WHY SCRATCH BUILD WAGONS AND VANS?

This is a common question, as I have already discussed in Chapter 1, especially when you consider the wide variety of models and kits available to the railway modeller from the industry today. However, no matter what the range of RTR and/or kit wagons on offer, there is always going to be a specific prototype variation or special wagon that a modeller would like, which is not covered by the range of kits and RTR wagons on offer. The more specialized or obscure the prototype requirement, the greater the likelihood is that there will not be a model readily available, as the market will be so small as to not make it financially viable to produce a RTR model or commercial kit.

Scratch building can, therefore, be considered as the next logical step after kit conversion or RTR conversion, in that search for modelling something that little bit different. The driver to move down this route will be the desire to create a specific prototype or less widely modelled version of a more common prototype. At some point you will need to decide what you think you are able and can achieve through conversion of a kit or RTR model. You need to recognize that beyond that point it is likely to be more efficient and easier to achieve the model that you wish to create by starting completely from scratch.

This decision will partially be guided by the level of confidence that you have in your ability as a modeller to either build from scratch, or use an existing kit, or RTR model, as the basis for the project in hand. The time to undertake the work, the degree of accuracy you want to achieve and how much you will need to or, perhaps more importantly, be willing to compromise, also need to be considered in the decision-making process.

To scratch build a wagon or van, will very likely take you more time than if you were putting together a kit, or converting a RTR model. But the opportunity is there for you to create a model with fewer compromises having to be accepted; it will also allow you to produce something that may be unique to your prototype era/region/operation, and these may be the deciding factors. It is also linked to your confidence in your level of skill and ability as a modeller, but without giving it a go you will not know whether it is within your grasp or not.

SELECTING THE PROTOTYPE

Selecting the prototype that you want to model as a particular project will depend on your own personal preferences – there is no one reason for considering scratch building. Some will decide to go this route because the particular prototype is not available in RTR or kit form. Others may decide to go down this path to create a model of a prototype that is to a higher level of accuracy than that available from a RTR model or commercially available kit. Another reason is to create a wagon that is specific to a particular period or subject matter. The decision-making process guiding the selection of your prototype as the subject of a scratch building project is, therefore, subject to numerous variables and no two situations are likely to be the same.

In my case, it was the desire to create some examples of rolling stock that were not readily available as kits or RTR models. I chose to model particular prototypes because either they fitted with the period and location that I was trying to create on my layout, or I wanted to have something just that little bit different. These tend to be the overriding motives behind getting me started on scratch building rolling stock.

Having made the decision to want to model something a bit different, I then spend many hours browsing through my collection of books, journals and magazines, as well as sources of information on the internet to see what would take my eye. There is no particular formula to this process – it is largely governed by whatever catches my attention during the review of the sources of information. For example, the first piece of scratch building that I attempted, in terms of railway rolling stock, was the creation of the GWR Cordon Gas Tank wagon, about which I subsequently wrote a short article that was published in Railway Modeller (Tisdale 2010a). An expanded and more detailed description of the construction of this scratch built wagon has been included in Chapter 7 for reference.

Fig. 211 Scratch building wagons allows you to build something that may not be available RTR or in kit form. This example of a scratch built GWR gas tank wagon was a first attempt at scratch building.

RESEARCH

Once your subject matter has been selected, the next step is to undertake research, to obtain as much information as you think necessary to enable you to build the model of the prototype. As with the selection process, the amount of research you choose to do is down to personal preference – there is no right or wrong answer as to how much is correct.

On the basis of my experience, my advice would be that research is the key to the process and is highly recommended as a ‘must do’ activity before starting any project of this type. The more information that you collect, the better – there is no such thing as too much information. The basic requirement will depend on the subject matter being tackled, but the key elements are a scaled line-drawing for dimensions and photographs of the completed prototype wagon as the built wagons often did not adhere to the line-drawing in practice. Ideally, the photographs should date from the time period that you wish to model it, as changes to wagons were made during maintenance and adaptations occurred over the years in service to meet the requirements of the time.

The more photographs available of different sides, angles and close-up of key details, such as brake gear and underframe, the better but is not essential. I have found that in many cases good photographic records can be found for the newly built and out-shopped wagon, but trying to model a prototype in service does tend to require more filtering through dozens of photographs of passing goods trains, goods yard shots and sidings to identify what a particular wagon looked like in day to day operation on the real railway.

As I am reviewing the text and photographs of the selected subject, I find it useful to make notes on the shapes of key elements of the structure of the wagon and, where possible, I also try to estimate dimensions of the wagon or particular features of the wagon, to compare with line-drawing dimensions, where available. To do this I use other items in the photographs for approximate scale if there is no scale drawing available. As well as the overall shape and size of the wagon, I also look at the layout of the lettering, numbers and any special notices and note similarities to other prototypes.

I look at the buffer type and pattern shown in service to see whether that differs from the official drawings, as well as the brake gear layout. Identifying the types of wheel used on the prototype is also important to replicate on your model; for example, the use of open or closed spoke wheels or three-hole disc wheels. Where bogies are present, I look at the type of bogie, the size of frames, the types of wheel and also the braking arrangements and location of brake levers.

All of this careful study and note-taking is carried out so that I can assess what components I am able to fabricate from raw materials, such as sheet brass, plasticard or wood, what parts I can modify from my stock of spares hoarded from the construction of previous kits and then determine what parts I might need to procure from a specialist supplier.

As part of my research, I use the internet to search for images of the prototype and to see if there is any reference to a kit in a different scale or gauge to that which I model. Looking at kits in other scales can be a useful guide to understanding how to put a scratch built model together to resemble the prototype and to show what level of detail might be attainable in model form.

I have a collection of books about the railway company and the period that I am particularly interested in from a modelling perspective. I have found that reviewing a wide range of books about the same railway company can provide all sorts of useful information about how the company was formed, developed and was run, and can also help to provide a ‘feel’ for the way that the company operated and how it used its rolling stock in its day to day operations.

Sources of data that I have found extremely useful and that can be used for a wide variety of railway prototypes include archive collections on-line; for example, The Great Western Archive (www.gwr.org) or The LMS Society (www.lmssociety.org.uk) provide modellers of these railway companies with an invaluable source of data. In addition, there are the more traditional physical collections held by museums and railway preservation societies that may be available for consultation.

There are also numerous factual text books that can be referenced on just about every main UK railway company, ranging from pre-Grouping, Grouping, Nationalization, Sectorization and subsequent Privatization, as well as most of the constituent companies that went to make up the big four at Grouping in 1923. The resource base is potentially huge and I would recommend that some consultation with these resources should form part of your research activities.

As part of the research and planning process for scratch building, I have also found that it is extremely useful to write out the potential construction steps that you plan to make for the construction of the model. At the same time, it is also prudent to think through the process of how the parts are going to join together, as this will determine your selection of materials for the project. There is no big secret process or skill here; if you have made plenty of model kits, you will have developed the knowledge and skills of understanding what will work in the scale you are modelling in and what will not work.

This process of planning how you are going to construct the model is particularly relevant when you are considering building either open wagons or vans. For example, when building a covered wagon or van, it means that you can be less concerned about what it looks like inside or too concerned about scale thicknesses for the sidewalls, as this detail will be hidden by a cover or roof. By contrast, with an open wagon, the interior detail is equally important as the exterior and one of the main considerations is that the sidewall thicknesses need to ‘look right’, as illustrated in Fig. 212.

Fig. 212 The wall thickness on open wagons is something that needs to look right when scratch building. To achieve scale wall thicknesses on this open wagon two layers of thin plasticard were laminated to provide strength.

The skills developed through building wagons and vans can also be applied to other rolling stock, such as coaches and locomotives. The process of carrying out research and thinking through the method of construction, as well as making notes on construction sequencing, are all relevant skills for building all sorts of subjects, not just rolling stock for your railway.

MAKING A START

Having carried out all of the research and decided on what you want to build, the next stage is to decide on whether you can achieve what you want from modifying a kit (kit bashing) or whether you wish to build from scratch. To some extent this will be governed by your willingness to accept compromises in the construction process or whether your goal is to achieve 100 per cent perfection and representation in exact scale of the prototype you are looking to reproduce.

Once you have decided that scratch building is the way forward, your first task should be to work through your notes and compile a list of components and materials that you will require to complete the project. It is better to carry out this process before you start any building, as it can be extremely frustrating to get to a key stage in the build and then realize that you are missing a critical component.

Fig. 213 The spare parts’ box is an essential component of the modeller’s tool bench, with a wide variety of small parts kept ready to hand.

Fig. 214 As well as hoarded parts from old kits and a supply of small components, items such as bogie kits and spare floor and roof sections also prove useful.

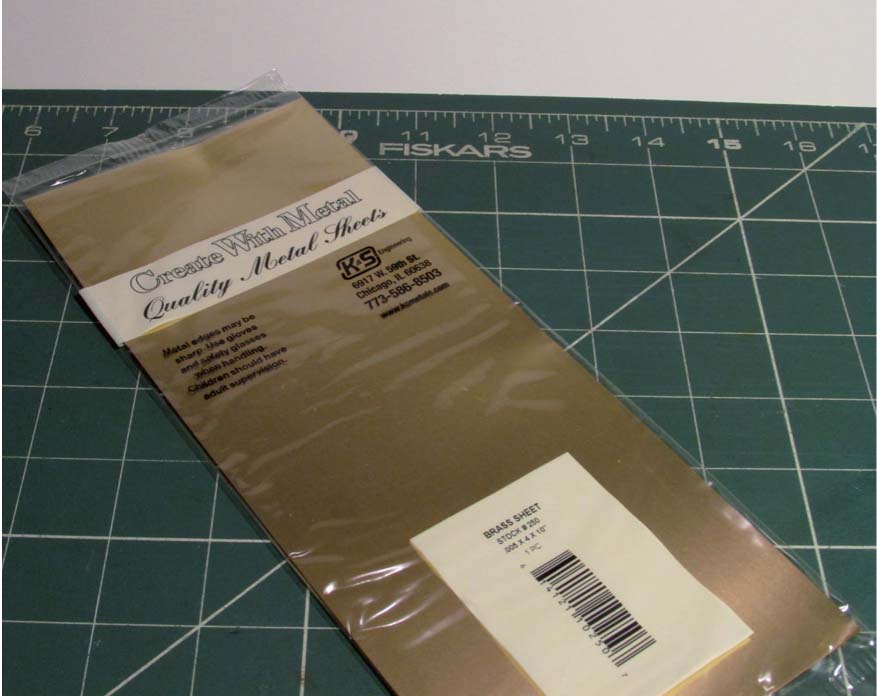

Fig. 215 To form van roofs when scratch building, the use of brass sheet provides a strong and sturdy roof, provides weight to a plastic model and all achieved at scale thicknesses.

Fig. 216 A selection of specialist white metal parts, such as buffers, vacuum pipes, brake cylinders, brake levers and coupling hooks is useful to have in stock before starting any modelling project.

To avoid this problem, I like to keep a stock of standard parts, such as the various common patterns of buffers, vacuum pipes, coupling hooks, vents, brake gear and brake levers, that I will likely need for the prototypes of the period and railway company that I model. I also keep a box of spare parts harvested from kits and a selection of useful materials such as plasticard in various thicknesses (most commonly 10thou, 15thou and 20thou), a selection of microstrip, plastic rod, fine wire and 10thou brass sheets. A stock of replacement wheels (I prefer to use Gibson OO fine-scale, but other makes are available), brass bearings and couplings are also extremely handy, as these can take time to arrive in the post if you have to order and you have no local model shop.

Once you have all the parts and components that you think you need, I have found it extremely useful at this stage to prepare a list of construction steps, similar to the instructions that you find with some kits, so that you can think through and write down how you are going to make something. This is the time when you can do trial dry runs of some of the key stages of assembly to check that what you think might work will actually work in practice.

I like to make some rough sketches as well, when I have tried the dry runs, to show key details; you may also find this a useful tool. These do not have to be high-quality pieces of artwork, as long as they mean something to you as the builder. As well as providing a useful aide-mémoire to the construction process, by writing the steps down, making a few sketches and adding to these notes as you work through the build, you will have an invaluable record of what methods and materials worked for future reference on other projects.

When you are sure that you have all the necessary parts and materials, and you have your notes on how you plan to make the model, then it is time to begin the construction process. I have found that the best place to start with wagon building is by forming the body and ensuring that this is square and level before adding the underframe. I then build the underframe to match the dimensions of the body. The sole bars and axle boxes can be added next and checked, using the wheel sets, to ensure that the axle alignment is perpendicular to the sides of the wagon and that the wheels run freely in the chassis.

Once the basic structure is completed, it is then time to move on to the addition of the detail components. With the construction of vans, I prefer to leave fixing the roof in place until the body work has been painted and decals applied accordingly. The fitting of fine detail parts and, in particular, fragile detail parts should be added as late as possible in the construction process to avoid the risk of damage from handling the model during construction.

With some subject types, it may be possible to break the construction of the wagon down to a series of sub-assemblies. This allows sections of the wagon to be built in isolation, including possibly some of the painting and fine detail work, before bringing the sub-assemblies together to complete the whole prototype. This sub-assembly approach is a good way of breaking down the work into manageable sections. These sections comprise work that can perhaps be achieved in one or two working sessions and avoids the risk or temptation to rush to complete something.

Using my first attempt at scratch building an OO gauge wagon as an example, having seen the type of wagon I wanted to build, the first task was to decide how to build a reasonable model in 4mm scale to represent this part of the everyday life of the railway. For the construction of my chosen subject, a Great Western Railway Cordon Gas Tank wagon, I started playing around unsuccessfully with various pieces of card and wood to try to obtain a satisfactory tank-like structure to the correct size.

The results were not particularly good and I subsequently identified, from browsing the internet, the ‘N’ gauge kits produced by PECO, specifically the kit for the 10T tank wagon (PECO ref: kNR-167). A quick comparison of the size of the tank in the kit with the dimensions of the tank type I wanted to build for the gas tank wagon, indicated a favourable fit and two kits were duly purchased. (A more detailed description of the creation of this model is provided in Chapter 7.) What this example shows is the need to have a clear understanding of what you are trying to build and to keep an open mind when looking for a source of materials for the scratch build project.

VISUALIZATION AND MOCK-UPS

One of the techniques that I make use of when making models from scratch, is to visualize what the final model will look like and, where necessary, to try out methods of construction using mock-ups. The idea is to get a good clear understanding in your mind as to what you are trying to achieve in model form before starting. This visualization process can be extremely useful and in the past I have made mock-ups of parts of a model that I am trying to build in order to see how it might go together and which material type would be the best for the task in hand. You may wish to consider this as a useful strategy for particularly complicated elements of a model, as the outcome of making a mistake with the mock-up is only some used card that can be recycled rather than using up more expensive brass sheet or plasticard.

In some instances it may also be possible to create a ‘production line’ for the fabrication of similar parts so that you can bring some degree of consistency to the production of parts and so that you do not have to spend time re-learning how you made something several times. Start by collecting together all the individual components (such as buffers, etc.) and materials (such as plasticard, brass sheet, etc.) that you will likely need, even to the point of considering different materials for each element to be built.

The whole process of making mock-ups allows you to assess whether your planned approach will work. It allows you to see whether it is possible to actually make something representative in model form and perhaps, most importantly, to determine whether it will be possible for the completed model to operate on your layout. This is where compromises in detail or accuracy may have to be considered in your model. For example, the ability of the finished model to negotiate the radius of curves on your layout and the coupling methods used for your rolling stock, to name but two, place constraints on the operation of the model that you will need to consider, unless the plan is to create a model that is just going to sit as a static display!

WALLS ON WAGONS

Forming the planking to represent wooden-bodied wagons and vans can be achieved in a number of ways. If you are considering plasticard as the basis for your scratch building, then you can consider using embossed plasticard, or form your own using plain plasticard. Various manufacturers produce plasticard that is embossed to represent wooden planking, which can be adapted to give a reasonable impression of the wagon body. However, the key issue with using this type of product is that the planking is generally all regular spacing and size, which if you compare to a typical railway wagon is not always the case.

Fig. 217 Visualization and the creation of mock-ups when scratch building is a useful method to adopt to save wasting expensive materials. For the creation of a non-standard bogie, a card mock-up of the bogie frame and stretcher has been created before starting in brass section.

Fig. 218 To achieve scale wall thicknesses, laminated layers of plasticard provide strength to the open wagon. The outer plasticard overlays can be scribed with wagon planking and location of doors, corner plates and bracing strips marked from line-drawings.

An alternative approach would be to consider using a base layer of plain plasticard to form the basic shell of the wagon, on to which you can put overlays of either individual planks, or an overlay of the entire wall, with the planks scored onto the sheet to match the line-drawings of the wagon being modelled. The use of individual overlays for each plank would be a fiddly process and requires high levels of patience, but is likely to give the best effect. An overlay for the whole wall with scored planking to match the line-drawing would be quicker and less wearing on the patience and is the method I adopted for the construction of the GWR bogie open wagon described in more detail in Chapter 7 and shown in Fig. 218.

WAGON FITTINGS

After forming the basic structure of the wagon, the addition of detail wagon fittings brings the model to life as a representation in model form of the prototype. Detail components in brass, white metal and plastic are available from numerous suppliers for use by the scratch builder, or you can fabricate your own components from raw materials to meet the specific requirements of your project.

As an example of forming components from raw materials, the formation of door bolts, hinges and latches can be represented using scraps of plasticard, waste brass from frets, wire or white metal scraps recovered from cleaning the flash of cast components. All of these materials can be suitably shaped with a bit of imagination and careful crafting, and then fixed in place on your model.

The use of raw materials or pre-formed detail components depends on your requirements for the degree of accuracy and is the choice of the modeller. If the finished model is to be viewed from a distance of several metres on a layout, then the level of accuracy may be less important than if the model is for static display on your desk or museum display cabinet.

Fig. 219 On a van scratch build project plasticard microstrip has been used to form the doors, door hinges and bracing strips. Fine wire has been bent to shape to represent the door bolts.

To form door hinges on the model of the GWR Mink F van described in detail in Chapter 7, I used oblong-shaped scrap pieces of plastic microstrip, carefully folded over the door edge, as shown in Fig. 219. To form the door bolts on the same model, I made use of fine wire recycled from Rioja wine bottles, suitably bent to shape and attached with cyanoacrylate.

Another example of a common wagon fitting is the presence of bonnet vents. Bonnet vents were used by many railway companies in the design of the end walls of vans to provide ventilation. These vents can easily be recreated in model form from either two small triangle shapes cut from 5thou plasticard for the ends and a flat section cut to size from the same thickness plasticard overlying the triangles, or a single piece of 40thou or 60thou plasticard cut to the correct overall size and then carefully sanded to a cheese-wedge shape, before fixing to the end wall of the van.

A further example of a common fitting is the use of angle iron bracing for the wagon walls, used on both vans and open wagons. To detail your model, these can be formed in one or two easy ways. One way is to take some appropriately sized pieces of microstrip and first form the horizontal section of angle iron on the wagon wall. Then take a second piece of the microstrip and fix to the first piece but at right angles, so that the microstrip extends perpendicularly out from the wall of the wagon, as shown in Fig. 221. This can be a fiddly task, but with patience can produce excellent results, as shown in the example of the short cattle wagon conversion described in more detail in Chapter 5.

Fig. 220 On the end of the van, ‘T’ shaped plasticard microstrip has been used to form the bracing. The bonnet vent has been formed from a single piece of 40thou plasticard sanded to a wedge shape before fixing.

The second method of forming the angle iron bracing is to procure some of the fine detail extruded plastic ‘L’ section available from a number of suppliers. This is just cut to the correct length and fixed in place with minor fine adjustment with files or fine-grade sandpaper. I used this method with fine ‘T’ section extruded plastic section in the construction of the GWR Mink F bogie van described in more detail in Chapter 7 and shown in Fig. 222.

Fig. 221 A scratch built open wagon finished off with etched brass corner plates and plasticard microstrip used to form the angle iron bracing.

Fig. 222 Plasticard microstrip is available from a number of suppliers as flat strips, but also in many different shapes to aid the scratch builder. Extensive use of pre-formed ‘T’ section microstrip has been used on the van model to represent the angle iron of the prototype.

FITTING FRAGILE PARTS

When building wagons and vans the application of fine detail parts will, at some stage, mean that a true scale representation of these parts in 4mm scale will result in potentially extremely fragile components.

Making rolling stock that will be placed on a permanent layout and that will not get handled frequently, if at all, means the level of fine detail and representation of this as fragile parts is less of an issue. However, this does become a significant issue if you are making rolling stock for use on an exhibition layout or a temporary home layout, where there will be frequent handling of stock, transferring items from storage cassettes or boxes to layout and vice-versa.

It comes down to the practicalities of moving rolling stock and your acceptance of a compromise in the use of fragile parts in the final model driven by your planned end-use. This does not mean that rolling stock used on exhibition, or temporary layouts, should be devoid of detail – far from it, it is just a fact to be recognized that there is a greater risk of damage to the rolling stock when it is being regularly removed and placed on layouts or storage trays.

To reduce the risk of damage you can look to reduce the level of fragile parts by fabricating in such a way that the parts are supported by sections of the model, or by incorporating detail elements in with larger component parts and not as separate items. For example, where fragile parts, such as brake levers and tie rods, are included in your models, it might be sensible to consider only fitting them to the model at the end of the construction process and to fix them so that risk of damage is minimized. With Morton brake levers this could be accomplished by thickening the ratchet at the handle end so that it can be fixed to the axle box and the sole bar to reduce the potential for it to be knocked off or damaged through handling.

SCALE THICKNESES

In 4mm scale, 4mm represents 1ft in the real world! A statement of the obvious I know, but the number of times I have seen railway models with over-thickness parts, not just on rolling stock, but also in scenery and buildings, suggests that this is a common issue and likely to be a fault in the selection of the most appropriate material type for the job at hand.

Specifically, with respect to rolling stock, a typical plank width used on an open wagon was approximately 6 to 7in, but with some variance by railway companies and by use of wagon, between 4 and 9in. At 4mm scale, the plank size compromise would be to use 2mm for the average plank width on a wagon or van. For open wagons, the thickness of the planks, and thus the thickness of the sidewalls, varied, but typically the planks were between 2 and 4in, equating to between 1 to 2mm in 4mm scale (OO gauge).

To achieve realistic scale thicknesses and to build a wagon that is going to be reasonably robust for layout use needs careful consideration of material type and possible compromises on scale thicknesses. For example, during the construction of the GWR Tourn open wagon, I used 2mm as the average for plank width (on all four planks of the body sidewalls) and used 20thou plasticard to form the basic body shell, with 5thou plasticard for the overlays on which the plank detail had been scored by hand, as shown in Fig. 218. This combination gave a sidewall thickness of between 1 and 2mm. The model has proved to be robust and after a couple of years in use on my layout shows no sign of bowing of the sidewalls.

To provide some assistance, and as a point of reference on scale thicknesses, in Appendix I I have produced a table of the more commonly used dimensions scaled for modelling, including some common wheelbase and wagon body sizes.

MATERIAL CHOICE

It is important to consider how you choose the right material types for making components. The choice of material type has implications from a number of perspectives. The type of material can influence how components are made and can be fixed together, as not all materials can be used for the same component, as we have seen in Chapter 2 on the discussion of the relative merits and limitations of material types. The choice can also be driven by what the modeller feels comfortable working with, as well as what may already be available from the proverbial spares’ box or workbench.

By way of an example, when making a model of a GWR Mink F bogie goods van, it was noted from the scale drawings and photographs of the prototype that the van body was made from iron and that the end walls curved in at least two directions, making the process of fabrication of this part of the body complicated. Furthermore, the drawings and photographs of the prototype showed that the roof profile was relatively thin.

To address these issues in model form, I chose to make the van body from 40thou and 60thou plasticard, as this material was easier to shape to get the curved corners to the end walls and at the same time match the roof arc as per the prototype, as well as keeping the model quite stiff and strong. However, I formed the roof from 5thou brass sheet, suitably rolled to shape, as this is relatively thin and therefore more representative of the profile on the prototype, but this material provides a roof that is stronger than using plasticard at such a thin profile. (A more detailed description and accompanying photographs showing how this wagon was built are included in Chapter 7.)

TYPES OF ADHESIVES

There are numerous types of adhesive on the market to stick pretty much anything to anything. With the variety of material types available for use for model making, it is an essential part of the modeller’s toolkit to have a number of different types on hand for use. Rather than describe all the types of adhesive that could potentially be used for kit and scratch building, not to mention the use of soldering for metal kits, I have decided to only include here some advice on the four main types of adhesive that I find most useful for my modelling requirements. I should point out here that I have no connection to the brands identified below, other than as a satisfied customer of the products used, and, of course, there are other products on the market that will do equally as good a job as the ones described below. As a note of caution, all of the adhesives listed here should be used in well-ventilated spaces, as the fumes, particularly from the first three examples described below, are not really good for your long-term health!

LIQUID POLYSTYRENE CEMENT

For the construction of extruded plastic kits and assembly of plasticard items I always make use of a liquid polystyrene cement. This type of adhesive works by breaking down or ‘melting’ the plastic of the two components where the liquid cement is applied and then, when the two parts are placed together and held in place for a few seconds, the parts bond together to form a strong joint.

For accuracy of placement of liquid cement I tend to favour the ‘Revell Contacta Professional’ product because of the approximately 25mm-long fine-needle applicator. The applicator allows only a small drop or thin stream of liquid cement to be discharged at once, giving excellent control over placement and volume of adhesive used. The long fine-needle applicator is also extremely handy for applying adhesive in difficult to access locations, particularly when applying additional adhesive on joints to strengthen them.

Fig. 223 The use of a varied selection of material for scratch building necessitates the use of various specialist types of adhesive, such as impact adhesive, PVA, super glue (cyanoacrylate) and liquid polystyrene cement.

ALL-PURPOSE ADHESIVE

For other types of plastic that cannot be secured with liquid polystyrene cement, as well as for wood and metal components, I use ‘UHU All-Purpose Adhesive’. This type of adhesive is available in squeezable tubes and is more of a gel than a liquid, which can be worked into areas of a model to reinforce joints. I find that this type of adhesive works particularly well where I need to fix components of different material types together and where I need to be able to gently adjust the parts before the adhesive sets hard.

CYANOACRYLATE ADHESIVE

This type of adhesive is available in liquid or gel form and I tend to use the ‘Loctite Super Glue’ brand in liquid form for fixing all sorts of metal and plastic components together. As my soldering skills are not of the highest standard, I prefer to use this type of adhesive to fix brass kits together. The adhesive works extremely quickly and has to be handled carefully to prevent sticking your fingers together.

I have found that the best way to use this type of liquid adhesive is to have a small block of wood into which I have created a shallow hole with a 10mm diameter drill bit. This hole acts as a temporary reservoir for the adhesive and I apply the adhesive to the model using a thin piece of wire, which in my case is a straightened metal paper clip.

From experience, the adhesive works best if you apply a few small drops or thin smear of the adhesive to the parts to be fixed together, then press and hold together the parts for approximately 10sec. The parts should be securely held together after this time, but I then tend to reinforce the joint by using the wire to apply a small bead of the adhesive at the joint and allow the adhesive to be drawn into the joint by capillary action. The joints usually set within a few seconds, but left for twenty-four hours, the joint should form a strong bond.

POLY VINYL ACETATE ADHESIVE (PVA)

Whilst the use of PVA glue might not immediately spring to mind as a useful adhesive for rolling stock modelling, I use this type of glue for a number of tasks where the other adhesives discussed are not appropriate. The first use is for fixing together wooden components or parts for wagon loads. As wood is absorbent, I find that the use of PVA through a fine applicator nozzle on the glue bottle can be very effective for fixing wooden parts together or for fixing wood to plastic. The PVA takes up to twenty-four hours to fully harden off, so you also have time to make any adjustments to the parts before the adhesive sets.

The second use of PVA is for fixing glazing to brake vans, horse boxes, etc., because the adhesive dries clear and does not leave an opaque residue on the clear glazing sheet.

The third main use of PVA is related to the formation of wagon loads, tarpaulin sheets and their tie ropes formed from thread. For the formation of the coal loads described in Chapter 4, I used PVA to fix the load in place on the false floor and then dribbled diluted PVA/water mix through the ‘coal’ to hold the material in place – when dried it left a shiny sheen on some of the surfaces, reminiscent of real anthracite.

COMMON PROBLEMS

Unless you are extremely lucky, then on a first attempt at scratch building there is always going to be something that goes wrong, such as parts that will not go together properly, or as intended, or the choice of material does not allow you to create a satisfactory representation of the element of the wagon that you are trying to replicate in model form. Some of the more common problems and issues that arise have been tabulated with some comments provided on ways to mitigate the risk of occurrence.

This is part of the learning process; typically, errors or mistakes will occur during the construction sequence when perhaps not enough pre-commencement thinking has gone into the planned sequence of construction. Another common error is when, after construction is completed, you realize that detail parts cannot be easily painted, or they are completing inaccessible for later painting. This emphasizes the points made earlier about planning your work sequence, doing dry run assembly sequences and even considering the use of a sub-assembly construction process where practical.

Other problems typically occur around the selection and use of materials, as well as the fragility of components in the construction process. Given the likely desire to create a model that looks and ‘feels right’, there will inevitably be the need at some point to compromise on the level of detail or scale thicknesses in order to reduce the risk of damage to the model, either during construction or later during handling and use on your layout.

APPLICATION OF TECHNIQUES ELSEWHERE

The skills and techniques described in this book have equal application to other types of rolling stock, such as carriage building, which is only a big van with windows, and, to some degree, locomotive building. I have used the skills described here to scratch build four-wheel and bogie carriage stock, a fleet of wagons and vans, as well as locomotives for my OO9 narrow gauge that forms part of my layout.

As well as the use of these skills in expanding your fleet of rolling stock, the skills are also transferrable to the construction of buildings and structures for your layout. For example, I have scratch built a stone and steel girder road over a bridge on my OO gauge layout, using the same principles of research, drawing scale plans for the structure and planning a construction sequence. Another example of where I have scratch built includes the construction of a small Puffer coaster for a harbour scene on a colleague’s extensive OO gauge layout. This ship was constructed as a waterline model, with open hold for loading and was almost entirely made from scrap pieces of plywood, timber, card and plasticard.

A SELECTION OF COMMON PROBLEMS

| Problem | Comment |

| Access for painting detail parts |

● Dry run assembly to check access● Consider painting parts prior to assembly |

| Fragility of parts |

● Consider compromises on scale thicknesses● Consider choice of materials for fabrication● Fitting parts last where possible to reduce risk of damage |

| Parts do not fit together correctly |

● Dry run assembly to check fit● Careful marking and cutting of materials, ‘check twice, cut once’● Selection of material types and correct type of adhesive to join parts |

| Poor running qualities |

● Misalignment of axle boxes, check with wheel sets when fixing prior to adhesive hardening● Use metal wheel sets and brass bearings● Consider use of rocking ‘W’ irons● Twisted bodywork (see below)● Lack of ballast or weight to the model (see below)● Check back to back of wheel sets |

| Twisted bodywork |

● Set bodywork on flat glass surface during fixing, clamp, if necessary● Dry run assembly to check joints |

| Lack of weight to model |

● Add ballast in side vans or under the floor of open wagons● Use of white metal and brass detail components to add weight to the wagon● Use of metal wheel sets and brass bearings |

| Too thick sidewalls |

● Review scale thicknesses and selection of appropriate materials for components |

| Model does not look right |

● Proportions incorrectly interpreted from scale drawings and photographs● Consider mock-ups to check dimensions and scale of components |

| Detail does not show after painting |

● Too heavy paint application – consider alternative paint application techniques● Consider over-emphasizing detail to allow for painting |

Fig. 224 Scratch building techniques described here for OO gauge have wider applications, an example of which is this selection of narrow gauge (OO9) coaches built from parts of old Ratio coach kits, card roofs and plasticard end walls.

CONCLUSIONS

The critical aspect of the scratch building process is patience. Do not rush, make sure you do dry runs, then critically review and do not be afraid to reject something, as you may regret that later. As those of a certain age will no doubt remember from their school days, ‘measure twice and cut once’ is a useful principle to adopt in your model construction and avoids frustration and the waste of materials.

Unless your model-making skills are exceptional, do not expect to make your first scratch build project without making mistakes or having to throw some element into the bin or recycling box.