INTRODUCTION

Before we delve into the detail of kit building and scratch building rolling stock, I will provide a quick review and summary of the types of kits, materials and tools that are available today for the railway modeller to use. This subject has been covered many times before by others, so I plan to provide a brief summary and comments based on my own experience that will be of use to others starting out in this area.

I have found that the quality of kits and components can be extremely variable, and this is not always related to the cost of the items purchased. The production of kits and components for the railway modeller is an area of significant business, covering all the more common and less common railway companies, and through the pre-grouping, grouping, nationalization and privatization periods of British railway heritage.

I have not prepared an exhaustive list of suppliers of kits and components, as that would take a book in its own right; suffice to say that there are many suppliers producing all manner of products to assist the modeller looking to build kits, modify RTR and kit built rolling stock or even scratch building. I have included a short list of the suppliers that I have used in my work in Appendix II, but I must emphasize that I have no connection to any of the suppliers listed, other than as a satisfied customer.

The best advice that I could provide to a beginner starting out would be to carry out some research on your prototype period, company and/or region, and then search the modelling press and internet, and visit railway exhibitions where traders are present, to see what is on offer, decide on what you need and, most importantly, what you can afford.

You might also wish to consider what you can fabricate from raw materials or adapt from spare parts from other kits. This depends on the level of accuracy of fine detail that you wish to achieve, but it is perfectly possible to create many components yourself using basic tools. There is no right or wrong answer, it is what you feel comfortable with and what you have time to achieve (remember life is short!). Set out to achieve a realistic impression at moderate cost rather than set standards so high that you might be unable to attain them first time out. You can improve your skill levels and raise your standard with experience.

Fig. 8 For the beginner wanting to build wagon and van kits, a simple plastic kit, such as one from the selection shown, is a good place to start.

Fig. 9 Tackling a more complicated plastic kit, such as one of those shown here, provides more of a challenge to the budding rolling stock modeller.

As a modeller you need to build up your skill levels and confidence, starting with more straightforward or simpler kits (see Fig. 8), then move to more complicated kits (see Fig. 9) as you develop your skills and confidence in your ability. It is important to remember when building a kit that you can always add more detail at a later date, if and when your skills or requirements for accuracy of finer detail have increased; you could see this as a future upgrade, a bit like the software and hardware for a home PC.

KITS AND MATERIALS

Beginning with kit types, the following provides a summary guide to the most common types of kits available, together with some comments based on my experiences of working with the material types employed.

PLASTIC

This medium is by far the most common material type used for model kit production at the present time. Typically this is extruded plastic derived using moulds to produce a range of parts and components to construct with liquid polystyrene cement. Plastic is a more forgiving material type to use than some materials, especially for the beginner, as it is relatively simple to correct mistakes or to fabricate a replacement part should anything untoward happen during the construction process.

These types of kits can be produced relatively cheaply, as compared to an etched brass kit, and consequently the price of these types of kits is less. The level of detail on early plastic kits was limited, but the more recent kits available from the likes of Parkside Dundas and Cambrian Models, to name but two suppliers, are significantly improved on earlier examples (see Fig. 11). The level of fine detail on many of the plastic kits available today is excellent and I find plastic kits are easy to work with and, having built many plastic model tanks, boats and aircraft kits as a child, it is the material I am most comfortable using and this is probably my favourite material type for building.

Fig. 10 Examples of basic plastic wagon and van kits such as these provide a useful source of kits for the modeller to develop model building skills.

Fig. 11 The kits shown here are examples of more complicated plastic kits available to the model rolling stock builder and require more advanced model building skills.

Fig. 12 Pre-printed wagon kits, such as the Ratio van kit, allow the modeller to provide examples of private owner rolling stock for their layout that may not be available RTR.

Fig. 13 The Slater’s Plastikard range of pre-coloured open wagons, such as this coal wagon kit, is unfortunately only available second-hand at the time of writing.

An advantage of using plastic is that this can be produced in a variety of pre-coloured parts to help with the construction sequence or to represent colour schemes of the prototypes being modelled. One example of this type of flexibility is the older kits produced by Ratio, which unfortunately are no longer available new but it is possible to pick them up second-hand, to represent specific company brands, such as the Harvey’s Bristol Cream wagon (see Fig. 12); a 10-ton van produced in company colours and pre-printed sides with the company branding.

Slater’s OO gauge wagons, now produced under the Cooper Craft banner, also adopted a similar approach to the production of private owner wagons with pre-coloured body and printed sides for the company being represented (see Fig. 13). These wagon kits are relatively easy to make and with pre-coloured and printed sides mean that the keen modeller can have a train of private owner wagons built and running on the layout in a relatively short period of time, without worrying about identifying and applying the somewhat complicated liveries and branding used by some private organizations.

On the negative side, the one big disadvantage of using plastic is that the kits tend to be extremely light and, for good track adhesion and running, ballast will have to be added to all the models. To address the lightweight nature of plastic kits, some kit manufactures provide ballast weights with the kits, but some do not. I have always added ballast, whether provided or not, using a combination of steel weights, white metal and even nails as ballast in wagons.

In vans or covered wagons this is easy to hide within the body. In open wagons this can be a little trickier, but some ballast can be hidden under the floor and some disguised and added in the form of wagon loads – you just have to use your imagination.

Many of the older plastic kits were also produced with plastic wheels; for example, the early keyser plastic kits and early Cooper Craft kits. The use of plastic wheels only exacerbated the poor running problems of a lightweight body. The keyser kits are no longer in production and the Cooper Craft kits have been upgraded and are now sold with metal wheel sets running in brass bearings. I have always fitted metal wheel sets to my kit-built wagons, typically using keen Maygib, Romford or Alan Gibson fine-scale wheel sets running in brass bearings. It is relatively simple to adapt your wagon kit to take metal wheel sets; this will be discussed further in Chapters 3 and 4.

The cost of plastic kits, starting at around £7 for the more basic, simple wagon kit, is the ideal starting point for the beginner. My advice would be to consider plastic kits as a place to cut your teeth at kit building. Start with a simple four-wheel open wagon or box van; for example, the kits produced by Cooper Craft for Great Western rolling stock. These kits comprise only a few main components; a selection of detailed pieces and the new versions of the kits include a set of metal wheels and brass bearings to provide good running. Once you have mastered this type of kit, then graduate to the more complicated plastic kits and then the metal kits; this is discussed further in Chapter 3.

Fig. 14 A simple white metal kit of a Cambrian Railway’s slate wagon produced by 51L, is a good example of the type of kit available in this medium.

WHITE METAL

The use of white metal for producing kits was once more common, but has been replaced to a large degree by the developments in the production of extruded plastic kits. That is not to say that all white metal kit production has stopped – far from it. White metal kits are still available from some suppliers, such as ABS, 51L and David Green, particularly for the more obscure prototype wagons or, less commonly, modelled railway companies.

However, there is one area where white metal is still in common use: that is for the production of wagon components, as shown in Fig. 15. These types of components are used by the modeller looking to modify a kit to a different prototype, or the modeller considering scratch building. Suppliers, such as ABS, Mainly Trains, 51L and others, produce a wide range of parts to assist the railway modeller in this regard.

The level of detail available with both white metal kits and components can be variable and is governed by the quality of the mould used for the cast production. In my experience, some of the casting is excellent and is ready to use straight from the box or packet, whilst some requires a fair degree of fettling to remove flash and casting lines.

It is important to remember that white metal is a soft metal alloy and thus it is prone to easy damage or deformation from bending and even breakage if not handled carefully. It can be soldered using a low melt solder, but unless you are confident in your ability and competent at soldering, you do run the risk of your component or kit turning into a deformed molten lump, only good enough to use as ballast for your next plastic wagon kit! I tend to use an impact adhesive, such as UHU, or a cyanoacrylate adhesive (super glue) to bond white metal parts and kits, as I do not consider my soldering abilities are up to the mark for construction of these types of kits.

On the basis of my experience, the use of a liquid cyanoacrylate (super glue) type adhesive works extremely well with white metal, especially if you apply a small spot on the contact surfaces first, press together and then, once this sets, use a fine wire (such as a straightened paperclip) to apply more adhesive liquid to the join and allow capillary action to draw the liquid into the joint. Once left to harden off, I have found this approach provides a very strong joint.

Fig. 15 Detailing wagon and van kits can be achieved simply using white metal components, such as the selection of components available from ABS Models.

The main advantage of using white metal as the principal material for a wagon kit is that the wagons produced are much heavier and are unlikely to require additional ballast (as noted previously for plastic kits). This weight advantage, combined with the use of metal wheel sets, leads to good track adhesion and better running qualities for the rolling stock.

The key point to be aware of that I have found with the construction of white metal kits is that the construction process needs to be carried out carefully and progress checked regularly to ensure that the body is square and level. This applies to all types of kits, but more so with white metal, as the material is less flexible or readily adjusted once the joint has been fixed, without the risk that the parts might deform or break.

BRASS

The production of brass kits using etching techniques has been around for many years. For many people, the level of fine detail achievable, combined with the weight advantage over plastic kits, makes the brass kit the pinnacle of model building. The level of detail and degree of accuracy attainable from etched brass kit construction is excellent, although this all comes at a modest cost premium. Brass kits tend to be much more expensive than the equivalent plastic kits and for someone starting out kit building, there is often the fear of spending a considerable sum of money on a kit and then ruining it by making a mistake that cannot be undone.

The skill level required for brass kit construction is higher and the kits tend to be more complicated than plastic or white metal kits. Having said all of this though, the modeller should not be put off from using brass kits. From my experience, it is better to start with the plastic and white metal kits and build up your modelling skills and understanding of how rolling stock kits are put together, before moving on to the brass kits.

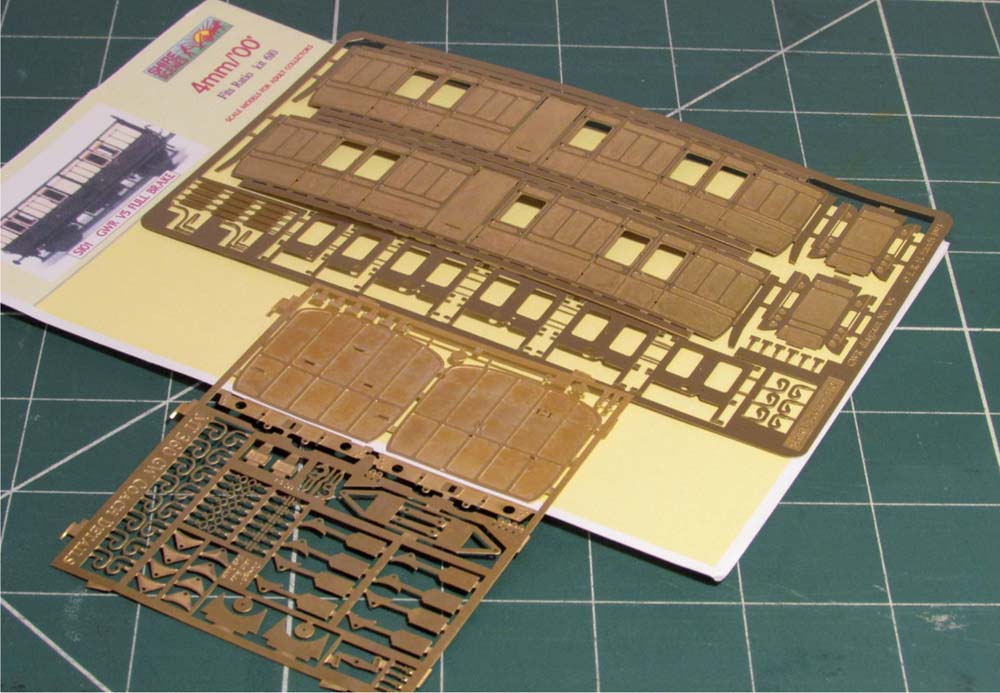

Some suppliers produce part-brass components to modify existing plastic kits, whilst others produce brass body kits to fit on plastic underframes, such as the Shire Scenes range of etched brass bodies for wagons and four-wheel coaches designed to fit on to modified Ratio plastic coach chassis (see Fig. 17). These part-brass kits are probably a good place to start to get the feel of how to work with brass before moving on to the more complicated full-brass kits.

With brass kits it is essential to read through the instructions fully before commencing any construction and it is also advisable to carry out dry runs of key elements of the assembly process before fixing. This will be discussed in more detail later. Brass kits can be fixed together by soldering or by the use of an adhesive, such as cyanoacrylate, depending on personal preference. Once constructed, brass kits provide strong models with a sufficient degree of weight that ensures excellent running qualities, especially when combined with good quality metal wheel sets.

Fig. 16 An example of the type of etched brass kit available is the Great Western Railway fruit van kit produced by Falcon Brassworks.

Fig. 17 A number of conversions for the Ratio plastic four-wheel coach kit can be achieved utilizing the Shire Scenes range of etched brass body kits.

RESIN

The use of resin for rolling stock construction provides an alternative to the use of plastic or metal. Typically these types of kits are produced as a single cast of the body with a small number of parts for the underframe. Alternatively, resin kits are produced as a one-piece body casting designed to fit on a plastic underframe provided separately, or for the modeller to provide from a source of preference.

Resin is a light material and unless weights are cast into the body during the casting process, then the modeller needs to add ballast. Resin is popular amongst modellers who want to produce their own limited runs of a particular prototype. The level of detail achievable in resin kits can be the same as, if not better than, that achievable with extruded plastic kits. The quality of the casting, as with white metal, is governed by the quality of the mould.

Whilst I have not yet used resin kits for OO gauge wagons and vans, I have used resin kits for the construction of a fleet of London Underground tube and surface rolling stock for a friend and fellow modeller constructing a model of Gant’s Hill Station. I have also used resin kits for the construction of O-16.5 rolling stock, running on OO gauge plastic underframe kits, for one of my own layouts at home.

WOOD

The use of wood as a base material type for constructing rolling stock is not common today in terms of commercially produced kits. Historically, wooden kits were produced by suppliers such as Ratio for wagons and carriages, but these have been superseded by the use of plastic. Although I have not constructed a rolling stock kit from wood, I have used wood as a material for the construction of parts of wagons, wagon loads, buildings and other scenic items for the model railway, including a scratch built Clyde Puffer to 4mm scale to sit in the harbour on the layout of a friend.

MATERIALS FOR SCRATCH BUILDING

There are no hard and fast rules about the choice of material for the project that you wish to undertake and in my opinion you should not rule anything in, or out, at the beginning until you have decided what your subject matter is going to be. It may, for example, be necessary to consider the use of a number of different material types in the same project to achieve the look and feel of the prototype that you intend from the model. I have used wood, plastic, metal and card for the projects that I have undertaken and each has its own advantages and disadvantages, a summary of which has been produced in the table Pros and Cons of Material Types.

For the construction of wagons and vans I have tended to use a mix of plasticard and brass sheet for the main body sections, whereas I have used plastic, brass and white metal to form the finer detailed components. Plasticard is readily workable to form the shape of the wagons, particularly the wagon and van ends, and this material can be sanded and carved as required. The brass sheets provide strength combined with a relatively thin profile and this has proved to be particularly useful for the formation of van roofs; for example, the roof of the GWR Mink F van described in more detail in Chapter 7.

MODELLERS’ TOOLS FOR KIT BUILDING

Having looked at the range of material types available for kit building and scratch building, it is perhaps worth making some comment on the types of tools that would be beneficial for the modeller to have to hand before starting to construct your own rolling stock. To some degree the types of tools required vary for material types, but many are common to all material types, therefore I have approached this on the basis that the modeller requires tools to build kits.

BASIC TOOLS

For the modeller considering the construction of plastic or resin kits, the following basic tools are recommended:

All of the above typically costs less than £20, the cost of a couple of kits, and is well worth the investment. If you can afford the additional expense, then the purchase of a cutting mat I have found to be essential, especially if you have to share the kitchen table as a work bench. I use an A2-size mat, but mats are available in sizes from A5 to A0; it depends on what space you have available for working.

PROS AND CONS OF MATERIAL TYPES

| Material | Pros | Cons |

| Brass |

● Excellent fine detail● Provides weight to improve running● More complicated detail easier to fabricate by etching than casting |

● Difficult to modify● More complicated, higher skill levels required● Relatively more expensive● Can be more difficult to work |

| Plastic |

● More forgiving of mistakes● Good for beginners● Relatively cheap● Good fine detail (on modern kits)● Easy to work/modify |

● Level of detail sometimes limited; new kits excellent● Lightweight so requires ballasting to improve running |

| Resin |

● Good level of detail● Cast in one piece for easier construction● Can be used by the modeller to cast limited run/bespoke components● Easier to modify than metals |

● Lightweight model requires ballasting to improve running● Not as easy to work with as plastic |

| White metal |

● Provides weight to the model for good running qualities |

● On older kits/components the casting is poor and requires a lot of preparation and fettling● Prone to deformation |

| Wood |

● Heavy material gives good running qualities● Realistic natural material● Can be relatively easily worked with the correct tools |

● Limited level of detail possible at this scale● Not often used, limited supply of suitable good quality materials |

The A2 mat is big enough to lay out kit components so that you can work through dry runs and have space to set sections aside whilst working on something else; but at the end of the day it is down to personal preference and what space you have available in which to work.

SPECIALIST TOOLS

Beyond basic tool requirements, the following additional tools might be considered as investments and some will probably be essential when considering the construction of metal kits:

Fig. 18 Essential tools for the model maker include a good craft knife with a selection of blades and a scalpel blade for fine detail work.

Fig. 19 Useful additions to the modeller’s toolbox include a set of needle files in a range of shapes for fine adjustments; whilst for drilling holes, a box of fine drill bits (0.3mm to 1.6mm) used with either a pin vice or Archimedes’ drill comes in handy.

Fig. 20 To ensure accurate cutting and setting out, a steel rule/straight edge and a set square are required; the glass tile is ideal for a flat surface on which to set your parts.

Fig. 21 For placing parts, making fine adjustment or holding small items during painting and fixing, a selection of tweezers is invaluable.

Fig. 22 A luxury item, but extremely useful if you can afford it, would be a boxed mini-drill and accessories, such as the Rotacraft one shown here.

Fig. 23 It is useful to keep several pairs of sharp scissors in your toolbox for removing parts from brass etch and for cutting card.

Fig. 24 One of the more unusual tools available is this tool for marking and cutting circles, available cheaply from most good stationery suppliers.

Fig. 25 A selection of pliers, side cutters and hard wire cutters are useful; and for brass kits, a pair of flat-faced pliers for bending and shaping brass components is essential.

A number of suppliers offer ‘Modeller’s Toolsets’ that include much of the basic and more specialist tools in one box, as well as some other tools of perhaps less obvious necessity. These sets can be a good way of getting together most of the tools that you are likely to need at some point in one go, but the toolsets can be relatively expensive and it might be more sensible to buy the minimum basics first to see if kit building is what you want to do, before spending significant sums on tools that you will never, or only very occasionally, utilize.

Fig. 26 To check the wheels are to the correct gauge, a brass OO gauge back-to-back tool, such as the one here supplied by Mainly Trains, helps solve poor running rolling stock.

I have built up my toolset over time, buying pieces as and when required, shopping around DIY stores for bargains, as well as antiques markets for old tools. I managed to pick up an engineer’s square and a selection of screwdrivers from an antiques market, all in perfectly good working condition and for a fraction of the cost of buying them new.

To ensure smooth running of the rolling stock that I make, whether from kits or scratch building, I make use of a brass back-to-back gauge to check all the wheel sets before installing them into the underframe. I have found that even RTR rolling stock can have back-to-back dimensions slightly ‘off-gauge’ straight out of the box, so the brass gauge comes in handy for checking these also. The brass gauge I use came from Mainly Trains (see Fig. 26), was relatively inexpensive at about £5, but has proved its value in resolving poor running problems with stock.

OTHER USEFUL BITS AND PIECES

As well as the list of tools I have provided, there are some things that can be utilized to help in the construction of kits that are not necessarily tools but which I have found can provide invaluable assistance in the construction of kits. The following items can be found around the house, or picked up cheaply from second-hand shops or market stalls:

Fig. 27 For the removal of parts from sprues or heavier duty cutting requirements, the use of a fine razor saw with a variety of blades and a cutting block could be of assistance.

FURTHER COMMENTS ON TOOLS

Sometimes I have been asked what has been the best investment in terms of tools and the answer is not necessarily the most expensive piece of equipment in your toolbox. For example, one of the most useful tools that I have bought in recent years was the device for marking and cutting circles. This cost the princely sum of £2 from an office supplies’ shop, but has proved invaluable during the fabrication of parts for all sorts of modelling projects, not just rolling stock.

Another example of excellent value is the fine tweezers that I had for laboratory work whilst at university over twenty-five years ago. This cost very little to buy, but is extremely versatile with very fine-ribbed gripping points and magnetic for getting parts into, or retrieving lost parts from, difficult and fiddly locations when building kits.

In terms of what tools have proven to be of less value, probably the best example would be the side-cutters I originally bought for £2.99. Although these types of tools can be picked up cheaply, in my experience the cheaper pairs break easily and in the long run investing in slightly more expensive pairs (typically £5 to £10 each) is the better-value, long-term solution. The moral of the story is do not buy the cheapest – if you can afford something slightly more expensive, then it is worth spending the money once at a higher rate, than lots of cheap items replaced much more frequently and ultimately costing more money.

For the more specialist tools, the most useful and value-for-money item that I have been lucky enough to get as a Christmas present was the Rotacraft tool (see Fig. 22). The particular model I have cost about £40, but came with many accessories, including grinding bits, sanding bits, drills and polishing tools. This all comes in a ready-made toolbox for storage and, as I have been able to demonstrate on numerous occasions, has many uses around the home, other than the model railway, and I would recommend adding this to your Christmas list!

Fig. 28 One of the most useful and cheapest aids for the modeller is a selection of wooden blocks. These have many and varied uses, including for those times when you need to prop parts of a kit together whilst the adhesive sets.