Chapter 10

LTE URLLC performance

Abstract

This chapter shows the performance of LTE URLLC, comparing the technology to the existing 5G requirements put up by ITU (IMT-2020). Each 5G requirement applicable to URLLC is presented, together with the performance of LTE. Fulfilling the requirements involve both analytical calculations based on the existing design as well as system level and link level simulations. The performance evaluation includes user plane latency. Control plane latency and reliability evaluations. It is concluded that LTE can fulfill the 5G URLLC requirements.

Keywords

3GPP RAN; 4G; 5G; cMTC; Critical MTC; IMT-2020; LTE; mMTC; Third generation partnership project (3GPP); URLLC

In this chapter, the performance of the LTE URLLC design is presented. First the performance requirements on latency and reliability are reviewed. Following the requirements are the tools used to fulfill the requirements where both analytical calculations as well as system level and link level simulations have been used. Finally, link level simulations are provided showing how LTE fulfills the URLLC requirements of IMT-2020 to fulfill the 5G requirements.

10.1. Performance objectives

As mentioned in Chapter 2, the URLLC requirements is a subset of the requirements set up by ITU-R used for a technology to declare itself 5G compliant. This section explains the requirements and how they apply to the LTE technology.

Out of the full set of 5G requirements, the ones of interest for URLLC are user-plane latency, control plane latency and reliability.

To give a better understanding to the reader on the actual requirements, they are described in separate sections below. For the detailed requirement specification, the reader is referred to see Ref. [2].

10.1.1. User plane latency

The requirement on user-plane latency in Ref. [2] is defined as from when a source node sends a packet to where the receiving node receives it. The latency is defined between layer 2 and layer 3 in both nodes. For LTE this would be on top of the PDCP protocol. It is assumed that the device is in an active state, assuming no queuing delays.

A 1

ms latency bound is targeted for URLLC. Both directions (uplink and downlink) have the same requirement.

10.1.2. Control plane latency

The requirement on control plane latency is 20

ms defined from a battery efficient state to when the device is being able to continuously transmit data.

In essence, the latency of interest is the point from where a device initiates a random access procedure connecting itself to the network. For more details on the different device states and the message transfer between the device and the network during the initial access, see Section 9.3.1.1.

10.1.3. Reliability

The requirement on reliability is defined as the probability of successful transmission of a packet of a certain size, within a certain latency bound, at a given channel condition. In other words, we want the system to guarantee that at a certain SINR we can deliver a certain packet reliably within a maximum time.

In case of IMT-2020, the requirement on the latency bound, packet size and reliability are 1

ms, 32 bytes and 99.999% respectively. The minimum SINR where this is achieved is technology specific and is evaluated according to the methodology described in Section 10.2.

10.2. Simulation framework

Simulations are required for the evaluation of the reliability, defined at the coverage edge of a macro scenario, designed for a wide area deployment. This section describes how the requirements on system level simulations and associated link level simulations from ITU has been interpreted by 3GPP in its evaluation toward IMT-2020 for LTE URLLC.

The simulation methodology is provided by the IMT-2020 documents [3] and involve the steps of:

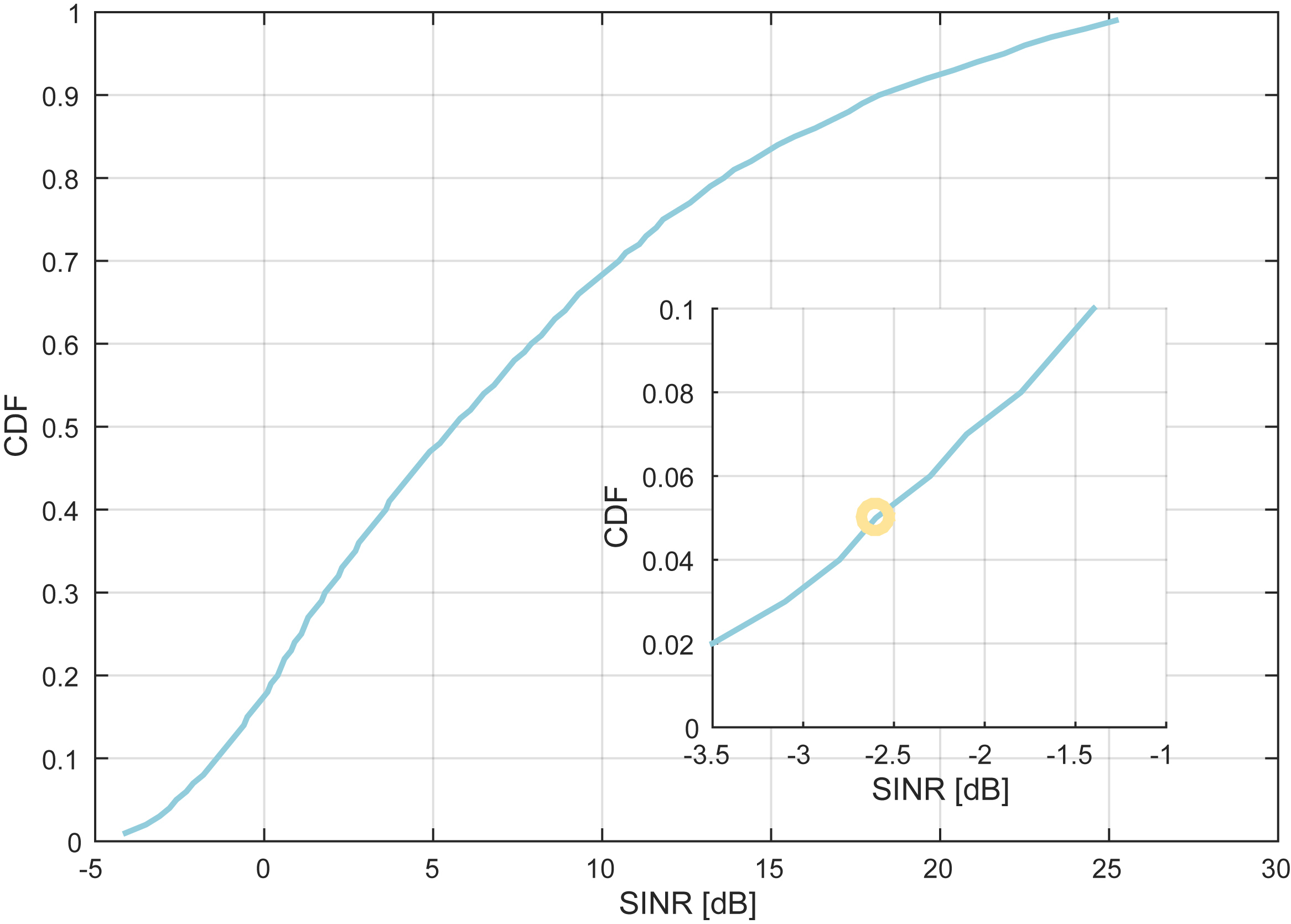

One could think that allowing 5% of the devices in the network to be out of coverage, while requiring the devices in coverage to experience a reliability of 99.999% is not a consistent reasoning. One should however remember that assuming full traffic load of the network (see Table 10.1), i.e. that all resources in all cells are always occupied, is not realistic. Using instead a more realistic network load, the SINR distribution would shift toward higher SINR (assuming the network is interference limited, which is typically the case), which reduces the ratio of devices falling outside of the target SINR depicted in Fig. 10.1.

The relevant system simulation assumptions to produce the curve in Fig. 10.1 are shown in Table 10.1.

Table 10.1

The recorded SINR at the fifth percentile for PDSCH, subslot-PUSCH and subslot-SPUCCH are summarized in Table 10.2.

The main reason that the downlink SINR is worse than the uplink SINR is the use of power control on the uplink, which is not used on the downlink.

10.3. Evaluation

This section presents the performance evaluation for each URLLC requirement described in Sections 10.1.1–10.1.3.

10.3.1. User plane latency

For data transfer there are three different cases of interest:

In case downlink data, the network has full control to schedule the packet after it has been prepared for transmission and put in the transmit buffer (assuming no queuing delay). Hence, only the processing delay and the alignment of the data transmission time with the air interface need to be considered.

For the uplink, the situation is somewhat different since the network will not know when the device has data in its buffer. In case of SR-based uplink transmission (see Section 9.3.2.3), there will be additional delay until the uplink grant is received by the device, compared to having a configured grant available when the data has been prepared. This is since the SR needs to be received by the eNB, followed by an uplink grant to the device, before transmission of data can start.

For services with ultra-low latency requirements, it can be assumed that Semi-Persistent Scheduling (SPS), see Section 9.3.2.7.3, is needed to remove the extra delay of sending SR and receiving uplink grant. SPS can also be assumed to be used in case of periodic traffic when the traffic pattern is predictable. Furthermore, subslot operation is required to get down to the IMT-2020 URLLC target of 1

ms latency bound.

To get the full picture of the user-plane latency, the tables below show performance for legacy LTE (subframe based operation with n+4 processing timeline, see Section 9.2.5), short processing time (subframe based operation with n+3 processing timeline, see Section 9.2.5), slot-based and subslot-based transmission.

Two cases are looked at:

- • HARQ-based retransmissions: In this case, it is assumed that the data is retransmitted using HARQ. This will result in a spectrally efficient transmission since a packet is only retransmitted in case of error. However, the latency is negatively impacted by additional round-trip delays for each retransmission.

- • Blind repetitions: When blind repetitions are used (here assumed consecutive in time), the only additional delay comes from the transmission time of each repetition. Compared to HARQ-based retransmissions however, the spectral efficiency is negatively impacted since extra resources are used without knowing if less resources would have been enough for delivering the packet.

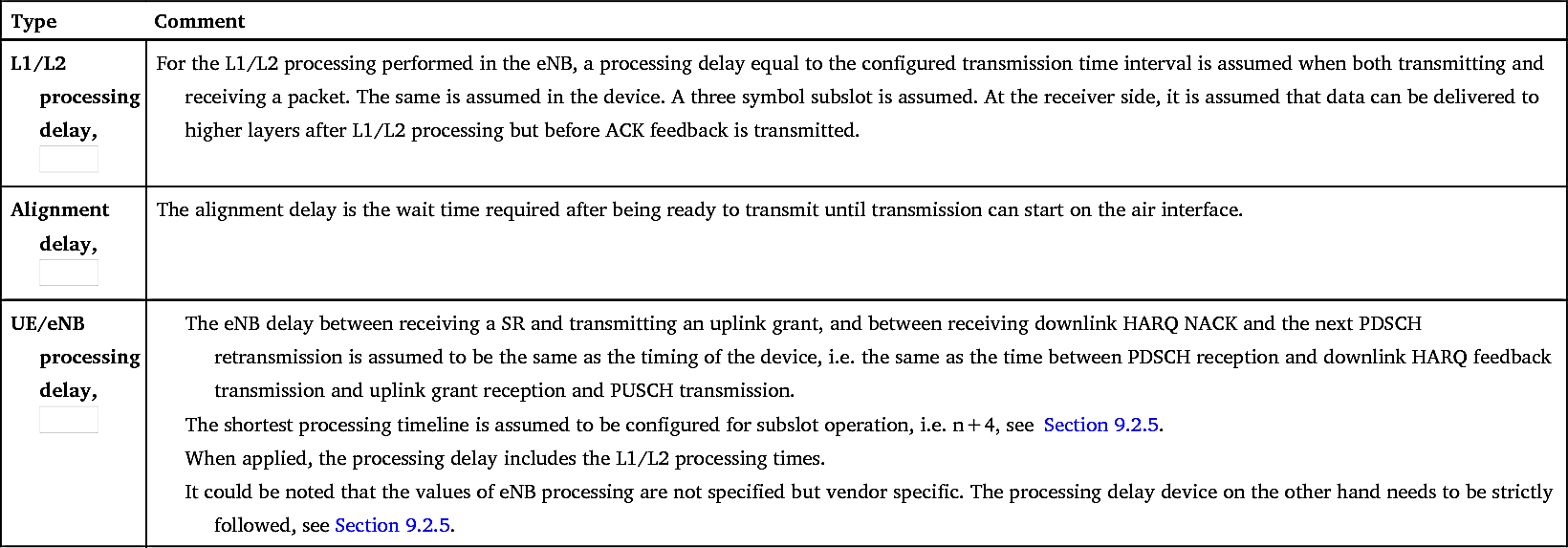

The different delay components relevant for the latency calculation are described in Table 10.3.

It can be noted that additional delay due to the TDD frame structure has not been considered. This is since the structure of TDD, where downlink and uplink transmissions are multiplexed in time, will inherently increase the delay. Adding that TDD is only defined for slot

operation, and not subslot operation, will make the resulting delay relatively far from the IMT-2020 requirements, which is the main focus of this performance chapter.

Table 10.3

| Type | Comment |

|---|---|

L1/L2 processing delay,

|

For the L1/L2 processing performed in the eNB, a processing delay equal to the configured transmission time interval is assumed when both transmitting and receiving a packet. The same is assumed in the device. A three symbol subslot is assumed. At the receiver side, it is assumed that data can be delivered to higher layers after L1/L2 processing but before ACK feedback is transmitted. |

Alignment delay,

|

The alignment delay is the wait time required after being ready to transmit until transmission can start on the air interface. |

UE/eNB processing delay,

|

The eNB delay between receiving a SR and transmitting an uplink grant, and between receiving downlink HARQ NACK and the next PDSCH retransmission is assumed to be the same as the timing of the device, i.e. the same as the time between PDSCH reception and downlink HARQ feedback transmission and uplink grant reception and PUSCH transmission.

The shortest processing timeline is assumed to be configured for subslot operation, i.e. n+4, see Section 9.2.5.

When applied, the processing delay includes the L1/L2 processing times.

It could be noted that the values of eNB processing are not specified but vendor specific. The processing delay device on the other hand needs to be strictly followed, see Section 9.2.5.

|

That is, the table and the following latency calculations assume FDD operation.

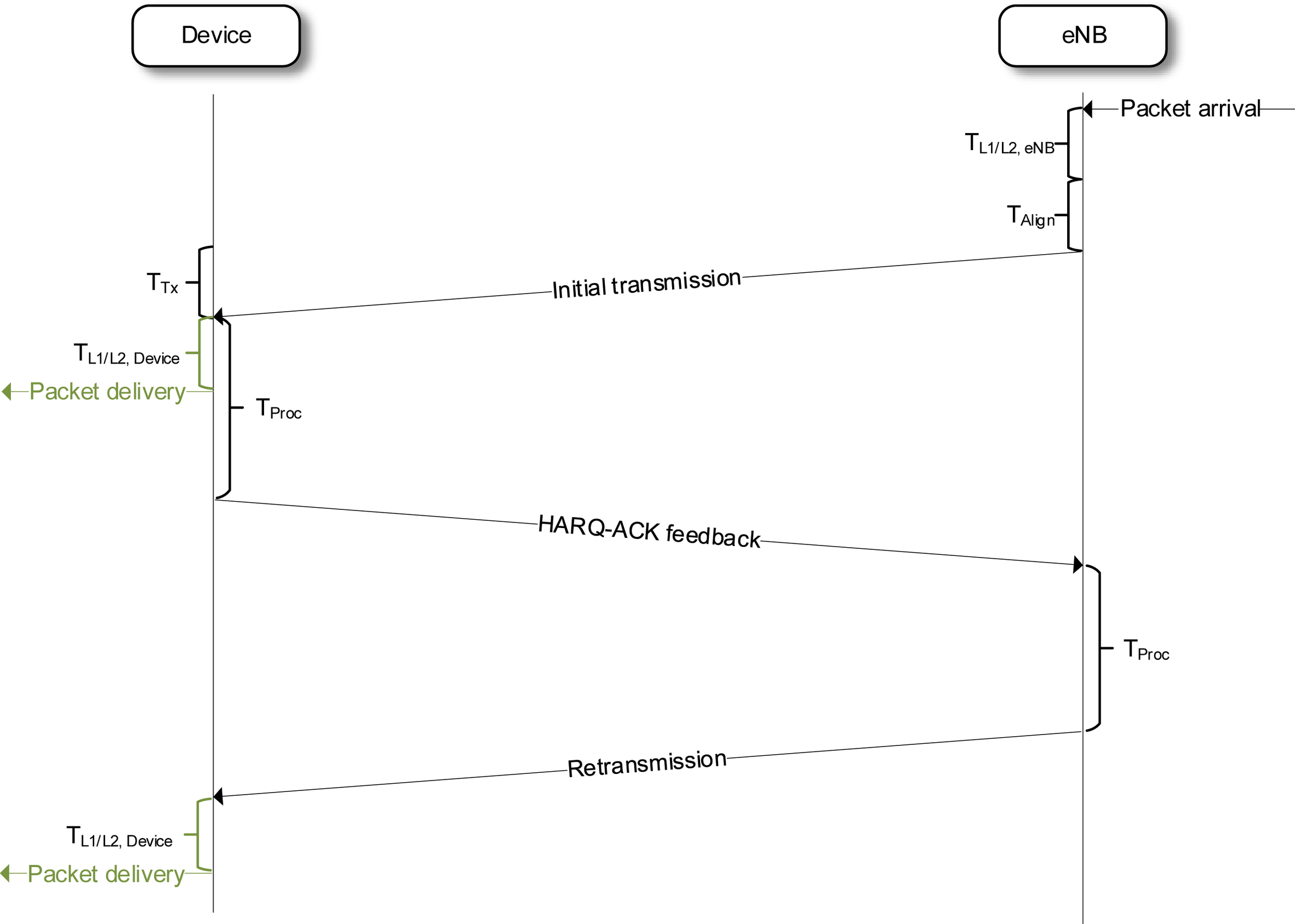

Fig. 10.2 shows the signal diagram for a downlink data transmission including the associated delays (ignoring propagation delay). It is considered that the packet can be delivered either in the first or the second attempt (depending on packet errors over the air).

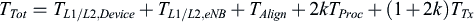

The downlink data transmission delay can also be written as an equation, assuming k retransmissions.

(10.1)

(10.1)

For one retransmission, assuming regular timing of n+4 (

T

P

r

o

c

=

2

T

T

I

), and that

), and that

T

L

1

/

L

2

=

T

A

l

i

g

n

=

T

T

x

=

1

TTI

, the delay becomes:

, the delay becomes:

), and that

), and that

, the delay becomes:

, the delay becomes: (10.2)

(10.2)

It can be noted that the processing timeline for the HARQ-ACK response, see Section 9.2.5, of the device is set by the specifications, while being implementation dependent for the eNB (in case of asynchronous HARQ). It is however assumed in Eqs. (10.1) and (10.2) that the same processing is assumed for both device and eNB. Furthermore, the L1/L2 processing time is different for different implementations in both network and device, and hence not defined by the specification.

The time to align with the frame structure will be given by the transmission granularity, i.e. how often a packet can be transmitted over the air. In case of LTE, this is based on a fixed structure using either subframe, slot or subslot granularity.

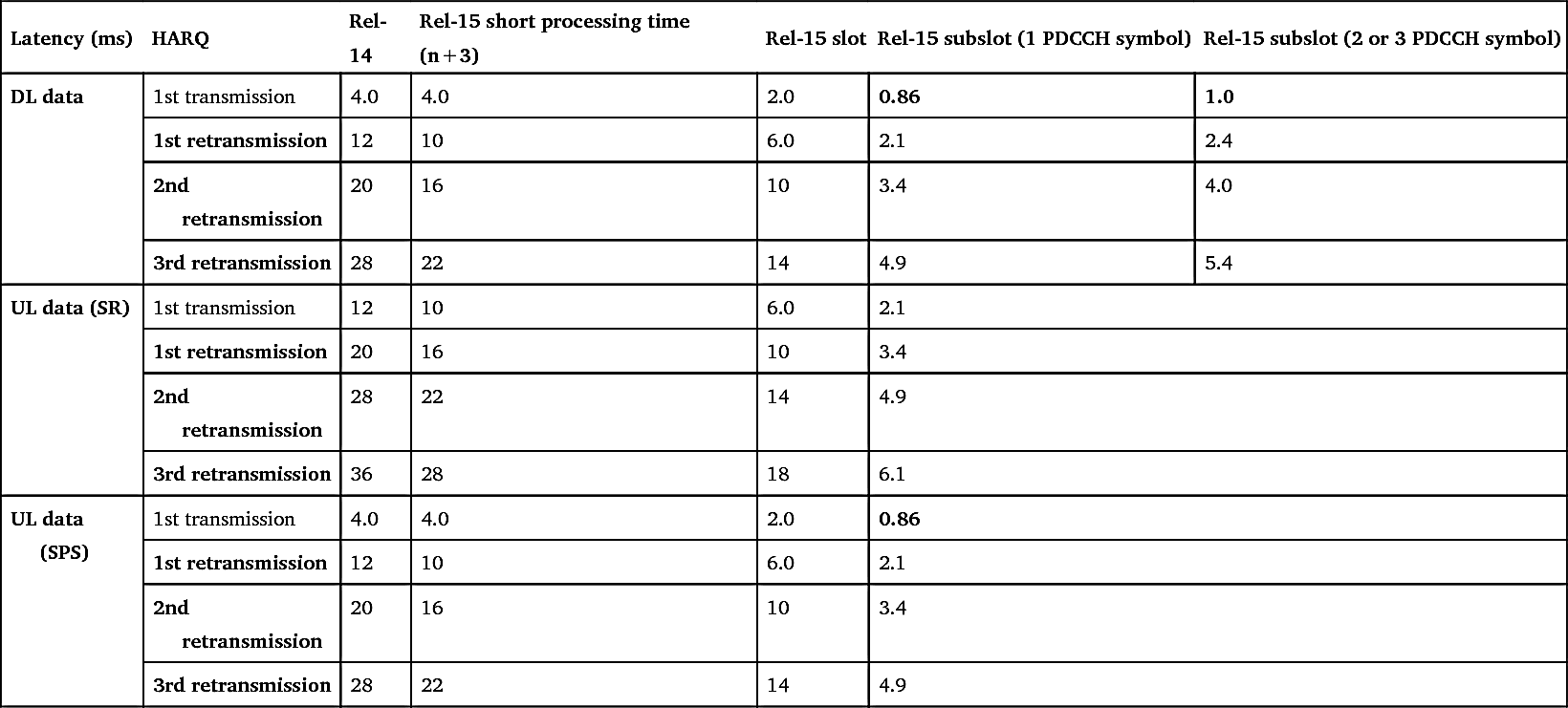

For uplink data using SR, the calculation of the delay is similar to the calculation of downlink data. The difference is that the packet is arriving at the device, and the packet is delivered to higher layers after reception at the eNB. Also, in this case, one round-trip time is consumed from SR transmission to the transmission of the PUSCH based on the uplink grant received. Hence, as expected, the latency for X uplink data retransmissions based on SR, is the same as the latency for X+1 uplink data retransmissions based on SPS. This is seen in Table 10.4 which presents the results from the user plane latency evaluations.

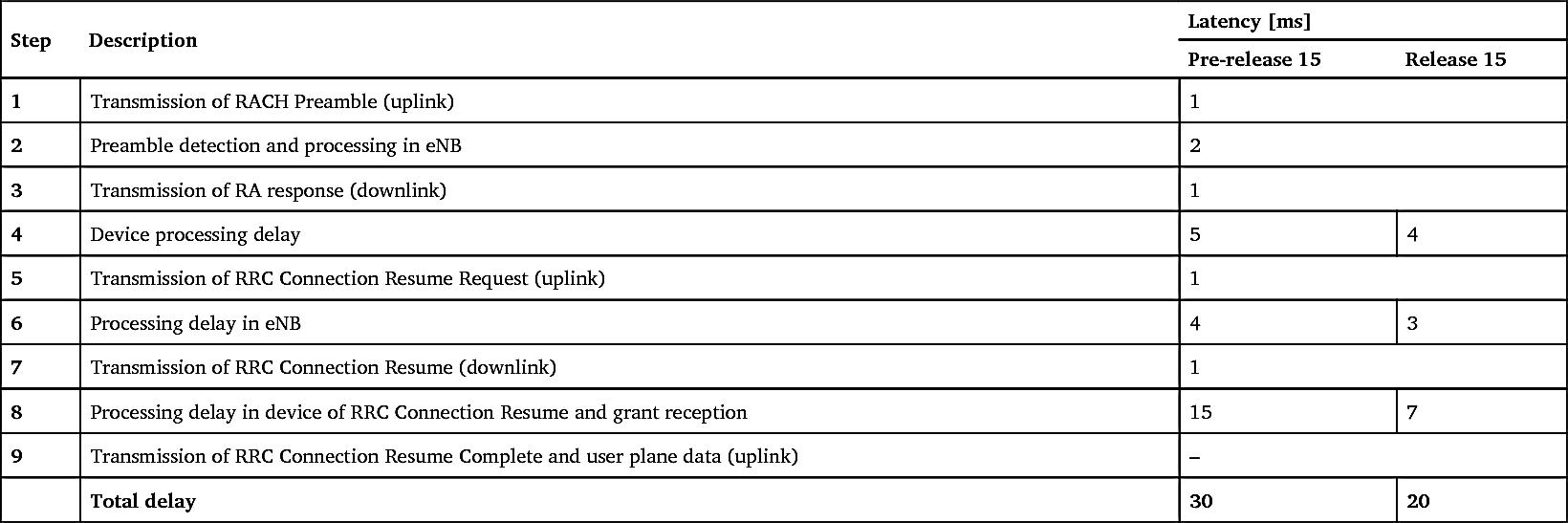

In all cases, it is assumed that the worst-case latency is used. This assumption has no impact on subframe based and slot-based operation due to the symmetry in the radio frame. For subslot operation however, the delay will vary over the subframe due to the irregular subslot structure, see Fig. 10.2. For subslot operation, the delays in Tables 10.4 and 10.5 are considering the largest delay of the five possible subslot starting numbers for the packet arrival. The three different possible PDCCH symbol configurations, one, two, or three, are considered. Using a single PDCCH symbol will decrease the overall latency since the

alignment time will be reduced. However, using less symbols for the DL control will have a direct impact on the DL control capacity, and hence this trade-off need to be considered when deciding the size of the DL control region.

Table 10.4

Table 10.5

Another influence on the latency due to the irregular subslot structure is the assumption on 1 TTI latency of L1/L2 processing. It should be noted that this is a simplified assumption and the actual timing need not be related to the over-the-air transmission duration. Still, in this evaluation, it is assumed that the L1/L2 processing assumes the value of 3 symbols, same as the longest subslot duration.

The user plane latency using HARQ-based retransmissions and using blind repetitions is shown in Tables 10.4 and 10.5 respectively using different number of retransmissions and repetitions.

If a 1

ms latency bound is to be respected (marked in bold in Tables 10.4 and 10.5), see Section 10.1.1, one can see that for:

- • Downlink data and uplink data using grant-based transmission, either a single transmission is required, or one blind repetition. Using HARQ-based retransmissions will however violate the latency bound. It can be noted that using a blind repetition is only possible in the DL in case 1 PDCCH symbol is configured.

- • Uplink SR-based transmission, no configuration fulfills the latency bound

10.3.2. Control plane latency

The background to the control plane latency and the improvements made to the 3GPP specifications are described in Sections 9.3.1.1 and 10.1.2

.

To summarize, instead of changing existing initial access procedures in how information is transmitted over the air, which could imply implementation cost and backwards compatibility issues in existing networks, a simple approach was taken by shortening the processing time at both the device and the network in the initial access procedure.

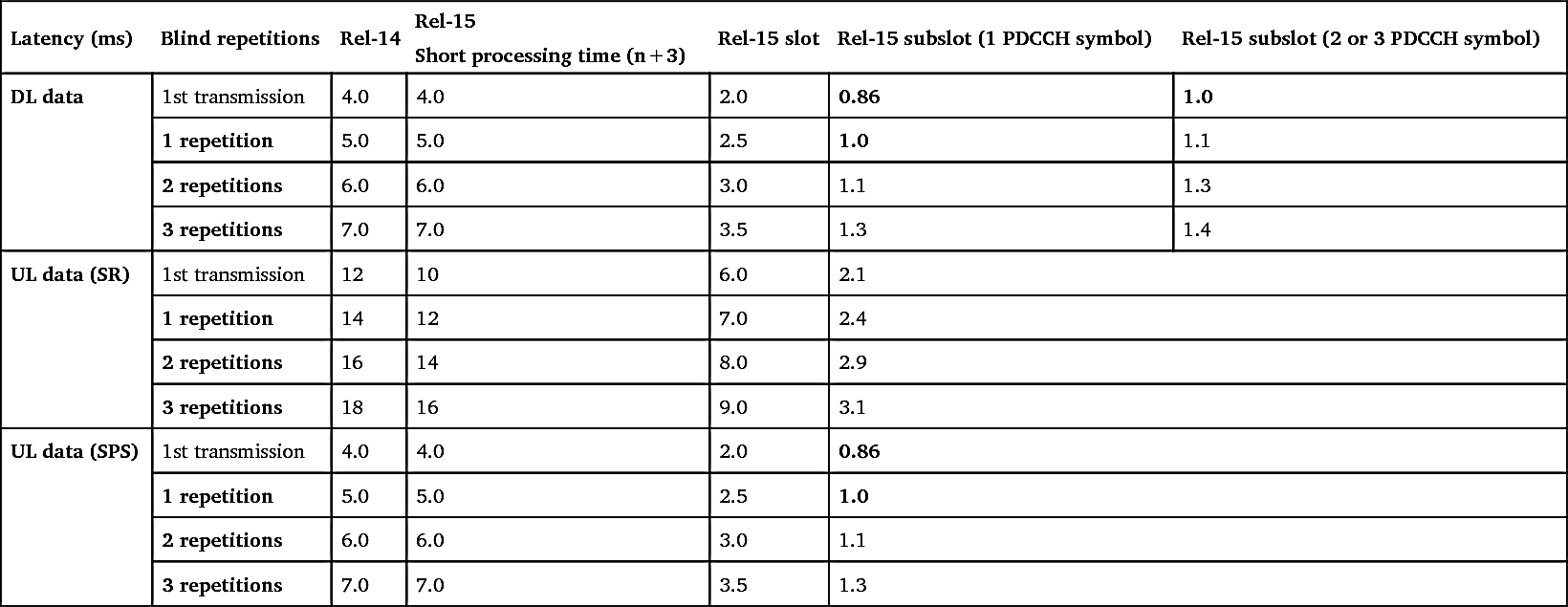

The resulting control plane latency is shown in Table 10.6.

As can be seen, the target of 20

ms control plane latency, see Section 10.1.2, is reached.

10.3.3. Reliability

The latency calculations carried out in Section 10.3.1 is an analytical exercise assuming different number of retransmissions and no queuing effects at the scheduler (as assumed in the requirements, see Section 10.1.1). Still, it determines the configurations under which a certain latency bound can be met.

To determine the associated reliability, simulations are needed that model the radio performance under the conditions given by Section 10.3.1.

In Section 10.3.1 it was concluded that for downlink and uplink transmissions, to fulfill the 1

ms target, there is no time for HARQ retransmissions. Instead, blind repetitions need to be used to lower the latency while maintaining a high level of reliability. Furthermore, uplink transmissions need to be carried out by pre-configured uplink grant using SPS (not based on scheduling requests, which increase the overall latency by one round-trip time). Both the use of blind repetitions (instead of HARQ retransmissions) and pre-configured uplink grants

(instead of scheduling requests) will increase the usage of radio resources. This is a cost we need to be willing to pay to reach the ultra-reliable radio link performance at a low latency.

Table 10.6

The reliability will be here estimated assuming a certain physical layer payload size to be transferred (32 bytes) assuming a certain latency bound (1

ms) achieving a target reliability (99.999%). These conditions are all given by the IMT-2020 requirements. Furthermore, these conditions are to be fulfilled at the cell-edge SINR assumed in the network, defined by Table 10.2.

10.3.3.1. Reliability of physical channels

To understand the reliability performance, we need to look at how the physical channels are designed. This is where most of the description in Chapter 9 comes in. Although it should be noted that the IMT-2020 use case of a latency bound of 1

ms

at a reliability of 99.999% can be seen as an extreme case, this is what much of the LTE URLLC technology was designed and targeted for, and this is also the main use-case we evaluate in this chapter.

The possible physical channels involved in these evaluations are (S)PDCCH, SPUCCH, PDSCH and PUSCH, but as will be seen, not all channels need to be part of the evaluation.

Our task is now to determine an SINR where the overall block error rate, taking all channels involved in the data transfer into account, is below the target of 10

−5. To fulfill the overall reliability requirement, this determined SINR should be equal to, or below, the values listed in Table 10.2.

10.3.3.1.1. Downlink

For the downlink, the channels involved in a data transmission are (S)PDCCH and PDSCH. If HARQ retransmissions were to be considered, also SPUCCH would have to be included (i.e. carrying the HARQ-ACK feedback triggering the retransmission). There is

however no time within the latency bound for this (see Section 10.1.1) and hence the uplink control channel can be excluded. The reason for writing “(S)PDCCH” is that the PDSCH can be scheduled by either PDCCH or SPDCCH depending on which subslot the data is scheduled on (See Section 9.2.2 and 9.2.3.2.1). However, in this simulation campaign, it is assumed that the downlink data is earliest mapped to symbol index three, implying that SPDCCH is always used. The reason for this choice is to model a worst-case situation where PDCCH is not used for scheduling and less blind transmissions can be performed within a given latency bound (compared to the case where the data can be mapped to symbol index 1).

The channels involved are shown in Fig. 10.3 for a two-antenna port CRS configuration, one symbol CRS-based SPDCCH, and a mapping of the data REs earliest in symbol index

three. The five possible starting positions for a blind repetition sequence of two or three transmissions is also shown. Whether two or three transmissions are shown depends on the latency budget of 1

ms (note that Table 10.5 shows only the worst-case latency over all possible starting positions, but in reality, it will vary depending on starting position). A single physical resource block in frequency is shown. Depending on how the mapping of control and data is done, some resource blocks will contain only data, some only control, or, as in the case of Fig. 10.3, both. As shown in Table 10.7, it has been assumed that 32 % of the data allocation overlaps with SPDCCH in the first symbol of the subslot. Hence, in roughly 1/3 of the resource blocks, the PDSCH is rate-matched around SPDCCH.

Table 10.7

| Parameter | Setting |

|---|---|

| Carrier frequency | 700 MHz |

| Bandwidth | 20 MHz (100 Resource Blocks) |

| Channel | TDL-C, 363 ns, see Ref. [4] |

| Device speed | 30 km/h |

| TTI length | Subslot (2 or 3 OFDM symbols depending on where transmission is made) |

| Start of DL data | Symbol index 3 (See Section 9.2.2) |

| Payload | 32 bytes |

| MCS | MCS-0 (occupying 55 resource blocks) |

| Resource allocation | Resource allocation type 0 (See Section 9.3.2.9.1) |

| Transmission mode | 2TX, 2RX, 1-layer TX diversity |

| Reference signal transmission | CRS-based |

| Channel estimation | Realistic |

| SPDCCH |

1 symbol CRS-based SPDCCH (See Section 9.2.3.2)

AL8 (8 SCCE in total over bandwidth)

(about 32% of data allocation in first symbol has overlapping SPDCCH)

|

| Transmissions |

2 (Blind repetitions without HARQ)

The same redundancy version (RV0), see Section 9.3.2.7.1, used for both transmissions.

|

| DCI size | 40 bits payload + 16 bits CRC |

As can be also seen from the figure, there will be variations in the number of resources for data over time (some subslots are three symbols, some two symbols, some PRBs in some OFDM symbols contain SPDCCH, some not, in some subslots the data collides with CRS, in some not). Also, the SPDCCH performance will vary due to CRS-overhead (as well as DMRS and CSI-RS, if configured – not shown in this figure). These are all aspects the

network has to consider when selecting the aggregation level for the device on the SPDCCH (see Section 9.2.3.2) as well as the MCSs selected for data transmission.

The simulations have assumed the worst-case possible configuration where one of the two SPDCCH transmissions are hit by CRS (fourth or fifth configuration in Fig. 10.3). This can be considered the limiting case in terms of performance for the SPDCCH. Regarding PDSCH performance, one of the subslots will have a three-symbol duration resulting in more REs available for data transmission (this does however not improve the SPDCCH performance, which is here configured to one symbol duration).

The simulation assumptions used are shown in Table 10.7.

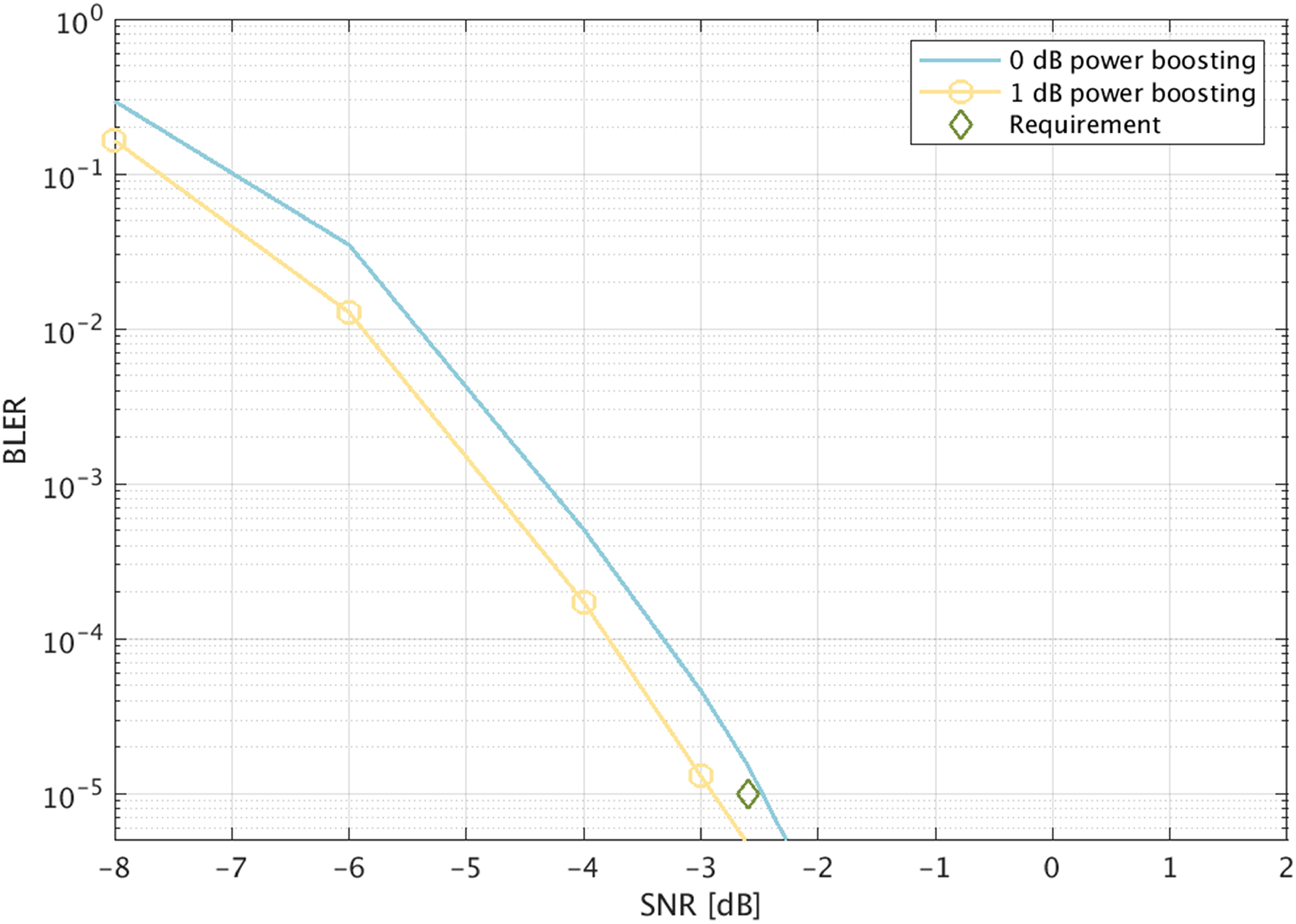

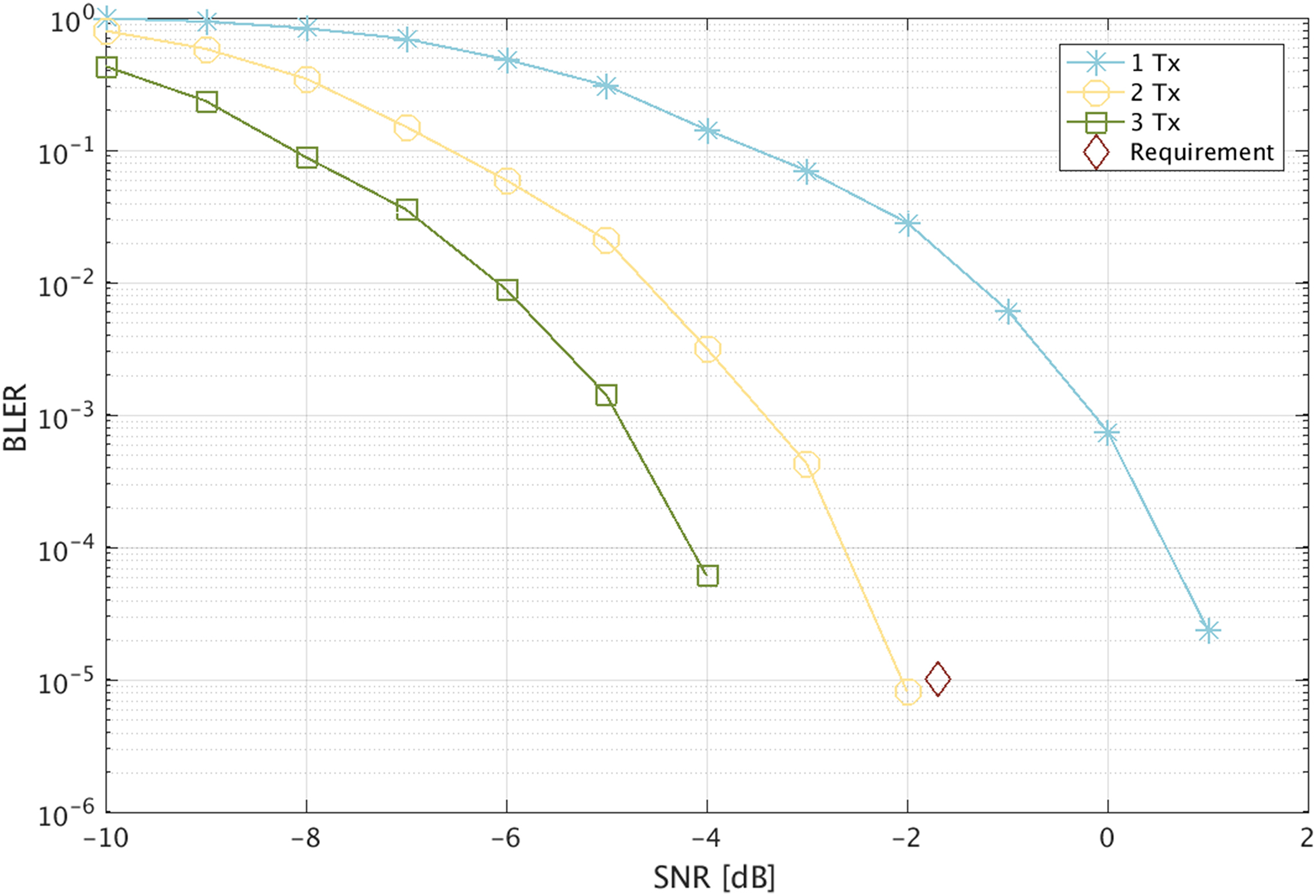

The simulation results from the above simulation assumptions are shown Fig. 10.4.

As can be seen, the target performance of a reliability of 10

−5

at SINR of -2.6

dB (see Table 10.2) is reached assuming a power boosting of 1

dB for the SPDCCH resources. The power boosting is necessary due to the performance imbalance between the data and control channel (the decoding of the data channel is conditioned by the decoding of the control channel). The implication of boosting the power of the control is that the remaining power left for the other resource elements in that OFDM symbol will be more restricted.

10.3.3.1.2. Uplink

For the uplink, the channel involved is only PUSCH. This is since we are only interested in the case of using a pre-configured grant (by SPS, see conclusion in Section 10.3.1), and it is

assumed that this is pre-configured to the device. Since there is no time for HARQ-based retransmissions, the downlink control channel, SPDCCH, does not come into play.

Table 10.8

| Parameter | Setting |

|---|---|

| MCS | MCS-1 (occupying 85 resource blocks) |

| Transmission mode | 1TX, 2RX |

| Transmissions |

1, 2 or 3 (Automatic repetitions without HARQ)

The same redundancy version (RV0), see Section 9.3.2.7.1, used for all transmissions.

|

| TTI length | Subslot (2 OFDM symbols) |

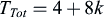

From Table 10.5, it can be seen that the 1

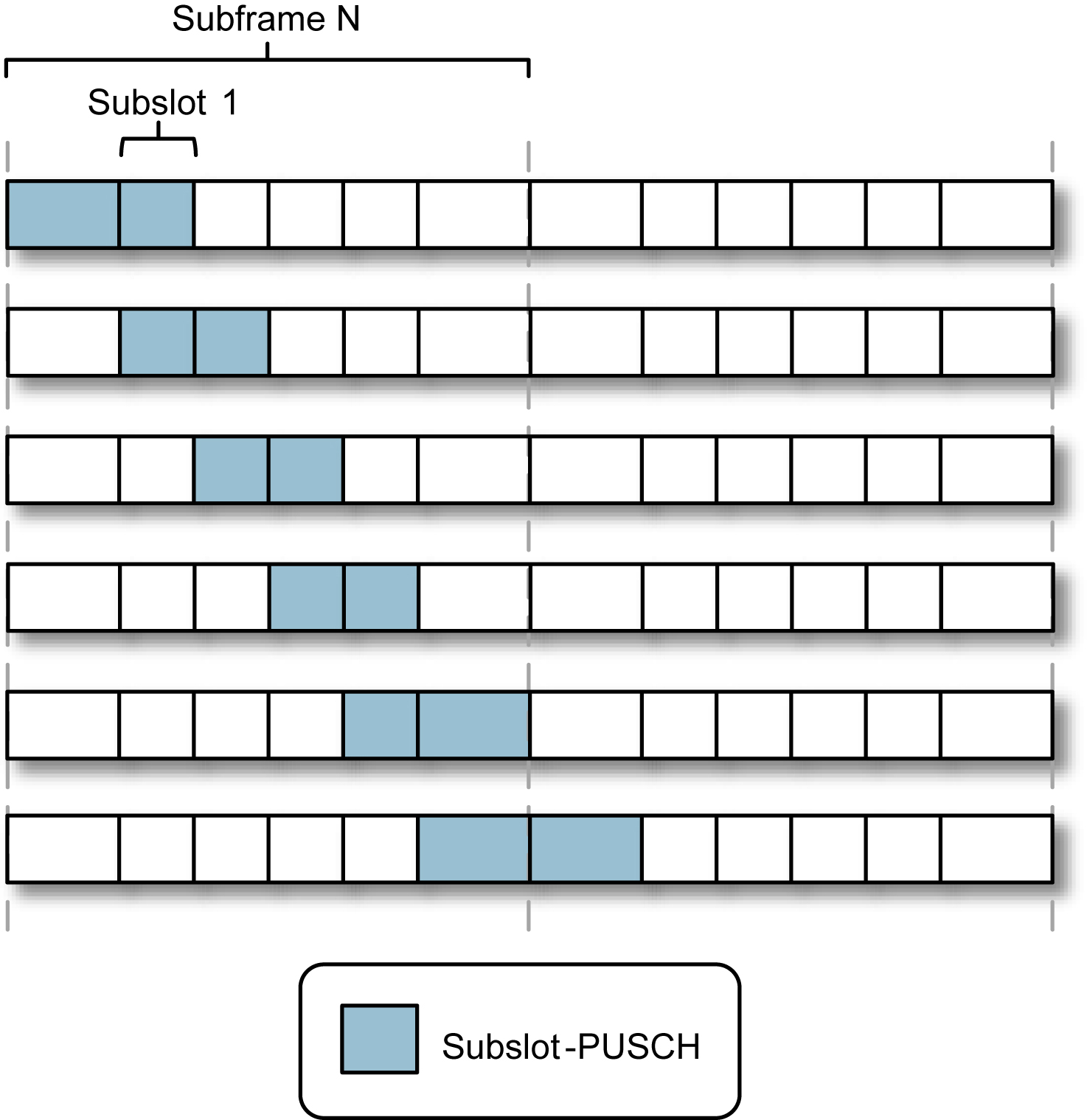

ms bound can be fulfilled using two transmissions of PUSCH. The possible starting positions and the following consecutive transmissions are illustrated in Fig. 10.5. Compared to the downlink (see Fig. 10.3), the number of repetitions does not vary depending on where the repetition window starts. Using three transmissions will violate the latency bound.

The worst-case performance would be expected if the two transmissions are performed using three consecutive 2-symbol subslots (second, third and fourth configuration in

Fig. 10.5). This is since less resources are available for transmitting the data, and hence, this is what has been simulated (see Table 10.8).

The link simulation assumptions different from the ones for the downlink (see Table 10.7) are shown in Table 10.8.

As can be seen, the PUSCH SINR target of -1.7

dB

at a reliability of 10

−5 is achieved with the use of two transmissions. However, it can be noted that the allocation consumes 85 out of 100 resource block in the carrier. Furthermore, it is assumed that this is a pre-configured resource to the device and that the scheduling interval is each subslot. This causes severe restrictions to the network operation (essentially one device taking up almost all of the resource in the uplink).

Using a higher MCS would lower the frequency allocation required. However, although the same overall energy would be transmitted with a smaller allocation (using a higher power spectral density, PSD), some additional degradation would be expected from the increased code rate of the MCS by reducing the resource allocation, less frequency diversity, and possibly from using a higher order modulation.

The results will depend on if the network is interference or noise limited, the fraction of cMTC users etc, but it could be expected that with a slightly relaxed SNR requirement, the impact to the use of the network resources can be alleviated. However, with the requirement of -1.7 dB, the performance margin is very limited for the case of two transmissions, as can be seen in Fig. 10.6.