Arabic and English textbooks introducing Islamic methods of hadith criticism begin with presenting the complex technical vocabulary (mustalahat) of hadith critics as it was formalized after the thirteenth century. These books assume that by learning this set of terms students will understand how hadith criticism operated in the early Islamic period when scholars like al-Bukhari and Muslim were compiling their Sahihs. In reality, however, the critical methods of early Muslim hadith scholars were diametrically opposed to this later, rigid description. Theirs was an intuitive and commonsense way of trying to determine whether a report could be reliably attributed to a source or not – a method not unlike those employed by modern investigative reporters. To set the stage for our study of how Muslims tried to sift reliable from unreliable ‘reports’ from the Prophet, let us imagine a journalist working for a newspaper today.

If our reporter tells her editor that she has a major story about a senior political figure, the editor will ask her two questions: who is your source, and is your source corroborated? How could our reporter reply? She knows that certain sources are reliable for certain information. If the president’s spokesperson announces that the president will make a visit to England, there is no need to double-check this information. Imagine, however, that the reporter has found a source who gives her rare and valuable information about an important issue but whose reliability she as yet has no reason to trust. Our reporter is not going to stake her journalistic reputation on this one tip, but how does she determine the accuracy of her source’s information?

Imagine that this source tells her that there has just been an earthquake in China. Our reporter would call her contacts in China to confirm. If these contacts tell her that indeed a quake had occurred, the source has been proven correct. If no one she spoke to had noticed anything, the source’s story would be uncorroborated and our reporter would conclude that the source was unreliable. Suppose that next the source tells our reporter valuable information about the condition of the country’s economy. Again, our reporter proceeds cautiously, so she conducts thorough research and finds that the source’s information was correct. The source provides tips on a few more stories, and after checking out the information, our reporter finds that these stories are true as well. Eventually our reporter concludes that this source is reliable, and if the source provides a tip on a hot story in the future, the reporter will feel comfortable writing her story based on the source’s testimony alone.

Reporters understand that the reliability of a source is based upon the accuracy of the information they provide. The best way to confirm the accuracy of a source is to check with other sources that have access to the same information and see if they agree. Corroboration ‘is what turns a tip into a story.’1

These two pillars of modern journalism, the reliability of a source and determining the reliability of a source or story through corroboration, are familiar to us all in our daily lives. We all know people who pass on information reliably and others who tend to forget, lie, or exaggerate. We all instinctively seek out corroboration and know when it matters and when it does not. If a student is absent for a day of class in university and hears from a classmate that the professor has changed the date of the final exam, he or she will not be content to take the word of just one classmate; the student will ask other students who were also in that class. If no other students heard the professor make that announcement, he or she will have serious doubts about the information.

Another fact is equally evident to us in our daily lives: the contents of reports we hear have a strong influence on our view of their reliability and our confidence in their transmitters. If our reporter met a source who swore that he had seen a herd of flying elephants downtown, she would probably both disbelieve him and consider him unreliable from that point on. There are generally accepted standards of what is possible and impossible. Furthermore, we all have a sense of what is important information and what is not, and we treat this information accordingly. If our reporter hears a rumor that the president is about to announce a major change in the government’s economic policy, she will want to verify this information before writing her story. If she hears that the president has changed his favorite dessert from ice cream to angel-food cake, she will probably be content to cite this information as is. We must remember, however, that such notions of what is possible or impossible, important or unimportant, are culturally determined, and as such they may differ with time and place.

While modern reporters are charged with determining the veracity of stories about what is happening in the world today on the basis of contemporary sources, the architects of the Islamic hadith tradition were faced with a more daunting task: they had to establish a system of distinguishing between true and false stories about a man who had lived over a century earlier and whose revered status cast a commanding shadow over the entire Islamic tradition.

In this chapter we will discuss the origins, mechanics, and development of Sunni hadith criticism. We will divide its history into two periods: early hadith criticism, roughly 720–1000 CE, and later hadith criticism, from roughly 1000 CE to today. As in the previous chapter, notions of ‘authenticity’ and ‘forgery’ mentioned here refer to the judgment of Muslim scholars of hadith and not necessarily to that of modern Western historians.

The Prophet Muhammad is the single most dominant figure in the Islamic religious and legal tradition. From the time of his emigration to Medina to debates over Islam today, to disobey directly his established teachings has been to place oneself outside the Muslim community. Because the Prophet possessed such eminent authority, early Muslims looked to his legacy to support or legitimize their different schools of thought, beliefs, or political agendas. It seems that even during the Prophet’s own lifetime he understood that people could misrepresent him. In one report, a man claiming to be the Prophet’s representative established himself as the mayor of a small town in Arabia until the Prophet uncovered his hoax and punished him.2

The first crisis to afflict the Muslim community after the Prophet’s death – the question of who would succeed him as religious and political leader – revolved around competing claims about the Prophet’s words. The supporters of ‘Ali b. Abi Talib argued that the Prophet had announced him as his successor, while those who affirmed the successive caliphates of Abu Bakr, ‘Umar, and ‘Uthman did not. In this and many other Islamic sectarian and political disagreements, all sides agreed on what the Prophet had said but disagreed on its implications. Both Sunnis and Shiites, for example, agreed that the Prophet had said that ‘Ali was to him what Aaron was to Moses, but they disagreed on whether that meant that ‘Ali should succeed the Prophet politically.

Actually forging reports about the Prophet also quickly became a problem. When civil war broke out openly between ‘Ali, then the fourth caliph to succeed the Prophet, and the then governor of Syria and future founder of the Umayyad dynasty, Mu‘awiya b. Abi Sufyan, both sides waged a propaganda war using the Prophet’s words as ammunition. ‘Ali’s supporters falsely claimed that Muhammad had said, ‘If you see Mu‘awiya ascend my pulpit, then kill him,’ while Mu‘awiya’s side countered by forging hadiths such as ‘It is as if Mu‘awiya were sent as a prophet because of his forbearance and his having been entrusted with God’s word’ (Mu‘awiya had served as one of the Prophet’s scribes).3 There are even reports from the early historian al-Mada’ini (d. 225/840) that Mu‘awiya encouraged the systematic forging and circulation of hadiths affirming the virtues of the other caliphs and Companions at ‘Ali’s expense.4

In light of how quickly the Prophet’s legacy became a tool to be manipulated by vying parties among Muslims, we should not be surprised at the veritable slogan of Muslim hadith criticism. It is the most widely transmitted hadith in all of Islam, with Muslim scholars counting between sixty and a hundred Companions transmitting it from the Prophet: ‘Whoever lies about me intentionally, let him prepare for himself a seat in Hellfire.’

During the lifetime of leading Companions like ‘Umar b. al-Khattab, ‘Abdallah b. Mas‘ud, or Anas b. Malik, many of whom had been with the Prophet since his early days in Mecca, it was difficult to attribute something untrue to the Prophet without a senior Companion noticing. In fact, there are many reports documenting the Companions’ vigilance against misrepresentations of the Prophet’s legacy. ‘Ali is quoted as requiring an oath from any Companion who told him a hadith from the Prophet that he himself had not heard.5 When the Companion Abu Musa al-Ash‘ari told ‘Umar that the Prophet had said that if you knocked on someone’s door three times and they did not answer you should depart, ‘Umar demanded that he find another Companion to corroborate the report.6

On a number of occasions after the Prophet’s death, his wife Aisha objected to hadiths that other Companions related. She rejected ‘Abdallah b. ‘Umar’s statement that the Prophet warned mourners that a dead relative would be punished for his family’s excessive mourning over him because she believed that it violated the Quranic principle that ‘No bearer of burdens bears the burdens of another’ (Quran 53:38).7 In another famous report, Aisha upbraided a Companion who said that the Prophet told the Muslims that their prayer is invalidated if a woman, a black dog, or a donkey passes in front of them. ‘You have compared us [women] to donkeys and dogs!’ she retorted. ‘By God I saw the Prophet praying with me lying on the bed between him and the direction of prayer ...!’8 Abu Hurayra’s extensive efforts at hadith collection in particular drew the ire and concern of some leading Companions. There is one report that ‘Umar b. al-Khattab told him, ‘Indeed, I say let the Prophet’s words alone or indeed I’ll send you back to the lands of [your tribe] Daws!’9

Hadith forgery emerged as a blatant problem when the generation of Muslims who had known the Prophet well died off. With the death of the last major Companion, Anas b. Malik, in Basra in 93/711 (the last Companion to die was Abu al-Tufayl ‘Amir b. Wathila, who died between 100/718 and 110/728) lies about the Prophet quickly multiplied. It is especially in the generation of the Successors that we begin seeing notebooks (sahifas) of hadiths, many supposedly narrated from Anas b. Malik, filled with forged hadiths of a highly partisan or controversial nature.10

From that point onward the forgery of hadiths would be a consistent problem in Islamic civilization. The heyday of hadith forgery was the first four hundred years of Islamic history, when major hadith collections were still being compiled. As we discussed in the last chapter, by the late 1100s any hadith that entered circulation that had not already been recorded in some existing book was automatically deemed a forgery. In the great urban centers of Mamluk Cairo or Ottoman Istanbul in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the masses might mistakenly think that a popular saying such as ‘The Muslim community is sinful but its Lord is most forgiving (umma mudhniba wa rabb ghafur)’ was said by the Prophet, but in general hadith forgery had run its course.11

Political and sectarian conflicts were a major engine for hadith forgery. All the major political conflicts in classical Islamic history were accompanied by hadiths forged for propagandistic purposes. The Prophet’s access to knowledge of the future provided endless possibilities in this realm. In one hadith, the Prophet supposedly tells his uncle ‘Abbas, progenitor of the Abbasid dynasty, to look at the stars. The Prophet foretells, ‘From your descendents a number like the number of the Pleiades will rule the Muslim community.’12 In one forged pro-Shiite hadith, the Prophet predicts that ‘al-Husayn will be killed sixty years after my emigration to Medina,’ referring to the Umayyad caliph’s massacre of the Prophet’s grandson at Karbala in 61/680.13 We have seen already that even in the eleventh century, an opponent of the Seljuq Turkish sultan Sanjar forged a hadith in which the Prophet predicted that, ‘Sanjar will be the last of the non-Arab kings; he will live eighty years and then die of hunger.’14 In fact, in the early 1990s one Arab scholar claimed that he had found an old manuscript with a hadith predicting that ‘A leader whose name is derived from the word “tree” (Bush, perhaps?) will invade and liberate a small hill fort (in Arabic, ‘Kuwait’).’15

Many hadiths were also forged in legal and theological debates. Here the Sunni/Shiite schism once again has certainly produced the largest numbers of propagandistic hadiths. Less well-known conflicts have also yielded countless forgeries. In the first half of the ninth century, when the Abbasid caliphate was trying to impose its rationalist beliefs on Sunni scholars like Ibn Hanbal by torturing or imprisoning anyone who would not uphold the belief that the Quran was God’s created word and not an eternal part of His essence, pro-Sunni hadiths conveniently appeared in which the Prophet said, ‘The Quran is eternal, uncreated, and he who says otherwise is a disbeliever.’ In eighth-century debates over whether Muslims could wear pants as opposed to robes, a hadith appeared in which the Prophet said, ‘O people, take pants as clothing, for indeed they are the most modest of clothes, especially for your women when they leave the house.’16 As legal schools solidified and competed with one another, forged hadiths appeared with statements such as ‘There will be in my community a man named Abu Hanifa, and he will be its lamp ... and there will be in my community a man named Muhammad b. Idris [al-Shafi‘i] whose strife is more harmful than that of Satan.’17

Hadiths were forged to give voice to all sorts of chauvinisms. Some were virulently racist, such as a forged hadith saying ‘The black African, when he eats his fill he fornicates, and when he gets hungry he steals (al-zanji idha shaba‘a zana wa idha ja‘a saraqa).’18 Others voiced civic pride, such as the hadith ‘ [The city of] Askalon [near modern-day Gaza] is one of the two Brides, from there God will resurrect people on the Day of Judgment (‘Asqalan ihda al-‘arusayn ...)’ or a whole Forty Hadith collection that one Ahmad b. Muhammad al-Marwazi (d. 323/934–5) forged about the virtues of the Iranian city of Qazvin.19

Another major source of forged hadiths was the popular storytellers (qass, pl. qussas) who entertained crowds on the streets of metropolises like Baghdad. These storytellers would attribute Jewish, Christian, or ancient Persian lore to the Prophet. In one fantastic story, someone named Ishaq b. Bishr al-Kahili from Kufa told of the Prophet meeting an old man in the desert. The man claimed to be named Hama, the great-grandson of Satan, and to have been alive since the days of Cain and Abel. In an account resembling a Rolling Stones song, he proceeds to tell Muhammad how he had met all the great prophets, from Noah to Jacob and Joseph. Moses had taught him the Torah, and Jesus had told him to convey his greetings to Muhammad, the messenger to come.20

A surprisingly large number of hadiths were forged and circulated by pious Muslims in an effort to motivate those around them both religiously and morally. One Abu ‘Isma was asked by his contemporaries to explain how the hadiths he narrated from ‘Ikrima, the disciple of the Companion Ibn ‘Abbas, about the virtues of reading different chapters of the Quran, were not narrated by any of ‘Ikrima’s other students. He replied that he had seen the people becoming obsessed with the legal scholarship of Abu Hanifa and the Sira of Ibn Ishaq. He had forged these hadiths to try and steer people once again towards the Quran.21

Many of those who forged hadiths for these pious purposes were themselves revered saintly figures. The famous hadith critic Yahya b. Sa‘id al-Qattan (d. 198/813) once said, ‘I have not witnessed lying [about the Prophet] in anyone more than I have seen it in those known for asceticism and piety.’22 A venerated saint of Baghdad, Ghulam Khalil, was so beloved that on the day he died in 275/888–9 the markets of the city shut down. Yet when he was questioned about some dubious hadiths he narrated concerning righteous behavior, Ghulam Khalil replied, ‘We forged these so that we could soften and improve the hearts of the populace.’23

Certainly pious figures such as Ghulam Khalil or the scholars of religious law understood the enormity of the sin of lying about their Prophet. How could they have contradicted their own mission of preserving his authentic teachings by doing so? Pious figures sometimes replied that the Prophet had forbidden the Muslims to lie about him, whereas they were lying for him. In the case of those early jurists who forged legal hadiths to support their school of law, it seems that they saw no contradiction between their actions and their commitment to preserving the Prophet’s teachings. After all, as one famous hadith put it, ‘The scholars are the inheritors of the prophets (al-‘ulama’ warathat al-anbiya’).’ It was the scholars who interpreted the message of Islam as it faced new challenges and circumstances. Phrasing their conclusions about proper acts or beliefs in the formula of ‘the Prophet said ...’ was simply neatly packaging their authority as Muhammad’s representatives. As one early jurist explained, ‘When we arrived at an opinion through reasoning we made it into a hadith.’24 Hadith critics, of course, found such excuses reprehensible.25

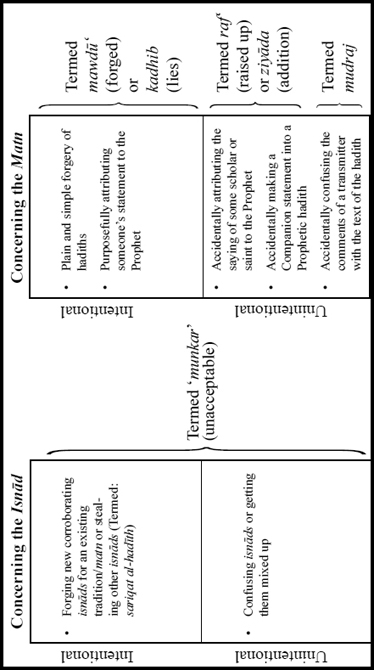

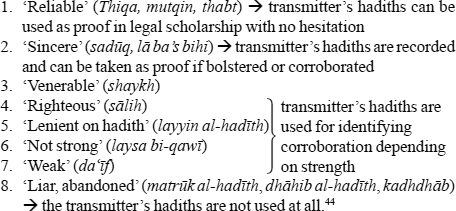

Not all forgery of hadiths was a malicious act. Early transmitters sometimes confused the opinions or statements of Companions with Prophetic hadiths, such as Aisha’s statement: ‘Ward off capital punishment from the Muslims as much as possible, and if there is some way out of it then let the person go, for it is better for the judge to err in mercy than in severity,’ which is sometimes attributed to the Prophet. Sometimes the comments of one of the hadith’s transmitters could be accidentally written as part of the hadith, a phenomenon that Muslim critics called idraj (interpolation).

Often the words of scholars or saintly figures or simply popular sayings could be accidentally elevated to the status of Prophetic hadiths. The saying ‘The love of the earthly life is the start of every sin (hubb al-dunya ra’s kull khati’a)’ was generally attributed to Jesus until it became confused with a Prophetic hadith.26 A legal principle used by Muslim jurists, ‘Necessities render the forbidden permissible (al-daruriyyat tubihu al-mahzurat)’ was also accidentally attributed to Muhammad.27 In the ninth century a hadith appeared saying ‘Beware of flowers growing in manure, namely a beautiful woman from a bad family (iyyakum wa khadra’ al-diman...).’ In this period another supposed hadith surfaced that ‘Whoever says something then sneezes, what he says is true (man haddatha hadithan fa-‘atasa ‘indahu fa-huwa haqq).’ Neither report had any basis in Prophetic hadiths.28

Hadith forgery was not limited to inventing Prophetic sayings or attributing existing maxims to Muhammad. In light of the importance of the isnad to accessing authority in the Islamic tradition, isnad forgery was arguably more common than matn forgery. Equipping existing hadiths with one’s own isnads or constructing entirely new chains of transmission was known as ‘stealing hadiths (sariqat al-hadith)’ or ‘rigging isnads (tarkib al-asanid).’

Today no one would look askance at someone who cited a hadith without mentioning its isnad. In the early Islamic period, however, ahl al-hadith scholars or those who debated them could not cite a hadith without providing their own isnad for the report. A scholar who had heard about a hadith without a firm isnad or from a transmitter considered unreliable by the ahl al-hadith critics could thus not credibly present his hadith in any discussion. Forging a new isnad offered a solution. ‘Amr b. ‘Ubayd (d. 144/761), who belonged to the Muslim rationalist camp known as the Mu‘tazilites, whom the ahl alhadith considered their mortal enemies, was thus attacked for lying in his narration of the hadith ‘He who carries weapons against us [Muslims] is not one of us (man hamala ‘alayna al-silah fa-laysa minna)’ from his teacher al-Hasan al-Basri, from the Prophet. This hadith was well known as authentic among the ahl al-hadith. The problem was that al-Hasan had not actually transmitted this from the Prophet. ‘Amr b. ‘Ubayd had heard of the report somewhere else and then tried to use it to support the Mu‘tazilite position that committing grave sins assured Muslims a place in hell. But he did not have his own isnad for it. So he manufactured one from his teacher al-Hasan so that he could use it in debates.29

The second major motivation to forge an isnad for an existing hadith was to bolster its reliability by increasing evidence of its transmission. According to the great hadith critic of Baghdad, al-Daraqutni (d. 385/995), a whole notebook of hadiths praising human reason (‘aql) was forged by Maysara b. ‘Abd Rabbihi. This book was then taken by Dawud al-Muhabbir, who equipped the reports with his own new isnads. One ‘Abd al-‘Aziz b. Abi Raja’ then stole these hadiths and provided them a new set of isnads. Sulayman b. ‘Isa al-Sinjari then did the same. A person who came across the hadiths in this book therefore could find four different sets of isnads leading to four different scholars for hadiths that were in fact total forgeries!30

Figure 3.0 Types of Errors and Forgery in Hadiths

Especially in the tenth century and afterwards, when rare and elevated isnads assumed a particular value among hadith collectors, disingenuous scholars could forge isnads with these characteristics. We already saw the hadith that al-Tabarani (d. 360/971) narrated via the impossibly short isnad of three people to the Prophet: Ja‘far b. Hamid al-Ansari  ‘Umar b. Aban

‘Umar b. Aban  Anas b. Malik

Anas b. Malik  the Prophet. The fact that al-Tabarani was the only hadith scholar to narrate from the transmitter Ja‘far b. Hamid strongly suggests that this Ja‘far might have been a purveyor of forged elevated isnads, which a collector like al-Tabarani would have found irresistible.

the Prophet. The fact that al-Tabarani was the only hadith scholar to narrate from the transmitter Ja‘far b. Hamid strongly suggests that this Ja‘far might have been a purveyor of forged elevated isnads, which a collector like al-Tabarani would have found irresistible.

As false attributions to the Prophet multiplied in the late seventh century, how were those Muslims who sought to preserve Muhammad’s authentic legacy to distinguish between true and forged hadiths? While the ahl al-ra’y scholars in Iraqi cities like Kufa attempted to rise above the flood of forged hadiths by depending on the Quran, well-established hadiths, and their own legal reasoning, the school that would give birth to the Sunni tradition, the ahl al-hadith, evolved the three-tiered approach to determining the authenticity of a hadith. The first tier was demanding a source (isnad) for the report, the second evaluating the reliability of that source, and the third seeking corroboration for the hadith.

The processes of this three-tiered critical method did not emerge fully until the mid eighth century with critics like Malik b. Anas and Shu‘ba b. al-Hajjaj. Certainly, Successors like al-Zuhri and even Companions had examined critically material they heard attributed to the Prophet. Moreover, the critical opinions of Successors would inform later hadith critics. A formalized system of requiring isnads and investigating them according to agreed conventions and through a set of technical terms, however, did not appear until the time of Malik.

The isnad, or ‘support,’ was the essential building-block of the hadith critical method. So essential would the isnad be to the Sunni science of hadith criticism that it became the veritable symbol of the ‘cult of authenticity’ that is Sunni Islam. One of the most oft-repeated slogans among hadith critics comes from the famous scholar Ibn al-Mubarak (d. 181/797), who said, ‘The isnad is part of religion, if not for the isnad, whoever wanted could say whatever they wanted. But if you ask them, “Who told you this?” they cannot reply.’ The great jurist al-Shafi‘i provided a similarly famous declaration, ‘The person who seeks knowledge without an isnad, not asking “where is this from?” indeed, he is like a person gathering wood at night. He carries on his back a bundle of wood when there may be a viper in it that could bite him.’ Sunnis thus understood the isnad as the prime means of defending the true teachings of the Prophet against heretics as well as protection from subtle deviations that might slip into Muslims’ beliefs and practice.31

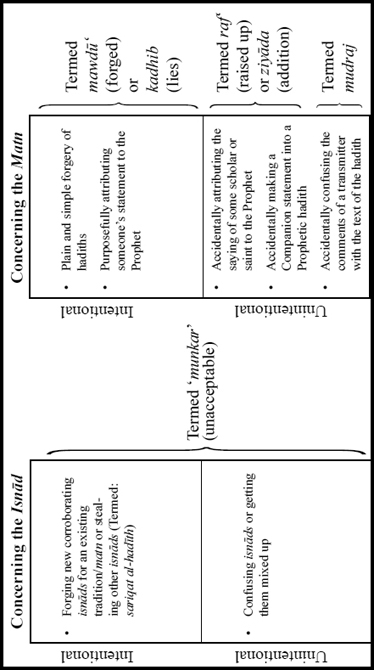

Figure 3.1 Generations of Sunni Hadith Critics

The origins of the isnad were as commonsense as its function, beginning with the rise of hadith forgery. As the Successor Muhammad b. Sirin (d. 110/729), a leading student of the Companion Anas b. Malik, explained:

In the early period no one would ask about the isnad. But when the Strife [most probably the Second Civil War, 680–692CE] began they would say ‘Name for us your sources’ so that the People of the Sunna (ahl al-sunna) could be looked at and their hadiths accepted, and the People of Heresy (ahl al-bid‘a) could be looked at and their hadiths ignored.32

In the milieu of the early Islamic period, simply demanding an isnad for reports attributed to the Prophet was an excellent first line of defense against inauthentic material entering Muslim discourse. We can imagine the newly Muslim inhabitants of Kufa, still clinging to Christian or Zoroastrian lore, or even Bedouins eager to insinuate tribal Arab values into Islam, ascribing a saying to the Prophet as evidence for their ideas. If they provided no isnad at all, the reports would not enter the musnad collections of scholars like Abu Dawud al-Tayalisi. The formative critic Shu‘ba b. al-Hajjaj (d. 160/776) is quoted as saying, ‘All religious knowledge (‘ilm) which does not feature “he narrated to me” or “he reported to me”[the components of the isnad] is vinegar and sprouts.’33

On their own, however, isnads could not deter a determined forger. As we saw with the hadiths on human reason, an isnad could be made up or inauthentic material simply equipped with one and then circulated. Moreover, merely requiring someone to provide a source for a hadith they cited did not tell you if that source was reliable. The second tier of criticism thus involved identifying the individuals who constituted isnads, evaluating their reliability, and then determining if there were any risks that someone unreliable might also have played some part in transmitting the report.

A hadith transmitter was evaluated according to two criteria. First, his or her character, correct belief, and level of piety were scrutinized in order to determine if he or she was ‘upright (‘adl).’ Second, and much more importantly, the transmitter’s corpus of reports and narration practices were evaluated to decide if he or she was ‘accurate (dabit).’

Hadith transmitter criticism (known as al-jarh wa al-ta‘dil, ‘impugning and approving’) and isnad evaluation began in full with the first generation of renowned hadith critics, that of Shu‘ba b. al-Hajjaj, Malik b. Anas, Sufyan al-Thawri, al-Layth b. Sa‘d, and Sufyan b. ‘Uyayna, who flourished in the mid to late eighth century in the cities of Basra, Kufa, Fustat (modern-day Cairo), Mecca, and Medina (see Figure 3.1). These scholars began the process of collecting people’s hadith narrations and examining both their bodies of material and their characters to determine if the material they purveyed could be trusted. Malik is the first scholar known to have used technical terms such as ‘thiqa (reliable)’ to describe these narrators, while Shu‘ba’s evaluations did not utilize any specialized vocabulary.34

The evaluations of this first great generation were studied and added to by their students, especially the two great Basran critics ‘Abd al-Rahman b. Mahdi (d. 198/814) and Yahya b. Sa‘id al-Qattan (d. 198/813). The later analyst Shams al-Din al-Dhahabi notes that ‘whoever they both criticize, by God, rarely do you find that criticism refuted [by others], and whoever they both agree on as trustworthy, he is accepted as proof.’35 The critical methods and opinions of Ibn Mahdi and al-Qattan passed on to their three most respected students, who can be seen as the beginning of the heyday of Sunni hadith criticism: Ibn Hanbal (d. 241/855) and his friend Yahya b. Ma‘in (d. 233/848) in Baghdad and ‘Ali b. al-Madini in Basra (d. 234/849). Their students refined hadith criticism into its most exact and lasting form: the ‘Two Shaykhs’ al-Bukhari and Muslim, the two senior critics of Rayy (modern Tehran), Abu Zur‘a al-Razi (d. 264/878) and his friend Abu Hatim al-Razi (d. 277/890), as well as influential younger critics of that generation such as al-Nasa’i (d. 303/916).

The 900s saw several generations of critics who reviewed and reassessed the judgments of these earlier scholars and also continued to evaluate those involved in the ongoing transmission of hadiths: Ibn Abi Hatim al-Razi (d. 327/938), Ibn ‘Adi (d. 365/975–6), Ibn Hibban al-Busti (d. 354/965), Abu al-Hasan al-Daraqutni (d. 385/995), and al-Hakim al-Naysaburi (d. 405/1014).

Although the apex and most active period of hadith transmitter criticism is usually considered to be the eighth to tenth centuries, subsequent generations of critics contributed to this science as well. Hadiths were still transmitted with full isnads into the early 1200s, so it was possible until that time for previously unrated hadiths to be in circulation among transmitters. Master hadith scholars like al-Khatib al-Baghdadi (d. 463/1071) and Ibn ‘Asakir (d. 571/1176) therefore continued to rate transmitters living in their times. Furthermore, they synthesized, reconciled, and reexamined existing opinions on earlier transmitters.

This reconsideration of earlier transmitters’ standing has, in fact, never really ended. If we look at al-Dhahabi’s list of the expert critics whose opinions should be heeded, we find that it continues until al-Dhahabi’s own time in the 1300s. One of the most commanding critics in the Sunni hadith tradition, ‘the Hadith Master (al-hafiz)’ Ibn Hajar al-‘Asqalani, died in 852/1449. Hadith transmitter criticism has continued until the modern day. This is possible because, as we shall see, determining if someone was reliable or not had little to do with any personal experience with their character, its flaws, or fine qualities. Ultimately, it was the analysis of the body of their transmissions for corroboration that determined their accuracy (dabt) and thus their station.

How would a hadith critic such as Shu‘ba, al-Bukhari, or Ibn ‘Adi actually evaluate a transmitter? First, it was essential to know who this transmitter was. If one was presented with a hadith transmitted from ‘someone,’ ‘Ahmad,’ or ‘a group of people in Medina,’ how could one evaluate the strength of its isnad? By the mid 800s it had become accepted convention among hadith critics that a person needed two well-known transmitters to identify him sufficiently, prove that he existed and narrate hadiths from him in order to qualify for rating. Otherwise, the transmitter would be dismissed as ‘unknown (majhul)’ and the report automatically considered unreliable.

Second, the critic would collect all the reports that the transmitter had narrated from various teachers and then analyze them for corroboration, a process known as ‘consideration (i‘tibar).’ As mentioned last chapter, musnads would be very useful for this task, but ultimately a critic would have to rely on a robust memory in order to recall all the different isnads in which the transmitter in question played some part. For every hadith that the transmitter narrated from a certain teacher, the critic asks ‘Did this teacher’s other students narrate this report too?’ If the critic finds that, for all the teachers that the transmitter narrates from, his fellow students corroborated him for a very high percentage of his hadiths, then he is considered to be reliable in his transmissions. When asked what kind of transmitters should be abandoned as unreliable, Shu‘ba explained:

Someone who narrates excessively from well-known transmitters what these well-known transmitters do not recognize, his hadiths are cast aside. And if he makes a lot of mistakes, his hadiths are cast aside. And if he is accused of forgery (kadhib), his hadiths are cast aside. And if he narrates a hadith that is agreed upon as an error, and he does not hold himself accountable for that and reject the report, his hadiths are cast aside.36

Muslim b. al-Hajjaj describes the telltale signs of a weak hadith transmitter as someone who, ‘when his narrations are compared with those of people known for preservation [of hadith] and uprightness of character, his narrations do not concur with their narrations, or do so only rarely. If the majority of his hadiths are like that then he is rejected and not used in hadith.’37

Early hadith critics understood very well that no one transmitter was immune from error. Below the level of master transmitters, Ibn Mahdi described a lesser type of narrator ‘who makes errors but most of his hadiths are sahih. This kind of person’s hadiths should not be abandoned, for if they were, all the people’s hadiths would disappear.’38

Finally, the critic would examine the transmitter’s character, religious beliefs, and piety in order to determine his ‘uprightness (‘adala).’ Although later legal theorists would establish very formal requirements for someone to be declared ‘upright,’ such as the requirement widely accepted by Sunnis after the 1200s that the transmitter be ‘Muslim, of age, of right mind, free of sinful behavior and defects in honor,’ early hadith critics were actually very flexible with determining uprightness.

This is most evident in the issue of transmitters who espoused beliefs that Sunnis considered heretical, such as Shiism, belonging to the Kharijite sect, or a belief in free will (qadar). Although al-Shafi‘i had declared that one could accept hadiths from transmitters regardless of their sectarian affiliations as long as they did not belong to certain Shiite sects that allowed lying, by the mid 900s scholars like Ibn Hibban had declared a consensus among Sunni hadith critics that one could accept hadiths from any heretical transmitter provided he was not an extremist and did not actively try to convert others to his beliefs. In theory, this meant that one could accept hadiths from Shiite transmitters as long as they did not engage in virulently anti-Sunni practices such as cursing Abu Bakr or ‘Umar or transmit hadiths that seemed to preach the Shiite message.

In truth, however, early hadith critics did not follow these strictures. As the eighteenth-century Yemeni hadith analyst Ibn al-Amir al-San‘ani (d. 1768) observed, later theorists had set up principles that did not apply to the realities of early hadith criticism. Al-Bukhari, the most revered of all hadith critics, narrated two hadiths in his famous Sahih through the Kharijite ‘Imran b. Hittan, who was so extreme in his beliefs that he wrote a poem praising the Kharijite who murdered the fourth caliph ‘Ali. In his Sahih, Muslim narrated the hadith that ‘Only a believer loves ‘Ali, and only a hypocrite hates him’ through the known Shiite transmitter ‘Adi b. Thabit. As we can see, the two uncontested masters of Sunni hadith criticism could narrate hadiths that they considered authentic through extremists and heretics who proselytized for their cause!

The explanation for this lies in the priorities of the early hadith critics. Simply put, if a transmitter consistently and accurately passed on hadiths he had heard from the previous generation, hadith critics had little interest in his beliefs or practice. Ibn Ma‘in described the Shiite transmitter ‘Abd al-Rahman b. Salih as ‘trustworthy, sincere, and Shiite, but who would rather fall from the sky than misrepresent half a word.’39 One major early hadith transmitter, Isma‘il b. ‘Ulayya (d. 193/809), became so shamefully intoxicated on one occasion that he had to be carried home on a donkey. Yet he was a reliable transmitter, so his hadiths were accepted.40 Although later theorists of the hadith tradition would talk of the two pillars of reliability as ‘uprightness (‘adala) and accuracy (dabt),’ al-San‘ani rightly pointed out that one should reorder them ‘accuracy and uprightness,’ since the former greatly outweighed the latter.41

Ultimately, Sunnis could not escape their dependency on the role of ‘non-Sunnis’ in hadith transmission. The early critic Ibn Sa‘d (d. 230/845) notes how one Khalid al-Qatwani was a staunch Shiite but that hadith scholars ‘wrote down his hadiths out of necessity.’42 Without such ‘heretics,’ critics knew that few hadiths would ever have been transmitted.

Guaranteeing the transmitter’s ‘uprightness (‘adala),’ however, did have an important function. Regardless of a transmitter’s accuracy, if they were known to have intentionally misrepresented the Prophet or forged a hadith then they could not be trusted. Sulayman b. Dawud al-Shadhakuni (d. 234/848–9), for example, was considered to have the most prodigious memory of hadiths in his time and one of the biggest hadith corpora. Yet he was known to have lied about hadiths and altered them to fit certain situations, so he was excluded from transmission. Al-Shadhakuni was so untrustworthy that when he awed a gathering by claiming that he knew a hadith from Rayy that Abu Zur‘a al-Razi did not know, people believed that he had just made it up on the spot to impress them.43

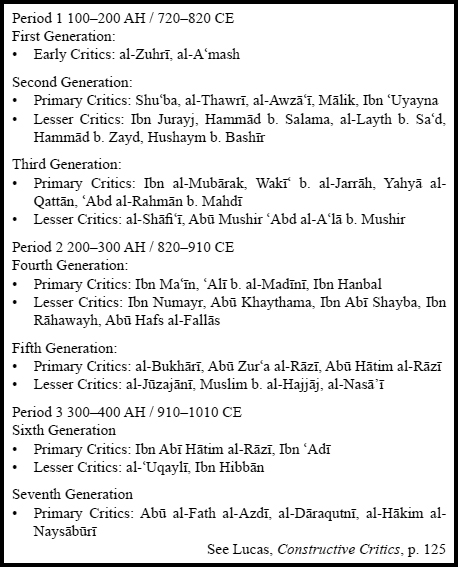

Although in the eighth and ninth centuries each hadith critic used slightly different and sometimes shifting terms to describe a transmitter’s level of reliability, by the early tenth century a conventional jargon had emerged. Ibn Abi Hatim al-Razi (d. 327/938) lists the levels as:

Hadith transmitter criticism often took place in discussion sessions among critics or with their students, but its results were set down by master critics in dictionaries of transmitter evaluation (kutub alrijal). Early works include the Tabaqat al-kubra (The Great Book of Generations) of Ibn Sa‘d (d. 230/845), the Ahwal al-rijal (Conditions of the Transmitters) of al-Juzajani (d. 259/873), the massive ‘Great History (al-Tarikh al-kabir)’ of al-Bukhari, and the Jarh wa al-ta‘dil of Ibn Abi Hatim al-Razi. Some books focused specifically on discussing transmitters whom the author felt were reliable; these included al-‘Ijli’s (d. 261/875) Tarikh al-thiqat and Ibn Hibban’s Kitab al-thiqat. Voluminous books were devoted to listing and discussing weak transmitters as well. The most important are the Kitab al-du‘afa’ al-kabir of al-Bukhari (now lost), the Kamil fi du‘afa’ al-rijal of Ibn ‘Adi and Ibn Hibban’s Kitab al-majruhin. Such works presented critics’ opinions of a transmitter along with a selection of the unacceptable narrations that they transmitted. Because they consistently evaluated the reliability of personalities they mention, local histories like al-Khatib’s History of Baghdad are also works of transmitter criticism.

In the period of consolidation and analysis from the 1300s to the 1600s, later critics amalgamated and digested these earlier works of hadith criticism. ‘Abd al-Ghani al-Maqdisi (d. 600/1203) wrote his al-Kamal fi ma‘rifat asma’ al-rijal (The Perfection in Knowing the Names of Transmitters), presenting earlier descriptions and evaluations of all the transmitters in the Six Books. Jamal al-Din al-Mizzi (d. 742/1341) added to this work and further analyzed the ratings of the transmitters within the Six Books in his Tahdhib al-kamal (The Refinement of Perfection), published today in thirty-five volumes. Ibn Hajar al-‘Asqalani produced an abridgement of this work with his own comments entitled Tahdhib al-tahdhib (The Refinement of the Refinement). Scholars like the Egyptian Ibn al-Mulaqqin (d. 804/1401) added the transmitters found in other hadith collections such as the Musnads of Ibn Hanbal and al-Shafi‘i as well as the Sahih of Ibn Khuzayma and the Mustadrak of al-Hakim to expanded versions of al-Mizzi’s book. The Hanafi scholar of Cairo, Badr al-Din al-‘Ayni (d. 855/1451), devoted a rijal work to the transmitters in al-Tahawi’s collections.

Other later analysts focused on the subject of weak transmitters. Shams al-Din al-Dhahabi wrote his masterful Mizan al-i‘tidal fi naqd al-rijal (The Fair Scale for Criticizing Transmitters), collecting all the information on any transmitter impugned by earlier figures. Ibn Hajar added his own comments in a revision of this work, Lisan al-mizan (The Pointer of the Scale).

As we saw in the last chapter, the isnads to hadith books could affect the reliability of hadiths in them, especially during the ninth and tenth centuries. Scholars like Ibn Nuqta of Baghdad (d. 629/1231) therefore wrote books of transmitter criticism addressing the people who conveyed books from their authors. Ibn Nuqta’s al-Taqyid fi ma‘rifat ruwat al-sunan wa al-masanid and Abu ‘Ala’ al-Fasi’s (d. 1770) addendum to that book are examples of this genre.

With the plethora of transmitter critics from the eighth century on, how was a later critic or analyst supposed to know whose opinion to take on the reliability of a narrator or a hadith? Ibn Ishaq (d. 150/767), for example, the author of the famous biography of the Prophet, was a very controversial figure. Malik, Ibn al-Qattan, Ibn Hanbal, and others considered him highly unreliable because he accepted hadiths from questionable narrators as well as Christians and Jews. But Shu‘ba felt he was impeccably reliable, ‘Ali b. al-Madini named him one of the pivots of hadith transmission in his age, and all the Six Books except Sahih al-Bukhari relied on him as a narrator. Certainly, this created a great potential for disagreement over the reliability of transmitters and, hence, of hadiths themselves.

To a certain extent, such disagreement was the inevitable result of the complicated careers of transmitters and the contrasting critical thresholds of the many individual analysts examining them and their reports. One critic could change his mind about a transmitter, as al-Bukhari did when he reduced Muhammad b. Humayd al-Razi’s rating from ‘good’ to ‘weak.’ In general, however, later analysts erred on the side of caution and operated on the principle that ‘criticism supersedes approval provided that the reason for the criticism is provided.’ There were limits to this, however. Scholars who had personal vendettas against one another – Malik’s criticism of Ibn Ishaq was the result of a well-documented personal feud between them – were not accepted as fair critics of one another.

Later analysts were often aware of such issues and took earlier critics’ idiosyncrasies and personal leanings into consideration. Al-Juzajani was known to have a vehement dislike for Shiism, so any rejection by him of a transmitter as ‘a heretical Shiite’ was probably an overstatement. If he approved of a transmitter, however, it meant that he was certainly free of any Shiite tendencies. Abu Hatim al-Razi was well known as a very stringent critic – even the seminal legal and hadith scholar al-Shafi‘i had only merited a ‘sincere (saduq)’ rating with him. Ibn Ma‘in was very harsh – once calling a narrator who criticized a Companion a ‘sucker of his mother’s clitoris’ – so his approval carried great weight.45 Ibn ‘Adi was generally very objective. He would limit his evaluations to strict examinations of transmitters’ hadiths for corroboration or its absence. As a result, he would often overturn the disapproval of an earlier critic with a comment such as ‘I have not found uncorroborated reports among his hadiths.’

The Companions of the Prophet achieved a unique place in the worldview of Sunni hadith critics. Although some early historians and transmitters like al-Waqidi (d. 207/822–3) only considered those who reached adulthood during the lifetime of the Prophet to be Companions, the definition that became accepted by Sunnis was much less strict.46 As al-Bukhari notes in his Sahih, a Companion is anyone who saw the Prophet, even for a moment, while a believer and who then died as a Muslim.47

This had tremendous consequences for hadith transmission, for by 900 CE Sunnis considered that all the Companions of the Prophet were automatically ‘upright (‘adl).’ This belief was based on Quranic verses such as ‘You are the best community brought out from humanity (kuntum khayr umma ukhrijat li’l-nas)’ (Quran 3:110) and Prophetic hadiths such as ‘The best of generations is the one in which I was sent, then that which follows, then that which follows.’ In effect, then, the first generation of hadith transmitters was beyond criticism. In fact, the famous ninth-century hadith critic Abu Zur‘a al-Razi stated that anyone who criticized a Companion was a heretic.48

Later analysts would refine this understanding of the Companions’ uprightness. As Ibn Taymiyya (d. 728/1328) explained, the Companions were not perfect – Mughira b. Shu‘ba had lied, and Walid b. ‘Uqba was a known drunkard. But none had ever lied about the Prophet.49 Many Sunni scholars have thus understood uprightness as meaning that the Companions’ exposure to the tremendous spiritual charisma of Muhammad prohibited them from lying about the Prophet but not other sins.50

It is no surprise, then, that Sunni hadith scholars strove to identify who was a Companion. ‘Ali b. al-Madini (d. 234/838) wrote an early work (now lost) listing them, to be followed by Ibn Qani‘ (d. 351/962), Abu Nu‘aym al-Isbahani, and others. Ibn Hajar al-‘Asqalani’s Isaba fi ma‘rifat al-sahaba is the most widely cited biographical dictionary of the Companions. There was great disagreement over the actual number of Companions: al-Shafi‘i estimated their number at sixty thousand, Abu Zur‘a al-Razi at over a hundred thousand. In his biographical dictionary of Companions, Ibn Hajar listed approximately twelve thousand three hundred. On a practical level, the Companions who actually played a noticeable role in hadith transmission were many fewer: the Six Books include hadiths from only 962 Companions.51

The Sunni critics’ view of the Companions was both ideologically driven and practical. Sunni Islam was built on the idea that the Companions of the Prophet had inherited his authority and passed on his teachings reliably. In that sense, as a group they were above reproach. In terms of hadith criticism, however, the critics’ reach did not extend far enough back to apply the rules of transmitter criticism to the Companions. The earliest critic, al-Zuhri, had met only the youngest of the Companions, and his hadith criticism mostly addressed the reports he heard from other Successors. Al-Zuhri, Malik, and Shu‘ba had direct experience with the Successors, but they had no real way to evaluate the uprightness or accuracy of Companions. In a sense, reports such as Aisha’s aforementioned rejection of hadiths for content reasons represent vestiges of hadith criticism from the Companion generation. That the collective impunity of the Companions was a later construct of the Sunni worldview is evident when one finds occasional minor Companions listed in early books of weak hadith transmitters.52

As you might have noticed, the names of the early generations of master hadith critics (Figure 3.1) overlap to a large extent with Figure 2.1 on major hadith transmitters. So did just transmitting a vast number of hadiths make a person a reliable hadith transmitter or an expert critic? The answer seems to be no – just because one was a major transmitter did not mean that one was reliable. Ibn Ishaq was an essential pivot of hadith transmission in Medina, but it became clear to many critics even in his own lifetime that he was not at all discriminating in what he transmitted. Malik, on the other hand, only transmitted from two people (‘Abd al-Karim b. Abi al-Mukhariq and ‘Ata’ al-Khurasani) that he (and later critics) did not feel were reliable (thiqa). Later critics also distinguished between an early critic/transmitter’s own transmissions and his evaluations of others. Al-Zuhri’s opinions carried great influence, but later critics all agreed that his mursal hadiths (see below for a discussion of this term) were too unreliable to use. The great critic Sufyan al-Thawri regularly narrated hadiths that others considered unreliable, whereas when Shu‘ba transmitted a hadith it was understood that he believed it was authentic.

In a similar vein, in the formative period of Sunni Islam in the ninth century, did hadith scholars such as Ibn Hanbal decide which early transmitters to accept based on their Sunni beliefs? Was Sunni hadith criticism just a tool for excluding non-Sunnis? The answers to these questions are certainly ‘no,’ since, as we have seen, Sunni critics regularly accepted the hadiths of people whose beliefs they considered anathema.

Evaluating the sources of a hadith was of little use, however, if a critic could not be sure who these sources were. If one transmitter had never actually met the person from whom they quoted the hadith or if it was known that he had not heard that hadith from his teacher, then who was the intermediary? With no way to guarantee that intermediary’s reliability, there were endless possibilities for what sort of deviation or forgery could have occurred. Establishing that a hadith had been transmitted by a contiguous, unbroken isnad from the Prophet was thus as crucial as transmitter reliability for determining the authenticity of a hadith. If it could not be established that the people in the isnad had heard from one another, then hadith critics considered the chain of transmission broken (munqati‘) and thus unreliable.

In order to determine if an isnad was ‘contiguous (muttasil),’ hadith critics attempted to identify all the people from whom a narrator had heard hadiths. If a transmitter was not a known liar, then one could infer this from his saying ‘So-and-so narrated to me (haddathani),’ ‘so-and-so reported to us (akhbarana),’ or ‘I heard from so-and-so (sami‘tu min ...).’ Other phrases for transmission did not necessarily indicate direct transmission. ‘According to (‘an)’ could mean that someone had heard a hadith directly from the person in question or not. In addition to looking at this terminology, a critic would compare the death date of the teacher with the age of the student and investigate the possibility that they were in the same place at the same time.

Because establishing contiguous transmission was so important, by the mid 700s transmitters had become very serious about specifying exactly how hadith transmission occurred. The most accurate forms of direct transmission were either reading a teacher’s hadiths back to him (often indicated by the phrase ‘he reported to us, akhbarana’) or listening to the teacher read his hadiths (often indicated by ‘he narrated to us, haddathana’). If a teacher gave a student his books of hadiths to copy, this was termed ‘handing over (munawala).’ We have already discussed ‘permission to transmit (ijaza)’ in the last chapter. Although there was debate over whether reading hadiths to a teacher or hearing them read was more accurate, all scholars acknowledged that ‘handing over’ and ‘permission to transmit’ were the most tenuous forms of transmission. Reading a book with no transmission from the teacher at all (‘finding, wijada’) inspired no confidence at all.

Transmitters fretted over these forms of narration and often debated the proper terminology. The Hanafi al-Tahawi (d. 321/933) wrote a short treatise on how the technical terms ‘akhbarana’ and ‘haddathana’ actually meant the same thing (also the opinion of the majority of scholars). When al-Awza‘i gave a book of hadiths to a student in an act of ‘handing over,’ the student asked, ‘About this book, do I say “haddathani”?’ Al-Awza‘i replied, ‘If I narrated it directly to you, then say that.’ The student inquired, ‘So do I say “akhbarani”?’ Al-Awza‘i replied that no, he should say ‘al-Awza‘i said’ or ‘according to al-Awza‘i.’53

Not all critics agreed on the requirements for a contiguous isnad. There was disagreement over whether the phrase ‘according to (‘an)’ should be interpreted as an indication of direct transmission or not. Muslim b. al-Hajjaj claimed that the great hadith critics had all accepted ‘an as indicating direct transmission provided that the two people involved were contemporaries and that it was likely that they had met one another. Others, like Ibn ‘Abd al-Barr (d. 473/1070) and al-Khatib al-Baghdadi, claimed that hadith critics had agreed that one needed proof that the two transmitters had actually met at least once.

Critics of the eighth, ninth, and early tenth centuries often attempted to be more exact than just establishing if two transmitters had met. They sought to determine exactly which hadiths certain transmitters had heard from their teachers. Shu‘ba thus studied the hadiths of his teacher Qatada until he found that he had only heard three from his teacher Abu al-‘Aliya.54 This was especially important in the case of tadlis, or obfuscation in transmission. Tadlis occurred when a transmitter cited an isnad in an ambiguous manner, such as saying ‘soand-so said,’ implying that he had heard the hadith directly from the person when in fact he was omitting his immediate source for the hadith. Transmitters might hide their immediate source because he or she was considered unreliable or espoused beliefs unacceptable in Sunni Islam. Tadlis did not always occur for insidious reasons. If a student had to leave a dictation session to answer nature’s call, for example, he would hear the hadiths that he had missed from a classmate. When narrating those hadiths, however, he might leave out the classmate’s name and simply say ‘Teacher so-and-so said.’ Because tadlis was often innocuous, very few transmitters were totally innocent of it. Only Shu‘ba b. al-Hajjaj was known to never lapse into it.

Identifying tadlis was a primary concern of critics in the eighth century and beyond. By interrogating a transmitter a critic could determine whom he omitted from isnads in instances of tadlis. Transmitters like Sufyan b. ‘Uyayna, who only omitted the names of reliable figures, could be trusted even when doing tadlis. Others who often omitted the names of weak narrators, like Ibn Ishaq, could not.55 Al-Khatib al-Baghdadi and Ibn Hajar both wrote books discussing tadlis and those accused of it.

Similar to tadlis was the phenomenon of mursal hadiths, or instances in which someone quoted the Prophet without ever having met him. If a Successor or an early scholar like Malik said ‘the Prophet said,’ this was clearly an incomplete isnad since Malik never met the Prophet. Mursal hadiths occurred because, especially in the first few generations of Muslims, scholars were not obsessive about providing detailed isnads for every report all the time. Al-Zuhri, Malik, or Abu Hanifa might quote the Prophet while discussing a legal issue informally without bothering to provide an isnad.

When such mursal hadiths were recorded in musannaf works like the Muwatta’ or the legal responses of Abu Hanifa, however, they presented a problem for later hadith critics. How should they be treated? Because mursal hadiths had incomplete isnads and one could not be sure from whom a Successor was narrating, mursals were almost always considered unreliable by hadith critics. After extensive research on the mursal reports of certain early transmitters, however, and attempts to find counterparts to them with full isnads, critics approved of certain transmitters’ mursal hadiths. Al-Shafi‘i concluded that the mursals of the Successor Sa‘id b. al-Musayyab (d. 94/713) were reliable because the source he omitted, his father-in-law Abu Hurayra, was the most knowledgeable Companion about hadiths. Critics debated the reliability of al-Hasan al-Basri’s mursal hadiths – his contemporary Ibn Sirin said that al-Hasan was totally uncritical about his hadith sources, so his mursals were useless. Yahya al-Qattan said that he had studied all of al-Hasan’s mursals and found versions with full isnads for all but two of them.56 Ibn Abi Hatim al-Razi composed a whole book entitled Kitab al-marasil (The Book of Mursals) in an attempt to determine which Successors had heard hadiths from which Companions.

Corroboration had played a central role in determining the reliability of a transmitter – if he narrated hadiths that other students of his source did not, then his reliability was questioned. But a forger could still simply take an isnad of a respected transmitter and attach it to a freshly concocted hadith. The third and final step in hadith criticism thus involved looking for corroboration for the hadith itself.

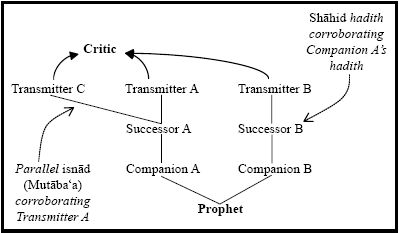

Corroboration took two general forms. Since a ‘hadith’ was generally associated with the Companion who narrated it, another version of the same Prophetic tradition transmitted by a second Companion or an instance of the Prophet saying something similar on another occasion were both considered corroboration for a hadith. Such a report was termed a ‘witness (shahid).’ When one transmitter corroborated the report related by another transmitter that they had both heard from a common source, this was termed a ‘parallelism (mutaba‘a).’ Hadith scholars described these two forms of corroboration with the aphorism ‘parallelism bolsters the narration, a witness bolsters the tradition.’ A witness report need not be exactly the same tradition as the hadith it supports. Even a report with a different wording but the same meaning corroborated the fact that the Prophet had expressed a certain idea or sentiment. Parallelisms solidified the reliability of a particular narration of a hadith.

A famous tenth-century hadith critic, Ibn Hibban, describes the process of searching for corroboration (called i‘tibar, ‘consideration’) thus:

Let us say we come across [the transmitter] Hammad b. Salama, and we see that he has narrated a report from Ayyub [al-Sakhtiyani]  Ibn Sirin

Ibn Sirin  Abu Hurayra

Abu Hurayra  the Prophet (s), but we do not find that report from anyone else from the students of Ayyub. What is required of us now is to refrain momentarily from criticizing Hammad, and to consider what his contemporaries narrated. So we must start by looking at this report: Did Hammad’s students in general narrate it from him, or just one of them? If it is the case that his students narrated it from him, then it has been established that Hammad really did narrate that report, even if that comes through a weak narrator from him, because that narration is added to the first narration from Hammad. So if it has been established correctly that Hammad narrated a report from Ayyub that is not corroborated by others, again we must pause. For it does not follow automatically that there is some weakness here, but rather we must ask: Did any of the reliable transmitters (thiqat) narrate this report from Ibn Sirin other than Ayyub? If we find one, then it has been established that the report has some basis (asl yarji‘u ilayhi). If not, then we must ask: Did anyone from among the reliable transmitters narrate this report from Abu Hurayra other than Ibn Sirin? If such a narration is found, then it has been established that the report has a basis (asl). If not, we ask: Did anyone narrate this report from the Prophet (s) other than Abu Hurayra? If so, then it has been established correctly that the report has some basis. But when that is not the case, and the report contradicts the compilations of these three [people at three levels in the isnad], then it is established without a doubt that the report is forged, and that the lone person who narrated it forged it.57

the Prophet (s), but we do not find that report from anyone else from the students of Ayyub. What is required of us now is to refrain momentarily from criticizing Hammad, and to consider what his contemporaries narrated. So we must start by looking at this report: Did Hammad’s students in general narrate it from him, or just one of them? If it is the case that his students narrated it from him, then it has been established that Hammad really did narrate that report, even if that comes through a weak narrator from him, because that narration is added to the first narration from Hammad. So if it has been established correctly that Hammad narrated a report from Ayyub that is not corroborated by others, again we must pause. For it does not follow automatically that there is some weakness here, but rather we must ask: Did any of the reliable transmitters (thiqat) narrate this report from Ibn Sirin other than Ayyub? If we find one, then it has been established that the report has some basis (asl yarji‘u ilayhi). If not, then we must ask: Did anyone from among the reliable transmitters narrate this report from Abu Hurayra other than Ibn Sirin? If such a narration is found, then it has been established that the report has a basis (asl). If not, we ask: Did anyone narrate this report from the Prophet (s) other than Abu Hurayra? If so, then it has been established correctly that the report has some basis. But when that is not the case, and the report contradicts the compilations of these three [people at three levels in the isnad], then it is established without a doubt that the report is forged, and that the lone person who narrated it forged it.57

As Ibn Hibban describes, if a report is not corroborated at any one level of the isnad, then the reliability of that transmitter’s narration from his source is dubious. If the report is uncorroborated at all levels of the isnad, then it is almost certainly totally baseless. If a report was not corroborated either at some level of the isnad or from the Prophet in general, early hadith critics deemed it ‘unacceptable (munkar).’

Of course, this process of demanding corroboration took context into consideration. As Muslim b. al-Hajjaj informs us, ‘If it has been established that your hadith corpus agrees with those of the other reliable narrators, then narrating some uncorroborated material is acceptable.’58 If a transmitter studied with a certain teacher for ten years, then it is not surprising that he might narrate a selection of hadiths from his teacher that students who only studied with him for six months did not recount. The great critic Abu Hatim al-Razi was asked to criticize ‘Abdallah b. Salih, the secretary of Layth b. Sa‘d, for having narrated uncorroborated hadiths from Layth. Abu Hatim replied sarcastically, ‘You ask me this about the closest person to Layth, who was with him on voyages and at home and spent much time alone with him?’59 But, Muslim continues, if some lesser known transmitter narrated a hadith from a prolific hadith scholar like al-Zuhri whose numerous and respected students did not recognize that hadith, then that report would be automatically declared ‘unacceptable (munkar).’60

Like our modern investigative reporter’s source, however, a transmitter could earn such a level of confidence in the eyes of critics that he could narrate uncorroborated reports without arousing concern. Critics like al-Bukhari and Ibn ‘Adi had examined the hadiths of master transmitters like al-Zuhri, Malik, Ibn al-Mubarak or Qutayba b. Sa‘id and found that they were corroborated to such a great extent that they could be relied upon for a number of uncorroborated hadiths as well. These figures were so central to hadith transmission in general that if anyone were to have heard a rare hadith, it would be them. An uncorroborated hadith narrated by an isnad of such pillars was known as ‘an authentic rare (sahih gharib)’ hadith. The hadith of Malik  al-Zuhri

al-Zuhri  Anas that the Prophet entered Mecca upon its conquest with a mail helmet on his head and ordered the killing of Ibn Khatal, an infamous enemy of Islam, was known only by this isnad. Because this hadith was narrated by transmitters whose collections of hadiths were vaster than almost any other people of their time, this hadith was considered authentic even though it was uncorroborated.61

Anas that the Prophet entered Mecca upon its conquest with a mail helmet on his head and ordered the killing of Ibn Khatal, an infamous enemy of Islam, was known only by this isnad. Because this hadith was narrated by transmitters whose collections of hadiths were vaster than almost any other people of their time, this hadith was considered authentic even though it was uncorroborated.61

Conversely, less stellar figures inspired no such confidence. As al-Tirmidhi explained, ‘Anyone from whom a hadith is narrated who is accused [of poor performance in hadith] or is criticized as weak in hadiths for his lack of carefulness and numerous mistakes, if that hadith is only known through that narration, it cannot be used as proof.’ So the hadith narrated by the lone isnad of Nasih al-‘Ajami  Simak b. Harb

Simak b. Harb  Jabir b. Samura

Jabir b. Samura  the Prophet: ‘For a man to teach his child proper manners is better than to give a whole bushel in charity (li’an yu’addiba al-rajul waladahu khayr min an yatasaddaqa bi-sa’)’ was considered unacceptable (munkar) because neither Nasih nor Simak were consistently reliable transmitters.62

the Prophet: ‘For a man to teach his child proper manners is better than to give a whole bushel in charity (li’an yu’addiba al-rajul waladahu khayr min an yatasaddaqa bi-sa’)’ was considered unacceptable (munkar) because neither Nasih nor Simak were consistently reliable transmitters.62

Even when an isnad looked perfect, early hadith critics did not completely ignore the need for comparing it with other narrations of the report. As the eleventh-century critic al-Khalili (d. 446/1054) warned, ‘Even if a hadith is provided to you with an isnad from al-Zuhri or another one of the masters, do not declare it authentic merely because of that isnad, for even a reliable transmitter (thiqa) can err.’63 By comparing different versions of the same hadith, critics could uncover flaws, known as ‘ ilal, which might have evaded the best transmitter. Such flaws included one narration of a hadith adding additional words into the text of the report that are not found in more reliable versions. A very common flaw was that one narrator would confuse a Companion’s or Successor’s statement with a Prophetic hadith. The great ‘ilal critic of Baghdad, al-Daraqutni, found such an error in Muslim’s famous Sahih. By examining all the narrations of a report describing how God will grant the believers a vision of Himself on the Day of Judgment, al-Daraqutni concluded that these were actually the words of the Successor ‘Abd al-Rahman Ibn Abi Layla (d. 82/701–2) and not of the Prophet.64

To uncover these ‘ilal, a critic would gather all the narrations of a hadith and attempt to determine which ones were the most reliable. If the majority of respected transmitters, for example, reported that a certain saying was the statement of a Companion, even one strong isnad tracing that report back to the Prophet would be considered a mistake.

This advanced level of seeking out corroboration and comparing narrations was set down in books of ‘ilal, a genre that flourished in the ninth and tenth centuries. The ‘ilal works of ‘Ali b. al-Madini, Ibn Hanbal, and Ibn Abi Hatim al-Razi were very famous, but the massive ‘ilal book of al-Daraqutni, published in eleven volumes, dwarfs them all. After the 1000s, ‘ilal books became rare, and only unusually competent later critics like the Moroccan Ibn al-Qattan al-Fasi (d. 628/1231) or Ibn al-Jawzi (d. 597/1201) produced them. ‘Ilal criticism was only possible for critics in the early period when hadiths were still narrated by full isnads and critics had access to versions of reports that may not have survived into later times.65 As al-Suyuti admitted, by the 1400s hadith critics did not have the vast array of musannafs, hadith notebooks, and dictation sessions available to a scholar like al-Daraqutni. Such later scholars could only judge hadiths based on material they received from earlier critics.66

When we think of how one should evaluate the reliability of things we hear, we focus on their content as much as their source. Even the most trustworthy source would arouse suspicion if he announced that aliens had landed in his backyard. Yet when we thumb through books of transmitter criticism or ‘ilal, one of the most obvious characteristics of early hadith criticism is that early scholars almost never discussed the contents of hadith, let alone explicitly rejected a hadith because its meaning was unacceptable. Why is this?

Certainly, the esteem in which Muslims held Muhammad and their belief that God spoke to him of the distant past and events to come affected their approach to criticizing hadiths. Unlike a modern person skeptically dismissing the sayings of a television psychic, a Muslim critic would not declare a report attributed to Muhammad to be a forgery simply because it described something that average men could not know.

Nonetheless, we know that early critics like al-Bukhari and Muslim were willing and able to reject a hadith because they found its contents inherently flawed. In his entry on the transmitter ‘Awn b. ‘Umara al-Qaysi in his ‘Great Book of Weak Transmitters,’ al-Bukhari noted that one of the unacceptable hadiths he narrated was ‘The signs of the Day of Judgment are after the year 200/815.’ Al-Bukhari rejects the hadith because ‘these two hundred years have passed, and none of these signs have appeared.’67 In another work on transmitters, al-Bukhari criticizes Muhammad b. Fada’ because he narrated the hadith ‘The Prophet forbade breaking apart Muslim coins in circulation.’ Al-Bukhari notes that Muslims did not mint coins until early Umayyad times, ‘they did not exist at the time of the Prophet.’68 Muslim b. al-Hajjaj rejects a hadith saying that there are five chapters of the Quran that are the equivalent of one-fourth of the holy book – a total of five-fourths. He calls this logical contradiction ‘reprehensible, and it is not conceivable that its meaning is correct.’69 But why were such instances of content criticism so rare?

To answer this question, we have to remember that Sunni hadith criticism emerged in the context of intense ideological struggle between the ahl al-hadith and the school of early Muslim rationalists, known as the Mu‘tazila. For the Mu‘tazila, the only sources on which one could rely to interpret properly Islamic law and dogma were the Quran, reports from the Prophet that were so well-known they could not possibly be forged, and human reason (‘aql). In order to know if any hadith was authentically from the Prophet, Mu‘tazilite scholars like Abu al-Qasim al-Balkhi (d. 319/931) believed that it had to agree with the Quran and reason.

For Mu‘tazilites, the idea that one could examine the isnad of the hadith to know if it was reliable or not was preposterous. The Mu‘tazilite master Abu ‘Ali al-Jubba’i (d. 303/915–16) was once asked to evaluate two hadiths narrated through the same isnad. He declared the first hadith authentic but rejected the second as false. When a surprised student asked al-Jubba‘i, ‘Two hadiths with the same isnad, you authenticate one and reject the other?’, al-Jubba’i replied that the second one could not be the words of the Prophet because ‘the Quran demonstrates its falsity, as does the consensus of the Muslims and the evidence of reason.’70

The ahl al-hadith’s understanding of man’s relationship to religion was the converse. Only by submitting oneself completely to the uncorrupted ways of the Prophet and early Muslim community as transmitted though the isnad could one truly obey God and His Messenger. Unlike the Mu‘tazila, whom they saw as arrogantly glorifying human reason, or the ahl al-ra’y, whom they viewed as rejecting or accepting hadiths arbitrarily when it suited their legal opinion, the ahl al-hadith perceived themselves as ‘cultivating the ways of the Messenger, fending off heretical innovation and lies from revealed knowledge.’71 It was not man’s right to question the revealed religion that the Prophet brought and that was preserved from him through the isnad. We thus find the Companion ‘Imran b. Husayn (d. 52/672) instructing new Muslims that the Prophet had said, ‘Whoever is grieved for [by his family] will be punished [for that mourning] (man yunahu ‘alayhi yu‘adhdhab).’ When a person questioned the reasonableness of this notion, ‘Imran replied, ‘The Messenger of God has spoken the truth, and you have disbelieved!’72 A defender of the ahl al-hadith against the Mu‘tazila, Ibn Qutayba (d. 276/889) states:

We do not resort except to that to which the Messenger of God resorted. And we do not reject what has been transmitted authentically from him because it does not accord with our conjectures or seem correct to reason ... we hope that in this lies the path to salvation and escape from the baseless whims of heresy.73

But we know from the examples above that early Sunni hadith critics did note problems in the meanings of certain hadiths. In their context, however, it is clear why they could not do so openly. The whole purpose of the isnad was to guarantee that the Prophet said something without relying on man’s flawed reason. If hadith critics admitted that a hadith could have an authentic isnad but still be a forgery because its meaning was unacceptable, then they would be admitting that their rationalist opponents were correct! If you could not have a strong isnad with a forged report, then any problem in the meaning of a hadith must mean that there was a problem in the isnad. When ahl al-hadith critics like al-Bukhari came across a hadith whose meaning they found unacceptable, they examined the isnad to find how the error occurred and listed the hadith in the biography of that transmitter as evidence of his weakness. Ibn ‘Adi often states that the questionable hadiths that a certain transmitter narrates ‘demonstrate that he is unreliable.’

Because early hadith criticism was so openly focused on the isnad as the primary means of authentication, it was very often difficult to tell when a critic was rejecting a whole Prophetic tradition or just one narration of that hadith. The term ‘unacceptable (munkar)’ for a hadith could mean that this version of the hadith narrated through a certain isnad was unreliable but other authentic versions existed, or that the tradition was entirely forged. Another phrase used to reject a hadith, ‘it has no basis (laysa lahu asl),’ could mean that the hadith had no basis from that transmitter (but was well established from others) or that the Prophetic tradition was baseless in general. But even concluding that the terms munkar or la asl lahu denoted ‘forged’ does not necessarily mean that the critic found the meaning of the hadith in question unacceptable. As Ibn ‘Abd al-Barr (d. 463/1070) explained, ‘How many hadiths are there with a weak isnad but a correct meaning?’74 Al-Tirmidhi notes that Yahya al-Qattan had declared the following hadith narrated by Anas b. Malik to be munkar: ‘A man said, “O Messenger of God, should I tie up [the camel] and trust in God or leave it free and trust in God.” The Prophet said, “Tie it up and trust in God.” ’ Al-Tirmidhi adds that this report was totally baseless from Anas, ‘but its likes have been narrated from another Companion ‘Amr b. Umayya al-Damri, from the Prophet.’75

Starting in the late 1000s, however, as the Mu‘tazilite rationalist threat faded from view and Sunni Islam emerged triumphant, hadith critics began writing books that rejected whole Prophetic traditions, often because their meanings were unacceptable. These books were known as works of mawdu‘at, which listed ‘mawdu‘,’ or ‘forged’ hadiths. The earliest known mawdu‘at book, unfortunately lost to us, was that of Abu Sa‘id al-Naqqash al-Isbahani (d. 414/1023).76 The earliest surviving one is the Tadhkirat al-mawdu‘at of Muhammad b. Tahir al-Maqdisi (d. 507/1113). Perhaps the most famous mawdu‘at work is the huge Kitab al-mawdu‘at of Ibn al-Jawzi (d. 597/1201). Mawdu‘at books flourished in later Islamic times, with well-known works including the Ahadith al-da‘ifa of Ibn Taymiyya (d. 728/1328), al-La’ali al-masnu‘a of al-Suyuti, the Asrar al-marfu‘a of Mulla ‘Ali Qari, the Fawa’id al-majmu‘a of the Yemeni Muhammad al-Shawkani (d. 1834), and the Kitab al-athar al-marfu‘a of the Indian ‘Abd al-Hayy al-Laknawi (d. 1886-7). Some of these scholars wrote books on forged hadiths designed to be useful references for non-experts. ‘Umar b. Badr al-Mawsili (d. 622/1225), for example, wrote the book Sufficing One from Memorization and Books on Issues on which there are No Reliable Hadiths (al-Mughni ‘an al-hifz wa al-kitab fima lam yasihha shay’ fi al-bab).

We start finding a willingness openly to reject hadiths because their meanings are unacceptable in the early mawdu‘at book of al-Jawzaqani (d. 543/1148–9), who states ‘Every hadith that contradicts the Sunna is cast away and the person who says it is rejected as a transmitter.’77 This process reached a plateau with the al-Manar almunif fi al-sahih wa al-da‘if (‘The Lofty Lighthouse for Authentic and Weak Hadiths’), the mawdu‘at book of Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya (d. 751/1350), who devoted a large section of the work to listing all the features of a hadith’s contents that demonstrated it was forged.

Of course, freely engaging in content criticism was opening a Pandora’s box. A critic might fall into exactly that trap that the early ahl al-hadith claimed they were avoiding: making man’s flawed reason the arbiter of religious truth. Although later critics would maintain, as Ibn al-Jawzi states, ‘any hadith that you see contradicting reason or fundamental principles [of Islam], know that it is forged,’ they would also insist that one should not be too hasty in such judgments. After all, the critic might not have grasped the proper way of reconciling such contradictions.78 This tension between submitting one’s reason to a transmitted text and using one’s reason to evaluate the text’s authenticity has furnished fertile ground for debate among Muslim scholars until today.