Despite its seemingly arcane nature, the hadith tradition emerged in the early days of Islam as a practical solution to the needs of the Muslim community. In the wake of the Prophet’s death, his teachings served as an obvious source of guidance for the nascent Islamic community as it struggled to determine how to live according to God’s will now that he was gone. The study of hadiths began as a practical attempt to gather, organize, and sift through the authoritative statements and behavior attributed to the Prophet. In the subsequent centuries, the hadith tradition developed to meet new needs as they evolved. By the close of the tenth century, the transmission and collection of hadiths had acquired a new dimension – quite apart from the contents of any hadith, the report and its isnad became a medium of connection to the Prophet that created authority and precedence within the Muslim community. The development of hadith literature is thus best understood in light of the two general functions that hadiths fulfilled, that of an authoritative maxim used to elaborate Islamic law and dogma, and that of a form of connection to the Prophet’s charismatic legacy.

This chapter traces the origins and development of Sunni hadith transmission and collection from the beginning of Islam until the modern period. Any mention of the notion of ‘authenticity’ or ‘authentic (sahih)’ hadiths in this chapter refers to the Sunni Muslim criteria for reliability and its system of hadith criticism, the mechanics of which will be discussed fully in the next chapter. ‘Authentic’ or ‘forged’ here thus has no necessary correlation to whether or not the Prophet Muhammad really said that statement or not. Debates over ‘what really happened’ in the history of hadith will occupy us in Chapter 8.

In Islam, religious authority emanates from God through His Prophet. Whether by referring to the Prophet’s teachings directly or through the methods of religious problem-solving inherited from him, only through a connection to God and His Prophet does a Muslim acquire the right to speak authoritatively about Islamic law and belief. In the formative period of Islam, Muslims thus turned back again and again to the authoritative legacy of the Prophet’s teachings as it radiated outwards through the transmission and interpretation of pious members of the community. It was the form through which this authoritative legacy was transmitted – whether via Prophetic reports or methods of legal reasoning – that created different schools of thought in the early Islamic period and led to the emergence of the hadith tradition.

In the Prophet’s adopted home, the city of Medina, al-Qasim b. Muhammad b. Abi Bakr (d. 108/726–7), the grandson of the first caliph of Islam, and Sa‘id b. al-Musayyab (d. 94/713), the son-in-law of the most prolific student of the Prophet’s hadiths, Abu Hurayra, became two of the leading interpreters of the new faith after the death of the formative first generation of Muslims. Their interpretations of the Quran and the Prophet’s legacy, as well as those of founding fathers such as the second caliph ‘Umar b. al-Khattab, were collected and synthesized by the famous Medinan jurist Malik b. Anas (d. 179/796). In Kufa, the Prophet’s friend and pillar of the early Muslim community, ‘Abdallah b. Mas‘ud (d. 32/652–3), instructed his newly established community on the tenets and practice of Islam as it adapted to the surroundings of Christian, Jewish, and Zoroastrian Iraq. His disciple ‘Alqama b. Qays (d. 62/681) transmitted these teachings to a promising junior, Ibrahim al-Nakha‘i (d. 95/714), who in turn passed on his approaches and methods of legal reasoning to Hammad b. Abi Sulayman (d. 120/738). His student of eighteen years, Abu Hanifa (d. 150/767), would become a cornerstone of legal study in Iraq and the eponym of the Hanafi school of law. Unlike Medina, the cradle of the Muslim community where Muhammad’s legacy thrived as living communal practice, the diverse environment of Kufa teemed with ancient doctrines and practices foreign to the early Muslim community. Many such ideas found legitimation in the form of spurious hadiths falsely attributed to the Prophet. Abu Hanifa thus preferred relying cautiously on the Quran, well-established hadiths and the methods of legal reasoning learned from his teachers rather than risk acting on these fraudulent hadiths.

By the mid eighth century, two general trends in interpreting and applying Islam had emerged in its newly conquered lands. For both these trends, the Quran and the Prophet’s implementation of that message were the only constitutive sources of authority for Muslims. The practice and rulings of the early community, which participated in establishing the faith and inherited the Prophet’s authority, were the lenses through which scholars like Abu Hanifa and Malik understood these two sources. Another early scholar, ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Awza‘i of Beirut (d. 157/773–4), thus stated that ‘religious knowledge (‘ilm) is what has come to us from the Companions of the Prophet; what has not is not knowledge.’1 In Sunni Islam, a Companion is anyone who saw the Prophet while a Muslim and died as a Muslim. When presented with a situation for which the Quran and the well-known teachings of the Prophet and his Companions provided no clear answer, scholars like Abu Hanifa relied on their own interpretations of these sources to respond. Such scholars were known as the ahl al-ra’y, or the Partisans of Legal Reasoning.

Other pious members of the community preferred to limit themselves to the opinions of the earliest generations of Muslims and more dubious reports from the Prophet rather than speculate in a realm they felt was the exclusive purview of God and His Prophet. The great scholar of Baghdad, Ahmad b. Hanbal (d. 241/855), epitomized this transmission-based approach to understanding law and faith in his famous statement: ‘You hardly see anyone applying reason (ra’y) [to some issue of religion or law] except that there lies, in his heart, some deep-seated resentment. An unreliable narration [from the Prophet] is thus dearer to me than the use of reason.’2 Such transmission-based scholars, referred to as ‘the Partisans of Hadith (ahl al-hadith),’ preferred the interpretations of members of the early Islamic community to their own. For them the Muslim confrontation with the cosmopolitan atmosphere of the Near East threatened the unadulterated purity of Islam. A narcissistic indulgence of human reason would encourage heresy and the temptation to stray from God’s revealed path. Only by clinging stubbornly to the ways of the Prophet and his righteous successors could they preserve the authenticity of their religion.

For the ahl al-hadith, reports traced back to the Prophet, bearing his name and conveying his authority, were prima facie compelling. Even if a scholar were not sure that a hadith was reliable, the powerful phrase ‘the Messenger of God said…’ possessed great authority. Many unreliable hadiths were used in efforts to understand the meaning of Quranic words, to reconstruct the campaigns of the Prophet, to document the virtues of the Companions or simply in preaching that exhorted Muslims towards piety. Even in legal issues, where as we shall see scholars like Ibn Hanbal were more rigorous about authenticating hadiths, ahl al-hadith scholars sometimes depended on unreliable hadiths. It was amid this vying between the ahl al-hadith and ahl al-ra’y schools that the Sunni hadith tradition emerged.

From the beginning of Islam, Muhammad’s words and deeds were of the utmost interest to his followers. He was the unquestioned exemplar of faith and piety in Islam and the bridge between God and the temporal world. Although, as we shall see, there was controversy over setting down the Prophet’s daily teachings in writing, it is not surprising that those Companions who knew how to write tried to record the memorable statements or actions of their Prophet. As paper was unknown in the Middle East at the time (it was introduced from China in the late 700s), the small notebooks they compiled, called sahifas, would have consisted of papyrus, parchment (tanned animal skins), both very expensive, or cruder substances such as palm fronds. Although there is some evidence that the Prophet ordered the collection of his rulings on taxation, these sahifas were not public documents; they were the private notes of individual Companions.3 Some of the Companions recorded as having sahifas were Jabir b. ‘Abdallah, ‘Ali b. Abi Talib, Abu Hurayra and ‘Abdallah b. ‘Amr b. al-‘As.

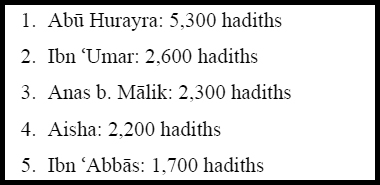

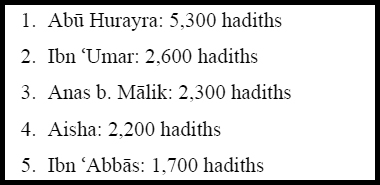

Certain Companions were more active in amassing, memorizing, and writing down hadiths than others. Like grandchildren eager to collect stories and recollections about a grandparent they barely knew, we find that it is often the most junior Companions of the Prophet who became the most prolific collectors and transmitters of hadiths. Abu Hurayra (d. 58/678), who knew the Prophet for only three years, is the largest single source for hadiths, with approximately 5,300 narrations in later hadith collections.4 Although he did not write hadiths down in his early career, by his death Abu Hurayra had boxes full of the sahifas he had compiled.5 ‘Abdallah b. ‘Umar, the son of ‘Umar b. al-Khattab, was twenty-three years old when the Prophet died and is the second largest source for hadiths, with approximately 2,600 narrations recorded in later collections. Ibn ‘Abbas (d. 68/686–8), who was only fourteen years old (or nine according to some sources) when the Prophet died, is the fifth largest source, with around 1,700 hadiths.6

Figure 2.0 Leading Hadith Transmitters from the Companions

Since Companions like Ibn ‘Abbas and Abu Hurayra only knew the Prophet for a short time, they apparently amassed their vast numbers of hadiths by seeking them out from more senior Companions. Abu Hurayra is thus rarely recorded as saying ‘I heard the Prophet of God say…’ – more often he simply states indirectly that ‘the Prophet said …’ Just as today we regularly quote people whom we did not hear directly, this would have been normal for the Companions. The obsession with specifying direct oral transmission with no intermediary, which characterized later hadith scholarship (see Chapter 3), did not exist during the first generations of Islam. Ibn ‘Abbas probably heard only forty hadiths directly from the Prophet. The rest he frequently narrates by saying ‘the Prophet of God said…’ or through a chain of transmission of one, two, or even three older Companions.7

Not surprisingly, those who spent a great deal of intimate time with the Prophet were also major sources of hadiths. Anas b. Malik, who entered the Prophet’s house as a servant at the age of ten, and the Prophet’s favorite wife, Aisha, count as the third and fourth most prolific hadith sources, with approximately 2,300 and 2,200 narrations in later books respectively.8 Interestingly, those Companions who spent the most time with the Prophet during his public life rank among the least prolific hadith transmitters. The Prophet’s close friend and successor, Abu Bakr, his cousin/son-in-law ‘Ali b. Abi Talib, and close advisor ‘Umar are the sources for only 142, 536 and 537 hadiths respectively. These prominent early Muslims, who were looked to as leaders responsible for decisions and religious rulings after the Prophet’s death, seem to have preserved the spirit of Muhammad’s teachings in their actions and methods of reasoning rather than by citing his hadiths directly.

When reading books of hadiths, at first it appears arbitrary which Companion narrates a hadith from the Prophet. Certain Companions, however, demonstrated particular interests and expertise in certain subjects. The Prophet’s wives, especially Aisha, not surprisingly serve as the sources for hadiths about the Prophet’s personal hygiene, domestic habits, and sexual life. Most of the hadiths in which the Prophet instructs his followers about the protocol for using dogs – animals whose saliva is considered ritually impure by most Muslims – for hunting come from the Companion ‘Adi b. Hatim, who clearly was very curious about this topic.

So dominant is the presence of Muhammad in the formative period of Islam that we forget that after his death it was his Companions who assumed both complete religious and political leadership in the community. It was Companions like Ibn ‘Abbas in Mecca, Ibn Mas‘ud in Kufa and Salman al-Farisi in Isfahan who had the responsibility of teaching new generations of Muslims and new converts about the religion of a prophet they had never known. The generation who learned Islam from the Companions and in turn inherited from them the mantle of the Prophet’s authority became known as the Successors (al-tabi‘un). Like the Companions, they too recorded those recollections that their teachers recounted to them about the Prophet’s words, deeds, and rulings. In addition to compiling their own sahifas from the lessons of the Companions, these Successors also passed on the Companions’ own sahifas.

Some of the early isnads that appear most regularly in hadith collections seem to be a record of sahifas being handed down from teacher to student or from father to son. We thus often find the sahifa-isnad of Abu Hurayra to ‘Abd al-Rahman, to his son al-‘Ala’. The Successor Abu al-Zubayr al-Makki received the sahifa of the Companion Jabir b. ‘Abdallah, and one of the most famous Successors, al-Hasan al-Basri (d. 110/728), received the sahifa of the Companion Samura b. Jundub. An example of a sahifa that has survived intact today, the sahifa of the Successor Hammam b. Munabbih (d. 130/747), contains 138 hadiths from the Prophet via Abu Hurayra.9

The vast preponderance of the hadiths that the Successors heard from the Companions, however, was not in written form. Arabian society of the seventh and eighth centuries had a highly developed tradition of oral poetry, and the Companions more often recounted their memories of the Prophet in oral form only. Even to modern readers accustomed to writing everything down, this is understandable to an extent; to them the Prophet was a contemporary figure whose words and deeds lived on in their memories as freshly as we remember our own teachers or parents. Only rarely do we put down these memories on paper.

Of course, the Prophet was no average person, and many of his Companions did seek to record his legacy even during his own lifetime. There are several hadiths, however, in which the Prophet warns his followers not to record his words out of fear that they might be confused with God’s words as revealed in the Quran. As the Quran was still being set down in writing during the Prophet’s lifetime by numerous scribes and in many private notebooks, collections of the Prophet’s teachings might easily be conflated with the holy book. We thus find a famous hadith in which the Companion Abu Sa‘id al-Khudri states, ‘We used not to write down anything but the testimony of faith said in prayer (al-tashahhud) and the Quran.’ In another hadith, the Companion Zayd b. Thabit states that the Prophet had forbidden his followers to write down any of his words.10

It was unrealistic, however, that a lawmaker and political leader like the Prophet could allow no written record keeping. It would simply have been impossible for Muslims to preserve accurately the teachings they heard from the Prophet without some recourse to writing. Alongside hadiths banning writing, we thus also find reports encouraging it. The Companion Anas b. Malik is even quoted as saying, ‘We did not consider the knowledge of those who did not write it down to be [real] knowledge.’11 We thus also find hadiths in which the Prophet allows new Muslims visiting from outside Medina to record lessons he gave in a sermon.12

This contradictory evidence concerning the writing down of hadiths has proven very problematic for both Muslim and Western scholars. Some Muslim scholars, such as the Damascene prodigy al-Nawawi (d. 676/1277), have reconciled the material by assuming that the reports condemning the writing of hadiths came from the earlier years of the Prophet’s career, when he was concerned about his words being mistaken for the Quran. Permission to write down his teachings would have come later, when the Quran had become more established in the minds of Muslims, and the Prophet’s role as the leader of a functioning state required some written records.13

Western scholars, on the other hand, have often understood the tension between the writing of hadiths and its prohibition to reflect competing values within the Islamic hadith tradition itself. In Islam, religious knowledge is primarily oral in nature – a written book only serves as a guide for the oral recitation of its contents. On a conceptual level, it is almost as if written pages are dead matter that only comes alive when read aloud. It is interesting that the importance of oral knowledge kept the debate, over whether or not one should write down hadiths, alive into the 1000s CE, over two hundred years after it had been rendered moot by the popularization of written hadith collections!

In the early Islamic period, however, this focus on orality was very practical. The Arabic alphabet was still primitive, and many letters were written identically and could only be distinguished from one another by context. Even today, the Arabic script does not indicate short vowels. We can imagine an English sentence written with only consonants and a few vowels, such as ‘I wnt t ht the bll.’ Is it ‘I want to hit the ball,’ ‘I want to hit the bell, ’ ‘I went to hit the ball,’ et cetera? We could only know the correct reading of the sentence if we knew its context. With the Arabic script, then, knowing the context and even the intended meaning of a written text is essential for properly understanding it. The sahifas of the Companions and Successors thus only served as memory-aids, written skeletons of hadiths that would jog the author’s memory when he or she read them.

These sahifas could not thus simply be picked up and read. One had to hear the book read by its transmitter in order to avoid grave misunderstandings of the Prophet’s words. If hadith transmitters had reason to believe that a certain narrator had transmitted hadiths without hearing them read by a teacher, in fact, they considered this a serious flaw in the authenticity of that material. Abu al-Zubayr al-Makki had heard only part of the Companion Jabir b. ‘Abdallah’s sahifa read aloud by Jabir, and this undermined his reliability in transmission for some Muslim hadith critics. Some early hadith transmitters, like ‘Ata’ b. Muslim al-Khaffaf, were so concerned about their books of hadiths being read and misunderstood after their deaths that they burned or buried them!14

Of course, this practical and cultural emphasis on direct oral transmission did not mean that Muslims ignored the reliability of written records. Even when transmitting a hadith orally, it was best for a scholar to be reading it from his book. The famous hadith scholar Ibn Ma‘in (d. 233/848) thus announced that he preferred a transmitter with an accurate book to one with an accurate memory.15 By the early 700s CE, setting down hadiths in writing had become regular practice. The seminal hadith transmitter and Successor Muhammad b. Shihab al-Zuhri (d. 124/742) considered writing down hadiths to be absolutely necessary for accurate transmission.

Collectors like al-Zuhri were encouraged to collect and record hadiths by the Umayyad dynasty, which assumed control of the Islamic empire in 661 CE. The Umayyad governor ‘Abd al-‘Aziz b. Marwan requested that the Successor Kathir b. Murra send him records of all the hadiths he had heard from the Companions.16 ‘Abd al-‘Aziz’s son, the Umayyad caliph ‘Umar b. ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, ordered the governor of Medina to record all the hadiths concerning administrative and taxation matters.17

Another important question that arose during the early transmission and collection of hadiths was whether or not one had to repeat a hadith word for word or if one could just communicate its general meaning. Most early Muslim scholars understood that keeping track of the exact wording of hadiths was not feasible and that ‘narration by the general meaning (al-riwaya bi’l-ma‘na)’ was an inescapable reality. The Companion Wathila b. Asqa‘ had admitted that sometimes the early Muslims even confused the exact wording of the Quran, which was universally well-known and well-preserved. So how, he asked, could one expect any less in the case of a report that the Prophet had said just once? Al-Hasan al-Basri is reported to have said, ‘If we only narrated to you what we could repeat word for word, we would only narrate two hadiths. But if what we narrate generally communicates what the hadith prohibits or allows then there is no problem.’ Some early Muslim scholars insisted on repeating hadiths exactly as they had heard them. Ibn Sirin (d. 110/728) even repeated grammatical errors in hadiths that he had heard.18 Eventually, Muslim scholars arrived at the compromise that one could paraphrase a hadith provided that one was learned enough to understand its meaning properly.19

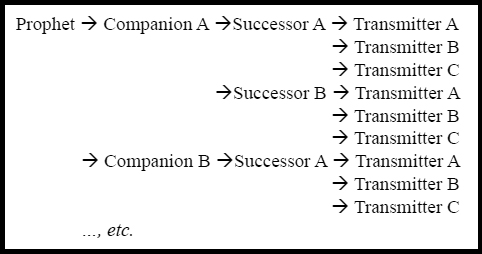

Figure 2.1 Transmission and Criticism of Hadiths from the Companions of the Prophet and Successors

If we imagine the world of Islam in the early and mid eighth century CE, the next stage of hadith literature appears as a direct reflection of Muslim scholarly discourse of the time. We can picture the prominent Successor al-Hasan al-Basri, who had studied with Companions like Anas b. Malik and who had been brought up in the house of one of the Prophet’s wives, as a pillar of piety in Basra and recourse for the questions of the city’s inhabitants. Seated under a reed awning, al-Hasan would answer questions concerning how to pray, how to divide inheritance and how to understand God’s attributes by drawing on all the religious knowledge he had gained. He might reply by quoting the Quran or something that his mother had heard from the Prophet. On other occasions he might tell his audience how ‘Ali b. Abi Talib, whom he had met as a young man, had ruled on a particular case. Sometimes al-Hasan might use his own understanding of the principles put forth in the Quran or the Prophet’s teachings to provide a new answer to a question. A few decades later in Medina, we can picture Malik b. Anas seated against one of the pillars of the Prophet’s mosque and answering questions in a similar way.

The first organized works of Islamic scholarship, called musannafs, or ‘books organized topically,’ were basically transcripts of this legal discourse as it had developed during the first two centuries of Islam. Arranged into chapters dealing with different legal or ritual questions, they were topical records of pious Muslims’ efforts to respond to questions about faith and practice. The earliest surviving musannaf, Malik’s Muwatta’, is thus a mixture of Prophetic hadiths, the rulings of his Companions, the practice of the scholars of Medina, and the opinions of Malik himself. The version of the Muwatta’ that became famous in North Africa and Andalusia contains 1,720 reports. Of these, however, only 527 are Prophetic hadiths; 613 are statements of the Companions, 285 are from Successors, and the rest are Malik’s own opinions.20 Likewise, the earliest known musannaf, that of Ibn Jurayj (d. 150/767), was a collection of reports from the Prophet, Companions, and Successors such as ‘Ata’ b. Abi Rabah (d. 114/732). Another famous scholar from this period who compiled a musannaf was the revered scholar of Kufa, Sufyan al-Thawri (d. 161/778).

A very large musannaf surviving from this earlier period was written by a student of Malik and Ibn Jurayj, ‘Abd al-Razzaq al-San‘ani (d. 211/826), but is much larger than the one-volume Muwatta’. The Musannaf of ‘Abd al-Razzaq, an inhabitant of Yemen, is eleven printed volumes. As Figure 2.2 demonstrates, ‘Abd al-Razzaq drew mostly from his teachers Ma‘mar b. Rashid and Ibn Jurayj.21 Another famous musannaf, written by a scholar from the generation of ‘Abd al-Razzaq’s students, comes from the hadith scholar of Baghdad, Abu Bakr b. Abi Shayba (d. 235/849). Figure 2.2 provides an example of the type of material and sources that a musannaf would draw upon.

Chapter on Whether or not One Should Wipe One’s Head with the Water Remaining from One’s Hands

From ‘Abd al-Razzaq, from Ma‘mar, who said that he was informed by someone who heard al-Hasan [al-Basri] say, ‘It suffices you to wipe your head with what water is left over in your hands from ablution.’

(Note: this is a Successor opinion with an incomplete isnad)

From ‘Abd al-Razzaq, from Isra’il [b. Yunus], from Musa b. Abi ‘A’isha, who said that he heard Mus‘ab b. Sa‘d, when a man asked him, say, ‘I perform my ablutions and wash my face and arms, and what water is in my hands suffices me for my head, or I get new water for my head. Nay, rather, get new water for your head.’

(Note: this is a Successor opinion with a complete isnad)

‘Abd al-Razzaq said that Ma‘mar informed him, from Nafi‘ that Ibn ‘Umar used to get new water for wiping his head.

(Note: this is a Companion opinion with a complete isnad)

From ‘Abd al-Razzaq, from Ibn Jurayj, who said that he was informed by ‘Ajlan that the Prophet used to wipe his ears along with his face one time and wipe his face. Then he would put his palms in the water and wipe his head from front to back to the back of his neck, then his temples. Then he would wipe his ears once – all of this with what water he had in his hand from that one wipe.

(Note: this is a Prophetic hadith with an incomplete isnad)

From ‘Abd al-Razzaq, from Ibn Jurayj, who said, ‘I said to ‘Ata’, “Is it with the water left over from your face that you wipe your head?” and he said, “No, I put my hands in the water and wipe with them, and I do not shake the water off them or wait for them to dry. In fact I try to keep the hairs [on my hands and arms] wet.”’

(Note: this is a Successor opinion with a complete isnad)

Figure 2.2 Subchapter from ‘Abd al-Razzaq’s Musannaf Concerning Ablutions

In many ways, the musannaf genre predates the emergence of classical hadith literature rather than being part of it. If hadith collections are characterized by a predominant focus on reports from the Prophet that include isnads as a means for critics to verify their authenticity, then books like the Muwatta’ and the Musannaf of ‘Abd al-Razzaq are not technically hadith collections. Both Malik and ‘Abd al-Razzaq cite rulings of Companions and Successors more frequently than they cite Prophetic hadiths. But even when quoting the Prophet directly, the obsession with complete, unbroken chains of transmission that would characterize the classical period of hadith collection is absent. Even when Malik does cite Prophetic hadiths, on sixty-one occasions he completely omits the isnad and simply states, ‘The Prophet said…’ Rather, we should think of musannafs as early works of Islamic law that represent the diversity of sources from which legal and doctrinal answers could be sought during the first two centuries of Islam. In a musannaf, a scholar like Malik was trying to answer questions with the resources he felt were reliable and was not concerned with proving their authenticity according to a rigid system of isnad authentication.

Of course, musannafs would serve a very important function in law, hadith literature, and hadith criticism. Later scholars would turn to musannafs to know the legal opinions of Companions and Successors, and hadith critics would use them as evidence when investigating whether a hadith was really something said by the Prophet or a statement actually made by a Companion or Successor.

But if Muhammad was the ultimate interpreter of God’s will, why would a scholar like Malik so infrequently rely on his words in a musannaf collection? This question has cast a shadow of doubt over the authenticity of the hadith corpus, a question addressed in Chapter 8. Here, however, we can provide a few possible explanations. As Figure 2.1 demonstrates, during the time of Malik and Ibn Jurayj hadith transmission was localized. When Malik was asked by a student whether or not one should wash in between one’s toes when performing ritual ablutions, he said that it was not required. Another student, ‘Abdallah b. Wahb, objected, saying that in his native Egypt they had a hadith through the Companion Mustawrid b. Shaddad telling how the Prophet did wash between his toes. Hearing the isnad, Malik said, ‘That hadith is good, and I had not heard it until this moment.’ He acted on it from that point on.22 It is not surprising that Malik had not heard the hadith, since he only left his home in Medina to perform pilgrimage to the nearby city Mecca. Many of the hadiths that were widespread in Syria, Egypt, or among the students of Abu Hanifa in Iraq were unknown to him. It is thus very likely that Malik did not cite a Prophetic hadith on an issue because he knew of none. As Figure 2.1 indicates, it was only among the generation of Malik’s students, and even more so among their students, that hadith scholars traveled widely in order to unify the corpus of hadiths.

In addition, musannafs drew on such a wide variety of authoritative figures because they were all legitimate inheritors of the Prophet’s authority. The Companions, who had lived with the Prophet for years and understood the principles upon which he acted, and the Successors, who learned from them, were seen as the carriers of the Prophet’s message and were heeded accordingly. Even a scholar like Malik, living in the generation after the Successors, was so esteemed as a pious interpreter of the Prophet’s message that he could give his opinion without citing any sources at all.

The shift from the variety of the musannaf to the focus on Prophetic hadiths that characterizes hadith literature occurred with the emergence of the musnad collections in the late eighth and early ninth centuries CE. While sahifas had been mere ad hoc collections, and musannafs were arranged as topical references, musnad collections were organized according to isnad. All the hadiths narrated from a certain Companion would fall into one chapter, then all those transmitted from another into the next, et cetera. The appearance of musnad collections occurred due to impetuses from both the broader study of Islamic law and within the more narrow community of Muslim hadith critics.

During the late eighth and early ninth centuries, the regional schools of Islamic law, each based on the teachings and interpretation of learned figures like Malik and Abu Hanifa, faced a new challenge. A young scholar named Muhammad b. Idris al-Shafi‘i (d. 204/820), who had studied with Malik in Medina and the students of Abu Hanifa in Iraq, and had traveled widely in Egypt and Yemen, asserted that it should be the direct hadiths of the Prophet and not his precedent as understood by local scholars that supplemented the Quran as the second major source of law. In the face of a contrasting hadith that they had not previously known, al-Shafi‘i argued, the followers of Malik and Abu Hanifa should take the Prophet’s words over the stances of their local schools. Through his students and especially the study of his major legal work, the Umm (The Motherbook), al-Shafi‘i had an immediate and powerful influence on ahl al-hadith jurists. From this point on in the hadith tradition, the testimony of Muhammad would trump all other figures of authority and become the predominant focus of hadith collections. Musnads reflected this interest, as they focused almost entirely on Prophetic hadiths and included Companion or Successor opinions only as occasional commentaries.

Quite apart from broader questions of legal theory, the burgeoning class of Muslim hadith critics that emerged in the mid and late eighth century had good reason to start organizing their personal hadith collections along isnad lines. First, the growing number of reports erroneously attributed to the Prophet had made the isnad an indispensable tool. Limiting hadith collections to material that had an isnad was a solid first line of defense against hadith forgery – if you claimed that the Prophet had said something but could provide no isnad, your hadith had no place in a musnad. Second, as we will see in the next chapter, the single most important factor in judging the reliability of a hadith transmitter was determining if he or she was corroborated in the material he or she reported. In order to know if a hadith transmitter is corroborated in his transmissions, critics compared the hadiths he reported to those of others who studied with his teachers. Thus we find that many musnads, such as that of al-Ruyani (d. 307/919–20), are organized into chapters and subchapters in the following fashion:

Figure 2.3 Musnad Organization

In order to determine whether or not Transmitter A is generally corroborated in the material he or she transmits, we need only flip through the chapters of the musnad comparing the hadiths that Transmitter A related from each Successor with those of Transmitters B and C.

The earliest known musnad, which has also survived intact, is that of Abu Dawud al-Tayalisi (d. 204/818). The most famous musnad is that of Ibn Hanbal, which consists of about 27,700 hadiths (anywhere from one fourth to one third of which are repetitions of hadiths via different narrations) and was actually assembled into final form by the scholar’s son. Ibn Hanbal claimed he had sifted the contents of his Musnad from over 750,000 hadiths and intended it to be a reference for students of Islamic law. Although he acknowledged that the book contained unreliable hadiths, he supposedly claimed that all its hadiths were admissible in discussions about the Prophet’s Sunna – if it was not in his Musnad, he claimed, it could not be a proof in law.23

Other well-known and widely read musnads from the ninth century include those of al-Humaydi (d. 219/834), of al-Harith b. Abi Usama (d. 282/896), of al-Musaddad (d. 228/843), of Abu Bakr al-Bazzar (d. 292/904–5), and of the Hanafi scholar Abu Ya‘la al-Mawsili (d. 307/919). The largest musnad ever produced, which has tragically not survived, was that of Baqi b. Makhlad (d. 276/889).

Instead of compiling large musnads that included the hadiths of numerous Companions, some scholars devoted books to only one Companion: Abu Bakr al-Marwazi (d. 292/904–5), for example, compiled a small musnad with all the hadiths he had come across transmitted from the Companion Abu Bakr.

Although some musnads, like that of al-Bazzar, contained some discussion of the flaws (‘ilal) found in the isnads of a hadith, in general musnads were not limited to hadiths their compilers believed were authentic. Instead, they functioned as storehouses for all the reports that a certain hadith scholar had heard. As Figure 2.1 shows, by the time of Ibn Hanbal, hadith collectors were no longer constrained by regional boundaries. Hadith collectors like Muhammad b. Yahya al-Dhuhli or Qutayba b. Sa‘id were originally from Nishapur in Iran and Balkh in Afghanistan, but they traveled throughout the Muslim world on what was known as ‘the voyage in the quest for knowledge (al-rihla fi talab al-‘ilm)’ to collect hadiths from transmitters like ‘Abd al-Razzaq in Yemen or Layth b. Sa‘d in Egypt. Throughout their travels they recorded the hadiths they heard in their musnads regardless of their authenticity or their legal and doctrinal implications. The staunch Sunni Ibn Hanbal’s Musnad thus contains a hadith – shocking to the sensibility of Sunni Muslims – that describes how an early copy of the Quran had been stored under Aisha’s bed only to be found and partially eaten by a goat, leaving the record of God’s revelation permanently truncated!24

Musannafs and musnads both had their advantages: musannafs were conveniently arranged by subject, and musnads focused on Prophetic hadiths with full isnads. From the early ninth to the early tenth century, a large number of respected ahl al-hadith jurists combined the two genres in the form of sunan/ sahih books. A sunan was organized topically, and thus easily used as a legal reference, but also focused on Prophetic reports with full isnads. More importantly, the ahl al-hadith jurists who compiled these sunans devoted great efforts to assuring or discussing the authenticity of the books’ contents. In general, the authors of sunan books sought only to include hadiths that had been relied upon by Muslim scholars and were known to be authentic either because they had strong isnads or because the community of scholars had agreed that they truly reflected the Prophet’s teachings. This new focus on producing collections of hadiths with an emphasis on authenticity led many of the collections produced in the sunan movement to be dubbed sahih (authentic) books by either their authors or later Muslim readers. Two of the earliest known sunans are those of Sa‘id b. Mansur al-Khurasani (d. 227/842) and ‘Abdallah al-Darimi (d. 255/869).

Two participants in the sunan movement in particular, Muhammad b. Isma‘il al-Bukhari (d. 256/870) and his student Muslim b. al-Hajjaj al-Naysaburi (d. 261/875), broke with the ahl al-hadith’s traditional willingness to use weak hadiths in law. Unlike their teacher Ibn Hanbal, al-Bukhari and Muslim felt that there were enough authentic hadiths in circulation that the ahl al-hadith jurists could dispense with less worthy narrations. Al-Bukhari and Muslim were thus the first to produce hadith collections devoted only to hadiths whose isnads they felt met the requirements of authenticity. Their books were the first wave of what some have termed ‘the sahihmovement.’25 Known as the Sahihayn (literally ‘the two Sahih s’), the collections of al-Bukhari and Muslim would become the most famous books of hadith in Sunni Islam. It is therefore worth examining their contents and structure.

It is reported that al-Bukhari devoted sixteen years to sifting the hadiths he included in his Sahih from a pool of six hundred thousand narrations.26 The finished work was not a mere hadith collection – it was a massive expression of al-Bukhari’s vision of Islamic law and dogma backed up with hadiths the author felt met the most rigorous standards of authenticity. The book covers the full range of legal and ritual topics, but also includes treatments of many other issues such as the implication of technical terms in hadith transmission. The book consists of ninety-seven chapters, each divided into subchapters. The subchapter titles indicate the legal implication or ruling the reader should derive from the subsequent hadiths, and often include a short comment from the author or a report from a Companion or Successor elucidating the hadith. Al-Bukhari often repeats a Prophetic tradition, but through different narrations and in separate chapters. Opinions have varied about the exact number of hadiths in the Sahih, depending on whether one defines a ‘hadith’ as a Prophetic tradition or a narration of that tradition. Generally, experts have placed the number of full-isnad narrations at 7,397. Of these many are repetitions or different versions of the same report, with the number of Prophetic traditions at approximately 2,602.27

Muslim’s Sahih is much more a raw hadith collection than al-Bukhari’s work. It contains far fewer chapters (only fifty-four) and lacks al-Bukhari’s legal commentary. It has many more narrations, numbering about twelve thousand, with Muslim scholars placing the number of Prophetic traditions at around four thousand. Unlike al-Bukhari, Muslim keeps all the narrations of a certain hadith in the same section. Muslim also diverges significantly from al-Bukhari in his exclusion of commentary reports from Companions and later figures.

There is considerable overlap between the Sahihayn. Muslim scholars generally put the number of traditions found in both books at 2,326. Al-Bukhari and Muslim drew on essentially the same pool of transmitters, sharing approximately 2,400 narrators. Al-Bukhari narrated from only about 430 that Muslim did not, while Muslim used about 620 transmitters al-Bukhari excluded.

Al-Bukhari’s and Muslim’s works had a great deal of influence on their students and contemporaries. Ibn Khuzayma (d. 311/923), a central figure in the Shafi‘i school who studied with al-Bukhari and Muslim, compiled a Sahih work that came to be known as Sahih Ibn Khuzayma. Abu Hafs ‘Umar al-Bujayri of Samarqand (d. 311/924) produced a collection called al-Jami‘ al-sahih,and even the famous historian and exegete Muhammad b. Jarir al-Tabari (d. 310/923) attempted a gigantic sahih work but died before he finished it. Sa‘id b. al-Sakan (d. 353/964) of Egypt also collected a small sahih book consisting of hadiths necessary for legal rulings and whose authenticity he claimed was agreed on by all. Ibn Khuzayma’s student Ibn al-Jarud (d. 307/919–20) compiled a similar work called al-Muntaqa (The Select). Ibn Hibban al-Busti’s (d. 354/965) massive sahihis usually considered the last installment in the sahih movement.

Other participants in the sahih movement also focused on hadiths with strong and reliable isnads, but they nonetheless featured some reports that they acknowledged as being unreliable but included either because they were widely used among jurists or because the authors, like Ibn Hanbal, could find no reliable hadith addressing that topic. Four of these books in particular attained great renown. The Sunan of Abu Dawud al-Sijistani (d. 275/889), a close student of Ibn Hanbal, contains about 4,800 hadiths and focuses on reports used in deriving law. The author alerts the reader to any narrations which have serious flaws in their isnads. The Jami‘ of Muhammad b. ‘Isa al-Tirmidhi (d. 279/892), one of al-Bukhari’s disciples, contains about 3,950 hadiths and also focuses on hadiths that different schools of law had used as legal proofs. It also includes detailed discussions of their authenticity. Although al-Tirmidhi’s sunan does include some unreliable hadiths, the author notes their status. As such, later scholars often called the work Sahih al-Tirmidhi. Ahmad b. Shu‘ayb al-Nasa’i (d. 303/916), another student of al-Bukhari, compiled two sunans: the larger one contained many hadiths that the author acknowledged as unreliable. The smaller one, known as the Mujtaba (The Chosen), contains 5,750 hadiths and focused on reliable hadiths only. It has thus been known as Sahih al-Nasa’i. Finally, Muhammad b. Yazid b. Majah’s (d. 273/887) Sunan is an interesting case. Although the author seems to have tried to include only reliable hadiths, some later Muslim scholars noted that as much as one fourth of the book’s 4,485 hadiths are actually unreliable.28

With the sahih/sunan movement, the hadith tradition had reached a watershed. The works of scholars like al-Bukhari, Muslim and al-Tirmidhi were possessed of a definitiveness that seemed both to reject many aspects of the culture of hadith transmission and to offer themselves as the ultimate hadith references for legal scholars. Muslim wrote his Sahih as a response to what he saw as the laxity and misplaced priorities of hadith scholars and transmitters. He believed that those scholars who strove to collect as many hadiths as possible regardless of their quality were doing so only to impress others.29 Muslim expressed serious concern over would-be hadith scholars who transmitted material of dubious nature to the exclusion of well-known and well-authenticated hadiths. They provided this material to the common people when in fact it is hadith scholars’ duty to leave the common folk with trustworthy reports only. Muslim composed his Sahih to fulfill this function. Abu Dawud expressed a similar purpose for his Sunan. He states confidently that he knows of ‘nothing after the Quran more essential for people to learn than this book [his Sunan], and a person would suffer no loss if he did not take in any more knowledge after it.’30

During the ninth and tenth centuries, Sunni hadith scholars were not merely writing comprehensive sunan works. They also compiled collections of hadiths dealing with individual topics. In fact, these specific treatises were often bound together to form a sunan or added on to the standard legal chapters of a sunan to add a new component to the work.

The earliest genre of topical works was that of zuhd, or asceticism and pious excellence. These books included hadiths describing the Prophet’s supreme piety and abstention from any religiously ambiguous behavior, as well as the superlative practice of early Muslim saints and even pre-Islamic prophets. The earliest known book of zuhd is that of Ibn al-Mubarak (d. 181/797). The great hadith transmitters and collectors Waki‘ b. al-Jarrah (d. 197/812) and Ibn Hanbal also compiled books of zuhd. Even as late as the eleventh century the Shafi‘i scholar Abu Bakr al-Bayhaqi (d. 458/1066) wrote a hadith collection devoted to the zuhd theme.

Other scholars wrote books similarly addressing the question of perfecting Muslim manners. Al-Bukhari wrote his ‘Book Devoted to Manners (al-Adab al-mufrad)’, and a scholar named Ibn Abi al-Dunya (d. 281/894) of Baghdad wrote dozens of such hadith works on topics such as the importance of giving thanks, understanding dreams, and coping with sadness and grief. The hadith scholar Humayd b. Zanjawayh (d. 251/855–6) composed a book of hadiths that warned Muslims about the punishments that awaited them in Hellfire for certain deeds as well as the heavenly rewards they could expect in Paradise for goodly acts. Known as the Kitab al-targhib wa al-tarhib (The Book of Enjoining and Warning), Ibn Zanjawayh’s book was very popular and was transmitted widely. In the 1200s CE, ‘Abd al-‘Azim al-Mundhiri (d. 656/1258) wrote another famous book in this genre with the same title. Al-Nasa’i and his student Ibn al-Sunni (d. 364/975) both wrote hadith books entitled ‘Deeds of the Day and Night (‘Amal al-yawm wa al-layla)’ on the pious invocations that the Prophet would say in various daily situations. The famous young scholar of Damascus, al-Nawawi (d. 676/1277), also wrote two very popular hadith books on manners and perfecting Muslim practice. His small Adhkar (Prayers) contains hadiths on the prayers one says before activities such as eating, drinking, and traveling with no isnads but with the author’s comments on their reliability. Al-Nawawi’s Riyad al-salihin min kalam sayyid al-mursalin (The Gardens of the Righteous from the Speech of the Master of Prophets) is a larger book of ethical, piety, and etiquette-related hadiths which has become extremely popular, serving as a main hadith text for the Tabligh-i Jama‘at, one of the largest missionary institutions in the modern Muslim world.

Similarly designed to frighten readers about the impending apocalypse and coming of ‘the Days of God’ was an early topical hadith book written by al-Bukhari’s teacher Nu‘aym b. Hammad (d. 228/842) entitled Kitab al-fitan (The Book of Tribulations). Sunan and sahih books regularly contained chapters on these apocalyptical ‘tribulations’ as well.

The most popular subject for topical hadith collections among Sunni scholars in the ninth and tenth centuries was the importance of adhering to the Sunna of the Prophet and the ways of the early Muslim community on issues of belief and practice. These books of ‘sunna’ contained Prophetic hadiths and reports from respected early Muslims that exhorted readers to derive their understanding of religion solely from the revealed texts of the Quran and Sunna while avoiding the heretical pitfalls of speculative reasoning about God, His attributes and the nature of the afterlife. Sunna books emphasized all the components of the Sunni Muslim identity as it was emerging in the eighth and ninth centuries: a reliance on transmitted knowledge instead of speculative reasoning, a rejection of the ahl al-ra’y legal school, an affirmation that all the Companions of the Prophet were upright (but that the best were Abu Bakr, ‘Umar, ‘Uthman then ‘Ali), and political quietism. The most famous books of sunna are those of Ibn Hanbal’s son ‘Abdallah (d. 290/903), Ibn Abi ‘Asim (d. 287/900), Muhammad b. Nasr al-Marwazi (d. 294/906), and al-Barbahari (d. 329/941).

Some later sunna hadith collections went into more detail on issues of proper Sunni belief. The staunch Hanbali Sufi Khwaje ‘Abdallah al-Ansari of Herat (d. 481/1089) wrote a multi-volume hadith work condemning speculative theology and theologians (Dhamm al-kalam wa ahlihi). Ibn al-Waddah (d. 286/899) wrote a small book on heretical innovation (Kitab al-bid‘a), while al-Daraqutni (d. 385/995) wrote one treatise collecting all the hadiths affirming that Muslims would actually see God on the Day of Judgment (Kitab al-ru’ya) and another one bringing together all the hadiths telling that God descends during the night to answer the prayers of the believers.

The collective affirmation that all the Companions of the Prophet were righteous and reliable transmitters of the Prophet’s teachings, as opposed to the Shiite denigration of all the Companions who did not support ‘Ali’s claim to leadership, prompted another important topical genre in the ninth century. Books on the ‘Virtues of the Companions (fada’il al-sahaba)’ became an important statement of Sunni belief. Ibn Hanbal thus collected all the hadiths he could find in which the Prophet described the excellence or special characteristics of each Companion in his Fada’il al-sahaba. Al-Nasa’i also wrote a shorter Fada’il al-sahaba work as well as a hadith collection specifically devoted to ‘Ali’s virtues (Khasa’is ‘Ali).

Although only a few books were written in the genre, books of shama’il, or the virtues and characteristics of the Prophet, were extremely popular in Islamic civilization. Such books discussed all aspects of the Prophet’s personality, appearance, conduct, and miracles, and were often the only books through which the less educated segments of Muslim society from Mali to India would have had contact with high religious tradition. Al-Tirmidhi’s Shama’il was extremely widely read, as was al-Qadi ‘Iyad’s (d. 544/1149) Kitab al-shifa. The Egyptian Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti (d. 911/1505) also wrote a later shama’il work entitled al-Khasa’is al-kubra. As al-Qadi ‘Iyad explained, these books were not designed to convince non-Muslims of Muhammad’s prophethood, but rather to reinforce Muslims’ faith in the unique and unparalleled virtues of ‘the last of God’s messengers.’31

Another genre of topical collections focused on stories about Muhammad that proved or illustrated his standing as a prophet. The most famous works of Dala’il al-nubuwwa (proofs of prophethood) come from the eleventh-century scholars al-Hakim al-Naysaburi (d. 405/1014) and his students Abu Nu‘aym al-Isbahani (d. 430/1038) and Abu Bakr al-Bayhaqi.

Like musnads, these various monographs were unconcerned with assuring the authenticity of the hadiths they contained. In fact, books on the virtues of Companions and sunna often contained reports that later Sunni scholars and sometimes the authors themselves found baseless or reprehensible. The Kitab al-sunna of Ibn Abi ‘Asim, that of Ibn Hanbal’s son ‘Abdallah and the Kitab al-tawhid (Book of God’s Unity) of Ibn Khuzayma all included a hadith describing how when God sits on His throne it squeaks like a saddle mounted by its rider. But even Ibn Hanbal’s son notes the hadith’s isnad is weak, and later Sunni scholars were so shocked by this blatant anthropomorphism that some of them called Ibn Khuzayma’s book ‘The Book of Heresy.’32 In his Fada’il al-sahaba, Ibn Hanbal includes a report stating that ‘Ali’s name is written on the doorway to Paradise, a hadith rejected by Sunni scholars as forged.33

The question of why hadith scholars would knowingly include unreliable or obviously forged reports in any of their books is a perpetual quandary in the study of the hadith tradition and will be discussed in depth in the next chapter. In the context of books exhorting Sunnis to the proper beliefs and worldview, however, it makes sense from the authors’ standpoint. These books were often polemics aimed at other sects, such as Muslim rationalists (known as Mu‘tazilites) or Shiites. Sunni compilers of these books were not trying to prove anything to other Sunnis, who shared their system of hadith evaluation. They ‘knew’ they were upholding the correct set of beliefs, so they packed their books with whatever evidence they could find to support them regardless of its reliability. Authors of books of sunna were arguing that, instead of relying on reason, Muslims should believe in material transmitted from the Prophet no matter what it said. A hadith about God’s throne squeaking was as useful in this cause as more reliable hadiths.

It would be some time before the landmark contribution of the Sahih and sunan books was recognized. By the dawn of the eleventh century, however, a selection of these books had been recognized as authoritative. This canon of books would fulfill two important functions in Islamic civilization: providing a common language for discussing the Prophet’s Sunna and providing a manageable representation of the vast hadith corpus.

Surprisingly, al-Bukhari’s and Muslim’s decision to compile books limited only to hadiths they deemed authentic was initially rejected by many ahl al-hadith scholars. This seems counterintuitive from a modern standpoint; why would a tradition that prided itself on following the authentic legacy of the Prophet object to books of only authentic hadiths? In order to understand this we must remember that, for the ahl al-hadith, authentic hadiths only represented the most reliable end of the hadith spectrum. Hadiths with less stellar isnads were also used in law, and weak hadiths were used very commonly in preaching, Quranic exegesis, and books of zuhd and good manners.

Many ahl al-hadith scholars during al-Bukhari’s and Muslim’s time therefore criticized the compilation of the Sahihayn. A famous hadith scholar from Rayy in Iran, Abu Zur‘a al-Razi (d. 264/878), said of the two authors, ‘These are people who wanted prominence before their time, so they did something of which they could boast; they wrote books the likes of which none had written before to gain for themselves precedence.’ The ahl al-hadith also worried that if hadith scholars wrote books limited to authentic hadiths, their opponents from the ahl al-ra’y would use that as a weapon against them. Abu Zur‘a described Muslim as ‘making a path for the people of heresy against us, for they see that they can respond to a hadith that we use as proof against them by saying “That is not in the Sahih!” ’ Under fire from such critics, al-Bukhari and Muslim defended themselves by saying that their books did not include all the sahih hadiths in circulation. Al-Bukhari had only selected sahih hadiths useful for his legal discussions, and Muslim had limited his book to hadiths whose authenticity he believed was agreed on by all.34

By the mid tenth century, however, the contribution of the sahih/sunan movement was beginning to be realized. Previously, it was the collectors of the great musnads, al-Bukhari’s and Muslim’s teachers like Ibn Hanbal and al-Humaydi, who had been viewed as the pillars of hadith scholarship. In the late 900s, however, Ibn Manda of Isfahan (d. 395/1004–5) announced that the four masters of hadith were those who had produced the sahih books: al-Bukhari, Muslim, Abu Dawud, and al-Nasa’i. Ibn Manda described these four as well as others of their generation as the group of hadith masters ‘accepted by all by consensus, and their knowledge trumps all others.’35

The need for a selection of hadith collections acknowledged as superior by all the ahl al-hadith was essential at that point in time. In light of all the musannafs, musnads, and sunans in circulation between the various cities that hadith scholars visited on their ‘travels in search of knowledge,’ which books should students focus on as the foundation for understanding the Prophet’s legacy? When a group of intimidated hadith students asked the Egyptian scholar Ibn al-Sakan (d. 353/964) this question, he entered his house and reemerged with four books in his hands. ‘These are the foundations of Islam,’ he said, ‘the books of Muslim, al-Bukhari, Abu Dawud, and al-Nasa’i.’36

Different scholars had different visions of which books best represented the Prophet’s Sunna. These shifting canons are usually referred to as ‘The Five Books,’ ‘The Six Books,’ or ‘the Authentic Books (al-Sihah).’ The foundation of the canon, however, is unchanging: the four works of al-Bukhari, Muslim, Abu Dawud, and al-Nasa’i. The Shafi‘i scholar Abu Bakr al-Bayhaqi (d. 458/1066) adds that, together with these four, al-Tirmidhi’s and Ibn Khuzayma’s books had identified a substantial amount of the authentic hadiths in circulation. Muhammad b. Tahir al-Maqdisi (d. 507/1113) described the Six Books as those of al-Bukhari, Muslim, al-Tirmidhi, al-Nasa’i, Abu Dawud, and Ibn Majah. ‘Abd al-Karim al-Rafi‘i of Qazvin (d. 623/1226) also enumerates this six-book series, as does the Indian Hanafi scholar al-Saghani (d. 650/1252), adding the Sunan of al-Daraqutni as well. The Andalusian hadith scholar, al-Saraqusti (d. 524/1129), on the other hand, counts the Six Books as those of al-Bukhari, Muslim, al-Tirmidhi, Abu Dawud, al-Nasa’i, and Malik. Al-Silafi of Alexandria (d. 576/1180), Abu Bakr al-Hazimi (d. 584/1188-9), and al-Nawawi mention only Five Books: the works of al-Bukhari, Muslim, al-Tirmidhi, Abu Dawud, and al-Nasa’i.37 Together, the Six Books contain approximately 19,600 hadiths.

The flexible boundaries of the hadith canon make sense when we consider one of its two primary functions. Even as early as 800 CE, al-Shafi‘i had said that it was impossible for one person to know all the hadiths in circulation.38 If the Prophet’s Sunna was essentially boundless, the Muslim community needed a tangible and manageable selection of hadith books to represent its core. Whether the canon was five or six books, or exactly which books these were, did not affect this function.

In the 1200s and 1300s the hadith canon’s ability to represent the Prophet’s blessings endowed the Sahihayn in particular with a special ritual relevance. In cities from Damascus to Timbuktu the Sahihayn would be read in mosques as part of celebrations culminating in the month of Ramadan. Al-Bukhari’s Sahih in particular was read as a cure for illness from Egypt to India, and the great Moroccan conqueror Mawla Isma‘il (d. 1727) had a copy of the Sahih carried in front of his army ‘like the Ark of the Children of Israel.’39

The second, more important function of the hadith canon was limited to the Sahihayn – the only two books of the canon which included exclusively authentic hadiths. These two books served as a common reference for determining hadith authenticity. In the early 1000s the two schools of law that had emerged from the ahl al-hadith, the Hanbali and the Shafi‘i, agreed that the contents of the Sahihayn were totally authentic and had been agreed upon as such by the whole Muslim community. Scholars of the Maliki school soon agreed, and by the 1300s even the hadith-wary Hanafi school had found acknowledging this convention unavoidable. For all the Sunni schools of law and theology, the Sahihayn would be the common language for evaluating the authenticity of hadith in interschool debates.

The Sahihayn canon was an ideal polemical weapon to use against one’s opponents. But that did not mean that scholars felt they had to obey all the hadiths found in the two collections in their own work. If a scholar of the Shafi‘i or Hanafi school of law found a hadith in al-Bukhari’s or Muslim’s collections that he disagreed with, he had no compunction about criticizing its authenticity.40

The Sahihayn were thus not immune to criticism. Only in the early modern and modern periods has it become controversial to criticize the Sahihayn, but this is primarily due to Muslim scholars’ eagerness to protect the status of two books that they see as symbols of an Islamic tradition under attack from modernity. It is important to note here, as will be discussed further below, that Muslim scholars recognized that other sahih hadiths existed outside the hadith canon.

As al-Bukhari’s and Muslim’s critics had insisted, the sahih movement did not mean the end of hadith transmission and collection. Nor did it mean that Muslims believed that all the sahih hadiths in circulation had been recorded. In fact, from the standpoint of volume, the peak of hadith collection occurred in the tenth century – over one hundred years after the Six Books had been written.

Indeed, the compilation of titanic personal musnads continued after and even despite the sahih movement, with scholars in Iran continuing the tradition of collecting musnads with many weak and even forged hadiths. Abu al-Qasim al-Tabarani (d. 360/971) of Isfahan compiled a huge collection, his Mu‘jam al-kabir, which is today printed in twenty-eight volumes. ‘Ali b. Hamshadh of Nishapur (d. 338/950) produced a personal musnad twice as large as al-Tabarani’s, and al-Hasan al-Masarjisi of Nishapur (d. 365/976) compiled a musnad that if published today would occupy an astounding 182 volumes.41 Even as late as the mid 1100s Shahrudar b. Shirawayh al-Daylami (d. 558/1163) compiled a famous hadith collection entitled Musnad al-Firdaws (The Musnad of Paradise).

Into the 1000s scholars with strong affiliations to certain schools of law produced massive sunans and musnads to bolster their schools’ bodies of substantive law. The vast Sunan al-kubra of the Shafi‘i Abu Bakr al-Bayhaqi (d. 458/1066) is a landmark in the Shafi‘i legal school, supporting every detail of its law code with a myriad of reports from the Prophet and his Companions. Abu al-‘Abbas al-Asamm of Nishapur (d. 346/957) collected all the hadiths that al-Shafi‘i had transmitted with full isnads in his magnum opus, the Umm, and organized them into the Musnad al-Shafi‘i.42 Even a non-Hanafi like Abu Nu‘aym al-Isbahani (d. 430/1038) participated in efforts to find chains going back to the Prophet for Abu Hanifa’s reports and composed a musnad collection of them.43 The Maliki scholar Ibn al-Jabbab (d. 322/934) created a musnad of Malik’s hadiths.44

All these scholars continued to transmit hadiths in the great mosques of Iraq and Iran before audiences of hundreds and even thousands of students. These ‘dictation sessions’ were recorded by students in collections called amali (dictations). The chief judge of Kufa, al-Husayn b. Isma‘il al-Mahamili (d. 330/942), was described as the most knowledgeable person in hadith of his time and was famous for his amali.45 Abu al-‘Abbas al-Asamm was equally well known for his dictation sessions.

Not only did hadith transmission and collection continue unabated after the sahih movement, scholars continued to identify hadiths that they felt merited the title of sahih and that al-Bukhari and Muslim should have included in their works. The great hadith scholar of Baghdad, Abu al-Hasan al-Daraqutni (d. 385/995) and the Maliki hadith master of the Hejaz, Abu Dharr al-Harawi (d. 430/1038), both wrote one-volume collections called ilzamat (addendums) of hadiths that they considered up to the standards of the Sahihayn. Al-Daraqutni’s student, al-Hakim al-Naysaburi (d. 405/1014), compiled a voluminous ilzamat work entitled al-Mustadrak (with approximately 8,800 hadiths) in which he sought, once and for all, to demonstrate to those opponents of the ahl al-hadith the multitude of authentic hadiths that remained outside the Sahihayn.46

By the mid 1000s, however, it was clear that the process of recording the hadiths in circulation – regardless of whether they were authentic or forgeries – was coming to an end. In the mid eleventh century, al-Hakim’s student al-Bayhaqi declared that all the hadiths that could reliably be attributed to the Prophet had been documented, and thus any previously unrecorded attributions to Muhammad should be considered de facto forgeries.47 In practice, in the 1100s we see that fewer and fewer hadith scholars were able to record hadiths with full isnads (even highly unreliable hadiths) back to the Prophet that had not already been written down in some earlier collection. Ibn al-Jawzi of Baghdad (d. 597/1201), for example, is the only person to have transmitted the admittedly unreliable hadith ‘Sweeping the mosque is the dowry for a heavenly beauty (kans al-masajid muhur hur al-‘in).’ The last hadith that I have seen recorded with a full isnad is found in the Tadwin fi akhbar Qazwin (Recording the History of the City of Qazvin) of ‘Abd al-Karim al-Rafi‘i (d. 623/1226): ‘Sanjar will be the last of the Persian kings; he will live eighty years and then die of hunger.’48 Even this report is undoubtedly forged. By the 1300s, not even the greatest hadith scholars of their day such as Shams al-Din al-Dhahabi (d. 748/1348) or Jamal al-Din al-Mizzi (d. 742/1341) would dare to claim that they were in possession of a hadith reliably said by the Prophet that had gone unnoticed until their time.

In the early period of the hadith tradition the importance of oral transmission, or ‘audition (sama‘)’, where the student either read the hadith to his teacher or vice versa, had been very practical. One had to hear hadiths through a chain of teachers (isnad) because the Arabic script was too ambiguous to assure the correct understanding of any written document. The practical emphasis on oral transmission – only accepting material if it came through a living isnad of transmitters – was equally applicable to whole books of hadiths. The transmission of a book required the same care and concern as the transmission of an individual hadith, and collections like Sahih al-Bukhari? or Malik’s Muwatta’ were transmitted from teacher to student in the same manner as hadiths.

For hadith scholars, any referral to a hadith collection was contingent on hearing it from a chain of transmitters back to the author. A book could not simply be taken off the shelf and used. Like a single report, only a student copying a text in the presence of his teacher could protect against the vagaries and errors of transmission. Abu Bakr al-Qati‘i (d. 368/979), who was the principal transmitter of Ibn Hanbal’s Musnad, was severely criticized for transmitting one of Ibn Hanbal’s books from a copy which he had not heard directly from his teacher, Ibn Hanbal’s son. Although al-Qati‘i had in fact heard this book from his teacher previously, the copy he had used was destroyed in a flood, leaving him with only the other non-sama‘ copy. This case demonstrates the sensitivity of hadith scholars to the question of oral transmission. Even a respected scholar who had actually heard a book from his teacher could be criticized for relying on another copy if he had not read that copy in the presence of his teacher (since he would not have been able to make any corrections to it). The scholar who transmitted the Musnad from al-Qati‘i, Ibn al-Mudhhib (d. 444/1052– 3), was also accused of lax transmission practices. Specifically, he did not have sama‘ for certain sections of the Musnad. Later scholars thus explained that, because of this, ‘material with unreliable texts (matn) and isnads entered into the Musnad.’49 In the ninth, tenth, and eleventh centuries the isnad to the book was thus as important as the isnads contained within the book for authenticating its hadiths. Oral transmission was the key to maintaining these isnads.

In the 1000s, however, the fact that hadith collections such as the Six Books had become so well known and widely transmitted meant that scholars could relax the practical strictures of oral transmission. Sahih al-Bukhari was sufficiently widespread that if alterations were made to any one copy of the book there existed enough other transmissions of the book to identify this error. Although devout hadith scholars would maintain into the thirteenth century that one could not simply pick up a book of hadith and read it without having heard it from a transmitter via an isnad, Sunni scholars not specializing in hadith found this unnecessarily cumbersome. By the mid 1000s revered Sunni theologians and jurists like Abu Hamid al-Ghazali (d. 505/1111) and his teacher al-Juwayni (d. 478/1085) had declared that if one found a well-copied text of al-Bukhari’s Sahih one could read and use it without an isnad to the book.50

Even among scholars focused narrowly on the study of hadith, in the 1000s the practice of ijaza (permission for transmission) began to supersede sama‘ as the medium of the isnad. Ijaza for transmission meant that instead of reading an entire hadith collection in the presence of an authorized transmitter, a student might only read part of it and receive ‘permission’ from the teacher to transmit the rest. Although it was a less rigorous form of authentication, ijaza still provided scholars with isnads for books. Although this practice had existed in some forms even in the ninth century, by the mid 1000s it had become very common. Al-Hakim al-Naysaburi, author of the massive Mustadrak, thus gave a group of students an ijaza to transmit his works provided they could secure well-written copies of them.51

Of course, if you could get an ijaza for a book you had not actually read in the presence of a teacher, you could get ijazas for any number of books that the teacher was able to transmit. This led to the practice of acquiring a ‘general ijaza (ijaza ‘amma)’ for all the books a teacher had. In the 1000s many scholars also accepted the practice of getting ijazas from teachers one had not actually met at all through writing letters. This ‘ijaza for the non-present person (ijazat al-ma‘dum)’ meant that scholars could acquire ijazas for their infant children or even for children not yet born!

This ijaza for transmission (ijazat al-riwaya) should not be mistaken for another, much less easily attained form of ijaza in Islamic civilization, ‘the ijaza of knowledge (ijazat al-diraya).’ The ijaza of transmission served only to preserve the tradition of the isnad, while the ijaza of knowledge showed that a teacher acknowledged that a student had mastered a text and was able to teach its contents to others.

It is evident from these developments that by the late eleventh century the transmission of hadiths and books via a living isnad possessed little practical value. Why then did it continue? Simply put, the foundational principle of the Islamic tradition, that authority comes through a connection to God and His Prophet, still dominated Muslim scholarly culture. The isnad was that chain that connected a scholar to the Prophet and allowed him to act as an authoritative interpreter of Islam. Hearing a hadith or a book of hadiths by an isnad, even if by ijaza, breathed a soul into otherwise lifeless pages and rendered the book legally compelling. One Arabic poem describes someone reading a book without receiving it from a teacher as ‘someone trying to light a lamp with no oil.’52 The Andalusian scholar Ibn Khayr al-Ishbili (d. 575/1179) thus stated that no one could introduce a statement with the formula ‘the Prophet said…’ without possessing some personal chain of transmission, even if by ijaza, back to the Prophet for that report.53

The isnad conveyed authority in Muslim scholarly culture, and it is no coincidence that acquiring and possessing isnads was one of the means by which the Muslim scholarly elite could distinguish themselves from the laity. One of the reasons that Ibn Khayr al-Ishbili gave for requiring some form of isnad for quoting the Prophet was the phenomenon of uneducated simpletons preaching in mosques instead of qualified scholars. Receiving isnads for books and hadiths was the equivalent of being ordained into the priesthood, and it is no surprise that even today at the Islamic Institute in Kerala, India, the graduation ceremony for Muslim scholars involves the rector of the school reading them his isnad for a hadith that involves the transmitters, all the way back to the Prophet, investing the student to whom they recited the hadith with the turban of a scholar.

Perhaps the last large hadith book to include full isnads for every hadith it included was the Ahadith al-mukhtara (Selected Hadiths) of Diya’ al-Din al-Maqdisi (d. 643/1245). But even this book did not include previously unrecorded hadiths. The author’s isnads for his hadiths consist of his isnads to earlier hadith collections, which then continue from the author of those collections back to the Prophet. After the 1200s, hadith scholars would cultivate their own full-length isnads back to the Prophet in small booklets produced only for the pietistic purpose of linking themselves to his blessings and imitating the great hadith scholars of yore. As Muhyi al-Din al-Nawawi described it, collecting isnads back to the Prophet is an act of ‘preserving the isnad, which is one of the unique features of the Muslim community.’54 The famous hadith scholar of Cairo, Zayn al-Din al-‘Iraqi (d. 806/1404), thus conducted occasional amali sessions in an effort to imitate the practice of earlier hadith scholars. In the twentieth century, the Moroccan hadith scholar Ahmad al-Ghumari (d. 1960) recited hadiths with full isnads back to the Prophet in dictation sessions in Cairo’s al-Husayn Mosque. Today, the practice of transmitting hadiths is carried out by hearing hadiths known as musalsalat, or hadiths always transmitted in a certain context. The first hadith a student hears from his teacher is known as the hadith al-musalsal bi’l-awwaliyya, ‘the hadith always transmitted first’: ‘God the Most Merciful is merciful towards those who act with mercy – be merciful on the earth and He that is in the heavens will be merciful with you’ (see Chapter 1).

Historically, transmitting hadiths via full isnads back to the Prophet carried another advantage as well. Not only did the chain connect one to Muhammad himself, it also linked one to all the great scholars of the past through whom the isnad passed. The staunchly orthodox thirteenth-century Sufi ‘Umar al-Suhrawardi (d. 632/1234) began most of the chapters of his popular manual on Sufism, ‘Awarif al-ma‘arif, with hadiths that reached all the way back to the Prophet through major figures in the Sufi tradition, such as Abu al-Qasim al-Qushayri (d. 465/1072) and Abu Nu‘aym al-Isbahani.55 These scholars had recorded their hadiths in book-form, but the religious capital gained by providing living isnads for hadiths transmitted through them proved more compelling to al-Suhrawardi than simply citing their books.

Isnads thus linked scholars to the great figures who had preceded them in Islamic civilization and allowed one to speak with their voices as well as that of the Prophet. As the great Sufi of the sixteenth century, al-Sha‘rani (d. 1565 CE) said, someone with an isnad ‘is like a link in the chain, whenever he moves on any matter the whole chain, up to our master the Messenger of God, moves with him.’56

After the late tenth and eleventh centuries CE the primary purpose of the isnad was to provide a connection to the Prophet’s authority and establish a person as part of the Muslim scholarly class. As a result, one’s proximity to the Prophet in the isnad and access to hadiths that other scholars lacked served as marks of precedence in the scholarly community. Like the importance of oral transmission (sama‘), the notion of a short or ‘elevated (‘ali)’isnad began as a very practical concern for hadith authenticity: the fewer the links in the isnad to the Prophet, the fewer opportunities for error in transmission to occur. Hence we find even an early collector like Ibn Abi Shayba (d. 235/849) exhorting scholars that ‘seeking elevated isnads is part of religion.’57

By the mid 900s CE, however, seeking elevated isnads had become a goal in its own right. In a society where connection to the Prophet was the source of both authority and blessing, the proximity of that connection was very valuable. As one early hadith scholar phrased it, ‘A close isnad is closeness to God.’58 As in any society, Muslim religious scholars and pious individuals established a system of honors and valuable items that individuals could earn or attain; like educational degrees, Muslim scholars sought out shorter and shorter isnads, rarer and rarer hadiths, as a way to gain precedence, fame, and respect in their religious culture. Like coin collectors fretting over acquiring rarities, Muslims flocked to those scholars lucky enough to hear old hadith transmitters as young children, or who had heard a rare hadith from a certain transmitter from a faraway land. Such people could offer young Muslim scholars, eager to earn their place among the scholarly elite or merely to feel especially connected to their Prophet, a chance at excellence.

Of course, in none of these cases did the authenticity of the hadith in question actually matter – hadith scholars could distinguish themselves by their short isnads and their rare hadiths regardless of whether or not these isnads were reliable or the rare hadiths were baseless. To return to the analogy of coin collecting, it is the rarity of the coin and its condition (analogous to the elevation of an isnad) not the original value of the coin (or the authenticity of the hadith) which matter to the collector.

Perhaps the most prominent example of a hadith scholar who prioritized elevated isnads and rare hadiths far above authenticity was al-Tabarani (d. 360/971), who began hearing hadiths from teachers at the age of thirteen and died at the age of one hundred. Of his many hadith collections, his three mu‘jams (see below), one large, one medium, and one small, are testimonies to his priorities in hadith study. In the small and medium collections, al-Tabarani follows each narration with a brief discussion of how rare that narration is.

Al-Tabarani’s isnads border on the impossibly short. While ninth-century scholars like al-Bukhari generally narrated by isnads of four, five, six, or seven transmitters to the Prophet (and in al-Bukhari’s case, twenty-eight instances where he narrated by only three), one hundred years later al-Tabarani still regularly narrated hadiths with four-person isnads. In one case we find him narrating a hadith via only three people: Ja‘far b. Hamid al-Ansari  his grandfather ‘Umar b. Aban

his grandfather ‘Umar b. Aban  the Companion Anas b. Malik, who showed him how to perform ablutions like the Prophet!

the Companion Anas b. Malik, who showed him how to perform ablutions like the Prophet!