throughout the world.”18 The frontispiece to Nineveh and Its Remains emphasized the immense effort required to haul away a colossal lamassu (figure 7). This image of British technical achievement echoes the Assyrian kings’ own display of imperial power—as Layard himself would discover while excavating Sennacherib’s palace at Nineveh just months after his bestseller was published (figure 8).

7. “Procession of the Bull beneath the Mound of Nimroud.” Austen Henry Layard, Niniveh and Its Remains, 1849.

8. Drawing by F. C. Cooper of an Assyrian relief depicting the transport of a lamassu, Court VI of the Southwest Palace at Nineveh, 1849. British Museum.

The Louvre’s Assyrian galleries opened to the public in the presence of King Louis-Philippe on May 1, 1847. “Whether Nebuchadnezzar, Sardanapalus, or Ninus (for we aren’t sure who he is), the Assyrian monarch has set foot on the banks of the Seine,” the newspaper L’Illustration announced. Alluding to the Louvre’s ambiguous status as both museum and palace, it observed, “He was destined for a new home worthier of him—the palace of our kings.”19 Louis-Philippe’s government also bankrolled Botta and Flandin’s magisterial five-volume Monument de Ninive—spending almost three times more on the publication than on the entire course of excavations. As the title suggests, the book served not merely as a document of ancient royal monuments but as a monument to the current king of France.

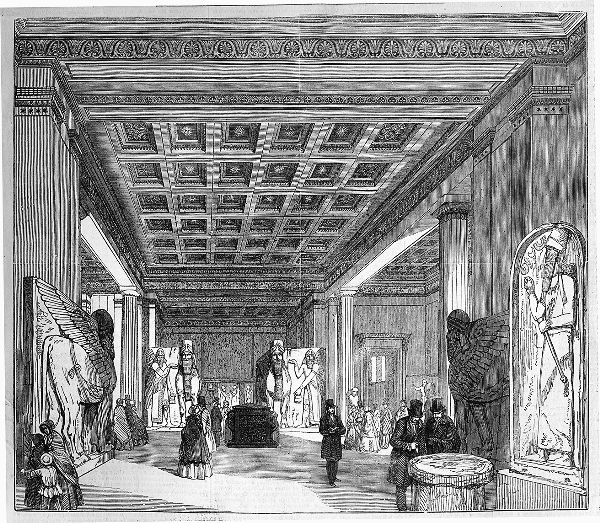

In this contest for national prestige, the British would not be outdone. In 1846 Layard’s promoter, Stratford Canning, assured the British prime minister that thanks to the discoveries at Nimrud the British Museum “will beat the Louvre hollow.”20 Installed the following year, the Assyrian works proved an immediate success with the English public. An etching of the museum’s Nineveh Room published in the Illustrated London News depicts the newly acquired objects in a gallery peopled with respectably dressed men and women; in the foreground, two men inspect a column base, while a mother explains a work to her two children (figure 9). In his study of the nineteenth-century reception of Assyrian antiquities, art historian Frederick Bohrer argues that the engraving offered the magazine’s wide readership an image of their ideal selves—dignified citizens of an empire that affords them the opportunity to contemplate a past configured to glorify their own present. It set museumgoing—not unlike churchgoing in the past—as a marker of civilized life to which all self-respecting citizens might aspire. Visiting the museum and practicing the behavior modeled in the engraving reinforced commitment to the empire that made civilized life possible. But such visits were not essential—the museum could assert its power even if one only visited it in one’s imagination.

9. The Nineveh Room in the British Museum. Illustrated London News, 1853.

“Look at these stupid foreigners!” the Ottoman sultan Abdul Hamid II (r. 1876–1909) reportedly remarked. “I pacify them with broken stones.”21 Though the Ottomans did take advantage of the European craving for ancient artifacts to advance their own state interests, the quotation taxes credulity. It was during Abdul Hamid’s reign, at any rate, that the Ottoman policy of preserving and displaying antiquities unearthed within the realm came of age. In 1869 the Sublime Porte, the empire’s central government, approved the idea of a “perfect museum” since “it is not appropriate that the museums in Europe should be filled and decorated mostly with antiquities taken from here, while we do not even have a museum.”22 The Ottoman government commissioned archaeology enthusiast and Paris-trained painter Osman Hamdi Bey (1842–1910) to undertake excavations at Mount Nemrud, a mountain in southeastern Turkey said to be Nimrud’s burial site (figure 10). Pleased with the results, Abdul Hamid II ordered that a building be constructed to house the finds.

10. Osman Hamdi Bey posing with the head of Antiochos on the western terrace of Mount Nemrud, 1883. Istanbul Archaeological Museums, Photographic Archives, 11190.

Under the direction of Osman Hamdi, the Imperial Museum in Istanbul provided a space where the diversity of the Ottoman empire could appear as a unity. The display of antiquities not only sought to rival the Louvre and the British Museum in prestige but asserted imperial coherence in the face of European incursions on Ottoman territory. This imperial message was carefully crafted through photographs. Included in Abdul Hamid’s exhaustive photo albums documenting the realm were images that show artifacts being carefully removed and transported using the latest technology—old and new working together to create a museum to promote the Ottoman state. The sultan presented sumptuous sets of these albums to the British Museum and the US Library of Congress in 1894. One could tour the imperial districts along the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers while sitting by the Thames or Potomac.

●

Imperial interests intertwined with aesthetic debates. When the first sculptures arrived in London, a parliamentary commission asked Sir Richard Westmacott, a professor of sculpture at the British Royal Academy and a trustee of the British Museum, for his opinion of the newly acquired treasures from the ancient Near East. “It is very bad art,” he replied.23

Layard disagreed. In 1845 he published an article praising the artistic worth of the objects Botta had discovered at Khorsabad. “To those who have been accustomed to look upon the Greeks as the true perfecters and the only masters of the imitative arts, [these finds] will furnish new matter for inquiry and reflection,” he remarks. “They are immeasurably superior to the stiff and ill-proportioned figures of the monuments of the Pharaohs. . . . In fact, the great gulf which separates barbarian from civilized art has been passed.”24 Even in praising Mesopotamian artistic achievement, Layard hews closely to the canons of good taste. He does not challenge the idea of a gulf separating barbarism from civilization; he just shifts the dividing line. To further assimilate Assyrian sculpture to nineteenth-century aesthetic standards, some relief panels were cut down to produce “portrait” heads and other recognizable artistic configurations.

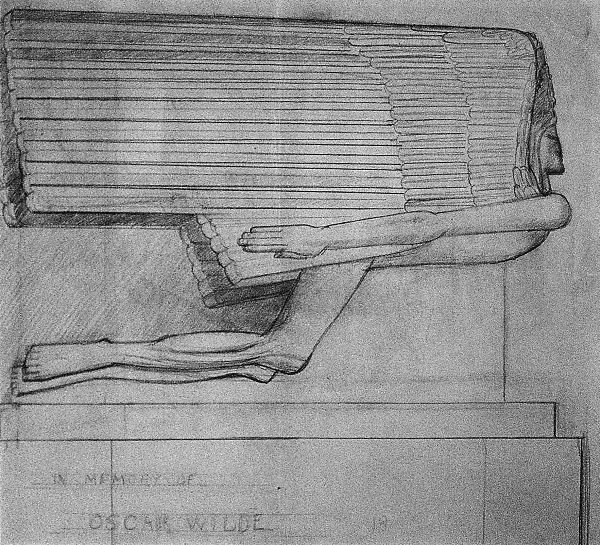

Whether “bad art” or not, the newly acquired Mesopotamian objects captivated the imaginations of modern artists. French symbolist painter Gustave Moreau filled a sketchbook with exquisite studies based on the Louvre’s Khorsabad reliefs (figure 11), and the sculptor Jacob Epstein based Oscar Wilde’s tomb in Père-Lachaise on the Assyrian winged bulls that dazzled audiences in Paris and London (figure 12). Years later, after the Louvre added Sumerian sculpture to its collection, the Swiss artist Alberto Giacometti transformed stately diorite figurines of ancient kings into whimsical line compositions using blue ballpoint pen. In America, film pioneer D. W. Griffith rebuilt ancient Babylon on Hollywood’s Sunset Boulevard for his ruinously expensive epic Intolerance (1916). The set featured both relatively accurate lamassu sculptures and totally inappropriate sculptures of rearing elephants. Griffith reportedly complained that the studio builders deviated from the research on Babylonian art and architecture he had compiled in a scrapbook now housed in New York’s Museum of Modern Art (figure 13).

11. Pencil sketch of Assyrian figures by Gustave Moreau, ca. 1860–1870. Musée Gustave Moreau, Paris.

12. Jacob Epstein’s study for the tomb of Oscar Wilde, ca. 1908. Courtesy New Art Gallery Walsall, UK.

Twenty years later, Alfred Barr (1902–1981), MoMA’s first director, ensconced “Near-Eastern art” in the story of modernism, summarized in a flowchart on the cover of the catalogue for his landmark exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art (figure 14). The influence of Mesopotamian sculpture of the first millennium BCE appears in Barr’s diagram between 1900 and 1905, a decade after that of nineteenth-century Japanese woodblock prints and just before that of “Negro sculpture” and the “machine esthetic” of contemporary industrial society. This convoluted chronology derives from a focus on form. “A work of art,” Barr asserted, “is worth looking at primarily because it presents a composition or organization of color, line, light and shade.”25 Barr’s formalist approach severs works of art from the political, economic, and cultural contexts of their production; what matters is how a work resolves formal problems internal to itself. As a purveyor of modernism, Barr did not so much produce new images as teach people to see all images in new ways. He held out the promise of a cosmopolitanism based on the appreciation of pure form; Near Eastern art had its part to play in bringing about this new order.

13. Page from D. W. Griffith’s scrapbook for Intolerance, 1916. Griffith Archives, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

14. Alfred H. Barr Jr.’s cover design for Cubism and Abstract Art exhibition catalogue, 1936. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

As Barr was preparing Cubism and Abstract Art, British sculptor Henry Moore (1898–1986) likewise affirmed the universal appeal of Near Eastern art. “For me,” Moore wrote in The Listener, “Sumerian sculpture ranks with Early Greek, Etruscan, Ancient Mexican, Fourth and Twelfth Dynasty Egyptian, and Romanesque and Early Gothic sculpture, as the great sculpture of the world.”26 As his list implies, Moore did not organize artistic traditions into a rigid teleological framework, whether of civilization or (as Barr had) modernism; for him, great sculpture could arise wherever and whenever social conditions were ripe. “It is not necessary to know their history in order to appreciate and respond to these works of art,” Moore asserts, since “once a good piece of sculpture has been produced . . . it is real and a part of life, here and now, to those sensitive and open enough to feel and perceive it.” The traditions that earned a place in Moore’s pantheon each communicated “a deep human element.” Knowing too much about a Sumerian sculpture’s temple function or the political ambitions that gave rise to an Assyrian relief could only obscure our vision of the “human element” that justifies our engagement with (and possession of) these works of art. Mesopotamian art “belongs to all of us” not because we (or our ancestors) fashioned it, but because we can all appreciate it.6f

The tympanum welcoming visitors to the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago celebrates the ancient Near East in a different mode (figure 15). At the center of the composition, designed by the institute’s founder, James Henry Breasted (1865–1935), a figure holds an archaeological fragment inscribed in Egyptian hieroglyphs with the phrase “We behold thy beauty.” But who is this “we”?

15. Tympanum over the entrance to the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, after a design by James Henry Breasted.

The tympanum does not characterize this appreciative audience in the universal humanistic terms espoused by Moore. Instead, it situates the appreciation of beauty within a transfer of heritage from ancient East to modern West. The scene depicts a reverent youth representing the West receiving civilization from an Egyptian figure, the latter flanked by a lion and the former (in good Midwestern fashion) by a bison. Breasted clarified the symbolism in an internal memorandum from 1932. “Above the animals,” he explained, “outstanding figures of the Eastern and Western civilizations are shown.”27 For the East, these include two Egyptian pharaohs, the Babylonian king Hammurabi, the Assyrian Ashurnasirpal, and the Persian Darius. The Western figures include Herodotus, Alexander the Great, the Roman emperor Augustus, a crusader, a field archaeologist, and a museum curator examining a vase with a magnifying glass. Columns from Persepolis, a sphinx, and three pyramids represent the art and architecture of the East. The Parthenon, Notre Dame cathedral, and the Nebraska state capitol represent the West. Islam is conspicuously absent.

Like archaeologists who once commonly removed so-called late levels—that is, medieval and modern Islamic remains—without recording them to get to the ancient layers underneath, Breasted elides the Islamic Middle East as though only the West beholds antiquity’s beauty today. Here Moore’s universalist sentiment that art belongs to anyone sensitive enough to grasp it takes on a less sanguine hue: it becomes a criterion for supersession. The political undertones involved in beholding ancient Near Eastern beauty can’t be avoided simply by declaring art apolitical. Breasted boldly avowed his stance above the Oriental Institute’s entrance; visitors to the museum today must consider for themselves how the tympanum will inflect their engagement with the objects inside.

●

How have images from the ancient Near East been appropriated on their native soil? An image of Saddam Hussein published in the state-sponsored Iraqi periodical Alif-Ba on January 8, 1986, echoes Breasted’s tympanum (figure 16). In place of the muscular Western youth accepting the civilization of the East, Saddam receives a palm sapling representing Iraqi heritage from an Assyrian figure. The movement now runs from right to left, in accord with the direction of Arabic writing. In the background, three passages celebrating Saddam as a victorious leader—in cuneiform and medieval and modern Arabic scripts—symbolize the continuity of Iraqi literary culture. Beneath the main figures ancient ships sail down the Tigris beside palatial Islamic architecture and a modern cityscape complete with the silos of power plants. Iraq’s tricolor flag not only adorns the modern apartment blocks but flies atop the medieval domes and the masts of the ancient ships. The palm sapling—in contrast to Breasted’s isolated archaeological fragment—emphasizes local rootedness; it likely also embeds a visual pun on the word nachla, meaning “palm” in Arabic but “inheritance” in Aramaic. Several members of the Iraqi archaeological establishment—beginning with Taha Baqir and Fuʾad Sufar in the 1930s—trained at the University of Chicago. Was the Iraqi artist who created this counterimage to the Oriental Institute tympanum aware of Breasted’s image? I don’t know. But either way, it marks a climax in the nationalist Iraqi claim on the ancient Mesopotamian past.

16. Saddam Hussein receiving Iraqi cultural heritage from a Mesopotamian deity. Alif Ba, January 8, 1968.

It is difficult to reconstruct today what residents around Mosul in the 1840s thought about Layard’s discoveries. Playing to his readership’s prejudices, the Englishman depicted the local Arabs as superstitious children who could mistake the sculpted head of a lamassu for the specter of Nimrud himself. “I was not surprised that the Arabs had been amazed and terrified at this apparition,” he writes. “This gigantic head, blanched with age, thus rising from the bowels of the earth, might well have belonged to one of those fearful beings which are described in the traditions of the country as appearing to mortals, slowly ascending from the regions below.”28 Layard, by contrast, “saw at once that the head must belong to a winged bull or lion.” An illustration in Nineveh and Its Remains depicts the local sheikh Abd-ur-rahman cautiously inspecting the colossal head while his companion throws up his arms in reverent awe (figure 17). Other members of the tribe (and a camel) look on from a safe distance atop the trench. The book’s British readers could contrast their own sophisticated appreciation of ancient objects—as depicted in the Illustrated London News etching of the Nineveh Room (figure 9)—with the superstition of the East.

17. “Discovery of the Gigantic Head.” Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and Its Remains, 1849.

Self-serving caricature notwithstanding, Layard’s account of the locals is accurate in one crucial respect: the diggers he employed most likely did not consider themselves to be unearthing their own heritage. They primarily defined themselves as products of a complicated set of overlapping allegiances to tribal chiefs, religious traditions, local pashas, and the sultan in Istanbul—not as descendants of Nimrud. Those who had claims to the land might have considered the objects lying underground to be their property—but in the impersonal sense of resources they might trade and profit from (like the oil that would soon be discovered beneath the same sands). For Layard’s workers, the bond to old stones that Abbé Grégoire tried to instill among the French did not yet exist.

In the spring of 1870, Ahmed Sakir Bey (1838–1899), subgovernor of the district of Baghdad, embarked on an expedition to survey the conditions for modern steam navigation along the upper reaches of the Euphrates. His report represents an early attempt to cultivate appreciation of ancient ruins among those living in the province of Ottoman Baghdad. While navigating the Euphrates, Ahmed Sakir sent back nine letters and a telegram to be published in the official newspaper Zevra. The letters discussed navigational matters, observations on Bedouin agriculture, appreciation for local town planning, and descriptions of the ancient monuments that dotted the expedition’s course. Resisting pressure to keep the journey on pace, Ahmed Sakir deployed teams to measure the ruins and collect pottery samples. Describing the expansive mound of Salihiyya (ancient Dura Europos), the subgovernor suggested that a proper inspection of the site would be promising since “the Franks” (i.e., European Christians) had not yet excavated there.

What warranted this extensive discussion of ancient ruins in an official provincial gazette? Zevra’s editor imagined a bright future for his native land. He believed that if readers recognized Iraq’s ancient glory they would be motivated to restore the region’s wealth and prosperity after many years of neglect. Ironically, this early attempt to inspire local interest in ancient Iraqi heritage focused on ruins that wouldn’t qualify as Iraqi today. When modern borders were drawn after World War I, the ruins of Dura Europos fell on the Syrian side of Sykes-Picot’s line in the sand.

At the San Remo Conference in 1920, the French and British agreed that the three former Ottoman administrative districts of Basra, Baghdad, and Mosul would be transformed into the “State of Iraq” under British mandate. The territory contained a diverse population: Arabs and Kurds, Sunni and Shiite Muslims, considerable Christian and Jewish populations, and smaller minority groups such as Yazidis. Iraq was to be a constitutional monarchy, but given its ethnic and sectarian schisms it seemed virtually impossible to find a local candidate for king. Eventually, the British found their solution in Faysal bin Hussein (1885–1933), third son of Hussein bin Ali, the Hashemite sharif of Mecca who had proclaimed the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Turks in 1906. Deposed from his brief reign as king of Syria by the French in 1920, Faysal became available to the British. His pedigree, the British believed, would make him acceptable to the citizens of the new Iraq; his pragmatic, pliable character made him acceptable to the British. In his coronation speech, Faysal reminded the “beloved people of Iraq” that “this country was formerly the cradle of civilization.” He prayed for “success in elevating the state of this dear country and this noble nation so that its ancient glory may be restored.”29

“Faysal was very eager to know about ancient monuments,” wrote Gertrude Bell (1868–1926) to her father a month before the coronation.30 The first woman to earn a first-class degree in modern history from Oxford, Bell was an English writer, traveler, archaeologist, and spy who had been working for the British administration in Baghdad as Oriental secretary since 1917. When Faysal arrived from Syria, she became one of his chief advisers and confidantes. Recognizing that Mesopotamian artifacts could help define an Iraqi national identity, the king appointed Bell director of antiquities. He tasked her with formulating an antiquities law and endorsed her ambition to found a National Museum in Baghdad. In 1924 a law was passed that ensured half of all excavated objects would remain in the country. The museum opened two years later.

Not everyone in the new Iraqi administration agreed with the museum’s underlying goals. The prominent Arab nationalist Sati al-Husri (1882–1968) followed his childhood friend Faysal to Iraq in 1920. As Iraq’s first director general of education, he designed an educational program that would strengthen the idea of an Arab nation that spanned the entire region, of which the “Arabness of Iraq” was only a part. Arab history, according to al-Husri, began with the Arab kingdoms of the Yemen, developed under the Ghasam and Nabatean states, and flowered in the Golden Age of Islamic-Arab civilization. Arabs, including those living in Iraq, were taught to emulate warriors like the Prophet’s companion Khalid ibn al-Walid and philosophers like al-Maʾarri, not Sumerian kings. As his fellow Iraqi pan-Arabist ʿAbd al-Rahman al-Bazzaz (1913–1973) would later put it, “An Iraqi must not forget . . . that he is not of the seed of the Babylonians, nor of the Assyrians; he is an Arab, in every sense of Arabism.”31

In this view, Mesopotamian antiquities were more liabilities than inherited treasures. A national consciousness formed around a Mesopotamian past that not all Arabs could embrace would be at odds with the Arab cause. It comes as no surprise that al-Husri and Bell did not see eye to eye. When the director general of education first visited the museum Bell had designed, he was shocked by how little attention it gave to Iraq’s Islamic heritage; he chose not to include museum trips in the Iraqi school curriculum. Years later, after both Bell and Faysal were dead, al-Husri was appointed to Bell’s former post as Iraq’s director of antiquities. Under his leadership, practically all of the department’s funds and energies were redirected toward restoring Islamic monuments and establishing the Museum of Arab Antiquities in 1937.

“For good painting in the Arab World you have to go to Baghdad.”32 So declared the catalogue of a traveling exhibition of contemporary Iraqi art in 1965. Modern art had by then been thriving in Iraq for over a decade, stimulated by Baghdad’s free and tolerant cultural climate. Foremost among Iraqi artists of the day was Jawad Salim (1920–1961). While a student at London’s Slade School of Art, where he studied with Henry Moore, Salim spent long hours with the ancient Mesopotamian sculpture in the British Museum. He acquired a keen sense of how Western cultural and political imperialism worked in his native country and sought artistic means to resist their corrosive effect by giving sharper definition to Iraq’s emerging national aspirations.

“He set out to prove that [Iraqis] could be proud of their ancient heritage and did not need to feel inferior to anyone,” Salim’s widow and fellow artist Lorna Salim recalled. “His aim was to create an artistic language unique to Iraq, built on the great art of its past civilizations—Sumer, Babylon, Assyria and of course Islam, but a language of the 20th century.”33 As director of the sculpture section of Baghdad’s Institute of Fine Arts and cofounder of the Baghdad Modern Art Group, Salim worked to impart this vision to others: an Iraqi art that subsumed religious, ethnic, and sectarian impulses under a single secular national identity. Many of the young painters and sculptors of the Baghdad Modern Art Group—whose manifesto called on artists to mine the riches of a tradition that reached from Sumerian and Assyrian monuments to the magnificent miniatures of Baghdadi painter Yihya al-Wasiti—also served as conservators for the Antiquities Department and National Museum.

Iraqi resentment of Western imperialism culminated in the 1958 revolution that ousted the British-backed Hashemite monarchy and installed a socialist government under the leadership of General Abdul Karim Qasim (1914–1963). From July 1958 until his overthrow in a Baʿathist coup in February 1963, Prime Minister Qasim steered Iraq away from the pan-Arabism that had oriented men like al-Husri. Qasim introduced new national symbols with strong ancient Mesopotamian connotations—an emblem with the Akkadian sun (an eight-pointed star with stylized waves between its points; figure 18) and a new Iraqi flag featuring the (also eight-pointed) star of Ishtar. Evocations of ancient Mesopotamia dominated celebrations marking the first Revolution Day. Floats depicted the invention of writing, Hammurabi’s code of law, and the Ziggurat of Ur. A large portrait of Qasim—flanked by the symbols of the Sumerian god of spring, Dumuzi—led the procession. Playing on the meaning of the god’s name, an inscription in cuneiform read, “Dumu-zi Ab-du-ul Ka-ri-im”—that is, “the good son Abdul Karim [Qasim].”34

18. Bernard Safran, Abdul Karim Kassem, 1959. Tempera on board, 59 × 46.3 cm. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Time magazine. © Estate of Bernard Safran.

To bolster its image, the new regime commissioned Jawad Salim to create a monument celebrating the 1958 revolution. Salim credited ancient Mesopotamian art—notably, the suffering lions of the Nineveh reliefs that had provoked his compassion in the British Museum—with teaching him how to introduce tragedy, and his own artistic voice, into grandiose depictions of state power. “The artist has always been free to express himself, even amid the state art of Assyria,” he told his friend, the poet and critic Jabra Ibrahim Jabra. “The true artist speaks through the drama of the wounded beast.”35 Salim’s Monument of Freedom was unveiled in Tahrir Square, in the center of Baghdad, on the second anniversary of the revolution (figure 19). Its large bronze figures, set against a raised wall designed by the architect Rifat Chadirji, make a double allusion, both to the monumental relief compositions that adorned the palaces of ancient Assyrian kings and to the revolutionary aims of the newly invigorated nation. Harnessing the ancient Mesopotamian past to envision a postcolonial future, the monument expressed “Iraq’s desire for liberty since the dawn of history and the sacrifices made for its realization.”36 Though there was talk of tearing it down after the 2003 American-led invasion, the monument still stands in Baghdad as a testament to that still-unfulfilled desire.

19. Latif Al-Ani, Jawad Salim’s Monument of Freedom in Tahrir Square, Baghdad, Iraq, 1960s. Print from gelatin silver negative. Latif Al-Ani collection. Courtesy of the Arab Image Foundation.

The rise of Saddam Hussein (1937–2006) introduced a new twist to the story of Iraq’s engagement with Mesopotamian antiquity. His Baʿath party was ideologically pan-Arab; the constitution it established for Iraq stated that the country’s principal aim was “to achieve the United Arab State.”37 But in practice Saddam tended toward a policy reminiscent of Stalin’s “socialism in one country.” The traditional Baʿathist approach regarded each of the Arab states as equally illegitimate, because they were arbitrarily created by Western imperialism. In contrast, Saddam cultivated the notion of an Iraq destined by its illustrious history to lead the Arab world. Like Faysal and Qasim before him, only with greater extravagance, Saddam mined Iraq’s ancient past for the sake of present political gain. Baʿathist image-makers churned out scores of images depicting Saddam in one ancient guise or another: Saddam receiving a palm sapling from a Babylonian god (figure 16); a double portrait with Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II on a coin commemorating the Babylon International Festival; a lion hunt scene based on the palace reliefs from Nimrud (figure 20). The Iraqi dictator also inaugurated an annual spring festival in Mosul modeled on a ritual formerly celebrated in ancient Nineveh.7f

20. Saddam Hussein in the guise of an ancient Assyrian king hunting lions. The billboard, now destroyed, once stood near the site of Nineveh.

Saddam’s engagement with the past was not limited to pictorial reworkings and festive revivals. Actual ancient Mesopotamian objects played a more prominent political role in Baʿathist Iraq than ever before. “The stele of Hammurabi awaits impatiently in the Louvre and the library of Ashurbanipal is in the British Museum,” an article in Al-Thawra lamented. “Their inability to return to the homeland from which they emerged is a cultural calamity and a major crime.”38 The official Baʿath newspaper announced Iraq’s determination “to restore the treasures which are the symbol of the first and greatest civilizations in human history.” That the Iraqi demands for repatriation proved futile is beside the point; even unsuccessful demands roused the national spirit. The Baʿath also earmarked extensive resources for new excavation and reconstruction.

By the mid-1970s, Saddam’s regime had built new archaeological museums throughout the country and renovated older ones, including the museum in Mosul. Saddam also spearheaded a massive construction project, a loose interpretation of ancient Babylon that blurred the line between restoration and Las Vegas–style simulacrum, with bricks bearing the inscription “This was built by Saddam, son of Nebuchadnezzar, to glorify Iraq.” As pilgrimage destinations for Iraqi schoolchildren and visiting dignitaries, these museums and reconstructed archaeological sites played a central role in Baʿathist educational and diplomatic endeavors.

So completely did Saddam succeed in making the antique past his own that those who grew up under his regime sometimes find it difficult to distinguish between ancient and modern. I once asked an Iraqi grocery store owner living in Chicago about recent events in and around Mosul. He had been bused to Nineveh and Babylon as a child but now dismissed the destruction of antiquities as no great loss. “That stuff’s all just Saddamist propaganda,” he said.

On April 9, 2003, three weeks into the American-led invasion of Iraq and a day before the National Museum was looted, a crowd gathered around a statue of Saddam Hussein in Baghdad’s Firdaws Square (figure 21). A handful of Iraqis, including the world-class wrestler and weightlifter Kadhem Sharif, took turns wielding a sledgehammer against its base. “The media is watching the Iraqis trying to topple this icon of Saddam Hussein,” US Marine Corps officer Bryan McCoy later recalled, but the sledgehammer alone wasn’t up to the task. “Let’s give them a hand,” McCoy decided, and ordered his men to use an M-88 Hercules—a tow truck for tanks equipped with a crane—to finish the job.39

21. Front page of the New York Times, April 10, 2003.

Opinion remains divided on whether the event was spontaneous or entirely staged by the Americans. Either way, what took place at Firdaws Square was neither unique (similar removals of Saddam’s image had been taking place throughout the country) nor particularly impressive (the crowd consisted of, at most, a few hundred people). What set Firdaws Square apart, however, was the media coverage. The toppling, which lasted about two hours, was shown live on cable news networks around the world, and its climactic moment was replayed throughout the course of the day. Newspaper and magazine covers followed with photographs of the event. In his voiceover commentary to the video footage, one reporter at Fox News said, “You have to think that there are going to be some minds changed as a result of these incredible pictures.”40 Nobody complained about the destruction of Iraqi cultural heritage.

The invasion of Iraq set off a bloodletting that has eviscerated local traditions at least as old as any Assyrian statue. In The Corpse Washer, Baghdad-born novelist Sinan Antoon (b. 1967) mourns the disintegration of his country. “History is a struggle of statues and monuments,” Jawad, the novel’s protagonist, imagines telling his deceased father. “Even Saddam’s huge statue in Firdaws Square was brought down right after your death. I thought I would be happy since I detested him so much, but I felt robbed of the happiness. That was not the end I had imagined.”41 Taught in school that art originated in ancient Iraq, Jawad dreams of becoming an artist like his namesake Jawad Salim. Circumstances compel him instead to succeed his father as a ritual corpse washer in the local Shiite mghaysil. Unprecedented sectarian violence following the invasion yields a never-ending flow of corpses. The ambitions of Salim’s Baghdad Modern Art Group now seem fantastical and give way, in this new Iraq where “even the statues are too terrified to sleep at night lest they wake up as ruins,” to the modest yet noble art of the corpse washer.

And yet, a new generation of Iraqi visual artists has emerged to reimagine their country. Sundus Abdul Hadi (b. 1984) was raised outside Iraq in a home filled with books on ancient Mesopotamia and modern Arab art. These proved essential resources as she sought to define herself as an Iraqi artist in the diaspora. In her ongoing series The New Sumerians, Abdul Hadi uses digital imaging to explore continuities between the carved female face of the Mask of Warka (3100 BCE) and her own face. Ancestor, a digital collage from 2019, similarly grapples with the links between contemporary Iraq and the country’s ancient past. The work reproduces the famed “Queen of the Night” terra-cotta relief of a naked female deity (now in the British Museum) above three depictions of a devoutly dressed Muslim woman in mourning (figure 22). Does the juxtaposition make the Muslim woman into an idolater? As I read the piece, the tension gives way to a rapport between these two Iraqi women. If the future Iraq is to flourish, it won’t emerge from a call to demolish the state of idols.

22. Sundus Abdul Hadi, Ancestor, 2019. Digital collage. Image courtesy of the artist.

Like the “Queen of the Night” terra-cotta, Abdul Hadi currently resides outside Iraq. In Baghdad, other young Iraqis have been reconnecting to their country’s creative traditions. In October 2019, as thousands gathered in front of Jawad Salim’s Monument of Freedom to protest their government’s failings and military forces responded with tear gas and live ammunition, local artists drew on an ancient heritage to make sense of the struggle. A digital reworking of Salim’s monument, itself based on ancient Assyrian reliefs, showed silhouette figures dodging a tear-gas canister and broadcasting live video from a smartphone. As casualties mounted, tuk-tuk drivers and their humble three-wheeled vehicles played an essential role, shuttling the wounded away from danger. To celebrate these unexpected heroes, Wady Alrafdyn posted an image on Facebook of a tuk-tuk transformed into a lamassu, a protective deity from Iraq’s ancient past. The image went viral.

●

From Paul-Émile Botta and Austen Henry Layard in the mid-nineteenth century to the Iraqi shopkeeper in 2010s Chicago, we all view ancient Mesopotamian objects not “objectively” but as mediated by particular impulses and conditions: imperial prestige, Enlightenment universalism, artistic modernism, nationalist self-assertion, or tyrannical oppression. Even scholars who try to be objective necessarily transform ancient objects into bearers of historical evidence whose value depends on modern commitments to the progress of knowledge. Precisely because antiquities are intimately tied to who we imagine ourselves to be, their position in the modern world remains inextricably political. Like any other political image, they make demands on their viewers. One need not endorse the destruction of antiquities to recognize how our museums enshrine them with particular meanings. Rather than turn a deaf ear when those meanings ring false, we can try to attune ourselves to their imperfections and acknowledge the ambiguities they entail.

Since 2007, Chicago-based artist Michael Rakowitz (b. 1973) has been exploring these ambiguities through his ongoing project The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist. The series re-creates looted or destroyed Mesopotamian artifacts using what Rakowitz calls “the waste”—colorful packaging from Middle Eastern food products and newspapers found in Chicago’s Arabic neighborhoods.42 His use of this “detritus . . . the discarded moments of culture” alludes to the careless way antiquities have been treated but also attests to a thriving Arabic community within the United States—even if, as with his mother’s family, who fled Baghdad in 1946, Arabs have not always come entirely by choice. “The more I read about the [2003 Iraq Museum] looting,” Rakowitz explained in an interview, “the more complicated it became to cry about missing artifacts: for Iraqis, looting the museum and selling an artifact on the black market was a way to get out of the country.”

Rakowitz’s sculptures expose a host of tensions—between antiquity and modernity, homeland and diaspora, consumption and preservation, art and life. He took particular pleasure when the British Museum bought a group of his re-created artifacts, which were to be displayed alongside original artifacts from its own collection: “I’m interested in what kind of tension will be achieved between these two things.” While attending a museum may be a “civilizing ritual,” as the title of Carol Duncan’s book puts it, Rakowitz’s work helps us confront civilization’s discontents without tearing down the entire edifice.

Rakowitz’s sculptures were on display at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World in New York the day ISIS released its Mosul Museum video. Though it may be jarring to contemplate, that video constitutes a further installment in the history I have sketched here.8f Through their destructive consumption of Near Eastern antiquities, ISIS has produced new images that transform the way we see those objects, imbuing them with new meanings. Nobody who has viewed the Mosul Museum video can experience ancient Mesopotamian sculpture in quite the same way again. If avant-garde art is meant to disrupt conventional ways of seeing the world, then the Islamic State’s video is “good work.” Indeed, the Colombian cartoonist Léon captures this aspect of ISIS by depicting one of its militants as an abstract artist exhibiting recent work in blood on canvas. In contrast to Patrick Chappatte’s boorish museumgoers (figure 4), Léon’s Daesh fighter does not just consume art—he creates it.

Léon’s cartoon was selected from more than a thousand submissions to the 2015 International Daesh Cartoon & Caricature Contest to be displayed at Tehran’s Palestine Museum of Contemporary Art. Other winning cartoons also emphasized Islamic State image-making. At least two showed a jihadist holding a weapon to the throat of a hostage. In Indian cartoonist Vivek Menon’s version, a clapperboard like those used on movie sets marks the scene as a performance staged for the camera; in another, the ISIS member holds a smartphone in his free hand to take a selfie. In Iranian cartoonist Hamed Bazrafkan’s submission, two menacing militants stand side by side, one armed with a scimitar and the other with a bloodstained Facebook logo (figure 24). “When you find yourself surrounded by hell,” Jordanian cartoonist Jehad Awartani said in an interview for Newsweek, “you have no other option than to fight it with all the arms at your disposal.”43 Among Awartani’s many cartoons satirizing the Islamic State is an image showing a black-clad jihadist, hands covered in blood, accepting an Oscar for his artistic achievements. (As it happens, Natalie Portman once told the Hollywood Reporter that she hid her own Oscar when she was teaching her son about Abraham’s refusal to worship idols.)

23. Michael Rakowitz, The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist, 2018. Fourth Plinth Trafalgar Square. Photo: Aaron Tugendhaft.

24. Hamed Bazrafkan, cartoon of Islamic State fighters, 2015.

The ISIS media obsession caricatured in these cartoons is equally at play in the destruction of antiquities. The hammer wielders are attentive videographers. The video from the Mosul Museum does more than merely record the destruction of images, and its ISIS “stars” did more than simply smash sculptures. They filmed themselves doing so, edited the video, set some sequences in slow motion and sped up others, added a soundtrack and screen titles, and uploaded the finished work onto the internet. This attention to form serves to mediate our experience of ancient Mesopotamian sculpture in new ways. But that is not all. Once recognized as more than just the record of a destructive act, the video itself becomes a kind of replacement image. The destruction of images becomes part of image production.