Self-Guided Tour

Self-Guided TourOFFICIAL SIGHTS AT PRAGUE CASTLE (PRAŽSKÝ HRAD)

Castle Square (Hradčanské Náměstí)

St. Vitus Treasury in the Chapel of the Holy Cross

▲▲▲St. Vitus Cathedral (Katedrála Sv. Víta)

▲Old Royal Palace (Starý Královský Palác)

The Story of Prague Castle Exhibit (Příběh Pražského Hradu)

▲Basilica and Convent of St. George (Bazilika Sv. Jiří)

▲▲Lobkowicz Palace (Lobkowiczký Palác)

▲Strahov Monastery and Library (Strahovský Klášter a Knihovna)

ROYAL SUMMER PALACE AND ROYAL GARDENS

Royal Summer Palace (Královský Letohrádek)

Royal Gardens (Královská Zahrada)

Looming above Prague, dominating its skyline, is the Castle Quarter. Prague Castle and its surrounding sights are packed with Czech history, as well as with tourists. In addition to the castle, I enjoy visiting the nearby Strahov Monastery, which has a fascinating old library and beautiful views over all of Prague.

You have three options: taxi, walk, or tram.

By taxi, take it to the top of Nerudova street, just below Castle Square. To walk up, figure 20 minutes uphill from Charles Bridge, along cobbled Nerudova street. After about 10 minutes, a steep lane on the right leads to Castle Square; or, if you continue straight, Nerudova becomes Úvoz and climbs to the Strahov Monastery.

For the tram, catch tram #22 at one of three convenient stops: the Národní Třída stop (between Wenceslas Square and the National Theater in the New Town); in front of the National Theater (Národní Divadlo, on the riverbank in the New Town); and at Malostranská (the Metro stop in the Little Quarter).

After rattling up the hill, tram #22 makes three stops near the castle:

Královský Letohrádek allows a scenic but slow approach through the Royal Gardens to the bridge near the castle’s northern entrance; Pražský Hrad offers the quickest commute to the castle—from the tram stop, simply walk along U Prašného Mostu and over the bridge, past the stonefaced-but-photo-op-friendly guards at the northern entrance, and into the castle’s Second Courtyard; and Pohořelec is best if you’d like to start with the Strahov Monastery, then hike down to the castle. After getting off at the Pohořelec tram stop, follow the tracks for 50 yards, take the pedestrian lane that rises up beside the tram tracks, and enter the fancy gate on the left near the tall red-brick wall. You’ll see the twin spires of the monastery; the library entrance is on the little square with the monastery church.

Prague Castle is one of the city’s most crowded sights. Huge throngs of tourists turn the grounds into a sea of people during peak times (9:30-12:30, especially May-Sept). The most cramped area is the free-to-enter vestibule inside St. Vitus Cathedral; any sight that you pay to enter—including other parts of the cathedral—will be less jammed.

Early-Bird Visit: Leave your hotel no later than 8:00 (earlier is even better). Ride tram #22 up to the Pražský Hrad stop (or leave yourself time to walk through the Royal Gardens, and get off at Královský Letohrádek), then use the northern entrance to the complex’s Second Courtyard and buy your tickets. See Castle Square, and most important, be sure that you’re standing at the front door of St. Vitus Cathedral when it opens at the stroke of 9:00. For 10 minutes, you’ll have the sacred space to yourself...then, on your way out, you’ll pass a noisy human traffic jam of multinational tour groups clogging the entrance. Visit the rest of the castle sights at your leisure: the Old Royal Palace, the Basilica of St. George, and the Golden Lane. To see the Strahov Monastery and/or Loreta Church after your castle visit, backtrack uphill (either by foot, or by hopping back on tram #22 at a lower stop—near the castle, or even from the Malostranská stop near the river).

Afternoon Visit: Ride tram #22 to the Pohořelec stop. Tour the Strahov Monastery, then drop by Loreta Church on your way to Castle Square. By the time you hit the sights, the crowds should be thinning out (if St. Vitus is jammed, circle back later). The only risk here is running out of time to enter all the sights (which close at 17:00 in summer, or 16:00 in winter); in summer, I’d start at Strahov no later than 14:00.

Nighttime Visit: Least crowded of all is nighttime. True, the sights are closed, but the castle grounds are free, safe, peaceful, floodlit, and open late. The tiny, normally jammed Golden Lane is empty and romantic at night—and no ticket is required.

This vast and sprawling complex, worth ▲▲, has been the seat of Czech power for centuries. It collects a wide range of sights, including the country’s top church, its former royal palace, a higgledy-piggledy lane, and an assortment of history and art museums. (These are listed here in order, from top to bottom, starting at the main gate.) While it’s imposing and a bit intimidating to sightseers, the casual visitor finds that a quick and targeted visit is ideal. The sights listed here are part of the official castle complex, and share opening hours and tickets. Which ticket you choose depends on which sights you want to enter—so familiarize yourself with the options before buying your ticket.

Ticket Options: While you can enter the grounds for free, most sights require tickets. For a quick visit, get the 250-Kč “Circuit B” ticket, which hits the highlights (St. Vitus Cathedral, Old Royal Palace, Basilica of St. George, Golden Lane). For a few bucks more, “Circuit A” (350 Kč) adds “The Story of Prague Castle” exhibit and a few other sights worthwhile for those with a healthy interest in history and art. You can buy tickets at three different ticket offices in the castle’s second and third courtyards. Lines can be long at one and nonexistent at the next, so if it’s crowded, check all three. Climbing St. Vitus Cathedral’s Great South Tower requires a separate 150-Kč ticket.

Tours: Tours in English and an audioguide are available, but I’d skip both in favor of this book’s self-guided tour (tours-100 Kč plus entry ticket, covers only the cathedral and Old Royal Palace; audioguide-350 Kč plus 500-Kč deposit).

Hours: Castle sights—daily 9:00-17:00, Nov-March until 16:00; castle grounds—daily 5:00-24:00; castle gardens—daily 10:00-18:00 in summer, closed off-season. St. Vitus Cathedral is closed Sunday mornings for Mass, and can be closed unexpectedly at other times. The Great South Tower of St. Vitus Cathedral is open daily 10:00-18:00, until 16:00 in winter, www.hrad.cz.

Self-Guided Tour

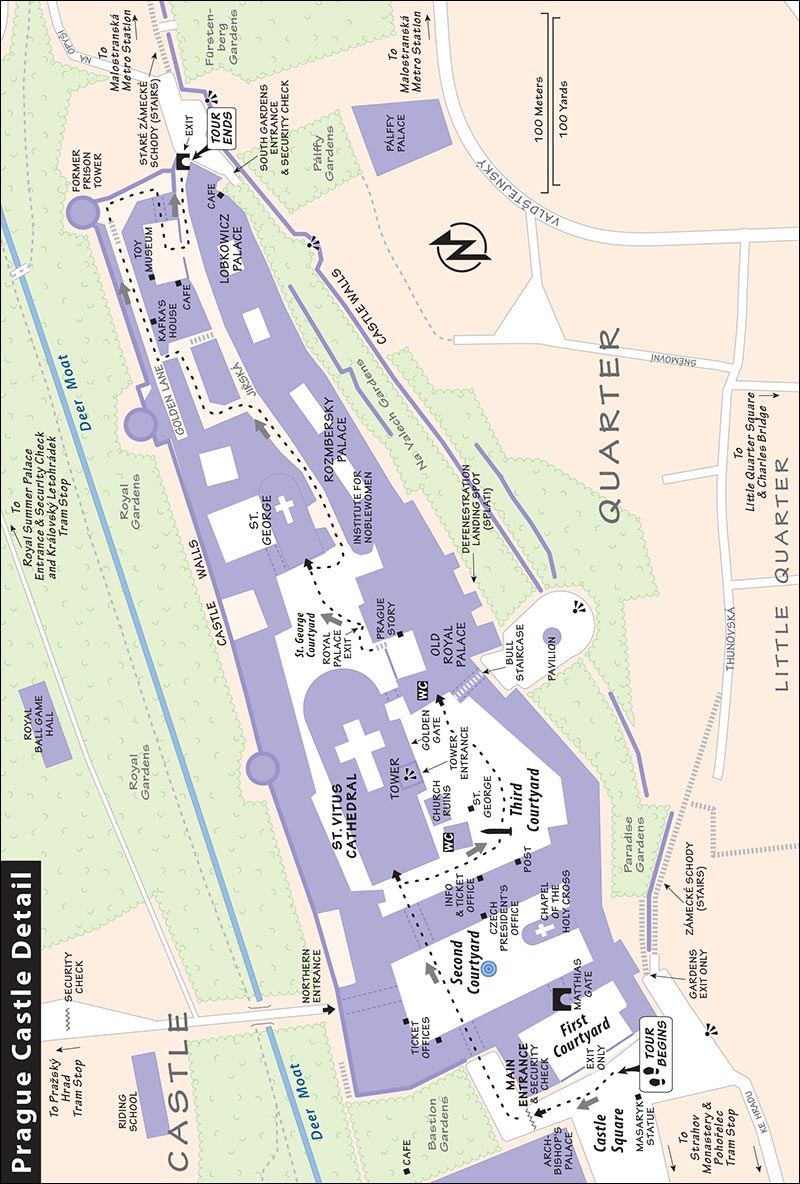

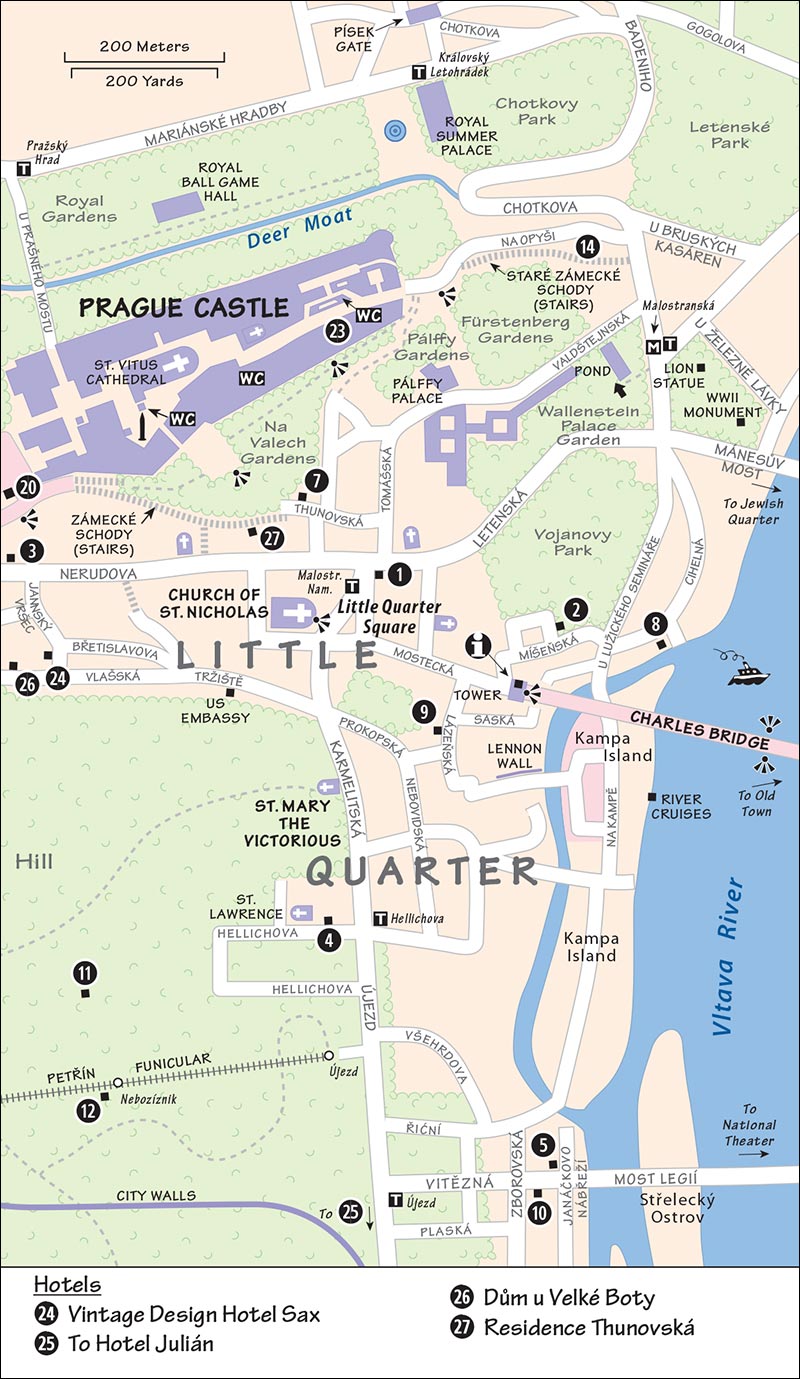

Self-Guided Tour(See “Prague Castle Detail” map, here.)

• Begin your visit to the castle complex at...

You’re standing at the tip of the medieval iceberg called Prague Castle. It’s a 1,900-foot-long series of courtyards, churches, and palaces, covering 750,000 square feet—by some measures, the largest castle on earth. In the center of the complex sits St. Vitus Cathedral (the two prickly steeples you see rising above the buildings).

You can’t miss the main entrance: a gateway with a golden arch, guarded by two fighting-giant statues and two real-life soldiers in their blue-and-white guardhouses. The stoic guards make a great photo-op, as does the changing of the guard (on the hour from 5:00-23:00). In fact, there’s a guard-changing ceremony at every gate: top, bottom, and side. The best ceremony and music occurs at noon, at the top gate.

Now turn around and survey the broad expanses of Castle Square. Enjoy the awesome city view and the entertaining bands that play regularly at the gate. (If the Prague Castle Orchestra is playing, say hello to friendly, mustachioed Josef, and consider buying the group’s CD—it’s terrific.) From the square, stairs lead down to the Little Quarter.

Castle Square was the focal point of medieval power. The archbishop lived (and still lives) in the Archbishop’s Palace—the ornate, white-and-yellow Rococo palace on the right. The portal on the left leads to the Sternberg Palace art museum, with European paintings.

On the left side of the square, the building with a step-gable roofline is Schwarzenberg Palace, where the aristocratic families of Český Krumlov “humbly” stayed when they were visiting from their country estates. Notice the envelope-shaped patterns stamped on the exterior. These Renaissance-era adornments etched into wet stucco—called sgraffito—decorate buildings throughout the castle, all over Prague, and across the Czech Republic. Today the castle is an art museum with a collection of Baroque-era Czech paintings and sculpture.

The black Baroque sculpture in the middle of the square is a plague column. Erected as a token of gratitude to Mary and the saints for saving the population from epidemic disease, these columns are an integral part of the main squares of many Habsburg towns.

Closer to you, near the overlook, the statue of a man in a business suit (marked TGM) honors the father of modern Czechoslovakia: Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (1850-1937). At the end of World War I, Masaryk—a former university prof and pal of Woodrow Wilson—united the Czechs and the Slovaks into one nation and became its first president. He was the only 20th-century leader to live in Prague Castle.

• Let’s enter the castle. Veer left through the security checkpoint and emerge into the Second Courtyard. Two ticket offices (with information desks) are diagonally across from the Chapel of the Holy Cross. If the line isn’t too long, buy a ticket now. Straight ahead as you enter is the...

This pricey-to-view collection shows off the accumulated wealth of the cathedral’s ecclesiastical gear. The highlight, dating from Charles IV’s reign (1360s), is a golden reliquary in the shape of a cross; used during coronation ceremonies, the cross contains what are supposedly the actual thorns, nails, sponge, rope, and fragments of the cross from Jesus’ Crucifixion. You’ll also see reliquary busts in the shape of saints (Vitus, Wenceslas, and Adalbert); monstrances slathered in diamonds and other precious stones; chalices; and icons. It’s a fine collection, but it’s outrageously overpriced. Skip it unless you’re a monstrance aficionado.

Cost and Hours: 300 Kč, includes torturously dull audioguide; buy ticket at entrance—not at castle ticket office, which sells only a combo-ticket that adds another museum; daily 10:00-18:00, last entry one hour before closing, tel. 224-372-432.

• From the Second Courtyard, proceed into the Third Courtyard. You’ll be face-to-face with...

This towering house of worship—with its flying buttresses and spiny spires—is the top church of the Czech people. Many VIPs from this nation’s history—from saints to statesmen—are buried here. You can step into the very congested entry vestibule for a peek at the interior, but it’s worth paying for a ticket that lets you go deeper, leave some of the crowds behind, and explore.

Visiting the Cathedral: The two soaring towers of this Gothic wonder rise 270 feet up. The ornate facade features pointed arches, elaborate tracery, Flamboyant pinnacles, a rose window, a dozen statues of saints, and gargoyles sticking their tongues out.

So what’s up with the four guys in modern suits carved into the stone, as if supporting the big round window on their shoulders? They’re the architects and builders who finished the church six centuries after it was started. Even though church construction got underway in 1344, wars, plagues, and the reforms of Jan Hus conspired to stall its completion. Finally, fueled by a burst of Czech nationalism, Prague’s top church was finished in 1929 for the 1,000th Jubilee anniversary of St. Wenceslas. The entrance facade and towers were the last parts to be finished.

• Enter the cathedral. If it’s not too crowded in the free entrance area, work your way to the middle of the church for a good...

View down the Nave: The church is huge—more than 400 feet long and 100 feet high—and flooded with light. Notice the intricate “net” vaulting on the ceiling, especially at the far end. It’s the signature feature of the church’s chief architect, Peter Parler (who also built the Charles Bridge).

• Now make your way through the crowds and pass through the ticket turnstile (left of the roped-off area). The third window on the left wall is worth a close look.

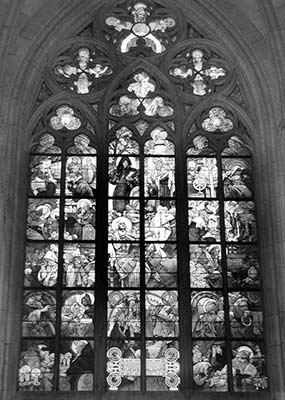

Mucha Stained-Glass Window: This masterful 1931 Art Nouveau window was designed by Czech artist Alfons Mucha and executed by a stained-glass craftsman (if you like this, you’ll love the Mucha Museum in the New Town—see here).

Mucha’s window was created to celebrate the birth of the Czech nation and the life of Wenceslas. The main scene (in the four central panels) shows Wenceslas as an impressionable child kneeling at the feet of his Christian grandmother, St. Ludmila. She spreads her arms and teaches him to pray. Wenceslas would grow up to champion Christianity, uniting the Czech people.

Above Wenceslas are the two saints who first brought Christianity to the region: Cyril (the monk in black hood holding the Bible) and his older brother, Methodius (with beard and bishop’s garb). They baptize a kneeling convert.

Follow their story in the side panels, starting in the upper left. Around A.D. 860 (back when Ludmila was just a girl), these two Greek missionary brothers arrive in Moravia to preach. The pagan Czechs have no written language to read the Bible, so (in the next scene below), Cyril bends at his desk to design the necessary alphabet (Glagolitic, which later developed into Cyrillic), while Methodius meditates. In the next three scenes, they travel to Rome and present their newly translated Bible to the pope. But Cyril falls ill, and Methodius watches his kid brother die.

Methodius carries on (in the upper right), becoming bishop of the Czech lands. Next, he’s arrested for heresy for violating the pure Latin Bible. He’s sent to a lonely prison. When he’s finally set free, he retires to a monastery, where he dies mourned by the faithful.

But that’s just the beginning of the story. At the bottom center are two beautiful (classic Mucha) maidens, representing the bright future of the Czech and Slovak peoples.

• Continue circulating around the church, following the one-way, clockwise route.

The Old Church: Just after the transept, notice there’s a slight incline in the floor. That’s because the church was constructed in two distinct stages. You’re entering the older, 14th-century Gothic section. The front half (where you came in) is a Neo-Gothic extension that was finally completed in the 1920s (which is why much of the stained glass has a modern design). For 400 years—as the nave was being extended—a temporary wall kept the functional altar area protected from the construction zone.

• In the choir area (on your right), soon after the transept, look for the big, white marble tomb surrounded by a black iron fence.

Royal Mausoleum: This contains the remains of the first Habsburgs to rule Bohemia, including Ferdinand I, his wife Anne, and Maximilian II. The tomb dates from 1590, when Prague was a major Habsburg city.

• Just after the choir, as you begin to circle around the back of the altar, watch on your right for the fascinating, carved-wood...

Relief of Prague: This depicts the aftermath of the Battle of White Mountain, when the Protestant King Frederic escaped over the Charles Bridge (before it had any statues). Carved in 1630, the relief gives you a peek at old Prague. Find the Týn Church (far left) and St. Vitus Cathedral (far right), which was half-built at that time. Back then, the Týn Church was Hussite, so the centerpiece of its facade is not the Virgin Mary (more of a Catholic figure), but a chalice, a symbol of Jan Hus’ ideals. The old city walls—now replaced by the main streets of the city—stand strong. The Jewish Quarter is the flood-prone zone along the riverside below the bridge on the left—land no one else wanted. The weir system on the river—the wooden barriers that help control its flow—survives to this day.

• Circling around the high altar, you’ll see various...

Tombs in the Apse: Among the graves of medieval kings and bishops is that of St. Vitus, shown as a young man clutching a book and gazing up to heaven. Why is this huge cathedral dedicated to this rather obscure saint, who was martyred in Italy in A.D. 303 and never set foot in Bohemia? A piece of Vitus’ arm bone (a holy relic) was supposedly acquired by Wenceslas I in 925. Wenceslas built a church to house the relic on this spot, attracting crowds of pilgrims. Vitus became quite popular throughout the Germanic and Slavic lands, and revelers danced on his feast day. (He’s now the patron saint of dancers.) At the statue’s feet is a rooster, because the saint was thrown into a boiling cauldron along with the bird (the Romans’ secret sauce)...but he miraculously survived.

A few steps farther, the big silvery tomb with the angel-borne canopy honors St. John of Nepomuk. Locals claim it has more than a ton of silver (for more on St. John of Nepomuk and his halo of stars, see here).

Just past the tomb, on the wall of the choir (on the right), is another finely carved, circa-1630 wood relief depicting an event that took place right here in St. Vitus: Protestant nobles trash the cathedral’s Catholic icons after their (short-lived) victory.

Ahead on the left, look up at the royal oratory, a box supported by busy late-Gothic, vine-like ribs. This private box, connected to the king’s apartment by a corridor, let the king attend Mass in his jammies. The underside of the balcony is morbidly decorated with dead vines and tree branches, suggesting the pessimism common in the late Gothic period, when religious wars and Ottoman invasions threatened the Czech lands.

• From here, walk 25 paces and look left through the crowds and door to see the richly decorated chapel containing the tomb of St. Wenceslas. Two roped-off doorways give visitors a look inside. The best view is from the second one, around the corner and to the left, in the transept.

Wenceslas Chapel: This fancy chapel is the historic heart of the church. It contains the tomb of St. Wenceslas, patron saint of the Czech nation; it’s where Bohemia’s kings were crowned; and it houses (but rarely displays) the Bohemian crown jewels. The chapel walls are paneled with big slabs of precious and semiprecious stones. The jewel-toned stained-glass windows (from the 1950s) admit a soft light. The chandelier is exceptional. The place feels medieval.

The tomb of St. Wenceslas is a colored-stone coffin topped with an ark. Above the chapel’s altar is a statue of Wenceslas, bearing a lance and a double-eagle shield. He’s flanked by (painted) angels and the four patron saints of the Czech people. Above Wenceslas are portraits of Charles IV (who built the current church) and his beautiful wife. On the wall to the left of the altar, frescoes depict the saint’s life, including the episode where angels arrive with crosses to arm the holy warrior. (For more on Wenceslas, see here.)

For centuries, Czech kings were crowned right here in front of Wenceslas’ red-draped coffin.

• Leave the cathedral, turn left (past the public WC), and survey the...

The obelisk was erected in 1928—a single piece of granite celebrating the 10th anniversary of the establishment of Czechoslovakia and commemorating the soldiers who fought for its independence. It was originally much taller, but broke in transit—an inauspicious start for a nation destined to last only 70 years.

From here, you get a great look at the sheer size of St. Vitus Cathedral and its fat green tower (325 feet tall). Up there is the Czech Republic’s biggest bell (16.5 tons, from 1549), nicknamed “Zikmund.” You can view the bell as you climb up the 287 steps of the tower to the observation deck at the top (buy ticket and enter near sculpture of St. George—a 1960s replica of the 13th-century original).

It’s easy to find the church’s Golden Gate (for centuries the cathedral’s main entry)—look for the glittering 14th-century mosaic of the Last Judgment. The modern, cosmopolitan, and ahead-of-his-time Charles IV commissioned this monumental decoration in 1370 in the Italian style. Jesus oversees the action, as some go to heaven and some go to hell. The Czech king and queen kneel directly beneath Jesus and six patron saints. On coronation day, royalty would walk under this arch, a reminder to them (and their subjects) that even those holding great power are not above God’s judgment. See the grilled windows above this entryway? That’s where the royal crown and national jewels are stashed.

Across from the Golden Gate, in the corner, notice the copper, scroll-like awning supported by bulls. This leads to a fine garden just below the castle. The stairway, garden, and other features around the castle were designed by the Slovene architect Jože Plečnik (see here). Around the turn of the 20th century, Prague was considered the cultural standard-bearer of the entire Slavic world—making this a particularly prestigious assignment.

• In the corner of the Third Courtyard, near the copper awning, is the...

The traditional seat of Czech power, this feels like a mostly empty historical shell. But its oversized Vladislav Hall—big enough for horseback jousting competitions or bustling markets—is impressive. The smaller, adjoining rooms called the “Czech Office” was the site of a famous defenestration—the Czech way of dealing with unwanted politicians: In 1618, angry Czech Protestant nobles poured into these rooms and threw the two Catholic governors out the window. An old law actually permits this act—called defenestration—which usually targets bad politicians. An old print on the glass panel shows the second of Prague’s many defenestrations. The two governors landed—fittingly—in a pile of horse manure. Even though they suffered only broken arms and bruised egos, this event kicked off the huge and lengthy Thirty Years’ War. The palace also comes with a balcony offering fine views of the surrounding hillsides, and assorted other royal portraits and bric-a-brac.

• The next sight requires the “Circuit A” ticket; if you don’t have one, skip down to the next stop.

Otherwise, as you exit the Royal Palace, hook left around the side of the building and backtrack a few steps uphill to find stairs leading down to...

For those wanting to dig deeper into the history of Prague and its castle, this exhibit features well-described historical artifacts from the very first Czechs through the imported Habsburg monarchy of the 17th century. As this is the main addition to the pricier “Circuit A” ticket, visit here only if you have a bigger-than-average appetite for history.

The oldest-feeling place at the castle, this atmospheric, dimly lit, stripped-down Romanesque chapel offers a subdued contrast to the big and bombastic spaces elsewhere. The church was founded by Wenceslas’ dad around 920, and the present structure dates from the 12th century. (Its Baroque facade came later.) Inside, the place is beautiful in its simplicity. Notice the characteristic thick walls and rounded arches. In those early years, building techniques were not yet advanced enough to use those arches for the ceiling—it’s made of wood instead.

This was the royal burial place before St. Vitus was built, so the tombs here contain the remains of the earliest Czech kings. Climb the stairs that frame either side of the altar to study the area around the apse. St. Wenceslas’ grandmother, Ludmila, was reburied here in 925. Her stone tomb is in the space just to the right of the altar. Inside the archway leading to her tomb, look for her portrait. Holding a branch and a book, she looks quite cultured for a 10th-century woman.

• As you exit, notice the building across the lane from the basilica (with the columned and curved portico)—this was Maria Theresa’s Institute for Noblewomen, created in the 1750s to empower and educate aristocratic but impoverished ladies.

Now continue walking downhill on that lane. You’ll see the basilica’s Romanesque nave and towers—a strong contrast to the pretty Baroque facade. Farther down, to the left, were the residences of soldiers and craftsmen, and to the right, tucked together, were the palaces of Catholic nobility who wanted both to be close to power and able to band together should the Protestants grab the upper hand. The next street on the left leads up to the popular Golden Lane. As you pass through the entry turnstiles, the crowds turn right, but don’t overlook the sights to your left (including a tiny café).

Named for the goldsmiths who likely worked here, this medieval merchant street retains its historic aura. When uncrowded, this atmospheric lane—lined with endearing little exhibits on the commerce and customs of a bygone era—is fun to explore. When busy, as it typically is, it’s miserable.

• Leaving the Castle Complex: Directly below the Golden Lane are two worthwhile sights that are not part of the castle complex—the Toy Museum and Lobkowicz Palace, both described later.

Exit the complex through a fortified door at the bottom end of the castle. A scenic rampart just below the lower gate offers a commanding view of the city. From there, you can head to the nearest Metro/tram station, Strahov Monastery, Little Quarter, or Castle Square.

To reach Malostranská Station: Follow the 700-some steps down the steep lane called Staré Zámecké Schody (“Old Castle Stairs”) directly back to the riverbank. Alternatively, for a gentler descent, start heading down the steep lane. About 40 yards below the castle exit, a gate on the left leads you through a scenic vineyard and past the recommended Villa Richter restaurants to the station.

To reach the top of the Little Quarter or Castle Square/Strahov Monastery, as you leave the castle gate, take a hard right and stroll through the long, delightful park (free, daily 10:00-18:00 or later, closed Nov-March). Along the way, notice the Modernist layout of the Na Valech Gardens, designed by the 1920s court architect, Jože Plečnik of Slovenia. Halfway through the long park is a viewpoint overlooking the terraced Pálffy Gardens (80 Kč, same hours as park). You can zigzag down through these gardens into the Little Quarter. Or, if you want to walk to Castle Square, continue uphill along the castle wall and through the garden to the square. You can hike up to the Strahov Monastery from here.

Extend your visit by dropping by a nobleman’s palace and a toy museum with an entire floor devoted to the Barbie doll. These sights require separate admission tickets; they’re not included in any castle tickets.

This palace, at the bottom of the castle complex, displays the private collection of a prominent Czech noble family, including paintings, ceramics, and musical scores. The Lobkowiczes’ property was confiscated twice in the 20th century: first by the Nazis at the beginning of World War II, and then by the communists in 1948. In 1990, William Lobkowicz, then a Boston investment banker, returned to Czechoslovakia to fight a legal battle to reclaim his family’s property and, eventually, to restore the castles and palaces to their former state. A conscientious host, William Lobkowicz himself narrates the delightful, included audioguide. While the National Gallery may seem a more logical choice for the art enthusiast, the obvious care that went into creating this museum, the collection’s variety, and the personal insight that it opens into the past and present of Czech nobility make the Lobkowicz worth an hour of your time.

Cost and Hours: 275 Kč, includes audioguide, daily 10:00-18:00, tel. 233-312-925, www.lobkowicz.cz.

Eating: The Lobkowicz Palace Café, by the exit, has a creative, cosmopolitan menu and stunning panoramic views of the city (daily 10:00-18:00). The charming young man you may see selling ice cream out front is William’s son, Will.

Across the street from Lobkowicz Palace, a courtyard and a long wooden staircase lead to two entertaining floors of old toys and dolls, thoughtfully described in English. You’ll see a century of teddy bears, some 19th-century model train sets, old Christmas decor, and an incredible Barbie collection. Find the buxom 1959 first edition, and you’ll understand why these capitalistic sirens of material discontent weren’t allowed here until 1989.

Cost and Hours: 70 Kč, 120-Kč family ticket, daily 9:30-17:30, WC next to entrance.

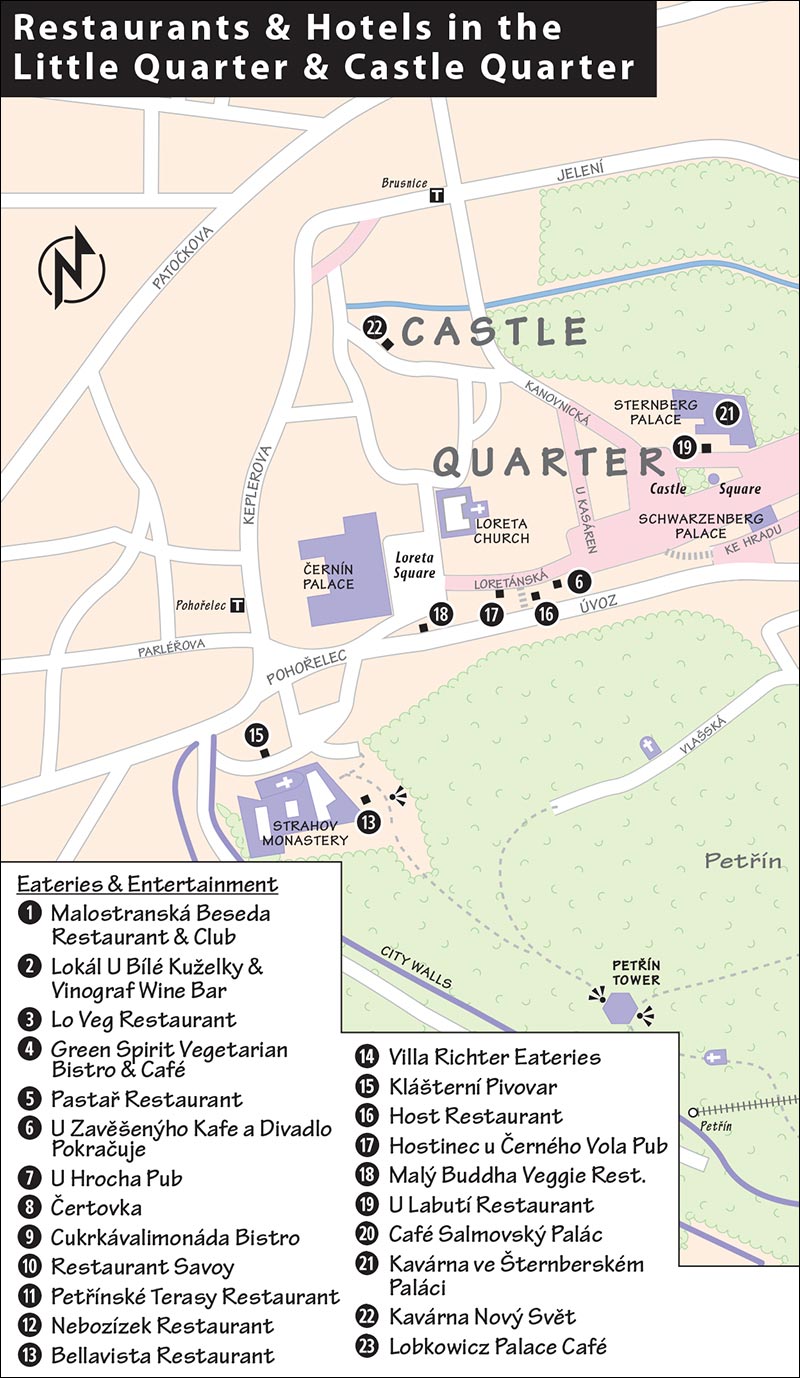

The Strahov Monastery, with its landmark domes, sits above the castle. Remember: If you’d like to combine the monastery with your castle visit, it’s easy to ride tram #22 up to the Pohořelec stop (beyond the castle), visit the monastery, enjoy the views, then walk 10 minutes down to Castle Square—passing Loreta Church on the way. (However, if you’re rushing to beat the morning crowds at the castle, it’s better to head straight for St. Vitus Cathedral in the castle complex, then backtrack to Strahov later.) To locate these sights, see the map on here.

Medieval monasteries were a mix of industry, agriculture, and education, as well as worship and theology. In its heyday, Strahov Monastery had a booming economy of its own, with vineyards, a brewery, and a sizable beer hall—all open once again. You can explore the monastery complex, check out the beautiful old library, and even enjoy a brew (no longer monk-made, but still refreshing).

Cost and Hours: Grounds—free and always open; library—100 Kč, extra 50 Kč to take photos—strictly enforced, daily 9:00-12:00 & 13:00-17:00, www.strahovskyklaster.cz. A pay WC is just to the right of the monastery entrance.

Visiting the Monastery and Library: The monastery’s main church, dedicated to the Assumption of St. Mary, is an originally Romanesque structure decorated by the monks in textbook Baroque (usually closed, but look through the gate inside the front door to see its interior). Notice the grand effect of the Baroque architecture—both rhythmic and theatric. Go ahead, inhale. That’s the scent of Baroque.

Buy your ticket in the adjacent building, and head up the stairs to the library, offering a peek at how enlightened thinkers in the 18th century influenced learning. The display cases in the library gift shop show off illuminated manuscripts, described in English. Some are in old Czech, but because the Enlightenment promoted the universality of knowledge (and Latin was the universal language of Europe’s educated elite), there was little place for regional dialects—therefore, few books here are in the Czech language.

Two rooms (seen only from the doors) are filled with 10th- to 17th-century books, shelved under elaborately painted ceilings. The theme of the first and bigger hall is philosophy, with the history of Western man’s pursuit of knowledge painted on the ceiling. The second hall—down a hallway lined with antique furniture—focuses on theology. As the Age of Enlightenment began to take hold in Europe at the end of the 18th century, monasteries still controlled the books. Notice the gilded, locked case containing the libri prohibiti (prohibited books) at the end of the room, above the mirror. Only the abbot had the key, and you had to have his blessing to read these books—by writers such as Nicolas Copernicus, Jan Hus, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and even including the French encyclopedia.

The hallway connecting the two library rooms was filled with cases illustrating the new practical approach to natural sciences. In the crowded area near the philosophy hall, find the dried-up elephant trunks (flanking the narwhal or unicorn horn) and one of the earliest models of an electricity generator.

Nearby: That hoppy smell you’re enjoying in front of the monastery is the recommended Klášterní Pivovar, where they brew beer just as monks have for centuries (in the little courtyard directly across from the library entrance; described on here).

Tucked in another courtyard across from the Strahov Monastery, the Museum of Miniatures (Muzeum Miniatur) displays 40 teeny exhibits—each under a microscope—crafted by an artist from a remote corner of Siberia. Yes, you could fit the entire museum in a carry-on-size suitcase, but good things sometimes come in very, very small packages—it’s fascinating to see minutiae such as a padlock on the leg of an ant (100 Kč, kids-50 Kč, daily 9:00-17:00, Strahovské Nádvoří 11, tel. 233-352-371).

Just below the monastery, don’t miss the garden terrace (look for the aptly named Bellavista Restaurant), with exquisite views over the domes and spires of Prague. The area just below the restaurant tables is free and open to visitors.

• After enjoying the views, head through the small hole in the wall near the Museum of Miniatures, and go down the street to Loretánská street. Turning right, follow Loretánská to the castle, by way of...

This church has been a hit with pilgrims for centuries, thanks to its dazzling bell tower, peaceful yet plush cloister, sparkling treasury, and much-venerated Holy House. In the middle of the cloister courtyard, you’ll find what’s considered by some pilgrims to be part of Mary’s actual home in Nazareth. You’ll also see one of Prague’s most beautiful Baroque churches, a fine treasury collection (upstairs), and—in a tiny chapel in one corner—“St. Bearded Woman,” the patron saint of unhappy marriages.

Cost and Hours: 150 Kč, daily April-Oct 9:00-17:00, Nov-March 9:30-16:00, audioguide-150 Kč, tel. 220-516-740, www.loreta.cz.

Nearby: The parking-lot square in front of the Loreta Church has a statue of Edvard Beneš, the second president of Czechoslovakia (in the 1930s and 1940s), who led the government-in-exile during the Nazi occupation. His forced relocation of Sudetenland Germans following World War II has left him with a controversial legacy; notice the slumping posture and look of worry on his face. (For more on Beneš, see the sidebar on here.)

Facing the church from across the square is the Černín Palace, a civic building that was the unfortunate site of a modern-day defenestration. In the spring of 1948, soon after the communists took over, an extremely popular Czechoslovak politician (Jan Masaryk, the son of the first president of Czechoslovakia) was found dead in this building’s courtyard, below the bathroom window—an apparent suicide. When the official secret-police files were unsealed after 1989, they revealed that Masaryk had been assassinated by Russian agents.

These minor sights, above Prague Castle, are only worth visiting if you get off tram #22 at Královský Letohrádek (the Royal Summer Palace is across the street from this stop, WC at gate).

This gift of love is like a Czech Taj Mahal, presented by Emperor Ferdinand I to his beloved Queen Anne. It’s the purest Renaissance building in town. You can’t go inside, but the building’s detailed reliefs are worth a close look.

• From here, set your sights on the cathedral’s lacy, black spires marking the castle’s entrance. Stroll through the...

Once the private grounds and residence (you’ll see the building) of the communist presidents, these were opened to the public with the coming of freedom under Václav Havel. Walk through these gardens (with lovely views of St. Vitus Cathedral) to the gate, which leads you over the moat and into Castle Square, the entrance to the vast castle complex.

Cost and Hours: Free, April-Oct daily 10:00-18:00, closed Nov-March.

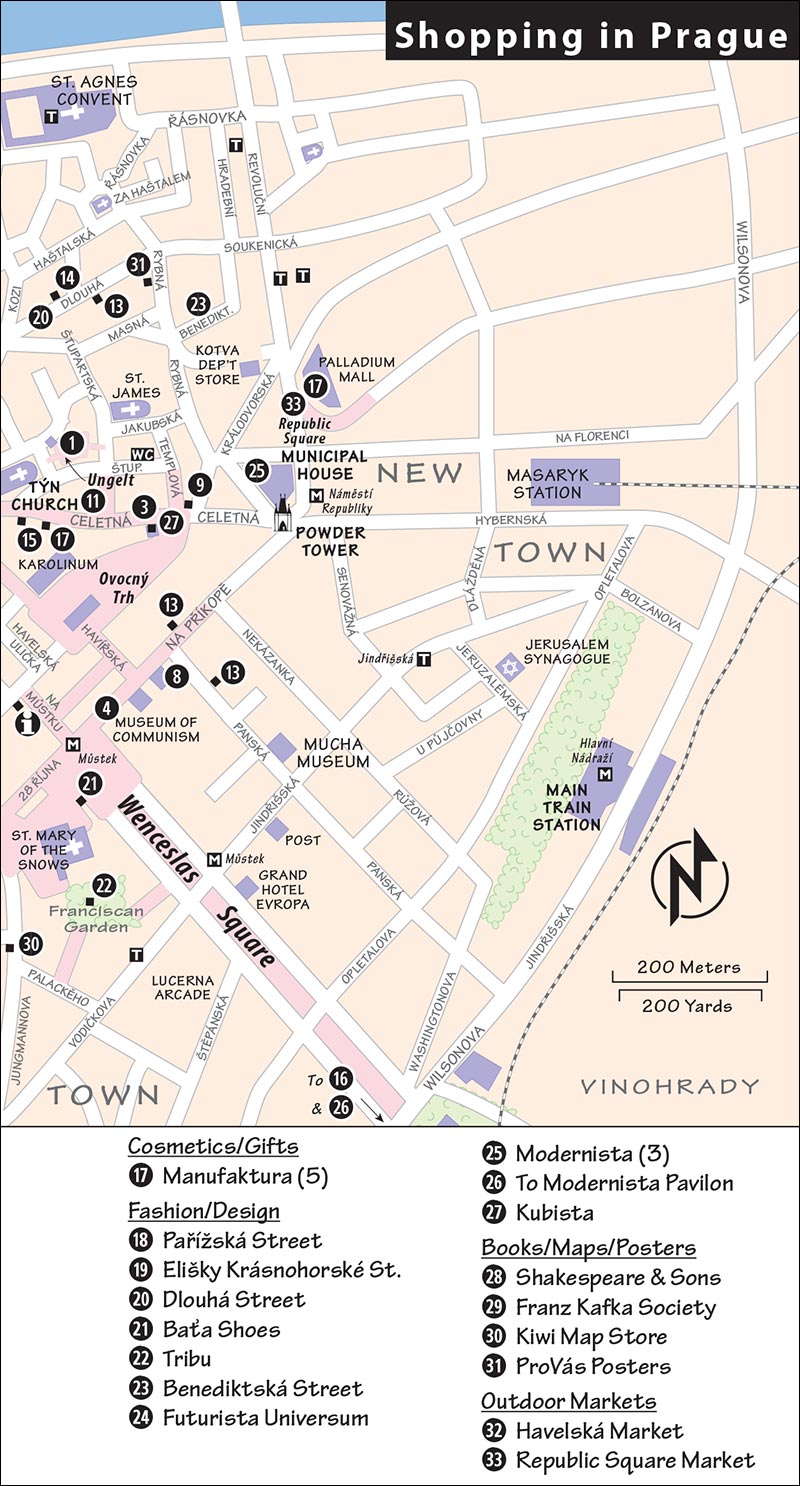

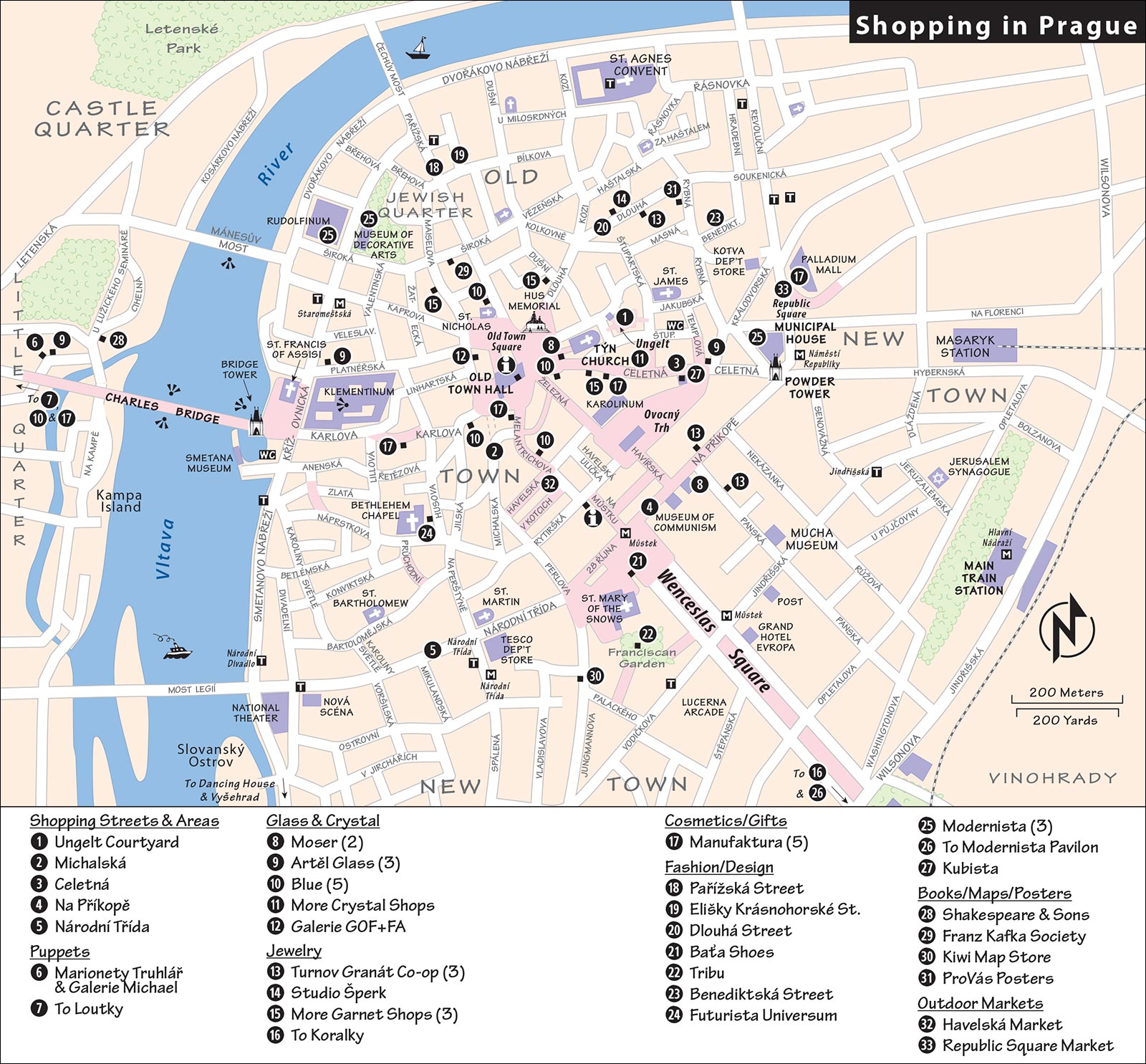

Prague’s entire Old Town seems designed to bring out the shopper in visitors. Puppets, glass, crystal, and garnets (deep-red gemstones) are traditional; these days, fashion and design (especially incorporating the city’s rich Art Nouveau heritage) are also big business. Most shops are open on weekdays from 9:00 until 17:00 or 18:00—and often longer, especially for tourist-oriented shops. Some close on Saturday afternoons and/or all day Sunday.

If you’d like to simply window-shop in the tourist zone, consider the following streets.

Ungelt, the courtyard tucked behind the Týn Church just off of the Old Town Square, is packed with touristy but decent-quality shops. Material has a fine selection of contemporary-style bead jewelry, and Botanicus is an excellent herbal cosmetics shop. Fajans Majolica has traditional blue-and-white Czech pottery and two stores sell marionettes: V Ungeltu and Hračky, Loutky (“Toys, Puppets”).

Michalská, a semihidden lane right in the thick of the tourist zone, has a variety of shops (from the Small Market Square/Malé Náměstí near the Astronomical Clock, go through the big stone gateway marked 459).

On Havelská street, you can browse the open-air Havelská Market, a touristy but enjoyable place to shop for inexpensive handicrafts and fresh produce (daily 9:00-18:00, two long blocks south of the Old Town Square; see here).

Celetná, exiting the Old Town Square to the right of Týn Church, is lined with big stores selling all the traditional Czech goodies. Tourists wander endlessly here, mesmerized by the window displays.

Na Příkopě, the mostly pedestrianized street following the former moat between the Old Town and the New Town, has the city center’s handiest lineup of modern shopping malls. The best is Slovanský Dům (“Slavic House,” at #22), where you’ll wander past a 10-screen multiplex deep into a world of classy restaurants and designer shops surrounding a peaceful, parklike inner courtyard. Černá Růže (“Black Rose,” at #12) has a great Japanese restaurant around a small garden; Moser’s flagship crystal showroom is also here. The Galerie Myslbek, directly across the street, has fancy stores in a space built to Prague’s scale. Na Příkopě street opens up into Republic Square (Náměstí Republiky)—boasting Prague’s biggest mall, Palladium, hidden behind a pink Neo-Romanesque facade. Across the square is the communist-era brown steel-and-glass 1980s department store Kotva (“Anchor”), an obsolete beast on the verge of extinction.

Národní Třída (National Street), which continues past Na Příkopě in the opposite direction (toward the river), is less touristy and lined with some inviting stores. Karlova, the tourist-clogged drag connecting the Old Town Square to the Charles Bridge, should be avoided entirely. Shops along here sell made-in-China trinkets at too-high prices to lazy and gullible tourists.

Czech Puppets: It takes a rare artist to turn pieces of wood into nimble puppets, and prices for the real deal can reach into the thousands of dollars. But given that puppets have a glorious past and vibrant present in the Czech Republic, even a simple jester, witch, or Pinocchio can make a thoughtful memento of your Czech adventure. You’ll see cheap trinket puppets at souvenir stands across town. Buying a higher-quality keepsake is more expensive (starting in the $100 range). Here are a few better options to consider:

Marionety Truhlář, near the Little Quarter end of Charles Bridge (U Lužického Semináře 5); Galerie Michael, just a few doors down (U Lužického Semináře 7, www.marionettesmichael.cz); the no-name loutky (“Puppets”) shop at the top of Nerudova (at #51, www.loutky.cz); and, in the Ungelt Courtyard, Hračky, Loutky (“Toys, Puppets”).

Glass and Crystal: Legally, to be called “crystal” (or “lead crystal”), it must contain at least 24 percent lead oxide, which lends the glass that special, prismatic sparkle. The lead also adds weight, makes the glass easier to cut, and produces a harmonious ringing when flicked. (“Crystal glass” has a smaller percentage of lead.)

Well-respected sources for Czech glass and crystal include Moser, the most famous Czech brand—and one of the most expensive (flagship store at the Černá Růže shopping mall at Na Příkopě 12, plus another branch on the Old Town Square www.moser-glass.com);

Artěl, with a small but eye-pleasing selection of Art Nouveau- and Art Deco-inspired glassware (for locations, see listing later, under “Art Nouveau Design Shops”); and Blue, a chain specializing in sleek, modern designs—many of them in the namesake hue (several locations, including Malé Náměstí 13, Pařížská 3, Melantrichova 6, Celetná 2, and Mostecká 24, and at the airport; www.bluepraha.cz). Celetná street is lined with touristy glass shops, some with a wide selection suitable for a surgical strike for a crystal souvenir.

For a unique, experiential take on Czech glass, visit Antonin Manto-Mrnka’s Galerie GOF+FA (on the Small Market Square at Malé Náměstí 6, www.mantogallery.com).

Bohemian Garnets (Granát): These blood-colored gemstones have unique refractive—some claim even curative—properties. If you buy garnet jewelry, shop around, use a reputable dealer, and ask for a certificate of authenticity to avoid buying a glass imitation (these are common). Of the many garnet shops in Prague’s shopping districts, Turnov Granát Co-op has the largest selection. It’s refreshingly unpretentious, with a vaguely retro-communist vibe (shops at Dlouhá 28, Panská 1, and inside the Pánská Pasáž at Na Příkopě 23; www.granat.eu). J. Drahoňovský’s Studio Šperk is a more upscale-feeling shop with more creative designs (Dlouhá 19, www.drahonovsky.cz). Additional shops specializing in Turnov garnets are at Dlouhá 1, Celetná 8, and Maiselova 3.

Costume Jewelry and Beads: You’ll see bižutérie (costume jewelry) advertised all over town. Round, glass beads—sometimes called Druk beads—are popular, and can range from large marble-sized beads to minuscule “seed beads.” The biggest producer of glass beads is Jablonex, from the town of Jablonec nad Nisou. A handy spot to check out some stylish, modern pieces is Material, in the Ungelt courtyard behind Týn Church. They have a fun selection of seed beads, as well as some finer pieces (www.i-material.com). Koralky, one of the best-supplied bead shops in Prague, is a bit farther out; take the Metro’s green line to the Jiřího z Poděbrad stop (Vinohradská 76, www.koralky.cz).

Organic Cosmetics and Handmade Gifts: Manufaktura is your classy, one-stop shop for good-quality Czech gifts, from organic cosmetics to handicrafts—all handmade in the Czech Republic. You’ll find many branch locations in Prague, including several near the Old Town Square (at Melantrichova 17, Celetná 12, and Karlova 26); at Republic Square (in the Palladium mall); near the Little Quarter end of the Charles Bridge (Mostecká 17); in the main train station; and even along Prague Castle’s Golden Lane (www.manufaktura.cz). Botanicus is similar but smaller, (in the Ungelt courtyard behind Týn Church, www.botanicus.cz).

Fashion and Design: Czechs have a unique sense of fashion. One popular trend is garments that are adorned with embroidery, leather, beads, hand-painted designs, or other flourishes—all handmade and therefore unique. Shops selling these come and go, and in many cases several small designers work together and share a boutique—look for an “atelier.” Vintage clothes are also as popular among young Czech hipsters as they are with their American counterparts.

The Jewish Quarter’s Pařížská street has the highest concentration of big-name international designers, but for something more local, focus on some of the side-streets that run parallel to Pařížská. One block over, Elišky Krásnohorské street has the most engaging lineup of unpretentious local fashion. A block farther east, more boutiques line Dušní street. A short walk away, Dlouhá street—which exits the Old Town Square near the Jan Hus statue—offers more Czech designers.

On and Near Wenceslas Square: Fashionistas are sometimes surprised to learn that the famous and well-respected Baťa shoe brand is not Italian, but Czech. Their seven-story flagship store, on Wenceslas Square (at #6), is nirvana for shoe lovers. Nearby, one of the pavilions inside the Franciscan Garden (hiding just off of Wenceslas Square) houses Tribu, a fun and youthful fashion boutique with clothes, jewelry, and other unique pieces (www.tribu.cz).

Funky Hipster Design: Benediktská, a tiny street tucked in a quiet corner of the Old Town, has a little cluster of creative boutiques.

Art Nouveau Design Shops: Prague is Europe’s best Art Nouveau city—and several shops give you a chance to take home some of that eye-pleasing style, in the form of glasswear, home decor, linens, posters, and other items. Artěl—a chain owned by an American (Karen Feldman) who fell in love with Prague and its unique sense of style—is thoughtfully curated. There are three locations (one directly behind the Municipal House at Celetná 29, and shops near either end of the Charles Bridge—on the Old Town side at Platnéřská 7, and on the Little Quarter side at U Lužického Semináře 7; www.artelglass.com). Other good design shops include Futurista Universum, (shares an entrance with the recommended Klub Architektů restaurant at Betlémské Náměstí 5a, www.futurista.cz), Modernista (downstairs inside the Municipal House, plus a flagship store in a sleek, gorgeously restored former train station in the Vinohrady neighborhood at Vinohradská 50, www.modernista.cz), and Kubista, in the House of the Black Madonna (Ovocný Trh 19, www.kubista.cz).

Try Shakespeare and Sons (with a big selection in the Little Quarter) or Franz Kafka Society (with a smaller selection in the Jewish Quarter), both open daily and described on here. Kiwi Map Store, near Wenceslas Square, is Prague’s best source for maps and travel guides (Jungmannova 23).

ProVás is a poster shop stocking a wide array of unique posters—originals, reprints, and lots of vintage ads from the 1920s (closed Sat-Sun, Rybná 21, www.agenturaprovas.cz).

What Not to Buy: Many Prague souvenir shops sell non-Czech (especially Russian) items to tourists who don’t know better. Amber may be pretty, but—considering it’s found along the Baltic Sea coast—obviously doesn’t originate from this landlocked country. Stacking dolls, fur hats, and vodka flasks also fall into this category.

Prague booms with live and inexpensive theater, classical music, jazz, and pop entertainment. Everything is listed in several monthly cultural events programs (free at TIs).

Buying Tickets: You’ll be tempted to gather fliers as you wander through town. Don’t bother. To really understand all your options (the street Mozarts are pushing only their own concerts), drop by a Via Musica box office. There are two: One is next to Týn Church on the Old Town Square (daily 10:30-19:30, tel. 224-826-969), and the other is in the Little Quarter across from the Church of St. Nicholas (daily 10:30-18:00, tel. 257-535-568). A posted event schedule clearly shows everything that’s playing today and tomorrow, including tourist concerts, Black Light Theater, and marionette shows, with photos of each venue and a map (www.viamusica.cz). If you don’t see a posted list of today’s events, just ask for it.

Ticketpro sells tickets for the serious concert venues and most music clubs (English-language reservations tel. 296-329-999, www.ticketpro.cz). Ticketpro has several outlets: at Rytířská 31 (daily 8:00-12:00 & 12:30-16:30, between Havelská Market and Estates Theater); in the Lucerna Arcade (daily 9:30-18:00, on Wenceslas Square, opposite Grand Hotel Evropa); and in the privately run Tourist Center at Rytířská 12 (Mon-Fri 11:00-19:00, closed Sat-Sun). As with most ticket box offices, you’ll pay about 30 Kč extra per ticket.

Dress Code: Locals dress up for the more “serious” concerts, opera, and ballet, but many tourists wear casual clothes—as long as you don’t show up in shorts, sneakers, or flip-flops, you’ll be fine.

A kind of mime/modern dance variety show, Black Light Theater has no language barrier and is, for some, more entertaining than a classical concert. Unique to Prague, Black Light Theater originated in the 1960s as a playful and mystifying theater of the absurd. These days, aficionados and critical visitors lament that it’s becoming a cheesy variety show, while others are uncomfortable with the sexual flavor of some acts. Still, it’s an unusual theater experience that many enjoy. Shows last about an hour and a half. Avoid the first four rows, which get you so close that it ruins the illusion. Each of these four theaters has its own spin on what Black Light is supposed to be. (The other Black Light theaters advertised around town aren’t as good.)

Ta Fantastika tries to be poetic, with haunting puppetry and a little artistic nudity, but it’s less “fun” than some of the others. Of these choices, it takes itself perhaps the most seriously (680 Kč, Aspects of Alice nightly at 18:00 and 21:30, reserved seating, near east end of Charles Bridge at Karlova 8, tel. 222-221-366, www.tafantastika.cz).

Image Theater has more mime and elements of the absurd, and tries to incorporate more dance along with the illusions. They offer the most diverse lineup of programs, including a “best of” and several short-term, themed shows—recent topics have been African safari and outer space. Some find Image’s shows to be a bit too slapsticky for their tastes (480 Kč, nightly at 20:00, open seating—arrive early to grab a good spot, just off Old Town Square at Pařížská 4, tel. 222-314-448, www.imagetheatre.cz).

Laterna Magika, in the big, glassy building next to the National Theater, mixes Black Light techniques with film projection, dance, and other elements into a multimedia performance that draws Czech audiences. Because the theater is used for other types of performances as well, this Black Light show is staged less frequently than some of the others—but if they have a performance while you’re in town, they’re well worth considering (680 Kč; Wonderful Circus, Legends of Magic, Graffiti; typically 3-4 nights a week at 20:00, tel. 224-931-482, www.laterna.cz).

Srnec Theater is an ensemble run by founder Jiří Srnec (credited with inventing the Black Light Theater concept in 1961) and his son. Fittingly, this is the most “back-to-basics” option—while narratively simplistic, it revels in the childlike, goofy wonder of the effects. Their primary show, Anthology, traces the development of the art over the past 50 years; they also plan additional shows in the future (380-680 Kč, generally weekly at 20:00, in the same courtyard as the Museum of Communism and the McDonald’s at Na Příkopě 10, mobile 774-574-475, www.srnectheatre.com).

Each day, six to eight classical concerts designed for tourists fill delightful Old World halls and churches with music of the crowd-pleasing sort: Vivaldi, Best of Mozart, Most Famous Arias, and works by the famous Czech composer Antonín Dvořák. Concerts typically cost 400-1,000 Kč, start anywhere from 13:00 to 21:00, and last about an hour. Typical venues include two buildings on the Little Quarter Square (the Church of St. Nicholas and the Prague Academy of Music in Liechtenstein Palace), the Klementinum’s Chapel of Mirrors, the Old Town Square (in a different Church of St. Nicholas), and the stunning Smetana Hall in the Municipal House. Musicians vary from excellent to amateurish.

To ensure a memorable venue and top-notch musicians, choose a concert in one of three places—the Municipal House’s Smetana Hall, the Rudolfinum, or the National Theater—featuring Prague’s finest ensembles (such as the Prague Symphony Orchestra or Czech Philharmonic).

The Prague Symphony Orchestra plays in the gorgeous Art Nouveau Municipal House. Their ticket office is on the right side of the building, on U Obecního Domu street opposite Hotel Paris (Mon-Fri 10:00-18:00, tel. 222-002-336, www.fok.cz). A smaller selection of tickets is sold in the information office inside the Municipal House.

The Czech Philharmonic performs in the classical Neo-Renaissance Rudolfinum in the Jewish Quarter. Their ticket office is on the right side of the Rudolfinum, under the stairs (250-1,000 Kč, open Mon-Fri 10:00-18:00, and until just before the show starts on concert days, on Palachovo Náměstí on the Old Town side of Mánes Bridge, tel. 227-059-352, www.ceskafilharmonie.cz).

Both orchestras perform in their home venues about five nights a month from September through June. Most other nights these spaces are rented to agencies that organize tourist concerts of varying quality for double the price. Check first whether your visit coincides with either ensemble’s performance.

You’ll find tickets for tourist concerts advertised and sold on the street in front of these buildings. Although the music may not be the finest, these concerts do allow you to experience music in one of Prague’s best venues on the night of your choice. This is especially worth considering if you want to enjoy classical music in the Municipal House when the Symphony Orchestra isn’t in town (but make sure your concert takes place in the building’s Smetana Hall rather than in the much smaller Grégr Hall).

A handy ticket office for the three following theaters is in the little square (Ovocný Trh) behind the Estates Theater, next to a pizzeria.

The National Theater (Národní Divadlo), on the New Town side of Legií Bridge, is best for opera and ballet. Enjoy its Neo-Renaissance interior (300-1,000 Kč, shows from 19:00, tel. 224-912-673, www.narodni-divadlo.cz).

The Estates Theater (Stavovské Divadlo) is where Mozart premiered and personally directed many of his most beloved works (see here). Don Giovanni, The Marriage of Figaro, and The Magic Flute are on the program a couple of times each month (800-1,400 Kč, shows from 20:00, between the Old Town Square and the New Town on a square called Ovocný Trh, tel. 224-214-339, www.narodni-divadlo.cz).

The State Opera (Státní Opera), formerly the German Theater, is less architecturally rewarding than the National Theater. Operas by non-Czech composers are typically performed here (400-1,200 Kč, at 19:00 or 20:00, 101 Wilsonova, on the busy street between the main train station and Wenceslas Square—see map on here, tel. 224-227-693, www.narodni-divadlo.cz).

Young locals keep Prague’s many music clubs in business. Most clubs—from rock to folk to jazz—are neighborhood institutions with decades of tradition, generally holding only 100-200 people. Most charge a cover for the music.

In the Old Town: Roxy, a few blocks from the Old Town Square, features live bands from outside the country twice a week—anything from Irish punk to Balkan brass—and experimental DJs other nights. (Dlouhá 33, www.roxy.cz).

Agharta Jazz Club, which showcases some of the best Czech and Eastern European jazz, is just steps off the Old Town Square in a cool Gothic cellar. (Železná 16, www.agharta.cz).

In the New Town: Lucerna Music Bar is popular for its ’80s and ’90s video parties on Friday and Saturday nights (Vodičkova 36—in the basement of Lucerna Arcade, www.musicbar.cz). The small Reduta Jazz Club launches you straight into the 1960s-era classic jazz scene (when jazz provided an escape for trapped freedom lovers in communist times). The top Czech jazzmen—Stivín and Koubková—regularly perform. President Bill Clinton once played the sax here (on Národní street next to Café Louvre, www.redutajazzclub.cz).

In the Little Quarter: Malostranská Beseda—with its tight, steamy, standing-room-only space—is the only club in the center with daily live performances (Malostranské Náměstí 21, see map on here, www.malostranska-beseda.cz).

Peak months for hotels in Prague are May, June, and September. Easter and New Year’s are the most crowded times, when prices are jacked up a bit. Here I’ve assigned rankings based on peak season pricing. But, if you’re traveling in July or August, you’ll find rates generally 15 percent lower, and from November through March, about 30 percent lower. For tips on hotel rates and deals, making reservations, and other accommodation options—including apartments and other short-term rentals—see here.

You’ll pay higher prices to stay in the Old Town, but for many travelers, the convenience is worth the expense. These places are all within a 10-minute walk of the Old Town Square.

$$$$ Hotel Metamorphis is a splurge, with solidly renovated rooms in Prague’s former caravanserai (hostel for foreign merchants in the 12th century). Its breakfast room is in a spacious medieval cellar with modern artwork. Some of the street-facing rooms, located above two popular bars, are noisy at night (Malá Štupartská 5, tel. 221-771-011, www.hotelmetamorphis.cz, hotel@metamorphis.cz).

$$$$ Hotel Maximilian is a sleek, mod, 71-room place with Art Deco black design; big, plush living rooms; and all the business services and comforts you’d expect in a four-star hotel. It faces a church on a perfect little square just a short walk from the action (Haštalská 14, tel. 225-303-111, www.maximilianhotel.com, reservation@maximilianhotel.com).

$$$$ Design Hotel Jewel Prague (U Klenotníka), with 11 modern, comfortable rooms in a plain building, is three blocks off the Old Town Square (RS%, no elevator, Rytířská 3, tel. 224-211-699, www.hoteljewelprague.com, info@jewelhotel.cz).

$$$ Brewery Hotel u Medvídků (“By the Bear Cubs”) has 43 comfortable rooms in a big, rustic, medieval shell with dark wood furniture. Upstairs, you’ll find lots of beams—or, if you’re not careful, they’ll find you (RS%, “historical” rooms cost slightly more, apartment available, Na Perštýně 7, tel. 224-211-916, www.umedvidku.cz, info@umedvidku.cz, manager Vladimír). The pension runs a popular beer-hall restaurant with live music most Fridays and Saturdays until 23:00—request an inside room for maximum peace.

$$ Green Garland Pension (U Zeleného Věnce), on a central cobbled lane, has a warm and personal feel rare for the Old Town. Located in a thick 14th-century building with open beams, it has a blond-hardwood charm decorated with a woman’s touch. The nine clean and simply furnished rooms are two and three floors up, with no elevator (RS%, family room, Řetězová 10, tel. 222-220-178, www.uzv.cz, pension@uzv.cz).

$$ Hotel Haštal is next to Hotel Maximilian (listed earlier) on the same quiet, hidden square in the Old Town. A popular hotel even back in the 1920s, this family-run place has been renovated to complement the neighborhood’s vibrant circa-1900 architecture. Its 31 rooms are comfortable and insulated against noise (RS%, free tea, coffee, and wine, air-con, Haštalská 16, tel. 222-314-335, www.hastal.com, info@hastal.com).

The first and third listings below are buried on quiet lanes deep in the Little Quarter, among cobbles, quaint restaurants, rummaging tourists, and embassy flags. Hotel Julián is a 10-minute walk up the river on a quiet and stately street, with none of the intense medieval cityscape of the others. For locations, see the map on here, unless otherwise noted.

$$$$ Vintage Design Hotel Sax’s 22 rooms are decorated in a retro, meet-the-Jetsons fashion. With a fruity atrium and a distinctly modern, stark feel, this is a stylish, no-nonsense place (RS%, air-con, elevator, free tea and pastries daily at 17:00, Jánský Vršek 3, tel. 257-531-268, www.sax.cz, hotel@sax.cz).

$$$ Hotel Julián is an oasis of professional, predictable decency in an untouristy neighborhood. Its 33 spacious, fresh, well-furnished rooms and big, homey public spaces hide behind a noble Neoclassical facade. The staff is friendly and helpful (RS%, family rooms, air-con, elevator, plush and inviting lobby, summer roof terrace, parking lot; Metro: Anděl, then take tram #6, #9, #12, or #20 to the left as you leave Metro station for two stops; Elišky Peškové 11, Praha 5, reservation tel. 257-311-150, www.hoteljulian.com, info@julian.cz). Free lockers and a shower are available for those needing a place to stay after checkout (while waiting for an overnight train, for example).

$$$ Dům u Velké Boty (“House at the Big Boot”), on a quiet square in front of the German Embassy, is the rare quintessential family hotel in Prague: homey, comfy, and extremely friendly. Charlotta, Jan, and their two sons treat every guest as a (thirsty) friend, and the wellspring of their stories never runs dry. Each of their 12 rooms is uniquely decorated, most in a tasteful, 19th-century Biedermeier style (RS%, cheaper rooms with shared bath, family rooms, cash only, children up to age 10 sleep free—toys provided, Vlašská 30, tel. 257-532-088, www.dumuvelkeboty.cz, info@dumuvelkeboty.cz). There’s no hotel sign on the house—look for the splendid geraniums that Jan nurtures in the windows.

$$ Residence Thunovská, just below the Italian embassy on a relatively quiet staircase leading up to the castle, rents six rooms in a house that once belonged to the Mannerist artist Bartholomeus Sprangler. The all-renovated rooms are historic and equipped with kitchenettes and Italian furniture. The original chimney that runs through the house is inscribed with the date 1577, and the rest of the house is not much younger. The manager, Dean, a soft-spoken American who married into Prague, treats his guests as trusted friends (RS%, breakfast extra—served in the next-door café, Thunovská 19, look for the Consulate of San Marino sign, reception open 9:00-19:00, otherwise on-call, tel. 257-531-189, mobile 721-855-880, www.prague-apartments.org, thunovska@volny.cz).

It’s tough to find a double for less than 2,500 Kč in the old center. But Prague has an abundance of fine hostels—each with a distinct personality, and each excellent in its own way for anyone wanting a cheap dorm bed or an extremely simple twin-bedded room for a reasonable price. For travelers seeking low-priced options, keep in mind that hostels are no longer the exclusive domain of backpackers. The first two hostels below are centrally located, but lack care and character; the last two are found in workaday neighborhoods and have atmospheric interiors.

¢ Old Prague Hostel is a small, well-worn place on the second and third floors of an apartment building on a back alley near the Powder Tower. The spacious rooms were once apartment bedrooms, so it feels less institutional than most hostels, but the staff can be indifferent and older travelers might feel a bit out of place. The TV lounge/breakfast room is a good hangout (private rooms available, in summer reserve 2 weeks ahead for doubles, a few days ahead for bunks; Benediktská 2, see map on here for location, tel. 224-829-058, www.oldpraguehostel.com, info@oldpraguehostel.com).

¢ Hostel Prague Týn—quiet, mature, and sterile—is hidden in a silent courtyard two blocks from the Old Town Square. The management is very aware of its valuable location, so they don’t have to bother being friendly (private rooms available, reserve one week ahead, Týnská 19, see map on here for location, tel. 224-808-301, www.hostelpraguetyn.com, info@hostelpraguetyn.com).

A big part of Prague’s charm is found in wandering aimlessly through the city’s winding old quarters, marveling at the architecture, watching the people, and sniffing out fun restaurants. In addition to meat-and-potatoes Czech cuisine, you’ll find trendy, student-oriented bars and lots of fine ethnic eateries. For ambience, the options include traditional, dark Czech beer halls; elegant Art Nouveau dining rooms; and hip, modern cafés.

Generally, if you walk just a few minutes away from the tourist flow, you’ll find better value, atmosphere, and service. The more touristy a place is, the more likely you’ll pay too much—either in inflated prices or because waiters pad the bill. It’s smart to closely examine your itemized bill and understand each line.

I’ve listed eating and drinking establishments by neighborhood. Most of the options—and highest prices—are in the Old Town. For a light meal, consider one of Prague’s many cafés (see here).

Unlike most European countries, the Czech Republic permits smoking in restaurants and cafés. I’ve noted those that are either more or less smoky than the norm. For general advice on eating and tipping, see here.

Fun, Touristy Neighborhoods: Several areas are pretty and well-situated for sightseeing, but lined only with touristy restaurants. While these places are not necessarily bad values, I’ve listed only a few of your many options—just survey the scene in these spots and choose whatever looks best. Kampa Square, just off the Charles Bridge, feels like a small-town square. Havelská Market is surrounded by colorful little eateries, any of which offer a nice perch for viewing the market scene while you munch. The massive Old Town Square is the place to nurse a drink or enjoy a meal while watching the tide of people, both tourists and locals, sweep back and forth. There’s often some event on this main square, and its many restaurants provide tasty and relaxing vantage points.

Traditional Czech Places: It’s getting difficult to find a truly Czech pub in the historic city center, as many cheap student pubs have been replaced by shops and hotels that make more money. Most Czechs no longer go to “traditional” eateries, preferring the cosmopolitan taste of the world to the mundane taste of sauerkraut. As a result, ancient institutions with “authentic” Czech ambience have become touristy—but they’re still great fun, a good value, and respected by locals. Expect wonderfully rustic spaces, smoke, surly service, and reasonably good, inexpensive food. Understand every line on your bill. I’ve listed several of these characteristically Czech eateries.

Dining with a View: For great views, consider these options, all described in detail in the following pages: Hotel u Prince’s terrace (rooftop dining above a fancy hotel, completely touristy but with awesome views); Villa Richter (next to Prague Castle, above Malostranská Metro stop); Bellavista Restaurant at the Strahov Monastery; Petřínské Terasy and Nebozízek (next to the funicular stop halfway up Petřín Hill); and Čertovka in the Little Quarter (superb views of the Charles Bridge).

Cheap-and-Cheery Sandwich Shops: All around town you’ll find modern little sandwich shops (like the Panería chain) offering inexpensive fresh-made sandwiches (grilled if you like), pastries, salads, and drinks. You can get the food to go, or eat inside at simple tables.

Groceries and Farmers Markets: Ask your hotelier for the location of the nearest grocery store; it’ll probably be small, stocked with what you need, and close by. Or check out the farmer-supplied grocery called Grunt, which offers lots of fresh products (in the Old Town at Národni 21).

Farmers markets crop up around the city and tantalize picnickers. Apart from vegetables, you’ll find quality cheeses, juices, cakes, coffee, and more (www.farmarsketrziste.cz). The most central and touristy is the Havelská Market in the Old Town (also has handicrafts, daily 9:00-18:00, see here). The most scenic is the Náplavka (“River Landing”) market on the Vltava embankment, just south of the Palacký Bridge; the original and biggest market is on Vítězné Náměstí at the Dejvická Metro stop (both Sat 8:00-14:00). A smaller farmers market enlivens the heart of the trendy Žižkov neighborhood on Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday mornings (at Metro stop Náměstí Jiřího z Poděbrad—you could combine a visit with a trip up the nearby Žižkov TV tower). And another is on Republic Square (Náměstí Republiky) from Tuesdays through Fridays, at the entrance to the Old Town (www.farmarsketrhyprahy1.cz).

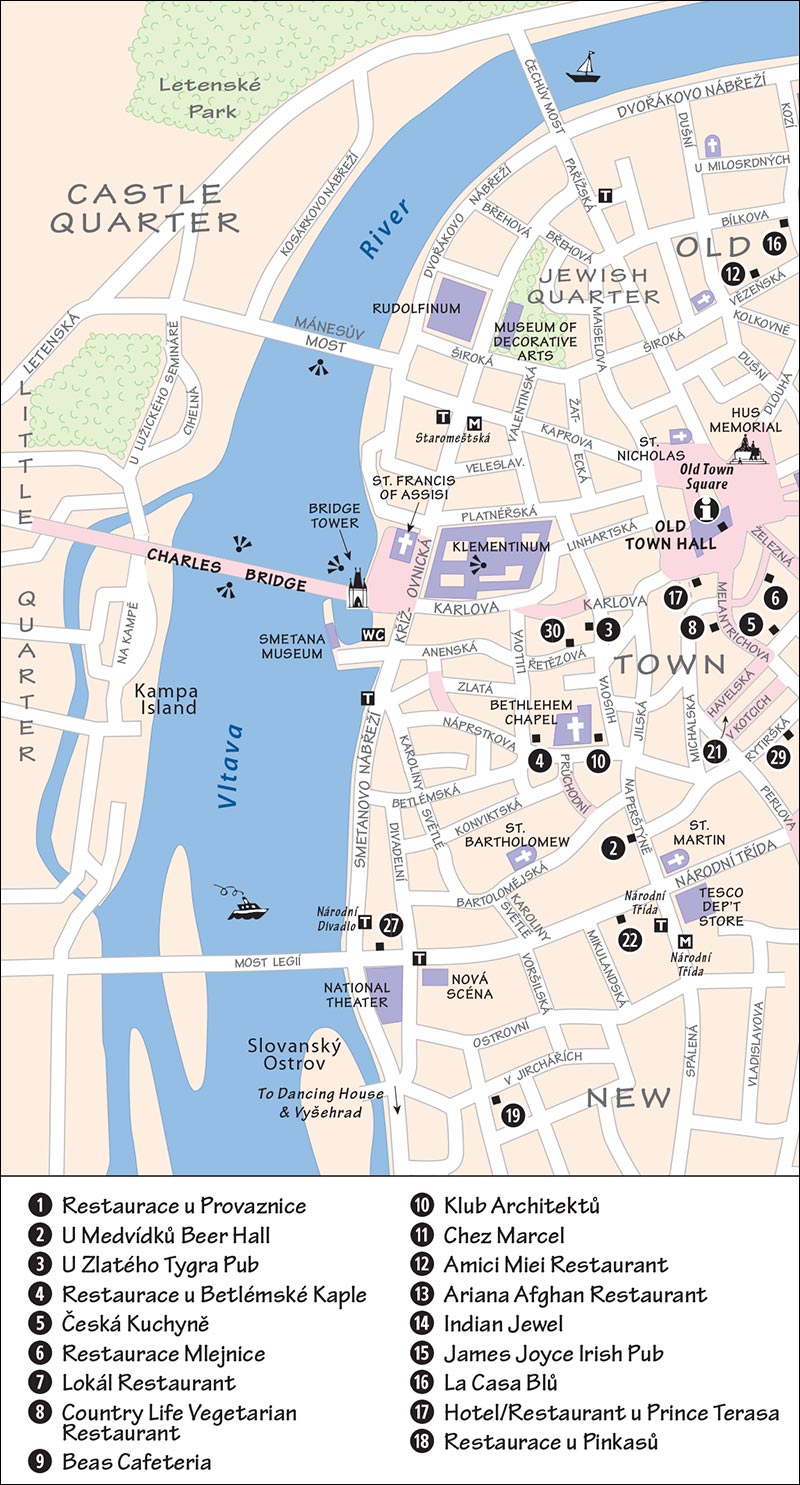

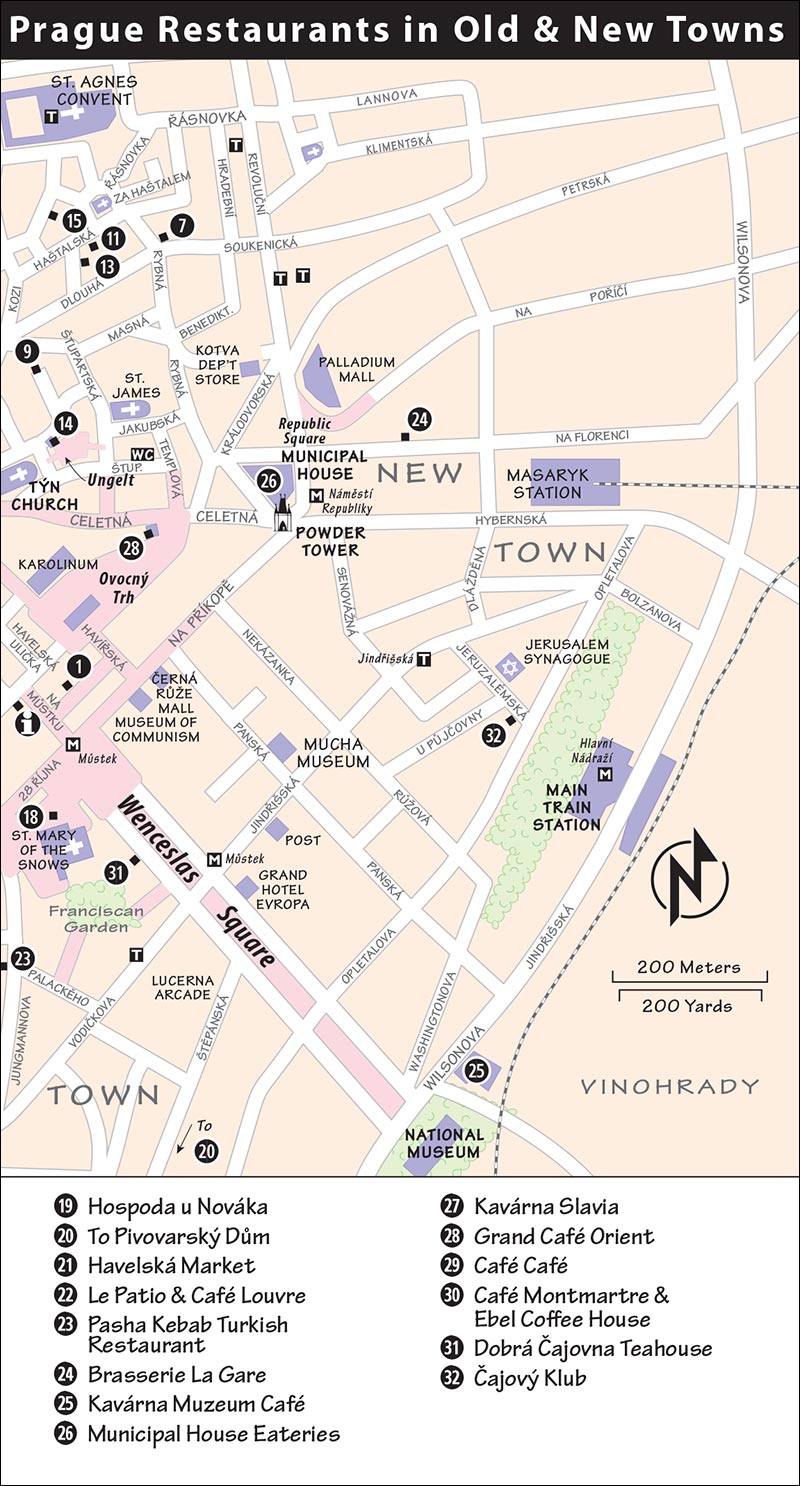

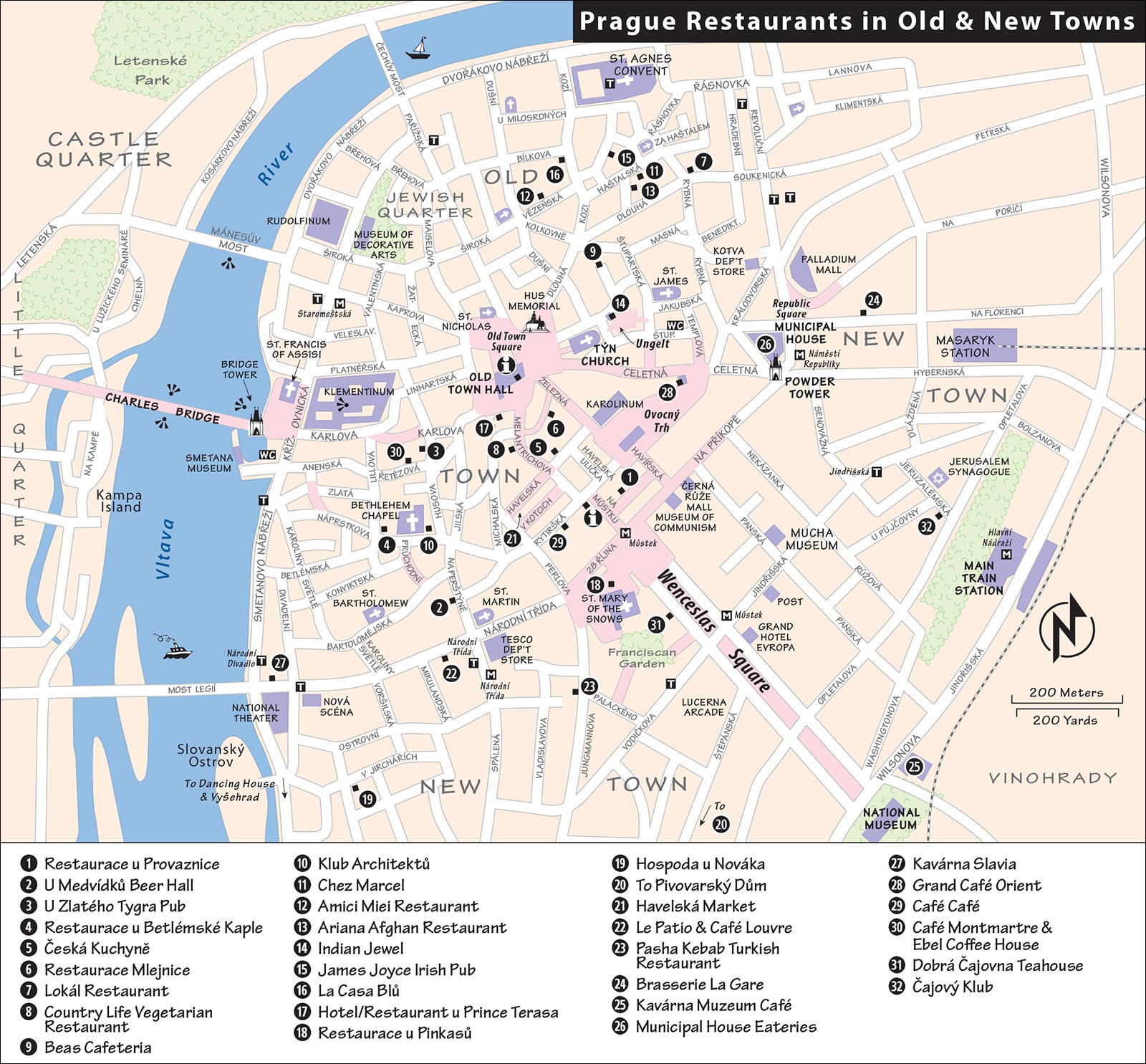

(See “Prague Restaurants in Old & New Towns” map, here.)

$$ Restaurace u Provaznice (“By the Ropemaker’s Wife”) has all the Czech classics, peppered with the story of a once-upon-a-time-faithful wife. (Check the menu for details of the gory story.) Natives congregate under bawdy frescoes for the famously good “pig leg” with horseradish and Czech mustard (daily 11:00-24:00, a block into the Old Town from the bottom of Wenceslas Square at Provaznická 3, tel. 224-232-528).

$$ U Medvídků (“By the Bear Cubs”) started out as a brewery in 1466 and is now a flagship beer hall of the Czech Budweiser. The one large room is bright, noisy, touristy, and a bit smoky (daily 11:30-23:00, a block toward Wenceslas Square from Bethlehem Square at Na Perštýně 7, tel. 224-211-916). The small beer bar next to the restaurant (daily 16:00 until late) is used by university students during emergencies—such as after most other pubs have closed.

$ U Zlatého Tygra (“By the Golden Tiger”) has long embodied the proverbial Czech pub, where beer turns strangers into kindred spirits, who cross the fuzzy line between memory and imagination as they tell their hilarious life stories to each other. Today, “The Tiger” is a buzzing shrine to one of its longtime regulars, the writer Bohumil Hrabal, whose fictions immortalize many of the colorful characters that once warmed the wooden benches here. Only regulars have reserved tables. To get a spot, arrive around opening time (daily 15:00-23:00, just south of Karlova at Husova 17, tel. 222-221-111).

$ Restaurace u Betlémské Kaple, behind Bethlehem Chapel, is not “ye olde” Czech. It has light wooden decor, cheap lunch deals, and fish specialties that attract natives and visitors in search of a good Czech bite for good Czech prices (daily 11:00-23:00, Betlémské Náměstí 2, tel. 222-221-639).

$ Česká Kuchyně (“Czech Kitchen”) is a blue-collar cafeteria serving steamy old Czech cuisine. It’s fast, practical, cheap, and traditional as can be. Pick up your tally sheet as you enter, grab a tray, point to whatever you’d like, and keep the paper to pay as you exit. It’s extremely cheap...unless you lose your paper. As you enter, you’ll come across serving stations in this order: salads, fruit dumplings and sweets, soups, main dishes, and finally, drinks (daily 9:00-20:00, very central, across from Havelská Market at Havelská 23, tel. 224-235-574).

$$ Restaurace Mlejnice (“The Mill”) is a fun little pub strewn with farm implements and happy eaters, located just out of the tourist crush two blocks from the Old Town Square. They serve hearty traditional and modern Czech plates. Reservations are smart in the evening (daily 11:00-24:00, between Melantrichova and Železná at Kožná 14, tel. 224-228-635, www.restaurace-mlejnice.cz/en).

$$ Lokál (“The Neighborhood Dump”) is a hit with residents for its good-quality Czech classics. Filling a long, arched space, the restaurant plays on customers’ nostalgia: The stark interior is a deliberate 1980s retro design, and the waiters have been instructed to be curt (but not impolite)—just as if they were serving in one of Prague’s notorious train station “dumps.” Reservations are smart (daily 11:00 until late, ask for English menu at the front by the tap, Dlouhá 33, tel. 222-316-265, www.lokal-dlouha.ambi.cz/en). The same group has a smaller branch, Lokál u Bílé Kuželky, in the Little Quarter (see listing later).

(See “Prague Restaurants in Old & New Towns” map, here.)

These hip and trendy places have a fun, youthful vibe.

$$ Country Life Vegetarian Restaurant is a bright, easy, nonsmoking cafeteria with a well-displayed buffet of salads and hot veggie dishes. It’s midway between the Old Town Square and the bottom of Wenceslas Square. They’re serious about their vegetarianism, serving only plant-based, unprocessed, and unrefined food. Its quiet dining area is elegant for a cafeteria, with a few tables outside in the courtyard (pay by weight, Sun-Thu 9:00-20:30, Fri 9:00-17:00, closed Sat, through courtyard at Melantrichova 15/Michalská 18, tel. 224-213-366).

$$ Beas Cafeteria, a little vegetarian restaurant, is ruled by a Punjabi chef. Diners grab a steel tray and scoop up whatever looks good, typically various choices of dal (lentils) and sabji (vegetables) with rice or chapati (pancakes). The food is sold by weight—you’ll likely spend 130 Kč for lunch. Tucked away in a courtyard behind the Týn Church, this place is popular with university students and young professionals (Mon-Fri 11:00-20:00, Sat-Sun from 12:00, Sun until 18:00, Týnská 19, mobile 608-035-727).

$$$ Klub Architektů, next to Bethlehem Chapel, is a modern hangout in a cave-like medieval cellar that also has straw-chair seating outside. The fun menu includes excellent original dishes, hearty salads, Moravian wines, and Slovak beer (daily 11:30-24:00, Betlémské Náměstí 169, tel. 224-248-878).

Beware that two popular Prague vegetarian restaurants, Lehká Hlava (“Clear Head”) and Maitrea (a.k.a. “Buddha of the Future”), are owned by Antonín Koláček, a former manager of a state-controlled brown coal company (and more recently a Buddhist philanthropist) who was convicted in 2013 in a Swiss court as the mastermind behind a 1990s fraudulent privatization scheme that robbed the country of at least three billion crowns.

(See “Prague Restaurants in Old & New Towns” map, here.)

Dlouhá, the wide street leading away from the Old Town Square behind the Jan Hus Memorial, is lined with ethnic restaurants catering mostly to cosmopolitan locals. Within a couple of blocks, you can eat your way around the world. From Dlouhá, wander the Rámová/Haštalská/Vězeňská area to survey a United Nations of eateries: You’ll find French (Chez Marcel at Haštalská 12); Italian (the expensive Amici Miei at Vězeňská 5, which prides itself on fresh pesci and frutti di mare); and Afghan (Ariana at Rámová 6).

These places deserve special consideration:

Indian: $$$ Indian Jewel, in the Ungelt courtyard behind the Týn Church, is the best place in Prague to find a full Indian menu that actually tastes Indian. Located in a pleasant, artfully restored courtyard, this is my choice for outdoor dining, with seriously executed sub-Continental classics and good-value lunch specials (daily specials, daily 11:00-23:00, Týn 6, tel. 222-310-156).

Irish: $ James Joyce Irish Pub may seem like a strange recommendation in Prague—home of some of the world’s best beer—but it has the kind of ambience that locals (and few tourists) seek out. Expats have favored this pub (formerly known as Molly Malone’s) for Guinness ever since the Velvet Revolution enabled the Celts to return to one of their homelands. Worn wooden floors, dingy walls, and the Irish manager transport you right into the heart of blue-collar Dublin—a popular place for young Czechs to seek jobs in the high-tech industry before the recession (daily 11:00 until late, U Obecního Dvora 4, tel. 224-818-851).

Latin American: $$ La Casa Blů, with cheap lunch specials, Mexican plates, Staropramen beer, and greenish mojitos, is your own little pueblo in Prague. It’s one of the last student bastions in the Old Town. Painted in warm oranges and reds, energized by upbeat music, and guarded by creatures from Mayan mythology, La Casa Blů attracts a fiesta of happy eaters and drinkers (Mon-Sat 11:00-23:00, Sun 14:00-23:00, nonsmoking, on the corner of Kozí and Bílkova, tel. 224-818-270).

(See “Prague’s Jewish Quarter” map, here.)

These eateries are well-placed to break up a demanding tour of the Jewish Quarter—all within two blocks of each other on or near Široká (see map on here). Also consider the nearby ethnic eateries listed above.

$$$ Kolkovna, the flagship restaurant of a chain allied with Pilsner Urquell, is big and woody yet modern, serving a fun mix of Czech and international cuisine—ribs, salads, cheese plates, and beer. It feels a tad formulaic...but not in a bad way (a bit overpriced, daily 11:00-24:00, across from Spanish Synagogue at V Kolkovně 8, tel. 224-819-701).

$$ Kolonial (“Bicycle Place”), across the street from the Pinkas Synagogue, has a modern interior playing on the bicycle theme, six beers on tap, and an imaginative menu drawing from Czech, French, Italian, and Spanish cuisine (daily specials, daily 9:00-24:00, Široká 6, tel. 224-818-322).

$ Restaurace u Knihovny (“By the Library”), situated steps away from the City and National libraries as well as the Pinkas Synagogue, is a favorite lunch spot for locals who work nearby. The cheap daily lunch specials consist of seven variations on traditional Czech themes. The service is friendly, and the stylish red-brick interior is warm (daily 11:00-23:00, nonsmoking at lunch, on the corner of Veleslavínova and Valentinská, mobile 732-835-876).

$$$ Dinitz Kosher Restaurant, around the corner from the Spanish Synagogue, is the most low-key and reasonably priced of the kosher restaurants in the Jewish Quarter (Shabbat meals by prepaid reservation only, Sun-Thu 11:30-22:30, Fri 11:30-14:30, Bílkova 12, tel. 222-244-000, www.dinitz.cz). For Shabbat meals, the fancier $$$ King Solomon Restaurant is a better value (Široká 8, tel. 224-818-752, www.kosher.cz).

(See “Prague Restaurants in Old & New Towns” map, here.)

The $$$$ Hotel u Prince Terasa, atop the five-star hotel facing the Astronomical Clock, is designed for foreign tourists. A sleek elevator takes you to the rooftop terrace, where every possible inch is used to serve good food (international with plenty of fish) from their open-air grill. The view is arguably the best in town—especially at sunset. The menu is a fun but overpriced mix, with photos that make ordering easy. Being in such a touristy spot, rude waiters are experts at nicking you with confusing menu charges; don’t be afraid to confirm exact prices before ordering. This place is also great for a drink at sunset or late at night (fine salads, daily until 24:00, brusque staff, outdoor heaters, Staroměstské Náměstí 29, tel. 224-213-807, no reservations possible).

(See “Prague Restaurants in Old & New Towns” map, here.)

$$ Restaurace u Pinkasů, founded in 1843, is known among locals as the first place to serve Pilsner beer. You can sit in its traditional interior, in front to watch the street action, or out back in a garden shaded by the Gothic buttresses of the St. Mary of the Snows Church. While the prices are straightforward, some of the waiters could win the rudest-service award (daily 9:00-24:00, near the bottom of Wenceslas Square, between the Old Town and New Town, Jungmannovo Náměstí 16, tel. 221-111-150).

$ Hospoda u Nováka, behind the National Theater, is emphatically Czech, with few tourists. It takes good care of its regulars (you’ll see the old monthly beer tabs in a rack just inside the door). Nostalgic communist-era signs are everywhere. During that time, pubs like this were close-knit communities where regulars escaped from the depression of daily life. Today, the U Nováka is a bright and smoky hangout where you can still happily curse whatever regime you happen to live under. While the English menu lists the well-executed Czech classics, it doesn’t list the cheap daily specials—ask (daily 10:00-23:00, V Jirchářích 2, tel. 224-930-639).

$$ Pivovarský Dům (“The Brewhouse”), on the corner of Ječná and Lípová, is popular with locals for its rare variety of fresh beers (yeast, wheat, and fruit-flavored), fine classic Czech dishes, and an inviting interior that mixes traditional and modern (daily 11:00-23:00, reservations recommended in the evenings, variety of beer mugs sold; walk up Štěpánská street from Wenceslas Square for 10 minutes, or take tram #22 for two stops from Národní to Štěpánská; Lípová 15, tel. 296-216-666, www.pivovarskydum.com).

(See “Prague Restaurants in Old & New Towns” map, here.)