ST. JOHN PAUL II AND PILGRIMAGE SIGHTS

Map: Kraków’s Old Town Shopping & Entertainment

Map: Kazimierz Entertainment & Nightlife

Map: Kraków’s Old Town Hotels & Restaurants

Map: Kazimierz Hotels & Restaurants

Kraków is easily Poland’s best destination: a beautiful, old-fashioned city buzzing with history, enjoyable sights, tourists, and college students. Even though the country’s capital moved from here to Warsaw 400 years ago, Kraków remains Poland’s cultural and intellectual center. Of all the Eastern European cities laying claim to the boast, “the next Prague,” Kraków is for real.

What’s so special about it? First off, Kraków is simply charming; more than any town in Europe, it seems made for aimless strolling. And its historic walls and former moat corral an unusually full range of activities and interests: bustling university life; thought-provoking museums; breathtaking churches that evoke a powerful faith (and include many sights relating to Poland’s favorite son, St. John Paul II); sprawling parks that invite you to just relax; vivid Jewish heritage sights; a burgeoning foodie and nightlife scene; and compelling side-trips to the most notorious Holocaust site anywhere (Auschwitz-Birkenau), a communist-planned workers town, and a mine filled with salty statues. With so many opportunities to learn, to have fun, or to do both at once, it’s no surprise that Kraków has become the darling of Polish tourism.

Don’t skimp on your time in Kraków. It takes a minimum of two days to experience the city, and a third or fourth day lets you dig in and consider a world of fascinating side-trips.

Almost everyone coming to Kraków also visits the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp Memorial—and should. As it’s about an hour and a half away, this demands the better part of a day to fully appreciate (either as a round-trip from Kraków, or en route to or from another destination). Visiting Auschwitz requires a reservation, which can be hard to get. For all the details, see the next chapter.

If you have only two full days (the “express plan”), start off with my self-guided walk through the Old Town and a quick stroll up to Wawel Castle, then head over to the Schindler’s Factory Museum and wind down your day in Kazimierz. Your second day is for a side-trip to Auschwitz. This plan gives you an enticing once-over-lightly, but leaves almost no time for entering the sights.

More time buys you the chance to relax, enjoy, and linger: Tackle the Old Town and Wawel Castle on the first day, Kazimierz and museums of your choice on the second day, and Auschwitz (and other side-trips) with additional days. If you have a special interest, you could side-trip to the St. John Paul II pilgrimage sights on the outskirts of town, or to the communist architecture of the Nowa Huta suburb. Wieliczka Salt Mine is another crowd-pleasing, half-day option.

Regardless of how long you stay, your evening choices are many and varied: Savor the Main Market Square over dinner or a drink, take in a jazz show, do a pub crawl through the city’s many youthful bars and clubs (best in Kazimierz), or enjoy traditional Jewish music and cuisine (also in Kazimierz).

Kraków (Poles say KROCK-oof, but you can say KRACK-cow; it’s sometimes spelled “Cracow” in English) is mercifully compact, flat, and easy to navigate. While the urban sprawl is big (with 757,000 people), the tourist’s Kraków feels small—from the main square, you can walk to just about everything of interest in less than 15 minutes. Just to the south is Poland’s main river, the Vistula (Wisła, VEES-wah).

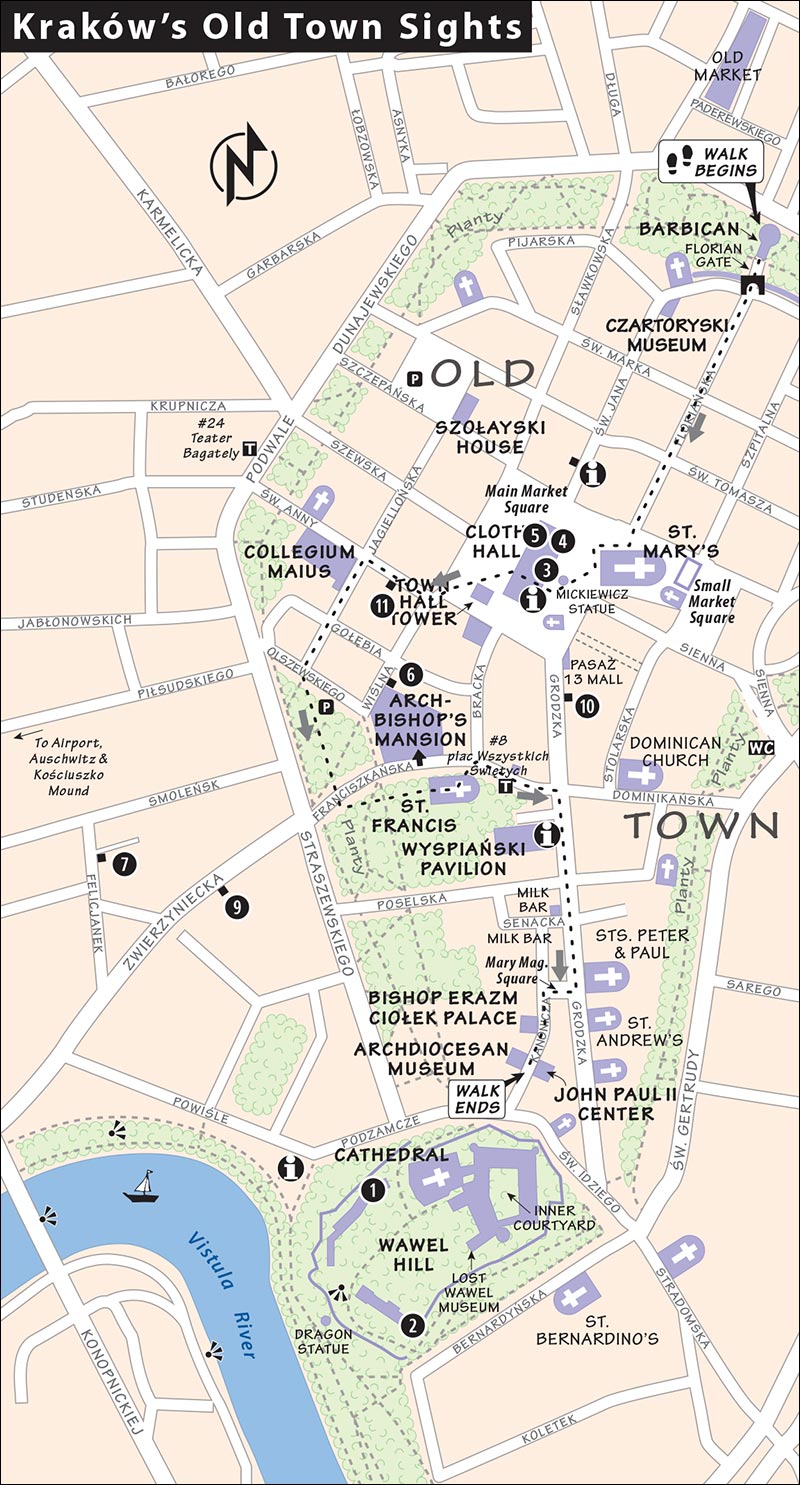

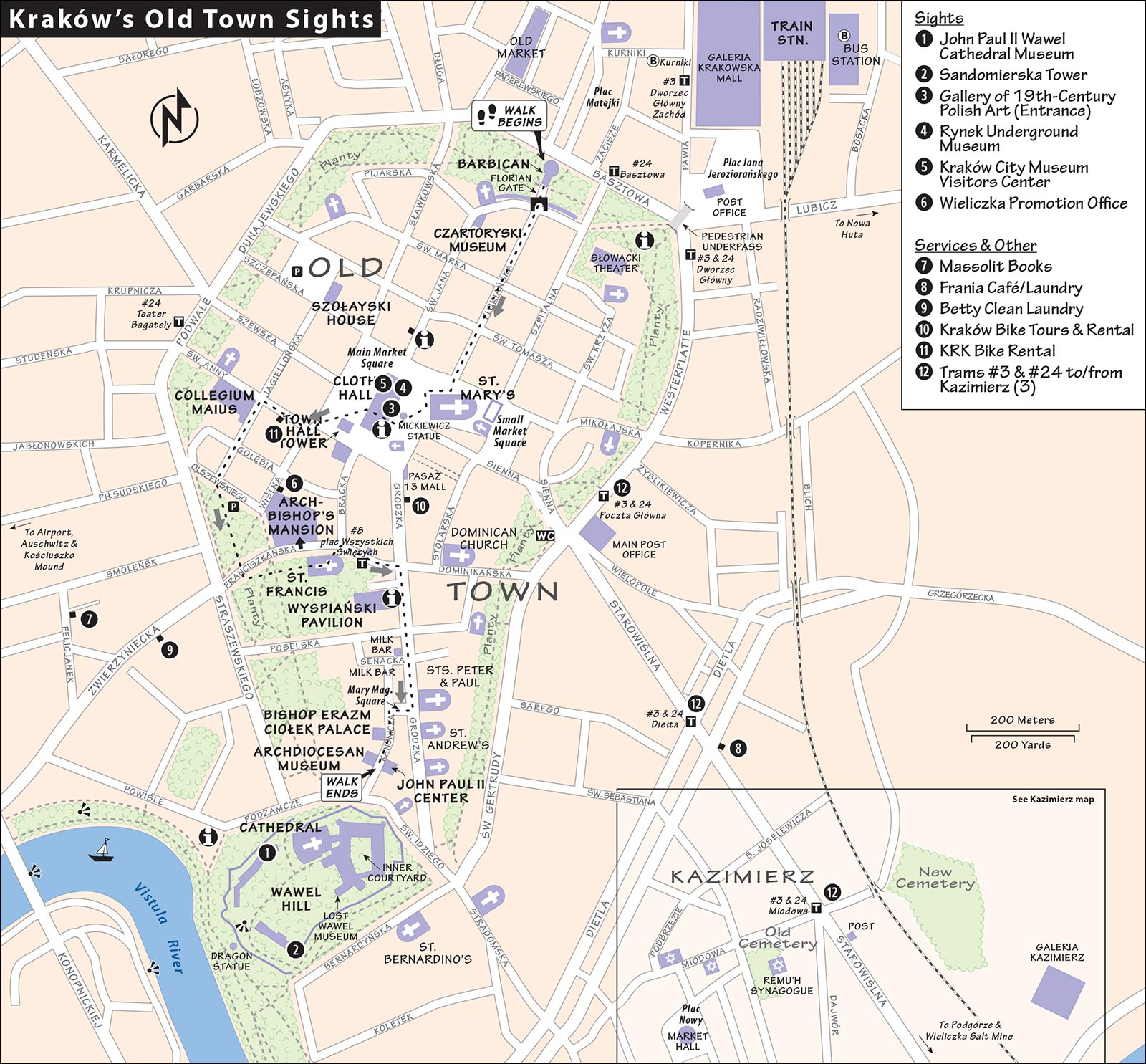

Most sights—and almost all recommended hotels and restaurants—are in the Old Town (Stare Miasto, STAH-reh mee-AH-stoh), which is surrounded by a greenbelt called the Planty (PLAHN-tee). In the center of the Old Town lies the Main Market Square (Rynek Główny, REE-nehk GWOHV-nee)—it’s such an important landmark, I call it simply “the Square.” At the Old Town’s northeast corner, just outside the ring road, is the main train station. And at the southern end of the Old Town, on the riverbank, is the hill called Wawel (VAH-vehl)—with a historic castle, museums, and Poland’s national church.

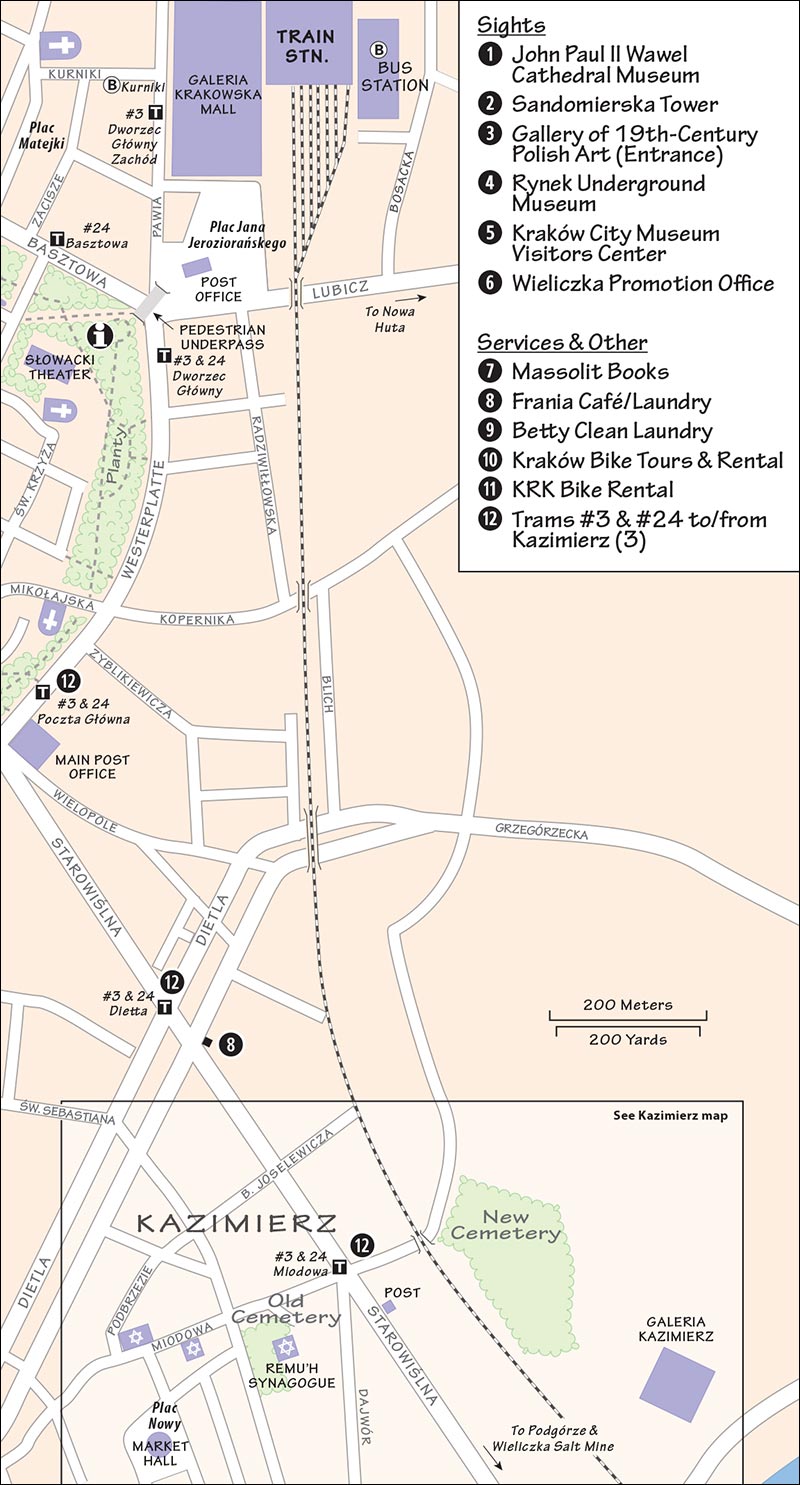

About a 20-minute walk (or quick tram/taxi ride) southeast of the Square is the neighborhood called Kazimierz (kah-ZHEE-mehzh)—with Jewish landmarks and Holocaust sites (including the Schindler’s Factory Museum) and the city’s best foodie and nightlife area.

A few more attractions are just beyond the core, including the St. John Paul II pilgrimage sights (in the Łagiewniki neighborhood), the communist-planned town of Nowa Huta, Wieliczka Salt Mine, and the Kościuszko Mound.

Kraków has many helpful TIs, called InfoKraków (www.infokrakow.pl). Five branches are in or near the Old Town (all open daily May-Sept 9:00-19:00, Oct-April 9:00-17:00, unless otherwise noted):

• In the Planty park, between the main train station and Main Market Square (in round kiosk at ulica Szpitalna 25, tel. 12-354-2720)

• On ulica Św. Jana, just north of the Main Market Square (specializes in concert tickets, daily year-round 9:00-19:00, at #2, tel. 12-354-2725)

• In the Cloth Hall right on the Main Market Square (tel. 12-354-2716)

• In the Wyspiański Pavilion, just south of the Square on ulica Grodzka (daily 9:00-17:00, plac Wszystkich Świętych 3, not at the window but inside the building, tel. 12-616-1886)

• Just west of Wawel Hill (also covers the entire region, Powiśle 11, tel. 12-354-2710)

Other TI branches are in Kazimierz (daily 9:00-17:00, ulica Józefa 7, tel. 12-354-2728) and the airport (daily 9:00-19:00, tel. 12-285-5341).

Note that the TIs sell tickets only for one walking-tour company, See Kraków; for additional options, see “Tours in Kraków,” later, and look around online.

Sightseeing Pass: The TI’s Kraków Tourist Card includes admission to 40 city museums (basically everything except the Wawel Hill sights and Wieliczka Salt Mine)—but admissions are so cheap, it’s unlikely you’d save money with the card. Given how walkable Kraków is, the version that does not include public transit (70 zł/3 days) is a better value for most people than the one that does (100 zł/2 days, 120 zł/3 days).

Warning: Many private travel agencies, room-booking services, and tour operators masquerade as TIs, with deceptive blue-and-white i signs. If I haven’t listed them in this section, they’re not a real TI.

Kraków City History Museum’s Visitor Center: Tucked in the Cloth Hall (on the quiet western side) is a little information office operated by the Kraków City History Museum, where you can book tickets, without a line, for the popular Schindler’s Factory Museum. If you anticipate crowds at the Schindler museum, drop by this office to book an entry time (daily 10:00-19:00, until 20:00 in summer, at #1).

Kraków’s main train station (called “Kraków Główny,” KROCK-oof GWOHV-nee) sits just northeast of the Old Town, adjoining the sprawling Galeria Krakowska shopping mall. The station and the mall face a broad plaza (plac Dworcowy) across the ring road from the Planty park and Old Town. My recommended Old Town hotels are within about a 15-minute walk, or a quick tram or taxi ride. (If you’re staying in the Old Town, the tram doesn’t save you much time, but could cut down on how far you have to haul your bags. If you’re staying in Kazimierz—a 30-minute walk away—the tram is definitely worthwhile.)

Whether you’re arriving or departing, get oriented to the station’s layout. The main concourse has all of the amenities: ATMs, lockers (under the big schedule board between the ticket windows), WCs, takeaway coffee, a handy Biedronka minisupermarket, and a shopping mall. From this area, five numbered escalators lead up to the corresponding train platforms. Tucked under these escalators, find a long row of numbered ticket windows (some for domestic tickets only, others for domestic and international—check signs before you line up; a few are marked with UK flags to denote English-speaking staff). In the middle of the row of ticket windows (between #11 and #12) is the PKP Passenger Service Center, which may have a longer wait but is more likely to have staff who speak English (no extra fee).

Getting Between the Station and Downtown: The easiest option is to take a taxi (they wait in the parking lot on the station’s rooftop—go up the stairs or elevator from your platform). The usual metered rate to downtown is a reasonable 10-15 zł; only take a taxi marked with a company name and telephone number. You can also summon an Uber, which is often cheaper (for more on Uber, see “Getting Around Kraków,” later).

If you prefer to walk or take a tram, you first must navigate the Galeria Krakowska shopping mall. Begin by following Exit to the City signs. Once inside the mall, continue straight ahead. To walk, follow Old Town signs, which eventually route you to the left. You’ll pop out at a big plaza where you’ll continue straight, taking the broad ramp down into a pedestrian underpass beneath the ring road. Emerging at the other side, bear right up the ramp into the Planty. The Main Market Square is straight ahead (you’ll see the twin spires of St. Mary’s Church).

If you’d rather take a tram, continue straight ahead through the mall, following signs to Pawia street. Emerging here, you’ll see the Dworzec Główny Zachód tram stop. Buy a ticket from the machine and hop on tram #3 in the direction of Nowy Bieżanów. This tram stops at the eastern edge of the Old Town (Poczta Główna stop) before continuing to Kazimierz (Miodowa stop). (Note: Avoid the tram stop you’ll see signposted inside the station—this is served only by trams that don’t go anywhere near the Old Town or Kazimierz.)

There is a shortcut to avoid going through the sprawling and sometimes congested mall: The modern train station is attached to the old station (the yellow building facing the big plaza, now hosting art exhibitions) by a sidewalk under a green canopy. This can save you a little walking (and a lot of shopping temptations). It’s tricky to find from inside the station: Go behind the Biedronka supermarket, near track 1, and exit toward Lubicz street. Walk up the ramp and follow the green canopy to the plaza.

To get from town to the station (or to the bus station behind it), head to the northeast corner of the Planty, take the underpass beneath the ring road, walk across the plaza and into the Galeria Krakowska mall, and once inside, follow signs to Railway Station and Station Hall.

The bus station is directly behind the main train station. When arriving by bus, it’s easiest to get into town by first heading into the train station, then continuing through it, following the above directions.

To get to the bus station from the Old Town (such as to catch a bus to Auschwitz), follow the directions above, then walk all the way through to the far end of the train station area (past platform 5, exit marked for bus station). Exiting the train station, escalate up to the bus terminal (marked MDA Dworzec Autobusowy). Inside are the standard amenities (lockers and WCs), domestic and international ticket windows, and an electronic board showing the next several departures. Some bus departures, marked on the board with a G, leave from the upper (gorna) stalls, which you can see out the window. Other bus departures, marked with a D, leave from the lower (dolna) stalls; to find these, use the stairs or the elevator right in the middle of the bus terminal. Note that some minibuses, such as those to Auschwitz, also leave from, or near, this station (though the buses and minibuses that go to the Wieliczka Salt Mine leave from nearby streets—see here).

Centrum signs lead you into the Old Town—you’ll know you’re there when you hit the ring road that surrounds the Planty park. Parking garages surround the Old Town. Your hotelier can advise you on directions and parking.

The modern John Paul II Kraków-Balice Airport is about 10 miles west of the center (airport code: KRK, airport info: tel. 12-295-5800, www.krakowairport.pl). The easiest way downtown is to hop on the slick and speedy train (follow signs to the platform across the street from the arrivals area, 8 zł, buy ticket from machine or from conductor on board, 2/hour, 18 minutes to Kraków’s main train station—see arrival instructions earlier, under “By Train”). Alternatively, public bus #208 or (at night) #902 leaves from right in front of the arrivals area (Kolej do Centrum signs, 4 zł, goes to main bus station—see arrival instructions earlier, under “By Bus,” 50-minute trip depending on traffic). There’s also a taxi stand in front of the terminal (ask about the fare up front—rates vary, but official cabs should not exceed 90 zł, more expensive at night, about 30 minutes). You can also request an Uber, or arrange a taxi transfer in advance (such as with recommended driver Andrew Durman, listed later, under “Tours in Kraków”).

Many budget flights—including those on Wizz Air and Ryanair—use the International Airport Katowice in Pyrzowice (Międzynarodowy Port Lotniczy Katowice w Pyrzowicach, airport code: KTW, www.katowice-airport.com). This airport is about 18 miles from the city of Katowice, which is about 50 miles west of Kraków. Direct buses run sporadically between Katowice Airport and Kraków’s main train station area (50 zł, trip takes 1.75 hours, generally scheduled to meet incoming flights). You can also take the bus from Katowice Airport to Katowice’s train station (hourly, 50 minutes), then take the train to Kraków (hourly, 1.5 hours). Wizz Air’s website is useful for figuring out your connection: www.wizzair.com.

Exchange Rate: 1 złoty (zł, or PLN) = about 25 cents; 4 zł = about $1.

Country Calling Code: 48 (see here for dialing instructions)

Sightseeing Schedules: Some sights are closed on Monday (including the Gallery of 19th-Century Polish Art, Szołayski House, and a few museums in Kazimierz), but many sights are open (including the churches and Jagiellonian University Museum, and in Kazimierz, all of the Jewish-themed sights). On Saturday, most of Kazimierz’s Jewish-themed sights are closed. Before heading out, check the “Kraków at a Glance” sidebar on here. Also be aware of days that certain sights are free: On Sunday, the National Museum branches (including the Gallery of 19th-Century Polish Art in the Cloth Hall) are free, but some are open limited hours. And on Monday, Schindler’s Factory Museum is free (and especially crowded), as are two of the sights at Wawel Castle (but open only in the morning April-Oct).

Post Office: The main post office (Poczta Główna) is at the intersection of Starowiślna and the Westerplatte ring road, a few blocks east of the Main Market Square (Mon-Fri 8:30-20:30, Sat 8:00-15:00, closed Sun). In summer, look for a kitschy postal wagon on the Main Market Square, where you can mail postcards.

Bookstore: For an impressive selection of new and used English books, try Massolit Books, just west of the Old Town. They also have a café with drinks and light snacks, and a good children’s section (Sun-Thu 10:00-20:00, Fri-Sat 10:00-21:00, ulica Felicjanek 4, tel. 12-432-4150, www.massolit.com).

Laundry: Frania Café, halfway between the Old Town and Kazimierz, is an inviting café/pub with ample washers and dryers, relaxing ambience, free Wi-Fi, a full bar serving espresso drinks and laundry-themed hard drinks, long hours, and a friendly staff (21 zł/load self-service, 29 zł for them to do it for you in 2-3 hours—consider dropping it off on your way to Kazimierz and picking it up on the way back, likely open daily 10:30-24:00, ulica Starowiślna 26, mobile 783-945-021).

Betty Clean is a full-service laundry that’s slightly closer to the Old Town, but pricey (about 13 zł/shirt, 22 zł/pants, takes 24 hours, 50 percent more for express 3-hour service, Mon-Fri 7:30-19:30, Sat 8:00-15:30, closed Sun, just outside the Planty park at ulica Zwierzyniecka 6, tel. 12-423-0848).

Kraków’s top sights and best hotels are easily accessible by foot. You’ll need wheels only if you’re going to outlying areas (Kazimierz, Nowa Huta, John Paul II pilgrimage sights, and so on).

Trams and buses zip around Kraków’s urban sprawl. The same tickets work system-wide and can be purchased at most kiosks, or at the machines you’ll see at most stops (these accept coins and small bills). You can also buy tickets on board—most trams have machines (coins only); otherwise, you’ll buy your ticket from the driver and pay a bit more. For a good route planner, see www.jakdojade.pl.

A bilet jednoprzejazdowy, which covers any single journey (including transfers), costs 3.80 zł. However, many journeys you’re likely to take—such as between the Old Town and Kazimierz—are likely to be brief, so you’ll save a bit by buying a 20-minute ticket (20-minutowy) for 2.80 zł. You can also get longer-term tickets for 24 hours (15 zł), 48 hours (24 zł), and 72 hours (36 zł)—though unless your accommodations are a tram ride away from the sights, you’re unlikely to need these. These prices are for a “one-zone” ticket, which covers almost everything of interest in Kraków (including Nowa Huta, the St. John Paul II pilgrimage sights, and the Kościuszko Mound)—unless you’re headed for the airport or Wieliczka Salt Mine, which are beyond the city limits and require a slightly more expensive aglomeracyjny ticket (4 zł for a single journey). Always validate your ticket when you board the bus or tram (24-, 48-, and 72-hour tickets must be validated only the first time you use them).

Tram #3 is particularly handy. It goes from the side of the train station (Dworzec Główny Zachód) to the ring road in front of the station (Dworzec Główny), then stops at the eastern edge of the Old Town (Poczta Główna, at the main post office) before continuing to Kazimierz (Miodowa is at the north end, near ulica Szeroka; Św. Wawrzyńca is at the south end, near the old tram depot) and Podgórze, near Schindler’s Factory Museum (plac Bohaterow Getta). Tram #24 is also handy: It stops at the western edge of the Old Town (Teatr Bagately), then loops around the northern edge to stop near the Barbican (Stary Kleparz) before meeting up with tram #3 in front of the train station (Dworzec Główny) and continuing on to Kazimierz and Podgórze (same stops as listed above).

Only take cabs that are clearly marked with a company logo and telephone number. Kraków taxis start at 7 zł and charge about 3 zł per kilometer. Rides generally cost less than 20 zł, but can take longer than you’d expect: Due to the Old Town’s many traffic restrictions and pedestrian zones, a “short ride across town” may require looping all the way around the ring road. You’re more likely to get the fair metered rate by calling or hailing a cab, rather than taking one waiting at tourist spots. To call a cab, try Radio Taxi (tel. 19191).

If you’re comfortable using Uber back home, try it here. As in the US, Uber is typically cheaper than official taxis (though prices can spike during busy “surge” periods). In my experience, Polish Uber drivers (and their cars) are a bit less polished and professional than back home—but they’re cheap. When requesting a ride on your app, you can choose between the basic UberPop and the more professional UberSelect for a few zlotys more.

The riverfront bike path is enticing on a nice day; the Planty park, while inviting, can be a bit crowded for biking. Kraków Bike Tours rents a wide variety of new, good-quality bikes (10 zł/first hour, cheaper per hour for longer rentals, 50 zł/day, 60 zł/24 hours, daily 9:00-19:00, until 20:00 in summer, just off the Square at Grodzka 2; see listing later, under “Tours in Kraków”). Nearby, KRK Bike Rental rents basic, cheaper bikes (9 zł/hour, 50 zł/24 hours, April-Oct daily 9:00-21:00, less in bad weather, closed Nov-March, ulica Św. Anny 4, mobile 509-267-733, www.krkbikerental.pl).

Hiring a guide in Kraków is fun and affordable, and makes a huge difference in your experience. I’ve enjoyed working with three in particular, any of whom can show you the sights in Kraków and also have cars for day-tripping into the countryside: Tomasz Klimek (350 zł/half-day, 500 zł/day, slightly more with a car, mobile 605-231-923, tomasz.klimek@interia.pl); Marta Chmielowska (350 zł/4 hours, 500 zł/day, same prices by foot or car, can be more for larger groups and for long-distance trips, mobile 603-668-008, martachm7@gmail.com); and Anna Bakowska (same prices as Marta, mobile 604-151-293, www.leadertour.eu, leadertour@wp.pl). I wouldn’t bother hiring a guide for the trip to Auschwitz (which generally costs 600-700 zł)—only official Auschwitz guides can legally give tours onsite, so you’ll wind up joining one of the tours once there; instead, it’s a better value to hire a driver (like Andrew, listed next).

Since Kraków is such a useful home base for day trips, it can be handy to splurge on a private driver for door-to-door service. Andrew (Andrzej) Durman, a Pole who lived in Chicago and speaks fluent English, is a gregarious driver, translator, miracle worker, and all-around great guy. While not an officially licensed tour guide, Andrew is an eager conversationalist and loves to provide lively commentary while you roll. Although you can hire Andrew for a simple airport transfer or an Auschwitz day trip, he also enjoys tackling more ambitious itineraries, from helping you track down your Polish roots to taking you on multiple-day journeys around Poland and beyond (prices are for up to 4 people if you book directly: 400 zł to Auschwitz, 250 zł to Wieliczka Salt Mine, 80 zł for transfer from Kraków-Balice Airport, 500 zł for transfer from Katowice Airport, 600 zł for an all-day trip into the countryside—such as into the High Tatras or to track down your Polish roots near Kraków, more to cover gas costs for trips longer than 100 km one-way; long-distance transfers for up to 4 people to Prague, Budapest, Vienna, or Berlin for 1,800 zł—or 200 zł extra if he picks you up there; also available for multiday trips—price negotiable, all prices higher for bigger van, tel. 12-411-5630, mobile 602-243-306, www.tour-service.pl, andrew@tour-service.pl). If he’s busy, Andrew may send you with one of his English-speaking colleagues, Bartek or Matthew.

Local guide Marta Chmielowska’s husband, Czesław (a.k.a. Chester), can also drive you to nearby locations (300 zł for all-day trip to Auschwitz for 1-2 people, 350 zł for 3-8 people; 220 zł to Wieliczka Salt Mine, including waiting time, or a very long day combining Wieliczka and Auschwitz for 550 zł; 1,700 zł for a transfer to Prague; to book, see Marta’s contact information, earlier).

Various companies run daily city walking tours in English in summer. Most do a three-hour tour of the Old Town as well as a three-hour tour of Kazimierz, the Jewish district (most charge about 50 zł per tour, depending on company). Three people can hire their own great local guide for about the same amount of money. Because the scene is continually evolving, it’s best to pick up local fliers (the TI works exclusively with one company, See Kraków, but hotel reception desks generally have more options), then choose the one that fits your interests and schedule. You’ll also see ads for “free” tours—which are, of course, not really free (the guide gets paid only if you tip generously).

In this stealth-foodie city, you have multiple good options. Eat Polska—which does a marvelous job of connecting food to culture and history, making the experience equal parts informative and delicious—does top-notch, insightful food tours (at 13:00, 290 zł, 4 hours) and vodka tours with food pairings (at 17:00, 260 zł, 3.5 hours; for details on either, see www.eatpolska.com). Urban Adventures, a bit more casual, does evening food walks that basically assemble a full meal with a little sightseeing thrown in (at 18:00, 310 zł, 3 hours, www.urbanadventures.com).

This irreverent company offers tours to the communist suburb of Nowa Huta and other outlying sights. For details, see here.

Kraków Bike Tours is a well-established operation that runs daily four-hour bike tours in English, with 25 stops in the Old Town, Kazimierz, and Podgórze (90 zł, May-Sept daily at 10:00 and 15:00, spring and fall only 1/day at 12:00, confirm schedule and meet tour at their office down the passage at Grodzka 2—right at the bottom of the Square, mobile 510-394-657, www.krakowbiketour.com). They also offer Segway tours.

As Kraków is so easily enjoyed on foot, taking a bus tour doesn’t make much sense in town. But they can be handy for reaching outlying sights. Various tour companies run big-bus itineraries to Auschwitz (6 hours), Wieliczka Salt Mine (4 hours), and other regional side-trips (each itinerary around 120-180 zł).

Given the difficulty of reserving your own appointment at Auschwitz (explained in the next chapter), one of these bus tours—which include a guided tour of the camp—may be your most convenient option. See Kraków (which has a monopoly at the TI, www.seekrakow.com) and Discover Cracow (www.discovercracow.com) both use smaller 19-seat minibuses. They sometimes offer hotel pick-up, which seems convenient, but you’ll waste a lot of time driving around the city to other hotels. Cracow City Tours (www.cracowcitytours.com) uses larger 50-seat buses with a central pick-up point (on plac Matejki, across the ring road from the Barbican, at the north end of the Old Town).

At any company, the on-bus guiding is hit-or-miss but largely irrelevant anyway—since you’ll be handed off to an official Auschwitz guide once at the camp. Note that the many tour offices and faux-TIs you’ll see around town simply sell tickets for these companies. If you waited too long to reserve at Auschwitz and are desperate to get in at short notice, try dropping in to various agencies around town to see if any of these outfits has space.

You’ll see (and hear) horse-drawn buggies that trot around Kraków from the Main Market Square. The going rate is a hefty 100 zł for a 30-minute tour. After dark, they’re all lit up like fanciful Cinderella coaches—a memorable scene, all lined up in front of St. Mary’s Church.

Several outfits around town (including on the Square) offer tours on a golf cart with recorded commentary. Given the limits on car traffic in the old center, this can be a handy way to connect the sights for those with limited mobility. Generally you’ll pay about 160 zł for a 45-minute tour around the Old Town; to extend the trip to Kazimierz, it’s 300 zł; and adding the Podgórze former Jewish ghetto and Schindler’s Factory Museum costs a total of 380 zł (these prices are for the entire golf cart, up to 5 people). Some outfits also do point-to-point transfers within town for 50 zł.

Andy Steves (Rick’s son) runs Weekend Student Adventures (WSA Europe), offering 3-day and 10-day budget travel packages across Europe including accommodations, skip-the-line sightseeing, and unique local experiences. Locally guided and DIY unguided options are available for student and budget travelers in 12 of Europe’s most popular cities, including Kraków (guided trips from €199, see www.wsaeurope.com for details).

▲Barbican (Barbakan) and City Walls

▲▲Planty

The Old Market (Stary Kleparz)

Florian Gate (Brama Floriańska)

▲Floriańska Street (Ulica Floriańska)

▲▲St. Mary’s Church (Kościół Mariacki)

▲▲▲Main Market Square (Rynek Główny), a.k.a. “The Square”

Jagiellonian University and the Collegium Maius

▲▲St. Francis Basilica (Bazylika Św. Franciszka)

Mary Magdalene Square (Plac Św. Marii Magdaleny)

Kanonicza Street (Ulica Kanonicza)

(See “Kraków’s Old Town Sights” map, here.)

Most of Kraków’s major sights are conveniently connected by this self-guided walk. This route is known as the “Royal Way” because the king used to follow this same path when he returned to Kraków after a journey. After the capital moved to Warsaw, most kings still used Wawel Cathedral for important events. In fact, from 1320 to 1795, nearly every Polish king traversed Kraków’s Royal Way at least twice: on the day he was crowned and on the day he was buried. You could sprint through this walk in about an hour and a half (less than a mile altogether), but it’s much more fun if you take it like the kings did...slowly.

• Begin just outside the main gate (the Florian Gate) at the north end of the Old Town.

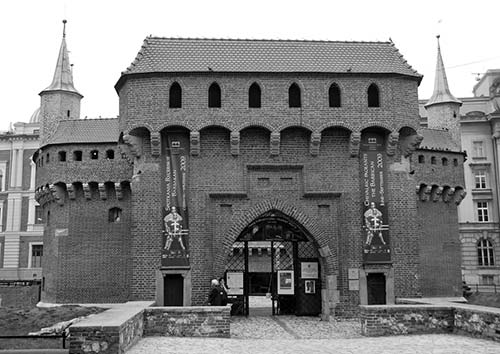

Tatars—those mysterious and terrifying invaders from Central Asia—destroyed Kraków in 1241. To better defend their city, Krakovians built this wall. The original rampart had 47 watchtowers and eight gates. (You can see a bronze model of the wall just to the right of the tower.)

The big, round defensive fort standing outside the wall is the Barbican—built to provide extra fortification to weak sections—namely, the gates. Imagine how it looked in 1500, when the Barbican stood outside the town moat with a long bridge leading to the Florian Gate—the city’s main entryway. Today you can pay to scramble along the passages and fortifications of the Barbican, though there’s little to see inside, other than a small but good exhibit giving you a sense of how the walls were designed (8 zł, April-Oct daily 10:30-18:00, closed Nov-March). The same ticket also lets you climb up onto the surviving stretch of Old Town walls flanking the Florian Gate (entry from inside walls).

• The greenbelt in which the Barbican sits is called the...

By the 19th century, Kraków’s no-longer-necessary city wall had fallen into disrepair. As the Austrian authorities were doing all over their empire, they decided to tear down what remained, fill in the moat, and plant trees. (The name comes not from the English “plant,” but from the Polish plantovac, or “flat”—because they flattened out this area to create it.) Today, the Planty is a beautiful park that stretches 2.5 miles around the entire perimeter of Kraków’s Old Town. To give your Kraków visit an extra dimension, consider a quick bike ride around the Planty (best early in the morning, when it’s less crowded) with a side-trip along the parklike riverbank near Wawel Castle; you’ll see bike-rental places around the Old Town, including the two mentioned on here.

Circle around the left side of the Barbican. On your left, keep an eye out for a unique monument depicting an elderly, bearded man in the corner of a huge frame. This honors Jan Matejko, arguably Poland’s most beloved painter, who specialized in giant-scale epic historical scenes that would easily fill this frame. We’ll hear Matejko’s name several more times on this walk.

As you continue around the Barbican, look down to see the much lower ground level around its base—making it easy to imagine that the Planty was once anything but flat.

• Across the busy street from the Barbican, standing in the middle of the long park, is the...

This memorial honors one of the most important battles in the history of a nation that has seen more than its share: the Battle of Grunwald on July 15, 1410, when Polish and Lithuanian forces banded together to finally defeat the Teutonic Knights, who had been running roughshod over the lands along the Baltic. (For more on the battle and the knights, see here.) Lying dramatically slain at the base of this monument, like a toppled Goliath, is the defeated Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights—German crusaders who had originally been brought to Poland as mercenaries. It’s easy to see this vanquished statue as a thinly veiled metaphor for one of Poland’s powerful, often domineering neighbors that the Poles stood up to—and defeated. When the Nazis took power here, this statue was one of the first things they tore down. When they left, it was one of the first things the Poles put back up.

• If you’d like to see a slice of Krakovian life, side-trip one block to the left of the monument, to the local farmers market.

The colorful Old Market offers a refreshing dash of today’s Kraków that has nothing to do with history or tourism. It’s just lots of hardscrabble people selling what they grow or knit, and lots of others buying. Wander around as if on a cultural scavenger hunt. Find the freshest doughnuts (pączki), the most popular bakery, the villager selling slippers she knitted, and the old man with the smoked cheese (Mon-Sat 7:00-18:00—but busiest and most interesting in the morning, closed Sun).

• Now retrace your steps to the Barbican, and enter the Old Town by walking through the...

As you approach the gate, look up at the crowned white eagle—representing courage and freedom—the historic symbol of the Polish people.

Inside the gate, notice the little chapel on the right with a replica of the famous Black Madonna of Częstochowa, probably the most important religious symbol among Polish Catholics. The original, located in Częstochowa (70 miles north of Kraków), is an Eastern Orthodox-style icon of mysterious origin with several mystical legends attached to it. After the icon’s believed role in protecting a monastery from Swedish invaders in the mid-17th century, it was named “Queen and Protector of Poland.”

Once through the gate, look back at it. High above is St. Florian, patron of the fire brigade. As fire was a big concern for a wooden city of the 15th century, Florian gets a place of honor.

You’ll often see traditionally clad musicians near the gate, performing their lilting folk melodies for tips.

• You’re standing at the head of Kraków’s historic (and now touristic) gamut...

Hanging on the inside of the city wall in both directions is a makeshift art gallery, where—traditionally—starving students hawk the works they’ve painted at the Academy of Fine Arts (across the busy street from the Barbican). These days, the art is so kitschy, this stretch of the town’s fortification is nicknamed “The Wailing Wall.” The entrance to get on top of the wall—covered by the Barbican ticket—is at the end of this starving artists’ gallery. If you detoured even farther along the wall, soon you’d reach the eclectic Czartoryski Museum, home to a rare Leonardo da Vinci oil painting (see here).

Now begin strolling down Floriańska street (floh-ree-AHN-skah). Notice that all over town, storefronts advertising themselves as “tourist information” offices are actually tourist sales agencies (legitimate TIs are listed on here). And money-exchange counters can be thieves with an address. (Do the arithmetic—the buying and selling rates should be within 6 percent or so, and there should be no fee.) Along with the fast-food joints, also notice some uniquely Polish snacks: The various pizza and kebab windows also sell zapiekanki—a toasted baguette with toppings, similar to a French bread pizza. Or, for an even quicker bite, buy an obwarzanek (ring-shaped, bagel-like roll, typically fresh) from a street vendor; many still use their old-fashioned blue carts.

About halfway down the first block, on the left (at #45, round green sign), look for Jama Michalika (“Michael’s Cave”). This dark, atmospheric café, popular with locals for its coffee and pastries, began in 1895 as a simple bakery in a claustrophobic back room. Around the turn of the 20th century, this was a hangout of the Młoda Polska (Young Poland) movement—the Polish answer to Art Nouveau (explained on here). The walls are papered with sketches from poor artists—local bohemians who couldn’t pay their tabs. In 1915, this was home to the first Polish cabaret. Today that stage is used by a folk troupe that performs traditional music and dance with dinner many evenings (pick up the flier; also see listing under “Entertainment in Kraków,” here). Poke around inside this circa-1900 time warp and appreciate this unique art gallery. Consider having coffee and dessert here, or a cigar in the charming smokers’ bar in front.

About a block farther down, at #20 (on the right), Staropolskie Trunki (“Old Polish Drinks”) offers an education in vodka—with as much tasting as you’d like. It’s a friendly little place with a long bar and countless local vodkas and liquors—all open and ready to be tasted. Best of all, there’s a cheery local barista to talk you through the experience (four tastes for 10 zł with a fun explanation that amounts to a private tour, buy a bottle and the tastes are free, daily 10:00-24:00).

• Continue into the Main Market Square, where you’ll run into...

A church has stood on this spot for 800 years. The original church was destroyed by the first Tatar invasion in 1241, but all subsequent versions—including the current one—have been built on the same foundation. You can look down the sides to see how the Main Market Square has risen about seven feet over the centuries.

How many church towers does St. Mary’s have? Technically, the answer is one. The shorter tower belongs to the church; the taller one is a municipal watchtower, from which you’ll hear a bugler playing the hourly hejnał song. According to Kraków’s favorite legend, during that first Tatar invasion, a town watchman saw the enemy approaching and sounded the alarm. Before he could finish the tune, an arrow pierced his throat—which is why, even today, the hejnał stops suddenly partway through. Today’s buglers—12 in all—are firemen first, musicians second. Each one works a 24-hour shift up there, playing the hejnał four times on the hour—with one bugle call for each direction. (It’s even broadcast on national Polish radio at noon.) While you’re in Kraków, you’ll certainly hear one of these tiny, hourly, broken performances.

To see one of the most finely crafted Gothic altarpieces anywhere, it’s worth paying admission to enter the church. The front door is open 14 hours a day and is free to those who come to pray, but tourists use the door around the right side (buy your ticket across the little square from this door).

Cost and Hours: 10 zł, Mon-Sat 11:15-17:45, Sun 14:00-17:45 (these are last-entry times). The famous wooden altarpiece is open between noon and 18:00; try to be here by 11:50 for the ceremonial opening (Mon-Sat) or at 18:00 for the closing (except on Sat, when it’s left open for the service on Sun).

Visiting the Church: Inside, you’re struck by the lavish decor. This was the church of the everyday townspeople, built out of a spirit of competition with the royal high church at Wawel Castle. At the altar is one of the best medieval woodcarvings in existence—the exquisite, three-part altarpiece by German Veit Stoss (Wit Stwosz in Polish). Carved in 12 years and completed in 1489, it’s packed with emotion rare in Gothic art. Get as close as you can and study the remarkable details. Stoss used oak for the structural parts and linden trunks for the figures. When the altar doors are closed, you see scenes from the lives of Mary and Jesus. The open altar depicts the Dormition (death—or, if splitting theological hairs, heavenly sleep) of the Virgin. The artist catches the apostles around Mary, reacting in the seconds after she collapses. Mary is depicted in three stages: life leaving her earthly body, being escorted to heaven by Jesus, and (at the very top) being crowned in heaven. The six scenes on the sides are the Annunciation, birth of Jesus, visit by the Three Magi, Jesus’ Resurrection, his Ascension, and Mary becoming the mother of the apostles at Pentecost.

There’s more to St. Mary’s than the altar. While you’re admiring this church’s art, notice the flowery Neo-Gothic painting covering the choir walls. Stare up into the starry, starry blue ceiling. As you wander around, consider that the church was renovated a century ago by three Polish geniuses from two very different artistic generations: the venerable positivist Jan Matejko and his Art Nouveau students, Stanisław Wyspiański and Józef Mehoffer (we’ll learn more about these two later on our walk). The huge silver bird under the organ loft in back is that symbol of Poland, the crowned white eagle.

Tower Climb: You may be able to climb up the 239 stairs to the top of the taller tower to visit the hejnał fireman. While it’s a huff—with some claustrophobic stone stairs, followed by some steep, acrophobic wooden ones—the view up top is the best you’ll find of the Square (15 zł, pay at the ticket office for the church, departs at :10 and :40 past each hour, April-Oct Mon-Sat 9:30-11:10 & 13:10-17:40, closed Sun, usually closed Nov-March).

• Leaving the church, notice the neck clamps dangling from the exterior walls near the side door. If you were leaving Mass in centuries past, there would be locals chained here for public humiliation. You’d spit on them before turning right and stepping into one of the biggest market squares anywhere.

Kraków’s marvelous Square, one of Europe’s most gasp-worthy public spaces, bustles with street musicians, colorful flower stalls, cotton-candy vendors, loitering teenagers, the local breakdancing troupe, businesspeople commuting by foot, gawking tourists, soap-balloon-blowers, and the lusty coos of pigeons. The Square is where Kraków lives. It’s often filled with various special events, markets, and festivals. The biggest are the seasonal markets before Easter and Christmas, but you’re likely to stumble on something special going on just about any time of year (especially June through Aug).

The Square was established in the 13th century, when the city had to be rebuilt after being flattened by the Tatars. At the time, it was the biggest square in medieval Europe. It was illegal to sell anything on the street, so everything had to be sold here on the Main Market Square. It was divided into smaller markets, such as the butcher stalls, the ironworkers’ tents, and the still-standing Cloth Hall (described later).

Notice the modern fountain with the glass pyramid at this end of the Square. A major excavation of the surrounding area created a museum of Kraków’s medieval history that literally sprawls beneath the Square (for more on the recommended Rynek Underground Museum, see here).

The statue in the middle of the Square is a traditional meeting place for Krakovians. It depicts Romantic poet Adam Mickiewicz (1789-1855), who’s considered the “Polish Shakespeare.” His epic masterpiece, Pan Tadeusz, is still regarded as one of the greatest works in Polish literature. A wistful, nostalgic tale of Polish-Lithuanian nobility, Pan Tadeusz stirred patriotism in a Poland that had been dismantled by surrounding empires.

If you survey the Square from here, you’ll notice that the Old Town was spared the bombs of World War II. The Nazis considered Kraków a city with Germanic roots and wanted it saved. But they were quick to destroy any symbols of Polish culture or pride. The statue of Adam Mickiewicz, for example, was pulled down immediately after occupation.

Near the end of the Square, you’ll see the tiny, cubical, copper-domed Church of St. Adalbert, one of the oldest churches in Kraków (10th century). This Romanesque structure predates the Square. Like St. Mary’s (described earlier), it seems to be at an angle because it’s aligned east-west, as was the custom when it was built. (In other words, the churches aren’t crooked—the Square is. Any other “crooked” building you see around town predates the 13th-century grid created during the rebuilding of Kraków.)

Drinks are reasonably priced at cafés on the Square (most around 10-15 zł). Find a spot where you like the view and the chairs, then sit and sip. Order a coffee, Polish piwo (beer, such as Żywiec, Okocim, or Lech), or a shot of wódka (Żubrówka is a good brand; for more on Polish drinks, see here). For a higher vantage point, the Cloth Hall’s Café Szał terrace—overlooking the Square and St. Mary’s Church—offers one of the best views in town (open daily until 24:00, affordable drinks, some light meals, enter through Gallery of 19th-Century Polish Art entrance).

As the Square buzzes around you, imagine this place before 1989. There were no outdoor cafés, no touristy souvenir stands, and no salesmen hawking cotton candy or neon-lit whirligigs. The communist government shut down all but a handful of the businesses. They didn’t want people to congregate here—they should be at home, resting, because “a rested worker is a productive worker.” The buildings were covered with soot from the nearby Lenin Steelworks in Nowa Huta. The communists denied the pollution, and when the student “Green Brigades” staged a demonstration in this Square to raise awareness in the 1970s, they were immediately arrested. How things have changed.

• The huge, yellow building right in the middle of the Square is the...

In the Middle Ages, this was the place where cloth sellers had their market stalls. Kazimierz the Great turned the Cloth Hall into a permanent structure in the 14th century. In 1555, it burned down and was replaced by the current building. The crowned letter S (at the top of the gable above the entryway) stands for King Sigismund the Old, who commissioned this version of the hall. As Sigismund fancied all things Italian (including women—he married an Italian princess), this structure is in the Italianate Renaissance style. Sigismund kicked off a nationwide trend, and you’ll still see Renaissance-style buildings like this one all over the country, making the style as typically Polish as it is typically Italian. We’ll see more works by Sigismund’s imported Italian architects at Wawel Castle.

The Cloth Hall is still a functioning market—selling mostly souvenirs, including wood carvings, chess sets, jewelry (especially amber), painted boxes, and trinkets (summer Mon-Fri 9:00-18:00, Sat-Sun 9:00-15:00, sometimes later; winter Mon-Fri 9:00-16:00, Sat-Sun 9:00-15:00). Cloth Hall prices are slightly inflated, but still cheap by American standards. You’re paying a little extra for the convenience and the atmosphere, but you’ll see locals buying gifts here, too.

Pay WCs are at each end of the Cloth Hall. The upstairs of the Cloth Hall is home to the excellent Gallery of 19th-Century Polish Art (enter behind the statue of Adam; for a self-guided tour, see here).

• Browse through the Cloth Hall passageway. As you emerge into the sleepier half of the Square, the big tower on your left is the...

This is all that remains of a town hall building from the 14th century—when Kraków was the powerful capital of Poland. After the 18th-century Partitions of Poland, Kraków’s prominence took a nosedive. By the 19th century, Kraków was Nowheresville. As the town’s importance crumbled, so did its town hall. It was cheaper to tear down the building than to repair it, and all that was left standing was this nearly 200-foot-tall tower. In summer, you can climb the tower, stopping along the way to poke around an exhibit on Kraków history, but the views from up top are disappointing. However, you can step into the entryway for a free look at a model of an earlier version of the building, with a fanciful, Prague-style, multispired tower.

Cost and Hours: 9 zł, free on Mon, open April-Oct daily 10:30-18:00, closed Nov-March.

Nearby: The gigantic head at the base of the Town Hall Tower is a sculpture by contemporary artist Igor Mitoraj, who studied here in Kraków. Typical of Mitoraj’s works, the head is an empty shell that appears to be wrapped in cloth. While some locals enjoy having a work by their fellow Krakovian in such a prominent place, others disapprove of its sharp contrast with the Square’s genteel Old World ambience. Tourists enjoy playing peek-a-boo with the head’s eyes—a fun photo op.

• When you’re finished on the Square, we’ll head toward Wawel Hill. The official Royal Way makes a beeline for the castle, but we’ll take a scenic detour to see some less touristy back streets, visit Kraków’s historic university and one of its best churches, and go for a quick walk through the Planty park.

Exit the square at the corner nearest the Town Hall Tower, down ulica Św. Anny. After two short blocks, turn left onto Jagiellońska street. Enter the courtyard of the big, red-brick building on your right.

Kraków had the second university in Central Europe (founded in 1364, after Prague’s). Over the centuries, Jagiellonian U. has boasted such illustrious grads as Copernicus and St. John Paul II. And today, the city’s character is still defined largely by its huge student population (numbering around 150,000). Many of the university buildings fill the area to the west of the Old Town, so you’ll see more students (and fewer tourist traps) in this part of town than elsewhere.

This building—called the Collegium Maius—is the historic heart of Kraków’s university culture. It dates from the 15th century. In the Middle Ages, professors were completely devoted to their scholarly pursuits. They were unmarried and lived, ate, and slept here in an almost monastic environment. They taught downstairs and lived upstairs. In many ways, this building feels more like a monastery than a university. While this courtyard is the most interesting part, you can also tour the interior (for details, see here).

The university also comes with some chilling history. On November 6, 1939, the occupying Nazis called all professors together for a meeting. With 183 gathered unknowingly in a hall, they were suddenly loaded into trucks and sent to their deaths in concentration camps. Hitler knew: If you want to decapitate a culture, you kill its intelligentsia.

Before you leave, if you’re a fan of rich, thick hot chocolate, enjoy a cup at Kawiarnia U Pęcherza (down the stairs near the entrance)—widely regarded as the best in town.

Head down the sgraffito-lined passage on the side of the courtyard (it’s the first door on your left as you entered the courtyard—just past the little security office). You’ll emerge into the Professors’ Garden, a tranquil space filled with red brick, ivy, stony statues, and inviting benches (open daily 9:00-18:30 or until dusk).

• Exit the garden and turn right on Jagiellońska. Spot any students? You’ll follow this for two more blocks, passing the much larger and newer, but still red-brick, Collegium Novum building—the modern administrative headquarters of Jag U., built in the late 19th century to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the building we just left.

Jagiellońska dead-ends at a dynamic statue on a pillar. Turn left into the inviting Planty—the ring park we saw at the start of this walk. You’ll stroll about five minutes through the Planty, with the Old Town buildings on your left and the ring road through the park on your right. When you reach a street with tram tracks, cross it and turn left. Pause in the park just before the church, and take note of the light-yellow building on the left (across the street), with a picture of St. John Paul II smiling down from above the stone doorway.

This building was St. John Paul II’s residence when he was the archbishop of Kraków. And even after he became Pope, it remained his home-away-from-Rome for visits to his hometown. After a long day of saying formal Mass during his visits to Kraków, he’d wind up here. Weary as he was, before going to bed he’d stand in the window above the entrance for hours, chatting casually with the people assembled below—about religion, but also about sports, current events, and whatever was on their minds.

In 2005, when the Pope’s health deteriorated, this street filled with his supporters, even though he was in Rome. For days, somber locals focused their vigil on this same window, their eyes fixed on a black crucifix that had been placed here. At 21:37 on the night of April 2, 2005, the Pope passed away in Rome. Ten thousand Krakovians were on this street, under this window, listening to a Mass broadcast on loudspeakers from the church. When the priest announced the Pope’s death, every single person simultaneously fell to their knees in silence. For the next several days, thousands of the faithful continued to stand on this street, staring intently at the window where they last saw the man they considered to be the greatest Pole.

• Now go through the back door of one of Kraków’s finest churches...

This beautiful Gothic church, which was St. John Paul II’s home church while he was archbishop of Kraków, features some of Poland’s best Art Nouveau in situ (in the setting for which it was intended). After an 1850 fire, it was redecorated by the two leading members of the Młoda Polska (Young Poland) movement: Stanisław Wyspiański and Józef Mehoffer. The glorious decorations inside this church are the result of their great rivalry run amok.

Cost and Hours: Free, daily 6:00-19:45—but frequent services, so be discreet.

Self-Guided Tour: Step through the door and let your eyes adjust to the low light. Take a few steps up the nave, pausing at the third pew on the left. Notice the silver plate labeled “Jan Paweł II”—marking JPII’s favorite place to pray when he lived in the Archbishop’s Palace across the street.

Self-Guided Tour: Step through the door and let your eyes adjust to the low light. Take a few steps up the nave, pausing at the third pew on the left. Notice the silver plate labeled “Jan Paweł II”—marking JPII’s favorite place to pray when he lived in the Archbishop’s Palace across the street.

Now walk another 20 feet down the nave, and notice the painting on the right, with an orange-and-blue background. This depicts St. Maksymilian Kolbe, the Catholic priest who sacrificed his own life to save a fellow inmate at Auschwitz in 1941 (notice the 16670—his concentration camp number—etched into the background; read his story on here). Kolbe is particularly beloved here, as he actually served at this church.

Now turn around and look up above the door you entered. There, in all its glory, is the stained-glass window titled God the Father Let It Be, created by the great Art Nouveau artist Stanisław Wyspiański—and regarded by some as his finest masterpiece. (For more on Wyspiański, see here.) The colors beneath the Creator change from yellows and oranges (fire) to soothing blues (water), depending on the light. Wyspiański was supposedly inspired by Michelangelo’s vision of God in the Sistine Chapel, though he used a street beggar to model God’s specific features. Wyspiański also painted the delightful floral stained-glass windows that line the nave, high up—fitting for a church dedicated to a saint so famous for his spiritual connection to nature.

Now turn back around to face the main altar, and head into the chapel on the left (marked Całun Turyński). This important chapel houses a replica of the Shroud of Turin—which, since it touched the original shroud, is also considered a holy relic. At the main altar in this chapel, notice the plaques honoring Michała Tomaszek and Zbigniew Strzałkowski. These two Polish priests traveled to Peru as missionaries. There, they (along with an Italian priest) were murdered by communist guerrillas calling themselves the Shining Path. Today they are considered martyrs. Nearby, look for photos of Pope Francis (who, like this church and these missionaries, is Franciscan) praying at this altar.

Before leaving this chapel, look high on the walls at the glorious Stations of the Cross. These are painted by Józef Mehoffer—a friend and rival of Wyspiański—as a response to Wyspiański’s work.

Now head back into the nave, turn left, and walk toward the main altar. (If a service is going on, you may not be able to get very far—just look from here.) On the walls, notice Wyspiański’s gorgeous Art Nouveau floral patterns.

Up in the apse, take a moment to appreciate the Wyspiański-designed stained-glass windows flanking the high altar. On the right is St. Francis, the church’s namesake. On the left is the Blessed Salomea—a medieval Polish woman who became queen of Hungary, but later returned to Poland and entered a convent after her husband’s death. Notice she’s dropping a crown—repudiating the earthly world and giving herself over to the simple, stop-and-smell-God’s-roses lifestyle of St. Francis. Salomea (who’s buried in a side chapel) founded this church. Notice also the Mucha-like paintings by Wyspiański on the pilasters between the windows...yet one more sumptuous Art Nouveau detail in this church that’s so rich with them.

• Head back outside. If no services are going on, you can slip out the side door, to the left of the altar. Otherwise, head back out the way you came and hook right. Either way, you’re heading to the right along Franciszkańska street. After passing a few monuments and a tram stop, turn right down busy...

Now you’re back on the Royal Way proper. At the corner of Grodzka street stands the modern, copper-colored Wyspiański Pavilion. Step inside (daily 9:00-17:00), past the little TI, to see three new stained-glass windows based on designs Wyspiański once submitted for a contest to redecorate Wawel Cathedral. Although these designs were rejected back then, they were finally realized on the hundredth anniversary of his death (in 2007). Visible from inside the building during the day, and gloriously illuminated to be seen outside the building at night, they represent three Polish historical figures: the gaunt St. Stanisław (Poland’s first saint), the skeletal Kazimierz the Great (in the middle), and the swooning King Henry the Pious.

If you’re not churched out, you can dip into the Dominican Church—just a block away, to your left (described on here).

Now continue down Grodzka street. This lively thoroughfare, connecting the Square with Wawel, is teeming with shops—and some of Kraków’s best restaurants (see “Eating in Kraków,” later). Survey your options now, and choose (and maybe reserve) your favorite for dinner tonight. This street is also characterized by its fine arcades over the sidewalks. While this might seem like a charming Renaissance feature, the arcades were actually added by the Nazis after they invaded in 1939; they wanted to convert Kraków into a city befitting its status as the capital of their Polish puppet state.

This is also a good street to find some of Kraków’s milk bars (two are listed on here). The most traditional one is about two blocks down, on the right (at #45), with a simple Bar Mleczny sign. These government-subsidized cafeterias are the locals’ choice for a quick, cheap, filling, lowbrow lunch. Prices are deliriously cheap (soup costs about a dollar), and the food isn’t bad. For more on milk bars, see here.

• One more block ahead, the small square on your right is...

This square offers a great visual example of Kraków’s deeply religious character. In the Middle Ages, Kraków was known as “Small Rome” for its many churches. Today, there are 142 churches and monasteries within the city limits (32 in the Old Town alone)—more per square mile than anywhere outside of Rome. You can see several of them from this spot: The nearest, with the picturesque white facade and row of saints out front, is the Church of Saints Peter and Paul (Poland’s first Baroque church, and a popular tourist concert venue). The statues lining this church’s facade are the 11 apostles (minus Judas), plus Mary Magdalene, the square’s namesake. The next church to the right, with the twin towers, is the Romanesque St. Andrew’s (now with a Baroque interior). Dating from the rough-and-tumble 11th century, it was designed to double as a place of last refuge—notice the arrow slits around the impassable lower floor. According to legend, a spring inside this church provided water to citizens who holed up here during the Tatar invasions. The church was spared, but that didn’t save the rest of Kraków from being overrun by marauding armies. Imagine this stone fortress of God being the only building standing amid a smoldering and flattened Kraków after the 13th-century destruction.

If you look farther down the street, you can see three more churches. And even the square next to you used to be a church, too—it burned in 1855, and only its footprint survives.

• Go through the square and turn left down...

With so many churches around here, the clergy had to live somewhere. Many lived on this well-preserved street—supposedly the oldest street in Kraków. As you walk, look for the cardinal hats over three different doorways. The Hotel Copernicus, on the left at #16, is named for a famous guest who stayed here five centuries ago. Directly across the street at #17, the Bishop Erazm Ciołek Palace hosts a good exhibit of medieval art and Orthodox icons. Next door, the yellow house at #19 is where Karol Wojtyła lived for 10 years after World War II—long before he became St. John Paul II. Today this building houses the Archdiocesan Museum, which is the top spot in the Old Town to learn about Kraków’s favorite son. Both of these sights are described later, under “Sights in Kraków.”

• This marks the end of Kanonicza street—and the end of our self-guided walk. But there’s still much more to see. Across the busy street, a ramp leads up to the most important piece of ground in all of Poland: Wawel (described next).

WAWEL HILL: THE HEART AND SOUL OF POLAND

John Paul II Wawel Cathedral Museum

▲Royal State Rooms (Komnaty Królewskie)

Royal Private Apartments (Prywatne Apartamenty Królewskie)

Crown Treasury and Armory (Skarbiec i Zbrojownia)

▲▲Leonardo da Vinci’s Lady with an Ermine

▲▲Gallery of 19th-Century Polish Art (Galeria Sztuki Polskiej XIX Wieku)

Szołayski House (Kamienica Szołayskich)

Bishop Erazm Ciołek Palace (Pałac Biskupa Erazma Ciołka)

▲Czartoryski Museum (Muzeum Czartoryskich)

▲▲Rynek Underground Museum (Podziemia Rynku)

▲Jagiellonian University Museum: Collegium Maius

Dominican Church, a.k.a. Holy Trinity Church (Bazylika Trójcy Świętej)

Archdiocesan Museum (Muzeum Archidiecezjalne)

Wawel (VAH-vehl), a symbol of Polish royalty and independence, is sacred territory to every Polish person. A castle has stood here since the beginning of Poland’s recorded history. Today, Wawel—awash in tourists—is the most visited sight in the country. Crowds and an overly complex admissions system for the hill’s many historic sights can be exasperating. Thankfully, a stroll through the cathedral and around the castle grounds requires no tickets, and—with the help of the following commentary—is enough. I’ve described these sights in the order of a handy self-guided walk. The many museums on Wawel (all described in this section) are mildly interesting, but can be skipped (grounds open daily from 6:00 until dusk, inner courtyard closes 30 minutes earlier). In May and June, it’s mobbed with students, as it’s a required field trip for Polish school kids.

Wawel Sights: The sights you’ll enter at Wawel are divided into two institutions: church and castle, each with separate tickets. Tickets for the castle sights are sold at two points (at the long line at the top of the ramp, or with no line at the top of the hill, across the central square). The most important church sight—the cathedral—is mostly free, but to enter the paid sights inside (or the museum), get a ticket at the office across from the cathedral entrance.

• From Kanonicza street—where my self-guided walk ends—head up the long ramp to the castle entry.

Huffing up this ramp, it’s easy to imagine how this location—rising above the otherwise flat plains around Kraków—was both strategic and easy to defend. When Kraków was part of the Habsburg Empire in the 19th century, the Austrians turned this castle complex into a fortress, destroying much of its delicate beauty. When Poland regained its independence after World War I, the castle was returned to its former glory. The bricks you see on your left as you climb the ramp bear the names of Poles from around the world who donated to the cause.

The jaunty equestrian statue ahead is Tadeusz Kościuszko (1746-1817), a familiar name to many Americans. Kościuszko was a hero of the American Revolution and helped design West Point. When he returned to his native Poland, he fought bravely but unsuccessfully against the Russians (during the Partitions that would divide Poland’s territory among three neighboring powers). Kościuszko also gave his name to several American towns, a county in Indiana, a brand of mustard from Illinois, and the tallest mountain in Australia.

• Hiking through the Heraldic Gate next to Kościuszko, you pass the ticket office (if you’ll be going into the museums, use the other ticket office, with shorter lines, on the top of the hill—see “Tickets and Reservations,” later). As you crest the hill and pass through the stone gate, on your left is...

Poland’s national church is its Westminster Abbey. While the history buried here is pretty murky to most Americans, to Poles, this church is the national mausoleum. It holds the tombs of nearly all of Poland’s most important rulers and greatest historical figures.

Cost and Hours: It’s usually free to walk around the main part of the church. You must buy a 12-zł ticket to climb up the tallest tower; visit the crypt, the royal tombs, and some of the lesser chapels; and tour the John Paul II Wawel Cathedral Museum. Buy this ticket at the house across from the cathedral entry—marked KASA—where you can also rent an audioguide (7 zł). The cathedral is open April-Sept Mon-Sat 9:00-17:00, Sun 12:30-17:00, Oct-March daily until 16:00 (tel. 12-429-9516, www.katedra-wawelska.pl). Note that the cathedral’s museum (described later) is closed on Sunday.

Before entering, go around to the far side of the cathedral to take in its profile. This uniquely eclectic church is the product of centuries of haphazard additions...yet somehow, it works. It began as a simple, stripped-down Romanesque church in the 12th century. (The white base of the nearest tower is original. Anything at Wawel that’s made of white limestone like this was probably part of the earliest Romanesque structures.) Kazimierz the Great and his predecessors gradually surrounded the cathedral with some 20 chapels, which were further modified over the centuries, making this beautiful church a happy hodgepodge of styles. To give you a sense of the historical sweep, scan the chapels from left to right: 14th-century Gothic, 12th-century Romanesque (the base of the tower), 17th-century Baroque (the inside is Baroque, though the exterior is a copy of its Renaissance neighbor), 16th-century Renaissance, and 18th- and 19th-century Neoclassical. (This variety in styles is even more evident in the chapels’ interiors, which we’ll see soon.)

Pay attention to the two particularly interesting domed chapels to the right of the tall tower. The gold one is the Sigismund Chapel, housing memorials to the Jagiellonian kings—including Sigismund the Old, who was responsible for Kraków’s Renaissance renovation in the 16th century. The Jagiellonian Dynasty was a high point in Polish history. During that golden 16th century, Poland was triple the size it is today, stretching all the way to the Ottoman Empire and the Black Sea. Poles consider the Sigismund Chapel, made with 80 pounds of gold, to be the finest Renaissance chapel north of the Alps. The copper-domed chapel next to it, home to the Swedish Vasa dynasty, resembles its neighbor (but it’s a copy built 150 years later, and without all that gold).

Go back around and face the church’s front entry for more architectonic extravagance. The tallest tower, called the Sigismund Tower, has a clock with only an hour hand. Climbing a few steps into the entry, you see Gothic chapels (with pointy windows) flanking the door, a Renaissance ceiling, lavish Baroque decoration over the door, and some big bones (a simple whale rib). In the Middle Ages, these were thought to have been the bones of the mythic Wawel dragon, and put here as an oddity to be viewed by the public. (Back then, there were no museums, so notable items like these were used to lure people to the church.) It’s said that as long as the bones hang here, the cathedral will stand. The door is the original from the 14th century, with fine wrought-iron work. The K with the crown stands for Kazimierz the Great. The black marble frame is made of Kraków stone from nearby quarries.

The cathedral interior is slathered in Baroque memorials and tombs, decorated with tapestries, and soaked in Polish history. The ensemble was designed to help keep Polish identity strong through the ages. It has...and it still does.

Visiting the Cathedral: After you step inside, you’ll follow the one-way, clockwise route that leads you through the choir, then around the back of the apse, then back to the entry.

At the entry, look straight ahead to see the silver tomb under a canopy, inspired by the one in St. Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican. It contains the remains of the first Polish saint, Stanisław (from the 11th century). In front of the canopy, look for a metallic reliquary that’s shaped like a book with its pages being ruffled by the wind (labeled, in Latin, Sanctus Johannes Paulus II). The glass capsule in the reliquary holds a drop of St. John Paul II’s blood. It takes this shape because of what believers consider a highly significant moment during his memorial service: Before a crowd of thousands on St. Peter’s Square in Rome, a book was placed on John Paul II’s simple wooden coffin. As the service processed, its pages were ruffled back and forth by the wind, until they were finally slammed shut...as if the Holy Spirit were “closing the book” on his life.

Go behind this canopy into the ornately carved choir area. For 200 years, the colorful chair to the right of the high altar has been the seat of Kraków’s archbishops, including Karol Wojtyła, who served here for 14 years before becoming pope. It’s here that Polish royal coronations took place.

Now you’ll continue into the left aisle. From here, if you have a ticket, you can enter two of the optional attractions: Seventy claustrophobic wooden stairs lead up to the 11-ton Sigismund Bell and pleasant views of the steeples and spires of Kraków. Then, to the left (closer to where you entered), descend into the little crypt (with a rare purely Romanesque interior), which houses the remains of Adam Mickiewicz, the Romantic poet whose statue dominates the Main Market Square, and another beloved Romantic poet and playwright, Juliusz Słowacki. You’ll also find a white marble monument to Fryderyk Chopin (who’s buried in Paris), put here on the 200th anniversary of his birth in 2010.

Now continue around the apse (behind the main altar). After curving around to the right, look for the red-marble tomb (on the right) of The Great One—Kazimierz, of course. Look for Kazimierz Wielki—at his feet you can see a little beaver. This is an allusion to a famous saying about Kazimierz, the nation-builder: He found a Poland made of wood, and left one made of brick and stone.

You may notice that there’s one VIP (Very Important Pole) who’s missing...Karol Wojtyła, a.k.a. John Paul II. Even so, a few more steps toward the entrance, on the left, is the Chapel of St. John Paul II. The late pontiff left no specific requests for his body, and the Vatican controversially (to Poles, at least) chose to entomb him in Vatican City, instead of sending him back home to Wawel. While Karol Wojtyła’s remains are in St. Peter’s Basilica, this chapel was recently converted to honor him—with a plaque in the floor and an altar with his picture. Someday, Poles hope, he may be moved here (but, the Vatican says, don’t hold your breath).

Directly opposite the chapel, you’ll see the rusty funeral regalia (orb and scepter) of St. Jadwiga; ten steps farther is her white sarcophagus (with a dog at her feet). This 14th-century “king” of Poland advanced the fortunes of her realm by partnering with the king of Lithuania. The resulting Jagiellonian dynasty fought off the Teutonic Knights, helped Christianize Lithuania, and oversaw a high-water mark in Polish history. (Despite the queen’s many contributions, the sexism of the age meant that she was considered a “king” rather than a “queen.”) All the flowers here demonstrate how popular she remains among Poles today; she was sainted by Pope John Paul II in 1997.

Across from Jadwiga, peek into the gorgeous 16th-century Sigismund Chapel, with its silver altar (this is the gold-roofed chapel you just saw from outside). Locals consider this the “Pearl of the Polish Renaissance” and the finest Renaissance building outside Italy.

Just beyond is a door leading back outside. If you don’t have a ticket, your tour is finished—head out here. But those with a ticket can keep circling around.

Next, look into the Vasa Chapel: Remember that its exterior matches the restrained, Renaissance style of the Sigismund Chapel, but the interior is clearly Baroque, slathered with gold and silver—quite a contrast.

To the left of the main door, take a look at the Gothic Holy Cross Chapel, with its seemingly Orthodox-style 14th-century frescoes.

In the back corner of the church—on the other side of the main door—is the entrance to the royal tombs. (You’ll exit outside the church, so be sure you’re done in here first.) Once downstairs, the first big room, an original Romanesque space called St. Leonard’s Crypt, houses Poland’s greatest war heroes: Kościuszko (of American Revolution fame), Jan III Sobieski (who successfully defended Vienna from the Ottomans; he’s in the simple black coffin with the gold inscription J III S), Sikorski, Poniatowski, and so on. Poles consider this room highly significant as the place where St. John Paul II celebrated his first Mass after becoming a priest (in November of 1946). Then you’ll wander through several rooms of second-tier Polish kings, queens, and their kids. Head down more stairs to find the plaque honoring the Polish victims of the Katyń massacre in the USSR during World War II. Stepping into the next room, you’ll see the cathedral’s newest tomb: President Lech Kaczyński and his wife Helena, who were among the 96 Polish politicians killed in a tragic 2010 plane crash—which was delivering those diplomats to a ceremony memorializing the Katyń massacre. Up a few stairs is the final grave, belonging to Marshal Józef Piłsudski, the WWI hero who later seized power and was the de facto ruler of Poland from 1926 to 1935. His tomb was moved here so the rowdy soldiers who came to pay their respects wouldn’t disturb the others.

• Nearby (and covered by the same ticket as the tower and crypt) is the cathedral’s museum.

This small museum, up the little staircase across from the cathedral entry, was recently spiffed up and re-dedicated to Kraków’s favorite archbishop. It fills four rooms with artifacts relating to both the cathedral and St. John Paul II.

Downstairs is the Royal Room, with vestments, swords, regalia, coronation robes, and items that were once buried with the kings, as well as early treasury items (from the 11th through 16th centuries). Upstairs is the “Papal Room” with items from St. John Paul II’s life: his armchair, vestments, caps, shoes, and miter (pointy pope hat), plus souvenirs from his travels. (If you’re into papal memorabilia, the collection at the nearby Archdiocesan Museum—described later—is better.) The adjoining room holds a later treasury collection (17th through 20th centuries).

Cost and Hours: Admission to this museum is included with your ticket to the cathedral’s special options (Sigismund Bell tower, plus crypt and royal tombs); open April-Sept Mon-Sat 9:00-17:00, Oct-March until 16:00, closed Sun year-round; tel. 12-429-3321.

• When you’re finished with the cathedral sights, stroll around the...

In the rest of the castle, you’ll uncover more fragments of Kraków’s history and have the opportunity to visit several museums. I consider the museums skippable, but if you want to visit them, buy tickets before you enter the inner courtyard. Read the descriptions on here to decide which museums appeal to you.

Self-Guided Tour: This guided stroll, which doesn’t enter any of the admission-charging attractions, is plenty for most visitors.

Self-Guided Tour: This guided stroll, which doesn’t enter any of the admission-charging attractions, is plenty for most visitors.

• For a historical orientation, stand with the cathedral to your back, and survey the empty field between here and the castle walls.

Field of History: This hilltop has seen lots of changes over the years. Kazimierz the Great turned a small fortress into a mighty Gothic castle in the 14th century. But that original fortress burned to the ground in 1499, and ever since, Wawel has been in flux. For example, in the grassy field, notice the foundations of two Gothic churches that were destroyed when the Austrians took over Wawel in the 19th century and needed a parade ground for their troops. (They built the red-brick hospital building beyond the field, now used by the Wawel administration.)

• Facing the cathedral, look right to find a grand green-and-pink entryway. Go through here and into the palace’s dramatically Renaissance-style...

Inner Courtyard: If this space seems to have echoes of Florence, that’s because it was designed and built by young Florentines after Kazimierz’s original castle burned down. Notice the three distinct levels: The ground floor housed the private apartments of the higher nobility (governors and castle administrators); the middle level held the private apartments of the king; and the top floor—much taller, to allow more light to fill its large spaces—were the public state rooms of the king. The ivy-covered wing to the right of where you entered is Fascist in style, built as the headquarters of the notorious Nazi governor of German-occupied Poland, Hans Frank. (He was tried and executed in Nürnberg after the war.) At the far end of the courtyard is a false wall, designed to create a pleasant Renaissance symmetry, and also to give the illusion that the castle is bigger than it is. Looking through the windows, notice that there’s nothing but air on the other side. When foreign dignitaries visited, these windows could be covered to complete the illusion. The entrances to most Wawel museums are around this courtyard, and some believe that you’ll find something even more special: chakra.

Adherents to the Hindu concept of chakra believe that a powerful energy field connects all living things. Some believe that, mirroring the seven chakra points on the body (from head to groin), there are seven points on the surface of the earth where this energy is most concentrated: Delhi, Delphi, Jerusalem, Mecca, Rome, Velehrad...and Wawel Hill—specifically over there in the corner (immediately to your left as you enter the courtyard—the stretches of wall flanking the door to the baggage-check room). Look for peaceful people (here or elsewhere on the castle grounds) with their eyes closed. One thing’s for sure: They’re not thinking of Kazimierz the Great. The smudge marks on the wall are from people pressing up against this corner, trying to absorb some good vibes from this chakra spot.