From Place Bastille to the Pompidou Center

Rue des Rosiers: Jewish Quarter

Rue des Rosiers: Jewish Quarter

Rue Ste. Croix de la Bretonnerie

Rue Ste. Croix de la Bretonnerie

This walk takes you through one of Paris’ most intriguing quarters, the Marais, and finishes in the artsy Beaubourg district. Naturally, when in Paris you want to see the big sights—but to experience the city, you also need to visit a vital neighborhood. The Marais fits the bill, with hip boutiques, busy cafés, trendy art galleries, narrow streets, leafy squares, Jewish bakeries, aristocratic châteaux, nightlife, and real Parisians. It’s the perfect setting to appreciate the flair of this great city.

The walk has a little history (the Bastille, Place des Vosges), but the main focus here is on the shops and daily life. Follow this suggested route for a start, then explore. If at any point you want to wander into a store or savor a café crème, by all means, you have permission to press pause.

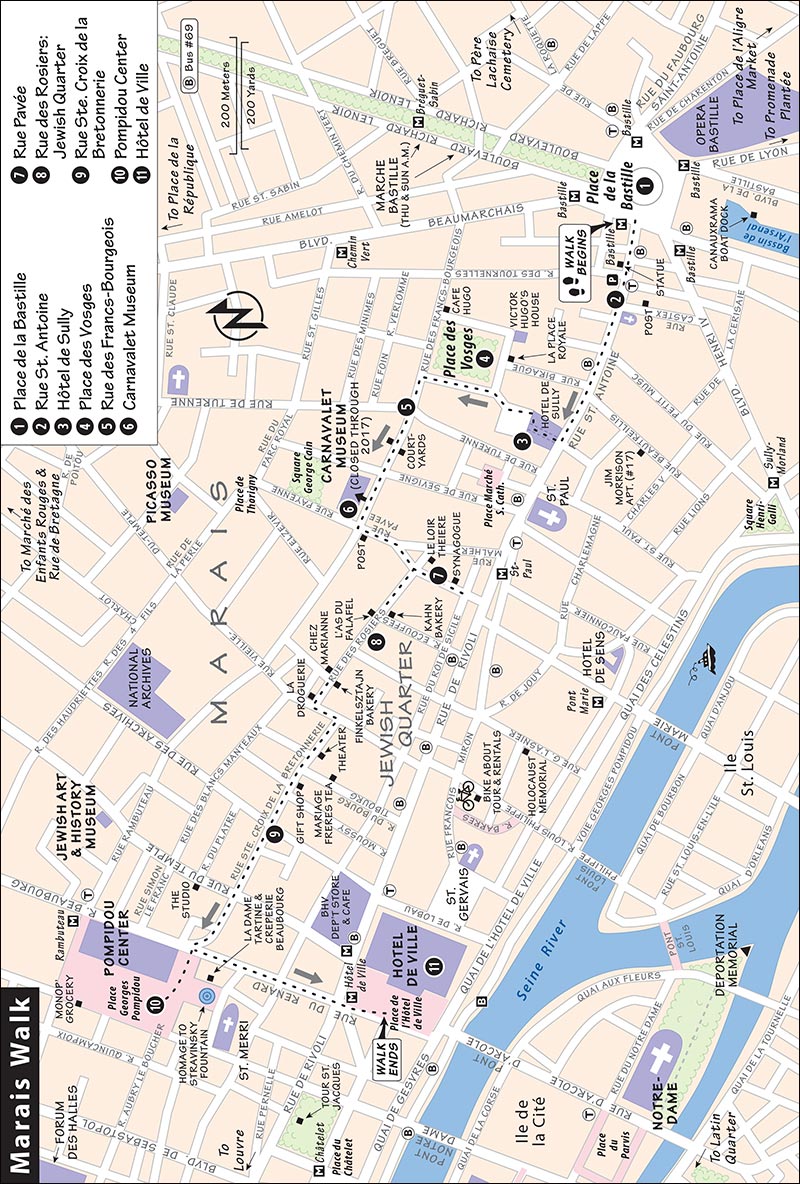

(See “Marais Walk” map, here.)

Length of This Walk: Allow about 2 hours for this 2.25-mile walk. Figure on an additional hour for each museum you visit along the way.

When to Go: The Marais is liveliest on a Sunday afternoon (when many other parts of Paris close for business). Monday morning is sleepy. On Saturdays, Jewish businesses may close, but the area still hops.

Victor Hugo’s House: Free, fee for optional special exhibits, Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, closed Mon, 6 Place des Vosges.

Carnavalet Museum: Closed for renovation in 2017 and beyond.

Picasso Museum: €11, covered by Museum Pass, free on first Sun of month and for those under 18 with ID; Tue-Fri 11:30-18:00 (until 21:00 on third Fri of month), Sat-Sun 9:30-18:00, closed Mon, last entry 45 minutes before closing, 5 Rue de Thorigny.

Jewish Art and History Museum: €9, covered by Museum Pass; Tue-Fri 11:00-18:00, Sat-Sun 10:00-18:00, open later during special exhibits—Wed until 21:00 and Sat-Sun until 19:00, closed Mon year-round, last entry 45 minutes before closing, 71 Rue du Temple.

Pompidou Center: €14, free on first Sun of month, €3 View of Paris ticket covers just the ride to the sixth floor view, Museum Pass covers permanent collection, sixth floor view, and occasional special exhibits; permanent collection open Wed-Mon 11:00-21:00, closed Tue, ticket counters close at 20:00; rest of the building open later—until 22:00 (Thu until 23:00).

Tours: Paris Walks offers excellent guided tours of this area (see here).

Services: There’s free access to good WCs at Victor Hugo’s House.

Starring: The grand Place des Vosges, the Jewish Quarter, several museums, and the boutiques and trendy lifestyle of today’s Marais.

(See “Marais Walk” map, here.)

• Start at the west end of Place de la Bastille. From the Bastille Métro, exit following signs to Place de la Bastille/Place des Vosges. Ascend onto a noisy traffic circle dominated by the bronze Colonne de Juillet (July Column). The figure atop the column is, like you, headed west. Lean against the black railing in front of the Banque de France.

Place de la Bastille

Place de la BastilleThe famous Bastille fortress once stood on this square. All that remains today is a faint cobblestone outline of the fortress’ round turrets traced in the pavement on Rue St. Antoine (30 yards before it hits the square). Though virtually nothing remains, it was on this spot that history turned.

It’s July 1789, and the spirit of revolution is stirring in the streets of Paris. The king’s troops have evacuated the city center, withdrawing to their sole stronghold, a castle-like structure guarding the east edge of the city—the Bastille. The Bastille was also a prison (which even held the infamous Marquis de Sade in 1789) and was seen as the very symbol of royal oppression. On July 14, the people of Paris gathered here at the Bastille’s main gate and demanded the troops surrender. When negotiations failed, they stormed the prison and released its seven prisoners. For good measure, they decorated their pikes with the heads of a few bigwigs. This triumph of citizens over royalty ignited all of France and inspired the Revolution. Over the next few months, the Parisians demolished the stone prison brick by brick.

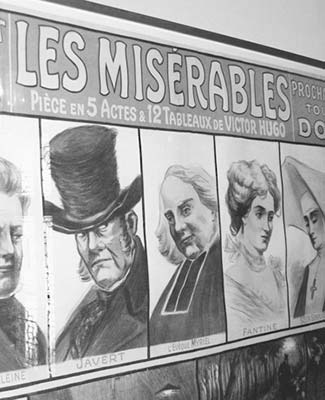

Though the fortress is long gone, Place de la Bastille has remained a sacred spot for freedom lovers ever since. The July Column—with its gilded statue of Liberty elegantly carrying the torch of freedom into the future—is a symbol of France’s long struggle to establish democracy. It was built to commemorate the revolution of 1830, when the conservative King Charles X—who forgot all about the Revolution of the previous generation—needed to be tossed out. The mid-19th century was a time of social unrest throughout Europe; the square drew worker rallies, and at times, the streets of Paris were barricaded by the working class, as dramatized in Les Misérables.

Today the square remains a popular spot for demonstrations, and the Bastille is remembered every July 14 on independence day—Bastille Day (see sidebar).

Across the square, the southeast corner is dominated (some say overwhelmed) by the flashy, curved, glassy gray facade of the Opéra Bastille. In a symbolic attempt to bring high culture to the masses, former French president François Mitterrand chose this location for the building that would become Paris’ main opera venue, edging out Paris’ earlier “palace of the rich,” the Garnier-designed opera house (see here). Designed by Canadian architect Carlos Ott, this grand Parisian project—one of the largest theaters in the world, with nine stages—was opened with fanfare by Mitterrand on the 200th Bastille Day, July 14, 1989. Tickets are heavily subsidized to encourage the unwashed masses to attend, though how much high culture they have actually enjoyed here is a subject of debate. (For opera ticket information, see here.)

• Now turn your back on Place de la Bastille and head west down Rue St. Antoine about four blocks into the Marais.

Rue St. Antoine

Rue St. AntoineFrom Paris’ earliest days, this has been one of its grandest boulevards, part of the east-west axis from Place de la Concorde to the eastern gate, Porte St. Antoine. The street was broadened in the mid-1800s as part of the civic renovation plan by Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann (see sidebar on here). Today, it’s an ordinary street with a typical mix of workaday shops: banks, clothing stores, produce stands, restaurants.

Just past the first block, a statue of Beaumarchais (1732-1799) introduces you to the aristocratic-but-bohemian spirit of the Marais. Beaumarchais, who lived near here, made watches for Louis XV, wrote the bawdy Marriage of Figaro (which Mozart turned into an opera), and smuggled guns to freedom fighters in both the American and French Revolutions.

On the next block, pause at the gas station/parking garage. Notice how minimal the curbside gas pumps are, and ponder how much space most gas stations take up in the US. (Prices posted are for liters—about four liters per gallon.) This station is part of a full-service garage with precious in-city parking (€45/day!) and “lavage traditionnel à la main” (car wash by hand).

Across the street is a stately pre-Revolutionary mansion with its fine red carriage gate. It became a school after the Revolution. Look ahead, along the roofline of this street of 19th-century facades with stout walls holding ranks of chimneys—one chimney for each fireplace, because back then any room that had heat had its own hearth.

Continuing on, at the intersection with Rue de Birague, hippies may wish to make a 100-yard detour to the left, down Rue Beautreillis to #17, the nondescript apartment where rock star Jim Morrison died. (For more on Morrison, see here.)

• Otherwise, continue down Rue St. Antoine to #62 and enter the grand courtyard of Hôtel de Sully (daily 10:00-19:00). If the building is closed, you’ll need to backtrack one block to Rue de Birague to reach the next stop, Place des Vosges.

Hôtel de Sully

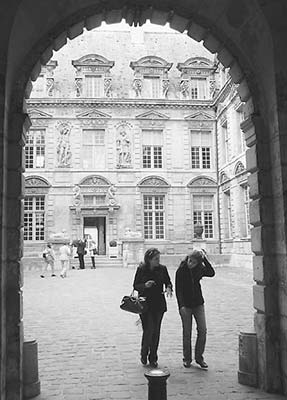

Hôtel de SullyDuring the reign of Henry IV (r. 1589-1610), this area—originally a swamp (marais)—became the hometown of the French aristocracy. Big shots built their private mansions (hôtels), like this one, close to Henry’s stylish Place des Vosges. Hôtels that survived the Revolution now house museums, libraries, and national institutions.

Nobles entered the courtyard by horse-drawn carriage, then parked under the four arches to the right. The elegant courtyard separated the mansion from the noisy and very public street. Look up at statues of Autumn (carrying grapes from the harvest), Winter (a feeble old man), and the four elements.

Enter the building between the sphinxes into a passageway. Continue into the back courtyard, where noisy Paris takes a back seat. Enjoy the oak tree, manicured hedges, vine-covered walls, birdsong, and the back side of the mansion with its warm stone and statues. Use the bit of Gothic window tracery (on the right) for a fun framed photo of your travel partner as a haloed Madonna. At the far end, the French doors are part of a former orangerie, or greenhouse, for homegrown fruits and vegetables throughout winter; these days it warms office workers. Ostentatious as a mansion like this might seem, it was typically just the city residence of a fabulously wealthy noble. The owner of such a mansion was a member of pre-Revolutionary France’s one percent, whose primary residences were much grander chateaux in the countryside.

• Continue through the small door at the far-right corner of the back courtyard, and pop out into one of Paris’ finest squares.

Place des Vosges

Place des VosgesWalk to the center, where Louis XIII, on horseback, gestures, “Look at this wonderful square my dad built.” He’s surrounded by locals enjoying their community park. You’ll see children frolicking in the sandbox, lovers warming benches, and pigeons guarding their fountains while trees shade this escape from the glare of the big city (you can refill your water bottle in the center of the square, behind Louis).

Study the architecture: nine pavilions (houses) per side. The two highest—at the front and back—were for the king and queen (but were never used). Warm red brickwork—some real, some fake—is topped with sloped slate roofs, chimneys, and another quaint relic of a bygone era: TV antennas. Beneath the arcades are cafés, art galleries, and restaurants—it’s a romantic place for dinner (for recommendations, see here).

Henry IV built this centerpiece of the Marais in 1605 and called it “Place Royale.” As he’d hoped, it turned the Marais into Paris’ most exclusive neighborhood. Just like Versailles 80 years later, this was a magnet for the rich and powerful of France. The square served as a model for civic planners across Europe. With the Revolution, the aristocratic splendor of this quarter passed. To encourage the country to pay its taxes, Napoleon promised naming rights to the district that paid first—the Vosges region (near Germany).

The insightful writer Victor Hugo lived at #6 from 1832 to 1848. (It’s at the southeast corner of the square, marked by the French flag.) This was when he wrote much of his most important work, including his biggest hit, Les Misérables. Inside this free museum you’ll wander through eight plush rooms, enjoy a fine view of the square, and find good WCs (see listing on here).

Sample the razzle-dazzle art galleries ringing the square (the best ones are behind Louis). Ponder a daring new piece for that blank wall at home. Or consider a pleasant break at one of the recommended eateries on the square.

• Exit the square at the northwest (far left) corner. Head west on...

Rue des Francs-Bourgeois

Rue des Francs-BourgeoisFrom the Marais of yesteryear, immediately enter the lively neighborhood of today. Stroll down a block full of cafés and eclectic clothing boutiques with the latest fashions. A few doorways (including #8 and #13) lead into courtyards with more shops. Even this “main” street through the neighborhood is narrow and more fit for pedestrians than cars.

In the 19th century, the aristocrats moved elsewhere. The Marais became a working-class quarter, filled with gritty shops, artisans, immigrants, and a Jewish community. Haussmann’s modernization plan put the Marais in line for the wrecking ball. But then the march of “progress” was halted by one tiny little event—World War I—and the Marais was spared. It limped along as a dirty, working-class zone until the 1960s, when it was transformed and gentrified.

Across the street from the Carnavalet Museum (described next), on the corner, is the storefront of a long-gone boulangerie-pâtisserie. Its facade is protected and so it survives, even though today’s shop sells designer fashions.

• Continue west along Rue des Francs-Bourgeois and find the entrance (at #16) of the museum.

Carnavalet Museum

Carnavalet MuseumHoused inside a Marais mansion, this museum (closed for renovation through 2017 and beyond) features the history of Paris, particularly the Revolution years. The bloody events of July 14, 1789, come to life in paintings and displays, including a model of the Bastille carved out of one of its bricks. The mansion itself provides the best possible look at the elegance of the neighborhood back when Place des Vosges was Place Royale.

• From the Carnavalet continue west a half-block down Rue des Francs-Bourgeois to the post office. Modern-art fans can check out the nearby Picasso Museum, which features the whole range of styles and media from the artist’s long life ( see the Picasso Museum Tour chapter). Turn left onto...

see the Picasso Museum Tour chapter). Turn left onto...

Rue Pavée

Rue PavéeIn a few steps, at #24, you’ll pass the 16th-century Paris Historical Library (Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris). Step into the courtyard of this rare Renaissance mansion to see its unstained-glass windows and clean classical motifs. From the street, notice the corner tower—designed so guards could see from which direction angry peasants were coming.

Continue down Rue Pavée, keeping to the right, until you come to the intersection with Rue des Rosiers. Before we turn right on Rue des Rosiers, consider two little side-trips: A half-block straight ahead leads to the Agoudas Hakehilos synagogue (at #10) with its fine Art Nouveau facade (c. 1913, closed to public). It was designed by Hector Guimard, the same architect who designed Paris’ Art Nouveau Métro stations. A half-block to the left, along Rue des Rosiers, is Le Loir dans la Théière (at #3). With tasty baked goods and hot drinks, this place provides the perfect excuse for a break (see description on here).

• From Rue Pavée, turn right onto Rue des Rosiers, which runs straight for three blocks through Paris’ Jewish Quarter.

Rue des Rosiers: Jewish Quarter

Rue des Rosiers: Jewish QuarterThis street—the heart of the Jewish Quarter (and named for the roses that once lined the city wall)—has become the epicenter of Marais hipness and fashion.

Once the largest in Western Europe, Paris’ Jewish Quarter is much smaller today but is still colorful. Notice the sign above #4, which says Hamam (Turkish bath). Although still bearing the sign of an old public bath, it now showcases steamy women’s clothing. Next door, at #4 bis, the Ecole de Travail (trade school) has a plaque on the wall (left of the door) remembering the headmaster, staff, and students who were arrested here during World War II and killed at Auschwitz.

The size of the Jewish population here has fluctuated. It expanded in the 19th century when Jews arrived from Eastern Europe, escaping pogroms (surprise attacks on villages). The numbers swelled during the 1930s as Jews fled Nazi Germany. Then, during World War II, 75 percent of the Jews here were taken to concentration camps (for more information, visit the nearby Holocaust Memorial—see here). And, most recently, Algerian exiles, both Jewish and Muslim, have settled in—living together peacefully here in Paris. (Nevertheless, much of the street has granite blocks on the sidewalk—an attempt to keep out any terrorists’ cars.)

Currently the district’s traditional population is being squeezed out by the trendy boutiques of modern Paris. Case in point—the snappy clothing boutique at the intersection of Rue des Rosiers and Rue Ferdinand Duval was once the venerable Jewish deli Jo Goldenberg. Note the classic facade and a red banner bearing its name still hanging. A plaque marks a 1982 terrorist bombing.

The intersection of Rue des Rosiers and Rue des Ecouffes marks the heart of the small neighborhood that Jews call the Pletzl (“little square”). Lively Rue des Ecouffes, named for a bird of prey, is a derogatory nod to the moneychangers’ shops that once lined this lane. The next two blocks along Rue des Rosiers feature kosher (cascher) restaurants and fast-food places selling falafel, shawarma, kefta, and other Mediterranean dishes. Bakeries specialize in braided challah, bagels, and strudels. Delis offer gefilte fish, piroshkis, and blintzes. Art galleries exhibit Jewish-themed works, and store windows post flyers for community events. Need a menorah? You’ll find one here. You’ll likely see Jewish men in yarmulkes, a few bearded Orthodox Jews, and Hasidic Jews with black coat and hat, beard, and earlocks.

Lunch Break: This is a good place to stop. You’ll be tempted by kosher pizza and plenty of cheap fast-food joints selling falafel “to go” (emporter). Choose from L’As du Falafel (#34), with its bustling New York deli atmosphere, the Sacha Finkelsztajn Yiddish bakery at #27, or Chez Marianne for traditional Jewish meals. (For more options, see the sidebar on here.) For a breath of fresh air, step into the very Parisian Jardin des Rosiers, a half-block before L’As du Falafel, at 10 Rue des Rosiers (or backtrack and head behind the Carnavalet Museum to Square George Caïn on Rue Payenne).

• Rue des Rosiers dead-ends at Rue Vieille du Temple. Turn left on Rue Vieille du Temple, then take your first right onto Rue Ste. Croix de la Bretonnerie and prepare for a little cultural whiplash (from Jewish culture to gay culture).

Side-Trip to the Holocaust Memorial: Consider a five-block detour to see the memorial (for details on visiting the memorial, see the listing on page 98). To get there, head south on Rue Vieille du Temple, cross Rue de Rivoli, and make your second left onto the traffic-free passageway named Allée des Justes. It’s at 17 Rue Geoffroy l’Asnier.

Rue Ste. Croix de la Bretonnerie

Rue Ste. Croix de la BretonnerieGay Paree’s openly gay main drag is lined with cafés, lively shops, and crowded bars at night. Check the posters at #7, Le Point Virgule theater (means “The Semicolon”), to see what form of edgy musical comedy is showing tonight (most productions of up-and-coming humorists are in French). A short detour left on Rue du Bourg Tibourg leads to the luxurious tea extravaganza of Mariage Frères (#30). Continue along Rue Ste. Croix de la Bretonnerie to #38 (on the right) and peruse real estate prices in the area—€500,000 for a one-bedroom flat?! Parisians willingly pay that for the neighborhood’s high quality of life.

Farther ahead at Rue du Temple, consider detouring a few blocks to the right to the Jewish Art and History Museum (if visiting, see listing on here). On the way, you’ll pass The Studio (41 Rue du Temple), a dance school wonderfully situated in a 17th-century courtyard.

• Continue west on Rue Ste. Croix (which turns into Rue St. Merri). Up ahead you’ll see the colorful pipes of the Pompidou Center. Cross Rue du Renard and enter the Pompidou’s colorful world of fountains, restaurants, and street performers.

Pompidou Center

Pompidou CenterSurvey this popular spot from the top of the sloping square. Tubular escalators lead to the museum and a great view.

The Pompidou Center subscribes with gusto to the 20th-century architectural axiom “form follows function.” To get a more spacious and functional interior, the guts of this exoskeletal building are draped on the outside and color-coded: vibrant red for people lifts, cool blue for air ducts, eco-green for plumbing, don’t-touch-it yellow for electrical stuff, and white for the structure’s bones. (Compare the Pompidou Center to another exoskeletal building, Notre-Dame.) For details on visiting the museum,  see the Pompidou Center Tour chapter.

see the Pompidou Center Tour chapter.

Enjoy the adjacent fountain, an homage to Igor Stravinsky. Jean Tinguely and Niki de Saint-Phalle designed it as a tribute to the composer: Every sculpture within the fountain represents one of his hard-to-hum scores. For low-stress meals or an atmospheric spot for a drink, try the lighthearted Dame Tartine (or the crêperie next door), which overlooks the fountains and serves good, inexpensive food.

• Double back to Rue du Renard, turn right, and stroll past Paris’ ugliest (modern) building on the left. Walk toward the river until you find...

Hôtel de Ville

Hôtel de VilleLooking more like a grand château than a public building, Paris’ City Hall stands proud. This spot has been the center of city government since 1357. Each of Paris’ 20 arrondissements has its own city hall and mayor, but this one is the big daddy of them all.

The Renaissance-style building (built 1533-1628 and reconstructed after a 19th-century fire) displays hundreds of statues of famous Parisians on its facade. Peek from behind the iron fences through the doorways to see elaborate spiral stairways, which are reminiscent of Château de Chambord in the Loire. Playful fountains energize the big, lively square in front.

This spacious stage has seen much of Paris’ history. On July 14, 1789, Revolutionaries rallied here on their way to the Bastille. In 1870, it was home to the radical Paris Commune. During World War II, General Charles de Gaulle appeared at the windows to proclaim Paris’ liberation from the Nazis. And in 1950, Robert Doisneau snapped a famous black-and-white photo of a kissing couple, with Hôtel de Ville as a romantic backdrop.

Today, it’s the seat of the mayor of Paris, who has one of the most powerful positions in France. In the 1990s, Jacques Chirac used the mayorship as a stepping stone to another powerful position—president of France.

The square in front is a gathering place for Parisians. Demonstrators assemble here to speak their minds. Crowds cheer during big soccer games shown on huge TV screens. In summer, the square hosts sand volleyball courts; in winter, a big ice-skating rink. There’s often a children’s carousel, or manège. Now a Paris institution, carousels were first introduced by Henri IV in 1605—the same year Place des Vosges was built. Year-round, the place is always beautifully lit after dark.

After our walk through the Marais, one of the city’s oldest neighborhoods, it’s appropriate to end up here, at the governmental heart of Paris.

• The tour’s over. The Hôtel de Ville Métro stop is right here, and the towers of Notre-Dame poke above the rooftops to the south.