Warszawa

NEAR PALM TREE CIRCLE (NOWY ŚWIAT AND JERUSALEM AVENUE)

NEAR PALM TREE CIRCLE (NOWY ŚWIAT AND JERUSALEM AVENUE)

Warsaw (Warszawa, vah-SHAH-vah in Polish) is Poland’s capital and biggest city. It’s huge, famous, and important...but not particularly romantic. If you’re looking for Old World quaintness, head for Kraków. If you’re tickled by spires and domes, get to Prague. But if you want to experience a truly 21st-century city, Warsaw’s your place.

Not that long ago, the city was dreary and uninviting, but things have changed here—fast. Today, Warsaw’s residents—Varsovians—are chic and sophisticated. Young professionals dress and dine as well as Parisians or Milanese do, and they have mastered the art of navigating an urban jungle in heels or a man bun. And from an infrastructure perspective, you can almost feel Warsaw peeling back the layers of communist grime as it replaces potholed highways with pedestrian-friendly parks. Today’s Warsaw has gleaming new office towers and street signs, cutting-edge shopping malls, swarms of international businesspeople, hipster culture as vivid as anything in Brooklyn, and a gourmet coffee shop or designer pastry store on every corner.

Stroll down revitalized boulevards that evoke the city’s glory days, pausing at an outdoor café to sip coffee and nibble at a pączek (the classic Polish jelly doughnut). Drop by a leafy park for an al fresco Chopin concert, packed with pensive Poles. Commune with the soul of Poland at the city’s many state-of-the-art museums focusing on Poland’s artists (at the National Museum), its favorite composer (at the Chopin Museum), its dramatic history (at the Warsaw Historical Museum and Warsaw Uprising Museum), its dedication to the sciences (at the Copernicus Science Center), and its Jewish story (at the Museum of the History of Polish Jews). You can also dig into one of Europe’s most affordable—and most interesting—foodie scenes, where a world of wildly creative chefs open new restaurants all the time. If you picture a dreary metropolis, think again. Warsaw is full of surprises.

One day is the absolute minimum to get a quick taste of Warsaw. The city can easily fill two or three days, and even then you’ll need to be selective. No matter how long you’re staying, get your bearings by taking a stroll through Polish history on the Royal Way, using my self-guided walk from Palm Tree Circle to the Old Town. Then visit other sights according to your interests and time: Jewish history, the Warsaw Uprising, Polish artists, royalty, hands-on science gizmos, hipster hangouts, or Chopin. To slow down and take a break from the city, relax in Łazienki Park. For dinner, buck the tourist trend by leaving the overpriced Old Town and riding a tram, taxi, or Uber to the hip Śródmieście district, which has the highest concentration of quality eateries.

Warsaw sprawls with 1.7 million residents. Everything is on a big scale—it seems to take forever to walk just a few “short” blocks. Get comfortable with public transportation (or taxis or Uber), and plan your sightseeing to avoid backtracking.

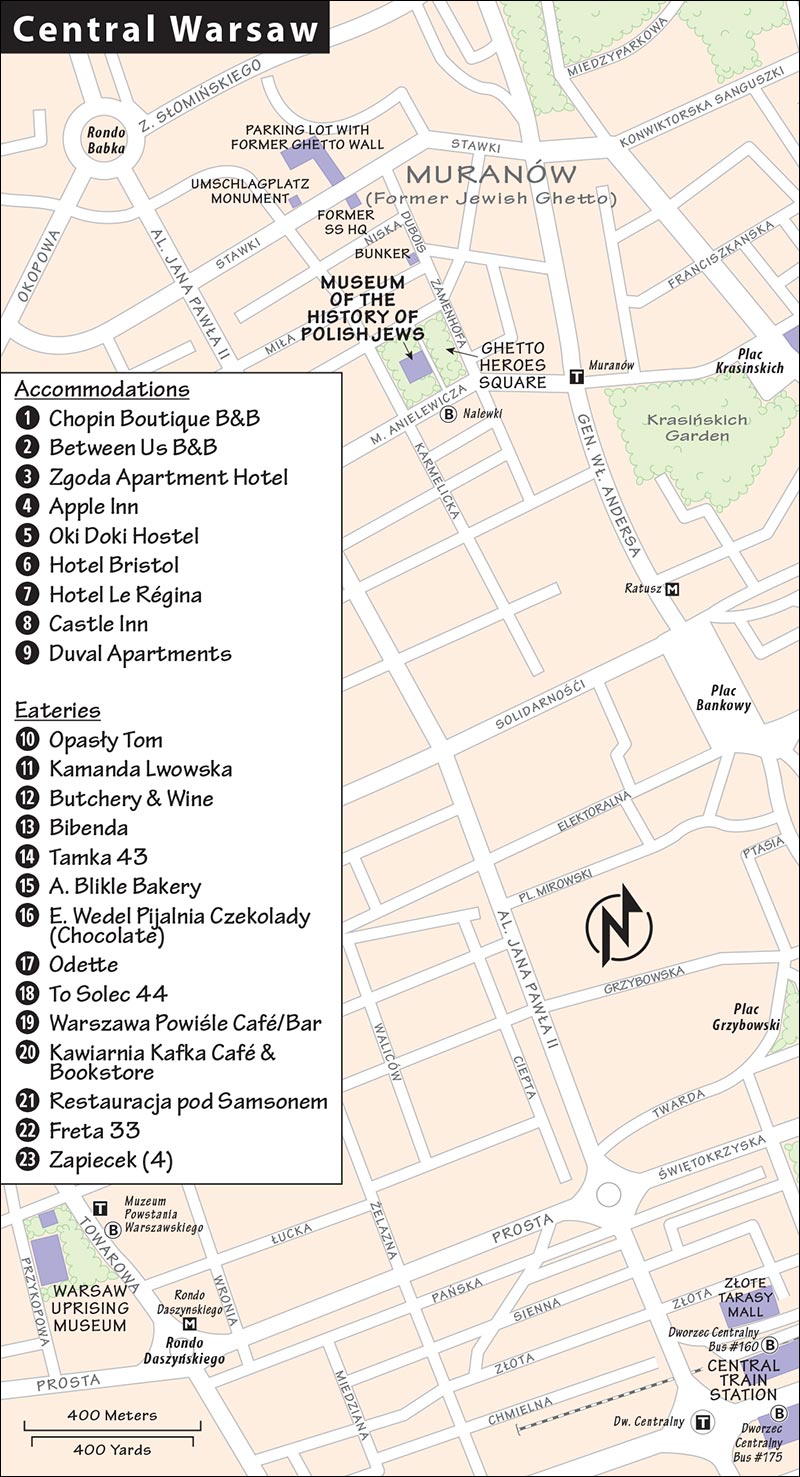

The tourist’s Warsaw blankets a mild hill on the west bank of the Vistula River (in Polish: Wisła, VEES-wah). To break things into manageable chunks, I think of the city as three major zones (from north to south):

The Old Town and Royal Way, at Warsaw’s northern edge, is the most touristy area. Here you’ll find the Old Town (Stare Miasto, STAH-reh mee-AH-stoh), the adjacent and nearly-as-old New Town (Nowe Miasto, NOH-vay mee-AH-stoh), the Royal Castle on Castle Square (Plac Zamkowy, plahts zahm-KOH-vee), and the historical artery called the Royal Way (Szłak Królewski, shwock kroh-LEHV-skee). This bustling strip has fine boulevards, genteel cafés, expansive squares and parks, and lots of stately landmarks both historic and faux-historic (much of this area was rebuilt after World War II).

“Palm Tree Circle” is my nickname for the center of the city, near the traffic circle with a fake palm tree—where busy Jerusalem Avenue (aleja Jerozolimskie, ah-LAY-uh yeh-ro-zoh-LIM-skyeh) crosses the shopping street called Nowy Świat (NOH-vee SHVEE-aht). Nearby are some good accommodations, trendy upscale eateries, pedestrianized shopping streets and glitzy malls, the National Museum (Polish art), the Palace of Culture and Science (communist-era landmark skyscraper), and the central train station (Warszawa Centralna).

The Śródmieście (SHROD-myesh-cheh, “Downtown”) district, to the south, is a mostly-residential zone with the city’s best restaurant and nightlife scene and some good accommodations. The only real sight here is lush Łazienki Park, with its summertime al fresco Chopin concerts.

In sprawling Warsaw, many more sights—including some major ones—lie outside these three areas, but all are within a long walk or a short ride on public transit. These include the Museum of the History of Polish Jews and Warsaw Uprising Museum (to the west) and the Copernicus Science Center (to the east, along the river).

Warsaw’s helpful, youthful TI has three branches: on the Old Town Market Square (daily May-Sept 9:00-20:00, Oct-April until 18:00), at the Palace of Culture and Science (enter on the side facing the train station, on Emilii Plater; daily May-Sept 8:00-19:00, Oct-April until 18:00), and at Chopin Airport (daily 9:00-19:00). The general information number for all TIs is 22-19115. All branches offer advice on live music and have piles of free, useful brochures (“city breaks,” Jewish heritage, Chopin, mermaids, St. John Paul II, and so on). Everything is also available online (www.warsawtour.pl).

Busy sightseers might consider the Warsaw Pass, which covers public transportation, admission to several major sights, and free passage on the best hop-on, hop-off bus tour (119 zł/24 hours, 159 zł/48 hours, 189 zł/72 hours, sold at the TI). If your museum-going plans are ambitious, do the math.

Most trains arrive at the central train station (Warszawa Centralna, vah-SHAH-vah tsehn-TRAHL-nah), a renovated communist-era monstrosity. (Don’t get off at Warszawa Zachodnia, which is far from the tourist area.) Arriving at Warszawa Centralna, it can be tricky to get your bearings: Three parallel concourses run across the tracks, accessed by three different sets of escalators from each platform, creating a subterranean maze (with well-signed lockers, ticket windows, and lots of shops and eateries). Be patient: To get your bearings, ride up on your platform’s middle escalator, then look for signs to the vast, open main hall (follow signs for main hall/hala główna). Here you’ll find a row of ticket windows, a railroad service center, a supermarket, eateries, waiting areas (upstairs), and (from outside, near the taxi stand) views of the adjacent Palace of Culture and Science and Złota 44 skyscrapers. If you have a little time to kill, walk across the street to the super-modern Złote Tarasy Shopping Mall (described on here).

Getting into Town: To reach the tourist zone and most of my recommended hotels, a taxi/Uber is the easiest choice, while the bus is more economical (but more challenging to find).

Taxis wait outside the main hall. Many are dishonest—look for one with a company logo and telephone number, and ask for an estimate up front (the fare should be no more than about 20-30 zł for most of my recommended hotels). You can also request an Uber.

From the station, bus #175 or #128 takes you to the Royal Way and Old Town in about 10 minutes (see “Getting Around Warsaw,” later). You can catch either bus in front of the skyscraper with the Hotel Marriott (across busy Jerusalem Avenue from the station). From the corridors under the main hall, carefully track Aleje Jerozolimskie signs to find the pedestrian underpass. Several different exits are marked this way, but look for signs to Śródmieście Station, and then—near the end of that corridor—Hotel Marriott. Both buses terminate just off Piłsudski Square, a five-minute walk from the Old Town. Bus #160 also goes to the Old Town (though not via the Royal Way), but it departs from the opposite side of the station: To find its stop from the main hall, go out the side door toward ul. Emilii Plater. Before boarding any bus, buy a ticket from the machine near the stop—or get one in the underground zone, at any kiosk marked RUCH.

Buying Train Tickets: Lining one wall of the main arrival hall (hala główna) are 16 ticket windows. A more user-friendly passenger service center is in the opposite corner (daily 9:10-20:30). While it can be slower to buy tickets or make reservations here (take a number as you enter), staff members are more likely to speak English and have patience for clueless tourists. Additional ticket windows are in the maze of corridors under the station. Allow yourself plenty of time to wait in line to buy tickets. Remember: Even if you have a rail pass, a reservation is still required on many express trains (including EIC trains to Kraków or Gdańsk). If you’re not sure, ask. To get to your train, first find your way to the right platform (peron, as noted on schedules), then keep an eye on both tracks (tor) for your train. Train info: Tel. 19436 (22-19436 from outside Warsaw), www.rozklad-pkp.pl.

Warsaw’s Fryderyk Chopin International Airport (Port Lotniczy im. Fryderyk Chopina, airport code: WAW) is about six miles southwest of the center. The airport has just one terminal (Terminal A), which is divided into five check-in areas split between two zones: the southern hall (areas A and B) and the northern hall (areas C, D, and E). The airport is small and manageable; outside the arrivals area, you’ll find a TI, ATMs, car-rental offices, and exchange desks (kantor). Airport info: tel. 22-650-4220, www.lotnisko-chopina.pl.

You can take the train or bus into town (similar prices, around 5 zł). The train is faster, but the bus makes more stops in the city center and may get you closer to your hotel. From the arrivals area, just follow signs to either option, and buy your ticket at the red machine before you board.

The train departs about every 15 minutes and takes 20-30 minutes. The route is operated by two different companies (SKM and KM)—take the one that’s departing first. Be ready for your stop: Half the trains make fewer stops and take you to Centralna station; the others make a few more stops and use the Warszawa Śródmieście station—which feeds into the same underground passages as Centralna (these trains also continue one more stop to the Warszawa Powiśle station, which is a bit closer to Nowy Świat and can be more convenient to some hotels). Whether arriving at Centralna station or Warszawa Śródmieście, see the “By Train” arrival instructions, earlier.

Bus #175 departs every 15-20 minutes and runs into the city center (Centralna station, the Royal Way, and Piłsudski Square near the Old Town, 30-45 minutes depending on traffic).

For a taxi, head to the official taxi stand (avoid random hucksters offering you a ride out front). The trip to most hotels shouldn’t cost more than 40-50 zł. It takes about 30 minutes, but potentially much longer during rush hour. You can also request an Uber, which is typically less expensive (except at very busy times).

Modlin Airport (airport code: WMI), about 21 miles northwest of the city center, primarily serves budget airlines (especially Ryanair). The most direct option for getting to downtown Warsaw is by shuttle bus—ModlinBus and OKbus both connect the airport to downtown (33 zł, 2/hour, 1-hour trip, cheaper if you book ahead online—www.modlinbus.com or www.okbus.pl). An alternative is the well-coordinated bus-plus-train connection: Take a shuttle bus to Modlin’s main train station, then hop on a train to Warszawa Centralna station (17 zł, hourly, 1-1.5 hours total, www.mazowieckie.com.pl). If you want to ride a taxi all the way into Warsaw, the maximum legitimate fare is 200 zł (or 250 zł at night). Airport info: www.modlinairport.pl.

By Public Transit: In this big city, it’s essential to get a handle on public transportation. You’ll rely mostly on buses and trams, but the Metro can be useful for reaching a few sights. Everything is covered by the same ticket. A single ticket costs 4.40 zł (called bilet jednorazowy, good for one trip up to 75 minutes). But most trips should last no longer than 20 minutes, so you can save a zloty by buying a 3.40-zł “20-minute city travelcard” (bilet 20-minutowy). A 24-hour travelcard (bilet dobowy)—which pays for itself if you take at least five trips—costs 15 zł. Ticket machines, which are at most major stops and on board some trams, are easy to use. Or you can buy tickets at any kiosk with a RUCH sign. Be sure to validate your ticket as you board by inserting it in the little yellow box. Transit info: www.ztm.waw.pl.

Most of the city’s major attractions line up on a single axis, the Royal Way, which is served by several different buses (but no trams). Bus #175—particularly useful on arrival—links Chopin Airport, the central train station, the Royal Way, and Old Town (it terminates at Piłsudski Square, about a five-minute walk from Castle Square). Once you’re in town, the designed-for-tourists bus #180 conveniently connects virtually all the significant sights and neighborhoods: the former Jewish Ghetto and Museum of the History of Polish Jews, Castle Square/Old Town, the Royal Way, Łazienki Park, and Wilanów Palace (south of the center). This particularly user-friendly bus lists sights in English on the posted schedule inside (other buses don’t). Buses #175 and #180, as well as buses #116, #128, and #222, go along the most interesting stretch of the Royal Way (between Jerusalem Avenue and the Old Town area). Bus #178 conveniently connects Castle Square to the Warsaw Uprising Museum. Bus routes beginning with “E” (marked in red on schedules) are express, so they go long distances without stopping (these don’t run July-Aug).

Note that on Saturdays and Sundays in summer (June-Sept), the Nowy Świat section of the Royal Way is closed to traffic, so the above routes detour along a parallel street.

Trams can be particularly useful for reaching the trendy Śródmieście district in the south. Several trams (including #4, #15, #18, and #35) run along the north-south Marszałkowska corridor, with stops at plac Konstytucji (Constitution Square, the heart of the Śródmieście) and at plac Zbawiciela (with the highest concentration of eateries).

Warsaw’s two-line Metro system is handy for commuters, but less so for visitors. Still, it can be useful for some trips. Line 1 runs roughly parallel to the river and Royal Way, several blocks to the west; the most useful stops for tourists are Centrum (near the Palace of Culture and Science) and Świętokrzyska (where it crosses line 2). Line 2—which runs east to west, crossing deep under the river—is more practical; handy stops are Rondo Daszyńskiego (near the Warsaw Uprising Museum); Świętokrzyska (a transfer station between the two lines); Nowy Świat-Uniwersytet (in the middle of the Royal Way, near the Copernicus Monument); Centrum Nauki Kopernik (on the riverbank, near the Copernicus Science Center); and Stadion Narodowy (National Stadium).

By Taxi: As in most big Eastern European cities, it’s wise to use only cabs that are clearly marked with a company logo and telephone number (or call your own: Locals like City Taxi, tel. 19459; MPT Radio Taxi, tel. 19191; or Ele taxi, tel. 22-811-1111). All official taxis have similar rates: 8 zł to start, then 3 zł per kilometer (4.50 zł after 22:00 or in the suburbs). The drop fee may be higher if you catch the cab in front of a fancy hotel. Note that Uber is active in Warsaw—if you’re comfortable using it back home, it works the same way here, and is often cheaper.

Each year, new companies crop up offering walking tours in Warsaw. These tend to have one of two approaches: A “free” tour of the main sights (with generous tipping expected); or communism-themed tours, often with a ride to a gloomy apartment-block area for a taste of the Red old days. The options change often, so survey the latest ones, do some homework (check online reviews), and pick a tour that suits your interests. The TI and most hotels have brochures.

Having a talented local historian as your guide in this city, with such a complex and powerful story to tell, greatly enhances your experience. I’ve worked with two excellent young guides: the smart and charming Monika Oleśko (320 zł/3 hours, 480 zł/5.5 hours, more for larger groups; by bike or by car; mobile 784-832-718, warsawteller.wordpress.com, olesko.monika@gmail.com) and the professorial Hubert Pawlik (660 zł for 5 hours on foot or with his car, or 115 zł per person for a walking tour, mobile 502-298-105, www.warsaw-citytours.com). Hubert’s big, comfy SUV can fit a small group. Both Monika and Hubert can do theme tours or tailor the time to your interests.

Eat Polska does excellent food and vodka tours around this fast-emerging foodie mecca. A top-quality guide will take your small group (maximum 6 people for the food tours, 12 for the vodka tours) to a variety of restaurants and bars around the city, with tasting samples at each one. The guides do an exceptional job of providing insightful context about what you’re tasting, making this educational about both Polish cuisine and Polish culture in general. If you have a serious interest in food, this is the most worthwhile tour in town (food tours typically daily at 13:00, 290 zł, 4 hours; vodka tours with food pairings daily at 17:00, 260 zł, 3.5 hours; contact to arrange details, www.eatpolska.com).

Warsaw’s spread-out landscape makes it a natural for a hop-on, hop-off bus—although heavy traffic may make you wish you’d taken a tram or the Metro instead. Two competing companies offer tours around Warsaw (60 zł/24 hours, 80 zł/48 hours): CitySightseeing, with red buses, has two routes and generally better frequency; I’d skip City-Tour (with yellow buses), which runs only once hourly.

PART 1: PALM TREE CIRCLE AND NOWY ŚWIAT

PART 2: KRAKOWSKIE PRZEDMIEŚCIE

Church of the Holy Cross (Kośicół Św. Kryża)

Statue of Christ Bearing the Cross

Church of the Nuns of the Visitation (Kośicół Sióstr Wizytek)

Piłsudski Square (Plac Marszałka Józefa Piłsudskiego)

(See “Central Warsaw” map, here.)

The Royal Way (Szłak Królewski) is the six-mile route that the kings of Poland used to travel from their main residence (at Castle Square in the Old Town) to their summer home (Wilanów Palace, south of the center and not worth visiting). This self-guided walk covers a one-mile section of the Royal Way in the heart of the city—from Palm Tree Circle to the castle. This is a busy, mostly-pedestrian boulevard with two different names: At the south end, vibrant Nowy Świat offers shops, restaurants, and a good glimpse of urban Warsaw; to the north, and ending at the Old Town, Krakowskie Przedmieście is lined with historic landmarks and is better for sightseeing. Not counting sightseeing stops, figure about 30 minutes to walk along Nowy Świat (“Part 1”), then another 30 minutes along Krakowskie Przedmieście to the Old Town (“Part 2”).

• Start this walk at the traffic circle officially named for Charles de Gaulle, but colloquially known as...

This is one of the city’s main intersections, marked by the quirky and now iconic palm tree. Stand near the communist-era monument under the spruce trees (on the curb, kitty-corner from the biggest building) and get oriented.

You’re standing at the intersection of two major boulevards: Nowy Świat (where we’re heading next) and Jerusalem Avenue (aleja Jerozolimskie, which heads from Warszawa Centralna station across the river). This street once led to a Jewish settlement called New Jerusalem. Like so much else in Warsaw, it’s changed names many times. Between the World Wars, it became “May 3rd Avenue,” celebrating Poland’s 1791 constitution (Europe’s first). But this was too nationalistic for the occupying Nazis, who called it simply Bahnhofstrasse (“Train Station Street”). Then the communists switched it back to “Jerusalem,” strangely disregarding the religious connotations of that name. (Come on, guys—what about a good, old-fashioned “Stalin Avenue”?) The strikingly wide boulevards were part of the city’s post-WWII Soviet rebuilding. Communist urban planners felt that eight- to twelve-lane roads were ideal for worker pageantry like big May Day parades...and, when the workers aren’t happy, for Soviet tanks to thunder around, maintaining order.

You can’t miss the giant palm tree in the middle of Jerusalem Avenue. When a local artist went to the real Jerusalem, she was struck by the many palm trees—and wanted to erect one along Warsaw’s own little stretch of “Jerusalem.” This artificial palm tree went up in 2002 as a temporary installation. It was highly controversial, dividing the neighborhood. One snowy winter day, the pro-palm tree faction—who appreciated the way the tree spiced up this otherwise dreary metropolis—camped out here in bikinis and beachwear to show their support. They prevailed, and the tree is now a permanent fixture.

The big, blocky building across the street (behind statue of de Gaulle) was the headquarters of the Communist Party, built in 1948. Nowy Świat translates as “New World,” inspiring a popular communist-era joke: What do you see when you turn your back on the Communist Party? A “New World.” Ironically, when the economy was privatized in 1991, this building became home to Poland’s stock exchange. And then the country’s only dealership for Ferraris—certainly not an automobile for the proletariat—moved in downstairs.

On the corner in front of the former Communist Party HQ, a statue of Charles de Gaulle strides confidently up the street. A gift from the government of France, this celebrates the military tactician who came to Warsaw’s rescue when the Red Army invaded from the USSR after World War I.

To the left of the Communist Party building is the vast National Museum—a good place for a fascinating lesson in Polish art (see the self-guided tour on here).

Before walking down Nowy Świat, notice the small but powerful monument near you. In 1956, this was dedicated to the “Poles who fought for People’s Poland”—with a strong communist connotation. In a classic example of Socialist Realism, the communists appropriated a religious theme that Poles were inclined to embrace (this pietà composition)...and politicized it. But in 2014, the statue was rededicated to the “partyzantom who fought for free Poland in World War II.” “Partisan” was a bad word in the 1950s, when it was used to describe the soldiers of the Polish Home Army—which fought against both the Nazis and the Soviets.

• From here, turn your back to the Communist Party building and head into a new world—down Nowy Świat—to the first intersection. As you stroll, notice how massive and intense Warsaw suddenly becomes more intimate and accessible.

This charming shopping boulevard is lined with boutiques, cafés, and restaurants—it’s the most upscale, elegant-feeling part of the city. Before World War II, Nowy Świat was Warsaw’s most popular neighborhood. And today, once again, rents are higher here than anywhere else in town. While most tourists flock into the Old Town, Varsovians and visiting businesspeople prefer this zone and farther south. The city has worked hard to revitalize this strip with broader, pedestrian-friendly sidewalks, flower boxes, and old-time lampposts.

Look down the street and notice the consistent architecture. In the 1920s, this was anything but cohesive: an eclectic and decadent strip of Art Deco facades, full of individualism. Rather than rebuild in that “trouble-causing” style, the communists used an idealized, more conservative, Neoclassical style, which feels more like the 1820s than the 1920s.

Ulica Chmielna, the first street to the left, is an appealing pedestrian boutique street leading to Emil Wedel’s chocolate heaven (a five-minute walk away; described later, under “Eating in Warsaw”). Between here and the Palace of Culture and Science stretches one of Warsaw’s top shopping neighborhoods (culminating at the Galleria Centrum mall, just across from the Palace).

Across the street from Chmielna (on the right) is the restaurant street called Foksal. On a balmy summer evening, this street is filled with chatty al fresco diners.

A few steps farther down Nowy Świat, on the left, don’t miss the recommended A. Blikle pastry shop and café—the place in Poland to buy sweets, especially pączki (rose-flavored jelly doughnuts; see here). Step inside for a dose of the 1920s: good-life Art Deco decor and historical photos. Or, if you’re homesick for Starbucks, drop in to one of the many gourmet coffee shops that line this stretch of Nowy Świat—with American-style lattes “to go” (one of many American customs that the Poles have embraced).

A half-block down the street (on the left, at #39) is a rare surviving bit of preglitz Nowy Świat: Bar Mleczny Familijny, a classic milk bar—a government-subsidized cafeteria filled with locals seeking a cheap meal (an interesting cultural artifact, but not recommended for a meal; for more about milk bars, see here). Don’t be surprised if it’s gone by the time you visit; in this high-rent district, it’s unlikely that these few remaining holdovers from the old days will survive for much longer.

Eat and shop your way along Nowy Świat. About one more block down, Ordynacka street (on the right) leads downhill to the Chopin Museum, worth considering for musical pilgrims.

• Continuing along Nowy Świat through a duller stretch, you’ll walk alongside a hulking, gloomy building before popping out in a pleasant square with a big statue of Copernicus.

• The street name changes to Krakowskie Przedmieście at the big...

This statue, by the great Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, stands in front of the Polish Academy of Science. Mikołaj Kopernik (1473-1543) was born in Toruń and went to college in Kraków. The Nazis stole his statue and took it to Germany (which, like Poland, claims Copernicus as its own). Now it’s back where it belongs. The concentric circles radiating from the front of the statue represent the course of the planets’ orbits, from Mercury to Saturn.

Just to Copernicus’ left is a low-profile, black-marble Chopin bench—one of many scattered around the center. These benches mark points related to his life (in this case, his sister lived across the street). Each of these benches plays Chopin’s music with the push of a button (though because of passing traffic, this one is tough to hear).

Directly in front of the statue, in the glass case, find a replica of a Canaletto painting of this same street scene in 1778, and compare it to today’s reality. As the national archives were destroyed, city builders referred to historic paintings like these for guidance after WWII. You’ll see other Canaletto replicas like this one scattered around the city.

• Across from Copernicus, the Church of the Holy Cross is worth a look.

We’ll pass many churches along this route, but the Church of the Holy Cross is unique (free entry). Composer Fryderyk Chopin’s heart is inside one of the pillars of the nave (first big pillar on the left, look for the marker). After two decades of exile in France, Chopin’s final wish was to have his heart brought back to his native Poland after his death. During World War II, the heart was hidden away in the countryside for safety. Check out the bright gold chapel, located on the left as you face the altar, near the front of the church. It’s dedicated to a saint whom Polish Catholics believe helps them with “desperate and hopeless causes.” People praying here are likely dealing with some tough issues. The beads draped from the altarpieces help power their prayers, and the many little brass plaques are messages of thanks for prayers answered.

In the back-left corner (as you face the altar) is a chapel dedicated to Poland’s favorite son, St. John Paul II. His ghostly image appears out of the wall; beneath him is a rock inscribed with the words Tu es Petrus (Latin for “You are Peter”—what Jesus said when he made St. Peter the first-ever pope), embedded with a capsule containing JPII’s actual blood. Just opposite, in the back-right corner, behind the giant barbed wire, is a memorial to the 22,000 Polish POWs—mostly officers and prominent civilians—massacred by Soviet soldiers in 1940 near Katyń, a village in today’s Russia. Stalin was determined to decapitate Poland’s military intelligentsia in a ruthless mass killing, which Poles have never forgotten.

• Leaving the church, imagine how locals would relate to the 19th-century, bronze-and-granite...

In front, a placard reads, “Lift up your hearts.” Even as Warsaw bore the burden of Russian occupation, this statue inspired them to be strong and not lose hope. It was one of many crosses they bore: a Catholic nation pinched between Orthodox Russians and Protestant Germans.

• Cross the street (appreciating how pedestrian-friendly it is—crossing here used to be a game of Frogger), and continue left.

A long block up the street on the right, you’ll see the gates (marked Uniwersytet) to the main campus of Warsaw University, founded in 1816. This lively student district has plenty of bookstores and cafeterias.

The 18th century was a time of great political decline for Poland, as a series of incompetent foreign kings mishandled crises and squandered funds. But ironically, it was also Warsaw’s biggest economic boom time. Along this boulevard, aristocratic families of the period built mansions—most of them destroyed during World War II and rebuilt since. Some have curious flourishes (just past the university on the right, look for the doorway supported by four bearded brutes admiring their overly defined abs). Over time, many of these families donated their mansions to the university.

• The bright-yellow church a block up from the university, on the right, is the...

This Rococo confection from 1761 is the only church on this walk that survived World War II, and is notable because Chopin was briefly the organist here.

The monument in front of the church commemorates Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński, who was the Polish primate (the head of the Polish Catholic Church) from 1948 to 1981. He took this post soon after the arrival of the communists, who opposed the Church, but also realized it would be risky for them to shut down the churches in such an ardently religious country. The Communist Party and the Catholic Church coexisted tensely in Poland, and when Wyszyński protested a Stalinist crackdown in 1953, he was arrested and imprisoned. Three years later, in a major victory for the Church, Wyszyński was released. He continued to fight the communists, becoming a great hero of the Polish people in their struggle against the regime.

Across the street is another then-and-now Canaletto illustration.

• Farther up (on the right, past the park) is the elegant, venerable...

A striking building with a round turret on its corner, the Hotel Bristol was used by the Nazis as a VIP hotel and bordello, and survived World War II. If you wander through any fancy Warsaw lobby...make it this one. Step in like you’re staying here and explore its fine public spaces, with fresh Art Deco and Art Nouveau flourishes. The café in front retains its Viennese atmosphere, but the pièce de résistance is the stunning Column Bar deeper in, past the dramatically chandeliered lounge.

• Leave the Royal Way briefly here to reach Piłsudski Square (a block away, up the street opposite Hotel Bristol).

The vast, empty-feeling Piłsudski Square (pew-SOOD-skee) has been important Warsaw real estate for centuries, constantly changing with the times. In the 1890s, the Russians who controlled this part of Poland began construction of a huge and magnificent Orthodox cathedral on this spot. But soon after it was completed, Poland regained its independence, and anti-Russian sentiments ran hot. So in the 1920s, just over a decade after the cathedral went up, it was torn down. During the Nazi occupation, this square took the name “Adolf-Hitler-Platz.” Under the communists, it was Zwycięstwa, meaning “Victory” (of the Soviets over Hitler’s fascism). When the regime imposed martial law in 1981, the people of Warsaw silently protested by filling the square with a giant cross made of flowers. The huge plaque in the ground near the road (usually marked by flowers) commemorates two monumental communist-era Catholic events on this square: John Paul II’s first visit as pope to his homeland on June 2, 1979; and the May 31, 1981 funeral of Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński, whom we met across the street. The cross nearby also honors the 1979 papal visit, with one of his most famous and inspiring quotes to his countrymen: “Let thy spirit descend, let thy spirit descend, and renew the face of the earth—of this earth” (meaning Poland, in a just-barely-subtle-enough dig against the communist regime that was tolerating his visit). More recently, on April 17, 2010, more than 100,000 Poles convened on this square for a more solemn occasion: a memorial service for President Lech Kaczyński, who had died in a tragic plane crash in Russia.

Stand in the center, near the giant plaque, with the Royal Way at your back, for this quick spin-tour orientation: Ahead are the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and Saxon Garden (explained later); 90 degrees to the right is the old National Theater, eclipsed by a modern business center/parking garage; another 90 degrees to the right is a statue of Piłsudski (which you passed to get here—described later); and 90 more degrees to the right is the Sofitel—formerly the Victoria Hotel, the ultimate plush, top-of-the-top hotel where all communist-era VIPs stayed. To the right of the hotel, on the horizon, you can see Warsaw’s newly emerging skyline. The imposing Palace of Culture and Science, which once stood alone over the city, is now joined by a cluster of brand-new skyscrapers, giving Warsaw a Berlin-esque vibe befitting its important role as a business center of Eastern Europe.

Walk to the fragment of colonnade by the park that marks the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (Grób Nieznanego Żołnierza). The colonnade was once part of a much larger palace built by the Saxon prince electors (Dresden’s Augustus the Strong and his son), who became kings of Poland in the 18th century. After the palace was destroyed in World War II, this fragment was kept to memorialize Polish soldiers. The names of key battles over 1,000 years are etched into the columns, the urns contain dirt from major Polish battlefields, and the two soldiers are pretty stiff. Every hour on the hour, they do a crisp Changing of the Guard—which, poignantly, honors those who have perished in this country, so shaped by wars against foreign invaders.

Just behind the Tomb is the stately Saxon Garden (Ogród Saski), inhabited by genteel statues, gorgeous flowers, and a spurting fountain. This park was also built by the Saxon kings of Poland. Like most foreign kings, Augustus the Strong and his son cared little for their Polish territory, building gardens like these for themselves instead of investing in more pressing needs. Poles say that foreign kings such as Augustus did nothing but “eat, drink, and loosen their belts” (it rhymes in Polish). According to Poles, these selfish absentee kings were the culprits in Poland’s eventual decline. But they do appreciate having such a fine venue for a Sunday stroll.

Walk back out toward the Royal Way, stopping at the statue you passed earlier. In 1995, the square was again renamed—this time for Józef Piłsudski (1867-1935), the guy with the big walrus moustache. With the help of a French captain named Charles de Gaulle (whom we met earlier), Piłsudski forced the Russian Bolsheviks out of Poland in 1920 in the so-called Miracle on the Vistula. Piłsudski is credited with creating a once-again-independent Poland after more than a century of foreign oppression, and he essentially ran Poland as a virtual dictator after World War I. Of course, under the communists, Piłsudski was swept under the rug. But since 1989, he has enjoyed a renaissance as many Poles’ favorite prototype anticommunist hero. His name adorns streets, squares, and bushy-mustachioed monuments all over the country.

• Return to Hotel Bristol, turn left, and continue your Royal Way walk.

Next door to the hotel, you’ll see the huge Radziwiłł Palace. The Warsaw Pact was signed here in 1955, officially uniting the Soviet satellite states in a military alliance against NATO. This building has also, from time to time, served as the Polish “White House.”

• Beyond Radziwiłł Palace, on the right, you’ll reach a park with a...

Poland’s national poet, Adam Mickiewicz spearheaded Poland’s cultural survival during more than a century when the country disappeared from maps—absorbed by Austria, Prussia, and Russia. This was an age when underdog nations (and peoples without nations) all over Europe had their own national revival movements. The statue was erected in 1898 with permission from the Russian czar, as long as the people paid for it themselves. It’s still an important part of community life: Polish high school students have a big formal ball (like a prom) 100 days before graduation. After the ball, if students come here and hop around the statue on one leg, it’s supposed to bring them good luck on their finals. Mickiewicz, for his part, looks like he’s suffering from a heart attack—perhaps in response to the impressively ugly National Theater and Opera a block in front of him.

• Continue to the end of the Royal Way, marked by the big pink palace. Just before the castle, on your right, is...

This church is Rococo, with playful capitals inside and out and a fine pulpit shaped like the prow of a ship—complete with a big anchor. The richly ornamented apse, behind the altar, survived World War II. This church offers organ concerts nearly daily in summer (see “Entertainment in Warsaw,” later).

For a scenic finale to your Royal Way stroll, climb the 150 steps of the view tower by the church (5 zł, generally open daily 10:00-18:00, later in summer, closed in bad winter weather). You’ll be rewarded with excellent views—particularly of Castle Square and the Old Town. From up top, visually retrace your steps along the Royal Way, and notice the emerging skyline surrounding the Palace of Culture and Science. The tower also affords a good look at the Praga district across the river, where the Red Army waited for the Nazis to level Warsaw during the uprising. Help was so close at hand...but stayed right where it was.

• Just across from the view tower entrance, look for another Chopin bench. From St. Anne’s Church, it’s just another block to Castle Square, the TI, and the start of the Old Town.

▲▲Royal Castle (Zamek Królewski)

Cathedral of St. John the Baptist (Katedra Św. Jana Chrzciciela)

▲▲Old Town Market Square (Rynek Starego Miasta)

History Museums near the Square

From the New Town to Castle Square

East of the Royal Way (Toward the River)

▲▲National Museum (Muzeum Narodowe)

Chopin Museum (Muzeum Fryderyka Chopina)

▲▲Copernicus Science Center (Centrum Nauki Kopernik)

West of the Royal Way (near Centralna Station)

Palace of Culture and Science (Pałac Kultury i Nauki, or PKiN)

▲Ghetto Heroes Square (Plac Bohaterow Getta)

▲▲▲Museum of the History of Polish Jews (Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich, a.k.a. POLIN)

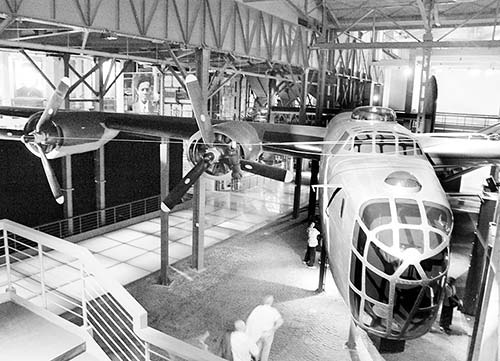

▲▲Warsaw Uprising Museum (Muzeum Powstania Warszawskiego)

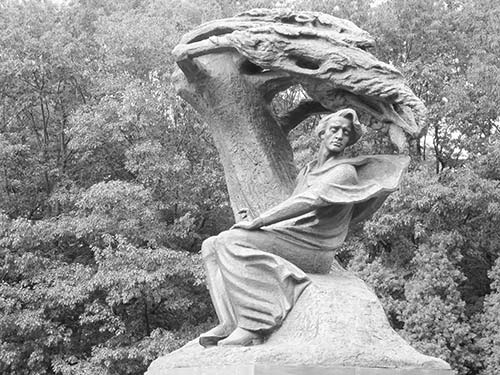

▲Łazienki Park (Park Łazienkowski)

In 1945, not a building remained standing in Warsaw’s “Old” Town (Stare Miasto). Everything you see is rebuilt, mostly finished by 1956. Some think the Old Town seems artificial and phony, in a Disney World kind of way. For others, the painstaking postwar reconstruction feels just right, with Old World squares and lanes charming enough to give Kraków a run for its money. Before 1989, stifled by communist repression and choking on smog, the Old Town was an empty husk of its historic self. But now, the outdoor restaurants and market stalls have returned, and tourists (and a few Varsovians) are out strolling.

These sights are listed in order from south to north, and linked with walking directions, beginning at Castle Square and ending at the New Town.

This lively square is dominated by the big, pink Royal Castle that is the historic heart of Warsaw’s political power.

After the second great Polish dynasty—the Jagiellonians—died out in 1572, it was replaced by the Republic of Nobles (about 10 percent of the population), which elected various foreign kings to their throne. The guy on the 72-foot-tall pillar is Sigismund III, the first Polish king from the Swedish Vasa family (Waza in Polish). In 1596, he relocated the capital from Kraków to Warsaw. This move made sense, since Warsaw was closer to the center of 16th-century Poland (which had expanded to the east), and because the city had gained political importance over the past 30 years as the meeting point of the Sejm, or parliament of nobles.

Along the right side of the castle, notice the two previous versions of this pillar lying on a lawn. The first one, from 1644, was falling apart and had to be replaced in 1887 by a new one made of granite. In 1944, a Nazi tank broke this second pillar—a symbolic piece of Polish heritage—into the four pieces (still pockmarked with bullet holes) that you see here today. As Poland rebuilt, its citizens put Sigismund III back on his pillar. Past the pillars are views of Warsaw’s red-and-white National Stadium across the river—built for the Euro Cup soccer tournament in 2012.

Across the square from the castle, you’ll see the partially reconstructed defensive wall. This rampart once enclosed the entire Old Town. Like all of Poland, Warsaw has seen invasion from all sides.

Explore the café-lined lanes that branch off Castle Square. Street signs indicate the year that each lane was originally built.

The first street is ulica Piwna (“Beer Street”), where you’ll find St. Martin’s Church (Kośicół Św. Martina, on the left). Run by Franciscan nuns, this church has a simple, modern interior. Walk up the aisle and find the second pillar on the right. Notice the partly destroyed crucifix—it’s the only church artifact that survived World War II. Across the street and closer to Castle Square, admire the carefully carved doorway of the house called pod Gołębiami (“Under Doves”)—dedicated to the memory of an old woman who fed birds amidst the Old Town rubble after World War II.

Back on Castle Square, find the white plaque on the wall (at plac Zamkowy 15). It explains that 50 Poles were executed by Nazis on this spot on September 2, 1944. You’ll see plaques like this all over the Old Town, each one commemorating victims or opponents of the Nazis. The brick planter under the plaque is often filled with fresh flowers to honor the victims.

• Turn your attention to the...

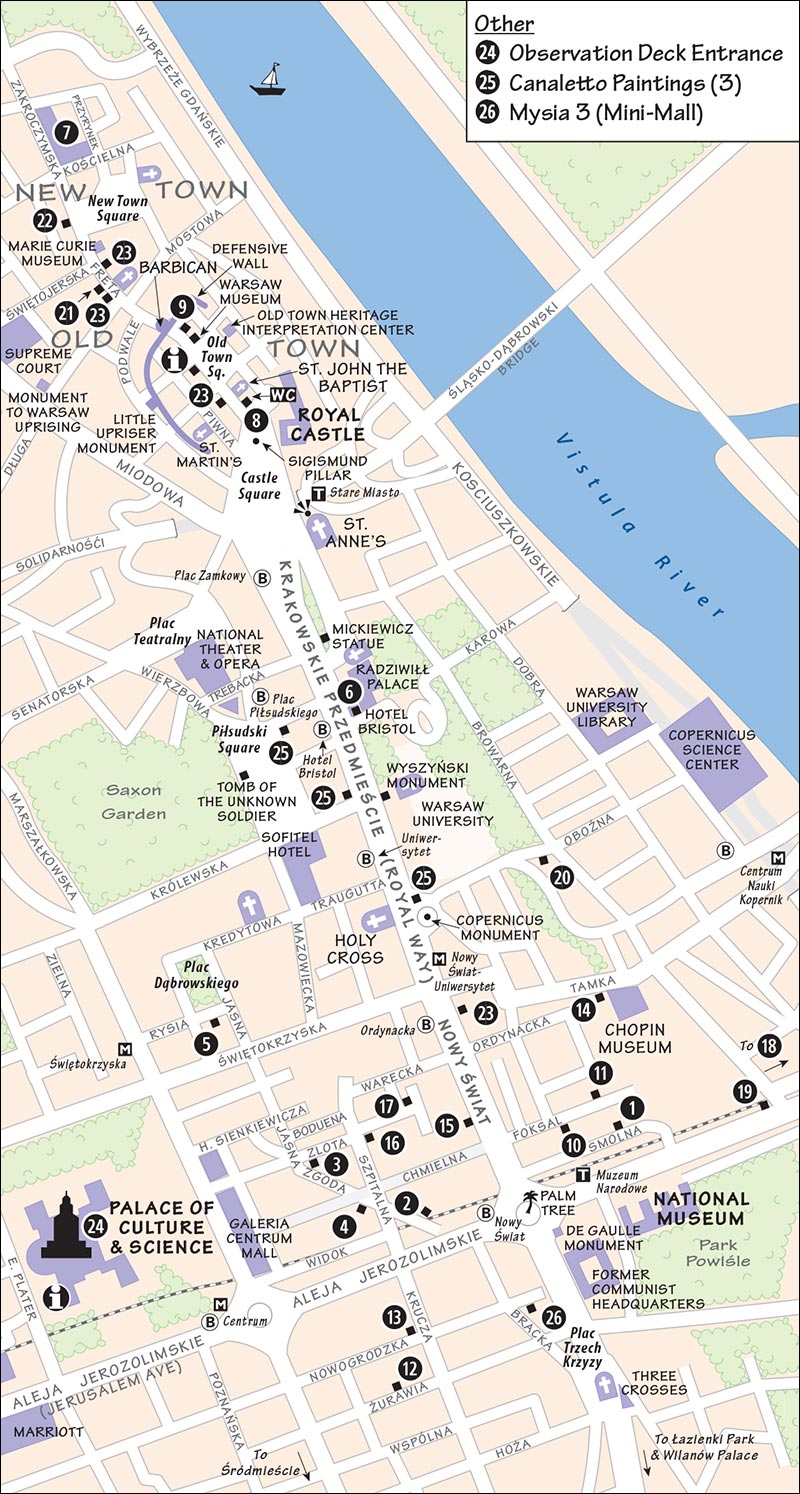

A castle has stood here since the Mazovian dukes built a wooden version in the 14th century. It has grown through the ages, being rebuilt and remodeled by many different kings. When Warsaw became the capital in 1596, this massive building served a dual purpose: It was both the king’s residence and the meeting place of the parliament (Sejm). It reached its peak under Stanisław August Poniatowski—the final Polish king—who imported artists and architects to spiff up the interior, leaving his mark all over the place. Luftwaffe bombs destroyed it in World War II (only one wall remained standing). Rebuilding stalled because Stalin considered it a palace for the high-class elites. It was finally rebuilt in the more moderate 1970s, funded by local donations.

Warsaw’s Royal Castle has a gorgeous interior—the most opulent I’ve seen in Poland. Many of the furnishings are original (hidden away when it became clear the city would be demolished in World War II). A visit to the castle is like perusing a great Polish history textbook. In fact, you’ll likely see grade-school classes sitting cross-legged on the floors. Watching the teachers quizzing eager young history buffs, try to imagine what it’s like to be a young Pole growing up in a country with such a tumultuous history.

Cost and Hours: 23 zł, free on Sun; open May-Sept Mon-Sat 10:00-18:00, Thu until 20:00, Sun 11:00-18:00; Oct-April Tue-Sat 10:00-16:00, Sun 11:00-16:00, closed Mon; last entry one hour before closing; plac Zamkowy 4, tel. 22-355-5170, www.zamek-krolewski.pl. A public WC is on the courtyard just around the corner of the castle.

Tours: The castle has a well-produced audioguide (17 zł, worth the extra cost) and good English information posted throughout. For the basics, use my commentary to follow the one-way route through the castle.

Visiting the Castle: Because the castle visitor route often changes, it’s possible you won’t see these rooms in this order; if that happens, match the labels in each room to the corresponding text below.

Entering the courtyard, go to the right to buy tickets, then cross to the opposite side to tour the interior. (If you want an audioguide, go downstairs to rent it first.) Head up the stairs and follow Castle Route signs.

Start in the Oval Gallery, then head into the Council Chamber, where a “Permanent Council” consisting of the king, 18 senators, and 18 representatives met to chart Poland’s course. Next is the Great Assembly Hall, heavy with marble and chandeliers. The statues of Apollo and Minerva flanking the main door are modeled after King Stanisław August Poniatowski and Catherine the Great of Russia, respectively. (The king enjoyed a youthful romantic dalliance with Catherine on a trip to Russia, and never quite seemed to get over her...much to his wife’s consternation, I’m sure.)

The Knights’ Hall features the Polish Hall of Fame, with paintings of great events and busts and portraits of VIPs—Very Important Poles. The statue of Chronos—god of time, with the globe on his shoulders—is actually a functioning clock, though now it’s stopped at 11:15 to commemorate the exact time in 1944 when the Nazis bombed this palace to bits. Just off this hall is the Marble Room, with more portraits of Polish greats ringing the top of the room. Above the fireplace is a portrait of Stanisław August Poniatowski.

Continuing through the Knights’ Hall, you’ll wind up in the remarkable Throne Room. Notice the crowned white eagles, the symbol of Poland, decorating the banner behind the throne. The Soviets didn’t allow anything royal or aristocratic, so postwar restorations came with crownless eagles. Only after 1989 were these eagles crowned again. Peek into the European Monarchs’ Portrait Rooms, where you’ll meet the likes of Russia’s Catherine the Great, England’s George III, and France’s Louis XVI—in whose esteemed royal league Stanisław August Poniatowski liked to consider himself.

After four more grand rooms (including the King’s Bedroom, with a gorgeous silk canopy over the bed), you’ll enter the Canaletto Room, filled with canvases of late-18th-century Warsaw painted in exquisite detail by this talented artist. (This Canaletto, also known for his panoramas of Dresden, was the nephew of another more famous artist with the same nickname, known for painting Venice’s canals.) Paintings like these helped post-WWII restorers resurrect the city from its rubble. To the left, on the lower wall, the biggest canvas features the view of Warsaw from the Praga district across the river; pick out the few landmarks that are still standing (or, more precisely, have been resurrected). The castle you’re standing in dominates the center of the painting, overlooking the river. Notice the artist’s self-portrait in the lower left. Opposite, on the right side of the room, is Canaletto’s depiction of the election of Stanisław August Poniatowski as king, in a field outside Warsaw (notice the empty throne in the middle of the group). Among the assembled crowd, each flag represents a different Polish province.

From here, head left of the big “view of Warsaw” painting into the side chapel, reserved for the king. In the box to the left of the altar is the heart of Tadeusz Kościuszko, a hero of both the American Revolution and the Polish struggle against the Partitions (for more about the Partitions, see here).

As you cross over to the other part of the castle, you’ll pass through the Four Seasons Gallery (with some fine but faded Gobelin tapestries) before entering a few rooms occupied by the houses of parliament—a reminder that this “castle” wasn’t just the king’s house, but also the meeting place of the legislature. In the New Deputies’ Chambers, notice the maps showing Poland’s constantly in-flux borders—a handy visual aid for the many school groups that visit here.

After several rooms, you’ll reach the grand Senators’ Chamber, with the king’s throne, surrounded by different coats of arms. Each one represents a region that was part of Poland during its Golden Age, back when it was united with Lithuania and its territory stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea (see the map on the wall). In this room, Poland adopted its 1791 constitution (notice the replica in the display case to the left of the throne). It was the first in Europe, written soon after America’s and just months before France’s. And, like the Constitution of the United States, it was very progressive, based on the ideals of the Enlightenment. But when the final Partitions followed in 1793 and 1795, Poland was divided between neighboring powers and ceased to exist as a country until 1918—so the constitution was never fully put into action.

Next, the Crown Prince’s Room features paintings by Jan Matejko that capture the excitement surrounding the adoption of this ill-fated constitution (for more on Matejko, see here). The next room has another Matejko painting: King Stefan Batory negotiating with Ivan the Terrible’s envoys to break their siege of a Russian town. Notice the hussars—fearsome Polish soldiers wearing winged armor. Finally, you’ll wind through more rooms with yet more paintings of great historical events and portraits of famous Poles.

Other Castle Sights: Sharing an entrance lobby with the main castle interiors, the Gallery of Paintings, Sculpture, and Decorative Arts isn’t worth the 21-zł extra admission fee for most visitors; save your time and money for the National Museum instead. But art lovers may be interested to see the 36 paintings of the gallery’s Landkrońoski Collection. These originally belonged to Stanisław August Poniatowski, who sold them to an aristocratic family that eventually presented them to Poland as a gift. The prize of the gallery are two canvases by Rembrandt (both from 1641). Girl in a Picture Frame is exactly that—except that she’s “breaking the frame” by resting her hands on a faux frame that Rembrandt has painted inside the real one...shattering the fourth wall in a way that was unusual for the time. The other, A Scholar at His Writing Table, shows the hirsute academic glancing up from his notes. Circle around behind the canvases to see X-rays of the paintings, which have helped experts better understand the master’s techniques. The rest of the gallery consists of roomfuls of portraits and a fine cabinet of silver and crystal.

Consider a detour to the Kubicki Arcades (Arkady Kubiciego), the impressively excavated arcades deep beneath the castle. From the entrance lobby, head downstairs to the area with the cloakroom, bathrooms, and bookshop, then find the long escalator that takes you down to the arcades. It’s free to wander the long, cavernous, and newly clean and gleaming space, made elegant by grand drapes.

The castle has a vast collection, which it organizes into various exhibitions—some permanent and some temporary. The extensive oriental carpet collection in the “Tin-Roofed Palace” (Pałac pod Blachą) is sparsely described and skippable for most; the same building also features seven unimpressive apartments of Prince Józef Poniatowski, the king’s brother (15 zł for both, free on Sun, same hours as castle, around the right side of the castle as you face it—past the two fallen columns, buy ticket at main ticket desk).

• When you’re ready to resume exploring the Old Town, leave the square at the far end, on St. John’s Street (Świętojańska). On the plaque under the street name sign, you can guess what the dates mean, even if you don’t know Polish: This building was constructed from 1433 to 1478, destroyed in 1944, and rebuilt from 1950 to 1953.

Partway down the street on the right, you’ll come to the big brick...

This cathedral-basilica is the oldest (1370) and most important church in Warsaw. Superficially unimpressive, the church’s own archbishop admitted that it was “modest and poor”—but “the historical events that took place here make it magnificent” (much like Warsaw itself). Poland’s constitution was consecrated here on May 3, 1791. Much later, this church became the final battleground of the 1944 Warsaw Uprising—when a Nazi “tracked mine” (a huge bomb on tank tracks—this one appropriately named Goliath) drove into the church and exploded, massacring the rebels. You can still see part of that tank’s tread hanging on the outside wall of the church (through the passage on the right side, between the buttresses near the end of the church).

Cost and Hours: Free, crypt-5 zł, good guidebook-5 zł, open to tourists daily 10:00-13:00 & 15:00-17:30, closed during services and organ concerts. The cathedral hosts organ concerts in summer (see “Entertainment in Warsaw,” later).

Visiting the Cathedral: Head inside. Typical of brick churches, it has a “hall church” design, with three naves of equal height. Look for the crucifix ornamented with real human hair (chapel left of high altar). The high altar holds a copy of the Black Madonna—proclaimed “everlasting queen of Poland” after a victory over the Swedes in the 17th century. The original Black Madonna is in Częstochowa (125 miles south of Warsaw)—a mecca for Slavic Catholics, who visit in droves in hopes of a miracle. In the back-left corner, find the chapel with the tomb of Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński—the great Polish leader who, as Warsaw’s archbishop, morally steered the country through much of the Cold War. (Notice the request to pray for his beatification, as Poles would love to see him become a saint.) The crypt holds graves of several important Poles, including Stanisław August Poniatowski (the last Polish king) and Nobel Prize-winning author Henryk Sienkiewicz.

• Continue up the street and enter Warsaw’s grand...

For two centuries, this was a gritty market square. Sixty-five years ago, it was a pile of bombed-out rubble. And today, like a phoenix from the ashes, it’s risen to remind residents and tourists alike of the prewar glory of the Polish capital.

Head to the mermaid fountain in the middle of the square. The mermaid is an important symbol in Warsaw—you’ll see her everywhere. Legend has it that a mermaid (syrenka) lived in the Vistula River and protected the townspeople. While this siren supposedly serenaded the town, she’s most appreciated for her strength (hence the sword). This square seems to declare that life goes on in Warsaw, as it always has. Children frolic here, oblivious to the turmoil their forebears withstood. When the fountain gurgles, the kids giggle.

Each of the square’s four sides is named for a prominent 18th-century Varsovian: Kołłątaj, Dekert, Barss, and Zakrzewski. These men served as “Presidents” of Warsaw (mayors, more or less), and Kołłątaj was also a framer of Poland’s 1791 constitution. Take some time to explore the square. Enjoy the colorful architecture. Notice that many of the buildings were intentionally built to lean out into the square—to simulate the higgledy-piggledy wear and tear of the original buildings.

If you’d like to learn more about Warsaw’s history, two good museums are located nearby.

• First, on the Dekert (north) side of the square is the...

Warsaw Museum (Muzeum Warszawy): When this museum’s lengthy and long-delayed restoration is complete (possibly as early as mid-2017), it promises to provide an insightful look at the turbulent history of this city—particularly the Old Town. The exhibits are an afterthought to the museum’s best feature: a poignant 20-minute film (in English) tracing the tragic WWII experience of this city—from a thriving interwar metropolis, to a bombed-out wasteland, to the focus of a massive rebuilding effort (may be covered by a separate ticket). For the latest, see www.muzeumwarszawy.pl.

• The other museum—focusing on the Old Town’s history and reconstruction—is behind the buildings on the river side of the square (behind the mermaid’s back). Walk one block, and turn left to find the...

Old Town Heritage Interpretation Center: This fine little visitors center displays lots of before-and-after photos and videos of the Old Town—there are even glass floors looking down onto original fragments of the neighborhood (5 zł, Tue-Sun 10:00-19:00, closed Mon, ulica Brzozowa 11, www.muzeumwarszawy.pl).

• When you’re ready to move on, exit the square on Nowomiejska (at the mermaid’s 2 o’clock, by the second-story niche sculpture of St. Anne). After a block, you’ll reach the...

This defensive gate of the Old Town, similar to Kraków’s, protected the medieval city from invaders.

• Once you’ve crossed through the barbican, you’re officially in Warsaw’s...

This 15th-century neighborhood is “new” in name only: It was the first part of Warsaw to spring up outside the city walls (and is therefore slightly newer than the Old Town). The New Town is a fun place to wander: only a little less charming than the Old Town, but with a more real-life feel—people live and work here. Its centerpiece is the New Town Square (Rynek Nowego Miasta), watched over by the distinctive green dome of St. Kazimierz Church.

Scientists might want to pay homage at the museum (and birthplace) of Warsaw native Marie Skłodowska-Curie, a.k.a. Madame Curie (1867-1934); it’s along the street between the New Town Square and the barbican. This Nobel Prize winner was the world’s first radiologist—discovering both radium and polonium (named for her native land) with her husband, Pierre Curie. Since she lived at a time when Warsaw was controlled by oppressive Russia, she conducted her studies in France. The museum—with photos, furniture, artifacts, and a paucity of English information—is a bit of a snoozer, best left to true fans (overpriced at 11 zł, Tue-Sun 9:00-16:30, closed Mon, ulica Freta 16, tel. 22-831-8092, www.muzeum-msc.pl).

You can backtrack the way you came, or, to get a look at the Old Town’s back streets, consider this route from the big, round barbican gate (where the New Town meets the Old): Go back through the barbican and over the little bridge, turn right, and walk along the houses that line the inside of the wall. You’ll pass a leafy garden courtyard on the left—a reminder that people actually live in the tourist zone within the Old Town walls. Just beyond the garden on the right, look for the carpet-beating rack, used to clean rugs (these are common fixtures in people’s backyards). Go left into the square called Szeroki Dunaj (“Wide Danube”) and look for another mermaid (over the Thai restaurant). Continue through the square and turn right at Wąski Dunaj (“Narrow Danube”). After about 100 yards, you’ll pass the city wall. Just to the right (outside the wall), you’ll see the monument to the Little Upriser of 1944, a child wearing a grown-up’s helmet and too-big boots, and carrying a machine gun. Children—especially Scouts (Harcerze)—played a key role in the resistance against the Nazis. Their job was mainly carrying messages and propaganda.

Now continue around the wall (the upper, inner part is more pleasant). Admire more public art as you head back to Castle Square.

These sights are in the city center, near Palm Tree Circle—where Jerusalem Avenue crosses Nowy Świat.

A celebration of underrated Polish artists, this museum offers a surprisingly engaging and—if you follow my tour—concise overview of this country’s impressive painters (many of whom are unknown outside their home country). A modern, state-of-the-art exhibition space allows these unsung canvases to really belt it out. Polish and other European artists are displayed side by side, as if to assert Poland’s worthiness on the world artistic stage. After seeing a few of the masterpieces here, you won’t disagree.

Cost and Hours: 15 zł, includes audioguide, more for temporary exhibits, permanent collection free on Tue; open Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, Thu until 21:00, closed Mon, last entry 45 minutes before closing; one block east of Nowy Świat at aleja Jerozolimskie 3, tel. 22-629-3093, www.mnw.art.pl.

Self-Guided Tour: The collection fills several separate galleries. The museum’s strongest point—and the bulk of this tour—is its 19th-century Polish art. But before diving in, consider some of the other collections.

Self-Guided Tour: The collection fills several separate galleries. The museum’s strongest point—and the bulk of this tour—is its 19th-century Polish art. But before diving in, consider some of the other collections.

Overview: To get your bearings, pick up a floor plan as you enter. On the ground floor are Ancient Art (from Greek pieces to artifacts left by early Polish tribes); Gallery Faras (highlighting the museum’s fine collection of archaeological findings from that ancient Egyptian city); and a good collection of Medieval Art, which gathers altarpieces from churches around Poland—organized both chronologically and geographically—and displays some of the most graphic crucifixes and pietàs I’ve seen.

Upstairs is the excellent Gallery of 19th-Century Art (described next), which flows into the Old Polish and European Portrait Gallery (as interesting as somebody else’s yearbook). Nearby, through the gift shop, is the worthwhile 20th- and 21st-Century Art collection, with an impressive array of Modern and Postmodern Polish artists, including photographers and filmmakers. The underwhelming Old European Painting collection—pre-19th-century canvases arranged by theme and juxtaposed to highlight the differences between southern and northern European art—is split up among all three floors.

To cut to the chase, focus on the Gallery of 19th-Century Art. We’ll start with the granddaddy of Polish art, Jan Matejko.

• From the entrance lobby, head up the left staircase, then turn left across the mezzanine and enter the collection. Matejko is hiding at the far end of this wing: Entering the collection, angle right, then head all the way to the room at the far end, which is dominated by a gigantic battlefield canvas. (If you get lost, ask the attendants, “mah-TAY-koh?”)

Jan Matejko: While not the most talented of artists—he’s a fairly conventional painter, lacking a distinctive, recognizable style—Matejko more than made up for it with vision and productivity. His works—often on oversized canvases—are steeped in proud Polish history. Matejko’s biggest work here—in fact, the biggest canvas in the whole building—is the enormous Battle of Grunwald. This epic painting commemorates one of Poland’s high-water marks: the dramatic victory of a Polish-Lithuanian army over the Teutonic Knights, who had been terrorizing northern Poland for decades (for more on the Teutonic Knights, see here). On July 15, 1410, some 40,000 Poles and Lithuanians (led by the sword-waving Lithuanian in red, Grand Duke Vytautas) faced off against 27,000 Teutonic Knights (under their Grand Master, in white) in one of the medieval world’s bloodiest battles. Matejko plops us right in the thick of the battle’s climax, painting life-size figures and framing off a 32-foot-long slice of the actual two-mile battle line.

In the center of the painting, the Teutonic Grand Master is about to become a shish kebab. Duke Vytautas, in red, leads the final charge. And waaaay up on a hill (in the upper-right corner, on horseback, wearing a silver knight’s suit) is Władysław Jagiełło, the first king of the Jagiellonian dynasty...ensuring his bloodline will survive another 150 years.

Matejko spent three years covering this 450-square-foot canvas in paint. The canvas was specially made in a single seamless piece. This was such a popular work that almost as many fans turned out for its unveiling as there are figures in the painting. On the TV nearby, you can see how the vast painting was recently restored.

From Poland’s high point in the Battle of Grunwald, look on the right wall for another, much smaller Matejko canvas, Stańczyk, to see how Poland’s fortunes shifted drastically a century later. This more intimate portrait depicts a popular Polish figure: the court jester Stańczyk, who’s smarter than the king, but not allowed to say so. This complex character, representing the national conscience, is a favorite symbol of Matejko’s. Stańczyk slumps in gloom. He’s just read the news (on the table beside him) that the city of Smolensk has fallen to the Russians after a three-year siege (1512-1514). The jester had tried to warn the king to send more troops, but the king was too busy partying (behind the curtain). The painter Matejko—who may have used his own features for Stańczyk’s face—also blamed the nobles of his own day for fiddling while Poland was partitioned.

More Matejkos fill this room. Just to the right of Stańczyk is a self-portrait of the gray-bearded artist (compare their features), then a painting of the hoisting of the Sigismund Bell to the cathedral tower in Kraków (it’s still there). Farther right, you’ll see Matejko’s portraits of his children and his wife.

On the final wall is a smaller but very dramatic scene, The Sermon of Piotr Skarga. In the upper-right corner, this charismatic, early-17th-century Jesuit priest waves his arms to punctuate his message: Poland’s political system is broken. Skarga is addressing fat-cat nobles and the portly King Sigismund II Vasa (seated and wearing a ruffled collar), who were acting in their own self-interests instead of prioritizing what was best for Poland. Notice that Skarga’s audience isn’t hearing his ravings—they seem bored, bugged, or both. The king is even taking a nap. They should have listened: Poland’s eventual decline is often considered the fault of its unworkable political system. After the Partitions, the ahead-of-his-time Skarga was rehabilitated as a visionary who should have been heeded. Notice that, like Stańczyk, Skarga is a self-portrait of Matejko.

• Leaving Matejko, we’ll pass through several more rooms of lesser-known Polish painters to the opposite wing, where we’ll meet several of Matejko’s students—each of whom developed his own style and left his mark on the Polish art world. But on the way, I’ll point out a few canvases that may be worth pausing at.

Other Polish Painters: First, head back down the long corridor the way you came (passing some Matejko copycats), cutting through a corner of the Portrait Gallery. When you reach the door you came in, bear right to stay inside the gallery. At the end of that first, large room, you’ll find some battle scenes by Józef Brandt—the only painter who rivaled Matejko in capturing epic warfare on canvas. Many of Brandt’s scenes focus on confronting an enemy from the east, which was Poland’s lot for much of its history. His biggest work here, Rescue of Tatar Captives, is typical of his scenes.

Continue straight into the next room, with some fine landscape scenes. This room (the partition in the middle) also has works by the talented Józef Chełmoński: Indian Summer and (around back) Storks—a young boy and his grandfather look to the sky, as a formation of storks flies overhead.

Turn right and go through one more long room (watching, on the left wall, for Aleksander Gierymski’s small, evocative, personality-filled Jewish Woman Selling Oranges).

• You’ll emerge into a big room that kicks off the collection of...

Młoda Polska: Matejko’s pupils took what he taught them and incorporated the Art Nouveau styles that were emerging around Europe to create a new movement called “Young Poland” (see here). This room features works by two of the movement’s big names. On the left wall are paintings by Jacek Malczewski, some of them depicting the goateed, close-cropped artist in a semisurrealistic, Polish countryside context. Malczewski painted more or less realistically, but enjoyed incorporating one or two subtle, symbolic elements evocative of Polish folkloric tradition—like magical realism on canvas. The Death of Ellenai (1907) shows the pivotal scene in Juliusz Słowacki’s epic 1838 poem, Anhelli, in which a young nobleman exiled from Poland during the Partitions is forced to make his way through the wastelands of Siberia. When his young and idealistic travel companion, Ellenai, perishes, Anhelli kisses her feet and abandons all hope.

Most of the works on the opposite wall are by Józef Mehoffer, who paints with brighter colors in a more stylized form, with more abstraction. This creates dreamlike scenes that are, consequently, somehow less poignant than Malczewski’s. Mehoffer’s hypnotic Strange Garden is a bucolic vision of blue-clad Mary Poppinses, nude cherubs, lots of flowers...and a gigantic, hovering, golden dragonfly that places the otherwise plausible scene in the realm of pure fantasy. In the middle of the room, the small version of Auguste Rodin’s The Kiss reminds us how this emotion-conveying style, called Symbolism, was also finding expression elsewhere in Europe.

The next room, at the end of the hall, features some lesser-known painters from the age. Among these, Olga Boznańska’s works are worth lingering over: gauzy, almost Impressionistic portraits that skillfully capture the humanity of each subject.

Head back into the Malczewski/Mehoffer room and find the small, darkened adjoining rooms. The first one features additional Malczewski paintings; the second is a treasure trove of works by the founder and biggest talent of Młoda Polska, Stanisław Wyspiański. The specific items in this room are subject to change—as Kraków, which owns the best collection of hometown boy Wyspiański, is shuffling its works in and out of special exhibitions—but you’ll likely see both paintings and pastel works by this Art Nouveau juggernaut. Wyspiański also designed stage sets and redecorated some important churches; some of the large pastel-on-paper works you may see here were used as studies for those projects. And you’ll likely see some self-portraits and portraits of his wife and children. Pondering the works here—and throughout the museum—think about how such a talented artist from a small country can be left out of textbooks across the ocean.

The reconstructed Ostrogski Castle houses this slick museum honoring Poland’s most famous composer. You’ll see manuscripts, letters, and original handwritten compositions by the composer. Unfortunately, the museum’s high-tech gadgetry does more to distract from this rich collection of historic artifacts than to bring it to life. While Chopin devotees may find it riveting, those with only a passing familiarity with the composer may leave feeling like they still don’t know much about this Polish cultural giant.

Cost and Hours: 22 zł, free on Sun, open Tue-Sun 11:00-20:00, closed Mon, last entry 45 minutes before closing, 3 blocks east of Nowy Świat at ulica Okólnik 1, tel. 22-441-6251, www.chopin.museum. Because the museum is highly interactive, only 70 visitors are allowed per hour. But, except for rare occasions, just dropping in should be no problem.

Visiting the Museum: Buy your ticket at the adjacent building, then enter the mansion that houses the exhibit. You’ll be given an electronic card; tap it against glowing red dots to access additional information. You’ll proceed more or less chronologically through the composer’s life, with various opportunities to hear his compositions. You’ll see a replica of Chopin’s drawing room in Paris, and his last piano, which he used for composing during the final two years of his life (1848-1849). Exhibits here trace themes of the composer’s life, such as the women he knew (including his older sister Ludwika, his mother, and George Sand—the French author who took a male pseudonym in order to be published, and who was romantically linked with Chopin). The exhibit ends in the basement, where you can nurture your appreciation of Chopin by listening to his music.

Concerts: Under the palace is a new concert hall, which hosts performances by students (call museum to ask for concert schedule and to reserve a space—only 70 seats available; usually Oct-July Thu at 18:00, and typically free).

Eating: The recommended Tamka 43—with affordable lunch deals downstairs and top-end fine dining (with a menu inspired by dishes Chopin enjoyed) upstairs—is in the glassy building that faces the museum.

Other Chopin Sight: The composer’s tourable birth house is in a park in Żelazowa Wola, 34 miles from Warsaw. While interesting to Chopin devotees, it’s not worth the trek for most. On summer weekends, the Chopin Museum sometimes runs a handy bus to the house—ask at the museum (departs from Marszałkowska street, 30 minutes each way; 7 zł for the bus, 7 zł for the park, 23 zł for the park and birth house, 39 zł also includes museum in Warsaw; birth house open Tue-Sun 9:00-19:00, Oct-March until 17:00, closed Mon year-round, tel. 46-863-3300).

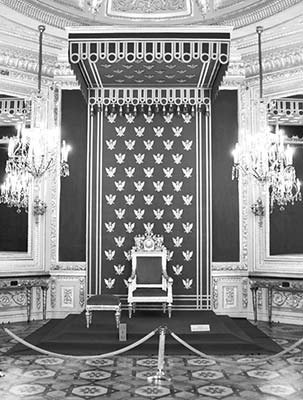

This facility, a wonderland of completely hands-on scientific doodads that thrill kids and adults alike, is a futuristic romper room. Filling two floors of an industrial-mod, purpose-built space, this is Warsaw’s best family activity. Exhibits are grouped more or less thematically and described in both Polish and English.

Cost and Hours: 27 zł, 18 zł for kids 19 and under, 72-zł family ticket for up to 4 people; open Tue-Fri 9:00-18:00, Sat-Sun 10:00-19:00, closed Mon, last entry one hour before closing; Wybrzeże Kościuszkowskie 20, tel. 22-596-4100, www.kopernik.org.pl.

Crowd-Beating Tips: This popular attraction can get crowded—especially on weekends and school holidays, when the line can be long. (A webcam on their website shows the current line; you can also book tickets in advance online, but the center’s website is in Polish only.) On weekdays, it’s generally no problem to walk right in.

Getting There: It’s an easy downhill walk from Warsaw’s Royal Way, but the hike back up is fairly steep. Near the modern bridge, you’ll find a Metro stop and a bus stop (both called Centrum Nauki Kopernik). From here, bus #102 goes to Nowy Świat, then up the Royal Way (Uniwersytet and Zachęta stops) before heading west to the Warsaw Uprising Museum. Metro line 2 connects the science center to the National Stadium, the Royal Way (near the Copernicus statue), and the Warsaw Uprising Museum.

Visiting the Center: Your ticket is a plastic card that you can insert into certain interactive exhibits. On the ground floor, the “Roots of Civilization” features working models of various tools and machines, demonstrating how humanity has mastered the mechanics of physics. You can play archaeologist in a sandbox, listen to Ode to Joy while tuning into different instruments, and see a small “fire tornado” (every bit as cool as it sounds). A playroom for toddlers, called “Buzzz!,” has a nature theme. Meanwhile, “RE: Generation” targets teens and adults with computer touchscreens that investigate the biological underpinnings of emotion—from what makes you laugh to what grosses you out—and examines how cultures around the world are both similar and different.

The “Heavens of Copernicus” planetarium requires a separate ticket (19 zł, 14 zł for kids 19 and under, in Polish with English headset, show starts at the top of each hour—ask for schedule at ticket desk).

The fun continues upstairs, where “Humans and the Environment” illuminates the human body (find out just how long your intestines are, identify and place the organs, and see how various joints work like hinges). In the exercise arena, you can compete against various virtual animals (can you jump as high as a kangaroo or hang like a chimp?). The “Lightzone” illustrates how light travels in waves, lets you try out an old-fashioned (but still impressive) camera obscura, and use prisms and lenses to play a game of “light billiards.” “On the Move” features fascinating hands-on physics demos, including an earthquake simulator, an air cannon, and a tube that lets you harness sound waves to make water vibrate. New exhibits are added (and old ones refreshed) all the time—be sure to pick up the brochure at the entry to understand your options.

Nearby: The Discovery Park surrounding the museum was created when the busy riverfront highway was rerouted into an underground tunnel, creating this delightful people zone. From here you have good views of the modern Holy Cross Bridge (Most Świętokrzyski, from 2000) and the National Stadium, proudly wrapped in the patriotic red and white of the Polish flag. These riverbanks are a popular hangout by day and after dark; in the summer, a stroll along here reveals a world of picnics, family outings, and impromptu parties.

Two short blocks inland from the science center is the architecturally innovative Warsaw University Library (Biblioteka Uniwersytecka w Warszawie, or BUW), with its distinctive oxidized-copper-colored facade decorated with open books from various cultures. The facade is fun to ogle, and the rooftop holds a huge and inviting garden.

This massive skyscraper, dating from the early 1950s, is the tallest building between Frankfurt and Moscow (760 feet with the spire, though several new buildings are threatening to eclipse that peak). While you can ride the lift to its top for a commanding view, the highlight is simply viewing it up close from ground level.

Viewing the Skyscraper: This building was a “gift” from Stalin that the people of Warsaw couldn’t refuse. Varsovians call it “Stalin’s Penis”...using cruder terminology than that. (There are seven such “Stalin Gothic” erections in Moscow.) If it feels like an Art Deco Chicago skyscraper, that’s because the architect was inspired by the years he spent studying and working in Chicago in the 1930s. Because it was to be “Soviet in substance, Polish in style,” Soviet architects toured Poland to absorb local culture before starting the project. Notice the frilly decorative friezes that top each level—evocative of Poland’s many Renaissance buildings (such as Kraków’s Cloth Hall). The clock was added in 1999 as part of the millennium celebrations. Since the end of communism, the younger generation doesn’t mind the structure so much—and some even admit to liking it for the way it enlivens the predictable glass-and-steel skyline springing up around it.