This chapter will cover a number of worked examples of the models that I have produced over the years to demonstrate what can be achieved, in the words of the Railway Modeller, ‘by the average modeller’. I have chosen four models that I have scratch built to provide examples of a special wagon, a van, an open wagon and a flat wagon. The examples are all based on GWR prototypes, as that is the company and period that I model in OO gauge. Notwithstanding that, however, the observations and methods described in the following examples are generally applicable to a wide range of prototypes, scales and gauges.

SCRATCH BUILD 1: A CORDON GAS TANK WAGON

The first example included here for reference is the construction of a Cordon Gas Tank wagon, which was my first attempt at scratch building rolling stock. A short article based on this text was previously published in Railway Modeller (Tisdale 2010a), but a more detailed description of the scratch build process, with accompanying photographs, is provided here for the reader to understand the processes followed in the construction of this wagon.

BACKGROUND RESEARCH

The use of gas lighting in coaching stock led the Great Western Railway to construct a number of special tank wagons specifically to deliver oil and coal gas from the generating plant at Swindon Works to various stations around the GWR system, to allow local replenishment of gas to coaching stock reservoirs. Research shows that there was not one particular prototype example for these wagons, but rather that these wagons were built to various styles and sizes, typically utilizing underframes recycled from decommissioned old wagons and coaches.

At the time of writing the article, I was aware that there were a number of brass kits available in 4mm scale for the larger examples of vehicles of this type. However, at the time that I was considering making the model in 2009 I was not aware of a kit being available to represent one of the smaller examples, as illustrated in Russell (1971: figs 187 and 188). However, later research indicates that a similar prototype example was available as a white metal kit (produced by David Green) and I understand that more recently (in 2014) Falcon Brassworks has listed on their kit list an example of the smaller Cordon Gas Tank wagon.

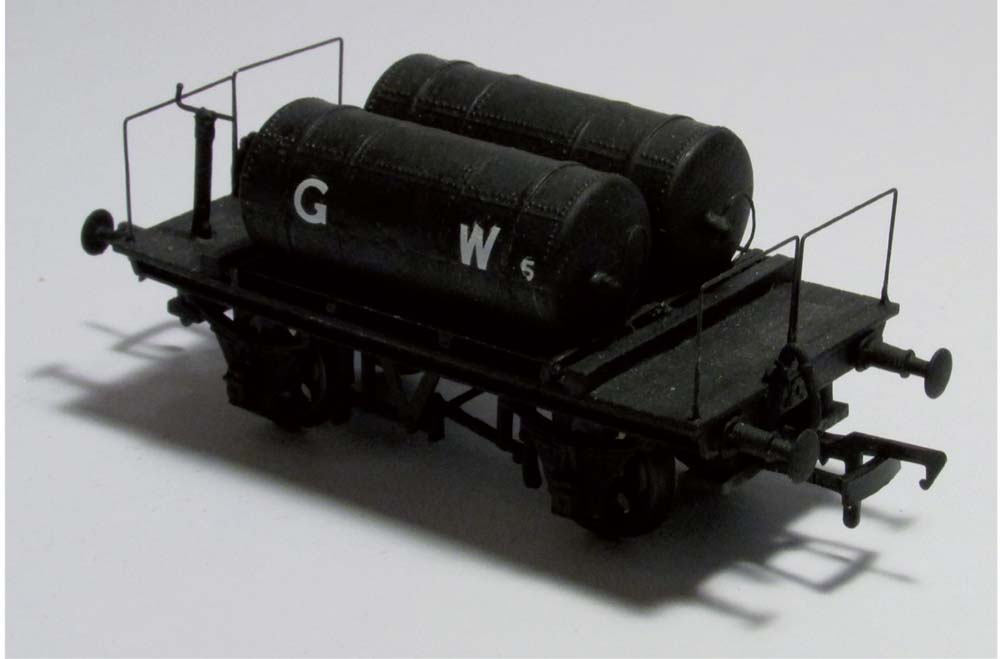

Notwithstanding the availability of brass kits, I decided that I wanted to provide one of these smaller types of special wagon for my own OO gauge branch line layout, ‘Llanfair’, and settled on scratch building a representation of one of the smaller examples, as illustrated in Russell’s book, specifically an example of the wagon that carried two longitudinally aligned gas tanks as shown in Fig. 225.

MATERIALS AND COMPONENTS

Having identified the type of wagon that I wanted to build, the first task was to decide how to build a reasonable model in 4mm scale to represent this part of the everyday life of the railway. This model was my first attempt into the sphere of scratch building, having previously only built kits from the various well-known manufacturers, such as Ian kirk, Parkside Dundas, keyser, Cambrian, Cooper Craft and Ratio; as well as a couple of the Shire Scenes brass side replacements for the Ratio four-wheel coaches and milk wagon, referred to as a Siphon C in the GWR telegraphic code.

I started by attempting to create a reasonable representation of the gas tanks, as these form the main focus of the model. After playing around unsuccessfully with various pieces of card and wood, attempting to obtain a satisfactory tank-like structure to the correct size and proportions, I was not convinced that the end products were acceptable. So I turned to the internet for inspiration and identified, from browsing a number of sites, the N gauge kits produced by PECO, specifically the kit for the 10T tank wagon (PECO ref: KNR-167). A quick comparison of the size of the tank in the kit with the tank on the prototype I wanted to build indicated a favourable fit and two kits were duly purchased.

Fig. 225 A scratch built GWR gas tank wagon to represent an unusual but essential prototype for a branch line railway.

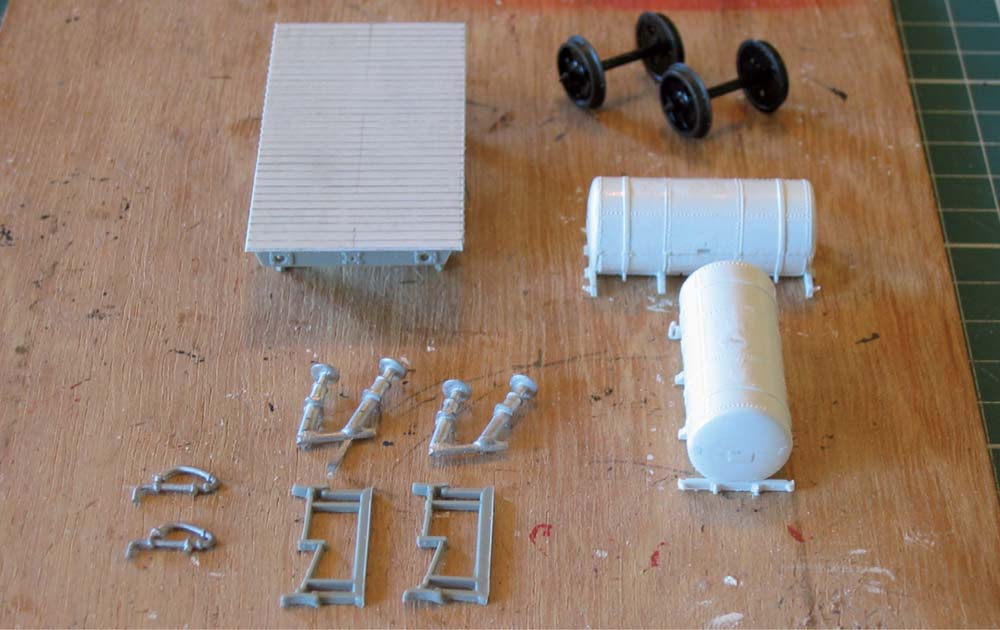

Fig. 226 A collection of suitable parts from the spare-box and two PECO N gauge tank wagon kits to use as the basis for this project.

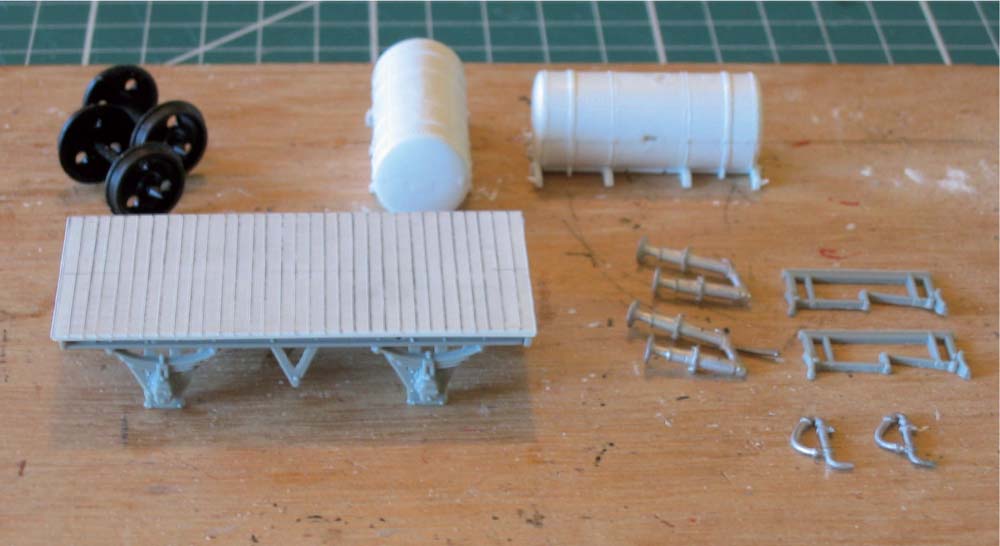

Fig. 227 The underframe assembly comprised suitable waste pieces of plastic card sheet for the floor. The centre-line of the floor and planks were marked on the plasticard with pencil.

The rest of the parts for this scratch building project came from my spares’ box and stock of specialist components. The buffer beams, sole bars, side frames and brake gear were derived from an old Ian Kirk van kit. Although these parts were not to the exact style and dimensions of the prototype, they were close enough – this was a compromise that I was prepared to accept on this first attempt at scratch building.

White metal upright vacuum pipes and standard pattern GWR wagon buffers (ABS or similar products) were used and OO gauge fine-scale 12mm diameter three-hole disc wheels and brass bearings (Gibson or similar) were selected for this model. In addition to these items, various pieces of plastic sheet, plastic rod, scrap white metal and wire were also collected together and used as detailed below.

CONSTRUCTION OF THE SUPERSTRUCTURE

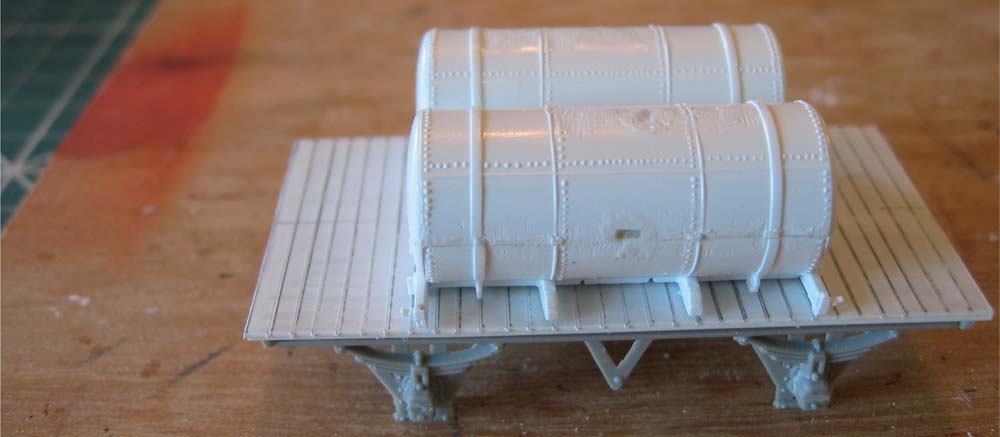

Starting with the gas tanks, I took the N gauge tanks and tension bars from the PECO kits and stored the rest of the parts in my spares’ box for future use (these items were subsequently used to form the basis for scratch built narrow gauge rolling stock for my layout, but that’s another story). The tank bodies were then filled with scrap bits of white metal to provide ballast and then glued together with liquid polystyrene cement, as shown in the instructions for the kit.

Once set, the sides and ends of the tanks were sanded flush along the join line, using fine-grade sandpaper and needle files, taking care not to remove the rivet detail. The various fittings moulded on the upper part of the N gauge tanks were carefully removed with a sharp chisel blade craft knife, to produce a simple rounded-off tank body to match the profile of the prototype. I found that if the parts are carefully removed, the filler cap from the top can be re-used and, in my case, I re-affixed them to one end of each tank, as shown in the accompanying photographs, to represent filling points. The tanks were then put to one side whilst the basic wagon underframe was constructed.

Fig. 228 The modified tanks were positioned using the marked centre-line and counting the number of ‘planks’ from each end to ensure the tanks were evenly spaced.

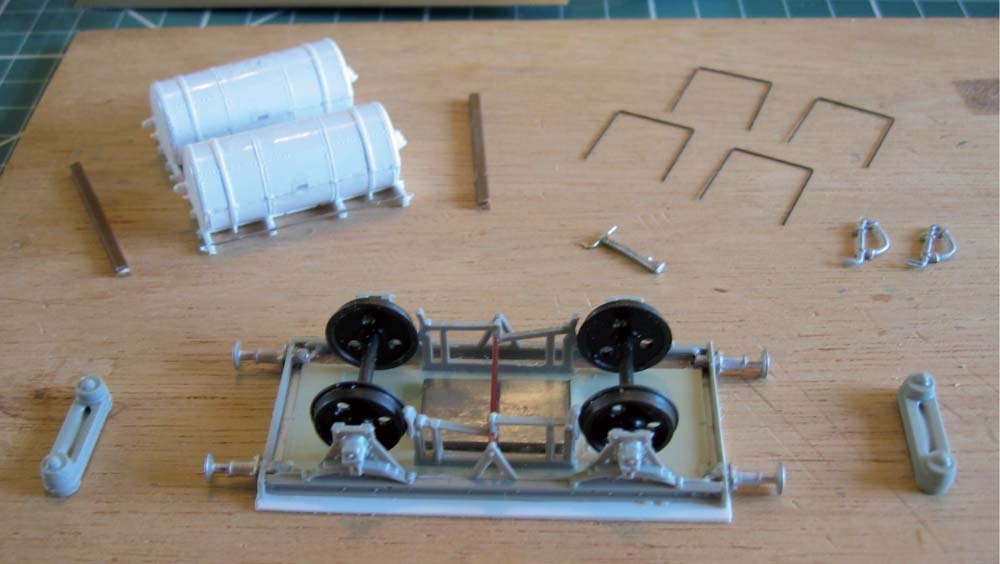

Fig. 229 Steel ballast weights, brake gear and connecting rods were added to the underside to add detail.

CONSTRUCTION OF THE UNDERFRAME

An underframe base was cut, approximately 59mm by 24mm, from scrap 2mm-thick plastic sheet. Mine was formed from waste Wills paving sheets, to which the wagon sole bars and side frames were glued, checking for vertical alignment and correct width for the preferred wheel sets. The width of the underframe base sheet will vary slightly, depending on whether you are using EM, P4 or OO gauge wheel sets. It is important to check the width of base required before you start cutting any materials. As has been noted previously, installing the brass bearings into the axle boxes on the side frames is easier to do before fixing the side frames to the underframe base.

The underframe assembly was put to one side and allowed to dry. In the meantime the wagon floor was prepared. I cut two sheets the same size (64mm by 33mm) from 0.5mm-thick plastic card to form a sub-floor and floor for the wagon. The sub-floor was glued to the underframe assembly, as shown in Fig. 228, along with the buffer beams.

The second sheet, which formed the visible floor of the wagon, was marked with a pencil at 2mm centres, measured from the wagon end, and lined parallel to the wagon end to represent the wooden planking of the floor (as shown in Fig. 228). The pencil lines were then scored with a sharp knife, but being careful not to cut through the sheet completely. The floor section was then glued on top of the sub-floor sheet and the model was then placed on a flat surface (glass tile) to allow the glue to harden off for at least twelve hours.

The buffer beams were then carefully drilled out to accept the ABS white metal buffers and an additional ballast weight (a Cooper Craft wagon weight) was glued to the underside of the under frame (as shown in Fig. 229). Once the ballast was fixed in place, the brake gear was installed, together with the connecting rods formed from 0.75mm diameter plastic rod. The wheels were installed to check free-running before the brake assemblies hardened off.

ASSEMBLY OF THE SUPERSTRUCTURE COMPONENT PARTS

The tanks were fixed to the wagon base with liquid polystyrene cement and checked to ensure that they were squarely aligned with the edges of the wagon floor and that the tanks were not twisted about their central axis, using the join lines in the tank-halves as a guide (see Fig. 230). To form the horizontal tension rods that sit on the outer side of each tank, pieces of 0.5mm wire were cut to length, sitting nicely within the preformed holes that are on the moulded end bar on the tank kit.

Fig. 230 With the tank positions finalized and the end beams in place at each end of the tanks, representation of the horizontal tension rods was added using the holes in the original kit for guidance.

Fig. 231 These types of wagons were considered part of the engineering stock and thus were painted black rather than the standard GWR wagon grey.

The ‘U’ shaped tension rods from the N gauge kit were then subsequently used as handrails on the access platform located at one end of the wagon (see Fig. 231). To install the handrails, I drilled 0.35mm diameter holes in the wagon floor ends to accommodate them, using a spot of cyanoacrylate glue to hold each piece of wire in place. Additional floor bracing beams were formed from scrap plastic sprues and added at each end of the tanks to match the layout indicated in the photographs of the wagon (Russell 1971) and as shown in Fig. 230.

The prototype included a hand-brake stanchion on the access platform at one end of the wagon. To rep- resent this hand brake in model form without buying a bespoke part, I opted to form the stanchion from a piece of scrap white metal, suitably fixed to the wagon floor, as shown on the prototype in Russell (1971: fig. 188). I then took a piece of 0.5mm wire and bent it to shape to form the turning handle, before fixing the handle to the hand-brake stanchion (see Fig. 231).

I formed valves and feeder tubing from waste plastic and fine wire, respectively, with the wire recycled from the wire mesh commonly found on Rioja wine bottles. These were then added to represent the feeder points from each tank, as shown in Figs 231 and 232.

Fig. 232 The fine handrails were formed from the N gauge kit tension rods. The hand-brake stanchion shown on the right-hand side of the model was formed from waste white metal.

FINISHING TOUCHES

Once completed the whole wagon was then painted matt black as per the prototype described in Russell (1971), indicating that the vehicles formed part of the engineering wagon fleet of the railway company. HMRS Pressfix transfers were used to complete the model. Purists I am sure will spot details where compromises have been made, for which I apologize, but the intention was to provide a fair representation of an interesting prototype to run on my layout, rather than a 100 per cent accurate copy of the prototype in 4mm scale.

SCRATCH BUILD 2: A BOGIE GOODS VAN

The next worked example is the scratch building of a GWR Mink F bogie van using a variety of material types and making use of the specialist components aimed at the scratch builder available on the market today. This project is a re-working of a scratch building project idea originally described over thirty years ago in a short article in Model Railway Constructor (Lavey 1984), but using materials and components available today.

INSPIRATION TO BUILD A GWR MINK F VAN

Leafing through some old railway modelling magazines during a sort out of the library at my local model railway club (Jersey Model Railway Club), I came across a long-forgotten article by Mr k Lavey in the October 1984 edition of Model Railway Constructor about scratch building a Great Western Railway Mink F bogie goods wagon in 4mm scale. Lavey (1984) described how he went about this process, with the aid of a sketch of the floor of the model, a reproduction of the official line-drawings and a couple of photographs of the finished model. This set the seed of an idea for a new project to occupy my spare time during the long winter months.

A long time ago, back in the 1970s, when those Hovis adverts were all the rage on the television, you could actually buy a white metal kit of this particular prototype in 4mm scale, which I understand to have been produced by Hobbytime. Being only a child at the time, I obviously lacked the foresight to buy one of these kits and store it until I was old enough to appreciate it! If you are extremely lucky you might be able to pick up an unmade one of these kits on an online internet auction site, but usually at a premium price.

Fig. 233 These bogie goods vans had a 30T capacity and were built for mainline fitted freight services. The GWR bogie Mink F was an iron bodied van, but much larger than the more commonly known four-wheel version represented by the Ratio Models kit.

Having re-read the article and then consulted my own reference books back at home, where I found copies of the official line-drawings and a number of additional photographs of the prototype in Russell (1971) and Atkins et al. (2013), I quite liked the idea of having one of these wagons to run on my layout. However, not wanting to take out a second mortgage to buy one of the old kits from the auction site, I subsequently decided to have a go at scratch building my own version of the wagon.

LIST OF MATERIALS REQUIRED

From my experience building this model, the following parts need to be sourced before starting the construction of the model:

As we have reviewed in Chapter 2, there are a number of tools and adhesives that were required to construct the model. The following, in particular, were found to be most useful:

WHERE TO START

The most obvious starting point initially had been to consider the idea of using the Ratio Iron Mink kit (Ratio ref: 5063) as a basis for conversion to a Mink F. However, as soon as the pieces of the Ratio kit were laid against the line-drawings for the Mink F it became apparent that the bogie goods’ wagon was an altogether much larger vehicle, not just in length, but also the height of the wagon body, as correctly pointed out in the earlier article by Lavey (1984). This difference is also indicated in Fig. 234, which shows for comparison a finished scratch built Mink F van alongside a completed example of the Ratio kit, as described in Chapter 3. With this in mind, I therefore decided to build completely from scratch using a combination of plasticard and brass, with the exception of the wagon bogies, which were a modified Ratio product.

This approach to the scratch building of this wagon utilizes some of the comments noted from the work previously described by Lavey (1984), but I have suggested amendments and alternatives to the earlier method of construction and used different materials for some of the elements to produce my own model version of the GWR Mink F van.

Fig. 234 To give an indication of the significant size difference between the two iron bodied wagons, the four-wheel iron mink is shown on the left compared to the bogie van.

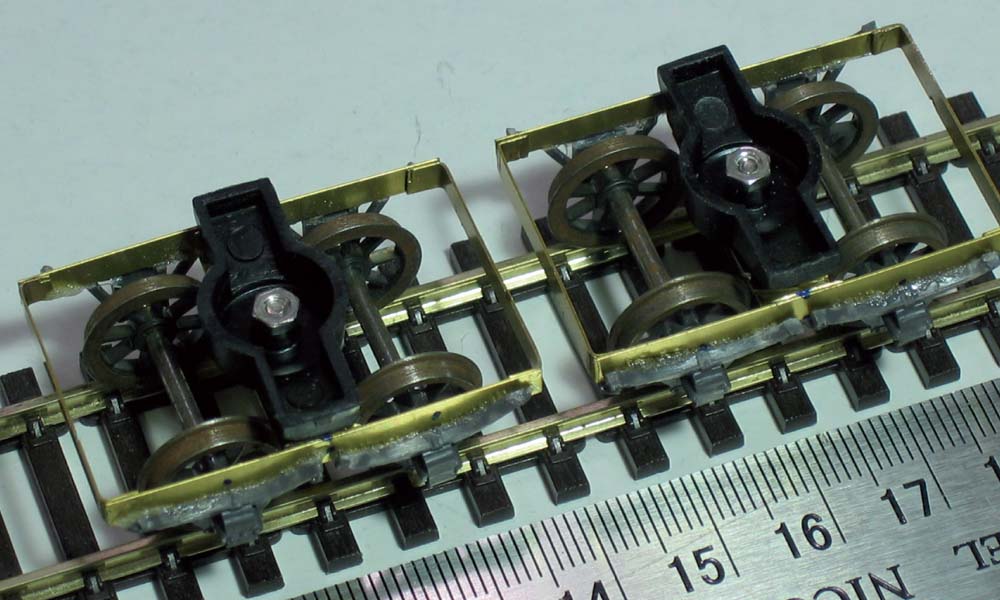

CONSTRUCTING THE BOGIES

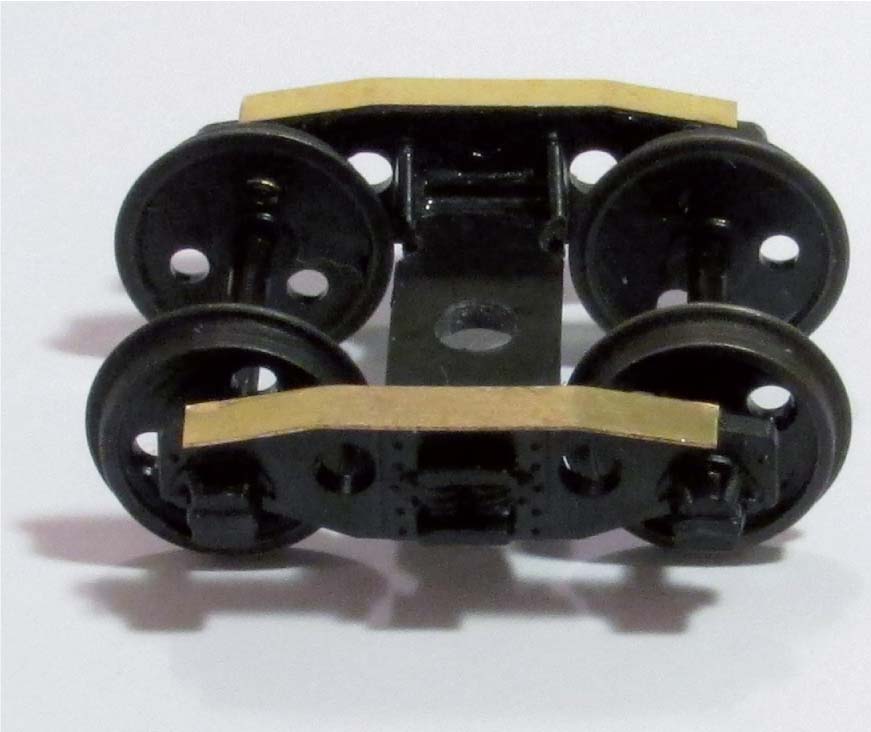

Starting with the bogies, I acquired a Ratio Plate Bogie kit and opted to replace the plastic wheels supplied with the kit with OO fine-scale Gibson three-hole disc wheels running in brass bearings. As with most of these types of kits, I drilled out the axle boxes using a 2mm bit and inserted brass bearings so that the shoulder was flush with the rear face of the axle box. Each bearing was held in place with a tiny spot of super glue applied to the bottom of the drilled out axle box prior to inserting the bearing.

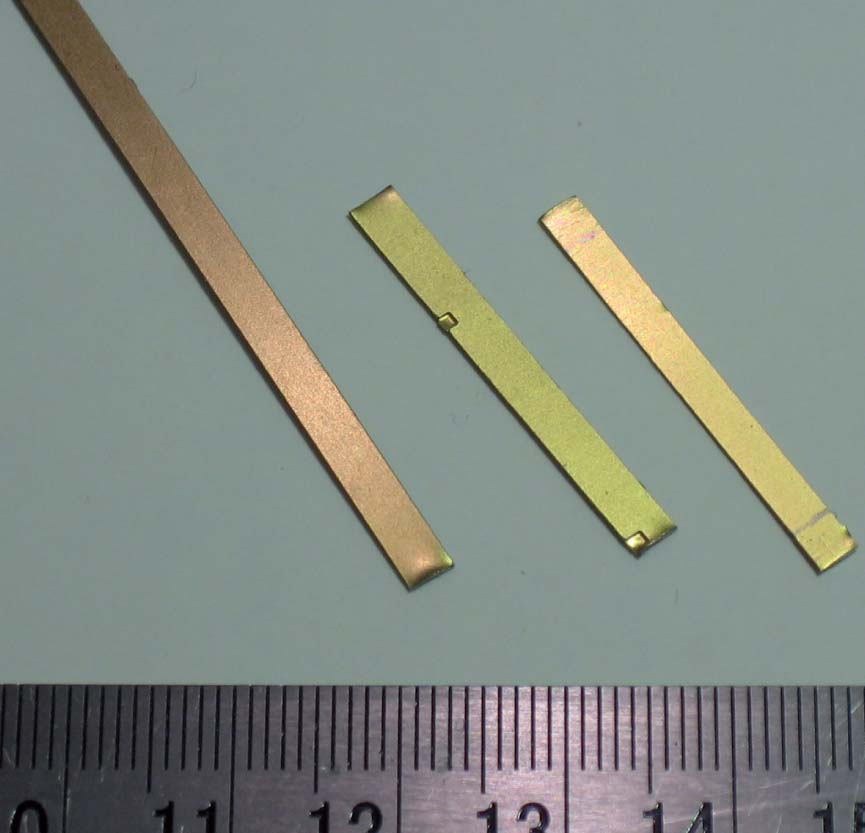

Fig. 235 The Ratio Plate Bogie kit was modified with brass bearings and the addition of brass strips to the top of the plate frames to represent prototype strengtheners.

To recreate the additional bracing applied to the plate wagon bogies used on the Mink F van, I took some 3mm-wide 10thou brass strip and cut to length (approximately 24mm long) a piece for each side frame of the two bogies (see Fig. 235). Then, using a pair of flat-jawed pliers on ‘permanent loan’ from my wife’s jewellery-making toolbox, I gently bent the strip to match the top profile of the bogie side frame. When happy with the profile, I used super glue to fix the brass strip to the plastic side frames so that the strip was flush with the rear edge of the frame but overhung the front edge by about 1mm, as per the prototype example.

Incidentally, the flat-jawed pliers were supplied by Beadsmith, but other makes are available (see Fig. 25). These pliers are specially formed with flat jaw faces and 90-degree edges for jewellery making and as such I have found that they are also ideal for bending and shaping brass components for railway model making! The pair I have now ‘acquired’ appear to be very well-made and come at a reasonable price, at less than a tenner including postage.

In the Ratio kit the bogies are held on the bolster components by a push-in plastic plug. I wanted to be able to remove the bogies in the future for maintenance without the risk of splitting the plastic bolsters in the process, so I decided to use 8BA nuts and bolts, as this size of bolt can be just pushed through the preformed holes in the bolster and is a snug fit. To access the screw head of the bolt with a small screwdriver, a 3mm diameter hole was drilled in the centre of the bogie stretcher before putting the parts together. Once this had been completed, the bogies were then assembled as per the manufacturer’s instructions, with the side frames fixed with liquid polystyrene cement to the stretcher (see Fig. 236). Before the cement had set hard, the wheel sets were installed to check free-running and that the frames were square.

Fig. 236 The standard bogie kit uses a push-in plug to fit the bogies to the wagon. For the construction of this scratch built wagon, the bogies were modified to accept 8BA nut and bolt fixings.

The bolt was fed through a washer, the compensating pivot plate, to which the coupling was later fixed, and then into the bolster. The nut was screwed on and, when happy with the alignment, the bolt was glued to the inside of the bolster with impact adhesive. In addition, some scrap pieces of plasticard were also glued between the nut sides and the inside faces of the bolster to prevent it twisting off in the future.

The sub-assembly of bolt, washer and pivot plate was then inserted into the bogie side frames, as indicated in the instructions, by gently springing open the top of the side frames and dropping the pivot plate pegs into the guide holes on the internal faces of the side frames. On my layout I use tension lock couplings, so I used Bachmann mini-couplings (long type) fixed to the pivot plate in lieu of the ones supplied in the kit. The bogies were then ready for painting.

CONSTRUCTION OF THE WAGON BODY WALLS

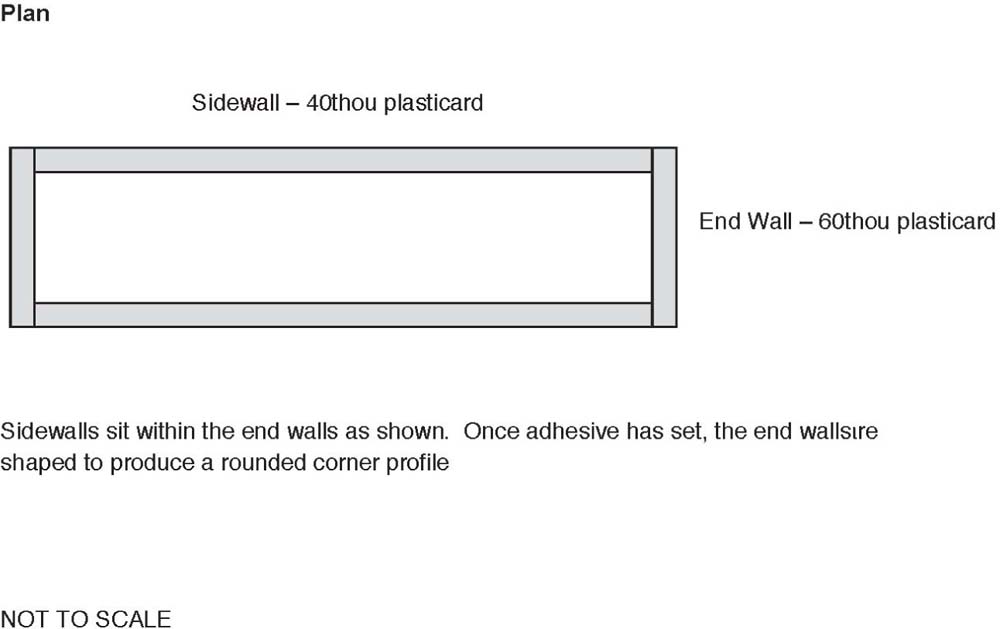

I started with the walls of the wagon and measured out two pieces 140mm long by 27mm high on 40thou plasticard. Once cut out, I laid each sidewall on the line-drawing and using a soft pencil marked on the location of the vertical strapping and doors, as shown in Fig. 237. This makes the fixing of the strapping and building-up the door profiles easier than when the van body is completed.

The profile of the end walls of this wagon were curved in two directions: the curve around the top and the curved vertical corners to join with the sidewalls. This, on the face of it, makes it a difficult profile to replicate. However, taking the advice from the article by Lavey, I opted to use 60thou plasticard as he suggested for the end walls, with the sidewalls butting to the inside edge of the end walls.

To form the end walls I copied the line-drawings, cut them out and stuck them on to the 60thou plasticard sheet by flooding the paper with liquid polystyrene cement and leaving to dry. When dried, I cut out the walls around the line-drawing and then fixed one sidewall to one end wall, with the line-drawing on the inside face of the van and some scrap pieces of plasticard as bracing pieces in the corner towards the top of the sides (see Fig. 238). It is important to note here that the sidewall sits behind the edge of the end wall (see Fig. 239), the reason for which will become apparent when shaping the end wall to match the profile of the prototype.

Fig. 237 The sidewalls were formed from 40thou plasticard sheet and each side was marked to show the location of ’T’ bracing strips and doors. The roof, formed from 5thou brass sheet, was also marked with reference to the line-drawings to show the locations of the raised joints.

Fig. 238 To get the shape of the end wall, the line-drawing was photocopied, cut out and bonded to the end wall before cutting. Each sidewall and end wall sub-assembly was then constructed as a pair and checked to ensure a right-angle corner.

Fig. 239 The sketch shows how the sidewall and end wall butt together at the joint, with the sidewalls fitting inside end walls. This was done to allow the shaping of the end walls as described in detail in the text.

The two sub-assemblies of one end wall and one sidewall were then glued together to form a box and placed on a glass tile to ensure that they were square. When the joints had hardened off, I then used files and fine glass paper to round off the vertical edges of the end walls to get the curved profile of the prototype. This is a slow process and calls for patience to make sure that the end profile looks correct, but when finished it does help recreate the feel of the vehicle prototype if you get the curved profile correct. On the model this has worked well, as once the ends were profiled and vertical strapping added, the join between the ends and sides was all but invisible (see Figs 240 and 241).

Fig. 240 With the two sidewall/end wall sub-assemblies joined together, this completes the box forming the van body. The rounded off corners to the end walls are visible in this figure.

Fig. 241 The end-on view of the wagon shows the curved corners and the end wall marked for the later addition of bracing strips.

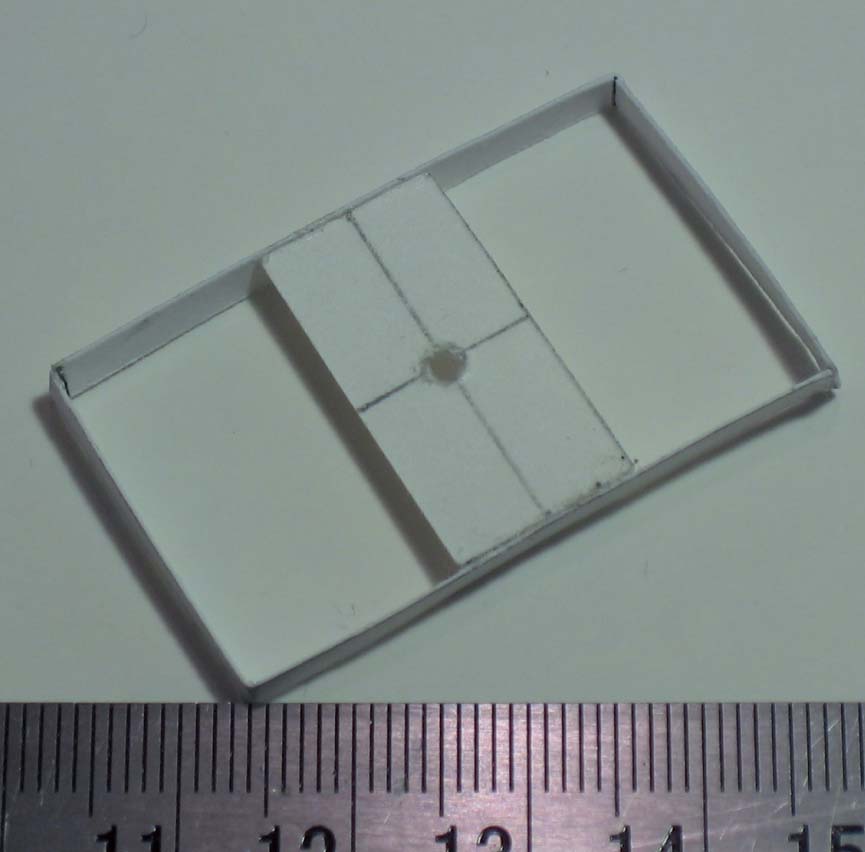

CONSTRUCTION OF THE WAGON BODY FLOOR

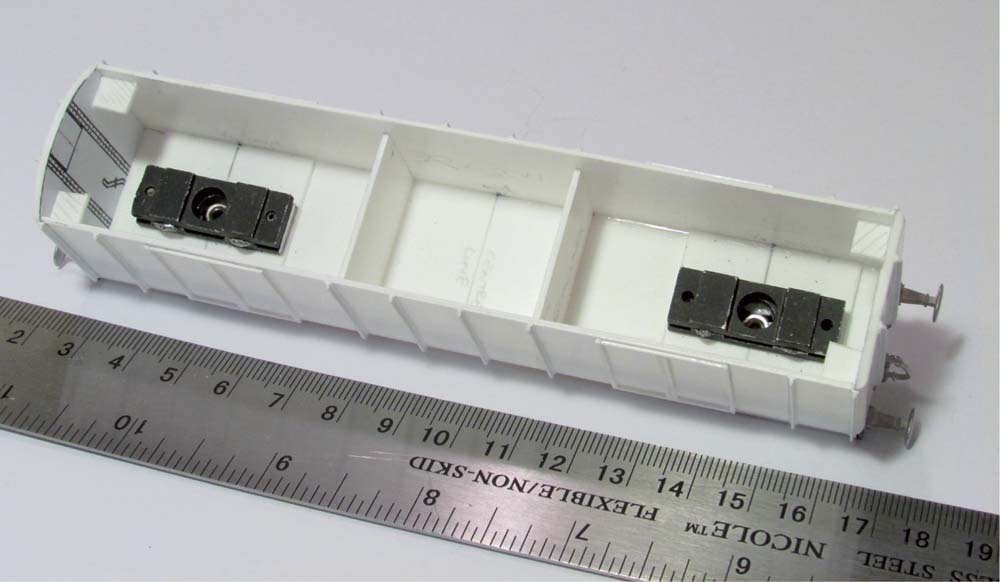

The floor of the wagon was cut out after the walls had been fixed together to form a box, so that I could measure the exact internal dimensions of the hole, as the floor sits within the box formed by the walls and flush with the bottom edge. The floor was formed from 40thou plasticard. The dimensions of the floor were measured from the internal faces of the body sides to give a rectangular section of approximately 140mm by 28.5mm; the exact measurement will depend on how well the body construction has gone together.

To accommodate the bolster fixing blocks from the Ratio bogie kit, the level of the bolster needs to coincide with the upper (inner) surface of the van floor. Therefore, I chose to cut the floor into three sections. The bogie centre-to-centre spacing measured from the scale drawing is approximately 100mm. Therefore, at each end of the van a section approximately 10mm was cut to fit immediately behind the buffer beam. A central section of floor, approximately 80mm in length, was cut and fixed centrally within the hole for the floor. To ensure it was central, the mid-point of the walls was measured and marked on the internal surface and similarly the floor section was also marked at its mid-point and the two marks lined up during fixing.

Additional pieces of plasticard were then cut to fix to the upper surface of the floors, creating a step in the floor at least 30mm long, as shown in Fig. 242. These steps allowed the bolsters to be fixed at the correct height for the bogies to sit below the sole bars (see Fig. 243).

At this stage it was important to consider how the bogies were to be fitted to the completed wagon. As described previously, I chose to fix the bogies with 8BA bolts so that they could be removed for maintenance and to allow separate painting as required. To accomplish this, the position of the bolsters was marked and a 5mm diameter hole was drilled in the raised sections of the floor so that the bolts could penetrate the floor. Alternatively, the bolts could be cut to length to avoid the need for the holes in the floor, but drilling a hole in the floor was deemed to be easier than cutting the bolts.

Fig. 242 To accommodate the bogie fixings and ensure that the wagon rode at the correct height, the floor was formed with cut-outs to accommodate bogie bolster fixing points, as shown in the sketch.

Fig. 243 Bogie bolsters fitted to cut-outs in floor of the completed wagon body. Before fixing these in place it is important to remember to glue the fixing nut inside the bolster first, as described in the text.

Ballast was then added to the wagon by gluing metal weights to the internal surface of the floor, in particular around the location of the bogies to ensure the weights pushed the bogies down on to the track for good adhesion and running, as shown in Fig. 244.

Fig. 244 Internal view of the van during construction showing the additional white metal ballast weight over the bogie fixing point to improve track adhesion.

Fig. 245 The completed wagon internal arrangement, including the internal bracing walls to reduce the risk of future bowing of the plasticard sidewalls.

Once the sections of floor had been fabricated and checked for fit, the parts were then inserted into the walls and checked to see that they sat flush with the bottom edge of the walls. To assist with this, the body was placed on a glass tile. When happy that the body was square and flush fitting, liquid polystyrene cement was fed along the internal joint between the walls and floor, and then the whole body was set aside to dry. Internal strengthening walls were provided within the body to prevent later bowing of the van sides, as shown in Fig. 245.

DETAILING THE WAGON BODY

The prototype had prominent but relatively simple vertical strapping. To represent this on the model, I opted to use extruded plastic pre-formed ‘T’ section (Plastruct), available from model suppliers such as Hobby’s. The vertical strapping was cut to fit each of the lines drawn on to the body sides, as described previously. The strapping was cut slightly over-long and then fixed with liquid cement, checking with a set square to ensure that each piece of strapping was perpendicular to the base of the body. One side of the body was completed at a time and when the strapping had set, each section was trimmed to length with a sharp knife. The top edge of each strap was then filed to shape to match the profile of the end walls and to accommodate the overlap from the roof.

Fig. 246 The prototype carried ‘T’ shaped angle iron bracing to the wagon walls. Pre-formed ‘T’ shape plastic strip available from Plastruct was used to form these bracing strips on the model.

Fig. 247 The pre-formed ‘T’ plastic strip was also added to the marked positions on the end walls. White metal vacuum pipes were also added at this stage.

The vertical strapping on the end walls was added after the buffer beams were affixed, as the strapping extends over the joint between the wall and the buffer beam. Similar to the strapping added to the sidewalls, each part attached to the end was cut slightly over long and then glued in position. Once set, the strapping pieces were trimmed using a sharp craft knife and then filed using fine files to match the profile of the end walls.

On the end walls of the prototype, simple bonnet vents were provided between the vertical strapping. To form these features on the model, I cut pieces of 40thou plastic card to size and then, using a careful slow process of sanding and filing, shaped the plas-ticard into wedge shapes. These wedges were then fixed to the end walls of the van and the top edge filed to match the curvature of the van body end walls, as shown in Fig. 248.

There were two double doors on each side of the wagon prototype and each double door had a heavy frame, with a profile depth matching the ‘T’ strapping. To form this on the model, I chose to use micro-strip to the width of the door frame as marked on the walls, as described earlier. The door frames were built up with successive thicknesses of micro-strip to achieve the profile depth (see Fig. 249). I then used fine micro-strip scrap pieces for the door hinges and fine brass wire recycled from winebottle cages to form the door bolts. Once the detail parts had all set, the whole body was given a coat of spray paint (white) as an undercoat and regulating layer before applying the body colour.

Fig. 248 The bonnet vents on the end walls were formed from a piece of 40thou plasticard sanded to a wedge shape and then the top edge gently filed after fixing to match the profile of the end wall.

Fig. 249 The doors on the prototype were heavy duty. To reproduce this on the model, each door was built up from a number of layers of plastic microstrip cut to length.

CONSTRUCTION OF THE UNDERFRAME AND BRAKE GEAR

The sole bar was formed using ‘U’ section channel-extruded plastic strip, sized to match the size of the sole bar on the scale line-drawings. The channel was not fitted until the buffer beams had been fixed to each end of the body. The buffer beams were recycled from the spare parts’ box and profiled using fine files to match the shape of the buffer beams on the prototype by checking against the line-drawings. Once the buffer beams had been fixed, the sole bar channel was cut to length by offering up the channel to the base and checking that it fitted flush with the back faces of the buffer beams. Pieces 2mm long of the same ‘T’ section Plastruct as used on the van body strapping were cut and fixed into the sole bar channel to represent the continuation of the body strapping to the base of the sole bar, as per the prototype.

The buffer beams were then drilled, as appropriate, to accept white metal RCH-type coupling hooks and GWR square shank, oval head buffers, which were fixed into the correct holes in the buffer beams using contact adhesive. Upright pattern white metal vacuum pipes were added to complete the end detailing.

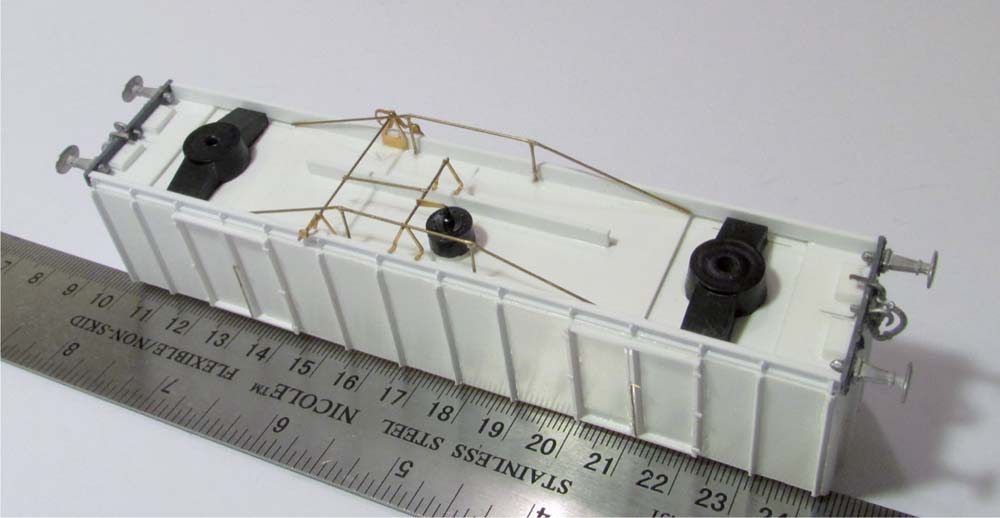

On the basis of the photographic information and line-drawings that I have, the underframe on the prototype comprised a truss frame at each side between the bogies, immediately behind the sole bar. I formed the truss frames from brass wire, using 1mm diameter wire for the queen posts and 0.5m diameter wire for the connecting bars, as shown in Fig. 250.

The four queen posts were cut to about 10mm length and the location of the posts marked on the underside of the floor. Using a miniature Archimedes’ drill and 1mm drill bit, holes were drilled in the floor for each post and then the posts glued into the holes with super glue, so that the posts extended about 6mm below the bottom edge of the sole bar. The connecting horizontal and diagonal bars were formed from individual pieces of 0.5mm brass wire cut to length after the queen posts had been fixed and stuck with super glue, starting with the horizontal bars in the middle and working outwards.

Fig. 250 To get the layout of underframe detailing correct it was marked on the floor of the wagon first. Each section of wire was cut and fixed in place to build up the underframe detail.

Fig. 251 A Mainly Trains etched brass detailing kit was used to supply the ‘V’ hangers and ratchet brake lever.

The DC brake handles, ‘V’ hangers and brackets were taken from Mainly Trains brass detailing frets for DC brake gear (Mainly Trains ref: MT236), with 0.45mm brass wire used to form the connecting rods. I found it easier to mark the layout of the ‘V’ hangers, connecting rods and brackets on the underside of the floor, using a pencil, before starting, so that I had a guide where each component needed to be fixed. I also found it easier to make up the DC brake handles, as well as bend and shape all the other components, before starting assembly, as this seemed to make the construction process easier to complete.

The vacuum brake cylinder was located on the underside of the floor first, off-set from the centreline as per the prototype. I then added a further piece of U-section Plastruct, the same dimension as that used for the sole bars, to provide a central beam under the middle of the floor, parallel with the sole bars. From this the various ‘V’ hangers and connecting rods could be constructed to provide a representation of the brake gear for the wagon.

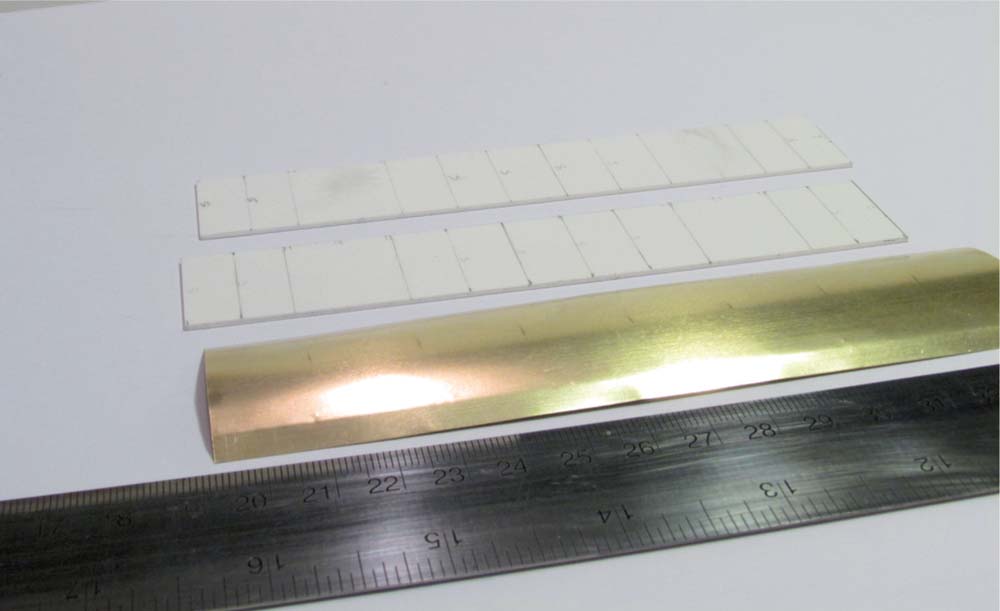

FORMING THE WAGON ROOF

The roof profile on the prototype was relatively fine and was curved to match the end walls, as well as having each corner rounded off. As the body of the model wagon had been constructed predominantly of plasticard, I decided to use sheet brass for the roof. I used kandS 5thou brass sheet, cut 145mm by 36.5mm and then curved to match the end wall profile. The sheet was curved by rolling it gently around a cardboard tube from the centre of a roll of kitchen foil. For best results, the formation of the roof has to be done carefully, a bit at a time, with the rolling repeated until the correct profile is achieved. This process of forming the correct roof profile requires patience, but when completed the overall effect is worth the effort. When finished, the roof was given an undercoat of spray paint.

Even though the roof profile had been formed by rolling, the brass sheet retains some springiness and the curvature of the roof when rolled was slightly larger than the curve of the end wall profile. This was done so that the roof would want to spring up in the centre and reduces the risk that over time it might sag. The roof was fixed to the walls with impact adhesive, after the body had been painted, and was held in place with elastic bands for a period of at least twenty-four hours for the impact adhesive to set hard.

The corners of the roof were rounded off to match the shape of the prototype, using a pair of sharp scissors and fine files to form the basic shape before finishing off with fine glass paper. The strapping detail on the roof was formed using fine microstrip. The microstrip was cut over-long and fixed with contact adhesive. Once set, the strips were trimmed with a sharp craft knife and then the whole roof was painted white.

FINISHING TOUCHES

The body, underframe and bogies of the van were painted all over GWR wagon grey, whilst the roof was painted white, along with the DC brake handles. When dry, HRMS Pressfix transfers were used, using the photographs of the prototypes for guidance on positioning and sizes.

SCRATCH BUILD 3: BUILDING AN OPEN WAGON

The third example of scratch building is the construction of a GWR Tourn wagon. The text is based on an article published in the Railway Modeller in August 2014 but provides a more detailed description.

As is well known, the GWR had a whole list of weird and wonderful names, or telegraph codes to be accurate, for the wagons and vans used on their system. The first question from non-GWR devotees would probably be, so what was a ‘Tourn’? Well it is my understanding that the word ‘tourn’ means either spinning wheel or, in medieval English, refers to the circuit or ‘tour’ that a Sheriff would undertake to administer law and order in the Shires. All interesting stuff but I am not sure what the connection is between these definitions and a piece of railway rolling stock dating from around the end of the nineteenth century. Putting the history lesson to one side, let us now explore how this scratch build project developed.

Fig. 252 The roof for the model was formed from rolled 5thou brass sheet, using the cardboard inner tube from a roll of tin foil as the forming tool.

Fig. 253 After priming the roof and checking the marked positions for the raised strips, microstrip was used to add the detail. Each strip was cut over-long and fixed in place, then trimmed flush once dry.

Fig. 254 The painting is standard GWR wagon livery, with the details of the decals taken from reference photographs of the prototype.

Fig. 255 A one-off bogie open wagon constructed by the GWR presented an unusual prototype to model.

INSPIRATION TO BUILD A TOURN

I stumbled across a line-drawing of this particular bogie open wagon whilst browsing through my copy of Russell (1971), looking for something else, and was intrigued by the unusual nature of the wagon, as it differed from the standard GWR rolling stock. On this basis I decided to try and recreate the wagon in model form for running on my layout. Having decided to create a model, I then set about searching through my collection of un-built kits, hoarded spare parts and pieces looking for inspiration. I came across parts from an old Ratio Bogie Bolster ‘A’ kit (Ratio kit ref: 5062), from which I had used several bits on other things, but which still had the floor sections, sole bars and bolsters to which the bogies are fixed. This provided a basis from which to begin the model and the ideas developed from there.

In terms of this specific piece of GWR rolling stock, and based on my limited knowledge of the subject, it is my understanding that this wagon was a one-off bogie open wagon, intended by the GWR as an experiment and built around the end of the nineteenth century. The line-drawing (Russell 1971) that I used for reference indicated that wagon was 36ft long over the headstocks, with an internal clear loading area of 35ft 7in shown on the line diagram.

The notes with the line-drawing indicated that the wagon was rated to carry a load of up to 25 tons and ran on two short-wheelbase (4ft 10in) four-wheel bogies. Other than being an experiment I am not sure if there was a specific purpose for building the wagon, but I would be happy to know more if anyone has any further information.

Russell (1971) has reproduced a line-drawing of this wagon in appendix 2 of his book, but unfortunately no photograph was included. I have searched through the texts that I had in my small collection of railway texts at home at the time of building this model, but I could not find a photograph in any of them of this prototype and I was unable to locate one following a search on the internet. The absence of a photograph of the prototype made the job of constructing the model a little more challenging and required some lateral thinking to look at the way other wagon prototypes from this period were put together and to use this information as guidance as to how this wagon might have been built.

This scratch building project was, therefore, my interpretation of what this wagon might have looked like, using only the line-drawing for guidance. I built the model to OO gauge, 4mm scale and although not a 100 per cent accurate reproduction, I believe that it is a fair representation of an unusual prototype.

LIST OF MATERIALS REQUIRED

The model was built using a variety of materials, but principally plasticard and brass strip and the leftover bits and pieces from an old plastic kit. To assist the reader, should you wish to have a go at this project yourself, I have compiled the following list of materials that were used in this scratch build project and which you will need to collect together before starting:

Fig. 256 Parts for the sole bars and axle boxes were recycled from the spares’ box.

Fig. 257 Proof of the maxim that ‘it will always come in handy’ – a number of pieces of recycled brass strip waste from previous brass kits could be used for the bogies.

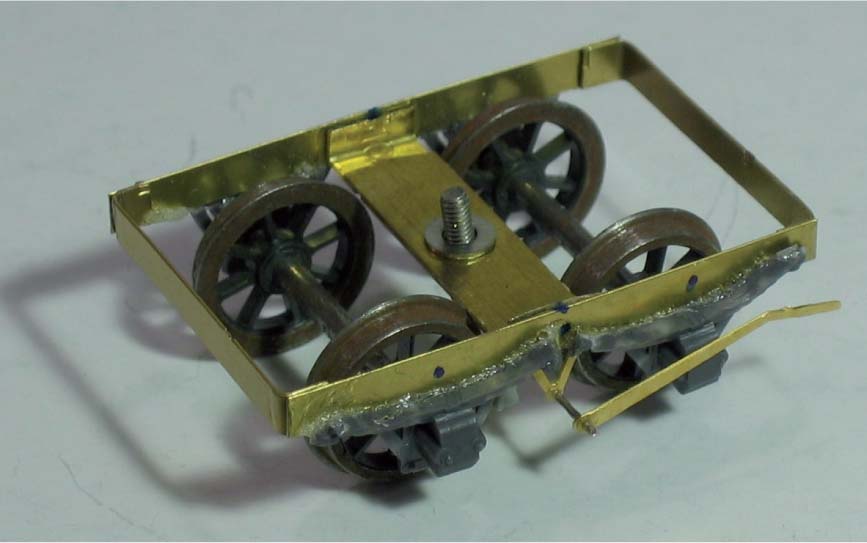

BOGIE CONSTRUCTION

I started with the construction of the wagon bogies. Having studied the line-drawing of the Tourn and lots of photographs of other GWR bogie goods’ wagons, it was apparent that the pattern of bogie used on the Tourn was not a standard GWR goods’ wagon bogie, such as a plate or diamond frame. For some wagons, the GWR used converted old coach underframes and bogies, such as the Bocar wagons, but again the photographs and drawings that I have of these various types did not appear to match the size or pattern of the bogies shown on the line-drawing for the Tourn.

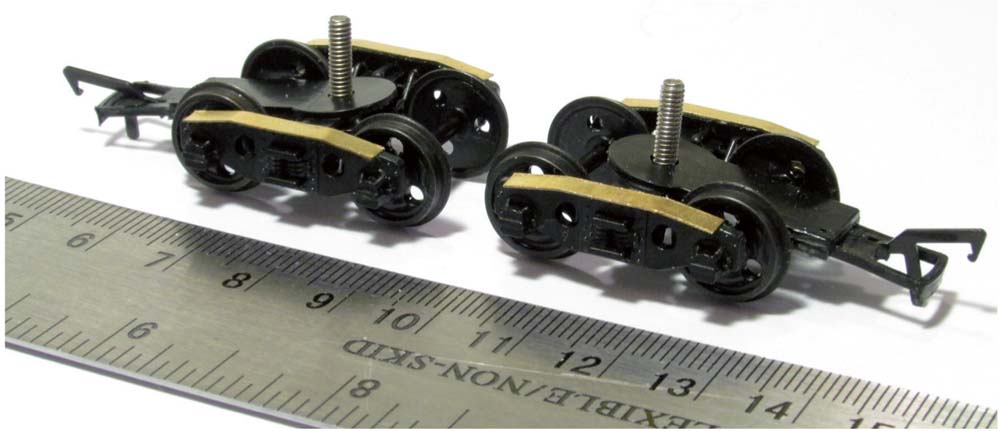

Therefore, without a standard design to copy from a photograph, I decided to scratch build the bogies using brass strip to match the line-drawing. Scaled from the line-drawing, each bogie frame for the model was approximately 39mm long by 24mm wide, with a frame height of about 3mm. Initially, I built a mock-up of the bogie frame sides and stretcher using thin card to get an idea of the dimensions (see Fig. 258) and to work out the best sequence for construction.

Once happy with the general arrangement and sequence of build, I then used a selection of 10thou brass strip recycled from previous etched brass kits, as well as new pieces of strip, to form the frame components (see Fig. 259). Each of the long sides I cut to exactly 39mm. The end pieces I cut to a length of approximately 28mm to allow a fold back tab at each end, on to which I could affix the sides. I then built up the frames one side and one end piece at a time, ensuring that I got a 90-degree corner at each joint. When completed I then joined each sub-assembly together to get the completed rectangular frame for the bogie.

Fig. 258 As the bogie used on the wagon appeared to be a non-standard type, a card mock-up of bogie frame and stretcher was built first to see what it would look like.

Fig. 259 The first attempt at a scratch built bogie with brass strip and a brass plate for the bogie stretcher.

A 10mm-wide section of 10thou brass strip was then cut to form the stretcher, with fold-up tabs at each end. I first tacked this in place with super glue, with the stretcher surface flush with the top edge of the frame (see Fig. 259), but found that this presented the bogie with too much ‘air’ between the bottom of the sole bars and the top of the bogie frame. I therefore separated the stretcher from the frame, inverted it so that the face was flush with the bottom edge of the frames (see Figs 260 and 261) and this proved to be much more acceptable. At the same time, I marked the stretcher with the wheel locations and filed a notch in each location to ensure that it cleared the flanges. A hole was then drilled in the centre of the stretcher to accommodate the fixing nut for the bogie. This whole process was repeated for the second bogie.

Fig. 260 Test-fitting of the prototype bogie revealed that the stretcher was too high. This is the second attempt at the bogie with a lower stretcher, including bolster with fixing bolt.

Fig. 261 The final version of the scratch built bogie with bolsters in place to fix to the floor of the wagon.

Fig. 262 The brake lever detail fabricated from etched brass parts and temporarily fixed to the bogie. These parts are very fragile and best left to the end before fitting to prevent damage during construction.

On the prototype, the axle boxes were at 4ft 10in centres, which equates to approximately 19mm in 4mm scale. To locate the axle boxes accurately on the model, I first marked the centre point of the bogie side frame and then measured out from this the centre-line for each axle box centre-line. The axle boxes that I used on the model were plastic parts from my spares’ box, derived from previous kits. I modified these to match the pattern on the line-drawing by first cutting away the section that would be used to fit to the back of the sole bar. Then I carefully cut the joint between the ‘W’ iron and the spring, and bent the spring upwards while pushing the ‘W’ iron bits inwards at the same time, as shown on the photographs. I then inserted brass bearings and glued them to the bogie frames using the centre-line markings. At this stage, I inserted the wheel sets to ensure that the axles were square and free-running.

Fig. 263 Bogies completed and track tested to ensure smooth running prior to fixing to the wagon. It was necessary to file ‘V’ notches in the stretcher plates to ensure the wheel flanges did not catch.

Fig. 264 The wagon body was built in two sidewall and end wall sub-assemblies to ensure right-angle corners. When set, the sub-assemblies were fixed together.

I assumed that the arrangement for the brake shoes and brake lever was common for both bogies in the construction of this model. Brake shoes were fitted to one side of each bogie, as indicated on the line-drawing, with a lever fitted to the bogie. I used plastic brake shoes cut from spare wagon brake gear assemblies and fixed them directly to the underside of the stretcher and in line with the wheels. The ‘V’ hanger and short brake lever came from a Mainly Trains etched brass wagon brake gear fret. The ‘V’ was modified to fit the bogie and fixed to the underside of the stretcher. A short piece of fine wire was then glued into the connecting rod hole at the base of the ‘V’ to extend far enough out from the side of the bogie, so that the lever, when fixed to the other end of the wire, would stand proud of the axle boxes.

Fitting of the brake gear and lever I found to be quite fiddly and needed plenty of patience to get it square (see Fig. 262). From my experience, it would be advisable to leave attaching the brake gear and brake handle to each bogie until later, as these are quite fragile parts and it would avoid the risk of damaging this fine detail during the construction of the rest of the wagon and testing.

BODY CONSTRUCTION

Moving on to the construction of the body, I took the sole bar sections from the Ratio kit and removed unwanted moulded detail. I then extended the length of each of the sole bars by 15mm at one end, using left-over sole bar sections from another kit. One could use brass section or plasticard to form the sole bar from scratch, but I opted to modify what I already had available. The sides and ends of the wagon body were then built up using 30thou plasticard to the full height of 11mm above the sole bar/ buffer beam, as shown in Fig. 264. I then joined one end and one side together, checking to ensure a square joint, and left them to harden off.

Fig. 265 The wagon floor was formed from pieces of an old bogie flat wagon floor sections from the spares’ box and pieces of plasticard sheet of the same thickness (shown as white in the figure).

The next job was to construct a floor section, which needed to be 144mm long to fit within the body sides. I started with the floor section from the Ratio kit, which was in two halves and with a combined length of 128mm. I removed the moulded pips for the timber bolsters on the upper surface and scribed the floor with planking to match. Using 40thou plasticard, I added a 2mm-wide section between the two halves and a 7mm-wide section at each end to get the correct length (see Fig. 265).

The plasticard was scribed with planking to match the rest of the floor and when the glued sections had hardened off, I shaped the edge profile of the new sections to match the original kit parts. The reason for adding the sections was to retain the bogie locating points on the underside at the correct distance from the buffer beams, to match the prototype, and to ensure that these points were spaced equidistant about the centre-line of the wagon, as shown in Fig. 265.

Once the two side section sub-assemblies had hardened off they were glued together and placed on a glass surface to check that the body was square. The floor was then dropped in from the top and glued in position. Depending on your cutting work to date, this is the opportunity to fill any small gaps between the floor and sidewalls – I know that’s what I had to do!

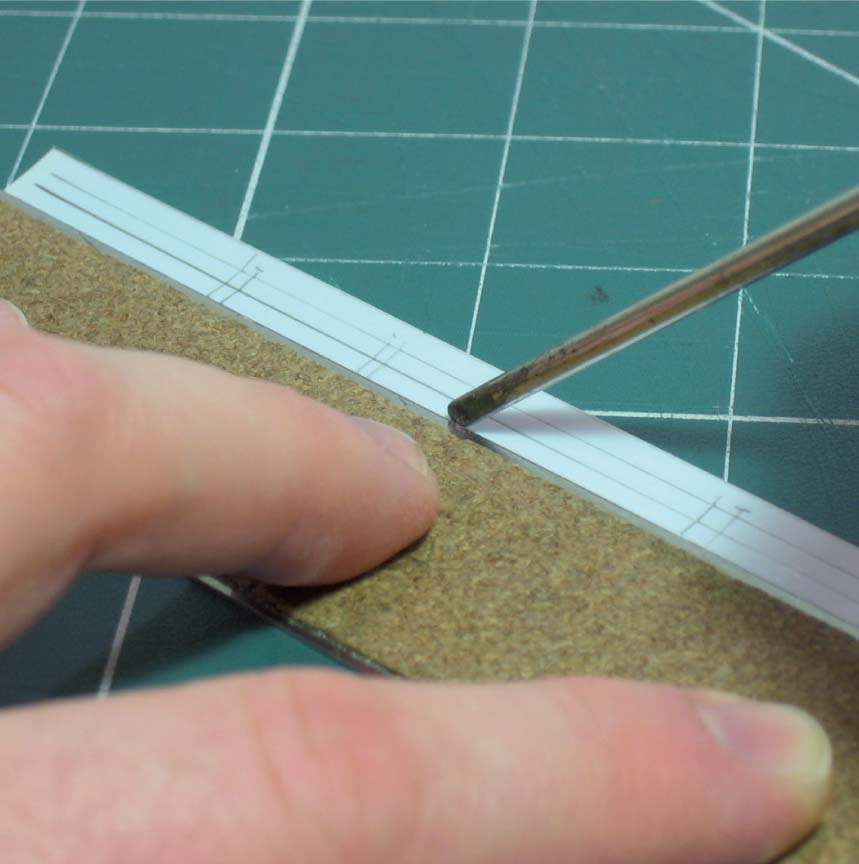

Fig. 266 Overlays for the wagon body were produced using 10thou plasticard. The overlays were scored to represent the wood planking on the wagon.

Fig. 267 Sidewall and end wall overlays were scored and the locations of the doors and strapping detail marked by reference to the line-drawings.

This was the basic body shell completed; now it was time to produce the overlays for each side with the detail scribed on to them. For the overlays I used 10thou plasticard cut to 144mm by 11mm for each of the sides and 31mm by 11mm for each of the ends. As the 10thou plasticard is quite thin, I was able to lay the pieces over the relevant part of the line-drawing and, using a 0.5mm drawing pencil, trace the planking on each piece. I then scored along the pencil lines with a small, old electrician’s screwdriver (see Figs 266, 267 and 268) to provide a representation of the plank and floor detail. The overlay sections were then fixed to the sides of the body shell using liquid polystyrene cement (see Figs 269 and 270).

Fig. 268 Each overlay was lined up against the body to check the fit. The plank detail was not continued to the end of the overlay as this area would be covered by the etched corner plates on the finished model.

Fig. 269 The overlays were fixed in place with liquid polystyrene cement, starting with one sidewall and then working in one direction around the wagon, checking that the planks aligned at the joint.

Fig. 270 With the bodywork completed, the next stage was to add the etched brass detail parts.

The next step was to add white metal GWR wagon buffers and scale coupling hooks to the buffer beams. To fit the buffers, the surface plate detail on the buffer beams was removed with a fine file and the locating holes reamed out with a 2mm diameter drill bit prior to inserting the buffers and fixing with a spot of contact adhesive. The holes for the white metal coupling hooks were opened out with the tip of a craft knife and the hook fitted and glued in the same way as the buffers (see Figs 269 and 270).

The line-drawing showed that there were two drop-down doors, each 5ft wide, on each side of the wagon, spaced equally from each end of the wagon. To represent these on the model, the positions of the two doors were measured and marked on each side; specifically the positions of the vertical strapping and door hinges for each door (see Fig. 271).

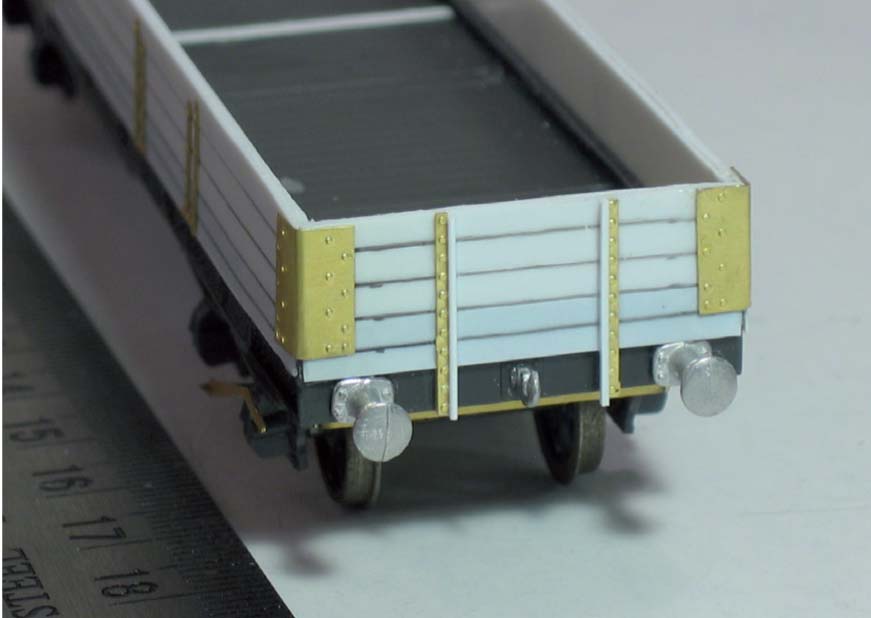

Using a brass wagon detailing kit (Mainly Trains ref: MT164) the length of strapping was measured, cut and fixed, as appropriate, to represent the vertical strapping and hinge details for the doors (see Figs 272 and 273). The riveted brass corner plates for the body were then cut to size from the detailing kit, folded to match the body, then fixed to the body with super glue, as shown in Figs 272 and 273. In addition, brass rivet strip was also cut and fixed to the end walls to match the line-drawing and then microstrip plasticard used to form the angle iron to the riveted strip, as shown in Fig. 274. To provide some additional ballast to the model, wagon weights, unused from previous models, were fixed to the underside of the wagon, as shown in Fig. 275.

Fig. 271 A view of the underside of the wagon body showing bogie fixing lugs. These were positioned to ensure that the bogies were correctly located under the wagon to match the line-drawings.

Fig. 272 Etched brass rivet strip was used for the bracing and door details and corner plates added to hide the join in the overlays.

Fig. 273 A close-up of the rivet strip detail around each door location, including the representation of the door hinge with tiny pieces of brass rivet strip shaped to fit.

Fig. 274 On each end wall the bracing details required the use of brass rivet strip and plastic microstrip to get a good representation of the angle iron detail.

Fig. 275 With the bogie bolster fixed in place, additional steel ballast weights were added around the bogie locations to improve track adhesion of the finished model.

At this stage it was time to fix the bogies to the body shell, to check the height of the bogies and, where necessary, provide packing to get the correct position relative to the sole bar. Once happy with the clearance between sole bar and bogies and the general appearance of the wagon when placed on a section of track, the plastic bogie bolsters were fixed to the underside, having first fixed the holding nut for the bolt to the inside of each bolster using cyanoacrylate adhesive. The bogies were then fixed to bolsters with bolts, using a metal washer as a spacer between brass stretcher and plastic bolster, as shown in Figs 276 and 277.

Fig. 276 A test fit of the bogie, with close up detail showing the single side brake shoes formed from bits of wagon brake gear cut and bent to shape.

Fig. 277 The addition of truss rods formed from more pieces salvaged from the spares’ box completed the scratch built wagon, apart from painting.

The final part of the detail to be added was to form wagon trusses for the underside of the body (see Fig. 277). This could be done using brass wire or plastic rod, as appropriate. However, for this model I found that if the inner truss rods from the Ratio kit were carefully cut down and shaped they proved to be the perfect size and proportions. Once modified these pieces were fixed to the underside of the body immediately behind the sole bar using liquid polystyrene cement.

FINISHING TOUCHES

The model was painted all over in GWR freight wagon grey, with the ends of the brake levers picked out in white. HMRS Pressfix transfers were used to complete the model, as shown in Fig. 278. The layout of the decals was pure guesswork on my part, as I have no picture of the prototype to follow. However, I have based my assumptions of the location of each decal from studying numerous pictures of other GWR wagons to get a feel for how the lettering might have been positioned.

Fig. 278 The layout of the decals is the author’s interpretation based on other wagon prototypes. No photograph of the completed prototype was identified at the time of construction of the model. Since completing the model, however, additional information suggests that the location of some of the decals is not quite accurate. The wagon has not yet been back to the wagon repair shops to be updated.

I am satisfied with the finished model and its general appearance; however, since preparing this work, I have found a picture of the prototype in Atkins et al. (2013) and my interpretation of what the bogies looked like was not too unreasonable, although the layout of the decals on my model was less accurate.

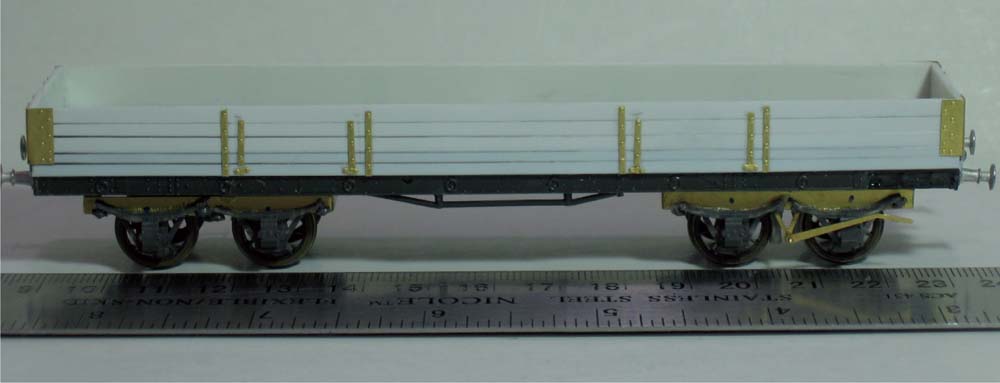

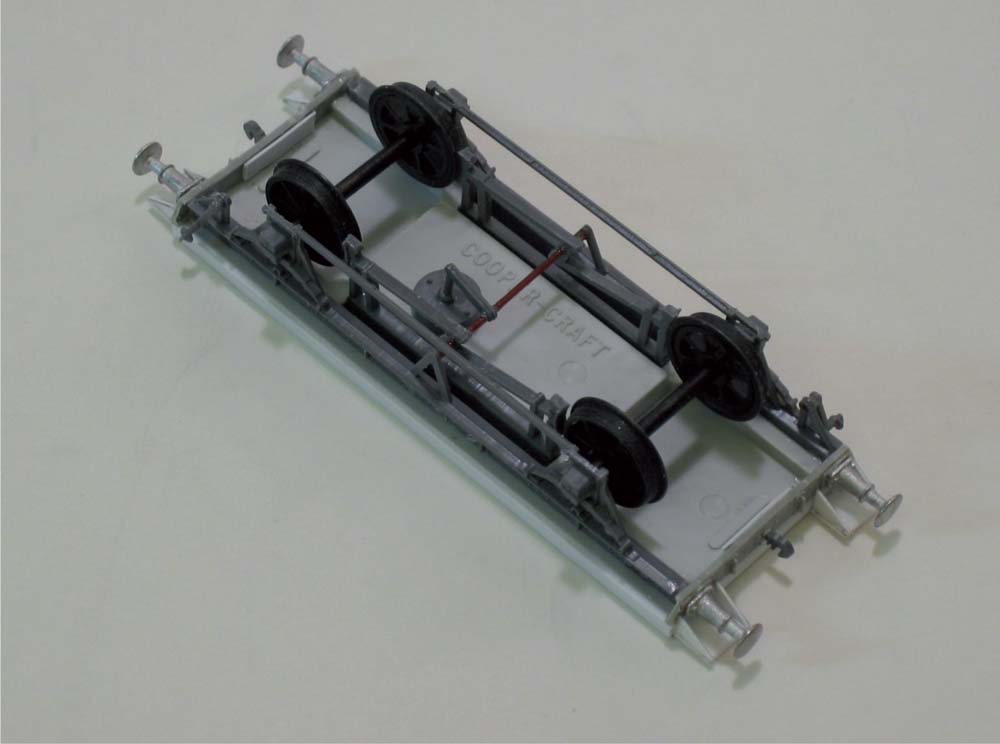

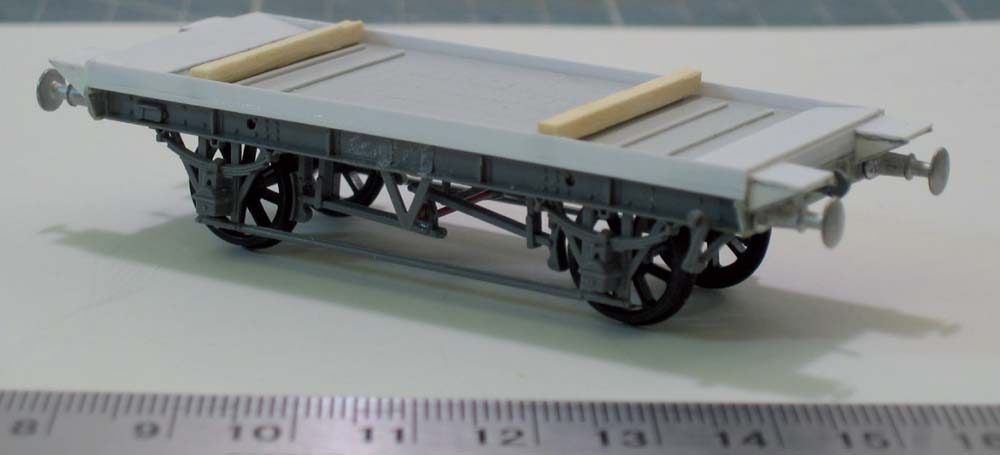

SCRATCH BUILD 4: CREATING AN OPEN CARRIAGE FLAT WAGON

The question as to what to do with the parts left over from the small MEX conversion of the Cooper Craft W1/W5 cattle wagon kit (described in Chapter 5) was the inspiration behind this scratch building project. I was considering what to do with them, whilst browsing through my copy of Russell (1971) when I came across the Serpent family of vehicles with an 11ft wheelbase, specifically the vacuum fitted Serpent C (post-1943 referred to as CARFIT). This looked like a useful addition to my fleet of wagons, so I set about checking dimensions and identifying what spare pieces I had to hand.

LIST OF MATERIALS REQUIRED

The parts required for this project included the floor, sole bars, break gear and vacuum cylinder left over from the cattle wagon kit. However, for those wishing to reproduce this model but do not have these parts lying around, an alternative source would be the Cooper Craft 11ft wheelbase underframe kit (Cooper Craft ref: 1013). In addition, the following items were sourced before commencing work on the project:

Fig. 279 A simple open flat wagon produced by the GWR and referred to as an open carriage truck, shown with a covered car load.

Fig. 280 After completing the conversion of the cattle wagons described in Chapter 5, there were a number of parts left over.

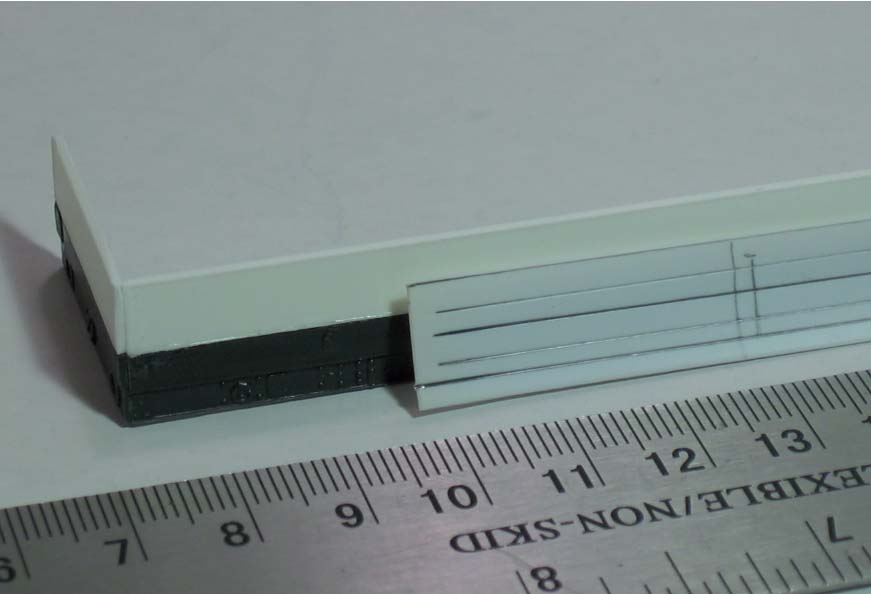

Fig. 281 The underframe and wagon floor were constructed and the wagon floor modified with the removal of the longitudinal ridges from the middle of the floor.

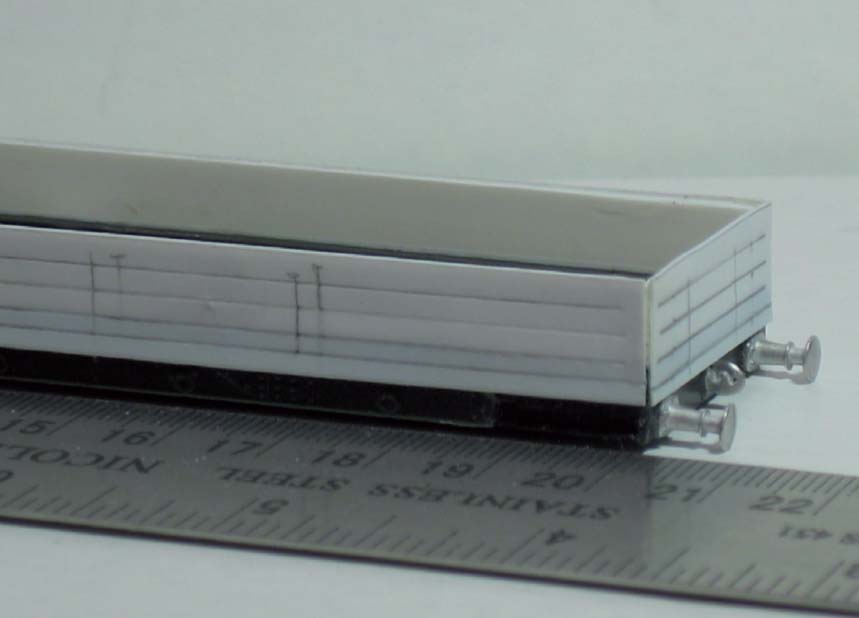

Fig. 282 Brass bearings were added for the replacement wheels and brake gear fixed in place ensuring alignment with the wheels.

CONSTRUCTION OF UNDERFRAME

Starting with the floor of the cattle wagon, the first action was to remove the longitudinal raised strips in the middle of the floor section, using sandpaper/fine file, and then to re-scribe the floor planking. I chose to retain the raised strips at each end of the floor that are parallel with the planking, but if preferred these can also be removed.

The next step was to take the sole bars and remove the two raised vertical mouldings (above the ‘V’ hanger) in the centre of each bar that are used to support the door stops on the cattle wagon kit, as these were not required on this wagon. Then the axle boxes were drilled out as required with a 2mm diameter bit to ensure a flush fit of the brass bearings. Once happy with the sole bars, these were glued to the floor section and the wheel sets installed to check that they ran freely and that the sole bars were square and vertical.

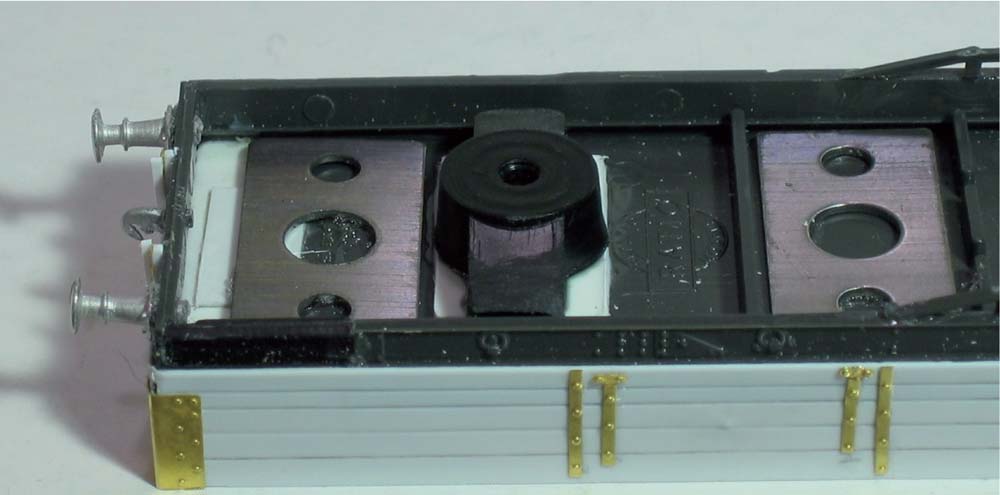

The ballast weight was glued into the recess on the underside of the floor (as per the kit instructions) and then the vacuum cylinder and brake gear added, again checking with the wheels to ensure free-running. The brake rod connections between the vacuum cylinder and the brake gear were then formed from plastic rod. I chose not to reproduce the rod connections to the brake lever at each end of the wagon as my choice of tension lock coupling and mounting block would not leave sufficient space to accommodate the rods. If you choose to use three-link couplings, then the rods could be added. The whole underframe was then left to harden off whilst the buffer beams were prepared.

Fig. 283 The buffer beams were fabricated from spare parts with white metal buffers.

Fig. 284 Underframe detail comprised a vacuum cylinder and connecting rods. One of the unique features of this type of wagon was buffer cover plates for vehicle loading. On the model these were fabricated from plasticard.

The buffer beams used in this model were from my spares’ box (see Fig. 283). I am not sure where they originated from, but they were plastic and of the correct pattern for use on this model, so that was deemed to be good enough. The ends of the buffer beams were trimmed to an angle of 45 degrees to match the profile on the prototype, as shown in the accompanying photographs.

The buffer mounting plate details on the buffer beams were removed with a fine file and then the holes drilled out with a 2mm bit to accept the buffers. I used ABS white metal GWR pre-Group wagon buffers, which required very little cleaning up straight from the packet. Coupling hooks from the cattle wagon kit were also installed at this stage. Once completed the buffer beams were then affixed to the ends of the wagon floors and alignment checked with the sole bars and floor to ensure all was square. I find the use of a glass tile an excellent aid in checking that everything is level and square.

When the underframe section had hardened off, I then started the construction of the sides and ends using square-section plastic microstrip as the first layer all the way round the floor section. Then on each end I added a further two layers of the square-section microstrip (see Fig. 285). On the sides I used 2mm-wide microstrip glued along its edge on top of the square section, giving a side height of approximately 3mm. I then used plasticard to form the ramps on each end of the wagon and to form the plates and support brackets over each buffer as shown in the accompanying photographs. Hanging vacuum pipes were then added using ABS white metal examples, cut from the sprue and carefully bent to shape to match the prototype.

The prototype photographs show that each wagon was equipped with two wooden wheel chocking beams and a selection of chains and/or ropes to secure the loads on the wagons. To reproduce these elements of the prototype in 4mm scale, I decided to make use of a couple of standard matchsticks for the beams. At approximately 2mm square these are a fair representation of the wooden beams, so I cut the head off each match and trimmed to length to fit snugly between the side beams of the wagon. I used fine chain to represent the load anchoring equipment.

The whole wagon was painted in GWR wagon grey and the brake lever handles picked out in white, as well as the marker line on the sole bar for the centre-line of the wagon. The wooden wheel chocking beams were painted chocolate brown and then weathered to represent well-seasoned and aged timbers.

HMRS Pressfix transfers were added to complete the model and you will see that I have used the ‘Serpent.C’ telegraph code to represent a pre-1943 model, as shown in Fig. 287. Those familiar with the HMRS sheets will know that this code is not reproduced ready formed and has to be made up by the cutting of individual letters from other codes reproduced on the sheet. For later (post-1943) models this would read ‘CARFIT’, as per the photographs in Russell (1971) and shown in Fig. 288.

Fig. 285 The upper body sides to the wagon were minimal and on the model fabricated from microstrip.

Fig. 286 Ramps were formed from more plasticard sheet and the wooden chocking beams were formed from matches with the heads removed.

Fig. 287 The standard GWR freight livery applied and load chains added. In this figure the wagon has been fitted with decals depicting a pre-1943 livery as ‘Serpent C’.

Fig. 288 The same wagon could also be updated using alternative decals to a post-1943 livery as ‘CARFIT’.

I believe the model is a fair representation in 4mm scale of this prototype using the parts I had available, but I accept it is not a 100 per cent accurate reproduction and there were some compromises in order to get the overall look of the wagon in model form. I am extremely pleased with the result and I hope that these notes and the accompanying photographs provide a useful guide to the production of a model of this prototype, something that is not (to my knowledge) available in RTR and which can be reproduced relatively easily and quickly from commercially available parts, bits of plasticard and microstrip and a couple of matchsticks!

Fig. 289 A slight variation on the theme of scratch building here with a Slater’s Plastikard private owner wagon with ‘scratch’ livery and lettering to represent a private owner wagon local to the area of my layout. Lettering was made up using HMRS Pressfix sheets.

OTHER EXAMPLES OF SCRATCH BUILD PROJECTS

Another example of rolling stock that I have built, which could be loosely called scratch building, is to use a standard available wagon kit and to reproduce a private owner wagon livery local to the area in which my model layout is generally set. The wagon shown in Fig. 289 is an example using a Slater’s unbranded private owner wagon kit, to which I have applied the livery of John Lloyd Peate and Sons. The wagon livery is based on the livery shown on one of their narrow gauge wagons running on the Welshpool and Llanfair Light Railway (Cartwright and Russell 1981), but I understand that they also ran standard gauge wagons in a similar livery style.

I have not confined my scratch building projects to OO gauge rolling stock and have over the years constructed bridges and buildings (see Figs 290 and 291), as well as narrow gauge rolling stock for my layout, which is in part dual gauge. The narrow gauge rolling stock has been built using parts from Ratio four-wheel coach kits for the passenger stock, whilst all of the freight stock has been scratch built using good quality card, specifically recycled business cards, running on PECO N gauge chassis kits (see Fig. 292). I have also scratch built narrow gauge locomotives and railcars using plasticard bodies running on commercially available RTR N gauge chassis, as shown in Fig. 293. All of these have been built using the skills initially developed from OO gauge rolling stock construction.

Fig. 290 Scratch building for your model railway layout need not be confined to the rolling stock. This example is a factory office built from Wills embossed plasticard sheets, suitably painted, detailed and weathered.

Fig. 291 This scratch built stone warehouse was formed from Slater’s Plastikard embossed stone and roof slate sheets. A full-size mock-up of this building was produced first in plain card to get the wall and roof angles right. The doors and windows are leftovers from Ratio and Wills kits.

Fig. 292 As well as the standard gauge rolling stock, examples from the author’s layout also include scratch built narrow gauge (OO9) wagon and van rolling stock formed from card bodies on PECO N gauge wagon chassis.

Fig. 293 The narrow gauge rolling stock also includes a scratch built freelance steam railcar running on N gauge Tomix Bo-Bo chassis. The body is entirely made from plasticard with staples for the hand rails.

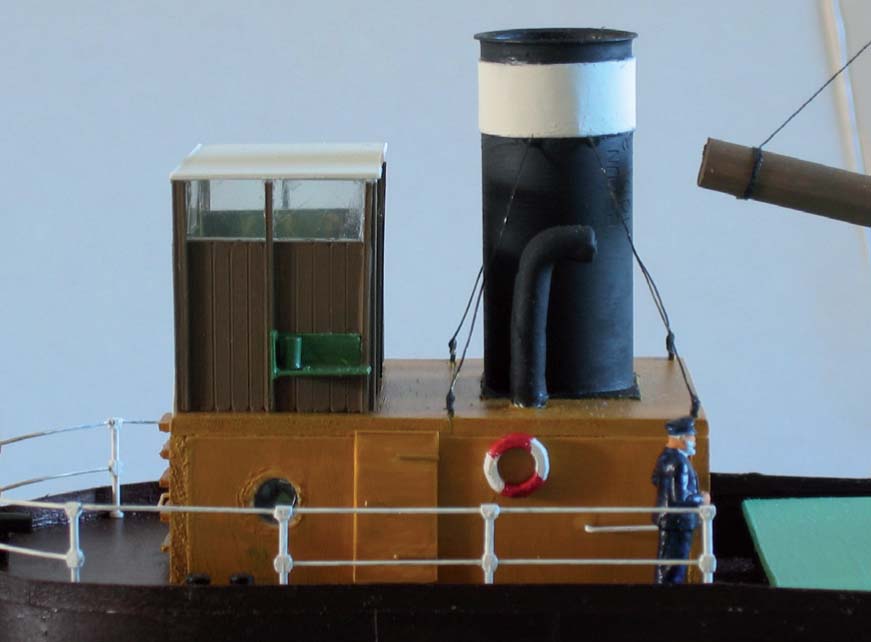

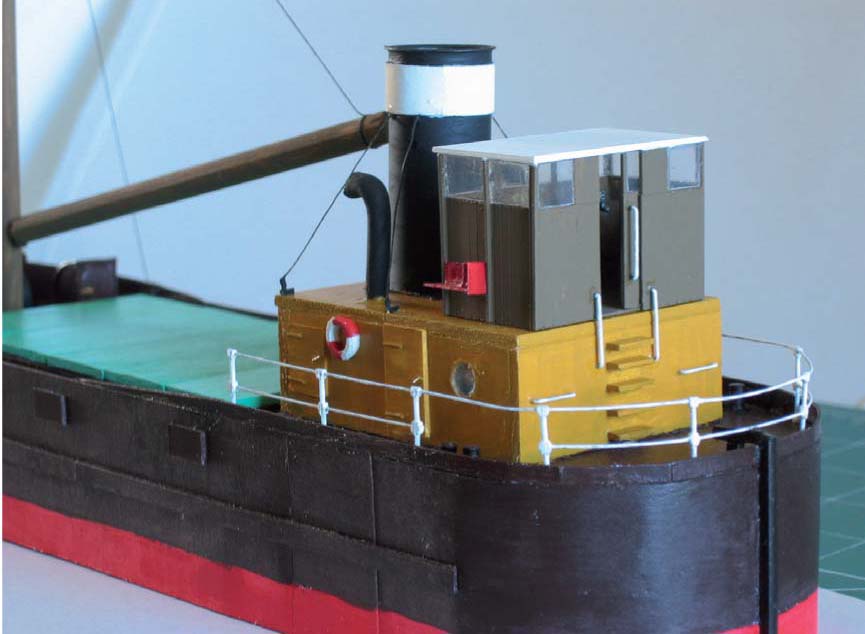

Fig. 294 On a nautical theme, the author’s scratch building skills have also been put to use to provide a small ship for a colleague’s layout. In this case the ship is loosely based on a Scottish ‘Puffer’ and is shown moored at the quayside with the hatch cover removed and awaiting loading.

In addition to the railway prototypes described above, I have also completed a scratch built model of a small cargo ship to 4mm scale, loosely based on a Scottish Puffer, for the harbour on a friend’s extensive OO gauge layout (see Fig. 294). The model ship was constructed as a water-line model to sit against a quayside. The base of the ship was formed from a sheet of 2mm plywood shaped to the correct profile section through the ship. The hull and upper deck was subsequently formed from laminated layers of card, with internal cross bracing bulk heads in the hull to provide strength, just like a real ship.

A cargo hold with removable covers was provided using thin balsawood for the hatch edge and covers. The accommodation block and wheel house at the stern was also constructed from the same material (see Fig. 295). The mast was formed from a thin dowel rod, with thin wire to represent the rigging, whilst the funnel was formed from a cut down metal tube from an old set of hair curling tongs that happened to be just the right size (see Fig. 296).

The only ready-made items used on the model were the plastic railings around the deck at the stern (from a Ratio kit), the fine chain for the anchor and the white metal crew figures from Dart Castings. As you can appreciate from the examples described here, the opportunity to utilize your scratch building modelling skills need not be limited to just the rolling stock for your layout. The skills are transferrable to scenic development, as well as other scales, gauges and subjects.

Fig. 295 The wheelhouse is formed from a combination of balsa wood and plasticard (including the life buoy!), whilst the funnel was originally the inside tube from a pair of curling tongs! The Captain is a painted Dart Casting’s figure.

Fig. 296 A stern view of the Puffer showing the laminated card hull rudder gear. The hand rails are a propriety item from the Ratio Models’ range, suitably adapted for the maritime location.