Figure 4.1. Rev. Roy Flournoy of Denver, Colorado, publicizes his Mormon Tabernacle Choir boycott in Jet Magazine, January 8, 1970, and February 19, 1970.

Since when and on what grounds have white American Christians declared ourselves innocent of the sins of our generations? When did white American Christianity—at least Protestantism—excuse itself from grappling with the most serious and far-reaching human abuses, the Cain-slew-Abel on a global scale, to make as its object instead the perpetuation of an undisturbed and unchallenged hold on continuity and capital? Recall again the words of James Baldwin in his 1962 letter to his nephew, “My Dungeon Shook”:

They have destroyed and are destroying hundreds of thousands of lives and do not know it and do not want to know it. One can be—indeed, one must strive to become—tough and philosophical concerning destruction and death, for this is what most of mankind has been best at since we have heard of war; remember, I said most of mankind, but it is not permissible that the authors of devastation should also be innocent. It is the innocence which constitutes the crime. . . . These innocent people . . . are in effect still trapped in a history which they do not understand and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it.1

White became right early in American Christianity, and even more so with religious movements’ institutionalization and mass production of theologies and religious curricula designed not to unsettle but to stabilize and consolidate power. Such theologies have vested the mechanisms of white supremacy with an originalism that erases the facts of Black experience and conveys blamelessness on whites. Thus, it has sold “morality” as the unknowing blamelessness of children rather than the hard-won wisdom of adults who make difficult choices. White American churches have offered rites, performances, and salvific formulas that in exchange for a specific individual performance of piety (typically defined by heteronormatively married sexual monogamy, polite manners, deference to authority) promise moral exculpation from the wrongs of history.2 Moreover, white American Christian cultures have serviced white supremacy at large by offering to American publics spectacles and entertainments that convey a sense of absolution or transcendence without moral responsibility. White American religiosity has served as a technology for the production of white racial innocence.

As Robin Bernstein has argued in her book Racial Innocence (2011), during the nineteenth century, in novels like Uncle Tom’s Cabin, white American audiences connected imaginatively with innocent child characters like Little Eva as a way to evade taking responsibility for racism:

To be innocent was to be innocent of something, to achieve obliviousness. This obliviousness was not merely an absence of knowledge, but an active state of repelling knowledge—the child’s “holy ignorance.” . . . Innocence was not a literal state of being unraced but was, rather, the performance of not-noticing, a performed claim of slipping beyond social categories.3

By taking delight in the performance of “obliviousness” or “forgetting” through the figuration of children, white American adults found a way to convince themselves that they were innocent of racist wrongs and bore no responsibility for addressing racist power structures. This willed innocence sustained white supremacy.4

The advent of mass media extended exponentially the power of white Christian religiosity to convey moral innocence through spectacle, and it did so at the very same moment Black emancipation struggles nationalized due to twentieth-century Black migration and the advent of a nationwide civil rights movement. In truth, Black freedom was never a regional struggle, but it was easy for white majorities in the north and west to imagine so, and thus to exculpate themselves from moral responsibility. These silent white Christian majorities contributed mightily to the perpetuation of white supremacy. If we are to understand the role religion played in white supremacy in the United States, we have to look beyond the familiar and highly visible stories of the roles Black churches and white evangelicals in the South played in advancing and contesting segregation and white supremacy to this broader national dynamic: how white American churches across the country communicated to the people in the pews that they could be good, moral, and redeemed without seriously confronting America’s brutality toward African Americans, past and present. Many mainstream white churches maintained silent agreements to “overlook” such issues or to embrace religious figures who harbored unethical views on race. Good Christians, after all, were expected not to bring contention or division into the house of God.

Theologian James Cone once called on scholars to “sound out” the silent agreements that stand behind white racism. For my part, I will use this chapter to “sound out” the way my coreligionists during the advent of mass media and the decades of the civil rights movement provided to the white American public spectacles that satisfied white supremacy’s need to assert its moral superiority while at the same time disclaiming moral responsibility for its wrongs. As it sought to transition organizationally from a marginal sect to a mainstream church in the twentieth century, the LDS Church institutionalized a formerly loose and contradictory set of views on the role of African Americans in the faith into coherent policies and practices of anti-Black racism and segregation. The LDS Church also sought in these years to win broader social acceptance from the white American public, and it did so through public relations programming that promoted an image of Mormons as deeply patriotic, morally trustworthy, conservative white Americans.5 Key to this public relations effort were the Mormon Tabernacle Choir and the Osmond family. Founded in 1847, the 360-member choir, an official body of the LDS Church, served as the primary media instrument through which mainstream America transitioned its imaginings of Mormons away from the sensationalized, sinister depictions of Mormon polygamy, deceit, sexual divergence, and separatism provided by nineteenth- and early twentieth-century political cartoons. Through its nationally syndicated radio broadcast Music and the Spoken Word and an ambitious touring schedule, the Mormon Tabernacle Choir offered a new image of Mormons as clean, disciplined, industrious, wholesome, and patriotic. It achieved remarkable mainstream success including a Billboard Top 20 hit with “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” (1959), which also won a Grammy, and invitations to perform at the White House and the presidential inaugurations of Lyndon B. Johnson (1965), Richard Nixon (1969), and every Republican president who followed, including Ronald Reagan, who called the Mormon Tabernacle Choir “America’s Choir.” By the late 1960s, the choir’s programs were broadcast regularly on more than four hundred radio stations and thirteen television stations in the United States. When their broadest public popularity dipped in the late 1960s, they were succeeded in the public eye by the Osmonds of Ogden, Utah, a family musical group featured regularly through the 1960s on the Andy Williams Show, peaking in popularity in the 1970s, before youngest siblings Donny and Marie scored number one hits and their own Friday night television show, which ran from 1976 to 1979 on ABC. The Osmonds, though not officially sponsored by the Church, made Mormonism a major element of its public presence.

At almost no point during the 1950s, 1960s, or 1970s did white American audiences who patronized the Mormon Tabernacle Choir or the Osmonds express concerns about the explicit anti-Black racism of the LDS Church. As Jan Shipps, an eminent scholar of Mormonism, wrote in her assessment of media coverage of Mormonism during these decades, “the LDS Church had what Americans who embraced the civil rights movement regarded as a retrograde position on race, one noted and commented on in the print media, especially Time, Newsweek, the Christian Century, and elite newspapers on the East Coast and West Coast. But that encumbrance was usually overlooked in radio and television broadcasts.”6 “Overlooked” may not be strong enough a term. White American audiences openly embraced the most visible public emissaries of an officially racially segregated faith. This embrace entailed a silent agreement between white Mormon performers and their white audiences. This chapter focuses on this silent agreement between Mormon performing acts and white American audiences: how it worked, why it mattered, and how it enabled white Mormons to continue uncritically in their anti-Black religious beliefs and practices. The Mormon Tabernacle Choir and the Osmonds enacted a spectacle of innocence that normalized anti-Black racism as an unremarkable element of a “wholesome” morality. Their performances engaged audiences in a silent agreement to “forget” racism and to claim a moral high ground without taking responsibility for the oppression of people of color. Twentieth-century Mormon performers like the Mormon Tabernacle Choir and the Osmonds thus played into an older pattern of American culture in which white American publics sought in cultural spectacle ways to absolve themselves of the sins of their generations. And in exchange for doing this form of white supremacist cultural labor, Mormons were rewarded with a modicum of social acceptance. White American audiences admitted Mormon performers into the mainstream not only because Mormons aspired to join it but also because Mormons served as surrogates for the white American aspiration to willed innocence and obliviousness.

Founded in Salt Lake City in 1847 by a band of recently migrated volunteers, the Mormon Tabernacle Choir evolved over the century that followed into Mormonism’s most important ambassadors to the world. Especially after the creation of the Music and the Spoken Word radio program in 1929, the choir logged a series of appearances at World’s Fairs, a national and international tour, and even invited visits to the White House. It was a 1955 Mormon Tabernacle Choir tour of Europe that convinced the Church to create its own publicity bureau—the Church Information Service—which played a critical role in placing articles in the Saturday Evening Post (1958) and Look magazine (1958) celebrating the Church’s welfare programs, emphasis on patriarchal families, and members’ abstinence from alcohol and tobacco as emblematic of “wholesomeness.” The choir’s 1958 “Grand America” tour included stops at Carnegie Hall and on the Ed Sullivan Show. Choir President Lester Hewlett explained in a 1958 letter to George Romney, then president of the American Motors Corporation: “Our only reason for going out like this and spending several hundred thousand dollars is to break down prejudice so that our missionaries can get entrance into more homes,” an effort more likely to achieve conversions than, as Hewlett characterized the LDS missionary experience, “just hammering doors like you and I did years ago.”7

In the late 1950s, the choir had toured on a repertoire of sacred music like “the Lord’s Prayer” and classical choruses by Bach, Schubert, and Haydn. But it included as the last track on its 1959 LP The Lord’s Prayer an arrangement of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Columbia records released it as a 45-rpm single. By the end of October 1959, it peaked on the Billboard pop charts at number thirteen, charting under Bobby Darin’s number one “Mack the Knife” and hits by Paul Anka and the Everly Brothers. Choir historian Michael Hicks writes that “Battle Hymn” catered to “nationalist fervor,” “a self-promotional enthusiasm now fueled by Sputnik and the competitiveness between the Soviet Union and the United States.”8 That same fall, the choir won the Grammy for “Best Performance by a Vocal Group or Chorus,” beating out the Ames Brothers, the Kingston Trio, the Browns, and the Robert Shaw Chorale. A one-hour patriotic television special “Let Freedom Ring” produced by Salt Lake City’s KSL television station centering around the choir and its rendition of “Battle Hymn” won a Peabody Award for public service in television in 1961. The success of “Battle Hymn” sealed the association between Mormonism, religious “wholesomeness,” and Cold War patriotism.

The moment that epitomized the choir’s iconic value not only to Mormonism but also to American nationalism came on July 23, 1962, when it appeared as the featured musical number in a US government–backed propaganda television special filmed at Mount Rushmore and broadcast in Europe via satellite, the first satellite-televised program in history. NASA had launched the AT&T-developed Telstar satellite on July 10, and the nation’s three major television networks—ABC, NBC, and CBS—collaborated to produce a broadcast special interspersing musical numbers by the choir, including “Battle Hymn” and Martin Luther’s “A Mighty Fortress Is our God,” with images of President John F. Kennedy, baseball games, and stampeding buffalo.9 The broadcast, writes one media critic, captured the “conjunction of technology, geopolitics, and religious striving”; marked a “high point of assimilation for the choir and the church”; and reached an estimated hundreds of millions of viewers in seven voiced-over languages in eighteen countries. This and similar televised visual depictions of Mormonism in the 1960s, Jan Shipps has observed, positioned LDS people against the Left or the emerging counterculture, with the claim that Mormons were “more American than the Americans” a common refrain.10

The choir continued to hold its iconic place in the national spotlight, singing when President John F. Kennedy spoke at the Mormon Tabernacle in 1963 and again at a special national broadcast organized to mourn his assassination, appearing at the World’s Fair in New York City, and honoring an invitation from President Lyndon B. Johnson to sing at the White House in July 1964. But the contexts around the choir were shifting in ways that would impact in the longer run Mormonism’s prospects for continuing assimilation and influence in American life. The growth of the civil rights movement put institutionalized racism and anti-Black segregation at the center of national conversation. Mormons, a contemporary survey found, did not stand outside national norms in their views on secular racial integration.11 In fact, in response to pressure from the NAACP, the Church had issued in 1963 a statement expressing its support for “full civil equality for all of God’s children.” But the Church steadfastly held to its explicitly anti-Black segregationist policies and Church leaders sought to repress critical discussion within the LDS community of the ban and its origins.12

The appearance of the choir at the inauguration of President Johnson in January 1965 came at a particularly momentous time in the national debate over African American civil rights. Johnson had signed the Civil Rights Act forbidding segregation in government services and public accommodations in July 1964. In his January 4, 1965, “State of the Union” address, he had promised as part of his Great Society effort to pursue equality for African Americans through “enforcement of the civil rights law and elimination of barriers to the right to vote.”13 Just days before the inauguration, on January 15, Johnson spoke by phone with Martin Luther King Jr., who had just launched the Selma Voting Rights campaign, and agreed to push for the legislation that would become the Voting Rights Act (1965). When the choir took the stage on January 20 to sing “Battle Hymn of the Republic” as the inauguration’s closing number, King and others were organizing in Selma. Just a few weeks later, on March 9, as King led marchers across the Edmund Pettis bridge, African American activists in Utah protested at LDS Church headquarters, and the most prominent Mormon of his time, Michigan Governor George Romney, led a march of ten thousand in Detroit to support voting rights and demonstrate solidarity with the Selma marchers. It seems remarkable that an all-white choir from an officially segregated religion took and held center stage to perform “Battle Hymn of the Republic” at this contested moment in American life—even more so when one notes that Greek Orthodox Archbishop Iakovos, who gave the closing prayer at the inauguration, joined King and the Selma marchers on March 15.

The nature of a silent agreement is that its terms are never spoken aloud. For this reason, there is no extant evidence to document why President Johnson gave the choir a “pass” on its racial politics in a historic moment suspended between the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, a moment when the president was engaged in one-to-one conversations about mounting tensions in Selma with Martin Luther King Jr. It seems plausible that the inaugural committee either did not recognize what it meant to invite a racially segregated choir to the nation’s ceremonial mainstage or did not find Mormonism’s anti-Black racism sufficiently objectionable. It may be that Johnson felt he had bigger battles to fight—with George Wallace, with Southern Democrats—and bigger stakes to consider in the rights and lives of African Americans. It may be that as westerners, from Utah, from a historically outsider culture, Mormons seemed to transcend the historic sectional divides onto which the nation had projected its racial politics. Or it may be that Johnson and his committee actually embraced the Mormon Tabernacle Choir performance as a chance for white citizens to indulge what Robin Bernstein would call a “holy obliviousness.” The choir held a space at the center of national politics where both they and the public could by silent agreement co-construct and indulge in a spectacle of racial innocence.

It is even more significant that the song that made the choir a national icon was “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” From its origins as a tribute to the radical abolitionism of John Brown through its transition by the hand of Julia Ward Howe in 1861 into an anthem for Union troops, “Battle Hymn” had by the 1950s detached from its earliest anti-racist origins and been reappropriated as a hymn of Cold War conservative nationalism. Evangelist Billy Graham had adopted it as the theme song for his “Hour of Decision” radio program in the 1950s and his crusades. In his use of “Battle Hymn,” Graham aligned the song’s sense of militant preparation for moral crisis with anti-Communist fervor. As John Stauffer and Benjamin Soskis write, he sought to “[inspire] Americans in their apocalyptic battle against international communism, [saying . . . ] ‘When you turn from your sins to Christ, you redeem America’ ” and to herald the “triumph of traditional American values.”14 The choir cannily sought to step out of its regional and religious specificity into the conservative Protestant national mainstream when it made “Battle Hymn” the signature element of its repertoire.

“Battle Hymn” had by 1961 receded from use as a hymn of the civil rights movement, overtaken in popularity by “We Shall Overcome.” Martin Luther King Jr. had referenced it passingly in numerous speeches during the early 1960s. But he returned to it with special emphasis in an extended riff on “Battle Hymn” at the conclusion of the Selma March to Montgomery, on March 24, 1965, just eight weeks after the all-white choir from an officially segregated religion had deployed “Battle Hymn” on the national mainstage. Selma marchers sang “Battle Hymn” as they entered the capitol, and King himself had concluded his speech with a recitation of the hymn’s first and second stanzas, wrenching the song back into its originating contexts of anti-racist militancy. Perhaps there was a limit to the contradictions some American audiences were willing to accept.15

Columbia Records and commercial audiences of the era showed no such qualms. From 1961 to 1968, the choir released six records—three with the Philadelphia Orchestra—in the Columbia Masterworks series, creating a middle-of-the-road repertoire of Americana that willed innocence to the implications of American historical music and anthems for the present political moment: Songs of the North and South (1961), which included “Battle Hymn,” “Dixie,” and “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child”; The World’s Great Songs of Patriotism and Brotherhood (1963); God Bless America (1965); This Land Is Your Land (1965); and Beautiful Dreamer (1967), a collection of songs by Stephen Foster, a key creator of the minstrel song genre. Perhaps the most egregiously contradictory release was the album Mormon Pioneers (1965), a collection of Mormon folk songs and hymns, which included a forty-eight-page booklet of essays, including an introductory essay by Columbia executive Goddard Lieberson, who extolled the “family” values represented by the choir and compared Mormons to other American minorities that had fled “bigotry,” “intolerance,” and “prejudice,” going so far as to draw a parallel between nineteenth-century mob persecutions of Mormons and the “brutality” visited on Native Americans.16 Columbia Records executive John McClure captured the place of the choir in its catalog in a letter of March 1968: “Thanks to the unique collaboration of our two organizations, you become increasingly each year a cultural necessity in millions of American homes.” Not just entertainment, but a “cultural necessity”—the choir offered a patriotism defined by willed obliviousness to contemporary political struggles, especially to the thorny moral responsibility entailed in institutional racism. The choir’s religious character served elementally in this bestowal of innocence by gesturing toward a transcendence of racial issues that cost whites nothing and left segregation and white supremacy completely intact.

A provocative artifact from this time period is coverage of presidential candidate George Wallace’s campaign trail visit to the Mormon Tabernacle on October 12, 1968. Candidates for the presidency from major political parties customarily spoke at the Tabernacle. Wallace’s American Independent Party bid drew substantial support in Utah, including the endorsement of high-ranking LDS Church official and former secretary of agriculture Ezra Taft Benson. He appeared before what the New York Times described as “an overflow crowd of more than 10,000,” which contrasted sharply with the decidedly smaller and less enthusiastic reception Wallace received elsewhere in the American West. Wallace was pleased with his reception. Speaking at the historic Tabernacle, the geographical center of religious Mormonism, Wallace told the crowd, “This is a high point of our travels. . . . We are alike—we see the dangers that confront the American people today.”17 Karl Rove, who grew up in Utah and attended the event, remembered:

Wallace was angry, belligerent, and nasty, and even to my untrained ears, a pure demagogue. A protester heckled, and the Alabama governor taunted him back, saying that if the protester lay down in front of Wallace’s limousine, it would be the last one he’d lie down for. The crowd screamed in agreement.18

Photos accompanying New York Times coverage convey an indelible image of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir performing behind Wallace, like back-up singers. Wallace sought spectacle, and both LDS Church leaders and the choir cooperated in the name of patriotic neutrality. Like the willed racial innocence of whiteness, this neutrality was not earned transcendence or the holy embrace of agonistic moral reasoning with one another, but a silent agreement not to see and not to challenge white supremacy but to give it a pass, as the Church had been given a pass on so many things mainstream white Americans found noncredible or distasteful.

But this silent agreement could not hold forever. As protests from university sports teams refusing to play Church-owned Brigham Young University teams mounted through late 1968, “the Mormon priesthood position came to be portrayed more frequently” in the press as “an affront” to a national consensus that had shifted in favor of “civil equality,” writes media scholar J. B. Haws.19 Historian Michael Hicks notes that internal correspondence reflects hesitation about using the Mormon Tabernacle Choir among members of the inauguration organizing committee, who cited the Church’s controversial stance on African American equality. But the choir did perform at Nixon’s January 1969 inauguration, and Nixon afterward wrote to thank them “for what you have come to mean to our country and for the sake of our country. Continue on.”20 Nixon recognized the role the choir played in providing the nation with a religious spectacle of transcendence that gestured beyond racial politics without demanding moral responsibility for white supremacy. That function was valuable enough for Nixon and others to forgo demanding accountability of the choir and the LDS Church for its own commitment to anti-Black racial segregation. The co-construction of innocence benefited both Mormons and white America: it benefited Mormons by allowing them to access the status, visibility, and respectability of the inaugural stage and presidential sanction, and it benefited white America by affirming the moral respectability of white supremacy and of silent agreements among whites not to trouble that supremacy.

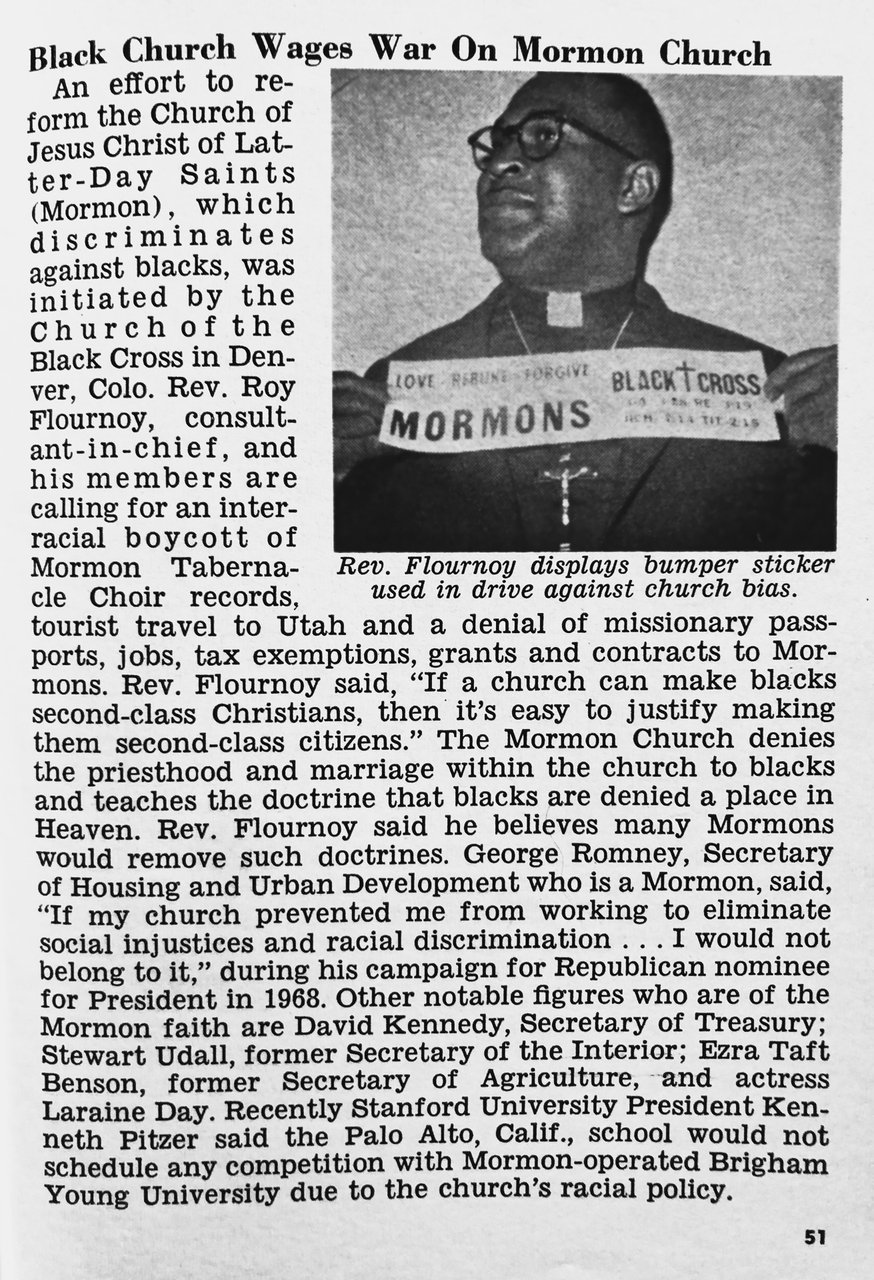

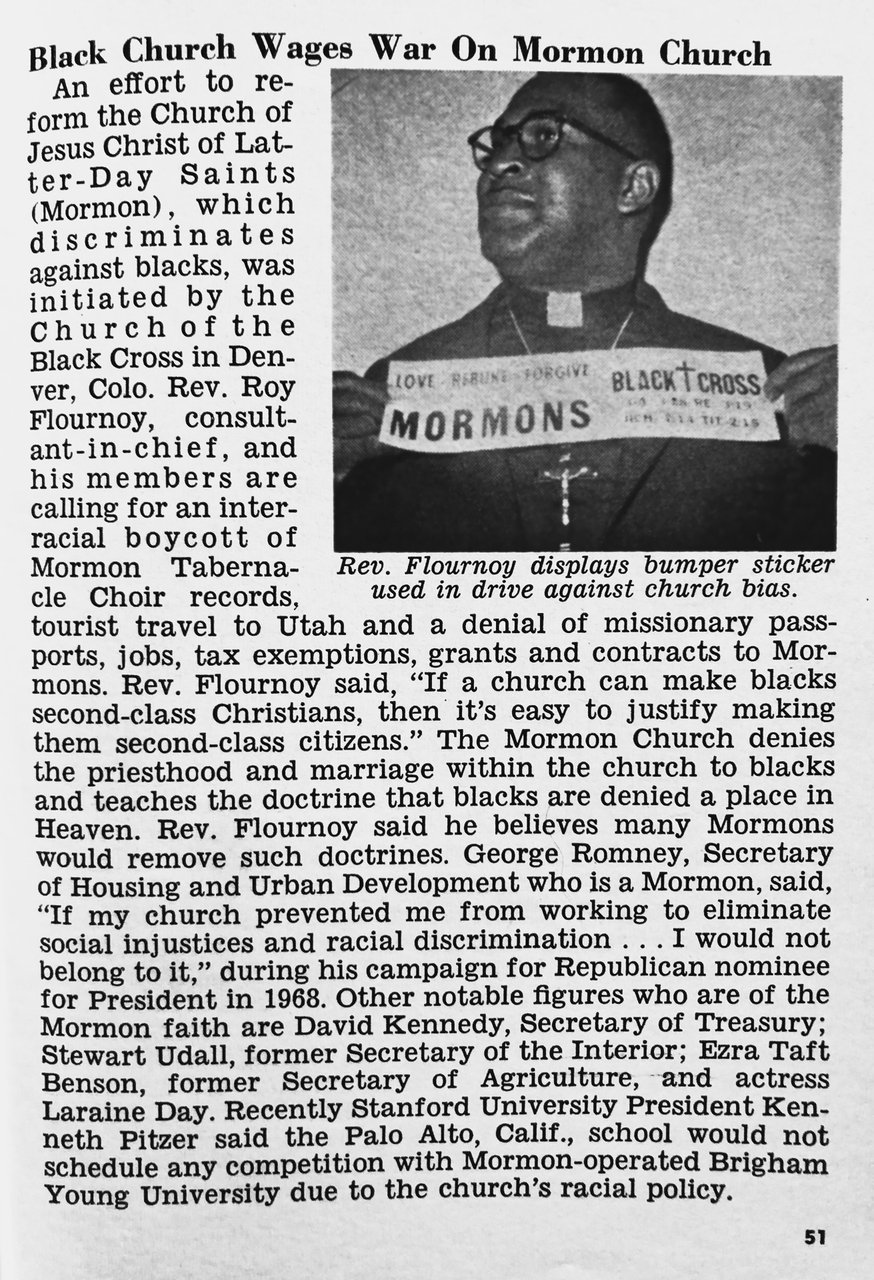

African American audiences were not willing to put up with these spectacles indefinitely. In Denver, the Reverend Roy Flournoy, founder of the Church of the Black Cross and author of works on Black theology, announced a boycott of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir and its products (as well as travel to Utah and an end to missionary passports, tax exemptions, and other benefits to Mormons) effective November 15, 1969. Rev. Flournoy and his efforts were featured in Jet magazine in January and February 1970, as shown in figure 4.1. Significantly, Flournoy refused to allow a disconnect between the Church’s religiously argued racial segregation and the standing of African Americans in civil society, telling Jet, “If a church can make blacks second-class Christians, then it’s easy to justify making them second-class citizens.”

Figure 4.1. Rev. Roy Flournoy of Denver, Colorado, publicizes his Mormon Tabernacle Choir boycott in Jet Magazine, January 8, 1970, and February 19, 1970.

Just weeks after Flournoy announced his boycott, on December 2, the choir auditioned and admitted an African American soprano named Marilyn Yuille, who performed immediately, on December 4. By January 1970, according to the New York Times, the choir had admitted two Black sopranos—Yuille and Wynetta Martin—and was considering a male tenor.21 But it would be eight years more before the Church rescinded its ban on Black ordination to the priesthood and Black access to sacred temple rites, a position that grew more strained and divergent from national consensus each year. The choir did not perform at Nixon’s swearing-in ceremony at the US Capitol at his second inauguration in 1973, but instead a group of thirty choir members performed in the White House for a postinauguration devotional. In fact, the choir did not return in any capacity until Ronald Reagan invited them to perform in his inaugural parade and ceremony in 1981, after the ban had officially ended.

The commercial staying power of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir owed not only to the spectacle of willed innocence it provided white Americans—“for the sake of our country,” as Nixon put it—but also to the stubbornness of the corporate leadership of Columbia Records, whose head, Goddard Lieberson, had steadfastly kept the label out of rock and roll, preferring Mitch Miller, Broadway, and classical through the end of his career in the early 1970s. But just as the choir’s popularity took a downturn, Mormon culture came through with a successor: the Osmond family.

The Osmonds got their start when four Osmond brothers—Alan, Wayne, Merrill, and Jay—started singing close barbershop harmonies for paying audiences in and around their hometown Ogden, Utah, to raise money to send two older Osmond brothers, Virl and Tom, on proselytizing missions for the LDS Church. After a failed attempt to audition for Lawrence Welk in Southern California, the family was “discovered” while visiting Disneyland and subsequently performed on “Disneyland After Dark” in 1962. From 1962 to 1969, five Osmond brothers (now including Donny) were regulars on the Andy Williams Show and headlined print advertisements for the program. After joining The Jerry Lewis Show in 1969, the group transitioned to bubblegum pop, scoring several top ten hits in the United States and the United Kingdom in 1971–1973. The Osmond family openly sought to use “Osmondmania” to the benefit of LDS Church growth, with some Osmond brothers opting to forgo proselytizing missions because they judged their singing careers more effective means of introducing potential converts to the faith. (A March 11, 1972, feature in the LDS Church–owned Church News captured the Osmond family leaving the LDS Church Office Building after a meeting with high-ranking Church officials.) The family, the Church News reported, received thousands of letters of fan mail each week including letters from fans inquiring about the Church, which they devotedly answered.22 As a solo act, Donny scored four top ten hits in 1971–1972 and attained Tiger Beat teen idol status. Marie’s first single, a cover of Anita Bryant’s “Paper Roses,” became a chart-topping country hit in 1973. Hit duets with Donny followed, and by 1976, the brother-and-sister duo had landed their own Friday night variety show on ABC, which ran through 1979.

The ascendance of the Osmond family facilitated a critical pivot in media representation of the LDS Church. In November 1969, following protests by African American athletes at the University of Texas El Paso and University of Wyoming, Stanford University suspended its athletic contests with Brigham Young University to protest racial segregation. On December 15, the Church issued an internal statement to clarify what it portrayed as “confusion” over its views on “the Negro both in society and in the Church.” The statement opened with a recitation of early LDS histories of persecution by mobs in nineteenth-century American frontier states, then asserted the view that the US Constitution was in the Church’s view a “sacred” document. “We believe the Negro, as well as those of other races, should have his full Constitutional privileges as a member of society,” the statement continued, “and we hope that members of the Church everywhere will do their part as citizens to see that these rights are held inviolate.” But it carved out a separate domain under constitutional law for “matters of faith, conscience, and theology.” The statement incorrectly asserted that Joseph Smith opposed Black ordination and portrayed the ban as the will of God as revealed to Mormon prophets, quoting current LDS Church President David O. McKay: “The seeming discrimination by the Church toward the Negro is not something which originated with man; but goes back into the beginning with God.”23 The Stanford decision and the subsequent Church statement received wide attention in the press, including critical scrutiny by both Time and Newsweek on January 19, 1970. The fullest criticism came from the weekly magazine Christian Century, which called the Church’s separation of civil and religious equality an unacceptable “moral dualism” and criticized its official rationales as an “incredibly primitive reassertion of obscurantist doctrine concerning race” and a reflection of contemporary Mormons’ enthrallment to “the literalist white supremacy” of past Mormon leaders.24 Christian Century and Wallace Turner of the New York Times continued to cover Mormon anti-Black racism in the early 1970s.

While the Church took modest internal steps to address its own racial issues, including organizing an official fellowship group for African American Mormons, it also undertook a new public relations effort focused on promoting the LDS Church as a champion of “families.” The Church’s emphasis on families derived in large part from a unique theology that held that family bonds were to persist in the afterlife. This theology as translated through the vernacular of American culture and politics also fostered a dedicated focus in Church programming and Mormon life on heterosexual, monogamous married couples with young and school-aged children. In 1972, the Church launched through its subsidiary television stations and production companies the “Homefront” series of public service announcements advocating time spent with family. Within four years, Church officials reported, the series was playing on 95% of American television stations.25 During the same time period, media profiles of prominent Mormon “success stories”—such as journalist Jack Anderson, golfer Johnny Miller, and hotel magnate Bill Marriott, scion of a large multigenerational Mormon family—ran in dozens of periodicals from Forbes to Newsweek, depicting their subjects as clean-living, dedicated “family men.”26 Even the New York Times, which along with the Christian Century had been the media organization to most consistently cover the Church’s racist policies, devoted a full-page human interest feature on June 4, 1973, to the Church’s “Family Home Evening Program.” As staff writer Judy Klemsrud put it:

To many casual observers, the American family of the mid-20th century appears headed down the drain in a swirl of divorce, drugs, venereal disease, alcohol, adultery and group sex. “Marriage is passe!” is a rallying cry of many young people. Children are passe, they say. The family is passe. But for at least one sizable group in American society, the family is still the thing. The group is The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormon), and their way of attacking delinquency and deteriorating morality is to strengthen family solidarity through a Monday night get-together in the home called the “family home evening.”

Klemsrud’s article implicitly mobilizes a racialized notion of wholesomeness that positions white patriarchal, heterosexual families against “delinquency” and “deteriorat[ion]” evidenced in behaviors associated in the white national imagination with counterculture, urban, and minority communities. The article featured an interview with and photographs of the Osmond family but did not mention the Black priesthood and temple ban.27

Media coverage of the Osmonds promoted the idea of Mormon innocence in three major ways. First, the Osmonds were celebrated as a “blue-eyed soul” alternative to groups like the Jacksons, who were viewed by white audiences through racializing prisms that associated soul with anti-Black stereotypes of sexual promiscuity. Teenaged Osmonds were also queried time and again on their dating interests and habits, focusing in on the sexual purity of Donny and Marie, Marie especially not being allowed to date by her religion and her older brothers. Finally, the media provided celebrity-magnitude amplification to this Church-grown public relations emphasis on Mormonism as the champion of “the family.” Features in Newsweek (September 3, 1973), Atlantic Monthly (October 1973), Rolling Stone (cover article, March 1976), and TV Guide (August 1976) connected the Osmond family’s success to its religiosity, including the religiously valued focus on the patriarchal, heterosexual, monogamously married family.28 “Each and every Osmond is a devout member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (sic), a fact that indelibly colors the image, lifestyle, and music of this most successful household,” wrote Tom Nolan in his six-page feature in Rolling Stone (with photographs by Annie Leibovitz) entitled “The Family Plan of the Latter-day Osmonds.” Nolan predictably positioned the Osmonds as a foil to the so-called counterculture: “While many rock stars are known to sniff coke, the Osmonds don’t even drink it.” Noting the “hermetic,” isolated, idyllic atmosphere of the “Land of Os,” Nolan did nothing to trouble it: he asked Donny about what kind of girls he liked but did not take issue in print with their support for anti-Black racial segregation.29

That silent agreement ended in February 1978, when Barbara Walters brought her production team to Osmond Studios in Orem, Utah, for an in-depth interview with twenty-year-old Donny and eighteen-year-old Marie. The interview opened with a sequence featuring the extended Osmond family—including patriarch George and wife Olive and their fifteen grandchildren—holding Family Home Evening on the set and with a voiceover by Walters reciting the commonplace media characterizations: “To understand the Osmonds is to know that they are Mormons,” she said. Their religious identity and emphasis on family stood behind their success as a “conglomerate of millionaires.” “They are also genuinely nice,” Walters intoned, “and that’s pretty refreshing all by itself.”30 Sitting down to probe Donny and Marie more closely, Walters asked deeper questions about Osmond—and, thus, Mormon—views on marriage, family, dating, and premarital sex. “Our religion is everything to us,” said Marie. Walters then asked the question that had never been asked of so high profile a Mormon in such a widely distributed, live media format:

bw: Look, I have to ask you something that I know that you have heard about, and if I don’t ask it people will wonder why I didn’t. And that is, in the strength of your religion, the whole business about Blacks not being allowed to be priests in the Mormon religion.

do: Mmm hmm.

bw: Tell me how you feel about it and what the explanation for that is, would you Donny?

do: You bet. [Looks at ground.] Well, I’m not an authority on the subject [looks sidelong at Walters, returns gaze to ground] but uh I will mention that uh we are not prejudiced people [looks sidelong at Walters, returns gaze to ground] we offer more I think than any other religion to the Black person [looks sidelong] [cut] and uh if you really want a good explanation from someone who has an authority about it you should really talk to the general authorities of our church. [Marie turns gaze from Donny to look at Walters, and nods affirmatively.] Um. They are not allowed to hold the priesthood in this [pause] right right now and I don’t know why but that’s the way the Lord wants it.

Walter’s lead-in—“if I don’t ask it people will wonder why I didn’t”—suggests something had shifted in the long-standing silent agreement of mutually affirmed innocence between overtly religious Mormon performers and the white American public, enough at least that it felt to Walters that her professional credibility could be impacted if she didn’t ask the question.

Donny Osmond’s answer to Walters suggests that the brother-and-sister pair had rehearsed for the question (as they did for every other aspect of their public appearances) and that they had done so in an exclusively Mormon environment. Donny is completely un-self-conscious as he expresses no objection to the ban: highly observant and politically conservative Mormons like the Osmonds would have considered public expression of dissent evidence of impiety. His attempt to draw a distinction between the Church’s anti-Black policy and general racial “prejudice” was also a commonplace of LDS rhetoric, including the Church’s formal 1969 statement on the ban. The claim that Mormonism “offer[ed] more to the Black person” than any other religion was also commonplace rhetoric among Mormons, premised on the belief that the LDS Church through the mechanism of “continuing revelation” to prophets offered the most authentic and complete religious truth and the most efficacious rites; “the Church is true” is how observant LDS people put it, and even a partial access to that “truth”—Black people could after all be baptized and learn Church doctrine—was “more” than “any other religion” could offer. This phrase, which exemplifies the “abstraction” of Black lives necessary to legal claims of white innocence, seemingly originated with a remark made by LDS Church President Joseph Fielding Smith to a Look magazine reporter in 1963, and persisted.31 In fact, Ruffin Bridgeforth, an African American Mormon and member of the Church’s “Genesis” fellowship group, made a similar remark to Jet magazine on May 25, 1978: “In this church a Black man can do more than he can in any other church.” Those who coached Donny and Marie had also provided them with a way to evade moral responsibility for the ban, as Donny’s carefully scripted repetition of the term “authority” indicates: “I’m not an authority on the subject,” he begins; “you should talk to the general authorities of our church.” Church leaders since the time of Brigham Young had often remarked that someday God could in fact permit Black ordination. Donny’s remark “in this [pause] right right now” is a stumbling allusion to this idea. But his concluding sentence, “I don’t know why but that’s the way the Lord wants it,” reiterates his commitment to the orthodox Mormon view of prophetic leadership as inerrant, as God’s own foregone conclusion. Osmond’s answer to Walters’s question exemplifies legal-rhetorical tactics of white innocence such as “originalism” and “helplessness” identified by legal scholar Thomas Ross that allowed whites to disclaim responsibility for racism by characterizing it as the will of an original power—whether the authors of the US Constitution or God themself.

Just as the Mormon Tabernacle Choir had traded on “innocence” to play an iconic role for white American audiences in the 1950s and 1960s, the Osmonds sought to maintain innocence to hold a place in 1970s pop culture. But the social and media contexts in which they attempted to do so had changed over the decades. The silent agreement to overlook Mormonism’s explicit anti-Black segregation expired by 1978. So did the priesthood and temple ban. As Donny and Marie sat down with Barbara Walters, high-ranking LDS Church leaders were preparing to end anti-Black restrictions on full Church participation, a change announced on June 8, 1978.32

Performances of white innocence by overtly religious performers allowed national audiences to enjoy, bond around, and experience affirmation of their moral superiority while ignoring segregation. Donny and Marie’s cringeworthy answers to Barbara Walters in 1978 are embarrassing to thoughtful Mormons for what they reveal about our own insularity and incredibility, but they say just as much about bad faith and duplicity on the part of mainstream white audiences. “I believe in 1978 / God changed his mind about Black people,” sings Elder Price, the protagonist in the Broadway hit musical Book of Mormon (2011). The line is a major laugh-getter; the play has now grossed over $500 million. In the musical, as in the 1960s and 1970s, the Mormon willingness to voice out loud and without reservation white supremacist sentiments held broadly but in silence by mainstream American Christians made our religion good entertainment. To this day, mainstream audiences have been happy to keep Mormons as the butt of the national joke.

There were, of course, Mormons who were in 1965 and 1978 using public venues to ask much harder questions of their faith, their leaders, and American racism. I will profile them in chapter 5. Their experience reflects the ongoing struggle within the Mormon movement between those who sustain the inerrancy of Church leaders by keeping silence around elements of Mormonism that have been morally objectionable and those who believe that Mormonism’s better angels require us to keep seeking and naming and repairing our own shortcomings as a people. Our struggle in this way is no different than that of any other American Christian denomination—or American society writ large. But along the way Mormons learned that so long as we mirrored back white American fantasies of innocence and moral superiority, we would be excused from answering the hard questions that should define honorable participation in a civil society. “They have destroyed and are destroying hundreds of thousands of lives and do not know it and do not want to know it,” wrote James Baldwin of white innocence. “They are in effect still trapped in a history which they do not understand and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it.”33 Because it served white supremacy, Mormons were kept in a state of innocence like children, our lack of credibility an open secret, the butt of the joke, but a small cost (or so it seemed) to pay for the benefits of assimilation, especially if it meant Mormon missionaries—our sons, our brothers, our nephews—found more success in the proselyting field because of the Osmonds or the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, or at least were not treated so discouragingly on the doorstep.

Mormons have scarcely begun to count the costs to our own humanity of more than a century of persistent internal anti-Black segregation, nor of the forty years of denial—characterized at times by the same proud ignorance evidenced by Donny and Marie—let alone the costs exacted by this willed innocence on our coreligionists of color. At the time of my writing, Donny Osmond still defends the Church’s internal segregation as the will of God.34 Mormonism has observed the fortieth anniversary of the ban with no official apology from the Church for its errors and a suffocating stasis around anti-Black racism among orthodox believers, most of whom still refuse to acknowledge that we were wrong. As one who grew up idolizing Donny and Marie—they were the only people like me I saw on television—and feeling just about the same way they did about the priesthood and temple ban, I can say that the mainstream white audiences who bought into and subsidized our white “innocence” did us no favors.

1.James Baldwin, “My Dungeon Shook: Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation,” in The Fire Next Time (New York: Dial Press, 1963), 21.

2.K. D. Guitterrez, “White Innocence,” International Journal of Learning 12.10 (2005): 223–229; Dalia Rodriguez, “Investing in White Innocence: Colorblind Racism, White Privilege, and the New White Racist Fantasy,” in Teaching Race in the 21st Century: College Teachers Talk About Their Fears, Risks, and Rewards, ed. L Guerreo (New York: Palgrave, 2008), 123–124; Jennifer Seibel Trainor, “‘My Ancestors Didn’t Own Slaves’: Understanding White Talk About Race,” Research in the Teaching of English 40.2 (2005): 140–167.

3.Robin Bernstein, Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood and Race From Slavery to Civil Rights (New York: New York University Press, 2011), 6.

4.White innocence does not always present in this way, as Gloria Wekker has recently observed in her study of white supremacy among the Dutch; there is also “smug ignorance,” which can present with rage and violence. See Gloria Wekker, White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 18.

5.J. B. Haws, The Mormon Image in the American Mind: Fifty Years of Public Perception (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 47–73.

6.Jan Shipps, Sojourner in the Promised Land: Forty Years Among the Mormons (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000), 100.

7.Haws, 22–29; Michael Hicks, The Mormon Tabernacle Choir: A Biography (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2015), 118.

8.Hicks, 115.

9.Kirk Johnson, “Mormons on a Mission,” New York Times, August 20, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/22/arts/music/22choir.html?pagewanted=all; last accessed January 30, 2018.

10.Haws, 36.

11.Haws, 60.

12.Haws, 50–51.

13.Lyndon B. Johnson, “Annual Message to Congress on the State of the Union, January 4, 1965,” The American Presidency Project, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=26907, last accessed January 30, 2018.

14.John Stauffer and Benjamin Soskis, The Battle Hymn of the Republic: A Biography of the Song That Marches On (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 230, 242.

15.John Stauffer and Benjamin Soskis, The Battle Hymn of the Republic: A Biography of the Song That Marches On (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 230, 242.

16.Hicks, 125.

17.Roy Reed, “Wallace Seeks Mormon Votes; Draws Big Tabernacle Crowd,” New York Times, October 13, 1968, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1968/10/13/317688762.html, last accessed January 30, 2018.

18.Karl Rove, Courage and Consequence: My Life as a Conservative in the Fight (New York: Threshold Books, 2010), 11.

19.Haws, 59.

20.Hicks, 132.

21.Wallace Turner, “Mormon Liberals Expect No Change,” New York Times, January 25, 1970, http://www.nytimes.com/1970/01/25/archives/mormon-liberals-expect-no-change-smith-mckays-successor-backs.html, last accessed January 30, 2018; Salt Lake Tribune, February 21, 1970.

22.“35 Memorable Photos From the Church News Archives,” Deseret News, September 29, 2014, https://www.deseretnews.com/top/2740/2/Donny-Osmonds-wedding-35-memorable-photos-from-the-LDS-Church-News-archives.html, last accessed January 30, 2018.

23.Harris and Bringhurst, 82–83.

24.Stephen W. Stathis and Dennis L. Lythgoe. “Mormonism in the 1970s: Popular Perception,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 10.3 (1977), 107.

25.Haws, 79–81.

26.Haws, 83–85.

27.Judy Klemsrud, “Strengthening Family Solidarity with a Home Evening Program,” New York Times, June 4, 1973, 46, http://www.nytimes.com/1973/06/04/archives/strengthening-family-solidarity-with-a-home-evening-program.html, last accessed January 30, 2018.

28.Sara Davidson, “Feeding on Dreams in a Bubble Gum Culture,” Atlantic Monthly, October 1973: 72. See also Haws, 84.

29.Tom Nolan, ““The Family Plan of the Latter-day Osmonds,” Rolling Stone, March 11, 1976, 46–52.

30.“The Barbara Walters Special: Donny and Marie Osmond,” February 1978, published February 14, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bPWIEfmPYxo, last accessed January 30, 2018.

31.Matthew L. Harris and Newell G. Bringhurst, eds., The Mormon Church and Blacks: A Documentary History (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2015), 83n104.

32.See especially Edward Kimball, “Spencer W. Kimball and the Revelation on Priesthood,” BYU Studies 47.2 (2008): 5–78; Mark L. Grover, “The Mormon Priesthood Revelation and the Sao Paulo, Brazil Temple,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 23.1 (1990): 39–53, http://www.dialoguejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/sbi/articles/Dialogue_V17N03_25.pdf, last accessed January 30, 2018.

33.James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time (New York: Dial Press, 1963), 21.

34.Donny Osmond, “My Beliefs: Questions and Answers,” donny.com, https://donny.com/my_beliefs/do-you-honestly-think-black-people-worldwide-dont-deserve-public-apology/, last accessed January 30, 2018.