Immune Cells in Healthy Tissue: Homeostasis

Hematopoietic stem cells, which are found in the bone marrow of adults, give rise to all cells involved in an immune response throughout the lifetime of an organism (see Chapter 2). Myeloid cells, part of the innate immune system, include antigen-presenting cells (dendritic cells and macrophages) and granulocytes (neutrophils, basophils, and eosinophils). Once mature, these cells exit the bone marrow. Some continuously circulate through the body, while others take up long-term residence in our many tissues and organs. Lymphoid cells, part of the adaptive immune system, also begin their development in the bone marrow, but complete it in distinct niches. B cells mature among the osteoblasts of the bone marrow, and some complete maturation in the spleen. T-cell precursors leave the bone marrow quite early and mature in a distinct organ, the thymus. During maturation, B and T cells rearrange genes that encode the B-cell receptor and T-cell receptor, and each generates a unique BCR or TCR (see Chapter 6). Immature T cells (thymocytes) and B cells undergo negative selection to rid their antigen receptor repertoires of autoreactive cells. Thymocytes also undergo positive selection for T-cell receptor specificities that recognize self-MHC (major histocompatibility complex)–peptide complexes with some affinity. The few immature lymphocytes that survive these selection events exit from the thymus and bone marrow as mature, naïve T lymphocytes and naïve B lymphocytes (see Chapters 8 and 9).

Naïve Lymphocytes Circulate between Secondary and Tertiary Lymphoid Tissues

About 30 minutes after entering the bloodstream, nearly half of all mature, naïve lymphocytes produced by the thymus and bone marrow travel directly to the spleen, where they browse for approximately 5 hours (Overview Figure 14-1). Most of the remaining lymphocytes enter various peripheral lymph nodes, where they spend 12 to 18 hours scanning cellular networks for antigen. A small number of lymphocytes (about 10%) migrate to barrier immune tissues, including the skin and gastrointestinal, pulmonary, and genitourinary mucosa, where they are in close contact with the external environment (see Chapter 13).

How do the millions of newly generated naïve lymphocytes find their antigenic match, if there is one? The odds that the tiny percentage of lymphocytes capable of interacting with an antigen (one in 105) actually makes contact with that particular antigen are improved considerably by a variety of strategies. First, lymphocytes circulate through secondary lymphoid tissues continuously. An individual lymphocyte may make a complete circuit from blood to tissues to lymph and back again once or twice per day, probing earnestly for antigen in secondary lymphoid tissues. Second, as we will see shortly, the organization of lymphocytes within secondary lymphoid tissues profoundly increases the probability that a lymphocyte will make contact with “its” antigen (Overview Figure 14-2).

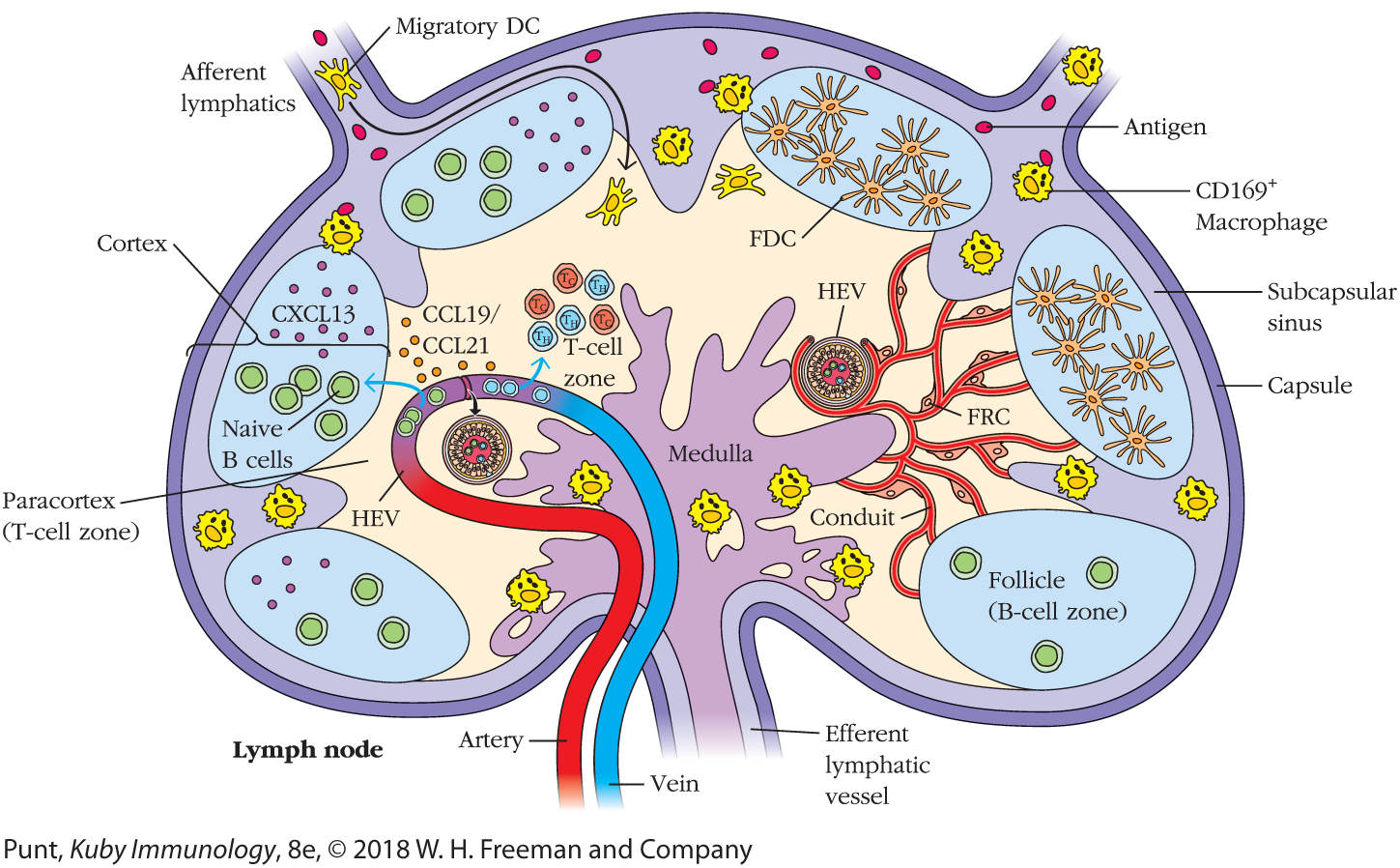

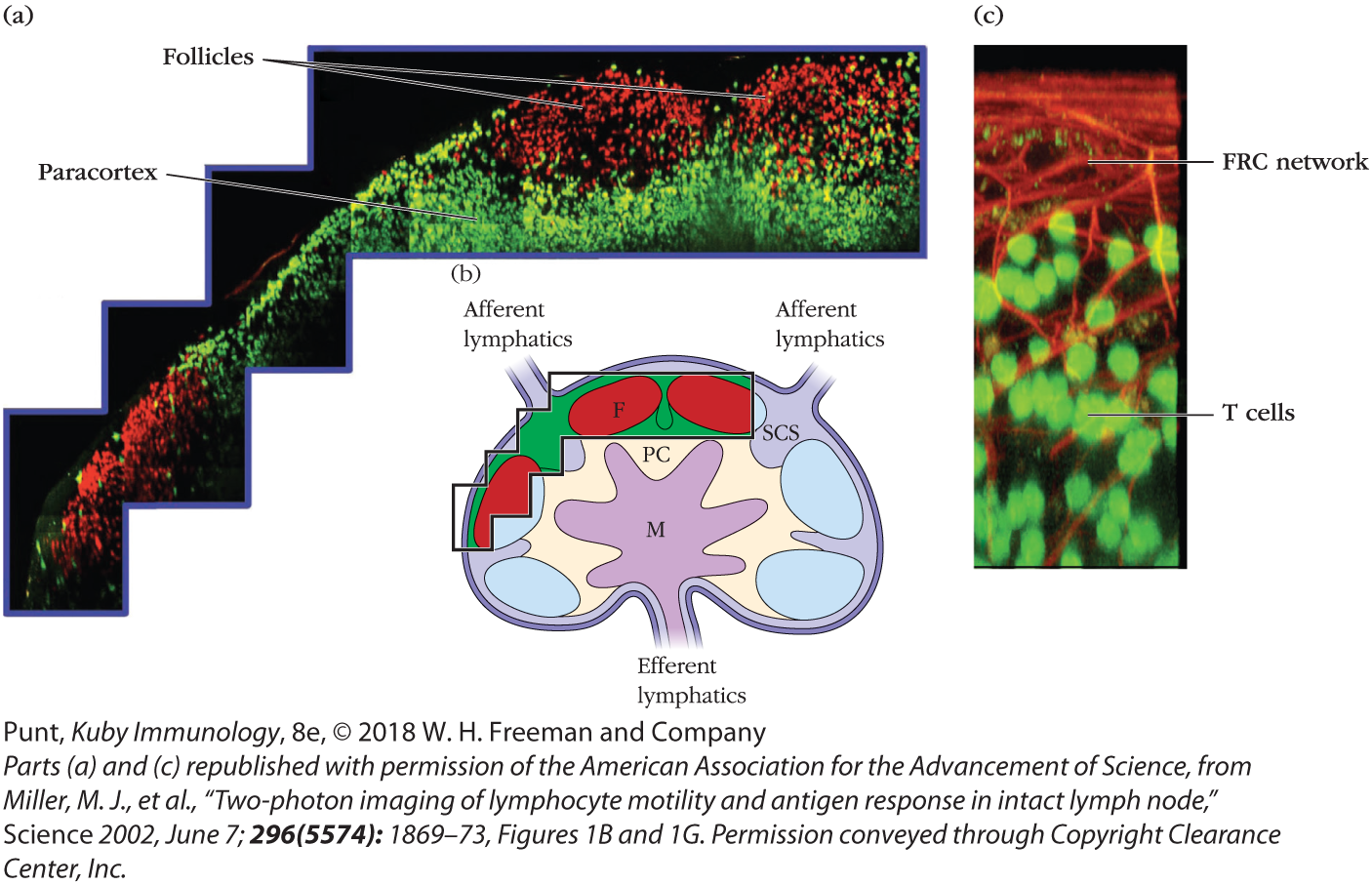

OVERVIEW FIGURE 14-2

Cell Traffic in a Resting Lymph Node

T and B lymphocytes travel into a lymph node from the blood, migrating across high-endothelial venules (HEVs) into the paracortex (extravasation). T lymphocytes browse the surfaces of cells on the fibroblastic reticular cell (FRC) network, and if they do not bind to antigen within 16 to 20 hours, they leave the lymph node via efferent lymphatics in the medulla. B lymphocytes travel into the follicles and browse the surfaces of follicular dendritic cells. If they do not bind antigen, they, too, leave the node via the efferent lymphatics. Dendritic cells and other antigen-presenting cells migrate into the lymph node via afferent lymphatics and join resident dendritic cells in the T-cell zone on the FRC network, where they are scanned by lymphocytes. Antigen typically arrives at the lymph node via the afferent lymphatics, entering the subcapsular sinuses either as processed peptide presented by antigen-presenting cells or as unprocessed protein that can be coated with complement. T and B cells are directed to their respective zones by chemokine receptor–chemokine interactions that are discussed in the text.

A double walled capsule is shown. The region on the inner side of the capsule is labeled as the subcapsular sinus. Small rounded freely floating cells labeled as the antigens and C D 169 macrophages are shown in the subcapsular sinus. Two conduits, labeled as the afferent lymphatics originate from the upper part of the brain. A cell passing into the paracortex of the brain through the afferent lymphatics is labeled as migratory D C. Six oval shaped follicles, aligned along the subcapsular sinus constitute the cortex. The follicles have naïve B cells, CXC L 13, and FDC. The region interior to the cortex forms the paracortex, which is also called as the T-cell zone. Small rounded cells in the paracortex are labeled as CCL 19 and CCL 21. A T-cell zone, with six t-cells is present in the paracortex, right above the medulla. Two high-endothelial venules are present in the paracortex. A vein and an artery pass through the medulla and the paracortex region. A network of conduits, with an HEV is shown to the right of the medulla. One branch of conduit is labeled as FRC. The conduits connect the medulla to the cortex, and the B-cell zone within the follicle on the right, through the paracortex region. The conduit stem at the posterior region of the lymph node is labeled as the efferent lymphatic vessel. The innermost posterior region of the lymph node is labeled as the medulla. Two follicles (B-cell zone) are present, one on either side of the medulla.

Naïve lymphocytes destined for lymph nodes exit the blood at the high-endothelial venules (HEVs) in the cortex of the lymph nodes (Figure 14-3a). These specialized postcapillary venules are lined with distinct endothelial cells that have a plump, cuboidal (“high”) shape (see Figure 14-3b). This contrasts sharply in appearance with the flattened endothelial cells that line the rest of the blood vessel. As many as 3 × 104 lymphocytes move through a single lymph node’s HEVs every second.

FIGURE 14-3 Lymphocyte migration through HEVs. (a) An HEV in a lymph node as visualized by two-photon microscopy. Blood vessels are stained red and the HEV appears orange. (b) Schematic cross-sectional diagram of a lymph-node high endothelial venule (HEV). Lymphocytes (blue) are shown in various stages of attachment to the HEV and in migration through the endothelial cells (tan) into the cortex of the lymph node in the direction of the arrow. (c) Micrograph of frozen sections of lymphoid tissue. Some 85% of the lymphocytes (darkly stained) are bound to HEVs (in cross-section), and constitute only 1% to 2% of the total area of the tissue section.

The micrograph in section a shows a network of conduits with a high endothelial venule and capillaries. A larger conduit is labeled as arteriole. The micrograph is section b shows a cluster of tiny rounded cells. The sectional view shows a double walled structure, with rounded cells aligned between the double walls. These cells also migrate onto the inner core. An outward pointing arrow is shown along the path of the migrating lymphocytes that are present amidst the endothelial cells. A text corresponding to these cells reads, lymphocytes passing across the wall. A membrane along the inner wall of the capsule is labeled as basement membrane. The inner core of the lymph node has the endothelial cells.

Interestingly, HEVs fail to develop in animals raised in a germ-free environment. Investigators tested the possibility that HEV formation was dependent on antigen by surgically blocking the afferent lymphatic vessels, where antigen typically enters. Within a surprisingly short period, HEVs stopped functioning as access points for lymphocytes and in days the endothelial cells reverted to a more flattened morphology. These results show that endothelial cells receive and respond to signals from the lymph node.

How do naïve cells know that HEVs are the right site for entry into lymph nodes? The answer illustrates a common theme in immune cell migration: where cells go is determined by the array of surface protein receptors they express and the set of ligands expressed by cells they browse. Several different sets of interactions regulate lymphocyte homing to specific tissues before, during, and after an immune response. These include chemokines and their corresponding chemokine receptors, selectins, integrins, and adhesion molecules. We will consider some of these below and describe them more thoroughly in Advances Box 14-1.

ADVANCES BOX 14-1

Molecular Regulation of Cell Migration between and within Tissues

The molecules that control movement of the cellular players within and between immune tissues include a number of important receptor/ligand families: selectins and integrins (collectively referred to as cell-adhesion molecules [CAMs]), and chemokines and chemokine receptors. These molecules regulate extravasation, the transit of cells from blood to tissue, as well as trafficking within tissues.

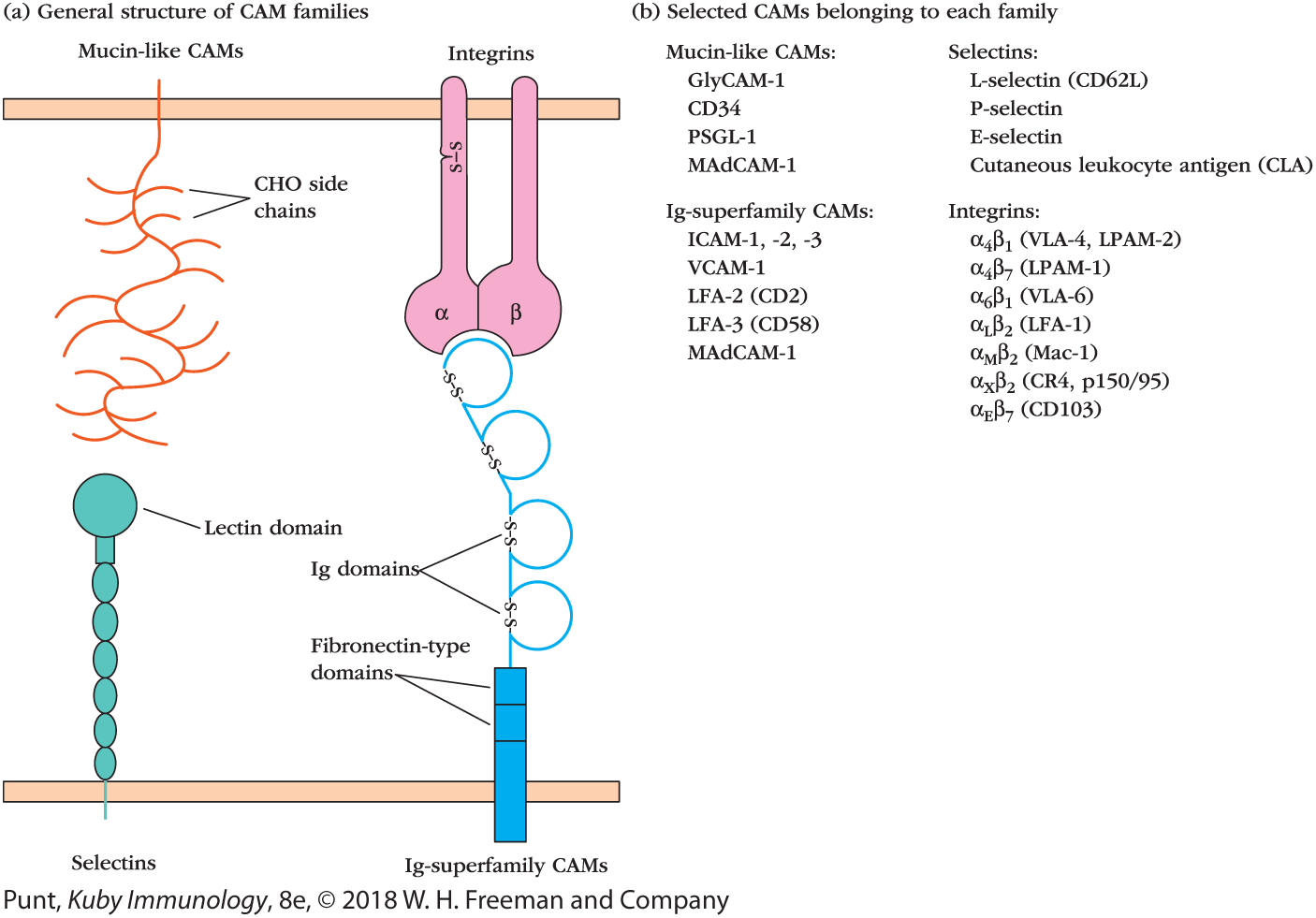

Cell-Adhesion Molecules: Selectins, Mucins, Integrins, and Immunoglobulin Superfamily Proteins

Cell-adhesion molecules (CAMs) are versatile molecules that play a role in all cell-cell interactions. In the immune system, CAMs play a role in helping leukocytes adhere to the vascular endothelium prior to extravasation. They help secure the location of resident memory cells among innate cells in barrier tissues. They also increase the strength of the functional interactions between cells of the immune system, including TH cells and APCs, TH cells and B cells, and CTLs and their target cells.

Most CAMs belong to one of four protein families: the selectin family, the mucin-like family, the integrin family, and the immunoglobulin (Ig) superfamily (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 The four families of cell-adhesion molecules. (a) Schematic diagrams depict the general structures of members of the four families of cell-adhesion molecules. The lectin domain in selectins interacts primarily with carbohydrate (CHO) moieties on mucin-like molecules (collectively referred to as PNAd and PSGL-1). In integrin molecules, the α and β subunits combine to form the binding site, which interacts with an Ig domain in CAMs belonging to the Ig superfamily. These CAMs also include protein domains similar to those found in fibronectin. MAdCAM-1 (not shown), which is on the surface of endothelial cells that allow entry into the gut mucosa, contains both mucin-like and Ig-like domains and can therefore bind to both selectins and integrins. (b) A list of representative CAMs from each family.

The four structures are labeled as Selectins, Ig-superfamily CAMs, Integrins, and Mucin-like CAMs. The selectins and the Ig-superfamily CAMs are anchored to the bottom double wall. The selectins is made of a chain of oval-shaped structures with a rounded head on top labeled as the lectin domain. The Ig-superfamily CAMs have a vertical rectangular structure labeled as the fibronectin-type domains and a looped chain attached to it. A di-sulfide bond closes the mouth of each loop. The Mucin-like CAMs are attached to the upper double wall, right above the selectins, it has a branched chain structure labeled as C H O side chains. The Integrins are made of an alpha and a beta unit, which are fused at the bottom to form the binding site. The alpha chain has a di-sulfide bond. A table in section b shows the selectins corresponding to different mucin-like CAMs and the integrins corresponding to different Ig-superfamily CAMs. The data under Mucin-like CAMs is as follows: GlyCAM-1: L-selectin; CD34: P-selectin; PSGL-1: E-selectin; and MAdCAM-1: Cutaneous leukocyte antigen (CLA). The data under Ig-superfamily CAMs is as follows: ICAM-1, 2, 3: alpha subscript 4 beta subscript 1 (V L A-4, L P A M-2); VCAM-1: alpha subscript 4 beta subscript 7 (LPAM-1); LFA-2 (CD2): alpha subscript 6 beta subscript 1 (VLA-6); LFA-3 (CD 58): alpha subscript ¬L beta subscript 2 (LFA-1); MAdCAM-1: alpha subscript M beta subscript 2 (Mac-1); alpha subscript x beta subscript 2 (C R 4,p150 over 95); alpha subscript E beta subscript 7 (CD103).

Selectins and Mucin-Like Proteins

The selectin family of membrane glycoproteins has an extracellular lectin-like domain that enables these molecules to bind to specific carbohydrate groups that decorate glycosylated mucin-like proteins. The selectin family includes L-, E-, and P-selectin. L-selectin, also called CD62L, is expressed by naïve lymphocytes and helps initiate extravasation at the HEVs of lymph nodes. Cutaneous leukocyte antigen (CLA) is another selectin expressed by memory T cells. It binds E-selectin and regulates homing to the skin.

Mucin-like proteins are a group of heavily glycosylated serine- and threonine-rich proteins that bind to selectins. Those relevant to the immune system include CD34 and GlyCAM-1, found on HEVs in peripheral lymph nodes, and MAdCAM-1, found on endothelial cells in the intestine.

Selectins can bind to themselves as well as to sulfated carbohydrate moieties, including the sialyl-Lewisx carbohydrate “cap” that decorate selectins. The L-selectin that is expressed on naïve lymphocytes (CD62L) specifically interacts with carbohydrate residues referred to generally as peripheral node addressin (PNAd), which is found associated with multiple molecules (e.g., CD34, GlyCAM-1, and MAdCAM-1) on endothelial cells.

Integrins

Integrins are heterodimeric proteins consisting of noncovalently associated α and β chains. Integrins bind extracellular matrix molecules as well as cell-surface adhesion molecules. Leukocytes express several important integrins. The β2 integrins (or CD18 integrins) combine with CD11 α chains to bind to members of the Ig superfamily cellular-adhesion molecules (ICAMs). Lymphocyte function–associated antigen-1 (LFA-1 or CD11a/CD18) is one of the best-characterized integrins and regulates many immune cell interactions, including naïve T-cell/APC encounters. It initially binds weakly to ICAM-1, but a signal from the T-cell receptor will alter its conformation and result in stronger binding (see Figure 1). Such inside-out signaling is an important feature of multiple integrins and allows cells to probe other cell surfaces before making a full commitment to an interaction. The β7 integrins (e.g., CD103 [αEβ7] and α4β7) are a particularly important subset of integrins that allows leukocytes to mingle with epithelial cells in our barrier tissues. CD103 interacts with E-cadherin (CD324) on epithelial cells and is expressed by gut and skin TREG cells, TRM cells, and APCs.

Immunoglobulin Superfamily CAMs

The Ig superfamily CAMs (ICAMs) are a diverse group of proteins, which act as ligands for β2 integrins. ICAMs interact with LFA-1 (see above), but also exhibit homotypic binding—meaning they interact with themselves. MAdCAM-1 is expressed on the endothelium of blood vessels in the gut and other mucosa and has both Ig-like domains and mucin-like domains. It helps direct cell entry into the mucosa, binding to integrins and selectins expressed by lymphocytes induced to home to the gut, respiratory, and urogenital tracts.

Chemokines and Chemokine Receptors

Chemokines are small polypeptides that play a major role in regulating immune cell trafficking. Most consist of 90 to 130 amino acid residues (see Appendix III for the complete list of chemokines and a table showing the differences in chemokine receptor expression that govern leukocyte migration). Not only do they act as chemoattractants, but they also play a role in adhesion and activation of leukocytes. “Housekeeping” chemokines are constitutively produced in lymphoid organs and tissues or in nonlymphoid sites such as the skin, where they direct normal trafficking of lymphocytes between primary and secondary lymphoid organs (e.g., from bone marrow to spleen, and from thymus to lymph node). These include CCL19 and CCL21, which decorate the FRC network and direct lymphocytes to T-cell zones, and CXCL13, which decorates the FDC network and directs cells to B-cell zones.

In contrast, inflammatory chemokines are typically induced in response to infection and proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α. IL-8, also known as CXCL8, is one of the best examples of inflammatory chemokines and is made by multiple cells in response to antigen invasion. It attracts neutrophils, which express the receptors for IL-8: CXCR1, and CXCR2.

Extravasation is an excellent example of how adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors organize the migration of leukocytes. We discussed the extravasation of naïve lymphocytes across high-endothelial venules in the text of this chapter. Table 1 highlights the molecules and events involved in extravasation of these and other leukocytes, neutrophils, and monocytes, which typically cross blood vessels to join the immune response against pathogens.

| Leukocyte | Molecules involved in rolling | Chemokines involved in activation | Molecules involved in adhesion | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophils | L-selectin and PSGL-1 | IL-8 and macrophage inflammatory protein 1β (MIP-1β [also called CCL4]) | LFA-1 and MAC-1 | First to the site of inflammation: responds to C5a, bacterial peptides containing N-formyl peptides, and leukotrienes within inflamed tissues |

| (Inflammatory) monocytes | L-selectin | Monocyte-chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1 [also called CCL2]) | VLA-4 | Home to tissues after neutrophils; respond to bacterial peptide fragments and complement fragments within inflamed tissues |

| Naïve lymphocytes | L-selectin, LFA-1, VLA-4 (in low-affinity forms) | CCL21, CCL19, CXCL12 (T cells), and CXCL13 (B cells) | LFA-1 and VLA-4 | Travel across high-endothelial venules to enter the lymph node |

HEVs express a specific combination of ligands, collectively known as an addressin, that is recognized by CD62L, a selectin that is expressed on the surface of newly generated naïve T and B cells (see Advances Box 14-1, Figure 1). Endothelial cells associated with other tissues, such as the intestinal mucosa, skin, or brain, express distinct addressins that allow entry of different subsets of white blood cells, including activated lymphocytes.

When naïve lymphocytes engage HEV addressins, they slow down and begin to roll along the blood vessel wall. This initiates a sequence of events that ultimately induce cells to leave the blood vessel by squeezing between endothelial cells, a process called extravasation.

Key Concept:

- Naïve B and T lymphocytes leave the blood and enter the lymph nodes at high-endothelial venules (HEVs) via a process called extravasation.

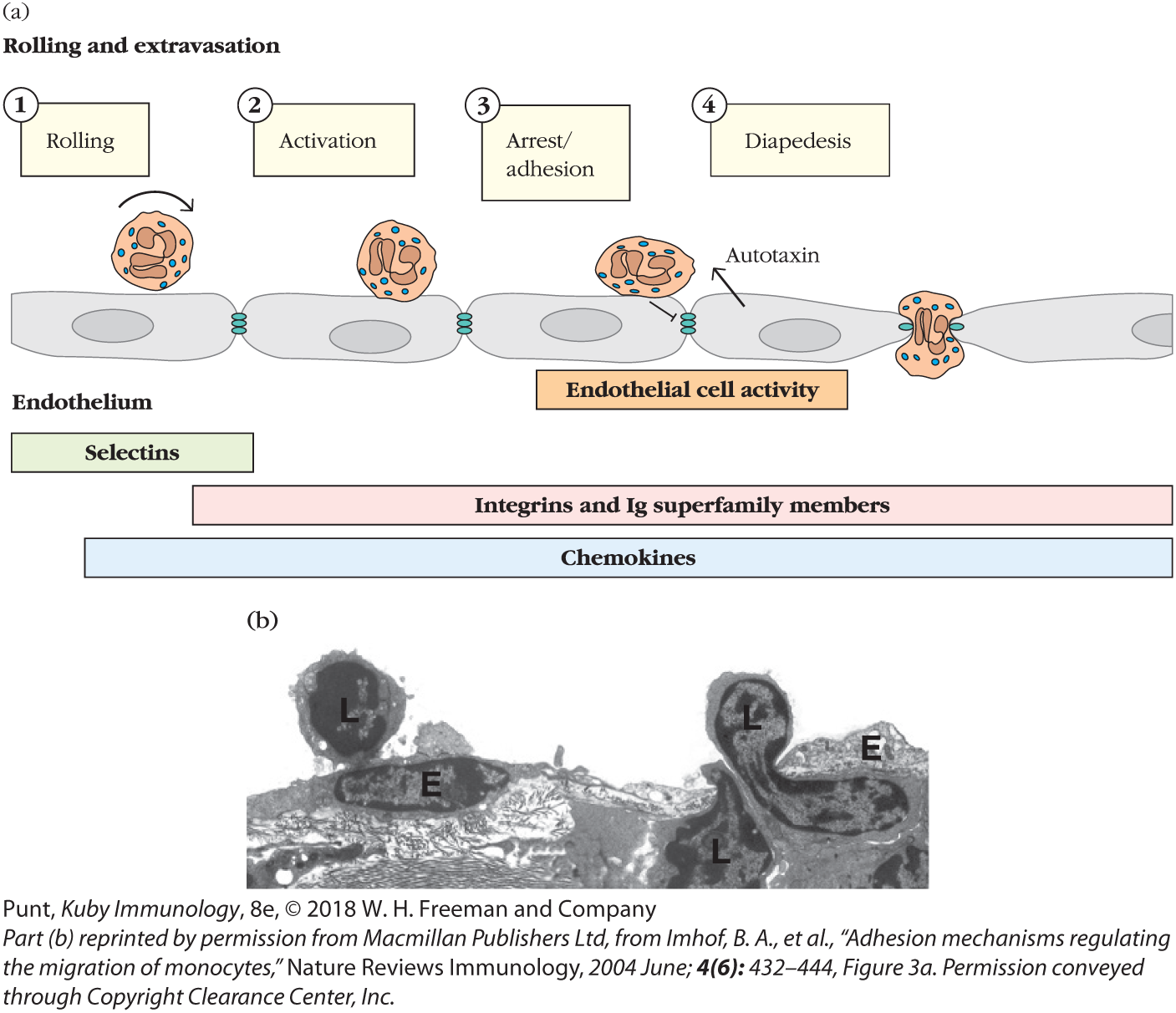

Extravasation Is Driven by Sequential Activation of Surface Molecules

Extravasation is divided into four steps, each of which is regulated by distinct families of molecules: (1) rolling, mediated by selectins; (2) activation by chemokines; (3) arrest and adhesion, mediated by integrin interaction with Ig family members; and, finally, (4) diapedesis, transendothelial migration (Figure 14-4).

FIGURE 14-4 The steps of leukocyte extravasation. (a) Schematic of the major events regulating extravasation. A neutrophil is depicted, but the events depicted are applicable to all leukocytes. Tethering and rolling are mediated by binding of selectin molecules to sialylated carbohydrate moieties on mucin-like CAMs. Chemokines then bind to G protein–linked receptors on the leukocyte, triggering an activating signal. This signal, combined with the shear force produced by blood flow, induces a conformational change in the integrin molecules, enabling them to adhere firmly to Ig superfamily molecules on the endothelium. The arrest of a leukocyte also generates signals within endothelial cells that generate factors (autotaxin) that enhance leukocyte motility, loosen adhesive connections between cells, and induce extension of processes that help draw the leukocyte across. Ultimately, leukocytes crawl between endothelial cells into the underlying tissue (transmigration). (b) Transmission electron micrograph capturing lymphocytes (L) migrating through the endothelial cell (E) layer.

Section a, shows a layer of endothelial cells that have adhesive connections between them. Selectins, integrins and I superscript g superfamily members, and chemokines are present below the endothelium layer. The steps in the extravasation process are listed as follows:

Step 1: Rolling. A neutrophil rolls over the endothelial cell surface.

Step 2: Activation. The neutrophil stops near the right end of the cell.

Step 3: Arrest or adhesion. The neutrophil moves closer to the adhesive connection between the cells. An upward arrow on the cell indicates autotaxin generation.

Step 4: Diapedesis. The neutrophil is anchored between the endothelial cells.

The first part of the micrograph shows a rounded cell representing a lymphocyte on the cell surface, moving toward the endothelial cells. The second part of the micrograph shows the lymphocyte partially migrated into the endothelial cells.

As naïve T and B cells approach the HEV in a lymph node, their surface CD62L latches on specifically to the adhesion molecule GlyCAM, which is expressed by endothelial cells. Because this interaction is relatively weak, the cell doesn’t adhere tightly to the blood vessel wall, but rather tumbles and rolls as the blood flows by. This slows the cell down long enough to allow new interactions to form. Chemokines decorating the surface of the endothelial cells interact with the chemokine receptor CCR7, which is expressed by T and B cells. Chemokine receptor signals induce a change in conformation of the lymphocytes’ integrins (e.g., LFA-1) that enhance their ability to bind tightly to ICAMs on the endothelial cell. Even the shear forces generated by blood flow contribute to enhanced binding and lymphocyte arrest. The naïve lymphocyte is now prepared to crawl between endothelial cells, driven in addition by attraction to higher concentrations of chemokines inside the lymph node.

Lymphocyte motility is enhanced by the activity of an enzyme, autotaxin, released by HEV cells themselves. In fact, endothelial cells are very active participants. They recognize the binding of an arrested lymphocyte and send signals that loosen adhesions with neighboring endothelial cells. They also reorganize their cytoskeleton and extend processes that help draw the lymphocyte between. All in all, it takes about 2 to 3 minutes for lymphocytes to pass between endothelial cells.

Naïve T and B cells are not the only cells that extravasate, of course. Any circulating leukocyte that recognize addressins expressed by particular endothelial cells exit the blood and enter the neighboring tissues. Only cells that express the right set of receptors for the addressins are allowed to cross. Effector cells, for instance, recognize addressins induced by inflammatory responses at the site of infection. However, they will pass by healthy tissues, ignoring endothelial cells that do not express appropriate addressins.

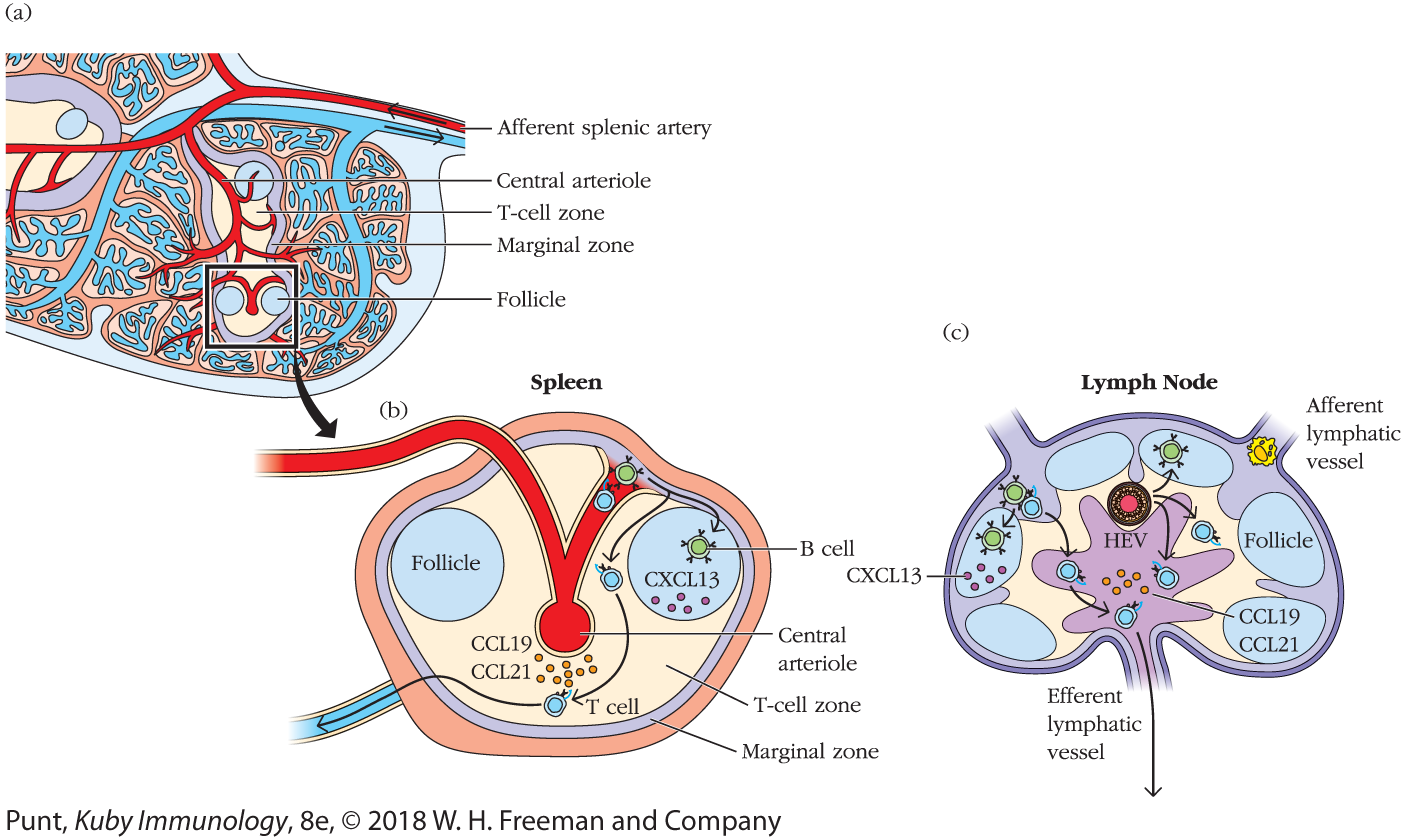

Interestingly, the spleen appears to have no HEVs. Arterioles release immune cells directly into the marginal sinus. (See Figure 14-5 for a comparison of approaches taken by spleen and lymph node.) Furthermore, the cues lymphocytes use to home to the white pulp of the spleen differ from those they use to enter the cortex of the lymph node and are not yet fully understood. Entry appears to require the coordinated activity of chemokines, integrins, and autotaxin, but is independent of selectins such as CD62L, which are important for lymph-node entry.

FIGURE 14-5 Lymphocyte migration in the spleen. (a) Schematic of spleen microanatomy showing the central arteriole, which releases circulating lymphocytes into the marginal zone, a microenvironment that separates blood from the white pulp. (b) T cells then migrate into the T-cell zone (PALS) and B cells migrate into follicles. Cells that do not meet their antigen usually exit via the splenic vein. In the lymph node (c), these migrations are regulated by chemokine receptor–chemokine interactions and guided by FRC and FDC networks, which are described in more detail in the text.

A micro anatomical sectional view of spleen in section a, shows a conduit labeled as the afferent splenic artery, which branches to form the central arteriole within. The region around the central arteriole is labeled as the T-cell zone and the region surrounding the T-cell zone is labeled as the marginal zone. Two rounded structures present in posterior side of the T-cell zone is labeled as the follicle. A part of the spleen is zoomed out and shown in the second part of the illustration.

The zoomed out image in section b shows the central arteriole at the center of a double walled capsule. Two follicles are present, one each on either side of the arteriole. The region between the follicles and the central arteriole is labeled as the T-cell zone and the inner wall of the capsule is labeled as the marginal zone. Small rounded structures in the T cell zone are labeled as CCL 19 and CCL 21. The follicle on the right side has a b-cell and small rounded structures representing CXCL 13. A T-cell and a B-cell are shown to migrate toward the T-cell zone and the B-cell zone. The T-cells in the T-cell zone exit the spleen through a conduit at the bottom left side.

The cutaway view of a lymph node in section c shows the afferent lymphatic vessel at the top right corner and an efferent lymphatic vessel at the bottom. The follicles are in the cortex region and the medulla is at the center. The follicles have small rounded structures within, representing CXCL 13 and B-cells. The T-cells are shown to migrate from the cortex toward the efferent lymphatic vessel through the medulla. Small rounded structures within the medulla are labeled as CCL 19 and CCL 21. An HEV links the cortex to the medulla. The T-cells from the cortex enter the paracortex region through the HEV and the B-cells are migrated toward the follicles through HEV. A small rounded cell is shown to pass through the afferent lymphatic vessel on top.

Key Concepts:

- Extravasation involves four steps: rolling, activation, arrest/adhesion, and, finally, migration between endothelial cells lining the blood vessel. It is the result of an organized sequence of interactions between molecules expressed by leukocytes and their ligands on endothelial cells, including selectins and addressins, chemokine receptors and chemokines, and integrins.

- Addressins are collections of diverse adhesion molecules that vary depending on the tissue a blood vessel serves. They specify which cells can enter that tissue.

- Lymphocytes gain entry into the splenic white pulp via distinct homing mechanisms. The spleen has no HEVs, and selectins do not appear to play a role.

Naïve Lymphocytes Browse for Antigen along the Reticular Network of Secondary Lymphoid Organs

After squeezing between HEV cells, naïve B and T lymphocytes enter the cortex of the lymph node (see Chapter 2), where they are guided by different chemokine interactions to distinct microenvironments. The movements of naïve lymphocytes that enter and scan the lymph node are remarkable to watch. When these were first visualized, the idea that lymphocytes were rather dull and inert (an impression based on cells fixed on microscope slides) was immediately reversed (see Figure 14-6; see also  Video 14-6v for an example; direct links to original sources for all videos can be found at the end of this chapter, on p. 545). These initial videos also inspired the discovery of the fibroblastic reticular cell network. Investigators recognized that fluorescently tagged lymphocytes did not move freely but were influenced by “invisible” structures. These were ultimately identified as the fibroblastic reticular cell (FRC) network of conduits and cells that provide roadways for naïve lymphocytes and antigen-presenting cells (see Figure 2-14).

Video 14-6v for an example; direct links to original sources for all videos can be found at the end of this chapter, on p. 545). These initial videos also inspired the discovery of the fibroblastic reticular cell network. Investigators recognized that fluorescently tagged lymphocytes did not move freely but were influenced by “invisible” structures. These were ultimately identified as the fibroblastic reticular cell (FRC) network of conduits and cells that provide roadways for naïve lymphocytes and antigen-presenting cells (see Figure 2-14).

FIGURE 14-6 Two-photon imaging of live T and B lymphocytes within a mouse lymph node. Fluorescently labeled T lymphocytes (green) and B lymphocytes (red) were injected into a mouse and visualized by two-photon microscopy after they homed to the inguinal lymph node. (a and b) T and B cells localize to distinct regions of the lymph node: T cells in the paracortex (PC) and B cells in the follicles (F). Antigen and APCs enter the subcapsular sinus (SCS). Cells leave via efferent lymphatics from the medulla (M). (c) A magnified image of T cells (fluorescing green) interacting with the fibroblastic reticular cell (FRC) network (stained red).

The imagery in section a shows a spectrum of two different colored patches representing the paracortex and the follicles. A corresponding cutaway view of the lymph node in section b shows two conduits on top representing the afferent lymphatics. The follicles line the cortex region and the medulla is shown at the center. The region between the cortex and the medulla is labeled as the paracortex. The region between the paracortex and the afferent lymphatics is labeled as subcapsular sinus. The imagery corresponds to the three follicles closer to the left afferent lymphatics, which are highlighted in a color and the surrounding cortex highlighted in another color.

The imagery in section c shows a network of conduits on top labeled as the FRC network and small rounded structures underneath represents the T-cells.

Naïve B and T cells spend many hours probing for antigen: B cells in B-cell follicles and T cells in T-cell zones (also called the paracortex) (see Figure 14-5). Naïve T lymphocytes, which express the chemokine receptor CCR7, dive in and out of the lymph-node parenchyma, using FRC tracts (see chapter opening image–associated  Video 14-Ov). They are specifically attracted to this network because it is decorated with the CCR7 ligands CCL21 and CCL19. Naïve B cells that transit across HEVs into the lymph-node cortex also begin their travels along FRC fibers. However, because they express different chemokine receptors, including CXCR5, they soon change allegiance to the fibers established by the follicular DCs, which are decorated with the corresponding chemokine CXCL13.

Video 14-Ov). They are specifically attracted to this network because it is decorated with the CCR7 ligands CCL21 and CCL19. Naïve B cells that transit across HEVs into the lymph-node cortex also begin their travels along FRC fibers. However, because they express different chemokine receptors, including CXCR5, they soon change allegiance to the fibers established by the follicular DCs, which are decorated with the corresponding chemokine CXCL13.

The movements of naïve T and B cells in the spleen are guided by the same chemotactic cues and conduit network (see Figure 14-5). Once they find their way into the white pulp, naïve B cells are attracted to CXCL13 in the follicle and T cells are attracted to CCL19 and CCL21 in the periarteriolar lymphoid sheath (PALS).

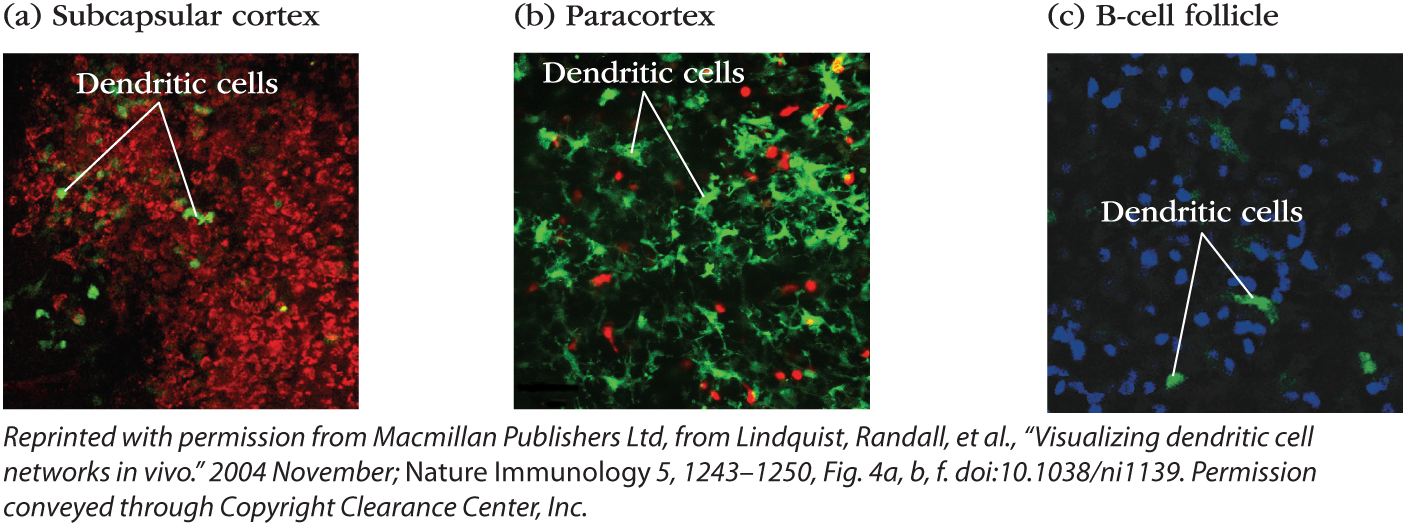

Antigen-presenting cells are found in every secondary lymphoid tissue and every microenvironment (Figure 14-7). Some are long-term residents and others actively migrate within and between tissues. Figure 14-7 shows dendritic cells in several different areas of a lymph node.  Video 14-7v shows the activity of DCs (green) traveling among a bed of more sessile, long-term resident macrophages (red) in the subcapsular sinus of a lymph node. A population of migratory DCs also enters the deeper T-cell zone of the lymph node, where they crawl less vigorously and become part of the FRC network (see Figure 14-7b). They extend their long processes along the conduits to allow naïve T cells to scan their surfaces during their travels. A few DCs are even found in B-cell follicles (see Figure 14-7c), where they also present antigen.

Video 14-7v shows the activity of DCs (green) traveling among a bed of more sessile, long-term resident macrophages (red) in the subcapsular sinus of a lymph node. A population of migratory DCs also enters the deeper T-cell zone of the lymph node, where they crawl less vigorously and become part of the FRC network (see Figure 14-7b). They extend their long processes along the conduits to allow naïve T cells to scan their surfaces during their travels. A few DCs are even found in B-cell follicles (see Figure 14-7c), where they also present antigen.

FIGURE 14-7 Antigen-presenting cells are present in all lymph-node microenvironments. Intravital microscopy of inguinal lymph nodes of anesthetized mice, all of whose dendritic cells fluoresce green. Several areas of the lymph node are visualized (a-c). In the subcapsular sinus (a), green dendritic cells are surrounded by macrophages, which have taken up a red fluorescent dye. In the T-cell zone or paracortex (b), dendritic cells mingle with T cells (red). In the follicle (c), dendritic cells are not as numerous but can be found among the B cells (blue).

Early estimates using static imaging techniques suggested that up to 500 T cells probe the surface of a single dendritic cell (DC) per hour. However, more accurate dynamic imaging data reveal that one DC can be surveyed by more than 5,000 T cells per hour! Suddenly it is much easier to imagine that one in 100,000 antigen-specific T cells can find the MHC-peptide complex to which it can bind.

Naïve B cells spend a similar amount of time scanning for antigen. They travel on distinct cellular pathways, specifically the follicular DC networks in the follicles (Figure 14-8). They probe for antigen on the surface of the follicular DCs themselves, and can also bind soluble antigen that has entered follicles from draining afferent lymphatic vessels.

FIGURE 14-8 Lymphocytes exit the lymph node through portals in the cortical and medullary sinuses. (a) Schematic of lymphocyte traffic in and egress from a lymph node. T cells and B cells follow chemokine cues as they probe the FRC and FDC networks, respectively. If naïve lymphocytes do not find antigen within a certain time period they up-regulate S1PR1 and enter efferent lymphatic vessels from the cortex (B cells) or the medulla (T cells). (b) The movements of fluorescently labeled T cells (green) were visualized by two-photon microscopy in a lymph node where the medullary sinus stains red. The movements of several T cells are traced with colored lines and indicate that they leave at discrete sites called portals. See Video 14-8v.

Section a shows a cutaway view of a lymph node, accompanied by a zoomed out microscopic sectional view. The zoomed out view shows the network of conduits in the paracortex region. A b-cell follicle shown on the right side has naïve b-cells, CXXCL 13, and FDC. A few freely floating macrophages are in the subcapsular sinus surrounding the b-cell follicle. A naïve T-cell enters the left side of the conduit through the H E V and migrates into the medulla. The medulla has small rounded structures labeled as the SIP within. They are scattered all over the subcapsular sinus region as well. A naïve b-cell enters the conduit as CXCR 5 plus, CCR medium, and S1 PR1 low, through another HEV, at the bottom center of the conduit network, and migrates toward the b-cell follicle. It exits the b-cell follicle as S1 PR1 high and joins the lymph flow once again as S1 PR low. A layer of cortical sinuses is shown at the bottom of the conduits network. Small rounded structures between the conduit networks represent CCL 19 and CCL 21. The FR Cs are shown adjoining the conduits.

The micrograph in section b shows a network of red-colored medullary sinus and fluorescent T cells. A line pointing to the center reads, portal area.

If they do not find and bind antigen on their travels, naïve B and T cells up-regulate the sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor, S1PR1, which allows them to leave (egress) secondary lymphoid tissues (see Figure 14-8a). Naïve lymphocytes circulating through lymph nodes leave via efferent lymphatics in both the cortical and medullary sinuses (see Overview Figure 14-2). Cells lining these sinuses express S1P, the ligand for S1PR1. S1PR1-S1P interactions induce naïve lymphocyte migration via specific portals (see Figure 14-8b and  Video 14-8v). Once they have left the node, they return to the blood via the thoracic duct and resume their search for antigen in other lymph nodes. Interestingly, S1PR1 mediates lymphocyte egress from a wide range of other tissues, including the bone marrow and thymus.

Video 14-8v). Once they have left the node, they return to the blood via the thoracic duct and resume their search for antigen in other lymph nodes. Interestingly, S1PR1 mediates lymphocyte egress from a wide range of other tissues, including the bone marrow and thymus.

Although the details of egress from the spleen are still being worked out, the red pulp is rich in S1P and clearly plays a role in regulating the exit of naïve B and T cells. However, most lymphocytes circulating through the spleen appear to exit into the bloodstream directly from the white pulp or marginal zone.

Key Concepts:

- Naïve T and B lymphocytes both enter the cortex of the lymph nodes and are then attracted by chemokines to distinct microenvironments.

- T cells browse the surfaces of antigen-presenting cells in the paracortex of the lymph node, traveling along the FRC network. B cells browse for antigen along follicular DC networks in the follicle.

- Naïve lymphocytes that do not encounter antigen leave the lymph node via efferent lymphatics after about 12 to 18 hours and re-enter the circulation to probe another lymph node. Naïve lymphocytes scan for antigen in the spleen for about 5 hours and exit directly into the bloodstream.

- S1PR1, the receptor for the S1P ligand, regulates lymphocyte exit from many different tissues including the lymph nodes, spleen, thymus, and bone marrow.