On 18 September 1714, a little over six weeks after the death of Queen Anne, her successor alighted in Greenwich. Georg Ludwig, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and Electoral Prince of Hanover (1660–1727), had last visited the country, of which he was now king, 34 years before. George, who could speak only a few words of English, spent nearly three years out of his 13-year reign in Hanover, where he continued to be Elector. This absenteeism has led to a belief that George left little mark on his adopted country and took no interest in its cultural life, apart from his patronage of the composer George Frideric Handel (1685–1759), who had worked for him in Hanover. However, George was quick to make use of the network of painters in royal service. Godfrey Kneller continued as principal painter, and he remained in post until his death in 1723, having painted every monarch from Charles II to George II. Kneller’s German birth must have been an advantage, but George I clearly admired his work, since in 1715 he awarded him a baronetcy, the highest honour accorded to any artist in Britain before Frederic Leighton was raised to the peerage in 1896. The leading decorative painter at court was Louis Laguerre, but George preferred James Thornhill (1675/6–1734), whose career was boosted by a wish to employ home-grown talent. In 1714 Thornhill was commissioned to paint the Prince of Wales’s bedroom at Hampton Court because, said Lord Halifax, 1st Lord of the Treasury, a failure to give such a prestigious job to a native artist ‘would prevent & discourage all countrymen everafter to attempt the like again’. In 1718 he painted decorative panels for a new state coach (fig.129), and was appointed the King’s History Painter in Ordinary. Two years later George knighted him, the first time a British-born artist had been so honoured, principally in recognition of Thornhill’s two greatest achievements, the Painted Hall at Greenwich and the murals on the interior of the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral.

George disliked the formality of English court life, preferring to manage with a small household. Resentment was stirred up when he dispensed with most of his bedchamber staff in favour of two trusted Turkish servants brought from Hanover, Mehemet and Mustapha. Mehemet (c.1660–1726), who was also in charge of the King’s Privy Purse, was painted in 1715 by Kneller, presumably at the King’s request (fig.130).

George’s most notable architectural commission in England was the addition of state rooms to Kensington Palace. These new interiors, a Privy Chamber, Cupola Room (fig.131) and large Drawing Room, provided space for formal court functions, so making good a lack that must have been felt since the destruction of Whitehall Palace. They are significant as embodiments of a new movement in architecture and design that was to dominate the eighteenth century, away from the dramatic Baroque style practised by such architects as John Vanbrugh in favour of an austere classicism that looked back to the sixteenth-century Italian architect Andrea Palladio, who had been so influential on Inigo Jones.

Although the reason given for not employing Thornhill to decorate the new rooms at Kensington Palace was expense, he was, in reality, a victim of this abrupt shift in taste. The commission was given instead to a younger painter, William Kent (1685–1748), who was setting out an a career that would range from painting and interior decoration to the design of furniture, buildings and gardens. Over the next 15 years he came to assume an even more significant role at court than Daniel Marot had enjoyed under William and Mary. Kent’s work at Kensington Palace, carried out in 1722–7, demonstrates his authoritative knowledge of classical architecture and decoration, learned during a decade he had spent in Italy, from 1709 to 1719. Among the consequences for the display of the Royal Collection was a new stress on the importance of sculpture in interiors, following Roman precedent. In the Cupola Room gilt-lead casts of antique sculpture filled the niches, and a marble relief of a Roman marriage carved by John Michael Rysbrack (1694–1770) was placed over the chimneypiece.

Kent also redecorated the King’s Gallery at Kensington, built for William III as a place to display Old Master paintings. The original treatment of the walls, green velvet hangings framed in brown wood, was replaced by red silk damask set off by white woodwork, a novel combination that was to become a customary form of decoration for picture galleries in Britain (fig.132). Sculpture was introduced in the form of classical busts on plinths together with personifications of the seasons by the Roman sculptor Camillo Rusconi (1658–1728; fig.133). Kent also instigated a new sort of picture frame, architectural in form, like the surroundings he designed for doors and window, thereby integrating the display of paintings with interior decoration more tightly than before. Large canvases, mostly Venetian, were hung opposite the windows, with Van Dyck’s ‘Great Peece’ and the equestrian portrait of Charles I with M. de St Antoine on the end walls (see figs 59 and 60), a tribute to the collector of these masterpieces. Kent arranged the pictures with an exacting symmetry that was recreated (in part using copies) when the gallery was restored to its early eighteenth-century appearance by Historic Royal Palaces in 1993–4.

The significance that Kent placed on the architectural disposition of pictures was so great that the frames became near-permanent fixtures, left in place when the paintings within them were changed. Another consequence was that canvases were readily altered in size to fit the requirements of the decoration. Presumably with the needs of the new state rooms at Kensington in mind, in 1723 the King bought six large paintings from John Law (1671–1729), formerly Controller General of Finances in France. They included two outstanding works by Rubens, his equestrian portrait of Don Rodrigo Calderon (then thought to represent the Duke of Alba) and The Holy Family with St Francis (fig.134). Kent installed the latter in the Drawing Room in a frame that formed an architectural unity with the chimneypiece, also designed by him. The painting was enlarged by no less than 60 cm at the top to give it the upright format Kent’s scheme required, a change that has since been amended.

George I initiated a family tradition that was to last over a century: bad relations between the monarch and his heir. During his absences in Hanover George I refused to let the Prince of Wales serve as regent, and it was only with reluctance that he allowed him to be appointed ‘Guardian of the Realm’, a title unearthed from the fourteenth century, when it had been used by the Black Prince. In 1717 mutual resentment tipped over into a quarrel and the King ordered the Prince and Princess of Wales to move their households out of St James’s Palace. From then on they lived principally in Leicester House in Leicester Fields (later Leicester Square), and spent their summers in a house bought by Prince George in 1719, Richmond Lodge, on the edge of the deer park at Richmond. It was not until 1720 that the Prince and his father were grudgingly back on speaking terms. This unhappy family saga, which was to be repeated in the next generation, had some fortunate consequences for the Royal Collection. Successive Princes and Princesses of Wales had both a practical incentive to buy and commission works of art – to furnish their independent establishments – and a motive to cultivate tastes that would distinguish them from the monarch.

Prince George, who succeeded his father in 1727, participated more willingly in the ceremonial life of the monarchy. Unlike his father, who was divorced, he was happily married to Caroline of Ansbach (1683–1737), whose interest in art and scholarship impressed her contemporaries even if they sometimes baffled her husband. George II’s favourite palace was Hampton Court, and for the decade between his accession and the death of Queen Caroline in 1737 it was the centre of court life. Large sums were spent on redecorating and refurnishing the state apartments under the direction of William Kent, and changes were made to the arrangement of works of art. The Triumph of Caesar (see fig.46), which in 1717 had been restored and reframed on George I’s orders, was moved into the Queen’s Drawing Room, where the now old-fashioned murals by Thornhill were covered up. The canvases were replaced in The Queen’s Gallery with a set of tapestries depicting the the life of Alexander the Great, woven to a design by Charles Le Brun (1619–90) for Louis XIV, which George II bought in 1727. Below the tapestries was a new set of giltwood furniture, part of a large quantity of new furnishings for Hampton Court designed by Kent. These included a pair of magnificent armchairs (fig.135) and 24 ensuite stools made for the Queen’s Withdrawing Room, where George and Caroline received large assemblies of guests.

There is little evidence that George II shared his father’s interest in art. In 1734 he did, however, pay for Kent to restore Rubens’s ceiling in the Banqueting House, and joined the Queen in climbing the 40-feet high scaffold to inspect the work. Like his father, the King hated having his portrait painted, but was willing to make an exception for the leading miniature painter at court, the enamellist Christian Friedrich Zincke (c.1684–1767), whose company he enjoyed. Zincke had moved to London from Dresden at the suggestion of Charles Boit, whose attempt to make an oversized enamel picture of the Battle of Blenheim for Queen Anne had been a failure. Zincke’s work, although less ambitious in scale, is technically flawless and his numerous miniatures include some of the most engaging portraits of George, Caroline and their family (figs 136 and 137). The outstanding sculptor then at work in Britain, Louis-François Roubiliac (1702–62), carved a bust of George II but the initiative for that was taken by an old comrade in arms, John, 1st Earl Ligonier (1680–1770). He had fought with Prince George, as he then was, in the victory over Louis XIV at Oudenaarde in 1708. At Dettingen in 1743, the last occasion on which a British sovereign commanded troops in battle, George invested Ligonier with the Order of the Bath, which had been founded by George I in 1725. Its badge is proudly displayed in the superb bust that Roubiliac carved of Ligonier at the same time as that of the King (fig.138).

Caroline and George had a close relationship in many ways, but the King often worked his tempers off on his long-suffering wife. There are vivid descriptions of his bad behaviour to her in the memoirs of the courtier Lord Hervey, and although Hervey played up the King’s boorishness to highlight the good nature of his friend the Queen, his accounts of George’s impatience with her artistic interests convincingly evoke a husband seeking to impose his authority in an area where his wife was more knowledgeable. In 1735, for example, George objected to the way that in his absence she ‘had taken several very bad pictures out of the great drawing-room at Kensington, and put very good ones in their place’. Ordering that all the old paintings should be returned, George rounded on Hervey: ‘I have a great respect for your taste in what you understand, but in pictures I beg leave to follow my own: I suppose you assisted the Queen with your fine advice when she was pulling my house to pieces and spoiling all my furniture: thank God, at least she has left the walls standing!’ When Hervey slyly asked if the King wanted ‘the gigantic fat Venus restored too’, he was told, ‘Yes, my Lord; I am not so nice as your Lordship. I like my fat Venus much better than anything you have given me instead of her.’ It seems likely that George was referring to a large Venus and Cupid by Giorgio Vasari (1511–74) after a design by Michelangelo that is still in the Royal Collection.

Vasari’s Venus and Cupid had been a gift to George from Caroline, whose degree of interest in the visual arts was unmatched by any Queen consort since the time of Henrietta Maria. Her intellectual outlook was a result of her upbringing at the court of the Elector of Brandenburg in Berlin, renowned for its artistic and architectural patronage. Her strong interest in the genealogy and history of the British royal family was reflected in her appreciation of works of art as documents that provided evidence about the past. This attitude was shared by George I, who must surely have been consulted about the choice of paintings to be hung in the redecorated state bedchamber in the apartments at Hampton Court occupied from 1714 by George and Caroline as Prince and Princess of Wales. A portrait of James I & VI by Paul van Somer was placed over the chimneypiece, flanked by portraits of Anne of Denmark by Van Somer and Elizabeth of Bohemia (George I’s grandmother) by Daniel Mytens. Van Dyck’s posthumous portrait of Henry, Prince of Wales, was placed over the door that led into the Privy Chamber. This arrangement laid explicit stress on George I’s Stuart ancestry, and Caroline’s own interest in royal portraits has been interpreted as a desire to legitimise the Hanoverians in the face of a Jacobite threat that continued until 1745, when Bonnie Prince Charlie’s uprising was crushed.

However, Caroline’s interest in history was broader than that, as she sought out portraits that would form a wider visual history of the English monarchy, both for her own education and, perhaps, for that of her children. She persuaded Lord Cornwallis, whose family had a history of service to the Crown stretching back into the sixteenth century, to sell her a group of portraits of monarchs ranging from Edward II to Mary I, which she supplemented by purchases of portraits of Henry IV and Elizabeth I. Most of these were hung in her private rooms at Kensington Palace, together with some of the early portraits in the Royal Collection, including Hans Eworth’s Elizabeth I and the Three Goddesses (see fig.23). Her interest in historical paintings also attracted gifts, notably The Memorial of Lord Darnley (see fig.34), given to her in about 1736 by her Master of the Horse, the Earl of Pomfret, whose wife, Henrietta, was a Lady of the Bedchamber and shared the Queen’s antiquarian interests. Caroline also commissioned paintings on historical subjects: Kent painted three canvases for her depicting the life of Henry V, which were hung in her dressing room at St James’s Palace.

The Queen also systematically gathered together the historic miniatures in the Royal Collection, which she hung on the walls of her Picture Closet at Kensington Palace, a small room that had previously been William III’s Little Bedchamber. They were supplemented by her best-known contribution to the appreciation of the Royal Collection, the study and display of the Hans Holbein drawings. She had found these in a bureau at Kensington, and although it is sometimes assumed that they had been forgotten in some bottom drawer, an inventory of the bureau’s contents reveals that it contained all Charles II’s Old Master drawings, including those by Leonardo. They may have been moved here from Whitehall by William III when he reorganised the picture collections. Caroline had the Holbein volume disbound so that she could frame the drawings and hang them – not a wise move in conservation terms, but luckily George III had them put back into portfolios before they could fade. Her discovery may have prompted Caroline (or perhaps her husband) to buy Holbein’s portrait of Sir Henry Guildford (see figs 14 and 15). Among the other elements of the Queen’s Cabinet Room were large collections of coins, medals, cameos and gems (figs 139–142). Caroline was the first member of the royal family to show a sustained interest in historic gems, and she made interesting additions to the few that had survived in the Royal Collection from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. They include two cameos depicting Henry VIII, imitating Holbein portraits: it is not known whether she was aware these were in fact modern.

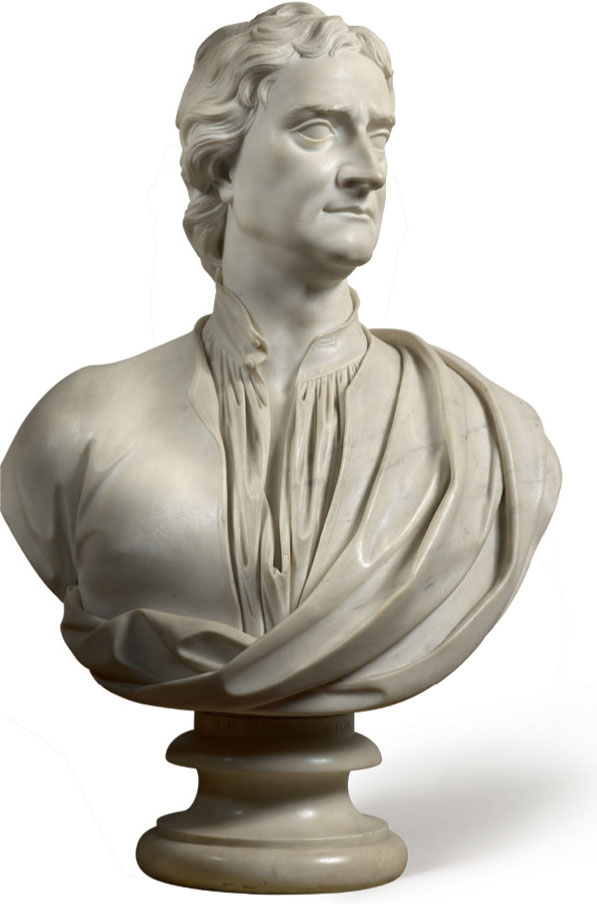

Caroline’s independent architectural commissions were modest in scale but rich in iconographical interest. Regrettably, none have survived. On his accession, George settled Richmond Lodge on the Queen as a potential dower house. This provided her with a semi-private retreat to pursue one of her major interests, gardening. While still Princess of Wales she had the grounds at Richmond laid out for her by the leading designer Charles Bridgeman (1690–1738), who was at the same time overseeing large additions to the gardens at Kensington Palace. She commissioned Kent to design two garden buildings for Richmond. One was a thatched Gothic structure called Merlin’s Cave, furnished with tableaux of waxwork figures from mythology and history, including Elizabeth I. These puzzled contemporaries, since no programme was provided, but the ensemble seems to have been designed to evoke Merlin’s legendary prophecy of a sovereign who would unite the British people. Kent’s other Richmond building was a spacious classical hermitage, equipped with a library and bedroom, built in 1731–2. Nothing of Merlin’s Cave remains, but a series of five marble busts survives from the hermitage. Carved by Giovanni Battista Guelfi (1690/1–1736), who had moved to England in 1714 as a result of meeting Kent in Rome, the busts are posthumous portraits of eminent British philosophers and scientists, including Newton and Boyle (fig.143). All had in common a belief in natural theology – that study of the laws of nature supported Christian faith. In 1735 Caroline commissioned a second series of busts, depicting royal figures from medieval and Tudor history, for a new library that Kent had designed for her at St James’s Palace. Guelfi had by then returned to Italy and so the job was given to Rysbrack, who had worked at Kensington Palace for George I and had maintained a close working relationship with Kent. The 11 busts of monarchs, which included Alfred, the Black Prince (fig.144), Henry V and Elizabeth I, were modelled in terracotta, but if there was an intention to carve them in marble, the idea was abandoned when Caroline died in November 1737.

The ill feeling between George II and his father was magnified many times over in George and Caroline’s relationship with their eldest son, Frederick, Prince of Wales (1707–51) and he was forced in consequence to build a public life independent of his parents. In the years between his arrival in England in 1728 and his premature death, Frederick established himself not only as a leader of fashion, but also a collector with a range and depth of interest in the arts not seen in the royal family since the time of Charles I, on whom he modelled himself.

When George I succeeded to the throne, Frederick, then just seven years old, was left behind in Hanover to represent his dynasty. From the moment he was summoned to London to meet the parents he barely knew, their favouritism towards his English-born younger brother, William, irked him. George refused to let him serve as regent when the King was in Hanover (a role assumed by Caroline) and delayed arranging his marriage – it was not until 1736 that Frederick was finally married to Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg (1719–72). They lived principally in two houses that Frederick had acquired in the early 1730s, Carlton House on the Mall and the White House at Kew, near Richmond Lodge. Both were remodelled and decorated by Kent.

Frederick’s landscaping of the White House, for which he commissioned exotic garden structures, such as a ‘House of Confucius’, paralleled his mother’s activities at Richmond Lodge. The close similarities in their interests, not only in gardening but also in collecting and Tudor and Stuart history, make it even sadder that their relationship was so poisonous. Their already fractured relationship was exacerbated by Frederick’s involvement in politics. He created a party following at Westminster that was opposed to the Prime Minister, Robert Walpole (1676–1745), whom George and Caroline strongly supported. The Queen never forgave him.

Exile from court meant that Frederick, more than any other previous royal prince, lived like a commoner, albeit an aristocratic one. This suited the political message he sought to promote – that he intended to be a patriot king, who would uphold parliamentary democracy and would not be dominated by corrupt politicians, as he believed his parents to be. Such beliefs underpinned the uncourtly approachability that Frederick sought to project in his portraits from the mid 1730s onwards. In 1733 he commissioned a group portrait of himself with his three eldest sisters that has an informality unprecedented in British royal portraiture. Painted by Philippe Mercier (1689–1760), it shows Frederick playing his cello – an unusual instrument for an amateur (fig.145). For the White House, the sporting artist John Wootton (c.1682–1764) painted several large canvases depicting the prince hunting with friends. In 1731 Frederick commissioned Kent to design a barge for travel on the Thames (fig.147). This spectacularly decorated vessel, which was intended to draw all eyes to the Prince, was used by him for the first time in March 1732, when he and his family embarked from Chelsea Hospital for Somerset House, where they visited Wootton’s studio to view ‘progress in cleaning and mending the Royal Pictures’.

Mercier, who was born in Berlin of French parentage, and had worked in London since about 1716, had been employed by Frederick as his principal painter since 1729. An experienced dealer, he bought art for Frederick, including paintings by David Teniers the Younger (1610–90), whose work – which Mercier had specialised in engraving – was to be a life-long enthusiasm for Frederick (fig.146). This was the beginning of a sizeable collection that played an important part in the way that Frederick wanted to be perceived. To bolster his patriotic image he wished to encourage British artists, and planned that when he was King he would establish an academy for drawing and painting – an ambition that his son, as George III, was to fulfil. Frederick had a deep interest in the Royal Collection and its history. He consulted George Vertue (1684–1756), the pioneering historian of art, for information about paintings, allowed him to copy the manuscript inventories of Charles I’s collection and commissioned Vertue to list Frederick’s own pictures. Vertue recorded a conversation with Frederick in 1749 in which the Prince talked about ‘paintings & famous Artists in England formerly – about the Cartons of Raphael Urbin. The paintings of Rubens in the banquetting house at Whitehall’, evidence that Vertue was right to claim that ‘no Prince since King Charles the First took so much pleasure nor observations in works of art or artists’.

Frederick’s collecting was guided in part by his royal predecessors. To judge by his purchase of a portrait of Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk (c.1539–40), he shared his mother’s enthusiasm for Holbein. He also bought miniatures by Isaac and Peter Oliver, among them self-portraits by both artists, together with one of Isaac’s most celebrated works, A Young Man Seated Under a Tree, which may perhaps have appealed to the Prince partly because of its depiction of a garden (fig.148). Other purchases suggest a wish to emulate Charles I’s collecting. The Prince bought paintings by Rubens, including scenes depicting Summer and Winter, once owned by the 1st Duke of Buckingham, and several major works by Van Dyck, including one of his finest English portraits, of the royalist poet and playwright Sir Thomas Killigrew with an unknown man (fig.149). He also bought a set of Mortlake tapestries commissioned by Charles when Prince of Wales and a portrait of Prince Henry in the hunting field painted by Robert Peake in about 1605. Frederick acquired not only Italian paintings of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries of the sort that might have appealed to Charles but also a set of 13 marble statues of classical deities by a pupil of Giambologna, Pietro Francavilla (1548–1615). Intended for the Prince’s gardens at Kew, the sculptures arrived from Florence just after his death.

In other aspects of his collecting Frederick struck out independently. He was one of the first collectors in England to show a sustained appreciation of seventeenth-century French art, buying two superb landscapes by Claude Lorrain (1604/5–82), of the type that would soon be so influential on British artists (fig.150), as well as paintings by Gaspard Dughet (1615–75) and Eustache Le Sueur (1617–55). Another major purchase was an album of drawings by Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665; fig.151) that had been compiled during the artist’s lifetime by one of his patrons, Cardinal Camillo Massimi (1620–77). The most significant addition to the royal holdings of Old Master drawings since the time of Charles II, the album is also compensation for the odd fact that the Royal Collection contains no painting by an artist so eagerly collected by the British.

Frederick’s interest in French art extended into the eighteenth century, but like almost every English collector of his time, he was more interested in the country’s luxury decorative arts than its painting. He had a taste for rococo decoration, evident, for example, in picture frames made for him by the Huguenot carver Paul Petit and gold snuff boxes (fig.153), of which there is a group associated with Frederick, made in London by immigrant French or German craftsmen in the 1740s. Most spectacular of all is the ‘Neptune’ centrepiece of a silver-gilt table service commissioned by the Prince in the early 1740s that is one of the pinnacles of Rococo design in England (fig.152). It appears to be a collaboration between two leading silversmiths, the Huguenot Paul Crespin (1694–1770) and the Liège-born Nicholas Sprimont (1713–71), who was to found the Chelsea porcelain factory.

This extraordinary piece of silver evokes the impressive social life of Frederick’s households. The demands of both hospitality, an important aspect of his political career, and his large family – he and Augusta had nine children – prompted him to acquire new residences, including Leicester House, which had been his parents’ home, and Cliveden, overlooking the Thames in Berkshire. He was devoted to his children – there was no sign that Frederick and Augusta would treat their children as he had been treated by his parents, a point that an enchanting life-size group portrait he commissioned of his children from the Swiss painter Barthélemy du Pan (1712–63) in 1747 may have been designed to emphasise (fig.154). On 20 March 1751 Frederick died suddenly from a burst abscess on his lung. A rhyme was soon in circulation: ‘Here lies Fred, / Who was alive and is dead: / Had it been his father, / I had much rather …’. but in fact George II defied the expectations of his son’s supporters by living on to 1760.