If there be a Paradise on earth, it is now, it is now, it is now!

—Wilfred Noyce, describing the area above NagDAADa in

Climbing the Fish’s Tail (Machhapuchhre)

Scenic Pokhara is the usual starting point for a visit to the Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP). A circuit of the Annapurna massif combines superlative mountain scenery with incredible ethnic and cultural diversity and traverses through very different ecological life zones. Despite encroachment by motor roads, this classic trek is among the world’s best and receives the most visitors of Nepal’s trekking areas, over 75,000 in 2009.

The government decided in 2005 to construct roads to both Jomosom and Manang, headquarters of their respective districts. The Annapurna Circuit was formerly over 135 miles (215 km) long, and the roads, when completed, could potentially reduce the Annapurna Circuit to around 19 miles (30 km), although variations abound and will be covered below. The road to Jomosom is already complete, barring seasonal monsoon washouts, while construction work remains on the Manang side. (An unpaved road from the Tibet Autonomous Region has also been constructed into Upper Mustang and will soon link to Jomosom as well.)

Ostensibly, the road construction was to alleviate poverty by facilitating development. However, politics played a role, and the construction has been controversial among Nepalis and foreign visitors. ACAP is under a lot of change because of these new roads, and nobody knows how it will settle out. Alternate routes are being explored away from the roads. There is genuine fear on the part of some lodge owners along the main routes of losing their livelihood. New paths have yet to be decided or prepared for tourist arrivals. Even still, it is possible to trek the circuit while avoiding the current vehicular traffic for much of the way, as will be outlined below. Often where there is a road, there are two options to follow: (1) more adventurous routes where you might have to arrange your own lodging and food in homes, or (2) the well-trodden, often jeepable routes. If you get off the main routes, be prepared for more of an adventure and to take it how it comes; be prepared for a lack of facilities and comforts, and to ask for the generosity of the local people if caught short in a village without a lodge or restaurant.

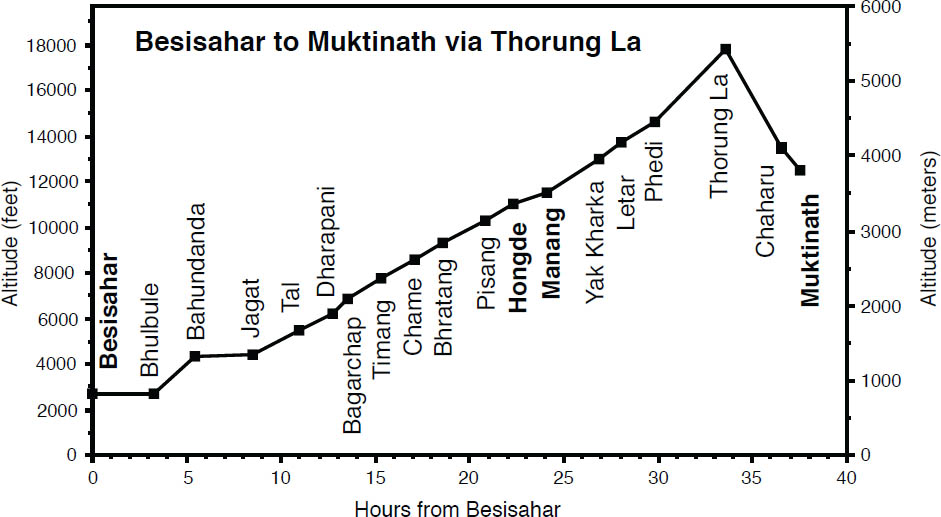

Traditionally, the Annapurna Circuit is completed in a counterclockwise direction. That is, most people start at Besisahar and follow the Marsyangdi valley to Manang before crossing to the high Thorung La over to Muktinath and the Thak Khola/Kali Gandaki valley.

The Annapurnas viewed from Ghorepani (Photo by Tokozile Robbins)

The circuit route and facilities make the counterclockwise direction more feasible for crossing the Thorung La, as the only lodges between Muktinath and the pass (clockwise) are at Chaharu (also known as Phedi) at 13,690 feet (4172 m), whereas there are lodges up to 15,995 feet (4875 m), over 2300 feet (700 m) higher, on the Manang side and seasonal tea shops beyond. Trekkers who do not have the inclination or time to complete the whole circuit and cross Thorung La may opt for visiting one or the other of the major river valleys of the circuit, the Kali Gandaki/Thak Khola (west) and the Marsyangdi (east).

The term Annapurna Sanctuary, coined by outsiders, denotes the high basin southwest of Annapurna and the headwaters of the Modi Khola. This vast amphitheater, surrounded by Himalayan giants, can be visited as a circuit from Pokhara in less than 10 days. However, to enjoy the route and the sanctuary itself without feeling rushed, plan a few more days. This area can be easily combined with the entire Annapurna Circuit or with a trek to Jomosom that offers various link-up possibilities.

Many people take shorter journeys from Pokhara. Popular options are below; the relevant trail portions can be picked out from the descriptions that follow.

• Naya Pul to Tatopani via GhoRepani and Poon Hill, down to the Kali Gandaki and the developed hot springs at Tatopani where transportation is available to Beni and on to Pokhara (4–5 days);

• A circuit from Phedi through Landruk and Ghandruk, beautifully placed villages, and then out to Naya Pul (3 days) or on to GhoRepani and out to the road at Naya Pul or Tatopani (5 days);

• The less-traveled Gurung Heritage Trail, Thumsikot to Khudi, see Chapter 9 (4 days).

A short trek, almost all downhill, is to fly to Jomosom, perhaps paying a visit to Kagbeni and Muktinath if you first acclimatize, then walking south to Tatopani in 4 days, and then taking a vehicle to Pokhara. Those wishing to get a taste of a climb and viewpoint could visit GhoRepani and pick up the bus at Naya Pul. The section from Jomosom to Tatopani is one of the most westernized rural areas in Nepal. It has been very popular with trekkers. Well-furnished lodges and restaurants provide many tourist facilities unheard of elsewhere in Nepal. For this reason, some trekkers prefer to avoid this area, but it is very attractive to others.

Many of these treks begin at low elevations and follow valley floors. It can get very warm in late spring, so dress appropriately and try not to push yourself, especially in the first few days. Relax during the midday, try to be in the shady side of the valley in the afternoon, or carry an umbrella against sunlight.

A visit inside anywhere in the ACAP area requires an ACAP permit and TIMS card. The ACAP entry permit is available at the conservation area’s counter in Bhrikutimandap, Kathmandu, on Exhibition Marg Road, just up from Ratna Bus Park, or at the ACAP offices in Pokhara. The permit fee is 2000 NRS; that amount is doubled if the permit is purchased at a park entry point rather than beforehand. TIMS cards, $20 USD, are also available at Bhrikutimandap at a separate TIMS counter as well as at the combined ACAP/NTB office in Pokhara and at the TAAN offices (difficult to locate) in both Kathmandu and Pokhara.

Although now there is a road route, the trek from Pokhara to Jomosom on the Kali Gandaki, or the Thak Khola, as the river is called in its northern portions, is one of the easiest and most comfortable treks, in addition to being one of the most popular, in Nepal. ACAP is considering alternative routes away from the road, and we have described what is currently available, although more is to come. There is relatively little climbing, cooked food and lodging are easily available along the entire route, and the terrain is more varied than on any other trek of comparable length. Although the route passes among some of the highest mountains in the world, the scenery may not be as exciting as in, say, Khumbu. Despite the road, on this route you are still likely to encounter colorful mule caravans made musical by the tinkling of neck bells. There are several side trips out of the Kali Gandaki valley less frequented by trekkers. Though strenuous, they reward tired hikers with spectacular views and give them a glimpse of the immense scale of the valley. Muktinath, a Hindu and Buddhist pilgrimage site, is a day’s walk north of Jomosom.

Unless you plan a side trip to one of the uninhabited areas, there is no need to carry food or shelter. Lodges or hotels in most villages offer food and accommodations that are Western in style. These places are run by the Newar, Thakali, Gurung, and Magar ethnic groups.

Transportation from Kathmandu to Pokhara is available daily via several airlines or by road. To avoid backtracking, you could take a plane to or from Jomosom, although flying in is not recommended because of rapid altitude gain (Jomosom is at 9120 feet, 2780 m). It may be difficult to get a seat on a scheduled flight, as flights are often canceled due to bad weather and high winds.

Frequent buses ply the road from Pokhara all the way to Beni, a starting point that avoids the steep uphill and subsequent downhill through GhoRepani. Otherwise, you can start from the road at Naya Pul or Phedi and then pass through GhoRepani and meet the route from Beni near Tatopani with sensational views along the way. See the alternate approach in the Annapurna Sanctuary section for the route from GhoRepani to Ghandruk. Stephen’s first trek in 1969 began from the airstrip in Pokhara because there was no road, and beginning at Pokhara can still be done by first ascending to Sarangkot on the ridgeline above Pokhara, and then following the ridge to Naundanda and from there the road down to Phedi (or on to Lumle and beyond).

The Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP) has sought to standardize facilities for trekkers and to facilitate travel north of Pokhara. Trekkers will find signboards at the entrance to many villages in this area. Developed by the ACAP, they indicate the route through the village as well as the registered establishments. There is an ACAP trekker’s information center a five- to ten-minute walk south of the Immigration Department in Pokhara, near an intersection that is known as Rastra Bank Chowk (see the map of Pokhara in chapter introduction). Trekking permits are arranged here, as well as Trekkers’ Information Management System (TIMS) cards at the Nepal Tourism Board desk in the same building. The separate, large compound of the ACAP headquarters is in a different location of Pokhara and is also a source of information for the visitor. To get there, follow the road toward Kathmandu on the way out of town. After the bridge over the Seti Gandaki River, pass a stadium on the right, and take the first avenue to the right. Follow the street for about a half hour’s walk, and the ACAP headquarter offices will be a large compound on the left-hand side of the road.

From Pokhara (2713 feet, 827 m) you can either walk, or board a bus or taxi to to the Baglung bus station (Nala Mukh or Besi Parak, different from the Bas Parak, near Mahendra Pul), at the northern end of Pokhara. Buses leave regularly.

The first place trekkers leave the road is at Phedi to travel either into the sanctuary or up to Ghandruk and over to GhoRepani and then down to Birethanti/Naya Pul for a short circuit loop, or down to Tatopani.

Another place to leave the road is near Lumle, the site of a British agricultural development project where former Gurkha soldiers are trained in farming. It has one of the highest rainfalls in Nepal. Walk from Lumle (5300 feet, 1615 m) to Chandrakot (5250 feet, 1600 m) at the west end of the ridge in 30 minutes. The views from Chandrakot are unforgettable. You will cross the Modi Khola, flowing south from between the peaks Annapurna South and Machhapuchhre, which stand before you. (The Annapurna Sanctuary, which lies upriver inside the gate formed by Machhapuchhre and Hiunchuli, the peak east of Annapurna South, is described later.) The trail descends to the Modi Khola, follows its east (left) bank southward a short distance to a suspension bridge, and crosses to the prosperous town of Birethanti (3600 feet, 1097 m), 1¼ hours from Chandrakot.

Usually, trekkers come to Birethanti by taking the bus going to Beni and getting off at Naya Pul, 30 minutes south of Birethanti. If coming from the road at Naya Pul, cross the Lumle Khola (3315 feet, 1010 m) from the bus drop-off point and walk north to the suspension bridge (3430 feet, 1045 m) just east of Birethanti. There is an ACAP check post where you register. From here, one trail heads up the Modi Khola on its west (right) bank toward the Annapurna Sanctuary. The trail to GhoRepani and on to the Kali Gandaki/Thak Khola heads west up the Bhurungdi Khola. Just up from the town by a picturesque waterfall is a cool pool on the Bhurungdi Khola. If you swim here, be sure to wear adequate clothing in order not to offend the Nepalis.

Follow the Bhurungdi Khola westward, at first through forests. Stay on its northeast (left) bank, crossing a suspension bridge (3707 feet, 1130 m) over a tributary to reach Malathanti (3793 feet, 1156 m) in 45 minutes while avoiding suspension bridges across the Bhurungdi Khola. Pass through the settlements of Lamthali, Rangai, and Sudame. Hille (5000 feet, 1485 m) is reached in 1¼ hours from Malathanti, and 10 minutes beyond is TirkheDUgaa (5175 feet, 1530 m). Farther on, the branches of the Bhurungdi Khola are crossed on several bridges (the last bridge is at 5075 feet, 1500 m). The steepest climb so far, up to picturesque Ulleri (6800 feet, 2025 m), a Magar village, takes 2 hours from Hille.

If you want to pace the climb, there are 3767 steps to ascend to Ulleri; trekker Lance Hart counted them! Note the handsome slate roofs on the village houses. Higher up, at a chautaaraa, you may still see a worn rock tablet faintly inscribed as follows: “Once, sweet, bright joy, like their lost children, an Ulleri child.” It is a memorial to eighteen-month-old Ben, the son of anthropologist John Hitchcock. Ben died here in 1961 while his father was doing fieldwork.

From Ulleri, the trail climbs steadily, enters lush oak forest, and crosses numerous small streams. It is a great place for bird-watching; however, lone trekkers have been attacked by bandits in this forest. If by yourself, hire a porter or join up with others. This caution applies all the way to Chitre on the other side of GhoRepani.

Above Ulleri you pass through Banthanti (7775 feet, 2240 m), and then Nayathanti (8550 feet, 2535 m), both with lodges and small shops. The trail emerges at GhoRepani (9250 feet, 2790 m), with a cluster of hotels and an ACAP office, below the pass some 3 hours from Ulleri. GhoRepani, meaning “horse water,” is now a far cry from the one building Stephen saw on his first trek in Nepal in 1969. Then it truly was a watering hole for the horse caravans that traveled between Pokhara and Mustang. There is public telephone service here. There are more hotels at the pass, GhoRepani Deorali (9450 feet, 2880 m). Trekkers should make certain they catch the views, either from the pass itself, which is now a swarm of lodges, or from east or west of the pass. On Stephen’s first trek here, there were no views from the pass, as it was in a dense rhododendron forest.

Poon Hill (named for the Pun clan of the Magar ethnic group), on the ridge to the west, is a popular viewpoint (10,478 feet, 3194 m). Reach the lookout in less than 1 hour. Signs point the way to Poon/Pun Hill from GhoRepani and from the pass. Views from Poon Hill of Dhaulagiri and the Kali Gandaki gorge are best in the early morning, when it can get pretty crowded. Some people enjoy the view best an hour after sunrise, when most trekkers have left. The south face of Dhaulagiri, the most impressive feature seen, was climbed first by a Japanese party in 1978 via the left buttress and by a Yugoslav team in 1981 via the eastern. The most challenging central section awaits an ascent, although a large portion of it was climbed solo in 1999 by the late Tomaž Humar, a prodigious climber from Slovenia; however, the summit of Dhaulagiri was not reached.

From the pass, a trail follows the ridge to the east to link with the trail from Ghandruk. The views to the east along the ridge are impressive as well. This route, which will be described later, offers a different return to Pokhara for those who have traveled north from Ulleri.

A guest house balcony offers a sensational viewpoint of the Dhaulagiri Range as well as a place to dry laundry. (Photo by Tokozile Robbins)

To continue to Thak Khola, descend through rhododendron forest, then prickly-leafed oak, to cultivated areas. Reach the right fork (7900 feet, 2407 m) of the trail to Ghandruk, with Chitre (7875 feet, 2400 m) below, and cross landslides to PhalaTe (7400 feet, 2256 m) and an ACAP checkpost, before reaching Sikha (6820 feet, 2020 m) in a notch that is 2 hours from the pass. This unforgettable descent offers views of the immense south face of Dhaulagiri to the north. There are plenty of facilities all along here. Reach Ghara (6000 feet, 1828 m), a sprawling settlement, less than 1 hour from Sikha.

Side Trip from Chitre to Khopra Ridge. There are now facilities to make a side tour to the high ridge north of Chitre that offers sensational, close-up views of Annapurna South (23,684 feet, 7219 m), Fang Peak (25,089 feet, 7647 m), as well as Nilgiri and Dhaulagiri. Trekkers rarely make this steep detour, and there is a real danger of altitude illness, as the lodging at Khopra Ridge is at 11,975 feet (3650 m).

Side Trip from Chitre to Khopra Ridge. There are now facilities to make a side tour to the high ridge north of Chitre that offers sensational, close-up views of Annapurna South (23,684 feet, 7219 m), Fang Peak (25,089 feet, 7647 m), as well as Nilgiri and Dhaulagiri. Trekkers rarely make this steep detour, and there is a real danger of altitude illness, as the lodging at Khopra Ridge is at 11,975 feet (3650 m).

The route from Chitre first traverses to Swanta and follows the ridgeline to Chistibang (10,170 feet, 3100 m) to rise above the treeline, reaching the sensational lookout point of Khopra Ridge. There is a community lodge in Khopra as well as wireless Internet, thanks to the efforts of Mahabir Pun, a local resident who has provided communication service to villagers in the area with side-benefits for tourists as well. A day’s trip toward Annapurna South reveals two small glacial lakes, Kalibaraha and Khairbaraha, which are tremendously scenic pilgrimage sites. Return to the main route by retracing your steps to Chitre, or follow the ridgeline to the west and then south down to Paudar and on to the main route near Ghara. It may be possible to travel to Narchyung to the north of Tatopani and meet the route to Jomosom on the east side of the Kali Gandaki near the Miristi Khola, but it would be useful to hire a local guide.

Continue through a notch now called Durbin Danda (“binocular ridge”), and descend steeply to the south (left) bank of the Ghara Khola. Cross it on a wooden bridge (3850 feet, 1173 m) and reach the few houses called Ghara Khola above the junction of the Ghara Khola and the Kali Gandaki. As the junction of two rivers, this area is sacred and has a little temple below. The trail to Beni continues south following the Kali Gandaki downstream, but you should head upstream, cross the Kali Gandaki on a suspension bridge (3970 feet, 1210 m), and go on to Tatopani (3900 feet, 1189 m), 1½ hours from Ghara. Nilgiri is the summit in the valley floor, and the photograph of it silhouetted by porters crossing the old suspension bridge here graced the covers of the first and only coffee-table book on Nepal for decades. If you head up to Kagbeni, you will go around Nilgiri to the north side.

In September 1998, a large landslide dammed the Kali Gandaki south of Tatopani for 7 hours. Water levels rose, flooding several homes before the Kali Gandaki cut a passage through the western end and waters receded.

Tatopani, a prosperous Thakali town, takes its name (taato paani, literally “hot water”) from the hot springs located along the banks of the river, near the middle of town, just below the motor road. There are currently two pools, and a usage fee is required. Don’t foul the water with soap, even though some locals may. Wash in the effluent below the pools or in the river, rinse, and then soak in the hot water. Be discreet and modest, as the Nepalis are.

There is another hot springs located on the other, east side of the river. The built-up pool area can be seen across the river from the upper, north end of Tatopani. Reach a bridge to the other side by traveling upstream along the road for 20 minutes. Cross the suspension bridge (4200 feet, 1280 m) and return downstream on the other side for 20 minutes to the bathing area, used mainly by locals.

To escape a section of the road, after 20 minutes of following the road north from Tatopani, cross a suspension bridge (4200 feet, 1280 m) to the east side of the Kali Gandaki. Pass by a few teahouses and contour up the river, staying to the left before passing just above a school. Stay left again to cross to the north side of the Miristi Khola on a suspension bridge (4373 feet, 1333 m) about 40 minutes after crossing the Kali Gandaki. Ascend to a small plateau before descending to Patar (4396 feet, 1340 m) in 15 minutes. There are no facilities in Patar.

Beyond Patar, the trail passes through a bluff and descends to a suspension bridge in 15 minutes. Do not cross the bridge here but stay on the east bank of the Kali Gandaki and contour past a hydropower project to reach Garab (4478 feet, 1365 m) in 5 minutes, 1 hour 35 minutes from Tatopani. There are shops, and simple lodging may be available here, too. Continue contouring along the river, eventually passing another suspension bridge before ascending up to Gadpar (4823 feet, 1470 m) in 40 minutes. Ascend to the few houses of Bhalebas (5633 feet, 1717 m) in 40–45 minutes, with a grand vantage point of the waterfall across the river. There are no facilities in Bhalebas or Gadpar. Descend to reach Kopche Pani in 20–25 minutes, 1¾ hours from Garab, across the river from Rupse Chhaharo and along the east-side route described below.

THE KALI GANDAKI VALLEY—A GREAT BIOGEOGRAPHIC DIVIDE |

When trekking up the Kali Gandaki valley to the Thak Khola, you experience changes in flora and fauna that are more dramatic than anywhere else in Nepal. For example, in one day you can descend from the arid Tibetan steppe flora at Tukche through temperate coniferous forests to reach the humid subtropical zone around Tatopani. The Kali Gandaki has cut the world’s deepest river gorge right through the Himalaya. The river runs from the Tibetan plateau to the north, through almost the center of Nepal and the middle of the Himalaya. |

The valley is a biogeographic divide for Himalayan flora and fauna. Forests to the west of the valley are generally drier and have fewer plant species than eastern forests. In their field guide Birds of Nepal, the Flemings point out that the Kali Gandaki is a very distinctive break in bird distribution. Some species, such as the fire-tailed myzornis and the brown parrotbill, are restricted to the valley and farther east, while others, the cheer pheasant for instance, only breed in the valley and westward. Forests to the east of the valley are significantly richer in bird species than western forests, even taking into account that western forests are relatively poorly recorded.  |

The view north from Tatopani up the Thak Khola valley includes Nilgiri as well as a road plied by buses and other vehicles. (Photo by Tokozile Robbins)

Alternatively, from Tatopani, you can simply follow the motor road on the west (right) bank of the Kali Gandaki and pass through Sukebagar to Dana (4600 feet, 1402 m) by the Ghatte Khola. This wealthy, stretched-out former customs post is reached in about 1½ hours from Tatopani. In the lower end of Dana you can see the spectacular west face of Annapurna. It took Stephen five trips before the clouds cleared enough to see it. Continue on the west (right) bank to Titar, and then climb to the few houses of Rupse Chhaharo (5350 feet, 1631 m), named after the waterfall above the bridge. Rupse Chhaharo is reached in 1¼ hours from Dana. Note the appropriate-technology water mills here.

There are two route choices here: the east (left) or the west (right) bank. The east-side trail is currently the more used and is probably safer in the monsoon, but inquire locally about conditions. Trekkers have perished, slipping on this path. The west-side route follows the road.

To follow the east-side trail between Rupse Chhaharo and Ghasa, fork right just after the bridge at the waterfall. Descend to cross the Kali Gandaki on a bridge (5360 feet, 1634 m) at a narrow point in the gorge. Head upstream, keeping close to the powerful torrent, now chocolate brown carrying sand and soil south. Reach Kopche Pani, with several small clusters of teahouses (5500 feet, 1676 m), in 30 minutes. A further 1 hour’s steep climb from Kopche Pani brings you to Pahiro Tabla (meaning “landslide place,” 6400 feet, 1897 m). As you go along, look for the old trail on the west side and the ancient pilgrim trails above it. Pilgrims traveled this dangerous route to Muktinath as long ago as 300 BCE. Along the way, you may see monkeys in the forests. In another 45 minutes, reach the suspension bridge and trail junction (6400 feet, 1910 m) 15 minutes below Ghasa.

On the west-side route along the road, climb above the teahouses of Rupse Chhaharo to reach Kabre (5600 feet, 1750 m) in less than 30 minutes. Kabre is the northernmost village inhabited by hill castes in the Kali Gandaki valley. From Kabre, continue north along the steep cliff side to where the valley narrows spectacularly and the cascading river torrent resounds across the canyon walls. Probably the world’s steepest and deepest large gorge, the gradient to the summit of Dhaulagiri is more than 1 mile (1.6 km) vertical to 1 mile (1.6 km) horizontal (1:1.05 to be exact). The steepest part, however, is south of the line between the two summits. The east-side trail rejoins the road 2 hours from Kabre and 15 minutes south of Ghasa.

AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES OF THE SUBTROPICAL ZONE |

Nepali amphibians and reptiles are primarily found in the warmer tropical and subtropical zones (3300–6500 feet/1000–2000 m in the west, to 5500 feet/1700 m in the east). Over thirty-six species of amphibians, including frogs (bhyaguto), toads, newts, and a caecilian, have been recorded so far. One of the commonest is the aptly named skittering frog (Rana cyanophlyctis), which can float and skip over the water surface. The six-fingered frog (Rana hexadactyla) is the largest Nepali amphibian. Not aquatic, it is reported to feed on mice, shrews, birds, and lizards. In the breeding season it calls deep “oong-awang” throughout the night. Reptile species include crocodiles, turtles, lizards, skinks, and geckos. Snakes (sAAp, sarpa) are elusive; most are nonpoisonous. One of the commonest is the buff-striped keelback (Amphiesma stolata), which occurs in grassy areas near cultivation. It is olive-green or brown above with black spots or bars intersected with buff stripes. Lizards (chhepaaro) are more obvious and can often be seen basking in the sun on stone walls or rocks. A familiar lizard is the Himalayan rock lizard (Agama tuberculata). It is coarsely scaled, has a long tail, and is generally colored brown with black spots; breeding males have blue throats.  |

It takes 30 minutes to get through Ghasa (6700 feet, 2040 m), a sprawling, flat-roofed Thakali village with an ACAP Safe Drinking Water Station. (In reverse, traveling from Ghasa to Dana, avoid the trail that heads left immediately after leaving lower Ghasa. It leads to an unused bridge and path. Instead follow the road for 15 minutes and then cross to the east bank on a suspension bridge.)

Note how remarkably the land has changed over this short stretch, as the climate becomes colder and drier. To the south, you may see lizards throughout the year, but from here northward none are seen in the cold season. Similarly, as you head north, you will encounter more pine forests and fewer broad-leaved trees. Most houses beyond here have flat roofs because there is less rainfall. The changes will be even more dramatic farther along. Be careful not to twist your ankle on the river-worn trail boulders.

To continue north from Ghasa, cross a tributary, and pass through Kaiku and the few houses of Gumaaune (literally “walking around”). There is a huge landslide scar on the east side. Reach a bridge over the Lete Khola (8000 feet, 2438 m), a tributary from the west, and cross it to a lodge. Lete (8100 feet, 2469 m), some 30 minutes beyond, is 2 hours from Ghasa. Annapurna I, the first 8000-meter peak ever climbed, can be seen to the east from Lete. Again, note the change in ecology; Lete gets 49 inches (124 mm) of rain a year, whereas a mere half day to the north, Tukche gets only 8 inches (20 mm).

A trip is described below from Lete east to the original Annapurna Base Camp. This hard-found camp was the base for the French expedition that accomplished the first ascent of an 8000-meter peak, Annapurna (26,545 feet, 8091 m), in 1950. From Lete, the route is a strenuous 5-day camping trip to substantial altitudes where food, fuel, and shelter must be carried. See “Explore: North Annapurna Base Camp” later in this chapter for more details.

Heading north, pass the police check post in the spread-out village of Lete, which then blends into Kalopani (8300 feet, 2530 m). Sunsets from Kalopani and Lete are memorable. The Cultural Thakali Museum is in Kalopani next door to the ACAP Safe Drinking Water Station.

A few minutes north of Kalopani, take the suspension bridge (8251 feet, 2515 m) over the Kali Gandaki/Thak Khola to the east side. The trail passes through Dhampu to reach Dada (8383 feet, 2555 m) in 30 minutes. A trail up to Titi village with a nearby small lake leads off from here. Continue on to KokheThAATi (8300 feet, 2530 m) in less than 10 minutes before crossing back to the west (right) bank in another 20 minutes. In less than 15 minutes more, reach the broad Ghatte/Boxe River delta. In the dry season, you can head straight across the delta with minimal wading to meet the road on the other side and follow it to reach Larjung (8400 feet, 2570 m) in 30 minutes or 1¾ hours from Kalopani. (If wading is not possible, then head up the tributary valley to a suspension bridge [8317 feet, 2535 m] over the Boxe Khola.) There is an ACAP Safe Drinking Water Station in Larjung and many walnut trees in both Larjung and Khobang.

To the west is the incredibly foreshortened summit of Dhaulagiri, almost 3.5 miles (5.5 km) higher. The temples above Larjung are where the local deities are kept for Thakali clans residing here. There is a festival honoring them every twelve years. Bhurjungkot lies to the west above Khobang and Larjung. A trail to the village heads west from the lower, southern end of Larjung, reaching Bhurjungkot in 30 minutes. A cave said to be used by Padmasambava lies a few hours north of this village.

Side Trip from Larjung to Dhaulagiri Icefall. This can be made in a long, full day trip involving 3940 feet (1200 m) of ascent with no facilities en route. To get to the trailhead, retrace your steps from Larjung, heading down the Kali Gandaki, and after 30 minutes reach the broad Ghatte/Boxe River delta. Rather than wade across the delta, head up the valley to a suspension bridge (8317 feet, 2535 m) over the Ghatte/Boxe Khola. Cross the bridge and, after a few minutes following the road downriver, you will see a trail (indicated by an ACAP sign) on the right that leads to Bhuturcho Lake, a small body of water 30 minutes above the road. However, continue following the road and just after crossing a tributary, there is an ACAP sign indicating the trail to the right leading up to Sekong Lake and on to Dhaulagiri Icefall. It may be best to hire a local guide. The area below the icefall (12,400 feet, 3780 m) can be visited in a very long day, but it’s better to camp and enjoy the sunrise and sunset. The area below the east Dhaulagiri Icefall abounds with yak pastures and was the location of the 1969 American Base Camp. At a lower altitude than Dhampus Pass, it has correspondingly less severe conditions. The views of the mountains are excellent, possibly better than at Dhampus Pass. Beware of avalanches in the vicinity of the icefall.

Side Trip from Larjung to Dhaulagiri Icefall. This can be made in a long, full day trip involving 3940 feet (1200 m) of ascent with no facilities en route. To get to the trailhead, retrace your steps from Larjung, heading down the Kali Gandaki, and after 30 minutes reach the broad Ghatte/Boxe River delta. Rather than wade across the delta, head up the valley to a suspension bridge (8317 feet, 2535 m) over the Ghatte/Boxe Khola. Cross the bridge and, after a few minutes following the road downriver, you will see a trail (indicated by an ACAP sign) on the right that leads to Bhuturcho Lake, a small body of water 30 minutes above the road. However, continue following the road and just after crossing a tributary, there is an ACAP sign indicating the trail to the right leading up to Sekong Lake and on to Dhaulagiri Icefall. It may be best to hire a local guide. The area below the icefall (12,400 feet, 3780 m) can be visited in a very long day, but it’s better to camp and enjoy the sunrise and sunset. The area below the east Dhaulagiri Icefall abounds with yak pastures and was the location of the 1969 American Base Camp. At a lower altitude than Dhampus Pass, it has correspondingly less severe conditions. The views of the mountains are excellent, possibly better than at Dhampus Pass. Beware of avalanches in the vicinity of the icefall.

From Larjung, head north, cross a tributary, and in a few minutes enter the fascinating town of Khobang (8400 feet, 2580 m). The trail used to pass through a tunnel, and doors to the houses opened off it. The village was thus protected from the strong winds that blow up the valley almost every afternoon. The northern, open segment of the series of settlements is called Kanti. The dry-season path keeps closer to the river. Cross another tributary, either on a temporary bridge or upstream on a more substantial one. Tukche (8500 feet, 2591 m), an historically important town, is 1 hour beyond Khobang. There is an ACAP Safe Drinking Water Station here.

Tukche was once an important center for the trade of Nepali grain for Tibetan salt through the valley of the Thak Khola. Thakali Subbha, or customs contractors, controlled it and exacted taxes at Tukche in the summer and at Dana in the winter. The handsome architecture and great woodcarving in Tukche attests to the importance of this town. By the middle of this century competition had reduced this trade, and the enterprising Thakali turned their attention south and became more involved in business ventures around Pokhara and in the Tarai. Their spread throughout many of the trade routes in Nepal resulted in the establishment of many bhaTTi, even before trekking became popular. With the coming of foreigners, the Thakali developed hotel facilities for them, and many of their family homes have been developed into lodges. Try to find a traditional bhaTTi and sample a good Nepali meal of daal bhaat tarkaari (lentils, rice, and vegetables) or at least have such a meal in a tourist restaurant.

PHEASANTS OF THE TEMPERATE ZONE |

Nepal is famous for its variety of Himalayan pheasants. There are six species, all of which can be seen in the Annapurna Conservation Area. Most are shy and difficult to see unless you flush them from the forest. They call frequently in spring. The Kalij pheasant (Lophura leucomelana), or kaali (length 24–27 inches, 60–68 cm), inhabits all types of forest with dense undergrowth, especially near water, and also occurs in subtropical and tropical zones. The male is mainly black with a long tail and red on the face; the female is reddish brown with a shorter tail. The Koklass pheasant (Pucrasia macrolopha, or phokraas (length 20–24 inches, 52–61 cm), inhabits oak and conifer forests from the Modi Khola valley westward. The male is dark, with a long crest and tail, black head, and white ear patch. The female is brownish, with a shorter crest and tail. It crows loudly at dawn. The satyr tragopan, or crimson-horned pheasant (Tragopan satyr), or munaal (length 23–27 inches, 59–68 cm), is found in damp oak and rhododendron forests with dense undergrowth. The male is bright red, spotted with white and with a blue wattle; the female is mottled brown. In spring, it makes a strange, mammalian “waaa” noise at dawn and dusk.  |

The Thakali seem to prosper in whatever they turn to. In comparing his visits to this region twenty years apart, Stephen found the improvements impressive—water systems, latrines, more schools (indeed, functioning schools), better trails, more varieties of crops, and cleaner homes. The Thakali have always exhibited a strong ethnic group consciousness, and Thak Khola is their homeland. Many of the towns have been electrified through the installation of a mini-hydroelectric generator across and up from Khobang on the Chhokopani Khola, which produces 260 kilowatts. Visit the active gomba at the northeast end of town and tour the distillery (the first of many to the north).

A strong wind blows from the south up the valley, beginning in the late morning and lasting most of the day. This is caused when the air mass over the plateau to the north warms, rises, and creates a pressure difference. The best time to head south is in the early morning when the wind may be from the north. As you go up the valley from Tukche, notice that there is relatively little vegetation on the valley floor itself, but there are trees and forests on the walls. The valley floor is in a rain shadow due to the strong winds. When the wind is blowing, you may notice that there are no clouds over the center of the valley, but clouds do hang on the sides.

Side Trip to Dhampus Pass and Hidden Valley (visitors must be acclimatized and self-sufficient to travel into the Hidden Valley). A trail to Dhampus Pass goes up the hill to the west of the gomba (monastery) at Tukche (another trail departs from Marpha). Dhampus Pass (17,000 feet, 5182 m) connects the valley of the Thak Khola with Hidden Valley. Semiwild yak herds, snow leopards, and blue sheep might be encountered in Hidden Valley. It lies beyond the treeline and is often snowed in. Huts used for pasturing yaks can be used for shelter and cooking en route to the pass. There are no facilities at the pass. Carry food, fuel, and shelter. Temperatures below freezing can always be expected, and in the winter months the temperature drops below 0°F (–18°C). A trip to the pass is ideal for those who want a more vivid experience of being in the mountains.

Side Trip to Dhampus Pass and Hidden Valley (visitors must be acclimatized and self-sufficient to travel into the Hidden Valley). A trail to Dhampus Pass goes up the hill to the west of the gomba (monastery) at Tukche (another trail departs from Marpha). Dhampus Pass (17,000 feet, 5182 m) connects the valley of the Thak Khola with Hidden Valley. Semiwild yak herds, snow leopards, and blue sheep might be encountered in Hidden Valley. It lies beyond the treeline and is often snowed in. Huts used for pasturing yaks can be used for shelter and cooking en route to the pass. There are no facilities at the pass. Carry food, fuel, and shelter. Temperatures below freezing can always be expected, and in the winter months the temperature drops below 0°F (–18°C). A trip to the pass is ideal for those who want a more vivid experience of being in the mountains.

Reach the pass from Tukche or Marpha by going to some yak huts (13,000 feet, 3962 m) the first day and to the pass the second. This may be too rapid an ascent for many people. If you are unprepared to spend a night at the pass, you could go up and return to the yak huts in a day. Yak yogurt is delicious—during the warm season you should try to buy some at the herders. If there is any possibility of cloudy weather, hire a local person from Tukche (or Marpha) as a guide. Once clouds settle in, it is very easy to get lost.

A recommended alternate route exists from Tukche to Thini, the village that overlooks Jomosom. This route avoids much of the road while passing through the magnificently set village of Chimang and the Tibetan refugee camp of Chairo. To take this route, about 40 minutes from Tukche cross a suspension bridge (8573 feet, 2613 m) over the Thak Khola (which is the name of the Kali Gandaki north of Ghasa). To the right, across a broad alluvial fan, is the small village of Chhokopani, believed to be a source of holy waters and religiously important to Thakalis. Instead, head left and in 25 minutes cross the Chimang Khola just upstream on a variable bridge. Ascend to the village of Chimang (9131 feet, 2783 m), surrounded by orchards, in another 20 minutes, less than 1½ hours from Tukche. There are no lodges here.

Continue on 15 minutes to where the trails from upper and lower Chimang meet. After 15–20 minutes you reach another trail junction; stay with the middle path to reach Chairo, set among tall juniper trees 45–50 minutes from Chimang. It is a Tibetan refugee camp and no boarding is available unless permission is first taken from ACAP.

To reach Marpha from Chairo, cross a bridge over the Thak Khola and head upriver for 20 minutes to Marpha (8825 feet, 2690 m) on the west bank. Otherwise, to continue avoiding the motor road, stay on the east bank from Chairo and contour before ascending steeply to pass above bluffs. Descend steeply to reach a tributary riverbed (9186 feet, 2800 m) and cross this delta in 2 hours from Chairo. Ascend past the village of Dhumbra to a ridgecrest (9498 feet, 2895 m) in 15 minutes. There is an oft-closed gomba nearby. Descend to Dhumbra Lake (9297 feet, 2834 m) in 15 more minutes. This lake is considered to be sacred, and a local lama prohibits access to its waters. Descend through the village of Samle to reach a bridge (9071 feet, 2765 m) over a tributary in 20 minutes. Ascend to the village of Thini (9383 feet, 2860 m) in 20 more minutes, some 3 hours 10 minutes from Chairo. There are no lodges here. Jomosom lies 20–25 minutes below.

Ammonite fossils or shaligram can be found in the area north of Jomosom and are highly prized by pilgrims as a symbol of the Hindu deity Vishnu. (Photo by Tokozile Robbins)

Rather than the alternate route outlined above, most people will stay on the west bank from Tukche all the way to reach Marpha (8825 feet, 2690 m) in 1½ hours. About 15 minutes before Marpha, pass by the Marpha Agricultural Farm, which has introduced many of the new crops you see around. Marpha, a charming town, has a fine sewer system—a series of canals flowing down the streets. There are plenty of choices for accommodation and food here, especially given the variety of fruits and vegetables available. Some of the hotels here, and also in Jomosom, advertise pony rides as far as Muktinath. Visit the new large gomba in the center of town. There is an ACAP Safe Drinking Water Station here, too. Dhampus Pass can also be reached from Marpha.

To continue upstream, leave the town through the chorten and cross first a tributary and then the Pongkyu Khola, another alluvial fan, with a water mill, that flows from the west. Along the trail you will see willow plantations, part of a reforestation project. The town of Syang is beyond, and its monastery is up the hill a bit farther. On certain days during late October to early December, monks stage dance festivals in the gomba of Marpha, Syang, and Tukche that are somewhat similar to the Mani-rimdu festivals of Solu–Khumbu. Consider a side trip east across the river to the gomba on the hillock with its commanding views of the valley.

Cross a tributary farther up the valley, and reach Jomosom (8900 feet, 2780 m), the capital for the Mustang District, 1½ hours from Marpha. There are many facilities here and an ACAP Safe Drinking Water Station and ACAP Information Center. There is an airfield here with scheduled service to Kathmandu, but because of the erratic winds service can be unreliable. Winter winds regularly reach 30 to 40 knots, with gusts to 70! If you fly in and head upvalley to rarefied air, beware of altitude illness. Other attractions include banks, a hospital, rather luxurious accommodations and food, climbing cliffs with a welcome sign, and, of course, a police check post. An ecomuseum has opened at the southern end of town and has informative displays. This town has prospered immensely over the years and has expanded to both sides of the river to provide space for the many government employees and offices. Pony caravans used to bring food to Jomosom to feed the bureaucracy but are being replaced by vehicular transport.

The countryside to the north is very arid, not unlike the Tibetan plateau farther north. To the south, Dhaulagiri impressively guards the Thak Khola valley. It is much less foreshortened than at Larjung. To the east, across the river on a shelf of land, is the traditional town of Thini (9500 feet, 2897 m), reached in 30 minutes from Jomosom. The inhabitants are technically not Buddhists (though they may say otherwise) but followers of Bon-po, the ancient religion that antedated Tibetan Buddhism.

Up the valley east of Thini is Tilicho Pass and Tilicho Tal. The latter, at 16,140 feet (4919 m), is a high, spectacular lake. It is better to access this area from the west not only because the trail is clearer and there are facilites en route on that side but because you start higher and are more likely to be acclimatized. Additionally, a Nepali army camp on this side of the pass, used for mountain warfare training, might restrict some of the route. You might have noticed their “R&R” facilities in Jomosom.

To continue on to Kagbeni and Muktinath, travel on the east (true left) side of the river. The perennial high wind gusts strongly down the riverbed, which can be half a mile wide here; sunglasses or other eyewear and a mask or bandanna to cover the nose and mouth can be useful to protect against airborne dust particles. In 1½ hours reach the trail junction of Eklai BhaTTi (also known as Chyancha-Lhrenba) at 9186 feet (2800 m). Eklai BhaTTi means “lonely inn,” which bespeaks a former time as there are now several lodges. If traveling to Kagbeni, the suspension bridge just south of Eklai BhaTTi leads to a west bank route that avoids a section of the road. Another alternative to following the road is to head east up the Panda Khola valley (15 minutes south of Eklai BhaTTi) to Lubra. The route from Lubra to Muktinath is described below in reverse.

From Eklai BhaTTi, the route to the left continues up the river to the captivating village of Kagbeni (9383 feet, 2860 m) in just over 30 minutes, while the right ascends out of the valley and heads more directly to Muktinath. The right branch reaches the junction (10,350 feet, 3155 m) of the trail from Kagbeni to Muktinath in 1¼–1½ hours.

Muktinath, located in a poplar grove, is a sacred shrine and pilgrimage site for Hindus and Buddhists. The Mahabharata, the ancient Hindu epic written about 300 BCE, mentions Muktinath as Shaligrama because of its ammonite fossils called shaligram. Brahma, the creator, made an offering here by lighting a fire on water. You can see this miracle (burning natural gas) in a small Buddhist shrine (gomba) below the main Hindu temple (mandir). Many people from Mustang and other areas come to sell handicrafts to the pilgrims. Some sell the shaligram, the mollusk fossil dating from a period roughly 140 to 165 million years ago before the uplifting of the Himalaya. These objects, treasured for worship by Hindus, are said to represent several deities, principally those associated with Vishnu, the Lord of Salvation. You are apt to find them along the flats north of Jomosom and for sale in Baudha, Kathmandu. You are not allowed to export them, however. |

Hindus named the site Muktichhetra, meaning “place of salvation (mukti),” because they believed that bathing there gives salvation after death. Springs are piped into 108 brass water spouts in the shape of boars’ heads near the temple dedicated to Vishnu, the focal point for Hindus. The boar was the third incarnation of Vishnu. Because Buddha was the ninth avatar, the Hindus tolerate the Buddhists here. The Buddhists consider the image of Vishnu in this typically Newar-style temple as the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshwara. Vishnu is in the shape of an icon as well as a large ammonite fossil. The same fossil image is worshiped by Buddhists as Gawa Jogpa, the “serpent deity.” |

The miraculous fire revered by Buddhists and Hindus burns on water, stones, and earth, and is inside the Jwala Mai Temple (also called the Salamebar Dolamebar Gomba or Mebar Lhakang Gomba), south of the police check post. Natural gas jets burn in small recesses curtained under the altar to Avalokiteshwara. On the left burns the earth, in the middle water, and on the right the stone. One flame has died out; only two remain lighted. Sherpas and Buddhist porters with you may ask you for a bottle to take some of the “water that burns” with them. It is traditional to leave a small offering of money. |

Padmasambhava, who brought Buddhism to Tibet in the eighth century, is believed to have meditated here. His “footprints” are on a rock in the northwest corner of this sacred place. On their way to Tibet, the eighty-four siddha (“great magicians”) left their pilgrim staffs, which grew into the poplars at the site. You will find many old chorten and temples cared for by Nyingmapa nuns or old women from the nearby villages. A full moon is an especially auspicious time to visit Muktinath. In the full moon of August–September, thousands of pilgrims arrive.  |

The name Kagbeni aptly reflects the town’s character—kak means “blockade” in the local dialect and beni means “junction of two rivers”—and this citadel does effectively block the valley. River junctions are often considered especially sacred to the people living nearby. Since the town is at the confluence of trails from the north, south, east, and west, the ancient king who sat here could control and tax the exchange of grain from the south and wool and salt from the north. The ruins of his palace, which can still be seen, are a reminder of the ancient kingdoms that predated the unification of Nepal. Some scholars believe the family that ruled here was related to the ancient kings of Jumla. The Sakyapa monastery here charges an entry fee for a visit. You may see two large terra-cotta images of the protector deities of the town—a male at the north end and the remains of a female at the south. This mingling of old animistic beliefs with those of the more developed religions is common in Nepal.

A mendicant fakir’s offerings (Photo by Tokozile Robbins)

People here call themselves Gurung but are clearly not the same as the Gurung to the south. People from Tibet who have settled in Nepal often call themselves Gurung to facilitate assimilation.

The impressive folding of the cliffs west of town illustrates the powerful forces of orogeny (discussed in Chapter 1’s geology section). There is a viewpoint called Sher Dhak several hundred meters above on the opposite side of the river. It involves a steep scramble up loose rock. From Kagbeni, you can just make out the crest of Thorung La up the valley to the east of town, with Kagbeni visible from the pass, too. There is an ACAP Safe Drinking Water Station as well as a police check post in Kagbeni, at the northern limit for trekkers.

North of Kagbeni is the Upper Mustang restricted area and the kingdom of Lo. Permits to enter can be obtained at the Immigration Office in Pokhara or Kathmandu; the cost is $500 USD per person for the first 10 days and $50 USD per day thereafter. Additionally, the trip must be guided and arranged through a registered trekking company. However, it is possible, without a restricted area permit, to visit the fascinating village of Tiri a short distance north on the opposite (west) bank of the Kali Gandaki. A road is being built to Tiri (and beyond); to hike there, from the lower end of Kagbeni, cross the bridge (9334 feet, 2845 m) to the true right/west bank of the Thak Khola and traverse north. Reach Tiri (9439 feet, 2877 m), a village surrounded by walled orchards, in 25 minutes. A gomba is perched above town. Continuing north of Tiri is restricted.

To travel to Muktinath from Kagbeni, head up from the Jhong Khola, the tributary from the east, following the road for the most part, with some sections of trail away from the road.

Continue east, noting the caves on the north side of the valley. So ancient are these caves that no one remembers if they were used by hermits or troglodytes. On a clear day, the walk can be ethereal, as the dry valley sparkles and the north wall seems suspended close to you. Climb to Khingar (11,190 feet, 3410 m) in 2 hours; the old part of town is north of the trail. Continue to Jharkot (11,715 feet, 3570 m) in 40–45 minutes more, a crumbling but still impressive fortress perched on a ridge. Jharkot, called Dzar by Tibetans, is believed to have been the home of the ruling house of this valley. Note how some houses around the ruins of the fort are made of blocks of earth.

Go on to what is now called Muktinath, also known as Ranipawa (12,047 feet, 3672 m), with a large rest house for pilgrims, many hotels, a police check post, and an ACAP visitor center office you should visit to register your name. The office is 30–40 minutes from Jharkot. If your intention is to cross the Thorung La from this side, then check with the ACAP information center here, as they may advise you against proceeding in marginal conditions.

Across the valley you can see the extensive ruins of Dzong (“castle” in Tibetan) and the town built around it, the original seat of the king of this valley. Consider a side trip to that side of the valley, outlined below.

The wall-ensconced compound of the holy shrine of Muktinath is less than 15 minutes from the ACAP center. Dhaulagiri (26,795 feet, 8167 m) looms impressively to the south. It was first climbed from the north, the view you see here, by a German expedition in 1960. The Muktinath Foundation International supports the interfaith aspect of the region and has a website, www.muktinath.org.

To the east is Thorung La (17,700 feet, 5416 m), which leads to Manang and the eastern half of the Annapurna Circuit.

Crossing the pass from Muktinath to Manang is more difficult than crossing in the other direction. The only lodges between Muktinath and the pass (clockwise) are at Chaharu (also known as Phedi) at 13,687 feet (4172 m), whereas there are lodges up to 15,990 feet (4875 m) on the Manang side and seasonal tea shops beyond. It is a very long day to ascend from Chaharu to the pass and then to descend to facilities on the other side. Additionally, in the dry season there are few if any suitable campsites with water on this side of the pass.

Altitude illness may jeopardize those who are unacclimatized. Crossing from Manang, on the other hand, is easier because of the comparatively long time spent at high altitudes before approaching the pass. Most people start at Besisahar and follow the Marsyangdi valley to Manang before crossing to the high Thorung La over to Muktinath and the Kali Gandaki/Thak Khola valley. The pass is often crossed from Muktinath, but it certainly is more difficult and hazardous. Under no condition should you ascend from either direction unless the entire party, including porters, is well equipped to camp in snow should a storm arise. The trail descriptions for the Manang to Muktinath crossing are given with the Manang section later in this chapter.

Side Trip from Muktinath to Chaungar, Dzong, and Beyond. A short excursion from Muktinath across the valley to the beautiful villages of Chaungar and Dzong (Jhong) provides a glimpse of life outside the tourist areas. This trip can be made out and back on the same path, less than 30 minutes each way. Alternatively, it can be made into longer excursions as the following three circuit routes: crossing the valley from Dzong to Jharkot and back to Muktinath (2½-hour loop), crossing the valley from Puthak to Khingar and returning to Muktinath (3½–4 hours), or continuing all the way to Kagbeni on that side of the valley (3½ hours) and returning along the road. All of the above will be described.

Side Trip from Muktinath to Chaungar, Dzong, and Beyond. A short excursion from Muktinath across the valley to the beautiful villages of Chaungar and Dzong (Jhong) provides a glimpse of life outside the tourist areas. This trip can be made out and back on the same path, less than 30 minutes each way. Alternatively, it can be made into longer excursions as the following three circuit routes: crossing the valley from Dzong to Jharkot and back to Muktinath (2½-hour loop), crossing the valley from Puthak to Khingar and returning to Muktinath (3½–4 hours), or continuing all the way to Kagbeni on that side of the valley (3½ hours) and returning along the road. All of the above will be described.

From the upper end of Muktinath/Ranipawa, proceed north to Chaungar (12,110 feet, 3692 m), reached in an easy 25 minutes. There are no facilities in Chaungar, but there is lodging in Dzong, which lies down the valley from Chaungar. Descend from Chaungar to cross a suspension bridge (11,920 feet, 3632 m) to the west bank of a tributary and reach Dzong (11,750 feet, 3580 m) in under 30 minutes. This village was the seat of an ancient regime, and the remains of the old castle can be seen along the crest along with a gomba above which can be visited for a fee.

From Dzong you can retrace your steps to Muktinath, or complete a loop back to Muktinath by way of Jharkot across the valley. For the latter, descend through a grove of pipal trees to cross the Jhong Khola on a steel bridge (11,290 feet, 3440 m) in 20 minutes. Ascend through more pipal trees on the other side to the circuit trail just below Jharkot in 30 more minutes.

Otherwise, to continue down the valley, reach the village of Puthak (11,290 feet, 3440 m) in 20 minutes from Dzong. From Puthak, there is a route to link with Khingar (11,190 feet, 3410 m), across the valley to the southwest, in under an hour. This involves a steep descent to the Jhong Khola (10,780 feet, 3285 m) and then a steep ascent. However, check first locally to see if the bridge is operational.

If you would like to continue on down the valley, it is also possible to reach Kagbeni from Puthak along the motor road on this north side of the valley. It is a long and desolate stretch on what locals refer to as The Muktinath Ring Road; however, this road receives less traffic than the road on the opposite side of the valley. To head to Kagbeni on this side, 15 minutes below Puthak cross a suspension bridge (11,100 feet, 3382 m). Kagbeni is 2 hours from this bridge, with no facilities or water available along the way.

To return, follow the reverse of the trail descriptions for the trek from Pokhara to Muktinath, or follow the alternate route from Muktinath to Jomosom via pleasant Lubra village. This latter route avoids a large section of the motor road by heading over the high ridge to the southwest of Muktinath and descending to the Panda Khola valley, with a visit to the picturesque hamlet of Lubra. It involves a steep climb and steep descent but avoids the annoyance of vehicles for at least part of the way to Jomosom and meets the usual route south of Eklai BhatTTi. Check first with the ACAP information Center on the availability of bridges over the Panda Khola and fill up water in Muktinath, as there may not be another chance until Lubra, 3¼ hours away.

Buckwheat fields in the hamlet of Lubra along an alternate route between Jomosom and Muktinath (Photo by Tokozile Robbins)

Find the trail as it branches to the left from the road as you head out of the lower (western) end of Muktinath. In 20 minutes stay right at a trail junction. Stay right again 25 minutes beyond and ascend to reach a saddle (12,530 feet, 3820 m) in 30 more minutes, 1¼ hours from Muktinath. Contour shortly before descending steeply into the Panda Khola valley. Reach the riverbed (10,040 feet, 3060 m) in 1½ hours from the saddle.

The trail through the riverbed at the valley floor may be faint and is of variable condition; wading might be necessary depending on the season. Either cross a bridge that ACAP has planned to build to meet a trail on the other side of the valley from where you descended, or travel downstream along the valley floor to a seasonal bridge. Reach Lubra (9859 feet, 3005 m) in 30 more minutes. There are no tourist facilities here, but there are two (rarely encountered) monasteries of the Bon religion as well as a boarding school situated above the village. Across the Panda Khola from the village, meditation caves can be seen.

To continue on to Jomosom from Lubra, head down the valley. Reach a suspension bridge (9711 feet, 2960 m) in 15 minutes. Do not cross here but stay on the south side and traverse down to the valley floor (9547 feet, 2910) in another 15 minutes. Reach the Kali Gandaki valley (12,450 feet, 3795 m) in 40 minutes. Head left/south here to Jomosom, a further 1¼ hours away (2¼–2½ hours from Lubra).

This route from the Kali Gandaki valley to the original Annapurna Base Camp was discovered by the 1950 French Expedition that summited Annapurna led by Maurice Herzog. The French first tried to climb Dhaulagiri but found it beyond their capabilities and instead tried to find a way to the base of Annapurna. They had difficulty getting there from the Kali Gandaki, and the route still has a bad reputation. It is seldom used except by shepherds and mountaineering expeditions. However, in the relatively snow-free early fall and late spring, the route is neither very difficult nor dangerous. However, the trail is often indistinct and traverses steep grassy slopes. From Lete, it is a strenuous 5-day camping trip to substantial altitudes where food, fuel, and shelter must be carried. At certain times of the year, snow can make the trip almost impossible. Parties should be prepared for cold at any time of the year. It is always best to have someone along who is familiar with the route. Porters do not like this trail, but it is certainly no worse than little-used trails in many other areas of mountain wilderness.

YARTUNG FESTIVAL |

At about the same time as the major pilgrimage (Janai Purnimaa) to Muktinath in the full moon of August–September, local Tibetan villagers of the valley hold a great end of summer festival called Yartung—a time of horse racing, dancing, gambling, and general merriment. This is held on the race grounds of Ranipauwa, adjacent to the Muktinath pilgrimage site in the Mustang District. BhoTiya people from all over Bargee (the Muktinath or Dzong river valley) and Lo-Manthang (upper Mustang), and some from Manang (east of Mustang), Lamjung (southeast), and Dolpo (west), attend. The men of BaragaaU region compete in a day of horse racing, and other games. It is a raucous occasion spiced by drinking and gambling in tents set up on the hills around the small community below Muktinath. The day begins with processions of laymen and monks in colorful attire, some riding equally decorated horses, from each of the surrounding villages. The monks lead the processions to circle the Muktinath shrine, and women perform purification rites at the temple’s 108 water spouts. Yartung signals the return from the highlands of the animals, which are pastured in the lower valleys during the coming winter. Yartung annually attracts the majority of BhoTiya people from throughout upper Thak Khola, northern Mustang, and neighboring Manang District (over Thorung La). The participants wear their traditional ethnic dress.  |

The views along the way are supreme. As the trail climbs steeply out of the Kali Gandaki valley, the incredible gorge becomes more and more impressive. The views of Dhaulagiri and Annapurna from the crest of the ridge separating the Kali Gandaki from the Miristi Khola are breathtaking. From this perch (14,000 feet, 4267 m), some 7000 feet (2134 m) above the valley floor, you can appreciate just how high these mountains are. From the foreshortened view from Kalopani, it is hard to believe that Dhaulagiri is the sixth highest mountain in the world. If you venture beyond the base camp toward Camp One, on the north side of Annapurna, you can appreciate the impressive features of that side of the mountain.

You will want to get provisions in Lete for onward travel. There is a tea shop in Chhoya, but it is best to stock up in Lete for at least 5 days of self-sufficient travel. You might be able to hire someone from Chhoya to show the way. In times of high water, it may not be possible to cross the Miristi Khola and reach the base camp without building a bridge, an undertaking most trekkers prefer to avoid. If a recent expedition has been on Annapurna, the chance of finding a usable bridge is good. Check beforehand to find out if there has been a recent expedition. In low water, the river can be forded with some difficulty downstream.

If you are coming from the south, turn right off the road 20 minutes aft er crossing the Lete Khola on a suspension bridge. In 10 minutes more cross the tumultuous Kali Gandaki on a suspension bridge (7890 feet, 2405 m) to reach Chhoya (8000 feet, 2415 m). If you are coming from the north, across from the Primary Health Center in upper Lete, take a left fork. This left fork takes you through a beautiful pine forest before you descend slightly in 20 minutes to the same suspension bridge to Chhoya.

From Chhoya the right (east) fork heads to North Annapurna Base Camp via Jhipra Deorali. The left fork heads to Taglung, Kunjo, and on to Titi village/lake. To head to North Annapurna Base Camp, cross the delta of the Polje Khola and ascend to the few houses of Poljedanda (8175 feet, 2492 m). Then turn right and head southeast to a few more houses of Jhipra Deorali (8275 feet, 2522 m) 30 minutes from Chhoya. This is the last village on the route. Here the trail forks left and you contour above fields to enter the valley of the Tangdung or Bhutra Khola, a little more than 30 minutes later. Contour below a small waterfall of a tributary to the main river (8075 feet, 2461 m) after a short, steep descent through forest, 1¼ hours from Deorali. There should be a bridge here unless it has been washed out during the monsoon. Fill up all your water containers, as you may not get another chance during the next day.

The next section of the trail is exceptionally steep. There are few suitable campsites until near the end of the climb. There are occasional vistas to inspire the weary. In 2–2½ hours, reach a saddle called Kal Ghiu (11,000 feet, 3383 m), although some trekking groups call this place Jungle Camp. Camping is possible here if you can find water down the other side of the saddle. Keep close to the crest of the ridge as you pass several notches. Enjoy the rhododendrons in bloom in the spring. After keeping to the southeast side of the ridge and leaving the forest, the trail becomes fainter, reaches a minor ridge crest (12,600 feet, 3840 m), and crosses over to the northwest side. Keep climbing to a prominent notch with a chorten (13,350 feet, 4069 m), some 2 hours from Kal Ghiu. The views of Dhaulagiri are unforgettable.

The slope eases off now and continues over more moderate grazing slopes to a place near a ridge crest called Sano Bugin (13,950 feet, 4252 m), where herders stay during the monsoon. There are rock walls here that the herders convert to shelters with the use of bamboo mats. If there is no snow to melt, water may be difficult to obtain. The gigantic west face of Annapurna, first climbed by Reinhold Messner in 1985, is before you. Head north along the ridge crest, or on the west side. The trail is marked with slabs of rock standing on end. In 1 hour, reach another ridge crest (14,375 feet, 4382 m) and cross to the southeast side of the ridge. This may be the “passage du avril 27” that Herzog’s expedition discovered in order to get to the base of Annapurna. You are now in the drainage area of the Miristi Khola, the river that enters the Kali Gandaki above Tatopani.

Continue contouring for a few minutes to Th ulo Bugin (14,300 feet, 4359 m), where seasonal herders stay. There is a small shrine here. Contour, crossing several tributaries of the Hum Khola, a tributary of the Miristi. The last stream (13,375 feet, 4077 m), reached in 30 minutes, is a little tricky to cross. Climb on, at first gradually, then more steeply, to reach a flat area sometimes called Bal Khola (14,650 feet, 4465 m) in 1¾ hours. Camp here, for there are few other suitable places until the river is reached. The west face of Annapurna looms before you. Local people do not venture much beyond here in their tending of sheep and goats.

Descend and round a ridge crest to the canyon of the Miristi Khola proper. The river is almost a mile below you, yet its roar can be heard. Continue on steep grassy slopes and pass an overhanging rock (14,075 feet, 4290 m) suitable for camping, 45 minutes from the high point. Descend more steeply on grass, cross a stream, and go down into shrubbery until it appears that a 1000-foot (300-m) cliff will block the way to the valley floor. The trail heads west to a break in the rock wall and descends through the break to the river (11,500 feet, 3505 m) 1½ hours from the overhanging rock. The impressive gorge at the bottom gives a feeling of isolation. Head upstream on the northwest (right) bank. The dense shrubs may make travel difficult. There are campsites by some sand near a widening in the river (11,575 feet, 3528 m), where it may be possible to ford in low water. Otherwise, head upstream for 10 minutes to a narrowing where there may be a bridge. Cross the river, if possible, and camp on the other side if it is late.

Once on the southeast (left) bank of the Miristi Khola, follow the trail upstream. The vegetation soon disappears as altitude and erosion increase. The trail becomes indistinct in the moraine. As the valley opens up, bear right to the east and leave the river bottom to climb the moraine to a vague shelf. Continue beyond to a small glacial lake in the terminal moraine of the North Annapurna Glacier. Cross its outflow to the right and climb the lateral moraine to the left. There are views of the Nilgiri to the west. The base camp for the various attempts to climb Annapurna from the north is on a flat shelf of land (14,300 feet, 4359 m) to the north of the glacier. There is a steep drop-off to the glacier valley to the south and east. The base camp is reached in 3–4 hours from the crossing of the Miristi Khola. Annapurna (26,545 feet, 8091 m) was the first 8000-m peak to be climbed, in 1950, by the French from this side.

The view of Annapurna I from the base camp is minimal. Better views can be obtained by contouring and climbing to the east to a grassy knoll from which much of the north face can be seen. You could also proceed toward Camp I by dropping from the shelf and climbing along the lateral moraine of the glacier to 16,000 feet (4877 m). Exploratory and climbing journeys will suggest themselves to those with experience. The Great Barrier, an impressive wall of mountains to the north, separates you from Tilicho Tal. Be sure to take enough food to stay awhile and enjoy this unforgettable area.

The subtropical zone is considered to be (3300–6500 feet/1000–2000 m in the west, to 5500 feet/1700 m in the east). |

Birds of prey either kill other animals or feed on their carcasses. Nepal has over seventy species, including twenty-one owls. The Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus, length 24 inches, 60 cm) is a familiar small vulture around villages. It has a wedge-shaped tail. The adult is white with black flight feathers and yellow head (immature is brownish). It also occurs in tropical and temperate zones. The steppe eagle (Aquila nipalensis, length 29–32 inches, 74 to 81 cm) is a large eagle with long, broad wings and medium-long tail. From below, while in flight, it looks dark brown with one or two white wing bars across the undersides of its wings. It is a common winter visitor between September and April and occurs from tropical to alpine zones. |

Its call monotonously repeated all day in spring and summer, the barbet usually remains hidden in tree tops. The blue-throated barbet (Megalaima asiatica, length 9 inches, 22 cm), green with a blue throat and face and red forehead, makes a loud “chuperup.” It also occurs in tropical and temperate zones. The coppersmith (or crimson-breasted) barbet (Megalaima haemacephala, length 5½ inches, 14 cm), greenish with yellow throat and reddish breast, makes a metallic note said to resemble a coppersmith beating on metal. It also occurs in the tropical zone. The Indian cuckoo, or kaphal pakyo (Cuculus micropterus, length 13 inches, 33 cm), like several other cuckoo species, is grayish above and on the throat, with the rest of the underparts barred black and white. It occurs in tropical and temperate zones. Its bubbling call sounds like “one more bottle.” It calls all night, as does the common hawk cuckoo or brain-fever bird (Hierococcyx varius, length 13 ½ inches, 34 cm), which is gray above and mottled or barred brown below. It occurs in the tropical zone. Calls start slowly and accelerate to a high pitch. |

Nepal has six species of minivets. These are long-tailed, brightly colored arboreal birds. Long-tailed minivet, or Ranichara (Pericrocotus ethologus, length 7 inches, 18 cm) males are red and black, females yellow and black. Flocks often perch on treetops and twitter to each other as they fly from tree to tree. They occur in the temperate zone. |

The Asian magpie robin (Copsychus saularis, length 7½ inches, 19 cm) is a long-tailed, black-and-white robin. The male is black above, on throat and breast, and rest of underparts; the wing bar and outer tail coverts are white. In the female, black is replaced by gray. Common in gardens, it has a sweet song of short, repeated phrases. |

The spiny babbler (Turdoides nipalensis, length 11 ½ inches, 24 cm) is Nepal’s only endemic bird. It is very secretive and rarely seen but fairly common in thick scrub. Grayish brown and streaked, with a long tail, it also occurs in the temperate zone.  |

The term Annapurna Sanctuary, coined by outsiders, denotes the high basin southwest of Annapurna and the headwaters of the Modi Khola. This vast amphitheater, surrounded by Himalayan giants, was explored by Jimmy Roberts in 1956 and brought to the attention of the Western world by the British Expedition to Machhapuchhre in 1957. The presence of the gigantic mountains named for the goddesses Anna-purna and Gangapurna, important figures in Hindu myth and folklore, justify calling it a sanctuary. Its gate, the deep gorge between the peaks Hiunchuli and Machhapuchhre, marks a natural division between the dense rain forest and bamboo jungle of the narrow Modi Khola valley and the scattered summits and immense walls of the mountain fortress inside. This sanctuary area is also referred to as the Annapurna Base Camp and the Machhapuchhre Base Camp.

Trekking possibilities are varied. Those without time to head up the Kali Gandaki river, also known as Thak Khola, can make a circuit from Pokhara into the Annapurna Sanctuary in less than 10 days, with little backtracking. However, to enjoy the route and the sanctuary itself without feeling rushed, plan a few more days. This area can be easily combined with the entire Annapurna circuit or with a trek to Jomosom that offers various link-up possibilities.

The route up the Modi Khola has always had a reputation among porters for being slippery and difficult. While lodges and inns that cater to the trekker now exist outside the inhabited areas, the trail has not changed much. It is often wet, and in the steep and slippery places a fall could be disastrous. But the trail doesn’t quite live up to its old reputation; the route to the North Annapurna Base Camp (covered in the previous section) is a much more serious undertaking.

Extracting lokta or bark from the Daphne bholua shrub for papermaking (Photo by R.C. Sedai)

The centuries-old technique of making paper in Nepal has been revived by outsider interest in handmade paper. In addition to the manufacturing along the Kali Gandaki, you will find it made along tributaries of the Arun and parts in between. The Daphne bholua shrub grows at elevations of 7000 to 11,000 feet (2100 to 3300 m), and the barks used for making paper are called lokta or baruwa locally. The outer barks are stripped off, cleaned, then soaked in water and dried and carried down to the processing area. The alkali leachate of wood ashes is used for digesting the barks by boiling the mixture in copper vessels, cutting them, and continuing the process until they are soft and breakable. The bark material is then pounded into a pulpy mass and mixed into a dense emulsion with water. The casting of the pulp into paper is done by a stream or pond by mixing the concentrate in a tank of water, and swirling just the right amount on a mesh frame. The slurry on the frames is left to dry in the sun, when the paper is removed.  |

You can find cooked food and lodging along the entire route in season (ask at Chomrong before venturing forth at other times). During winter months, snowfall may make the trip difficult or impossible, and avalanche hazard can increase the risk.

This is the homeland of the Gurung people, an ethnic group renowned for bravery in the Gurkha regiments. They speak their own unwritten language, a member of the Sino-Tibetan family, and names of villages don’t transliterate accurately into Nepali. Hence the variations in spelling that you will see on signboards here. Is it Ghandrung or Ghandruk? Landrung or Landruk? Chomro or Chomrong? Kyumunu, Kimrong, Kymnu, Kyumnu, or Kimnu? We try to use the ACAP spellings.

For those traveling from Pokhara, one access route to the sanctuary leaves the road at Lumle to pass through Chandrakot. This is not a popular approach, as more people prefer beginning from Phedi or Naya Pul. If coming from the Kali Gandaki/Thak Khola, you could leave the standard trail at GhoRepani or Chitre.

Accommodations are available in almost all villages en route with opportunities to stay in traditional bhaTTi lower down.

From Pokhara (2713 feet, 827 m) you can either walk, or board a bus or taxi to get to the Baglung bus station (Nala Mukh or Besi Parak different from the Bas Parak, near Mahendra Pul), in the northern section of the city. Buses leave regularly. The first place trekkers leave the road is Phedi to either travel into the sanctuary via Landruk or to travel on the east side of the Modi Khola until reaching Himalpani.

Another place to leave the road is near Lumle, the site of a British agricultural development project where former Gurkha soldiers and others are trained in farming. It has one of the highest rainfalls in Nepal. Walk from Lumle (5300 feet, 1615 m) to Chandrakot (5250 feet, 1600 m) at the west end of the ridge in 30 minutes. The views from Chandrakot are unforgettable. You will cross the Modi Khola, which flows south from between the peaks Annapurna South and Machhapuchhre, which stand before you. The Annapurna Sanctuary lies upriver inside the gate formed by Machhapuchhre and Hiunchuli, the peak east of Annapurna South. The trail descends to the Modi Khola, follows its east (left) bank southward a short distance to a suspension bridge, and crosses to the prosperous town of Birethanti (3600 feet, 1097 m) 1¼ hours from Chandrakot.