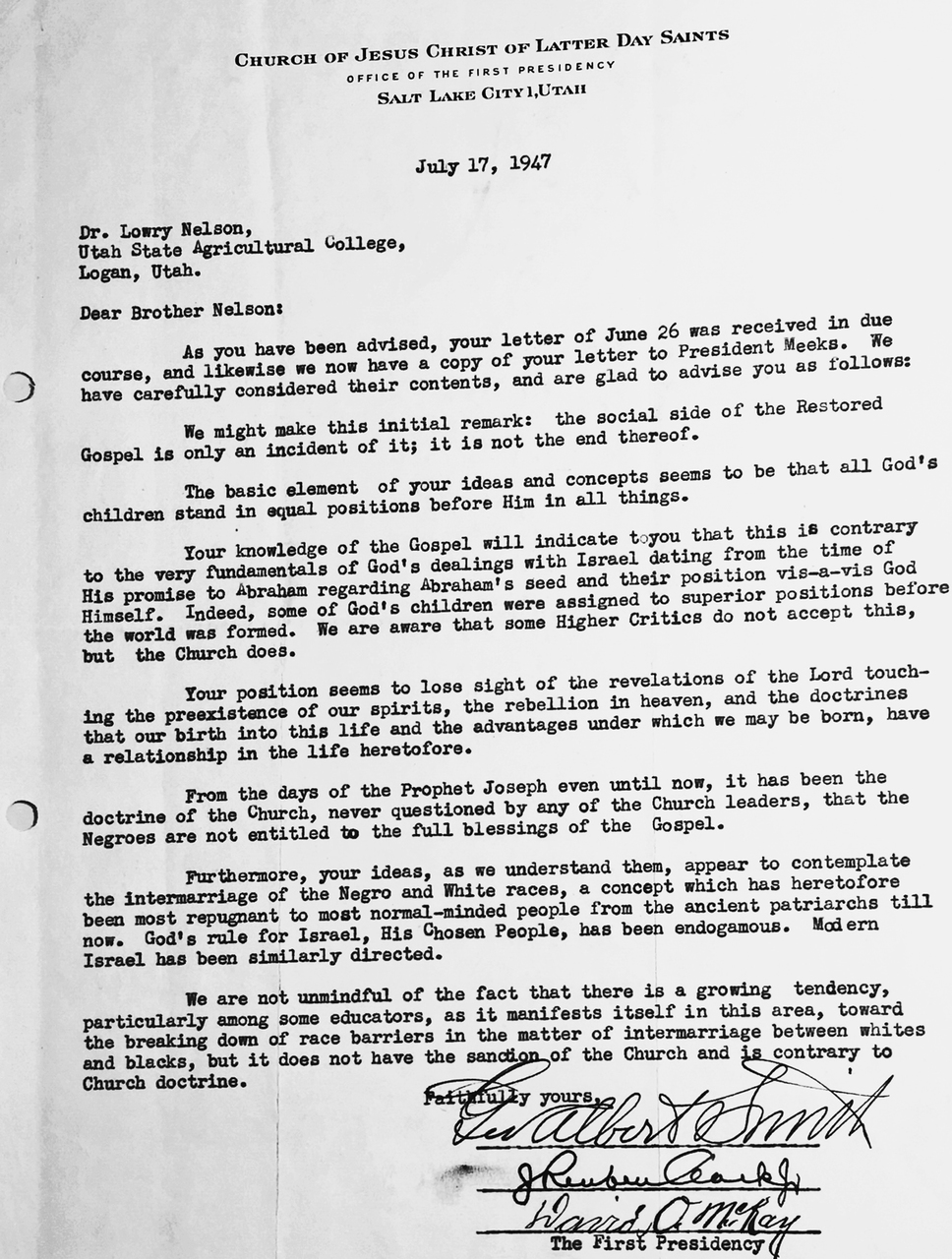

Figure 5.1. LDS Church First Presidency letter to Lowry Nelson, July 17, 1947.

Courtesy of Marriott Special Collections Library, University of Utah.

No one is born white—it is only possible to become white, to be enlisted and acculturated into whiteness, and white American Christian churches are among the many venues for that acculturation. Just as white Christians develop silent agreements among ourselves to define morality in individual terms that take no responsibility for systematic anti-Black racism, white Christian churches develop means for managing and disciplining adherents who do take on anti-Black racism in a serious and discomfiting way. Marginalizing or repressing anti-racist dissent is necessary to maintaining a hold on the story that anti-Black racism is how it has always been and how God intends for it to be or, at least, is content enough with it not to intervene. The attribution of intentionality and inevitability to the systems of white supremacy that hurt Black people takes shape in more conservative white American Christian contexts as belief in infallibility—whether in the text of the Bible, the pope, or the leaders of the LDS Church. Infallibility kills: it kills the bodies of those marked expendable, it kills relationships with those who dissent, and it kills the souls who suffocate on their own ignorance and privilege. It kills courage, it kills hope, it kills faith, and it kills the kind of historical memory that helps a religious community understand itself and find its next steps toward holiness.

It is easier take a principled stance as a white American Christian against white supremacy and anti-Black racism in the nation at large than to confront the quiescence mistaken for reverence that preserves the workings of white supremacy in the church. Witness the case of Michigan Governor George Romney, who took bold and principled public stands against anti-Black racism in the secular world. Just days after Selma, in 1961, Governor Romney helped organize and walked at the head of a march of ten thousand demonstrators in Detroit. He provided state support and full endorsement for the Martin Luther King Jr.–led Detroit Walk to Freedom on June 23, 1963; he did not walk in the Sunday event due to his observance of the Sabbath, but he did lead a march with NAACP leaders through the suburb of Grosse Pointe just a few days later. His outspoken stance earned him private pushback from high-ranking Church leaders, in particular, a member of the Church’s Quorum of the Twelve Apostles named Delbert Stapely, who in January 1964 had written a personal letter to Romney conveying concern on the part of several others unnamed that his public support for civil rights was not aligned with the teachings of Joseph Smith and warning him that activism on Black human and civil rights causes had, in several recorded instances, led to untimely death for the activist.1 In no moment, though, was the membership or worthiness of George Romney, the most prominent Mormon in America besides the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, put into question. Nor did Romney openly question the Church’s segregationist policies. He did go so far as to call out “social injustice based on race and color” during a Sunday meeting of an LDS congregation in faraway Anchorage, Alaska, when he was on the presidential campaign trail in February 1967, a statement cannily recognized by the New York Times as Romney’s effort to differentiate his “personal position” from that of the Church itself and demonstrate his principled independence from its teachings on matters of racial equality.2 He went even further during his term of service as President Nixon’s secretary of housing and urban development by refusing to consider government support for housing projects that did not support racial integration, earning strong pushback from Nixon that contributed to Romney’s loss of his position.

But with his own Church Romney had struck a silent agreement: he would conduct himself as he felt his principles demanded in the realm of politics, and he would allow them to conduct Church business as they saw fit. Maintaining public silence on discriminatory Church policies while working assiduously to advance desegregation and anti-discrimination in the public sphere was Romney’s way of striking a tenuous balance between honoring his conscience and honoring religious vows he had made to “consecrate” his time and resources to the Church and sustain its leaders. A thousand painstaking calculations must have factored into his choices, as they do for every Mormon who finds him/her/theirself at odds for reasons of conscience with the institutional LDS Church. It matters in this calculus whether you are white, Black, or brown; male or female; straight or LGBTQ; rich or poor; married or not; highly observant or less so. It matters whether you have a current volunteer position in the Church and what that position is—whether one of greater or lesser responsibility. It matters who the local leaders are who are charged with assessing your personal worthiness. It matters whether your ancestors came across the plains as pioneers and where Brigham Young sent them after they did—Idaho, Arizona, southern Utah, Mexico; whether they practiced polygamy; and how closely they maintained their ties with the elite networks of families who have constituted the majority of the Church’s leadership. It matters where you work, for whom, and how LDS social networks influence your customer base. And it matters how you express your dissent: written or oral; public or private; book, newspaper, or television; time, place, and manner; down to the tone of your voice and your vocabulary, grammar, and punctuation—it matters. All of these and more factor into the complex calculus of conscientious dissent in the contemporary Mormon movement, especially inasmuch as Mormonism has sought to hold on to the modicum of social acceptance it gained in the mid-twentieth century.

This is in many respects remarkable for a faith tradition that began as an open rejection of and revolt against mainstream American Protestantism, just as Protestantism itself began as a revolt against Catholicism. Eventually, though, the broadly distributed “charisma” of the movement, which empowered every believer to enjoy individual access to revealed truth, gave way to a hierarchical order that centralized charismatic and prophetic authority into a limited number of Church leaders—in Protestantism and Mormonism alike. Tensions between the democratic and authoritarian tendencies of Mormonism persisted, mediated sometimes by the so-called Law of Common Consent, articulated by Joseph Smith in 1830 and commemorated in the LDS scripture The Doctrine and Covenants, section 25, and sometimes leading to the formation of dozens of splinter groups and offshoot movements. Those who remained with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints entered in what Mormon historians Linda Thatcher and Roger Launius have characterized as a “contract”: “the assumption that personal feelings must bow below that of the church, that no disagreement be allowed to harm the church.” Those who tested the limits of this contract tended, according to Thatcher and Launius, to have some footing or standing in the secular world, to believe that they stood for an “honest minority” opinion, or to feel that the affordances of belonging were no longer worth the costs of submission. Given the political, economic, and social dimensions of Mormon community life, these affordances can include access to education, employment, and marriage as well as continuity of family and community relations. The costs of breaking the contract in a way that leads to excommunication and shunning could be stark, especially in pre-assimilation Mormon communities. Consequently, dissent was stigmatized in the twentieth-century LDS Church, preventing, according to Thatcher and Launius, the development of healthy tolerance for “social conflict.”3

Every white American Christianity exacts its own kind of silent agreements with its memberships to preserve its racial innocence and, in exchange, to convey certain rewards. Mormonism has provided for people of all economic classes and national, racial, and ethnic identities “a theological and ritual salve for profound personal losses but also a resource that promised middle-class stability, security, social mobility, . . . access to education and broadened perspectives,” and even continuity of kinship networks, language, and identity through Church-sponsored social groups, schools, universities, colleges, and labor/employment programs. But as I observed with Maori Mormon womanist scholar Gina Colvin in Decolonizing Mormonism:

These modest affordances came at a cost. LDS institutional spaces were deeply structured by mid- and late-twentieth century American Mormon conservatism, which was itself driven in part by the LDS Church’s hunger to transform itself from an outlier sect to a mainstream American Protestant church. These spaces, from wardhouses to Church-sponsored university classrooms, did not support nor equip Mormons to participate in the critical conversations about power and resources colonized peoples around the world were engaging in from the 1940s and 1950s onward. Education in LDS Church colleges and universities and the culture of LDS congregations focused on preparing a globalizing membership to assume local responsibility for the administration of LDS Church units according to American bureaucratic norms. Limited cultural accommodation came at the cost of surrendering critique and sustaining a false sense of political innocence. Stability interlocked with the status quo.

Twentieth-century Mormonism brokered a sort of compact with its global membership. “This compact allowed limited accommodations for traditional cultural practices and identities and promised access to worldly opportunities and moments of spiritual transcendence, to stable supportive institutions, and to theological and social comfort in the face of loss and pain,” in our view. “But the cost of this accommodation and access was obedience to LDS Church hierarchy and a bracketing of critique of the status quo, including the forms of systematic and structural violence and inequality that contributed to or created loss and pain.”4

In places where the Church or networks of LDS people also maintained a degree of power over political, social, material, environmental, and economic resources, this contract or compact—that critique would be exchanged for the affordances of belonging—was leveraged to secure consent from local peoples to projects that may have compromised their dignity, autonomy, or political and economic values. Hokulani Aikau writes powerfully in A Chosen People, a Promised Land of how Church leaders utilized an “ideology of faithfulness”—that is, “faithfulness to church business and managerial practices”—to extract consent from local peoples to the use or appropriation of indigenous land and labor in the service of LDS enterprises, religious and secular.5 The Church’s twentieth-century growth put distance between international leadership and local congregations, constraining what had been within Mormon tradition the possibility of voicing dissent to leaders in the context of familial or community relations. Church leaders maintained the “illusion of personal relationships” through affectionate norms in their public addresses and internationally televised conferences but relied ever more heavily on the ideology of faithfulness to elicit cooperation and marginalize dissent.

This chapter will explore the nature of the silent agreement between LDS Church leaders and members and the conditions under which Mormons have publicly dissented from the Church’s anti-Black racism and segregation. Its goal in part is to challenge the idea that anti-Black racism was inevitable—in Mormonism, or in any white American Christian faith. There were always believers who found within faith another way of seeing and being. Their stories matter because they rescue our hearts and minds from the suffocating pretenses of inevitability and infallibility and inspire us to think otherwise. This chapter seeks to reconstruct and make available a lost archive of conscientious objection by white Mormons to the Church’s anti-Black segregation and discrimination. Because information and publication in the Mormon movement has been from the 1950s to the 2000s largely managed by the institutional LDS Church, and because the Church itself does not have a professional clergy or professional theological schooling that can support reasoned discussion and conflict, these statements have never been a part of any LDS curriculum or canon. As a lifelong member of the LDS Church and a scholar of race and gender, I was not even aware of them until I researched this book. They constitute an archive of unorthodox lay theologies that broaden our ways of being Mormon to include models of persistent, unapologetic objection to anti-Black racism that refuse racial innocence. (Because they are not broadly accessible, I will use this chapter to provide longer excerpts from the original documents.) But they also encourage us to reflect critically on how the ability to protest racism and stay in good standing in the church is conditioned by privilege, and they vest those of us who do experience privileged identities within Mormonism and other predominantly white Christian faiths with a responsibility to leverage that privilege as meaningfully as possible.

Born in 1893 and raised in rural Ferron, Utah, to a multigenerational white Mormon family, Lowry Nelson earned degrees from Utah State University (then Agricultural College) and the University of Wisconsin. After working for state agriculture agencies, he joined Brigham Young University faculty and served as a dean of applied sciences. He left Brigham Young University in 1934 after having been reported to high-ranking church authorities for stating to a colleague that immortality was a hypothesis not testable by scientific means. After serving various rural relief agencies and projects during the 1930s, he took a faculty position in sociology at the University of Minnesota, during which time he conducted sociological studies of the Caribbean—including Cuba—for the Department of State, eventuating in the publication of his book Rural Cuba (1950). (He would return to Cuba during the 1960s for six years to study life after the Cuban Revolution.) In addition to his academic writing and publishing, Nelson wrote occasionally for the Nation, maintained an extensive correspondence, and wrote poems.

On June 20, 1947, President Herbert Meeks of the Church’s Southern States Mission, a childhood friend of Nelson’s, wrote to Nelson at the University of Minnesota:

I would appreciate your opinion as to the advisability of doing missionary work particularly in the rural sections of Cuba, knowing, of course, our concept of the Negro and his position as to the Priesthood, Are there groups of pure white blood in the rural sections, particularly in the small communities? If so, are they maintaining segregation from the Negroes? The best information we received was that in the rural communities there was no segregation of the races and it would probably be difficult to find, with any degree of certainty, groups of pure white people.6

The query came in a critical decade for Mormon scholars and writers, a decade in which out-migration, increased access to education, and moderate accommodation of US norms on the part of LDS people ended cultural isolation and contributed to a new capacity for critical reflection on Utah Mormon experience. This so-called Lost Generation, in terms first used by Mormon literary historian Edward Geary, saw the emergence of writers and works such as Vardis Fisher’s Harper prize–winning novel Children of God (1939), Virginia Sorenson’s A Little Lower Than the Angels (1942), and Maureen Whipple’s The Giant Joshua (1941), a critical reflection on Mormon polygamy, their plotlines often depicting a younger protagonist grappling with the weight of Mormon authoritarianism and Mormon history and the isolation of rural Mormon life.7 Historian Fawn Brodie was excommunicated after her publication of No Man Knows My History (1945), a frank, scholarly quality biography of Joseph Smith Jr. Grassroots historian Juanita Brooks, a southern Utah organic intellectual, published with the assistance of the Huntington Library, Wallace Stegner, and Stanford University Press a direct, nonhagiographic history of the Mountain Meadows Massacre (1950), an ambush and mass killing of white emigrants through southern Utah ordered (as Brooks’s research showed) by top-ranking Church leaders but blamed on local indigenous people and Mormon renegades. While the book received praise from American studies luminaries like Henry Nash Smith for its “probity,” even Stanford University Press’s director warned Brooks that she might be excommunicated. She said in response: “I do not want to be excommunicated from my church for many reasons, but if that is the price that I must pay for intellectual honesty, I shall pay it—I hope without bitterness.” Brooks’s father had offered her advice that pertained to her entire “Lost Generation” of newly critical LDS thinkers and writers, comparing the position of the loyal dissident writer to the cowboy who rides “not in the middle of the herd,” nor “abandon[s] it altogether,” but “ride[s] on the edge where she might be able to alter its course.”8

From his position on the edge of the herd—as an observant multigenerational Mormon in a secular university far outside the Mormon corridor—Nelson may indeed have hoped to alter its course. His June 26 response to Meeks reflects honest surprise that customs and folklore mitigating against welcoming Black Mormons into full fellowship had taken on the status of doctrine:

The attitude of the Church in regard to the Negro makes me very sad. Your letter is the first intimate I have had that there was a fixed doctrine on this point. I had always known that certain statements had been made by authorities regarding the status of the Negro, but I had never assumed that they constituted an irrevocable doctrine. I hope no final word has been said on this matter. I must say that I have never been able to accept the idea, and never shall. I do not believe that God is a racist. But if the church has taken an irrevocable stand, I would dislike to see it enter Cuba or any other island where different races live and establish missionary work. The white and colored people get along much better in the Caribbean and most of Latin American than they do in the United States. Prejudice exists, there is no doubt, and the whites in many ways manifest their feelings of superiority, but there is much less of it than one finds in USA, especially in our South. For us to go into a situation like that and preach a doctrine of “white supremacy” would, it seems to me, be a tragic disservice. I am speaking frankly, because I feel very keenly on this question. If world brotherhood and the universal God idea mean anything, it seems to me they mean equality of races. I fail to see how Mormonism or any other religion claiming to be more than a provincial church can take any other point of view, and there cannot be world peace until the pernicious doctrine of the superiority of one race and the inferiority of others is rooted out. This is my belief.

Writing as a sociologist, Nelson also upbraided Meeks for the idea that there was “pure” whiteness. He praised what the Church could provide rural communities through its lay priesthood structure and high level of organization in terms of social infrastructure, leadership development, and even self-sufficiency, but weighed the value of that against its racism:

Because I think our system of religious organization could serve the rural Cuban people as perhaps no other system could, I am sad to have to write you and say, for what my opinion is worth, that it would be better for the Cubans if we did not enter their island—unless we are willing to revise our racial theory. To teach them the pernicious doctrine of segregation and inequalities among races where it does not exist, or to lend religious sanction to it where it has raised its ugly head would, it seems to me, be tragic. It seems to me we just fought a war over such ideas. I repeat, my frankness or bluntness, as you will, is born of a fervent desire to see the causes of war rooted out of the hearts of men. What limited study I have been able to give the subject leads me to the conclusion that ethnocentrism, and the smugness and intolerance which accompany it, is one of the first evils to be attacked if we are to achieve the goal of peace.

A handwritten note from Nelson to his wife found on the back of the author’s copy, now held in Special Collections at the University of Utah, provides insight into Nelson’s frame of mind. “I was so angered by the complacency of the Meeks letter, I had a hard time containing myself.”

Nelson did not, in fact, contain himself. He copied his response to Herbert Meeks to LDS Church President George Albert Smith, with the following cover:

Perhaps I am out of order, so to speak, in expressing myself as I have. I have done so out of strong conviction on the subject, and with the added impression that there is no irrevocable church doctrine on this subject. I am not unaware of statements and impressions which have been passed-down, but I had never been brought face to face with the possibility that the doctrine was finally crystallized. I devoutly hope that such crystallization has not taken place. The many good friends of mixed blood—through no fault of theirs incidentally—which I have in the Caribbean and who know me to be a Mormon would be shocked indeed if I were to tell them my Church relegated them to an inferior status. As I told Heber, there is no doubt in my mind that our Church could perform a great service in Cuba, particularly in the rural areas, but it would be far better that we not go in at all, than to go in and promote racial distinction. I wanted you to know my feelings on this question and trust you will understand the spirit in which I say these things. I want to see us promote love and harmony among peoples of the earth.

Nelson’s letter to Smith reflects the deference to hierarchy—“perhaps I am out of order”—expected of an observant Latter-day Saint. But he also boldly claims for himself a place within the Protestant tradition of the priesthood of all believers, that is, the idea that every believer has the right to study and interpret the sacred texts of the tradition and develop their own understanding. Nelson was in fact correct that over the course of almost one century the Church had abandoned its original practice of ordaining Black men to the priesthood, denied its own history, and instead gradually consolidated with the formal correlation of institutional priesthood programs in the early twentieth century first a policy against ordination and then, through accretion and repetition without interrogation or counterpoint, religious folklore that finally assumed the stature of doctrine. Rather than lend his silent assent to the inerrancy of the doctrine, Nelson emphasizes its historicity, its contingency—“I had never been brought face to face with the possibility that the doctrine was finally crystallized.” He holds both to historical memory and to an essential commitment to humane and religious principles—“love and harmony”—that transcend doctrine.

President Smith and his counselors, David O. McKay and J. Reuben Clark, responded on July 17:

The basic element of your ideas and concepts seems to be that all God’s children stand in equal positions before Him in all things. Your knowledge of the Gospel will indicate to you that this is contrary to the very fundamentals of God’s dealings with Israel dating from the time of His promise to Abraham regarding Abraham’s seed and their position vis-a-vis God Himself. Indeed, some of God’s children were assigned to superior positions before the world was formed. We are aware that some Higher Critics do not accept this, but the Church does.

Here, President Smith and his counselors reassert an originalist, counterhistorical view of scripture, openly rejecting the rational, historicist “higher criticism” popularized in university-based theology in the nineteenth century and reasserting the Church’s claim that its practices honor an intentional godly pattern revealed directly and unchanged from ancient times, or even earlier—premortality. They continue to assert Mormonism’s distinctive doctrine, established in books of scripture such as the Book of Mormon and the Pearl of Great Price and reaffirmed in 1918 in a later-canonized revelation to LDS Church President Joseph F. Smith, that souls were created in a premortal sphere and developed a body of experience pertinent to their embodied lives on earth:

Your position seems to lose sight of the revelations of the Lord touching the preexistence of our spirits, the rebellion in heaven, and the doctrines that our birth into this life and the advantages under which we may be born, have a relationship in the life heretofore.

Even as they correct Nelson for “los[ing] sight” of this revealed doctrine, Smith, Clark, and McKay “lose sight” of and misstate LDS Church history pertaining to Black ordination:

From the days of the Prophet Joseph even until now, it has been the doctrine of the Church, never questioned by any of the Church leaders, that the Negroes are not entitled to the full blessings of the Gospel.

They close by reasserting the Church’s opposition to interracial marriage as a matter not only of social “normalcy” but also of “Church doctrine”:

Furthermore, your ideas, as we understand them, appear to contemplate the intermarriage of the Negro and White races, a concept which has heretofore been most repugnant to most normal-minded people from the ancient patriarchs till now. God’s rule for Israel, His Chosen People, has been endogenous. Modern Israel has been similarly directed. We are not unmindful of the fact that there is a growing tendency, particularly among some educators, as it manifests itself in this area, toward the breaking down of race barriers in the matter of intermarriage between whites and blacks, but it does not have the sanction of the Church and is contrary to Church doctrine.

Faithfully yours,

Geo. Albert Smith

J. Reuben Clark, Jr.

David O. McKay

The First Presidency9

Figure 5.1. LDS Church First Presidency letter to Lowry Nelson, July 17, 1947.

Courtesy of Marriott Special Collections Library, University of Utah.

As shown in figure 5.1, the tenor of the final sentence is unmistakably personal: Smith, Clark, and McKay call out Nelson’s position as a university-based sociologist and reject his effort to apply rational, historicized understandings of human organization to the timeless patterns assigned to “Modern Israel.” The closing line that support for intermarriage is “contrary to Church doctrine” is in fact a warning. The catechism of questions asked by local Church leaders to ascertain a member’s “worthiness” to participate in LDS temple worship had since 1934 probed whether members “sustained” and exercised loyalty to Church leaders.10 To publicly express opinions “contrary to Church doctrine” could be viewed by some local Church leaders as a failure to “sustain” Church leaders and thus lead to a member’s loss of access to authority and sacred rites. Nelson would have understood this as a threat to his membership.

But he did not run, nor did he yield. Nelson responded again on October 8, having been delayed by late summer travel but also, perhaps, by what he described as his “disappointment” upon receiving the letter. He “never before had to face up to this doctrine of the Church relative to the Negro,” bits and pieces of which had surfaced in various religious settings over the years:

I remember that it was discussed from time to time during my boyhood and youth, in Priesthood meetings or elsewhere in Church classes; and always someone would say something about the Negroes “sitting on the fence” during the Council in Heaven. They did not take a stand, it was said. Somehow there was never any very strong conviction manifest regarding the doctrine, perhaps because the quesiton was rather an academic one to us in Ferron, where there were very few people who had ever seen a Negro, let alone having lived in the same commuity with them. So the doctrine was always passed over rather lightly I should say, with no Scripture ever being quoted or referred to regarding the matter, except perhaps to refer to the curse of Cain, or of Ham and Canaan.

Nelson expressed his personal reservations about the way Old Testament scripture had been marshaled to explain race, especially since, as a professional sociologist, racialization fell within his field of academic study. His professional training, he explained, had shown him how “ethnocentrism” formed and reformed in human societies across time, implying carefully that what the First Presidency had insisted on as the doctrinal rendition of a God-intended pattern was instead the product of predictably human behavior. He continued:

Once these things get written down—institutionalized—they assume an aura of the sacred. . . . So we are in the position, it seems to me, of accepting a doctrine regarding the Negro which was enunciated by the Hebrews during a very early stage in their development. Moreover, and this is the important matter to me, it does not square with what seems ann acceptable standard of justice today; nor with the letter or spirit of the teachings of Jesus Christ. I cannot find any support or such a doctrine of inequality in His recorded sayings. I am deeply troubled. Having decided through earnest study that one of the chief causes of war is the existence of ethnocentrism among the peoples of the worlds that war is our major social evil which threatens to send all of us to destructions and that we can ameliorate these feelings of ethnocentrism by promoting understanding of one people by others, I am now confronted with this doctrine of my own church which says in effect that white supremacy is part of God’s plan for His children; that the Negro has been assigned by Him to be a hewer of wood and drawer of water for his white-skinned brethren. This makes us nominal allies of the Rankins and the Bilbos of Mississippi, a quite unhappy alliance for me, I assure you.

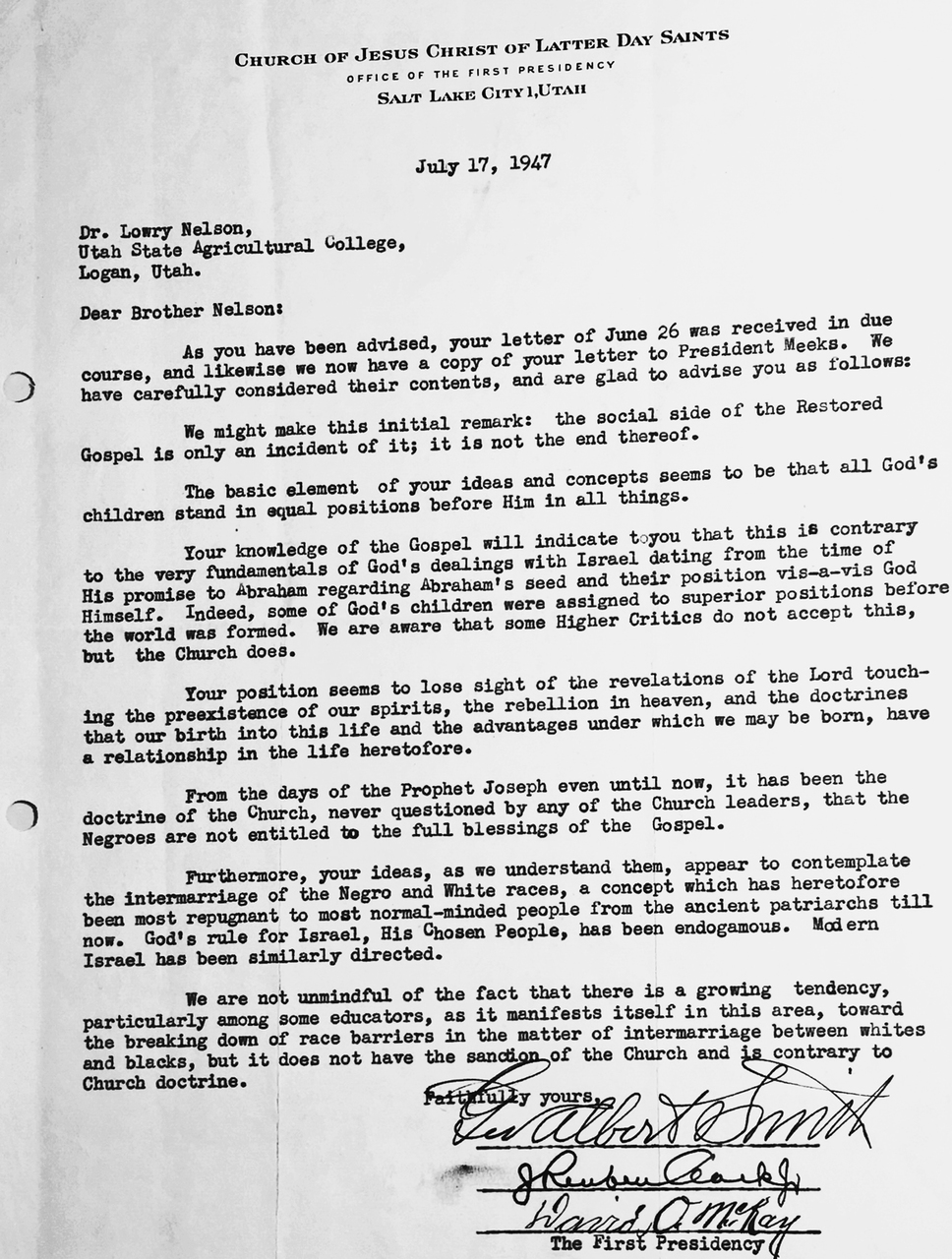

Nelson challenged the idea of white supremacy—and Mormon supremacy as well—not only from scholarship but also on the basis of his admiration for people of color with whom he had interacted in the professional realm, including “Dr. George Washington Carver, the late eminent and saintly Negro scientists,” who under the emerging doctrine would be “inferior even to the least admirable white person, not because of the virtues he may or may not possesss, but because—through no fault of his own—there is a dark pigment in his skin.” He responded sharply as well to the leadership’s instruction that the “social side” of the Gospel was not a primary concern. “Are the virtues of honesty, chastity, humility, forgiveness, tolerance, love, kindness, justice, scondary? If so, what is primary? Love of God? Very well. But the second (law) is like unto it.” He concluded in a conciliatory and deferential tone, admitting that in his concerns he was but one of many faithful members Church leaders were tasked to lead, guide, and counsel. He humbly stated that in laying out his thinking so fully in writing he was “trying to be honest with myself and others” and “trying to find my way in what is a very confused world,” citing his recent time in Europe, where he witnessed the devastations of World War II, as his motive. He pleaded for “love,” “mutual respect,” and “understanding” instead of a “legalistic” approach to morality. The First Presidency’s final reply on November 12, 1947 (see figure 5.2), yielded nothing:

We feel very sure that you understand well the doctrines of the Church. They are either true or not true. Our testimony is that they are true. Under these circumstances we may not permit ourselves to be too much impressed by the reasonings of men however well-founded they may seem to be. We should like to say this to you in all kindness and in all sincerity that you are too fine a man to permit yourself to be led off from the principles of the Gospel by worldly-learning. You have too much of a potentiality for doing good and we therefore prayerfully hope that you can reorient your thinking and bring it in line with the revealed word of God.

Figure 5.2. LDS Church President George Albert Smith to Lowry Nelson, November 12, 1947.

Image courtesy Marriott Special Collections Library, University of Utah.

The surviving correspondence ends there. When the Church issued its statement on the priesthood ban in August 1949, removing any question as to whether it was official policy, Nelson found himself “troubled” and uncertain of how to proceed. But copies of his letters made their way into private circulation and were passed from hand to hand by Mormon religious educators and university-based and grassroots intellectuals, from Cedar City, Utah, to Berkeley, California. “[We] sat on the floor by my desk until 1:30 a.m. while [we] read the letters between Lowry and the Brethren,” Gustav Larsen recalled. “We were entertained, amused, delighted and disappointed alternately.”11 The great Mormon historians Juanita Brooks and Leonard Arrington wrote Nelson to ask for copies for their files, as did a young assistant professor of political science at Brigham Young University, who informed Nelson that his letters were in circulation among the faculty and assured him that “your point of view, in which many of us concur fundamentally, has been fairly well disseminated among some of the thinking people here.” Copies were even held and catalogued among the Brigham Young University Library Collections.12

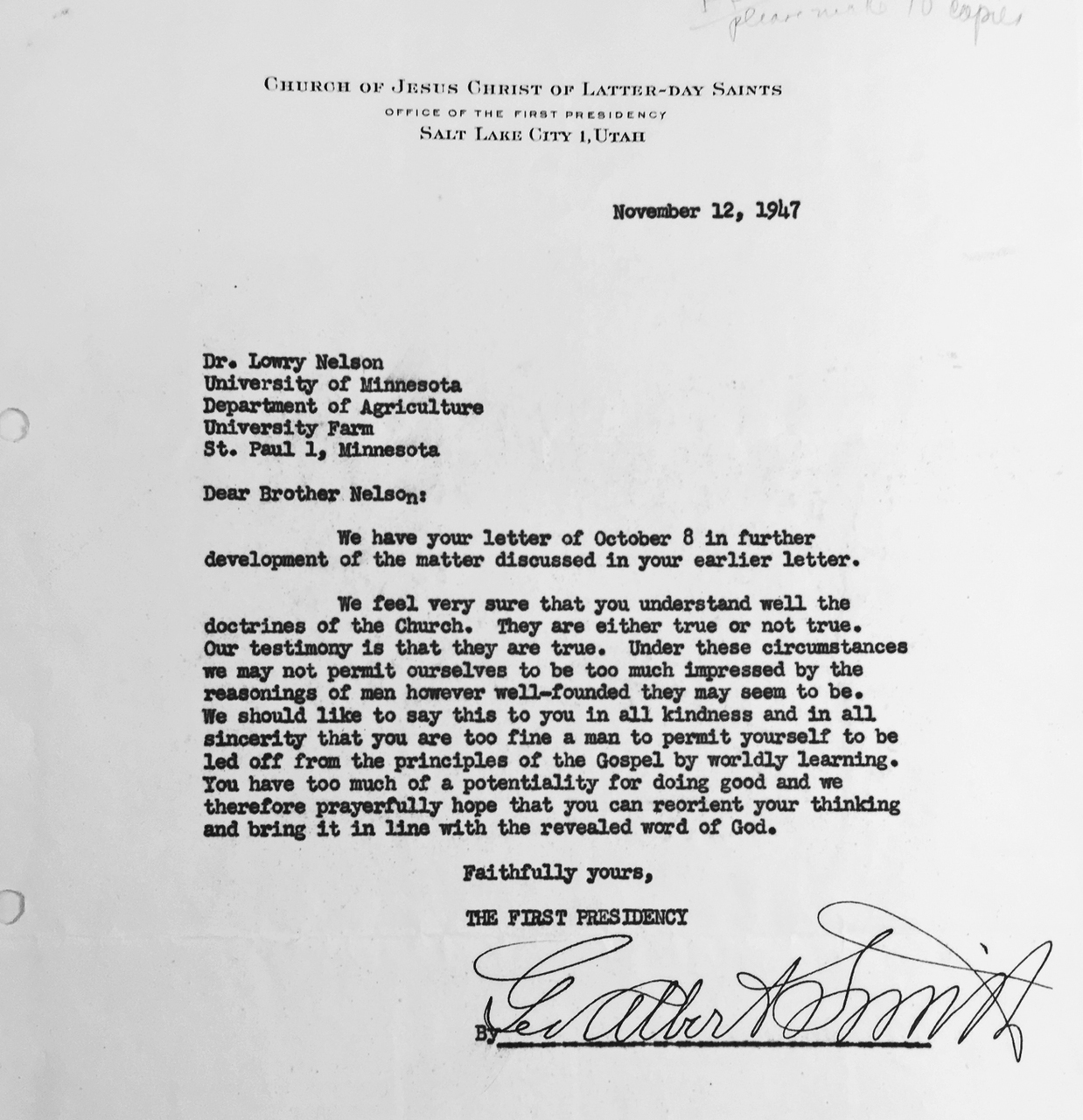

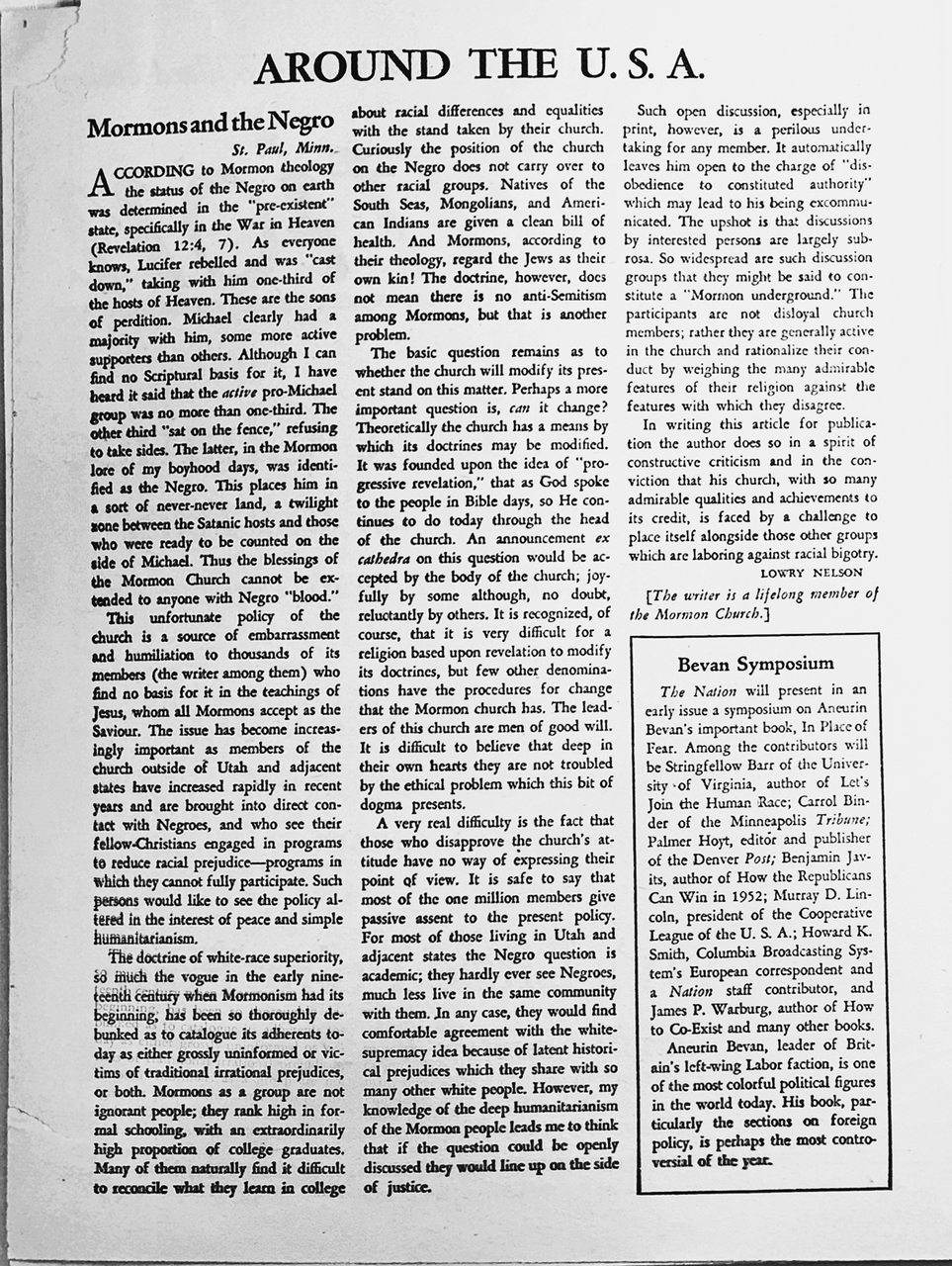

Nelson stopped corresponding with Church headquarters for a few years, until he received a November 7, 1951, news clipping from the Church-owned Deseret News about missionaries in South Africa who conducted an aggressive and invasive genealogical screening of a local woman on her deathbed to ascertain whether or not she could be eligible for posthumous temple rites. Nelson later recalled that their efforts “disturbed me all over again,” and he resolved to bring greater scrutiny to the priesthood and temple ban.13 He developed his own report on the Church’s anti-Black segregation for publication in The Nation, going so far as to send Church leaders the article in advance to make them aware, writing that although he held “the Brethren” in “affectionate regard,” anti-Black racism was a “matter of principle which I cannot compromise. . . . I am compelled to publicly issociate myself from adherence to a doctrine which is so incongruous with the Gospel as I had been taught it.”14 He received from the First Presidency’s secretary a curt reply that “when a member of the Church sets himself up against doctrines preached by the Prophet Joseph Smith and by those who have succeeded him in the high office which he held, he is moving into a very dangerous position for himself personally.” Beyond its aggressive misrepresentation of LDS history, the secretary’s letter suggested a direct threat to Nelson’s membership. Nelson’s article (see figure 5.3) appeared in The Nation on May 24, 1952:

ACCORDING to Mormon theology the status of the Negro on earth was determined in the “pre-existent” state, specifically in the War in Heaven (Revelation 12:4, 7). As everyone knows, Lucifer rebelled and was “cast down,” taking with him one-third of the hosts of Heaven. These are “the sons of perdition.” Michael clearly had a majority with him, some more active supporters than others. Although I can find no Scriptural basis for it, I have heard it said that the active pro-Michael group was no more than one-third. The other third “sat on the fence” refusing to take sides. The latter, in the Mormon lore of my boyhood days, was identified as the Negro. This places him in a sort of never-never land, a twilight zone between the Satanic hosts and those who were ready to be counted on the side of Michael. Thus the blessings of the Mormon Church cannot be extended to anyone with Negro “blood.” This unfortunate policy of the church is a source of embarrassment and humiliation to thousands of its members (the writer among them) who find no basis for it in the teachings of Jesus, whom all Mormons accept as the Saviour. The issue has become increasingly important as members of the church outside of Utah and adjacent states have increased rapidly in recent years and are brought into direct contact with Negroes, and who see their fellow Christians engaged in programs to reduce racial prejudice and programs in which they cannot fully participate. Such persons would like to see the policy altered in the interest of peace and simple humanitarianism.

The doctrine of white-race superiority, so much the vogue in the early nineteenth century when Mormonism had its beginning, has been so thoroughly debunked as to catalogue its adherents today as either grossly uninformed or victims of traditional irrational prejudices, or both. Mormons as a group are not ignorant people; they rank high in formal schooling, with an extraordinarily high proportion of college graduates. Many of them naturally find it difficult to reconcile what they learn in college about racial differences and equalities with the stand taken by their church. Curiously the position of the church on the Negro does not carry over to other racial groups. Natives of the South Seas, Mongolians, and American Indians are given a clean bill of health. And Mormons, according to their theology, regard the Jews as their own kin! The doctrine, however, does not mean there is no anti-Semitism among Mormons, but that is another problem.

The basic question remains as to whether the church will modify its present stand on this matter. Perhaps a more important question is, can it change? Theoretically the church has a means by which its doctrines may be modified. It was founded upon the idea of “progressive revelation,” that as God spoke to the people in Bible days, so He continues to do today through the head of the church. An announcement ex cathedra on this question would be accepted by the body of the church; joyfully by some although, no doubt, reluctantly by others. It is recognized, of course, that it is very difficult for a religion based upon revelation to modify its doctrines, but few other denominations have the procedures for change that the Mormon church has. The leaders of this church are men of good will. It is difficult to believe that deep in their own hearts they are not troubled by the ethical problem which this bit of dogma presents.

A very real difficulty is the fact that those who disapprove the church’s attitude have no way of expressing their point of view. It is safe to say that most of the one million members give passive assent to the present policy. For most of those living in Utah and adjacent states the Negro question is academic; they hardly ever see Negroes, much less live in the same community with them. In any case, they would find comfortable agreement with the white supremacy idea because of latent historical prejudices which they share with so many other white people. However, my knowledge of the deep humanitarianism of the Mormon people leads me to think that if the question could be openly discussed they would line up on the side of justice.

Such open discussion, especially in print, however, is a perilous undertaking for any member. It automatically leaves him open to the charge of “disobedience to constituted authority” which may lead to his being excommunicated. The upshot is that discussions by interested persons are largely subrosa. So widespread are such discussion groups that they might be said to constitute a “Mormon underground.” The participants are not disloyal church members; rather they are generally active in the church and rationalize their conduct by weighing the many admirable features of their religion against the features with which they disagree. In writing this article for publication the author does so in a spirit of constructive criticism and in the conviction that his church, with so many admirable qualities and achievements to its credit, is faced by a challenge to place itself alongside those other groups which are laboring against racial bigotry.

Figure 5.3. Lowry Nelson, “Mormonism and the Negro,” The Nation, May 24, 1952, 2.

The statement is as fine a model of reasoned but faithful LDS dissent and as lucid a depiction of the theological, social, and political conditions of dissent as exists in Mormonism’s 180-year history. It also inspired similar attempts to pressure Church leadership from other well-placed LDS scholars including University of Chicago geographer Dr. Chauncy Harris, who maintained a twenty-year correspondence with Nelson, as the two men—and many other like-minded LDS people nationwide—developed private archives of clippings and other documents relating to the issue and attempted to hammer out a strategy for effecting change.15 In the 1960s and 1970s, Nelson was sought out by scholars like Armand Mauss, Kendall White, and Lester Bush (who would go on to author an essential article on the Black priesthood and temple ban), and John W. Fitzgerald, a Salt Lake–area LDS seminary teacher and high school principal, who had organized with other white LDS people (including Grant Ivins, Sterling McMurrin, and Brigham Madsen) to expose the doctrinal irregularity and insufficiency of the priesthood and temple ban by speaking at civic and non-LDS church events and publishing letters to the editor in the Salt Lake Tribune. For making his arguments public, Fitzgerald was excommunicated in late 1972.16 And yet Lowry Nelson was not excommunicated. It may be that by presenting his case and the threat of excommunication in writing, so clearly, so publicly, in a national venue published outside the Mormon corridor and beyond its domain of territorial knowledge, he gained a kind of immunity from repression, inasmuch as the Church remained invested in not fulfilling its detractors’ worst charges of authoritarianism. But his privileged racial and social position also played a role. He again took on the Church’s anti-Black segregationism in a 1974 article in the Christian Century and, according to one biographer, “needled Church leaders with satirical poems until his death”: “The gadfly lived a charmed life as a persistent dissident, possibly because of his age, his eminence, and the fact that he’d known many of the Brethren personally for years.”17 As a Utah-born, white, multigenerational Mormon man with deep connections to the hierarchy, whose writings seemed for the most part limited to academic and liberal audiences, he retained his place at the edge of the herd.

* * *

Over the next decade, the “subrosa” “Mormon underground” of liberal, heterodox, and dissenting LDS people matured enough to develop its own social and print institutions. Most important among them was Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, founded in 1966 by a cohort of Stanford University graduate students. The journal’s mission was (and continues to be) to “bring [the Mormon] faith into dialogue with the larger stream of world religious thought and with human experience as a whole and to foster artistic and scholarly achievement based on their cultural heritage.” Dialogue sought to create a space where Mormons at the edge of the herd could develop shared knowledge, perspective, hopes, and ideas.

From its beginnings, Dialogue was one of the most influential forums for exchange of information and opinion on the Church’s priesthood and temple ban, as well as on issues of racial and gender equality in Mormonism more generally. Even as the institutional LDS Church from its 1949 statement onward held the counterfactual position that the ban originated with God himself as revealed to the Church’s founders, Dialogue supported historical scholarship that restored to modern Mormon memory a far more nuanced and complicated historical picture and in so doing challenged the silent compact between the Church and its members not to betray racial innocence or foster critique.

Dialogue’s founders represented a sensibility among some white multigenerational Mormon families that it was possible to leverage their relationships and the safety of an unassailable Mormon identity to respectfully challenge authority when warranted. This view was also subscribed to by political families like the Udalls of Arizona, who had made and would continue to make stands on critical issues, even when they placed them on the margins of mainstream Mormonism. Born in 1920 in St. John’s, Arizona, Stewart Udall descended from a long line of dissident Mormons. He attended the University of Arizona until service in World War II interrupted his studies; while in the armed forces, Udall joined the NAACP. Upon his return, in 1947, Udall reflected critically on how his wartime experiences impacted his faith: “I find it difficult to be in full fellowship within the Mormon Church,” he admitted, citing the fact that “too many members find it easy to be simultaneously devout Mormons and devout anti-Semites, lovers of their fellow men in public and Negrophobes in private.”18 As returning students at the University of Arizona, Stewart and his brother Mo helped desegregate the school cafeteria by escorting Black students who had been restricted to outside dining tables inside and using their stature—social and physical—to resist administration efforts to move them.

After receiving his law degree, Udall entered public service. He cofounded the Tucson League for Civil Unity, an anti-segregationist and anti-discrimination group, and helped implement the desegregation of Arizona schools as a member of the Tucson School Board. Elected to Congress in 1954, Udall was appointed secretary of the interior by President Kennedy in 1960. Among his first acts was to order in March 1961 a survey of Department of Interior properties to screen for racial discrimination in hiring. Legal staff at the department had advised him that the Washington Redskins, the only fully segregated team in the National Football League, had just signed a lease to build a statement on federal property: Anacostia Flats, part of the National Capital Parks. Udall ordered them to desegregate by October. For this, he was both celebrated and challenged by observers who noted that the secretary of the interior himself belonged to an officially segregated Church.

Although he was considered and, in all likelihood, considered himself a “Jack Mormon”—that is, a nonobservant, nonorthodox Mormon whose ties to the faith are more historical, cultural, and affectional than devotional—Udall took personal responsibility for the priesthood and temple ban. He relayed to LDS Church leadership the embarrassment and conflict the Church’s stance created for its progressive members. He also corresponded with his brother, now congressman Mo Udall, to express consternation over egregiously racist public remarks made by LDS Church leaders, including octogenarian LDS Church President Joseph Fielding Smith. Moreover, he developed a personal archive of writings by scholars and rank-and-file Church members that challenged the consensus view of the ban as divinely inspired. After sharing his concerns with Church leaders in writing, he published an open letter to LDS Church President David O. McKay in Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought on May 16, 1967. It follows in its entirety:

For more than a decade we Americans have been caught up in a revolution in thinking about race and human relationships. The Supreme Court has wisely and effectively related the Constitution to the facts of life in the twentieth century; three Presidents and five Congresses have laid new foundations for a society of equal opportunity; most of the churches, with unaccustomed and admirable militance, have enlisted foursquare in the fight for equal rights and higher human dignity.

The whole future of the human race is now keyed to equality—to the ideal of equal opportunity and of equal civil rights and responsibilities, and to the new dignity and freedom which these would bring. The brotherhood of all men is a moral imperative that no religion and no church can evade or ignore. Enlightened men everywhere see now, as their greatest prophets and moral teachers saw long ago, that brotherhood is universal and indivisible.

It was inevitable that national attention would be focused on what critics have called the “anti-Negro doctrine” of the L.D.S. Church. As the Church becomes increasingly an object of national interest, this attention is certain to intensify, for the divine curse concept which is so commonly held among our people runs counter to the great stream of modern religious and social thought.

We Mormons cannot escape persistent, painful inquiries into the sources and grounds of this belief. Nor can we exculpate ourselves and our Church from justified condemnation by the rationalization that we support the Constitution, believe that all men are brothers, and favor equal rights for all citizens.

This issue must be resolved—and resolved not by pious moralistic platitudes but by clear and explicit pronouncements and decisions that come to grips with the imperious truths of the contemporary world. It must be resolved not because we desire to conform, or because we want to atone for an affront to a whole race. It must be resolved because we are wrong and it is past the time when we should have seen the right. A failure to act here is sure to demean our faith, damage the minds and morals of our youth, and undermine the integrity of our Christian ethic.

In her book, Killers of the Dream, the late Lillian Smith—whose life was exposed to all the warping forces of a racist culture—wrote these words:

“I began to understand slowly at first, but more clearly as the years passed, that the warped, distorted frame we have put around every Negro child from birth is around every white child also. Each is on a different side of the frame but each is pinioned there. And I knew that what cruelly shapes and cripples the personality of one is as cruelly shaping and crippling the personality of the other.”

What a sad irony it is that a once outcast people, tempered for nearly a century in the fires of persecution, are one of the last to remove a burden from the most persecuted people ever to live on this continent. The irony is deepened by the circumstance of history that the present practice of the Church in denying full fellowship to the Negro grew out of troubles rooted in earlier pro-Negro policies and actions. It is well known that Joseph Smith held high ideals of universal brotherhood and had strong pro-Negro leanings that were, in a true sense, prophetic. And it is well known that in the beginning the Church accepted Negroes into full fellowship until this practice offended its anti-Negro neighbors. It then settled for a compromise with its own ideals based on a borrowed superstition that the Negroes are under a divine curse. This anomaly is underscored by the fact that the Church has always enjoyed excellent relations and complete fellowship with all other races. (How different have been our associations with the American Indians, the Spanish-speaking peoples, the Japanese and Polynesians!) What transformations might take place in our spiritual and moral energies if we were to become, once again, moral leaders in improving the lot of the Negroes as we have striven to do with the natives of the South Seas?

At an earlier impasse, the Church, unable to escape history, wisely abandoned the deeply imbedded practice of plural marriage and thereby resolved a crisis of its own conscience and courageously faced the moral judgment of the American people. In 1890 for most Church leaders polygamy was a precious principle—a practice that lay at the very heart of Mormonism. Its proscription took genuine courage, but our leaders were equal to the task. By comparison, the restriction now imposed on Negro fellowship is a social and institutional practice having no real sanction in essential Mormon thought. It is clearly contradictory to our most cherished spiritual and moral ideals.

Every Mormon knows that his Church teaches that the day will come when the Negro will be given full fellowship. Surely that day has come. All around us the Negro is proving his worth when accepted into the society of free men. All around us are the signs that he needs and must have a genuine brotherhood with Mormons, Catholics, Methodists, and Jews. Surely God is speaking to us now, telling us that the time is here.

“The glory of God is intelligence” has long been a profound Mormon teaching. We must give it new meaning now, for the glory of intelligence is that the wise men and women of each generation dream new dreams and rise to forge broader bonds of human brotherhood to what more noble accomplishment could we of this generation aspire?

Stewart L. Udall, Washington, D.C.19

Understanding exquisitely well the politics of Mormon culture and its sensitivity to public exposure derived from its nineteenth-century past and its not-too-distant twentieth-century quest for respectability, Udall carefully chose not to directly address Church leadership, which might have been seen as too direct a challenge, nor did he address a broad secular public in an effort to embarrass and expose Church leaders. He wrote, first, to his fellow Latter-day Saints, in an LDS-produced and moderated venue, understanding full well that his national stature would in time bring wider publicity and a broadened audience to witness and support the internal moral deliberations of the Mormon people. And it did. Udall received hundreds of letters and telegrams in response, spanning a range of Mormon opinion, with support coming especially from LDS liberal stalwarts like Esther Peterson, a women’s and labor rights activist who also held prominent posts in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, and Lowry Nelson, who wrote, “I’m proud of you! . . . Would that a little of your courage could get piped into the aenemic [Church] headquarters.” Spencer W. Kimball, another rural Arizona Mormon who had ascended into the Church’s highest-ranking leadership body, the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, responded differently. Taking what one historian characterizes as “the tone of an upset and disappointed father,” he wrote, “Stewart, I cannot believe it! You wouldn’t presume to command your God nor to make a demand of a Prophet of God!” and characterized the letter as a “sincere but ill-advised effort in behalf of the welfare of a minority.”20 Ironically, Kimball’s son Spencer L. Kimball, a professor of law at the University of Michigan, had collected his own file of materials on the race issue, including copies of Lowry Nelson’s exchange with Church officials, and had stepped away from Church activity over matters of conscience, racism certainly among them.21

Another well-placed Arizona-rooted Mormon offered a public rejoinder to Udall in the New York Times’s front-page coverage of the letter on May 19, 1967. Udall had sent Romney a handwritten note on May 16 to let him know the piece would shortly appear: “[This] has long been an issue that has troubled my conscience. The brethren must, I am convinced, face it squarely (as the plural marriage issue was faced) sooner or later.” Reporter Wallace Turner solicited a quote from Governor George Romney, who despite his own record of vocal and active support for civil rights in the secular sphere did not approve of Udall’s efforts: “In light of the fact that church doctrine is not determined by the attitude and expression of the individual members or the leadership, he knows, as do all other informed members of my faith, that his method of accomplishing the religious object he seeks cannot serve any useful religious purpose.”22 Udall’s statement and Romney’s reply received nationwide newspaper coverage, including front-page coverage in the New York Times, with some observers noting that Romney, who was then seeking the Republican Party presidential nomination, had “ducked” the issue to maintain his campaign-trail message that he could not be held responsible for the doctrines of his Church but should instead be measured on racial issues by his conduct as governor.23

Both George Romney and Stewart Udall had deep and elite ancestral roots in Mormonism, common ties in the rural Mormon communities of northern Arizona, and national political reputations.24 Their respective approaches reflect a significant difference in the two men’s theories of change in the Mormon movement. Romney subscribed to the silent agreement that he would not openly express opposition to the Church’s anti-Black segregation and sustain not only its leadership but also its assertion of innocence. Implicit in this is a theory of change in Mormonism that God will work through the hierarchy of the Church through continuing revelation to Church leaders and that while a well-placed private comment might assist that process, public dissent can only derail it. There is some truth in this viewpoint: as a sharply differentiated religious minority that maintains a strong boundary against “the world,” orthodox Mormonism is highly allergic to external scrutiny and pressure, even more so in light of historic persecutions and common mockeries of LDS people. Pressure from the outside may in fact engender retrenchment. But as he weighed the costs and affordances of orthodoxy, Udall found himself in secure enough a position—with footing and public regard in the secular world, and a deeply rooted Mormon identity and sense of belonging not revocable through Church discipline—to step outside the silent agreement and go public. He did so carefully, directing his comments first to other LDS people, not to the public nor directly to Church leadership, which might have been interpreted by the leaders and by more orthodox LDS people as a violent challenge. Implicit in his choices is a recognition that even Church leaders must be held publicly accountable. Until the death of Jane Manning James in 1908, Church leaders had been held accountable by the living presence of Black pioneers who knew the Church’s true history on race and stood as living emblems of it, even as that history was erased in institutionally produced, “correlated,” orthodox, official histories and curricula. Udall willingly stepped into that role to bear witness and hold Church leaders accountable. Udall’s approach also reflects a theory of change that vests hope in the possibility of continuing revelation not only to Church leaders but also to the Mormon people themselves as they apply the tools the faith provides every member—individual prayer, scripture study, contemplation, and personal revelation through the Holy Ghost—to seek truth. Udall’s theory of change vested hope in Mormon people as agents of change both within and without the Church. Importantly, it was founded in an understanding that those who lost the most by anti-Black segregation in the LDS Church were not excluded Black people but white Church members themselves who were morally hobbled by their complicity and duplicity. Udall seemed to understand fully the silent agreement to “overlook” Mormon white supremacy sustained by well-placed Mormons like Romney and by the nation’s majority itself and how corrosive it was to Mormons ourselves. And he also seemed to understand that without making statements in writing, in public, on the record, articulations of conscience and differences like his would be lost to history—lost to future generations of LDS people who might need role models and exemplars of principled, faithful Mormon dissent. Maintaining racial innocence depended then and depends now on asserting that Mormons had never thought or felt otherwise, that things had been as God intended them, that there had never been struggle, and that struggle was inimical to the Spirit of God. To go along with the silent agreement not to challenge Church leaders on their racism was to surrender even further Mormonism’s founding impulses of truth seeking and radical differentiation in the service of twentieth-century white hierarchical institutional security.

* * *

Udall raised a public voice of dissent from a place of privileged security. He knew that as an esteemed public official he would remain secure in his employment. He was not on the Church payroll, and while his Mormon connections were important to his political success, as a federal appointee, he had placed himself beyond whatever ire his stance might draw from LDS voters in his home state of Arizona. Moreover, he knew that as a member of a storied multigenerational Mormon family he would never lose his belonging, community, or identity: he would only by virtue of dissent lose opportunities to serve in a high-ranking position in the Church and the approval of some of its more orthodox leaders and members. As an elite white Mormon man, he had only the discomfort of pushback from other elite white Mormon men to worry about, and in taking his dissent so public, Udall ensured that any pushback would be subject to what elite white Mormon men disliked most—full scrutiny and potential judgment and shame from an American national audience.

But what about the rank-and-file white members who found themselves just as agitated over the Church’s anti-Black racism? How did they negotiate the silent agreement? What theories of change did they hold, and how did they put them into action? Lowry Nelson’s 1952 piece in The Nation spoke of an extensive Mormon “underground” of conscientiously dissenting and heterodox “discussion groups,” and by Udall’s time that underground had formed its own above-ground print institutions where even geographically far-flung, out-migrated Mormons who may not have had access to critical masses of dissenters in Mormon population centers like Salt Lake could make contact and participate, at least by reading, writing, and thinking. In 1973, the independent historian Lester Bush published in Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought “Mormonism’s Negro Doctrine: A Historical Overview,” a deeply footnoted fifty-seven-page essay composed from archival LDS historical sources tracking the history of the anti-Black priesthood and temple ban. Bush hoped that historicizing the policy—showing it to have been instituted unevenly by human actors with human motivations with shifting rationale—would dislodge the idea that it reflected the will of God from time immemorial as revealed to infallible LDS prophets, the majority view at the time in Mormonism, and have some influence on Church leaders.

Scholarship like that by Lester Bush can play a critical role in helping to shift perspectives. So can taking direct action to disrupt the workings of segregation, and it is the most likely option available to those who were not, as Udall or Bush were, positioned by education and elite access to be able to use writing alone to command attention. But except for working-class Mormons who had taken part in the vibrant and sometimes violent labor struggles of Utah’s mining industry in the 1920s and 1930s and those who had participated in demonstrations and strikes after out-migrating (like Esther Peterson), few Mormon people had exposure to or experience in direct action. It was not part of the Mormon political lexicon. The homogeneity and isolation of Intermountain West Mormon communities and the fact that their major struggles were territorial meant that LDS people were more practiced in armed conflict (against the federal government and against indigenous peoples), vigilantism, undergrounding (especially in relation to polygamy), migration (most recently by Mormon polygamous and fundamentalist communities), and the various theatrics of American electoral politics (complicated of course by LDS institutional influence) than in the kinds of mass mobilization associated with popular movements in the nineteenth century and demonstrative civil disobedience theorized by Thoreau and implemented on a mass scale by Mahatma Gandhi that had defined American public protest from the 1950s onward. In the early 1960s, the NAACP had planned or carried out pickets to protest the LDS Church’s perceived interference with the passage of civil rights legislation in Utah. By the late 1960s, Black athletes on teams scheduled to play Brigham Young University and their supporters had used nonviolent direct action and civil disobedience to protest the Church’s anti-Black segregation, and at times the demonstration crossed over into violence, as when Colorado State fans threw a Molotov cocktail into the basketball arena during a Brigham Young University–Colorado State University contest in Fort Collins in 1970.25

But white LDS people who attempted direct action to challenge anti-Black segregation within the Church were very few. An LDS Church member named Douglas Wallace had in April 1976 baptized and ordained a Black man to the priesthood; he was subsequently excommunicated.26 Wallace continued his pressure by attempting to disrupt General Conference and announcing to the press that he would put LDS Church President Spencer W. Kimball “on trial.” Another who took direct action was Byron Marchant. Marchant was one of fifteen children in a multigenerational but nonelite and working-class Salt Lake City Mormon family. His mother, Beatrice Peterson Marchant, came from rural, working-class Utah LDS Democrat stock; worked as a schoolteacher for several years in rural Utah communities; moved to Salt Lake City and raised her children while caring for a disabled husband; and in 1968 was elected to the Utah state legislature, where she fought for the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment.27 She was remembered by her grandchildren and greatgrandchildren as a champion of the “underdog,” and her personal writings reveal her essentially activist disposition: “I can appreciate and understand the world and the people around me if only I make an effort to do so. I even have the ability to help change the world for better or for worse.”28 Byron had served a proselytizing mission for the Church in France, attended Brigham Young University, married Gladys Smith, and settled in a working-class neighborhood in Salt Lake City, where he taught youth tennis in a local park, took a job as a church meetinghouse janitor, and was appointed by his local congregation to serve as the Scout troop leader. Byron welcomed local non-Mormon African American youth into the troop but was deeply upset when in 1973 local leaders told him that the African American boys were not permitted to assume leadership roles in the troop due to the Church’s priesthood-temple ban, and more so when he discovered that the white Mormon Boy Scouts in his troop used the ban to taunt their Black fellow troop members at school. Marchant recalls that the race-based taunting even escalated into a rock fight at one troop campout. It was, to his mind, unacceptable. He worked with the NAACP to bring national attention and pressure to the issue. His actions permanently “split” the family, a nephew later recalled.29

Marchant was also a student of Mormon history, and his commitment on the race issue propelled him to research the origins of the Church’s ban for himself. With a cluster of Mormon scholars starting to write and publish more openly in venues like Dialogue about inconsistencies in the Church’s account of its own history on race—the Church had released a statement in 1969 claiming that “Joseph Smith and all succeeding presidents of the Church have taught that Negroes, while spirit children of a common Father, and the progeny of our earthly parents Adam and Eve, were not yet to receive the priesthood, for reasons which we believe are known to God, but which He has not made fully known to man”—Marchant visited the Church Archives on North Temple Street to see for himself the ordination certificate of Elijah Abel, an African American man ordained to the priesthood and the Quorum of the Seventy during the founding decades of the Church. He recalls: “I made a written copy of it (with permission of the archivist there) and proceeded to make a typewritten copy of it at my home from my handwritten copy. The original (public domain) document showed that Joseph Smith, Jr., had signed it.” Marchant distributed photocopies of the typewritten facsimile to “the press and public” in August 1977.30

As he radicalized around the Church’s racism, Marchant and a small cohort adopted direct action tactics, including a weekly picket outside the LDS Church Office Building in downtown Salt Lake City. In October 1977, Marchant took the bold step of introducing direct action and nonviolent resistance tactics into LDS sacred spaces. Twice annually, the Church convened a General Conference in the Mormon Tabernacle on Temple Square. With the entire leadership hierarchy (and the Mormon Tabernacle Choir) seated on the stand, the historic building packed to the rafters with thousands of faithful adherents, and hundreds of thousands more watching on television and listening on radio, General Conference was the most important “rite of assent” (to use Sacvan Bercovitch’s term) in Mormon life. Every Conference, a member of the hierarchy asked members attending in person or participating by media to signal with an upraised hand that they “sustained” the leaders of the Church as “prophets, seers, and revelators,” an act understood by many orthodox Mormons as a promise not to dissent and as a fulfilling of sacred covenants they had made in LDS temple rites to consecrate themselves entirely to the Church. His nephew Mark Barnes was watching the October 2, 1977, Conference session on local television in Salt Lake City, and recalls:

As we watched the start of the Saturday afternoon session on October 2, 1977, a familiar voice boomed from the television set. I immediately knew it was Byron. “President Tanner did you note my vote?” First Counselor N. Eldon Tanner looked confused, as he searched for the source of the dissenting vote. Security responded escorting Byron from the building. Byron later explained to the press that his negative vote was meant to highlight the injustice of the priesthood ban.31

Byron Marchant had stood in the packed Tabernacle balcony and raised his hand to signal that he did not sustain Church leaders because of their anti-Black discrimination. Moreover, he had called out across the crowded Tabernacle to ensure that his presence registered not only there but also with the hundreds of thousands listening and watching on television, even if the LDS Church camera operators refused to turn their cameras from the pulpit to capture his dissenting image. He was excommunicated twelve days later, on October 14, and subsequently lost his job as a meetinghouse janitor. Marchant was by then a widower. Dissension within the family over his activism and excommunication contributed at least in part to a custody battle that eventuated in the placement of his children with his deceased wife’s mother.32

Marchant challenged the silent agreement between the Church and its members to maintain its innocence of anti-Black racism, but he had done so from a far more precarious economic and social class position than Udall and through direct action tactics that were arguably more disruptive than Udall’s letter. And the costs of revoking his membership would not have been nearly as great to the Church as the potential costs of moving in on someone with Stewart Udall’s publicity, esteem, and national stature. As a working-class, nonelite Mormon, Marchant was more expendable, and violating the silent agreement through direct action cost him deeply. He lost access to family, employment, and the social networks that held Mormon life in Salt Lake City together. His story demonstrates the critical role social and class privilege has played and continues to play in Mormon dissent.

* * *

It was even more precarious for members of color who openly opposed the Church’s priesthood and temple ban. Elder Boyd K. Packer, a member of the Church’s Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, had instructed the Church-sponsored Genesis group—a fellowship auxiliary founded in 1971 serving between twenty and two hundred Black members in the Salt Lake area—to “keep a low profile.”33 Most Genesis members worked through private channels, expressing their desire for priesthood and temple access and sharing their experiences of racism in letters and private face-to-face meetings with Church leaders. Others who became frustrated by the Church’s intransigence dropped out of Church activity. In 1976, after Wallace’s rogue priesthood ordination of a Black man, some members of the Genesis group did sign a petition calling on the Church to commit to a timeline for ending the ban, a move that exacerbated tensions within the group and led members on both sides of the issue to withdraw.34

What would have happened had the leadership of the Genesis group been directly and openly critical of LDS Church racism or taken their disagreements public, breaking the “silent agreement” between the Church and its members to preserve the racial innocence of Mormonism? How did the dynamics of racial and class privilege impact the practice of anti-racist dissent in LDS communities? The experience of George P. Lee suggests that like class privilege, racial privilege determined the extent to which one could conscientiously object and question LDS Church racism without experiencing personal harm. Born in 1943 to the Bitter Water Clan for the Under the Flat-Roofed House People Clan on the Ute Mountain Indian Reservation, George P. Lee (Ashkii Hoyani) grew up near Shiprock, New Mexico, and attended Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding schools. Due to the influence of a local Mormon trading post owner, he was among the first indigenous children to participate in the Church’s “Indian Placement Program,” founded by Elder Spencer W. Kimball. Kimball had fostered and championed a number of initiatives designed to serve indigenous Mormons on the principle that they were the direct descendants of the “Lamanite” peoples in the Book of Mormon, that the Book of Mormon was their heritage and legacy as a “lost tribe” of the “House of Israel,” and that their latter-day “blossoming” had been prophesied. In addition to placement, these programs included congregations and conferences for so-called modern Lamanites, and numerous programs to recruit and support American Indian students at Brigham Young University. “In the 1970s,” writes John-Charles Duffy, “BYU boasted that it spent more, per student, on American Indian education than on any other undergraduate program and spent more on Indian scholarships than all other colleges and universities in the United States combined; this commitment was explained as an expression of the Church’s mission to the descendants of Book of Mormon peoples.”35 Lee participated in a number of these programs, served an LDS mission to indigenous communities in the Southwest, attended Brigham Young University, and married. After attaining a doctoral degree in education, he served as president of the Southwest Indian Mission, the first of several high-profile appointments in Church leadership. He also worked as a teacher, principal, and community college president in reservation schools. In October 1975, he became the first Native American called to serve in the First Quorum of the Seventy; Spencer W. Kimball, who had become the president of the LDS Church, appointed him. Kimball, in addition to sponsoring programmatic supports for indigenous participation in the Church, had also directed that Book of Mormon passages connecting moral decline among the Lamanites with dark skin and redemption with whiteness be revised in 1981. His actions created a climate that fostered confidence in George P. Lee, who wrote and published his autobiography Silent Courage in 1987.

During his tenure, Lee developed a Book of Mormon–based theological view that so-called Lamanites and other peoples literally descended from the Biblical House of Israel were the true heirs of the Gospel and bore primary responsibility for the building of the Kingdom of God on earth. White Europeans and their descendants could be “adopted” into the “House of Israel’s” “tribe of Ephraigm” through baptism but could never be “blood” lineage descendants. From his new position among the leadership, Lee also observed that attention and opportunities for leadership were directed primarily toward other elite white Mormons, not toward the poor or people of color. The death of President Kimball in 1985 and the subsequent institutional transition to the leadership of Ezra Taft Benson proved difficult for Lee. Under Benson’s leadership, the Church scaled back its programming for and focus on so-called Lamanites, bringing Lee into conflict with leaders including Apostle Boyd K. Packer, who was notorious for his irascibility and intransigence. In fall 1987, Lee penned a long letter to Benson and other Church leaders expressing his frustration. The letter opened in the tone of humility and deference toward Church leaders expected of LDS people. “I speak unto you not just for myself but for all of my people the Lamanites as well as the Jews and the Lost Ten tribes,” Lee began, before presenting a series of questions:

Who terminated the BYU Indian Education Department?

Who terminated BYU Indian Special Curriculum which helped Indian students succeed in college?

Who is phasing out BYU American Indian Services?

Who is phasing out the Church’s Indian Student Placement program?

Who got rid of the church’s “Indian Committee”?

Who fired the Indian Seminary teachers and send them out into the cold?

Who pulled the full-time missionaries off Navajo and other Indian reservations?

Who moved the mission headquarters from Holbrook to Phoenix?

Who caused missionary work on Indian reservations to falter and make it almost non-existent?

Who is causing a feeling of rejection among Lamanite members on reservations which resulted in great inactivity among them?

Who terminated Indian Seminary and all related curriculum materials?

In addition to the discontinuation of indigenous-focused programs, Lee interrogated what seemed to be an abandoning of Kimball’s theological focus on “Lamanites” as the heritage peoples of the Book of Mormon and heirs to a special destiny as literal members of the House of Israel:

Who is teaching that the “Day of the Lamanites” is over and past?

Who is trying to do everything they can not to be known as a friend of the Indians like President Kimball was?