Part 1: Jewish Heritage on Ulica Szeroka

▲▲Old Jewish Cemetery (Stary Cmentarz)

Old Synagogue (Stara Synagoga)

Part 2: Contemporary Kazimierz

Isaac Synagogue (Synagoga Izaaka)

Meiselsa and Bożego Ciała Streets

Ulica Św. Wawrzyńca: Industrial Kazimierz

Galicia Jewish Museum (Galicja Muzeum)

MORE JEWISH SIGHTS IN KAZIMIERZ

▲New Jewish Cemetery (Nowy Cmentarz)

Ghetto Heroes’ Square (Plac Bohaterow Getta)

▲Pharmacy Under the Eagle (Apteka pod Orłem)

▲▲▲Schindler’s Factory Museum (Fabryka Emalia Oskara Schindlera)

▲Museum of Contemporary Art in Kraków (Muzeum Sztuki Współczesnej w Krakowie)

The neighborhood of Kazimierz (kah-ZHEE-mehzh), 20 minutes by foot southeast of Kraków’s Old Town, is the historic heart of Kraków’s once-thriving Jewish community. After years of neglect, the district began a rejuvenation in the early 2000s. Today, while not quite as slick and polished as Prague’s Jewish Quarter, Kazimierz’s assortment of synagogues, cemeteries, and museums helps visitors appreciate the neighborhood’s rich Jewish history. At the same time, Kazimierz also happens to be the city’s edgy, hipster culture center—jammed with colorful bars, creative eateries, and designer boutiques. This unlikely combination—where somber synagogues coexist with funky food trucks—makes Kazimierz a big draw for travelers both young and old.

When To Go: Try to visit any day except Saturday, when most Jewish-themed sights are closed (except the Old Synagogue, High Synagogue, and Galicia Jewish Museum). Monday comes with a few closures: the Ethnographic Museum, Museum of Contemporary Art in Kraków, and Museum of Municipal Engineering. On Monday, the Schindler’s Factory Museum is free, but it’s open shorter hours and is more crowded than usual. For more suggestions of what to do in Kazimierz, see the Shopping, Entertainment, Sleeping, and Eating sections.

Etiquette: To show respect, men cover their heads while visiting a Jewish cemetery or synagogue. Most sights offer loaner yarmulkes, or you can wear your own hat.

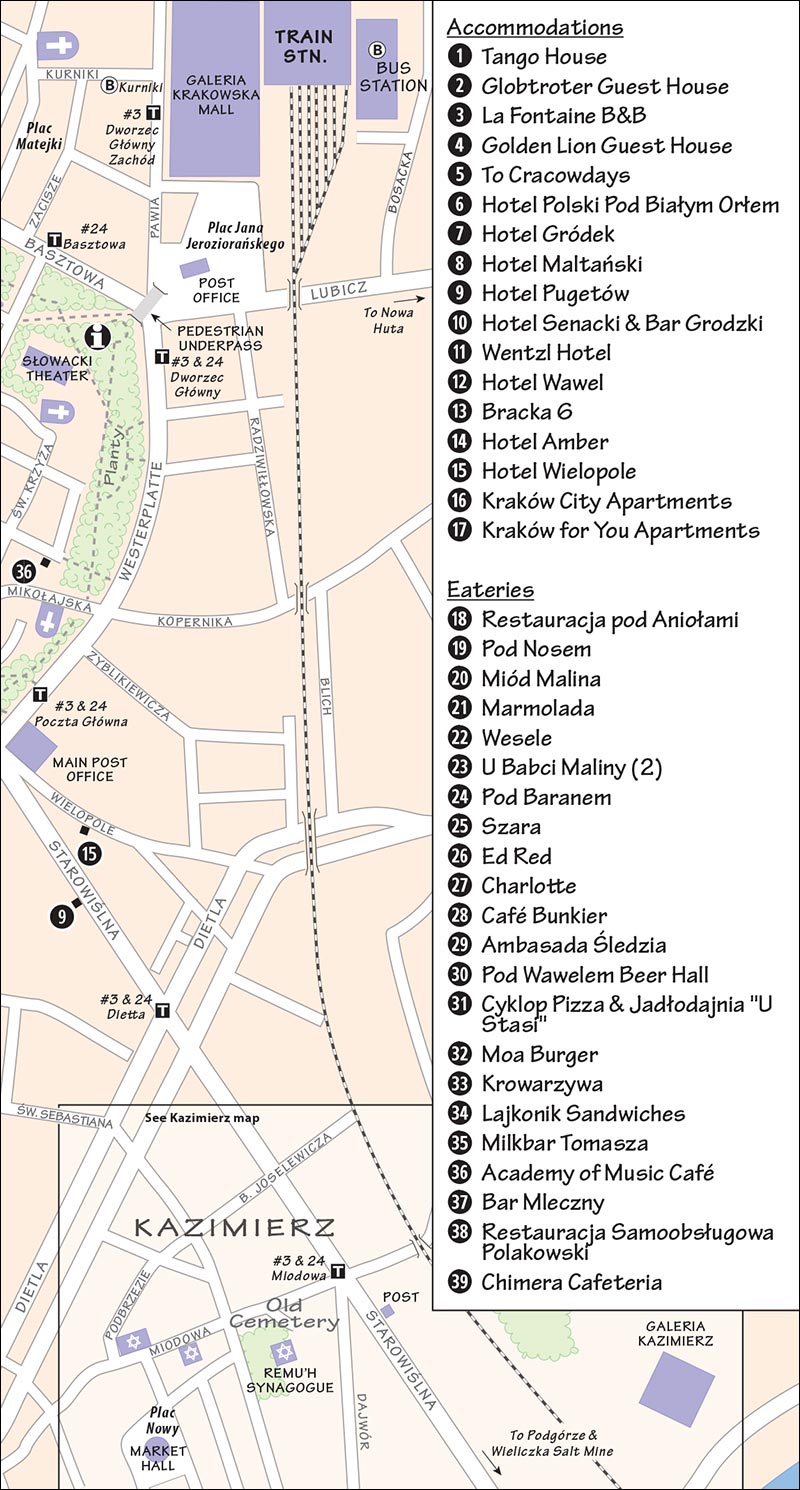

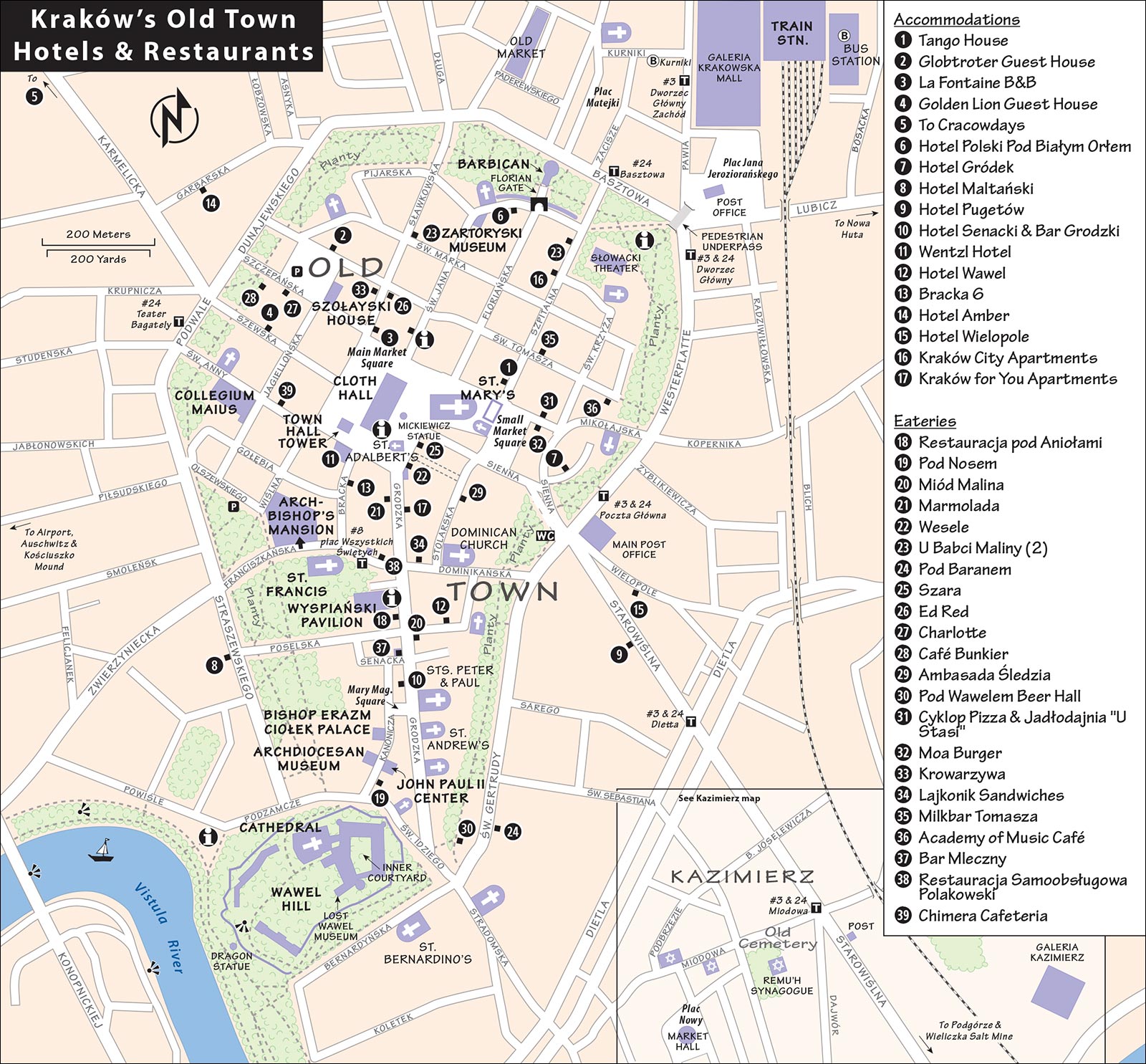

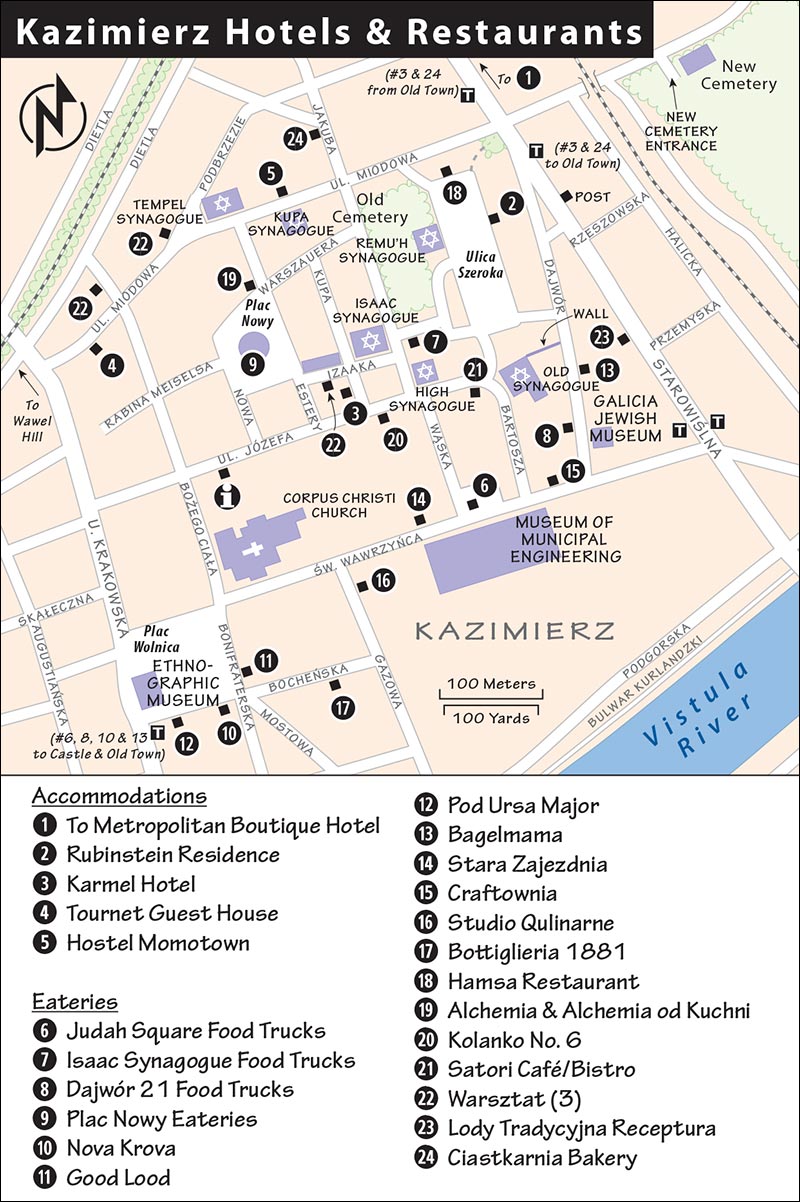

Getting to Kazimierz: From the Old Town, it’s about a 20-minute walk. From the Main Market Square, head down ulica Sienna (near St. Mary’s Church) and through the Planty park. When you hit the busy ring road, bear right and continue down Starowiślna for 15 more minutes. The tram shaves off a few minutes: Find the stop along the ring road, on the left-hand side of ulica Sienna (across the street from the Poczta Główna, or main post office). Catch tram #3 or #24, and ride two stops to Miodowa. Walking or by tram, at the intersection of Starowiślna and Miodowa, you’ll see a small park across the street and to the right. To reach the heart of Kazimierz—ulica Szeroka—cut through this park. The same trams continue to the sights in Podgórze (including the Schindler’s Factory Museum).

To return to the Old Town, catch tram #3 or #24 from the intersection of Starowiślna and Miodowa (kitty-corner from where you got off the tram).

Information: An official TI is just a few blocks off the bottom of ulica Szeroka, at ulica Józefa 7 (daily 9:00-17:00, tel. 12-422-0471).

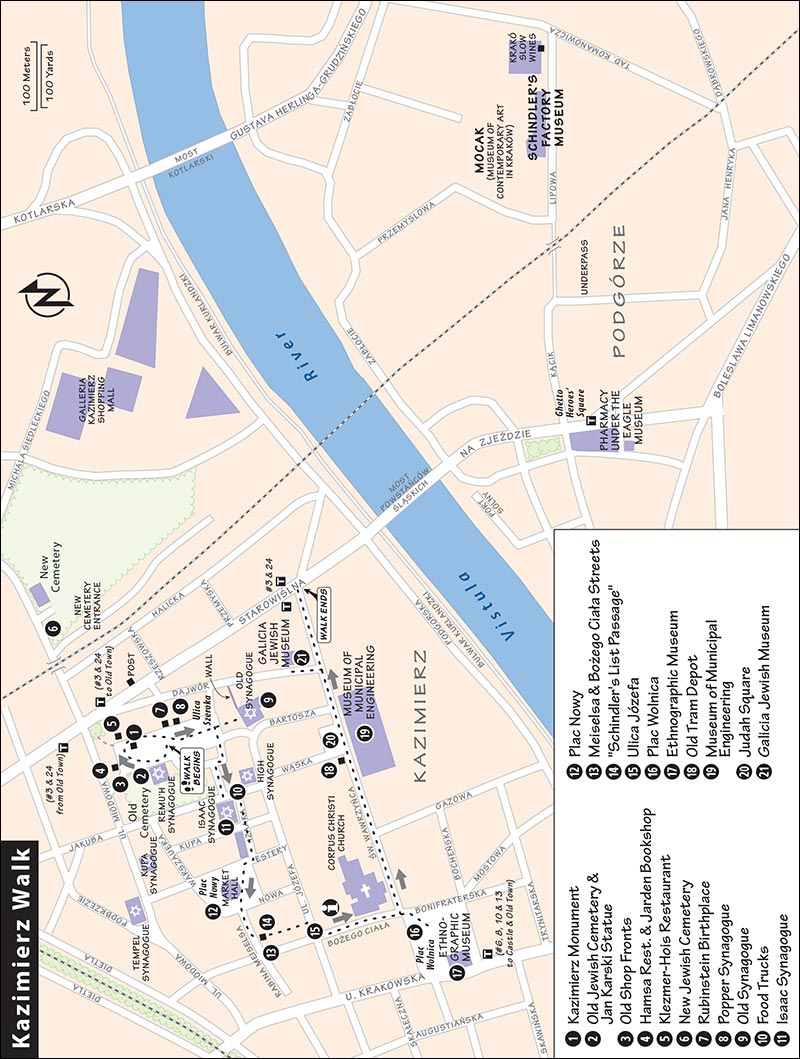

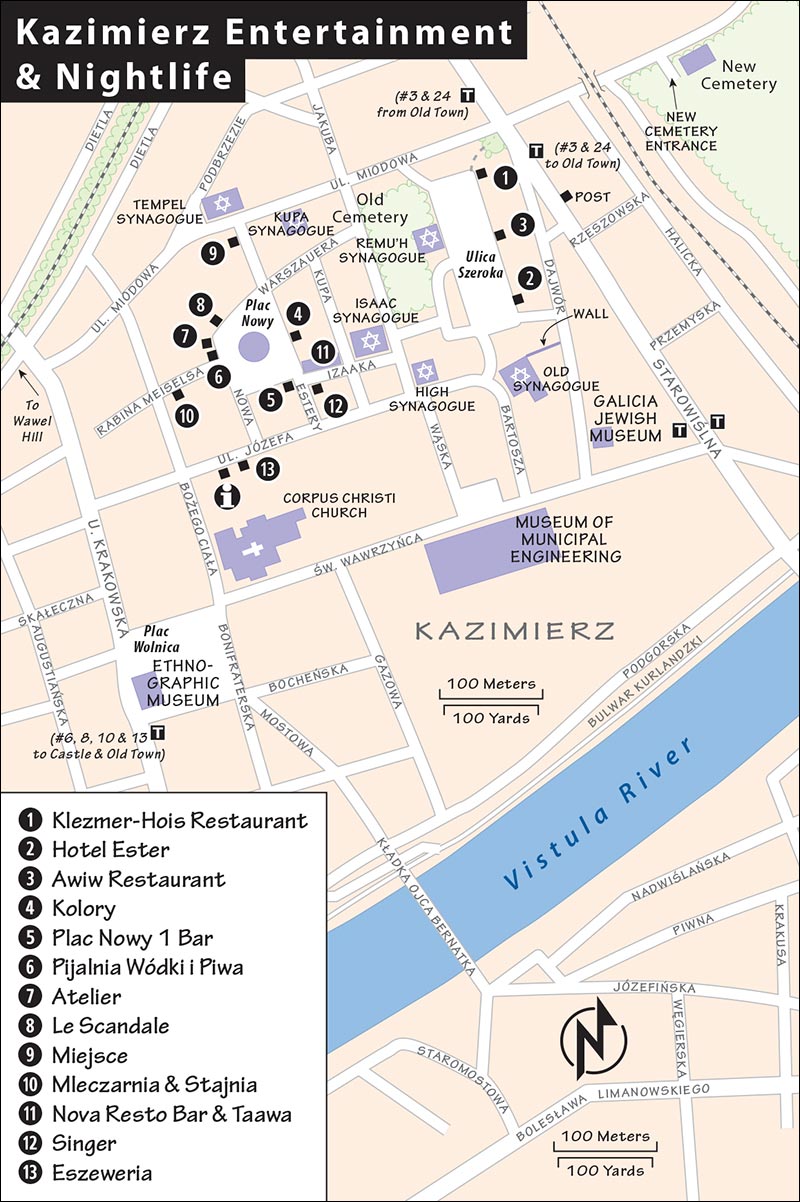

(See “Kazimierz Walk” map, here.)

This self-guided walk is designed to help you get your bearings in Kazimierz, connecting both its Jewish sights (mostly in “Part 1”) and its eclectic other attractions, from trendy bars to underrated museums (“Part 2”). Allow about an hour for the entire walk, not counting museum visits along the way. From the end of the walk, you can easily cross the river to this area’s biggest sight, the Schindler’s Factory Museum.

• We’ll start on ulica Szeroka (“Broad Street”)—the center of the neighborhood, which feels like more of an elongated square than a “street.” Begin at the bottom (southern) edge of the small, grassy park, near the strip of restaurants. In the park, look for the low-profile, stone...

You’re standing in the historical heart of Kraków’s Jewish community. In the 14th century, King Kazimierz the Great enacted policies that encouraged Jews fleeing other kingdoms to settle in Poland—including in Kraków. He also founded this town, which still bears his name. Originally, Jews lived in the Old Town, but they were scapegoated after a 1495 fire and forced to relocate to Kazimierz. Back then, Kazimierz was still a separate town, divided by a wall into Christian (west) and Jewish (east) neighborhoods. Ulica Szeroka was the main square of the Jewish community. Over time, Jews were more or less accepted into the greater community, and Jewish culture flourished here.

All that would change in the mid-20th century. The monument honors the “65 thousand Polish citizens of Jewish nationality from Kraków and its environs”—more than a quarter of the city’s pre-WWII population—who were murdered by the Nazis during the Holocaust. When the Nazis arrived, they immediately sent most of Kraków’s Jews to the ghetto in the eastern Polish city of Lublin. Soon after, they forced Kraków’s remaining 15,000 Jews into a walled ghetto at Podgórze, across the river. The Jews’ cemeteries were defiled, and their buildings were ransacked and destroyed. In 1942, the Nazis began transporting Kraków’s Jews to death camps (including Płaszów, just on Kraków’s outskirts, and Auschwitz).

Only a few thousand Kraków Jews survived the war. During the communist era, this waning population was ignored or mistreated. After 1989, interest in Kazimierz’s unique Jewish history was faintly rekindled. But it was only when Steven Spielberg chose to film Schindler’s List here in 1993 that the world took renewed interest in Kazimierz. (A local once winked to me, “They ought to build a statue to Spielberg on that square.”) Although the current Jewish population in Kraków numbers only 200, Kazimierz has become an internationally known destination for those with an interest in Jewish heritage.

• Facing the park, look to the left. The arch with the Hebrew characters marks the entrance to the...

This small cemetery was used to bury members of the Jewish community from 1552 to 1800. With more than a hundred of the top Jewish intellectuals of that age buried here, this is considered one of the most important Jewish cemeteries in Europe.

Cost and Hours: 10 zł includes cemetery and attached Remu’h Synagogue; sporadic hours according to demand—especially outside peak season—but generally open Sun-Fri 9:00-16:00, can be open until 18:00 May-Sept, closes earlier off-season and by sundown on Fri, closed Sat year-round, ulica Szeroka 40.

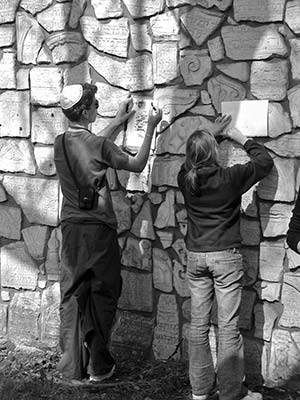

Visiting the Cemetery: Walk under the arch, pay the admission fee, step into the cemetery, and survey the tidy rows of headstones. This early Jewish resting place (later replaced by the New Cemetery, described later) was desecrated by the Nazis during the Holocaust. In the 1950s, it was discovered, excavated, and put back together as you see here. Shattered gravestones form a mosaic wall around the perimeter. As in all Jewish cemeteries, you’ll see many small stones stacked on the graves. The tradition comes from placing stones—representing prayers—over desert graves to cover the body and prevent animals from disturbing it. Behind the little synagogue to the left, the tallest tombstone next to the tree belonged to Moses Isserles (a.k.a. Remu’h), an important 16th-century rabbi. He is believed to have been a miracle worker, and his grave was one of the only ones that remained standing after World War II. Notice the written prayers crammed into the cracks and crevices of the tombstone.

Near the gate to the cemetery, step into the tiny Remu’h Synagogue (c. 1553, covered by cemetery ticket). Tight and cozy, this has been carefully renovated and is fully active. Notice the original 16th-century frescoed walls and ceilings, and the donation box at the door. For more on typical synagogue architecture, see the sidebar.

• Back outside, turn left and continue up to the top of...

Just above the cemetery gate, notice a bronze statue of a gentleman seated on a bench. This is a tribute to Jan Karski (1914-2000), a Catholic Pole and resistance fighter who published his eyewitness account The Story of a Secret State about the Holocaust in 1944. Karski—the ultimate whistleblower—was one of the first people who spoke out about Nazi atrocities, at a time when even many world leaders had only an inkling about what was happening in Hitler’s realm. Karski’s message, so shocking as to be literally unbelievable to many, went ignored by some key leaders—arguably extending the horrors of the Holocaust.

Just above that, at the top corner of the square, notice the side street with a row of rustic old Jewish shop fronts, which evoke the bustle of prewar Kazimierz. The Jewish names—Rattner, Weinberg, Nowak, Holcer—stand testament to the lively soul of this neighborhood in its heyday. This lane leads to Miodowa street, which you can follow left to reach two of Kazimierz’s lesser-known synagogues (Tempel and Kupa, both described later).

The building at the top of the square houses the recommended Hamsa restaurant (with modern Israeli food) and Jarden Bookshop, which serves as an unofficial information point for the neighborhood and sells a wide variety of fairly priced books on Kazimierz and Jewish culture in the region (Mon-Fri 9:00-18:00, Sat-Sun 10:00-18:00, ulica Szeroka 2).

Kitty-corner from the bookshop, notice Klezmer-Hois—one of many restaurants offering live traditional Jewish klezmer music nightly in summer (for more on klezmer music, and details on your options, see here).

The New Jewish Cemetery—less touristed and a striking contrast to the Old Jewish Cemetery we just saw—is a worthwhile detour, about a five-minute walk away (see description on here). To get there, cut through the grassy little lot between Jarden Bookshop and Klezmer-Hois, turn right, cross the busy street, then go through the railway underpass.

When you’re ready to move on, do a 180 and head back downhill on ulica Szeroka. You’ll pass the little park again, then come to a row of lively, mostly Jewish-themed restaurants with outdoor tables. Several places along here (especially Ester Hotel, at the bottom of the row) feature outdoor klezmer music in good weather—allowing you to get a taste of this unique musical form before committing to a full meal.

Halfway down this side of the square, the green house at #14 is where Helena Rubinstein was born in 1870. At age 31, she emigrated to Australia, where she parlayed her grandmother’s traditional formula for hand cream into a cosmetics empire. Many cosmetics still used by people worldwide today were invented by Rubinstein, who died at age 92 in New York City as one of the most successful businesswomen of all time—just one of many illustrious Jewish residents of Kazimierz.

Two doors past the Rubinstein house, notice the round arch marking the courtyard of the Popper Synagogue, a popular venue for klezmer concerts.

Continue past the restaurants to the very bottom of ulica Szeroka, and pause at the steps before heading down into the sunken area around the Old Synagogue. To the synagogue’s left, notice a short, reconstructed stretch of Kazimierz’s 14th-century town wall. This is a reminder that medieval Kazimierz was a separate city from Kraków. It’s easy to read some history into a map of Kazimierz (you’ll find one on the big panel in front of the Old Synagogue): Today’s Starowiślna and Dietla streets—which frame off Kazimierz in a triangle of land hemmed in by the riverbank—were once canals (Kazimierz was built on an island). When King Kazimierz the Great—who reportedly didn’t care much for Krakovians—founded this district in 1335, he envisioned it as a separate town to rival Kraków. It wasn’t until around 1800 that the two towns merged.

• Turn your attention to the bottom of the square, with the...

The oldest surviving Jewish building in Poland (15th century) sits eight steps below street level. Jewish structures weren’t allowed to be taller than Christian ones—and so, in order to have the proper proportions, the synagogue’s “ground floor” had to be underground. Today the synagogue houses a good three-room museum on local Jewish culture, with informative English descriptions and a well-preserved main prayer hall (9 zł, free on Mon; April-Oct Mon 10:00-14:00, Tue-Sun 9:00-17:00; shorter hours off-season; good 50-stop audioguide-10 zł; ulica Szeroka 24, tel. 12-422-0962).

• A few more Jewish sights can be found in the surrounding streets; I’ll point these out in “Part 2,” though the rest of this walk focuses on a more recent chapter.

• Stand with your back to the Old Synagogue and turn left, heading up the little alley next to Szeroka 28—called Lewkowa.

Follow Lewkowa between some old buildings. When you pop out into an open area, jog right, then continue straight along ulica Ciemna. Soon you’ll hit an inviting little pod of food trucks (described on here). Pause here—perhaps while nursing an açaí smoothie, an artisanal kielbasa, or a taco—and ponder the explosion of youthful culture that’s taken place in Kazimierz over the last generation.

At the end of World War II, Kazimierz was badly damaged and depopulated. And so it remained for generations, as the communist authorities brushed Jewish heritage under the rug. By the early 2000s, Kazimierz’s artistically dilapidated buildings, low rents, and easy proximity to the Old Town became enticing to creative young people. A variety of artsy entrepreneurs took root here, beginning with a cluster of ramshackle, rustic bars (inspired partly by Budapest’s “ruin pub” scene). Today the district has the city’s (and probably Poland’s) highest concentration of trendy food trucks, cafés, bars, restaurants, and design shops—several of which we’ll see as we continue.

• From the food trucks, continue straight ahead (on Izaaka street). This leads you around the left side of...

One of Kraków’s biggest synagogues, this was built in the 17th century. Inside, the walls in the prayer hall are decorated with giant paintings of prayers for worshippers who couldn’t afford to buy books (with translations posted below). The synagogue also serves as the local center for the Hasidic Jewish group Chabad, with a kosher restaurant and a library (7 zł; April-Oct Sun-Thu 8:30-20:00, Fri 8:30-14:30, closed Sat year-round, shorter hours off-season; ulica Kupa 18, tel. 12-430-2222). In addition to its Sabbath services, this is Kraków’s only synagogue that has daily prayers (at 8:30). They also host klezmer music concerts many evenings at 18:00 (60 zł).

• Just past Isaac Synagogue is the heart of Kazimierz’s nightlife zone (also bustling by day). Dive in, passing some characteristic cafés (on your left) and the chic Taawa nightclub (on your right). Then jog right at the glitzy Plac Nowy 1 beer hall to reach...

Kazimierz’s endearing “new” market square, plac Nowy (plats NOH-vee), retains much of the gritty flavor of the district before tourism and gentrification. The circular brick building in the center is a slaughterhouse where Jewish butchers would properly kill livestock, kosher-style. Today its windows are filled with little stand-up eateries ranging from burgers and ice cream to the traditional local pizza-like zapiekanki. Circle the market hall and browse for a snack (for more on the plac Nowy scene, see “Eating in Kraków,” later). Good Lood has Kraków’s best artisanal ice cream—if you don’t mind the long line. This square is also ringed by several fun and funky bars—enjoyable by day, but hopping at night (see here).

• Leave plac Nowy along Meiselsa street (to the left from where you entered, past the yellow Jewish Cultural Center). After one block, pause at the intersection of...

The Holocaust was a dark chapter that dominates Kazimierz’s history. But this intersection is a reminder that, up until the Nazis arrived, Kazimierz was a place where Jews and Christians lived side-by-side, in relative harmony. Notice the street names, which mix Jewish and Catholic namesakes: ulica Meiselsa (“Meisels Street”—honoring a deeply respected 19th-century rabbi) and ulica Bożego Ciała (“Corpus Christi Street”—named for the towering brick church you can see just ahead). As if to celebrate the ecumenism of this intersection, a street artist has painted a graffiti Gene Kelly on the wall...very “happy again” indeed that Kazimierz is blossoming and full of life.

• Backtrack a few steps up Meiselsa and duck into the courtyard on the right, under the dilapidated arch (labeled Stajnia).

This courtyard is a popular tourist spot thanks to its brush with fame, as a location for some key scenes in Schindler’s List (find the back-and-white stills from the movie partway down on the right, just before the arch). Spielberg connection aside, this is a particularly evocative setting to nurse a relaxing drink at one of the atmospheric cafés.

• Carry on all the way through the passage. You’ll pop out at...

This street has Kazimierz’s highest concentration of funky, one-off boutiques: jewelry, fashion, housewares, and more. For a rundown of the best options along here, see here. There’s also a TI just across the street.

• When you’re ready to move along, take ulica Józefa a few steps to the intersection with ulica Bożego Ciała, turn left, and follow it a long block. You’ll pass Corpus Christi Church on your left, then arrive at...

Remember that Kazimierz was originally a separate town from Kraków. This was its main market square, designed to one-up its crosstown rival—right down to the dramatic, red-brick Catholic church on the corner (Corpus Christi).

The former Kazimierz town hall at the far end of the square houses an unusually good Ethnographic Museum (Muzeum Etnograficzne)—worth ▲. If you’re interested in Polish folk culture, it’s worth a visit. On the ground floor, you’ll find models of traditional rural Polish homes, as well as musty replicas of the interiors (like an open-air folk museum moved inside). The exhibit continues upstairs, where each in a long lineup of traditional Polish folk costumes is identified by specific region. Follow the one-way route through exhibits on village lifestyles, rustic tools, and musical instruments (including a Polish bagpipe). A highlight is the explanation of traditional holiday celebrations—from elaborate crèche scenes at Christmas, to a wall of remarkably painted Easter eggs. Some items are labeled in English, but it’s mostly in Polish. The top floor features temporary exhibits (13 zł, free on Sun, open Tue-Sun 10:00-19:00, closed Mon, ulica Krakowska 46, tel. 12-430-6023, www.etnomuzeum.eu).

• There’s more to see in Kazimierz. But if you’re pooped, you could catch tram #6, #8, #10, or #13 back to Wawel Castle, then on to the plac Wszystkich Świętych stop in the heart of the Old Town (catch tram from along Krakowska street, behind the Ethnographic Museum).

To continue the walk from plac Wolnica, head up ulica Św. Wawrzyńca (at the corner where you entered the square, with the Corpus Christi Church on your left).

By the late 19th century, Kazimierz was not just a Jewish cultural hotspot, but also a center of local industry. (It’s no coincidence that Oskar Schindler had his factory near here.) After the church, on your left, look for the glass-and-steel arched roof of the Industrial Age old tram depot, which now houses a recommended brewpub. In sunny summer weather, the pebbly courtyard is filled with happy drinkers.

Across the street, notice the many tram tracks leading in to a courtyard with several more storage sheds for local trams. This gorgeously restored complex now houses the Museum of Municipal Engineering (Muzeum Inżynierii Miejskiej). Exhibits include a history of the town’s public-transit system (including several antique trams), old Polish-made cars and motorcycles (among them the tiny commie-era Polski Fiat), typography and historical printing presses, and a hands-on area for kids called “Around the Wheel” (10 zł, family ticket-29 zł, includes English audioguide, free on Tue; open Tue-Sun 10:00-16:00; Tue, Thu, and Sun until 18:00 in June-Sept; closed Mon year-round; Św. Wawrzyńca 15, tel. 12-421-1242, www.mimk.com.pl).

Continue along ulica Św. Wawrzyńca a few more steps. At the intersection with Wąska, Judah Square (Skwer Judah) is a vacant lot with a gaggle of enticing food carts watched over by a giant mural. Commissioned for Kraków’s Jewish Cultural Festival in 2013, the illustration was painted by Israeli street artist Pilpeled. It shows a young boy who feels small and scared, but lionhearted nevertheless—a poignant symbol for the Holocaust survivors of Kazimierz. If you’re ready for a meal or snack, you’ll find several good options here.

• A half-block farther down ulica Św. Wawrzyńca is another place for refreshment, the recommended Craftownia (Polish microwbrews on tap, on the left at #22). Next you’ll reach the intersection with Dajwór street. Turn left here and walk a few steps up the street; on the right, you’ll find the...

This museum, worth ▲ and housed in a restored Jewish furniture factory, focuses on the present rather than the past. The permanent “Traces of Memory” photographic exhibit shows today’s remnants of yesterday’s Judaism in the area around Kraków (a region known as “Galicia”). From abandoned synagogues to old Jewish gravestones flipped over and used as doorsteps, these giant postcards of Jewish artifacts (with good English descriptions) ensure that an important part of this region’s heritage won’t be forgotten. Good temporary exhibits complement this permanent collection (15 zł, daily 10:00-18:00, 1 block east of ulica Szeroka at ulica Dajwór 18, tel. 12-421-6842, www.galiciajewishmuseum.org). The museum also serves as a sort of cultural center, with a good bookstore and café.

• Notice yet another cluster of food trucks across the street from the museum.

Our Kazimierz orientation walk is finished. From here, you have several options. To return to ulica Szeroka, where we began, walk up Dajwór street past the museum, then angle left through the park at the reconstructed chunk of town wall—you’ll wind up at the Old Synagogue.

For the next two options, you’ll first head back down to ulica Św. Wawrzyńca, turn left, and walk one more block to the intersection with Starowiślna street. Just to the left on Starowiślna, look for the tram stops. The tram stop on the far side of the street takes you back to the Old Town (tram #3 or #24). From the tram stop on the near side of the street, tram #3 or #24 zips you to the sights in Podgórze—including Ghetto Heroes’ Square and the Schindler’s Factory Museum (both described later). You can also reach the Podgórze sights on foot by turning right on Starowiślna and crossing the bridge (about a 10-minute walk).

In addition to the sights connected by the walk above, here’s another cemetery and a few more synagogues to round out your Jewish Kazimierz experience.

This burial place—much larger than the Old Jewish Cemetery—has graves of those who died after 1800. It was vandalized by the Nazis, who sold many of its gravestones to stonecutters and used others as pavement in their concentration camps. Many have since been cemented back in their original positions, while others—which could not be replaced—have been used to create the moving mosaic wall and Holocaust monument (on the right as you enter). Most gravestones are in one of four languages: Hebrew (generally the oldest, especially if there’s no other language, though some are newer “retro” tombstones); Yiddish (sounds like a mix of German and Hebrew and uses the Hebrew alphabet); Polish (Jews who assimilated into the Polish community); and German (Jews who assimilated into the German community). The earliest graves are simple stones, while later ones imitate graves in Polish Catholic cemeteries—larger, more elaborate, and with a long stone jutting out to cover the body. Notice that some new-looking graves have old dates. These were most likely put here well after the Holocaust (or even after the communist era) by relatives of the dead.

Cost and Hours: Free, Sun-Fri 8:00-18:00, winter until 16:00, closed Sat. It’s tricky to find: Go under the railway tunnel at the east end of ulica Miodowa, and jog left as you emerge. The cemetery is to your right (enter through gate with small cmentarz żydowski sign).

In addition to the three synagogues mentioned on the Kazimierz Walk (Old Synagogue, Isaac, and Remu’h), others also welcome visitors. Each of these charges a small admission fee and is closed Saturdays (unless noted). The High Synagogue—so called because its prayer room is upstairs—displays changing exhibits, most of which focus on the people who lived here before the Holocaust (daily, ulica Józefa 38). Tempel Synagogue (Synagoga Templu) has the grandest interior—big and dark, with elaborately decorated, gilded ceilings and balconies (corner of ulica Miodowa and ulica Podbrzezie). The Jewish Community Centre next door offers activities both for members of the local Jewish community and for tourists (lectures, genealogical research, Friday-night Shabbat meals, Hebrew and Yiddish classes, and so on; www.jcckrakow.org). Nearly across the street, the smaller Kupa Synagogue (Synagoga Kupa)—clean and brightly decorated—sometimes hosts temporary exhibits (Miodowa 27).

The neighborhood called Podgórze (POD-goo-zheh), directly across the Vistula from Kazimierz, has one of Kraków’s most famous sights: Schindler’s Factory Museum. I’ve listed these sights in the order you’ll reach them as you come from Kazimierz or the Old Town.

Background: This is the neighborhood where the Nazis forced Kraków’s Jews into a ghetto in early 1941. (Schindler’s List and the films in the Pharmacy Under the Eagle museum depict the sad scene of the Jews loading their belongings onto carts and trudging over the bridge into Podgórze.) Non-Jews who had lived here were displaced to make way for the new arrivals. The ghetto was surrounded by a wall with a fringe along the top that resembled Jewish gravestones—a chilling premonition of what was to come. A short section of this wall still stands along Lwowska street. The tram continued to run through the middle of Podgórze, without stopping—giving Krakovians a chilling glimpse at the horrifying conditions inside the ghetto.

Getting There: To go directly to Ghetto Heroes’ Square, continue through Kazimierz on tram #3 or #24 (described earlier, under “Getting to Kazimierz”) to the stop called plac Bohaterow Getta. Or you can ride the tram or walk 10 minutes across the bridge from the end of my Kazimierz Walk.

This unassuming square is the focal point of the visitor’s Podgórze. Today the square is filled with a monument consisting of 68 empty metal chairs—representing the 68,000 people deported from here. This is intended to remind viewers that the Jews of Kazimierz were forced to carry all of their belongings—including furniture—to the ghetto on this side of the river. It was also here that many Jews waited to be sent to extermination camps. The small, gray building at the river end of Ghetto Heroes’ Square feels like a train car inside, evocative of the wagons that carried people from here to certain death.

This small but good museum, on Ghetto Heroes’ Square, tells the story of Tadeusz Pankiewicz, a Polish Catholic pharmacist who chose to remain in Podgórze when it became a Jewish ghetto. During this time, the pharmacy was an important meeting point for the ghetto residents, and Pankiewicz and his staff heroically aided and hid Jewish victims of the Nazis. (Pankiewicz survived the war and was later acknowledged by Israel as one of the “Righteous Among the Nations”—non-Jews who risked their lives to help the Nazis’ victims during World War II. You’ll see his medal on display in the white memorial room at the end of the museum.) Today the pharmacy hosts an exhibit about the Jewish ghetto. You’ll enter into the re-created pharmacy, where the “windows” are actually screens that show footage from the era. Push buttons, pull out drawers, answer the phone—it’s full of interactive opportunities to better understand what ghetto life was like. You’ll learn about people who worked in the pharmacy (including riveting interviews with eyewitnesses—some in English, others subtitled) and hear Pankiewicz telling stories about that tense time. You’ll also learn a bit about the pharmacy business from that period.

Cost and Hours: 10 zł; if you’re also going to the Schindler’s Factory Museum, buy the 23-zł combo-ticket, free on Mon, open Mon 10:00-14:00, Tue-Sun 9:00-17:00, closed the second Tue of each month, plac Bohaterow Getta 18, tel. 12-656-5625, www.mhk.pl/branches/eagle-pharmacy.

One of Europe’s best museums about the Nazi occupation fills some of the factory buildings where Oskar Schindler and his Jewish employees worked. While the museum tells the story of Schindler and his workers, it broadens its perspective to take in the full experience of all of Kraków during the painful era of Nazi rule—making it the top WWII museum in this country so profoundly affected by that war. It’s loaded with in-depth information (all in English), and touchscreens invite you to learn more and watch eyewitness interviews. Scattered randomly between the exhibits are replicas of everyday places from the age—a photographer’s shop, a tram car, a hairdresser’s salon—designed to give you a taste of 1940s Kraków. Throughout the museum are calendar pages outlining wartime events and giving a sense of chronology. Note that you’ll see nothing of the actual factory or equipment, as the threat of the advancing Red Army forced Schindler to move his operation lock, stock, and barrel to Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia in 1944.

Cost and Hours: 21 zł, 24-zł combo-ticket with next-door Museum of Contemporary Art, 23-zł “Memory Trail” combo-ticket with Pharmacy Under the Eagle; free on Mon; open April-Oct Mon 10:00-16:00 (except closes at 14:00 first Mon of month), Tue-Sun 9:00-20:00; Nov-March Mon 10:00-14:00, Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00; last entry 1.5 hours before closing, tel. 12-257-1017, www.mhk.pl/branches/oskar-schindlers-factory.

Crowd-Beating Tips: Crowds can be a real problem at this popular sight—especially on Mondays (when it’s free, and many other museums are closed), during the summer holidays (June-Aug), and midday (usually worst 11:00-16:00). At busy times, you may have to wait in a long line—an hour or more—just to buy a ticket. And then, once inside, congestion can make it challenging to fully appreciate the place. If you anticipate crowds, you can book tickets for no extra fee up to three days before your visit (www.bilety.mhk.pl); or you can buy tickets anytime (even for later the same day) at the Kraków City Museum Visitors Center in the Cloth Hall on the Main Market Square (see “Tourist Information,” here). But even if you avoid the ticket line, it could still be jammed inside. The best strategy is to arrive early (9:00 or soon after on most days) or late (in summer, arriving by 18:00 gives you two hours to tour the exhibits)—but be warned that if you’re arriving late, it’s possible on very busy days that all tickets could be sold out.

Getting There: It’s in a gloomy industrial area a five-minute walk from Ghetto Heroes’ Square (plac Bohaterow Getta): Go up Kącik street (use the pedestrian underpass, then head to the left of the big, glass skyscraper), go under the railroad underpass, and continue two blocks, past MOCAK (the Museum of Contemporary Art in Kraków, described later) to the second big building on the left (ulica Lipowa 4). Look for signs to Emalia.

Visiting the Museum: You’ll begin on the ground floor, where you’ll buy your ticket and have the chance to tour the special exhibits. There’s also a “film café” (interesting for fans of the movie) with refreshments. Then head upstairs to the first floor.

First Floor: The 35-minute film, called Lipowa 4 (this building’s address), sets the stage with interviews of both Jews and non-Jews describing their wartime experience (find it just off of the museum’s first, circular room; subtitled in English, it runs continuously). From here, the one-way route winds through the permanent exhibit, called “Kraków Under Nazi Occupation 1939-1945.” First, while idyllic music plays, “stereoscopic” (primitive 3-D) photos of prewar Kraków capture an idyllic age when culture flourished and the city’s Jews (more than one-quarter of the population) blended more or less smoothly with their Catholic-Pole neighbors. But then, a video explains the Nazi invasion of Poland in early September of 1939: It took them only a few weeks to overrun the country (which desperately awaited the promised-for help of their British and French allies, who never arrived). Through the next several rooms, watch the film clip of SS soldiers marching through the Main Market Square—renamed “Adolf-Hitler-Platz”—and read stories about how the Nazis’ Generalgouvernement attempted to reshape the life of its new capital, “Krakau.” (Near the tram car, look for the decapitated head of the Grunwald monument—described on here—which had been a powerful symbol of a Polish military victory over German forces.) You’ll see the story of a newly German-owned shop selling Nazi propaganda and learn how professors at Kraków’s Jagiellonian University were arrested to prevent them from fomenting rebellion among their students. During this time, even Polish secondary schools were closed—effectively prohibiting learning among Poles, whom the Nazis considered inferior. But Polish students continued to meet clandestinely with their teachers. You’ll also see images of Hans Frank—the hated puppet ruler of Poland—moving into the country’s most important symbol of sovereignty, Wawel Castle. The exhibit also details how early Nazi policies targeted Jews with roundups, torture, and execution. (Down the staircase is an eerie simulation of a cellar prison.) As the Nazis ratcheted up their genocidal activities, troops swept through Kraków on March 3, 1941, forcing all the remaining Jews in town to squeeze into the newly created Podgórze ghetto. At the bottom of the stairs, look for the huge pile of plunder—Jewish wealth stolen by the Nazis.

Second Floor: Climb upstairs using the long staircase, which was immortalized in a powerful scene in Schindler’s List. At the top of the stairs on the right is a small room that served as “Schindler’s office” for the film; more recently, it’s been determined that his actual office was elsewhere (we’ll see it soon).

You’ll walk through a corridor lined by a replica of the wall that enclosed the Podgórze ghetto and see poignant exhibits about the horrific conditions there (including a replica of the cramped living quarters). The Nazis claimed that Jews had to be segregated here, away from the general population, because they “carried diseases.”

Continue into the office of Schindler’s secretary, with exhibits about Schindler’s life and video touchscreens that play testimonial footage of Schindler’s grateful employees. Then proceed into the actual Schindler’s office. The big map (with German names for cities) was uncovered only in recent years when the factory was being restored. Because Schindler’s short tenure here was the only time in the factory’s history that these Polish place names would appear in German, it’s believed that this map was hung over his desk. Facing the map is a giant monument of enamel pots and pans, like those that were made in this factory. There are 1,200 pots—one for each Jewish worker that Schindler saved. Inside the monument, the walls are lined with the names on Schindler’s famous list. The creaky floorboards are intentional: a reminder that the Nazis knew every step you took.

Proceeding through the exhibit, you’ll learn more about everyday life—both for ghetto dwellers and for everyday non-Jewish Krakovians, including the Polish resistance (see the Home Army’s underground print shop). More eyewitness accounts relate the terrifying days of March 13 and 14, 1943, when the Podgórze ghetto was liquidated, sending survivors to the nearby Płaszów Concentration Camp. The replica of the Płaszów quarry, where inmates were forced to work in unimaginably difficult conditions, provides a poignant memorial for those who weren’t fortunate enough to wind up on Schindler’s list.

Now head all the way back down to the ground floor.

Ground Floor: Exhibits here capture the uncertain days near the end of the war in the summer of 1944, when Nazis arrested between 6,000 and 8,000 suspected saboteurs after the Warsaw Uprising, and sent them to Płaszów (see the replica of a basement hideout for 10 Jews who had escaped the ghetto); and later, when many Nazis had fled Kraków, leaving residents to await the Soviet Union’s Red Army (see the replica air-raid shelters). The Red Army arrived here on January 18, 1945—at long last, the five years, four months, and twelve days of Nazi rule were over. The Soviets caused their own share of damage to the city before beginning a whole new occupation that would last for generations...but that’s a different museum.

Finally, walk along the squishy floor—evoking how life for anyone was unstable and unpredictable during the Nazi occupation—into the Hall of Choices. The six rotating pillars tell the stories of people who chose to act—or not to act—when they witnessed atrocities. Think about the ramifications of the choices they made...and what you would have done in their shoes. The final room holds two books: a white book listing those who tried to help, and a black book listing Nazi collaborators. Exiting the museum, notice the portraits of Oscar Schindler’s workers who lived long and happy lives after the war.

Nearby: Before heading back to downtown Kraków, consider paying a visit to the superb—and very different—art museum that fills the buildings on the factory grounds, behind this main building (described next). Or, for a glass of wine, head just a few doors down from the museum to find the delightful Krakó Slow Wines (marked Lipowa 6F). This mellow, inviting wine bar and shop is well-stocked with wines mostly from Central and Eastern Europe (daily 10:00-22:00, mobile 669-225-222, www.krakoslowwines.pl).

Called “MOCAK” for short, this museum exhibits a changing array of innovative and thought-provoking works by contemporary artists, often with heavy themes tied to the surrounding Holocaust sites. With the slogan Kunst macht frei (“Art will set you free”—a pointed spin on the Nazis’ Arbeit macht frei concentration-camp motto), the museum occupies warehouse buildings once filled by Schindler’s workers. Now converted to wide-open, bright-white halls, the buildings house many temporary exhibits as well as two permanent ones (the MOCAK Collection in the basement, and the library in the smaller side building). Pick up the floor plan as you enter. It’s all well-described in English, and engaging even for those who don’t usually like modern art.

Cost and Hours: 10 zł, 24-zł combo-ticket with next-door Schindler’s Factory Museum, free on Tue, open Tue-Sun 11:00-19:00, closed Mon, last entry one hour before closing, Lipowa 4, tel. 12-263-4001, www.mocak.pl.

Along with the St. John Paul II pilgrimage sights (best suited for believers), there are other interesting sights outside of town—an impressive salt mine, a purpose-built communist town, and an unusual earthwork. All require a bus or tram ride to reach.

Pilgrims coming to Kraków eager to walk in the footsteps of St. John Paul II are sometimes disappointed by the low number of actual museums relating to the man in the city center (though the churches affiliated with him are dazzling). However, there are worthwhile sights outside the city: the John Paul II Sanctuary on the outskirts of Kraków; and the John Paul II Family Home Museum in the town of Wadowice, an hour’s drive away (and covered later).

The two biggest, most impressive JPII destinations are about four miles south of Kraków’s Old Town, in the Łagiewniki neighborhood. While the main attraction here for pilgrims is the John Paul II Sanctuary, historically and geographically you’ll come first to the Divine Mercy Sanctuary—so I’ve covered that first. The sights aren’t worth the trek for the merely curious, but they offer a glimpse of the powerful reverence and deep faith that characterizes the Polish people. If you’re a pilgrim—or think you might be one—visiting these sights can be worthwhile; to make the most of your time, consider hiring a driver or a local guide with a car (see here).

Getting There: Public transportation from central Kraków is workable, but not ideal. (As these connections are still in flux, it’s smart to ask about the best connection at the TI before making the trip.) The easiest public-transit route is to take tram #8 (which loops around the Old Town, including stops next to St. Francis Basilica at plac Wszystkich Świętych, and near Wawel Castle) to the Divine Mercy Sanctuary (Sanktuarium Bożego Miłosierdzia stop)—about 30 minutes. From the tram stop, you’ll huff a few minutes uphill along the wall to find the entrance to the complex. After touring the Divine Mercy sights, you can cross a footbridge to the St. John Paul II Sanctuary. A taxi or Uber from downtown costs around 30-40 zł one-way and takes 20-30 minutes.

This complex, built around a humble red-brick convent, honors the early-20th-century St. Faustina, who saw a miraculous vision of Jesus that became a powerful religious symbol for many Catholics. Today, pilgrims from around the world come here to revere the relics both of Faustina and of John Paul II (who advocated for her sainthood), and to learn more about her story from the convent’s present-day sisters—many of whom speak English.

Background: One cold and blustery evening in 1931, Sister Faustina Kowalska (1905-1938) answered the convent doorbell to find a beggar asking for some food. Faustina brought some soup to the man, who revealed his true nature: a figure of Jesus Christ clad in a white robe, with one hand raised in blessing, and the other touching his chest. Emanating from his chest were twin beams of light: red (representing blood, the life of souls) and white (water, which through baptism washes souls righteously clean). Transformed by her experience, Faustina worked with an artist to create a painted version of the image—called the Divine Mercy—which has been embraced by Polish Catholics as one of the most important symbols of their faith.

Always frail in health, Faustina died at 33—the same age as Jesus. The story of Faustina deeply moved a young Karol Wojtyła. When he became pope, he dedicated the first Sunday after Easter as the day of Divine Mercy worldwide. In 2000, he made his fellow Krakovian the first Catholic saint of the third millennium. To properly revere the newly important St. Faustina, a bold, futuristic church and visitors center was built alongside her original convent.

Cost and Hours: All three parts of the complex—the smaller original chapel, a replica of Faustina’s cell, and the huge, modern church, with its soaring bell tower—are free to enter, but donations are happily accepted. Each one has slightly different hours (listed later).

Visiting the Complex: Entering the complex through the side gate, you’ll come up a walkway with flags from around the world, and plaques translating the Divine Mercy’s message—“Jesus, I trust in you”—in dozens of languages.

Just before entering the original chapel, look up and to the right—the window with the flowers marks the cell where Faustina died. Inside the chapel (daily 6:00-21:15), the altar to the left of the main altar displays an early copy of Faustina’s Divine Mercy painting. Her relics are in the white case just below; in the white kneeler just in front of the chapel, notice the little reliquary holding one of her bones (which worshippers can embrace as they pray).

Leaving the chapel, turn left and go to the far end of the accommodations building. Enter the door on the right (follow signs for Cela Św. Siostry Faustyny) to find the replica of Faustina’s cell. While this is a newer building, here they’ve created Faustina’s convent cell, including many of her personal effects. Drop a coin in the slot for an evocative headphone description of these items, and of the vision of Jesus that put her convent on the map (usually open daily 8:30-18:00).

Dominating the campus is the futuristic, glass-and-steel main church. Consecrated by Pope John Paul II on his final visit to Poland in 2002, this building has several parts (daily 7:00-20:00). The lower level has a variety of small chapels, each one donated by Catholic worshippers in a different country (Germany, Hungary, Slovakia, and so on)—and each with a dramatically different style. The central chapel on this level has a modern altar and another bone of St. Faustina. Upstairs, the main sanctuary is a sleek cylindrical space with wooden sunbeams sharply radiating from the altar area. That altar—framed by the gnarled limbs of windblown trees, representing the suffering of human existence—contains a replica of the Divine Mercy painting, flanked by the woman who saw the vision (Faustina, on the right) and the Polish pope who made it a worldwide phenomenon (John Paul II, on the left).

Head back out to the terrace surrounding the church. The bold tower—as tall as St. Mary’s on Main Market Square, and with a statue of John Paul II at the bottom—has an elevator that you can ride up to a glassed-in viewpoint offering panoramas over the Divine Mercy campus, the adjacent John Paul II Sanctuary complex, and—on the distant horizon—the spires of Wawel Cathedral and Kraków’s Old Town. Near the base of the tower is a canopy where Mass is said on Divine Mercy Sunday each year, before a crowd of 100,000 who fill the fields below.

From here, it’s about a 15-minute walk to the next sight (you’ll pay a small fee to cross the “Bridge of Mercy,” which spans a scenic gorge).

This new complex, funded entirely by private donors, celebrates the life and sainthood of Kraków’s favorite son. Construction is ongoing, but for now there are at least two sections of the complex worth visiting: the sanctuary and museum.

Cost and Hours: Sanctuary—free, daily 7:30-19:00, until 18:00 in winter, www.sanktuariumjp2.pl; museum—7 zł, Wed-Sat 10:00-16:00, Sun 10:00-15:00, closed Mon-Tue.

Sanctuary of St. John Paul II: This hypermodern church is big and splendid. In the downstairs area, the central chapel features paintings of JPII’s papal visits to various pilgrimage sites, both in Poland (Częstochowa) and abroad (Fátima, Lourdes). Most of the chapels ringing the outside have different depictions of the Virgin Mary. Find the chapel that’s a replica of the St. Leonard’s Crypt under Wawel Cathedral—where a young priest named Karol Wojtyła celebrated his first Mass. In this chapel, you’ll see JPII’s empty papal tomb from the crypt beneath St. Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican. (When he became a saint, his remains—which, controversially, are kept in Rome rather than his homeland—were moved up into the main part of the church, and this simple grave marker was donated to this church.) You’ll also see a reliquary in the shape of a book with fluttering pages, holding a small amount of John Paul II’s blood (for the story of the book, see here). This blood was kept in secret by JPII’s personal secretary, only revealed after his death, when it was divvied up among a select few churches. In another chapel, you’ll find the tombs of a few recent cardinals; as they’re running out of space below Wawel Cathedral, this chapel is poised to handle the overflow. And in yet another chapel, you’ll see finely executed reliefs in rock salt, in the style of Wieliczka Salt Mine.

Head upstairs to the sleek, modern main sanctuary. The concrete structure supports large walls, providing a canvas for dynamic mosaics of Bible stories. Above the main altar, in the middle, you’ll see the Three Kings delivering their gifts to the Baby Jesus and the Virgin Mary—with St. John Paul II serenely overlooking the scene. In the back-left corner, a smaller chapel focuses on a painting of St. John Paul II; in the hazy background, you can see the dome of St. Peter’s at the Vatican (left) and the twin spires of St. Mary’s in Kraków (right)—driving home the point that although John Paul II belonged to the world, first and foremost he’s considered a son of Kraków and of Poland.

The sanctuary anchors a sprawling complex of conference facilities and other attractions for pilgrims. Poke around. The museum, described next, is the sight most worth visiting.

St. John Paul II Museum: This collects the many gifts bestowed on the beloved pope (African carved masks and ivory tusks; Latin American tapestries; the key to the city of Long Branch, New Jersey; and a pair of glass doves of peace given to him—perhaps with a touch of irony—by US Vice President Dick Cheney); ornate worship aids (chalices, crosses, and so on); and modern art that celebrates the modern pope and his life’s work. There are also personal items, from his papal ski gear to the place settings from his Vatican dinner table to his stylish red leather shoes. You’ll also see the throne from his last visit to Poland in 2002, and a replica of the humble room across the street from St. Francis Basilica where he stayed on visits back to his homeland.

Karol Wojtyła was born and lived up until age 18 in Wadowice (VAH-doh-veet-seh), about 30 miles (a one-hour drive) southwest of Kraków. As it’s roughly in the same direction as Auschwitz, a local guide or driver can help you connect both places for one busy day of contrasts. Visiting by public bus or minibus is possible (about 1.25 hours one-way); ask the TI for details.

The lovely town of Wadowice (about 20,000 people) has a quaint and beautifully restored main square with a pretty Baroque steeple. John Paul II pilgrims find it worth a visit to see the John Paul II Family Home Museum, which fills four floors of the tenement building where his family lived through his adolescence. You’ll explore a multimedia overview of the life and times of one of the newest Catholic saints, including rooms of the family home, a collection of clothing and other articles that belonged to JPII, photographs and video clips of his life and of the tumultuous period in which he lived, and plenty of interactive displays to bring the entire story to life. Admission is limited, and you’ll be accompanied the entire time. Ideally, time your visit to go with an English guide (typically 2/day, likely at 11:00 and 14:00—but confirm online or by phone); otherwise, you’ll join the Polish tour. Either way, the tour can be a bit rushed, with less time to linger over the exhibits than you might like (20 zł with a Polish guide, or 30 zł with English guide, free and crowded on Tue; open daily May-Sept 9:00-19:00, April and Oct 9:00-18:00, Nov-March 9:00-16:00, closed the last Tue of each month, last entrance 1.5 hours before closing, across the street from the town church at ulica Kościelna 7, tel. 33-823-2662, www.homejp2.com).

Wieliczka (veel-EECH-kah), a salt mine 10 miles southeast of Kraków, is beloved by Poles. Deep beneath the ground, the mine is filled with sculptures that miners have lovingly carved out of the salt. You’ll explore this unique gallery—learning both about the art and about medieval mining techniques—on a required tour. Though the sight is a bit overrated, it’s unique and practically obligatory if you’re in Kraków for a few days. In my experience with tour groups, about half the people love Wieliczka, while half feel it’s a waste of time—but it can be hard to predict which half you’re in. Read the description here carefully before you decide. And expect a lot of walking.

Cost and Hours: The standard “tourist route” costs 84 zł and is by guided tour only. The mine is open April-Oct 7:30-18:00, Nov-March 9:00-17:00 (these are last tour times). English-language tours leave every 30 minutes in the morning (10:00-13:00) and all day in summer (June-Sept), and otherwise depart hourly. They also have other routes that are more in-depth (such as the interactive “Miner’s Route,” where visitors wear coveralls and helmets and actually operate some of the old equipment); for details on these, see the website. The mine is in the town of Wieliczka at ulica Daniłowicza 10 (tel. 12-278-7302, www.kopalnia.pl).

You’ll pay an extra 10 zł for permission to use your camera—but be warned that flash photos often don’t turn out, thanks to the irregular reflection of the salt crystals. Dress warmly—the mine is a constant 57 degrees Fahrenheit. Before entering, you’ll have to check large bags and go through a security checkpoint.

Your ticket includes a dull mine museum at the end of the tour. It adds an hour to the mine tour and is discouraged by locals (“1.5 miles more walking, colder, more of the same”). Make it clear when you buy your ticket that you’re not interested in the museum.

You can buy your tickets—and an appointed entry time—at the Wieliczka Promotion Office, in Kraków’s Old Town (Mon-Fri 9:00-17:00, closed Sat-Sun, Wiślna 12a).

Getting There: The salt mine is 10 miles from Kraków. By far the easiest option is to hop on the train at Kraków’s main train station (track 3, 2/hour, 3 zł, takes 20 minutes, get off at Wieliczka Rynek-Kopalnia and walk 5-10 minutes to the mine). In a pinch, you can take bus #304 (at Kurniki stop across from church near Galeria Krakowska mall) or a minibus, but these take longer (40 minutes)—get details at the TI. Private drivers also make this trip (see here).

Background: Wieliczka Salt Mine has been producing salt since at least the 13th century. Under Kazimierz the Great, one-third of Poland’s income came from these precious deposits. Wieliczka miners spent much of their lives underground, leaving for work before daybreak and returning after sundown, rarely emerging into daylight. To pass the time, and to immortalize their national pride and religiosity in art, 19th-century miners began to carve figures, chandeliers, and eventually even an elaborate chapel out of the salt. Until a few years ago, the mine still produced salt. Today’s miners—about 400 of them—primarily work on maintaining the 200 miles of chambers. This entire network is supported by wooden beams (because metal would rust).

Visiting the Mine: From the lobby, your guide leads you 380 steps down a winding staircase. From this spot you begin a 1.5-mile stroll, generally downhill (more than 800 steps down altogether), past 20 of the mine’s 2,000 chambers (with signs explaining when they were dug), finishing 443 feet below the surface. When you’re done, an elevator beams you back up.

The tour shows how the miners lived and worked, using horses who spent their whole adult lives without ever seeing the light of day. It takes you through vast underground caverns, past subterranean lakes, and introduces you to some of the mine’s many sculptures (including one of Copernicus—who actually visited here in the 15th century—as well as an army of salt elves, and this region’s favorite son, St. John Paul II). Your jaw will drop as you enter the enormous Chapel of St. Kinga, carved over three decades in the early 20th century. Look for the salt-relief carving of the Last Supper (its 3-D details are astonishing, considering it’s just six inches deep). You’ll end your visit with a five-minute multimedia show.

While advertised as two hours, your tour finishes in a deep-down shopping zone 1.5 hours after you started (they hope you’ll hang out and shop). Note when the next elevator departs (just 3/hour), and you can be outta there on the next lift. Zip through the shopping zone in two minutes, or step over the rope and be immediately in line for the great escape (you’ll be escorted quite some distance to the elevator, into which you’ll be packed like mine workers).

Nearby: Near the parking lot, you’ll see the “Graduation Tower,” a modern fort-like structure with a wooden walkway up top. The tower is designed to evaporate and then condense the supposedly very healthy brine from deep underground. The resulting moist, salty air is used to treat patients with lung problems. While locals are actually prescribed visits here, for most tourists it’s not worth the extra money.

Nowa Huta (NOH-vah HOO-tah, “New Steel Works”), an enormous planned workers’ town, offers a glimpse into the stark, grand-scale aesthetics of the communists. Because it’s five miles east of central Kraków and a little tricky to see on your own, skip it unless you’re determined—it can be tricky to appreciate. But architects and communist sympathizers may want to make a pilgrimage here.

Getting There: Tram #4 goes from near Kraków’s Old Town (catch the tram on the ring road near Kraków’s main train station, at the Dworzec Główny stop) along John Paul II Avenue (aleja Jana Pawła II) to Nowa Huta’s main square, plac Centralny (about 30 minutes total), then continues a few minutes farther to the main gate of the Tadeusz Sendzimir Steelworks—the end of the line. From there it returns to plac Centralny and back to Kraków.

Tours: True to its name, Mike Ostrowski’s Crazy Guides is a loosely run operation that takes tourists to Nowa Huta in genuine communist-era vehicles (mostly Trabants and Polski Fiats). If you’ve got an interest in the history—and would enjoy spending the day careening around the streets of Kraków in a car that feels like a cardboard box with a lawnmower engine—hire one of their laid-back hipster guides (139 zł/person for 2.5-hour “communism tour” of Nowa Huta; 179 zł/person for 4-hour “communism deluxe” tour that also includes lunch at a milk bar and a visit to their period-decorated communist apartment; other options available—described on website, mobile 500-091-200, www.crazyguides.com, info@crazyguides.com). If you’re already hiring a local guide in Kraków, consider paying a little extra to add a couple of hours for a short side-trip by car to Nowa Huta.

Background: Nowa Huta was the communists’ idea of paradise. It’s one of only three towns outside the Soviet Union that were custom-built to showcase socialist ideals. (The others are Dunáujváros—once called Sztálinváros—south of Budapest, Hungary; and Eisenhüttenstadt—once called Stalinstadt—near Brandenburg, Germany.) Completed in just 10 years (1949-1959), Nowa Huta was built primarily because the Soviets felt that smart and sassy Kraków needed a taste of heavy industry. Farmers and villagers were imported to live and work in Nowa Huta. Many of the new residents, who weren’t accustomed to city living, brought along their livestock (which grazed in the fields around unfinished buildings). For commies, it was downright idyllic: Dad would cheerily ride the tram into the steel factory, mom would dutifully keep house, and the kids could splash around at the man-made beach and learn how to cut perfect red stars out of construction paper. But Krakovians had the last laugh: Nowa Huta, along with Lech Wałęsa’s shipyard in Gdańsk, was one of the home bases of the Solidarity strikes that eventually brought down the regime. Now, with the communists long gone, Nowa Huta remains a major suburb of Poland’s cultural capital, with a whopping 200,000 residents.

Touring Nowa Huta: Nowa Huta’s focal point used to be known simply as Central Square (plac Centralny), but in a fit of poetic justice, it was recently renamed for the anticommunist Ronald Reagan. A map of Nowa Huta looks like a clamshell: a semicircular design radiating from Central/Reagan Square. Numbered streets fan out like spokes on a wheel, and trolleys zip workers directly to the immense factory.

Believe it or not, the inspiration for Nowa Huta was the Renaissance (which, thanks to the textbook Renaissance design of the Cloth Hall and other landmarks, Soviet architects considered typically Polish). Notice the elegantly predictable arches and galleries that would make Michelangelo proud. The settlement was loosely planned on the gardens of Versailles (comparing aerial views of those two very different sites—both with axes radiating from a central hub—this becomes clear). When first built (before it was layered with grime), Nowa Huta was delightfully orderly, primly painted, impeccably maintained, and downright beautiful...if a little boring. It was practical, too: Each of the huge apartment blocks is a self-contained unit, with its own grassy inner courtyard, school, and shops. Driveways (which appear to dead-end at underground garage doors) lead to vast fallout shelters.

Today’s Nowa Huta—while gentrifying—is a far cry from its glory days. Wander around. Poke into the courtyards. Reflect on what it would be like to live here. It may not be as bad as you imagine. Ugly as they may seem from the outside, these buildings are packed with happy little apartments filled with color, light, and warmth.

The wide boulevard running northeast of Central/Reagan Square, now called Solidarity Avenue (aleja Solidarności, lined with tracks for tram #4), leads to the Tadeusz Sendzimir Steelworks. Originally named for Lenin, this factory was supposedly built using plans stolen from a Pittsburgh plant. It was designed to be a cog in the communist machine—reliant on iron ore from Ukraine, and therefore worthless unless Poland remained in the Soviet Bloc. Down from as many as 40,000 workers at its peak, the steelworks now employs only about 10,000. Today there’s little to see other than the big sign, stern administration buildings, and smokestacks in the distance. Examine the twin offices flanking the sign—topped with turrets and a decorative frieze inspired by Italian palazzos, these continue the Renaissance theme of the housing districts.

Another worthwhile sight in Nowa Huta is the Lord’s Ark Church (Arka Pana, several blocks northwest of Central/Reagan Square on ulica Obrońców Krzyża). Back when he was archbishop of Kraków, Karol Wojtyła fought for years to build a church in this most communist of communist towns. When the regime refused, he insisted on conducting open-air Masses before crowds in fields—until the communists finally capitulated. Consecrated on May 15, 1977, the Lord’s Ark Church has a Le Corbusier–esque design that looks like a fat, exhausted Noah’s Ark resting on Mount Ararat—encouraging Poles to persevere through the floods of communism. While architecturally interesting, the church is mostly significant as a symbol of an early victory of Catholicism over communism.

On a sunny day, the parklands west of the Old Town are a fine place to get out of the city and commune with Krakovians at play. On the outskirts of town is the Kościuszko Mound, a nearly perfectly conical hill erected in 1823 to honor Polish and American military hero Tadeusz Kościuszko. The mound incorporates soil that was brought here from battlefields where the famous general fought, both in Poland and in the American Revolution. Later, under Habsburg rule, a citadel with a chapel was built around the mound, which provided a fine lookout over this otherwise flat terrain. And more recently, the hill was reinforced with steel and cement to prevent it from eroding away. You’ll pay to enter the walls and walk to the top—up a curlicue path that makes the mound resemble a giant soft-serve cone—and inside you’ll find a modest Kościuszko museum. While not too exciting, this is a pleasant place for an excursion on a nice day.

Cost and Hours: 12 zł, includes museum, mound open daily 9:00-dusk, Fri-Sun until 23:00 in May-Sept, museum open daily 9:30-18:30—less off-season, café, tel. 12-425-1116, www.kopieckosciuszki.pl.

Getting There: Ride tram #1 or #6 (from in front of the Wyspiański Pavilion or the main post office) to the end of the line, called Salvator. From here, you can either follow the well-marked path uphill for 20 minutes, or hop on bus #100 to the top (runs at :10 past each hour).

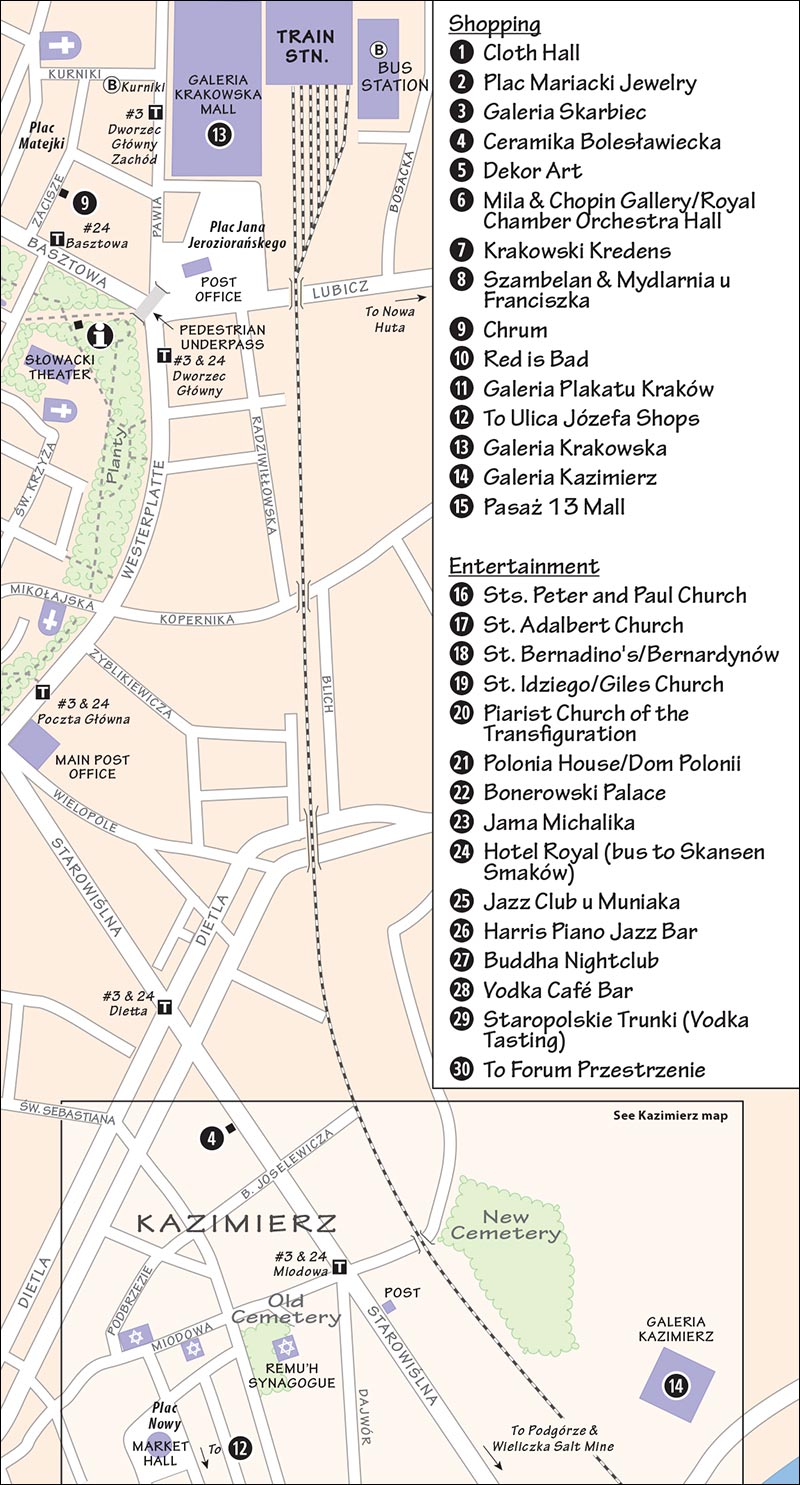

Two of the most popular Polish souvenirs—amber and pottery—come from areas far from Kraków. You won’t find any great bargains on those items here, but several shops specializing in them are listed below. Somewhat more local are the many wood carvings you’ll see.

The Cloth Hall, smack-dab in the center of the Main Market Square, is the most convenient place to pick up any Polish souvenirs. It has a great selection at respectable prices (summer Mon-Fri 9:00-18:00, Sat-Sun 9:00-15:00, sometimes later; winter Mon-Fri 9:00-16:00, Sat-Sun 9:00-15:00).

Here are some other souvenir ideas, and neighborhoods or streets that are particularly enjoyable for browsing.

The popular amber (bursztyn) you’ll see sold around town is found on northern Baltic shores; if you’re also heading to Gdańsk, wait until you get there (for more on amber, see here). One unique alternative that’s a bit more local is “striped flint” (krzemień pasiasty), a stratified stone that’s polished to a high shine. It’s mined in a very specific subregion near Kraków, and has become popular recently among Hollywood celebrities. Each piece has its own unique wavy, sandy patterns.

Jewelry shops abound in the Old Town. For a good selection of striped flint, amber, and other jewelry, try the no-name shop on plac Mariacki, the little square facing the side entrance of St. Mary’s Church; they also have a selection of Polish folk costumes in the basement (at #9). A few more jewelry and design shops cluster along Sławkowska street, which runs north from the Main Market Square. Galeria Skarbiec (“Treasury”), two blocks south of the Main Market Square, is another good choice, with a stylish, upscale vibe (Grodzka 35).

“Polish pottery,” with distinctive blue-and-white designs, is made in the region of Silesia, west of Kraków (mostly in the town of Bolesławiec). But, assuming you won’t be going there, you can browse one of the shops in Kraków. Ceramika Bolesławiecka, on a busy urban street between the Old Town and Kazimierz, has a tasteful, affordable selection of pottery that’s oriented more for locals than tourists (closed Sun, Starowiślna 37). In the Old Town—and with inflated prices to match—two places face each other across Sławkowska street, just a block north of the Square: Dekor Art at #11 and Mila at #14.

Krakowski Kredens is a handy, well-curated shop for overpriced but good-quality traditional foods from Kraków and the surrounding region, Galicia. While the deli case in the back is a pricey place to shop for a picnic (head for a supermarket instead), this is a good chance to stock up on souvenir-quality Polish foods for the folks back home. They have several locations around Kraków—and elsewhere in Poland—but one handy branch is just steps south of the Main Market Square down Grodzka, at #7 (www.krakowskikredens.pl).

Szambelan, a block south of the Main Market Square, is a fun concept for vodka lovers: Peruse the giant casks of three dozen different flavored vodkas, buy an empty bottle, and they’ll fill and seal it to take home (Gołębia 2 at the corner with Bracka).

Mydlarnia u Franciszka, with a few locations around Kraków (including a handy one just south of the Main Market Square at Gołębia 2), sells a variety of fragrant local soaps, lotions, shampoos, and other cosmetics, some produced locally.

Two creative shops in the Old Town sell souvenir T-shirts that are a step up in quality (and price) from the generic shops on the square. Chrum specializes in locally themed ironic T-shirts (closed Sun, across the street from the Barbican at plac Matejki 3, www.chrum.com), while Red is Bad sticks with tasteful, classic Polish eagles and flags on quality materials (just west of the Square at Szewska 25, www.redisbad.pl).

The relatively undiscovered, traffic-free Stolarska street—just a block off of the Main Market Square—is a fine place to stroll day or night, and to browse for gifts. (For more on this street, see here in “Eating in Kraków.”) Wander the street from north (Small Market Square) to south (Dominican Church) and window-shop. A few fun places are in the covered arcade on the left, after the Herring Embassy. One of the most interesting is Galeria Plakatu Kraków, a print, poster, and postcard shop with a wide variety of engaging images, from commie-retro to contemporary arts to unique Polish variations on American movie posters (closed Sun, Stolarska 8-10). Nearby are an antique bookstore and a pottery art gallery.

As the epicenter of Kraków’s hipster scene, Kazimierz is the best place in town to browse one-off boutiques (both design and fashion). Several good options line up along ulica Józefa, mostly concentrated along a two-block stretch. Head just one block south from plac Nowy on Estery street, turn right, and keep an eye out for these options (mostly on the left side of the street): Blazko, at #11, has some modern, colorful jewelry, handmade right on the premises. A few doors down Galerie d’Art Naïf features fascinating works by untrained artists, and (next door) Deccoria Galeria feels like a junk shop, cluttered with handmade jewelry, art, accessories, and vintage clothes. Next are Panon Nonchalant, with Polish fashion, and a vintage shop. Art Factory, at #9, is worth a browse for colorful jewelry, accessories, and housewares by local designers. Pracownia (“Lab”), farther down and also at #9, sells handmade art, jewelry, and clothes. And more clothes by Polish designers are across the street at Nuumi Boutique (#14).

A couple of blocks away, just off plac Wolnica, is another great spot for local design, housewares, jewelry and casual fashion (i.e., creative T-shirts): Idea Fix and The Hive Store, which share a storefront at Bocheńska 7 (daily).

Two enormous shopping malls lie just beyond the tourist zone. The gigantic Galeria Krakowska, with 270 shops, shares a square with the train station (Mon-Sat 9:00-22:00, Sun 10:00-21:00, has a kids’ play area upstairs from the main entry). Only slightly smaller is Galeria Kazimierz (Mon-Sat 10:00-21:00, Sun until 20:00, just a few blocks east of the Kazimierz sights, along the river at Podgórska 24). A small but swanky mall called Pasaż 13 is a few steps off the southeast corner of the Main Market Square, where Grodzka street enters the Square. Enter the mall under the balcony marked Pasaż 13. You’ll find a cool brick-industrial interior, with upscale international chains...and not much that’s Polish (Mon-Sat 11:00-21:00, Sun until 17:00).

As a town full of both students and tourists, Kraków has plenty of fun options, especially at night.

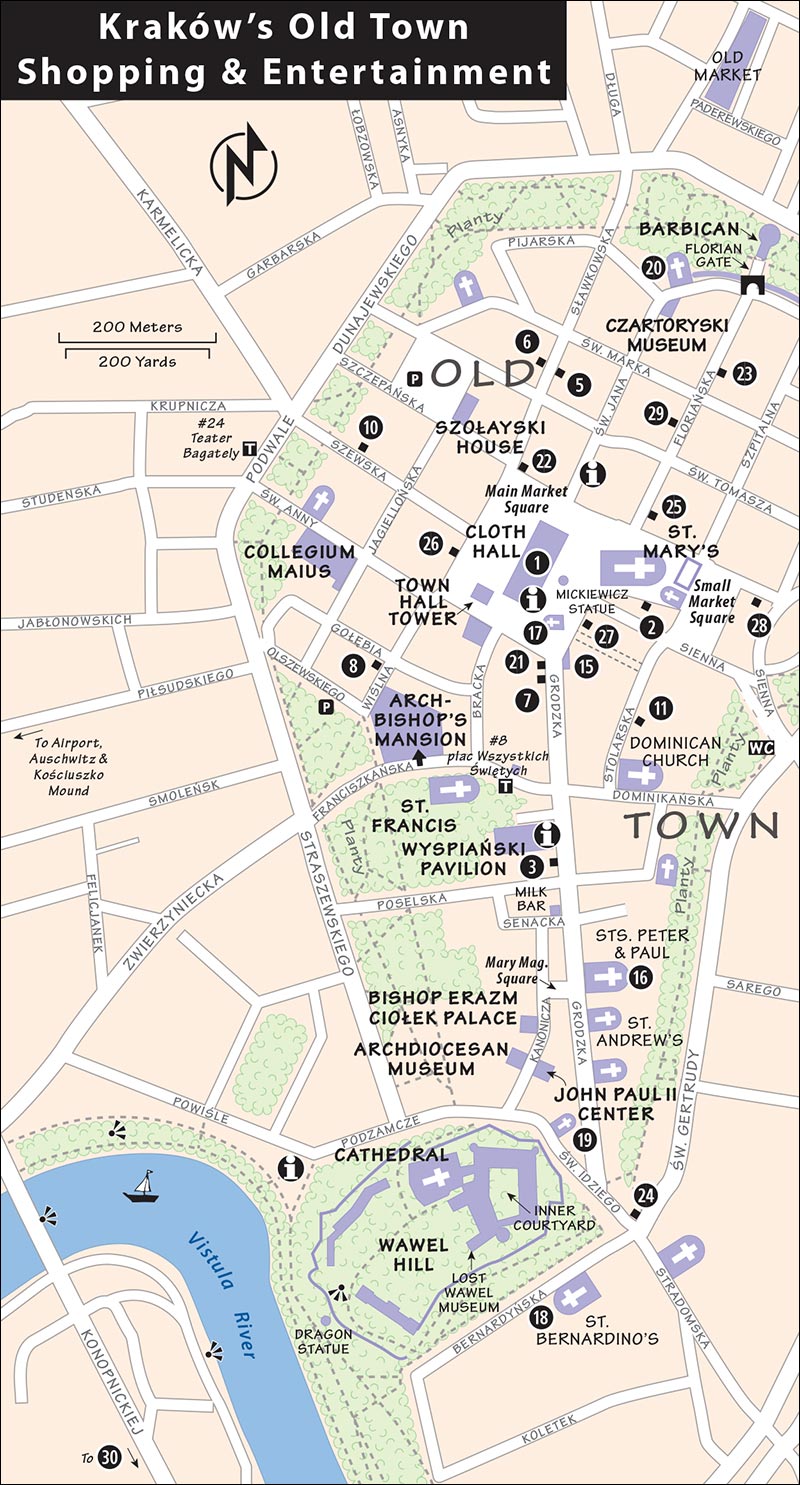

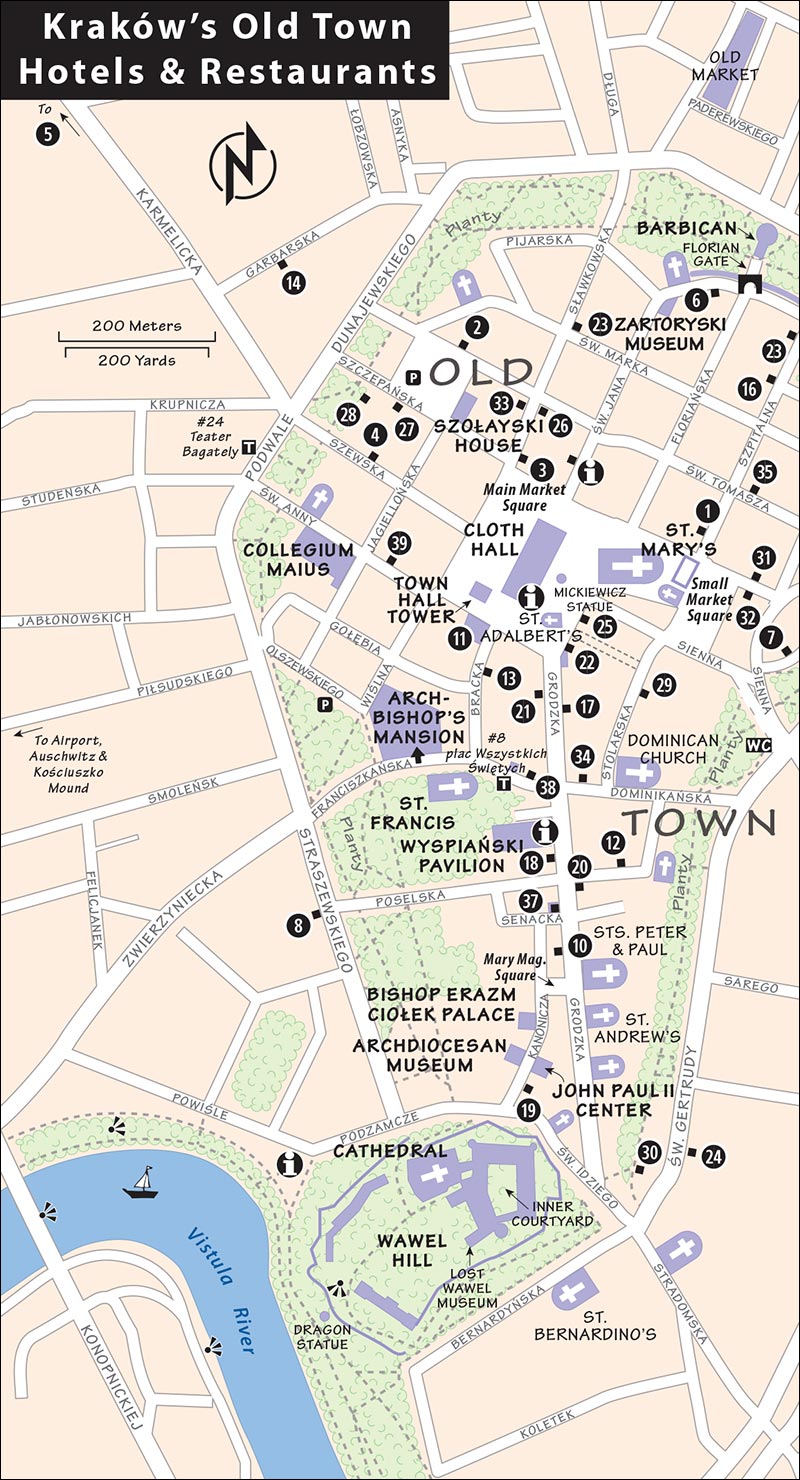

For locations of the following places, see the map on here.

Intoxicating as the Square is by day, it’s even better at night...pure enchantment. Have a meal or nurse a drink at an outdoor café, or just grab a bench and enjoy the scene. There’s often live al fresco music coming from somewhere (either at restaurants, at a temporary stage set up near the Town Hall Tower, or from talented buskers). You could spend hours doing slow laps around the Square after dark, and never run out of diversions. For a great view over the Square at twilight, nurse a drink at Café Szał—on the Cloth Hall’s upper terrace (long hours, enter through Gallery of 19th-Century Polish Art).

You’ll find a wide range of musical events, from tourist-oriented Chopin concerts and classical “greatest hits” selections in quaint old ballrooms and churches, to folk-dancing shows, to serious philharmonic performances. Several companies offer competing concerts; some of the best-established include www.cracowconcerts.com, www.newculture.pl, www.facebook.com/orkiestrasm, and www.orfeusz.eu. The free, monthly Karnet cultural-events book lists everything (also online at www.karnet.krakow.pl). Because the offerings change from week to week, inquire locally about what’s on during your visit. Hotel lobbies are stocked with fliers, but to get all of your options, visit the TI north of the Square on ulica Św. Jana, which specializes in cultural events (they can book tickets for most concerts with no extra fee, and can tell you how to get tickets for the others).

Popular Classical Concerts: The three main choices are organ concerts in churches (usually at 17:00); orchestral or chamber music; or Chopin (either can happen anytime between 18:00 and 20:00). The going rate for any concert is 60 zł. Many are held in churches (such as Sts. Peter and Paul on ulica Grodzka, St. Adalbert on the Square, St. Bernadino’s/Bernardynów near Wawel Castle, St. Idziego/Giles near Wawel Castle, or the Piarist Church of the Transfiguration at the northern end of the Old Town). You’ll also find concerts in fancy mansions on or near the Main Market Square (including the Polonia House/Dom Polonii at #14, near ulica Grodzka; the Chopin Gallery—also billed as the Royal Chamber Orchestra Hall—just up Sławkowska street from the Square at #14; and the Bonerowski Palace near the top of the Square at ulica Św. Jana 1). Occasionally in summer, they’re also held in various gardens around town (July-Aug only, as part of a festival).

Folk Music: Two different venues present dinner shows in the old center. At both, a small, hardworking ensemble of colorfully costumed Krakovian singers, dancers, and musicians put on a fun little folk show. While the food, the space, and the clientele are all quite tired, it’s a nice taste of Polish folk traditions—and the performers try hard to involve members of the audience in the polkas and circle dances. One option is in the historic Jama Michalika, with its dusty old Art Nouveau interior right along Floriańska street (85 zł includes dinner; Wed, Fri, and Sun at 19:00; Floriańska 45, mobile 604-093-570, www.cracowconcerts.com). A similar option is in the more modern Tradycyja Restaurant, right on the Main Market Square (at #15; 60 zł for just the show, or 120 zł to add dinner; Sat at 19:00; mobile 602-850-900, www.newculture.pl).

For a more serious folk music performance—and to really make an evening of it—consider a show in a more rustic setting just outside of town. The restaurant Skansen Smaków, filling a log cabin-like building, has shows each Thursday night. You’ll meet the bus at the Hotel Royal near Wawel Castle at 18:30, ride to the restaurant, have a traditional Polish feast during the show, then be brought back home to the Old Town at 22:00 (100 zł, book ahead, tel. 600-349-429, www.skansensmakow.pl).

Kraków has a surprisingly thriving jazz scene. Several popular clubs hide on the streets surrounding the Main Market Square (open nightly, most shows start around 21:30, sometimes free or a cover of 10-25 zł for better shows). Jazz Club u Muniaka is the most famous and best for all-around jazz in a sophisticated cellar environment (ulica Floriańska 3, tel. 12-423-1205). Harris Piano Jazz Bar, right on the Square (at #28), is more casual and offers a mix of traditional and updated “fusion” jazz, plus blues (tel. 12-421-5741, www.harris.krakow.pl).

The entire Old Town is crammed with nightclubs and discos pumping loud music on weekends. On a Saturday, the pedestrian streets can be more crowded at midnight than at noon. However, with the exception of the jazz clubs mentioned earlier, most of the nightspots in the Old Town are garden-variety dance clubs, completely lacking the personality and creativity of the Kazimierz nightspots described next. Worse, to save money, young locals stand out in front of nightclubs to drink their own booze (BYOB), rather than pay high prices for the drinks inside—making the streets that much more crowded and noisy. For low-key hanging out, people choose a café on the Square; otherwise, they head for Kazimierz.

In addition to the Harris Piano Jazz Bar (listed earlier), two places on the Square worth checking out are near the southeast corner. At #6, head into the passage to find the Buddha nightclub, with comfy lounge sofas under awnings in an immaculately restored old courtyard. For something funkier and even more local, go down the passage at #12, which runs a surprisingly long distance through the block. Soon you’ll start to see tables for the Herring Embassy; you’ll eventually emerge at Stolarska street, a still-enjoyable but far less touristy scene (for more on the Herring Embassy and Stolarska, see here).

If you have (or would like to cultivate) an appreciation for vodka, stop by the Vodka Café Bar, serving more than 100 types of vodkas, liquors, and hard drinks. You can buy a tasting flight board with six small shots; they’ll help you narrow down your options (usually around 30 zł for the flight, more for top-shelf vodkas). It’s a mellow, uncluttered space that lets you focus on the vodka and the company (Mon-Thu 15:00-24:00, Fri-Sun 13:00-24:00, Mikołajska 5).

Aside from the Old Town’s gorgeous Square, Kraków’s best area to hang out after dark is Kazimierz. Although this is also the former Jewish quarter, the Jewish Sabbath has nothing to do with the bar scene here. You can, however, still hear traditional Jewish music called klezmer. For tips on enjoying a concert of klezmer music, see the sidebar.

Squeezed between centuries-old synagogues and cemeteries are wonderful hangouts running the full gamut from sober and tasteful to wild and clubby. The classic recipe for a Kazimierz bar: Find a dilapidated old storefront, fill it with ramshackle furniture, turn the lights down low, pipe in old-timey jazz music from the 1920s, and sprinkle with alcohol. Serves one to two dozen hipsters. After a few clubs of this type caught on, a more diverse cross-section of nightspots began to move in, including some loud dance clubs. The whole area is bursting with life—it’s the kind of place where people just spontaneously start dancing.

On and near Plac Nowy: The highest concentration of bars ring the plac Nowy market square. While most of these are nondescript, a few stand out. Fronting the square, Kolory has a pleasant Parisian brasserie ambience (Estery 10). Circling to the right, you’ll spot Plac Nowy 1, which specializes in Polish microbrews and upmarket pub grub in a bright, sleek (and arguably “un-Kazimierz”) setting. Spinning about 90 more degrees to the right, look for a branch of the Poland-wide Pijalnia Wódki i Piwa chain—part of the trend for 4/8 bars (that’s 4 zł for a shot of vodka, 8 zł for a bar snack such as herring). Tucked in the corner just to the right of that is the easy-to-miss entrance for Atelier, which hides a relaxed, minimalist, art-gallery interior with cushy sofas and a hidden garden (plac Nowy 7 1/2). Le Scandale is all black leather and serves tapas, Italian fare, and cocktails; don’t miss the big garden in the back (plac Nowy 9). And at the end of this block, Alchemia, one of the first—and still one of the best—bars in Kazimierz, is candlelit, cluttered, and claustrophobic, with cave-like rooms crowded with rickety old furniture, plus a cellar used for live performances (Estery 5, www.alchemia.com.pl).