READY-TO-RUN OR BUILD-YOUR-OWN?

Given the quality of OO gauge ready-to-run (RTR) models available today from the likes of Bachmann, Dapol, Heljan and Hornby, where the level of fine detail is excellent, you might well ask why build your own rolling stock? You might also question as to whether you can achieve the same level of detail, running quality and overall finish to the model as can be achieved by the commercial manufacturers.

The answers depend on the level of skill and patience applied to the process. For me, the development of skills with practice gives me a great sense of satisfaction, when I have created something myself, rather than buying it from the shop, lifting it out of the box and playing with it. It is a sense of achievement to create something and, in my case, I enjoy striving to produce as high a quality model as my limited skills afford.

I have been asked a number of times over the years as to why I should want to build my own rolling stock when, especially in the last five to ten years, the quality of the RTR models on the market is very good. The answer is, I think, that it is the desire to create some examples of rolling stock that are not readily available as RTR models and the desire to have something just that little bit different or unique running on my layout.

TRAIN SET TO MODEL RAILWAY

Many of us, I am sure, will have been initiated to the hobby by the childhood train set as a Christmas or birthday present set on a flat board, with a loco and a couple of carriages and wagons trundling around in a circle. If you were very lucky and had the space, you may have had the opportunity to construct a more extensive train set in a spare room or loft. Over time this develops with the addition of more track, sidings, maybe some buildings and the start of scenery, and very soon the train set starts to become a more serious model, which could be termed a model railway layout rather than a train set. Maybe as one develops from a train set, the application of additional details – loads for wagons, weathering, etc. – to RTR items is the first step down the road to building your own rolling stock.

The first step commonly taken after the train set stage is to look to build a layout that is a little more realistic, or representative, of your chosen railway company, geographical area of country, or specific operation or activity served by a railway. It is at this stage that it usually becomes apparent that the rolling stock produced by the RTR manufacturers might not meet your requirements.

The RTR range of models may not have all the necessary examples of rolling stock that would be relevant to the period being modelled, the area that you are trying to create or a specific industrial use, and thus kit building becomes the favoured option. In fact thinking about it, the next logical extension of the development of your model railway after creating the scenery, permanent way and buildings or structures, is to put your own interpretation and skill in to the rolling stock to run on the layout.

The model railway press regularly includes articles about building kits, converting ready-to-run models and scratch building rolling stock, and these can be a source of inspiration and guidance for those considering undertaking any of these projects.

BUILDING YOUR OWN ROLLING STOCK

In the following chapters I will consider the options available for building your own rolling stock, in the case of this book in terms of OO gauge, although the ideas and techniques discussed in this book can easily be applied to any scale/gauge combination. I have myself applied this to N gauge, OO9 and O-16.5 scale modelling, having built kits and scratch built rolling stock in all three of these scale/gauge combinations, using skills that I have learnt from my OO gauge modelling.

Before diving into the construction of kits, I will look at the selection of material types and some basic tool requirements in Chapter 2, and will provide some guidance as to what different material types can be used for different modelling tasks and what tools you should consider purchasing before embarking on creating your own rolling stock. Once you have assembled a basic toolkit and a supply of materials, component parts and kits, it is then time to begin.

KIT BUILDING

In Chapter 3, I will show, using worked examples, how you can move from building simple kits to more complicated kits in a variety of material types, including plastic, white metal and brass, similar to the range of kits shown in Figs 1 and 2. kit building may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but if you have the basic skills from putting together a model plane or tank kit, such as those produced by Airfix, then this need not be seen as a huge step up in ability.

Kit building provides the opportunity to develop and hone your modelling skills using commercially produced kits, typically in plastic (see Fig. 3) or metal (for example, white metal or brass) to develop your rolling stock inventory, as shown in the examples in Figs 4 and 5. Other examples of materials less commonly used for kits, including wood and resin, are discussed in more detail in Chapter 2.

Over time and with experience it will become apparent that even kit building has its limitations. This will be even more apparent if your chosen prototype era, locality, line-side industrial use or railway company is not one of the more widely known or supported examples in terms of trade suppliers of kits and components.

Fig. 1 Some examples of plastic wagon and van kits available for the modeller as currently produced kits or available second-hand.

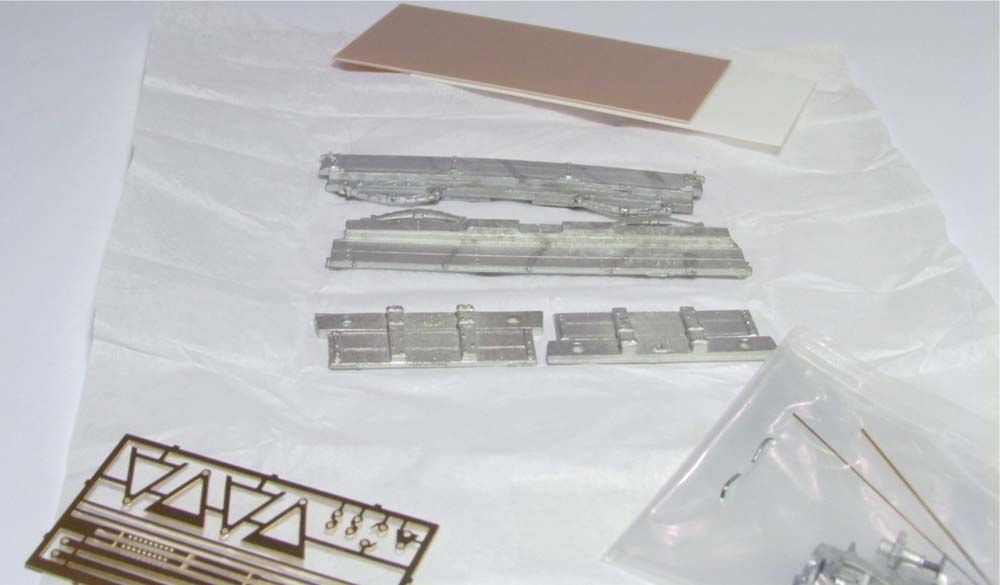

Fig. 2 Examples of etched brass kits currently available for the modeller to build, or use as replacement parts to plastic kits.

Fig. 3 A typical example of an extruded plastic wagon kit, in this case requiring the modeller to provide paint, decals and wheels to complete.

Fig. 4 An example of relatively simple white metal open wagon kit, with etched brass fine detail components and plasticard sections for the floor.

Fig. 5 Etched brass wagon kits available from manufacturers such as Falcon Brassworks, are typically provided with white metal components and for the modeller to provide wheels.

KIT DETAILING AND CONVERSION

The next logical step after kit building is to detail and convert (often referred to as kit bashing) existing kits and then to consider the ultimate in rolling stock construction: scratch building. So what is kit conversion and scratch building? Well kit conversion, I would define, although I am sure not all would agree, is where you take an available model kit similar to the prototype you are looking to create and then modify it significantly to produce a model of the exact prototype you wish to create.

This is different from detailing a kit where you are sticking with the original prototype on which the kit is based and maybe adding additional details that the kit does not include; for example, fitting the correct pattern of wagon buffers (a common problem in some commercially produced kits) or adding wagon loads and tarpaulins.

Fig. 6 Adding detail to a plastic van kit, including the underframe and brake gear as shown here, greatly enhances the basic kit.

Fig. 7 Using a variety of materials, including brass sheet, plasticard and wire, it is possible to scratch build a reasonable representation of a bogie goods van.

In Chapter 4, I will look at detailing kits, working through an example of what can be achieved with detailing a van kit (see Fig. 6) and I will provide hints and tips as to what may or may not be possible. I will also look at the creation of different types of loads for open wagons and how these can be covered and secured.

In Chapter 5, I will discuss the options available for the conversion of kits, as well as the possibilities for converting RTR models, using some worked examples of conversions that I have carried out, to provide a guide to the possible methods and techniques that can be employed.

SCRATCH BUILDING

Scratch building is another area where there is likely to be some dispute over the definition, so to avoid controversy and protracted debate, I will provide my own definition here as the basis on which this book has been put together and leave it to the reader to decide whether this sits comfortably with them or not. To my mind scratch building is the creation of a model of a prototype from scratch using the ‘raw’ materials (see Chapter 2) with or without the use of small component parts; for example, the use of etched brass wagon strapping or ‘W’ irons.

In Chapters 6 and 7, I will look at what can be achieved by scratch building rolling stock and will show that this need not necessarily be the preserve of the highly skilled or professional modeller. I will discuss in Chapter 6 the use of materials and techniques that can be used for scratch building; whilst in Chapter 7, I will provide a number of worked examples of scratch building to demonstrate what can be achieved with the application of research, patience and modelling skills. One of the examples I have described is the scratch building of a bogie goods van using plasticard and brass, which shows what can be achieved in these materials.

To aid the scratch builder, there is a plethora of suppliers around today that can provide all sorts of small component parts that will save the scratch builder from having to fabricate every tiny piece of detail for a particular prototype subject being modelled. Having said that, I see no problem, if you feel you have the time, desire, skill level and tools to do the job, with fabricating all these components yourself.

Now having set the scene, it is time to get on with the modelling and I hope that the hints, tips and worked examples presented in this book provide a useful reference for you to develop your modelling skills and will inspire you to have a go.