This outdoor shower drains to irrigate nearby plants.

In this chapter I’ll summarize a handful of additional types of greywater systems, some of which are simple enough to build yourself. Others are more complex and require professional assistance.

Greywater systems that aren’t connected to a house, such as those drawing from an outdoor sink or shower, can be extremely simple and functional. Some systems have specialized functions, such as ecological disposal of greywater or supplying year-long irrigation in freezing climates by incorporating an indoor greenhouse. If you’re planning to build a home and want a more advanced system, there are high-end systems that collect, filter, and distribute the water and offer remote monitoring capability.

Have an outdoor shower, sink, drinking fountain, or washing machine? They’re perfect opportunities to capture and reuse greywater! Greywater sources located outside make for a simple system, just directing water to nearby plantings. I’ll describe two common systems here, and you can adapt the ideas for any outdoor water source.

This outdoor shower drains to irrigate nearby plants.

Simple and easy to install, an outdoor shower is a perfect way to irrigate nearby plants. Imagine a cool shower on a hot day, water flowing over your body and draining directly to nearby plants that adorn the shower structure. When you build the floor of the shower, use flagstone or a small concrete pad and slope it toward a well-mulched planted area adjacent to the shower — no need for a drain or plumbing. For elevated floors, slope the soil below and cover it with rock to move water toward the plants. If you don’t want to plumb water lines to the shower, use a food-grade garden hose to supply the water. For a warm shower, use coils of black irrigation tubing to heat the water passively, through sun exposure.

This outdoor shower directly irrigates the landscape via greywater runoff from its stone floor.

Every community garden or outdoor seating area needs a sink for washing garden produce or dirty hands and for supplying drinking water. Greywater from the sink can irrigate nearby plants via a small branched drain system. Supplying the sink from an existing spigot means the fixture isn’t permanently connected to a building’s plumbing system and therefore won’t technically produce “greywater” or be illegal without a permit . . . in most cases; the legality of this is a “gray” area. Obviously it’s not illegal to wash your hands using a garden hose and let the water run on the ground, but if you build a small structure and install a sink using the garden hose, will that produce greywater and require a permit? This legal ambiguity makes these systems attractive in schools or community centers where permitting greywater systems may be particularly challenging.

There are several greywater systems designed for use in new construction (or major remodels), when you are able to capture and reuse all greywater sources in the home. Most of these systems are relatively new, and relatively expensive, but they allow a home to recycle all its greywater and employ an automatic drip irrigation system capable of irrigating any type of landscape. Some of these systems treat the water for indoor toilet flushing as well. Even with filtration and treatment of greywater, these systems do not remove salts or boron, which could harm plants if they build up in the soil, so it’s still important to use plant-friendly products in the home. In terms of cost, the total installation cost is typically two to four times more than the cost of the system itself; it takes a lot of time and effort to get permits and install these complex systems. They all employ self-cleaning filters but will still require annual maintenance. Below, I’ll discuss three types of systems currently available.

If the cost or complexity of these systems seem too much for your project, consider the GreyFlow PS (see here), which is also suitable for whole-house greywater. It costs less than the other whole-house systems, and it doesn’t have a potable water connection, which makes permitting easier. The GreyFlow system has a self-cleaning filter, drip irrigation, and multiple irrigation zones (without need for a controller).

This Home Water and Energy Recycling System is a fully automated whole-home option that integrates into the plumbing infrastructure of the house. It collects, filters, and disinfects household greywater for reuse, either for irrigation or toilet flushing. It is the first residential greywater system to receive NSF-350 certification for greywater, which in California allows the treated water to be used for toilets and spray irrigation. Additionally, the system can capture heat from greywater using heat pump technology.

Nexus estimates that its system can reduce home water consumption by 34% and reduce energy needed to heat water by 75%. In new homes, the total cost of installing the system is less than $10,000, with an additional $3,000 to add the energy recycling option. Annual filter and UV bulb replacement costs are $150.

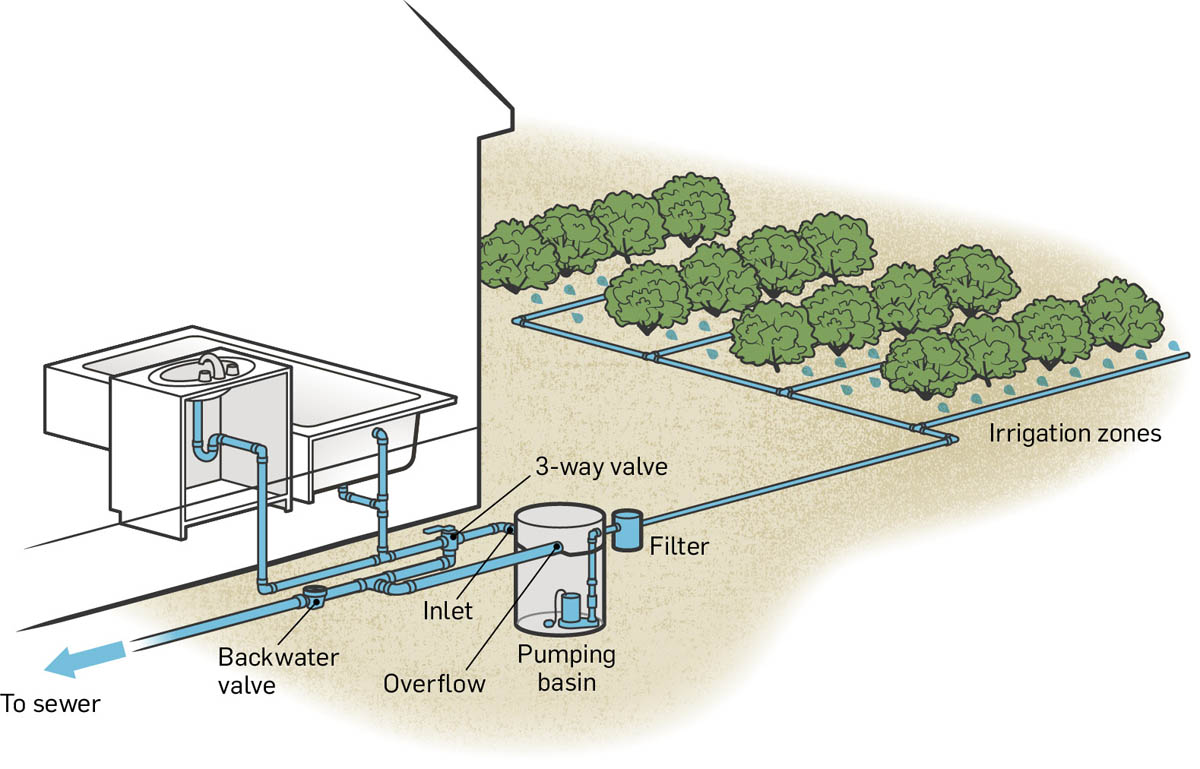

This automatic irrigation system uses greywater, rainwater, condensate water, or other non-potable on-site water. (Note that this automatic system is the new focus for Australian (now US resident) greywater designer Paul James. His previous IrriGRAY system used a manually cleaned filter and is now discontinued.) The new IrriGRAY consists of a small sump basin, which temporarily collects greywater and pumps it out through a self-cleaning filter. The filter is automatically backflushed with pressurized, potable water for cleaning (requiring backflow prevention) and directed to the irrigation system. The irrigation lines are also flushed with potable water to remove buildup in the lines.

IrriGRAY uses a multi-zoned smart irrigation system, which can be controlled and monitored remotely (on your phone, computer, or tablet) and will bring in makeup water if there isn’t enough greywater to complete the irrigation cycle. The monitoring system notifies the owner if there are any problems, including leaks. IrriGray systems were installed in a subdivision in San Angelo, Texas, and used in both residential and commercial applications. The whole system, including irrigation parts, costs $5,000 to $7,000 for a typical single-family home.

The ReWater system has been available for more than 20 years, far longer than any other greywater system currently on the market. It consists of a tank, a pump, a sand filter (with automatic backflush), and a sophisticated irrigation controller that sends greywater to specialized subsurface emitters. The filter is backflushed with pressurized potable water (with cross-connection protection), and the controller brings in makeup water at the end of the day if there isn’t enough greywater to complete the irrigation program. The whole system, including irrigation components, costs around $6,000 to $10,000 for a residential landscape. ReWater Systems are typically installed in new-construction residential and commercial buildings.

Filtered greywater system

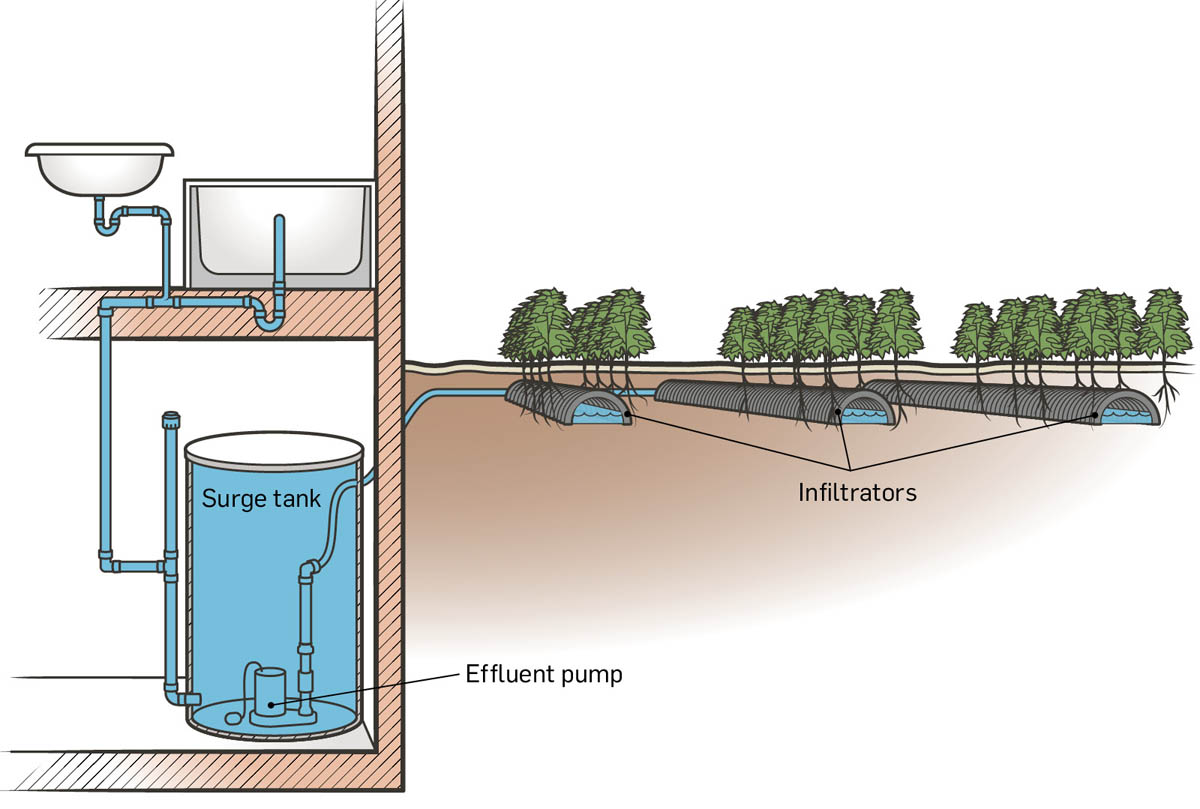

Instead of mulch basins, subsoil systems use infiltration chambers to soak greywater into the ground. Greywater flows to belowground chambers designed to fill up with an inch or two of water, then soaks into the ground. Chambers are sized based upon estimated flows: larger chambers accommodate more water flowing into them. Subsoil systems are used where subsurface irrigation is needed and where a lot of water must infiltrate into a small area. They’re also incorporated into some types of greywater greenhouses (see Greywater for Greenhouses). These systems often are installed to comply with local regulations and are commonly used in combination with composting toilets to replace the need for a septic system (for an example, see Sewerless Homes).

The cost of a professionally installed whole-house system ranges from $6,000 to $10,000 to replace a septic system. DIY installations using gravity flow to subsoil half-barrels may cost $200 to $300 in materials. There are a variety of materials available for subsurface irrigation:

Infiltrators. These are designed for septic systems. Use the shortest (in height) infiltrator possible so greywater will soak higher in the soil profile where there is more biological activity to process the water. The company Infiltrator Systems makes one that’s 8" tall × 48" long × 34" wide (see Resources).

Box trough. Build your own infiltrators by creating a wooden box trough — essentially a rectangular box with no bottom. This allows you to customize the size and depth of the infiltrators to fit your site. Include an access hatch on top that opens for inspection and maintenance.

Half-barrels. Use salvaged plastic barrels, usually 30-gallon-size, and cut them in half. Drill an entry hole on top and cut out an inspection hatch.

Dosing tank. Professionally installed systems often use a dosing tank, which collects greywater and sends it all out to the infiltration area a few times a day. This allows the soil to re-oxygenate between doses. Dosing tanks can be pumped or work by gravity.

Subsoil infiltration system

John Hanson and his Maryland-based company NutriCycle Systems install whole-house systems (greywater with composting toilets) as an alternative to a septic or sewer system.

He also designs greywater systems used worldwide for the composting toilet company Clivus Multrum. His systems are maintenance-free: he has 10-year-old systems that require no maintenance whatsoever.

John’s greywater systems satisfy health department concerns for approving no-septic homes or businesses (all sites must meet the percolation requirements of a conventional system for regulatory approval of an alternative one — this prevents development on a site unsuitable for a septic system). They are designed to prevent groundwater pollution and to recycle nutrients; they are not specifically for irrigation.

Greywater is delivered to subsoil infiltrators either with a pump or gravity dosing tank (non-electric). John uses Orenco’s automatic distributing valve to create multiple zones in the pumped systems. His systems have no filters, and all organic matter decomposes in the soil. In freezing climates, pipes are buried deeper and never have standing water in the pipes. In most places, he infiltrates 8 inches deep, though goes deeper (12 to 16 inches) in areas with extreme weather conditions.

The cost for a residential greywater system ranges between $6,000 and $10,000. A Clivus Multrum composting toilet is $6,000 to $10,000. The total cost is between $15,000 and $20,000 — about the same as a new septic system.

John installed a NutriCycle system at his home in 1980, with two waterless toilets and one foam flush toilet (3 ounces per flush) connected to a Clivus Multrum toilet. The compost is removed once a year and used on the property. Household greywater is absorbed by a beautiful flower bed. You can visit John’s website (see Resources) to see these systems in action and to contact him for an appointment.

John’s advice to us: “Do it! Get involved, do something that is not polluting.” He also advises public and commercial facilities to install these systems, since they are much cheaper than traditional on-site systems.

Greywater can be used to irrigate greenhouse plants. Common in cold climates, greenhouses extend the growing season and maximize the irrigation potential of greywater. There are two categories of greenhouses irrigated with greywater: standalone, outdoor greenhouses and integrated, indoor greenhouses that are attached to the house.

Standalone, outdoor greenhouses can be constructed anytime and the plants can be irrigated with a pumped greywater system. You can irrigate larger plants with a simple pumped system (no filter) or, to spread out the water to irrigate numerous small plants, include a filter for a drip irrigation system. Always cover the soil with mulch (either woodchips or straw) to catch particles in the greywater and prevent clogging of the soil. See Building a Pumped System for help with system design and installation.

In some situations, a laundry-to-landscape system can also irrigate greenhouse plants. The washing machine must be close enough to the greenhouse (within 50 feet in a flat yard, or farther in a downward-sloping yard), and the plants must be either in the ground, in small raised beds, or in very large pots (wine-barrel sized). See chapter 8 for more information.

The cost to irrigate an existing outdoor greenhouse is the same as with a standard L2L, pumped, or filtered greywater system.

Integrated, indoor greenhouses irrigated with greywater are typically installed during new construction or a major remodel. Earthships, passive-solar houses made from natural and recycled materials, incorporate greywater greenhouses that grow beautiful plants and also filter the greywater to be reused to flush toilets.

In cold climates an indoor greenhouse requires proper siting to maximize sun exposure and minimize the need for supplemental heating. The cost for a professionally installed indoor greenhouse and greywater system may range between $10,000 and $30,000, on par with putting a small addition onto a home. The cost for the greywater system represents a small portion of the total cost for the greenhouse.

Bar-T Mountainside camp in Urbana, Maryland once had approval to put in a one-million-dollar septic system for their capacity of 350 daily campers. Instead, they installed a greywater and composting toilet system, saving more than $500,000 (even with an overdesigned greywater system and the cost of building a new basement for the compost chambers). Since the camped open in 2006 the system has helped to teach thousands of children about nutrient recycling.

Indoor greywater greenhouse

Carl and Sara Warren run a residential design-build contracting company in eastern Massachusetts. When they decided to convert their barn into an office, they found out the septic system wasn’t large enough for increased flows. They decided to install an alternative, zero-discharge system.

Composting toilets are an accepted technology and not a problem for permitting in their state. The Warrens chose a Phoenix composting toilet (Carl says they’ve had absolutely no problems with it and feel sorry for people who have to put up with the smell, water use, and cleaning hassles of a flush toilet). Getting a permit for a greywater system was harder and required approval from the state department of environmental protection; their system is monitored as a pilot project.

The system begins with water-efficient fixtures (washing machine, shower, and bathroom and kitchen sinks) draining to a surge tank. Greywater flows by gravity to 3⁄4-inch PVC pipes spread throughout greenhouse planters. The planters are insulated and lined with an impermeable rubber membrane (required by the state department of environmental protection) and filled with a combination of peat moss, vermiculite, loam, and compost. Carl was surprised at how tolerant the plants are, and they experimented to find ones that thrived and evapotranspired the most water; bananas won. The beds transpire 50 gallons a day, even in the winter.

Maintenance includes trimming plants, annual cleaning of the grease interceptor (under the kitchen sink), biannual cleaning of the lint collector, and regular cleaning of strainers in the sink and shower drains.

Carl reflects that the greatest drawback to his system is the heating requirement. Because the greenhouse had to fit into an existing building, he wasn’t able to orient it for passive heating. With proper orientation and an automatic insulating shutter system, he believes it could be 100 percent passively heated.

Cost:

A constructed wetland is a watertight planter, typically lined with a pond liner, filled with gravel and planted with wetland plants. The plants, gravel, and microbes around the roots filter greywater and remove nutrients. More common in wastewater treatment plants and commercial-scale greywater than in backyard systems, constructed wetlands ecologically “dispose” of the water, instead of efficiently reusing it. Constructed wetlands are well suited for homes that produce more greywater than is needed in the landscape. And, importantly, in places without sewer treatment, constructed wetland systems treat household greywater to prevent water pollution.

Anyone researching constructed wetland systems will read about the importance of retention time: how long each water molecule remains in the system. In a municipal-scale system that treats wastewater for discharge into a waterway, it’s critical to have sufficient retention time to ensure all the nutrients are removed from the water. In a backyard wetland, retention time is not important: the nutrients in greywater will fertilize the garden, and the water won’t be discharged into a waterway. Backyard wetland system designers should focus on clogging prevention and surge capacity rather than retention time.

Backyard constructed wetlands typically are used for ecological disposal of greywater in climates with ample rainfall or places without sewer treatment. With my own system, I learned that I could easily grow the wetland plants I love without the drawbacks of flowing all the greywater through the wetland prior to the irrigation system by directing a portion of greywater to irrigate the wetland and using the rest for other plants. Costs for systems range from a few hundred dollars for a small do-it-yourself installation (or less if you use salvaged materials) to many thousands of dollars for a large, professionally installed system.

Here are a few things to keep in mind when designing a wetland system:

Sand filters are used in both drinking water and wastewater treatment, and often there is confusion between the two processes. Slow sand filters clean water for drinking. Small quantities of non-potable water slowly drain through sand, where microbes remove pathogens and contaminates from the water. It is a biological process. Rapid sand filters treat wastewater. Greywater, for example, is pumped rapidly through a sand filter where the hair, lint, and gunk stick in the sand; filtered greywater comes out (not drinking-water quality!). Filtration is adequate for drip irrigation systems without clogging the small emitters. It is a physical process.

Rapid sand filters, like those used in swimming pool systems, are employed in some high-end greywater systems, like the ReWater System (see here). These systems use pumps, tanks, controllers, and drip irrigation and are much more expensive than other types. In general, a sand-filter-to-drip-irrigation system is installed in whole-house greywater systems, in high-end residential, multi-family, and commercial-scale new construction.

In a typical rapid-sand-filter system all greywater from the house is plumbed to a surge tank where the greywater is stored temporarily. Inside the tank an effluent pump, turned on by an irrigation controller, pumps greywater through the sand filter, then out to the landscape. The hair, lint, and other particles are filtered out by the sand, and greywater is distributed to plants via greywater-compatible irrigation tubing (made for greywater or septic effluent). If there is not enough greywater to complete the irrigation cycle, the system automatically supplements with domestic water. The controller automatically cleans the sand filter by pumping fresh water backwards through the sand, removing the lint, hair, and particles to the sewer. The cost of this type of system ranges from $10,000 to $30,000.

A high-tech greywater system not only irrigates the plants, but it also knows how much water your home is using and reusing. All info is uploaded to a web page, where you can monitor the real-time water use (daily greywater flow and municipal use), view charts of monthly usage, and get email alerts for pipe breaks or leaks (this could save a lot of water!).

John Russell, owner of Water Sprout (see Resources), a design-build company specializing in greywater and rainwater systems, uses technology to automate and monitor his systems. John has fine-tuned his system over the past 10 years, using various filtering methods, all self-cleaning and operating with controls and makeup water.

He recently installed a system in a LEED-certified new home in Kentfield, California, collecting all household greywater (except kitchen sinks) for landscape irrigation and rainwater for reuse in toilets and laundry. Greywater flows into a 300-gallon underground tank for temporary storage. The system pumps filtered greywater to the landscape drip irrigation. The filters are automatically backflushed once a week to reduce system maintenance to once a year.

John has more experience with greywater filters than anyone I know. His recommendation to those considering filters:

“Filtering greywater appropriately is probably the most challenging aspect of utilizing greywater. When purchasing systems it’s important to understand how often the filters need to be maintained, and try to choose systems that require minimal maintenance. Who wants to spend their weekend cleaning greywater filters?”

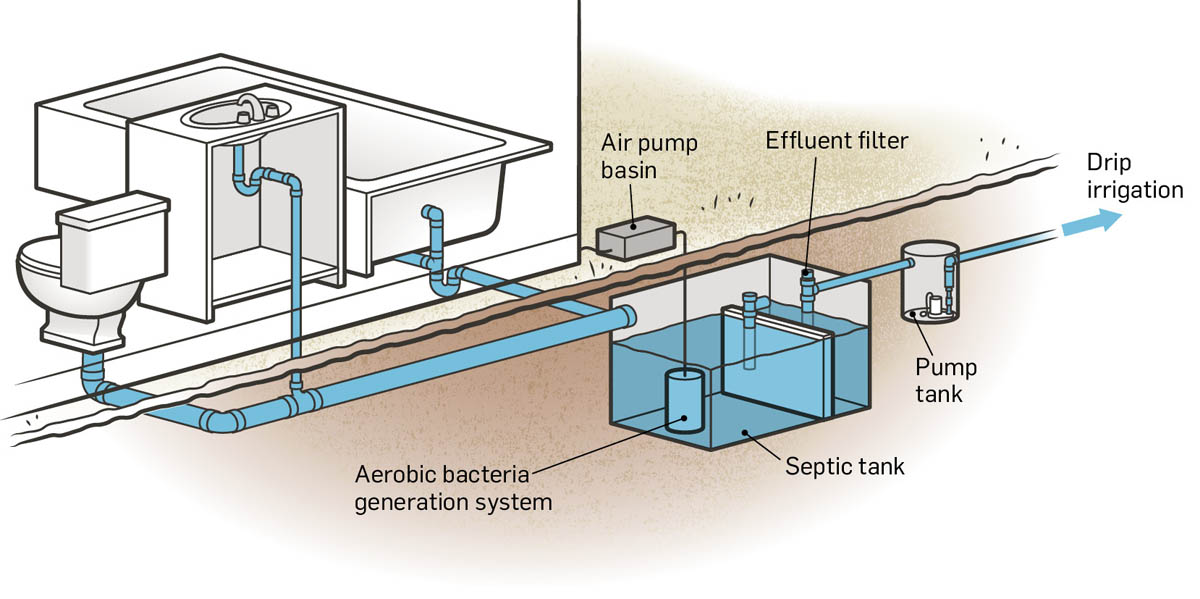

Homes with a septic tank system may be able to reuse the septic effluent water for irrigation, with just a few alterations to the conventional system. A conventional septic system consists of a septic tank and a drain field, also called a leach field. Wastewater from the home flows into the buried septic tank. Solids in the water sink to the bottom and are decomposed by anaerobic bacteria while the liquids, called septic effluent, flow out the other end of the tank and into the leach field. Leach lines are made from large, perforated pipe buried in gravel-filled trenches. The effluent flows into the leach lines and out through the holes, and soaks down into the surrounding soil.

Homes with a septic system can adapt the tank to reuse all the effluent without separating out greywater flows. These systems treat septic effluent to irrigation quality and often are used when a traditional septic leach field is not suitable (for example, if the land is rocky and offers poor infiltration) or to capture irrigation water. Some states allow this treated effluent to be reused for irrigation. Most systems add oxygen to the septic tank to feed aerobic bacteria that clean the effluent to a higher quality. Companies such as Orenco make whole systems designed for septic effluent reuse. Other products, like the SludgeHammer Aerobic Bacteria Generator (see Resources), are installed inside an existing septic tank. Reed-bed constructed wetlands are also used to treat the septic effluent for irrigation.

In terms of cost, if the local authority allows the septic leach field to be reduced or eliminated, the cost is comparable to that of a traditional system. By contrast, regulatory requirements could make the system more expensive than a traditional one if they require a conventional leach field system in addition. Typical costs for professional installation are $7,000 to $20,000. Materials only — for homeowner installations — run around $4,000.

Casa Dominguez provides affordable housing to 70 families and transition-age youth exiting the foster care system as well as a child-care center and health clinic. Greywater from the laundry irrigates a beautiful courtyard and the perimeter landscaping. The “sand-filter-to-drip-irrigation” system was made by the company ReWater. Casa Dominguez is LEED Platinum certified, the highest level of certification from the U.S. Green Building Council, and obtained the first permit for a multi-family building to reuse greywater in Los Angeles County.

Jeremiah’s beautiful yard

Jeremiah Kidd and his family reuse every last drop of water leaving the house in their landscape. Jeremiah is the owner of San Isidro Permaculture (see Resources), an ecological landscaping company specializing in greywater, rainwater, and edible landscapes in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

In his own home, Jeremiah decided to install a blackwater recycling system instead of the greywater systems he often installs. Why? The only growing areas on his land were uphill from the house, he’d have to pump the water with any reuse system, and the blackwater system gave him more options and control over the irrigation.

His home is plumbed conventionally; water from the shower, sinks, washing machine, and toilet flow together into the septic tank. The blackwater irrigation system begins in the second chamber of the tank with a SludgeHammer system (see Resources), pumping oxygen into the chamber to feed aerobic bacteria that clean the water. The treated septic effluent overflows into a pump tank where it’s pumped out through a filter to subsurface drip irrigation designed especially for wastewater, using Netafim purple tubing for the irrigation lines. (New Mexico requires that tubing be buried 6 inches below grade.) Soil microbes further clean the water, and plants benefit from the nutrients.

Jeremiah’s system has four zones: two zones of native plants, providing habitat for birds and beneficial insects; and two zones of food production, food forest, and fruit trees. He concentrates the water in those zones during the growing season.

“I think of this as a fertilizing system. It’s not enough water for the entire landscape, but it reuses all the water from the home and sends nutrients to the plants,” says Jeremiah.

They are a water-conscious family, using less than 20 gallons per person per day. With a large landscape (they garden around 10,000 square feet) that amount of water covers only about one-third of the need. The other two-thirds is irrigated with rainwater and, occasionally, well water.

Jeremiah built the system himself (as well as the house). He spent around $4,000 for the parts. He was allowed to reduce his leach field significantly, from around 30 infiltrators down to 8. This is an accepted technology in New Mexico, and there were no problems with getting a permit. Maintenance is minimal: twice a year he cleans filters and once a year adds bacteria to the tank.

“I think of this as a fertilizing system. It’s not enough water for the entire landscape, but it reuses all the water from the home and sends nutrients to the plants.”

Treated blackwater irrigates and fertilizes the landscape.