Greywater can irrigate a variety of plant types.

Plants are at the heart of greywater irrigation systems.

To get the best results and save the most water, you’ll need to choose appropriate plants to irrigate as well as calculate how much water they need. This chapter will teach these important details so you can best design the irrigation portion of your system. I’ll teach you a few methods to calculate plant water requirements so you can adequately irrigate your plants and maximize your water savings. Last, I’ll discuss what soaps and products are best to use in a greywater irrigation system to ensure the water is a good quality for your plants.

A well-designed system finds a balance between the amount of greywater available and the irrigation needs of the plants. Since the amount of greywater and plant water needs both fluctuate, your design goal is to find an optimal match: irrigate as many plants as possible while keeping them healthy. During rainy times when your plants don’t need irrigation, either turn off the greywater system or, in well-draining soils, keep it on. The amount of greywater going through a system is minuscule compared to a rainstorm.

If you have an existing landscape, follow these steps:

Greywater can irrigate a variety of plant types.

If water savings is your goal, you must replace potable water irrigation in your landscape with greywater irrigation. If you have an existing irrigation system, try to replace an entire zone with greywater and then shut off the zone. If you can’t replace a zone, be sure to shut off any emitters or spray heads that reach the greywater-irrigated area.

Installing a greywater system is a great time to assess your entire landscape. If you’re designing a new landscape or redesigning an existing one, be sure to design the garden so that plants requiring frequent irrigation are near a greywater or rainwater source and, once established, the remaining plants thrive without irrigation. Implementing other water-wise landscaping techniques, such as choosing plants adapted to your climate (without supplemental irrigation), using mulch to prevent evaporation, and grouping plants with similar water needs (called hydrozoning), facilitates water-efficient irrigation. If you’ll be irrigating some of your landscape with potable water, be sure to use the most efficient type of irrigation system you can; there are both low- and high-tech options (see Resources).

Larger plants are better suited for greywater irrigation than smaller ones. A tree or bush with a large root area can withstand fluctuation in water much better than small plants can. Large plants also need more water than small ones, making it easier to distribute more greywater to fewer plants. As you look at your landscape, identify the easiest plants to irrigate. Most houses exhaust their greywater supply before the entire landscape is irrigated. If you end up with extra greywater, consider planting something new.

Some landscape areas aren’t well suited for greywater irrigation, such as lawns or areas full of small plants (although high-tech systems can irrigate these types of plants; see Greywater Goes High-Tech for more info). Consider these techniques to improve a landscape for simple greywater irrigation:

Note: If you’re wondering whether hot water from a shower or washer may harm the plants, don’t worry; it won’t. By the time hot water flows down the pipes, soaks through the mulch, and reaches the roots of plants it’s not hot anymore.

These are the easiest plants to irrigate with greywater:

Trees. Fruit trees (or any trees) adapted to your local climate thrive with greywater irrigation.

This apple tree thrives with greywater irrigation.

Bushes and shrubs. Bushes and shrubs suited to your region are easy to irrigate with greywater. Consider fruiting varieties, or find ones that create bird and beneficial insect habitat.

Vines. Edible vines, like passion fruit or kiwi, are attractive and produce fruit.

Passionflower vines produce beautiful flowers, provide delicious fruit, and grow over a large area.

Larger perennials. Perennial vegetables, which produce year after year without needing replanting, are a productive addition to any landscape (see Resources for ideas). Flowering plants provide bird and butterfly habitat.

Large annuals. Large annual plants, both edible and non-edible, can be irrigated with an L2L or pumped system; for example, tomatoes, corn, zinnias, squash. (Remember, you can safely irrigate food crops so long as the edible portion is above the ground and greywater doesn’t touch it.)

Smaller plants growing closely together can be irrigated in the middle of the planting area, so their roots share the water. Or, create distribution channels to move greywater toward the plants, like a “sun” mulch basin.

“Sun” mulch basin. Greywater flows out from center of basin toward smaller plants.

Plants for Ecological Disposal (Wetland Plants). If you have ample irrigation water and don’t need to be water-conscious in your landscape, consider growing water-loving wetland plants; they thrive with frequent and plentiful greywater irrigation. Or, if a lush wetland is in your garden design, dedicate some of your greywater for it. Note: It’s a lot easier to direct a portion of the greywater to irrigate a wetland than to flow all the greywater through it before an irrigation system. (Wetlands are used to process greywater in places without irrigation need or sewer/septic options, and these designs flow all greywater through the wetland.) Backyard wetlands are prone to clogging, which prevents greywater from passing through.

Use greywater to irrigate drought-tolerant and native plants, but be careful not to over-irrigate them. These plants can survive typical droughts in their climate, but they may look better during the dry times with a little extra water — the reason many people irrigate them. Design a greywater system to spread out water as much as possible through the landscape. Note that some native plants don’t do well with summer irrigation (oak trees, for example). If you’re looking for ideas for appropriate native or low-water-use plants for your climate, visit the EPA’s website to find local sources of information (see Resources). Water districts and local extension services may also provide this information.

Use greywater to reduce your home’s energy needs by growing trees. Deciduous trees, planted on the south and west sides of your home, block the summer sun to keep your home cooler, while letting in winter sun to warm your home. Trees do more than just reduce energy use by blocking the sun: as they evaporate water, heat is removed from the air — a natural air conditioner.

Trees can shade driveways and patios, preventing the hardscape from absorbing the sun’s energy (which radiates back in the evening), keeping your outside environment cooler in the summer. Evergreen trees can block wind and keep your home warmer in the winter. Trees also block noise and glare, reduce pollution, and create an ecosystem for birds and other creatures. Before planting a new tree be sure to observe the sun patterns on your site so you can strategically locate the tree for the maximum benefit. see Resources for more information.

Anyone working in a landscape with a greywater system should understand how the system works and where the components are located; otherwise, they may unintentionally damage the system. Show your landscaper or gardener photos of pipe and outlet locations (pre-burial) and make sure they understand the importance of maintaining the outlets and mulch basins, never covering them with soil.

Many people have no idea how much water a plant needs. Here is a rough estimate of how many fruit trees you could irrigate from a simple washing machine system, assuming there is no rain to supplement the greywater irrigation. Determine your irrigation potential by multiplying the first number (one load per week) by the number of loads you do each week.

With the above estimates in mind, perform some basic calculations to determine more accurately how much to irrigate your plants. There are many factors that affect plants’ water requirements, including climate, exposure (e.g., southern or northern), wind, shade, mulch, type of plant, and plant size.

Next, I’ll show you two methods for estimating how many gallons per week a specific plant should receive. The first is a quick, rule-of-thumb estimate and is accurate enough to keep your plants healthy and happy. Use this method to guide your system design. For those of you wanting more detail, the second method (which incorporates evapotranspiration, or ET, rates) can help you fine-tune your design, though this level of precision is not essential and the calculation is considered optional.

Keep in mind that these methods, as with any technique for determining irrigation needs, provide only estimated amounts. Always observe your plants: they can receive a wide range of irrigation amounts and still grow healthily, so long as the soil doesn’t become waterlogged. Try to maximize your greywater potential and irrigate as many plants as possible; you’ll save more water if you under-irrigate and add supplemental water occasionally, as opposed to consistently over-irrigating.

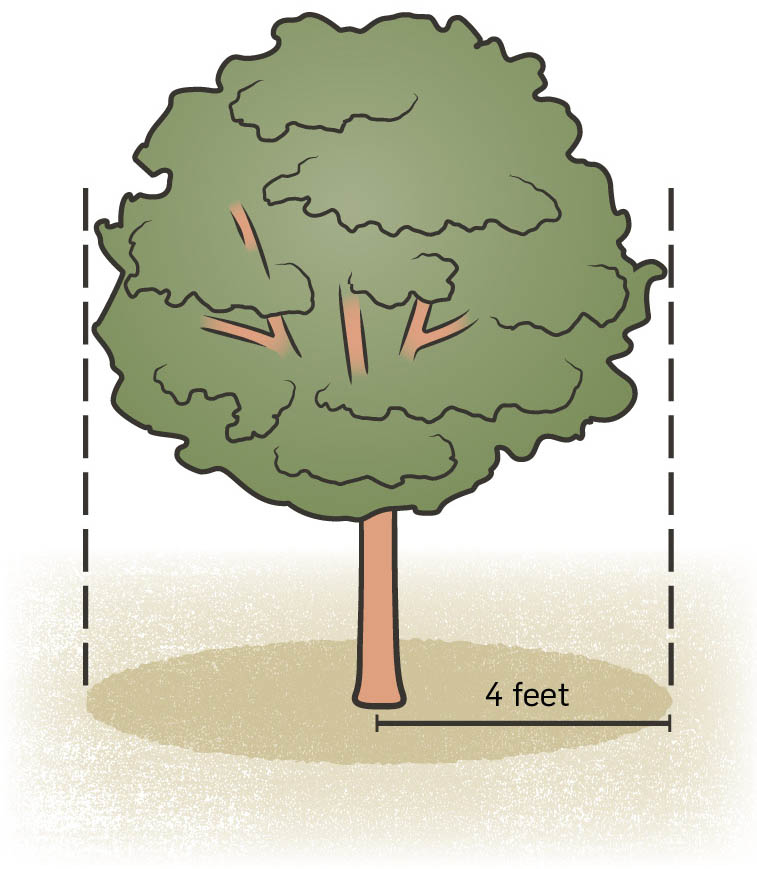

Determine the weekly irrigation need of a plant based on its size and the climate. The plant size is measured by the area under its canopy; for trees and bushes, this area is shaped like a circle. Use the area (A) of a circle: multiply π (3.14, or round to 3.0) by the circle’s radius (r) squared (A = π r2). Planted beds or hedgerows have a rectangular area. Find the area of a rectangle by multiplying the length by the width.

Find the area under a tree using A = πr2. Area of tree’s footprint = 3 × 4 ft. × 4 ft. = 48 square feet.

To determine the Peak irrigation need (in gallons per week), first find the number of square feet of planted area, then divide by:

For example, here’s the calculation for an apple tree that measures 4 feet from the center of the trunk to the outer branches:

Area of circle = π × r2 (rounding π to 3) = 3 × 42 = 48 square feet.

Next, divide 48 square feet by the number for the climate:

48 ÷ 1 = 48 gallons/week

48 ÷ 2 = 24 gallons/week

48 ÷ 4 = 12 gallons/week

This rule-of-thumb estimate is most accurate for plants with moderate water use, such as fruit trees. Water-loving wetland plants would like more water, while drought-tolerant or low-water-use plants require less. If you are irrigating a low-water-use or drought-tolerant plant, divide your estimate (gallons/week) in half again.

Evapotranspiration, or ET, is the combined effect of water evaporating from the soil and being used (transpired) by plants. In relatively warm, dry climates plants lose more water than in cooler, moister climates. This method assumes that all moisture by evapotranspiration will be replaced though irrigation. It factors in the type and size of the plant as well as the climate. You’ll need the following information:

The EPA’s WaterSense website has a tool you can use to find your peak irrigation month and subsequent reference ET rate (see Resources). The tool also provides average rainfall for the peak irrigation month so you can adjust your irrigation estimate accordingly. Visit their website and simply enter your zip code. Keep in mind that this data is for the peak irrigation month and you don’t need to irrigate this much all year long. Usually if you stay within 30 percent of this number, either lower or higher depending on your available greywater, the plants should be happy without supplemental irrigation.

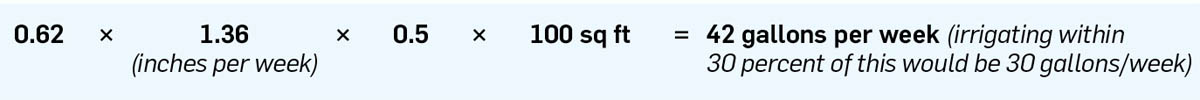

Use the formula below to calculate weekly plant water requirements:

The following examples look at irrigation requirements for a living fence made of pineapple guava bushes (moderate-water-needs plant; species factor: 0.5) covering a 100-square-foot area, using peak irrigation (as reported by the EPA WaterSense website).

Peak ET, July: 6.73 inches/month or 1.68 inches/week:

Tucson, AZ

Peak ET, June: 12.42 inches/month, or 3.1 inches/week:

Seattle, WA

Peak ET, July: 5.42 inches/month or 1.36 inches/week:

Miami, FL Peak ET, April: 6.65 inches/month or 1.66 inches/week:

These estimates don’t take into account summer rains; obviously plants won’t require as much water during the week if it rains. You can subtract average rainfall from the ET rate for this calculation. Depending on the rainfall frequency, however, this rain could come in one heavy storm or be spread out evenly over the month, and this will impact how much water plants would like during the week.

My first two greywater systems flowed through a bathtub wetland into a greywater pond, overflowing with water hyacinth. I loved the 8-foot-tall cattails that filtered shower water clear and odorless. It took a few years before I realized this wasn’t a greywater reuse system, rather an ecological disposal system; the cattails were sucking up the water that could have been irrigating my thirsty garden. (Once mature, the plants literally sucked up an entire shower on a hot day — not a drop overflowed out of the wetland to the garden.)

Though technically easy and also beautiful and fun, treating greywater for a backyard pond is not something I recommend. If your goal is to save water, a greywater pond isn’t the right choice. The quality of greywater is unsuitable to fill a pond; it must be filtered by wetland plants first (unless you want a pool of disgusting, stinky greywater). Thirsty wetland plants not only use water, but they also remove nutrients and organic matter from the water, which your garden could benefit from; less greywater flows out of the wetland than in.

A water-wise choice for anyone with both a pond and a landscape is to irrigate with greywater and fill the pond with freshwater (or rainwater), bypassing the need for the water-loving wetland filter. Separately, greywater ponds epitomize the concerns of the regulatory world. Their list of potential hazards includes: drowning risk for children, potential for direct contact with the water, mosquito breeding grounds, and possible overflow to a neighbor’s yard or storm drain. Ponding greywater is prohibited by even the most lenient codes.

Permaculture centers take pride in their greywater ponds. Shining photos of rural greywater-fed ponds are common in blogs, books, and magazines. It’s not often emphasized, however, that these ponds are typically filled with rainwater while just a fraction is “grey.”

People who try to replicate them are disappointed when their backyard greywater pond is a slimy, stinky, algae pool. A backyard rainwater pond won’t cause such headaches! (see Resources for info on rainwater ponds.)

Greywater can either benefit or harm plants, depending on what soaps and detergents you use. Its quality as an irrigation source is directly connected to what you put down the drain. Luckily, it’s easy to choose soaps and other products that are plant-friendly, avoiding the following ingredients:

Following are some products that have been used successfully for many years in greywater systems. This list is not exhaustive, and you may find others that are free of boron and very low in salts. Additionally, you can look up the ingredients for personal care products on the Environmental Working Group’s Skin Deep Cosmetics Database (see Resources).

The amount of salts you can send into your yard without damaging your plants depends on your climate, soil, and plants. If you live in a place with heavy, frequent rainfall, rain will leach salt out of the soil before it can build up to harm plants, so the occasional salty product won’t cause any harm. On the other hand, in places with salty tap water (such as groundwater or Colorado River water) and a dry climate, soils are more prone to salt buildup, so you should take more care to avoid adding salts from greywater. And keep in mind that fertilizers are high in salts and that salt tolerances of plants vary considerably. In arid climates, direct rainwater into greywater basins as well as rainwater basins to flush salts from the soil.