In the previous chapter I looked at the types of kit available and the methods and techniques for constructing kits as supplied by the manufacturers. In some of the examples described, where I looked at construction sequencing, I also described briefly the use of replacement parts and additional detail components. In this chapter, I will look at the use of replacement components and adding additional detail to your kits to enhance their appearance and perhaps make them that much more unique.

SPARES FROM KITS

When building a kit, you will often find that the manufacturer will provide alternative parts to create different variants of the prototype. These alternative parts should not be thrown away when you have finished building the kit, as they can form the basis of future kit detailing or conversion projects. Being a typical railway modeller, I hoard parts and transfers from old kits in case they come in useful on a future project. I always carefully remove the spare components from the sprues, clean them up and add them to the selection of pieces in my spares’ box (see Fig. 79). These spare parts can often provide a useful source of materials for detailing and converting other kits, or they can be used for scratch-building projects.

Although at first glance it might seem improbable that you might find a use for these items in the future, I have found that this source of parts is relatively cheap, having already paid for them when purchasing the original source kit, and they can be readily modified to suit your requirements. (For example, refer to the description of the scratch building of the bogies for the GWR Tourn wagon described in Chapter 7.)

Typical examples of spare parts that I have accumulated over the years include: upright and hanging vacuum pipes; brake gear to suit variable wheelbases; brake levers and vacuum cylinders; coupling hooks, buffers and buffer beams; ‘V’ hangers; axle boxes and tie bars; van and coach roofs and van end walls.

Fig. 79 The spares’ box for hoarded parts, specialist components, replacement wheels and bearings and so on, is a fundamental part of the railway modeller’s workbench.

In this chapter, I will look at how alternative parts, as well as the hoarded parts saved from previous kits, can be used in the construction of wagon and van kits.

REPLACEMENT BUFFERS AND COUPLING HOOKS

I find that on many kits the supplied buffers and coupling hooks are plastic and sometimes the incorrect pattern for the period that I choose to model. There are numerous specialist suppliers of components for the railway modeller, particularly in 4mm scale, and it is relatively easy to obtain a more appropriate pattern of buffer and cosmetic coupling hooks to replace the ones supplied with your kit.

By selecting white metal or brass components you are also adding additional ballast to your plastic model and helping to improve its running qualities on your layout. Replacement buffers can be bought as ready-made white metal castings or turned brass components; or they are available in kit form as sprung buffers.

I recommend that the installation of these replacement parts is carried out before the ends and sidewalls are fixed together, as it is easier to do this whilst the wagon body can be held flat on the work surface.

I tend to use white metal castings for replacement buffers from a number of different suppliers, such as ABS and 51L, as shown in Figs 80 and 81. To install the cast buffers, take a drill bit held in a pin vice and gently twist with your fingers, or if you prefer use an Archimedes’ hand drill, and guide the bit into the holes on the buffer beam. The pre-drilled holes in the buffer beam are used as guidance, so ream out the holes to the correct size for the shank on the replacement part.

For the construction of the Iron Mink van kit that was described in Chapter 3, the buffers and coupling hooks could be replaced with white metal items from the ABS range of components. In this example, the use of the ABS buffers would necessitate creating a 2mm diameter hole through the buffer beam to accommodate the buffer shanks.

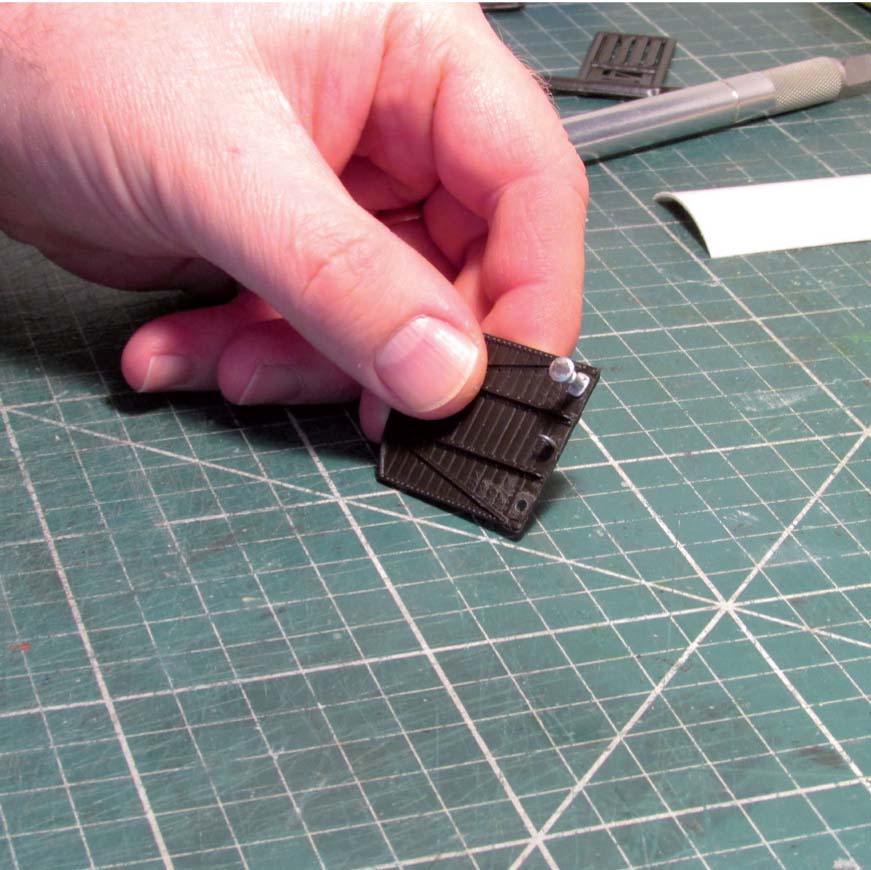

When reaming the hole has been completed, the moulded detail on the buffer beam plate can be removed using a fine file at the location of each buffer. The replacement white metal buffers are then removed from the sprues using a side cutter and the shank filed to shape, before gently squeezing the shank into the prepared hole in the buffer beam. With variation in the casting process, the degree of fine filing of the buffer shank can vary and has to be carried out on a trial and error basis to check for fitting in the prepared hole. Do not force the buffer shank through the hole as there is a risk that the buffer beam will be damaged or deformed in the process. Once inserted through the buffer beam, the buffers are held in place with a spot of cyanoacrylate applied on the rear face of the buffer beam and capillary action will draw the liquid into the join between the white metal and plastic parts.

Fig. 80 There are a number of suppliers providing a wide selection of white metal replacement components. Almost any conceivable part required by the modeller is available and it is good practice to have plenty in stock.

Fig. 81 White metal brake cylinders, axle boxes/springs and replacement sprung buffers are just some examples of the components that I keep in stock before starting any modelling project.

Fig. 82 To install replacement buffers, use a 2mm diameter drill to ream out the pre-drilled holes in the buffer beam for the replacement buffer shanks.

Fig. 83 The replacement white metal buffers and RCH coupling hooks fitted to the van kit have been gently pushed through the reamed out holes and are held in place by the application of impact adhesive at the rear.

To replace the coupling hooks in the same kit with cosmetic RCH white metal components, the hole for the hook is first checked to see if it will accommodate the alternative white metal component. If not the hole is carefully opened out with a sharp craft knife, the tip of a fine file or a fine drill bit (typically 1.2mm diameter). The hooks are then inserted and fixed in place in the same way as described above for the buffers, as shown in Fig. 83.

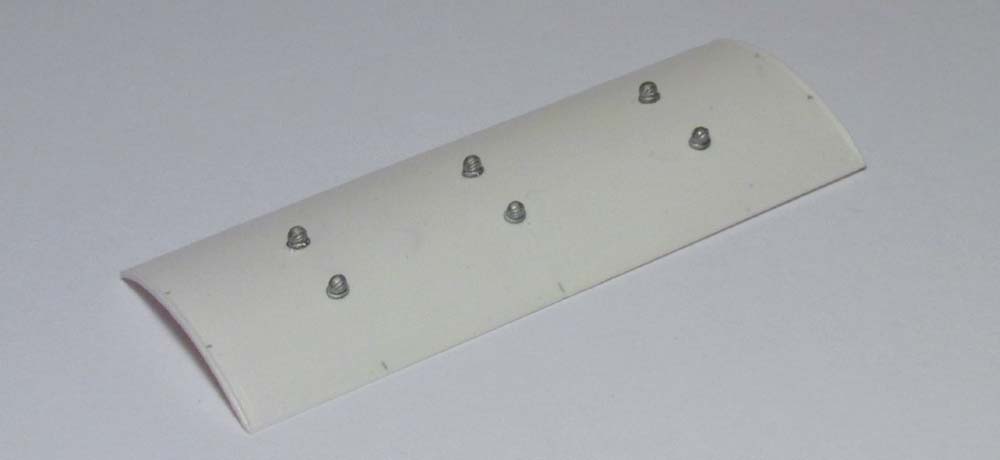

The installation of sprung buffers is carried out in a similar manner to the cast buffers, by first reaming out the hole in the buffer beam to the correct diameter to accept the parts. As an example, the installation of sprung buffers on the brass horse box kit identified in the previous chapter was carried out as follows. The cast brass shank was test-fitted in the pre-drilled hole in the buffer beam. Then the bush was fitted to the rear of the shank, on the internal face of the buffer beam. It is important with sprung buffers to make sure that the hole for the steel buffer head tail is correctly aligned through the cast shank and bush, otherwise the buffer will not work.

Using the buffer head tail as a jig, the shank and bush were aligned and fixed together with a spot of cyanoacrylate adhesive. The buffer was removed and the joint between the bush and shank strengthened with further application of the same adhesive. Once fixed, the assembly was tested with the buffer and spring to ensure correct movement before fixing the shank and bush to the buffer beam. On completion of the rest of the underframe, the buffer heads and springs are fed through the cast parts and the tail of the buffer head is bent through 90 degrees to secure in position.

Fig. 84 A wide selection of more prototypical replacement wheels is available in OO gauge from various suppliers. If planning to use replacement wheels, make sure these are ordered and kept in the spares’ box in advance.

REPLACEMENT WHEELS

Many kits these days are supplied with metal wheel sets, but not all, especially if you pick up an older kit from an auction site or from a stall at a model railway fair, as these will often be supplied with plastic wheel sets. Whilst the plastic wheels will work satisfactorily, the running of the wagon or van will be greatly improved by the use of metal tyre wheels running in brass bearings, as these provide weight, give better running qualities and adhesion to the track.

Sometimes you may find that where metal wheel sets are provided in a kit, they are not necessarily the correct pattern for the particular company, or period, being modelled and thus ought to be replaced with the correct pattern. Good quality metal tyre wheels are available from a number of suppliers in 4mm scale, such as Alan Gibson or Romford.

Fig. 85 Utilizing a brass back-to-back gauge to check the accuracy of the replacement wheels before installing them in your model. It is also good practice to use the brass gauge to check wheels on RTR stock, as this is often the cause of poor running.

Before starting your kit, if you have decided to purchase replacement metal wheel sets, it is advisable to check the back-to-back measurement on each set prior to fitting, as this is essential for good running quality on your layout. Selecting the track for your layout will influence the choice of wheel sets; for example, OO gauge, EM or P4 are all modelling at 4mm scale but to differing degrees of accuracy. I model at 4mm OO gauge fine-scale and tend to use the wheels produced by Alan Gibson for the rolling stock that I make. I have always found these wheels to be well made and accurate in terms of back-to-back measurements.

As an aside it might be useful to briefly explain the concept of back-to-back measurement. The measurement refers to the distance between the back of the wheel flanges on rolling stock. On RTR stock this can be variable and certainly on older rolling stock the flanges were extremely thick and ‘coarse scale’ by modern standards. Today the bulk of RTR stock runs on much finer scale flange wheels, looking less toy-like and more model railway like! This allows the use of stock on finer scale track that looks much more realistic.

I choose to model in OO gauge, but adopt finer scale principles such as the use of fine-scale wheels from the Alan Gibson range, running on PECO Streamline Code 100 track. I could use Code 75 track, but that would mean re-wheeling many older items of RTR rolling stock, which I occasionally like to run on the layout. This would not only cost a significant sum of money but also detract from the value and character of the older models, but this is purely a personal choice.

Therefore, back-to-back measurement for OO gauge should be 14.5mm on a track gauge of 16.5mm; whereas for EM it should be 16.5mm (track gauge of 18.2mm) and for P4, 17.75mm (track gauge of 18.83mm). Further information on the differing approaches in 4mm-scale modelling offered by OO, EM and P4 can be found on the respective society websites.

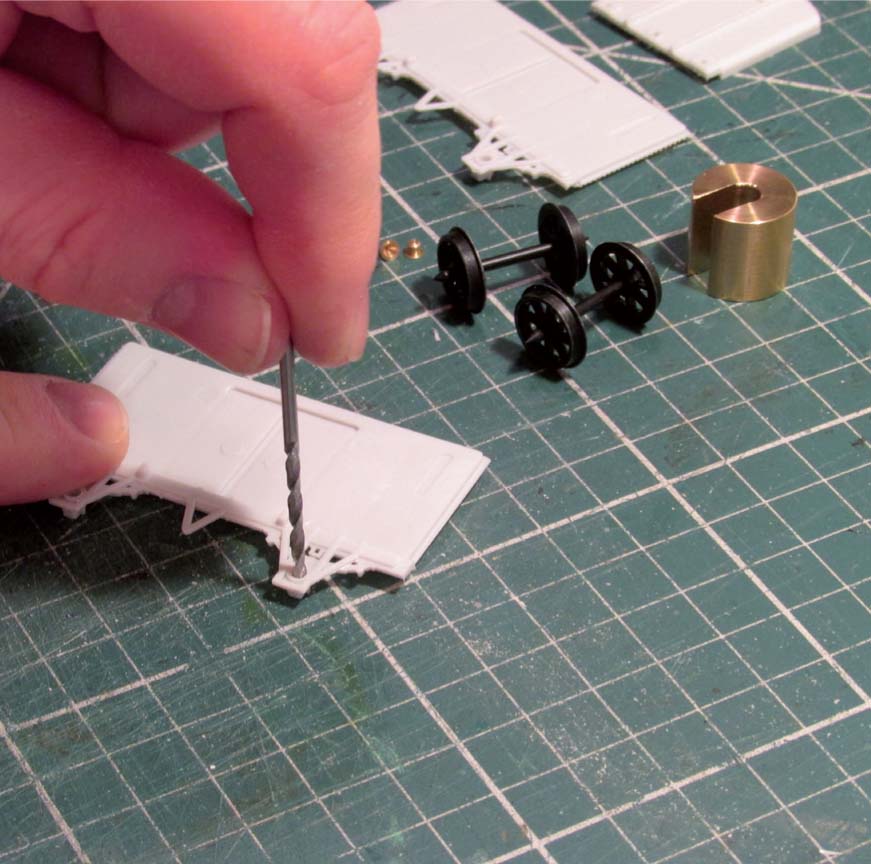

To install metal wheel sets in your rolling stock kits you first need to decide on the pattern of wheels and supplier. On my rolling stock, as I have stated previously, I tend to use OO gauge fine-scale wheels sets from the Alan Gibson range, but other makes are available. Each set of wheels will require brass bearings fitted in each of the axle boxes. Starting with the bearings, these are fitted by first reaming out the axle boxes using a 2mm diameter drill bit.

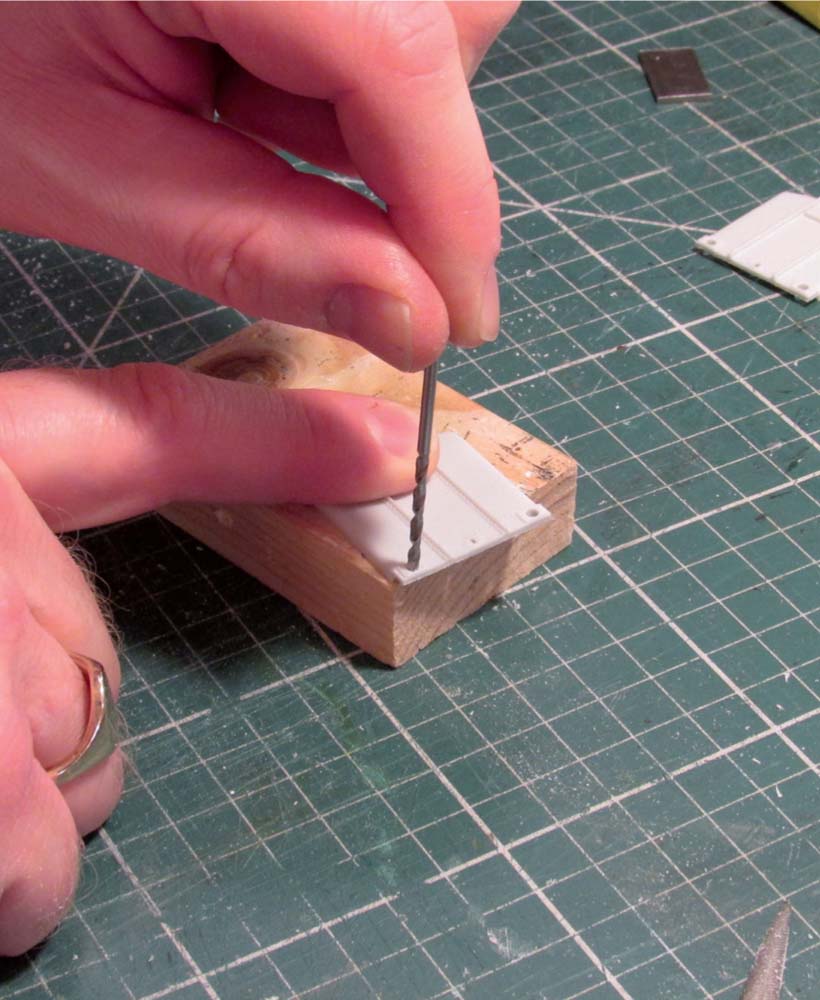

This must be done extremely carefully to prevent damage to the axle box and I tend to do this by gently twisting the drill bit backwards and forwards using the bit held securely in a pin vice or between your first finger and thumb. I also recommend that this exercise be carried out whilst the axle box and sole bar are still attached to the moulding sprue, as this provides some protection to the fragile parts during the process.

The depth of reaming can be checked by dropping the brass bearing into the axle box and checking that the shoulder fits flush with the rear face of the axle box. When the fine adjustments have been completed, each bearing cup can be fixed in place with a spot of cyanoacrylate adhesive dropped in to the axle box and the bearing pushed home. With the bearings fixed, the construction of the kit can proceed and the wheel sets dropped in to check all is square.

Fig. 86 The use of replacement wheels is best accompanied by the use of brass bearings for the pin-point axles. Installation of the brass bearings is accomplished by reaming out axle boxes with a 2mm diameter drill bit.

Fig. 87 It is important to check the depth of reaming prior to fixing brass bearings in place, to ensure a flush fit of the bearing to the inside face of the axle box.

It is advisable to leave the wheel sets in place until the underframe components have hardened off and typically I like to leave mine overnight to ensure the adhesive has securely fixed. The axle boxes can then be gently sprung apart to remove the wheel sets whilst the rest of the kit is completed and painted.

FITTING COMPENSATION UNITS

A further improvement in the running qualities of your rolling stock can be achieved by the installation of compensation units at one or both ends of the wagon. The unit rocks independent of the wagon body and underframe, thus providing a suspension element to ride over uneven track and maintain wheel contact with the rails.

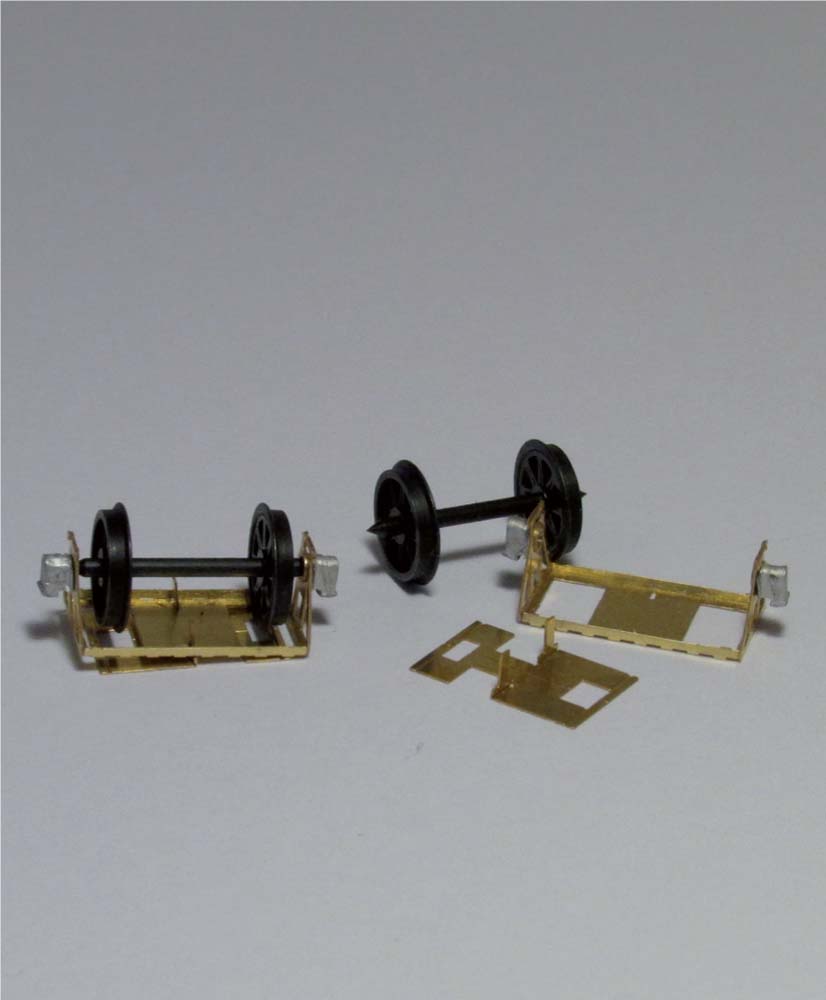

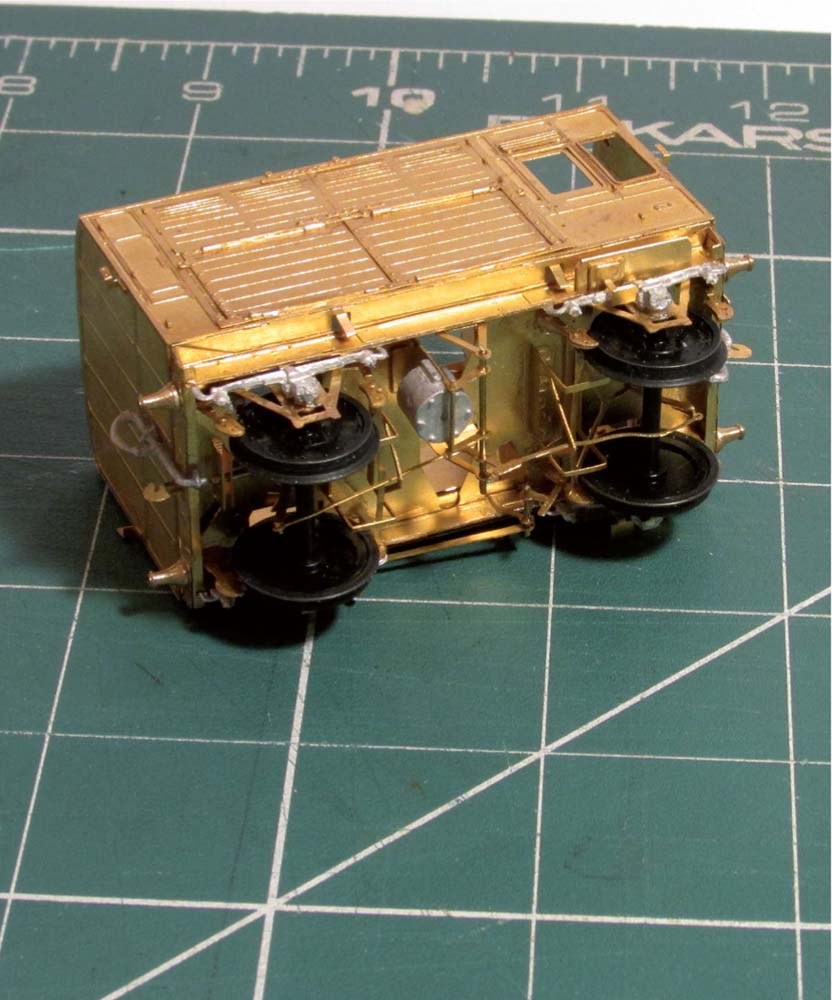

Typically the compensation unit is an etched brass fret that is folded up into shape and then fixed to the bottom of the wagon. For some types of units the structure typically comprises two parts: a base plate, which is securely fixed to the underside of the wagon, and a pivot or rocking plate, which sits onto lugs bent up from the fixed base plate. Once connected, the lugs are bent over to lock the pivot plate in position, while allowing it to rock from side to side, as required. If desired, these units can also be built up as rigid units, typically by folding up a stop bar on the base plate to prevent rocking.

Other types of pivot units utilize folding tabs on the floor of the wagon and on the unit, which have been pre-drilled with a hole through which a short piece of wire (typically 0.7 to 0.9mm diameter) can be threaded and used as the pivot bar for the plate.

The brass bearing cups are fitted to the compensation units in pre-drilled holes and the wheels sit in their bearings located within the compensation unit and are independent of the axle boxes on the wagon, as shown in the photograph in Fig. 89. The compensation unit shown in the photograph was used for the white metal kit described in Chapter 3 and can be made as either a rigid or a rocking unit.

Fig. 88 A typical metal wagon kit comprising brass and white metal components, with the etched brass rocking unit at the bottom of the figure.

Fig. 89 The etched brass compensation units are folded up and secured to the separate base plates using the fold-up lugs passing through slots in the unit. The lugs are then twisted to stop the unit becoming free.

Fig. 90 An alternative type of rocking compensation unit on the GWR Horse Box kit produced by 51L utilizes a 0.9mm diameter wire threaded through the unit and locating fold-down flaps on the wagon floor.

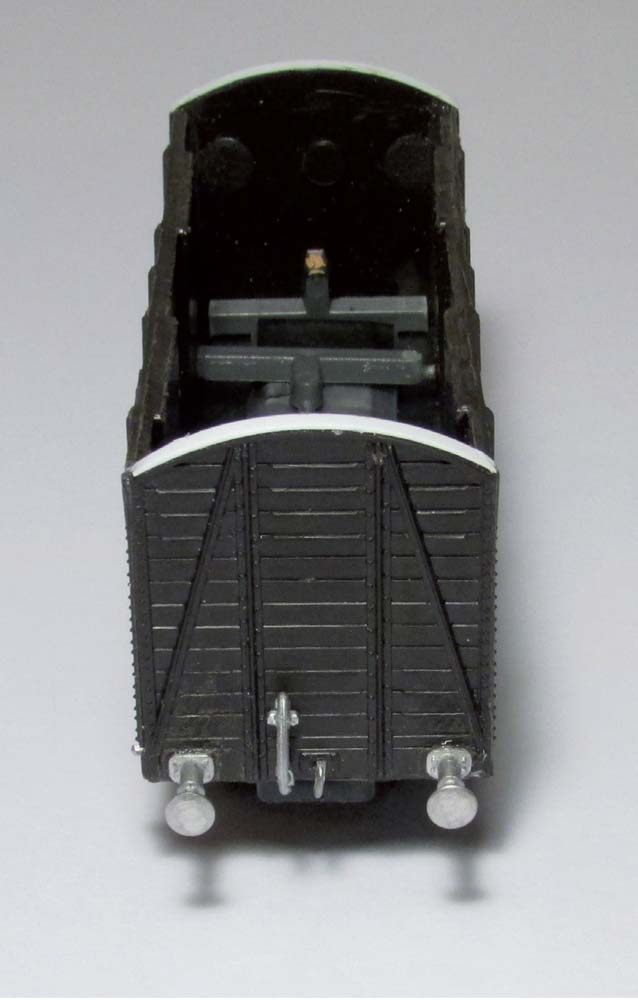

Fig. 91 The plastic van kit as produced by Colin Ashby to be used as the starting point of the wagon detailing described in this section.

DETAILING A VAN KIT

To show how a van kit can be detailed I have used a worked example of a kit for a GWR Fish van to Diagram S6, produced by Colin Ashby, which I believe may no longer be in production, but the principles adopted here apply to other van kits. A kit of the same wagon was also available as an Ian kirk kit in the past (before the range was sold to Colin Ashby, I believe) and both examples of the kit can occasionally still be picked up on eBay for a modest price.

The kit as supplied includes all the parts required to construct the body and underframe; the modeller is expected to provide wheels, bearings, couplings, paint and decals. I built one of the Ian kirk kits some thirty years or more ago and this still runs on my layout today, alongside the more recent example constructed from the Colin Ashby kit. The earlier example was built as per the kit with just the addition of upright vacuum pipes as extra detail. The later model has been more heavily detailed, as described in the worked example below.

PREPARING THE PARTS

Construction of the kit began with carefully removing the main body sections and roof from the sprues, for which I used a fine-tooth razor saw. The use of the razor saw in preference to a craft knife allowed more control of the removal process and did not stress the joints between the parts and the sprue that would otherwise have occurred with a craft knife and risk damaging the parts. The parts were then cleaned up to remove flash from the moulding process and the sprue connecting points, so that they were ready for building.

Fig. 92 The preparation of bodywork should be undertaken in the same way as you would when building any wagon or van kit of this type.

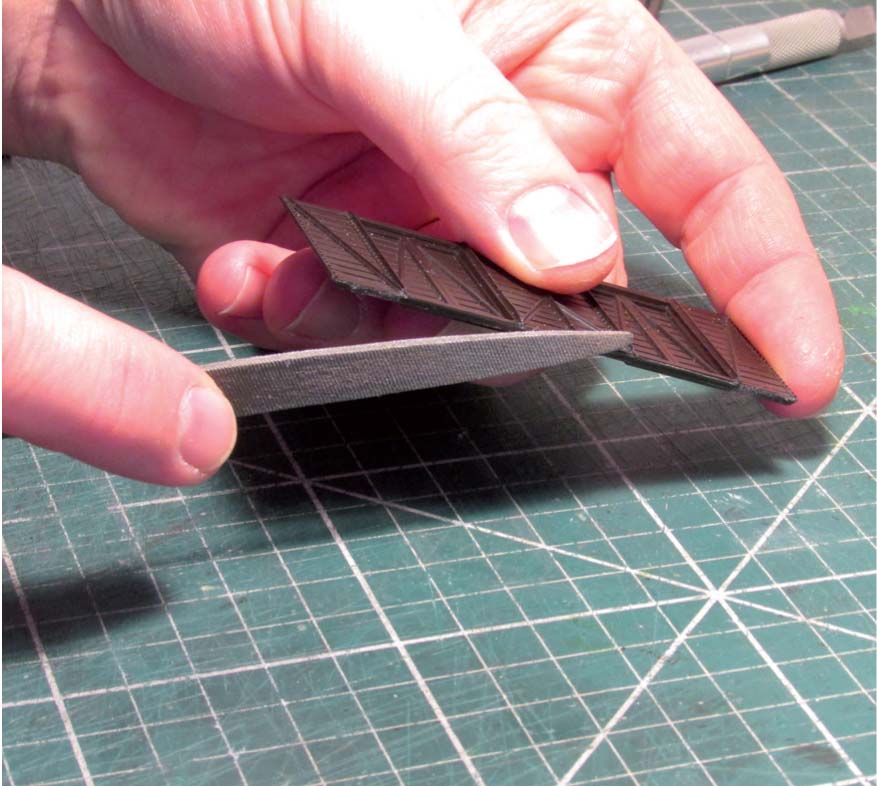

The buffer beams on this van kit are part of the end wall sections and include moulded buffer shanks. Plastic spacer rings and buffer heads are provided in the kit to make up the buffer assembly. I was not convinced that these represented the pattern of buffer that I wanted to use on the finished model. Therefore, I chose to remove the moulded plastic buffer shanks carefully with a sharp craft knife and then, using a fine needle file, removed the moulded buffer plate on the buffer beam.

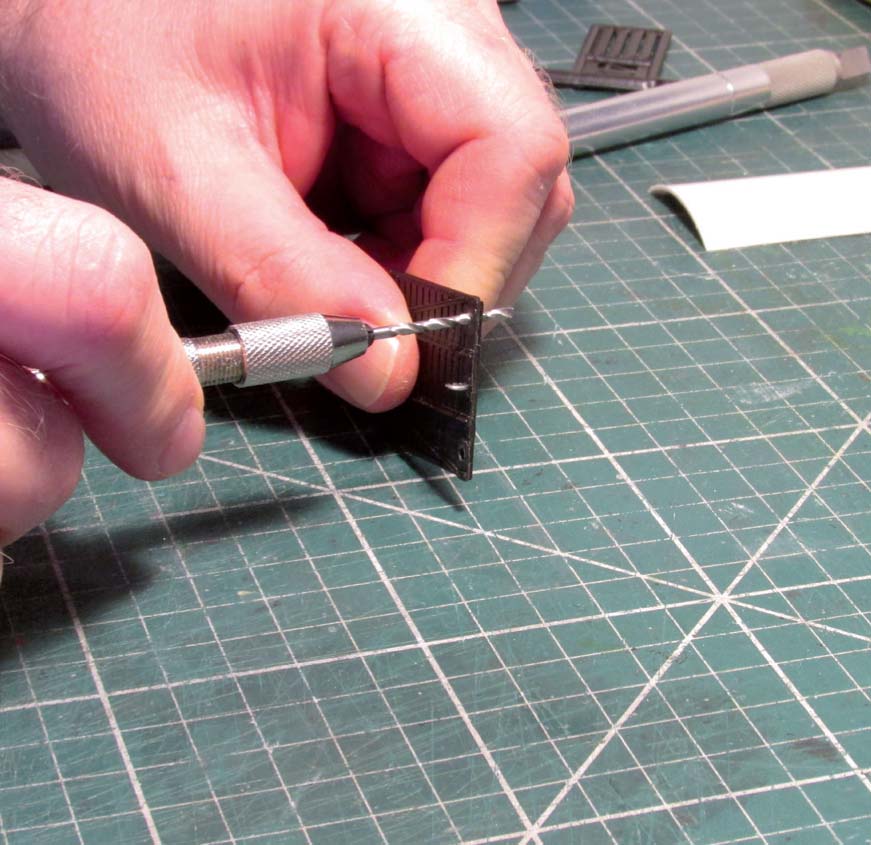

A 2mm diameter drill bit was then used to bore through the buffer beam at each location to accommodate the replacement white metal buffers that I selected for this kit. A third hole was drilled in the central buffer beam plate with a 1.2mm diameter drill to accept the white metal cosmetic coupling hooks.

Fig. 93 The decision to use replacement white metal buffers required the removal of the moulded buffer shanks with a chisel blade craft knife.

Fig. 94 Using a 2mm diameter drill bit, the next step was reaming out the pre-drilled holes in the buffer beam for the replacement buffers and then using a fine file to remove any moulded detail.

Fig. 95 Fitting replacement white metal buffers should be undertaken carefully. Test fit the white metal shank in the reamed hole and, if necessary, file the shank down. Do not force the part through the hole as this will stress and distort the plastic buffer beam.

Fig. 96 Re-profiling the moulded axle box tie bar utilizing needle files helps to obtain a thinner profile and appears more realistic.

The underframe required some work with a sharp craft knife and needle files to remove flash and to reduce the thickness of the axle tie bar to a more realistic scale size. Alternatively, this piece could be removed and replaced with a piece of 0.5mm diameter brass wire, if preferred.

The axle boxes were reamed out to 2mm diameter to accept the brass bearing cups and then the underframe parts were removed from the sprue, again making use of the fine razor saw, as described for the removal of the body sections.

BODYWORK AND UNDERFRAME CONSTRUCTION

Following the instructions supplied, I proceeded by first fixing one sidewall and one end together, ensuring that the joint was at 90 degrees. This required some preparatory work with fine files before fixing. A dry run of this type of joint is recommended before fixing with liquid polystyrene cement, to check that the mitred corners meet squarely and without gaps.

The next step was to fix the floor to the sidewall and end wall, ensuring that the lower face of the floor was flush with the bottom edge of the sidewall and at the same time sat level with the top edge of the buffer beam. This required some gentle tweaking to get it right, but once satisfied that all was square, I left the body to harden off on a glass tile, supported with wooden blocks to prevent the body moving or twisting.

When the first section had set, I added the second sidewall and end wall as before. I found that the floor section was slightly shorter than the gap between the end walls. This demonstrates where dry runs and fine adjustments to the wall joints may be necessary, to check that the joints are all square and level. If you are still left with a small gap, as in this case, the gap can be packed using a piece of microstrip fixed on the end of the floor section. When the body had been fixed together, it was set aside and left to harden off.

Taking the sole bars, it was important to check the length of these parts against the space on the body between the back of the buffer beams. It was necessary to adjust the length of the sole bars on this example, which must be done at the same end for both sides to ensure that the axle boxes remain in line. To achieve this accurately, the easiest method I have found is to place the two sole bars back to back and offer up to the body kit. Mark the required reduction in length and cut both sole bars at the same time, keeping them clamped together. If the reduction in length is more than a millimetre or two, it is advisable to cut a small bit from each end of the sole bars to ensure that the axle boxes remain proportionally the same distance from each end of the wagon.

When cut to the correct length, I took one of the sole bars and fixed it to the underside of the body along the alignment of the joint between floor and sidewall. The exact position of the sole bars depends on the length of axles used in the wheel sets and is governed by the back-to-back measurement. A dry run is useful to make sure that the overhang each side of the sole bars is the same, i.e. the underframe is located centrally under the body and not to one side. A useful check is also to put the wheel sets in position to ensure that axle boxes are square and that the wheel axles are perpendicular to the sidewall of the body. The second sole bar should be added and the wheel sets put in place to check correct alignment and free-running. The whole assembly should then be left to harden off.

Fig. 97 Detailing of the underframe using fine wire and etched brass wagon detailing components, such as the ones supplied by Mainly Trains for the ‘V’ hangers and cranks.

Fig. 98 White metal components for vacuum pipes and DC brake levers provide additional underframe detail.

FITTING BRAKE GEAR

The next stage was to clean up the brake gear parts from the kit and test fit on the underframe to check the alignment of brake shoes and wheel treads. On the side of the wagon where the moulded vacuum cylinder is on the floor, I found that the brake gear was pushed too far out of alignment with the wheels for this to be acceptable to my eye.

Using a sharp chisel blade on my craft knife, a thin slice of the vacuum cylinder was removed on the outer edge, facing the brake gear assembly. Further fine adjustment was made with files and the brake gear test-fitted again to check alignment. Repeat this process, if necessary, removing a thin sliver of the cylinder at a time until the brake gear lines up with the wheel treads. When satisfied with the alignment, fix in place with liquid polystyrene cement.

ROOF ADJUSTMENTS AND DETAILING

Whilst the brake gear was setting, I check-fitted the roof to the body. I found that this part did not fit squarely with the end walls of the van, where an obvious gap was present. To reduce the gap between the top of the end walls and the underside of the roof, I needed to carry out quite a bit of adjustment, utilizing fine files, to the sidewalls and the roof. The height of the sidewalls was reduced uniformly and then the ridge on the underside of the roof where this sits on the sidewalls was also filed to reduce the height. When this was completed, I found that there was still a small gap of approximately 1mm between the top of the sidewall and the underside of the roof. This was solved by fixing microstrip to the top of the end walls and gently filing this down, checking the fit with the roof frequently to ensure that too much is not removed.

Fig. 99 To ensure a good fit of the roof to the body, a dry run of the assembly identified the need to file down the tops of the sidewalls and to add microstrip to correct the end wall profile to match the roof.

Fig. 100 The prototype van had shell vents fitted on the roof for ventilation. To replicate this on the model, white metal shell vents can be used to detail the roof, using line-drawings to locate the correct positions.

When happy with the fit of the roof, I then set about checking the roof profile and adding detail, specifically the shell ventilators in the roof. The wagon roof on the prototype had two rows of shell ventilators along the alignment of the end wall vertical bracing, equally spaced about the long axis centre-line of the roof. Using the line-drawing of the wagon reproduced in Atkins et al. (2013) as reference, I marked out with a pencil the centre-line of the roof then the corresponding points for the tops of the vertical bracing on each end wall, as the ventilators are positioned along the same alignment. I then placed the long edge of the roof against the line-drawing and marked on the edge of the roof the points where the ventilators were fitted. Using a rule and pencil it was then possible to mark out the six locations of the ventilators, where the construction lines crossed.

With the locations of the ventilators marked, I drilled a 1mm diameter pilot hole at each location, re-checked the locations and then reamed out the holes to 2mm diameter to accept the shank on the underside of the white metal ventilator components. For this model, I used ABS white metal components, as the white metal adds a bit more weight to the overall wagon to address the issue of weight and plastic models (discussed in Chapter 2).

Fig. 101 An element of wagon and van kits not often modelled is the retaining loops to the brake gear. A close-up of the etched brass brake gear retaining loops added to this model.

The six ventilators were pushed home through the holes in the roof and aligned correctly using a photograph of the completed prototype wagon as reference. A spot of impact adhesive (UHU) was used on the underside of the roof at each shank to hold the parts in place. The roof was set aside to dry whilst further detailing was undertaken to the wagon body.

UNDERFRAME DETAILING

The next bit of detailing to the body was the addition of cast white metal Dean Churchward (DC) brake handles in lieu of the ones supplied in the kit. These were carefully cut from the cast sprues, cleaned up with a fine file and fixed in place with a spot of cyanoacrylate adhesive.

Replacement white metal vacuum pipes were added to the end walls, fixed with a spot of glue to the end wall and the underside of the buffer beam to ensure a secure hold. Etched brass label clips from a Mainly Trains wagon detailing kit (MT 166) were then fixed to the left-hand end of the sidewalls of the van, about four planks up from the sole bar, checking against a photograph of the prototype (Atkins et al. 2013) to get the correct position.

With the brake gear hardened off, the next stage was to add a representation of the brake linkage using etched brass ‘V’ hangers and cranks (Mainly Trains kit MT 230) and 0.5mm-diameter brass wire. Using a 0.5mm diameter drill, I carefully drilled a hole in the centre of the plastic brake gear crank, supporting the plastic part on a piece of wood to prevent it breaking whilst drilling. A piece of the brass wire was then threaded through the hangers and crank to form the connecting rod. This allowed the alignment to be checked of the ‘V’ hangers on the rear of the sole bar on each side of the wagon, as well as the crank for the vacuum cylinder.

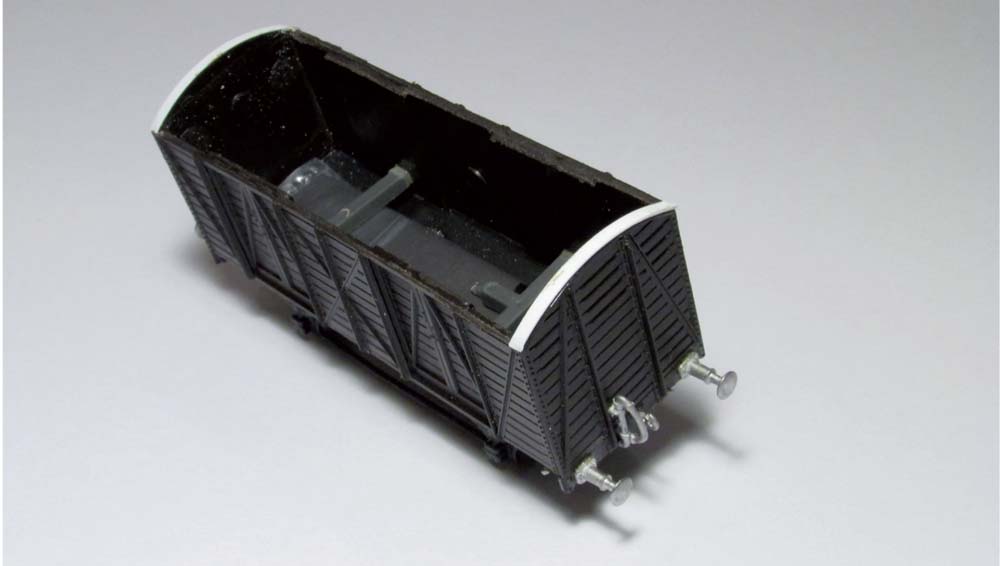

Fig. 102 This end view of the wagon shows that all of the modifications to the end wall have been completed, using various materials and components.

Fig. 103 Completion of the underframe detailing showing the use of etched brass and white metal components.

Once satisfied with the alignment, a small spot of cyanoacrylate will hold the ‘V’ hangers and crank in place; further adhesive can be dropped on to the joints to strengthen them, as described in Chapter 3. When these parts have been secured in place, the connecting rod was fixed with a spot of cyanoacrylate on the ‘V’ hanger and then the wire was trimmed to length with side cutters.

Before adding the remainder of the brake linkage, I opted to install on the underframe the small mounting blocks, which I use for the types of tension lock couplers that I use on my rolling stock. Once these had been set in place, I then set about using parts from my spares’ box and more 0.5mm diameter wire to create a representation of the brake linkage between the hand brake handles and the central connecting rod. To do this, it is important to have the wheel sets in place, to check that the linkage rods do not inhibit movement of the wheels and axles, as this will affect the running qualities of the finished wagon.

With the hangers, rods and connecting bars to the vacuum cylinder formed from plastic rod in place, this completed the underside detailing, except for the addition of brake gear retaining loops. These were formed from etched brass parts suitably bent in to a ‘U’ shape and fixed just behind the brake shoes, as seen in Fig. 103.

FITTING ACCESS STEPS

The final part of detailing on this van was the addition of the side steps below each of the doors. On the prototype, two steps were provided at each location to allow access to the van from both platform level and from ground level, such as when being loaded or unloaded at a quay. The model was supplied with steps to reproduce this feature of the prototype. The first stage was to fix the upper steps in place on one side of the van, as these affix directly to the sole bar and can be quickly aligned and set below each door.

With the top step firmly fixed in place, I then offered up the lower step and checked its position directly below the upper step. The lower step fixes to the axle box and was held square by two connecting rods with the upper step, although the parts for the connecting rods were not supplied in the kit – the modeller is required to supply plastic rod or wire to form these parts. The lower steps provided with the kit have to be modified with a cut-out to allow it to slot around the axle box. This is best done by checking the step alignment with the upper step and then marking on the inside edge of the lower step with a pencil the position of the axle box.

Fig. 104 Once all of the modifications and detailing has been completed, the roof is test-fitted to ensure all is finished prior to painting the model.

Using a sharp craft knife, two small cuts were made from the back edge of the step perpendicular to the edge for a depth of approximately 1mm. I connected the two cut lines with a third cut, then tidied up and made adjustments with fine files to get a snug fit around the axle box and so that the two steps were aligned vertically one above the other. This was a bit of a trial and error process to get the right fit, so I only removed a small amount of material at a time and kept checking the fit and alignment. I found that it is best to complete the steps on one side of the wagon first and let them harden off before turning the wagon over to start the second side.

I would recommend that fitting the connecting bars is best done after the steps have been fixed in place and the glue hardened off. On the model that I built thirty years ago, I used plastic rod for the connecting bars between the steps, whereas on the more recent model I used brass wire, which I believe gives a better scale-size effect on the finished model.

Inside the wagon I wanted to add more weight to improve the running quality of the model, so I used some curtain hem weights obtained from the local haberdashery shop. The weights supplied were slightly too long for the van, but could easily be cut with a sharp heavy duty knife, such as a Stanley knife. The weights were supplied in small plastic bags, so sealing the weights in the bags I then fixed the bag with impact adhesive to the floor of the wagon. To prevent the risk of these coming loose over time, I used some sections of plastic sprue cut to the correct length as braces across the top of the weights and fixed to the internal sides of the sidewall with liquid polystyrene cement.

FINISHING TOUCHES

At this stage, the wagon was now ready for painting. I always leave the roof separate from the body whilst painting for ease of holding. The underframe was painted matt black and the body was painted coach brown to represent a wagon during the 1920s and 1930s to match the period on my layout.

The roof was painted coach white and left to dry fully before fixing to the body. When fixing the roof in place, liquid polystyrene cement was applied to the top of the body walls and then the roof held in place with elastic bands for at least twelve hours to allow the glue to fully harden off.

Fig. 105 A common problem with plastic wagon kits is that over time there is a possibility of the sidewalls bowing inwards. An effective method of preventing this happening is to install internal bracing using scrap pieces of sprue. Also visible in the figure are the additional ballast weights wrapped in plastic and fixed to the inside floor of the van.

Fig. 106 The use of photographs of the prototype is essential to ensure the correct locations and detail of decal placement after painting of the wagon and roof in appropriate colours. An additional internal brace for the top of the sidewalls is also shown in this figure.

Fig. 107 The completed and detailed van with correct livery and decals in accordance with the official prototype photographs of a GWR Fish Van to Diagram S6.

Fig. 108 The application of underframe details equally applies to open wagons as to vans. In this example of a British Railway 10T open wagon, the use of etched brass parts, wire and plastic rod to complete the detailing can be seen.

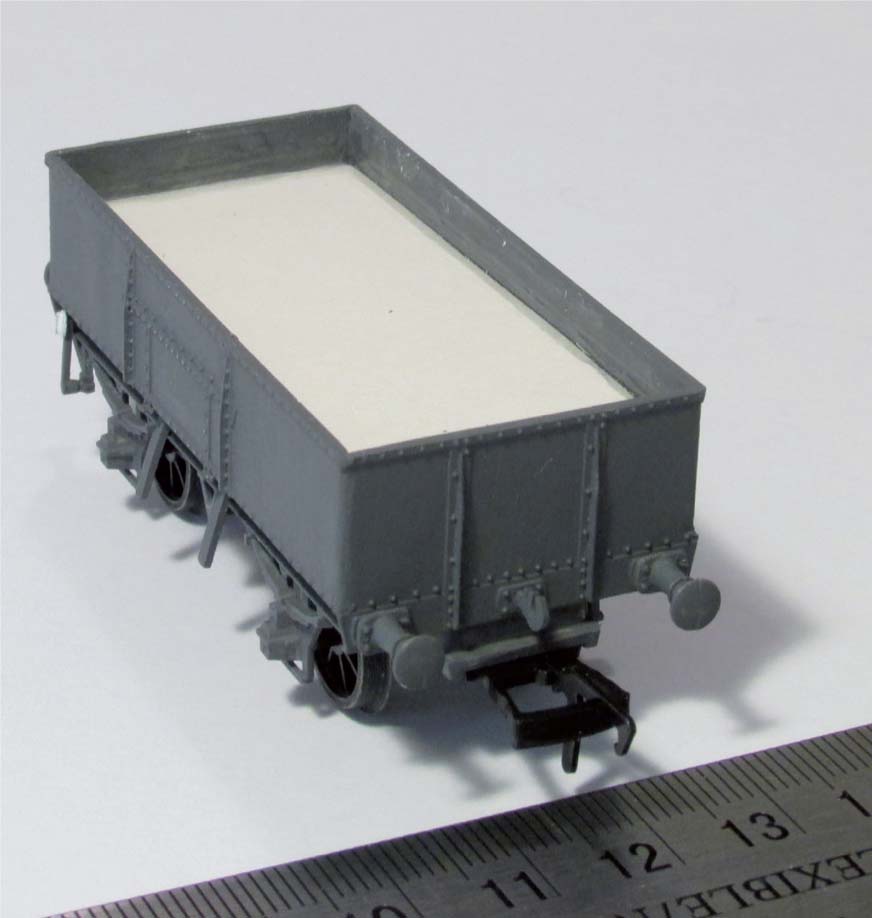

DETAILING OPEN WAGON KITS

As with the detailing of van kits described earlier in this chapter, the detail to the underframe of an open wagon is very similar in principle, comprising the inclusion of brake gear and linkages, as well as brake levers and, where applicable, vacuum brake equipment, but this is dependent on the prototype being modelled.

Detailing of the body of an open wagon can include the addition of etched brass corner plates and rivet strip details to improve the moulded representation of the kit, as well as the addition of door hinges, load-securing rings and other fitments. Fitting of the etched brass components is described further in Chapter 7 as part of the scratch-building of the Tourn open wagon. Further detailing of open wagons lies with the addition of loads, a representation of how these loads were secured and, where necessary, covered for transit. These detailing options are considered further in the following sections.

ADDING LOADS TO OPEN WAGONS

Open wagons rolling up and down the railway network would not always be empty in the real world, as empty wagon movements cost money in that they do not provide a return against the cost of movement. In this way, if you wish to represent real railway practice on your layouts, wagons running on your layout should also not be running up and down empty all the time. In this section I have provided some ideas as to how you can easily and relatively cheaply provide wagon loads for open wagons to represent this practice on your layout.

Fig. 109 Some of the more common brass detailing items available include etched brass rivet strip, corner plates and brake gear for wagons, as well as door handles for vans and coach stock.

During the early part of railway history in the United kingdom, one of the principal purposes of railways was to carry raw materials, such as coal and minerals, to support the industrial development of the country. Up until the early part of the twentieth century, these materials were typically carried in wooden-bodied open wagons and formed a significant part of the rolling stock inventory of both the railway companies and the private collieries and mines. Although I have described this as adding a coal load to an open wagon, the same principles apply to other minerals, just utilizing different coloured materials.

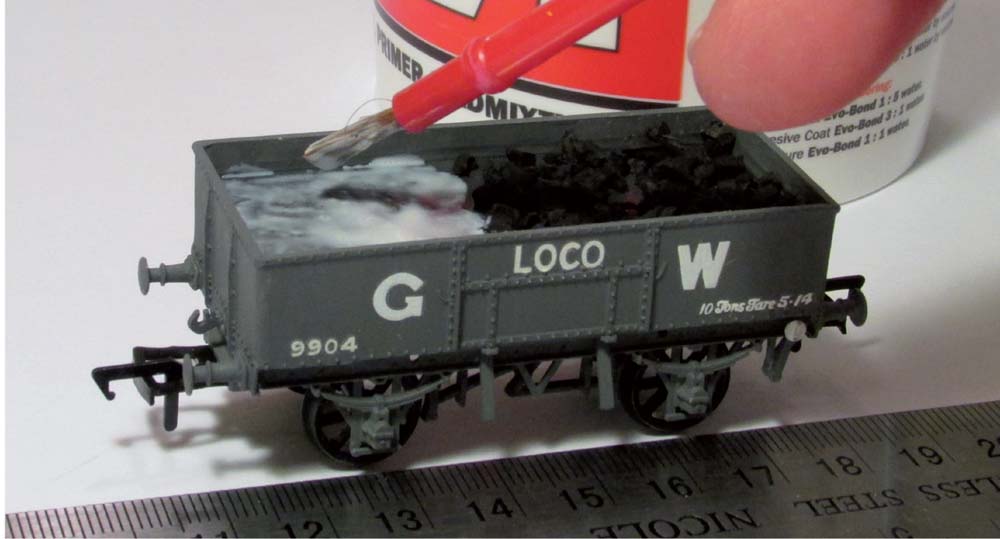

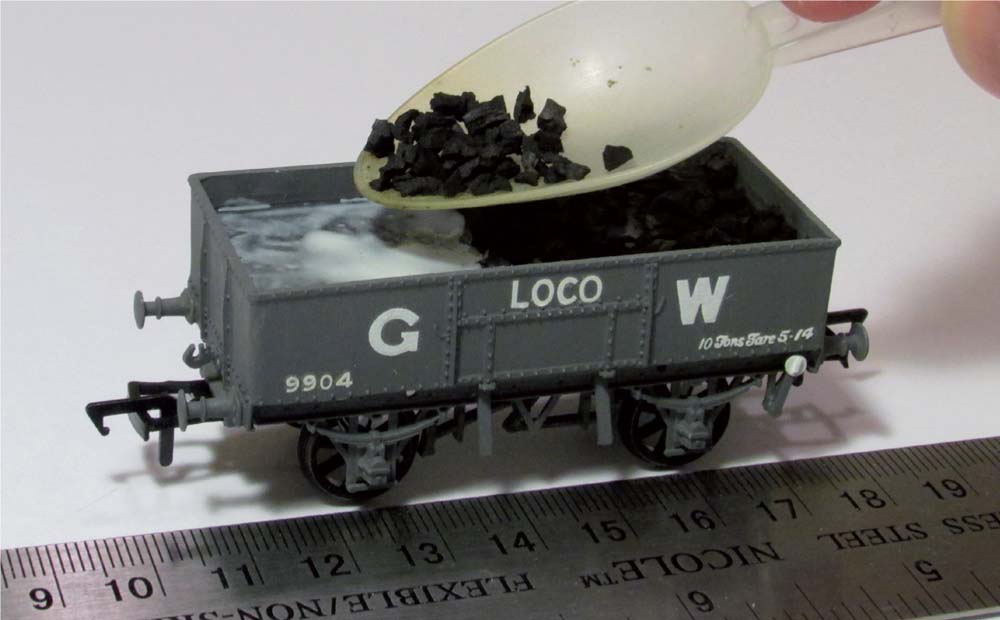

To insert a coal load into a wagon, first decide whether you wish to make this a permanent addition or a removable load. In the example described here, I decided to make the load a permanent addition in a Cooper Craft loco coal wagon. To form the load I first inserted a raised floor into the wagon, which allows you to add additional ballast weight under the raised floor should you so desire.

Fig. 110 Providing wagon loads in open wagons is part of making your layout look more realistic. If you do not want to fill the wagon completely, adding a load can be made easier by the installation of a false floor formed from card and fixed in to wagon, as shown.

The floor was formed from a piece of thick artist card, measuring approximately 62mm by 27.0mm, cut to be an exact fit to the inside of the wagon body. These dimensions will vary from wagon to wagon and for each wagon that you wish to add a load, it will be necessary to measure the internal dimensions once constructed.

To bring the false floor up to the desired level in the wagon, packing pieces can be cut from the same thick card and stuck directly on to the wagon floor, if the load is intended to be permanent. For a load that you wish to remove, then a base piece can be cut to the same size as the false floor on which the packing pieces can be fixed. The ‘new’ floor is then stuck in place on top of the packing pieces.

I tend to use white PVA glue to fix card to plasticard and then stream a thin line of white PVA around the edge of the floor and the walls to seal the join if it is a permanent load. Once dry, the new raised floor is then painted black or dark charcoal grey and allowed to dry.

Fig. 111 Before adding the load, in this case coal, the false floor was painted a dark charcoal colour to match the colour of the proposed load so that no white card was visible through the added load when complete.

Fig. 112 When the false floor has been completed, the wagon load can be added. The load is held in place on the false floor with PVA glue, which is best applied with a brush.

Fig. 113 It is a good idea to ensure that the PVA adhesive is worked into the gap between false floor and sidewall of wagon to help secure the floor to the wagon side to prevent bowing.

Fig. 114 Using a small spoon apply the material forming the load to the wet PVA glue. Build up the thickness of the load by applying further PVA and material. In this instance the ‘coal’ is formed from shredded cork dyed black, but real crushed coal could be used as an alternative.

Fig. 115 A completed wagon with decals and load looks very effective and provides a touch of realism to your model railway layout.

Select the material you wish to use, which could be real coal crushed to size, but in my case I used shredded cork painted matt black. The load was glued in place using a watered down white PVA-type glue, which when dried provided a glossy sheen on some of the faces of the cork particles, representative of what you would see with real coal or anthracite.

A similar approach can be used for other aggregate or crushed rock loads, adjusting the colour of the false floor to match or closely resemble the colour of the material that is being transported.

Adding a Timber Load

During the steam period of our railway heritage, in particular, the transport of wood and timber on the railways was a significant operation. A browse through old photograph collections and books will reveal images such as imported hardwoods being transported from ports to mill, sawn timber transported from mills to local goods yards and the transport of timber props for the coal-mining industry.

To make timber loads for open wagons I have found the best source of material to represent sawn timber is the various drink stirrer sticks you can pick up free with your take-out coffee, or lollipop sticks available from any homeware store. These ready-made pieces of sawn timber can be cut to any width or length to suit the wagons that you have running on your layout. The wood can then be either left natural, or can be painted, or treated with varnish to represent different types of wood.

A further example of a wood load for wagons is to provide a representation of pit props or telegraph poles. To form these types of materials, I have found that the wooden barbeque skewers from the supermarket can be readily adapted and then varnished or painted accordingly.

The accompanying photographs show some examples of timber loads in both standard and long wheelbase wagons and you will note that in the standard 10ft wheelbase open wagon the timber has been loaded following prototype practice so that it rests on the end wall at one end of the wagon. This type of detail all helps to create a realistic model railway, mimicking practices from the real world. This is easily achievable and the result of researching through photographs of freight operations on the railways can provide you with valuable information on the way various materials were loaded and transported.

SECURING WAGON LOADS

On the 12in to the foot railways, wagon loads were held in place in open wagons using chains, ropes or wagon tarpaulins, or a combination of these methods. The same ought to be represented on the models that you recreate in 4mm to the foot scale.

Fig. 116 Timber loads were a typical wagon load of the steam era and this open five-plank wagon is shown prototypically loaded with timber planks formed from recycled coffee stirrers.

Fig. 117 For longer wheelbase open wagons, the opportunities for larger loads can be considered. The wagon on the left is loaded with planks, whilst the one on the right has a load of creosoted posts, formed from barbeque skewers cut to length and suitably painted with acrylics.

Ropes

To represent ropes, I tend to use brown or dark-coloured threads ‘borrowed’ from my wife’s sewing box. The thread can be twisted together to make thicker ropes if required and can be bent and stuck in position with PVA type glue. It is important when fixing the threads in place on your model that they are laid out in the same way that a real wagon is loaded and the load secured.

Reference to prototype photographs will provide a valuable source of information to show how tarpaulins are wrapped at the corners of wagons (or not) and the way that loose, uncovered loads are secured with ropes.

Chains

For heavier loads, chains would have been used instead of ropes and you can buy fine chain from a number of suppliers to represent load-securing chain in 4mm scale, such as the examples shown in the photographs to retain timber (see Fig. 117) and steel girder loads, on the respective wagons.

However, you can also make use of old necklace chains, which can be picked up very cheaply at second-hand shops. Once washed and tarnished, or even spray painted if preferred, these can provide very realistic loading chains.

Fig. 118 Loads need to be securely fastened to wagons and in the case of the timber plank load, the load has been retained using rope formed from twisted threads.

Fig. 119 For heavier and more substantial loads, chains are required. In model form these have been modelled using fine thirteen links to the inch chain available from a number of modelling suppliers.

Tarpaulins

Tarpaulins can be either made or bought ready formed for use in 4mm scale. I have used the tarpaulin sheets produced by Roger Smith, which are a good way of representing a loaded wagon without having to make a load to fit the wagon. It also allows you to put additional ballast weights in the wagon under the tarpaulin, if desired.

If you cannot get the correct tarpaulin sheets for your models or you want a cheaper alternative to buying ready-made ones, then you can always make your own. This can be done in a number of ways using tissue-type paper, coloured and lettered to the correct detail for your period.

The method I prefer for making tarpaulins is described below using tissue paper collected from all sorts of packaging, particularly the sort you get when buying china or glass, as well as the new tissue you can buy from any stationers for wrapping presents.

First take a sheet of tissue paper large enough to make at least one wagon sheet plus an extra centimetre or so around the edge. Select the colour of the sheet that you want – I chose a dark charcoal grey (Humbrol Enamel Matt 67) and using a reasonably large modeller’s brush (No. 5) apply a coat of paint to one side of the sheet of tissue paper, with strokes working on one direction across the sheet. Do not be too fussy about brush strokes, or if the paint does not quite cover the entire sheet.

Fig. 120 The use of tarpaulins was once widespread on open wagons. The GWR Open A wagon fitted with a sheet rail has been covered with a weathered wagon tarpaulin produced by Roger Smith. The securing ropes have been formed from twisted threads.

Fig. 121 The LNWR open wagon is loaded and covered with a homemade tarpaulin sheet formed from painted tissue paper. Here again, the tarpaulin is secured with ropes made from twisted thread.

Set the sheet aside to dry thoroughly for at least twenty-four hours. Turn the sheet over and then paint the other side in the same manner, but with the brush strokes at 90 degrees to the direction of brush strokes on the first side. Again do not be too fussy about streaks or brush strokes as this all adds to the effect of a weathered and heavily used tarpaulin sheet.

Leave the second side to dry for at least twenty-four hours before thinking about any further coats of paint, although I have found that a single application of paint per side was sufficient. When the paint has dried, add any numbering or letterings as desired using decals or drawn by hand. In the example shown here, I opted to leave the sheet blank.

Whether you make your own or buy ready-made tarpaulin sheets, each tarpaulin looks more realistic if it is then gently scrunched up then folded out again to represent a used sheet, prior to fixing over the wagon body using thread as rope ties, forming ropes as described earlier.

The tarpaulin can be applied directly to the wagon sides or you may wish to add a ‘load’ under the sheet that sits proud of the top of the wagon sidewalls. To form the load under the sheeting in the example shown, I used pieces of thick card folded and fixed to the bottom of the wagon with glue. Once the load has set, take the tarpaulin sheet and fix with PVA type glue to the top surface of the card load and leave to dry before progressing further. Check before fixing that the tarpaulin sheet will extend to the wagon sides when folded down around the load and adjust as necessary.

When the sheet is securely fixed to the load, work your way around the wagon, folding the tarpaulin sheet around the load and then, using the same glue, fix to the wagon body, starting with the long sides first, before fixing to the end walls. It is useful at this stage to have a photograph of a wagon loaded and covered with a tarpaulin to show how these covers were placed over the loads, folded at the corners and tied in place. I then used short pieces of khaki cotton thread to represent ropes between the sheet and the wagon body, copying the pattern of tying from pictures of the prototype.

READY-MADE WAGON LOADS

A number of suppliers, such as Ten Commandments, Dart Castings and others, provide a range of ready-made wagon loads in resin, plaster or white metal that can be painted as required. These ready-made parts are a good way to save time in making things for your model railway and for making a wagon load that maybe is a bit more complicated to fabricate. The quality of the products is generally very good, with little need to clean up flash before priming and painting.

The only down side to this approach is that these items tend to come at a cost, which if you are working to a tight budget may be prohibitive. In this instance, using your imagination and a bit of wood or modelling clay you can create a wide variety of objects to represent wagon loads, as well as be creative.

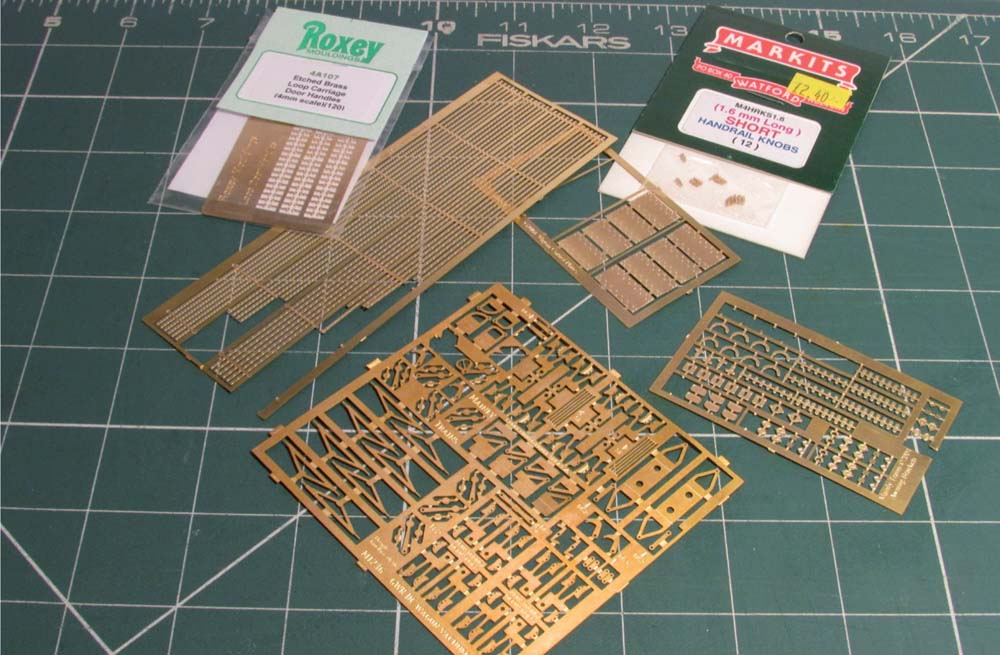

WAGON DETAILING COMPONENTS

Although the quality of wagon kits supplied today is generally excellent, on some of the older kits the detail of the moulding is limited. For those that like the minutiae in fine detail, or when scratch building, it is possible to obtain detail kits, generally brass frets, covering all sorts of fine detail items to adorn and enhance your kit, RTR model, or scratch build project.

Some examples of the types of components that can be obtained include riveted wagon strapping, corner plates and maker’s plates, as seen in Fig. 109. The use of these components is best done by reference to prototype photographs to show location and layout. The use and fixing of these types of components has been described earlier in this chapter and in more detail in Chapters 6 and 7.

WEATHERING

The subject of weathering can be, and has been, the subject of complete books by others more competent than I in this area of modelling and I would refer you to some of these other texts for detailed accounts of weathering techniques, paints, powders and other weird and wonderful techniques for turning your pristine models into replicas of the real world rolling stock.

Suffice to say that I do not personally weather my models particularly heavily, if at all, as I prefer the out-shopped look to my rolling stock, with perhaps just a very light weathering on the underframe. To achieve the look I want, I use dry brush techniques utilizing various enamel and good quality acrylic paints to get the subtle tones. To get the right effect it is advisable to work from a photograph of the prototype to observe the distribution of the weathering effects across the wagon. In the application of dry brush techniques, I use very little paint and work a little bit at a time to see how the effect develops on the wagon.

USEFUL SOURCES OF MATERIAL

When looking for parts to detail your kits, RTR or when scratch building, there are many useful sources of materials for detailing without spending a fortune. This is starting to verge on scratch building, which is discussed more in Chapter 6, but I have included some discussion here as it refers specifically to detailing of wagons.

By way of an example, one excellent source of fine brass-coloured wire is the wire mesh that can be found around wine bottles, in particular, certain brands of Rioja and Chianti wines. This is a good excuse to buy a bottle or two, consume the contents with dinner, then after dinner spend an hour or two carefully unwinding the wire into a single coil for re-use. This material is great for making fine pipe-work; for example, as used on the Cordon Gas Tank wagon or for door bolts on the Siphon F wagon, both of which are described in more detail in Chapter 7.

Another extremely useful source of material for detailing is staples, available in various sizes and can be used as a cheap material for a number of uses. For example, I have used staples bent and reshaped to represent handrails and grab handles on wagons, coaches and scratch built narrow-gauge locos.

APPLICATIONS TO YOUR RTR FLEET

The detailing methodologies discussed in this chapter have been primarily aimed at working with wagon kits. However, there is absolutely no reason why these detailing techniques could not also be applied to detailing RTR models to make your rolling stock fleet that bit more unique.

If you are a bit uncertain as to whether you want to start work on your pristine and carefully assembled RTR rolling stock collection, why not buy a cheap, old, second-hand wagon from a show sale stand, or on-line, and use this as a test bed for ideas and practising your techniques. If it works, then great – you have breathed new life into an old model; but if it does not work, then at least you will not have damaged that expensive new rolling stock!