Map: Prague Public Transportation

Sights in the Old Town (Staré Město)

NORTH OF THE OLD TOWN SQUARE, NEAR THE RIVER

Sights in the New Town (Nové Město)

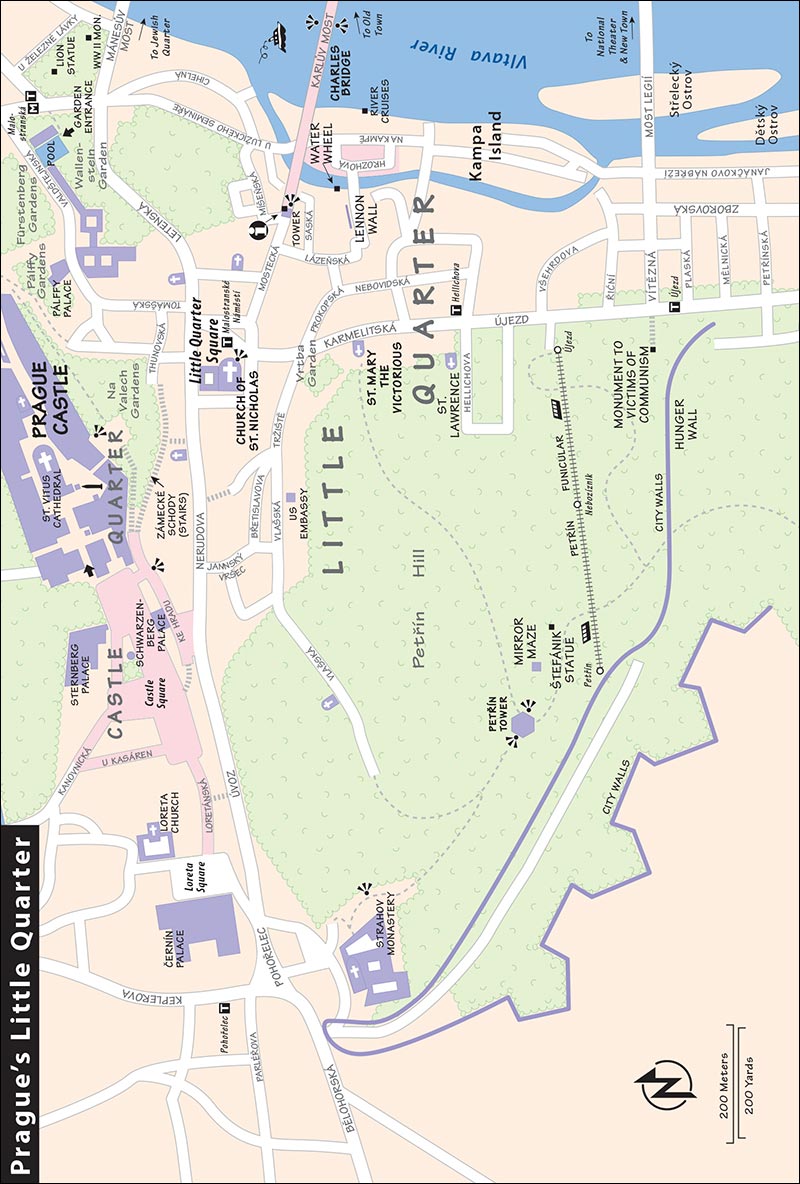

Sights in the Little Quarter (Malá Strana)

BETWEEN CHARLES BRIDGE AND LITTLE QUARTER SQUARE

ON OR NEAR LITTLE QUARTER SQUARE

SOUTH OF LITTLE QUARTER SQUARE

Sights in the Castle Quarter (Hradčany)

SHOPPING STREETS IN THE CENTER

BOOKS, MAPS, POSTERS, AND MUSIC

Map: Hotels in Prague’s Old Town

UNDER THE CASTLE, IN THE LITTLE QUARTER

Map: Prague Restaurants in Old & New Towns

Map: Restaurants & Hotels in the Little Quarter & Castle Quarter

MAIN TRAIN STATION (HLAVNÍ NÁDRAŽÍ)

Few cities can match Prague’s over-the-top romance, evocative Old World charm...and tourist crowds. Prague is equal parts historic and fun. No other place in Europe has become popular so quickly. And for good reason: Prague—the only Central European capital to escape the large-scale bombing of the last century’s wars—is one of Europe’s best-preserved cities. It’s filled with sumptuous Art Nouveau facades, offers tons of cheap Mozart and Vivaldi concerts, and brews some of the best beer in Europe.

Prague is a photographer’s delight. You’ll wind through walkable neighborhoods, past statues of bishops and pastel facades adorned with gables, balconies, lanterns, and a zillion little architectural details. Prague itself seems a work of art. Besides its medieval and Baroque look, it’s a world of willowy Art Nouveau paintings and architecture. You’ll also see rich remnants of its strong Jewish heritage and stark reminders of the communist era. And you’ll meet an entrepreneurial mix of locals and expats, each with a brilliant scheme of how to make money in the tourist trade.

Escape the crowds into the back lanes and pretend you’re strolling through the 18th century. Duck into pubs to enjoy the hearty food and good pilsner beer, and tour museums packed with fine art. Delve into one of Europe’s top stops.

A few days in Prague is plenty of time to get a solid feel for the city and enjoy some side-trips. If you’re in a rush, you’ll need a minimum of two full days (with three nights, or two nights and a night train) for a good introduction to the city. Keep in mind that Jewish Quarter sights close on Saturday and Jewish holidays. Some museums, mainly in the Old Town, are closed on Monday.

Here’s my plan for fully experiencing Prague in two days. With more time, I’ve offered more suggestions. Split your nights between beer halls, live music, or Black Light Theater.

| 9:00 | Take my Prague Old Town Walk to get oriented to the city’s core. Along the way, enter some of the sights (including the Municipal House) and climb at least one of the old towers—at the Old Town Hall, or at either end of the Charles Bridge—to enjoy the view. |

| 13:00 | Have lunch either in the Old Town or Little Quarter. Explore the Little Quarter (Kampa Island, Lennon Wall, Little Quarter Square). |

| 15:00 | Explore the Jewish Quarter. |

| 8:00 | Get an early start from your hotel, and zip up to Prague Castle on the tram. Be at St. Vitus Cathedral when it opens at 9:00, then visit the rest of the castle sights. |

| 11:00 | As you leave the castle, tour the Lobkowicz Palace. |

| 12:00 | Have lunch in the Little Quarter, below the castle. |

| 13:00 | Visit Wenceslas Square, and tour the Mucha Museum or the Municipal House (if you didn’t visit it already) to enjoy some Art Nouveau. |

| 16:30 | Squeeze in one more museum—perhaps the Museum of Medieval Art or the Museum of Communism. |

Note: If you’d rather sleep in today, flip this plan—visit Wenceslas Square, the Mucha Museum, or Municipal House; then tram up to the castle in the early afternoon (by about 14:00), as the crowds disperse.

With more time, fit in additional museums that interest you. If you have at least four days, Prague has a variety of worthwhile day trips at its doorstep. I’d prioritize Kutná Hora (delightful small town with gorgeous cathedral and famous bone church), the Terezín Memorial (Holocaust history), and/or Konopiště Castle (with a lived-in Habsburg interior). Český Krumlov is another wonderful destination, but it’s a bit far for a day trip—it’s much better as an overnight.

Residents call their town “Praha” (PRAH-hah). It’s big, with about 1.3 million people (swelling to 2 million in the metropolitan area). But during a quick visit, you’ll focus on its relatively compact old center.

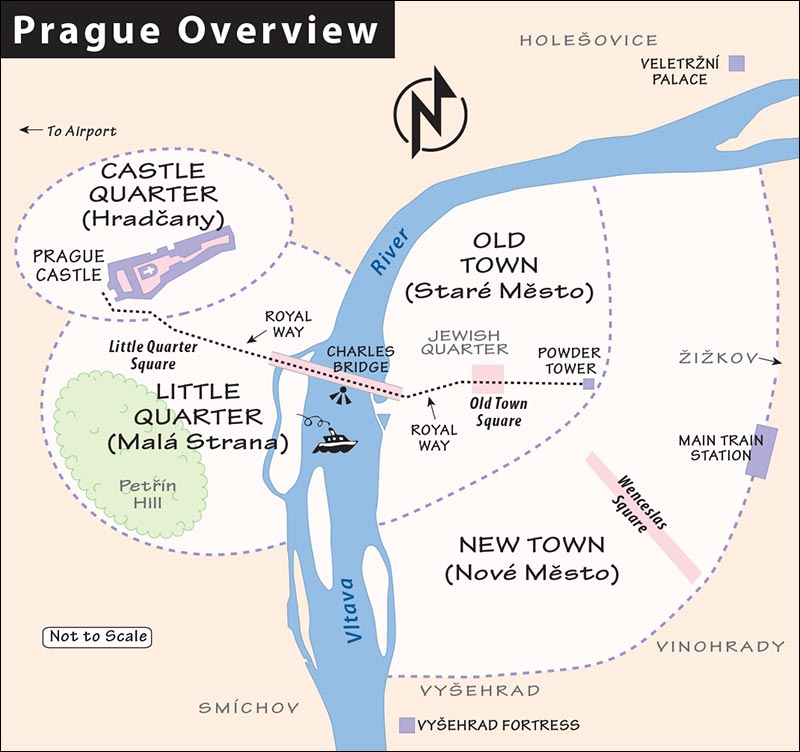

The Vltava River divides the city in two. East of the river are the Old Town and New Town, the main train station, and most of the recommended hotels. To the west of the river is Prague Castle, and below that, the sleepy Little Quarter. Connecting the two halves are several bridges, including the landmark Charles Bridge.

Think of Prague as a collection of neighborhoods. In fact, until about 1800, Prague actually was four distinct towns with four town squares, all separated by fortified walls. Each town had a unique character, drawn from the personality of its first settlers. Today, much of Prague’s charm survives in the distinct spirit of these towns.

Old Town (Staré Město): Nestled in the bend of the river, this is the historic core, where most tourists spend their time. It’s pedestrian-friendly, with small winding streets, old buildings, shops, and beer halls and cafés. In the center sits the charming Old Town Square. Slicing east-west through the Old Town is the main pedestrian axis, along Celetná and Karlova streets.

Within the Old Town, tucked closest to the river, is the Jewish Quarter (Josefov), a several-block area with a high concentration of old synagogues and sights from Prague’s deep Jewish heritage. It also holds the city’s glitziest shopping area (with big-name international designers filling gorgeously restored Art Nouveau buildings).

New Town (Nové Město): Stretching south from the Old Town is the long, broad expanse of Wenceslas Square, marking the center of the New Town. The New Town, shaped like a piece of elbow macaroni, hugs the edge of the Old Town—cutting a swath from riverbank to riverbank. As the name implies, it’s relatively new (“only” 600 years old). It’s the neighborhood for modern buildings, fancy department stores, and a few communist-era sights.

Castle Quarter (Hradčany): High atop a hill on the west side of the river stands the massive complex of Prague Castle, marked by the spires of St. Vitus Cathedral. For a thousand years, this has been the neighborhood of Czech rulers (including today’s president and foreign minister). Consequently, the surrounding area is noble and leafy, with high art and grand buildings, little commerce, and few pubs.

Little Quarter (Malá Strana): Nestled at the foot of Castle Hill is this pleasant former town of fine palaces and gardens (and a few minor sights). This is Prague’s diplomatic neighborhood, made to feel elegant by stately embassies, but lacking some of the funky personality of the Old Town.

Cutting through the towns—from the Powder Tower through the Old Town, crossing the Charles Bridge, and winding up to St. Vitus Cathedral—is the Royal Way (Královská Cesta), the ancient path of coronation processions. Today, this city spine (the modern streets of Celetná, Karlova, and Nerudova) is marred by tacky trinket shops and jammed by tour groups—explore beyond it if you want to see the real Prague.

TIs are at several key locations, including on the Old Town Square (in the Old Town Hall, just to the left of the Astronomical Clock; Easter-Oct Mon-Fri 9:00-19:00, Sat-Sun 9:00-18:00; Nov-Easter Mon-Fri 9:00-18:00, Sat-Sun 9:00-17:00); on the castle side of Charles Bridge (Easter-Oct daily 10:00-18:00, closed Nov-Easter); and in the Old Town, around the corner from Havelská Market (at Rytířská 31, April-Oct Mon-Sat 9:00-19:00, closed Nov-March). For general tourist information in English, dial 221-714-444 (Mon-Fri 8:00-19:00), or check the useful TI website: www.prague.eu.

The TIs offer maps, a helpful transit guide, and information on guided walks and bus tours. They can book local guides, concerts, and occasionally hotel rooms.

Monthly event guides—all of them packed with ads—include the Prague Guide (29 Kč), Prague This Month (free), and Heart of Europe (free, summer only).

Prague Card: This pricey sightseeing pass covers public transit (including the airport bus); admission or discounts to a number of sights (including a few biggies—such as Prague Castle and Jewish Quarter sights); a free bus tour and river cruise; and discounts to other attractions, including some concerts and guided tours. For most travelers, it’s not worth the steep cost (e.g., €48/2 days); check what’s included and do the math before you buy (pick up a brochure at the TI, or use the calculator feature at www.praguecard.com).

Prague has multiple train stations, but most visitors arrive at the main train station (Hlavní Nádraží), on the eastern edge of downtown—a 20-minute walk, short taxi ride, or bus ride to the Old Town Square and many of my recommended hotels. Prague’s Václav Havel Airport—12 miles from downtown—is easily connected to the city center by public bus, airport bus, minibus shuttle, and taxis. For details on all of these options, see here.

Exchange Rate: 25 Kč = about $1

Country Calling Code: 420 (see here for dialing instructions)

Rip-Offs: There’s no particular risk of violent crime in Prague, but—as in any heavily touristed city—naive tourists can get taken by con artists. Most scams fall into the category of being charged a two-scoop price for one scoop of ice cream, having extra items appear on your restaurant bill, or not getting the correct change. Jaded salesclerks in the tourist zone know that the 25-to-1 exchange rate mystifies American visitors, and may try to take advantage of your carelessness. Any time you pay for something, make a careful mental note of how much it costs, how much you’re handing over, and how much you expect back. Count your change. Beware the “slow count,” where clerks give back part of your change, then pause...hoping you’ll think they’re done and walk away. Wait until you get all the money you’re due. Plainclothes policemen “looking for counterfeit money” are con artists—ask to see their badges and they’ll shrink away.

Pickpockets: They’re abundant in Prague. They can be little children or adults dressed as professionals—sometimes even as tourists with jackets draped over their arms to disguise busy fingers. Thieves work crowded and touristy places in teams—for example, they might create a commotion at the door to a Metro or tram car. Keep your wits about you, assume any big distraction is a smokescreen for theft, and wear a money belt. All of this can sound intimidating, but Prague is safe. Simply stay alert.

Medical Help: A 24-hour pharmacy is at Palackého 5 (a block from Wenceslas Square, tel. 224-946-982). For above-standard assistance in English (including dental care), consider the top-quality Hospital Na Homolce (less than 1,000 Kč for an appointment, daily 8:00-16:00, call 252-922-146, for after-hours emergencies call 257-211-111; bus #167 from Anděl Metro station, Roentgenova 2, Praha 5). The Canadian Medical Care Center is a small, private clinic with an English-speaking Czech staff at Veleslavínská 1 in Praha 6 (appointment—3,000 Kč, house call—4,500 Kč, halfway between the city and the airport, tel. 235-360-133, after-hours emergency tel. 724-300-301).

Sightseeing Tips: The Museum of Medieval Art is closed on Mondays, and Jewish Quarter sights are closed on Saturdays. St. Vitus Cathedral at Prague Castle is closed Sunday morning for Mass.

Bookstores: Shakespeare and Sons is a friendly English-language bookstore with a wide selection of translations from Czech, the latest publications, and a reading space downstairs overlooking a river channel (daily 11:00-19:00, one block from Charles Bridge on Little Quarter side at U Lužického Semináře 10, tel. 257-531-894, www.shakes.cz). In the heart of the Jewish Quarter, the Franz Kafka Society has a fine little bookstore with a thoughtfully curated shelf of Czech lit in English translation—from Kafka to Švejk to tales of the Little Mole (daily 10:00-18:00, Široká 14, tel. 224-227-452).

Maps: A good map of Prague is essential. For ease of navigation, look for one with trams and Metro lines marked, and tiny sketches of the sights (30-70 Kč; sold at kiosks, exchange windows, and tobacco stands). The Kartografie Praha city map, which shows all the tram lines and major landmarks, also includes a castle diagram and a street index. It comes in two versions: 1:15,000 covers the city center (good enough for most visitors), and 1:25,000 includes the whole city (worthwhile if you’re sleeping in the suburbs).

Also consider getting a mapping app for your smartphone, which uses GPS to pinpoint your location. To avoid data-roaming charges, look for an offline map that can be downloaded in its entirety, such as those offered by City Maps 2Go (searchable offline).

Laundry: A full-service laundry near most of the recommended hotels is at Karolíny Světlé 11 (200 Kč/8-pound load, wash and dry in 3 hours, Mon-Fri 7:30-19:00, closed Sat-Sun, 200 yards from Charles Bridge on Old Town side, mobile 721-030-446); another laundry is at Rybná 27 (290 Kč/8-pound load, same-day pickup, Mon-Fri 7:00 or 8:00-18:00, closed Sat-Sun, tel. 224-812-641). Prague Andy’s Laundromat offers both self- and full-service (self-service-160 Kč/load, full service-300 Kč/load—weekdays only, free Internet access, daily 8:00-20:00, near Náměstí Míru Metro stop at Korunní 14, Praha 2, mobile 723-112-693, www.praguelaundromat.cz).

Bike Rental: Prague has improved its network of bike paths, making bicycles a feasible option for exploring the center of the town and beyond (see http://mapa.prahounakole.cz for a map). Two bike-rental shops are located near the Old Town Square: Praha Bike (daily 9:00-22:00, Dlouhá 24, mobile 732-388-880, www.prahabike.cz) and City Bike (daily 9:00-19:00, Králodvorská 5, mobile 776-180-284, www.citybike-prague.com). They rent bikes for about 300 Kč for two hours or 500 Kč a day (1,500-Kč deposit), and also organize guided bike tours. Another shop offers electric bikes (590 Kč/half-day, 890 Kč/day, April-Oct daily 9:00-19:00, tours available, just above American Embassy in Little Quarter at Vlašská 15, mobile 604-474-546, www.ilikeebike.com).

Car Rental: You won’t want or need to drive within compact Prague, but a car can be handy for exploring the countryside. All the biggies have offices in Prague (check each company’s website, or ask at the TI).

Travel Service and Tours: Magic Praha is a tiny travel service run by Lída Jánská. A Jill-of-all-trades, she can help with accommodations and transfers throughout the Czech Republic, as well as private tours and side-trips to historic towns (mobile 604-207-225, www.magicpraha.cz, magicpraha@magicpraha.cz).

You can walk nearly everywhere. Brown street signs (in Czech, but with helpful little icons) direct you to tourist landmarks. For a sense of scale, the walk from the Old Town Square to the Charles Bridge takes less than 10 minutes (depending on crowds).

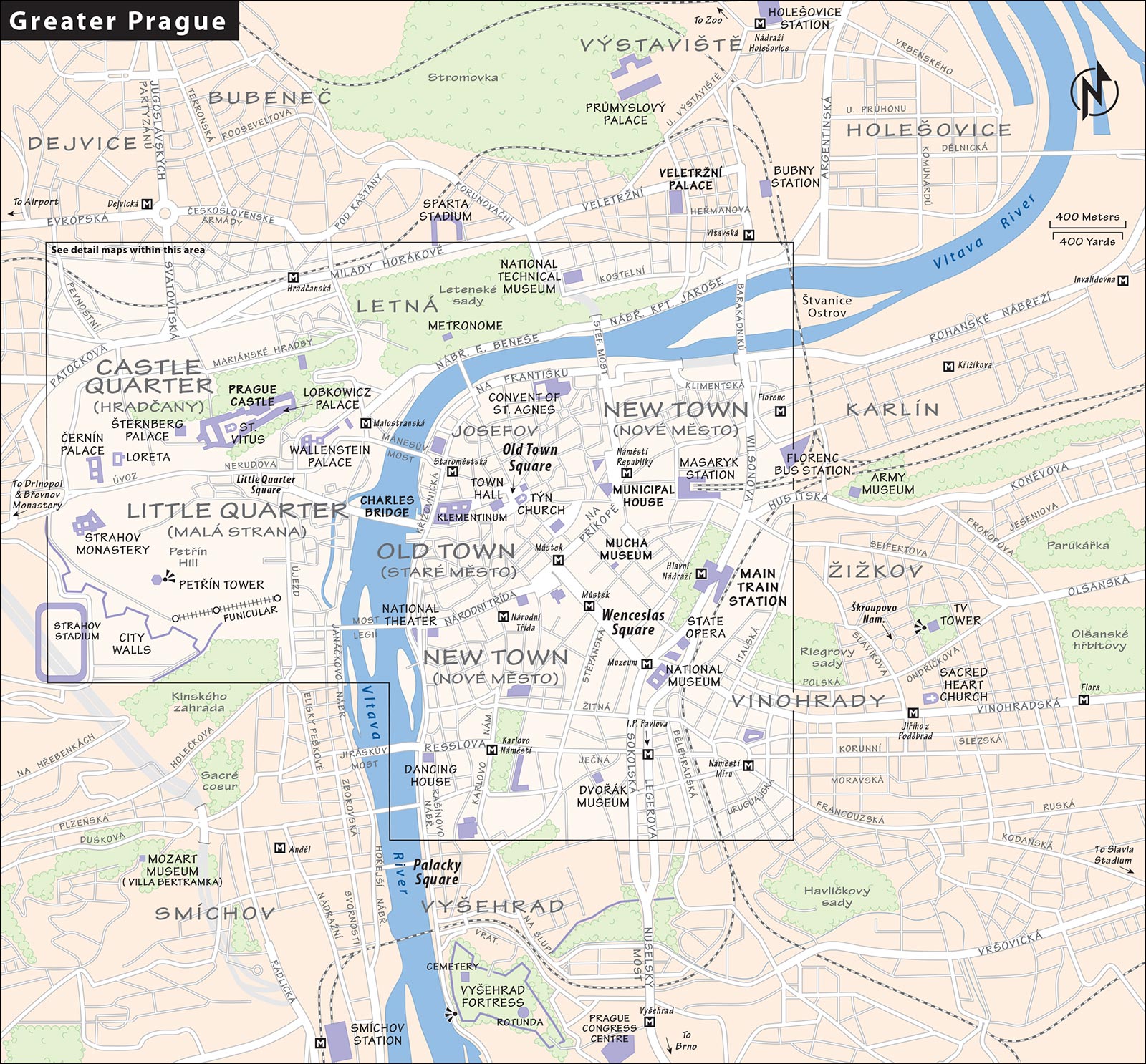

Still, it’s worth figuring out the public transportation system, which helps you reach farther-flung sights such as Prague Castle. The Metro is slick, the trams fun, and the taxis quick and easy. Prague’s tram system is especially wonderful—trams rumble by frequently and take you just about anywhere. Be bold and you’ll swing through Prague like Tarzan. For details, pick up a transit guide at the TI. City maps show the Metro, tram, and bus lines.

Excellent, affordable public transit is perhaps the best legacy of the communist era (locals ride all month for 300 Kč).

Tickets: The Metro, trams, and buses all use the same tickets:

• 30-minute short-trip ticket (krátkodobá), which allows as many transfers as you can make in a half hour—24 Kč

• 90-minute standard ticket (základní)—32 Kč

• 24-hour pass (jízdenka na 24 hodin)—110 Kč

• 3-day pass (jízdenka na 3 dny)—310 Kč

Buy tickets from your hotel, at Metro stops, newsstand kiosks, or from machines. To avoid wasting time looking for a ticket-seller when your tram is approaching, stock up on tickets before you set out. Since Prague is a great walking town, most find that individual tickets work better than a pass.

Be sure to validate your ticket as you board the tram or bus, or as you enter the Metro station, by sticking it in the machine, which stamps a time on it—watch locals and imitate. Inspectors routinely ambush ticketless riders (including tourists) and fine them 700 Kč on the spot.

Schedules and Frequency: Trams run every 5-10 minutes in the daytime (a schedule is posted at each stop). The Metro closes at midnight, but nighttime tram routes (identified with white numbers on blue backgrounds at tram stops) run all night at 30-minute intervals. You can find more information and a complete route planner in English at www.dpp.cz.

Trams: Navigate by signs that list the end stations. At the platform, a sign lists all the stops for each tram in order. Remember that trams going one direction leave from one platform, while the other direction might leave from a different platform nearby—maybe across the street or a half-block away. When the tram arrives, open the doors by pressing the green button. Once aboard, validate your ticket in the machine.

As you go, follow along carefully so you’ll be ready when your stop comes up. Newer trams have electronic signs that show either the next stop (příští), or a list of upcoming stops. Also, listen to the recorded announcements for the name of the stop you’re currently at, followed by the name of the stop that’s coming up next. (Confused tourists, thinking they’ve heard their stop, are notorious for rushing off the tram one stop too soon.) The surest way to know whether it’s your stop is to check the platform for a sign that shows the name of the stop.

Tram #22 is practically made for sightseeing, connecting the New Town with the Castle Quarter (find the line marked on the Prague Metro map). The tram uses some of the same stops as the Metro (making it easy to get to—or travel on from—the tram route). Of the many stops this tram makes, the most convenient are two in the New Town (Národní Třída, between the bottom of Wenceslas Square and the river; and Národní Divadlo, at the National Theater), two in the Little Quarter (Malostranské Náměstí, on the Little Quarter Square; and Malostranská Metro stop, near the riverbank), and three above Prague Castle (Královský Letohrádek, Pražský Hrad, and Pohořelec; for details, see here).

Metro: The three-line Metro system is handy and simple, but doesn’t always get you right to the tourist sights (landmarks such as the Old Town Square and Prague Castle are several blocks from the nearest Metro stops). Although it seems that all Metro doors lead to the neighborhood of Výstup, that’s simply the Czech word for “exit.”

I find Prague to be a great taxi town and use them routinely. That said, the city has more than its share of dishonest cabbies, so here are a few tips to avoid being overcharged.

Legitimate local rates are cheap: Drop charge starts at 40 Kč; per-kilometer charge is around 30 Kč; and waiting time per minute is about 6 Kč. These rates are clearly marked on the door, so be sure the cabbie honors them. Also insist that cabbies turn on the meter, and that it’s set at the right tariff, or “sazba” (usually but not always tariff #1). Unlike in many cities, there’s no extra charge for calling a cab—the meter starts only after you get in. Tip by rounding up; locals never tip more than 5 percent.

Have a ballpark idea of what your ride will cost. Figure about 150-200 Kč for a ride between landmarks within the city center (for example, from the main train station to the Old Town Square, or from the Charles Bridge to the castle). Even the longest ride in the center should cost under 300 Kč.

To improve your odds of getting a fair metered rate, call for a cab (or ask someone at your hotel or restaurant to call for you), rather than hailing one on the street. AAA Taxi (tel. 222-333-222) and City Taxi (tel. 257-257-257) are the most likely to have English-speaking staff and honest cabbies. Avoid cabs waiting at tourist attractions and train stations, who are far more likely to be crooked—waiting to prey on unwary tourists.

And what if the cabbie surprises you at the end with an astronomical fare? If you think you’re being overcharged, challenge it. Point to the rates on the door. Get your hotel receptionist to back you up. Pull out your phone and threaten to call the police. (Because of new legislation to curb dishonest cabbies, the police will stand up for you.) Or simply pay what you think the ride should cost and walk away.

A staggering number of small companies offer walking tours of the Old Town, the castle, and more (for the latest, pick up fliers at the TI). Since guiding is a routine side-job for university students, you’ll generally get hardworking young guides at good prices. While I’d rather go with my own local guide (described later), public walking tours are cheaper (4 hours for about 450 Kč), cover themes you might not otherwise consider, connect you with other English-speaking travelers, and allow for spontaneity. The quality depends on the guide rather than the company. Your best bet is to show up at the Astronomical Clock a couple of minutes before 8:00, 10:00, or 11:00, then chat with a few of the umbrella-holding guides there. Choose the one you click with. Guides also have fliers advertising additional walks.

“Free” Tours: As is the case all over Europe, “free” walking tours are not really free; you’re expected to tip your guide (with paper bills rather than coins) when finished. While these tours are fine for the backpacker and hostel crowd (for whom they’re designed), the guides are usually expat students (generally from the US or Australia) who memorize a script and give an entertaining performance as you walk through the Old Town, with little respect for serious history. When it comes to guided tours, nothing is free (except for my  Prague City Walk audio tour; see here).

Prague City Walk audio tour; see here).

In Prague, hiring a guide is particularly smart (and a ▲▲ experience). Guides meet you wherever you like and tailor the tour to your interests. Visit their websites in advance for details on various walks, airport transfers, countryside excursions, and other services offered, and then make arrangements by email. Because prices are usually per hour (not per person), small groups can hire an inexpensive guide for several days.

Personal Prague Guide Service’s Šárka Kačabová uses her teaching background to help you understand Czech culture, and has a team of personable and knowledgeable guides (600 Kč/hour for 2-3 people, 800 Kč/hour for 4-8 people, fifth hour free, mobile 777-225-205, www.personalpragueguide.com, sarka@me.com).

PragueWalker is run by Katka Svobodová, a hardworking historian-guide who knows her stuff and manages a team of enthusiastic and friendly guides (600 Kč/hour for individuals, families, and small groups; mobile 603-181-300, www.praguewalker.com, katerina@praguewalker.com).

These generally young guides (which is good, because they learned their trade post-communism) typically charge about 2,000-2,500 Kč for a half-day tour.

Jana Hronková has a natural style—a welcome change from the more strict professionalism of some of the busier guides—and a penchant for the Jewish Quarter (mobile 732-185-180, www.experience-prague.info, janahronkova@hotmail.com). Zuzana Tlášková speaks English as well as Hebrew (mobile 774-131-335, tlaskovaz@seznam.cz). Martin Bělohradský, formerly an organic chemistry professor, is particularly enthusiastic about fine arts and architecture (mobile 723-414-565, martinb5666@gmail.com). Jana Krátká enjoys sharing Prague’s tumultuous 20th-century history with visitors (mobile 776-571-538, janapragueguide@gmail.com). Friendly Petra Vondroušová designs tours to fit your interests (mobile 602-319-420, www.compactprague.com, petra.vondrous@seznam.cz).

To combine a highlights tour with exploration outside the main circuit, contact this book’s co-author, Honza Vihan (mobile 603-418-148, honzavihan@hotmail.com). Kamil and Pavlína run a family business specializing in tours of Prague and beyond. They also provide sightseeing and transport as far as Vienna and Berlin (mobile 605-701-861, www.prague-extra.com, info@prague-extra.com). Running Tours Prague are guided by Radim Prahl, a local with an appetite for ultra-marathons; he’ll run you past monuments, through parks, and down back alleys at your own pace (1,500 Kč for two people; mobile 777-288-862, www.runningtoursprague.com).

Jewish guides meet small groups twice daily in season for three-hour tours (of varying quality) in English of the Jewish Quarter. Wittmann Tours charges an 880-Kč fee that includes entry to the Old-New Synagogue and the six other major Jewish Quarter sights (which cost 480 Kč total), so the tour actually costs only 400 Kč (May-Oct Sun-Fri at 10:30 and 14:00, Nov-Dec and mid-March-April Sun-Fri at 10:30 only, no tours Sat and Jan-mid-March, minimum 3 people). Tours meet in the little park (just beyond the café), directly in front of Hotel InterContinental at the end of Pařížská street. They also offer guided side-trip minibus tours to Terezín Memorial (tel. 603-168-427 or 603-426-564, www.wittmann-tours.com). In addition, several of the private local guides recommended earlier do good tours of the Jewish Quarter.

To get beyond the sights listed in most guidebooks, or for a deeply personal look at the usual destinations, call Tom and Marie Zahn. Tom is American, Marie is Czech, and together they organize and lead family-friendly day excursions (in Prague and throughout the country). Their tours are creative and affordable, and they teach travelers how to find off-the-beaten-track destinations on their own. Their specialty is Personal Ancestral Tours & History (P.A.T.H.)—with sufficient notice, they can help Czech descendants find their ancestral homes, perhaps even a long-lost relative. Tom and Marie can also help with other parts of your Eastern European travel by linking you with associates in other countries, especially Germany, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Ukraine (US tel. 360-450-5959, Czech tel. 257-940-113, www.pathways.cz for tours, www.pathfinders.cz for genealogy research, info@pathfinders.cz).

Reverend Jan Dus, an enthusiastic pastor who lived in the US for several years, now serves a small congregation about 100 miles east of Prague. Jan can design itineraries, and likes to help travelers connect with locals in little towns, particularly in northeastern Bohemia and Moravia. He also has an outstanding track record in providing genealogical services (toll-free US tel. 800-807-1562, www.revjan.com, rev.jan.services@gmail.com).

Andy Steves (Rick’s son) runs Weekend Student Adventures (WSA Europe), offering 3-day and 10-day budget travel packages across Europe including accommodations, skip-the-line sightseeing, and unique local experiences. Locally guided and DIY unguided options are available for student and budget travelers in 12 of Europe’s most popular cities, including Prague (guided trips from €199, see www.wsaeurope.com for details).

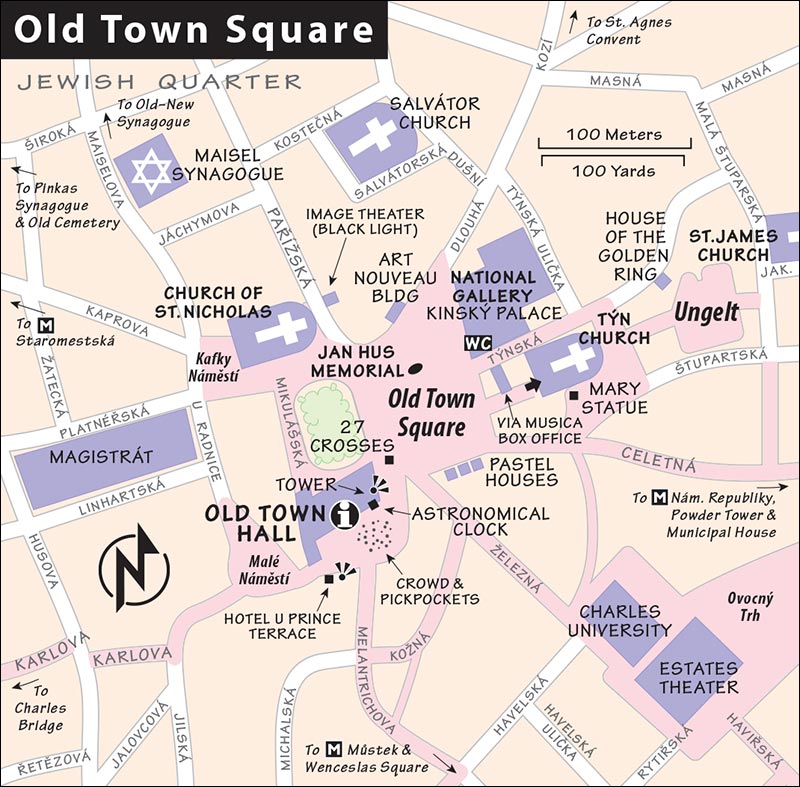

2 Old Town Square Orientation Spin-Tour

3 Old Town Hall and Astronomical Clock

4 Ungelt

5 Church of St. James (Kostel Sv. Jakuba)

7 House of the Black Madonna (Dům u Černé Matky Boží)

8 Fruit Market (Ovocný Trh) and the Estates Theater

10 Municipal House (Obecní Dům)

11 Na Příkopě, the Old City Wall

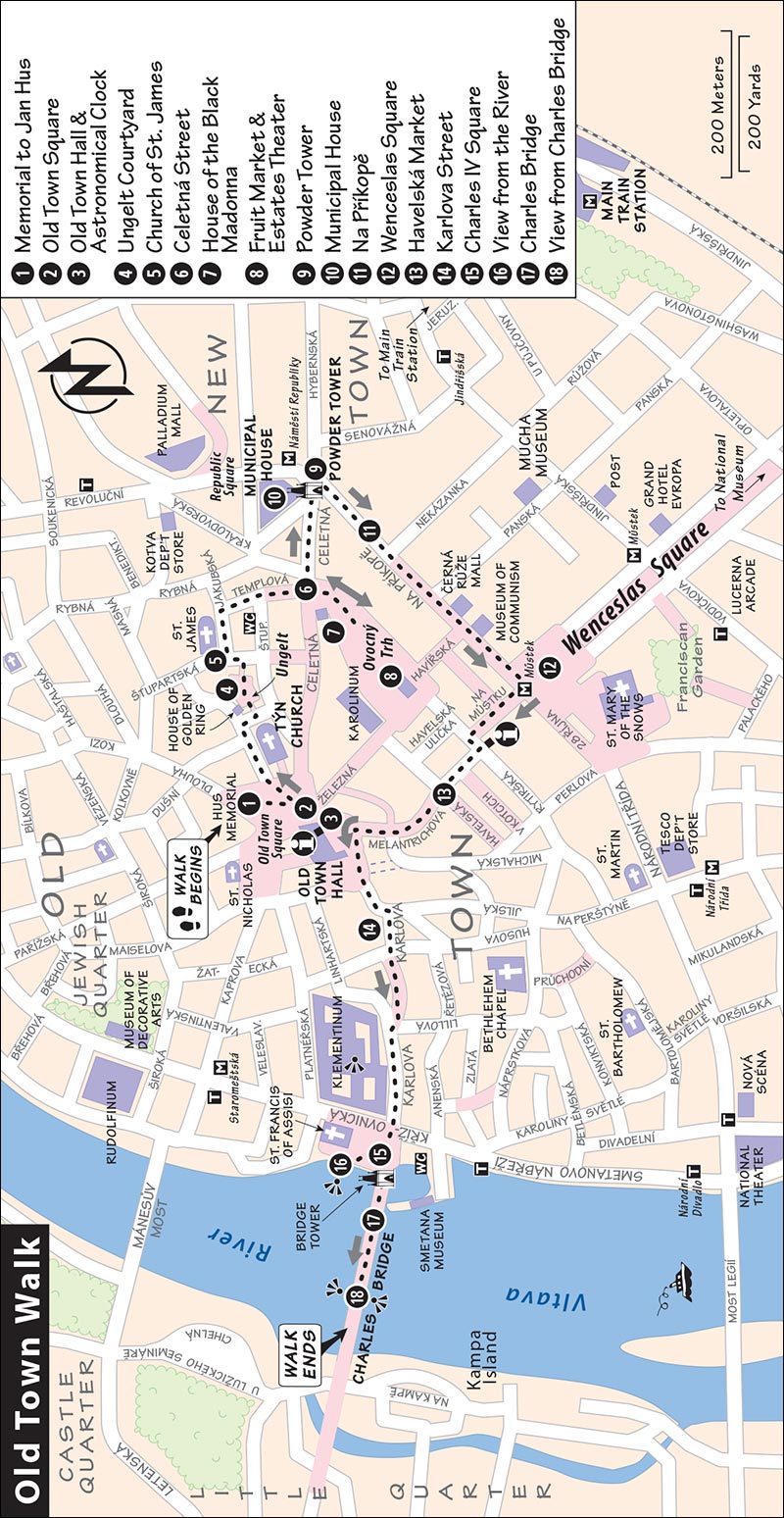

(See “Old Town Walk” map, here.)

Nestled in the bend of the river is Prague’s compact, pedestrian-friendly Old Town. A boomtown since the 10th century, the Old Town has long been the busy commercial quarter, filled with merchants, guilds, and supporters of the Church reformer Jan Hus (who wanted a Czech-style Catholicism). Today it’s Prague’s tourism ground zero, jammed with tasteful landmarks and tacky amusements alike.

This walk, which takes two to three hours, starts in the heart of the neighborhood—the Old Town Square (rated ▲▲▲)—then dips into the New Town before winding back into the Old Town and ending at the Charles Bridge.

My Prague City Walk audio tour covers sights in both the Old Town and New Town.

My Prague City Walk audio tour covers sights in both the Old Town and New Town.

• Begin with the square’s centerpiece, the...

This monument is an enduring icon of the long struggle for Czech freedom. In the center, Jan Hus—the religious reformer who has become a symbol of Czech nationalism—stands tall. Hus, born in 1369, was a Prague priest who stood up to both the Catholic Church and the Austrian Habsburg oppressors. His defiant stance—as depicted so powerfully in this monument—galvanized the Czech people, who rallied to fight not just for their religious beliefs but for independence from foreign control.

But Hus was about a century ahead of his time. He was arrested, charged with heresy, excommunicated, and, in 1415, burned at the stake. His followers picked up the torch and fought on for two decades in the Hussite Wars, which killed tens of thousands and left Bohemia a virtual wasteland.

Surrounding Hus’s statue are the Hussite followers who battled the Habsburgs. One patriot holds a cup, or chalice. This symbolizes one of the changes the Hussites were fighting for: the right of everyone (not just priests) to drink the wine at Communion. Look into the survivors’ faces—it was a bitter fight. In 1620, their rebellious cause was brutally crushed by the Catholic Habsburgs at the pivotal Battle of White Mountain fought outside Prague—effectively ending Czech independence for three centuries.

Each subsequent age has interpreted Hus to its liking: For Protestants, Hus was the founder of the first Protestant church (though he was actually an ardent Catholic); for revolutionaries, this critic of the Church’s power was a proponent of social equality; for nationalists, this Czech preacher was the defender of the language; and for communists, Hus was the first ideologue to preach the gospel of socialism. But regardless of who was in power, Hus’ importance to the Czech people has never wavered.

• Stepping away from the Hus Memorial, stand in the center of the Old Town Square, and take a 360-degree...

Whirl clockwise to get a look at Prague’s diverse architectural styles: Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo, and Art Nouveau. Remember, Prague was largely spared the devastating aerial bombardments of World War II that leveled so many European cities (like Berlin, Warsaw, and Budapest). Few places can match the Old Town Square for Old World charm.

Start with the green domes of the Baroque Church of St. Nicholas. Originally Catholic, now Hussite, this church is a popular venue for concerts. The Jewish Quarter is a few blocks behind the church, down the uniquely tree-lined “Paris Street” (Pařížská)—which also has the best lineup of Art Nouveau houses in Prague, and arguably in all of Europe.

Spin to the right. Behind the Hus Memorial is a fine yellow building that introduces us to Prague’s wonderful world of Art Nouveau: pastel colors, fanciful stonework, wrought-iron balconies, colorful murals—and what are those statues on top doing? Prague’s architecture is a wonderland of ornamental details.

Continue spinning a few doors to the right to the large, red-and-tan Rococo Kinský Palace, which displays the National Gallery’s Asian arts collection (and has a handy WC in the courtyard).

Farther to the right is the towering, Gothic Týn Church (pronounced “teen”), with its fanciful twin spires. It’s been the Old Town’s leading church in every era. In medieval times, it was Catholic. When the Hussites took power (c. 1420-1620), they made it the headquarters of their faith. After the Hussite defeat, the Habsburgs returned it to Catholicism. The symbolism tells the story: Between the church’s two towers, find a golden medallion of the Virgin Mary. Beneath that is a niche—now empty. But in Hussite times, a golden chalice stood there, symbolizing their cause. When the Catholics triumphed, they melted down the chalice and made it into this golden image of Mary.

If you want to go inside, make your way through the cluster of buildings in front of it, entering at #14 (under the arcade that faces the square; 30-Kč requested donation, generally open to sightseers Tue-Sat 10:00-13:00 & 15:00-17:00, Sun 10:30-12:00, closed Mon). The structure is full of light, with soaring Gothic arches. The ornamentation reflects the church’s troubled history: medieval Catholic; Hussite iconoclasm (stripped of decoration); and post-Hussite Habsburg (Baroque exuberance).

The row of pastel houses in front of Týn Church has a mixture of Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque facades. If you like live music, check out the convenient Via Musica box office near the church’s front door to find out all your options (see here); we’ll pass it later on this walk.

Spinning right, to the south side of the square, take in more glorious facades, each a different color with a different gable on top—step gables, triangular, bell-shaped. The tan house at #16 has a steepled bay window and a mural of St. Wenceslas on horseback, and Albert Einstein once lectured at the light-orange house at #18.

Finally, you reach the pointed 250-foot-tall spire marking the 14th-century Old Town Hall. The tower is Neo-Gothic. In the 19th century, a building was constructed on the square’s west side that once stretched from the Old Town to the Church of St. Nicholas. Then, in the last days of World War II, German tanks knocked it down...to the joy of many Prague citizens who considered it an ugly 19th-century stain on the medieval square.

Approach the Old Town Hall. At the base of the tower, near the corner of the tree-filled park, find 27 white crosses inlaid in the pavement. These mark the spot where 27 Protestant nobles, merchants, and intellectuals were beheaded in 1621 after the Battle of White Mountain—still one of the grimmest chapters in the country’s history.

• Around the left side of the tower are two big, fancy, old clock faces, being admired by many, many tourists.

The Old Town Hall, with its distinctive trapezoidal tower, was built in the 1350s, during Prague’s Golden Age. Check out the ornately carved Gothic entrance door to the left of the clock; a bit farther to the left is another door, leading to the TI, a pay WC, and the ticket desk for the clock tower elevator and Old Town Hall tours (see “Sights Inside the Old Town Hall,” later in this walk).

For now, turn your attention to that famous Astronomical Clock. See if you can figure out how it works. Of the two giant dials on the tower, the top one tells the time on two rings: The outer one, with Roman numerals, is similar to present-day clocks, while the inner one, numbered 1 through 24 in a strange but readable Bohemian script, rotates to reset each day at sunset. Within the dial is yet another revolving disc, where today’s zodiac sign is marked.

If all this seems complex to us, it must have been a marvel in the early 1400s, when the clock was installed. Remember that back then, everything revolved around the Earth (the fixed middle background—with Prague marking the center, of course). The clock was heavily damaged during World War II, and much of what you see today is a reconstruction.

The second dial, below the clock, was added in the 19th century. It shows the signs of the zodiac, scenes from the seasons of a rural peasant’s life, and a ring of saints’ names. There’s one for each day of the year, and a marker on top indicates today’s special saint. In the center is a castle, symbolizing Prague.

Four statues flank the upper clock. These politically incorrect symbols evoke a 15th-century outlook: The figure staring into a mirror stands for vanity, a Jewish moneylender holding a bag of coins is greed, and (on the right side) a Turk with a mandolin symbolizes hedonism. All these worldly goals are vain in the face of Death, whose hourglass reminds us that our time is unavoidably running out.

The clock strikes the top of the hour and puts on a little glockenspiel show daily from 9:00 to 21:00 (until 20:00 in winter). As the hour approaches, keep your eye on Death. First, Death tips his hourglass and pulls the cord, ringing the bell, while the moneylender jingles his purse. Then the windows open and the 12 apostles shuffle past, acknowledging the gang of onlookers. Finally the rooster at the very top crows and the hour is rung. The hour is often wrong because of Daylight Saving Time (completely senseless to 15th-century clockmakers). I find an alternative view just as interesting: As the cock crows, face the crowd and snap a photo of the mass of gaping tourists.

Sights Inside the Old Town Hall: Go through the door to the left of the Astronomical Clock, where the ticket desk shares a space with the TI. From here, continuing deeper into the building, you’ll find pay WCs and a bank of elevators.

Ride the elevator to floor 3 to buy your ticket to ascend the town hall’s tower (via another elevator—if it’s busy, you may have to wait a few minutes), with ▲▲ views over Prague’s prettiest square (110 Kč, Tue-Sun 9:00-21:00, Mon 11:00-21:00; after 19:00 the entry is through the door immediately to the left of the clock rather than through the TI).

On floor 1, you can take a 45-minute tour of the Old Town Hall, which includes a Gothic chapel and a close-up look at the inner guts of the Astronomical Clock, plus its statues of the 12 apostles (100 Kč, or 160-Kč combo-ticket with tower, about 3 tours/day in English—see the schedule at the ticket desk).

• Let’s leave the Old Town Square. Our next stop is directly behind the Týn Church: Cross through the square and head down the street along the left side of the church (Týnska) for about 100 yards, passing the convenient Via Musica box office. A bit farther along, on the left, you’ll pass the House of the Golden Ring, worth considering if you’re curious about 20th-century Czech art.

Continue straight through a sturdy gate, into a courtyard called...

This pleasant, cobbled, quiet courtyard of upscale restaurants and shops is one of the Old Town’s oldest places. During the Bohemian Golden Age (c. 1200-1400), it was a multicultural hub of international trade. Prague—located at the geographical center of Europe—attracted Germans selling furs, Italians selling fine art, Frenchmen selling cloth, and Arabs selling spices. They converged on this courtyard, where they could store their goods and pay their customs (which is what Ungelt means, in German). In return, the king granted them protection, housing, and a stable for their horses. By day, they’d sell their wares on the Old Town Square. At night, they’d return here to drink and exchange news from their native lands. Notice that, to protect the goods, there are only two entrances to the complex. After centuries of disuse, the Ungelt has been marvelously restored—a great place for dinner, and a reminder that Prague has been a cosmopolitan center for most of its history.

• Exit the Ungelt at the far end. Just to your left, across the street, is the...

Perhaps the most beautiful church interior in the Old Town, the Church of St. James has been the home of the Minorite Order almost as long as merchants have occupied Ungelt. A medieval city was a complex phenomenon: Commerce, prostitution, and a life of contemplation existed side by side. (I guess it’s not that much different from today.) Step inside (free, Tue-Sun 9:30-12:00 & 14:00-16:00, closed Mon); or, if it’s locked, peek through the glass door. Artistically, St. James is a stunning example of how simple medieval spaces could be rebuilt into sumptuous feasts of Baroque decoration. The original interior was destroyed by fire in 1689; what’s here now is an early 18th-century remodel. The blue light in the altar highlights one of Prague’s most venerated treasures—the bejeweled Madonna Pietatis. Above the pietà, as if held aloft by hummingbird-like angels, is a painting of the martyrdom of St. James.

• Exiting the church, do a U-turn to the left (heading up Jakubska street, along the side of the church, past some rough-looking bars). After one block, turn right on Templova street. Head two blocks down the street (passing a nice view of the Týn Church’s rear end, and some deluxe toilets) and go through the arcaded passageway, where you emerge onto...

Since the 10th century, this street has been a corridor in the busy commercial quarter—filled with merchants and guilds. These days, it’s still pretty commercial, and very touristy.

• To your right is a striking, angular building called the...

Back around the turn of the 20th century, Prague was a center of avant-garde art second only to Paris. Art Nouveau blossomed here (as we’ll soon see), as did Cubism. The Cubist exterior is a marvel of rectangular windows and cornices—stand back and see how masterfully it makes its statement while mixing with its neighbors...then get up close and study the details. The interior houses a Cubist café (the recommended Grand Café Orient, one flight up the parabolic spiral staircase)—complete with cube-shaped chairs and square-shaped rolls. The Kubista gallery on the ground floor shows more examples of this unique style.

• The long, skinny square that begins just to the left of the House of the Black Madonna is the...

This long, narrow square with a bulge in the middle is typical of medieval Central European market towns. Market stalls would pop up along the busy main drag right in the center of town—making it easy to see how a town can swell as it grows. While no fruit vendors still sell their wares here, this square has retained its traditional name.

The green-and-white building squatting in the middle of the square—right at the bulge—is the Estates Theater (Stavovské Divadlo). Built by a nobleman in the 1780s, this Classicist building was the prime opera venue in Prague at a time when an Austrian prodigy was changing the course of music. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart premiered Don Giovanni in this building (with a bronze statue of Il Commendatore duly flanking the main entrance on the left), and he directed many of his works here. Today, the Estates Theater (part of the National Theater group) continues to produce The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, and occasionally The Magic Flute.

• Backtrack a few steps to Celetná street, turn right, and head about 50 yards to the...

The big, black, 500-year-old Powder Tower was the main gate of the old town wall. It also housed the city’s gunpowder—hence the name. This is the only surviving bit of the wall that was built to defend the city in the 1400s. (Though you can go inside, it’s not worth paying to tour the interior.)

• Pass regally through the Powder Tower. In so doing, you’re leaving the Old Town. You emerge into a big, busy intersection. To your left is the Municipal House, a cream-colored building topped with a green dome. Find a good spot where you can view the facade.

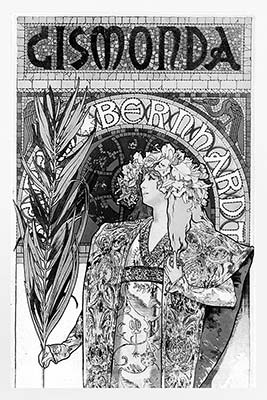

The Municipal House, which celebrated its centennial in 2011, is the “pearl of Czech Art Nouveau.” Art Nouveau flourished during the same period as the Eiffel Tower and Europe’s great Industrial Age train stations.

The same engineering prowess and technological advances that went into making those huge erector-set rigid buildings were used by artistic architects to create quite the opposite effect: curvy, organically flowing lines, inspired by vines and curvaceous women. Art Nouveau was a reaction against the sterility of modern-age construction. Look at the elaborate wrought-iron balcony—flanked by bronze Atlases hefting their lanterns—and the lovely stained glass (like in the entrance arcade).

Mosaics and sculptural knickknacks (see the faces above the windows) made the building’s facade colorful and joyous. Study the bright mosaic above the balcony, called Homage to Prague. A symbol of the city, the goddess Praha presides over a land of peace and high culture—an image that stoked cultural pride and nationalist sentiment. On the balcony is a medallion showing the three-tower castle that is the symbol of Prague.

The Municipal House was built in the early 1900s, when Czech nationalism was at a fever pitch. Having been ruled by the Austrian Habsburgs for the previous 300 years, the Czechs were demanding independence. This building was drenched in patriotic Czech themes. Within a few short years, in 1918, the nation of Czechoslovakia was formed—and the independence proclamation was announced to the people right here, from the balcony of the Municipal House.

The interior of the Municipal House has perhaps Europe’s finest Art Nouveau decor. It’s free to enter and wander the public areas. While to really appreciate the building you must attend a concert here or take one of the excellent tours offered throughout the day, any visit here gets a sweet dose of Art Nouveau (for tour details and more about the interior, see here).

• Now head west down Na Příkopě (to the left as you face the Powder Tower) toward the Metro station about 200 yards away. Enjoy the sights of...

The street called Na Příkopě was where the old city wall once stood. More specifically, the name Na Příkopě means “On the Moat,” and you’re walking along what was once the moat outside the wall. To your right is the Old Town. To the left, the New. Look at your city map and conceptualize medieval Prague’s smart design: The city was protected on two sides by its river, and on the other two sides by its walls (marked by the modern streets called Na Příkopě, Revoluční, and Národní Třída). The only river crossing back then was the fortified Charles Bridge.

• Continue up Na Příkopě—passing the Museum of Communism (described on here)—to an intersection (and nearby Metro stop) called Můstek. To your left stretches the vast expanse of the wide boulevard called...

Wenceslas Square—with the National Museum and landmark statue of St. Wenceslas at the very top—is the centerpiece of Prague’s New Town. This square was originally founded as a thriving horse market. Today it’s a modern world of high-fashion stores, glitzy shopping malls, fine old facades (and some jarringly modern ones), fast-food restaurants, and sausage stands. (For a self-guided walk through Wenceslas Square, see here.)

• Let’s plunge back into the Old Town and return to the Old Town Square. Turn about face, and head downhill (north) on the street called Na Můstku—“along the bridge” that crossed the moat (příkopě) we’ve been following until now.

Walk down Na Můstku. After one touristy block, it jogs slightly to the left and becomes Melantrichova. A block farther along, on the left, is...

This open-air market, offering crafts and produce, was first set up in the 13th century for the German trading community. Though heavy on souvenirs these days (especially on weekends), the market—worth ▲—still feeds hungry locals and vagabonds cheaply. Lined with inviting benches, it’s an ideal place to enjoy a healthy snack—and merchants are happy to sell a single vegetable or piece of fruit. The market is also a fun place to browse for crafts. It’s a homegrown, homemade kind of place; you’ll often be dealing with the actual artist or farmer. The many cafés and little eateries circling the market offer a relaxing vantage point from which to view the action.

• Continue along Melantrichova street. Eventually—after passing increasingly tacky souvenir shops and a “museum of sex machines”—Melantrichova curves right and spills out at the Old Town Square, right by the Astronomical Clock. At the clock, turn left down Karlova street. The rest of our walk follows Karlova (though the road twists and turns a bit) to the Charles Bridge, where our tour ends. Begin by heading along the top of the Small Market Square (Malé Náměstí, with lots of outdoor tables), then follow Karlova’s twisting course—Karlova street signs keep you on track, and Karlův Most signs point to the bridge. Or just follow the crowds.

Although traffic-free, Karlova street is utterly jammed with tourists as it winds toward the Charles Bridge. But the route has plenty of historic charm if you’re able to ignore the contemporary tourism. As you walk, look up. Notice historic symbols and signs of shops, which advertised who lived there or what they sold. Cornerstones, designed to protect buildings from careening carriages, also date from centuries past. The touristy feeding-frenzy of today’s Prague is at its ugliest along this commercial gauntlet. Obviously, you’ll find few good values on this drag.

Keep walking toward Charles Bridge. After the street jogs right to cross Husova, many of the buildings you’ll see on your right are associated with Prague’s Charles University. Behind the souvenir stalls lie venerable classrooms and lecture halls. For example, the Klementinum (which once housed the university’s library) is the large building that borders Karlova street on the right. Just past the intersection with Liliová, where the street opens into a little square, turn right through the archway (at #1) and into a tranquil courtyard that feels an eternity away from the touristy hubbub of Karlova. Locals enjoy using this courtyard as the key link of a less-crowded shortcut between Charles Bridge and the Old Town Square. You can also visit the Klementinum’s impressive Baroque interior on a guided tour.

• Karlova street leads directly to a tall medieval tower that marks the start of Charles Bridge. But before entering the bridge, stop on this side of the river. To the right of the tower is a little park with a great view of both the bridge and the rest of Prague across the river. While it’s officially called Křižovnické Náměstí, I think of it as...

Start with the statue of the bridge’s namesake, Charles IV (1316-1378). Look familiar? He’s the guy on the 100-koruna bill. Charles was the Holy Roman Emperor who ruled his vast empire from Prague in the 14th century—a high-water mark in the city’s history. The statue shows one of Charles’ many accomplishments: He holds a contract establishing Charles University, the first in central Europe. The women around the pedestal symbolize the school’s four traditional subjects: theology, the arts, law, and medicine.

Charles was the preeminent figure in Europe in the Late Middle Ages, and the father of the Prague we enjoy today. His domain encompassed the modern Czech Republic, and parts of Germany, Austria, and the Low Countries.

Charles was cosmopolitan. Born in Prague, raised in Paris, crowned in Rome, and inspired by the luxury-loving pope in Avignon, Charles returned home bringing Europe’s culture with him. Besides founding Charles University, he built Charles Bridge, Charles Square (where you’re standing), much of Prague Castle and St. Vitus Cathedral, and the New Town (modeled on Paris). His Golden Bull of 1356 served as Europe’s constitution for centuries (and gave anti-Semite Charles first right to the property of Jews). Power-hungry, he expanded his empire through networking and shrewd marriages, not war. Charles traded ideas with the Italian poet Petrarch and imported artists from France, Italy, and Flanders (inspiring the art of the Museum of Medieval Art—see here). Under Charles, Prague became the most cultured city in Europe. Seemingly the only thing Charles did not succeed in was renaming Prague: He wanted it to be called “New Jerusalem.”

Now look up at the bridge tower. Built by Charles, it’s one of the finest Gothic gates anywhere. The statuary shows the 14th-century hierarchy of society: people at street level, above them kings, and bishops above the kings. Speaking of hierarchy, check out Charles’ statue from near the street. From this angle, some think the emperor looks like he’s peeing on the tourists. Which reminds me, public toilets are nearby.

• Stroll to the riverside, belly up to the bannister, and take in the...

Before you are the Vltava River and Charles Bridge. Across the river, atop the hill, is Prague Castle topped by the prickly spires of St. Vitus Cathedral. Prague Castle has been the seat of power in this region for over a thousand years, since the time of Wenceslas. By some measures, it’s the biggest castle on earth.

The Vltava River is better known by its German name, Moldau. It bubbles up from the Šumava Hills in southern Bohemia and runs 270 miles through a diverse landscape, like a thread connecting the Czech people. As we’ve learned, the Czechs have struggled heroically to carve out their identity while surrounded by mightier neighbors—Austrians, Germans, and Russians. The Vltava is their shared artery. The name “Prague” comes from the word “threshold,” because the city was born at a convenient place to cross the wide river and enter a new place.

The view of Charles Bridge from here is photogenic to the max. The historic stone bridge, commissioned in 1342, connects the Old Town with the district called the Little Quarter at the base of the castle across the river. The bridge is almost seven football fields long, lined with lanterns and 30 statues, and bookmarked at each end with medieval towers.

You can climb either of the bridge towers. The tower on the Old Town side of the river (Staroměstská Mostecká Věž) is the one looming above you. Climbing its 138 steps rewards you with some of Prague’s best views: a stunning vista of the bridge itself, jammed with people heading for the castle; and 180 degrees away, a perfect panorama that reminds you why Prague is called the “Golden City of a Hundred Spires.” Across the bridge on the Little Quarter side (Malostranská Mostecká Věž), you can huff up 146 steps for fine views of the bridge, the Little Quarter rooftops, and the castle. If you’re trying to decide which to climb, consider that for snapping photos, the light is better if you climb the Old Town tower early in the day, and the Little Quarter tower late in the day (90 Kč to climb each tower, daily 10:00-22:00, March and Oct until 20:00, Nov-Feb until 18:00).

• Now wander onto the bridge. Make your way slowly across the bridge, checking out several of the statues, all on the right-hand side.

Among Prague’s defining landmarks, this much-loved bridge offers one of the most pleasant and entertaining strolls in Europe and is worth ▲▲▲. Musicians, artisans, and a constant parade of people make it a festival every day. You can come back and back to this bridge enjoying its charms differently at various times of day. Early and late, it can be enchantingly lonely. It’s a photographer’s delight during that “magic hour,” when the sun is low in the sky. The impressively expressive statues on either side of the bridge depict saints. Partway along the bridge, on your right, find a small brass relief showing a cross with five stars embedded in the wall of the bridge (it’s just below the little grate that sits on top of the stone bannister). The relief depicts a figure floating in the river, with a semicircle of stars above him. This marks the traditional spot where St. John of Nepomuk, the national saint of the Czech people, is believed to have been tossed off the bridge and into the river.

For the rest of that story, continue two more statue groups to the bronze Baroque statue of St. John of Nepomuk, with the halo of five golden stars encircling his head. This statue always draws a crowd. John was a 14th-century priest to whom the queen confessed all her sins. According to a 17th-century legend, the king wanted to know his wife’s secrets, but Father John dutifully refused to tell. The shiny plaque at the base of the statue shows what happened next: John was tortured and eventually killed by being thrown off the bridge. The plaque shows the heave-ho. When he hit the water, five stars appeared, signifying his purity. Notice the date on the inscription—1683. This oldest statue on the bridge was unveiled on the supposed 300th anniversary of the martyr’s death. Traditionally, people believe that touching the St. John plaque will make a wish come true. But you get only one chance in life to make this wish, so think carefully before you commit.

• A good way to end this walk is to enjoy the 18 city and river view from near the center of the bridge. From here, you can continue across the bridge to the Little Quarter (Kampa Island, on your left as you cross the bridge, is a tranquil spot to explore; for more on sights in this area, see page 94). Across the bridge and a 10-minute walk to the right is the Malostranská stop for the Metro or for the handy tram #22. You can also hike (or ride tram #22) up to the castle from here. Or retrace your steps across the bridge to enjoy more time in the Old Town.

I’ve arranged Prague’s sights by neighborhood for handy sightseeing. Remember that Prague started out as four towns—the Old Town and New Town on the east side of the river, and the Castle Quarter and Little Quarter on the west—and it’s still helpful for sightseers to think of the city that way.

My Prague Old Town Walk, earlier, covers the main sights in this area, including the Old Town Square and its many monuments—the Týn Church (see here) and the Old Town Hall/Astronomical Clock (here)—along with the Church of St. James (here) and the Charles Bridge (here). It also points out key landmarks, including the Ungelt courtyard (here), House of the Black Madonna (here), and Powder Tower (here).

Here are some additional sights in the Old Town.  My Prague City Walk audio tour covers sights in both the Old Town and New Town.

My Prague City Walk audio tour covers sights in both the Old Town and New Town.

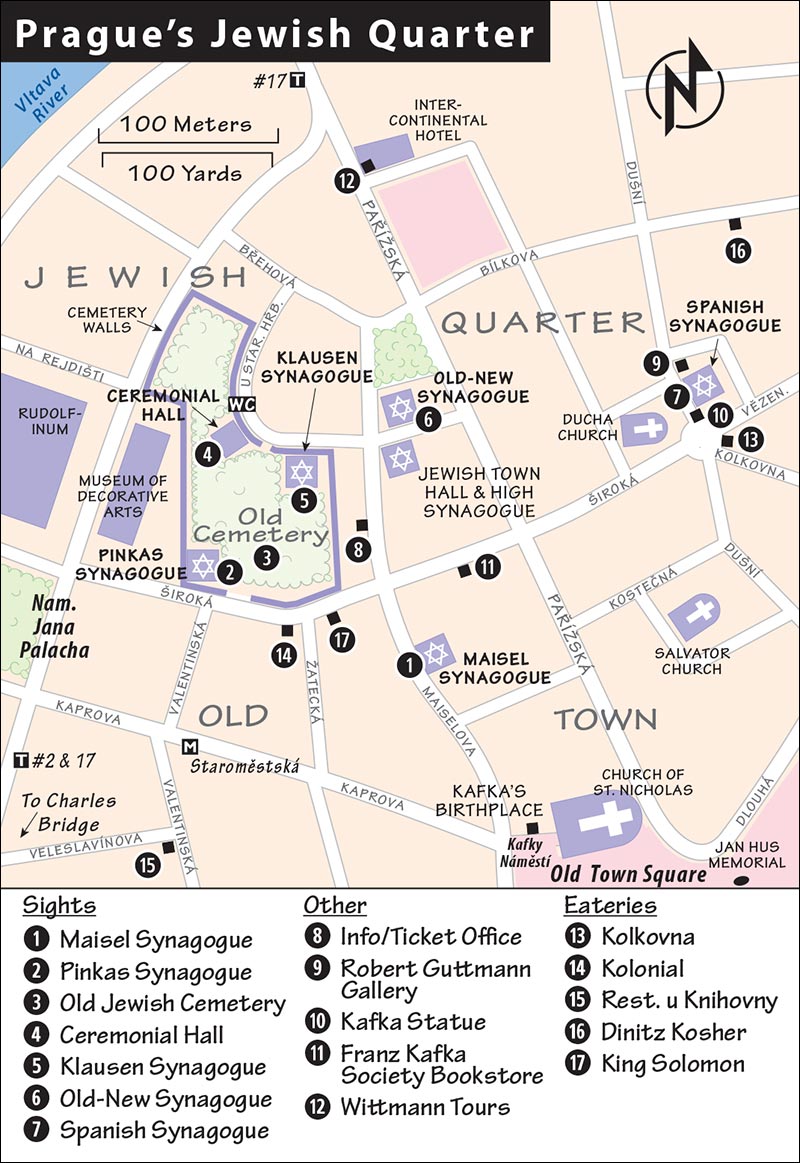

Prague’s Jewish Quarter is Europe’s most accessible sight for learning about an important culture and faith that’s interwoven with the fabric of Central and Eastern Europe. Within a three-block radius, several original synagogues, cemeteries, and other landmarks survive, today collected into one big, well-presented museum—the Jewish Museum in Prague. It can get crowded here, so time your visit carefully (early or late is best). For background on typical synagogue architecture, see the sidebar on here.

The “museum” consists of four synagogues, a ceremonial hall, and a cemetery—each described later and covered by the same ticket. To avoid lines, buy your ticket at a less-crowded sight (such as the Klausen or Spanish synagogues) instead of a more crowded one (such as the Pinkas Synagogue). You can also buy tickets at the Information Center at Maiselova 15 (near the intersection with Siroka street).

Cost and Hours: 300 Kč, covered by 480-Kč “Jewish Town of Prague” combo-ticket with Old-New Synagogue; April-Oct Sun-Fri 9:00-18:00, Nov-March until 16:30, closed year-round on Sat—the Jewish Sabbath—and on Jewish holidays; their website lists closures; 300-Kč audioguide is overkill; tel. 222-317-191, www.jewishmuseum.cz.

Getting There: The Jewish Quarter is an easy walk from Old Town Square, up delightful Pařížská street (next to the green-domed Church of St. Nicholas). The Staroměstská Metro stop is just a couple of blocks away.

Avoiding Lines: The Pinkas Synagogue can be packed, especially 9:30-12:00, so be there right as it opens or later in the day. To save time in line, buy your ticket in advance at the other less-crowded locations.

Dress Code: Men are expected to cover their heads when entering a synagogue or cemetery. While you’ll see many visitors ignoring this custom, it’s respectful to borrow a museum-issued yarmulke.

Visiting the Museum: Your ticket comes with a map that locates the sights and lists admission appointments—the times you’ll be let in if it’s very busy. (Ignore the times unless it’s extremely crowded.) You’ll notice plenty of security, which can slow down entry.

You can see the sights in any order. I recommend the order listed below, but you can rearrange it to avoid crowds.

Maisel Synagogue (Maiselova Synagóga): This newly renovated pastel-colored Neo-Gothic synagogue was built as a private place of worship for a wealthy family. It now houses an interactive exhibit on Jewish history in the Czech lands and a few precious objects. During Nazi occupation, this building became a warehouse for a vast collection of Judaica, which Hitler planned to turn into a “Museum of the Extinct Jewish Race”...perhaps explaining why these items, and the Jewish Quarter itself, managed to survive through those dark days.

Inside, the interactive exhibit retraces a thousand years of Jewish history in Bohemia and Moravia. Well-explained in English, topics include the origin of the Star of David, Jewish mysticism, the Golem legend, the history of discrimination, and the creation of Prague’s ghetto. Pre-WWII photographs of small-town synagogues from the region are projected on a large screen. Notice the eastern wall, with the holy ark containing a precious Torah mantel. Look for the banner of the Prague Jewish Butchers’ Guild, the emblem of the Cobblers’ Guild, a medieval seal ring, and the bema grillwork from Prague’s demolished Zigeuner Synagogue.

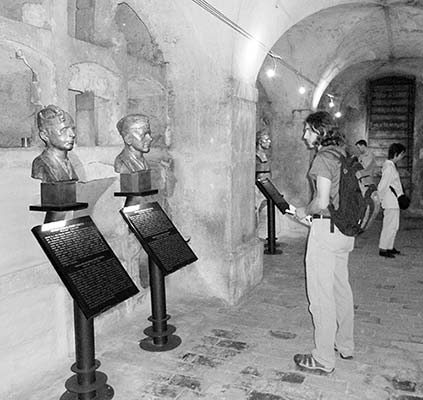

Pinkas Synagogue (Pinkasova Synagóga): For many visitors, this house of worship—today used as a memorial to the Holocaust victims—is the most powerful of the Jewish Quarter sights.

Enter and go down the steps leading to the main hall of this small Gothic synagogue. Notice the old stone-and-wrought-iron bema in the middle, the niche for the ark at the far end, the crisscross vaulting overhead, and the Art Nouveau stained glass filling the place with light.

But the main focus of this synagogue is its walls, inscribed with the handwritten names of 77,297 Czech Jews sent to the gas chambers at Auschwitz and other camps. Czech Jews were especially hard hit by the Holocaust. More than 155,000 of them passed through the nearby Terezín camp alone. Most died with no grave marker, but they are remembered here. The names are carefully organized: Family names are in red, followed in black by the individual’s first name, birthday, and date of death (if known) or date of deportation. You can tell by the dates that families often perished together. The names are gathered in groups by hometowns (listed in gold, as well as on placards at the base of the wall). As you ponder this sad sight, you’ll hear the somber reading of the names alternating with a cantor singing the Psalms.

On your way out, watch on the right for the easy-to-miss stairs up to the small Terezín Children’s Art Exhibit. Well-described in English, these drawings were made by Jewish children imprisoned at Terezín, 40 miles northwest of Prague. This is where the Nazis shipped Prague’s Jews for processing before transporting them east to death camps. Thirty-five thousand Jews died at Terezín, and many tens of thousands more died in other camps. (Terezín makes an emotionally moving day trip from Prague; see here.)

Old Jewish Cemetery (Starý Židovský Hřbitov): Hiding behind a wall and sitting above the street level, this is where Prague’s Jews buried their dead. A stroll through the crooked tombstones is a poignant experience.

Enter one of the most wistful scenes in Europe and meander along a path through 12,000 evocative tombstones. They’re old, eroded, inscribed in Hebrew, and leaning this way and that. A few of the dead have larger ark-shaped tombs. Most have a simple epitaph with the name, date, and a few of the deceased’s virtues.

From 1439 until 1787, this was the only burial ground allowed for the Jews of Prague. Over time, the graves had to be piled on top of each other—seven or eight deep—so there are actually closer to 85,000 dead here. Graves were never relocated because of the Jewish belief that, once buried, a body should not be moved. Layer by layer, the cemetery grew into a small plateau. Tune into the noise of passing cars outside, and you realize that you’re several feet above the modern street level—which is already high above the medieval level.

People place pebbles on honored tombstones. This custom, a sign of respect, shows that the dead have not been forgotten and recalls the old days, when rocks were placed upon a sandy gravesite to keep the body covered. Others leave scraps of paper that contain prayers and wishes.

Ceremonial Hall (Obřadní Síň): This rustic stone tower (1911), sitting at the edge of the cemetery, was a mortuary house used to prepare the body and perform purification rituals before burial. The inside is painted in fanciful, flowery Neo-Romanesque style. It’s filled with a worthwhile exhibition on Jewish medicine, death, and burial traditions.

Klausen Synagogue (Klauzová Synagóga): This 17th-century synagogue is devoted to Jewish religious practices. The ground-floor displays touch on Jewish holidays. Upstairs, exhibits illustrate the rituals of everyday Jewish life. It starts at birth. There are good-luck amulets to ensure a healthy baby, and a wooden cradle that announces, “This little one will become big.” The baby is circumcised (see the knife) and grows to celebrate a coming-of-age Bar or Bat Mitzvah around age 12 or 13. Marriage takes place under a canopy, and the couple sets up their home—the exhibit ends with some typical furnishings.

Note that the Spanish Synagogue—described next—is a few blocks away from the core of the Jewish Quarter. Before heading over there, consider visiting the nearby Old-New Synagogue (described at the end of this section).

Spanish Synagogue (Španělská Synagóga): Called “Spanish” though its design is Moorish (which was all the rage when this was built in the 19th century), this has the most opulently decorated interior of all the synagogues. It marked a time of relative wealth and importance for Prague’s Jews, who in this era were increasingly welcome in the greater community and (in many cases) chose to adopt a more reformed approach to worship. Exhibits explain the lives of Czech Jews in the 19th and early 20th centuries, when they believed to be living their best days yet...unaware that the Holocaust was looming.

The decor is exotic and awe-inspiring. Intricate interweaving designs (of stars and vines) cover every inch of the red-gold and green walls and ceiling. A rose window with a stylized Star of David graces the ark.

The new synagogue housed a new movement within Judaism—a Reform congregation—which worshipped in a more modern way. The bema has been moved to the front of the synagogue, so the officiant faces the congregation. There’s also a prominent organ (upper right) to accompany the singing.

Displays of Jewish history bring us through the 18th, 19th, and tumultuous 20th centuries to today. In the 1800s, Jews were increasingly accepted and successful in the greater society. But tolerance brought a dilemma—was it better to assimilate within the dominant culture or to join the growing Zionist homeland movement? To reform the religion or to remain orthodox?

Upstairs, the balcony exhibits focus on Czech Jews in the 1900s. Start in the area near the organ, which explains the modern era of Jewish Prague, including the late 19th-century development of Josefov. Then work your way around the balcony, with exhibits on Jewish writers (Franz Kafka), philosophers (Edmund Husserl), and other notables (Freud). This intellectual renaissance came to an abrupt halt with World War II and the mass deportations to Terezín (see more sad displays on life there, including more children’s art and a box full of tefillin prayer cases). The final displays bring it home: After 2,000 years of living away from their Holy Land roots, the Jewish people had a homeland—the modern nation of Israel. Finish your visit across the landing in the Winter Synagogue, showing a trove of silver—Kiddush cups, Hanukkah lamps, Sabbath candlesticks, and Torah ornaments.

The oldest surviving and most important building in the Jewish Quarter, the Old-New Synagogue goes back at least seven centuries. While the exterior is simple compared to ornate neighboring townhouses, the interior is atmospherically 13th-century.

Cost and Hours: 200 Kč, or 480-Kč combo-ticket with Jewish Museum of Prague, Sun-Thu 9:00-18:00, off-season until 17:00, Fri closes one hour before sunset, closed Sat and on Jewish holidays, admission includes worthwhile 10-minute tour, tel. 222-317-191, www.synagogue.cz.

Visiting the Synagogue: Built in 1270, this is the oldest synagogue in Eastern Europe (and some say the oldest still-working synagogue in all of Europe). The name likely comes because it was “New” when built, but became “Old” when other, newer synagogues came on the scene. The exterior is simple, with a unique saw-tooth gable. Standing like a bomb-hardened bunker, it feels as though it has survived plenty of hard times.

As you enter, you descend a few steps below street level to 13th-century street level and the medieval world.

The interior is pure Gothic—thick pillars, soaring arches, and narrow lancet windows. If it looks like a church, well, the architects were Christians. The stonework is original, and the woodwork (the paneling and benches) is also old. This was one of the first Gothic buildings in Prague.

Seven centuries later, it’s still a working synagogue. There’s the stone bema in the middle where the Torah is read aloud, and the ark at the far end, where the sacred scrolls are kept. To the right of the ark, one chair is bigger, with a Star of David above it. This chair always remains empty out of respect for great rabbis of the past. Where’s the women’s gallery? Here, women worshipped in rooms that flanked the hall, watching the service through those horizontal windows in the walls.

Before leaving, check out the lobby (the long hall where you show your ticket). It has two fortified old lockers—in which the most heavily taxed community in medieval Prague stored its money in anticipation of the taxman’s arrival.

Stray just a couple of blocks north of the Old Town Square and you’ll find a surprisingly tourist-free world of shops and cafés, pastel buildings with decorative balconies and ornamental statues, winding lanes, cobblestone streets, and mosaic sidewalks. It’s also home to this fine, underrated museum.

Prague flourished in the 14th century, and the city has amassed an impressive collection of altarpieces and paintings from that age. Today this art is housed in the former Convent of St. Agnes, which was founded in the 13th century by a Czech princess-turned-nun as the first hospital in Prague. A visit here is a sightseeing twofer: Enjoy the well-presented art in a refreshingly uncrowded setting, and savor the tranquil corridors and cloisters.

Cost and Hours: 220-Kč, 500-Kč combo-ticket also covers Sternberg Palace and Schwarzenberg Palace, plus two others; valid 7 days; convent buildings are free; open Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, closed Mon; two blocks northeast of Spanish Synagogue, along the river at Anežská 12, tel. 224-810-628, www.ngprague.cz.

Enough of pretty, medieval Prague—let’s leap into the modern era. The New Town, with Wenceslas Square as its focal point, is today’s urban Prague. This part of the city offers bustling boulevards and interesting neighborhoods. Even today, the New Town is separated from the Old Town by a “moat” (the literal meaning of the street called Na Příkopě). As you cross bustling Na Příkopě, you leave the glass and souvenir shops behind, and enter a town of malls and fancy shops that cater to locals and visitors alike. The New Town is one of the best places to view Prague’s remarkable Art Nouveau art and architecture, and to learn more about its communist past.

My Prague City Walk audio tour covers sights in both the Old Town and New Town.

My Prague City Walk audio tour covers sights in both the Old Town and New Town.

These sights are on or within a few blocks of the elongated main square of the New Town.

More a broad boulevard than a square, this city landmark is named for St. Wenceslas, whose equestrian statue overlooks the square’s top end. Wenceslas Square functions as a stage for modern Czech history: The creation of the Czechoslovak state was celebrated here in 1918; in 1968, the Soviets suppressed huge popular demonstrations (called the Prague Spring) at the square; and, in 1989, more than 300,000 Czechs and Slovaks converged here to demand their freedom (in the Velvet Revolution). Today it’s a busy thoroughfare of commerce.

Self-Guided Walk: For a taste of Prague’s 20th-century history, take a stroll beginning at the top of the square. (To get here quickly, ride the Metro to the Muzeum stop.)

Self-Guided Walk: For a taste of Prague’s 20th-century history, take a stroll beginning at the top of the square. (To get here quickly, ride the Metro to the Muzeum stop.)

• Begin at the big...

Statue of Duke Wenceslas I: The “Good King” of Christmas-carol fame was actually a wise and benevolent 10th-century duke. Václav I (as he’s called by locals) united the Czech people, back when this land was known as Bohemia. A rare example of a well-educated and literate ruler, Wenceslas Christianized and lifted the culture. He astutely allied the powerless Czechs with the Holy Roman Empire. And he began to fortify Prague’s castle as a center of Czech government. After his murder in 929, Wenceslas was canonized as a saint. He became a symbol of Czech nationalism (and appears on the 20-Kč coin). Later kings knelt before his tomb to be crowned. And he remains an icon of Czech unity whenever the nation has to rally. Like King Arthur in England, Wenceslas is more legend than history, but he symbolizes the country’s birth.

The statue is surrounded by the four other Czech patron saints. Notice the focus on books. A small nation without great military power, the Czechs have thinkers, not warriors, as national heroes.

And this statue is a popular meeting point. Locals like to say, “I’ll meet you under the horse’s tail” (though they use a cruder term).

• Circle behind the statue and stand below that tail, and turn your attention to the impressive building at the top of Wenceslas Square.

National Museum: The building is grand and the interior is rich, though the collection itself is pretty dull. The building dates from the 19th century, back when there was no unified Czech nation—just Czech-speaking peasants and two-bit, wannabe-German aristocrats living under the auspices of Austria’s Habsburg Empire. But throughout Europe, the mid-19th century was a time of national resurgence. Bold structures like this Neo-Renaissance building were a way to show the world that the Czech people had a distinct culture, a heritage of precious artifacts, and that they deserved their own nation.

Look closely at the columns on the building’s facade. Those light-colored patches are covering holes where Soviet bullets hit during the 1968 crackdown. The repair masons did an intentionally sloppy job, so that dark moment could never be plastered over and forgotten.

• To the left of the National Museum (as you face it), along the busy street, is a...

Communist-Era Building: This ugly, modern structure once housed the rubber-stamp Czechoslovak Parliament back when it voted in lock-step with Moscow. Between 1994 and 2008, this building was home to Radio Free Europe. After communism fell, RFE lost some of its funding and could no longer afford its Munich headquarters. In gratitude for its broadcasts—which had kept the people of Eastern Europe in touch with real news—the Czech government offered this building to RFE for 1 Kč a year. But as RFE energetically beamed its American message deep into the Muslim world from here, it drew attention—and threats—from Al-Qaeda. In 2009, RFE moved to a new fortress-like headquarters at an easier-to-defend locale farther from the center. Now this is an annex of the National Museum.

• Start walking down Wenceslas Square. Pause about 30 yards along, at the little patch of bushes. In the ground on the downhill side of those bushes is a...

Memorial to the Victims of 1969: After the Russian crackdown of 1968, a group of patriots wanted to stand up to the powerful Soviet occupation. One was a young philosophy student named Jan Palach. He decided that the best way to stoke the flame of independence was to set himself on fire. On January 16, 1969, Palach stood on the steps of the National Museum and ignited his body for the cause of Czech freedom. He died a few days later in a hospital ward. A month later, another student did the same thing, followed by another. Czechs are keen on anniversaries, and—20 years after Palach’s brave and patriotic act, in 1989—Czechs gathered here for a huge demonstration. A sense of new possibility swept through the city, and 10 months later, the communists were history.

• Continue down Wenceslas Square until you reach the median in front of Grand Hotel Evropa. It’s the ornate, yellow building about 300 yards down Wenceslas Square, on the right.

Architecture Along Wenceslas Square: As you walk, notice the architecture. Unlike the historic Old Town, nearly everything here is from the past two centuries. Wenceslas Square is a showcase of Prague’s many architectural styles: You’ll see Neo-Gothic, Neo-Renaissance, and Neo-Baroque from the 19th century. There’s curvaceous Art Nouveau from around 1900. And there’s the modernist response to Art Nouveau—Functionalism from the mid-20th century, where the watchword was “form follows function” and beauty took a back seat to practicality. You’ll see what’s nicknamed “Stalin Gothic” from the 1950s communist era; a good example of that is the Hotel Jalta building, halfway downhill on the right (the sandy facade with lots of balconies). And there are forgettable glass-and-steel buildings of the 1970s.

The Velvet Revolution: Opposite Grand Hotel Evropa (that is, on the left side of the square), find the Marks & Spencer building, which has a balcony on it (partly obscured by tree branches).

Picture the scene on this square on a cold November night in 1989. Czechoslovakia had been oppressed for the previous 40 years by communist Russia. But now the Soviet empire was beginning to crumble, jubilant Germans were dancing on top of the shattered Berlin Wall, and the Czechs were getting a whiff of freedom.